- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

When Trust Is Easily Broken, and When It’s Not

- Michael Haselhuhn,

- Maurice Schweitzer,

- Laura Kray,

- Jessica A. Kennedy

It depends on two very different mindsets.

“I cannot forget the follies and vices of others so soon as I ought, nor their offences against myself,” Mr. Darcy tells Elizabeth Bennet in a pivotal moment in Pride and Prejudice , before famously admitting: “My good opinion once lost is lost for ever.”

- MH Michael Haselhuhn is an Assistant Professor of Management and the A. Gary Anderson Distinguished Faculty Scholar at the University of California Riverside School of Business Administration.

- Maurice Schweitzer is the Cecilia Yen Koo Professor at the Wharton School and co-author of Friend & Foe . His research interests include negotiations, emotions, and deception.

- LK Laura Kray is a professor and the Warren E. and Carol Spieker Chair in Leadership at the Haas School of Business at the University of California Berkeley.

- Jessica A. Kennedy , PhD, is an associate professor of management at Vanderbilt University’s Owen Graduate School of Management. Her research explores issues of gender and ethics in the workplace.

Partner Center

America Is Having a Moral Convulsion

Levels of trust in this country—in our institutions, in our politics, and in one another—are in precipitous decline. And when social trust collapses, nations fail. Can we get it back before it’s too late?

American history is driven by periodic moments of moral convulsion. The late Harvard political scientist Samuel P. Huntington noticed that these convulsions seem to hit the United States every 60 years or so: the Revolutionary period of the 1760s and ’70s; the Jacksonian uprising of the 1820s and ’30s; the Progressive Era, which began in the 1890s; and the social-protest movements of the 1960s and early ’70s.

These moments share certain features. People feel disgusted by the state of society. Trust in institutions plummets. Moral indignation is widespread. Contempt for established power is intense.

A highly moralistic generation appears on the scene. It uses new modes of communication to seize control of the national conversation. Groups formerly outside of power rise up and take over the system. These are moments of agitation and excitement, frenzy and accusation, mobilization and passion.

In 1981, Huntington predicted that the next moral convulsion would hit America around the second or third decade of the 21st century—that is, right about now. And, of course, he was correct. Our moment of moral convulsion began somewhere around the mid-2010s, with the rise of a range of outsider groups: the white nationalists who helped bring Donald Trump to power; the young socialists who upended the neoliberal consensus and brought us Bernie Sanders and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez; activist students on campus; the Black Lives Matter movement, which rose to prominence after the killings of Eric Garner, Michael Brown, and Tamir Rice. Systems lost legitimacy. The earthquake had begun.

The events of 2020—the coronavirus pandemic; the killing of George Floyd; militias, social-media mobs, and urban unrest—were like hurricanes that hit in the middle of that earthquake. They did not cause the moral convulsion, but they accelerated every trend. They flooded the ravines that had opened up in American society and exposed every flaw.

Now, as we enter the final month of the election, this period of convulsion careens toward its climax. Donald Trump is in the process of shredding every norm of decent behavior and wrecking every institution he touches. Unable to behave responsibly, unable to protect himself from COVID-19, unable to even tell the country the truth about his own medical condition, he undermines the basic credibility of the government and arouses the suspicion that every word and act that surrounds him is a lie and a fraud. Finally, he threatens to undermine the legitimacy of our democracy in November and incite a vicious national conflagration that would leave us a charred and shattered nation. Trump is the final instrument of this crisis, but the conditions that brought him to power and make him so dangerous at this moment were decades in the making, and those conditions will not disappear if he is defeated.

From the July/August 2020 issue: History will judge the complicit

This essay is an account of the convulsion that brought us to this fateful moment. Its central focus is social trust. Social trust is a measure of the moral quality of a society—of whether the people and institutions in it are trustworthy, whether they keep their promises and work for the common good. When people in a church lose faith or trust in God, the church collapses. When people in a society lose faith or trust in their institutions and in each other, the nation collapses.

This is an account of how, over the past few decades, America became a more untrustworthy society. It is an account of how, under the stresses of 2020, American institutions and the American social order crumbled and were revealed as more untrustworthy still. We had a chance, in crisis, to pull together as a nation and build trust. We did not. That has left us a broken, alienated society caught in a distrust doom loop.

Read: Trust is collapsing in America

When moral convulsions recede, the national consciousness is transformed. New norms and beliefs, new values for what is admired and disdained, arise. Power within institutions gets renegotiated. Shifts in the collective consciousness are no merry ride; they come amid fury and chaos, when the social order turns liquid and nobody has any idea where things will end. Afterward, people sit blinking, battered, and shocked: What kind of nation have we become?

We can already glimpse pieces of the world after the current cataclysm. The most important changes are moral and cultural. The Baby Boomers grew up in the 1950s and ’60s, an era of family stability, widespread prosperity, and cultural cohesion. The mindset they embraced in the late ’60s and have embodied ever since was all about rebelling against authority, unshackling from institutions, and celebrating freedom, individualism, and liberation.

The emerging generations today enjoy none of that sense of security. They grew up in a world in which institutions failed, financial systems collapsed, and families were fragile. Children can now expect to have a lower quality of life than their parents, the pandemic rages, climate change looms, and social media is vicious. Their worldview is predicated on threat, not safety. Thus the values of the Millennial and Gen Z generations that will dominate in the years ahead are the opposite of Boomer values: not liberation, but security; not freedom, but equality; not individualism, but the safety of the collective; not sink-or-swim meritocracy, but promotion on the basis of social justice. Once a generation forms its general viewpoint during its young adulthood, it generally tends to carry that mentality with it to the grave 60 years later. A new culture is dawning. The Age of Precarity is here.

Recommended Reading

How America Ends

The President Is Winning His War on American Institutions

The New Reconstruction

One question has haunted me while researching this essay: Are we living through a pivot or a decline? During past moral convulsions, Americans rose to the challenge. They built new cultures and institutions, initiated new reforms—and a renewed nation went on to its next stage of greatness. I’ve spent my career rebutting the idea that America is in decline, but the events of these past six years, and especially of 2020, have made clear that we live in a broken nation. The cancer of distrust has spread to every vital organ.

Renewal is hard to imagine. Destruction is everywhere, and construction difficult to see. The problem goes beyond Donald Trump. The stench of national decline is in the air. A political, social, and moral order is dissolving. America will only remain whole if we can build a new order in its place.

The Age of Disappointment

The story begins , at least for me, in August 1991, in Moscow, where I was reporting for The Wall Street Journal . In a last desperate bid to preserve their regime, a group of hard-liners attempted a coup against the president of the Soviet Union, Mikhail Gorbachev. As Soviet troops and tanks rolled into Moscow, democratic activists gathered outside the Russian parliament building to oppose them. Boris Yeltsin, the president of Russia, mounted a tank and stood the coup down.

In that square, I met a 94-year-old woman who was passing out sandwiches to support the democratic protesters. Her name was Valentina Kosieva. She came to embody for me the 20th century, and all the suffering and savagery we were leaving behind as we marched—giddily, in those days—into the Information Age. She was born in 1898 in Samara. In 1905, she said, the Cossacks launched pogroms in her town and shot her uncle and her cousin. She was nearly killed after the Russian Revolution of 1917. She had innocently given shelter to some anti-Communist soldiers for “humanitarian reasons.” When the Reds came the next day, they decided to execute her. Only her mother’s pleadings saved her life.

In 1937, the Soviet secret police raided her apartment based on false suspicions, arrested her husband, and told her family they had 20 minutes to vacate. Her husband was sent to Siberia, where he died from either disease or execution—she never found out which. During World War II, she became a refugee, exchanging all her possessions for food. Her son was captured by the Nazis and beaten to death at the age of 17. After the Germans retreated, the Soviets ripped her people, the Kalmyks, from their homes and sent them into internal exile. For decades, she led a hidden life, trying to cover the fact that she was the widow of a supposed Enemy of the People.

Every trauma of Soviet history had happened to this woman. Amid the tumult of what we thought was the birth of a new, democratic Russia, she told me her story without bitterness or rancor. “If you get a letter completely free from self-pity,” Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn once wrote, it can only be from a victim of Soviet terror. “They are used to the worst the world can do, and nothing can depress them.” Kosieva had lived to see the death of this hated regime and the birth of a new world.

Those were the days of triumphant globalization. Communism was falling. Apartheid was ending. The Arab-Israeli dispute was calming down. Europe was unifying. China was prospering. In the United States, a moderate Republican president, George H. W. Bush, gave way to the first Baby Boomer president, a moderate Democrat, Bill Clinton. The American economy grew nicely. The racial wealth gap narrowed. All the great systems of society seemed to be working: capitalism, democracy, pluralism, diversity, globalization. It seemed, as Francis Fukuyama wrote in his famous “The End of History?” essay for The National Interest , “an unabashed victory for economic and political liberalism.”

We think of the 1960s as the classic Boomer decade, but the false summer of the 1990s was the high-water mark of that ethos. The first great theme of that era was convergence. Walls were coming down. Everybody was coming together. The second theme was the triumph of classical liberalism. Liberalism was not just a philosophy—it was a spirit and a zeitgeist, a faith that individual freedom would blossom in a loosely networked democratic capitalist world. Enterprise and creativity would be unleashed. America was the great embodiment and champion of this liberation. The third theme was individualism. Society flourished when individuals were liberated from the shackles of society and the state, when they had the freedom to be true to themselves.

For his 2001 book, Moral Freedom , the political scientist Alan Wolfe interviewed a wide array of Americans. The moral culture he described was no longer based on mainline Protestantism, as it had been for generations. Instead, Americans, from urban bobos to suburban evangelicals, were living in a state of what he called moral freedom : the belief that life is best when each individual finds his or her own morality—inevitable in a society that insists on individual freedom.

When you look back on it from the vantage of 2020, moral freedom, like the other dominant values of the time, contained within it a core assumption: If everybody does their own thing, then everything will work out for everybody. If everybody pursues their own economic self-interest, then the economy will thrive for all. If everybody chooses their own family style, then children will prosper. If each individual chooses his or her own moral code, then people will still feel solidarity with one another and be decent to one another. This was an ideology of maximum freedom and minimum sacrifice.

It all looks naive now. We were naive about what the globalized economy would do to the working class, naive to think the internet would bring us together, naive to think the global mixing of people would breed harmony, naive to think the privileged wouldn’t pull up the ladders of opportunity behind them. We didn’t predict that oligarchs would steal entire nations, or that demagogues from Turkey to the U.S. would ignite ethnic hatreds. We didn’t see that a hyper-competitive global meritocracy would effectively turn all of childhood into elite travel sports where a few privileged performers get to play and everyone else gets left behind.

Over the 20 years after I sat with Kosieva, it all began to unravel. The global financial crisis had hit, the Middle East was being ripped apart by fanatics. On May 15, 2011, street revolts broke out in Spain, led by the self-declared Indignados—“the outraged.” “They don’t represent us!” they railed as an insult to the Spanish establishment. It would turn out to be the cry of a decade.

We are living in the age of that disappointment. Millennials and members of Gen Z have grown up in the age of that disappointment, knowing nothing else. In the U.S. and elsewhere, this has produced a crisis of faith, across society but especially among the young. It has produced a crisis of trust.

The Trust Fall

Social trust is the confidence that other people will do what they ought to do most of the time. In a restaurant I trust you to serve untainted fish and you trust me not to skip out on the bill. Social trust is a generalized faith in the people of your community. It consists of smaller faiths. It begins with the assumption that we are interdependent, our destinies linked. It continues with the assumption that we share the same moral values. We share a sense of what is the right thing to do in different situations. As Kevin Vallier of Bowling Green State University argues in his forthcoming book, Trust in a Polarized Age , social trust also depends on a sense that we share the same norms. If two lanes of traffic are merging into one, the drivers in each lane are supposed to take turns. If you butt in line, I’ll honk indignantly. I’ll be angry, and I’ll want to enforce the small fairness rules that make our society function smoothly.

High-trust societies have what Fukuyama calls spontaneous sociability . People are able to organize more quickly, initiate action, and sacrifice for the common good. When you look at research on social trust, you find all sorts of virtuous feedback loops. Trust produces good outcomes, which then produce more trust. In high-trust societies, corruption is lower and entrepreneurship is catalyzed. Higher-trust nations have lower economic inequality , because people feel connected to each other and are willing to support a more generous welfare state. People in high-trust societies are more civically engaged. Nations that score high in social trust —like the Netherlands, Sweden, China, and Australia—have rapidly growing or developed economies. Nations with low social trust —like Brazil, Morocco, and Zimbabwe—have struggling economies. As the ethicist Sissela Bok once put it, “Whatever matters to human beings, trust is the atmosphere in which it thrives.”

During most of the 20th century, through depression and wars, Americans expressed high faith in their institutions. In 1964, for example, 77 percent of Americans said they trusted the federal government to do the right thing most or all of the time. Then came the last two moral convulsions. In the late 1960s and ’70s, amid Vietnam and Watergate, trust in institutions collapsed. By 1994, only one in five Americans said they trusted government to do the right thing. Then came the Iraq War and the financial crisis and the election of Donald Trump. Institutional trust levels remained pathetically low . What changed was the rise of a large group of people who were actively and poisonously alienated—who were not only distrustful but explosively distrustful. Explosive distrust is not just an absence of trust or a sense of detached alienation—it is an aggressive animosity and an urge to destroy. Explosive distrust is the belief that those who disagree with you are not just wrong but illegitimate. In 1997, 64 percent of Americans had a great or good deal of trust in the political competence of their fellow citizens ; today only a third of Americans feel that way.

Falling trust in institutions is bad enough; it’s when people lose faith in each other that societies really begin to fall apart. In most societies, interpersonal trust is stable over the decades. But for some—like Denmark, where about 75 percent say the people around them are trustworthy, and the Netherlands, where two-thirds say so—the numbers have actually risen.

In America, interpersonal trust is in catastrophic decline. In 2014, according to the General Social Survey conducted by NORC at the University of Chicago, only 30.3 percent of Americans agreed that “most people can be trusted,” the lowest number the survey has recorded since it started asking the question in 1972. Today, a majority of Americans say they don’t trust other people when they first meet them .

Is mistrust based on distorted perception or is it a reflection of reality? Are people increasingly mistrustful because they are watching a lot of negative media and get a falsely dark view of the world? Or are they mistrustful because the world is less trustworthy, because people lie, cheat, and betray each other more than they used to?

There’s evidence to suggest that marital infidelity , academic cheating , and animal cruelty are all on the rise in America, but it’s hard to directly measure the overall moral condition of society—how honest people are, and how faithful. The evidence suggests that trust is an imprint left by experience, not a distorted perception. Trust is the ratio between the number of people who betray you and the number of people who remain faithful to you. It’s not clear that there is more betrayal in America than there used to be—but there are certainly fewer faithful supports around people than there used to be. Hundreds of books and studies on declining social capital and collapsing family structure demonstrate this. In the age of disappointment, people are less likely to be surrounded by faithful networks of people they can trust.

Thus the Harvard political scientist Robert Putnam argues that it’s a great mistake to separate the attitude (trust) from the behavior (morally right action). People become trusting when the world around them is trustworthy. When they are surrounded by people who live up to their commitments. When they experience their country as a fair place. As Vallier puts it, trust levels are a reflection of the moral condition of a nation at any given time. I’d add that high national trust is a collective moral achievement. High national distrust is a sign that people have earned the right to be suspicious. Trust isn’t a virtue—it’s a measure of other people’s virtue.

Unsurprisingly, the groups with the lowest social trust in America are among the most marginalized. Trust, like much else, is unequally distributed across American society, and the inequality is getting worse. Each of these marginalized groups has seen an additional and catastrophic decline in trust over the past few years.

Black Americans have been one of the most ill-treated groups in American history; their distrust is earned distrust. In 2018, 37.3 percent of white Americans felt that most people can be trusted, according to the General Social Survey, but only 15.3 percent of Black Americans felt the same. This is not general misanthropy. Black Americans have high trust in other Black Americans; it’s the wider society they don’t trust, for good and obvious reasons. And Black perceptions of America’s fairness have tumbled further in the age of disappointment. In 2002, 43 percent of Black Americans were very or somewhat satisfied with the way Black people are treated in the U.S. By 2018, only 18 percent felt that way, according to Gallup .

The second disenfranchised low-trust group includes the lower-middle class and the working poor. According to Tim Dixon, an economist and the co-author of a 2018 study that examined polarization in America, this group makes up about 40 percent of the country. “They are driven by the insecurity of their place in society and in the economy,” he says. They are distrustful of technology and are much more likely to buy into conspiracy theories. “They’re often convinced by stories that someone is trying to trick them, that the world is against them,” he says. Distrust motivated many in this group to vote for Donald Trump , to stick a thumb in the eye of the elites who had betrayed them.

This brings us to the third marginalized group that scores extremely high on social distrust: young adults. These are people who grew up in the age of disappointment. It’s the only world they know.

In 2012, 40 percent of Baby Boomers believed that most people can be trusted , as did 31 percent of members of Generation X. In contrast, only 19 percent of Millennials said most people can be trusted. Seventy-three percent of adults under 30 believe that “most of the time, people just look out for themselves,” according to a Pew survey from 2018 . Seventy-one percent of those young adults say that most people “would try to take advantage of you if they got a chance.”

Many young people look out at a world they believe is screwed up and untrustworthy in fundamental ways. A mere 10 percent of Gen Zers trust politicians to do the right thing. Millennials are twice as likely as their grandparents to say that families should be able to opt out of vaccines. Only 35 percent of young people, versus 67 percent of old people, believe that Americans respect the rights of people who are not like them . Fewer than a third of Millennials say America is the greatest country in the world , compared to 64 percent of members of the Silent Generation.

Human beings need a basic sense of security in order to thrive; as the political scientist Ronald F. Inglehart puts it, their “values and behavior are shaped by the degree to which survival is secure.” In the age of disappointment, our sense of safety went away. Some of this is physical insecurity: school shootings, terrorist attacks, police brutality, and overprotective parenting at home that leaves young people incapable of handling real-world stress. But the true insecurity is financial, social, and emotional.

First, financial insecurity: By the time the Baby Boomers hit a median age of 35, their generation owned 21 percent of the nation’s wealth. As of last year, Millennials—who will hit an average age of 35 in three years— owned just 3.2 percent of the nation’s wealth .

Next, emotional insecurity: Americans today experience more instability than at any period in recent memory— fewer children growing up in married two-parent households , more single-parent households , more depression , and higher suicide rates .

Then, identity insecurity. People today live in what the late sociologist Zygmunt Bauman called liquid modernity . All the traits that were once assigned to you by your community, you must now determine on your own: your identity, your morality, your gender, your vocation, your purpose, and the place of your belonging. Self-creation becomes a major anxiety-inducing act of young adulthood.

Finally, social insecurity. In the age of social media our “sociometers”—the antennae we use to measure how other people are seeing us—are up and on high alert all the time. Am I liked? Am I affirmed? Why do I feel invisible? We see ourselves in how we think others see us. Their snarkiness turns into my self-doubt, their criticism into my shame, their obliviousness into my humiliation. Danger is ever present. “For many people, it is impossible to think without simultaneously thinking about what other people would think about what you’re thinking,” the educator Fredrik deBoer has written. “This is exhausting and deeply unsatisfying. As long as your self-conception is tied up in your perception of other people’s conception of you, you will never be free to occupy a personality with confidence; you’re always at the mercy of the next person’s dim opinion of you and your whole deal.”

In this world, nothing seems safe; everything feels like chaos.

The Distrust Mindset

Distrust sows distrust . It produces the spiritual state that Emile Durkheim called anomie , a feeling of being disconnected from society, a feeling that the whole game is illegitimate, that you are invisible and not valued, a feeling that the only person you can really trust is yourself.

Distrustful people try to make themselves invulnerable, armor themselves up in a sour attempt to feel safe. Distrust and spiritual isolation lead people to flee intimacy and try to replace it with stimulation. Distrust, anxiety, and anomie are at the root of the 73 percent increase in depression among Americans aged 18 to 25 from 2007 to 2018, and of the shocking rise in suicide . “When we have no one to trust, our brains can self-destruct,” Ulrich Boser writes in his book on the science of trust, The Leap .

People plagued by distrust can start to see threats that aren’t there; they become risk averse. Americans take fewer risks and are much less entrepreneurial than they used to be. In 2014, the rate of business start-ups hit a nearly 40-year low . Since the early 1970s, the rate at which people move across state lines each year has dropped by 56 percent. People lose faith in experts. They lose faith in truth, in the flow of information that is the basis of modern society. “A world of truth is a world of trust, and vice versa,” Rabbi Jonathan Sacks writes in his book Morality .

In periods of distrust, you get surges of populism; populism is the ideology of those who feel betrayed. Contempt for “insiders” rises, as does suspicion toward anybody who holds authority. People are drawn to leaders who use the language of menace and threat, who tell group-versus-group power narratives. You also get a lot more political extremism. People seek closed, rigid ideological systems that give them a sense of security. As Hannah Arendt once observed, fanaticism is a response to existential anxiety. When people feel naked and alone, they revert to tribe. Their radius of trust shrinks, and they only trust their own kind. Donald Trump is the great emblem of an age of distrust—a man unable to love, unable to trust. When many Americans see Trump’s distrust, they see a man who looks at the world as they do.

By February 2020, America was a land mired in distrust. Then the plague arrived.

The Failure of Institutions

From the start , the pandemic has hit the American mind with sledgehammer force. Anxiety and depression have spiked. In April, Gallup recorded a record drop in self-reported well-being, as the share of Americans who said they were thriving fell to the same low point as during the Great Recession. These kinds of drops tend to produce social upheavals. A similar drop was seen in Tunisian well-being just before the street protests that led to the Arab Spring.

The emotional crisis seems to have hit low-trust groups the hardest. Pew found that “low trusters” were more nervous during the early months of the pandemic, more likely to have trouble sleeping, more likely to feel depressed, less likely to say the public authorities were responding well to the pandemic. Eighty-one percent of Americans under 30 reported feeling anxious, depressed, lonely, or hopeless at least one day in the previous week, compared to 48 percent of adults 60 and over.

Americans looked to their governing institutions to keep them safe. And nearly every one of their institutions betrayed them. The president downplayed the crisis, and his administration was a daily disaster area. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention produced faulty tests, failed to provide up-to-date data on infections and deaths, and didn’t provide a trustworthy voice for a scared public. The Food and Drug Administration wouldn’t allow private labs to produce their own tests without a lengthy approval process.

The sense of betrayal was magnified when people looked abroad. In nations that ranked high on the World Values Survey measure of interpersonal trust—like China, Australia, and most of the Nordic states—leaders were able to mobilize quickly, come up with a plan, and count on citizens to comply with the new rules. In low-trust nations—like Mexico, Spain, and Brazil—there was less planning, less compliance, less collective action, and more death. Countries that fell somewhere in the middle—including the U.S., Germany, and Japan—had a mixed record depending on the quality of their leadership. South Korea, where more than 65 percent of people say they trust government when it comes to health care, was able to build a successful test-and-trace regime. In America, where only 31 percent of Republicans and 44 percent of Democrats say the government should be able to use cellphone data to track compliance with experts’ coronavirus social-contact guidelines, such a system was never really implemented.

Francis Fukuyama: Trust makes the difference against the coronavirus

For decades, researchers have been warning about institutional decay. Institutions get caught up in one of those negative feedback loops that are so common in a world of mistrust. They become ineffective and lose legitimacy. People who lose faith in them tend not to fund them. Talented people don’t go to work for them. They become more ineffective still. In 1969, Daniel Patrick Moynihan made this core point in a memo to his boss-to-be, President-elect Richard Nixon: “In one form or another all of the major domestic problems facing you derive from the erosion of the authority of the institutions of American society. This is a mysterious process of which the most that can be said is that once it starts it tends not to stop.”

On the right, this anti-institutional bias has manifested itself as hatred of government; an unwillingness to defer to expertise, authority, and basic science; and a reluctance to fund the civic infrastructure of society, such as a decent public health system. In state after state Republican governors sat inert, unwilling to organize or to exercise authority, believing that individuals should be free to take care of themselves.

On the left, distrust of institutional authority has manifested as a series of checks on power that have given many small actors the power to stop common plans, producing what Fukuyama calls a vetocracy . Power to the people has meant no power to do anything, and the result is a national NIMBYism that blocks social innovation in case after case.

In 2020, American institutions groaned and sputtered. Academics wrote up plan after plan and lobbed them onto the internet. Few of them went anywhere. America had lost the ability to build new civic structures to respond to ongoing crises like climate change, opioid addiction, and pandemics, or to reform existing ones.

From the October 2020 issue: Can American democracy be saved?

In high-trust eras, according to Yuval Levin, who is an American Enterprise Institute scholar and the author of A Time to Build: From Family and Community to Congress and the Campus, How Recommitting to Our Institutions Can Revive the American Dream , people have more of a “first-person-plural” instinct to ask, “What can we do?” In a lower-trust era like today, Levin told me, “there is a greater instinct to say, ‘ They’re failing us.’ We see ourselves as outsiders to the systems—an outsider mentality that’s hard to get out of.”

Americans haven’t just lost faith in institutions; they’ve come to loathe them, even to think that they are evil. A Democracy Fund + UCLA Nationscape survey found that 55 percent of Americans believe that the coronavirus that causes COVID-19 was created in a lab and 59 percent believe that the U.S. government is concealing the true number of deaths. Half of all Fox News viewers believe that Bill Gates is plotting a mass-vaccination campaign so he can track people. This spring, nearly a third of Americans were convinced that it was probably or definitely true that a vaccine existed but was being withheld by the government. When Trump was hospitalized for COVID-19 on October 2, many people conspiratorially concluded that the administration was lying about his positive diagnosis for political gain. When government officials briefed the nation about how sick he was, many people assumed they were obfuscating, which in fact they were.

The failure of and withdrawal from institutions decimated America’s pandemic response, but the damage goes beyond that. That’s because institutions like the law, the government, the police, and even the family don’t merely serve social functions, Levin said; they form the individuals who work and live within them. The institutions provide rules to live by, standards of excellence to live up to, social roles to fulfill.

By 2020, people had stopped seeing institutions as places they entered to be morally formed, Levin argued. Instead, they see institutions as stages on which they can perform, can display their splendid selves. People run for Congress not so they can legislate, but so they can get on TV. People work in companies so they can build their personal brand. The result is a world in which institutions not only fail to serve their social function and keep us safe, they also fail to form trustworthy people. The rot in our structures spreads to a rot in ourselves.

The Failure of Society

The coronavirus has confronted America with a social dilemma. A social dilemma, the University of Pennsylvania scholar Cristina Bicchieri notes , is “a situation in which each group member gets a higher outcome if she pursues her individual self-interest, but everyone in the group is better off if all group members further the common interest.” Social distancing is a social dilemma. Many low-risk individuals have been asked to endure some large pain (unemployment, bankruptcy) and some small inconvenience (mask wearing) for the sake of the common good. If they could make and keep this moral commitment to each other in the short term, the curve would be crushed, and in the long run we’d all be better off. It is the ultimate test of American trustworthiness.

In March and April, vast majorities of Americans said they supported social distancing, and society seemed to be coming together. It didn’t last. Americans locked down a bit in early March, but never as much as people in some other countries. By mid-April, they told themselves—and pollsters—that they were still socially distancing, but that was increasingly a self-deception. While pretending to be rigorous, people relaxed and started going out. It was like watching somebody gradually give up on a diet. There wasn’t a big moment of capitulation, just an extra chocolate bar here, a bagel there, a scoop of ice cream before bed. By May, most people had become less strict about quarantining. Many states officially opened up in June when infection rates were still much higher than in countries that had successfully contained the disease. On June 20, 500,000 people went to reopened bars and nightspots in Los Angeles County alone.

You can blame Trump or governors or whomever you like, but in reality this was a mass moral failure of Republicans and Democrats and independents alike. This was a failure of social solidarity, a failure to look out for each other.

Alexis de Tocqueville discussed a concept called the social body . Americans were clearly individualistic, he observed, but they shared common ideas and common values, and could, when needed, produce common action. They could form a social body. Over time, those common values eroded, and were replaced by a value system that put personal freedom above every other value. When Americans were confronted with the extremely hard task of locking down for months without any of the collective resources that would have made it easier—habits of deference to group needs; a dense network of community bonds to help hold each other accountable; a history of trust that if you do the right thing, others will too; preexisting patterns of cooperation; a sense of shame if you deviate from the group—they couldn’t do it. America failed.

By August, most Americans understood the failure. Seventy-two percent of Danes said they felt more united after the COVID-19 outbreak. Only 18 percent of Americans felt the same.

The Crack-up

In the spring and summer of 2020 , six years of moral convulsion came to a climax. This wasn’t just a political and social crisis, it was also an emotional trauma. The week before George Floyd was killed, the National Center for Health Statistics released data showing that a third of all Americans were showing signs of clinical anxiety or depression. By early June, after Floyd’s death, the percentage of Black Americans showing clinical signs of depression and anxiety disorders had jumped from 36 to 41 percent. Depression and anxiety rates were three times those of the year before. At the end of June, one-quarter of young adults aged 18 to 24 said they had contemplated suicide during the previous 30 days.

In the immediate aftermath of his death, Floyd became the emblematic American—the symbol of a society in which no one, especially Black Americans, was safe. The protests, which took place in every state, were diverse. The young white people at those marches weren’t only marching as allies of Black people. They were marching for themselves, as people who grew up in a society they couldn’t fully trust. Two low-trust sectors of American society formed an alliance to demand change.

From the September 2020 issue: Is this the beginning of the end of American racism?

By late June, American national pride was lower than at any time since Gallup started measuring, in 2001. American happiness rates were at their lowest level in nearly 50 years. In another poll, 71 percent of Americans said they were angry about the state of the country, and just 17 percent said they were proud. According to an NBC News/ Wall Street Journal poll, 80 percent of American voters believe that “things in the country are out of control.” Gun sales in June were 145 percent higher than in the previous year. By late June, it was clear that America was enduring a full-bore crisis of legitimacy, an epidemic of alienation, and a loss of faith in the existing order.

Years of distrust burst into a torrent of rage. There were times when the entire social fabric seemed to be disintegrating. Violence rocked places like Portland, Kenosha, and beyond. The murder rates soared in city after city. The most alienated, anarchic actors in society—antifa, the Proud Boys, QAnon—seemed to be driving events. The distrust doom loop was now at hand.

From the June 2020 issue: The prophecies of Q

The Age of Precarity

Cultures are collective responses to common problems. But when reality changes, culture takes a few years, and a moral convulsion, to completely shake off the old norms and values.

The culture that is emerging, and which will dominate American life over the next decades, is a response to a prevailing sense of threat. This new culture values security over liberation, equality over freedom, the collective over the individual. We’re seeing a few key shifts.

From risk to security . As Albena Azmanova, a political theorist at the University of Kent, has argued, we’ve entered an age of precarity in which every political or social movement has an opportunity pole and a risk pole. In the opportunity mentality, risk is embraced because of the upside possibilities. In the risk mindset, security is embraced because people need protection from downside dangers. In this period of convulsion, almost every party and movement has moved from its opportunity pole to its risk pole. Republicans have gone from Reaganesque free trade and open markets to Trumpesque closed borders. Democrats have gone from the neoliberalism of Kennedy and Clinton to security-based policies like a universal basic income and the protections offered by a vastly expanded welfare state. Campus culture has gone from soft moral relativism to strict moralism. Evangelicalism has gone from the open evangelism of Billy Graham to the siege mentality of Franklin Graham .

From achievement to equality . The culture that emerged from the 1960s upheavals put heavy emphasis on personal development and personal growth. The Boomers emerged from, and then purified, a competitive meritocracy that put career achievement at the center of life and boosted those who succeeded into ever more exclusive lifestyle enclaves.

In the new culture we are entering, that meritocratic system looks more and more like a ruthless sorting system that excludes the vast majority of people, rendering their life precarious and second class, while pushing the “winners” into a relentless go-go lifestyle that leaves them exhausted and unhappy . In the emerging value system, “privilege” becomes a shameful sin. The status rules flip. The people who have won the game are suspect precisely because they’ve won. Too-brazen signs of “success” are scrutinized and shamed. Equality becomes the great social and political goal. Any disparity—racial, economic, meritocratic—comes to seem hateful.

From self to society . If we’ve lived through an age of the isolated self, people in the emerging culture see embedded selves. Socialists see individuals embedded in their class group. Right-wing populists see individuals as embedded pieces of a national identity group. Left-wing critical theorists see individuals embedded in their racial, ethnic, gender, or sexual-orientation identity group. Each person speaks from the shared group consciousness. (“Speaking as a progressive gay BIPOC man …”) In an individualistic culture, status goes to those who stand out; in collective moments, status goes to those who fit in. The cultural mantra shifts from “Don’t label me!” to “My label is who I am.”

From global to local . A community is a collection of people who trust each other. Government follows the rivers of trust. When there is massive distrust of central institutions, people shift power to local institutions, where trust is higher. Power flows away from Washington to cities and states.

Derek Thompson: Why America’s institutions are failing

From liberalism to activism . Baby Boomer political activism began with a free-speech movement. This was a generation embedded in enlightenment liberalism, which was a long effort to reduce the role of passions in politics and increase the role of reason. Politics was seen as a competition between partial truths.

Liberalism is ill-suited for an age of precarity. It demands that we live with a lot of ambiguity, which is hard when the atmosphere already feels unsafe. Furthermore, it is thin. It offers an open-ended process of discovery when what people hunger for is justice and moral certainty. Moreover, liberalism’s niceties come to seem like a cover that oppressors use to mask and maintain their systems of oppression. Public life isn’t an exchange of ideas; it’s a conflict of groups engaged in a vicious death struggle. Civility becomes a “code for capitulation to those who want to destroy us,” as the journalist Dahlia Lithwick puts it .

The cultural shifts we are witnessing offer more safety to the individual at the cost of clannishness within society. People are embedded more in communities and groups, but in an age of distrust, groups look at each other warily, angrily, viciously. The shift toward a more communal viewpoint is potentially a wonderful thing, but it leads to cold civil war unless there is a renaissance of trust. There’s no avoiding the core problem. Unless we can find a way to rebuild trust, the nation does not function.

How to Rebuild Trust

When you ask political scientists or psychologists how a culture can rebuild social trust, they aren’t much help. There just haven’t been that many recent cases they can study and analyze. Historians have more to offer, because they can cite examples of nations that have gone from pervasive social decay to relative social health. The two most germane to our situation are Great Britain between 1830 and 1848 and the United States between 1895 and 1914.

People in these eras lived through experiences parallel to ours today. They saw the massive economic transitions caused by the Industrial Revolution. They experienced great waves of migration, both within the nation and from abroad. They lived with horrific political corruption and state dysfunction. And they experienced all the emotions associated with moral convulsions—the sort of indignation, shame, guilt, and disgust we’re experiencing today. In both periods, a highly individualistic and amoral culture was replaced by a more communal and moralistic one.

But there was a crucial difference between those eras and our own, at least so far. In both cases, moral convulsion led to frenetic action. As Richard Hofstadter put it in The Age of Reform , the feeling of indignation sparked a fervent and widespread desire to assume responsibility, to organize, to build. During these eras, people built organizations at a dazzling pace. In the 1830s, the Clapham Sect, a religious revival movement, campaigned for the abolition of slavery and promoted what we now think of as Victorian values. The Chartists, a labor movement, gathered the working class and motivated them to march and strike. The Anti-Corn Law League worked to reduce the power of the landed gentry and make food cheaper for the workers. These movements agitated from both the bottom up and the top down.

As Robert Putnam and Shaylyn Romney Garrett note in their forthcoming book, The Upswing , the American civic revival that began in the 1870s produced a stunning array of new organizations: the United Way, the NAACP, the Boy Scouts, the Forest Service, the Federal Reserve System, 4-H clubs, the Sierra Club, the settlement-house movement, the compulsory-education movement, the American Bar Association, the American Legion, the ACLU, and on and on. These were missional organizations, with clearly defined crusading purposes. They put tremendous emphasis on cultivating moral character and social duty—on honesty, reliability, vulnerability, and cooperativeness, and on shared values, rituals, and norms. They tended to place responsibility on people who had not been granted power before. “Few things help an individual more than to place responsibility upon him, and to let him know that you trust him,” Booker T. Washington wrote in his 1901 autobiography.

After the civic revivals, both nations witnessed frenetic political reform. During the 1830s, Britain passed the Reform Act, which widened the franchise; the Factory Act, which regulated workplaces; and the Municipal Corporations Act, which reformed local government. The Progressive Era in America saw an avalanche of reform: civil-service reform; food and drug regulation; the Sherman Act, which battled the trusts; the secret ballot; and so on. Civic life became profoundly moralistic, but political life became profoundly pragmatic and anti-ideological. Pragmatism and social-science expertise were valued.

Can America in the 2020s turn itself around the way the America of the 1890s, or the Britain of the 1830s, did? Can we create a civic renaissance and a legislative revolution? I’m not so sure. If you think we’re going back to the America that used to be—with a single cohesive mainstream culture; with an agile, trusted central government; with a few mainstream media voices that police a coherent national conversation; with an interconnected, respected leadership class; with a set of dominant moral values based on mainline Protestantism or some other single ethic—then you’re not being realistic. I see no scenario in which we return to being the nation we were in 1965, with a cohesive national ethos, a clear national establishment, trusted central institutions, and a pop-culture landscape in which people overwhelmingly watch the same shows and talked about the same things. We’re too beaten up for that. The age of distrust has smashed the converging America and the converging globe—that great dream of the 1990s—and has left us with the reality that our only plausible future is decentralized pluralism.

A model for that can be found in, of all places, Houston, Texas, one of the most diverse cities in America. At least 145 languages are spoken in the metro area. It has no real central downtown district, but, rather, a wide diversity of scattered downtowns and scattered economic and cultural hubs. As you drive across town you feel like you’re successively in Lagos, Hanoi, Mumbai, White Plains, Beverly Hills, Des Moines, and Mexico City. In each of these cultural zones, these islands of trust, there is a sense of vibrant activity and experimentation—and across the whole city there is an atmosphere of openness, and goodwill, and the American tendency to act and organize that Hofstadter discussed in The Age of Reform .

Not every place can or would want to be Houston—its cityscape is ugly, and I’m not a fan of its too-libertarian zoning policies—but in that rambling, scattershot city I see an image of how a hyper-diverse, and more trusting, American future might work.

The key to making decentralized pluralism work still comes down to one question: Do we have the energy to build new organizations that address our problems, the way the Brits did in the 1830s and Americans did in the 1890s? Personal trust can exist informally between two friends who rely on each other, but social trust is built within organizations in which people are bound together to do joint work, in which they struggle together long enough for trust to gradually develop, in which they develop shared understandings of what is expected of each other, in which they are enmeshed in rules and standards of behavior that keep them trustworthy when their commitments might otherwise falter. Social trust is built within the nitty-gritty work of organizational life : going to meetings, driving people places, planning events, sitting with the ailing, rejoicing with the joyous, showing up for the unfortunate. Over the past 60 years, we have given up on the Rotary Club and the American Legion and other civic organizations and replaced them with Twitter and Instagram. Ultimately, our ability to rebuild trust depends on our ability to join and stick to organizations.

From the June 2020 issue: We are living in a failed state

The period between the deaths of Eric Garner and Michael Brown in the summer of 2014 and the election of November 2020 represents the latest in a series of great transitional moments in American history. Whether we emerge from this transition stronger depends on our ability, from the bottom up and the top down, to build organizations targeted at our many problems. If history is any guide, this will be the work not of months, but of one or two decades.

For centuries, America was the greatest success story on earth, a nation of steady progress, dazzling achievement, and growing international power. That story threatens to end on our watch, crushed by the collapse of our institutions and the implosion of social trust. But trust can be rebuilt through the accumulation of small heroic acts—by the outrageous gesture of extending vulnerability in a world that is mean, by proffering faith in other people when that faith may not be returned. Sometimes trust blooms when somebody holds you against all logic, when you expected to be dropped. It ripples across society as multiplying moments of beauty in a storm.

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2023 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

Why You May Have Trust Issues and How to Overcome Them

Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/IMG_9791-89504ab694d54b66bbd72cb84ffb860e.jpg)

Daniel B. Block, MD, is an award-winning, board-certified psychiatrist who operates a private practice in Pennsylvania.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/block-8924ca72ff94426d940e8f7e639e3942.jpg)

Kemal Yildirim / Getty Images

- Why Trust Matters

Signs of Trust Issues

Types of trust issues.

- Causes of Distrust

- Overcoming Trust Issues

Learn to Trust Yourself

Trust is a critical part of any relationship. Without trust—especially trust between two romantic partners—it is difficult to have a healthy, long-lasting relationship . People who have experienced some type of betrayal, such as unfaithfulness in a relationship, may develop trust issues that can interfere with future relationships.

Trust issues can manifest in a variety of ways. For example, a person who finds it difficult to trust may not believe what other people say. They may feel suspicious of what others want from them and may question other people's intentions and motivations. It makes it incredibly difficult to develop an intimate, close connection with another person.

This article discusses trust issues, including the signs that you might have problems with trust and what causes a lack of faith in other people. It also covers some of the steps that you can take to overcome problems with trust.

Why Trust Issues Are Harmful

Trust has a number of benefits that are important for the health of your relationships as well as your own emotional well-being. Trust allows you to:

- Be vulnerable

- Be yourself

- Feel safe and secure

- Focus on positivity

- Increase closeness and intimacy

- Minimize conflict

Trust is important in relationships because it allows you the opportunity to relax, be yourself, and depend on another person. It provides you with the safety and security you need to turn to another person for comfort, reassurance, assistance, and affection.

Trust is the belief that another person is honest and reliable. It is a feeling that you can depend on that person because they offer safety and security. Trust has been described as a firm belief in the ability, strength, reliability, and truth of someone or something.

There are a number of different behaviors that might indicate that you or your partner have a problem with trusting others. Some of these include:

- Always assuming the worst : Your trust issues could lead you to assume the worst about people around you, even when they have proven themselves trustworthy in the past. For example, when someone offers to help you, you wonder if they are expecting something from you later on.

- Suspiciousness : Trust issues can make you feel suspicious about other people's intentions, even if there is little to indicate that their actions are suspect. You might feel like others are trying to harm you or deceive you.

- Self-sabotage : Trust issues often lead to self-sabotage . For example, you might engage in behaviors that interfere with your relationship because you assume it's better to end things now rather than be disappointed later.

- Unhealthy relationships : People with trust issues almost always struggle to build healthy, long-lasting relationships. It's normal for trust to take a while to develop within romantic relationships, but people without trust may never experience this type of connection.

- Lack of forgiveness : When trust is an issue, it is difficult—if not impossible—to move on after a betrayal of trust has occurred. This inability to forgive and forget can affect your entire life; not just your interactions with others. It can lead to feelings of guilt, shame, bitterness, and regret.

- Distancing yourself : In many cases, a lack of trust can lead people to build a wall between themselves and other people. You avoid relationships altogether because you fear betrayal or disappointment.

- Focusing on the negative : No matter the situation, you always focus on what you expect will go wrong. You tend to notice other people’s flaws, weaknesses, or mistakes rather than focusing on their positive qualities.

When trust interferes with your ability to form healthy, stable relationships, it can also leave you feeling isolated, lonely, and misunderstood.

Trust problems don't just affect your romantic relationships. They can create conflict and poor communication in any type of relationship, whether it is with your friends, co-workers, or other family members.

Some common types of relationships that can be affected by trust issues include:

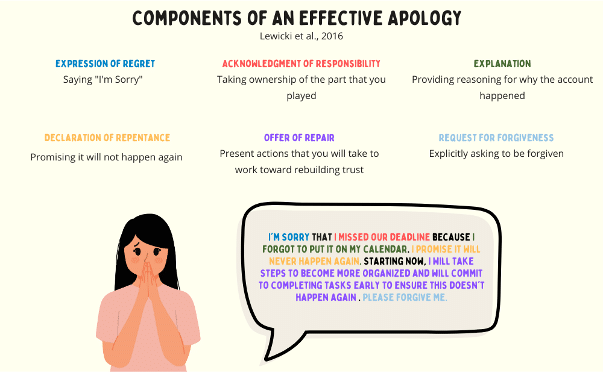

- Romantic relationships : People with trust issues often struggle to rely on or believe in their romantic partners. This can lead to a range of problems in relationships, including trust-related infidelity, unwillingness to commit , and difficulty apologizing when trust has been broken.

- Friendships : Just as people have trust issues within romantic relationships, they might also struggle with trusting their friends. Difficulty trusting friends might stem from a fear of disappointment or betrayal. Being let down by people in the past can make it hard to open yourself up to trusting friends again in the future.

- Workplace relationships : There are many reasons why someone might not trust co-workers. They might be concerned that their co-workers are conspiring against them, for instance, or just assume that trusting co-workers is not that important.

Generalized trust refers to a belief in whether or not most other people can be trusted. It can affect a person's ability to trust people, groups, organizations, and governments. Research suggests that this type of trust is influenced by a variety of forces, including culture, social interaction experiences throughout life, and media influences.

Problems with trust can take a toll in many different areas of your life. It can make your romantic relationships more fraught, interfere with your ability to maintain friendships, and contribute to conflict in the workplace.

What Causes Trust Issues?

A 2017 study found that a tendency to trust is influenced by genetic factors. Distrust, on the other hand, is not linked to genetics and is primarily associated with socialization factors, including family dynamics and influences.

People often have trust issues because they have been betrayed in the past. Early childhood experiences, in particular, play a major role in shaping your ability to trust the people around you.

Psychologist Erik Erikson developed a theory of development that suggested that the earliest years of life are all about learning whether the people around you could be trusted with your care and safety. Whether you learn this trust or mistrust , he suggested, plays a foundational role in future development.

This means that trust issues could stem from any number of sources, including:

- Betrayal in a relationship : Infidelity is incredibly hurtful and can lead to trust issues in future relationships.

- Parental conflicts : If children witness trust problems within their family, they may fear that the same thing will happen to them in future romantic relationships in adulthood.

- Social rejection : Being rejected by peers during childhood or adolescence may also make it difficult to trust other people. This type of trust issue can be exacerbated when the person being rejected is unable to determine why they are being excluded. Repeated rejections can make trust issues that much more difficult to overcome.

- Negative life experiences : People who have experienced trauma—especially while growing up—are likely to develop trust issues in adulthood. These trust issues could manifest in many different ways, including difficulty trusting friends or romantic partners, fear of trust-related betrayal, or difficulty forgiving people for breaking their trust.

- Attachment styles : Experts also suggest that your attachment style , or your characteristic pattern of behavior in a relationship, also plays a role in how you respond to trust in relationships. People with a secure attachment style may be more likely to trust others and forgive mistakes. Those with insecure attachment styles, on the other hand, struggle more with trust and are more likely to experience jealousy and anxiety in relationships.

Having one or more of these types of trust problems does not necessarily mean that you have a problem with trust. But it may indicate that you need to address these issues if they are causing you pain or preventing you from forming or maintaining interpersonal relationships .

Trust issues are often connected to negative experiences in the past. Being let down or betrayed by people who you trusted—whether it was a friend, partner, parent, or other trusted figure or institution—can interfere with your ability to believe in others.

How to Overcome Trust Issues

While it can be a challenging emotional undertaking, it is possible to overcome problems with trust. Here are a few trust-building strategies you can use:

Build Trust Slowly

It is important to trust people enough to allow them into your life and, in some cases, to forgive them for their mistakes. Taking your time with it can sometimes help. If you find yourself trying to trust too quickly (and perhaps, too intensely), it may be time to pull back and work up to that level of trust again.

Talk About Your Trust Issues

While you don’t need to provide every detail about what happened to you in the past, being open about why you struggle with trust can help others understand you better. By communicating with your partner , they can be more aware of how their actions might be interpreted.

Distinguish Between Trust and Control

People with trust issues often feel a need for control . This can sometimes manifest as mistrusting behavior. You might feel like you are being betrayed or taken advantage of if you don't have complete control over every situation.

However, this will only hurt your relationships in the long run. Learning how much control you should yield in a given situation is key to building trust with other people.

Make Trust a Priority

Trusting others can be difficult, but trust-building is an essential part of any relationship, romantic or otherwise. Make trust a priority in your life—even if it's challenging to do.

Be Trustworthy

If you try to build trust with someone else, you have to be willing to trust them first. This means being open about your feelings, opinions, thoughts, and limits.

It also means being understanding when the person breaks that trust because everyone makes mistakes. Learning how to balance these two ideas will help establish healthy interpersonal relationships that are based on trust.

Consider Therapy

Therapy can also be helpful for overcoming trust issues. The therapeutic alliance that you form with your therapist can be a powerful tool for learning how to trust other people.

By working with an experienced mental health professional, you can learn more about why you struggle with trust and learn new coping skills that will help you start to rebuild trust in your relationships.

Get Help Now

We've tried, tested, and written unbiased reviews of the best online therapy programs including Talkspace, BetterHelp, and ReGain. Find out which option is the best for you.

One of the best ways to practice trust is to trust yourself. This doesn’t mean you should never question yourself or your choices. It just means that you should build a stronger self-awareness that can help guide your judgments and interactions with others.

Practicing mindfulness is one strategy that can be helpful. When you utilize mindfulness, you are able to become more aware of how you are feeling in the present moment without worrying about the past and future.

There are many things that you can do to overcome trust issues. Starting slow, communicating your needs, trying therapy, and learning to trust yourself can help.

A Word From Verywell

Having trust issues can be difficult, but trust-building is an essential part of any relationship, romantic or otherwise. Make trust a priority in your life—even if it's challenging to do.

If you try to build trust with someone else, you have to trust yourself first. This means being open about your feelings, opinions, thoughts, and limits. It also means being understanding when the other person makes mistakes.

Learning how to balance these two ideas will help establish healthy interpersonal relationships that are based on trust, respect, and care.

Wilkins CH. Effective engagement requires trust and being trustworthy . Med Care . 2018;56(10 Suppl 1):S6-S8. doi:10.1097/MLR.0000000000000953

Arikewuyo AO, Eluwole KK, Özad B. Influence of lack of trust on romantic relationship problems: the mediating role of partner cell phone snooping . Psychol Rep . 2021;124(1):348-365. doi:10.1177/0033294119899902

Thoresen S, Blix I, Wentzel-Larsen T, Birkeland MS. Trusting others during a pandemic: investigating potential changes in generalized trust and its relationship with pandemic-related experiences and worry . Front Psychol . 2021;12:698519. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.698519

Van Lange PAM. Generalized trust: four lessons from genetics and culture . Curr Dir Psychol Sci . 2015;24(1):71-76. doi:10.1177/0963721414552473

Reimann M, Schilke O, Cook KS. Trust is heritable, whereas distrust is not . Proc Natl Acad Sci . 2017;114(27):7007-7012. doi:10.1073/pnas.1617132114

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5-TR) .

Rodriguez LM, DiBello AM, Øverup CS, Neighbors C. The price of distrust: trust, anxious attachment, jealousy, and partner abuse . Partner Abuse . 2015;6(3):298-319. doi:10.1891/1946-6560.6.3.298

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

Leading with Trust

Leadership begins with trust.

After your trust has been broken – 5 ways to avoid a victim mentality.

What’s important is your response after trust has been broken. You have two choices: victimization or resiliency. Victimization is characterized by an attitude of powerlessness, blaming others for the negative situations in your life, believing that everyone else has it better than you, and a constant seeking of sympathy for your lot in life. Either you’ve experienced it yourself or you’ve seen it others. It’s characterized by statements like: Why me? People can’t be trusted. I can’t change my circumstances. Why is everyone against me? It’s not my fault.

The other response to having your trust broken is resiliency. Resilient people choose to embrace the power they have to make the best of their circumstances, to learn from their experiences, grow in maturity, and move toward healthier and more satisfying places in life. Statements that reflect the attitudes and beliefs of resilient people include: This will make me stronger. This hurts but I’ll deal with it and move on. I’ve got so many good things to look forward to in life. I’m not going to let this get me down.

Here are five concrete ways you can move from having a victim mentality toward an attitude of resiliency:

1. Own your choices – You can’t control everything that happens in your life, but you can control how you respond. You can choose to wallow in self-pity, depression, anger, or resentment, or you can choose to grant forgiveness, experience healing, and seek growth moving forward.

2. Quit obsessing on “why?” – Rather than asking “Why me?” when someone violates your trust, ask yourself “What can I learn?” Many times it will be impossible to know exactly why something happened the way it did, but you can always choose to view challenging circumstances in life as learning opportunities. Did you trust this person too quickly? Did you miss previous warning signs about this person’s trustworthiness? What will you do differently in the future?

3. Forgive and seek forgiveness – Years ago I heard a saying about forgiveness that has stuck with me:

Forgiveness is letting go of all hopes for a better past.

We often refuse to grant forgiveness because we feel like it’s letting people off the hook for their transgressions. In reality, choosing to not grant forgiveness is like taking poison and waiting for the other person to die. It does nothing but hurt ourselves and hold us back from healing and moving forward. If you are the one who has broken trust or played a part in the situation, do what you can to seek forgiveness and bring healing to the relationship. It’s the right thing to do.

4. Count your blessings – People with a victim mentality often gravitate toward absolute thinking. Words like never and always frequent their conversations: I’ll never find someone I can trust. People always let me down. Life is rarely so absolute and one way to remind ourselves of that truth is to count our blessings. In the big scheme of life, most of us have many more positive things in our lives than negative. Make a list of all the things you’re grateful for and you’ll realize how fortunate you really are.

5. Focus forward – Victims tend to live in the past, constantly focused on the negative things that have happened to them until this becomes their daily reality. Resilient people keep focused on moving forward. They don’t let circumstances hold them back, and they embrace whatever power they have to learn, grow, and take hold of all the good that life has to offer.

Having someone break your trust, particularly if it’s a serious betrayal, can be one of the most painful experiences in life. The easy path is to let it take you down the road of victimization where everyone and everything else becomes responsible for all the pain you encounter. The harder path is resiliency, choosing to acknowledge the pain, process it, deal with it, learn from it, and move on toward healing and growth.

Feel free to share your comments about how you’ve chosen resiliency over victimization. I’d love to learn from your wisdom.

by @RandyConley

- Share on Tumblr

60 Comments

Posted on May 25, 2014 by Randy Conley

Category: Accountability , Forgiveness , Power , Relationships , Repairing Trust , Trust

60 Comments on “ After Your Trust Has Been Broken – 5 Ways to Avoid a Victim Mentality ”

Pingback: After Your Trust Has Been Broken - 5 Ways to Av...

E+R=O… Events + Response = Outcome (via W. Clement Stone).

The only thing in this equation we have 100 percent control over is our response and that’s what changes an outcome. Really fits well with your first point.

I like that formula Kent! Our response has a dramatic effect on the outcome of our life events.

Thanks for sharing your insights,

I like the equation. I was married for 34 years to a narcesstic man. I cannot change the events that have taken place and my response was always trying to leave but then going back which created the same outcome of broken trust. A year ago I changed the response by getting a divorce which changed my outcome. Trying now to end being a victim by healing and gaining growth. Betterlife12,2016

I respect your courage Angelia. My mom has made a different decision, having stuck with my NPD dad 40+ years now. It’s difficult for her, quite a questionable relationship really. I, on the other hand, broke up with my very much self-centered girlfriend recently; it’s like cutting off a limb but I know it must be done in order for me to thrive.

Actually one girl in my building, she was our close friend and we all hoped that she would never break our trust. But because of one girl who possessed her, she broke and my friends fought really bad. Trust is the only thing in which you can believe that person unless no problem. I really don’t know what to do.

Thank you! Truth here.

Thanks Rhonda!

Pingback: Five Blogs – 29 May 2014 | 5blogs

Pingback: Leadership Development Carnival: June 2014 Edition

Pingback: TGIF – Fri June 05 | up with marriage

Pingback: Our Dark, Twisted, Secret Relationship With Failure - Bidsketch

Been dealing with some broken trust issues recently that have affected me pretty deeply. This is the first article that actually makes sense and strikes a chord on how to progress forward. As always, things are easier said than done and I’m not sure I’ll be able to effectively implement all these things off the bat… But it’s good to have a concrete list / set of tools so to speak that I can refer back to.

Hello Lehel,

I’m sorry that you’re having to deal with broken trust, but I’m thankful you’ve found some help through my article. Best wishes as you move forward with your plan.

What the article states is absolutely true as I also experienced a serious state of distrust and betrayal. I first choose to be victimized which is the easier way and found out it was very difficult for me to live my life. Everyday would go like hell for me thinking about the same instances over and over again. Then I chose to chances my approach and started feeling much better as I started to think patient and changed my approach. It was very difficult to change my mindset as i trained my mind to be victimized but later with persistence I tried to change and once it happened I realized the true potential it had. Thanks

Hello Vignesh,

Thank you for sharing your experiences. My best to you.

Pingback: When Family Trust is Broken -

I am currently working through having someone I love break trust, and it is not the first time. What helps me is to stop rehearsing in my mind over and over what the person did. Rehearsing it over and over is like reliving it over and over again. I choose to be free. I do not have to be a victim.

That is true wisdom Grice. Thanks for sharing your experience.

This has been very helpful thankyou . Reading articles like this is definitely helping me process my current situation . I am finding it very difficult to forgive and move forward as everytime we try to build our relationship , there is yet again another betrayal of trust . It’s hard to know when to keep trying and when to walk away.

Hi Elly. Thanks for sharing your thoughts.

It can be hard to move forward, especially when your radar is attuned to any potential slight that may feel like another betrayal.

I encourage you to trust smartly by taking small steps. Extend your trust in stages as people prove to be trustworthy.

Best regards,

Thanks Randy. I’m dealing with a situation in which a long term close friend lied to me about a mutual business deal. It is my perception that he was very sneaky and underhanded about the whole thing. I feel like I need to meet with him and tell him what I think happened and what bothered me about it and listen to his response. I fear that nothing he will say will be good enough for me to grant forgiveness. I want him to feel my pain and grasp the depths to which he hurt me. I know this probably serves no purpose. Is this victim mentality?

I don’t think that is having a victim mentality. I think it is an attempt to explain the seriousness of how this impacted you.

Best of luck to you.

Thank you for taking the time to share and help others.

I do have a question if I may. I have been living the victim mentality. I see by repeat thought patterns and a roller coaster of emotions welling up within me with every thought. I too have had repeat offenders in my life and began turning it around on myself. My question is, how do I know when it is their real offense of breaking trust, or when it is my lifetime of broken trust and the emotions, rearing its ugly head? Have I become so scared and insecure that I am seeing trust issues everywhere? I no longer trust my own judgment, which makes things difficult. As he says it is now my insecurities, despite evidence of the broken trust. Is it just crazy making to shift the focus off of him? How do I trust….myself, let alone him?

Hi Marie. Thank you for the honesty and vulnerability of your message.

I recommend you take a look at some of the articles on my website that discuss the ABCD Trust Model. You can use that model to assess someone’s behavior to determine if he/she is demonstrating trustworthiness or not. Try to focus on just the person’s behavior, not your emotions or what you think their intent may or may not be. The proof will be in the pudding, so to speak, to see if someone is trustworthy by the track record of their behavior.

Best wishes,

Reblogged this on tomiwhensu .