12 Reflective Teaching Examples

Reflective teaching is a process where teachers reflect on their own teaching practices and learn from their own experiences.

This type of reflection allows teachers to see what works well in their classrooms and what needs improvement. Reflective teaching also helps teachers to understand the impact that their teaching has on students.

Examples of reflective teaching include observing other teachers, taking notes on your own teaching practice, reading about how to improve yourself, and asking for feedback from your students to achieve self-improvement.

Reflective Teaching Examples

1. reflection-in-practice.

Reflection in practice is a concept by David Schon which involves small moments of reflection throughout your day.

Instead of pausing at the end of your activities and reflecting upon what you did, Schon argues that good practitioners reflect in the moment and make tiny changes from moment-to-moment. This is the difference between reflection on practice and reflection in practice. “Reflection on” occurs once the lesson is over. Reflection in occurs during the lesson.

For example, as you’re doing a question-and-answer session with your class, you might realize that the students are tuning out and getting bored. In order to resolve this problem, you might choose to get the students all to stand up and play heads or tails for questions you ask them. This might get the kinesthetic learners re-engaged in the lesson and salvage it from its impending implosion.

Related Article: 15 Action Research Examples

2. Conducting Classroom Observations

Another way to do reflective teaching is to start a classroom observation routine. Create a template for your observations (e.g. listing each student’s name down the side, with notes beside it) and take notes on students’ work.

You could, for example, choose to observe how well students responded to a new classroom intervention. These written observations can form the basis for changes that you can make to your work as you progress.

Similarly, you could make observations about students’ interactions after changing the classroom layout. This can help you edit and refine your chosen layout in order to maximize student learning and figure out the best location for each student.

3. Pivoting based on Formative Feedback

Reflective teachers also try to obtain formative feedback from students in order to gather data that can form the basis of their reflection.

An example of formative feedback is a pre-test a month before the exams.

This pre-test can help the teacher understand the general areas of weakness for their students, and acts as the basis for a pivot in their teaching practices. The teacher may, for example, identify a specific math challenge that the majority of the students had trouble with. They can then put extra focus on that challenge for the next few weeks so the students can ace that challenge in the end-of-term test.

In this way, formative feedback is a core tool for teachers in their formative feedback toolkit.

4. Keeping a Teaching Diary

A personal teaching diary can help teachers to identify trends in their behaviors (and the behaviors of their students) that can help teachers to improve.

For example, in my teaching diary, I will often take notes about how I reacted to certain events. I’ll note my reaction as well as things I did well, ways I effectively self-regulated , and things I did poorly. If I’m taking notes on an answer to a student’s question, I might note that something I did well was “give a clear answer” but an area for improvement might be “I failed to follow-up later in the day to check my student’s comprehension”.

Incidentally, teaching diaries can be extremely useful for self-performance reviews . Bring your teaching diary into the performance review and go over it with your line manager. They will be super impressed with your reflective practice!

5. Receiving Student Evaluations

Despite how much we may despise student evaluations, they can contain important tidbits of information for us.

I often like to compare my evaluations from one to the next to see if there are changes in the student trend. I’ll also work really hard on one aspect of my teaching and see if I can get students to take notice and leave a comment in the evaluation.

For example, one semester, I decided to implement a tech intervention (I let students use an educational app in class). The students used the app, and it turns out – they didn’t like it!

Without the student evaluation, I wouldn’t have been able to identify this problem and work on solving it. You can read all about that study here, which I published in an academic journal.

6. Debriefing with a Mentor

Having a mentor has been invaluable for me in my career. By sitting down with a mentor, I learn a lot about my strengths and weaknesses.

Mentors tend to bring out reflectiveness in all of us. After all, they’re teachers who want us to improve ourselves.

Your mentor may ask you open-ended questions to get you to reflect, or discuss some new points and concepts that you haven’t thought about before. In this process, you’re being prompted to reflect on your on teaching practice and compare what you do to the new ideas that have been presented. You may ask yourself questions like “do I do that?” or “do I need to improve in that area?”

7. Using Self-Reflection Worksheets

Self-reflection worksheets are a good ‘cheat’ for figuring out how to do self-reflection for people who struggle.

You can find these worksheets online through services like Teachers Pay Teachers. They often involve daily activities like:

- Write down one thing you struggled with today.

- Write down one big win.

- Write down one thing you will actively try to work on tomorrow.

These worksheets are simple prompts (that don’t need to take up too much time!) that help you to bring to the front of your consciousness all those thoughts that have been brewing in your mind, so you can think about ways to act upon them tomorrow.

See Also: Self-Reflection Examples

8. Changing Lesson Plans Based on Previous Experiences

At the end of each unit of work, teachers need to look at their lesson plans and self-assess what changes are required.

Everyone is aware of that teacher who’s had the same lesson plan since 2015. They seem lazy for failing to modernize and innovate in their practice.

By contrast, the reflective practitioner spends a moment at the end of the lesson or unit and thinks about what changes might need to be made for next time the lesson is taught.

They might make changes if the information or knowledge about the topic changes (especially important in classes that engage with current events!). Similarly, you might make changes if you feel that there was a particular point in the lesson where there was a lull and you lost the students’ attention.

9. Professional Development Days

Professional development days are a perfect opportunity for reflective teaching.

In fact, the leader of the professional development day is likely to bake reflectiveness into the event. They may prepare speeches or provide activities specifically designed for teachers to take a step back and reflect.

For example, I remember several moments in my career where we had a guest speaker attend our PD day and gave an inspiring speech about the importance of teachers for student development. These events made me think about what I was doing and the “bigger picture” and made me redouble my efforts to be an excellent teacher.

10. Implementing 2-Minute Feedback

The 2-minute feedback concept is excellent for reflective practice. For this method, you simply spend the last 2 minutes of the class trying to get feedback from your students.

One of the easiest ways to do this is to give students a post-it note at the end of the lesson. Have them write on one side something they liked about the lesson and on the other something they didn’t like. Then, you can read the feedback to reflect on how to improve.

With younger students, you can do ‘hands up’ for students and ask them how confident they are with the topic.

For online lessons, I’ve put a thermometer up on the screen and asked students to draw on the thermometer how confident that are (line at the top means very confident, line at the bottom means not confident at all).

11. Reading Books

Books are excellent for helping us to reflect and contemplate. There is a wide range of books for teachers, from philosophical ones like Pedagogy of the Oppressed to very practical workbooks.

Through reading, we encounter new ideas that challenge our current ideas. As we pick up new ideas and information, we interrogate our current thoughts and find ways to assimilate them into our new thinking. Sometimes, that requires us to change our own current opinions or thoughts, and challenge us to consistently improve.

In this way, reading books about teaching is an inherently reflective practice. It makes us better practitioners and more thoughtful people.

12. Listening to Podcasts

Like books, podcasts enable us to consume information that can help us pause and reflect.

I personally love podcasts because I find them easier to consume than books. The conversations and dialogue in podcasts help me to feel immersed in a conversation with close friends. Good podcasts hosts make you feel like they’re grappling with the exact same concerns and emotions as you are – and it’s a motivating experience.

Good podcasts for teachers include The Cult of Pedagogy and Teachers on Fire. These podcasts help me to reflect on my own teaching practice and continue to learn new things that I can compare to my own approaches and integrate when I feel they offer new insights that are valuable.

There are many ways to incorporate reflective practice into your teaching. By taking the time to reflect on your teaching, you can identify areas where you can improve and make changes to your practice. This will help you to become a more effective teacher and better meet the needs of your students. Through reflective practice, you can also develop a stronger sense of who you are as a teacher and what your personal teaching philosophy is.

Drew, C. & Mann, A. (2018). Unfitting, uncomfortable, unacademic: a sociological critique of interactive mobile phone apps in lectures. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education. doi: https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-018-0125-y

Lousberg, L., Rooij, R., Jansen, S. et al. Reflection in design education. Int J Technol Des Educ. 30, 885–897 (2020). doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10798-019-09532-6

Chris Drew (PhD)

Dr. Chris Drew is the founder of the Helpful Professor. He holds a PhD in education and has published over 20 articles in scholarly journals. He is the former editor of the Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education. [Image Descriptor: Photo of Chris]

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 5 Top Tips for Succeeding at University

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 50 Durable Goods Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 100 Consumer Goods Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 30 Globalization Pros and Cons

2 thoughts on “12 Reflective Teaching Examples”

Dr Chris Drew, this article is useful for teachers like me. I really appreciate your hard work. Thank you for being a helpful professor. Sandy

Dr, Chris Drew. First of all Congratulations. This article is handy for me as I am doing my teacher training course. You did a good job, explaining in a simple manner so, anyone can understand easily. Thank you so much. Alka

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Reflective Essay on Different Aspects of Teaching Practice

There are numerous areas of teaching which I need to improve upon, yet I have chosen to focus this essay on some of the fundamental factors to becoming a successful teacher: behaviour management and acting on feedback.

Behaviour Management

On placement I had to be careful to ensure that I had the correct level of formality in my relationships with pupils. This seems to be particularly apt in Mathematics where a significant amount of concentration and effort are needed. Haggerty (2002) suggests that a mathematics teacher needs to be relatively formal, in part due to the subject’s complex properties.

Being overfamiliar with pupils can diminish a teacher’s authority. Initially, in the first few weeks of the placement I was too informal with pupils and failed to progress from a teaching assistant-pupil to a teacher-pupil relationship adequately which requires a formal rather than informal, consultative register (Joos, 1972). However, my good relationship with pupils allowed me to contribute to their learning informally such as regularly helping pupils with maths homework outside of lessons and doing intervention and group work. Pupils seemed to thrive on the support I gave them. The informal, incidental learning (Marsick and Watkins, 1990) that took place clearly supplemented their formal lessons well.

Pupils gained a relational understanding (Skemp, 1977) of the topics they were learning due to my detailed explanations of how and why the maths worked. A great example of this was a colleague informing me of a Y11 student’s progress I had been working closely with: she was now achieving a C in Maths having only being at a grade D/E before, thus making her a candidate to sit the GCSE Higher Maths paper.

However, the rapport I had with pupils sometimes negatively impacted on my experiences in the classroom: particularly in my Year 9 class, where pupils misbehaved as they saw me as more of a student than a proper teacher. After consulting with the regular class teacher, I tried to remedy this by being stricter and tolerating disruption less. Capel and Gervis (2005) suggest that teachers who have high expectations of behaviour from their class tend to get their students to behave well. I found this to be true.

I tried to model the standard of behaviour I expected from the pupils, always being smart and punctual. I greeted pupils at the door at the beginning of the lesson and treated them fairly in the hope they would see me as a role model and copy my behaviour and thought processes (Bandura, 1977). This technique only partially solved the problem. My Year 7 and 8 classes behaved quite well but my Year 9 class was still disruptive, though they behaved better than at the start of my placement. I was teaching more lessons by my third week on placement and this naturally helped me gain some authority as pupils became more used to me as a teacher.

To try and improve the behaviour of my Year 9 group, I tried an alternative approach with them. I raised the volume of my voice, had zero-tolerance on misbehaviour and enforced heavy sanctions such as after-school detentions towards those who did misbehave. Interestingly, this worked on some students and not on others. This is perhaps explained by a University of New Hampshire report (2012) which stated that although some students who have a dearth of discipline at home will respond to this method, pupils who have controlling parents are less likely to respond to this strategy well. This is validated by my own experiences. I become more authoritarian instead of my intended authoritative manner (Ferlazzo, 2012) and damaged the rapport I had with students, creating conflict. Kearney et al. (1991) explain that students who dislike their teacher do not perform to their full potential in lessons, which was certainly true in my Year 9 class.

One approach that I did observe in an NQT’s lesson was to use formal register at the start of the lesson in teacher exposition before gradually using more informal language to assist students through activities and build a rapport with pupils. I found this to be successful in lessons when I trialled this approach. I also noticed that I was a lot more informal and relaxed when working with smaller groups of students as a teaching assistant. Pascarella and Terenzini (1991) explain that small group sizes are effective when a teacher has a large amount of interaction with students and motivates them which is something I always tried to do in my practice.

Gates (2001) highlights a lack of relevance to real life in Mathematics lessons as being a factor in misbehaviour in students. To try and engage students more, I provided more situations where pupils could see the content in a real-life context. Examples included having interesting facts at the start of the lesson such as why there are 360 degrees in a circle and having worded, practical questions on worksheets. As well as establishing strong cross-curricular links with Literacy, this allowed pupils to see the practical uses of mathematics which could motivate them more (Chambers, 2008) and add authenticity to their learning. Cockcroft (1982) suggests that it is hard to implement situations like this in every maths lesson. This is one of the limitations of this method. For example, algebraic topics are harder to link to real life than richer geometry modules. One target I got from my tutor was to have more purpose and meaning in my lessons, which I tried to achieve by chunking lessons into fast-paced activities with links to the real world. This worked for some pupils, but not all: less confident pupils preferred a slower-paced lesson where they had time to understand concepts.

Overall, I was quite a confident and recognisable figure to pupils, which had advantages and disadvantages. Ollerton (2004) argues that an informal teacher-pupil relationship can stimulate negative and disrespectful behaviour from students. This was partially true, particularly in my Year 9 class. This was because many pupils viewed me as a visitor or substitute, a common problem for student teachers on placement (Pope and Shivlock, 2008). However, after increased interaction with students in and out the classroom, they started to respect me more which is crucial to successful learning (Comer, 1995). It seems that the correct balance of being formal, yet approachable is required to be a successful teacher.

Acting on Feedback

Throughout placement I constantly reflected on my practice. I acted on and listened to feedback from experienced teachers. I did so as then they could give me the benefit of their expertise, thus increasing my Zone of Proximal Development (Vygotsky, 1978) by getting closer to their level of teaching capability.

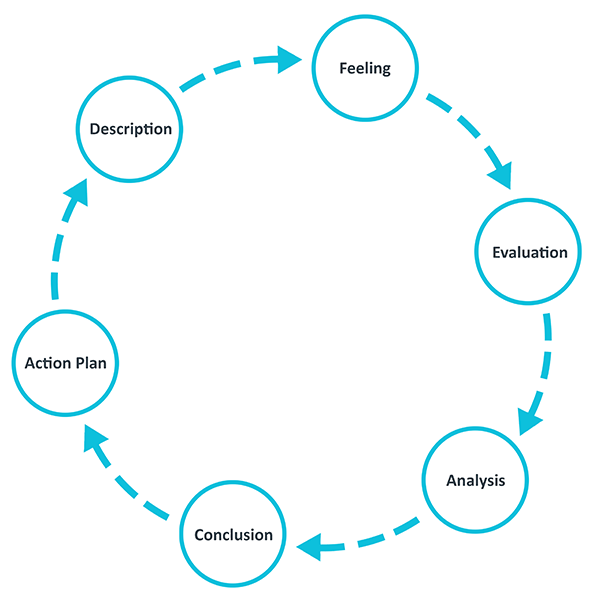

Constant reflection is something that is needed to be an effective teacher. Ofsted (2012) established that the most successful mathematics teachers constantly strived to develop their practice. I kept a daily diary but this was not a sophisticated enough tool to use in my reflections. Schon (1991) states that, in order to become a reflective practitioner, you have to critically analyse your own strengths and weaknesses. My own interpretation of this was to relate theory to practice. From studying feedback given to me, I concluded that my biggest shortfall was in behaviour management. In order to try and overcome this barrier, I applied Honey and Mumford’s (2006) model of learning to a particular scenario involving my Year 9 class who often misbehaved in my lessons:

- Activist- The initial experience/stimuli of misbehaviour that happened in a Year 9 class I was teaching. Although not malicious in any way, students were loud and off task.

- Reflector- This is where I reviewed the experience and sought to understand why they were behaving like that by considering the internal/external conditions which affected their behaviour. I concluded that it was partially because of my teaching style, not having a clear and consistent routine and the school’s weak behaviour policy. It was also due to external factors like it being the last period on a Friday, meaning the students were desperate to get home and not in the mood to listen to me.

- Theorist- When contemplating the situation, I realised that it was not actually all my fault and that there were other factors causing their misbehaviour such as the time of day and the day of the week.

- Pragmatist- When I thought about how I was going to change this, I addressed each set of factors in turn. In terms of the internal factors, I set out clear expectations of behaviour of my class as well as a fixed classroom routine which calmed them down. For the external factors, I made it clear to the class that it was irrelevant that my lesson was last period on a Friday.

Going through this cycle of reflection enabled me to enhance my practice and learn experientially (Kolb, 1976) by reflecting on what I had made mistakes on and how to correct it. In this situation, I did note that the class started to behave better though I need to improve more in this area. However, there are limitations to this style of reflection. Davies (2012) states that it is quite elaborate and may distract from teaching practice. In addition, Price (2004) states that this model of reflection doesn’t really address any major issues. The amount of time spent reflecting on the problem did hinder me in my teaching practice.

To improve further, I needed to look at alternative models of reflection and learning through enactment and getting more voluntary experience in schools. Whilst on placement, I only taught lower school pupils and I need to gain experience teaching KS4 pupils. Observing and assisting experienced teachers will only increase my learning of the teaching profession. I will observe how to manage different classes to improve my performance and consistency in the classroom (Collinson, 1994; Bobek, 2004).

The placement I undertook really developed me as a teacher. I feel a lot more confident leading a class and have more of a teacher presence, particularly when dealing with younger students. I have started to control classes better and feel comfortable dealing with misbehaviour in the lower school. Conversely, I feel I need more practice at handling older students. Future actions I will take to improve my practice is to teach more challenging classes and older year groups in my summer placement to try and become more confident at leading a class.

I feel I have established a solid and reliable model of reflection which allowed me to change my practice and respond well to challenging incidents (see earlier example with my Year 9 class) and establish a plan of action. However, I do need to make sure that I continually reflect and amend my teaching style to suit different types of classes. I have always got on well with pupils and my varied abilities allow me to contribute a lot more to a school than just being a maths teacher.

Ofsted (2008) identify ‘subject expertise’, pedagogical knowledge and strong classroom management as the triumvirate of attributes needed to be a successful mathematics teacher. I feel I can demonstrate these skills well at an individual or group level. If I am comfortable displaying these skills at a whole class level I feel I will become a successful teacher.

Reference List

Bandura, A. (1977) Social Learning Theory. New York: General Learning Press.

Bobek, B. L. (2002) ‘Teacher Longevity- A key to career longevity’, The Clearing House, 75 (4), pp. 202-205.

Capel, S. and Gervis, M. (2005) ‘Motivating pupils’ in Capel, S., Leask, M. and Turner, T. (eds.) Learning to Teach in the Secondary School: A companion to school experience. 4 th edn.

Carroll, H. (1950) ‘A scale of measuring teacher-pupil attributes and teacher-pupil rapport’, Psychological Monographs- General and Applied, 64 (6), pp. 24-27.

Chambers, P. (2008) Teaching Mathematics: Developing as a Reflective Secondary Teacher. London: Sage.

Cockcroft, W. (1982) The Report of the Committee of Inquiry into the Teaching of Mathematics in Schools.

Collinson, V. (1994) Teachers as Learners: Exemplary teachers’ perceptions of personal and professional renewal. Bethesda, MD: Austin and Winfield.

Comer, J. (1995) Lecture given at Education Service Center, Houston.

Davies, S. (2012) ‘Embracing reflective practice’, Education for Primary Care, 23, pp. 9-12.

Ferlazzo, L. (2012) ‘Students who challenge us: Eight things skilled teachers think, say and do.’, Educational Leadership , 70 (2), pp. 100-105.

Gates, P. (2001) Issues in the Teaching of Mathematics. London: Routledge.

Great Britain. Ofsted (2008) Mathematics: Understanding the Score. London: Department for Education.

Great Britain. DfE (2012) Standards for Meeting Qualified Teacher Status. London: Department for Education.

Great Britain. Department for Business, Innovation and Skills (2009) The White Paper: Learning Revolution. London: Department for Business, Innovation and Skills.

Honey, P. and Mumford, A. (2006) The Learning Styles Questionnaire, 80-item version. Maidenhead: Peter Honey Publications.

Joos, M. (1972) Language and cultural diversity in American Education. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Kearney, P., Plax, T. G., Hayes, E. R. and Ivey, M. J. (1991) ‘College teacher misbehaviours: what students don’t like about what teachers say and do.’, Communication Quarterly, 39 (4), pp. 325-340.

Kolb, D. A. (1976) The Learning Style Inventory: Technical Manual. Boston: McBer.

Ollerton, M. (2004) Getting the Buggers to Add Up. London: Continuum.

Pascarella, E. and Terenzini, P. (1991) How College affects students. San Francisco: Jossey Bass.

Pope, M. and Shivlock, K. (2008) Successful Teaching Placements in Secondary Schools. Learning Matters: Exeter.

Price, A. (2004) ‘Encouraging reflection and critical thinking in practice’, Nursing Standard, 18 (47), pp. 123-129.

Schon, D. A. (1991) The Reflective Turn: Case Studies In and On Educational Practice. New York: Teachers Press, Columbia University.

Skemp, R. (1977), ‘Relational Understanding and Instrumental Understanding’, Mathematics Teaching, 77, pp. 20-26.

University of New Hampshire (2012) Controlling parents more likely to have delinquent children. Massachusetts: Science Daily.

Watkins, K. and Marsick, V. (1990) Informal and Incidental Learning in the Workplace. London.

Vygostky, L. S. (1978) Mind in Society: the development of higher psychological processes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Cite this page

Similar essay samples.

- Essay on Maple Leaf Shoes Ltd.

- Essay on Does Religion Cause War?

- Essay on the Collapse of Communism and the Dissection of Bicycle Thiev...

- Essay on Small Office Network Set-Up

- Inclusive learning and adult education

- Essay on Overview, History and Purpose of SOAP

- Faculty & Staff

Developing a reflective teaching practice

Our university is built on a commitment to using the power of discovery, creativity, and analytical thinking to solve challenges, including those we encounter in the process of teaching. While consulting the scholarship of teaching and learning is a good way to identify effective teaching strategies, the most important dimension of an effective teaching practice is reflection.

What is “reflective” teaching?

The American philosopher and educational reformer, John Dewey, considered reflection crucial to learning. As Dewey scholar, Carol Rodgers, notes, Dewey framed reflection as “a systematic, rigorous, disciplined way of thinking” that led to intellectual growth.

Because our students are so diverse and there’s so much variety in instructional contexts, good teaching requires instructors to observe, reflect upon, and adapt their teaching practice . In addition to identifying areas for improvement in your teaching, reflection is also core to an inclusive teaching practice.

Reflective practices

There are lots of ways to be thoughtful about your teaching, but here are a few for each point in the quarter.

Before the beginning of the quarter:

- Reflect on your course goals. What do you want students to be able to do by the time they leave your course?

- Reflect on your own mix of identities. How has privilege or oppression shaped your perspectives?

- Reflect on how your discipline creates knowledge and decides what knowledge is valuable. How has this constrained what and how you teach?

During the quarter:

- Keep a journal to briefly jot down your observations of student interactions and experiences in the classroom. Note things that are working and things you might want to change.

- Get an outside perspective. Ask a colleague to come observe a class and your interactions with students and/or course materials.

- Conduct a mid-quarter evaluation to gather information on how the course is going. Ask yourself what you can do to relieve the pain points that students identified in the evaluation.

At the end of the quarter:

- Reflect on your course data. What do your gradebook and course evaluations indicate about what worked well and what didn’t work so well? What can you do to improve students’ performance?

- Connect with a consultant to brainstorm ways to redesign assignments or improve your teaching practice.

- Dig into the scholarship of teaching and learning to find ideas for how others have improved their teaching practice in a certain area.

Reflecting on your identities and position

Your teaching emerges from your educational background and training, as well as from your personal history and experience. Reflecting on how who you are and what you have experienced shapes your teaching can help you identify ways to better connect with your students.

Positionality and intersectionality

Positionality refers to the social, cultural, and political contexts – including systems of power and oppression – that shape our identities. Our positionalities influence how we approach course design, choose content, teach, and assess student work. Recognizing how your own positionality impacts your teaching can help you create a more inclusive classroom.

On one level, intersectionality refers to the ways that the multiple dimensions of our identity intersect to shape our experience. Black feminist scholars have stressed how social systems based on things such as race, class, gender, sexual orientation, and disability combine to create an interlocking system that privileges some and oppresses others.

Reflecting on your own positionality and the intersectional nature of your identify can help you think more intentionally about your content choices, the materials you assign to your students, and even how the different aspects of your students’ identities may affect their experience in your class.

Empowering students

The relationships that define learning environments are, unavoidably, imbued with power. As an instructor, you hold a position of authority, and a level of implicit institutional power – you determine the content of your course, create assignments, and grade those assignments. But when students have agency in their courses, they are more likely to be engaged and invested in their own learning . Reflecting on the power structures that define your classrooms may help you find ways to recalibrate or redistribute power so that students become more active agents in the creation of disciplinary knowledge, as well as in their own learning.

As you reflect, you might consider adopting one or more of following strategies for empowering your students:

- Take on the role of a guide. Rather than aspiring to transmit information through lecture, consider ways to make students active participants and contributors in their learning. Develop student-driven activities and discussions that create constructive, cooperative learning environments that encourage students to learn together.

- Consider flipping your classroom . Devote the time you spend with students to interaction and collaboration. Create videos focused on your lecture material that students can watch (and rewatch) as a homework activity.

- Work with students to articulate community values and expectations. Consider building community agreements with students. Openly discuss how you will assess students’ work and allow students to ask questions and offer their own ideas for grading. A great way to get students involved in thinking about their own assessment is to co-create assessment rubrics.

- Encourage students to share their own knowledge and expertise. Ask students to think about what they already know about a course topic and how your course can help them build upon that knowledge. Challenge students to think critically about why and how course material is relevant to their own lives.

- Practice inclusive course design. Universal Design for Learning (UDL) principles can help make your teaching more inclusive and offer students more opportunities to engage and express their knowledge.

Online Teaching Hub

Online and Blended Teaching Hub

Reflecting on teaching practice.

Reflection is an integral part of the teaching process. School activities in and outside the classroom create a natural environment for reflective teaching. Professional experience, healthy self-awareness, and genuine care for students and colleagues help teachers to reflect effectively. Reflective practices consist of in-the-moment reflection for immediate action, after-the-moment reflection for future action, and outside reflection for exchange of reflective experience among a teacher’s colleagues and professional learning networks. Reflection promotes evidence-based changes in the classroom to advance teaching practices and is one of the cornerstones of a teacher’s professional development and supports the quality of education in today’s ever-changing world.

Questions to Consider

Why is reflection essential to my growth as a teacher?

How do I receive feedback about my teaching and lesson content?

How does reflection impact my next steps towards continued growth as a blended or online teacher?

At-a-Glance Video

- Topic Summary

- Infographic: Reflective Questioning and Strategies

- Infographic: The Continuous Reflection Cycle

- Infographic: Benefits of Reflective Teaching

Web Resources

Reflection resources.

- Ways to be a More Reflective Teacher

- Benefits of Reflective Teaching and Learning

- How To Apply Reflective Practice when Teaching Online

- How to Encourage Reflective Teaching in Your School

- Self-Reflection: Are You a Reflective Teacher?

- Questions to Tackle When Reflecting on Teaching

- Fun Ways to Reflect on Your Teaching

- Reflective Teaching: 5 Minute Definitions for Teachers in a Hurry

- Reflect on Teaching Practice

Related Online and Blended Teaching Hub Topics

- Building a Professional Learning Network

- Building Effective Relationships

- Culturally Responsive Teaching

- Work-Life Balance

Online and Blended Teaching Hub Tool Pages

- Assessment: Edulastic , Google Forms , Microsoft Forms

- Polling: Mentimeter , Poll Everywhere , Slido

Essays on Learning and Transformation by Leo Casey

Reflection, Teaching Practice and Learning from Experience

Teaching practice or placement is one of the hallmarks of initial teacher education. As with many professions, the novice teacher is expected to learn through experience in an authentic setting. Student teachers are often required to write reflections on they have learned in placement. Many struggle with the task – wondering what actually constitutes reflective writing and why there is so much emphasis on the process of reflection.

Many look to scholarship to provide answers and works by Dewey (1933, How We Think ), Schön (1992, The Reflective Practitioner ), Boud et al (1985, Reflection: Turning Experience Into Learning ), Mezirow, (1990, Fostering Critical Reflection in Adulthood ), Brookfield (2005, The Power of Critical Theory for Adult Learning and Teaching ) and Moon (1999, Reflection in Learning and Professional Development ) are all good resources to improve ones understanding of reflection.

However, knowing the characteristics or constituents of reflective practice is not the same as engaging in reflective practice. Indeed, I have read many essays by students who describe the underpinning theory of reflection but fail to grasp the challenge of practicing reflection.

It is important to realise that the foundation of teaching placement is learning from experience. We are in danger of missing the point if we emphasise ‘reflection’ per se rather than learning. It is more useful to regard reflection as part of the learning process – often an essential part.

A good starting point is to consider a basic model of reflection as a ‘ a situation with me in it ‘. This simple conceptual device has a lot of complexity behind it. Normally, when you think about an experience – say a lesson you taught – your first inclination is to remember from your own perspective. You would perhaps think something like ‘ that went well – I could see the attentive looks of my students as I was explaining’. Good for you! But that’s not thinking about the situation with you in it ! That’s your recall of your perceptions of the situation.

Notice the imaginative shift to look back on a situation and place yourself in the picture. W B Yeats’ poem Among School Children provides an example of this shift when he uses the line “the children’s eyes – in momentary wonder stare upon – A sixty-year-old smiling public man.”

This sense of looking at yourself – often through other people’s eyes (as in Brookfield’s Lenses) – is characteristic of reflective thought. Notice how powerful the simple device can be. I can reflect on events, interactions and complex experiences. Even ‘big picture’ issues like global sustainability can be subjected to reflecting thinking “ There I am in the world and what am I doing to sustain it ?”.

Teachers and many other professions involving human interactions need to engage in reflective practice. No two teaching events are the same. Unlike for example, piloting an aeroplane there is no procedural manual or situational checklists one can draw upon. Teachers develop their skills and knowledge through the ‘engine of experience’.

Accomplished teachers are expert reflective practitioners. They have developed not just the instrumental skills of teaching, but the much deeper capacity to know what skills matter and when to use them.

Reflective writing and journaling are useful for developing reflective capacity. This is especially true for novice professionals.

Here are some guidelines to get you going.

Share this:

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

You May Also Like

What makes a good teacher?

We Need New Stories in Education

Skills of Teaching

Leave a reply cancel reply.

Explore More

Stay in our orbit.

Stay connected with industry news, resources for English teachers and job seekers, ELT events, and more.

Explore Topics

- Global Elt News

- Job Resources

- Industry Insights

- Teaching English Online

- Classroom Games / Activities

- Teaching English Abroad

- Professional Development

Popular Articles

- 5 Popular ESL Teaching Methods Every Teacher Should Know

- 10 Fun Ways to Use Realia in Your ESL Classroom

- How to Teach ESL Vocabulary: Top Methods for Introducing New Words

- Advice From an Expert: TEFL Interview Questions & How to Answer Them

- What Is TESOL? What Is TEFL? Which Certificate Is Better – TEFL or TESOL?

What Is Reflective Teaching and Why Is It Important?

Gerald smith.

- June 11, 2022

If you feel that your teaching is becoming a bit stale or you’re unsure of a lesson’s effectiveness, reflective teaching is the best way to regain your confidence and interest in ESL education. Let’s take a closer look at what reflective teaching entails, why it’s important, and how you can implement reflective practices in your career.

Reflective teaching is covered in detail in the IDELTOnline™ course, Bridge’s most advanced professional TEFL certification, which can be used as a pathway to an MA TESOL at more than 1,600 universities.

What is Reflective Teaching?

Reflective teaching is a teacher’s practice of thinking, writing, and/or speaking about their lessons and their teaching methods and approaches.

It’s easy for teachers to get into a rut while teaching, where it feels like they’re delivering lessons on autopilot. Reflective teaching is a way to break out of that rut and become the best teacher you can be.

In his essay, “Reflective Practice for Language Teachers,” Thomas Farrell writes, “Reflective practice occurs, then, when teachers consciously take on the role of reflective practitioner and subject their own beliefs about teaching and learning to critical analysis, take full responsibility for their actions in the classroom, and continue to improve their teaching practice.”

Want to read the entire essay and get a more in-depth look at reflective teaching? Take the graduate-level IDELTOnline™ course.

Why is Reflective Teaching Important?

“Teachers who engage in reflective practice can develop a deeper understanding of their teaching, assess their professional growth, develop informed decision-making skills, and become proactive and confident in their teaching.” -Farrell

It improves your lesson plans

One of the main benefits of reflective teaching is that it helps you to become a better teacher who engages their students more and consistently improves their lesson plans .

By analyzing different aspects of lessons like teacher talking time or student collaboration, you can measure your success.

For example, if you remember that students weren’t engaged during an activity, you can analyze the reasons why. Maybe you didn’t set a clear context or you overexplained and slowed down student discovery. Or, maybe it didn’t have anything to do with your planning, and the students simply partied the previous night and didn’t want to discuss the differences between the present perfect and past simple.

Whatever the reason, reflective teaching can help you think of a solution.

It can help you break out of a teaching rut

The more you teach, the easier it is to get into a teaching rut. You reuse the same tried and tested activities, you tell the same old anecdotes, and you recycle the same tired grammar explanations.

While reusing activities is great, you need to make sure you’re not doing something that feels boring to you. When you’re not having fun, you can’t expect your students to have fun.

Farrell writes, “If teachers engage in reflective practice they can avoid such burnout because they take the time to stop and think about what is happening in their practice to make sense of it so that they can learn from their experiences rather than mindlessly repeat them year after year.”

Reflective teaching gets you to think about how to modify activities and lesson plans so they’re fresh and interesting for both you and your students.

It inspires you to try new things

When materials like ELT course book activities start to get boring, it’s time to try something new.

Online, there are tons of resources for up-to-date lesson plans. Personal favorites are Onestopenglish and TeachThis.com , but there are hundreds more, some free and some paid.

Another great way to try new things is to collaborate with a fellow teacher. This is easy when working at a language school, but you can also do this online through Facebook groups and Linkedin. Teachers even share lesson plans through Twitter.

It’s part of continuing professional development

Continuing professional development comes in many forms, such as Specialized TEFL/TESOL courses or Micro-credentials that offer targeted training. Reflective teaching is also an effective way to continue developing and expanding your teaching skills throughout your career.

While reflecting on your teaching, you can also think back to training from TEFL courses you’ve already taken and see if you’re fully utilizing what you studied in your online TEFL certification lessons.

Learn more about professional development for EFL teachers.

It provides opportunities to share your experience

Posting your teaching reflections in Facebook groups or on Linkedin helps start conversations around best teaching practices .

You’ll be surprised to see how many teachers have had the same experiences as you or will have suggestions on how to teach in new ways.

This not only allows you to offer and receive great feedback but also builds your network or community of teachers .

See the ways that the IDELTOnline™ sets you apart as a teacher.

What are the characteristics of reflective teaching?

Although reflective teaching can take many forms, there are a few characteristics that appear throughout all types of reflective practices:

- Reflective teaching notes what happens in the classroom, why it happens, and how it can be improved.

- If you are practicing reflective teaching, it’s rare that you will teach the same lesson again in the exact same way because reflective teaching challenges you. You’ll need to critique yourself and your go-to lesson plans.

- Although many teachers write their reflections down, not all reflective teaching needs to be written. Many teachers, instead, choose to speak about their lessons with a colleague or mentor, or what Farrell calls a “Critical Friend.”

- Reflective teaching is collaborative, often involving a head teacher or a colleague.

- Reflecting on and speaking about how your lessons go often leads to helpful insights.

What are some examples of reflective teaching?

Some ways of practicing reflective teaching include:

- Teaching journals: Write down classroom reflections in a journal.

- Classroom observations: Be observed either by a mentor or by recording the lesson and rewatching it yourself.

- Critical friends: Speak about your classes with a friend who can offer constructive criticism.

- Action research: Research something you struggle with, and maybe even take a course to improve specific teaching skills .

- Online groups: Teachers actively post online about reflective teaching in teacher development groups like the Bridge Teaching English Online Facebook Group . Posting online helps teachers get more recognition in the industry as well as organize their reflections.

- Blogs: Many teachers choose to share their reflections by creating their own EFL blogs . For example, Rachel Tsateri, an EL teacher and writer, published a reflective post on her teacher talking time (TTT) on her website, The TEFL Zone . Because Rachel read a lot of the literature around TTT, she was also engaging in action research, a rather academic but effective approach to reflective teaching.

- Teacher beliefs: Continue to develop and verbalize your own beliefs about what makes good teaching. Not sure where to start with your teaching beliefs? Learn about crafting an ESL philosophy of teaching statement.

Try different methods to find the right one for you. Journaling is an easy first step, but if you’re a more social teacher, you might prefer working with a critical friend or a teacher development group.

Teaching, a lot like learning, is a journey. No one becomes a great teacher overnight, so don’t be too hard on yourself when a lesson doesn’t go well. Instead, think critically about how you teach so you can continue to improve your students’ learning experiences and grow in your profession.

Want to learn more about reflective teaching and other best TEFL practices covered in the IDELTOnline™ course? Take a look at what this certification entails and whether it’s right for you.

Gerald Smith is an EL teacher, journalist and occasional poet. Originally from Texas, he now lives on a houseboat in Glasgow, Scotland with his partner and their two kittens.

Reflective Teaching

Reflecting on our teaching experiences, from the effectiveness of assignments to the opportunities for student interaction, is key to refining our courses and overall teaching practice. Reflective teaching can also help us gain closure on what may have felt like an especially long and challenging semester.

Four Approaches to Reflective Teaching

The goal of critical self-reflection is to gain an increased awareness of our teaching from different vantage points (Brookfield 1995). Collecting multiple and varied perspectives on our teaching can help inform our intuitions about teaching through an evidence-based understanding of whether students are learning effectively. Stephen Brookfield, in Becoming a Critically Reflective Teacher , proposes four lenses to use when examining and assessing our teaching:

- The autobiographical. What do I see as the successes and challenges of the course? What went well, and what could be improved for next time? If I could do X again, how might I do it differently?

- The students’ eyes. What do students have to say about what enhanced their learning and what hindered their learning? What recommendations do students have to help improve the course for next time?

- Our colleagues’ experiences. What do my colleagues have to say about what went well for them this semester? What was challenging? If my colleagues are teaching similar courses and/or student populations, what are similarities or differences in our experiences? In our assignments?

- Theoretical literature What are evidence-based strategies for supporting student learning? What does the research have to say about how students learn best in similar courses? What does the research say about how students are experiencing higher education at this moment in time?

Collectively, these four lenses foster repeat engagement with members of our teaching and learning community, both on campus and the broader scholarly community. For Brookfield, however, the most important step to reflective teaching is to go beyond the collection of feedback (i.e., from self, student, peer, and scholarly work) by strategically adjusting our teaching methods and goals. By habitually reflecting on our practice, documenting changes and noting our progress, then making efforts to iterate again, we become student-centered, flexible, and innovative educators.

Selected Examples of Reflective Teaching Strategies

Reflecting on our teaching, or a colleague’s teaching, inherently starts from a place of subjectivity and self-reported experiences -- How do I, as the instructor, feel class went? What do students think about their learning environment? How do I think my assessments compare to a colleague’s in a similar course? Self-reflection, after all, is foundational to recognizing assumptions and biases in how we design and teach our courses. However, we can adjust our approach to reflection by grounding our thinking and feeling to a concrete classroom artifact or objective observation. The following examples for reflective teaching highlight different ways we can start with evidence.

Teaching Journal. Teaching journals are a way to document your teaching experience on a daily or weekly basis. After each class, spend about five minutes recording your thoughts on the day’s lesson and interactions with students. What went well? What was challenging? If I could redo something, what would it be and what would I do differently? At the end of the semester, use your reflections to assess your experience as a whole and make informed decisions regarding future instructional changes. Consider these questions from a 2018 CTL Article .

Were your stated learning outcomes well aligned with class activities and assignments? Did student learning and engagement meet your expectations? Any surprises?

Were there course concepts and materials that students struggled with? Are there opportunities to approach teaching these concepts in a new way?

Are there course policies or other campus resources you can add to your syllabus or bCourses site so students have the information from the start?

Did you encounter any new approaches or practices during the semester, perhaps from a colleague or CTL workshop, that can help you save time and energy?

Assignment Wrapper. The goal of exam wrappers (link is external) is to guide students through a review of their learning and testing experience to inform future adjustments to their learning process. Adapt this exercise to structure your review of an assignment or activity.

Reflect on the design of the assignment. How is this assignment designed to help prepare students to achieve one or more stated learning objectives?

Reflect on the implementation of the assignment. Did student learning and engagement meet your expectations? Were there any surprises?

Reflect on how you communicated your expectations to students. Did you explain how this assignment connects to the broader picture of learning in the course? Did you describe what an exemplary submission or deliverable looks like?

Reflection on the experience as a whole. What adjustments might you make to set students up for success or enhance their learning?

Peer Review of Materials. Find a trusted colleague who teaches a similar course -- similarities may include disciplinary content, course structure, enrollment size, course placement in a curriculum (e.g., introductory or advanced course), and student demographics. Select one assignment, activity, or lecture material (e.g., presentation slides, handouts) to review and gather feedback on. Use this opportunity to discuss the strengths and challenges of designing and using this teaching artifact in the context of what is similar between your courses.

Literature Scan of a Similar Assignment, Activity, or Digital Tool. Select one assignment, activity, or educational technology tool you use in your course. Then, search the literature on education research for articles describing how other instructors use the same teaching method in their courses. Education research explores the conditions under which teaching strategies, such as active learning techniques , values affirmations and social belonging interventions , and inclusive teaching techniques , impact student learning. Scholars consider both lab and authentic classroom contexts, and explore disciplinary-based teaching strategies. When comparing teaching methods, consider the following questions.

What is similar or different to the design or implementation described in the study and my teaching method?

What findings and takeaways can I generalize, adjust, and apply to my teaching context?

How might my teaching method build on the author’s findings?

New to education research? Consider starting with CBE-Life Sciences Education’s repository (link is external) of annotated peer-reviewed articles to unpack various aspects of an education study.

References and Resources For Further Reading

Bailey, K. M., Curtis, A., and Nunan, D. (2001). Pursuing Professional Development: The Self as Source. Boston: Heinle, Cengage Learning.

Brookfield, Stephen. (1995). Becoming a Critically Reflective Teacher. San-Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

“ End-of-the-Semester Reflection from the Teachers Point of View (link is external) ”. Faculty Evaluation and Coaching Department, Academy of Art University.

Fink, L. D. (2003). Creating Significant Learning Experiences: An Integrated Approach to Designing College Courses. San-Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

“ Reflective Teaching (link is external) ”. Poorvu Center for Teaching and Learning, Yale.

Toven-Lindsday, Brit. (2018). “ No Time Like the Present ”. Center for Teaching and Learning, UC Berkeley.

Weimer, Maryellen. (2002). Learner-Centered Teaching: Five Key Changes to Practice. San-Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Search form

- About Faculty Development and Support

- Programs and Funding Opportunities

Consultations, Observations, and Services

- Strategic Resources & Digital Publications

- Canvas @ Yale Support

- Learning Environments @ Yale

- Teaching Workshops

- Teaching Consultations and Classroom Observations

- Teaching Programs

- Spring Teaching Forum

- Written and Oral Communication Workshops and Panels

- Writing Resources & Tutorials

- About the Graduate Writing Laboratory

- Writing and Public Speaking Consultations

- Writing Workshops and Panels

- Writing Peer-Review Groups

- Writing Retreats and All Writes

- Online Writing Resources for Graduate Students

- About Teaching Development for Graduate and Professional School Students

- Teaching Programs and Grants

- Teaching Forums

- Resources for Graduate Student Teachers

- About Undergraduate Writing and Tutoring

- Academic Strategies Program

- The Writing Center

- STEM Tutoring & Programs

- Humanities & Social Sciences

- Center for Language Study

- Online Course Catalog

- Antiracist Pedagogy

- NECQL 2019: NorthEast Consortium for Quantitative Literacy XXII Meeting

- STEMinar Series

- Teaching in Context: Troubling Times

- Helmsley Postdoctoral Teaching Scholars

- Pedagogical Partners

- Instructional Materials

- Evaluation & Research

- STEM Education Job Opportunities

- Yale Connect

- Online Education Legal Statements

You are here

Reflective teaching.

When instructors engage in reflective teaching, they are dedicating time to evaluate their own teaching practice, examine their curricular choices, consider student feedback, and make revisions to improve student belonging and learning. This process requires information gathering, data interpretation, and planning for the future. Reflective teaching involves examining one’s underlying beliefs about teaching and learning and one’s alignment with actual classroom practice before, during and after a course is taught.

When teaching reflectively, instructors think critically about their teaching and look for evidence of effective teaching. This critical analysis can draw on a variety of sources: Brookfield (2017) lays out four crucial sources: “students’ eyes, colleagues’ perceptions, personal experience, and theory and research.” Instructors can use various tools and methods to learn from these sources and reflect on their teaching, ranging from low-key to formal and personal to inter-collegial. For example, reflective teaching may include self-assessment, classroom observations , consideration of student evaluations , or exploration of educational research . Because each semester’s students and their needs are different, reflective teaching is a continual practice that supports effective and student-centered teaching.

Examples of Self-Assessment

Reflection Journals: Instructors might consider capturing a few details of their teaching in a journal to create an ongoing narrative of their teaching across terms and years. Scheduling a dedicated time during the 5 or so minutes after class to write their entries will ensure continual engagement, rather than hoping to find a moment throughout the day. The instructor writes general thoughts about the day’s lesson and might reflect on the following questions: What went well today? What could I have done differently? How will I modify my instruction in the future?

Teaching Inventories: A number of inventories , like the Teaching Practices Inventory (Wieman and Gilbert, 2014), have been developed to help instructors assess and think more broadly about their teaching approaches. Inventories are typically designed to assess the extent to which particular pedagogies are employed (e.g. student- versus teacher-centered practices).

Video-Recorded Teaching Practices: Instructors may request the Poorvu Center to video record their lessons while conducting a classroom observation, or instructors can video record themselves while teaching and use a classroom observation protocol to self-assess their own practices. Some Yale classrooms have video cameras installed for lecture capture , which instructors can then use for their self assessment.

Teaching Portfolio: A more time-intensive practice, the teaching portfolio invites instructors to integrate the various components of their teaching into a cohesive whole, typically starting with a teaching philosophy or statement, moving through sample syllabi and assignments, and ending with evaluations from colleagues and students.Though less focused on classroom practices, a portfolio is an opportunity to reflect on teaching overall. The Poorvu Center offers an opportunity for faculty new to Yale to complete a teaching intensive and reflective program, the Faculty Teaching Academy , which includes a culminating portfolio. Faculty who complete the program will receive a contribution to their research or professional development budgets. The University of Washington CTL offers best practices for creating a teaching portfolio .

Examples of External Assessment

Student Evaluations (Midterm and End-of-Term): In many courses, instructors obtain feedback from students in the form of mid-semester feedback and/or end-of-term student evaluations . Because of potential bias, instructors should consider student evaluations as one data source in their instruction and take note of any prevailing themes (Basow, 1995; Watchel, 1998; Huston, 2005; Reid, L. (2010); Basow, S.A. & Martin, J.L. (2012) ). They can seek out other ways to assess their practices to accompany student evaluation data before taking steps to modify instruction. The Poorvu Center offers consultations regarding mid-semester feedback data collected. They will also conduct small group feedback sessions with an instructor’s students to provide non-evaluative, anonymous conversation notes from students in addition to the traditional survey format. If instructors are interested in sustained feedback over time from a student perspective, then they can also participate in the Pedagogical Partners program.

Peer Review of Teaching: Instructors can ask a trusted colleague to observe their classroom and give them feedback on their teaching. Colleagues can agree on an observation protocol or a list of effective teaching principles to focus on from a teaching practices inventory.

Classroom Observations: Any instructor at Yale may request an observation with feedback from a member of the Poorvu Center staff. Observations are meant to be non-evaluative and promote reflection. They begin with a discussion in which the instructor describes course goals and format as well as any issues or teaching practices that are of primary concern. This initial discussion provides useful context for the observation and the post-observation conversation.

Basow, S.A. (1995). Student evaluations of college professors: When gender matters. Journal of Educational Psychology, 87(4): 656-665.

Basow, S.A. & Martin, J.L. (2012). Bias in student evaluations. In M.E. Kite (Ed.), Effective evaluation of teaching: A guide for faculty and administrators. Society for the Teaching of Psychology.

Brookfield, S. (2017). Becoming a Critically Reflective Teacher, 2nd ed. San Francisco: Jossey Bass.

Huston, T. (2005). Report: Empirical Research on the Impact of Race and Gender in the Evaluation of Teaching. Retrieved 3/10/17 from Seattle University, Center for Excellence in Teaching and Learning website.

Reid, L. (2010). The Role of Perceived Race and Gender in the Evaluation of College Teaching on RateMyProfessors.com. Journal of Diversity in Higher Education. 3 (3): 137–152.

Wachtel, H.K. (1998). Student Evaluation of College Teaching Effectiveness: A Brief Review. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 23(2): 191-212.

YOU MAY BE INTERESTED IN

Reserve a Room

The Poorvu Center for Teaching and Learning partners with departments and groups on-campus throughout the year to share its space. Please review the reservation form and submit a request.

The Poorvu Center for Teaching and Learning routinely supports members of the Yale community with individual instructional consultations and classroom observations.

Instructional Enhancement Fund

The Instructional Enhancement Fund (IEF) awards grants of up to $500 to support the timely integration of new learning activities into an existing undergraduate or graduate course. All Yale instructors of record, including tenured and tenure-track faculty, clinical instructional faculty, lecturers, lectors, and part-time acting instructors (PTAIs), are eligible to apply. Award decisions are typically provided within two weeks to help instructors implement ideas for the current semester.

- Professional development

- Taking responsibility for professional development

Reflective teaching: Exploring our own classroom practice

Reflective teaching means looking at what you do in the classroom, thinking about why you do it, and thinking about if it works - a process of self-observation and self-evaluation.

By collecting information about what goes on in our classroom, and by analysing and evaluating this information, we identify and explore our own practices and underlying beliefs. This may then lead to changes and improvements in our teaching.

Reflective teaching is therefore a means of professional development which begins in our classroom.

- Why it is important

- Teacher diary

- Peer observation

- Recording lessons

- Student feedback

Why it is important Many teachers already think about their teaching and talk to colleagues about it too. You might think or tell someone that "My lesson went well" or "My students didn't seem to understand" or "My students were so badly behaved today."

However, without more time spent focussing on or discussing what has happened, we may tend to jump to conclusions about why things are happening. We may only notice reactions of the louder students. Reflective teaching therefore implies a more systematic process of collecting, recording and analysing our thoughts and observations, as well as those of our students, and then going on to making changes.

- If a lesson went well we can describe it and think about why it was successful.

- If the students didn't understand a language point we introduced we need to think about what we did and why it may have been unclear.

- If students are misbehaving - what were they doing, when and why?

Beginning the process of reflection You may begin a process of reflection in response to a particular problem that has arisen with one or your classes, or simply as a way of finding out more about your teaching. You may decide to focus on a particular class of students, or to look at a feature of your teaching - for example how you deal with incidents of misbehaviour or how you can encourage your students to speak more English in class.

The first step is to gather information about what happens in the class. Here are some different ways of doing this.

Teacher diary This is the easiest way to begin a process of reflection since it is purely personal. After each lesson you write in a notebook about what happened. You may also describe your own reactions and feelings and those you observed on the part of the students. You are likely to begin to pose questions about what you have observed. Diary writing does require a certain discipline in taking the time to do it on a regular basis.

Here are some suggestions for areas to focus on to help you start your diary.

Download diary suggestions 51k

Peer observation Invite a colleague to come into your class to collect information about your lesson. This may be with a simple observation task or through note taking. This will relate back to the area you have identified to reflect upon. For example, you might ask your colleague to focus on which students contribute most in the lesson, what different patterns of interaction occur or how you deal with errors.

Recording lessons Video or audio recordings of lessons can provide very useful information for reflection. You may do things in class you are not aware of or there may be things happening in the class that as the teacher you do not normally see.

- How much do you talk?

- What about?

- Are instructions and explanations clear?

- How much time do you allocate to student talk?

- How do you respond to student talk?

- Where do you stand?

- Who do you speak to?

- How do you come across to the students?

Student feedback You can also ask your students what they think about what goes on in the classroom. Their opinions and perceptions can add a different and valuable perspective. This can be done with simple questionnaires or learning diaries for example.

What to do next Once you have some information recorded about what goes on in your classroom, what do you do?

- Think You may have noticed patterns occurring in your teaching through your observation. You may also have noticed things that you were previously unaware of. You may have been surprised by some of your students' feedback. You may already have ideas for changes to implement.

- If you have colleagues who also wish to develop their teaching using reflection as a tool, you can meet to discuss issues. Discussion can be based around scenarios from your own classes.

- Using a list of statements about teaching beliefs (for example, pairwork is a valuable activity in the language class or lexis is more important than grammar) you can discuss which ones you agree or disagree with, and which ones are reflected in your own teaching giving evidence from your self-observation.

- Read You may decide that you need to find out more about a certain area. There are plenty of websites for teachers of English now where you can find useful teaching ideas, or more academic articles. There are also magazines for teachers where you can find articles on a wide range of topics. Or if you have access to a library or bookshop, there are plenty of books for English language teachers.

- Ask Pose questions to websites or magazines to get ideas from other teachers. Or if you have a local teachers' association or other opportunities for in-service training, ask for a session on an area that interests you.

Conclusion Reflective teaching is a cyclical process, because once you start to implement changes, then the reflective and evaluative cycle begins again.

- What are you doing?

- Why are you doing it?

- How effective is it?

- How are the students responding?

- How can you do it better?

As a result of your reflection you may decide to do something in a different way, or you may just decide that what you are doing is the best way. And that is what professional development is all about.

Julie Tice, Teacher, Trainer, Writer, British Council Lisbon

This article was first published in 2004

Well organized

Greetings, The steps explained in reflective teaching are quite practical, no matter how many years educators put into their experience, properly guided ideas will definitely enhance how to engage our students, at the end of the day, what matters is how the learning took place in the classroom. and reflect on how i inspired my students to deliver the content, the reflective teaching practice not only helps to get back and analyze, but helps the educator to be more organized, thank you for the wonderful article.

- Log in or register to post comments

Wonderful advice

Thank you very much for these suggestions. They are wonderful.

online journal

Reflection is the key, teaching diary, reflective teaching practices.

One practiice I have used to encourage reflective practice is not to give answers to students questions in the way that most time teachers do. Instead I ask them to think about trhe answer and if they can't, I ask a series of questions or put up other examples that lead them to the answer.

Students of their own volition then say things like "you make me work out and think about the language I use"

The important factor here is to ensure that the language is being used..not just studied..and that way the affective involvement by the students is heightened. Here is some more insights on the values of this.

Hello, Thank you

Thank you for the valuable suggestions. I have barely started teaching and I realize that there is room for a lot of improvement. I believe that by reflective teaching, a teacher will be able to have an impact on the students.

Interesting...

Dear Julie,

Thanks so much for the interesting article, they are the facts that every teacher should know. We shouldn't forget one - the teacher is the main figure in the class and every luck begins with his professionalism and creativity!

Thank You . I think this is a good article to help students observe their student. This very helpful for me , because im a young teacher , and my pupils deserve the best :)

Thank you for great ideas. I will take these advice

Really a wonderful article Julie! Thank you for such an informative article! It is precise, covers all aspects, simple enough for teachers to start reflecting. It is just what the teachers need to start writing without hesitation or doubts. Thank You once again.

To the editor

Reflecting teaching.

Dear Editor, This is a very useful article for English teachers and trainers. Teaching diary is a must for all teachers and trainers.

JVL NARASIMHA RAO

Though it's an old article ... it's great ..

Yeah .. I agree on all reflection emethods you suggested in your article and I would like to shed hight on peer observation. My collegues and I have used this method for two year. However, we faced some problems when the feedback was not nice and constructive enough or when the observed teacher was kind of sensetive. I think it must be very clear from the very beginning that the feedback is for improvement! if one is kind of sensetive to getting corrected it's better not to use this method. Thanks again.

Reflection and motivation

Hi everyone,

Well-done, Julie. I want to relate motivation to reflective teaching. It's obvious that reflections of any sort require a great deal of cognitive and emotional energy. What can be done to motivate those teachers who think that teaching is a dead-end job and that trying to develop professionally is not intrinsically motivating?

Reflecting on your teaching

Dear Julie,

An excellent article. Nothing can be more important then self reflection, i.e. looking inwardly to find out what you did, how you did it and how and what you need to do to make it better. Unfortunately we seldome reflect on ourselves.

I would like to introduce few simple questions every teacher should ask after completing a lesson:

1. Can I state one thing thet the students took back with them after my lesson?

2. Can I state one thing that I wanted to do but was not able to it becasue of insufficient time?

3. Can I state one thing that I should not have done in this lesson?

4. Can I state one thing that I think I did well?

Answers to these questions will enable the teacher to do better in the future.

Research and insight

Browse fascinating case studies, research papers, publications and books by researchers and ELT experts from around the world.

See our publications, research and insight

Questions for Reflective Essays on Teaching

You may wish to consider some of the following issues as you think about writing a reflective essay on your teaching. We have grouped these questions into three subgroups: questions about your discipline and your research, questions about your student learning objectives, and questions about your teaching. These questions are not a template designed to produce a formulaic reflective essay. Select the ones which most effectively stimulate your thinking about your teaching, transform or adopt these questions, or create your own questions. Finally, while reflective essays should address the broad teaching issues which are fundamental to your teaching, you might also consider concentrating upon a single course.

Discipline and Research

- Think about your discipline as a lens or a window onto a given body of material, ideas, or texts. What problem, issue, or question first animated the construction of that lens? Do those same issues continue to animate it today? Think about the historical origins of your discipline, and its evolution as a field of study.

- What first captured your interest in your discipline? What now engages your attention about that discipline (i.e., what is your current research)? Think about the origins of your entry into your field of study, and about the transformations which your thought has undergone to lead you to your present interests.

- Under what broad problem, issue, or question would you subsume your current or most recent research projects and interests? How might that same problem, issue, or question have some impact on the lives, interests, or futures of your students? What kinds of texts or course materials might help you to demonstrate the relationship of your work and your discipline to your students?

Student Learning

- What important skills, abilities, theories or ideas will your discipline help students to develop or obtain? How will those skills or that knowledge help your students solve problems they may encounter, resolve difficult issues or choices with which they are confronted, or appreciate important–and perhaps otherwise neglected–dimensions of their lives and minds?

- How–if at all–do you communicate the value of your disciplinary lens, and the kind of research you pursue, to your students?

- What do you want your students to be able to do as a result of taking a course with you? Recall? Synthesize? Analyze? Interpret? Apply? Think both across all of your courses and within individual courses.

- What abstract reasoning skills will your students need to accomplish these objectives?