Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Graduate School Applications: Writing a Research Statement

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

What is a Research Statement?

A research statement is a short document that provides a brief history of your past research experience, the current state of your research, and the future work you intend to complete.

The research statement is a common component of a potential candidate’s application for post-undergraduate study. This may include applications for graduate programs, post-doctoral fellowships, or faculty positions. The research statement is often the primary way that a committee determines if a candidate’s interests and past experience make them a good fit for their program/institution.

What Should It Look Like?

Research statements are generally one to two single-spaced pages. You should be sure to thoroughly read and follow the length and content requirements for each individual application.

Your research statement should situate your work within the larger context of your field and show how your works contributes to, complicates, or counters other work being done. It should be written for an audience of other professionals in your field.

What Should It Include?

Your statement should start by articulating the broader field that you are working within and the larger question or questions that you are interested in answering. It should then move to articulate your specific interest.

The body of your statement should include a brief history of your past research . What questions did you initially set out to answer in your research project? What did you find? How did it contribute to your field? (i.e. did it lead to academic publications, conferences, or collaborations?). How did your past research propel you forward?

It should also address your present research . What questions are you actively trying to solve? What have you found so far? How are you connecting your research to the larger academic conversation? (i.e. do you have any publications under review, upcoming conferences, or other professional engagements?) What are the larger implications of your work?

Finally, it should describe the future trajectory on which you intend to take your research. What further questions do you want to solve? How do you intend to find answers to these questions? How can the institution to which you are applying help you in that process? What are the broader implications of your potential results?

Note: Make sure that the research project that you propose can be completed at the institution to which you are applying.

Other Considerations:

- What is the primary question that you have tried to address over the course of your academic career? Why is this question important to the field? How has each stage of your work related to that question?

- Include a few specific examples that show your success. What tangible solutions have you found to the question that you were trying to answer? How have your solutions impacted the larger field? Examples can include references to published findings, conference presentations, or other professional involvement.

- Be confident about your skills and abilities. The research statement is your opportunity to sell yourself to an institution. Show that you are self-motivated and passionate about your project.

- Skip to primary navigation

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

The Professor Is In

Guidance for all things PhD: Graduate School, Job Market and Careers

Dr. Karen’s Rules of the Research Statement

By Karen Kelsky | September 16, 2016

We’ve looked at the Cover Letter and the CV and the Teaching Statement . Today we look at the Research Statement.

An expanded and updated version of this post can now be found in chapter 27 of my book, the professor is in: the essential guide to turning your ph.d. into a job ..

Today, at long last, and in response to popular demand, a post on the Research Statement.

I have, perhaps, procrastinated on blogging about the Research Statement because at some level I felt that the rules might be more variable on this document, particularly with regard to length.

But in truth, they really aren’t.

The RS should be be two pages long for any junior candidate in the humanities or soft social sciences. Two pages allows for an elaboration of the research well beyond the summary in the cover letter that gives the search committee substantial information to work with. Those junior candidates in the hard sciences and fields like Psychology can have 3-4 page research statements.

I strongly urge all job-seekers to investigate the norms of their individual fields carefully, and follow the advice they receive on this matter from experts in their own fields. Just never simply ASSUME that longer is better in an RS or in any job document.

By the way, the RS to which I refer here is the document sometimes requested as part of a basic job application. This is NOT the “research proposal” required by specific fellowship or postdoc applications! Those will specify a length, and should be written to follow the outline I describe in Dr. Karen’s Foolproof Grant Template .) They are a totally different genre of document; don’t confuse the two!

Anyway, back to the RS: there are undoubtedly a number of excellent reasons that people could give for writing a longer RS, based on thoroughness or detail or concerns for accuracy. And I would acknowledge those principles as valid ones.

But they would all come second to the single most important principle of all job market writing, in my view, which is the principle of search committee exhaustion.

Search committee members are exhausted, and they are overwhelmed and distracted. There simply is no bandwidth in their brains or their psyches to handle the amount of material they are required to read, when searches routinely garner between 300 and 1000 applications.

Anything that feels “long” is going to be resented just by virtue of its length. And resentment is categorically what you don’t want a search committee member feeling about your job application materials.

So, in short, the Research Statement, just like the Teaching Statement , needs to be one to two pages in length, single spaced. And like the TS, it needs to be in 11 or 12 point font, and have decent one-inch margins.

What are the other rules? Here they are:

- Print the RS on regular printer paper. Do not use letterhead for this or the TS, and do not use any special high grade paper.

- Put your name and the words “Research Statement” centered at the top.

- If unsure how to structure, use a 5-paragraph model as follows:

[… edited… ]

Here are some additional principles:

- A RS (like a TS) is not tailored to a school overtly. While you may subtly adjust your project descriptions to speak to a specific type of job, you do not refer to any job or department or application in the statement itself.

- Do not refer to any other job documents in the RS (ie, “As you can see from my CV, I have published extensively….”)

- As in all job documents, remain strictly at the level of the evidentiary. State what you did, what you concluded, what you published, and why it matters for your discipline, period. Do not editorialize or make grandiose claims (“this research is of critical importance to…”).

- Do not waste precious document real estate on what other scholars have NOT done. Never go negative. Stay entirely in the realm of what you did, not what others didn’t.

- Do not position yourself as “extending” or “adding to” or “building off of” or … [what follows is edited…]

- Do not refer to other faculty or scholars in the document. The work is your own. If you co-authored a piece…

- Do not refer to yourself as studying “under” anybody…

- Do not forget to articulate the core argument of your research. I am astounded at how often (probably in about 80% of client documents) I have to remind clients to …

- Give a sense of a publishing trajectory, moving from past to present…

- Make sure you are not coming across as a one-trick pony. The second major project must be clearly distinct …

- Use the active voice as much as possible, but beware a continual reliance on “I-Statements”, as I describe in this post, The Golden Rule of the Research Statement.

I will stop here. Readers, please feel free to add more in the comments. I will add to this post as further refinements come to mind.

Similar Posts:

- This Christmas, Don’t Be Cheap

- The Dreaded Teaching Statement: Eight Pitfalls

- What is Evidence of Teaching Excellence?

- The Golden Rule of the Research Statement

- How Do I Address Search Committee Members?

Reader Interactions

August 30, 2012 at 12:38 pm

I am interested in applying for Ph.D programs in the UK and they ask for a Research Proposal…is this the same thing as a Research Statement?

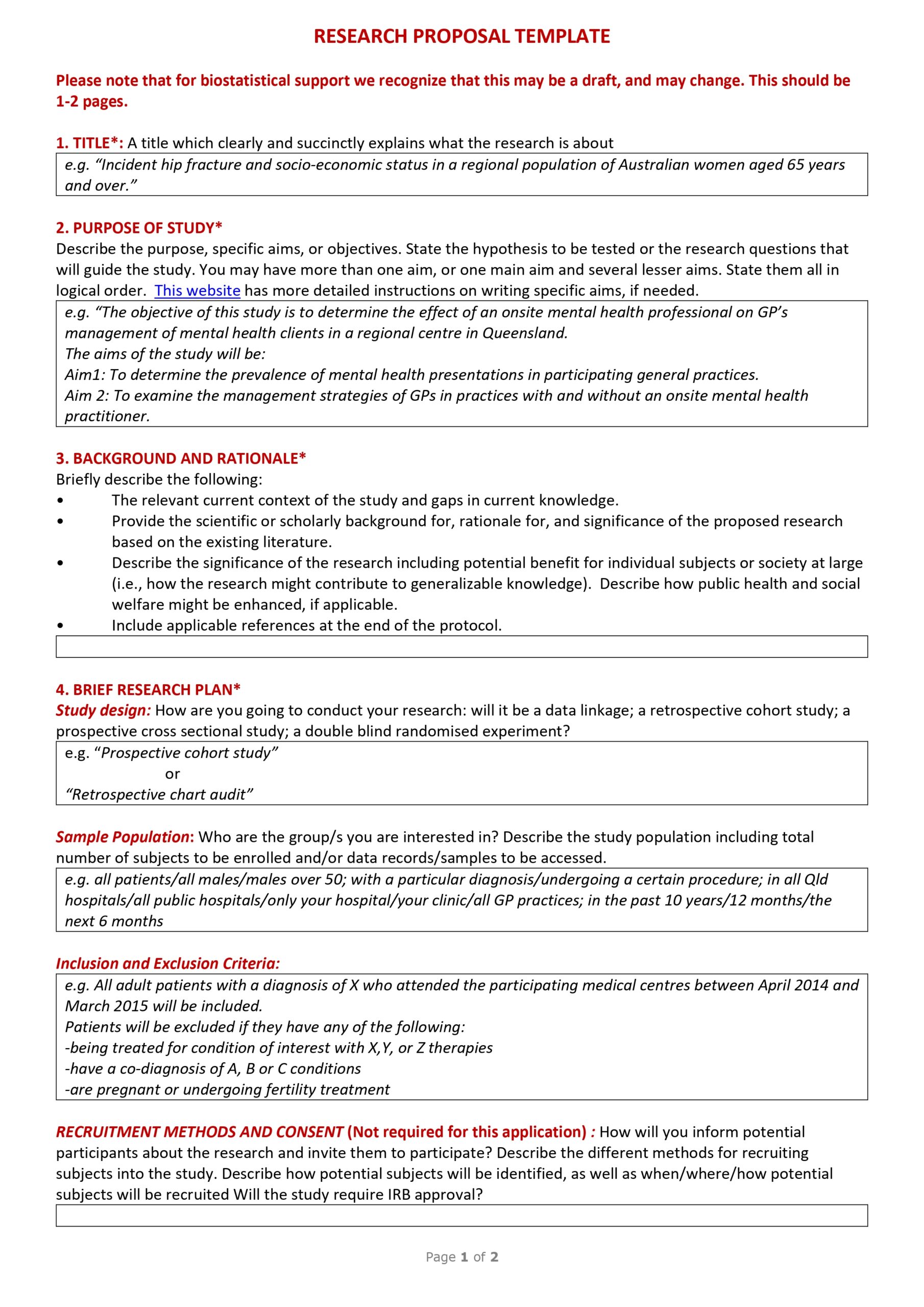

August 30, 2012 at 12:59 pm

No, they are looking for what you might think of as a research protocol, so literally your background, literature review, hypotheses and methods. You would need to convey how this is a unique area of research that is novel and adds to the existing literature; they are assessing the novelty of your research and how you would conduct the study. PhD programs in the UK are heavily researched based; you would need to show that you could literally hit the ground running to do your PhD. A major difference is that UK PhD’s usually take 3-4 years full-time and this is stringently enforced. I have a PhD from the UK and there are obviously pros and cons compared to the US system but you need to be a confident researcher if you’re planning to take that route.

August 30, 2012 at 1:28 pm

No: a Research Proposal is intended as a pitch for a specific project, or the research programme you will undertake within a specific timeframe (such as a PhD or a post-doc). A Research Statement is used for applications for jobs and occasionally fellowships, and outlines the research you have *already* completed, and what you plan to pursue next. So your Research Statement will describe your doctoral thesis as a finished (or very nearly finished) product, and list the publications generated by your doctoral work and any subsequent projects.

August 30, 2012 at 2:12 pm

No, a research proposal is a description of what you would like to do for you PhD research. Essentially an outline of your expected PhD thesis (which can of course change later once you’ve been accepted and started working on your research) with a short lit review, an identification of a research gap that you plan to address and a brief outline of proposed methods.

August 30, 2012 at 12:46 pm

What about in the case where you are asked to provide a “Teaching and Research Statement” in addition to a statement of your teaching philosophy? I have gone for a one page statement which focuses on my research but links that to my teaching so as not to repeat too much from my philosophy or my cover letter. Any thoughts from others?

August 30, 2012 at 5:02 pm

I’m preparing a “Teaching and Research Statement” and have kept it at 2 pages (1 page for teaching and 1 for research). Do others think that’s OK? If it’s 1 page total, for both teaching and research, then how much could I really say? That’s so short, less room than a 2-page cover letter.

September 1, 2012 at 9:05 am

Yes, on occasions where jobs ask for that combined statement, I always work with clients to do a two page document, with one page devoted to each part.

September 20, 2017 at 10:09 am

Found the blog this week… I wish I found sooner!! Gongrats! One add-on question: in the case of a combined document, would you start with the RS and then TS, or it doesn’t make much difference?

September 21, 2017 at 9:56 am

I’d start with RS in general, but it would depend on the job – teaching-centric jobs would be the reverse.

September 16, 2021 at 7:13 pm

Hello, so glad I found your blog! The application I am putting together requests a statement of research philosophy, a teaching philosophy, and a combined research and teaching interests statement. In this case, would one page combined be sufficient with a much briefer review of interests in each area (given that so much more detail is available in the philosophy statements)?

August 30, 2012 at 1:21 pm

In my field in R1 jobs it is pretty rare that one is asked to prepare a research statement. This stuff does in the cover letter. Any insight into when one is asked for this?

August 30, 2012 at 1:27 pm

Field dependent, but as KK points out, you should have a research paragraph (or two) in your cover letter anyway…

August 30, 2012 at 1:26 pm

The above echoes my experience. One obvious caveat would be postdocs and such that either stipulate a longer statement length (the ol’ two page Fulbright IIE style), or suggest a wider range of material should be included.

August 30, 2012 at 2:50 pm

Thanks for the tips – a very useful post! How do these apply to postdoc applications?

– If the required length of the research statement is not stipulated, would one page also be sufficient for a postdoc application?

– Also, what is the convention for naming (with title) your advisor in the cover letter – should this also be avoided?

August 30, 2012 at 1:30 pm

In terms of the 5-paragraph model, where would you include subsequent projects, i.e if you are on your second or third post-doc. Do you give equal time/space to each project you have completed, or just the basic run-down and focus more on current or upcoming work?

August 30, 2012 at 3:46 pm

This is a good question. If you’re well beyond the diss, then you will use the “diss” para to describe your most important recent research, then at the end of that para or in the next one, indicate with a sentence or two the research that preceded it (demonstrating an organic connection between them if possible), with a major publication or two. And then from that, move to the next major project. So it’s a bit more of a zig zag, with the past sandwiched between (and subordinate to) the present and the future.

August 30, 2012 at 3:47 pm

Let me respond in a different way. if you are a senior scholar applying for an associate or full position, then your RS may certainly be longer than one page (although I’d cap it at two, myself). The one page rule applies most to those who are seeking their first or second assistant professor position.

August 30, 2012 at 4:10 pm

Where is the appropriate place to highlight (solo or lead-author) publications developed outside of your dissertation work? For example, a secondary area of inquiry that runs tangential to your core area of research.

September 1, 2012 at 9:08 am

That can get another paragraph. Now, this is tricky. If you have an *extensive* secondary body of work for whatever reason then in that case, you may be one of the people who can go onto two pages. This is rare—most job seekers just have their diss, its pubs, and a planned second project, and that can all go on one page. If you have a small body of secondary research, that can also still fit on one page. So the judgment call comes in knowing how much is “too much” to legitimately fit on one page. Questions like that are what people hire me for!

August 30, 2012 at 5:07 pm

I’m wondering about repeating myself. The 5-paragraph format for the research statement is very similar to the format for the cover letter. So should we more briefly discuss points we’ve fleshed out in the cover letter, to save the space for points that are not in the cover letter? Or is repeating the info in the research statement and cover letter OK/expected? (If you’re repeating yourself, then there’s the issue of figuring out X different ways to say the same thing.)

I answer this in another response, but basically you have the space here to go into far more detail about the scholarship itself—the methods, the theoretical orientation, a very brief and edited literature context, and a strong statement of contribution to the discipline. You can give chapter summaries of about one sentence each, and you can also describe the publications in a sentence or two (not possible in the job letter). And the biggest thing in the RS is the description of the second project. The cover letter devotes a very short paragraph to that, of approximately 2-3 sentences, but in the RS, it can get a full-sized paragraph.

January 21, 2020 at 1:11 pm

This is a very delayed response, but I’m hoping you still get the notification! I want to make sure that it’s appropriate to cite specific authors in describing the lit context. Thank you much!

August 30, 2012 at 7:30 pm

I struggle with para. 4 because I have 3 major post-diss projects in mind. 2 are off-shoots of the diss. material in the sense that they contribute to the same field as my diss. but look at very different aspects than my diss. covered. The 3rd project is a completely different trajectory with little-no connection to my diss. I fear it sounds “out of left field” as they say, but it’s my dream-project. So I’m not sure how to communicate all of these interests. Thoughts?

September 1, 2012 at 9:12 am

This is a huge question, and one that I’m going to edit the post to include. It is critical that no job seeker propose more than one next project. This may seem counter-intuitive. Surely, the more ideas I have, the more intellectually dynamic I look, right? Wrong. Anything above one major post-diss project makes you look scattered and at risk in your eventual tenure case. A tenure case requires a clear and linear trajectory from the diss, its pubs, to a second project, and its pubs.

Now, I hasten to add that this rule applies most firmly in the humanities and humanistically inclined social sciences. In the hard sciences, and experimental or lab-based social sciences, the rhythm of research and publishing is different and different rules might possibly apply, with a larger number of smaller-scale projects possible. But in book fields, you need to do one book…and then a second book…for tenure.

September 4, 2012 at 9:49 am

thanks Karen, I will keep this in mind

October 22, 2016 at 9:01 am

Do you know of a source for more information about this problem from the hard sciences and engineering perspective?

August 30, 2012 at 10:02 pm

In a research proposal (i.e., for a specific postdoc), what is the appropriate length of time for revising a dissertation for publication? My instinct is, for a 3-year program, to devote 2 years to revision/publication, and one year to the new research project. Is this too slow, too fast, too hot, too cold, or just right?

September 1, 2012 at 9:00 am

To my mind that is exactly right. However, I know of a major Ivy League 3-year fellowship that expects 3 years to be spent on the first book. I find that baffling. As a postdoc you have few teaching obligations and almost no committee/service work….why would it require three years to transform your diss to a book in that environment? This particular app does allow you to *optionally* propose a second project for the third year, and I recommend that all applicants do that.

August 30, 2012 at 10:07 pm

Karen, thanks for this and all of your other helpful posts. I’m a sociology phd student at a top department, and served on the hiring committee last year. Not a single applicant made it onto our short list (or even the “semifinalist” list of 30 candidates) with less than a 2 page research statement (and most were 2.5-3 pages). Maybe my institution is unique, or maybe they were poorly written and not as detailed as they could have been in one page. But I just wanted to share my experience for any sociologists reading this blog.

September 1, 2012 at 9:01 am

That’s interesting. That would seem to be fetishizing length qua length…. the work can be described in one page when the one page is well written.

September 4, 2012 at 7:45 am

I’m in a top psychology program, and I echo this– I have read many research statements for short-listed candidates in my department, and I have never seen a research statement shorter than two pages, and typically they are three or four.

September 5, 2012 at 10:27 am

I crowd sourced the question on FB and most responses said they favor a one page version. I suppose this could be a field specific thing. The humanities are def. one page. It strikes me that social sciences and psych in particular might be tending toward longer. I really wouldn’t recommend more than two though.

September 17, 2013 at 8:58 am

I am writing my own R.S. and have asked for copies from colleagues in both psychology and the life sciences. In all cases, the R.S. has been at least 4 pages. So, it doesn’t seem specific to just the social sciences. Maybe it’s a difference in the prestige of the universities, with R-1 preferring lengthier research statements, while liberal arts universities prefer a smaller research statement. Most candidates at R-1s also have lengthier C.V.s which would imply a longer R.S. no?

September 17, 2013 at 9:48 pm

October 15, 2013 at 8:17 pm

I’d seen a lot of recommendations online for RSs to have a hard limit of either one or two pages. When I asked my own (Education) professors about it, they said that two pages sounded short and that they’d seen everything from one page to ten pages but recommended keeping it no longer than 3-4. Right now mine is 2.5 pages.

August 30, 2012 at 10:24 pm

Thanks for this really helpful post! A few quick quick follow up questions that I’m sure may benefit others who have similar concerns. 1. As we situate our dissertation research within our fields (paragraph 2/3) does this mean we have license to use field-specific vocabulary or theoretical language? (as opposed to the cover letter, where we’re writing in a much more accessible voice?) 2. Also, many of the items in the 2nd, 3rd, and 4th paragraphs you suggest would seem to overlap quite extensively with the cover letter, making it hard to properly differentiate what goes where. For schools that require this statement, should we just strip down our cover letter and include some of these details in our research statement? Or, is there something I’m missing? And finally, 3. A bit of a mega-question, but what is the *point* of a research statement? Why do some schools have them? Understanding the reasons some departments request it would be helpful, especially in differentiating from the cover letter. Sincerely, Grad-student-on-the-market

September 1, 2012 at 8:58 am

Never strip down the cover letter. That is the document that opens the door for the reading of the other docs such as TS and RS. The distinction of the RS is that it can be more field-specific and far more detailed than what you can provide in the single para devoted to the research in the job letter. You can also situate the research vis-a-vis scholarship in the field (carefully and within limits, remembering the rules that the work described is YOUR OWN, and never to devote precious real estate to what OTHER PEOPLE have or have not done).

You can also briefly sketch the chapters of the dissertation as long as you give no more than about one sentence per chapter. One of the most tedious pitfalls of the RS is the exhaustive chapter-by-chapter description of the diss.

And re #3: that’s a great question. What IS the point? Basically, if the cover letter and CV open the door to your candidacy for the very first cut in a search comm member’s mind (say, from 500 to 100), then the RS gives more detailed indication that are a hard-hitting scholar with a sophisticated research program and a body of dense scholarship that will yield the publications you need for tenure, and also answer the question more clearly as to your fit for the job and for the department.

August 31, 2012 at 9:32 am

Is the Research statement the same as the diss abstract? My field seems to consistently ask for diss abstract and all the examples I have seen are two pages, with page one being a discussion of the project, it’s contributions, etc. and the second being ch descriptions.

August 31, 2012 at 12:05 pm

No, the diss abs. is an abstract of the diss! Common in English.

November 2, 2012 at 11:26 am

thanks for making this distinction. is there a length limit on the diss abstract?

September 1, 2012 at 12:08 pm

I’m in a STEM field and would disagree with limiting the RS to 1 page. Most research statements that I have seen (for searches at R1 schools) have been 2-3 pages. One aspect of this which may be different in STEM fields compared to social sciences/humanities is that in STEM you really should include between 1 and 3 figures in the research statement. We like data and we want to see yours. My research statements always included at least two figures – one from published work and one from a cool new result that wasn’t yet published (but was either in review or accepted but not in press, making it hard to scoop). Depending on the school I also sometimes included a picture of a cool method (it’s a pretty pic too) – that was typically done for SLAC apps where I was also making the point that I would be able to involve their students in that research. With figures that are actually readable, there is no way to get away with less than 2-3 pages for a research statement. Again I think this may be STEM specific but given how scientists read journals – most folks go straight to the figures and then later look at the text – this is probably a good tactic in those fields.

September 4, 2012 at 12:21 pm

I love the idea that a research statement could include figures. I’ve never seen one like this (I’m in biological anthropology) and have never thought this would be something that could be included.

September 5, 2012 at 10:25 am

In the hard sciences this is not uncommon.

September 1, 2012 at 4:33 pm

Forgive me for bringing up/asking the perhaps obvious. So no master’s thesis mention?

Also, you mention not providing two second projects. Would that still apply if one is far-away foreign, and the other local?

September 4, 2012 at 9:43 am

Another question on the MA – mine was empirical research published in a general science journal (Proc B) so I definitely need to mention it. But my question is whether I should explicitly say that this was my MA project?

I’m entering the job market ABD.

September 5, 2012 at 10:26 am

avoid framing yourself as a student, particularly MA.

September 4, 2012 at 9:32 am

I’d say, especially for humanities fields, the “baseline” of 1 page single-spaced that Karen mentions is correct. As she says in the post, there are obvious exceptions (STEM might want more, specific jobs might want more), but assuming 1 page without any other specific information is a good standard rule. In fact, from my own experience, 1 page generally works for any document that isn’t your vitae or your job letter.

The reason I say this is because you basically want to make a good impression pretty quickly. Job committees have limited time, and they are probably going to scan your document before deciding whether it is worth reading it in full. I’d also suggest reading up on document design, and making your documents easy to scan by putting in effective headers that give a powerful overall impression of your candidacy. You should also design those headers to lure your readers to look at your work more closely.

September 4, 2012 at 12:04 pm

I’m going through the process right now as an ABD, following advice from many quarters including TPII and a number of junior and senior faculty in top departments in my field. I have collected sample statements from 5 successful candidates and they are all in the 3-5 page range, closer to what the sociologist above describes. I have not seen a single statement at one page.

September 4, 2012 at 6:23 pm

When proposing future research, do you still recommend we avoid stating what others have NOT done? Can these types of statements, “yet others have not yet address xxx and yyy”, be helpful in justifying the need for our proposed topic?

It is always good to indicate, rather briskly, “in contrast to other work that has emphasized xxx…” or “no studies to date have examined xxxx.” What I am cautioning against is the very common temptation among young candidates to harp on and on about other scholars’ shortcomings, or how their diss topic is “badly understudied” (a phrase I’d give my right hand never to have to read again). Can the self-righteousness and just describe your work and its contribution.

September 7, 2012 at 12:54 pm

thanks for the post!

I had a question about not giving the sense that one is “extending” past work. As you say in this post: “Avoid the temptation to describe how you will “continue” or “extend” your previous research topics or approaches.”

In my case, my book will be comprised of about half new material and half dissertation research. “Extending” feels like an accurate word to describe the relationship between the diss and the book. Like, ‘Extending my diss research on xxx, the book offers new ways of thinking about issues yyy and zzz. …’

So is this the wrong way to describe the relationship between book and diss (even if it seems accurate?) What are *good* ways to talk about the relationship between the two when the book really does “build on” groundwork laid in the diss?

September 7, 2012 at 2:45 pm

This question actually requires a blog post on its own. There is a weird fixation among job seekers on the word ‘extend.” I don’t get it, and find it mystifying and irritating. Of course books or second projects will typically have some organic connection to the diss. But the insistence on saying that they “extend” the diss makes the DISS primary, and the new work secondary. But on the job market and in your career, the diss must NOT be primary. The diss is something a grad student writes. You are not applying to be a grad student. You are applying to be professor. So it’s the new material that should have primacy. Yet young job seekers are so myopically fixated on their diss that all they ever do is harp on and on about how every single damned thing they’re going to do next is basically a reworking of the diss material. Yuck! Who wants that?

As you can see, I am a bit reactive at this point…

September 7, 2012 at 2:53 pm

ok! I hear you saying that it is more about not giving the sense, throughout the letter, that the book is a mere “extension” of the dissertation, and that typically this word is overused by applicants and thus gives that impression. That makes sense. Personally, the sentence I noted above about is my only reference to the diss–the rest is all about the book and future project since I’m a postdoc and the diss is really in the past. 🙂 thanks!

September 15, 2012 at 7:19 pm

Thanks for the helpful guidelines, Karen!

How would you recommend shifting the focus of the paragraphs for those of us going on the market as postdocs? For me, I’ll have completed 2 years of a postdoc in Education, and so I have many new projects more relevant to my future research than my dissertation was. However, except for a few conference proceedings, I have no publications on my postdoc research yet. In fact, some of my proposed “new” research will be to continue what I began in my postdoctoc. Do hiring committees look down upon this?

Thanks for your advice!

September 22, 2012 at 5:58 am

Does anyone here know if this is an effective format for British Oxbridge postdocs as well? I’m finishing a UK PhD and pretty keen to stay in the country, and obviously these are madly competitive. I know my research is good, but the eternal question of how to make anything in the humanities sound important to other people, you know?

October 13, 2012 at 5:31 pm

Please tag this post so that it appears under the teaching and research statement category!

October 13, 2012 at 9:05 pm

October 29, 2012 at 4:38 pm

Karen: “Just never simply ASSUME that longer is better in an RS or in any job document”

Yours Truly: “Just never simply ASSUME that they are going to read what you write. Often they a long CV, RS, and list of publications to tick all the boxes and cover their backs.”

November 20, 2012 at 1:35 pm

If I consider teaching and curriculum development part of my research, is it okay to mention this in the RS–specifically if written for a university more focused on teaching than research? My assumption is that R1 schools would look down on this…?

November 20, 2012 at 2:56 pm

Unless you’re in the field of education, you can’t include teaching or curric. in a RS.

December 16, 2012 at 11:44 pm

Than you very much Karen. A valuable guide

December 31, 2012 at 7:37 pm

Does the rule of no more than one future project description apply to the field of developmental psychology?

*Please delete above post with my full name, I did not realize it would post

January 1, 2013 at 9:35 am

You would need to investigate that among your profs and colleagues. I don’t know the expectations of all fields well enough to advise.

September 18, 2013 at 4:10 pm

I wrote a research statement and asked a friend in my department look at it. She said I should include a paragraph on collaborative work I’ve done as well. The problem is that all of my “collaborative” work is really “assistance”. I do not want to frame myself as a graduate student, but I also see the value in highlighting my ability to produce scholarship with other people. Any thoughts on this, Karen or others?

September 27, 2013 at 8:37 pm

Many thanks! I searched through a tone of sites for samples and examples, but yours is the most helpful.

September 29, 2013 at 7:32 am

Does one use references and include a reference list in a research statement?

October 24, 2013 at 10:40 am

I’d like to know the answer to this question, too.

Karen’s advise (Do not refer to other faculty or scholars in the document. The work is your own. If you co-authored a piece, do not use the name of the co-author. Simply write, “I have a co-authored essay in the Journal of XXX.”) sounds like you shouldn’t, but I personally see more advantages (that’s what scholars are used to, you can reference one paper multiple times without much space, you give the full information of your papers) then disadvantages (mention other authors).

So some remarks on using reference lists/bibliographies would be really interesting.

October 11, 2013 at 2:17 pm

You mention that P4 should include: “A summary of the next research project, providing a topic, methods, a theoretical orientation, and brief statement of contribution to your field or fields.”

How specific do you need to get with that information? I want the review committees to see that I have good, viable ideas for future research, but at the same time I’m worried that by giving too many details my ideas are liable to get stolen…not to mention that more detail means a lot more space on the document and I’m already finding it really hard to keep it to 2 pages even just using pretty general info. All the example research statements from my field that I’m reading make generalized statements like, “This area of my research will focus on developing and characterizing the structure of smart multifunctional materials for infrastructure applications,” but that just doesn’t seem like enough…

Thanks for the advice! Your blog has been so valuable as I am preparing my application package. 🙂

October 24, 2013 at 8:52 am

Hi Karen, I am applying for a few Phd positions & programs around the world, and some programs ask for a research statement, some for a statement of purpose. I fell Ill during my master’s studies and it had impacted my studies to the point of taking a leave of absence(and is known by my referees). As I understand, I can mention that in a SOP, but not in a research statement. Is there anyway I can communicate to the admissions committee about my situation (within the scope of my application) ?

October 30, 2013 at 7:13 am

Hello, Karen, I am an old follower returning. In a research statement, do you give considerably less space to what is already published, books and articles, and much more space and detail to describe projects(s) in progress or about to be launched as research proposal applications?

October 31, 2013 at 7:32 am

I recommend balancing about half and half; in the case of very young/junior candidates, though, the previous/current stuff is going to far outweigh the future stuff.

November 6, 2013 at 12:32 am

I am applying to an R1 and part of the app package asks for a “statement of research interests”. it sounds self-evident, but this is different from a research statement, right? They are, in fact, wanting to know what my future research projects are, to ascertain if i am a good prospect, correct?

Many thanks, Karen and co.!!!

November 8, 2013 at 10:40 am

No. it’s the same thing.

November 8, 2013 at 2:35 pm

Hi, I am applying to graduate school, and some programs ask for a research statement. I have not done any independent research, but have worked in a lab under a postdoc for three years. As a undergrad, is it okay to refer to the postdoc by name and say that I was assisting? Should this be structured any differently than the model you gave above? Thanks!

January 20, 2014 at 5:02 am

I’m applying for a PhD scholarship and I’m required to write a research statement. Is there any different format for a PhD student to be or just follow the same as per above?

Thanks a lot!

February 7, 2014 at 10:58 am

Hi, Could you please let me know if it is proper to mention some of projects in a certain master course that one took? I asked this because I am applying for a position that almost there is not a direct relation between my master thesis and my prospective PhD supervisor’s research interests. Thank you in advance.

February 21, 2014 at 11:23 pm

If some of your research background was for a government agency and your results went to government documents and forms, are you allowed to include it in your research statement. For example, I am applying for a job that calls for a research statement in which I would be designing stream sampling plans and in the past I worked for state government designing and implementing SOPs for stream sampling and EPA reports. This experience is much more applicable to the job than my dissertation research is. In other words, is the RS more to show I can do research and think like a researcher or that I have done similar research in the past?

March 6, 2014 at 10:00 am

Hi, This post has been really helpful to me. I have a question about citations in a research statement. Should I cite relevant or seminal studies? Or is a research statement assumed to be written out of the authors own confidence, experience, and general knowledge of their field of study? If yes to citations, is there an optimal amount? Thank you!

April 26, 2014 at 11:01 am

I dont understand why I cannot name who I collaborated with, or worked with and claim complete ownership. Most of all disseration ideas comes out of a collaborative effort. Seems kinda lame to suddenly act like every idea is all mine without giving due credit.

April 26, 2014 at 12:00 pm

it’s not claiming ownership. It’s focusing on the work that YOU did as part of the project and not dispersing attention to other scholars, in this particular document.

April 28, 2014 at 10:09 am

I disagree. All of your recommendations are valid except for this one. In science and engineering, almost all dissertation work is collaborative; that’s how it works, either through industry applications, a reagent or mathematical technique, opportunity to apply theory to projects etc. Of course, the student has to compe up with the research questions and hypothesis and methodologies but it is very rare for one lab to have everything that the student needs in-house and even rarer for the work to be done in complete isolation (you don’t see that many two author papers in STEM fields these days). Including names of other people would actually be a good thing as it shows a willingness to interact and collaborate with a diverse set of people, picking up new skills and perspectives; this is how science is done these days. Of course the research thrust should be from the individual, but that is like a given.

October 26, 2014 at 8:00 pm

I am also in a STEM field, and all of my research has been collaborative to one degree or another. In my tenure-track applications last year, I mainly phrased my research statement to say that I work with YYY group on YYY, lead studies of ZZZ within the ZZZ Collaboration, and so on. I didn’t get any interviews.

This year I received some feedback from a new letter writer (and current collaborator), who thought that last year’s statement made it hard for outsiders to tell what specific ideas I had and what I specifically did about those ideas. When I rewrote my research statement to focus on those issues this year, I ended up with a stronger document that didn’t need to mention my collaborators at all — not because I tried to claim credit for everything, but because I wrote about my own contributions rather than the corporate identity.

Since jobs go to individuals and not corporations, I am strongly inclined to agree with Karen’s advice, even for STEM fields. In fact, it may be even more important for those of us with highly collaborative research to discuss our own contributions and leave our colleagues out of our research statements. The CV/publication list makes it clear that we interact and collaborate with others. The difficulty is to demonstrate what I actually did as author #13 (in alphabetical order) that makes me actually worth hiring.

April 29, 2014 at 5:03 am

Dear Karen, I am applying for a faculty position and have been asked to provide along with the usual CV and cover letter “Research Program Plan” and “Teaching philosophy”. Could you please or anyone inform me if the “Research Program Plan”is the same as the RS or a detailed research proposal? Additionally, should I include in the teaching philosophy an experience in my undergraduate that has shaped my teaching philosophy? Finally, should my TP include any courses ever taught or course proposals? Your candid response will be appreciated. Thanks

April 29, 2014 at 8:00 am

The RPP is the same as a RS. Please read all my posts on the Teaching Statement for more on that—do NOT include your undergrad experiences. Check out my column in Chronicle Vitae for more on that question–it’s the column on how to apply to a Small Liberal Arts College (SLAC) job.

July 16, 2014 at 3:39 am

Dear Karen, I am applying for a postdoc position in Spain and have been asked to provide along with CV and references, a “cover letter with a description of research accomplishments and statement of overall scientific goals and interests (approximately 1000 words)”. This messes up the usual structure I have in mind. What do you suggest? Two different files or a hybrid between them in one file? thanks

September 17, 2014 at 1:12 pm

Hi Dr. Karen,

I just wanted to say thanks for such an awesome article and the pointers.

Cheers Sajesh

October 13, 2014 at 4:15 pm

I am a bit confused about what a “statement of previous researc” looks like. Any insights?

October 14, 2014 at 12:59 pm

basically this RS doc, without anything about future research.

October 22, 2014 at 5:49 pm

I’m applying for a tenure track position in Strategic Management but my dissertation was on a topic related to my field, pharmaceuticals. How do I craft a RS if I really haven’t thought about future research in topics related to management but my teaching experience and work experience (line management) is directly related to management/leadership?

October 27, 2014 at 12:38 pm

Hi, Dr. Karen,

I’m applying for tenure-track positions in Computer Science. My current research focus (and for the last year and a half in my postdoc) has been in “data science”, primarily applied to biology; my dissertation work was in computational biology. I don’t want to focus on the biology aspect; I see this research being more broadly applicable. I also have significant industry experience from before my PhD; I spent 6 years doing work that was very relevant to this field of data science (in finance and in global trade), and I’d like to tie that industry work into my research statement. What do you think about this? Some have told me I should just talk about my postdoctoral research, while others have said the industry experience, since it’s very relevant, makes me a stronger candidate and I should tie it and my dissertation work into my postdoc and future research.

What are your thoughts? Thanks!

October 31, 2014 at 7:41 am

I am a young scholar in Communication. My research plan includes a description of past and current research projects (dissertation + 4 subsequent projects) and a description of short and long term projects (work in progress and three major research projects I want to undertake). I have been told this is not enough and I need more projects in my proposal. Only 2 pages for so many projects (including a detailed timeline) does not seem feasible.

November 3, 2014 at 7:50 pm

Dear Dr. Karen, First, let me thank you for your website. I’ve been reading it carefully the past few weeks, and I’ve found it very informative and helpful. I’m in something of a unique situation, so I’m not sure how to best make use of your advice on the RS, which seems aimed at newly minted PhDs. I have been in my current position, teaching at a community college, since 1997. During this time, I completed my doctorate (awarded in 2008). I taught abroad on a Fulbright scholarship in 2010-11, and during that time revised and expanded my dissertation for publication (this included contextual updates and one complete new chapter). I was fortunate enough to get a contract, and the book appeared in 2012; the paperback is coming out this month. Given my experiences, I want to make the move to a 4-year institution, if possible (I realize the odds are slim). A few of the ads I’m looking at are asking for a research statement. So, how do I best handle my circumstance in the RS? The dissertation and book are largely the same. Where should I provide the detailed description of my project and the chapter summaries (as you’ve recommended)? How can I avoid redundancies? Your advice is appreciated.

November 5, 2014 at 3:02 am

Dear Dr Karen,

I have read parts of your blog with great interest .. I need some advice.. if you have a research statement where one is combining two different streams of research, is this generally a good idea or would it be better to have a single stream? At the moment mine RS is nearly 4 pages (I have a short 3 page version of this).

Can you also give advice about an “academic plan” is this simply the 1-2 page “teaching statement”? Do yo have pointers/advice for this?

best regards,

November 9, 2014 at 10:50 am

Greetings Dr. Karen, hope this message finds you well.

I am applying for my first post-doc fresh out of my PhD. But I also did a Master’s prior to my PhD which resulted in publications and a thesis. That being said, do you think I should add my Master’s research to my research statement? I planned on putting it just above my PhD research. Thanks a lot 🙂

November 10, 2014 at 11:46 am

I’m wondering if it’s acceptable to mention personal qualities in an RS, such as being a collaborative worker or being able to acquire new skills rapidly (with concrete examples, that is). Normally I would put that in a cover letter, but it seems that cover letters are a thing of the past.

November 10, 2014 at 10:01 pm

No, that is not the place for that. Really, no part of the academic job application is the place for that.

November 19, 2014 at 6:47 am

Dear Karen, a special question… how do your rules above changing when writing a research statement for someone who has 4+years of AP experience and tons of research after dissertation?

Yours and other suggestions seem to be from the point of view of a grad/post-grad. Need some good insight/advise on how to to tailor a description of your research that spans many different threads and is perhaps quite a bit different from your dissertation.

November 26, 2014 at 9:51 pm

Dear Karen,

Thank you for this useful post. What about career goals? Does one mention those in the research statement or cover letter, if at all? For example, for NIH career development awards one has to write a one-page personal statement that includes career and research goals. The two are often aligned.

More specific, can /should one say things along the lines of: “My primary career goal is to become a successful independent investigator focused on xxx research.” or “I plan to secure a faculty position at a major university or research institute where I can engage in cutting edge research on xxx.”

Thank you for your insights.

Best regards,

November 27, 2014 at 9:19 am

This is more industry/business talk and not typical for academia. If you are articulating a complex research and teaching plan, it is UNDERSTOOD that you’re aiming for an academic career.

November 30, 2014 at 9:58 am

Dear Prof Karen Greeting, hope this greeting finds you well I have read this blog with great interest…In my opinion, writing teaching and research statements are very difficult than writing a PhD research… For your info that I have finished my PhD research with 17 publications in 2 years and 4 months and since that time (2 years)still writing my research statement and not finish yet..

November 30, 2014 at 10:13 pm

Thank you for your reply! Leaving this out will save me a lot of space. Best regards

January 14, 2015 at 11:17 am

I am applying for a grad program in engineering and the university requires me to write a research statement. I have no prior research experience nor have I thought about any topics for research. How do I approach this problem?

January 14, 2015 at 2:29 pm

I’m sorry, I don’t provide advice on applications to grad programs.

January 16, 2015 at 1:07 am

Okay, thank you.

January 23, 2015 at 11:33 pm

Hi, can I cite a reference in statement of research interests for a postdoctoral position? If so, do I include the reference of the citation at the bottom of the page? Also, do I title my statement of research interests page as ” statement of research interests”? Thank you.

February 4, 2015 at 10:18 am

I am applying for a 1 yr postdoc in the social science and humanities. The initial position is offered for one year with a possibility of renewal for up to one more year.

My plan is to use the postdoc opportunity to convert my dissertation into a book manuscript. I have a 2 yr plan which i believe is realistic. Roughly first yr review expand literature, reassess chapters, conduct addition interviews to build on insights. The second year would be analysis of data and writing and revising. How do I reduce this to a yr? Or do I propose it as a two yr endeavor?

February 5, 2015 at 9:39 am

to be blunt, you should skip the expanding of the literature, the reassessing, and the additional interviews. Things like this are what delay books. Transform your diss into a book mss with a one-year writing plan, and submit it for publication by the end of that year. Early in the year (or before you arrive) you send out proposals for advance contracts. This is what makes for a competitive postdoc app.

February 27, 2015 at 9:31 am

Thanks for your post. I am writing my RS with your comments as my reference. However, I have some concerns and wish you could offer some suggestions.

You mentioned that when writing RS, we should 1) Do not waste precious document real estate on what other scholars have NOT done. Never go negative. Stay entirely in the realm of what you did, not what others didn’t; and 2) Do not position yourself as “extending” or “adding to” or “building off of” or “continuing” or “applying” other work, either your own or others.

My doctoral thesis is to theoretically extend a theoretical model and empirically test it, which implies that the developer of the original model missed something to consider and I help do it. But if I take (1) and (2) into account. I may not be able to describe the rationale of my dissertation and further show the contribution.

In addition, (part of) my future directions is to increase the generalizability of the extended model, which means that I may apply it to my future research; and to discuss a potential issue in the extended model. However, if I take (2) into account, it seems that I cannot address it in the RS. Interesting enough, I found a number of model developers applied their developed theoretical models throughout the year with different research focuses and to validate the model. Should not such a way recommended to be addressed in the RS? Just a bit confused.

Would you please kindly help with the above? Thanks a lot.

March 4, 2015 at 2:16 pm

I am in public health and am a generalist so I have conduct research on a wide variety of topics. My masters thesis was on cesarean delivery guidelines and my dissertation is on the effect of legislation that bans certain breeds of dogs. I don’t want to pigeon hole myself into a specific topic area, but also don’t want to seem scattered. My research is all related, because it is on health systems or health policy, so I am trying to unify my RS with the theme of research that improves population health. Would you suggest that I list only my dissertation work and a future project that aligns with that, or should I also list my masters work and/or a separate project on a maternal and child theme?

March 11, 2015 at 6:19 pm

With regard to your recommendation to leave names of others out of the research statement, I am struggling with what to do for an edited volume with some *very* prominent contributors. I am the sole editor for the book, and I brought these contributors together. Should their names still be excluded from the research statement, or perhaps included elsewhere (perhaps in the cover letter or CV)?

Thank you for your very helpful postings.

March 12, 2015 at 7:20 pm

I find that many people overestimate the importance/prominence of the names and their value for any job doc. But if they include, like, Judith Butler and her ilk, then sure mention 1-2 such names in the RS.

July 7, 2015 at 12:51 pm

When applying for a faculty position (first job as assistant professor), would you recommend sharing the link of the applicant’s PhD dissertation thesis (if it is available online), if so where exactly?

Thank you very much for all the valuable information!

July 22, 2015 at 12:08 pm

Dear Karen –

I have a question for those out there encountering job openings for technical staff (like myself) with BS degrees requesting research statements. How do I write a RS based on this? Everything I’ve seen online has been geared towards RS for graduate programs or for those with newly minted PhDs.

August 14, 2015 at 6:19 pm

Dear Karen, Is there a difference between a “one page Research Plan” and a “Research Statement” ? Thank you for your generous advice through this blog.

August 29, 2015 at 8:39 pm

Thank you for the helpful posts. I am a postdoc applying for faculty positions, and they all ask something similar but different. It’s either a research statement, a statement of research interests, or a research plan. Do mean my previous research experience, what I plan to do, or both? A research statement sounds like a research summary, but I feel like I’m missing something. I appreciate any clarity you can bring on the subject.

September 2, 2015 at 9:22 am

Dear Dr. Karen, Some of the postdocs require to submit a C.V. and a list of publications. Does it mean that, for these particular applications, the C.V. should not include publications at all? Thanks!

September 2, 2015 at 9:49 pm

Sorry, just realized that had a wrong tab opened while typing the question.

September 24, 2015 at 10:01 pm

Hi Karen, This is a very helpful website indeed. I’ve been teaching university for 5 years (ever since finishing my PhD), and now am at a top 10 university (at least according to the QS rankings, if you put any stock in them). However, I’m applying for what I think is a better job for me at a research museum, one that would have me doing research and supervising grad students as well as doing outreach (something I’ve got piles of experience with). The application asks for a 2-page statement of scientific goals. I’m a little unclear as to how this differs from the research statement. Does it? If so, how? Thanks so much.

October 13, 2015 at 7:09 am

This was really helpful in writing a research statement. Thanks

November 11, 2015 at 1:17 pm

I see that some applications require a vision statement: “no longer than two pages, that outlines one or more major unsolved problems in their field and how they plan to address them.”. Any thoughts about the differences from a research statement?

January 14, 2016 at 7:28 am

How long should the research statement be if it has been requested as part of the cover letter?

May 20, 2016 at 8:24 am

Thank you very much for the very helpful advice, Karen!

I’m a final year PhD in psychology and applying for a postdoc now. The postdoc project seems very prescribed, to the extent that the announcement includes how many studies are planned to be conducted, what the broad hypotheses are and the broad theoretical background. Yet, the application involves an RS. What is the best way to frame a future research project here? Just tailor my diss to fit into the proposed postdoc topic?

July 1, 2016 at 3:10 pm

The place in this blog that should contain the 5-paragraph model doesn’t seem to be present. Instead I get a […]. Possibly a web configuration problem?

July 7, 2016 at 4:58 pm

Please read the para at the top of the post. This and a handful of other posts (about 5 in total) have been shortened so as not to overlap with the content of my book.

August 15, 2016 at 7:43 am

Thank you so much for your wonderful advice.

I have a question regarding the relationship between future research and the title of the position in question and how much overlap there should be between the two. Is it acceptable to propose research that is (this is history-based) from a slightly later/earlier period, or a slightly different geographical region than the position focuses on? Or is it better to align oneself entirely with the constraints of the position?

Many thanks!

August 23, 2016 at 9:46 am

I plan to limit my RS to two pages, but my career trajectory and publication record is a bit unusual. I’m a nationally regarded thirty-three year veteran high school teacher and recent postdoc (2013) from a top tier history department. I’ve been teaching alma mater’s most popular summer session course since 2014. It’s my mentor’s course, but he’ll be replaced with a tenured professor with an endowed chair upon retirement – as well he should. Cornell Press is “interested” in my diss, but…I’m currently revising the original proposal. I’ve also published as often in International Journal of Eating Disorders, Psychology of Women Quarterly and International of Alzheimer’s & Other Dementias as I have in The Journal of Urban History, Long Island Historical Journal and New York Irish History. I teach “the best and the brightest” at a socioeconomically and ethnically diverse public high school. I often publish with my adolescent students, so my scholarship is pretty eclectic. How, exactly, do I sell that to a hiring committee upon retirement from high school/transition to university teaching in June 2017?

September 12, 2016 at 6:29 pm

What is your take on using headings to organize the RS?

October 16, 2016 at 12:28 pm

I am up for tenure this year, and am applying for a tenured position at another school (mainly because I am trying to resolve a two-body problem). Given that I have been out of grad school for quite a while, have a book and many papers published, another book in progress, etc, should my tenure statement be longer than 1-2 pages? What would be a typical length for a mid-career statement?

October 17, 2016 at 1:14 pm

You can go onto a third page, if you’re on a second book.

October 19, 2016 at 4:08 pm

Hi Karen, I’m applying for tenure track jobs in English, and some applications ask for a research statement instead of a dissertation abstract, which is the more common of the two. I’ve been told that even if a dissertation abstract isn’t asked for, I should send one in with my application materials. If I’m asked for a research statement, do I still have to send a dissertation abstract as well? I’m a little worried about some overlap between the two (the obvious repetitions in contribution to the field, etc).

October 29, 2016 at 8:09 pm

I am being asked for a Scholarly Philosophy. Is this the same as a research statement? Are their any nuances of difference that I ought to attend to?

November 2, 2016 at 11:40 am

I’ve actuallynever heard that term. But I’d say it’s about the same as an RS, but perhaps with a bit more focus on wider contribution to the field.

November 8, 2016 at 10:55 am

Hello Karen,

I am a biologist on the market for a TT position (for more years than I would like to admit). I have always wondered whether including 1-2 figures or diagrams that help to illustrate your research plan would be helpful, and maybe even appreciated. I would like to know what you think.

We all know how overburdened search committees are. Pictures might help. Scientists are used to seeing such images in evaluating fellowship applications or grant proposals, why not research statements? I would think it would be a welcome change. So the potential benefit is you stand out and are more memorable, but you may also run the risk of alienating or offending someone, especially because this is uncommon.

Thanks for your posts and your book. I enjoy reading them.

November 10, 2016 at 9:53 am

Yes, in the sciences, diagrams are acceptable. It’s why science RSs are often 3-4 pages long. NOT in your cover letter of course.

January 12, 2017 at 11:56 am

Is it appropriate to put a date at the top or bottom of your statements?

August 4, 2017 at 5:32 am

I have been working as a fellow at a SLAC in the sciences and am directing undergraduate research that does not completely fit the mold of my usual work. Is it acceptable to mention these projects in the RS? Should I only mention ones that we will be trying to publish? Thanks

September 16, 2017 at 3:16 pm

Found some adjuncting this year after basically taking a year off last year. During that time, I was still working on getting material published from graduate school. This includes an article based on my dissertation. That articles is currently going through a revise and resubmit. The revise involves reframing and changing the names of important hypotheses. Do I discuss the work in my RS as it was discussed in my dissertation or talk about it as presented in this article yet to be expected for publication?

September 16, 2017 at 3:17 pm

accepted not expected

September 29, 2017 at 3:43 am

The part about not presenting your work as being better than other peoples’ is hard because constantly in your thesis you are setting up arguments like that! This is why my findings are interesting – because they are better than what other people did/found previously. The old paradigm was limited/wrong, hence my contribution is new/better. That is part of the academic writing genre! But I can see it will come across as much more mature if you downplay that in an application letter.

October 7, 2017 at 12:00 pm

Thanks for this great blog and the book!

I’m applying for a two-year postdoc. They say they want a “research statement,” but I really think they mean a proposal. This is short term, non-TT. I feel like the advice you give about “timeline, timeline, timeline!” is what will make this work better for this application.

Said otherwise, there is no time for a second project in this postdoc (or maybe you beg to differ?) Therefore it seems odd to talk about it.

October 7, 2017 at 2:11 pm

correct, they want a research proposal. Please read the chapters about that in my book. There is time in a two year postdoc to begin to launch a second project.

January 12, 2018 at 1:08 pm

I am just starting my higher education career. I only have my dissertation as published work. How do you suggest I handle to writing of my research statement given those circumstances?

August 27, 2019 at 6:26 am

Hi, I am a fresh PhD about to apply for my first job. I’ve been asked to write a scholarly agenda and am struggling to find what should be included in this. Any help would be great. The position is at a liberal arts college for a tenure track position in the biology department. Thanks

August 27, 2019 at 9:56 am

That would be the RS, and this blog post is about that. Also, check my book out, it has a chapter on this as well, updated from this post. If you need personal help, contact us at [email protected] to get on the calendar for editing help.

September 17, 2019 at 9:22 pm

Thank you for your excellent blog and book. I’m applying for a TT job where they don’t ask for a cover letter, but for a combined statement on research & teaching max 3p. In this case, do I still skip the letterhead and formal address? And what structure/format would you suggest?

Thank you in advance!

September 18, 2019 at 5:00 pm

if it’s truly not meant to be a letter, then don’t make it a letter! Just send a two page Rs and a one page TS nicely integrated into a single doc, with your name at the top.

December 23, 2019 at 6:23 am

Dear Karen, thank you for your wonderful advice here and in the book.I wonder regarding the the 1st para of the research statement. I have seen that many start by stating “I am a historian of X. My work focuses on Y in order to Z …

Is this what you mean by “A brief paragraph sketching the overarching theme and topic of your research,situating it disciplinarily”? would love to see an example of a good 1st para…

December 23, 2019 at 11:12 am

Lili, I provide examples to clients, so if you’d like to work with me, do email at [email protected] !

January 13, 2020 at 4:39 pm

I am just graduating as an undergrad and looking for entry-level research. Should I put something short on my interests if I do not have research experience, or is this section better to be left blank?

October 12, 2020 at 10:49 pm

Any differences with corona? I have two small ongoing projects related to covid. Other than that, I only have my thesis. Would mentioning these two projects be ‘too much’? They are not similar to each other: one has a clear logical link to my thesis, while the other is a new avenue that I want to pursue. They are not big enough to be my second project, but they are my current research. Should I mention them both? One? None?

January 6, 2022 at 11:51 am

Thank you for such detailed information! I searched on your site today in attempt to answer the question “what is a scholarly agenda,” and was pointed to this posting, which doesn’t seem correct, but I at least wanted to ask the question. Is the scholarly agenda a typical piece of writing for tenure processes? I’m about to go up for my three year review in a humanities-based tenure track position, where I am asked for one, and although I’ve written a draft, the university has no template, and in truth, I really don’t understand the aim of the scholarly agenda beyond the general idea of ‘where I want to be as a scholar and professor in three years.’ I’m looking for a blow-by-blow / paragraph-by-paragraph idea of how to structure the piece. I can’t find examples beyond law schools, which isn’t so helpful. Do you have any recommendations?

[…] Dr. Karen’s Rules of the Research Statement | The Professor Is In. […]

[…] Dr. Karen’s Rules of the Research Statement | The Professor Is In […]

[…] Dr. Karen’s Rules of the Research Statement (from The Professor Is In.) […]

[…] at the time. Could that possibly be good enough? I went out and searched the internet and I found Dr. Karen’s Rules of the Research Statement. One page long? That doesn’t sound so scary. I didn’t think I could get even my simple […]

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

- Who Is Dr. Karen?

- Who Is On the TPII Team?

- In The News

- Why Trust Me?

- Testimonials

- Peer Editing

- PhD Debt Survey

- Support Fund

- I Help With Custody Cases for Academics

/images/cornell/logo35pt_cornell_white.svg" alt="how long should research statement be"> Cornell University --> Graduate School

Research statement, what is a research statement.

The research statement (or statement of research interests) is a common component of academic job applications. It is a summary of your research accomplishments, current work, and future direction and potential of your work.

The statement can discuss specific issues such as:

- funding history and potential

- requirements for laboratory equipment and space and other resources

- potential research and industrial collaborations

- how your research contributes to your field

- future direction of your research

The research statement should be technical, but should be intelligible to all members of the department, including those outside your subdiscipline. So keep the “big picture” in mind. The strongest research statements present a readable, compelling, and realistic research agenda that fits well with the needs, facilities, and goals of the department.

Research statements can be weakened by:

- overly ambitious proposals

- lack of clear direction

- lack of big-picture focus

- inadequate attention to the needs and facilities of the department or position

Why a Research Statement?

- It conveys to search committees the pieces of your professional identity and charts the course of your scholarly journey.

- It communicates a sense that your research will follow logically from what you have done and that it will be different, important, and innovative.

- It gives a context for your research interests—Why does your research matter? The so what?

- It combines your achievements and current work with the proposal for upcoming research.

- areas of specialty and expertise

- potential to get funding

- academic strengths and abilities

- compatibility with the department or school

- ability to think and communicate like a serious scholar and/or scientist

Formatting of Research Statements

The goal of the research statement is to introduce yourself to a search committee, which will probably contain scientists both in and outside your field, and get them excited about your research. To encourage people to read it:

- make it one or two pages, three at most

- use informative section headings and subheadings

- use bullets

- use an easily readable font size

- make the margins a reasonable size

Organization of Research Statements

Think of the overarching theme guiding your main research subject area. Write an essay that lays out:

- The main theme(s) and why it is important and what specific skills you use to attack the problem.

- A few specific examples of problems you have already solved with success to build credibility and inform people outside your field about what you do.

- A discussion of the future direction of your research. This section should be really exciting to people both in and outside your field. Don’t sell yourself short; if you think your research could lead to answers for big important questions, say so!

- A final paragraph that gives a good overall impression of your research.

Writing Research Statements

- Avoid jargon. Make sure that you describe your research in language that many people outside your specific subject area can understand. Ask people both in and outside your field to read it before you send your application. A search committee won’t get excited about something they can’t understand.

- Write as clearly, concisely, and concretely as you can.

- Keep it at a summary level; give more detail in the job talk.

- Ask others to proofread it. Be sure there are no spelling errors.

- Convince the search committee not only that you are knowledgeable, but that you are the right person to carry out the research.

- Include information that sets you apart (e.g., publication in Science, Nature, or a prestigious journal in your field).

- What excites you about your research? Sound fresh.

- Include preliminary results and how to build on results.

- Point out how current faculty may become future partners.

- Acknowledge the work of others.

- Use language that shows you are an independent researcher.

- BUT focus on your research work, not yourself.

- Include potential funding partners and industrial collaborations. Be creative!

- Provide a summary of your research.

- Put in background material to give the context/relevance/significance of your research.

- List major findings, outcomes, and implications.

- Describe both current and planned (future) research.

- Communicate a sense that your research will follow logically from what you have done and that it will be unique, significant, and innovative (and easy to fund).

Describe Your Future Goals or Research Plans

- Major problem(s) you want to focus on in your research.

- The problem’s relevance and significance to the field.

- Your specific goals for the next three to five years, including potential impact and outcomes.

- If you know what a particular agency funds, you can name the agency and briefly outline a proposal.

- Give broad enough goals so that if one area doesn’t get funded, you can pursue other research goals and funding.

Identify Potential Funding Sources

- Almost every institution wants to know whether you’ll be able to get external funding for research.

- Try to provide some possible sources of funding for the research, such as NIH, NSF, foundations, private agencies.

- Mention past funding, if appropriate.

Be Realistic

There is a delicate balance between a realistic research statement where you promise to work on problems you really think you can solve and over-reaching or dabbling in too many subject areas. Select an over-arching theme for your research statement and leave miscellaneous ideas or projects out. Everyone knows that you will work on more than what you mention in this statement.

Consider Also Preparing a Longer Version

- A longer version (five–15 pages) can be brought to your interview. (Check with your advisor to see if this is necessary.)

- You may be asked to describe research plans and budget in detail at the campus interview. Be prepared.

- Include laboratory needs (how much budget you need for equipment, how many grad assistants, etc.) to start up the research.

Samples of Research Statements

To find sample research statements with content specific to your discipline, search on the internet for your discipline + “Research Statement.”

- University of Pennsylvania Sample Research Statement

- Advice on writing a Research Statement (Plan) from the journal Science

- Appointments

- Resume Reviews

- Undergraduates

- PhDs & Postdocs

- Faculty & Staff

- Prospective Students

- Online Students

- Career Champions

- I’m Exploring

- Architecture & Design

- Education & Academia

- Engineering

- Fashion, Retail & Consumer Products

- Fellowships & Gap Year

- Fine Arts, Performing Arts, & Music

- Government, Law & Public Policy

- Healthcare & Public Health

- International Relations & NGOs

- Life & Physical Sciences

- Marketing, Advertising & Public Relations

- Media, Journalism & Entertainment

- Non-Profits

- Pre-Health, Pre-Law and Pre-Grad

- Real Estate, Accounting, & Insurance

- Social Work & Human Services

- Sports & Hospitality

- Startups, Entrepreneurship & Freelancing

- Sustainability, Energy & Conservation

- Technology, Data & Analytics

- DACA and Undocumented Students

- First Generation and Low Income Students

- International Students

- LGBTQ+ Students

- Transfer Students

- Students of Color

- Students with Disabilities

- Explore Careers & Industries

- Make Connections & Network

- Search for a Job or Internship

- Write a Resume/CV

- Write a Cover Letter

- Engage with Employers

- Research Salaries & Negotiate Offers

- Find Funding

- Develop Professional and Leadership Skills

- Apply to Graduate School

- Apply to Health Professions School

- Apply to Law School

- Self-Assessment

- Experiences

- Post-Graduate

- Jobs & Internships

- Career Fairs

- For Employers

- Meet the Team

- Peer Career Advisors