Cookies on GOV.UK

We use some essential cookies to make this website work.

We’d like to set additional cookies to understand how you use GOV.UK, remember your settings and improve government services.

We also use cookies set by other sites to help us deliver content from their services.

You have accepted additional cookies. You can change your cookie settings at any time.

You have rejected additional cookies. You can change your cookie settings at any time.

Bring photo ID to vote Check what photo ID you'll need to vote in person in the General Election on 4 July.

Research and Development Communication Forum

An HMRC-sponsored forum, the Research and Development Communication Forum meets twice a year to discuss the operational delivery of the Research and Development (R&D) tax relief schemes.

Agents, professional bodies, delegates from the industry and the main business, technical and trade bodies, and representatives from HMRC who have policy and operational responsibilities for Research and Development ( R&D ) tax credits. Other HMRC representatives and representatives from other government departments.

Terms of reference

- the name of the committee shall be the Research and Development Communication Forum ( R&DCF )

- the committee shall be made up of (a) delegates from the industry and the main businesses technical and trade bodies, and (b) representatives from HMRC who have policy and operational responsibilities for R&D tax credits; other HMRC representatives and representatives from other government departments will attend as appropriate for discussion of relevant agenda items

- operational policy proposals and related operational issues

- issues arising on the implementation of prospective changes to legislation and practice

- operational aspects of existing policy and practice

- monitoring developments in the operation of the R&D tax relief schemes, considering their impact on companies of all sizes.

- sub-committees will be used as required to consider specific proposals and issues.

- the committee will be chaired by HMRC and organisations wishing to become members of the committee or to join the waiting list for membership should apply to the R&DCF chair. The R&DCF chairs’ decision on membership will be final

- each member body can send one delegate (plus any presenters from the same body) to each of the biannual meetings of the forum. If a member misses two consecutive meetings another body from the waiting list may be invited to replace them at future meetings.

- where there are spare seats at forum meetings firms and bodies on the waiting list will be invited to send a delegate to that meeting.

- members are expected to adhere to the HMRC standards for agents. Those in breach of the standards may have their membership rescinded by the R&DCF chair, whose decision on the matter will be final

- both the minutes of the committee and, where appropriate, the slides presented at the meetings shall be published on GOV.UK

Previous terms of reference

You can view the previous terms of reference (valid until 24 January 2019) from the R&DCF (formerly the Research and Development Consultative Committee) on The National Archives website .

Meeting minutes

Meetings are every 6 months.

Minutes - 15 December 2023

ODT , 45.4 KB

This file is in an OpenDocument format

Minutes - 15 December 2023 ( ODT , 45.4 KB )

Minutes - 26 July 2023 ( ODT , 27.1 KB )

Archived minutes

Minutes and documents form previous meetings are available on The National Archives website:

- 2022 minutes

- 2021 minutes

- 2020 minutes

- 2019 minutes

- 2017 to 2018 minutes

- 2013 to 2016 minutes

- 2005 to 2012 minutes

Contact details

Is this page useful?

- Yes this page is useful

- No this page is not useful

Help us improve GOV.UK

Don’t include personal or financial information like your National Insurance number or credit card details.

To help us improve GOV.UK, we’d like to know more about your visit today. Please fill in this survey (opens in a new tab) .

- Claim R&D Tax

- What is R&D

- R&D Tax Credits Explained

- RDEC & SME Accounting

- RDEC Scheme Explained

- Eligible Costs

- Agriculture

- Construction

- Food & Drink

- Water & Waste

- Information

- Finance & Insurance

- Pharmaceutical

- Meet our Team

- Client Stories

- Become a Partner

- Join our Team

- What Sets Us Apart

- Impact Beyond Business

- News & Insights

- Ask an Expert

Knowledge Base News and insights R&D tax credits

The Research & Development Communication Forum meeting: here’s what we learned

The Research & Development Communication Forum, or RDCF (formerly the Research and Development Consultative Committee, or RDCC), is an HMRC-sponsored forum that meets every six months to discuss the operational delivery of the UK’s R&D tax relief schemes.

The committee, which comprises HMRC agents, professional bodies, industry delegates and representatives of trade bodies, last met in December 2021 . As members of the RDCF forum, here are our key takeaways from that meeting.

Cloud computing costs will be eligible for relief

It’s been a long time coming but we’ve now learned more about HMRC’s changing approach to cloud computing and big data expenditure.

It was exciting back in Autumn 2021 to learn from HMRC that qualifying cost criteria for both the Research and Development Expenditure Credit (RDEC) and SME R&D relief schemes would be expanded to include cloud computing and big data costs.

In December’s forum, HM Treasury Policy Advisor Isaac Haigh asked to hear from companies to whom this would be relevant so that the government could ensure future legislation would be “fit for purpose”.

It seems these discussions led to greater clarity being provided, as we’ve now learned that some indirect uses of cloud computing, such as storage, will now be covered.

Data licensing was discussed too, and this could also be included in R&D relief applications as long as the claimant doesn’t maintain any rights to publish, share or otherwise communicate raw data within a dataset they’ve licensed for use in an R&D project.

A u-turn on overseas R&D work claims

Less welcome in November was HMRC’s proposal to stop businesses claiming R&D relief on the cost of R&D subcontractors based outside of the UK.

This, too, was discussed in the meeting, where HMRC representatives reiterated the intention to encourage activity in the UK, not outside of it, but claimed they were open to hearing about any “narrow exceptions” that could be accounted for.

Again, it seems this openness led to an amendment, as we’ve now learned of a u-turn in the decision and expenditure on overseas R&D work will remain eligible where there are:

- material factors such as geography, environment, population or other conditions that are not present in the UK and are required for the research – for example, deep-ocean research.

- regulatory or other legal requirements that activities must take place outside of the UK – for example, clinical trials.

HMRC’s position on subsidised expenditure

The recent high-profile tribunal case involving Quinn London Limited and HMRC highlighted several issues around the latter’s definition of subsidised expenditure.

To refresh your memory, HMRC initially rejected an R&D relief claim from Quinn on the grounds that its costs were subsidised. It argued that payments made by Quinn’s clients for its finished building works made the R&D expenditure ineligible.

At appeal, the First-Tier Tribunal (FTT) ruled in Quinn’s favour, saying it was entitled to £1 million in unpaid tax relief from HMRC.

We believed at the time that this was reassuring news for businesses who take on R&D projects on behalf of clients but also made it clear that the industry needed more clarity about what does and doesn’t qualify as a subsidised expenditure.

We were right to be hesitant.

While HMRC said in the RDCF meeting that it would not be appealing the FTT’s decision, it also made clear that its view of the legislation in question has not changed since at least 2004.

R&D technical advisor Sean Coneeny revealed HMRC’s standing to be that:

- FTT decisions are not binding, do not have precedent value and are made on the facts of each specific case.

- HMRC may have made an error in not challenging the claim earlier in the process

- HMRC will continue to challenge similar claims

Pre-notifying HMRC of planned R&D projects

As part of the reform announced in November, companies will need to inform HMRC in advance that they plan to make an R&D relief claim (as well as making the claim digitally and including more detail, such as the names of any advising agents, information on what expenditure the claim covers and the uncertainty overcome).

While we welcome any streamlining effect this will have, there were a few understandable concerns raised in the committee meeting.

In response, HMRC said that:

- It envisages prenotifications to be made before the end of the accounting period to which the R&D relief claim relates

- As they’re distinct notions, advance assurance and pre-notification can be completed separately, although an advance assurance (where it’s applicable) could be taken as pre-notification

- It (at the time of the meeting) was still considering how to implement the pre-notification measures and would work internally and with external stakeholders to ensure they worked as intended

For more information…

We specialise in helping businesses access the R&D relief they’re entitled to, working closely with HMRC to understand R&D tax legislation. This ensures all the claims we submit for clients are accurate, maximized and robust.

This RDCF event took place in December 2021 and in March, the government offered further information on changes to both relief schemes in its Spring Statement .

Watch our round-table discussion now to learn more about these updates and the potential impacts.

Can we help your business?

Arrange a free consultation with our team of experienced and approachable tax incentive advisers today. Our mission is to help innovative companies access millions of pounds of government money set aside for funding your innovation. Your business could be next.

Book a free consultation Read more insights

Dr Arwyn Evans

R&D Tax Manager

Related articles

Innovation and technology in uk politics: a breakdown of 2024 party manifestos.

- 18 Jun 2024

Understanding Subcontractor Guidance for R&D Tax Credits: 2024 Updates

- 29 Apr 2024

Enhanced R&D Intensive Support for Loss-making SMEs — Comprehensive Guide

Changes to R&D Tax Credits in April 2024: Impact on UK Businesses

- 26 Apr 2024

- 10 min read

Join our mailing list

Stay up-to-date with all the ways R&D tax relief can help your business grow

- Coronavirus Updates

- Education at MUSC

- Adult Patient Care

- Hollings Cancer Center

- Children's Health

Biomedical Research

- Research Education

- ORD-Hosted Seminars

Science Communication Forum

Research Development

Office of Research Development

173 Ashley Ave, MSC 502 Basic Science Bldg. 101 Charleston, SC 29425

Contact our team

Alan Alda Center for Communicating Science Overview

The Office of Vice President for Research in cooperation with the Office of Communications and Marketing hosted the Alan Alda Center for Communicating Science workshop. This Workshop allowed basic, translational, and clinical researchers to experience the Alda Method style of transformative communication. With funding from the South Carolina Clinical & Translational Institute (SCTR), the Office of Research Development, and Imagine 2020 funds, the 2019 Science Communication Forum was held August 7, 2019.

This interactive session introduced participants to general principles in how to craft short, clear, conversational statements, intelligible to non-scientists, about what they do and why it matters. The session consisted of an interactive presentation and discussion on interpreting technical material using examples and analogies to illuminate unfamiliar concepts to their audience. The plenary addressed problems and solutions in public interactions as well as peer-to-peer communication. Participants actively engaged in improvisation exercises and practiced clarity in speaking to non-scientists about their work. For more information visit the Alan Alda Center for Communicating Science: www.aldacenter.org.

Alda-Kavli Learning Center Online Learning for Scientists and Researchers

The Alda-Kavli Learning Center offers scientists and researchers a place to explore science communication through online learning experiences and webinars on a variety of topics. Learn more .

For more information, please contact Wanda Hutto Pierce at [email protected] .

Are you ready? HMRC’s Additional Information Form is now live

Research & Development Communication Forum Update

Author: Alex Hewitt | Published: th , 2021">December 14 th , 2021

Share this article

Last week, we attended HMRC’s R&D Communication Forum (RDCF, formerly the RDCC). As this came hot on the heels of the Government’s recent announcements on Research and Development, there was much to be discussed!

As we’ve recently written about in our R&D Consultation Outcome and Upcoming Changes blog , the proposals from the Treasury focus mainly on abuse of the system and how to ensure that UK companies are the true beneficiaries of the scheme.

With this in mind, from April 2023, claimants will be required to

- give advance notification of their intention to make a claim;

- submit all claims digitally;

- include details of any agents involved in compiling the claim;

- make sure the claim is signed off by an officer of the company.

This was discussed at length, and all seems quite logical, except when it comes to giving advance notice. Given that you may not be aware you have qualifying activities until you actually hit your first “technical uncertainty”, how this will work in practice is very much up in the air. HMRC spoke of a portal where claimants can notify their intention to claim, but this is very much in the planning stage. There will also be additional fields to complete in the CT600L, so watch this space.

The proposed rules around subcontractors and EPWs designed to ensure payments remain within the UK were also a hot topic. The current proposals are that from 2023, these costs must be incurred by UK PAYE staff. HMRC discussed the potential exceptions to the rule, for example when R&D absolutely needs to take place abroad for scientific reasons. We HMRC are still seeking responses to these proposed changes, so we expect further tweaks and clarification through 2022.

Talk then turned to new costs that can be included in a claim. There was some clarification of the inclusion of Cloud and Data costs. HMRC stated that not all costs will qualify – only those which can be attributed to data processing, software, computation and analytics. Quite how these specific costs can be identified and ring-fenced is up for debate. HMRC also announced that, due to the fact the Government’s new 1.25% Health and Social Care Levy will be collected by HMRC, these costs can also be included in the overall staff costs.

Finally, there was some good news from a processing perspective:

- YTD, 23,755 SME and 2,804 RDEC claims have been processed

- 91% of these were processed within 28 days, which is up from 88% on this time last year.

- Claims are currently being processed at day 24 for SME and day 43 for RDEC.

Given most HMRC are still working remotely, this is a decent churn rate.

Alex Hewitt

Never miss a beat. Get R&D tax scheme updates and guidance sent straight to your inbox!

How to write an r&d tax relief technical narrative.

With HMRC’s new mandatory requirement for project descriptions on all submissions, we wanted to share our experiences to help others to write their best possible technical narratives.

Available to download here.

Related Articles

Critical Differences: Pre-Notification vs Additional Info...

Published: April 30 th , 2024

Merged R&D scheme and enhanced R&D intensive su...

Published: April 04 th , 2024

A Guide to Proactive HMRC Disclosures for R&D Claims

Sarah Scala

Published: March 18 th , 2024

Get started - Book a demo and get a 30-day free trial!

Book a demo.

Complete the form and we’ll be in touch to arrange a time!

- Partnership

- Funding Finder

- R&D Tax Credits

- R&D Tax Calculator

- Eligibility

- HMRC Enquiry Support

- Online R&D Tax Portal

- Grant Funding

- Grant Claim Management

Other Services

- Video Games Tax Relief

- Capital Allowances

- EIS/SEIS Support

- CCL/EII Schemes

- Creative Tax Relief Schemes

- Meet The Team

- Our Expertise

- Latest News & Blogs

- Case Studies

- Knowledge Centre

- Merged R&D Scheme

- HMRC Insights

- Innovate UK Insights

- Focus on Innovate UK Smart Grants

- Industrial Strategy Challenge Fund

- The Innovation Challenge

- Partners and Pastries - Breakfast Networking

- The application process

- Prize package

08 Dec 2022

Hmrc r&d communication forum (rdcf).

Ian Davie Senior Consultant

HMRC R&D Communication Forum (RDCF)

The biannual meeting of the RDCF (Research & Development Communication Forum) occurred on 7th December, which is an opportunity for HMRC to communicate with R&D tax agent providers.

It also provides agents the chance to ask questions around policy, process, technical matters and changes to the SME and RDEC schemes.

With so much happening in the media, increased compliance checks, fraud prosecutions, parliamentary committee meetings and changes to the schemes’ rates in the budget, it was expected to be quite a lively meeting.

The biggest snippets of information we learned were around the intended future amalgamation of the SME and RDEC schemes, how to support the SME R&D intensive companies, and the new G-Forms for digital submission.

SME & RDEC into a single scheme

It was mentioned that there will likely be an announcement in Spring Budget 2023 of the intention to combine the SME and RDEC schemes and the combined rate into a single above the line type scheme later in 2023, which in style will be similar to the RDEC scheme as it is now.

Details of how it would operate were not discussed but they will be consulting industry on this. Sub-contracting will be of key interest in the combined scheme.

The intention for this was apparently in the Autumn statement 2022, but having traced back over past statements, it has not been mentioned.

SME R&D Intensive businesses

As part of the recent changes to the SME scheme which will take place in April 2023 are as follows:

- SME rate change from 130% to 86%

- SME cash in rate change from 14.5% to 10%

This will have a massive effect on the benefit that SME’s can claim on their eligible R&D spend. For SME R&D intensive businesses that are spending heavily on R&D and cashing in losses, the benefit will drop from 33% of spend to 19%.

A company spending £500k on R&D will now get back £93k instead of £167K. Though if they are accessing grants then the RDEC benefit increases by 50%.

There appears to be an intention to provide some additional support for these SME R&D intensive businesses, though no details were forthcoming, but this will not increase levels of R&D support spend overall.

Digital Portal and ‘G Forms’

HMRC were also going to present their proposed digital platform, which we learnt they have called ‘G Forms’, intended as a portal for R&D claims.

The plans are to have this up and running in 2023 with the ‘G Form’ intending to standardise the format for reporting R&D.

TBAT Innovation questions to HMRC

TBAT asked eight questions, of which four were raised in the meeting:

- R&D work that replicates others’ R&D that is not in the public domain? (Paragraph 21 in the BEIS guidelines).

A summary of the reply was that a company should be able to demonstrate even if another company has made the advance and not told anyone. You should be able to demonstrate that in your case and how your specific advance is still an advance in science and technology. This is a difficult area to demonstrate and talking to an R&D tax agent can help, as it is complicated.

- Processing times return to 28 days?

HMRC’s ambition is to return to 95% of claims processed in 28 days asap, but with the processing peak in December and reform changes due to land, the intention is to continue to hit 80% processed within 40 days in the short term. Remember if you are seeking a repayment, add two weeks on top of that for payment processing.

- How is R&D pre-registration meant to avoid fraud?

Pre-registration will provide HMRC with some information on claim, which could result in a “Are you sure?” letter. This will also stop agents encouraging claimants to make fraudulent claims going back two years.

- Will the revision of the ONS data have an impact on the R&D schemes?

ONS R&D data has always been less than HMRC R&D eligible costs.

ONS’s methods have not been changed since the 1980s; they have now revamped their process and their new estimates appear to align with HMRCs figures, though HMRCs figures do not include R&D in grants, capital expenditure, arts and social sciences, so still some significant differences between the two sets of data.

The expectation is that overall company R&D spend will increase from £37Bn in 2020/21 to £60Bn in 2027/28.

The presentations from HMRC did not tell us much other than what is in the public domain. Though we did pick up a few snippets of new information:

- All the proposed changes planned for April 2023 will be going ahead. Rates changes, cloud computing, data costs and mathematics added, foreign sub-contractor costs excluded, pre-registration of an R&D claim, senior company sign off of claim, notification of use of an R&D agent to prepare the claim are all going to happen. The rates changes will save £1.3Bn by 2027/28.

- The generous nature of the SME scheme encouraged fraudulent claims, and it is HMRC’s thinking that by reducing the benefit rates this will reduce fraud.

- HMRC are struggling to meet their SLA (Service Level Agreement) of processing claim in 28 days and are presently targeting 80% of claims processed in 40 days. Reviewing the SLA is an option being considered. They believe they are up to date with claims.

- HMRC have processed 24,000 SME and 3,000 RDEC claims to date since 1st April 2022.

- During December claims are expected to peak, so early filing recommended, with additional HMRC resources added to stay within the current 40-day target for 80% of claims.

- Make sure that technical reports on the R&D activity focus on the R&D and not the commercial aspects of the project.

- HMRC are planning an educational piece on R&D with letters out to companies plus some webinars on software due to launch in the next couple of months.

TBAT Thoughts

We await to see what the digital G Forms look like, and how a unified scheme, similar to the RDEC, will operate next year.

I still disagree with pre-registration as it stops genuine companies doing good R&D going back 2 years to make a claim. If there are some simple details of what the R&D is, then fraudsters will work out they can put down some great R&D projects to get round this step.

Fraud is the biggest issue facing HMRC and the reputation of the scheme. This will not be tackled by rates changes or pre-registration, only by HMRC correctly policing the scheme and dealing with the fraudsters.

With HMRC thinking they are up to date on processing claims in 40 days, TBAT have a number of clients that submitted in June or before where claims are yet to be processed, so we don’t think HMRC are up to date.

Related Articles

With new rules for contracted-out r&d, what does ‘contemplated’ mean.

When a project encounters uncertainty, a company often outsources part of the R&D work to a specialised firm. New rules for contracted-out R&D now require customers to show they 'intended' or 'contemplated' the necessary R&D. Our article explores this concept, and examines examples of what 'contemplated' means.

R&D Budgeting Strategies: Navigating Financial Challenges

Innovation is the cornerstone of progress in today's fast-paced world, and research and development (R&D) is the engine that propels it forward. Whether you are a start-up or an established enterprise, your ability to innovate often hinges on your R&D budgeting strategies.

An independent consultancy, highly skilled and experienced

Assists organisations in accessing research and development grant funding across a range of UK and EU schemes and industry sectors.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 21 October 2021

Co-creation in citizen social science: the research forum as a methodological foundation for communication and participation

- Stefan Thomas 1 ,

- David Scheller 1 &

- Susan Schröder 1

Humanities and Social Sciences Communications volume 8 , Article number: 244 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

3982 Accesses

18 Citations

6 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Science, technology and society

This paper addresses the emerging methodological debate about citizen social science from the perspective of participatory research methods. The paper introduces the research forum as a horizontal and safe communicative space moderated by academic researchers that enables co-researcher participation across all phases of co-creational research projects. It is argued that in co-creational citizen social science, such a communicative space requires conceptualisation in order for it to foster citizens’ engagement in the knowledge production that deals with their specific social lifeworlds. In the research forum, the potential that the social sciences bring to citizen science—methodological reflection and the theoretical interpretation and contextualisation of data—can flourish in a collaborative process. Based on the expertise in co-created research in multigenerational co-housing projects, the paper reflects on practical experiences with the research forum in terms of four central dimensions: (1) opening up spaces for social encounters; (2) establishing communicative practice; (3) initiating a process of social self-understanding; (4) engaging in (counter-)public discourses. Finally, the paper closes with a summary of potential and challenges that the research forum provides as a methodological foundation for co-creation in citizen social science projects.

Similar content being viewed by others

Determinants of behaviour and their efficacy as targets of behavioural change interventions

Participatory action research

Interviews in the social sciences

Introduction.

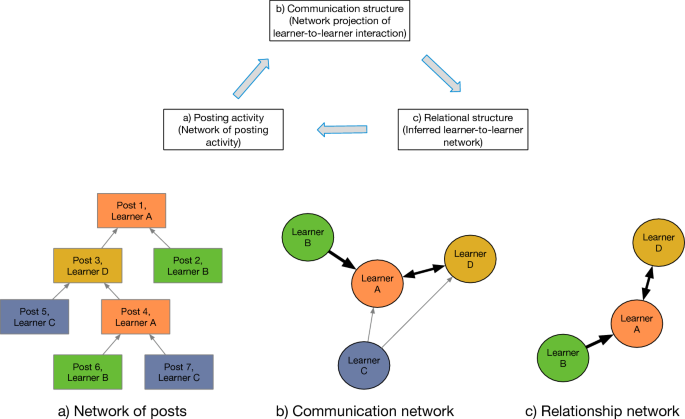

In recent years, the number of citizen science projects, and the public recognition of citizen science, has increased significantly (Sauermann et al., 2020 ). Citizen science has an over three-decade history, and has been primarily conducted in the natural sciences. In recent years, however, there has been an increase in discourses on the role of the social sciences in citizen science (Kullenberg and Kasperowski, 2016 ; Tauginienė et al., 2020 ; Pettibone and Ziegler, 2016 ). The emerging field of citizen social science brings together social science researchers who conduct citizen science projects (Dadich, 2014 ; Purdam, 2014 ; Kythreotis et al., 2019 ; Heiss and Matthes, 2017 ) and researchers with a background in citizen science who focus on social issues and thus apply and integrate social science methodologies and theories in research (Darch, 2017 ; Eitzel et al., 2017 ; Hecker et al., 2018 ; Mayer et al., 2021 ; Vohland et al., 2021 ). These two streams converge in considering the role of citizens’ social concerns as a central aspect that requires reflection on various degrees of participation and involvement of citizens as co-researchers (Eleta et al., 2019 ; Mayer et al., 2018 ; Bonhoure et al., 2019 ; Senabre et al., 2018 ). In the following, we use the term “co-researcher” for people that conduct research in a citizen science project—alone or together with academic researchers (Whyte, 1990 ) and the term “co-researcher communication” for mutual exchange between the project partners.

From the very beginning, citizen science has served as an umbrella term for a broad variety of approaches to citizen participation in research (Shirk et al., 2012 ; Phillips et al., 2019 ). Two perspectives on participation—a key concept in citizen science—have developed. The first perspective is especially concerned with the democratisation of science by renegotiating the relationship between science and technology, on the one hand, and society and the public, on the other, and by empowering participatory grassroots research (Irwin, 1995 ; Kasemir et al., 2003 ; Leshner, 2003 ; Powell and Collin, 2009 ; Ottinger, 2010 ). The second perspective adopts a rather top-down, scientist-led crowd science approach that aims to involve citizens in large numbers in the data collection and analysis (Bonney et al., 2009 ; Bonney et al., 2014 ; Franzoni and Sauermann, 2014 ). Notwithstanding this duality of approaches, citizen participation in science is a topic that has acquired new relevance in recent years because, as Maasen and Lieven ( 2006 ) noted, “a general shift is seen to be taking place from a legitimation through knowledge to a legitimation through participation ” (p. 400; emphasis in the original).

Papers that use the term “citizen social science” include a broad variety of levels of co-researcher participation and engagement ranging from data collection by citizen research volunteers about people begging in the streets of London (Purdam, 2014 ), through co-creational research on mental health issues together with affected people in Barcelona (Bonhoure et al., 2019 ), to accelerating climate action and awareness of climate policies through increased citizen engagement (Kythreotis et al., 2019 ). Various tools and approaches, for example, co-evaluation, are used to enhance the research outcomes (Mayer et al., 2021 ).

The inclusion of a multitude of perspectives by strengthening the discourse between (civil) society and science leads not only to an increase in knowledge production but also to a different type of knowledge that can contribute to finding more sustainable solutions for practical societal challenges and problems. In co-created research, citizens can draw up their own research agendas by pursuing research interests that they have defined and that are not always covered by academic disciplines and research paradigms (Hecker et al., 2018 ). This can improve self-determination and action potency through evidence-based knowledge that can be transformed into social practices to solve societal issues and problems. Co-creation-oriented citizen social science projects, in particular, emphasise the importance of face-to-face communication in “participatory meetings” (Senabre-Hidalgo et al., 2021 ). The authors stressed the potential of such communicative spaces facilitated by academic researchers for reflecting on ethical dimensions of research, such as the co-researchers’ and academic researchers’ hidden agendas. However, a methodological conceptualisation of these spaces remains rather implicit. Against this background, we argue that an explicit discussion of the foundational methodology that guides communication between project partners is of key importance in co-creational citizen social science projects. The communicative and discursive turn in social and political science seems to be promising to further elaborate on such a framework (Habermas, 1985 ; Kemmis and McTaggart, 2005 ). With social concerns of the co-researchers put at the centre of the research, we consider co-researcher communication essential for the co-creation process itself. Appropriate communication leads to ongoing exchange and reflection between all stakeholders of the research, for example regarding the research design (i.e., question, steps, aims), research ethics (i.e., informed consent, data protection, intellectual property) and practical effects on the co-researchers (i.e., community building, conflicts).

In the following, we are laying out a methodological framework of the research forum as an approach to co-creational citizen social science. First, by drawing on different theories, we provide a methodological conceptualisation of the research forum as an open, safe, inclusive, and horizontal space for co-researcher communication in all phases of the research. The characteristics, structure and aim of the research forum are described. In addition, we relate this conceptualisation of the research forum to crucial aspects of citizen social science for enabling co-creational research. Second, we introduce a co-created research project that we conducted with multigenerational co-housing projects. In a third step, we present four dimensions of the research forum and our conceptual reflections on their practical application in the co-housing projects to exemplify our methodological framework: opening up spaces, communicative practices, social self-understanding and (counter-)public discourses. In conclusion, we summarise our findings and point out the potentials and challenges of the research forum as a methodological foundation for co-creation in citizen social science projects that enhances both the impact of the knowledge produced and the democratisation of science.

The research forum: a methodological framework for co-creation

The debate is still ongoing about general characteristics of citizen social science as an umbrella term for various approaches from the environmental sciences and from social sciences and humanities (Albert et al., 2021 ; Kullenberg and Kasperowski, 2016 ; Tauginienė et al., 2020 ). In the following section, we present our conceptualisation of the research forum as a methodological framework for face-to-face communication between project partners. We then outline how this conceptualisation relates to four major aspects—participation, transdisciplinarity, impact, and reflexivity—that we consider crucial for co-creational citizen social science.

Conceptualisation

The term “forum” in early Latin means “a place out of doors”. The Roman Forum was the public communicative space for citizens and municipal institutions. It was an arena not only for important purposes such as religious practices, court trials, and political speeches, but also for everyday conversation, gossip and discussions among laypeople. The forum can be understood as a communication “marketplace” for exchanging perspectives and ideas that provided an opportunity for social participation. According to Jürgen Habermas ( 1996 ), the public sphere is constituted through communicative exchange of private perspectives in which public opinions on issues of general interest develop and progress. Despite many exclusionary aspects regarding social status or gender, these early forms of citizen participation in ancient cities eventually led to new forms of democratic self-governance and decision-making. The convergence of private and public opinions via communication has similarities with the scientific aspiration to arrive at generalisable findings.

The research forum is conceptualised as a series of workshops explicitly dedicated to fostering co-creation, co-design and transdisciplinarity across all phases of research—from defining relevant research topics and planning the research, through data collection and data analysis and interpretation, to presentation and evaluation of results. The research forum has a modular structure that takes account of the actual needs of the project in terms of session frequency, focus, format and length. Rules of communication are of crucial importance as an ethical foundation for an appreciative exchange on equal terms between the different project partners. The academic researchers take particular responsibility for ensuring an inclusive and safe environment through moderation and facilitation. The research forum provides the methodological framework for co-designing and applying all kinds of qualitative and quantitative methods, for example, focus groups, photovoice, multilog writing and surveys. In these sessions the general research topic is broken down, reformulated in a set of research questions and transformed into methodical steps for seeking new insights and results. The research forum ensures a collaborative discussion and planning process, so that all research participants can have their say, bring up their perspectives on the topic and be part of the decision-making process regarding research design and methods. By including the perspectives of citizens and civil society, organisations can acquire new insights for developing evidence-based practices.

The research forum sessions are typically structured in accordance with the phases of research. In the first phase , the research forum opens up a space in which co-researcher who share a social concern ideally come together in a “knowledge coalition” to define a research topic. Bonhoure et al. ( 2019 ) define a knowledge coalition as “a group including a diversity of relevant actors with diverse experiences and expertise, built to produce socially robust knowledge” (p. 13). The intention of the research forum as a “place out of doors” is that everyone who feels entitled and can contribute to examining the research topic is invited to participate. The second phase is dedicated to conducting research by discussing the different perspectives, collecting data and arriving at generalisable findings, and envisioning evolving social practices. In the third phase , the focus is on a closing discussion in which the results are summarised and the collaborative research process is reflected upon. In a retrospective process evaluation, the academic researchers ask for feedback on and an individual assessment of the progress in acquiring knowledge, deeper self-understanding and improvements of social practices. Throughout these phases, the research forum directly serves the aims of citizen social science by fostering: (A) co-creation and co-design of the research process through participation ; (B) reflexivity in the planning and realisation process; (C) continuous transdisciplinary exchange, inclusion, transparency and openness; and (D) meaningful and relevant research results with potential for social impact . Participation is addressing the level of engagement of co-researchers, transdisciplinarity focuses on the diversity of stakeholders and their interests, reflexivity is an essential tool for addressing power-relations, and impact focuses on the actual research outcomes.

Participation

Bonney et al. ( 2009 , p. 17; see also Shirk et al., 2012 ) distinguished between three models for public participation in scientific research, which differ according to the extent to which citizens are involved in steps in the research process: (1) contributory projects, where citizen participation is largely limited to contributing to data collection and recording; (2) collaborative projects, where the involvement of non-scientists also includes data analysis and, possibly, interpretation; (3) co-created projects, where citizen participants are actively involved in most or all steps in the scientific process. In the first two types of participation—contributory and collaborative—citizen scientists are involved merely as research assistants who do not have much say in the planning of the research process. By contrast, co-creation means that citizens participate collaboratively in the decisions regarding the research process (Powell and Colin, 2009 ). This participatory model could be extended with a fourth category. Whereas Haklay et al. proposed the term “extreme citizen science” ( 2018 ) for collaborative, bottom-up research practices, we prefer the term “citizen-led projects”, where members of the public assume control and power over the design of the project and thus “take ownership of the research” (Russo, 2012 , para. 36). This corresponds to what Sherry Arnstein ( 1969 ) called “citizen control as the highest rung on the ladder of citizen participation”. It entails a reversal of roles between citizens and experts (Bergold and Thomas, 2012 ; Sense, 2006 ). In such projects, it is not the academic researchers who set the research agenda, but rather it is the citizens who initiate and carry out the project and who involve the academic researchers more as enablers and advisers (Evans and Jones, 2004 ).

As pointed out above, citizen social science regularly aims at addressing urgent social issues through co-creation and co-design—as driving principles throughout the entire research project. Research is linked by co-creational formats to experiences and interests of citizens as specialised experts in social concerns, i.e., support for people with mental health issues or with disabilities (Albert et al., 2021 , p. 123–124). Co-decision-making begins at the project-design stage, when the research topic and research questions are defined (Bonhoure et al., 2019 ). It continues throughout the collection, analysis and interpretation of data, and concludes with the presentation of the results. We propose the research forum as a methodological approach that can provide a horizontal, inclusive and safe “communicative space” for different stakeholders in a knowledge coalition. As such, the research forum enables co-creational participation in transdisciplinary scientific knowledge production and deliberation across all phases of research. Co-creation is not only based on ethical considerations but also aims to achieve a different kind of knowledge that is practice-situated, sustainable and socially robust (Franzen and Hilbrich, 2015 , p. 28) and can be connected to public debates in society (Hecker et al., 2018 ). By “socially robust knowledge” (Nowotny, 2003 ) we understand knowledge that is meaningful for the actual lifeworld of particular communities because it connects specific “situated knowledges” (Haraway, 1988 ).

Transdisciplinarity

Citizen social science can be characterised as a transdisciplinary science (Fam et al., 2018 ; Defila and Di Giulio, 2018 ). Whereas interdisciplinarity presupposes the dismantling of the traditional boundaries between scientific disciplines in favour of an open and multiperspectival view of the research object, transdisciplinarity goes one step further by also involving other social fields from outside the sciences. The concept “transdisciplinarity” refers to different backgrounds, perspectives and agendas of the academic researchers and the co-researchers, which require ongoing reflection (Pettibone et al., 2018 ). Co-researchers in citizen social science projects have their own perspectives and interests regarding the research topic. As a consequence, they have their own say when it comes to topics such as the sustainable development of cities and neighbourhoods, gender equality, youth employment or mental health issues. The reason for this is that the object of research cannot be separated from the genuine life interests and practices of the co-researchers. At the same time science methodologies and theories can complement community skills and knowledge (Fortmann, 2009 ). When researching and acting in the social lifeworld coincide, the perspectives of those involved in the research cannot be omitted. With “social lifeworld”, we refer–following Alfred Schutz and Thomas Luckmann, ( 1973 )—to a concept that highlights the meaning structure inherent in culture and language, which actors create and use to orient themselves towards the social world (Habermas, 1987 ). If the knowledge to be produced is to have direct and worthwhile consequences for the shaping of the lifeworld and society, it is not enough for actors to simply join in. Science intervenes as a matter of course in political spheres of the lifeworld. Therefore, a transdisciplinary orientation of citizen social science connects with more general discourses on political participation in democratic societies (Thomas, 2021a ; Scheller, 2019 ). However, transdisciplinarity alone does not guarantee the production of socially robust knowledge (Maasen and Lieven, 2006 , p. 401). Rather, as pointed out in the section above, ongoing reflection on adequate levels of participation is required.

Reflexivity

Our conception of the research forum refers to Kemmis and McTaggart’s “communicative space“ ( 2005 , p. 563) as a central element of participatory action research (PAR). Academic researchers and co-researchers plan and discuss their research collaboratively. Deeper and intersubjective understanding of the research object is reached especially by talking, by everyone being able to put their views up for discussion, and by everyone being able to be heard. The overarching aim of the research forum is to achieve a convergence of the different perspectives of all participants in a shared reflection and interpretation of their common reality during the research process. This includes discussing the positionalities, authority, verbalisation skills, expertise and values of the researchers and co-researchers in the joint project (Call-Cummings and Ross, 2019 ; Bergold and Thomas, 2012 ). The core of participatory research is constituted not by individual research methods but rather by a certain attitude to incorporating the views and experiences of citizens regarding their own lifeworlds as an inherent part of the research process (Bergold and Thomas, 2020 ). This does not mean that the whole research process is conducted in a mode of full and deep participation. For pragmatic reasons alone, the academic researchers should be realistic about the amount of time that citizen researchers can devote to scientific endeavours. Nevertheless, the research forum provides the space to discuss with the co-researchers whether and how participation could be intensified. Moreover, the research forum brings to the fore the rich repertoire of social science theories and methodologies that enable the reflection and deconstruction of social reality and its underlying power relations, hierarchies and dichotomies (Thomas, 2021b ).

Citizen social science is not focused solely on theory building and scientific impact but also on the social—and even political—impact on the social lifeworlds of the co-researchers. From our perspective, co-creational citizen social science pursues two aims: first, to integrate lifeworld knowledge into science at all stages of the research process in order to increase scientific knowledge production (Franzen and Hilbrich, 2015 ); second, to enable co-researchers to achieve findings based on scientific methodologies and theories that are relevant for their everyday life contexts. As intended by applied research, sustainable solutions for practical societal challenges and problems can be created by taking up and deepening knowledge from practice (Aldridge, 2014 ; Dickinson and Bonney, 2012 ). “Sustainable” means here that the research-based findings are directly connectable to the meaning, interest and practice structures of the field rather than being thought through by scientists in their academic “ivory towers” without taking adequate account of the logics of the social field—a phenomenon that has been termed “scholastic bias” (Bourdieu, 2000 ). In the best case, a productive symbiosis arises from a two-sided expansion of knowledge: the expansion of the stock of everyday knowledge and of the archive of social science knowledge. Hence, a convergence of the perspectives of academic researchers and co-researchers does not necessarily mean that scientific standards are trivialised. Rather, as a temporary symbiosis of two perspectives, this collaborative research can meet the needs of both sides: the co-researchers’ need for practice-relevant forms of knowledge corresponding with local contexts, and the academic researchers’ need for generalised insights and findings (Bergold and Thomas, 2020 ; Maasen and Lieven, 2006 ).

Multigenerational co-housing projects: the research forum in practice

In order to illustrate the practical implementation of the research forum, we provide in what follows background information on a co-created research project that we conducted with three self-organised multigenerational co-housing projects. Three central (research) questions were addressed in the research: How can multigenerational co-housing projects be described as a community beyond traditional bonds such as family, neighbourhood or ethnicity? What community-building processes are characteristic of multigenerational co-housing projects? How can the democratic self-governance of co-housing projects be described? The aim of our research was to extend both the scientific and practical knowledge about how community-building and self-organisation works and can be extended in multigenerational co-housing projects. In the research forum, we wanted to acquire a better understanding of how solidarity and social bonds in co-housing projects work and can be improved.

In this section, we use the term co-researchers for the members of the of self-managed, collectively owned co-housing projects we worked with, and academic researchers or facilitators/moderators to describe ourselves. Besides the organisation of their community life, the groups were characterised by active social exchanges among the various generations: children, adolescents, adults and seniors. The social background of the co-researchers was quite homogeneous because most project members were university graduates and worked in academic jobs—mainly in professions in the social field, such as social worker, teacher or counsellor (Schröder and Scheller, 2017 ).

For each of the three multigenerational co-housing projects, we organised a series of six joint research workshops over a period of one year. In these 18 sessions, we collaborated with 50 co-housing residents directly and, through wider peer-to-peer methods, with 160 residents in total. The research forum series were structured as follows: first, definition of research topics by the co-researchers; second, conducting of research; third, presentation of research results and final evaluation. Each of the research forum sessions had a thematic focus that was drawn from the pool of topics collected in the first session.

We academic researchers took on the task of substantively and methodologically preparing the respective research forum sessions; in some cases, joint preliminary discussions took place with individual project participants. A wide range of low-threshold, creative methods were selected to activate the participants’ knowledge and experiences and to reduce barriers to communication by means of work materials that co-researchers produced during the workshop (e.g., posters and photos) and role play as an experimental reflection tool for different standpoints. As experiences and perspectives could also be incorporated in a non-verbal way, this approach facilitated multifaceted participation in the research process that went beyond “just talking”. At the end of each session, the co-researchers were usually given “homework”—for example, to conduct biographical interviews—which was to be discussed at the next session. Besides enabling the co-researchers to learn low-threshold research methods, this homework served to involve the residents who had not been able to attend the session in the data collection.

A typical research forum workshop proceeds in six steps: First, we open with a warm-up and a question round about how people are doing; then we present the programme for the day. Each session has a thematic focus that is jointly decided at the previous session. This is followed, second, by the joint evaluation of the “homework” carried out between the sessions. By discussing the community topics and explaining the different perspectives and positions in the house community, shared interpretations of situations emerge. There follows, third, a substantive block on the respective session topic. With the help of various methods, we gather the different views on the topic—for example, strategies for dealing with conflicts. This is usually followed, fourth, by a long mid-day break during which we have lunch together and time for informal conversations. Fifth, in the afternoon, visions about the further development of the project and initial ideas about concrete implementation steps, actions and methods are formulated. Moreover finally, sixth, in the closing plenary session, the process and content of the workshop are summarised. In addition, the topic and the tasks for the following session are discussed, and we ask the co-researchers for substantive and methodological feedback. The entire session is audio-recorded. Quotes given below are excerpts from transcripts of these audio-recordings. In addition, to document the group process and the work materials, videos are recorded and photos taken.

A huge variety of topics were brought up at these workshops, mostly by the members of the co-housing projects. Recurring topics in all three co-housing projects were decision-making and the handling of conflicts within the group. Closely related to the latter topic were explicit and informal rules that guide the everyday life and the interactions in the community. The project members wanted to use the research forum to clarify their visions for the future, to plan new projects for the community and to develop ideas for political interventions in their neighbourhoods and municipality. The relationship and tensions between the individuals and the community were also reflected upon. The project members discussed their needs for private spaces and their interest in joint activities with the whole group, such as summer festivals, group excursions, weekend events, cooking and leisure time activities.

Four dimensions of co-researcher communication

This section presents our methodological framework of working with the research forum as a key tool for participatory communication, including reflections offered by co-researchers during various methodological feedback rounds throughout the research process. As a result of the methodological conceptualisation of our practical experiences with the research forum as a foundation for co-creation, four key dimensions of co-researcher communication emerged: (1) opening up spaces for social encounters, (2) establishing communicative practices, (3) initiating a process of social self-understanding, and (4) engaging in (counter-)public discourses. From our perspective, these four dimensions resonate with the four crucial aspects of citizen social science discussed above—participation, transdisciplinarity, reflexivity and impact.

The four dimensions derive from the debate on interpretive social science. Habermas shows in “Facts and Norms” how the goal of social understanding among citizens is the driving force of debates on societal problems and issues in the public sphere ( 1996 , pp. 364–366). Nancy Fraser objects that there is not only the public sphere but manyfold of public spheres, which enable less privileged and less powerful citizens getting the opportunity to “find the right voice or words to express their thoughts” ( 1990 , p. 66). In both cases, social self-understanding regarding social situations is a result of citizens debating problems and concerns of common interest. The research forum provides such a “small“ public sphere in which participants exchange their views, interrelate their perspectives, and come to agreeable and generalisable definitions of their common situation. Kemmis and McTaggart ( 2005 ) implemented this communicative and discursive turn in participatory research methods and conceptualised the research forum as a communicative space for promoting collaborative research with co-researchers. We found that the research forum with its ongoing face-to-face communication fosters co-creational research in citizen social science. In our research, it functioned as such a communicative “place out of doors” for co-creatively negotiating topics of general interest in a participatory way.

Opening up spaces for social encounters

The first task of the research forum is to organise a knowledge coalition to open up a safe space for collaborative research in which a relationship of trust can be developed among all participants (Dentith et al., 2012 ; Borg et al., 2012 ). A safe space should not only allow openness, protected communication and mutual respect, but also the expression of different opinions and the articulation of conflicts (Bergold and Thomas, 2012 ). As the authors stated: “It is not a question of creating a conflict-free space, but rather of ensuring that the conflicts that are revealed can be jointly discussed; that they can either be solved or, at least, accepted as different positions; and that a certain level of conflict tolerance is achieved” (§13). A steady negotiation process takes place for building mutual trust. Three communication issues must be accordingly addressed and solved in the research forum: “emotional issues,” “task issues,” and “organisational issues” (Wicks and Reason, 2009 , pp. 249–250).

As moderators, we observed the appearance of all three “communication issues” in the research forum. As soon as we became aware that these issues had developed and had become a (latent) topic, we tried to open up a space for a meta-discussion. Further approaches to cope with these issues were that we started each session with a “check-in round” to get into a conversation about emotional attitudes towards that session. We also discussed emotional tensions or hostilities as soon as we became aware of them. Moreover finally, we tried to distribute responsibilities and tasks equally among all participants.

Above all, the research forum aims to provide a space for deliberations that enables the members of the knowledge coalition to take a step back from their everyday lives, from the unquestioned givenness of the social lifeworld from taken-for-granted commonsense interpretations (Schutz and Luckmann, 1973 , p. 3), and from routine practices. During the five-hour sessions, the co-researchers were invited to decentre their everyday interpretations in order to get into a mode of open reflection on their community practices. Instead of gaining new insights driven by pragmatic motives of everyday life for more or less immediate action plans (Berger and Luckmann, 1966 ), scientific methods offer a different approach. The scientific attitude is more about first taking a step back to obtain an overview of the multifaceted complexity of the research topic, and then probing deeper by means of systematic data collection and analyses. While a scientific examination may take years, what is needed in everyday life contexts is a faster clarification of and answer to the questions: “What is at issue here?’ and ‘What is to be done?”. In this way, the co-researchers can develop a new perspective by examining from a distance their everyday practices, thereby gaining both new and—as a result of joint discussions—shared interpretations of their situation.

One of the multigenerational co-housing projects did not have a communal space in the house. To enable the co-researchers from this project to get into a more distanced, explorative and reflexive mode we invited them to our university for the one-day sessions. This gave them an opportunity to step out of the familiar contexts of their community life, which were already interpreted by pre-set meanings, discourses and practices.

Despite our aspiration to open up spaces for social encounters, it was not possible to convince all the residents to participate directly in the collaborative research. The residents who were most active in the research forum were those who were interested in strengthening community and togetherness, and changing the discussion culture. For the most part, the residents who stayed away did so because they rejected the format of “just talking”. They had frequently advocated doing practical things instead, such as renovating the house. Moreover, there were different interest factions in the house groups, and we were invited mostly by the faction that wanted to strengthen the community and the discussion culture. This means that by discussing community topics they simultaneously increased their influence in their house project. Opening up spaces must therefore also include critical reflection on, and the potential overcoming of, power structures (Bergold and Thomas, 2012 ), so that all relevant perspectives can be incorporated into the development of joint, co-created knowledge.

By applying mostly low-threshold methods, we co-designed the research as inclusively as possible for all age groups. In one project, some seniors were unable to participate in the meetings at the university—be it for health reasons or because of scheduling difficulties or personal reservations. Therefore, we arranged an informal meeting with a “seniors’ café interview” at their house. Over coffee, cake, and liqueurs, we spent an afternoon with them to talk about community practices and intergenerationality. We brought the transcripts of the interview to the next research forum session to incorporate the absent voices into the research process. To involve children and adolescents in the research forum, we adopted a rather activity-related and play-based approach (Groundwater-Smith et al., 2015 ). For example, in one method—“visionary thinking”—a story was read out about children who had been allowed to take over and redesign an abandoned house. The children in the co-housing project—aged between 6 and 13 years—could then draw their dream houses and discuss their visions. In another method—“opposites day”—the children discussed how they would live together if they were adults, and the adults reflected on how they would organise the house community if they were children.

“House interviews” were a further method to open up spaces for discussion among all age groups. The residents drafted interview topics and semi-structured interview guides for focused peer-interviews, which they then conducted themselves. In accordance with the principle of co-creation in participatory research, the idea was that the co-researchers should not only collect the data but also choose the topics to be addressed in the interviews. The interview questions were formulated by the residents based on the knowledge, interests, and relevancies of their project. The transcripts of these interviews—and of the workshops—were then fed back into the research forum for the purpose of joint interpretation and analysis. This advanced the substantive development of a common understanding of the research object within the knowledge coalition. Thus, the role of the academic researchers consisted also in contributing to the scientific qualification of the co-researchers by providing inputs on theories and methods.

In summary, the first step of the research forum—opening up a communicative space—was realised through different approaches. Following the idea of a “place out of doors” to achieve a high degree of openness, we applied the following methods: a broad invitation of participants, initiating meta-discussions and check-in rounds, decentring commonsense interpretations and subjective perspectives, stepping out of everyday contexts, and reflections on power imbalances. There is not just one recipe for realising open spaces built on mutual trust. Adequate methods have to be invented for each research project regarding its specific context.

Establishing communicative practices

In addition to opening up spaces, a successful knowledge coalition also presupposes a culture of dialogue and discussion, and, above all, “communicative spaces” (Wicks and Reason, 2009 ; Kemmis, 2008 , p. 135) or “dialogic spaces” (Rowell et al., 2017 ). Communication across different perspectives aspires to eventually arrive at a shared interpretation of a particular topic. This does not necessarily mean unanimity but rather transparency. The acknowledgement of the wide variety of viewpoints in the room should ideally converge in a broad and inclusive definition of a topic. As Cook ( 2012 ) noted: “If authentic involvement is to take place, considerable time and effort needs to be allocated during the research process to “just talking”. … Talking was fundamental to moving beyond general conceptualisations of practice to deeper understandings” (para. 32). A “just talking” approach should be combined with other methodological instruments (e.g., writing, painting, drawing, playing games, drama) that enable the co-researchers to creatively take a step back from their everyday lives and to express their perspectives on the research topic.

Keeping the communicative spaces open was made more difficult by the fact that, because of the different social statuses and communication skills of the members of the house groups, there were always some residents who found it easier to turn their positions into group consensus. Other people—especially residents already in a marginal position within the group—found it considerably harder to make their perspectives heard. Moreover, personal conflicts between residents may have been a barrier for some to engage in the research forum, and these conflicts sometimes erupted in the sessions. Here, the set of communication rules proved fundamental in preventing the sessions from turning into an arena for personal conflicts. Furthermore, creating maximum transparency about topics and results of the research forum for all residents helped us to avoid getting caught up in the politics of the co-housing projects. Therefore, all materials produced in the sessions were made available to all residents, also to those who had not been present. The research methods expanded the communication space beyond the actual sessions by inviting all residents to contribute to the data collection, for example, through peer-interviews, surveys and feedback rounds.

As already pointed out, a self-reflexive moderation of the sessions was important for keeping the communicative space open. Moderation is a two-edged sword: it is an instrument of domination and an opportunity for equalising inequalities and levelling power hierarchies. Asymmetry between the positions of the various speakers is a starting premise of the research forum. In particular, those speakers who have good speaking skills, a high ability to articulate themselves, and previous experience of communicative group processes may exert a strong influence on the consensus-finding process. One thing that was especially problematised by the co-researchers with regard to power processes and hierarchies was the talk-heavy format. As one participant put it:

And I believe that it is the discussion format, and it is also an academic format, where Person A is quite steady in the saddle and can also express himself quite well. And Person B is a completely different type. He would be quite out of his depth here, or he would be worried that he was going to be out of his depth. (Participant in Workshop 2, Co-Housing Project A, 2016; translated from German)

Our main strategy for countering domination and the exclusion of perspectives in the research forum was to have a strong forum moderator who paid attention to turn-taking and, if necessary, intervened when substantive disagreements and conflicts arose among the residents. Although it was not possible for the moderators to take a neutral stance because of their own research interests, they took a position outside the heterogeneous interests in the co-housing project. As outsiders, we found it easier to maintain an overview and to ensure that all perspectives could be articulated. However, the disadvantage was that hierarchies between academic researchers and co-researchers may have been consolidated. As a basic strategy to avoid pitfalls such as pushing selective topics that are relevant only from the academic researchers’ point of view, the moderators obtained a mandate from all those present, and renewed it again and again. At the end of each workshop the moderators asked the co-researchers about their priorities for the upcoming sessions to ensure the relevance of the proposed topics. Moreover, they endeavoured to achieve a good balance between keeping their decisions explicit and discussable and ensuring that work progressed in a focused way.

Consequently, the research forum is an ongoing attempt of opening doors to each other’s contribution by establishing a space for communication and dialogue. It is important to consider different communication skills, the implementation of shared communication rules, a high degree of transparency, and a self-reflexive moderation that enables mutual decision-making.

Initiating a process of social self-understanding

Another central aspect of the research forum that corresponds with participatory social research is the initiation of a process of social self-understanding via social exchange and communication (Thomas, 2021a ). Members of the knowledge coalition share their perspectives in the “communicative marketplace” of the forum, in order to develop generalisable definitions of situations and define issues of shared interest to be further progressed throughout the research process. The research forum thus provides a space for group discussion that becomes the central instrument for the collection and interpretation of data. In contrast to group discussions, the research forum is not a “one-off encounter” of communicative exchange, but aims at initiating a discourse of social self-understanding in the various sessions.

With the concept of social self-understanding, we want to conceptualise the central aim of the communication about the research topic between all participants in the research forum. It starts with the everyday life interpretations of the co-researchers, in which they already apprehend their situation and their practices. We use these first-order interpretations (Schutz, 1973 ) to initiate a process of deeper self-understanding of what is already established as lived reality. Community, gender, age and the housing project do not exist as predefined realities but rather as sociocultural meanings that are the result of negotiation in contextualised social practices. We use the term self-understanding in the way that Giddens introduced it into social science discourse in the UK. Drawing on the German discussion on hermeneutics and interpretation (Habermas, 1985 ), Giddens ( 1976 ) wrote: “Hermeneutics, on the other hand, is directed to understanding the participation of actors in an intersubjective “form of life” and hence to an interest in improving human communication or self-understanding” (p. 60). Self-understanding aims therefore at emancipation from forces that are present and effective in situations but are not comprehended by the actors (Habermas, 1985 ). With the prefix “social”, we want to stress that self-understanding is not achieved in workshops by individual reflections or psycho-therapeutic processes, but rather by relating experiences and perspectives to each other in mutual communicative exchange.

The challenge of initiating a discourse of social self-understanding consists in creating a forum in which the subjective experiences of reality do not remain unmediated and external to each other. What can count as a community, what should be achieved in that community, and how the community and daily life in the co-housing project can be organised are questions that presuppose mutual understanding and agreement among the project members. Through dialogue and discussion, the participants should be able not only to communicate but to transcend the boundaries of their subjective attitudes and together in shared definitions of their reality. It is a question of developing a generalisable viewpoint in which the differences and divergences between the subjective perspectives can be grasped. Scientific methods contribute to overcoming the particularity of individual perspectives and achieving generalisable knowledge. By slowing down the pace, a productive discussion can succeed. This proceeds in a process of mutual translation that takes the subjective perspectives and interpretations as a starting point and transforms them into generalised knowledge. Social self-understanding is therefore both about articulating individual points of view and engaging in consensual discussions to create “collective knowledge” in which the individual contributions are integrated and reflected at the same time (Ansell et al., 2012 , p. 175).

Community-building practices were one of the central topics in our research project. The first step was that everyone was given an opportunity to express their individual perspectives on topics such as: What is a community? What kind of community should be realised in the co-housing project? How much community is desirable? The next step was to synthesise a mutual understanding of the community in consensus among the residents. Aspects addressed included the structure of house meetings; the way decisions are to be made; and ideas on the general mission of multigenerational co-housing projects, such as environmental sustainability, the revitalisation of rural villages, non-violent communication, etc. Finally, not only did everyone have to agree in general to this common definition of community, they should also have been able to have their concrete visions for practical action plans included in it.

In these various reflection steps, every member of the knowledge coalition gets a better understanding of their own ideas by interrelating the particularity of their individual perspectives to an emerging consensual definition. Social self-understanding is reached when a generalisable definition of the current situation and mission of the group has been developed. Instead of all co-researchers maintaining their individual points of view, social self-understanding aims to develop a common definition of what can be considered to be the shared social reality of the research group. From our perspective, this is precisely what the research forum would provide for citizen social science: collaborative work on common interpretations of reality, and options for action that encompass both the particularity of the individuals’ own standpoints and a generalisable finding regarding social reality.

Scientific methods constitute tools for decentring the particularities of individual perspectives and achieving generalisable research results. The main difficulty that the residents faced when researching their own house communities was to temporarily suspend their personal positions and opinions. Clearly, community and intergenerationality were not neutral topics in the co-housing projects but always included a normative dimension. Negotiations in the research forum were also always a matter of internal politics because collective decisions in the co-housing projects are driven by mutually shared interpretations and definitions of situations. Especially in the case of controversial topics—such as different forms and levels of engagement in the community—there was always a struggle to find the “right” interpretation of the situation. For co-researchers, the possibility arose that their own positions and interests in the co-housing community would be strengthened or weakened by the “right” or “wrong” definition achieved in the research forum. The research forum can develop its qualities to full potential if the communicative situation is kept open until the divergent positions and perspectives have been mediated to such an extent that the perspectives of all participants have been taken into account in a consensual definition—or at least a mutual understanding of the particular differences has been reached.

We see community-building as an intrinsic part of citizen social science (Albert et al., 2021 , p. 127). The extent to which the research forum contributed to community-building among the residents of the multigenerational co-housing projects depended on how successful we were in involving those who did not attend the workshop sessions. In principle, we found that those who attended gained a knowledge advantage over those who did not participate—despite the “homework” and the sharing of generated data and materials. Against this background, our inclusion strategy failed due to the fact that, when it came to gaining mutual understanding and agreement, there was no substitute for actual participation in a five-hour session. As one co-researcher put it:

I suddenly had the feeling that there was a rift between those who were there and those who weren’t. A process had taken place. And it was perceived by those who were there as important, somehow. And we can’t seem to manage to convey the insights that we gained there to the others. (Participant in Workshop 2, Co-Housing Project A, 2016; translated from German)