Natural Law: Definition and Application

ziggymaj / Getty Images

- U.S. Legal System

- History & Major Milestones

- U.S. Constitution & Bill of Rights

- U.S. Political System

- Defense & Security

- Campaigns & Elections

- Business & Finance

- U.S. Foreign Policy

- U.S. Liberal Politics

- U.S. Conservative Politics

- Women's Issues

- Civil Liberties

- The Middle East

- Race Relations

- Immigration

- Crime & Punishment

- Canadian Government

- Understanding Types of Government

- B.S., Texas A&M University

Natural law is a theory that says all humans inherit—perhaps through a divine presence—a universal set of moral rules that govern human conduct.

Key Takeaways: Natural Law

- Natural law theory holds that all human conduct is governed by an inherited set of universal moral rules. These rules apply to everyone, everywhere, in the same way.

- As a philosophy, natural law deals with moral questions of “right vs. wrong,” and assumes that all people want to live “good and innocent” lives.

- Natural law is the opposite of “man-made” or “positive” law enacted by courts or governments.

- Under natural law, taking another life is forbidden, no matter the circumstances involved, including self-defense.

Natural law exists independently of regular or “positive” laws—laws enacted by courts or governments. Historically, the philosophy of natural law has dealt with the timeless question of “right vs. wrong” in determining the proper human behavior. First referred to in the Bible, the concept of natural law was later addressed by the ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle and Roman philosopher Cicero .

What Is Natural Law?

Natural law is a philosophy based on the idea that everyone in a given society shares the same idea of what constitutes “right” and “wrong.” Further, natural law assumes that all people want to live “good and innocent” lives. Thus, natural law can also be thought of as the basis of “morality.”

Natural law is the opposite of “man-made” or “positive” law. While positive law may be inspired by natural law, natural law may not be inspired by positive law. For example, laws against impaired driving are positive laws inspired by natural laws.

Unlike laws enacted by governments to address specific needs or behaviors, natural law is universal, applying to everyone, everywhere, in the same way. For example, natural law assumes that everyone believes killing another person is wrong and that punishment for killing another person is right.

Natural Law and Self Defense

In regular law, the concept of self-defense is often used as justification for killing an aggressor. Under natural law, however, self-defense has no place. Taking another life is forbidden under natural law, no matter the circumstances involved. Even in the case of an armed person breaking into another person’s home, natural law still forbids the homeowner from killing that person in self-defense. In this way, natural law differs from government-enacted self-defense laws like so-called “ Castle Doctrine ” laws.

Natural Rights vs. Human Rights

Integral to the theory of natural law, natural rights are rights endowed by birth and not dependent on the laws or customs of any particular culture or government. As stated in the United States Declaration of Independence , for example, the natural rights mentioned are “Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Happiness.” In this manner, natural rights are considered universal and inalienable, meaning they cannot be repealed by human laws.

Human rights, in contrast, are rights endowed by society, such as the right to live in safe dwellings in safe communities, the right to healthy food and water, and the right to receive healthcare. In many modern countries, citizens believe the government should help provide these basic needs to people who have difficulty obtaining them on their own. In mainly socialist societies , citizens believe the government should provide such needs to all people, regardless of their ability to obtain them.

Natural Law in the US Legal System

The American legal system is based on the theory of natural law holding that the main goal of all people is to live a “good, peaceful, and happy” life, and that circumstances preventing them from doing so are “immoral” and should be eliminated. In this context, natural law, human rights, and morality are inseparably intertwined in the American legal system.

Natural law theorists contend that laws created by the government should be motivated by morality. In asking the government to enact laws, the people strive to enforce their collective concept of what is right and wrong. For example, the Civil Rights Act of 1964 was enacted to right what the people considered to be a moral wrong—racial discrimination. Similarly, the peoples’ view of enslavement as being a denial of human rights led to ratification of the Fourteenth Amendment in 1868.

Natural Law in the Foundations of American Justice

Governments do not grant natural rights. Instead, through covenants like the American Declaration of Independence and the U.S. Constitution , governments create a legal framework under which the people are permitted to exercise their natural rights. In return, people are expected to live according to that framework.

In his 1991 Senate confirmation hearing, U.S. Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas expressed the widely shared belief that the Supreme Court should refer to natural law in interpreting the Constitution. “We look at natural law beliefs of the Founders as a background to our Constitution,” he stated.

Among the Founders who inspired Justice Thomas in considering natural law to be an integral part of the American justice system, Thomas Jefferson referred to it when he wrote in the first paragraph of the Declaration of Independence:

“When, in the course of human events, it becomes necessary for one people to dissolve the political bands which have connected them with another, and to assume among the powers of the earth, the separate and equal station to which the laws of nature and of nature’s God entitle them, a decent respect to the opinions of mankind requires that they should declare the causes which impel them to the separation.”

Jefferson then reinforced the concept that governments cannot deny rights granted by natural law in the famous phrase:

“We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights, that among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.”

Natural Law in Practice: Hobby Lobby vs. Obamacare

Deeply rooted in the Bible, natural law theory often influences actual legal cases involving religion. An example can be found in the 2014 case of Burwell v. Hobby Lobby Stores , in which the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that for-profit companies are not legally obligated to provide employee health care insurance that covers expenses for services that go against their religious beliefs.

The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010 —better known as “Obamacare”—requires employer-provided group health care plans to cover certain types of preventative care, including FDA-approved contraceptive methods. This requirement conflicted with the religious beliefs of the Green family, owners of Hobby Lobby Stores, Inc., a nationwide chain of arts and crafts stores. The Green family had organized Hobby Lobby around their Christian principles and had repeatedly stated their desire to operate the business according to Biblical doctrine, including the belief that any use of contraception is immoral.

In 2012, the Greens sued the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, claiming that the Affordable Care Act’s requirement that employment-based group health care plans cover contraception violated the Free Exercise of Religion Clause of the First Amendment and the 1993 Religious Freedom Restoration Act (RFRA), that “ensures that interests in religious freedom are protected.” Under the Affordable Care Act, Hobby Lobby faced significant fines if its employee health care plan failed to pay for contraceptive services.

In considering the case, the Supreme Court was asked to decide if the RFRA allowed closely held, for-profit companies to refuse to provide its employees with health insurance coverage for contraception based on the religious objections of the company’s owners.

In a 5-4 decision, the Supreme Court held that by forcing religion-based companies to fund what they consider the immoral act of abortion, the Affordable Care Act placed an unconstitutionally “substantial burden” on those companies. The court further ruled that an existing provision in the Affordable Care Act exempting non-profit religious organizations from providing contraception coverage should also apply to for-profit corporations such as Hobby Lobby.

The landmark Hobby Lobby decision marked the first time the Supreme Court had recognized and upheld a for-profit corporation’s natural law claim of protection based on a religious belief.

Sources and Further Reference

- “ Natural Law .” Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- “ The Natural Law Tradition in Ethics .” Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (2002-2019)

- “Hearing of the Senate Judiciary Committee on the Nomination of Clarence Thomas to the Supreme Court. Part 1 , Part 2 , Part 3 , Part 4 .” U.S. Government Publishing Office.

- What Are Natural Rights?

- National Supremacy and the Constitution as Law of the Land

- What Is the "Necessary and Proper" Clause in the US Constitution?

- Loving v. Virginia (1967)

- The Health Care System In The US

- Conservative Perspectives on Health Care Reform

- Supreme Court Decisions - Everson v. Board of Education

- Moral Philosophy According to Immanuel Kant

- Executive Orders Definition and Application

- Is Medical Help for Illegal Immigrants Covered Under Obamacare?

- Where Did the Right to Privacy Come From?

- Biography of John G. Roberts, Chief Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court

- Due Process of Law in the US Constitution

- What Is Judicial Review?

- Meet the Female Supreme Court Justices

- Separation of Powers: A System of Checks and Balances

Legal Dictionary

The Law Dictionary for Everyone

Natural Law

Natural law is the philosophy that certain rights, moral values, and responsibilities are inherent in human nature, and that those rights can be understood through simple reasoning. In other words, they just make sense when you consider the nature of humanity. Throughout history, the phrase “natural law” has had to do with determining how humans should behave morally. The law of nature is universal, meaning that it applies to everyone in the same way. To explore this concept, consider the following natural law definition.

Definition of Natural Law

- The belief that certain laws of morality are inherent by human nature, reason, or religious belief, and that they are ethically binding on humanity.

1350-1400 Middle English

What is Natural Law

Natural law is a philosophy that is based on the idea that “right” and “wrong” are universal concepts, as mankind finds certain things to be useful and good, and other things to be bad, destructive, or evil. This means that, what constitutes “right” and “wrong,” is the same for everyone, and this concept is expressed as “morality.” As an example of natural law, it is universally accepted that to kill someone is wrong, and that to punish someone for killing that person is right, and even necessary.

To solve an ethical dilemma using natural law, the basic belief that everyone is naturally entitled to live their own lives must be considered and respected. From there, natural law theorists determine what an innocent life is, and what elements comprise the life of an “unjust aggressor.”

The natural law theory pays particular attention to the concept of self-defense, a justification often relied upon in an attempt to explain an act of violence. As has been the case with self-defense claims throughout history, it is often difficult to apply what seems to be a simple concept (right vs. wrong) to issues that are actually complex in nature.

For example, acts of violence, like murder , work against people’s natural inclination to live a good and innocent life. Therefore, in a situation where “the needs of the many outweigh the needs of the few,” and an act of violence is committed against the smaller group of people in order to save the larger one, the act still goes against human nature.

Killing another person is forbidden by natural law, no matter the circumstance, as it goes against the human purpose of life. Even if someone is, say, armed and breaking into another person’s home, under natural law the homeowner still does not have the right to kill that person in self-defense. It is in this way that natural law differs from actual law.

Natural Law in the American Legal System

Natural law in the American legal system is defined as a legal theory that considers law and morality to be so connected to one another that they are practically the same. Since natural law in the American legal system is focused on morality, as actions can be defined as both “good” and “bad,” natural law theorists believe that the laws that humans create are motivated by morality, as opposed to being defined by an authority figure like a monarch, a dictator, or a governmental organization.

This means that people are guided by their own human nature to determine what laws should be created, in accordance with what they know to be “right” and “wrong,” then proceed to live their lives in obedience of those laws once they have become legislation .

Natural law in the American legal system is centered on the belief that everything in life has a purpose, and that humans’ main purpose is to strive to live a life that is both “good” and happy. Any behaviors or actions that deliberately obstruct that one simple goal are considered to be “unnatural” or “immoral.”

Just as everything is deemed to have a purpose in natural law, so too do the legislated laws that are created. The simple purpose of legislation is to provide a way to maintain peace, and achieve justice. Natural law theorists believe that a law that fails to meet this goal is not really a law at all. Therefore, if there are any flaws determined to be present with an existing law, natural law dictates it is not a law that is to be followed. This stands in sharp contrast to legal positivism, which is the legal theory that, even if a law is deeply flawed, it is still a valid law that must be followed.

Natural Rights vs. Human Rights

It may be simple semantics, but the adjective before the word “rights,” whether that adjective is “human” or “natural,” can make a difference in how the term is defined. When asking the question of natural rights vs. human rights, consider that natural rights are those endowed by birth and are to be protected by the government. These rights include life, liberty, and property, among others.

Human rights, on the other hand, are rights deemed so by society. These include such things as the right to live in a safe, suitable dwelling, the right to healthy food, and the right to receive healthcare. In many modern societies, citizens feel that the government should provide these things to people who have difficulty obtaining them on their own.

How the Constitution Addresses Natural and Human Rights

At the time that the Declaration of Independence was drafted, the “rights” that people spoke of were thought to be natural, or God-given. However, beginning in the 20th century, the term “rights” evolved to be referred to as “human rights.” While natural rights and human rights are essentially universal, there still exist some significant differences between them.

Natural rights are not granted to people by their government. Governments simply establish the political conditions under which people are permitted to exercise their natural rights, and then the government expects its people to live according to those conditions. Conversely, human rights are those granted to people by the governmental authorities. The term “human rights” has become a catch-all term for anything that society as a whole believes to be important.

Natural rights, by their very nature, do not change with time. Everyone everywhere has always been endowed with the same right to “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.” By contrast, human rights are subject to change and often do, with new human rights being recognized, defined, and promoted by governmental organizations.

Natural Law Examples in Religious Beliefs

An example of natural law being tested in the courts can be found in the case of Gilardi v. U.S. Dept. of Health and Human Services . Here, two brothers – Francis and Philip Gilardi – own Freshway Foods and Freshway Logistics, both of which are fresh-food processing companies located in Sidney, Ohio. The brothers are Roman Catholic, and found that the Affordable Care Act’s mandate that companies provide employee health insurance that covers birth control options conflicted with their religious beliefs. The men stood their ground to operate their companies in accordance with their religious beliefs – refusing to compensate employees for birth control options in their health insurance plans.

When the Gilardis were issued $14 million in penalties for not complying with the law, they sued the government on behalf of their companies, saying that the current mandate is trying to force them to choose between their faith and their livelihood. The Gilardi case claimed that the Affordable Care Act violated their constitutional rights under the Free Exercise Clause of the Constitution , as well as the Religious Freedom Restoration Act , and the Administrative Procedure Act .

The Affordable Care Act, colloquially referred to as “Obamacare,” derives its authority to mandate options for contraception and sterilization through natural law, seeking to provide healthcare options that are for the good of the people in general. No individuals covered by these insurance plans are required to utilize any of the services. When the case was heard by the appellate court, Judge Janice Rogers Brown ruled that the Freshway companies are not “people” as defined by the Constitution and the federal Religious Freedom Restoration Act (i.e. individual human beings), so they are not able to exercise a religious belief and cannot claim that the mandate offends “them.”

Natural Law and the Declaration of Independence

Judge Brown is known for her arguments in favor of judges seeking out a “higher authority than precedent or man-made laws” when making her opinions. She referred to “moral” law, which makes this a good example of natural law infiltrating the justice system, in making her decision, stating that forcing the Gilardis to comply with the mandated provision of contraception methods would be a “compelled affirmation of a repugnant belief.” Brown also concluded that because the Freshway companies are run as closely held corporations, with each having only two owners, then the brothers could sue in that capacity to express their personal objections to the mandate as it conflicts with their religion.

Judge Brown isn’t the only one who feels that man’s laws must yield to a “higher authority,” and natural law beliefs. Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas has reportedly been known to express his belief that natural law should be referred to when justices are attempting to interpret the Constitution. Thomas was even quoted during his Senate confirmation hearings in 1991 as saying:

“We look at natural law beliefs of the Founders as a background to our Constitution.”

Those who believe that natural law should be referred to in this way, and that justices should turn to a higher power, often refer to the Declaration of Independence for support. Specifically, they refer to its opening lines, wherein Thomas Jefferson referred to God’s law, as he wrote:

“When, in the course of human events, it becomes necessary for one people to dissolve the political bands which have connected them with another, and to assume among the powers of the earth, the separate and equal station to which the laws of nature and of nature’s God entitle them, a decent respect to the opinions of mankind requires that they should declare the causes which impel them to the separation.”

Also applicable is the section that is arguably more well-known:

“We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights , that among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.”

Related Legal Terms and Issues

- Declaration of Independence – The formal statement that declared the freedom of the thirteen American colonies from the rule of Great Britain.

- Legislation – A law, or body of laws, enacted by a government.

- Mandate – An official order to carry out a policy, or to take some action.

Thomistic Philosophy Page

Natural Law

St. Thomas Aquinas on the Natural Law.

After his Five Ways of Proving the Existence of God ( ST Ia, 2, 3 ), St. Thomas Aquinas is probably most famous for articulating a concise but robust understanding of natural law. Just as he claims and demonstrates in his proofs for God’s existence that natural human reason can come to some understanding of the Author of nature, so in his exposition of natural law, Aquinas shows that human beings can discover objective moral norms by reasoning from the objective order in nature, specifically human nature. While Aquinas believes that this objective order of nature (and the operation of human reason which discovers it) are, in fact, ultimately grounded and established by God’s intelligent willing of the good of creation (i.e., His love), Aquinas’s understands that one need not know that God’s providence underpins the objective order of nature. Thus, whether or not one believes in or rationally proves there is a God, one can recognize and be bound by the natural law for, according to Aquinas, it applies to all people at all times, and in some sense is known by all rational humans (though, of course, they do not (but should) always act in accordance with it).

Eternal Law

In his monumental Summa Theologiae , St. Thomas Aquinas , devotes relatively little space to the natural law – merely a single question and passing mention in two others. There, he bases his doctrine of the natural law, as one would expect, on his understanding of God and His relation to His creation. He grounds his theory of natural law in the notion of an eternal law (in God). In asking whether there is an eternal law, he begins by stating a general definition of all law: Law is a dictate of reason from the ruler for the community he rules.

This dictate of reason is first and foremost within the reason or intellect of the ruler. It is the idea of what should be done to ensure the well-ordered functioning of whatever community the ruler has care for. (It is a fundamental tenet of Aquinas’ political theory that rulers rule for the sake of the governed, i.e., for the good and well-being of those subject to the ruler.) Since he has elsewhere shown that God rules the world with his reason (since he is the cause of its being (cf. Summa Theologiae I 22, 1-2) ), Aquinas concludes that God has in His intellect an idea by which He governs the world. This Idea, in God, for the governance of things is the eternal law. ( ST I-II, 91, 1)

Defining the Natural Law

Next, Aquinas asks whether there is in us a natural law. First, he makes a distinction: A law is not only in the reason of a ruler, but may also be in the thing that is ruled. Just as the plan or rule for constructing a house resides primarily in the mind of an architect, so that plan or rule can be said also to be in the house so constructed, imprinted, as it were, into the very composition of the house and dictating how the house is properly to operate or function (cf. ST I-II, 93, 1 ).

In the case of the eternal law, the things of creation that are ruled by that law have it imprinted on the them through their nature or essence. Since things act according to their nature, they derive their “respective inclinations to their proper acts and ends” ( final cause ) according to the law that is written into their nature. Everything in nature, insofar as they reflect the order by which God directs them through their nature for their own benefit, reflects the eternal law in their own natures ( ST I-II, 91, 2)

The natural law is properly applied to the case of human beings, and acquires greater precision because of the fact that we have reason and free will . It is our nature as humans to act freely (i.e., to be provident for ourselves and others) by directing ourselves toward our proper acts and end. That is, we human beings must exercise our natural reason to discover what is best for us in order to achieve the end to which our nature inclines. Furthermore, we must do this through the exercise our freedom, by choosing what reason determines to be naturally suited to us, i.e., what is best for our nature.

Now among all others, the rational creature is subject to Divine providence in the most excellent way, in so far as it partakes of a share of providence, by being provident both for itself and for others. Wherefore it has a share of the Eternal Reason, whereby it has a natural inclination to its proper act and end: and this participation of the eternal law in the rational creature is called the natural law . ( ST I-II, 91, 2)

The natural inclination of humans to achieve their proper end through reason and free will is the natural law. Formally defined, the natural law is humans’ participation in the eternal law, through reason and will. Humans actively participate in the eternal law of God (the governance of the world) by using reason in conformity with the natural law to discern what is good and evil . Just as the proper functioning of the body and its organs in order to achieve an optimal physical life defines health and the rules of medicine and healthy living, so the proper functioning of all human faculties defines the human good and the rules for living well (morally, spiritually, socially, etc.). The natural law encompasses the rules and precepts by which humans do good actions and live well, individually and collectively.

The Human Good

In applying this universal notion of natural law to the human person, one first must decide what it is that (God has ordained) human nature is inclined toward. Since each thing has a nature (given it by God), and each thing has a natural end, so there is a fulfillment to human activity of living. Even apart from knowing about this dependence on God, one can discover by reason what the purpose of living is, and so he or she will discover what his or her natural end is. Building on the insight of Aristotle that “happiness is what all desire,” a person can conclude that they will be happy when he or she achieves this natural end, specifically “a life of virtuous activity in accordance with reason” ( Nicomachean Ethics , I, 7 ; see Aquinas, Commentary, Bk. I, C h. 10, nos. 127-8 ). The commands or precepts, then, that lead to human happiness or flourishing is what Aquinas means by the natural law.

Aquinas distinguishes different levels of precepts or commands that constitute or comprise the natural law. The most universal is the command “Good is to be done and pursued and evil avoided ” ( ST I-II, 94, 2 ). This applies to everything and everyone, so much so that some consider it to be more of a description or definition of what we mean by “good.” For these philosophers, a thing is “good” just in case it is pursued or done by someone. Aquinas would agree with this to a certain extent; but he would say that that is a definition of an apparent good. Thus, this position of Aquinas has a certain phenomenological appeal: a person does anything and everything he or she does only because that thing at least “appears” to be good. Even when I choose something that I know is bad for myself, I nevertheless chooses it under some aspect of good, i.e., as some kind of good. I know the cake is fattening, for example, and I don’t choose to eat it as fattening. I do, however, choose to eat it as tasty (which is an apparent, though not a true, good). A true good is an object of desire which reason determines to be appropriate or fitting to a given person, in certain circumstances, in light of their universal human nature ( ST I-II, 94, 3 , esp. ad 3). Sometimes this will include eating cake, but not too much of it.

Precepts of the Natural Law

The precepts of the natural law are commands derived from the inclinations or desires natural to human beings; for Aquinas there is no problem in deriving “ought” from “is.” Since the object of every desire has the character or formality of “good,” there are a variety of goods we naturally seek. They are all subsumed under the First Principle of Practical Reasoning: The good is to be done and pursued, and evil avoided. This first principle is operative in all the precepts that comprise the natural law. Subsequent precepts of the natural law derive first from various sorts of inclinations as humans share these with other sorts of natural things, and second, as one discovers these goods in greater specificity ( ST I-II, 94, 2 ).

On the level that we share with all substances, the natural law commands that we preserve ourselves in being. Therefore, one of the most basic precepts of the natural law is to not commit suicide. (Nevertheless, suicide can, sadly, be chosen as an apparent good, e.g., as the cessation of pain; often it is not chosen at all, but the result of mental illness.) On the level we share with all living things, the natural law commands that we take care of our life, and transmit that life to the next generation. Thus, almost as basic as the preservation of our lives, the natural law commands us to rear and care for offspring. On the level that is most specific to humans, the fulfillment of the natural law consists in the exercise those activities that are unique and proper to humans, i.e., knowledge and love , and in a state that is also natural to human persons, i.e., society. The natural law, thus, commands us to develop our rational and moral capacities by growing in the virtues of intellect (prudence, art, and science ) and will ( justice , courage, temperance) ( ST I-II, 94, 3 ). Natural law also commands those things that make for the harmonious functioning of society (“Thou shalt not kill,” “Thou shalt not steal”). Human nature also shows that each of us have a destiny beyond this world, too. Man’s infinite capacity to know and love shows that he is destined to know and love an infinite being, God, and so, natural law commands the practice of religion.

All of these levels of precepts so far outlined are only the most basic. “The good is to be done and pursued and evil is to be avoided” is not very helpful for making actual choices. Therefore, Aquinas believes that one needs one’s reason to be perfected by the virtues , especially prudence, in order to discover precepts of the natural law that are more proximate to the choices that one has to make on a day-to-day basis. As is indicated in the table above, particular precepts, as they derive from more general ones in issuing forth in action, can conflict with each other. The command to save David might conflict with the apparent injunction that one ought not to lie to soldiers bent on unjustly executing him, but might cohere with the injunction not to give them information they have no just right to. Applying the natural law to cases, then, is more open to error, even though the general principles are true and apparent, and there is, in fact, a true and most rational application to certain particular circumstances ( ST I-II, 94, 3 ).

Application of the Natural Law as an Absolute / Objective Standard

Given that the natural law depends on the inclinations inherent in human nature (as ordained by the intelligent, loving providence of God, i.e., the Eternal Law) it applies to all people, at all times. Yet Aquinas readily acknowledges that the laws and morals of people can vary wildly. Rather than succumbing to moral relativism (where what is morally good and right is merely what each society or person thinks is such), Aquinas seeks both to uphold the objective and universal basis of morality in the natural law, and to explain the variety of moral and legal injunctions. Despite his belief that the natural law applies universally, Aquinas explains how this variety arises, first from the perspective of the generality of the precepts, and then from the perspective of the knowledge an individual has of the precepts.

From the perspective of the generality of the precepts, Aquinas reasons that the more general a precept is, the less is it open to exceptions. The general principles of both speculative reasoning (e.g., mathematics and the sciences) and practical reasoning (arts, ethics and politics) are necessary, and so the primary precepts of the natural law apply in all cases. The good is always to be done; life is always to be preserved. Yet, as one seeks to apply the general principles to particular cases, the particular circumstances necessitate greater variety in the kinds of actions required by the principle. Preserving life in the community may require the execution of murderers .

Although there is necessity in the general principles, the more we descend to matters of detail, the more frequently we encounter defects. … In matters of action, truth or practical rectitude is not the same for all, as to matters of detail, but only as to the general principles: and where there is the same rectitude in matters of detail, it is not equally known to all . ( ST I-II, 94, 4 )

From the perspective of the knowledge an of individual, the variety of ways of applying the natural law also leads to variability in knowing how to so apply the principles. The more general a precept is, the more likely it is to be known by a greater number of people. The more particular a precept of the natural law (or the application of a general precept to a particular case) is, the more likely it is that a particular individual will get it wrong.

Aquinas thus concludes that the greater the detail, the more likely it will be that people disagree about what the natural law requires:

Consequently, we must say that the natural law, as to general principles, is the same for all, both as to rectitude and as to knowledge. But as to certain matters of detail, which are conclusions, as it were, of those general principles, it is the same for all in the majority of cases, both as to rectitude and as to knowledge; and yet in some few cases it may fail, both as to rectitude, by reason of certain obstacles (just as natures subject to generation and corruption fail in some few cases on account of some obstacle), and as to knowledge, since in some the reason is perverted by passion, or evil habit, or an evil disposition of nature. ( ST I-II, 94, 4 )

Even though it is true that as one makes more particular applications of the general precepts of the natural law, the form that application takes is likely to be displayed in a greater variety of actions, nevertheless, the same natural law is being applied in each case, and the same natural law commands a variety of actions as given situations demand. What is the right thing to do might vary according to a variety of circumstances, yet in each case, the right thing to do is objective and necessary, a rational deduction of the certain general principles of moral action.

Just and Unjust Laws

Aquinas thus argues that the natural law cannot be changed, except by way of addition. Such additions, he says, are “things for the benefit of human life [which] have been added over and above the natural law, both by Divine law and by human laws ” ( ST I-II, 94, 5 ). Nothing can be subtracted from the natural law with regard to the primary precepts, and thus, no human law which commands something contrary to the natural law can be just. Interestingly, he notes, that certain features of society, while not being provided to humans by nature, accord with the natural law under the general principle of being “devised by human reason for the benefit of human life” ( ad 3 ). He includes among such non-natural features as consonant with natural law: clothing, private property and slavery. Yet by introducing the condition that just additions to the natural law must be for the benefit of human life, he allows, as we’ll see below, that should they fail this condition, they would thereby be subtractions from the natural law and so, unjust.

Given the universality and objective character of the natural law, Aquinas unsurprisingly asserts that it cannot be forgotten or “abolished from the human heart” ( ST I-II, 94, 6 ). Nevertheless, he recognizes that many people act as though they do not recognize this universal and objective standard of morality since they are inhibited by the influence of concupiscence or other passions , by an error of reasoning , or “by vicious customs and corrupt habits.” Indeed, as the third objection notes, there are whole societies which operate according to laws at variance with the natural law, declaring their departures as “just.” Aquinas responds that such laws abolish only the “secondary precepts of the natural law, against which some legislators have framed certain enactments which are unjust.” ( ST 94, 6 ad 3 ). This nuanced understanding of the natural law, then, provides a standard for judging just and unjust laws. He makes this criterion of just laws explicit when he turns to the origin of human law.

Consequently, every human law has just so much of the nature of law, as it is derived from the law of nature. But if in any point it deflects from the law of nature, it is no longer a law but a perversion of law.” ( ST I-II, 95, 2 )

Aquinas, thus, seems to grant that whatever judges a system of human laws must stand outside and above that system. The laws of Nazi Germany which prescribed the execution of Jews and dissidents and forbade their protection constituted “crimes against humanity,” not because these laws were in violation of other laws of Germany, or the laws of France or the United States. The reason that the attempted destruction of the Jews was wrong was not even because the whole rest of the world thought it was wrong. The crimes of Nazi Germany could be judged as crimes because they were violations of a law that stands apart from and above the laws of every nation; they were violations of the natural law. Natural law, then, serves as the standard against which we determine whether human positive laws are just or not.

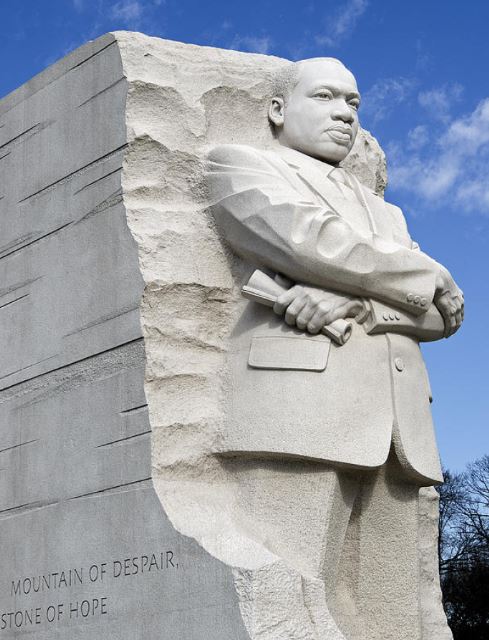

One can see these principles at work in “ Letter from Birmingham City Jail ” by Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. As King says:

I would be the first to advocate obeying just laws. One has not only a legal but a moral responsibility to obey just laws. Conversely, one has a moral responsibility to disobey unjust laws. I would agree with St. Augustine that “an unjust law is no law at all.” Now, what is the difference between the two? How does one determine whether a law is just or unjust? A just law is a man made code that squares with the moral law or the law of God. An unjust law is a code that is out of harmony with the moral law. To put it in the terms of St. Thomas Aquinas: An unjust law is a human law that is not rooted in eternal law and natural law. Any law that uplifts human personality is just. Any law that degrades human personality is unjust. All segregation statutes are unjust because segregation distorts the soul and damages the personality. It gives the segregator a false sense of superiority and the segregated a false sense of inferiority.

The justification to which King appeals in order to show that segregation laws are unjust is not other laws of Alabama or of the United States, but the natural law as it is founded in human nature. Human nature demands a true sense of equality and dignity, and because segregation laws violate that equality and dignity, they are unjust. Segregation laws clearly diminished the dignity, and thus damage the personality of blacks in Alabama. Interestingly, King asserts that segregation laws were harmful to the white majority, distorting their proper dignity and damaging their personality as well. In both cases, segregation laws are an affront to human dignity, founded as it is in our common human nature.

The Thomistic notion of natural law has its roots, then, in a quite basic understanding of the universe as caused and cared for by God, and the basic notion of what a law is. It is a fairly sophisticated notion by which to ground the legitimacy of human law in something more universal than the mere agreement and decree of legislators. Yet, it allows that what the natural law commands or allows is not perfectly obvious when one gets to the proximate level of commanding or forbidding specific acts. It grounds the notion that there are some things that are wrong, always and everywhere, i.e., “crimes against humanity,” while avoiding the obvious difficulties of claiming that this is determined by any sort of human consensus. Nevertheless, it still sees the interplay of people in social and rational discourse as necessary to determine what in particular the natural law requires.

Updated February 24, 2024

Revised and expanded August 26, 2021

Please support the Thomistic Philosophy Page with a gift of any amount.

Share this:.

- Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.

- Subscribe Subscribed

- Copy shortlink

- Report this content

- View post in Reader

- Manage subscriptions

- Collapse this bar

15 Natural Law Examples

Natural law is a theory asserting that certain natural rights or values are inherent by virtue of human nature and can be universally understood through human reason (Coyle, 2023).

Rooted deeply in various religious and philosophical traditions around the world, Natural Law is presented as a universal guideline for human behavior (for example, the concept of Dharma in Hinduism or the teachings of Aristotle’s Nichomachean Ethics).

Different perspectives interpret natural law in diverse ways, raising debates about its origin, applications, definition, and implications (d’Entreves, 2017).

From ancient civilizations to our modern socio-political context, understanding Natural Law adds depth to the discourse on morality, ethics, and human rights.

Definition and Overview

Natural law, in its simplest form, refers to a type of moral theory that asserts the existence of objective, universal moral laws that we can decipher through plain reason and logic.

This means that these laws aren’t forged by humans but are inherently a part of human nature and the natural order of things, like the innate understanding that stealing is wrong.

This concept has deep historical roots.

Historically, the concept of natural law is tied to ancient philosophy and underpins many world religions, such as the Ten Commandments in Christianity. It posits that there is a higher moral order that transcends human-made laws (like those against infidelity which exist across various cultures and societies).

Prominent scholars, such as Aristotle and Thomas Aquinas, were influential in developing and refining the concept of natural law (Crowe, 2016).

Aristotle was the first to introduce the concept of ‘natural justice,’ while Aquinas expanded this concept to merge Christian theology with Greek philosophical thought. Aristotle argued for ‘telos’ or purpose in all natural things, while Aquinas emphasized God as the divine lawgiver.

Furthermore, natural law was invoked by enlightenment philosophers and even America’s founders, where they embraced liberal ideals such as the right to free speech , freedom of religion , and freedom of assembly .

The universality of natural law can be seen in different cultures and legal systems worldwide.

Despite its various interpretations, paradigms of natural law, emphasizing a universal moral order beyond human legislation, are apparent in diverse traditions and societies (such as the concept of ‘Maat’ in ancient Egyptian civilization, which reflects a cosmic order transcending human authority).

Natural Law Examples

1. human dignity.

Throughout cultures and histories, there exists the idea that every human being should be treated with dignity and respect just due to their nature as humans.

This principle, inherently known and accepted, is an example of natural law (Jensen, 2015). It transcends artificial boundaries and forms the basis for many human rights policies today.

Even in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, prescribed by the United Nations, the ethos of human dignity is cemented in the preamble itself: “Recognition of the inherent dignity and of the equal and inalienable rights of all members of the human family is the foundation of freedom, justice, and peace in the world” (Universal declaration, 1948).

This embodies the concept of natural law, as it puts forth a universal moral code applicable to all mankind.

See More: Examples of Human Dignity

2. Prohibition of Theft

Man made criminal laws universally acknowledge that stealing or theft is inherently morally wrong, which is in line with natural law.

Whether it’s modern jurisdictions like U.S. law that has categorized theft under various degrees (like petty theft and grand theft), or ancient civilizations like Hammurabi’s Code which prescribed explicit punishments for theft, the principle against stealing is inherently accepted across different cultures and timelines (Finnis, 2017; Haakonssen & Seidler, 2015).

This universal agreement on the moral invalidity of theft illustrates the existence of a higher moral order beyond human-made laws, presenting a real-world example of natural law.

3. Prohibition of Murder

The prohibition of murder is a clear embodiment of natural law. This law, unlike civil or criminal laws, is universally accepted and understood without the need for formal legislation.

It is inherently understood that taking another human life unjustly is morally wrong.

Whether expressed in the commandment “Thou shall not kill” in the Bible and Torah or in the laws of ancient societies like the Roman Empire that held ‘unlawful killing’ as a grave offence, the prohibition of murder illustrates the concept of natural law.

4. Right to Self-Defense

Another real-world application of natural law is the concept of self-defense. This universally accepted principle dictates that a person has the right to protect himself or herself from harm.

While different legal systems have various nuances in laws concerning self-defense, the core understanding remains consistent: everyone has a right to protect their own life when threatened (Finnis, 2015).

The United Nations’ “Basic Principles on the Use of Force and Firearms by Law Enforcement Officials” recognizes self-defense as a basic human right (Principle 9, UN BPOFFLEO, 1990). This common understanding, superseding man-made laws, asserts the presence of natural law.

5. Duty to Honor Promises and Contracts

The duty to honor promises and contracts, a pillar of trust and cooperation in human societies, suffices as an evident example of natural law.

This universally recognized principle implies that when individuals make promises or sign contracts, they are ethically and morally bound to keep their word.

Experience shows that societies function smoothly when this principle is adhered to, since it forms the bedrock of personal, professional, and legal relationships (Crowe, 2016; d’Entreves, 2017).

For example, modern legal systems enforce contractual obligations through the law of contracts, and breaching such obligations can result in substantial penalties. This reflects a commitment to the natural law principle of keeping one’s word, a concept ingrained in human relationships and dealings for centuries.

6. The Moral Law of Truth

The universally accepted principle that deception or lying is intrinsically wrong serves as another enacted facet of natural law.

The moral admonishment of lying can be found in both human legislations (for example, the perjury laws across multiple jurisdictions such as the UK’s Perjury Act of 1911) and religious and philosophical teachings (like Buddhism’s adherence to speaking the truth as part of the Eightfold Path).

This universal understanding further accentuates the concept of natural laws transcending human-made laws and societal norms.

7. Principle of Restitution

The principle of restitution, or the concept of compensating for a wrong committed, is an often cited example of natural law.

This concept states that if you harm someone either physically, emotionally, or monetarily, there is an inherent, universal obligation to make amends for the damage done.

Across the world, we see this principle in action within legal systems with laws dealing with compensation for injury or loss (Haakonssen & Seidler, 2015). For example, the U.S. legal system includes tort law, which allows victims of harm to seek compensation from the perpetrators.

8. Principle of Confidentiality and Privacy

Over the span of time and across numerous societies, a universal agreement prevails regarding the respect for an individual’s privacy.

This principle of confidentiality and privacy essentially means that there are certain aspects of one’s life that are private and should be respected by others.

Recognition of this principle is evident in both ancient cultural norms and modern legal precedents. Even under the umbrella of international law, Article 12 of the United Nations’ Universal Declaration of Human Rights emphasizes the fundamental right to privacy (stating “No one shall be subjected to arbitrary interference with his privacy”).

These examples illuminate the role of natural law in shaping our societal, ethical, and legal outlook.

9. Principle of Justice and Fairness

The principle of justice and fairness, which argues that all individuals should be treated equally and without prejudice, mirrors the concept of natural law (d’Entreves, 2017; Finnis, 2015).

This principle means that every person, irrespective of their race, religion, gender, or socio-economic status, deserves to be treated justly and fairly (for example, the principle of ‘innocent until proven guilty’, prevalent in numerous jurisdictions, stands as a testament to this inherent understanding of justice).

10. Principle of Compassion and Kindness

The universal value of compassion and kindness towards fellow living beings, often described as empathy, underscores the understanding of natural law.

Whether it’s cultural, religious, or philosophical traditions advocating for compassion (like the Golden Rule present in many religions – ‘Treat others as you would like to be treated’), or scientific studies highlighting empathy as a inherent human trait, this deep-seated understanding reflects a universal natural law.

The fact that such principles are so broadly shared and understood, despite cultural, generational, and geographical differences, speaks to their roots in the intrinsic nature of being human, making them quintessential examples of natural law.

11. Right to Acquire Property

The universally recognized right to acquire, use, enjoy, and dispose of property is another manifestation of natural law and represents the liberal idea of economic freedom .

This principle is deeply ingrained in human nature and has been a critical factor in human progress and development. From ancient systems like feudalism where land was recognised as a valuable asset, to contemporary property laws which include intellectual property rights, the inherent understanding of one’s right to acquire and control property is consistently upheld.

Today, this natural law principle is recognized by international covenants such as Article 17 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights which states: “Everyone has the right to own property alone as well as in association with others.”

12. Right to Liberty

The right to liberty, understood as the freedom to live one’s life without unwarranted restraint, represents a key aspect of natural law.

This principle affirms that each individual has an inherent right to make decisions about their own life, to express themselves freely, and to engage in the pursuit of happiness, so long as it does not infringe upon the rights of others.

Historically, the quest for liberty is reflected in numerous revolutions and movements, like the American and French Revolutions in the 18th century which were central around themes of liberty. Today, it is enshrined in numerous constitutions and international documents, such as Article 3 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights – “Everyone has the right to life, liberty, and security of person”.

These examples highlight how natural law principles continue to impact contemporary discourse, shaping societal norms, values, and legal frameworks worldwide.

13. Right to Defend Oneself

The inherent right to defend oneself from harm is a universally acknowledged natural law.

This principle supports an individual’s right to prevent harm to their physical integrity or personal property. Recognized universally, the right manifests in a spectrum of ways, from the most basic physical self-defense against personal attacks to more evolved forms like legal recourse against defamation.

This right’s universal application is endorsed in various legal systems (Jensen, 2015). An example is the ‘Stand Your Ground’ law in some U.S. states, which protects individuals who use force, including lethal force, to defend themselves without any duty to evade or retreat from a dangerous situation.

14. Parental Duties

Parental duties, or the responsibility of parents to care and provide for their offspring, is an excellent example of natural law.

This principle originates from an innate understanding that parents, owing to their role in their children’s creation and upbringing, have a responsibility to ensure their protection, survival, and growth (d’Entreves, 2017; Jensen, 2015).

For instance, parental duties are not limited to humans but are pervasive in the entire animal kingdom, where creatures exhibit protective behaviors towards their offspring (like a mother bear protecting her cubs from predators).

Moreover, nearly all nation-states recognize parental responsibility in legal terms, mandating provisions for child care, education, and safeguarding against neglect and abuse. These legislations often resonate with the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child, bolstering the common understanding of parental duties as a natural law.

15. Pursuit of Happiness

The pursuit of happiness, ingrained as an inherent human desire to seek joy and fulfillment, falls under the broad umbrella of natural law.

This principle is universally recognized as each individual’s innate right to strive toward their well-being, happiness, and personal fulfillment (Coyle, 2023).

The importance of this principle is epitomized in foundational documents such as the United States Declaration of Independence, where it is affirmed as an unalienable right alongside life and liberty. It is a commitment to individual autonomy , personal growth, and human dignity, irrespective of societal or cultural contexts – making it a core element of natural law.

Natural law encompasses universal principles and values, intrinsic to human nature, that shape our moral compass, irrespective of cultural, political or temporal differences.

From duties like making restitution or honoring contracts, to rights such as defending oneself or acquiring property, its applications are woven into the fabric of our societies, codes of law, and collective conscience.

These principles and values, often framed in scholarly discourse and applied in real-world scenarios, underline our understanding of ethics, justice, and human rights.

Dedicated exploration of natural law, thus, allows us to navigate the complexities of moral, legal, and socio-political landscapes, making it an indispensable tool in our quest to understand and enhance the human condition.

Coyle, S. (2023). Natural law and modern society . Oxford University Press.

Crowe, J. (2016). Natural law theories. Philosophy Compass , 11 (2), 91-101.

d’Entreves, A. P. (2017). Natural law: An introduction to legal philosophy . Routledge.

Finnis, J. (2015). Grounding human rights in natural law. The American Journal of Jurisprudence , 60 (2), 199-225.

Finnis, J. (2017). Natural law and legal reasoning. In Law and Morality (pp. 3-15). Routledge.

Haakonssen, K., & Seidler, M. J. (2015). Natural Law. In A Companion to Intellectual History .

Jensen, S. (2015). Knowing the natural law . CUA Press.

Chris Drew (PhD)

Dr. Chris Drew is the founder of the Helpful Professor. He holds a PhD in education and has published over 20 articles in scholarly journals. He is the former editor of the Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education. [Image Descriptor: Photo of Chris]

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 5 Top Tips for Succeeding at University

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 50 Durable Goods Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 100 Consumer Goods Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 30 Globalization Pros and Cons

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

4.4: Summary of Aquinas’s Natural Law Theory

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 22118

- Mark Dimmock & Andrew Fisher

- Torquay Boys' Grammar School & University of Nottingham via Open Book Publishers

For Aquinas everything has a function (a telos ) and the good thing(s) to do are those acts that fulfil that function. Some things such as acorns, and eyes, just do that naturally. However, humans are free and hence need guidance to find the right path. That right path is found through reasoning and generates the “internal” Natural Law. By following the Natural Law we participate in God’s purpose for us in the Eternal Law.

However, the primary precepts that derive from the Natural Law are quite general, such as, pursue good and shun evil . So we need to create secondary precepts which can actually guide our day-to-day behaviour. But we are fallible so sometimes we get these secondary precepts wrong, sometimes we get them right. When they are wrong they only reflect our apparent goods. When they are right they reflect our real goods.

Finally, however good we are because we are finite and sinful, we can only get so far with rational reflection. We need some revealed guidance and this comes in the form of Divine Law. So to return to the Euthyphro dilemma. God’s commands through the Divine Law are ways of illuminating what is in fact morally acceptable and not what determines what is morally acceptable. Aquinas rejects the Divine Command Theory.

- Table of Contents

- Random Entry

- Chronological

- Editorial Information

- About the SEP

- Editorial Board

- How to Cite the SEP

- Special Characters

- Advanced Tools

- Support the SEP

- PDFs for SEP Friends

- Make a Donation

- SEPIA for Libraries

- Entry Contents

Bibliography

Academic tools.

- Friends PDF Preview

- Author and Citation Info

- Back to Top

Locke’s Moral Philosophy

Locke’s greatest philosophical work, An Essay Concerning Human Understanding , is generally seen as a defining work of seventeenth-century empiricist epistemology and metaphysics. The moral philosophy developed in this work is rarely taken up for critical analysis, considered by many scholars of Locke’s thought to be too obscure and confusing to be taken too seriously. The view is not only seen by many commentators as incomplete, but it carries a degree of rationalism that cannot be made consistent with our picture of Locke as the arch-empiricist of his period. While it is true that Locke’s discussion of morality in the Essay is not as well-developed as many of his other views, there is reason to think that morality was the driving concern of this great work. For Locke, morality is the one area apart from mathematics wherein human reasoning can attain a level of rational certitude. For Locke, human reason may be weak with regards to our understanding of the natural world and the workings of the human mind, but it is exactly suited for the job of figuring out human moral duty. By looking at Locke’s moral philosophy, as it is developed in the Essay and some of his earlier writings, we gain a heightened appreciation for Locke’s motivations in the Essay , as well as a more nuanced understanding of the degree of Locke’s empiricism. Further than this, Locke’s moral philosophy offers us an important exemplar of seventeenth-century natural law theory, probably the predominant moral view of the period.

1.1 The puzzle of Locke’s moral philosophy

1.2 critical interpretations of locke’s moral philosophy, 2.1 morality as natural law, 2.2 morality and teleology, 2.3 morality as a deductive science, 3.1 locke’s general theory of motivation, 3.2 locke’s theory of moral motivation, 4.1 locke’s ethics of belief, 4.2 the special role of sanctions, other internet resources, related entries, 1. introduction.

There are two main stumbling blocks to the study of Locke’s moral philosophy. The first regards the singular lack of attention the subject receives in Locke’s most important and influential published works; not only did Locke never publish a work devoted to moral philosophy, but he dedicates little space to its discussion in the works he did publish. The traditional moral concept of natural law arises in Locke’s Two Treatises of Government (1690) serving as a major plank in his argument regarding the basis for civil law and the protection of individual liberty, but he does not go into any detail regarding how we come to know natural law nor how we might be obligated, or even motivated, to obey it. In his Essay Concerning Human Understanding (first edition 1690; fourth edition 1700, hereafter referred to as the Essay ) Locke spends little time discussing morality, and what he does provide in the way of a moral epistemology seems underdeveloped, offering, at best, the suggestion of what a moral system might look like rather than a fully-realized positive moral position. This brings us to the second major stumbling block: What Locke does provide us by way of moral theory in these works is diffuse, with the air of being what J.B. Schneewind has characterized as “brief, scattered and sometimes puzzling” (Schneewind 1994, 200). This is not to suggest that Locke says nothing specific or concrete about morality. Locke makes references, throughout his works, to morality and moral obligation. However, two quite distinct positions on morality seem to emerge from Locke’s works and it is this dichotomous aspect of Locke’s view that has generated the greatest degree of controversy. The first is a natural law position, which Locke refers to in the Essay , but which finds its clearest articulation in an early work from the 1660s, entitled Essays on the Law of Nature . In this work, we find Locke espousing a fairly traditional rationalistic natural law position, which consists broadly in the following three propositions: first, that moral rules are founded on divine, universal and absolute laws; second, that these divine moral laws are discernible by human reason; and third, that by dint of their divine authorship these rules are obligatory and rationally discernible as such. On the other hand, Locke also espouses a hedonistic moral theory, in evidence in his early work, but developed most fully in the Essay . This latter view holds that all goods and evils reduce to specific kinds of pleasures and pains. The emphasis here is on sanctions, and how rewards and punishments serve to provide morality with its normative force. Both elements find their way into Locke’s published works, and, as a result, Locke seems to be holding what seem to be incommensurable views. The trick for Locke scholars has been to figure out how, or even if, they can be made to cohere. The question is not easily settled by looking to Locke’s unpublished works, either, since Locke also seems to hold a natural law view at some times and a hedonistic view at others.

One might conclude, with J.B. Schneewind, among others, that Locke’s attempts at constructing a morality were unsuccessful. Schneewind does not mince words when he writes the following: “Locke’s failures are sometimes as significant as his successes. His views on morality are a case in point” (Schneewind 1994, 199). Schneewind argues that the two strands of Locke’s moral theory are irreconcilable, and that this is a fact Locke must have realized. This view is indeed an apt representation of the frustration many readers have felt with Locke’s moral theory. Locke’s eighteenth-century apologist, Catharine Trotter Cockburn thought Locke provided a promising, but incomplete, starting point for a positive moral system, imploring, in her work “A Defense of Mr. Locke’s Essay of Human Understanding ,”

I wish, Sir, you may only find it enough worth your notice, to incite you to show the world, how far it falls short of doing justice to your principles; which you may do without interrupting the great business of your life, by a work, that will be an universal benefit, and which you have given the world some right to exact of you. Who is there so capable of pursuing to a demonstration those reflections on the grounds of morality , which you have already made? (Cockburn 1702, 36)

Locke’s friend William Molyneux similarly implored Locke to make good on the promise found in the Essay . In a letter written to Locke on September 16 th , 1693, Molyneux presses Locke to work on a moral treatise once he has finished editing the second edition of his Essay , writing as follows:

I am very sensible how closely you are engaged, till you have discharged this Work off your Hands; and therefore will not venture, till it be over, to press you again to what you have promis’d in the Business of Man’s Life, Morality . (Locke 1742, 53)

Several months later, in December of the same year, Molyneux concludes a letter by asking Locke about what other projects he currently has on the go “amongst which, I hope you will not forget your Thoughts on Morality ” (Locke 1742, 54).

Locke never did produce such a work, and we might well wonder if he himself ever considered the project a “failure”. There is no doubt that morality was of central importance to Locke, a fact we can discern from the Essay itself; there are two important features of the Essay that serve to enlighten us regarding the significance of this work in the development of Locke’s moral views. First of all, morality seems to have inspired Locke to write the Essay in the first place. In recounting his original inclination to embark on the project, he recalls a discussion with “five or six friends”, at which they discoursed “on a Subject very remote from this” (Locke 1700, 7). According to Locke, the discussion eventually hit a standstill, at which point it was agreed that in order to settle the issue at hand it would first be necessary to, as Locke puts it, “examine our own Abilities, and see, what Objects our Understandings were, or were not fitted to deal with” (Locke 1700, 7). This was, he explains, his first entrance into the problems that inspired the Essay itself. But, what is most interesting for our purposes is just what the remote subject was that first got Locke and his friends thinking about fundamental questions of epistemology. James Tyrell, one of those who attended that evening, is a source of enlightenment on this matter—he later recalled that the discussion concerned morality and revealed religion. But, Locke himself refers to the subjects they discussed that fateful evening as ‘very remote’ from the matters of the Essay . That may well be, but it is also true that Locke, in the Essay , identifies morality as a central feature of human intellectual and practical life, which brings us to the second important fact about Locke’s view of morality. Locke writes, in the Essay , that “Morality is the proper Science, and Business of Mankind in general” ( Essay , 4.12.11; these number are, book, chapter and section, respectively, from Locke’s Essay ). For a book aiming to set out the limits and extent of human knowledge, this comes as no small claim. We must, Locke writes, “know our own Strength” ( Essay , 1.1.6) and turn our attention to those areas in which we can have certainty, i.e., “those [things] which concern our Conduct” ( Essay , 1.1.6). The amount of attention given to the question of morality itself would seem to belie its primacy for Locke. The Essay is certainly not intended as a work of moral philosophy; it is a work of epistemology, laying the foundations for knowledge. However, a very big part of the programme involves identifying what true knowledge is and what it is we as humans can have knowledge about, and morality is accorded a distinctive and fairly exclusive status in Locke’s epistemology as one of “the Sciences capable of Demonstration” ( Essay , 4.3.18). The only other area of inquiry accorded this status is mathematics; clearly, for Locke, morality represents a unique and defining aspect of what it means to be human. We have to conclude, then, that the Essay is strongly motivated by an interest in establishing the groundwork for moral reasoning. However, while morality clearly has a position of the highest regard in his epistemological system, his promise of a demonstrable moral science is never realized here, or in later works.

It seems we can safely say that the subject of morality was a weighty one for Locke. However, just what Locke takes morality to involve is substantially more complicated an issue. There are two broad lines of interpretation of Locke’s moral views, which I will briefly outline here.

The first interpretation of Locke’s moral theory is what we might call an incompatibility thesis: Locke scholars Laslett, Aaron, von Leyden, among others, hold that Locke’s natural law theory is nothing more than a relic from Locke’s early years, when he wrote the Essays on the Law of Nature , and represents a rogue element in the mature empiricist framework of the Essay . For these commentators, the two elements found in the Essay seem not only incommensurable, but the hedonism seems the obvious and straightforward fit with Locke’s generally empiricist epistemology. The general view is that Locke’s rationalism seems, for all intents and purposes, to have no significant role to play, either in the acquisition of moral knowledge or in the recognition of the obligatory force of moral rules. These fundamental aspects of morality seem to be taken care of by Locke’s hedonism. Worse than this, however, is that the two views rely on radically different epistemological principles. The conclusion tends to be that Locke is holding on to moral rationalism in the face of serious incoherence. The incompatibility thesis is supported by the fact that Locke seems to emphasize the role of pleasure and pain in moral decision-making, however it has difficulty making sense of the presence of Locke’s moral rationalism in the Essay and other of Locke’s later works (not to mention the exalted role he gives to rationally-deduced moral law). Added to this, even in Locke’s early work, he seems to hold both positions simultaneously. Aaron and von Leyden both throw up their hands. According to von Leyden, in the introduction to his 1954 edition of Locke’s Essays on the Law of Nature ,

the development of [Locke’s] hedonism and certain other views held by him in later years made it indeed difficult for him to adhere whole-heartedly to his doctrine of natural law. (Locke 1954, 14)

In a similar vein, Aaron writes:

Two theories compete with each other in [Locke’s] mind. Both are retained; yet their retention means that a consistent moral theory becomes difficult to find. (Aaron 1971, 257)

Yet, it is curious that Locke neither claimed to find these strands incompatible, nor ever abandoned his rationalistic natural law view. It seems unlikely that this view would be nothing more than a confusing hangover from earlier days. Taking seriously Locke’s commitment to both is therefore a much more charitable approach, and one that takes seriously Locke’s clear commitment to the benefits of rationally-apprehending our moral duties. An approach along these lines is one we might call a compatibility approach to the question of Locke’s moral commitments. John Colman and Stephen Darwall are two Locke scholars who have argued that Locke’s view is neither plagued with tensions nor incoherent. Their common view is that the two elements of Locke’s theory are doing different work. Locke’s hedonism, on this compatibility account, is intended as a theory of moral motivation, and serves to fill a motivational gap between knowing moral law and having reasons to obey moral law. Locke introduces hedonism in order to account for the practical force of the obligations arising from natural law. As Darwall writes,

what makes God’s commands morally obligatory [i.e., God’s authority] appears…to have nothing intrinsically to do with what makes them rationally compelling. (Darwall 1995, 37).

Thus, on this account, reason deduces natural law, but it is hedonistic considerations alone that offer agents the motivating reasons to act in accordance with its dictates.

This interpretation convincingly makes room for both elements in Locke’s view. A central feature of this interpretation is its attention to the legalistic aspect of Locke’s natural law theory. For Locke, the very notion of law presupposes an authority structure as the basis for its institution and its enforcement. The law carries obligatory weight by virtue of its reflecting the will of a rightful superior. That it also carries the threat of sanctions lends motivational force to the law.

A slight modification of the compatibility account, however, better captures the motivational aspect of Locke’s rationalistic account: Locke does, at times suggest that rational agents are not only obligated, but motivated, by sheer recognition of the divine authority of moral law. It is helpful to think of morality as carrying both intrinsic and extrinsic obligatory force for Locke. On the one hand moral rules obligate by dint of their divine righteousness, and on the other hand by the threat of rewards and punishments. The suggestion that morality has an intrinsic motivational force appears in the Essays on the Law of Nature and is retained by Locke in some of his final published works. It is, however, a feature of his view that gets somewhat underappreciated in the secondary literature, and for understandable reasons—Locke tends to emphasize hedonistic motivations. Why this is will be discussed in section 4 . At this point, however, it suffices to say that Locke’s theory does not have the motivational gap that the compatibility thesis suggests—hedonism serves as a ‘back-up’ motivational tool in the absence of the right degree of rational intuition of one’s moral duty.

2. Locke’s natural law theory: the basis of moral obligation

In order to get a complete understanding of Locke’s moral theory, it is useful to begin with a look at Locke’s natural law view, articulated most fully in his Essays on the Law of Nature (written as series of lectures he delivered as Censor of Moral Philosophy at Christ Church, Oxford). Two predominant features of Locke’s natural law theory are already well-developed in this work: the rationalism and the legalism. According to Locke, reason is the primary avenue by which humans come to understand moral rules, and it is via reason we can draw two distinct but related conclusions regarding the grounds for our moral obligations: we can appreciate the divine, and thereby righteous, nature of morality and we can perceive that morality is the expression of a law-making authority.

In the Essays on the Law of Nature , Locke writes that “all the requisites of a law are found in natural law” (Locke 1663–4, 82). But, what, for Locke, is required for something to be a law? Locke takes stock of what constitutes law in order to establish the legalistic framework for morality: First, law must be founded on the will of a superior. Second, it must perform the function of establishing rules of behavior. Third, it must be binding on humans, since there is a duty of compliance owed to the superior authority that institutes the laws (Locke 1663–4, 83). Natural law is rightly called law because it satisfies these conditions. For Locke, the concept of morality is best understood by reference to a law-like authority structure, for without this, he argues, moral rules would be indistinguishable from social conventions. In one his later essays, “Of Ethic in General”, Locke writes

[w]ithout showing a law that commands or forbids [people], moral goodness will be but an empty sound, and those actions which the schools here call virtues or vices may by the same authority be called by contrary names in another country; and if there be nothing more than their decisions and determinations in the case, they will be still nevertheless indifferent as to any man’s practice, which will by such kind of determinations be under no obligation to observe them. (Locke 1687–88, 302)