An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Elsevier - PMC COVID-19 Collection

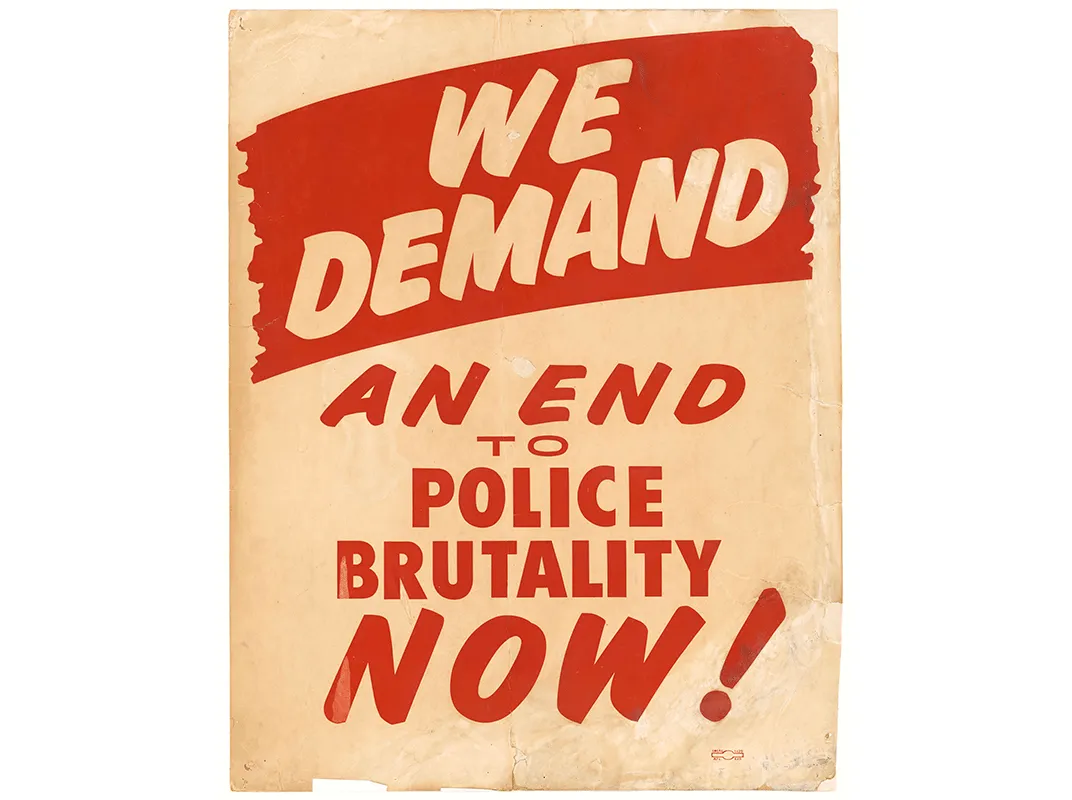

Police brutality and racism in America

The Schwartzreport tracks emerging trends that will affect the world, particularly the United States. For EXPLORE it focuses on matters of health in the broadest sense of that term, including medical issues, changes in the biosphere, technology, and policy considerations, all of which will shape our culture and our lives.

After getting arrested several times for participating in civil rights demonstrations as I walked down Constitution Avenue, past what were then known as the Old Navy buildings, now long gone, on that warm Wednesday afternoon on the 28th of August 1963, I thought we had reached the turning point. I and thousands of others were moving quietly and peacefully towards the Lincoln Memorial where we were going to hear the Reverend Martin Luther King give what history now knows as the “I have a Dream" speech.

I was walking with a Black friend, a reporter for The Washington Star, an historic paper now long gone. I looked over Richard's shoulder and saw walking next to us two young partners of the then conservative Republican law firm, Covington & Burling. Richard saw where I was looking and turned to watch them as well. To him they were just two more White men; a large proportion of the crowd were White, and men. When I explained who they were he smiled, and I said, “I think we've won.” It was such a happy day; I remember it still.

And a little less than a year later, on 2 July 1964, almost unthinkably, a Southern politician, President Lyndon Johnson, signed into law the bipartisan Civil Rights Act of 1964, which prohibited discrimination in public places, provided for the integration of public schools, and facilities, and made employment discrimination based on race illegal. It seemed Dr. King's dream was coming true.

Then a year after that when Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which outlawed discriminatory voting practices, such as literacy tests and poll taxes, I thought all was now well. It had taken a hundred years, since the end of the Civil War, but we were finally throttling the monster of racism.

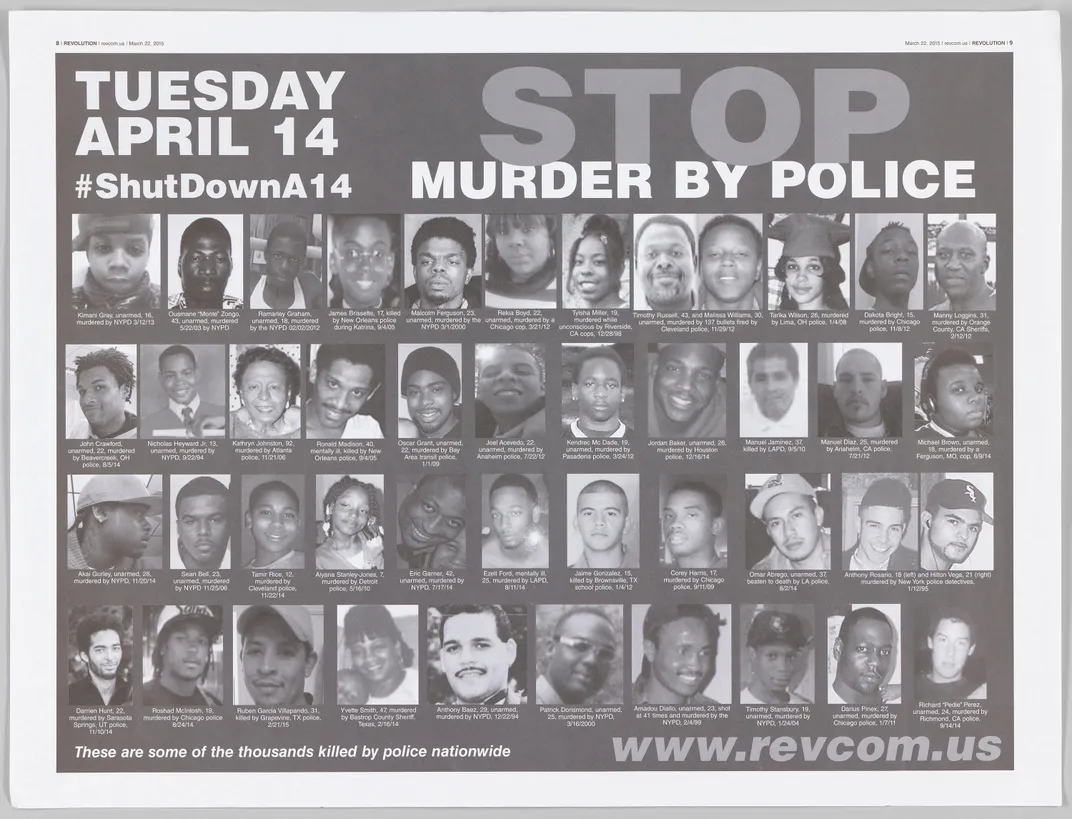

And yet here I sit, looking day after day at the searing television images of the new civil rights demonstrations, watching videos of White policemen murdering Black men for no reason except they could, thinking they would get away with it, as they had so often in the past. The mass demonstrations with their clouds of tear gas and rubber bullets. The gross misuse of the American military against American citizens. The eight minutes and 46 seconds of video showing four policemen in Minneapolis murdering an unarmed handcuffed Black man, George Floyd, as he lay in the street handcuffed, that has caused, as I write this, 19 days of civil rights demonstrations involving millions all over the world.

It is important to remember also, I think, that this historic event, the murder and everything that has followed from that death is known to us only because of the bravery of one 17-year old girl, Darnell Frazier, who would not be intimidated and kept her phone camera on creating a video record of what was happening. As her hometown paper, the Star Tribune reported, Frazier wasn't looking to be a hero. She was “just a 17-year-old high school student, with a boyfriend and a job at the mall, who did the right thing. She's the Rosa Parks of her generation.” 1 I completely agree. I have written often about the power of a single individual at the right moment. 2 Could there be a clearer example?

What made this event historic, so catalyzing, so emotionally powerful that people all over the world in their millions took to the streets, even though it could mean their life because the Covid-19 pandemic which, in the U.S. alone, had infected over two million people and was still killing a thousand people a day? I think it was because it illustrated the conjunction of two major trends in America: the blatant racism that still infects the country, and the racially biased police brutality which has become outrageous.

George Floyd is one of a thousand police killings that will probably happen in 2020. There were that many last year. The statistics about American law enforcement are astounding when compared to those of other developed nations, like those that make up the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). According to Statistia in the U.S. there have been, “a total (of) 429 civilians ...shot, 88 of whom were Black, as of June 4, 2020. In 2018, there were 996 fatal police shootings, and in 2019 increased to 1004 (see Figure 1). Additionally, the rate of fatal police shootings among Black Americans was much higher than that for any other ethnicity, standing at 30 fatal shootings per million of the population as of June 2020.” 3

Credit: The Washington Post.

By way of contrast, in Norway, which I pick because it is a nation with high gun ownership, the police in 2019 armed themselves and displayed weapons 42 times, and fired two guns once each, and no one was killed. Few Americans even realize that “A police officer does not have to shoot to kill and, in several countries, a police officer does not even have to carry a gun. In Norway, Iceland, New Zealand, Britain, and Ireland, police officers generally do not carry firearms.” 4

Intermixed with racial brutality on the part of the law enforcement system in the U.S. is the gross misuse of the American military against the American people they are sworn to protect. And then there is the American gulag. It's prisons and jails dot our national landscape holding millions of incarcerated men and women a large majority of them Black and Brown.

Until this June I don't think most Americans really understood how violent and racist policing in America has become. If you are White like me, professional and relatively affluent, you never have any interactions with the police. They don't come to your door, and should it happen that you are stopped for a traffic ticket you don't feel threatened; it is no more than an annoyance that is going to cost you a few dollars for the fine. And even then, how often does that happen? I haven't been stopped since 1973, when a taillight on my car had gone out without my noticing. You see the police, they are there. But it is not an issue.

But if you are Black or Brown you live in another world.

Three weeks before George Floyd was murdered during a traffic stop by four police officers, an exhaustive study carried out by a research team at Stanford University led by Emma Pierson and Camelia Simoiu, was published in Nature Human Behavior Entitled, “A Large-scale Analysis of Racial Disparities in Police stops Across the United States”. It presented the truth of America, and it is horrifying.

“We assessed racial disparities in policing in the United States by compiling and analysing a dataset detailing nearly 100 million traffic stops conducted across the country. We found that black drivers were less likely to be stopped after sunset, when a ‘veil of darkness’ masks one's race, suggesting bias in stop decisions. Furthermore, by examining the rate at which stopped drivers were searched and the likelihood that searches turned up contraband, we found evidence that the bar for searching black and Hispanic drivers was lower than that for searching white drivers. Finally, we found that legalization of recreational marijuana reduced the number of searches of white, black and Hispanic drivers—but the bar for searching black and Hispanic drivers was still lower than that for white drivers post-legalization. Our results indicate that police stops and search decisions suffer from persistent racial bias and point to the value of policy interventions to mitigate these disparities.” 5

Some years ago I was on the board of a foundation to help children in medical distress. Also on the board was the then Deputy Chief of Police of the Los Angeles Police Department. We became friendly and one night went out to dinner together after a board meeting. This was not long after the 1992 riots that occurred when Rodney King, a Black man, was savagely beaten by police in a traffic stop. I asked the Deputy Chief, who had told me he had risen through the ranks and been a sworn officer for almost 30 years, how many police officers would participate in something like the King beating? I have never forgotten his answer. He said, “About 15% of police are heroes, the very best you could ever ask for. Another 15% are thugs and bullies who become police because they think they can act out without fear of punishment. The remaining 70% go with the flow. If they are with heroes, they behave heroically; if they are assigned to work with thugs, well bad things happen.” He explained that what he was trying to do was identify the thugs before they were hired. And to break through the “Blue Wall” if they were hired. He told me it was not easy, and one of the problems was the police union which protected its members at all cost.

How bad is it? I mean real numbers, not just the conjecture and political commentary that fills the airwaves. It turns out that it is very hard to get this information. Because of the power of the police unions and the racism of the U.S. Congress under the last four presidents, both Democrats and Republicans — Bill Clinton, George W. Bush, Barrack Obama, and Donald Trump — as police violence has grown worse each year, creating a real federal data base on police violence has proven almost impossible.

Congress passed H.R. 3355 Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994. 6 It provided funds for local and state law enforcement entities and the State Attorney Generals to “acquire data about the use of excessive force by law enforcement officers” across the nation and to “publish an annual summary of the data acquired.” It didn't go well. In 1996, the Institute for Law and Justice and the National Institute of Justice on behalf of the DOJ, in a carefully worded report, described the failure to do what was mandated two years earlier. “Systematically collecting information on use of force from the Nation's more than 17,000 law enforcement agencies is difficult given the lack of standard definitions, the variety of incident recording practices, and the sensitivity of the issue.” 7

So in 2020, do we know any more? We do, although still far from enough. In 2019, a research team led by Frank Edwards of the School of Criminal Justice at Rutgers University, published a report, “Risk of being killed by police use-of-foce in the U.S. by age, race/ethnicity, and sex.” They reported:

“We use novel data on police-involved deaths to estimate how the risk of being killed by police use-of-force in the United States varies across social groups. We estimate the lifetime and age-specific risks of being killed by police by race and sex. We also provide estimates of the proportion of all deaths accounted for by police use-of-force. We find that African American men and women, American Indian / Alaska Native men and women, and Latino men face higher lifetime risk of being killed by police than do their white peers. We find that Latino women and Asian / Pacific Islander men and women face lower risk of being killed by police than do their white peers. Risk is highest for Black men, who (at current levels of risk) face about a 1 in 1000 chance of being killed by police over the life course. The average lifetime odds of being killed by police are about 1 in 2000 for men and about 1 in 33,000 for women. Risk peaks between the ages of 20 and 35 for all groups. For young men of color, police use-of-force is among the leading causes of death.” 8

Just to put that in a little finer focus, what they are saying is: “African American men were about 2 1 / 2 times more likely than White men to be killed by police. Men of color face a non-trivial lifetime risk of being killed by police” 9

The Washington Post looked into this issue and tuned the data even finer: “Although half of the people shot and killed by police are white, black Americans are shot at a disproportionate rate. They account for just 13 percent of the U.S. population, but more than a quarter of police shooting victims. The disparity is even more pronounced among unarmed victims, of whom more than a third are black.” 10

And if you are Black or Brown, while being murdered is the worst case scenario it is not the only misery that awaits any interaction with America's racist police. A study carried out by Megan T. Stevenson and Sandra Mayson that was published in 2018 in The Boston University Law Review described the reality of being a Black person on the streets of America. In doing their research Stevenson and Mayson discovered first that the hysteria about crime built up in America by conservative politicians and commentators, who are overwhelmingly White, is unfounded. “the number of misdemeanor arrests and cases filed have declined markedly in recent years. In fact, national arrest rates for almost every misdemeanor offense category have been declining for at least two decades, and the misdemeanor arrest rate was lower in 2014 than in 1995 in almost every state for which data is available.” 11

But they also found, “there is profound racial disparity in the misdemeanor arrest rate for most—but not all—offense types. This is sobering if not surprising. More unexpectedly, perhaps, the variation in racial disparity across offense types has remained remarkably constant over the past thirty-seven years; the offenses marked by the greatest racial disparity in arrest rates in 1980 are more or less the same as those marked by greatest racial disparity today.” 12

The truth that almost none of us who are White get is that 57 years after Martin Luther King's I Have a Dream speech, 56 years after the Civil Rights act of 1964, and 55 years after the Voting Rights Act of 1965, if you are Black or Brown, and particularly if you are a young Black man, for you America is like living in an occupied country where any interaction with the police is to be avoided. It can send you to prison for a trivial offense at the least, and may, and often does, result in your murder at the hands of those whose supposed but not actual job is to “serve and protect.”

Speaking as a White man, I am fed up with that, and I think that this November all of us who are White and who believe the function of the state should be to foster wellbeing at every level, for everyone, need to check off our ballots only for candidates who are willing to do that, and vote out of office all politicians not so committed. What do you think?

Scientist, futurist, and award-winning author and novelist Stephan A. Schwartz , is a Distinguished Consulting Faculty of Saybrook University, and a BIAL Fellow. He is an award winning author of both fiction and non-fiction, columnist for the journal EXPLORE, and editor of the daily web publication Schwartzreport.net in both of which he covers trends that are affecting the future. For over 40 years, as an experimentalist, he has been studying the nature of consciousness, particularly that aspect independent of space and time. Schwartz is part of the small group that founded modern Remote Viewing research, and is the principal researcher studying the use of Remote Viewing in archaeology. In addition to his own non-fiction works and novels, he is the author of more than 200 technical reports, papers, and academic book chapters. In addition to his experimental studies he has written numerous magazine articles for Smithsonian, OMNI, American History, American Heritage, The Washington Post, The New York Times, as well as other magazines and newspapers. He is the recipient of the Parapsychological Association Outstanding Contribution Award, OOOM Magazine (Germany) 100 Most Inspiring People in the World award, and the 2018 Albert Nelson Marquis Award for Outstanding Contributions.

Featured Topics

Featured series.

A series of random questions answered by Harvard experts.

Explore the Gazette

Read the latest.

Forget ‘doomers.’ Warming can be stopped, top climate scientist says

Finding middle way out of Gaza war

Roadmap to Gaza peace may run through Oslo

Protesters take a knee in front of New York City police officers during a solidarity rally for George Floyd, June 4, 2020.

AP Photo/Frank Franklin II

Solving racial disparities in policing

Colleen Walsh

Harvard Staff Writer

Experts say approach must be comprehensive as roots are embedded in culture

“ Unequal ” is a multipart series highlighting the work of Harvard faculty, staff, students, alumni, and researchers on issues of race and inequality across the U.S. The first part explores the experience of people of color with the criminal justice legal system in America.

It seems there’s no end to them. They are the recent videos and reports of Black and brown people beaten or killed by law enforcement officers, and they have fueled a national outcry over the disproportionate use of excessive, and often lethal, force against people of color, and galvanized demands for police reform.

This is not the first time in recent decades that high-profile police violence — from the 1991 beating of Rodney King to the fatal shooting of Michael Brown in 2014 — ignited calls for change. But this time appears different. The police killings of Breonna Taylor in March, George Floyd in May, and a string of others triggered historic, widespread marches and rallies across the nation, from small towns to major cities, drawing protesters of unprecedented diversity in race, gender, and age.

According to historians and other scholars, the problem is embedded in the story of the nation and its culture. Rooted in slavery, racial disparities in policing and police violence, they say, are sustained by systemic exclusion and discrimination, and fueled by implicit and explicit bias. Any solution clearly will require myriad new approaches to law enforcement, courts, and community involvement, and comprehensive social change driven from the bottom up and the top down.

While police reform has become a major focus, the current moment of national reckoning has widened the lens on systemic racism for many Americans. The range of issues, though less familiar to some, is well known to scholars and activists. Across Harvard, for instance, faculty members have long explored the ways inequality permeates every aspect of American life. Their research and scholarship sits at the heart of a new Gazette series starting today aimed at finding ways forward in the areas of democracy; wealth and opportunity; environment and health; and education. It begins with this first on policing.

Harvard Kennedy School Professor Khalil Gibran Muhammad traces the history of policing in America to “slave patrols” in the antebellum South, in which white citizens were expected to help supervise the movements of enslaved Black people.

Photo by Martha Stewart

The history of racialized policing

Like many scholars, Khalil Gibran Muhammad , professor of history, race, and public policy at the Harvard Kennedy School , traces the history of policing in America to “slave patrols” in the antebellum South, in which white citizens were expected to help supervise the movements of enslaved Black people. This legacy, he believes, can still be seen in policing today. “The surveillance, the deputization essentially of all white men to be police officers or, in this case, slave patrollers, and then to dispense corporal punishment on the scene are all baked in from the very beginning,” he told NPR last year.

Slave patrols, and the slave codes they enforced, ended after the Civil War and the passage of the 13th amendment, which formally ended slavery “except as a punishment for crime.” But Muhammad notes that former Confederate states quickly used that exception to justify new restrictions. Known as the Black codes, the various rules limited the kinds of jobs African Americans could hold, their rights to buy and own property, and even their movements.

“The genius of the former Confederate states was to say, ‘Oh, well, if all we need to do is make them criminals and they can be put back in slavery, well, then that’s what we’ll do.’ And that’s exactly what the Black codes set out to do. The Black codes, for all intents and purposes, criminalized every form of African American freedom and mobility, political power, economic power, except the one thing it didn’t criminalize was the right to work for a white man on a white man’s terms.” In particular, he said the Ku Klux Klan “took about the business of terrorizing, policing, surveilling, and controlling Black people. … The Klan totally dominates the machinery of justice in the South.”

When, during what became known as the Great Migration, millions of African Americans fled the still largely agrarian South for opportunities in the thriving manufacturing centers of the North, they discovered that metropolitan police departments tended to enforce the law along racial and ethnic lines, with newcomers overseen by those who came before. “There was an early emphasis on people whose status was just a tiny notch better than the folks whom they were focused on policing,” Muhammad said. “And so the Anglo-Saxons are policing the Irish or the Germans are policing the Irish. The Irish are policing the Poles.” And then arrived a wave of Black Southerners looking for a better life.

In his groundbreaking work, “ The Condemnation of Blackness: Race, Crime, and the Making of Modern Urban America ,” Muhammad argues that an essential turning point came in the early 1900s amid efforts to professionalize police forces across the nation, in part by using crime statistics to guide law enforcement efforts. For the first time, Americans with European roots were grouped into one broad category, white, and set apart from the other category, Black.

Citing Muhammad’s research, Harvard historian Jill Lepore has summarized the consequences this way : “Police patrolled Black neighborhoods and arrested Black people disproportionately; prosecutors indicted Black people disproportionately; juries found Black people guilty disproportionately; judges gave Black people disproportionately long sentences; and, then, after all this, social scientists, observing the number of Black people in jail, decided that, as a matter of biology, Black people were disproportionately inclined to criminality.”

“History shows that crime data was never objective in any meaningful sense,” Muhammad wrote. Instead, crime statistics were “weaponized” to justify racial profiling, police brutality, and ever more policing of Black people.

This phenomenon, he believes, has continued well into this century and is exemplified by William J. Bratton, one of the most famous police leaders in recent America history. Known as “America’s Top Cop,” Bratton led police departments in his native Boston, Los Angeles, and twice in New York, finally retiring in 2016.

Bratton rejected notions that crime was a result of social and economic forces, such as poverty, unemployment, police practices, and racism. Instead, he said in a 2017 speech, “It is about behavior.” Through most of his career, he was a proponent of statistically-based “predictive” policing — essentially placing forces in areas where crime numbers were highest, focused on the groups found there.

Bratton argued that the technology eliminated the problem of prejudice in policing, without ever questioning potential bias in the data or algorithms themselves — a significant issue given the fact that Black Americans are arrested and convicted of crimes at disproportionately higher rates than whites. This approach has led to widely discredited practices such as racial profiling and “stop-and-frisk.” And, Muhammad notes, “There is no research consensus on whether or how much violence dropped in cities due to policing.”

Gathering numbers

In 2015 The Washington Post began tracking every fatal shooting by an on-duty officer, using news stories, social media posts, and police reports in the wake of the fatal police shooting of Brown, a Black teenager in Ferguson, Mo. According to the newspaper, Black Americans are killed by police at twice the rate of white Americans, and Hispanic Americans are also killed by police at a disproportionate rate.

Such efforts have proved useful for researchers such as economist Rajiv Sethi .

A Joy Foundation Fellow at the Harvard Radcliffe Institute , Sethi is investigating the use of lethal force by law enforcement officers, a difficult task given that data from such encounters is largely unavailable from police departments. Instead, Sethi and his team of researchers have turned to information collected by websites and news organizations including The Washington Post and The Guardian, merged with data from other sources such as the Bureau of Justice Statistics, the Census, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

A Joy Foundation Fellow at the Harvard Radcliffe Institute, Rajiv Sethi is investigating the use of lethal force by law enforcement officers,

Courtesy photo

They have found that exposure to deadly force is highest in the Mountain West and Pacific regions relative to the mid-Atlantic and northeastern states, and that racial disparities in relation to deadly force are even greater than the national numbers imply. “In the country as a whole, you’re about two to three times more likely to face deadly force if you’re Black than if you are white” said Sethi. “But if you look at individual cities separately, disparities in exposure are much higher.”

Examining the characteristics associated with police departments that experience high numbers of lethal encounters is one way to better understand and address racial disparities in policing and the use of violence, Sethi said, but it’s a massive undertaking given the decentralized nature of policing in America. There are roughly 18,000 police departments in the country, and more than 3,000 sheriff’s offices, each with its own approaches to training and selection.

“They behave in very different ways, and what we’re finding in our current research is that they are very different in the degree to which they use deadly force,” said Sethi. To make real change, “You really need to focus on the agency level where organizational culture lies, where selection and training protocols have an effect, and where leadership can make a difference.”

Sethi pointed to the example of Camden, N.J., which disbanded and replaced its police force in 2013, initially in response to a budget crisis, but eventually resulting in an effort to fundamentally change the way the police engaged with the community. While there have been improvements, including greater witness cooperation, lower crime, and fewer abuse complaints, the Camden case doesn’t fit any particular narrative, said Sethi, noting that the number of officers actually increased as part of the reform. While the city is still faced with its share of problems, Sethi called its efforts to rethink policing “important models from which we can learn.”

Fighting vs. preventing crime

For many analysts, the real problem with policing in America is the fact that there is simply too much of it. “We’ve seen since the mid-1970s a dramatic increase in expenditures that are associated with expanding the criminal legal system, including personnel and the tasks we ask police to do,” said Sandra Susan Smith , Daniel and Florence Guggenheim Professor of Criminal Justice at HKS, and the Carol K. Pforzheimer Professor at the Radcliffe Institute. “And at the same time we see dramatic declines in resources devoted to social welfare programs.”

“You can have all the armored personnel carriers you want in Ferguson, but public safety is more likely to come from redressing environmental pollution, poor education, and unfair work,” said Brandon Terry, assistant professor of African and African American Studies and social studies.

Kris Snibble/Harvard file photo

Smith’s comment highlights a key argument embraced by many activists and experts calling for dramatic police reform: diverting resources from the police to better support community services including health care, housing, and education, and stronger economic and job opportunities. They argue that broader support for such measures will decrease the need for policing, and in turn reduce violent confrontations, particularly in over-policed, economically disadvantaged communities, and communities of color.

For Brandon Terry , that tension took the form of an ice container during his Baltimore high school chemistry final. The frozen cubes were placed in the middle of the classroom to help keep the students cool as a heat wave sent temperatures soaring. “That was their solution to the building’s lack of air conditioning,” said Terry, a Harvard assistant professor of African and African American Studies and social studies. “Just grab an ice cube.”

Terry’s story is the kind many researchers cite to show the negative impact of underinvesting in children who will make up the future population, and instead devoting resources toward policing tactics that embrace armored vehicles, automatic weapons, and spy planes. Terry’s is also the kind of tale promoted by activists eager to defund the police, a movement begun in the late 1960s that has again gained momentum as the death toll from violent encounters mounts. A scholar of Martin Luther King Jr., Terry said the Civil Rights leader’s views on the Vietnam War are echoed in the calls of activists today who are pressing to redistribute police resources.

“King thought that the idea of spending many orders of magnitude more for an unjust war than we did for the abolition of poverty and the abolition of ghettoization was a moral travesty, and it reflected a kind of sickness at the core of our society,” said Terry. “And part of what the defund model is based upon is a similar moral criticism, that these budgets reflect priorities that we have, and our priorities are broken.”

Terry also thinks the policing debate needs to be expanded to embrace a fuller understanding of what it means for people to feel truly safe in their communities. He highlights the work of sociologist Chris Muller and Harvard’s Robert Sampson, who have studied racial disparities in exposures to lead and the connections between a child’s early exposure to the toxic metal and antisocial behavior. Various studies have shown that lead exposure in children can contribute to cognitive impairment and behavioral problems, including heightened aggression.

“You can have all the armored personnel carriers you want in Ferguson,” said Terry, “but public safety is more likely to come from redressing environmental pollution, poor education, and unfair work.”

Policing and criminal justice system

Alexandra Natapoff , Lee S. Kreindler Professor of Law, sees policing as inexorably linked to the country’s criminal justice system and its long ties to racism.

“Policing does not stand alone or apart from how we charge people with crimes, or how we convict them, or how we treat them once they’ve been convicted,” she said. “That entire bundle of official practices is a central part of how we govern, and in particular, how we have historically governed Black people and other people of color, and economically and socially disadvantaged populations.”

Unpacking such a complicated issue requires voices from a variety of different backgrounds, experiences, and fields of expertise who can shine light on the problem and possible solutions, said Natapoff, who co-founded a new lecture series with HLS Professor Andrew Crespo titled “ Policing in America .”

In recent weeks the pair have hosted Zoom discussions on topics ranging from qualified immunity to the Black Lives Matter movement to police unions to the broad contours of the American penal system. The series reflects the important work being done around the country, said Natapoff, and offers people the chance to further “engage in dialogue over these over these rich, complicated, controversial issues around race and policing, and governance and democracy.”

Courts and mass incarceration

Much of Natapoff’s recent work emphasizes the hidden dangers of the nation’s misdemeanor system. In her book “ Punishment Without Crime: How Our Massive Misdemeanor System Traps the Innocent and Makes America More Unequal ,” Natapoff shows how the practice of stopping, arresting, and charging people with low-level offenses often sends them down a devastating path.

“This is how most people encounter the criminal apparatus, and it’s the first step of mass incarceration, the initial net that sweeps people of color disproportionately into the criminal system,” said Natapoff. “It is also the locus that overexposes Black people to police violence. The implications of this enormous net of police and prosecutorial authority around minor conduct is central to understanding many of the worst dysfunctions of our criminal system.”

One consequence is that Black and brown people are incarcerated at much higher rates than white people. America has approximately 2.3 million people in federal, state, and local prisons and jails, according to a 2020 report from the nonprofit the Prison Policy Initiative. According to a 2018 report from the Sentencing Project, Black men are 5.9 times as likely to be incarcerated as white men and Hispanic men are 3.1 times as likely.

Reducing mass incarceration requires shrinking the misdemeanor net “along all of its axes” said Natapoff, who supports a range of reforms including training police officers to both confront and arrest people less for low-level offenses, and the policies of forward-thinking prosecutors willing to “charge fewer of those offenses when police do make arrests.”

She praises the efforts of Suffolk County District Attorney Rachael Rollins in Massachusetts and George Gascón, the district attorney in Los Angeles County, Calif., who have pledged to stop prosecuting a range of misdemeanor crimes such as resisting arrest, loitering, trespassing, and drug possession. “If cities and towns across the country committed to that kind of reform, that would be a profoundly meaningful change,” said Natapoff, “and it would be a big step toward shrinking our entire criminal apparatus.”

Retired U.S. Judge Nancy Gertner cites the need to reform federal sentencing guidelines, arguing that all too often they have been proven to be biased and to result in packing the nation’s jails and prisons.

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard file photo

Sentencing reform

Another contributing factor in mass incarceration is sentencing disparities.

A recent Harvard Law School study found that, as is true nationally, people of color are “drastically overrepresented in Massachusetts state prisons.” But the report also noted that Black and Latinx people were less likely to have their cases resolved through pretrial probation — a way to dismiss charges if the accused meet certain conditions — and receive much longer sentences than their white counterparts.

Retired U.S. Judge Nancy Gertner also notes the need to reform federal sentencing guidelines, arguing that all too often they have been proven to be biased and to result in packing the nation’s jails and prisons. She points to the way the 1994 Crime Bill (legislation sponsored by then-Sen. Joe Biden of Delaware) ushered in much harsher drug penalties for crack than for powder cocaine. This tied the hands of judges issuing sentences and disproportionately punished people of color in the process. “The disparity in the treatment of crack and cocaine really was backed up by anecdote and stereotype, not by data,” said Gertner, a lecturer at HLS. “There was no data suggesting that crack was infinitely more dangerous than cocaine. It was the young Black predator narrative.”

The First Step Act, a bipartisan prison reform bill aimed at reducing racial disparities in drug sentencing and signed into law by President Donald Trump in 2018, is just what its name implies, said Gertner.

“It reduces sentences to the merely inhumane rather than the grotesque. We still throw people in jail more than anybody else. We still resort to imprisonment, rather than thinking of other alternatives. We still resort to punishment rather than other models. None of that has really changed. I don’t deny the significance of somebody getting out of prison a year or two early, but no one should think that that’s reform.”

Not just bad apples

Reform has long been a goal for federal leaders. Many heralded Obama-era changes aimed at eliminating racial disparities in policing and outlined in the report by The President’s Task Force on 21st Century policing. But HKS’s Smith saw them as largely symbolic. “It’s a nod to reform. But most of the reforms that are implemented in this country tend to be reforms that nibble around the edges and don’t really make much of a difference.”

Efforts such as diversifying police forces and implicit bias training do little to change behaviors and reduce violent conduct against people of color, said Smith, who cites studies suggesting a majority of Americans hold negative biases against Black and brown people, and that unconscious prejudices and stereotypes are difficult to erase.

“Experiments show that you can, in the context of a day, get people to think about race differently, and maybe even behave differently. But if you follow up, say, a week, or two weeks later, those effects are gone. We don’t know how to produce effects that are long-lasting. We invest huge amounts to implement such police reforms, but most often there’s no empirical evidence to support their efficacy.”

Even the early studies around the effectiveness of body cameras suggest the devices do little to change “officers’ patterns of behavior,” said Smith, though she cautions that researchers are still in the early stages of collecting and analyzing the data.

And though police body cameras have caught officers in unjust violence, much of the general public views the problem as anomalous.

“Despite what many people in low-income communities of color think about police officers, the broader society has a lot of respect for police and thinks if you just get rid of the bad apples, everything will be fine,” Smith added. “The problem, of course, is this is not just an issue of bad apples.”

Efforts such as diversifying police forces and implicit bias training do little to change behaviors and reduce violent conduct against people of color, said Sandra Susan Smith, a professor of criminal justice Harvard Kennedy School.

Community-based ways forward

Still Smith sees reason for hope and possible ways forward involving a range of community-based approaches. As part of the effort to explore meaningful change, Smith, along with Christopher Winship , Diker-Tishman Professor of Sociology at Harvard University and a member of the senior faculty at HKS, have organized “ Reimagining Community Safety: A Program in Criminal Justice Speaker Series ” to better understand the perspectives of practitioners, policymakers, community leaders, activists, and academics engaged in public safety reform.

Some community-based safety models have yielded important results. Smith singles out the Crisis Assistance Helping Out on the Streets program (known as CAHOOTS ) in Eugene, Ore., which supplements police with a community-based public safety program. When callers dial 911 they are often diverted to teams of workers trained in crisis resolution, mental health, and emergency medicine, who are better equipped to handle non-life-threatening situations. The numbers support her case. In 2017 the program received 25,000 calls, only 250 of which required police assistance. Training similar teams of specialists who don’t carry weapons to handle all traffic stops could go a long way toward ending violent police encounters, she said.

“Imagine you have those kinds of services in play,” said Smith, paired with community-based anti-violence program such as Cure Violence , which aims to stop violence in targeted neighborhoods by using approaches health experts take to control disease, such as identifying and treating individuals and changing social norms. Together, she said, these programs “could make a huge difference.”

At Harvard Law School, students have been studying how an alternate 911-response team might function in Boston. “We were trying to move from thinking about a 911-response system as an opportunity to intervene in an acute moment, to thinking about what it would look like to have a system that is trying to help reweave some of the threads of community, a system that is more focused on healing than just on stopping harm” said HLS Professor Rachel Viscomi, who directs the Harvard Negotiation and Mediation Clinical Program and oversaw the research.

The forthcoming report, compiled by two students in the HLS clinic, Billy Roberts and Anna Vande Velde, will offer officials a range of ideas for how to think about community safety that builds on existing efforts in Boston and other cities, said Viscomi.

But Smith, like others, knows community-based interventions are only part of the solution. She applauds the Justice Department’s investigation into the Ferguson Police Department after the shooting of Brown. The 102-page report shed light on the department’s discriminatory policing practices, including the ways police disproportionately targeted Black residents for tickets and fines to help balance the city’s budget. To fix such entrenched problems, state governments need to rethink their spending priorities and tax systems so they can provide cities and towns the financial support they need to remain debt-free, said Smith.

Rethinking the 911-response system to being one that is “more focused on healing than just on stopping harm” is part of the student-led research under the direction of Law School Professor Rachel Viscomi, who heads up the Harvard Negotiation and Mediation Clinical Program.

Jon Chase/Harvard file photo

“Part of the solution has to be a discussion about how government is funded and how a city like Ferguson got to a place where government had so few resources that they resorted to extortion of their residents, in particular residents of color, in order to make ends meet,” she said. “We’ve learned since that Ferguson is hardly the only municipality that has struggled with funding issues and sought to address them through the oppression and repression of their politically, socially, and economically marginalized Black and Latino residents.”

Police contracts, she said, also need to be reexamined. The daughter of a “union man,” Smith said she firmly supports officers’ rights to union representation to secure fair wages, health care, and safe working conditions. But the power unions hold to structure police contracts in ways that protect officers from being disciplined for “illegal and unethical behavior” needs to be challenged, she said.

“I think it’s incredibly important for individuals to be held accountable and for those institutions in which they are embedded to hold them to account. But we routinely find that union contracts buffer individual officers from having to be accountable. We see this at the level of the Supreme Court as well, whose rulings around qualified immunity have protected law enforcement from civil suits. That needs to change.”

Other Harvard experts agree. In an opinion piece in The Boston Globe last June, Tomiko Brown-Nagin , dean of the Harvard Radcliffe Institute and the Daniel P.S. Paul Professor of Constitutional Law at HLS, pointed out the Court’s “expansive interpretation of qualified immunity” and called for reform that would “promote accountability.”

“This nation is devoted to freedom, to combating racial discrimination, and to making government accountable to the people,” wrote Brown-Nagin. “Legislators today, like those who passed landmark Civil Rights legislation more than 50 years ago, must take a stand for equal justice under law. Shielding police misconduct offends our fundamental values and cannot be tolerated.”

Share this article

You might like.

Michael Mann points to prehistoric catastrophes, modern environmental victories

Educators, activists explore peacebuilding based on shared desires for ‘freedom and equality and independence’ at Weatherhead panel

Former Palestinian Authority prime minister says strengthening execution of 1993 accords could lead to two-state solution

College accepts 1,937 to Class of 2028

Students represent 94 countries, all 50 states

Pushing back on DEI ‘orthodoxy’

Panelists support diversity efforts but worry that current model is too narrow, denying institutions the benefit of other voices, ideas

So what exactly makes Taylor Swift so great?

Experts weigh in on pop superstar's cultural and financial impact as her tours and albums continue to break records.

Read our research on: Abortion | International Conflict | Election 2024

Regions & Countries

10 things we know about race and policing in the u.s..

Days of protests across the United States in the wake of George Floyd’s death in the custody of Minneapolis police have brought new attention to questions about police officers’ attitudes toward black Americans, protesters and others. The public’s views of the police, in turn, are also in the spotlight. Here’s a roundup of Pew Research Center survey findings from the past few years about the intersection of race and law enforcement.

Most of the findings in this post were drawn from two previous Pew Research Center reports: one on police officers and policing issues published in January 2017, and one on the state of race relations in the United States published in April 2019. We also drew from a September 2016 report on how black and white Americans view police in their communities. (The questions asked for these reports, as well as their responses, can be found in the reports’ accompanying “topline” file or files.)

The 2017 police report was based on two surveys. One was of 7,917 law enforcement officers from 54 police and sheriff’s departments across the U.S., designed and weighted to represent the population of officers who work in agencies that employ at least 100 full-time sworn law enforcement officers with general arrest powers, and conducted between May and August 2016. The other survey, of the general public, was conducted via the Center’s American Trends Panel (ATP) in August and September 2016 among 4,538 respondents. (The 2016 report on how blacks and whites view police in their communities also was based on that survey.) More information on methodology is available here .

The 2019 race report was based on a survey conducted in January and February 2019. A total of 6,637 people responded, out of 9,402 who were sampled, for a response rate of 71%. The respondents included 5,599 from the ATP and oversamples of 530 non-Hispanic black and 508 Hispanic respondents sampled from Ipsos’ KnowledgePanel. More information on methodology is available here .

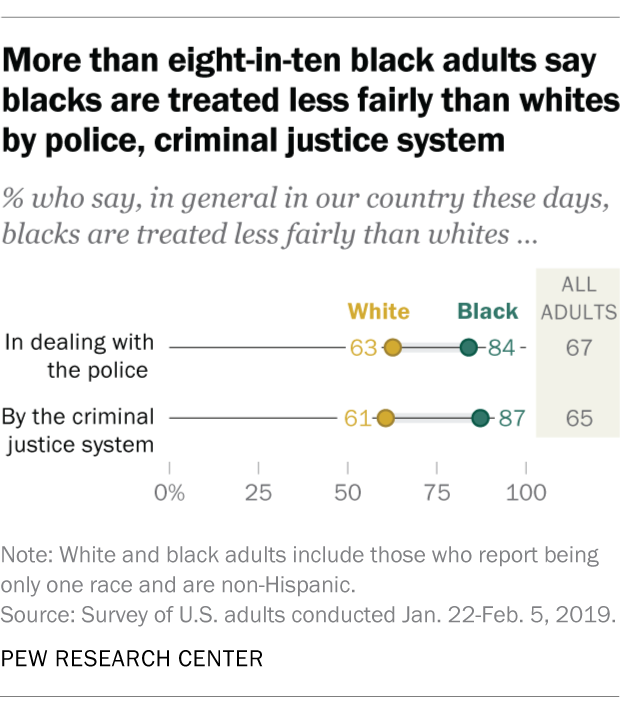

1 Majorities of both black and white Americans say black people are treated less fairly than whites in dealing with the police and by the criminal justice system as a whole. In a 2019 Center survey , 84% of black adults said that, in dealing with police, blacks are generally treated less fairly than whites; 63% of whites said the same. Similarly, 87% of blacks and 61% of whites said the U.S. criminal justice system treats black people less fairly.

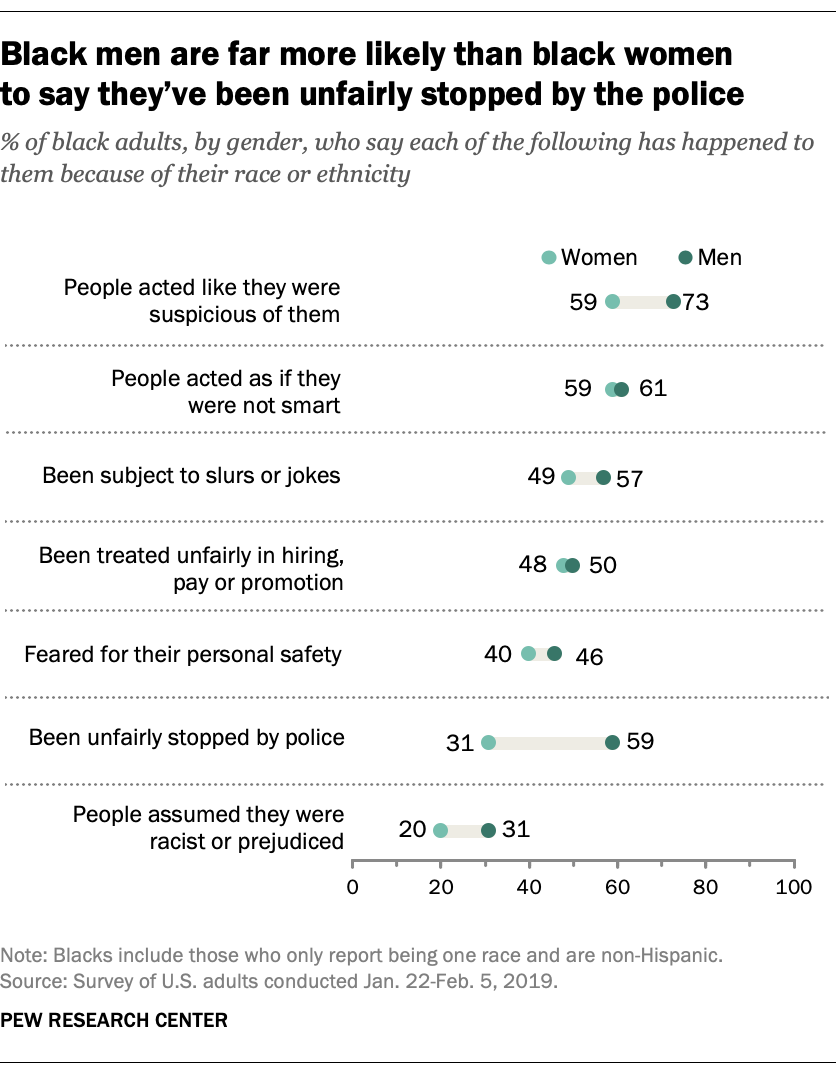

2 Black adults are about five times as likely as whites to say they’ve been unfairly stopped by police because of their race or ethnicity (44% vs. 9%), according to the same survey. Black men are especially likely to say this : 59% say they’ve been unfairly stopped, versus 31% of black women.

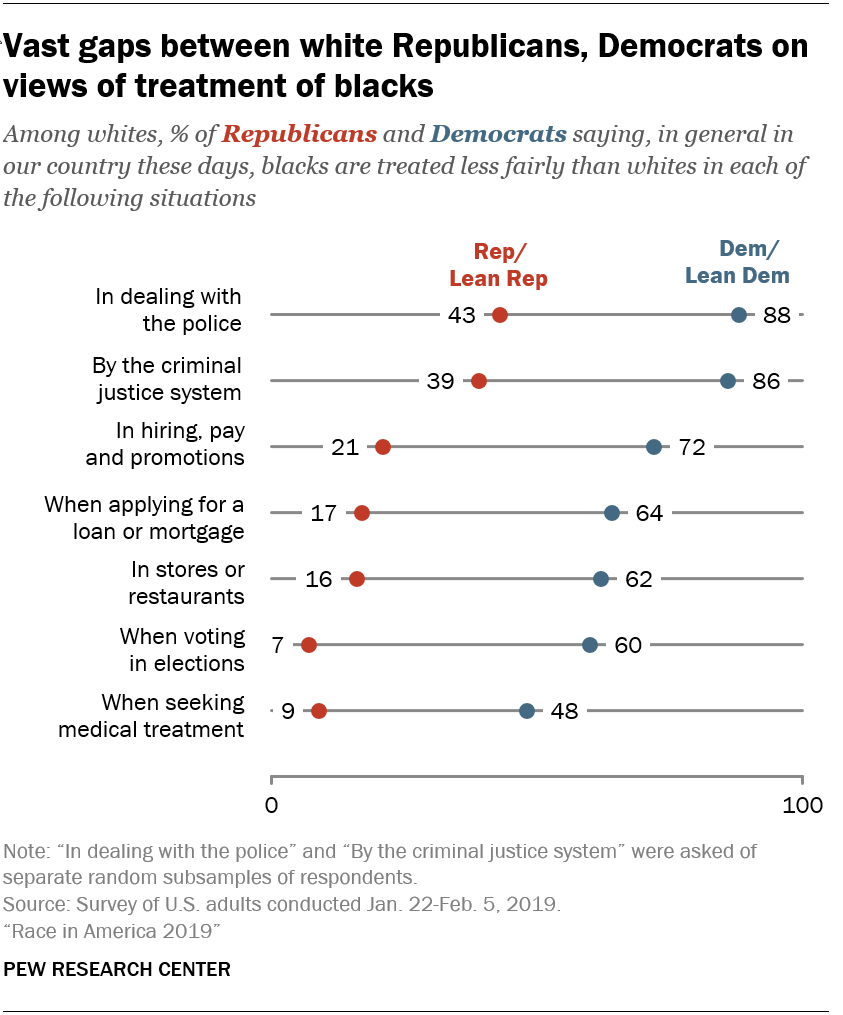

3 White Democrats and white Republicans have vastly different views of how black people are treated by police and the wider justice system. Overwhelming majorities of white Democrats say black people are treated less fairly than whites by the police (88%) and the criminal justice system (86%), according to the 2019 poll. About four-in-ten white Republicans agree (43% and 39%, respectively).

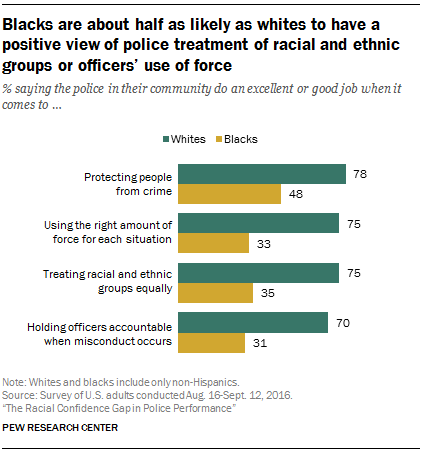

5 Black Americans are far less likely than whites to give police high marks for the way they do their jobs . In a 2016 survey, only about a third of black adults said that police in their community did an “excellent” or “good” job in using the right amount of force (33%, compared with 75% of whites), treating racial and ethnic groups equally (35% vs. 75%), and holding officers accountable for misconduct (31% vs. 70%).

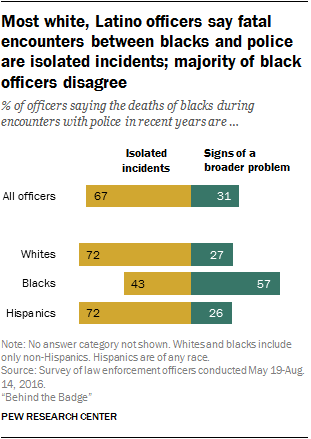

6 In the past, police officers and the general public have tended to view fatal encounters between black people and police very differently. In a 2016 survey of nearly 8,000 policemen and women from departments with at least 100 officers, two-thirds said most such encounters are isolated incidents and not signs of broader problems between police and the black community. In a companion survey of more than 4,500 U.S. adults, 60% of the public called such incidents signs of broader problems between police and black people. But the views given by police themselves were sharply differentiated by race: A majority of black officers (57%) said that such incidents were evidence of a broader problem, but only 27% of white officers and 26% of Hispanic officers said so.

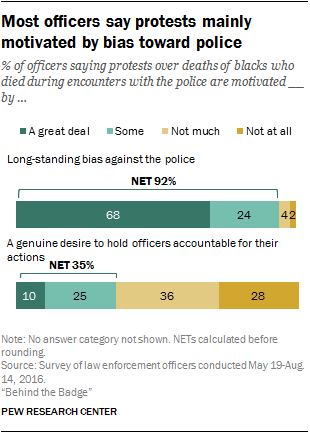

7 Around two-thirds of police officers (68%) said in 2016 that the demonstrations over the deaths of black people during encounters with law enforcement were motivated to a great extent by anti-police bias; only 10% said (in a separate question) that protesters were primarily motivated by a genuine desire to hold police accountable for their actions. Here as elsewhere, police officers’ views differed by race: Only about a quarter of white officers (27%) but around six-in-ten of their black colleagues (57%) said such protests were motivated at least to some extent by a genuine desire to hold police accountable.

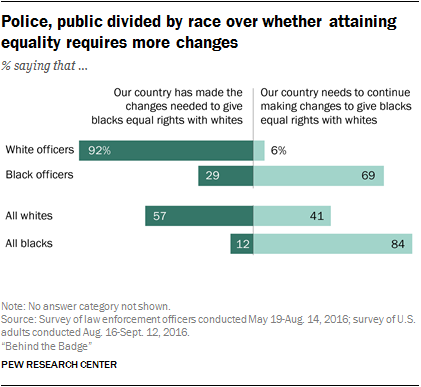

8 White police officers and their black colleagues have starkly different views on fundamental questions regarding the situation of blacks in American society, the 2016 survey found. For example, nearly all white officers (92%) – but only 29% of their black colleagues – said the U.S. had made the changes needed to assure equal rights for blacks.

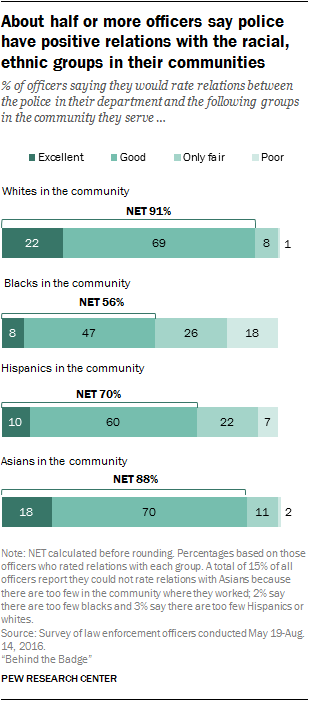

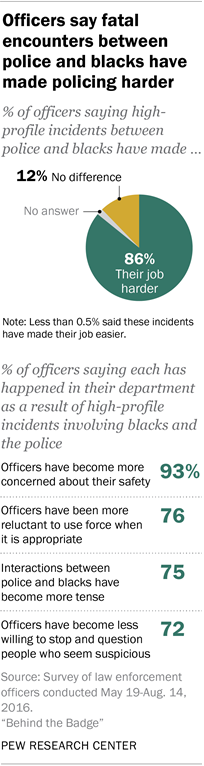

9 A majority of officers said in 2016 that relations between the police in their department and black people in the community they serve were “excellent” (8%) or “good” (47%). However, far higher shares saw excellent or good community relations with whites (91%), Asians (88%) and Hispanics (70%). About a quarter of police officers (26%) said relations between police and black people in their community were “only fair,” while nearly one-in-five (18%) said they were “poor” – with black officers far more likely than others to say so. (These percentages are based on only those officers who offered a rating.)

10 An overwhelming majority of police officers (86%) said in 2016 that high-profile fatal encounters between black people and police officers had made their jobs harder . Sizable majorities also said such incidents had made their colleagues more worried about safety (93%), heightened tensions between police and blacks (75%), and left many officers reluctant to use force when appropriate (76%) or to question people who seemed suspicious (72%).

Sign up for our weekly newsletter

Fresh data delivered Saturday mornings

America’s public school teachers are far less racially and ethnically diverse than their students

One-third of asian americans fear threats, physical attacks and most say violence against them is rising, majorities of americans see at least some discrimination against black, hispanic and asian people in the u.s., amid national reckoning, americans divided on whether increased focus on race will lead to major policy change, support for black lives matter has decreased since june but remains strong among black americans, most popular.

About Pew Research Center Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping the world. It conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, media content analysis and other empirical social science research. Pew Research Center does not take policy positions. It is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts .

Filed under:

What the police really believe

Inside the distinctive, largely unknown ideology of American policing — and how it justifies racist violence.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/67025127/GettyImages_1224020513.0.jpg)

Share this story

- Share this on Facebook

- Share this on Twitter

- Share this on Reddit

- Share All sharing options

Share All sharing options for: What the police really believe

Arthur Rizer is a former police officer and 21-year veteran of the US Army, where he served as a military policeman. Today, he heads the criminal justice program at the R Street Institute, a center-right think tank in DC. And he wants you to know that American policing is even more broken than you think.

“That whole thing about the bad apple? I hate when people say that,” Rizer tells me. “The bad apple rots the barrel. And until we do something about the rotten barrel, it doesn’t matter how many good fucking apples you put in.”

To illustrate the problem, Rizer tells a story about a time he observed a patrol by some officers in Montgomery, Alabama. They were called in to deal with a woman they knew had mental illness; she was flailing around and had cut someone with a broken plant pick. To subdue her, one of the officers body-slammed her against a door. Hard.

Rizer recalls that Montgomery officers were nervous about being watched during such a violent arrest — until they found out he had once been a cop. They didn’t actually have any problem with what one of them had just done to the woman; in fact, they started laughing about it.

“It’s one thing to use force and violence to affect an arrest. It’s another thing to find it funny,” he tells me. “It’s just pervasive throughout policing. When I was a police officer and doing these kind of ride-alongs [as a researcher], you see the underbelly of it. And it’s ... gross.”

America’s epidemic of police violence is not limited to what’s on the news. For every high-profile story of a police officer killing an unarmed Black person or tear-gassing peaceful protesters, there are many, many allegations of police misconduct you don’t hear about — abuses ranging from excessive use of force to mistreatment of prisoners to planting evidence. African Americans are arrested and roughed up by cops at wildly disproportionate rates , relative to both their overall share of the population and the percentage of crimes they commit.

Something about the way police relate to the communities they’re tasked with protecting has gone wrong. Officers aren’t just regularly treating people badly; a deep dive into the motivations and beliefs of police reveals that too many believe they are justified in doing so.

To understand how the police think about themselves and their job, I interviewed more than a dozen former officers and experts on policing. These sources, ranging from conservatives to police abolitionists, painted a deeply disturbing picture of the internal culture of policing.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/20064750/GettyImages_1223804672.jpg)

Police officers across America have adopted a set of beliefs about their work and its role in our society. The tenets of police ideology are not codified or written down, but are nonetheless widely shared in departments around the country.

The ideology holds that the world is a profoundly dangerous place: Officers are conditioned to see themselves as constantly in danger and that the only way to guarantee survival is to dominate the citizens they’re supposed to protect. The police believe they’re alone in this fight; police ideology holds that officers are under siege by criminals and are not understood or respected by the broader citizenry. These beliefs, combined with widely held racial stereotypes, push officers toward violent and racist behavior during intense and stressful street interactions.

In that sense, police ideology can help us understand the persistence of officer-involved shootings and the recent brutal suppression of peaceful protests. In a culture where Black people are stereotyped as more threatening, Black communities are terrorized by aggressive policing, with officers acting less like community protectors and more like an occupying army.

The beliefs that define police ideology are neither universally shared among officers nor evenly distributed across departments. There are more than 600,000 local police officers across the country and more than 12,000 local police agencies. The officer corps has gotten more diverse over the years, with women, people of color, and LGBTQ officers making up a growing share of the profession. Speaking about such a group in blanket terms would do a disservice to the many officers who try to serve with care and kindness.

However, the officer corps remains overwhelmingly white, male, and straight. Federal Election Commission data from the 2020 cycle suggests that police heavily favor Republicans . And it is indisputable that there are commonly held beliefs among officers.

“The fact that not every department is the same doesn’t undermine the point that there are common factors that people can reasonably identify as a police culture,” says Tracey Meares, the founding director of Yale University’s Justice Collaboratory.

The danger imperative

In 1998, Georgia sheriff’s deputy Kyle Dinkheller pulled over a middle-aged white man named Andrew Howard Brannan for speeding. Brannan, a Vietnam veteran with PTSD, refused to comply with Dinkheller’s instructions. He got out of the car and started dancing in the middle of the road, singing “Here I am, shoot me” over and over again.

In the encounter, recorded by the deputy’s dashcam, things then escalate: Brannan charges at Dinkheller; Dinkheller tells him to “get back.” Brannan heads back to the car — only to reemerge with a rifle pointed at Dinkheller. The officer fires first, and misses; Brannan shoots back. In the ensuing firefight, both men are wounded, but Dinkheller far more severely. It ends with Brannan standing over Dinkheller, pointing the rifle at the deputy’s eye. He yells — “Die, fucker!” — and pulls the trigger.

The dashcam footage of Dinkheller’s killing, widely known among cops as the “Dinkheller video,” is burned into the minds of many American police officers. It is screened in police academies around the country ; one training turns it into a video game-style simulation in which officers can change the ending by killing Brannan. Jeronimo Yanez, the officer who killed Philando Castile during a 2016 traffic stop, was shown the Dinkheller video during his training.

“Every cop knows the name ‘Dinkheller’ — and no one else does,” says Peter Moskos, a former Baltimore police officer who currently teaches at the John Jay College of Criminal Justice.

The purpose of the Dinkheller video, and many others like it shown at police academies, is to teach officers that any situation could escalate to violence. Cop killers lurk around every corner.

It’s true that policing is a relatively dangerous job . But contrary to the impression the Dinkheller video might give trainees, murders of police are not the omnipresent threat they are made out to be. The number of police killings across the country has been falling for decades ; there’s been a 90 percent drop in ambush killings of officers since 1970. According to Bureau of Labor Statistics data , about 13 per 100,000 police officers died on the job in 2017. Compare that to farmers (24 deaths per 100,000), truck drivers (26.9 per 100,000), and trash collectors (34.9 per 100,000). But police academies and field training officers hammer home the risk of violent death to officers again and again.

It’s not just training and socialization, though: The very nature of the job reinforces the sense of fear and threat. Law enforcement isn’t called to people’s homes and streets when things are going well. Officers constantly find themselves thrown into situations where a seemingly normal interaction has gone haywire — a marital argument devolving into domestic violence, for example.

“For them, any scene can turn into a potential danger,” says Eugene Paoline III, a criminologist at the University of Central Florida. “They’re taught, through their experiences, that very routine events can go bad.”

Michael Sierra-Arévalo, a professor at UT-Austin, calls the police obsession with violent death “ the danger imperative .” After conducting 1,000 hours of fieldwork and interviews with 94 police officers, he found that the risk of violent death occupies an extraordinary amount of mental space for many officers — far more so than it should, given the objective risks.

Here’s what I mean: According to the past 20 years of FBI data on officer fatalities, 1,001 officers have been killed by firearms while 760 have died in car crashes. For this reason, police officers are, like the rest of us, required to wear seat belts at all times.

In reality, many choose not to wear them even when speeding through city streets. Sierra-Arévalo rode along with one police officer, whom he calls officer Doyle, during a car chase where Doyle was going around 100 miles per hour — and still not wearing a seat belt. Sierra-Arévalo asked him why he did things like this. Here’s what Doyle said:

There’s times where I’ll be driving and the next thing you know I’ll be like, ‘Oh shit, that dude’s got a fucking gun!’ I’ll stop [mimics tires screeching], try to get out — fuck. Stuck on the seat belt … I’d rather just be able to jump out on people, you know. If I have to, be able to jump out of this deathtrap of a car.

Despite the fact that fatal car accidents are a risk for police, officers like Doyle prioritize their ability to respond to one specific shooting scenario over the clear and consistent benefits of wearing a seat belt.

“Knowing officers consistently claim safety is their primary concern, multiple drivers not wearing a seatbelt and speeding towards the same call should be interpreted as an unacceptable danger; it is not,” Sierra-Arévalo writes. “The danger imperative — the preoccupation with violence and the provision of officer safety — contributes to officer behaviors that, though perceived as keeping them safe, in fact put them in great physical danger.”

This outsized attention to violence doesn’t just make officers a threat to themselves. It’s also part of what makes them a threat to citizens.

Because officers are hyper-attuned to the risks of attacks, they tend to believe that they must always be prepared to use force against them — sometimes even disproportionate force. Many officers believe that, if they are humiliated or undermined by a civilian, that civilian might be more willing to physically threaten them.

Scholars of policing call this concept “ maintaining the edge ,” and it’s a vital reason why officers seem so willing to employ force that appears obviously excessive when captured by body cams and cellphones.

“To let down that edge is perceived as inviting chaos, and thus danger,” Moskos says.

This mindset helps explain why so many instances of police violence — like George Floyd’s killing by officer Derek Chauvin in Minneapolis — happen during struggles related to arrest .

In these situations, the officers aren’t always threatened with a deadly weapon: Floyd, for example, was unarmed. But when the officer decides the suspect is disrespecting them or resisting their commands, they feel the need to use force to reestablish the edge.

They need to make the suspect submit to their authority.

A siege mentality

Police officers today tend to see themselves as engaged in a lonely, armed struggle against the criminal element. They are judged by their effectiveness at that task, measured by internal data such as arrest numbers and crime rates in the areas they patrol. Officers believe these efforts are underappreciated by the general public; according to a 2017 Pew report , 86 percent of police believe the public doesn’t really understand the “risks and challenges” involved in their job.

Rizer, the former officer and R Street researcher, recently conducted a separate large-scale survey of American police officers. One of the questions he asked was whether they would want their children to become police officers. A majority, around 60 percent, said no — for reasons that, in Rizer’s words, “blew me away.”

“The vast majority of people that said ‘no, I don’t want them to become a police officer’ was because they felt like the public no longer supported them — and that they were ‘at war’ with the public,” he tells me. “There’s a ‘me versus them’ kind of worldview, that we’re not part of this community that we’re patrolling.”

You can see this mentality on display in the widespread police adoption of an emblem called the “thin blue line.” In one version of the symbol , two black rectangles are separated by a dark blue horizontal line. The rectangles represent the public and criminals, respectively; the blue line separating them is the police.

In another, the blue line replaces the central white stripe in a black-and-white American flag, separating the stars from the stripes below. During the recent anti-police violence protests in Cincinnati, Ohio, officers raised this modified banner outside their station.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/20064827/GettyImages_1223286806.jpg)

In the “thin blue line” mindset, loyalty to the badge is paramount; reporting excessive force or the use of racial slurs by a colleague is an act of treason. This emphasis on loyalty can create conditions for abuses, even systematic ones, to take place: Officers at one station in Chicago, Illinois, tortured at least 125 Black suspects between 1972 and 1991. These crimes were uncovered by the dogged work of an investigative journalist rather than a police whistleblower.

“Officers, when they get wind that something might be wrong, either participate in it themselves when they’re commanded to — or they actively ignore it, find ways to look the other way,” says Laurence Ralph, a Princeton professor and the author of The Torture Letters , a recent book on the abuses in Chicago.

This insularity and siege mentality is not universal among American police. Worldviews vary from person to person and department to department; many officers are decent people who work hard to get to know citizens and address their concerns.

But it is powerful enough, experts say, to distort departments across the country. It has seriously undermined some recent efforts to reorient the police toward working more closely with local communities, generally pushing departments away from deep engagement with citizens and toward a more militarized and aggressive model.

“The police have been in the midst of an epic ideological battle. It’s been taking place ever since the supposed community policing revolution started back in the 1980s,” says Peter Kraska, a professor at Eastern Kentucky University’s School of Justice Studies. “In the last 10 to 15 years, the more toxic elements have been far more influential.”

Since the George Floyd protests began, police have tear-gassed protesters in 100 different US cities . This is not an accident or the result of behaviors by a few bad apples. Instead, it reflects the fact that officers see themselves as at war — and the protesters as the enemies.

A 2017 study by Heidi Reynolds-Stenson, a sociologist at Colorado State University-Pueblo, examined data on 7,000 protests from 1960 to 1995. She found that “police are much more likely to try to quell protests that criticize police conduct.”

“Recent scholarship argues that, over the last twenty years, protest policing [has gotten] more aggressive and less impartial,” Reynolds-Stenson concludes. “The pattern of disproportionate repression of police brutality protests found in this study may be even more pronounced today.”

There’s a reason that, after New York Police Department Lt. Robert Cattani kneeled alongside Black Lives Matter protesters on May 31, he sent an email to his precinct apologizing for the “horrible decision to give into a crowd of protesters’ demands.” In his mind, the decision to work with the crowd amounted to collaboration with the enemy.

“The cop in me,” Cattani wrote, “wants to kick my own ass.”

Anti-Blackness

Policing in the United States has always been bound up with the color line. In the South, police departments emerged out of 18th century slave patrols — bands of men working to discipline slaves, facilitate their transfer between plantations, and catch runaways. In the North, professional police departments came about as a response to a series of mid-19th century urban upheavals — many of which, like the 1834 New York anti-abolition riot , had their origins in racial strife.

While policing has changed dramatically since then, there’s clear evidence of continued structural racism in American policing. The Washington Post’s Radley Balko has compiled an extensive list of academic studies documenting this fact , covering everything from traffic stops to use of deadly force. Research has confirmed that this is a nationwide problem , involving a significant percentage of officers .

When talking about race in policing and the way it relates to police ideology, there are two related phenomena to think about.

The first is overt racism. In some police departments, the culture permits a minority of racists on the force to commit brutal acts of racial violence with impunity.

Examples of explicit racism abound in police officer conduct. The following three incidents were reported in the past month alone:

- In leaked audio , Wilmington, North Carolina, officer Kevin Piner said, “we are just going to go out and start slaughtering [Blacks],” adding that he “can’t wait” for a new civil war so whites could “wipe them off the fucking map.” Piner was dismissed from the force, as were two other officers involved in the conversation.

- Joey Lawn, a 10-year veteran of the Meridian, Mississippi, force, was fired for using an unspecified racial slur against a Black colleague during a 2018 exercise. Lawn’s boss, John Griffith, was demoted from captain to lieutenant for failing to punish Lawn at the time.

- Four officers in San Jose, California, were put on administrative leave amid an investigation into their membership in a secret Facebook group. In a public post, officer Mark Pimentel wrote that “black lives don’t really matter”; in another private one, retired officer Michael Nagel wrote about female Muslim prisoners: “i say we repurpose the hijabs into nooses.”

In all of these cases, superiors punished officers for their offensive comments and actions — but only after they came to light. It’s safe to say a lot more go unreported.

Last April , a human resources manager in San Francisco’s city government quit after spending two years conducting anti-bias training for the city’s police force. In an exit email sent to his boss and the city’s police chief, he wrote that “the degree of anti-black sentiment throughout SFPD is extreme,” adding that “while there are some at SFPD who possess somewhat of a balanced view of racism and anti-blackness, there are an equal number (if not more) — who possess and exude deeply rooted anti-black sentiments.”

Psychological research suggests that white officers are disproportionately likely to demonstrate a personality trait called “social dominance orientation.” Individuals with high levels of this trait tend to believe that existing social hierarchies are not only necessary, but morally justified — that inequalities reflect the way that things actually should be. The concept was originally formulated in the 1990s as a way of explaining why some people are more likely to accept what a group of researchers termed “ideologies that promote or maintain group inequality,” including “the ideology of anti-Black racism.”

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/20064923/GettyImages_1217563708.jpg)

This helps us understand why some officers are more likely to use force against Black suspects, even unarmed ones. Phillip Atiba Goff, a psychologist at John Jay and the CEO of the Center for Policing Equity think tank, has done forthcoming research on the distribution of social dominance orientation among officers in three different cities. Goff and his co-authors found that white officers who score very highly in this trait tend to use force more frequently than those who don’t.

“If you think the social hierarchy is good, then maybe you’re more willing to use violence from the state’s perspective to enforce that hierarchy — and you think that’s your job,” he tells me.

But while the problem of overt racism and explicit commitment to racial hierarchy is a serious one, it’s not necessarily the central problem in modern policing.

The second manifestation of anti-Blackness is more subtle. The very nature of policing, in which officers perform a dizzying array of stressful tasks for long hours, brings out the worst in people. The psychological stressors combine with police ideology and widespread cultural stereotypes to push officers, even ones who don’t hold overtly racist beliefs, to treat Black people as more suspect and more dangerous. It’s not just the officers who are the problem; it’s the society they come from, and the things that society asks them to do.

While overt racists may be overrepresented on police forces, the average white officer’s beliefs are not all that different from those of the average white person in their local community. According to Goff, tests of racial bias reveal somewhat higher rates of prejudice among officers than the general population, but the effect size tends to be swamped by demographic and regional effects.

“If you live in a racist city, that’s going to matter more for how racist your law enforcement is ... than looking at the difference between law enforcement and your neighbors,” he told me.

In this sense, the rising diversity of America’s officer corps should make a real difference. If you draw from a demographically different pool of recruits, one with overall lower levels of racial bias, then there should be less of a problem with racism on the force.

There’s some data to back this up. Pew’s 2017 survey of officers found that Black officers and female officers were considerably more sympathetic to anti-police brutality protesters than white ones. A 2016 paper on officer-involved killings of Black people, from Yale’s Joscha Legewie and Columbia’s Jeffrey Fagan, found that departments with a larger percentage of Black officers had lower rates of killings of Black people.

But scholars caution that diversity will not, on its own, solve policing’s problems. In Pew’s survey, 60 percent of Hispanic and white officers said their departments had “excellent” or “good” relations with the local Black community, while only 32 percent of Black officers said the same. The hierarchy of policing remains extremely white — across cities, departmental brass and police unions tend to be disproportionately white relative to the rank-and-file. And the existing culture in many departments pushes nonwhite officers to try and fit in with what’s been established by the white hierarchy.

“We have seen that officers of color actually face increased pressure to fit into the existing culture of policing and may go out of their way to align themselves with traditional police tactics,” says Shannon Portillo, a scholar of bureaucratic culture at the University of Kansas-Edwards.

There’s a deeper problem than mere representation. The very nature of policing, both police ideology and the nuts-and-bolts nature of the job, can bring out the worst in people — especially when it comes to deep-seated racial prejudices and stereotypes.

The intersection of commonly held stereotypes with police ideology can prime officers for abusive behavior, especially when they’re patrolling majority-Black neighborhoods where residents have long-standing grievances against the cops. Some kind of incident with a Black citizen is certain to set off a confrontation; officers will eventually feel the need to escalate well beyond what seems necessary or even acceptable from the outside to protect themselves.

“The drug dealer — if he says ‘fuck you’ one day, it’s like getting punked on the playground. You have to go through that every day,” says Moskos, the former Baltimore officer. “You’re not allowed to get punked as a cop, not just because of your ego but because of the danger of it.”

The problems with ideology and prejudice are dramatically intensified by the demanding nature of the policing profession. Officers work a difficult job for long hours, called upon to handle responsibilities ranging from mental health intervention to spousal dispute resolution. While on shift, they are constantly anxious, searching for the next threat or potential arrest.

Stress gets to them even off the job; PTSD and marital strife are common problems. It’s a kind of negative feedback loop: The job makes them stressed and nervous, which damages their mental health and personal relationships, which raises their overall level of stress and makes the job even more taxing.

According to Goff, it’s hard to overstate how much more likely people are to be racist under these circumstances. When you put people under stress, they tend to make snap judgments rooted in their basic instincts. For police officers, raised in a racist society and socialized in a violent work atmosphere, that makes racist behavior inevitable.