Drawing Connections

Drawing in contemporary art, spring 2017, nature as art, by joseph mangano.

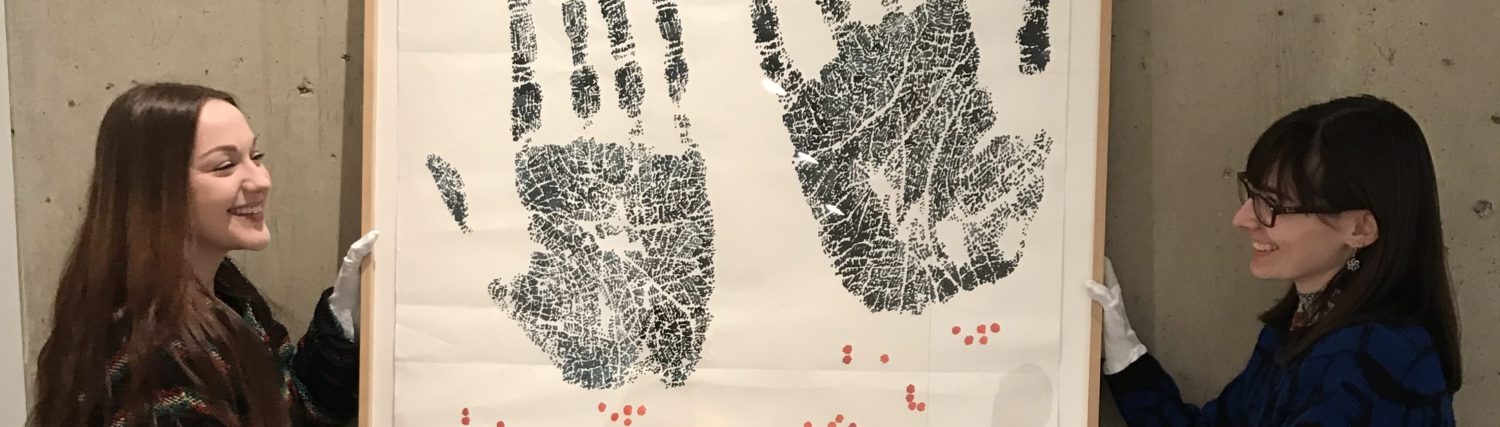

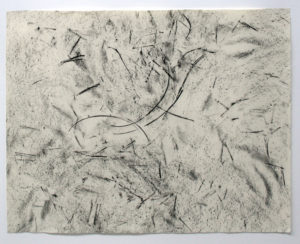

Alan Sonfist, American (b. 1946), Earth Mapping of New York City , 1965. Charcoal on paper, 19 in x 22 in. University Museum of Contemporary Art, University of Massachusetts, Amherst. Purchased with funds from Alumni Association, UM 1986.67.

Historically, drawing has been used mostly as a teaching tool and a preliminary step to develop ideas before completing a painting. With the rise of Modernism in the 20th century, drawing evolved to become its own medium for artists to express themselves. In the University of Massachusetts’s Contemporary Art Museum exhibition Body Language , viewers had the privilege to encounter different expressions of what a drawing could be in the categories of “Looking,” “Touching,” and “Feeling.” These diverse drawings opened the mind to the broad range of materials and functions of drawing. In particular, a drawing by Alan Sonfist titled Earth Mapping of New York City stood out to me among the rest. It appears to be a tracing of pine needles and natural objects found on the ground. I became fascinated with the transformation that took place when this everyday, natural pattern found on the ground was transferred into the context of art. As this interest peaked my curiosity, I started to research how artists have interacted with nature and used it as a primary source for their artworks. By considering Alan Sonfist and the works of other Land artists, I came to the conclusion that nature can be represented as a form of art on its own through the inclusion of pattern and interactive experience.

In the history of art, landscapes have proved the most enduring of artistic inspirations aside from the human figure. Only in this century has the enthusiasm for its depiction lessened due to the the multitude of technological developments that have led to a revival of abstract art. As Jacques Ellul states in his Remarks on Technology and Art :

Technology influences everything and has indeed become the chief determinant not only of man’s habitat but also of his history [….] Today art has two main orientations, the first a direct reflection of the increasing role of technology, the second a sort of explosive reaction against the rigor of technological thinking.¹

I believe a major reaction against technology has defined the movement known as Land Art, also referred to as “Earth art, “Earthworks” or “Environmental Art.” Land Art first gained popularity in the United States in the 1960’s and 70’s in response to the cultural turbulence and social unrest of the late 1960s. In order to really inspire people to feel compelled to conserve nature, a more public approach was needed. Rather than representing nature with paint on canvas or the welding of steel, a handful of artists chose to enter the landscape itself and work with its materials directly. Land Art developed out of conceptual practices in which artists started to make interventions into everyday life. These new earthworks did not depict the landscape so much as engage with it. The first works of this kind were created by Michael Heizer, Robert Smithson, Walter De Maria, Robert Morris, and Alan Sonfist. These works distinguished themselves from other forms of sculpture due to their physical presence within the landscape.² Most of these works are also inextricably bound to their sites, creating a special relationship, which in turn becomes the primary content. However, since Land Art can simply be seen as a presentation of nature, what is it about nature that can be translated into the context of art?

Similar to paintings and drawings, nature provides the viewer with a pattern of similar forms that create a composition. Alan Sonfist’s Earth Mapping of New York City is a charcoal drawing that was completed in 1965. This artwork completely transcends the traditional definitions of drawing in its representation of the trace and the mark. A trace is something inscribed by the artist’s direct physical presence, while a mark is a sign placed with deliberate intention. Earth Mapping of New York City exists as both a trace and a mark. The drawing is a rubbing of pine needles and dirt that suggests the composition of the New York City landscape long before it was inhabited. However upon further examination, the drawing transforms into a landscape with its suggestion of depth, mountains, and even animals or figures in action. The possibility of seeing objects and pictures within this abstracted natural composition is what originally fascinated me in the drawing. If this drawing were still laying flat on the ground where Alan Sonfist traced over the surface, I would most likely just see the overall appearance of marks making up the ground. When this drawing is hung on a gallery wall, however, the bold and active strokes begin to mix with the stain-like shadows and smaller dots to create the illusion of a landscape with possible figures.

The possibility of seeing imagery that is not really there is explained by the concept of “pareidolia”. Pareidolia is “a psychological phenomenon in which the mind responds to a stimulus (an image or a sound) by perceiving a familiar pattern where none exists.” Pareidolia was used as a tool by artists such as Leonardo Da Vinci in the Renaissance and Alexander Cozens in the 18th century, both of whom used stains and natural occurring patterns to make pictures. In Da Vinci’s notebook “Precepts of the Painter,” there is a section included titled “A Way to Stimulate and Arouse the Mind to Various Inventions.” Here, Leonardo Da Vinci states:

If you look at any walls spotted with various stains or with a mixture of different kinds of stones, if you are about to invent some scene you will be able to see in it a resemblance to various different landscapes adorned with mountains, rivers, rocks, trees, plains, wide valleys and various groups of hills. You will also be able to see divers combats and figures in quick movement, and strange expressions of faces, and outlandish costumes, and an infinite number of things which you can then reduce into separate well-conceived forms.

Leonardo understands that this new device for painting may appear “trivial and ludicrous” but is truly a vital tool in arousing the mind to various inventions.

Aside from Leonardo Da Vinci, later artists such as Alexander Cozens and Thomas Gainsborough, another 18th-century English landscape painter, used the effect of pareidolia in nature to invent works of art. Like these artists, I believe that pareidolia can help us understand a pattern and how it makes feel. This understanding can be important in deciding on the types of strokes and marks that you choose to render a scene or capture an emotion. The ability to see different forms and imagery adds an interactive component to nature where viewers can pull out individual perceptions of what lies in front of them, Aside from arousing new inventions for natural compositions, patterns in nature can also be directly translated as they appear. The idea of referencing patterns in nature dates all the way back to biblical times. In Exodus 25, a book in the Old Testament, God gives directions to the prophet Moses on how to build the Ark of the Covenant and the Tabernacle, with the specific instructions to “be sure that you make everything according to the pattern I have shown you here on the mountain.”³ Beyond patterns, this individual, psychological experience viewers gain is what makes nature a truly astonishing work of art.

Continuing with experience, strong pieces of art often evoke an emotion, bring to light a memory, or change the way you perceive something. For example, when I view works by Claude Monet I am always hit with a sense of nostalgia and familiarity with the landscape depicted as if I have been there in a previous life. This action of receiving a feeling and being put into a different emotional state is what I think makes great art. This one of the strenghts of nature over other forms of art. Ralph Waldo Emerson describes this personal experience with nature in his essay titled “Nature.” The Transcendentalist writer brings up the idea that a true understanding of the self can be achieved by going out into nature and leaving behind all preoccupying activities as well as society. Emerson believes that when a man gazes at the stars, he becomes aware of his own separateness from the material world resulting in an uninhibited way of thinking.? Like Emerson, I believe that nature can serve as an escape from the material world and can provide artists with a space to reflect on the world around them without the influence over others. This effect that nature can bring to the viewer is why Land Art is especially important today. For example, New York City’s famous “Times Square” is essentially a square intersection filled with over 230 billboards and advertisements. The advertising and influence of big corporations are posted all around Manhattan and constantly invade the minds of pedestrians.

Thankfully, a source of nature can be found in a Land Art work in lower Manhattan. In 1965, Alan Sonfist created the environmental public sculpture titled Time Landscape . This sculpture is an area of plants and trees that recreates the natural heritage of Manhattan long before it was filled with skyscrapers and taxis. In Sonfist’s essay “Natural Phenomena as Public Monuments,” the artist explains that with Time Landscape he hopes to create a space for reflection and heightened sensitivity in a “cluttered and overly rationalized modern world” that would ideally stimulate an altered sense of one’s place within the world.? While critics might view Time Landscape as a simple garden or urban forest, the idea of using this natural space as a source for “reflection” transforms the traditional garden into an immersive experience. I believe the experience that Sonfist’s Time Landscape provides is an integral attempt to reconnect humans to nature.

Today we live in society where advertisements, political opinions, and worldly views are constantly being pushed into our mind by force. According to digital marketing experts, it is estimated that most Americans are exposed to around 4,000 to 10,000 advertisements each day.? A study at Oberlin College also revealed that the average American child is able to identify over 1,000 corporate logos but only can recognize about a dozen of the plants or animals found in their neighborhood.? Our society’s loss of connection within nature is creating a population controlled by media and opinions of corporations instead of living out our own personal discoveries and intuitions.

In conclusion, the patterns and personal experiences that viewers achieve when looking at nature justify nature as a direct material of art. While nature can sometimes seem only an aesthetically pleasing source for art, the interactive experience of reflection and individual thought is what pushes nature beyond its concrete existence into the realm of art. More importantly, using nature as a form of art can help compel society to conserve and revitalize our connection with the natural world.

1) Ellul, Jacques . “Remarks on Art and Technology.” Social Research , 1979, 805-33.

2) Beardsley, John. Earthworks and beyond contemporary art in the landscape . New York: Abbeville Press, 1989.

3) Exodus 25:40, Old Testament of the Bible.

4) Emerson, Ralph Waldo – Essays – “Nature” (1844). 1844. Accessed May 02, 2017. http://transcendentalism-legacy.tamu.edu/authors/emerson/essays/nature1844.html.

5) Sonfist, Alan. Alan Sonfist: Natural Phenomena As Public Monuments . Purchase, NY: Neuberger Museum, 1978.

6) Marshall, Ron. “Advertising Campaigns.” Http://www.redcrowmarketing.com/2015/09/10/many-ads.

7) “Loving Children: A Design Problem, David Orr.” Accessed May 02, 2017. http://designshare.com/research/orr/loving_children.htm.

- ← Leon Polk Smith: Conjuring Curves

- Land Art: Seeking The Right Approach →

Advertisement

Supported by

To Draw Nature, Pick Up a Pencil and Really Look

With a few basic tips you can begin to draw the creatures around you, and remember the joy they bring.

- Share full article

By Clare Walker Leslie

If you enjoy watching birds floating by or chipmunks scampering across your lawn, why not have a go at drawing them to remember what gave you some cheer? With a few basic tips, you can begin making simple drawings. Don’t worry about how good they are. Enjoy that you are learning to see nature. As the writer and naturalist Rachel Carson said, “Those who notice nature will never be bored.”

All you need is a pencil and paper. (You can start in the space at below right.) If your desired subject is not right in front of you, or moves too quickly for you to capture, a field guide or a clear photo from a magazine or online search will do. Choose an image that is in profile, which makes it easier to see your subject’s shape. Keep your drawing small, no more than four inches to begin.

How to begin: Find five or 10 minutes in your day to slow down and be with nature. What would you like to draw, to learn more about? It could be anything — a butterfly, a chickadee, an oak tree, even a green pepper or an apple.

Look very carefully at your subject, figuring out its basic shape. How did it grow and where? How does it live? Remember, this is a stress reliever, not a stress creator. Getting to know your animal is the important thing. Try doing sketches of what you see directly, mostly looking at the animal and not at your paper.

Don’t take more than 15 minutes. If you think folks won’t know what you drew, label it and jot down the date so you remember when you drew it. And if you want to get better, keep drawing.

To help you get started, here are some tips:

1. All mammals can be drawn beginning with three basic circles for hip, belly and shoulder.

2. Once you have those, you can sketch in the other parts — the neck, head, tail, legs and the beginning details.

3. When you have your proportions worked out, add the details of the fur, eye, nose, etc. to create your finished drawing.

1. All birds are drawn beginning with two basic circles for the body and head, their relative size determined by the bird’s anatomy.

2. Add the tail, wing, bit of neck, legs.

3. When you have your proportions worked out, add details of feathers, beak, toes, eye to create your finished drawing.

Whatever kind of animal you are drawing, it’s important to position the eye correctly and to put in a highlight so that it doesn’t look dead. In birds, make sure to draw the upper and lower bill so that the bill can open.

1. Find the basic geometric shape of your flower. Here, the daffodil has a six- pointed star shape as there are six petals.

2. Draw the petals around your star, the center trumpet, the stamen and pistil inside, and then the veins of the petals plus stem (and maybe) leaf beside.

3. In profile, the flower shape is no longer round but oval as it is foreshortened.

Clare Walker Leslie is an internationally known wildlife artist, author, and educator. She has written 13 books on drawing and connecting with nature.

Nature Essay for Students and Children

500+ words nature essay.

Nature is an important and integral part of mankind. It is one of the greatest blessings for human life; however, nowadays humans fail to recognize it as one. Nature has been an inspiration for numerous poets, writers, artists and more of yesteryears. This remarkable creation inspired them to write poems and stories in the glory of it. They truly valued nature which reflects in their works even today. Essentially, nature is everything we are surrounded by like the water we drink, the air we breathe, the sun we soak in, the birds we hear chirping, the moon we gaze at and more. Above all, it is rich and vibrant and consists of both living and non-living things. Therefore, people of the modern age should also learn something from people of yesteryear and start valuing nature before it gets too late.

Significance of Nature

Nature has been in existence long before humans and ever since it has taken care of mankind and nourished it forever. In other words, it offers us a protective layer which guards us against all kinds of damages and harms. Survival of mankind without nature is impossible and humans need to understand that.

If nature has the ability to protect us, it is also powerful enough to destroy the entire mankind. Every form of nature, for instance, the plants , animals , rivers, mountains, moon, and more holds equal significance for us. Absence of one element is enough to cause a catastrophe in the functioning of human life.

We fulfill our healthy lifestyle by eating and drinking healthy, which nature gives us. Similarly, it provides us with water and food that enables us to do so. Rainfall and sunshine, the two most important elements to survive are derived from nature itself.

Further, the air we breathe and the wood we use for various purposes are a gift of nature only. But, with technological advancements, people are not paying attention to nature. The need to conserve and balance the natural assets is rising day by day which requires immediate attention.

Get the huge list of more than 500 Essay Topics and Ideas

Conservation of Nature

In order to conserve nature, we must take drastic steps right away to prevent any further damage. The most important step is to prevent deforestation at all levels. Cutting down of trees has serious consequences in different spheres. It can cause soil erosion easily and also bring a decline in rainfall on a major level.

Polluting ocean water must be strictly prohibited by all industries straightaway as it causes a lot of water shortage. The excessive use of automobiles, AC’s and ovens emit a lot of Chlorofluorocarbons’ which depletes the ozone layer. This, in turn, causes global warming which causes thermal expansion and melting of glaciers.

Therefore, we should avoid personal use of the vehicle when we can, switch to public transport and carpooling. We must invest in solar energy giving a chance for the natural resources to replenish.

In conclusion, nature has a powerful transformative power which is responsible for the functioning of life on earth. It is essential for mankind to flourish so it is our duty to conserve it for our future generations. We must stop the selfish activities and try our best to preserve the natural resources so life can forever be nourished on earth.

{ “@context”: “https://schema.org”, “@type”: “FAQPage”, “mainEntity”: [ { “@type”: “Question”, “name”: “Why is nature important?”, “acceptedAnswer”: { “@type”: “Answer”, “text”: “Nature is an essential part of our lives. It is important as it helps in the functioning of human life and gives us natural resources to lead a healthy life.” } }, { “@type”: “Question”, “name”: “How can we conserve nature?”, “acceptedAnswer”: { “@type”: “Answer”, “text”: “We can take different steps to conserve nature like stopping the cutting down of trees. We must not use automobiles excessively and take public transport instead. Further, we must not pollute our ocean and river water.” } } ] }

Customize your course in 30 seconds

Which class are you in.

- Travelling Essay

- Picnic Essay

- Our Country Essay

- My Parents Essay

- Essay on Favourite Personality

- Essay on Memorable Day of My Life

- Essay on Knowledge is Power

- Essay on Gurpurab

- Essay on My Favourite Season

- Essay on Types of Sports

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Download the App

Humans in Nature

The Importance of Nature in Art

People use art to help their well-being but also to draw attention to societal changes and issues. The combination of art and nature allows people to explore the natural world, create more profound meaning for themselves, and connect people through understanding and viewing their artwork. This article will discuss the importance of integrating art and nature and how various artists used nature to inspire them.

Throughout time, artists have used nature as a muse or motivation for creating different forms of art. Nature can provide endless forms of inspiration, and it can be a critical theme in many forms of artwork. Henry Matisse said, “An artist must possess nature. He must identify himself with her rhythm, by efforts that will prepare the mastery which will later enable him to express himself in his own language.” Artists use nature to express themselves but also to understand their work and themselves on a deeper level. To do this, artists may even use nature within their creations, such as wood, clay, water, and graphite, which are all-natural mediums.

There has also been some research done on the importance of art and nature to the well-being of others. Thomson et al. (2020) found that creative green prescription programs, which combine arts- and nature-based activities, can significantly impact the psychosocial well-being of adult mental health service clients. They recommended that museums with parks and gardens blend programs to incorporate nature, art, and well-being. Kang et al. (2021) found that nature-cased group art therapy positively affects siblings of children with disabilities. This type of art therapy increased their resistance to disease and their self-esteem while alleviating stress.

The Jan Van Eyck Academy in the Netherlands has opened a lab for artists to do their own nature research. They created a facility to support woodworking, printmaking, photography, video, and metalwork while allowing artists to explore their work and relationship with nature. This lab gives the artists a chance to consider nature in various ways, including its relation to ecological and landscape development issues to begin to bridge a gap between humankind, nature, and art. There needs to be more scientific research on the importance of nature and art; however, we see that artists are already beginning to research how nature affects their work and overall mindset.

How have artists used nature in their work?

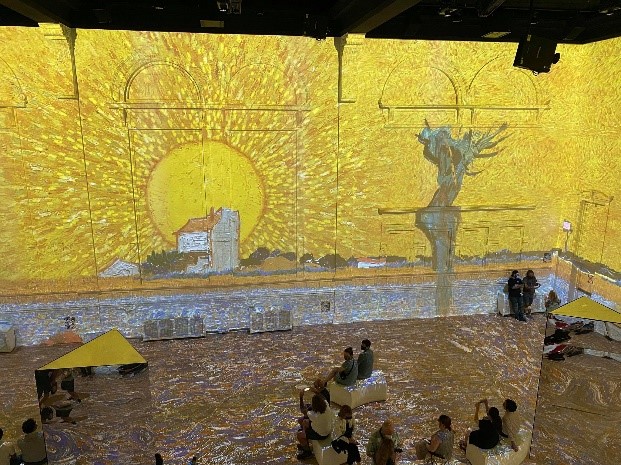

Renowned artist Vincent van Gogh, was able to bring aspects of nature to life in his paintings. His work has allowed people to understand nature in different forms and bring people together. A recent exhibit of his work brought people together for a visual and thrilling experience.

Nature also inspires modern artists, such as Mary Iverson , who draws inspiration from the natural beauty around her. Her paintings offer a contemporary spin on traditional landscape art, and she uses monuments, national parks, and societal issues (like climate change) as inspiration. She began addressing climate change in her art because she wanted to combine her environmental activism and painting interests.

Another modern artist, Miranda Lloyd , creates contemporary abstract nature art, such as trees, birds, and other naturalistic nature scenes. She uses inspiration from her own backyard and paints many scenes that are inspired by the sea. Miranda is an excellent example of how you can be inspired by nature within and outside of your home.

Additionally, items from nature can be used to create new forms of art. Renowned artist Daniel Popper creates larger-than-life sculptures, and many of them are designed with forms of nature. He currently has an outdoor exhibit at the Morton Arboretum in Lisle, IL, called “Human+Nature.” This exhibit connects people and trees through sculptures and other forms of art. As stated on the Morton Arboretum’s website, “People rely on trees for clean air to breathe, shade to cool, and beauty that can bring joy and relaxation, among many other benefits. In turn, trees need people to care for them to thrive and share their benefits, especially in a changing climate.” Individuals can begin to reimagine their relationships with trees as they explore these large-scale artworks. Below are a few pictures from his exhibit!

In our next article about nature and art, we will take a deeper dive into how art can create different forms of purpose for various individuals and discuss places all over the United States that have spaces for art and nature!

https://www.culturepartnership.eu/en/article/nature-and-art

https://www.art-is-fun.com/nature-in-art

https://grist.org/living/mary-iverson-makes-climate-change-paintings-that-are-actually-cool/

https://bluethumb.com.au/blog/artists/10-best-emerging-nature-artists/

Thomson, L. J., Morse, N., Elsden, E., & Chatterjee, H. J. (2020). Art, nature and mental health: assessing the biopsychosocial effects of a ‘creative green prescription’museum programme involving horticulture, artmaking, and collections. Perspectives in public health, 140(5), 277-285.

Kang, S., Kim, H., Baek, K., (2021). Effects of nature-based group art therapy programs on stress, self-esteem and changes in electroencephalogram (EEG) in non-disabled siblings of children with disabilities. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18

Share this:

2 thoughts on “ the importance of nature in art ”.

- Pingback: 219 Easy Drawing Ideas: How-To Guides and Expert Tips - Full Bloom Club

Oh wow, I love knowing that artists have drawn inspiration or muse from nature to create a variety of works of art throughout history. This is great because my daughter came home from school yesterday and couldn’t stop talking about the amazing art projects her friends are doing. She’s feeling left out and really wants to join in the fun. Now, I’m considering enrolling her in a teen art class to help her build her artistic confidence and connect with peers who share her passion.

Leave a comment Cancel reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

- Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.

- Subscribe Subscribed

- Copy shortlink

- Report this content

- View post in Reader

- Manage subscriptions

- Collapse this bar

Artistic Representation of Nature Essay

One of the main qualities of visual art is that it allows people to get in touch with the surrounding physical reality through the perceptual lenses of another person’s mind – hence, making it possible for the spectators to experience the sensation of aesthetic pleasure. 1 The derived pleasure often proves particularly intense when the art piece in question is inspired by the works of nature, or when it is concerned with depicting the natural environment.

This simply could not be otherwise – nature has always served as an important source of creative inspiration for many generations of artists. The actual explanation for this has to do with the innermost essence of art, as the instrument for amplifying the pleasurable aspects of one’s ‘experience of being’. 2 When exposed to the elements, most people naturally grow to feel aesthetically overwhelmed – especially when surrounded by some breathtaking scenery. In its turn, this triggers several artistic anxieties in them – hence, prompting the affected individuals to consider creating art, or to act ‘artfully’. 3

Nevertheless, even though nature does inspire artists more or less equally, how they channel their fascination with the natural environment vary rather substantially. The most logical explanation as to why this is being the case is that just about any nature-inspired work of art is reflective of the specifics of ‘mental wiring, on the part of its creator. 4 What this means is that it is possible to experience the aesthetic thrill of observing ‘nature art’, and to gain certain insights into the innermost workings of the affiliated artist’s mentality. To substantiate the validity of this suggestion, I will discuss some nature-depicting paintings by Janaina Tschape and Katherine Del Barton.

Janaina Tschape is a German-born artist, who had spent her formative years in Brazil, and who now resides in New York. She is known for her willingness to experiment with the innovative artistic techniques, as well as for the prominent impressionist quality of many of her artworks. 5 Tschape’s painting Winter stands out as a perfect example in this respect.

Even a glance at this artwork will reveal that by working on it, the artist was the least concerned with trying to ensure the lifelikeness of what is being depicted. Rather, she strived to provide the visualization of the whole range of her feelings, invoked by the snowy weather outside of the window. Partially, this explains a certain nebulosity of the author’s artistic representations of a cloudy sky, trees, water in the river, bridge, and some watery streaks on the window.

After all, it does take some time observing Tschape’s painting to realize that the cloud-like objects in the artwork’s upper part are indeed clouds and not the crowns of some trees, for example. This, however, is exactly what contributes towards strengthening the impression that the depicted objects are in a state of some elusive motion. The unmistakably ‘cold’ palette of the featured colors does its work helping to establish a proper perceptual mood in onlookers. 6

Tschape did not merely strive to ‘catch the moment’ while creating this painting, but also to present its discursive motifs being inseparable from her sense of individuality – hence, the earlier mentioned impressionist appearance of the analyzed art piece. In a certain sense, the artist’s personality is being objectified within the compositional elements of the painting, which implies that Winter is as much about the author herself, as it is about the portrayal of the snowy landscape in the distance. Essentially the same applies to Tschape’s other painting Clouds .

As we can see in it, the depicted clouds resemble the real ones only formally. However, while exposed to this painting, one is likely to experience the realistic sensation of standing under the cloudy sky. Just as it is the case with the earlier mentioned painting , Clouds presents viewers with the strongly personalized artistic account of nature – hence, the presence of bright yellow color amidst the otherwise ‘cold’ ones. In the painting, they codify the hidden ‘clusters of meaning’, which the audience members are expected to be able to ‘decipher’. 7 It is namely while ‘deciphering’ the artwork’s implicit semiotics that viewers can experience the feeling of aesthetic excitement. This excitement will prove particularly intense in those individuals who know a thing or two about the theory of art.

In light of what has been said earlier, it will be appropriate to suggest that Tschape tends to use the images of nature in her works as the vehicles for promoting her own highly subjective understanding of what accounts for the effects of one’s exposure to the surrounding natural environment on the formation of his or her attitudes towards life. Thus, it will only be logical to assume that Tschape’s interrelationship with nature is marked by the artist’s unconscious tendency to think of nature’s expressions as such that serve the purpose of helping her become increasingly enlightened, as to what accounts for human life.

For Tschape, nature is much more of an abstract idea of some omnipresent potency than merely the object of one’s aesthetic admiration. This provides us with a rationale to suggest that both paintings reflect the aesthetic workings of Tschape’s ‘Faustian’ psyche 8 – the artist regards nature to be the actual key to discovering the innate principles of how the universe operates, even without being aware of it consciously. Therefore, there is nothing too odd about the apparent whimsicalness of the artist’s style – it is yet another indication of Tschape’s innate predisposition towards trying to achieve some sort of intellectual enlightenment by the mean of subjecting the surrounding nature to her emotionally driven aesthetic inquiry.

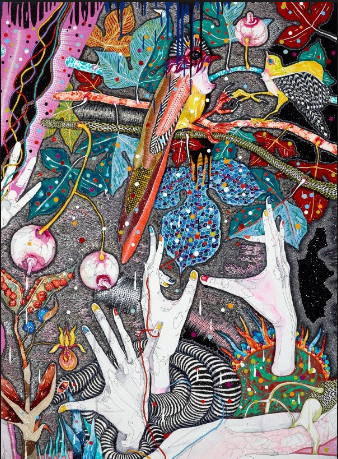

The artworks of Del Kathryn Barton (an Australian artist, who lives in Sydney 9 ) are concerned with the deployment of the entirely different methodological approach to depicting nature, as compared to that of Tschape. The most notable difference in this regard is that whereas the works of the latter connote ‘motion’, Barton’s paintings are best described as ‘motionless’, in the representational sense of this word.

Partially, this can be explained by the reference being made to the technical details of how Barton’s artistic masterpieces come into being, “Her (Barton’s) paintings show an obsession with meticulous mark-making; from minuscule dotting to veins on leaves and strands of hair. Being that the production process for her larger paintings is extremely labor-intensive”. 10 To exemplify that this is indeed the case, we can refer to the artist’s painting Animals , as seen below.

What immediately comes into one’s eye, regarding the subtleties of Barton’s artistic style, is that they are strongly ornamental. That is, the author made a deliberate point of using bright colors to increase the anthropomorphic appeal of the depicted animals – the aesthetic technique commonly used by the Aboriginal people in Australia. 11 The impression that Barton’s artwork was indeed inspired by the legacy of Aboriginal art is strengthened even further by the visual and thematic idealization of nature, 12 achieved through the application of the tiny bits of paint to the canvas throughout its entirety.

Given the sheer amount of time, required to create artworks like Animals , the discussed painting cannot be deemed quite as spontaneous and ‘moody’, as it is the case with Tschape’s Winter and Clouds . At the same time, however, there are a few similarities between the aesthetic strategies of both artists. The most distinctive of them is that, just as it appears to be the case with Tschape, Barton tends to treat the emanations of nature as being highly symbolical and allegorical. The artist’s painting Birds can be considered as yet another proof in this regard.

That is, nature for Barton is more of an abstract idea than something that can be experienced and enjoyed as a ‘thing in itself’. While observing Barton’s art, people are also required to solve a mental puzzle as to what accounts for the proper approach to interpreting this art’s symbolical denotations. Thanks to the artist, there is nothing too challenging about the task. The pale coloring of human hands (one of the compositional elements in both Barton’s paintings), as well as how they are portrayed, implies that Barton uses her art as a medium for channeling the message of environmental friendliness to people. According to this message, people must aspire to live in perfect harmony with nature.

There is, however, even more to it. As it can be confirmed regarding the mentioned paintings by Barton, just about every depicted object in them is shown visually interlocking with the rest, which results in increasing the measure of both paintings’ holistic integrity. This specific effect is brought about by the fact that, despite the elaborative detailing of each component in Barton’s paintings, all of the featured elements (including the tiniest ones) are perceived as the integral parts of a whole.

Therefore, there is nothing accidental about the presence of Aboriginal motifs in Barton’s artworks – the specifics of the artist’s conceptualization of nature correlates well with the provisions of Non-Western ‘perceptual holism’, which stands in opposition to the Western (object-oriented) outlook on the natural environment and one’s place in it. 13

Thus, there is indeed a good reason to believe that the significance of a particular artistic representation of nature should be discussed in conjunction with what accounts for the affiliated artist’s psycho-cognitive predispositions, which define the qualitative aspects of this person’s aesthetic stance. This concluding remark is fully consistent with the paper’s initial thesis. There can be no ‘pure art’ 14 – just about every form of artistic expression is symptomatic of its originator’s psychological predilection – just as it was implied in the paper’s introductory part.

One of this conclusion’s possible implications is that, as time goes on, the positivist theories of art, based on the assumption that there are universally recognized ‘canons’ in the artistic domain, will continue to fall out of favor with more and more people. 15 The dialectical laws of history predetermine such an eventual development.

Bibliography

Chakravarty, Ambar. “The Neural Circuitry of Visual Artistic Production and Appreciation: A Proposition.” Annals of Indian Academy of Neurology 15, no. 2 (2012): 71-75.

Currie, Gregory. “Actual Art, Possible Art, and Art’s Definition.” The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism 68, no. 3 (2010): 235-241.

Davey, E. R. “‘Soft Framing’: A Comparative Aesthetics of Painting and Photography.” Journal of European Studies 30, no. 118 (2000): 133-155.

De Lorenzo, Catherine. “The Hang and Art History.” Journal of Art Historiography no. 13 (2015): 1-17.

Galenson, David. “The Life Cycles of Modern Artists: Theory and Implications.” Historical Methods 37, no. 3 (2004): 123-136.

Hawkins, Celeste. “ Del Kathryn Barton. ” The Art and the Curious , 2015. Web.

Leslie, Donna. “Seeing the Natural World Art & Reconciliation.” Art Monthly Australia no. 258 (2013): 30-33.

McClelland, Kenneth. “John Dewey: Aesthetic Experience and Artful Conduct Education and Culture.” Education and Culture 21, no. 2 (2005): 44-62.

Murphy, Margueritte. “Pure Art, Pure Desire: Changing Definitions of l’Art Pour l’Art from Kant to Gautier.” Studies in Romanticism 47, no. 2 (2008): 147-160.

Pearse, Emma. “Janaina Tschape.” ARTnews 104, no. 9 (2005): 184-185.

Tekiner, Deniz. “Formalist Art Criticism and the Politics of Meaning.” Social Justice 33, no. 2 (2006): 31-44.

Thomas, Daniel. “Aboriginal Art: Who Was Interested?” Journal of Art Historiography no. 4 (2011): 1-10.

Vasilenko, Ivan. “Dialogue of Cultures, Dialogue of Civilizations.” Russian Social Science Review 41, no. 2 (2000): 5-22.

Wilson, Henry. “Pleasure Palettes.” World of Interiors 30, no. 1 (2010): 58-67.

Young, Michael. “Del Kathryn Barton: Disco Darling.” Art and AsiaPacific no. 96 (2015): 68-69.

- Gregory Currie, “Actual Art, Possible Art, and Art’s Definition.” The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism 68, no. 3 (2010): 237.

- Kenneth McClelland, “John Dewey: Aesthetic Experience and Artful Conduct Education and Culture.” Education and Culture 21, no. 2 (2005): 46.

- E. R. Davey, “‘Soft Framing’: A Comparative Aesthetics of Painting and Photography.” Journal of European Studies 30, no. 118 (2000): 138.

- Ambar Chakravarty, “The Neural Circuitry of Visual Artistic Production and Appreciation: A Proposition.” Annals of Indian Academy of Neurology 15, no. 2 (2012): 72.

- Emma Pearse, “Janaina Tschape.” ARTnews, 104, no. 9 (2005):185.

- Henry Wilson, “Pleasure Palettes.” World of Interiors 30, no. 1 (2010): 65.

- David Galenson, “The Life Cycles of Modern Artists: Theory and Implications.” Historical Methods 37, no. 3 (2004): 129.

- Ivan Vasilenko, “Dialogue of Cultures, Dialogue of Civilizations.” Russian Social Science Review 41, no. 2 (2000): 10.

- Michael Young, “Del Kathryn Barton: Disco Darling.” Art and AsiaPacific 96 (2015) 68.

- Celeste Hawkins, “Del Kathryn Barton.” The Art and the Curious , 2015. Web.

- Daniel Thomas, “Aboriginal Art: Who Was Interested?” Journal of Art Historiography no. 4 (2011): 14.

- Catherine De Lorenzo, “The Hang and Art History.” Journal of Art Historiography no. 13 (2015): 5.

- Donna Leslie, “Seeing the Natural World Art & Reconciliation.” Art Monthly Australia no. 258 (2013): 32.

- Margueritte Murphy, “Pure Art, Pure Desire: Changing Definitions of l’Art Pour l’Art from Kant to Gautier.” Studies in Romanticism 47, no. 2 (2008): 147.

- Deniz Tekiner, “Formalist Art Criticism and the Politics of Meaning.” Social Justice 33, no. 2 (2006): 33.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2020, November 5). Artistic Representation of Nature. https://ivypanda.com/essays/artistic-representation-of-nature/

"Artistic Representation of Nature." IvyPanda , 5 Nov. 2020, ivypanda.com/essays/artistic-representation-of-nature/.

IvyPanda . (2020) 'Artistic Representation of Nature'. 5 November.

IvyPanda . 2020. "Artistic Representation of Nature." November 5, 2020. https://ivypanda.com/essays/artistic-representation-of-nature/.

1. IvyPanda . "Artistic Representation of Nature." November 5, 2020. https://ivypanda.com/essays/artistic-representation-of-nature/.

IvyPanda . "Artistic Representation of Nature." November 5, 2020. https://ivypanda.com/essays/artistic-representation-of-nature/.

- Barton Company Performance and Strategies

- Barton Engine Business: Financial Position & Performance

- David Barton Gym’s Marketing and Communication

- Clara Barton's Biography and Contributions to Nursing

- A Conversational Account of Clara Barton and Corrie Ten Boom

- Clara Barton’s Contributions to Nursing

- Vegetation Sampling - Barton Road

- Choir Conducting Quality Analysis

- "Double Indemnity": An Exemplary Noir Film

- Mentoring and Coaching in Management

- Mural Arts Program in Philadelphia

- Renaissance and Realism Art Periods

- Contemporary Art Practices Essay

- Public Art: the Tension between Virtual and Real Space

- Rasquache as an Art Philosophy

- Publications

- Conferences & Events

- Professional Learning

- Science Standards

- Awards & Competitions

- Daily Do Lesson Plans

- Free Resources

- American Rescue Plan

- For Preservice Teachers

- NCCSTS Case Collection

- Partner Jobs in Education

- Interactive eBooks+

- Digital Catalog

- Regional Product Representatives

- e-Newsletters

- Bestselling Books

- Latest Books

- Popular Book Series

- Prospective Authors

- Web Seminars

- Exhibits & Sponsorship

- Conference Reviewers

- National Conference • Denver 24

- Leaders Institute 2024

- National Conference • New Orleans 24

- Submit a Proposal

- Latest Resources

- Professional Learning Units & Courses

- For Districts

- Online Course Providers

- Schools & Districts

- College Professors & Students

- The Standards

- Teachers and Admin

- eCYBERMISSION

- Toshiba/NSTA ExploraVision

- Junior Science & Humanities Symposium

- Teaching Awards

- Climate Change

- Earth & Space Science

- New Science Teachers

- Early Childhood

- Middle School

- High School

- Postsecondary

- Informal Education

- Journal Articles

- Lesson Plans

- e-newsletters

- Science & Children

- Science Scope

- The Science Teacher

- Journal of College Sci. Teaching

- Connected Science Learning

- NSTA Reports

- Next-Gen Navigator

- Science Update

- Teacher Tip Tuesday

- Trans. Sci. Learning

MyNSTA Community

- My Collections

Drawing on Nature

Science Scope -- Summer 2006

Share Start a Discussion

You may also like

Journal Article

Scope on the Skies March 2024...

Excitement is building in anticipation of the total solar eclipse taking place this April 2024. During the total solar eclipse, the moon will pass bet...

We are now a decade past the release of the NGSS —an event that has shaped the way we teach science. The NGSS, with its three-dimensional approach e...

Whole group discussions are a key aspect of the NGSS because these activities are where students collectively make sense of natural phenomena. However...

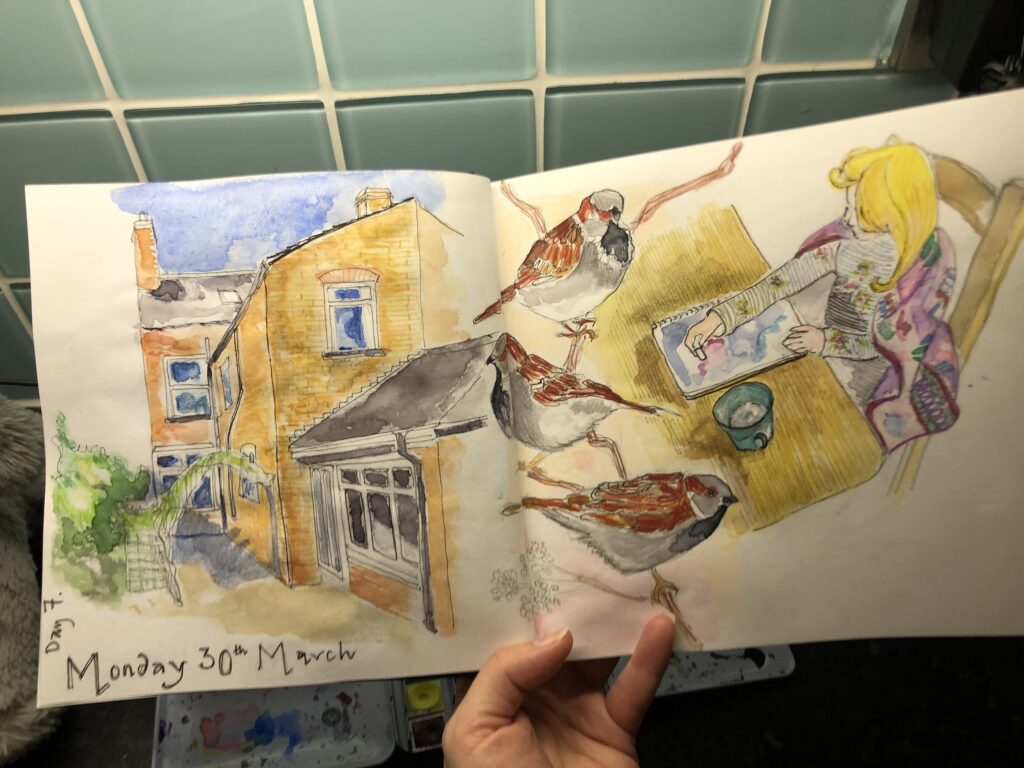

Thoughts And Ideas On Nature Sketching

Have you ever wondered where to start when nature sketching?

Firstly, how does one even begin to define it? From sweeping landscapes to the local park, animals to trees, birds to moss, the natural world provides limitless inspiration for our sketchbooks.

Without realising it, nature creeps into our daily interpretations of the world. Whether a bird sitting on your inner city garden fence, your succulent bathing in the sunshine on a window sill, or portobello mushrooms tumbling out of a brown paper bag ready for chopping, I have often dwelt on the fact that the reason I love to draw so much is that I am drawn to the very simplest of life’s pleasures. Pleasures that are rooted in the natural world.

As important as its counterpart, (urban sketching), nature sketching or rural sketching, elicits a sense of adventure akin to being on holiday, a sense of taking a break and expanding one’s horizon outwards. Perhaps we become more aware of our sense of place within the wider world as we start to capture it all on paper. I believe this is where some of the magic of drawing lies.

I think there are a variety of different techniques to employ when considering nature sketching and it starts by creating the categories you would class as “nature” based.

I have 3 main categories I use in my sketchbook that fit the nature sketching theme. They include landscapes, flora and fauna, and the birds and bees (to include the wider animal kingdom.) As you become more of a proficient artist you too many be able to hone in on the types of drawings you would categorise as nature sketching.

Table of Contents

Ideas on Nature Sketching

Are you inside or out .

Before we launch into these categories, however, there is one important factor that changes the approach you take to the sketch you want to get down on paper.

Are you inside or outside whilst you are drawing? Is the “real thing”in front of you or are you working from an image?

Apart from the fact that you may be carrying or using different equipment, sketching “en plain air” means that your sketch doesn’t need to be overwrought with too much detail. Sketching what you see, however, is no mean feat. You often have to be satisfied with plenty of mistakes because time, spectators, the weather or other factors will be contributors to the confidence with which you draw and may often be against you.

Composition becomes challenging too. You don’t have the enclosed image of a photograph to provide a frame of reference but rather a landscape around you. How do you even begin to get this down on paper?

Your sketching may become scrappy at best, as opposed to neatly laid out, a series of scrawls that you will need to learn to take pride in and use to build your confidence. But persevering with it means you fill a sketchbook consistent to your own personal outdoor sketching style.

Nature sketching outdoors will help you develop a new type of approach to your drawing that sharpens your perception skills as well as unique technique. It will be more elemental, and not as prescriptive as simply drawing in a sketchbook at home. You will be supercharged to get on with it and make the most of filling pages and over time your strokes on paper will become more efficient and true to form. The more you practice sketching outdoors the better your drawing technique will become. Your creative style will emerge too!

Sketching the natural landscape in situ, (in addition to the points mentioned above,) is also determined by the size of sketchbook you’re using.

An A5 landscape or portrait sketchbook is usually the maximum size I would stretch to if I was out and about. In my personal case, I like using hard backed square sketchbooks that can open out to accommodate a landscape view or smaller vignettes of natural sketches in and around the sketch itself. I’ve put together a sketch kit that is suited to this purpose.

A pencil, ink or micron pen as well as a small tin of watercolours to create a blush of minimal colour is really all you need.

So picture the scene.

You’re sitting and gazing at a beautiful landscape. What are the steps you need to take when getting started nature sketching?

- Start by assessing your page. Try in your mind’s eye to capture the view you want to convey. Don’t start with one element and work out from it. You’ll run out of space or fall off the page or only capture a small part of the scene. Start from the entirety of the sketch. Gauge the view in front of you. Which two points do you want to include in your sketch? What do you want to capture from left to right, top to bottom?

- In order to arrange your page, try splitting your page into thirds both vertically and horizontally. Two horizontal and vertical lines spaced equally apart to create a 9 boxed grid. Try not to evenly space your page but rather work within the framework of rectangular boxes. (You can see how I’ve marked my page in the main image of this article.)

- It’s also tempting to want to sketch in straight lines when it comes to landscapes but when you look at the view in front of you and mark it out in your 9 box grid you will find that there is nothing “straight” about it.

- Use a quick watercolour wash or scribble of colouring pencil to connote the colours and shade. Remember this is a sketch, not a full blown painting. There is a charm in keeping things minimal. You’ll get away with only focusing on one aspect of your sketch. (Like I have done with my vegetation, sketched in ink and then boldly blocked in a deep blue colour as a background.) Let your creative style peep through in your sketch.

- Finally. I tend to break up my page into boxes so that I can format my page to include a mix of images. The great outdoors is overwhelming and this technique can support you get going and force you to focus on filling your boxes with images as opposed to getting stuck and wondering what to draw. The more mini vignettes you can build into your practice the better. It also makes for an appealing, scenic sketchbook.

Flora and Fauna

I recently completed the biography of Beatrix Potter (A Life in Nature by Linda Lear.) Although famous for her children’s stories, her illustrious career got going amidst the bracken and fungi breeds of the United Kingdom. If ever there was an expert who carved her niche sketching nature, here she is. She drew prolifically daily, and her attentiveness to the detail of the natural world gained her accolades not only from the botanical world but from the scientific too.

What I learned from her when it comes to this subject area is the need to use an analytical eye as well as become good at spotting patterns. Nature sketching is all about pattern. Breaking down what seems to be complex images are really about conveying regular pattern into a series of shapes. Try a page of simple sketches of hedgerow plants for example.

If there is one thing to learn about the life of the prestigious Beatrix Potter is that her love of nature was a daily touchstone that provided the inspiration for her artistic direction and career.

“Now of all the hopeless things to draw, Beatrix wrote one late October evening in 1892, “I should think the very worst is a fine fat fungus.” p76. She was surrounded in her earlier years by naturalists and botanists, a reflection of the Victorian era where classification of all things in the natural world was the norm, especially for women. A long way from the loveable rabbit, Peter.

Putting aside our paleontological tendencies for a while, as well as the need to categorise all we draw, I’ve spent hours leafing through books of perfectly drawn foliage and plants. I spend equally as long focusing on hours of drawing within this genre as I do producing a quick sketch in my sketchbook.

I pay attention to the fauna around me, snapping pictures of odd looking grasses as well as collecting leaves that sit in hopeful piles on my art studio table.

Nothing is too odd or trivial to include as a sketch.

My preference is to quick sketch. There is never enough time to capture all I’d like in a sketchbook.

I also believe that all you need is an insatiable curiosity for the thing you are drawing.

When it comes to nature sketching, the thing I love about foliage, shrubs and grasses are how they remind me of getting back to the basics of mark making. (Hooray for the simple constructs of the natural world!) At the heart of all drawing is placing a pencil or pen on the paper and making a mark, the challenge is knowing how to do so! You can read my thoughts on mark making here.

You don’t have to be brilliant at drawing to capture the basics. And is it not fitting that these complex creations can be translated into simple lines on a page.

My top tips for sketching flora and fauna include;

- Focus on mark making. Forget what you are looking at and see it as a mix of lines. Blend fine and thick lines in your sketch. Just by altering how you choose to draw a line in your page can make a dramatic difference. Use different types of nib or pen thicknesses. My Fude pen is a great type of fountain pen as you can use many different angles to produce different textures and thickness of line. It’s a perfect portable travelling companion too.

- Less can sometimes be more. You can hint at grasses with seeds for example by keeping your strokes short and dotting the paper with spots. Don’t try to capture the whole, focus on textures and experiment with how to show their surface.

- Fill an entire page in under 5 minutes. How quickly can you get your images down on paper?

- Alongside standalone sketches, practice incorporating what you draw into larger sketches. You can even use foliage to surround sketching.

You may be interested in watching my free tutorial on trees where I show you how to break down a landscape of trees.

The Birds and the Bees

What would sketching nature be without the inclusion of the proverbial birds and bees aka the insect and animal worlds? You can fill an entire sketchbook with birds alone.

So the first thing to mention with regards to anything that moves and rarely holds still, is that you will have a challenge on your hands capturing these flighty creatures.

- In the first instance if you are drawing them live you will need to build your confidence in keeping your eyes on the bird whilst you draw. (And draw you will need to do fast!) I would recommend that you employ “gesture’ drawing in this instance. Gesture drawing can take place between 30 seconds or 30 minutes and is designed to capture the movement or shape of an object. Keep lines simple and minimal for definition and your eyes fixed to the object at all times (it will be a short time). You may even transcribe a scribble and beak in the first instance.

- Capturing birds in flight, unless you are advanced, may need the help of a camera. You can still aim to transcribe a sketch the moment you’ve snapped it.

- Try and aim for capturing animals and birds in natural habitats. For example, a bird in a garden bird bath, on an electricity line, your dog curled up asleep or a flock of sheep grazing in the fields may give you ample time to capture the scene where the subjects feel most comfortable. I captured the birds in my garden below hanging off branches. It took a few morning of watching them and working from photographs.

- Get comfortable sketching animals and birds as standalone sketches. Practice breaking them down into simple shape and adding smudges of colour.

I have only really covered some very basic approaches to sketching out in the natural world in the points above.

In summation and addition, here are a list of things to remember and to implement;

- Travel light when out and about. Keep your kit minimal, and your colours basic.

- Don’t forget to collect nature’s treasures to sketch later. Moss, shells, twigs and leaves all serve as brilliant sketch resources. You can even use a magnifying glass to capture the finer details.

- Accept that your sketching is going to look different to normal on the basis that you will have different challenges to contend with.

- Format your page in advance, break up your pages and fill with small and varied sketches to create variety and interest in your page. Allow sketches to also blend into one another.

- Pay attention to how you draw naturally. Do you implement contour drawing (controlled linear approach?) or are you more of a continuous line (done continuously and at a constant speed without lifting your hand off the paper?) Or do you prefer gestural drawing? (Looser and encompassing the whole image to work at speed?) Both lend themselves in different ways to quick sketches.

- Carry a small sketchbook with you wherever you go and some basic supplies so that you get into the habit of sketching wherever you are!

I look forward to seeing how you get on!

If you’re interested in joining the Emily’s Notebook community and gaining access to events, further resources and my free online sketch sessions, sign up here!

Examining the Relationship Between Nature and Art

One of the most remarkable artists to ever live, Henry Matisse once said: “An artist must possess Nature. He must identify himself with her rhythm, by efforts that will prepare the mastery which will later enable him to express himself in his own language.”

For as long as there has been art, artists have been enthused by nature. Apart from providing endless inspiration, many of the mediums that artists use to create their masterpieces such as wood, charcoal, clay, graphite, and water are all products from nature.

The artists of years gone by

Although Vincent van Gogh only sold one painting during his lifetime, he was in a league of his own. He had the ability to bring aspects of nature, such as simple flowers, to life in his paintings. One such a work of art, Irises, is particularly impressive with the life-force of the flowers being almost tangible. Monet is another of the world’s greatest artist who drew inspiration from nature. His series of paintings entitled Lilies is a beautiful showcase of shadows, light, and water and portray his garden in France. Monet’s flowers were one of the main focuses of his work for the latter 30 years of his life, perfectly illustrating what an immense influence the natural beauty around us can have on the imagination of an artist.

Modern artists inspired by nature

Mary Iverson both lives and works in Seattle, Washington and draws inspiration from the immense natural beauty that surrounds her. Her remarkable paintings offer a rather contemporary spin on traditional landscape art portraying the great monuments and national parks of the USA. Mary’s greatest inspiration comes from the picturesque Port of Seattle, and the Rainer, North Cascades, and Olympic National Parks. Mary’s work has been featured on the cover of Juxtapoz Magazine in 2015 and also appeared in Huffington Post, The Boston Review and Foreign Policy Magazine . She also works closely with a number of galleries in Germany, Paris, Amsterdam and Los Angeles and teaches visual art at the Skagit Valley College in Mount Vernon where she passionately shares her love for the natural world with her students.

British artist draws lifelong inspiration from the natural world

British wildlife artist Jonathan Sainsbury is known for his astonishing ability to capture the fleeting moments of the natural world. Having spent most of his life observing and drawing his various subjects, Sainsbury has become a master at using watercolor and watercolor combined with charcoal to effortlessly evoke a feeling of movement in his artwork. Apart from capturing the very essence of countless natural scenes he also draws on nature in a metaphorical way to refer to our everyday lives. Jonathan’s work can be viewed at the Wykeham Gallery in Stockbridge, the Strathearn Gallery, and the Dunkeld Art Exhibition.

Despite the world becoming more technology-driven by the minute, there are very few things that can inspire artistic brilliance quite like nature does. From a single rose petal spiralling to the ground to a mighty fish eagle swooping in on its prey, the countless faces of Mother Nature will continue to mesmerize and provide inspiration for some of the most renowned works of art the world has ever seen.

HANDMADE: a 'small village' in the middle of a big city

If you are not a fan of arts and crafts, be a fan of your own life, launch of the new series of legendary ukrainian photo project razom.ua, tracks: how art can become a tool of communication and a way of making sense of life during war, hatathon 3.0: nft edition, photo is:rael.

British Council is looking for professionals to evaluate Culture Bridges grant programme applications

Three Steps to Development of Cooperation between IT and culture in Belarus

Peter Lényi: “All that is man-made had to be designed by someone at first”

Open Call for Journalists

Question and Answer forum for K12 Students

The Joy Of Art: An Essay On My Hobby Drawing

Essay On My Hobby Drawing: Drawing is one of the most ancient forms of human expression. From cave paintings to modern art, drawing has always been an important medium for humans to convey their thoughts and emotions. Drawing as a hobby is a wonderful way to explore your creativity, reduce stress, and improve your focus. In this essay, I will share my personal experience with drawing as a hobby, discuss the benefits of drawing, and provide tips for beginners to improve their skills.

In this blog, we include the Essay On My Hobby Drawing , in 100, 200, 250, and 300 words . Also cover Essay On My Hobby Drawing for classes 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, and up to the 12th class. You can read more Essay Writing in 10 lines, and essay writing about sports, events, occasions, festivals, etc… The Essay On My Hobby Drawing is available in different languages.

Benefits Of Drawing As A Hobby

Drawing as a hobby has several benefits that go beyond the joy of creating a beautiful piece of art. Drawing can help reduce stress and anxiety by providing a meditative and relaxing activity. When we draw, we enter into a state of flow that takes our mind off our worries and focuses it on the present moment.

Drawing can also be therapeutic. Art therapy is an established form of therapy that uses art as a means of expression and healing. Drawing can help us express our emotions, thoughts, and feelings in a non-verbal way. This can be especially helpful for those who find it difficult to express themselves through words.

Another benefit of drawing is that it can improve our focus and mindfulness. When we draw, we have to pay attention to the details of what we are drawing. This requires us to be fully present in the moment, which can improve our overall mindfulness and awareness.

My Experience With Drawing

I started drawing as a hobby when I was a child. I would spend hours creating doodles and sketches in my notebook. As I got older, I continued to draw, but I never considered it to be more than just a fun pastime. It wasn’t until I started experiencing stress and anxiety in my adult life that I realized the therapeutic benefits of drawing.

Drawing has become a form of meditation for me. When I draw, I am fully immersed in the process, and my mind is free from worries and stress. Drawing has also helped me express my emotions in a non-verbal way. When I am feeling overwhelmed or anxious, I can sit down and draw, and it helps me feel more centered and calm.

Drawing Techniques And Tools

Drawing is a skill that can be improved with practice. There are several drawing techniques and materials that can help beginners improve their skills. One of the most important things for beginners is to start with simple shapes and lines. This will help you develop a steady hand and improve your control over the pencil or pen.

There are several drawing materials that beginners can use, including pencils, pens, charcoal, and pastels. Each material has its own unique qualities, and it’s important to experiment with different materials to find the ones that work best for you.

In addition to the materials, there are several drawing techniques that beginners can learn. These include shading, perspective, and composition. Learning these techniques can help beginners create more realistic and dynamic drawings.

Inspiration And Motivation

Inspiration for drawing can come from anywhere and everywhere. Some people find inspiration in nature, while others are inspired by music or literature. One of the best ways to find inspiration is to explore different art forms and styles. This can help you develop your own unique style and vision.

Motivation is also an important factor in the drawing. Like any skill, drawing requires practice and perseverance. It’s important to set goals and challenges for yourself to stay motivated. You can also find motivation by joining a community of artists or taking a drawing class.

Drawing as a hobby has several benefits that go beyond the joy of creating a beautiful piece of art. Drawing can reduce stress, improve focus and mindfulness, and be therapeutic. Learning drawing techniques and experimenting with different materials can help beginners improve their skills. Finding inspiration and staying motivated are also important factors in becoming a skilled artist. Drawing is wonderful.

Read More: My Hobby Essay

FAQ’s On Essay On My Hobby Drawing

Question 1. Why is drawing my hobby?

Answer: However, I can tell you that people have different reasons for taking up drawing as a hobby.

- Some people find drawing to be a relaxing and meditative activity that helps them reduce stress and anxiety. Others enjoy the creative process and the satisfaction of creating a beautiful piece of art. Some people use drawing as a means of expressing their emotions and thoughts in a non-verbal way.

- Drawing as a hobby can also be a way of challenging oneself and improving one’s skills. Learning new techniques and experimenting with different materials can be a fun and rewarding experience.

- Ultimately, the reasons for why drawing is your hobby are unique to you and may be influenced by your personal experiences, interests, and passions.

Question 2. How do you write a drawing essay?

Answer: Writing a drawing essay involves describing and analyzing a visual artwork, such as a painting, sculpture, or graphic design. Here are some steps to follow:

- Choose an artwork: Select an artwork that you want to write about. It’s best to choose a piece that you have seen in person, but if that’s not possible, find a high-quality image of the artwork to use as a reference.

- Observe and analyze: Look at the artwork carefully and take notes on what you see. Note the colors, shapes, lines, and textures used in the piece, as well as any patterns or motifs. Think about the overall composition of the artwork and how the various elements work together to create a visual impact.

- Research the artist and the artwork: If you’re writing a formal essay, you’ll want to research the artist and the artwork to provide context and background information. Find out when and where the artwork was created, what inspired the artist, and what artistic movements or styles influenced the piece.

- Develop a thesis statement: Your thesis statement should summarize the main point you want to make in your essay. It might be an analysis of the artwork’s meaning, an exploration of the techniques used by the artist, or a comparison of the artwork to other works in its genre.

Question 3. What is your favorite hobby and why is drawing?

Answer: Drawing can be a favorite hobby because it allows for self-expression and creativity. It can also be a relaxing and therapeutic activity that helps to reduce stress and anxiety. Furthermore, drawing can be a way to improve fine motor skills and hand-eye coordination. Additionally, with practice, it can lead to the development of a unique style and a sense of accomplishment.

Question 4. How do you mention drawing in hobbies?

Answer: If you want to mention drawing as one of your hobbies, you can do so in a variety of ways. Here are a few examples:

- “In my free time, I enjoy drawing. It’s a creative outlet that allows me to express myself and explore new ideas.”

- “One of my hobbies is drawing. I find it to be a relaxing and meditative activity that helps me unwind after a busy day.”

Question 5. How do you describe your drawing?

- Describe the subject matter: What is your drawing depicting? Is it a landscape, a portrait, a still life, or something else?

- Highlight the style: What techniques did you use in your drawing? Are there any unique features or elements that make it stand out?

- Comment on the composition: How did you arrange the elements in your drawing? Did you use any particular techniques to create balance or movement?

- Explain your intention: What message or feeling were you trying to convey with your drawing? What inspired you to create it?

Talk to our experts

1800-120-456-456

- Nature Essay

Essay About Nature

Nature refers to the interaction between the physical surroundings around us and the life within it like atmosphere, climate, natural resources, ecosystem, flora, fauna, and humans. Nature is indeed God’s precious gift to Earth. It is the primary source of all the necessities for the nourishment of all living beings on Earth. Right from the food we eat, the clothes we wear, and the house we live in is provided by nature. Nature is called ‘Mother Nature’ because just like our mother, she is always nurturing us with all our needs.

Whatever we see around us, right from the moment we step out of our house is part of nature. The trees, flowers, landscapes, insects, sunlight, breeze, everything that makes our environment so beautiful and mesmerizing are part of Nature. In short, our environment is nature. Nature has been there even before the evolution of human beings.

Importance of Nature

If not for nature then we wouldn’t be alive. The health benefits of nature for humans are incredible. The most important thing for survival given by nature is oxygen. The entire cycle of respiration is regulated by nature. The oxygen that we inhale is given by trees and the carbon dioxide we exhale is getting absorbed by trees.

The ecosystem of nature is a community in which producers (plants), consumers, and decomposers work together in their environment for survival. The natural fundamental processes like soil creation, photosynthesis, nutrient cycling, and water cycling, allow Earth to sustain life. We are dependent on these ecosystem services daily whether or not we are aware.

Nature provides us services round the clock: provisional services, regulating services, and non-material services. Provisional services include benefits extracted from nature such as food, water, natural fuels and fibres, and medicinal plants. Regulating services include regulation of natural processes that include decomposition, water purification, pollution, erosion and flood control, and also, climate regulation. Non-material services are the non-material benefits that improve the cultural development of humans such as recreation, creative inspiration from interaction with nature like art, music, architecture, and the influence of ecosystems on local and global cultures.

The interaction between humans and animals, which are a part of nature, alleviates stress, lessens pain and worries. Nature provides company and gives people a sense of purpose.

Studies and research have shown that children especially have a natural affinity with nature. Regular interaction with nature has boosted health development in children. Nature supports their physical and mental health and instills abilities to access risks as they grow.

Role and Importance of Nature

The natural cycle of our ecosystem is vital for the survival of organisms. We all should take care of all the components that make our nature complete. We should be sure not to pollute the water and air as they are gifts of Nature.

Mother nature fosters us and never harms us. Those who live close to nature are observed to be enjoying a healthy and peaceful life in comparison to those who live in urban areas. Nature gives the sound of running fresh air which revives us, sweet sounds of birds that touch our ears, and sounds of breezing waves in the ocean makes us move within.

All the great writers and poets have written about Mother Nature when they felt the exceptional beauty of nature or encountered any saddening scene of nature. Words Worth who was known as the poet of nature, has written many things in nature while being in close communion with nature and he has written many things about Nature. Nature is said to be the greatest teacher as it teaches the lessons of immortality and mortality. Staying in close contact with Nature makes our sight penetrative and broadens our vision to go through the mysteries of the planet earth. Those who are away from nature can’t understand the beauty that is held by Nature. The rise in population on planet earth is leading to a rise in consumption of natural resources. Because of increasing demands for fuels like Coal, petroleum, etc., air pollution is increasing at a rapid pace. The smoke discharged from factory units and exhaust tanks of cars is contaminating the air that we breathe. It is vital for us to plant more trees in order to reduce the effect of toxic air pollutants like Carbon monoxide, sulphur dioxide, nitrogen dioxide, etc.

Save Our Nature

Earth’s natural resources are not infinite and they cannot be replenished in a short period. The rapid increase in urbanization has used most of the resources like trees, minerals, fossil fuels, and water. Humans in their quest for a comfortable living have been using the resources of nature mindlessly. As a result, massive deforestation, resultant environmental pollution, wildlife destruction, and global warming are posing great threats to the survival of living beings.

Air that gives us oxygen to breathe is getting polluted by smoke, industrial emissions, automobile exhaust, burning of fossil fuels like coal, coke and furnace oil, and use of certain chemicals. The garbage and wastes thrown here and there cause pollution of air and land.

Sewage, organic wastage, industrial wastage, oil spillage, and chemicals pollute water. It is causing several water-borne diseases like cholera, jaundice and typhoid.

The use of pesticides and chemical fertilizers in agriculture adds to soil pollution. Due to the mindless cutting of trees and demolition of greeneries for industrialization and urbanization, the ecological balance is greatly hampered. Deforestation causes flood and soil erosion.

Earth has now become an ailing planet panting for care and nutrition for its rejuvenation. Unless mankind puts its best effort to save nature from these recurring situations, the Earth would turn into an unfit landmass for life and activity.

We should check deforestation and take up the planting of trees at a massive rate. It will not only save the animals from being extinct but also help create regular rainfall and preserve soil fertility. We should avoid over-dependence on fossil fuels like coal, petroleum products, and firewood which release harmful pollutants to the atmosphere. Non-conventional sources of energy like the sun, biogas and wind should be tapped to meet our growing need for energy. It will check and reduce global warming.

Every drop of water is vital for our survival. We should conserve water by its rational use, rainwater harvesting, checking the surface outflow, etc. industrial and domestic wastes should be properly treated before they are dumped into water bodies.

Every individual can do his or her bit of responsibility to help save the nature around us. To build a sustainable society, every human being should practice in heart and soul the three R’s of Reduce, Reuse, and Recycle. In this way, we can save our nature.

Nature Conservation

Nature conservation is very essential for future generations, if we will damage nature our future generations will suffer.

Nowadays, technological advancement is adversely affecting our nature. Humans are in the quest and search for prosperity and success that they have forgotten the value and importance of beautiful Nature around. The ignorance of nature by humans is the biggest threat to nature. It is essential to make people aware and make them understand the importance of nature so that they do not destroy it in the search for prosperity and success.

On high priority, we should take care of nature so that nature can continue to take care of us. Saving nature is the crying need of our time and we should not ignore it. We should embrace simple living and high thinking as the adage of our lives.

FAQs on Nature Essay

1. How Do You Define Nature?

Nature is defined as our environment. It is the interaction between the physical world around us and the life within it like the atmosphere, climate, natural resources, ecosystem, flora, fauna and humans. Nature also includes non-living things such as water, mountains, landscape, plants, trees and many other things. Nature adds life to mother earth. Nature is the treasure habitation of every essential element that sustains life on this planet earth. Human life on Earth would have been dull and meaningless without the amazing gifts of nature.

2. How is Nature Important to Us?

Nature is the only provider of everything that we need for survival. Nature provides us with food, water, natural fuels, fibres, and medicinal plants. Nature regulates natural processes that include decomposition, water purification, pollution, erosion, and flood control. It also provides non-material benefits like improving the cultural development of humans like recreation, etc.

An imbalance in nature can lead to earthquakes, global warming, floods, and drastic climate changes. It is our duty to understand the importance of nature and how it can negatively affect us all if this rapid consumption of natural resources, pollution, and urbanization takes place.

3. How Should We Save Our Nature?