How to Write a Research Paper: Parts of the Paper

- Choosing Your Topic

- Citation & Style Guides This link opens in a new window

- Critical Thinking

- Evaluating Information

- Parts of the Paper

- Writing Tips from UNC-Chapel Hill

- Librarian Contact

Parts of the Research Paper Papers should have a beginning, a middle, and an end. Your introductory paragraph should grab the reader's attention, state your main idea, and indicate how you will support it. The body of the paper should expand on what you have stated in the introduction. Finally, the conclusion restates the paper's thesis and should explain what you have learned, giving a wrap up of your main ideas.

1. The Title The title should be specific and indicate the theme of the research and what ideas it addresses. Use keywords that help explain your paper's topic to the reader. Try to avoid abbreviations and jargon. Think about keywords that people would use to search for your paper and include them in your title.

2. The Abstract The abstract is used by readers to get a quick overview of your paper. Typically, they are about 200 words in length (120 words minimum to 250 words maximum). The abstract should introduce the topic and thesis, and should provide a general statement about what you have found in your research. The abstract allows you to mention each major aspect of your topic and helps readers decide whether they want to read the rest of the paper. Because it is a summary of the entire research paper, it is often written last.

3. The Introduction The introduction should be designed to attract the reader's attention and explain the focus of the research. You will introduce your overview of the topic, your main points of information, and why this subject is important. You can introduce the current understanding and background information about the topic. Toward the end of the introduction, you add your thesis statement, and explain how you will provide information to support your research questions. This provides the purpose and focus for the rest of the paper.

4. Thesis Statement Most papers will have a thesis statement or main idea and supporting facts/ideas/arguments. State your main idea (something of interest or something to be proven or argued for or against) as your thesis statement, and then provide your supporting facts and arguments. A thesis statement is a declarative sentence that asserts the position a paper will be taking. It also points toward the paper's development. This statement should be both specific and arguable. Generally, the thesis statement will be placed at the end of the first paragraph of your paper. The remainder of your paper will support this thesis.

Students often learn to write a thesis as a first step in the writing process, but often, after research, a writer's viewpoint may change. Therefore a thesis statement may be one of the final steps in writing.

Examples of Thesis Statements from Purdue OWL

5. The Literature Review The purpose of the literature review is to describe past important research and how it specifically relates to the research thesis. It should be a synthesis of the previous literature and the new idea being researched. The review should examine the major theories related to the topic to date and their contributors. It should include all relevant findings from credible sources, such as academic books and peer-reviewed journal articles. You will want to:

- Explain how the literature helps the researcher understand the topic.

- Try to show connections and any disparities between the literature.

- Identify new ways to interpret prior research.

- Reveal any gaps that exist in the literature.

More about writing a literature review. . .

6. The Discussion The purpose of the discussion is to interpret and describe what you have learned from your research. Make the reader understand why your topic is important. The discussion should always demonstrate what you have learned from your readings (and viewings) and how that learning has made the topic evolve, especially from the short description of main points in the introduction.Explain any new understanding or insights you have had after reading your articles and/or books. Paragraphs should use transitioning sentences to develop how one paragraph idea leads to the next. The discussion will always connect to the introduction, your thesis statement, and the literature you reviewed, but it does not simply repeat or rearrange the introduction. You want to:

- Demonstrate critical thinking, not just reporting back facts that you gathered.

- If possible, tell how the topic has evolved over the past and give it's implications for the future.

- Fully explain your main ideas with supporting information.

- Explain why your thesis is correct giving arguments to counter points.

7. The Conclusion A concluding paragraph is a brief summary of your main ideas and restates the paper's main thesis, giving the reader the sense that the stated goal of the paper has been accomplished. What have you learned by doing this research that you didn't know before? What conclusions have you drawn? You may also want to suggest further areas of study, improvement of research possibilities, etc. to demonstrate your critical thinking regarding your research.

- << Previous: Evaluating Information

- Next: Research >>

- Last Updated: Feb 13, 2024 8:35 AM

- URL: https://libguides.ucc.edu/research_paper

Chapter 1 Research Papers: Titles and Abstracts

- First Online: 17 July 2020

Cite this chapter

- Adrian Wallwork 3 &

- Anna Southern 3

Part of the book series: English for Academic Research ((EAR))

5538 Accesses

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

1 Whole paper: Concentrate above all on readability; grammar is generally less important.

mistake I have surveyed thousands of PhD students about what they consider to be the fundamentals of writing research papers in English. While some recognize that readability should be prioritized (i.e. minimizing long sentences and redundancy), most tend to focus on grammar and vocabulary. Few mention conciseness and even fewer mention ambiguity. In my opinion, it is a mistake to think that good grammar and appropriate vocabulary are the key to a good paper. There are other elements, including the ones listed below, that are much more likely to determine whether your paper will be accepted for publication, and which have a big impact on what a reviewer might refer to as ‘poor English’. This whole book is designed to help you understand what areas you should really be concentrating on.

Always think about the referee and the reader. Your aim is to have your paper published. You will increase your chances of acceptance of your manuscript if referees and journal editors (i) find your paper easy to read; (ii) understand what gap you filled and how your findings differ from the literature. You need to meet their expectations with regard to how your content is organized. This is achieved by writing clearly and concisely, and by carefully structuring not only each section, but also each paragraph and each sentence.

In your own native language, you may be more accustomed to write from your own perspective, rather than the reader’s perspective. To write well in English, it may help you to imagine that you are the reader rather than the author. This entails constantly thinking how easily a reader will be able to assimilate what you the author are telling them.

Write concisely with no redundancy and no ambiguity, and you will make fewer mistakes in your English. The more you write, the more mistakes in English you will make. If you avoid redundant words and phrases you will significantly increase the readability of your paper.

Read other papers, learn the standard phrases, use these papers as a model. You will improve your command of English considerably by reading lots of other papers in your field. You can underline or note down the typical phrases that they use to express the various language functions (e.g. outlining aims, reviewing the literature, highlighting their findings) that you too will need in your paper. You can also note down how they structure their paper and then use their paper as a template (i.e. a model) for your own.

If your paper is relatively easy to read and each sentence adds value for the reader, then you are much more likely to be cited in other people’s work. If you are cited, then your work as an academic will become more rewarding - people will contact you and want to work with you.

More details about readability and being concise can be found in Sections 31 - 56 .

2 Titles: Ensure your title as specific as possible. Delete unnecessary words.

mistake Titles are often written without too much thought. The result is vague titles that don’t give much information to the reader, and consequently dramatically decrease the chances of your paper being read. A paper might be rejected simply because the title and the content of the paper do not match. The title is the first thing that reviewers read, so you don’t want to mislead them. In fact the title tends to be the benchmark against which reviewers assess the content of the paper.

Example 1: The first 3-4 words of all these titles give no information. By deleting these no-info words, the key words (ABC and XYZ) are shifted to the beginning of the title.

Example 2: as a tool to could simply be replaced with to . In the YES example, the title has been reformulated into a statement / conclusion. This can be a really effective way to tell readers what your main finding is. But check other titles in your journal to see whether such statements are used by other authors (some editors don’t like this style).

Example 3: The NO example seems specific, but it isn’t. It doesn’t say how it affects quality and storage.

solution Before you write your title, make a list of all the key words associated with your paper and your key findings (i.e. what makes your research unique). Put these key words and findings in order of priority. Now try to put the most important key word(s) as close as possible to the beginning of the title. Next ensure that the resulting title contains a definite and concise indication of what is written in the paper itself and somehow includes your key finding. Consider avoiding acronyms and abbreviations ( Se = selenium, but Google Scholar and other indexes may not know this).

impact The title should contain as many key words as possible to help both the reader and search engines identify the key concepts. By including, if you can, your key finding(s) in your title you will have created a mini abstract that helps the reader to understand the importance of your paper.

You may find the following books helpful when writing a research paper:

English for Writing Research Papers

https://www.springer.com/gp/book/9783319260921

English for Academic Research: Writing Exercises

https://www.springer.com/gp/book/9781461442974

English for Academic Research: Grammar Exercises

https://www.springer.com/gp/book/9781461442882

English for Academic Research: Vocabulary Exercises

https://www.springer.com/gp/book/9781461442677

3 Titles: Avoid ‘clever’ titles.

Example 1: The NO example is correct, but the first words don’t really give an idea of what the paper is about. Moreover, no search engine is going to be looking for ‘hidden world’ as a key word. If you really want to use such a device, then put it at the end of the title. This creates a two-part title (second YES example) using a colon in the middle. This is a very useful means to shift key information to the beginning, but still retain a more fun or colloquial tone.

Example 2: The NO example is not a great title: i) it begins with a generic expression ( first insights ) and the second part contains a vocabulary mistake (it should be witch’s not wizard’s ) and what does a chance to explore mean? Making mistakes with vocabulary is typical when you try to write a non-technical title. The result is that you give readers an initial bad impression, which may discourage them from reading the rest of the paper. And how many non-natives are going to know what a witch’s cauldron is?

solution and impact Show your title to as many of your colleagues as you can. Ask them if they can improve it by making it more specific and so that it will immediately make sense to the editor and reviewers. Note: If you are particularly pleased with your title because to you it sounds clever or witty, consider rewriting or at least check that other people agree with you!

4 Abstracts: Be concise - especially in the first sentence.

mistake The style of an abstract likely reflects the style of the whole paper. Readers may find the NO! style confusing and thus the essence of the meaning is lost. They may also think that if the abstract is full of redundant words, then the rest of the paper is likely to be full of redundancy too. Readers may thus decide not to read the paper.

solution Only provide the reader with what is strictly necessary. Reducing the number of words will also help you meet the word count set by the journal (i.e. the maximum number of words that you can use in an abstract).

impact The YES! version is more concise, dramatic and memorable, but with no loss of information. It contains 30% fewer words - this will enable you to i) respect the journal’s word count requirements of the abstract; ii) free up more space for providing extra details. You want your Abstract to seem professional. If the English is poor and there is much redundancy the reader may see this as a sign of unclear thinking (as well as unclear English) and may then even doubt the whole research method.

5 Abstracts: Don’t begin the abstract with non key words.

mistake The first line of the abstract is likely to be the first sentence of your paper that the reader will read. If they see a series of words (in italics in the NO! example) that give no indication as to what you did and found in your research, they may stop reading.

solution Shift key words/info to the beginning. Reduce the number of non-key words, i.e. words that do not add value for the reader

impact If the reader sees the key words and key concepts immediately, they will be encouraged to read the rest of the Abstract, and hopefully the rest of the paper.

6 Abstracts: Make it clear why the purpose of your investigation is important.

mistake In the NO example the reader is told the purpose of the research, but not the reason why this purpose is important.

solution Don’t just tell the readers what you did, but also why you did it. Do this within the first three sentences of the abstract. Keep the sentences short - this will help to highlight the importance of what your research involves.

impact If you tell your readers near the beginning of the abstract why you carried out your research, they are more likely to continue reading. If you just give them background info or make them wait too long before they discover the rationale underlying your research objectives, readers may simply stop reading.

7 Abstracts: Clearly differentiate between the state-of-the-art and what you did in your research.

mistake In the abstract above, the authors were trying to describe their own work, i.e. what they did during their research. However, their style is confusing. In fact, in the NO version, the reader cannot be clear whether the authors are talking about their work or another author’s work. This is because they use the passive form, and they use the present tense indifferently whether they are talking about their work or other people’s work. By convention the past simple rather than the present simple is used to indicate what you did (as opposed to what is already known - present tense).

solution If your journal allows, use the personal form we . You can use it in combination with phrases such as in this work / paper / study , and this work / paper / study shows that ... Use the past simple ( were calculated , rather than the present is calculated or the present prefect has been calculated ) to indicate what you did.

There are two solutions shown in the YES column. The first YES solution is written in a personal style using we and the verbs that describe what the authors did are in the past form. The reader is thus certain that the authors are talking about their work.

The second YES solution is written in an impersonal style using the passive form. However, it is still relatively clear when the authors are talking about their work (they use the past tense) and when they are talking about other researchers (they use the present tense, e.g. CFD transient analyses which are commonly used in analysing racist statements).

impact If it is clear to the reader what your particular contribution is, he/she is more likely to continue reading the paper. This factor is even more important for the reviewers of your paper. If they don’t understand what you did and how you are filling the gap in the state of the art, then they will be less inclined to recommend your paper for publication.

8 Structured Abstracts - Background: Be careful of tense usage.

mistake This section is entitled Background, so you are not talking about what you did in your research, but about the state of the art, i.e. what we know at the moment. Thus ’has proved’ indicates the situation until now, whereas the past tense ( showed ) would imply that you made this discovery. Likewise, aging resulted implies that you are talking about your work, whereas leads to means that you are talking in general, i.e. what is already known. On the other hand has never been is correct because it means from the past until now, and it implies that in this paper this topic will be investigated for the first time.

solution For details on tense usage in Abstracts and background information see:

impact If you use the correct tenses, readers will not be confused between what other researchers have done and what you did.

9 Abstracts: When writing a single paragraph, write it like a ’structured abstract’.

mistake One of the biggest mistakes in writing an abstract is to forget that the abstract is a summary of the entire paper. The NO! example is little more than an introduction to the topic with some results. The author has forgotten to mention the methods, limitations and implications. Note however that not all journals require you to mention the limitations and implications in your abstract.

solution To avoid this problem, imagine that you are writing a structured abstract. If you answer the questions / headings typically used in a structured abstract, then you will remember to include everything. You will then produce an abstract like the YES example in the left-hand column.

example of structured abstract

Summary answer : CC therapy can... Furthermore,....

What is known already : CC treatment has been shown to....

Study design, size, duration : This was a randomized cross-over double blind controlled study (RCT) using...

Participants/materials, setting, methods : 21 out of the 24 enrolled men concluded the study. Inclusion criteria were:...

Main results and the role of chance : We observed that....

Limitations, reasons for caution : This study is the first to... However,...

Wider implications of the findings : CC is able to increase T production and should be considered as...

impact Readers read an abstract to understand what the whole paper is about. By using a structured abstract as a template you will provide readers and reviewers with all the standard information that is required.

10 Abstract and Introduction: Avoid the word ’attempt’ and avoid making bold statements beginning with ’this is the first …".

mistake The word attempt is a little misleading - it suggests that you tried to do something but doesn’t tell the reader whether you actually succeeded or not.

Saying this is the first time … may be dangerous because you can rarely be 100% sure that you are the first to do something.

solution Remove attempt . Precede this is the first time with one of the following: to the best of our knowledge … we believe that … as far as we are aware …

impact By removing attempt you clarify for the reader that you succeeded in your task. By adding to the best of our knowledge you protect yourself from possible criticism by the reviewers that in reality this is not the first time. If your overall tone is confident but not arrogant, you will gain the trust of your readers.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

English for Academics SAS, Pisa, Italy

Adrian Wallwork & Anna Southern

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2020 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Wallwork, A., Southern, A. (2020). Chapter 1 Research Papers: Titles and Abstracts. In: 100 Tips to Avoid Mistakes in Academic Writing and Presenting. English for Academic Research. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-44214-9_1

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-44214-9_1

Published : 17 July 2020

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-030-44213-2

Online ISBN : 978-3-030-44214-9

eBook Packages : Social Sciences Social Sciences (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Introduction to Problem Statements, Purpose Statements, and Research Questions

Worksheets and Guides

Chapter 1 playlist.

- Student Experience Feedback Buttons

- Narrowing Your Topic

- Problem Statement

- Purpose Statement

- Conceptual Framework

- Theoretical Framework

- Quantitative Research Questions This link opens in a new window

- Qualitative Research Questions This link opens in a new window

- Qualitative & Quantitative Research Support with the ASC This link opens in a new window

- Library Research Consultations This link opens in a new window

Jump to DSE Guide

Need help ask us.

Chapter 1 introduces the research problem and the evidence supporting the existence of the problem. It outlines an initial review of the literature on the study topic and articulates the purpose of the study. The definitions of any technical terms necessary for the reader to understand are essential. Chapter 1 also presents the research questions and theoretical foundation (Ph.D.) or conceptual framework (Applied Doctorate) and provides an overview of the research methods (qualitative or quantitative) being used in the study.

- Research Feasibility Checklist Use this checklist to make sure your study will be feasible, reasonable, justifiable, and necessary.

- Alignment Worksheet Use this worksheet to make sure your problem statement, purpose, and research questions are aligned. Alignment indicates the degree to which the purpose of the study follows logically from the problem statement; and the degree to which the research questions help address the study’s purpose. Alignment is important because it helps ensure that the research study is well-designed and based on logical arguments.

- SOBE Research Design and Chapter 1 Checklist If you are in the School of Business and Economics (SOBE), use this checklist one week before the Communication and Research Design Checkpoint. Work with your Chair to determine if you need to complete this.

Was this resource helpful?

- Next: Narrowing Your Topic >>

- Last Updated: Apr 24, 2024 2:48 PM

- URL: https://resources.nu.edu/c.php?g=1006886

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Chapter 1: What is Research and Research Writing?

Write here, write now.

Developing your skills as a writer will make you more successful in ALL of your classes. Knowing how to think critically, organize your ideas, be concise, ask questions, perform research and back up your claims with evidence is key to almost everything you will do at university.

Writing is life

Solid writing skills will help you wow your family and friends with your well-articulated ideas, ace job interviews, build confidence in yourself, and feel part of a community of writers.

Beyond University

Whether you go on to graduate school, teach, work for the government or a non-profit, start your own business or your own heavy metal band, becoming a stronger writer will give you a solid foundation you can keep building on.

This chapter:

- Defines research and gives examples

- Describes the writing process

- Introduces writing using research

- Introduces simple research writing

- Prompts you to think about research and writing meaningful to you

Kimmerer, Robin Wall. Braiding Sweetgrass : Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge, and the Teachings of Plants . Milkweed Editions, 2013.

From “ Why Writing Matters “ . Writing Place: A Scholarly Writing Textbook by Lindsay Cuff. CC BY-NC-SA 4.0. 2023.

Reading and Writing Research for Undergraduates Copyright © 2023 by Stephanie Ojeda Ponce is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

13.1 Formatting a Research Paper

Learning objectives.

- Identify the major components of a research paper written using American Psychological Association (APA) style.

- Apply general APA style and formatting conventions in a research paper.

In this chapter, you will learn how to use APA style , the documentation and formatting style followed by the American Psychological Association, as well as MLA style , from the Modern Language Association. There are a few major formatting styles used in academic texts, including AMA, Chicago, and Turabian:

- AMA (American Medical Association) for medicine, health, and biological sciences

- APA (American Psychological Association) for education, psychology, and the social sciences

- Chicago—a common style used in everyday publications like magazines, newspapers, and books

- MLA (Modern Language Association) for English, literature, arts, and humanities

- Turabian—another common style designed for its universal application across all subjects and disciplines

While all the formatting and citation styles have their own use and applications, in this chapter we focus our attention on the two styles you are most likely to use in your academic studies: APA and MLA.

If you find that the rules of proper source documentation are difficult to keep straight, you are not alone. Writing a good research paper is, in and of itself, a major intellectual challenge. Having to follow detailed citation and formatting guidelines as well may seem like just one more task to add to an already-too-long list of requirements.

Following these guidelines, however, serves several important purposes. First, it signals to your readers that your paper should be taken seriously as a student’s contribution to a given academic or professional field; it is the literary equivalent of wearing a tailored suit to a job interview. Second, it shows that you respect other people’s work enough to give them proper credit for it. Finally, it helps your reader find additional materials if he or she wishes to learn more about your topic.

Furthermore, producing a letter-perfect APA-style paper need not be burdensome. Yes, it requires careful attention to detail. However, you can simplify the process if you keep these broad guidelines in mind:

- Work ahead whenever you can. Chapter 11 “Writing from Research: What Will I Learn?” includes tips for keeping track of your sources early in the research process, which will save time later on.

- Get it right the first time. Apply APA guidelines as you write, so you will not have much to correct during the editing stage. Again, putting in a little extra time early on can save time later.

- Use the resources available to you. In addition to the guidelines provided in this chapter, you may wish to consult the APA website at http://www.apa.org or the Purdue University Online Writing lab at http://owl.english.purdue.edu , which regularly updates its online style guidelines.

General Formatting Guidelines

This chapter provides detailed guidelines for using the citation and formatting conventions developed by the American Psychological Association, or APA. Writers in disciplines as diverse as astrophysics, biology, psychology, and education follow APA style. The major components of a paper written in APA style are listed in the following box.

These are the major components of an APA-style paper:

Body, which includes the following:

- Headings and, if necessary, subheadings to organize the content

- In-text citations of research sources

- References page

All these components must be saved in one document, not as separate documents.

The title page of your paper includes the following information:

- Title of the paper

- Author’s name

- Name of the institution with which the author is affiliated

- Header at the top of the page with the paper title (in capital letters) and the page number (If the title is lengthy, you may use a shortened form of it in the header.)

List the first three elements in the order given in the previous list, centered about one third of the way down from the top of the page. Use the headers and footers tool of your word-processing program to add the header, with the title text at the left and the page number in the upper-right corner. Your title page should look like the following example.

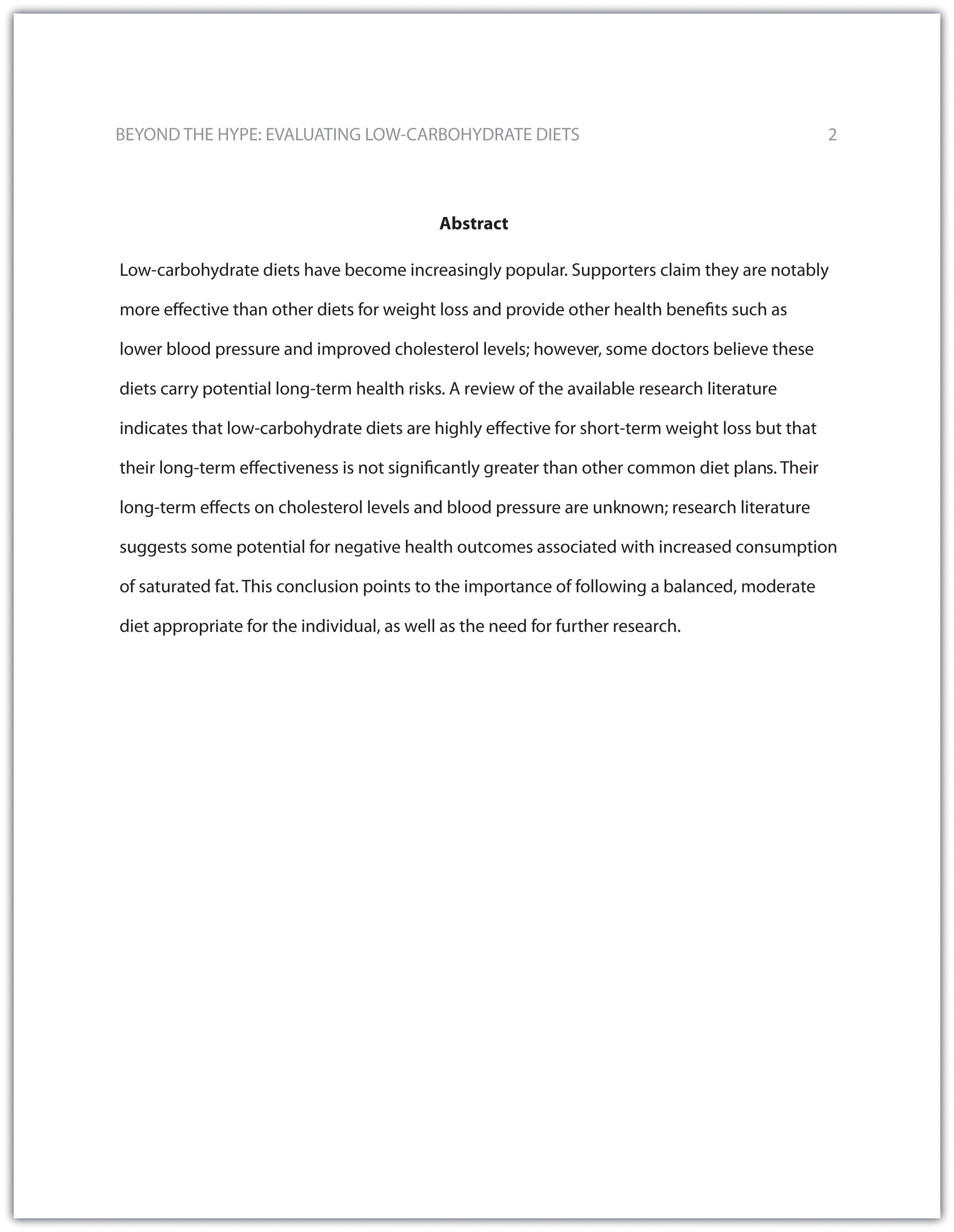

The next page of your paper provides an abstract , or brief summary of your findings. An abstract does not need to be provided in every paper, but an abstract should be used in papers that include a hypothesis. A good abstract is concise—about one hundred fifty to two hundred fifty words—and is written in an objective, impersonal style. Your writing voice will not be as apparent here as in the body of your paper. When writing the abstract, take a just-the-facts approach, and summarize your research question and your findings in a few sentences.

In Chapter 12 “Writing a Research Paper” , you read a paper written by a student named Jorge, who researched the effectiveness of low-carbohydrate diets. Read Jorge’s abstract. Note how it sums up the major ideas in his paper without going into excessive detail.

Write an abstract summarizing your paper. Briefly introduce the topic, state your findings, and sum up what conclusions you can draw from your research. Use the word count feature of your word-processing program to make sure your abstract does not exceed one hundred fifty words.

Depending on your field of study, you may sometimes write research papers that present extensive primary research, such as your own experiment or survey. In your abstract, summarize your research question and your findings, and briefly indicate how your study relates to prior research in the field.

Margins, Pagination, and Headings

APA style requirements also address specific formatting concerns, such as margins, pagination, and heading styles, within the body of the paper. Review the following APA guidelines.

Use these general guidelines to format the paper:

- Set the top, bottom, and side margins of your paper at 1 inch.

- Use double-spaced text throughout your paper.

- Use a standard font, such as Times New Roman or Arial, in a legible size (10- to 12-point).

- Use continuous pagination throughout the paper, including the title page and the references section. Page numbers appear flush right within your header.

- Section headings and subsection headings within the body of your paper use different types of formatting depending on the level of information you are presenting. Additional details from Jorge’s paper are provided.

Begin formatting the final draft of your paper according to APA guidelines. You may work with an existing document or set up a new document if you choose. Include the following:

- Your title page

- The abstract you created in Note 13.8 “Exercise 1”

- Correct headers and page numbers for your title page and abstract

APA style uses section headings to organize information, making it easy for the reader to follow the writer’s train of thought and to know immediately what major topics are covered. Depending on the length and complexity of the paper, its major sections may also be divided into subsections, sub-subsections, and so on. These smaller sections, in turn, use different heading styles to indicate different levels of information. In essence, you are using headings to create a hierarchy of information.

The following heading styles used in APA formatting are listed in order of greatest to least importance:

- Section headings use centered, boldface type. Headings use title case, with important words in the heading capitalized.

- Subsection headings use left-aligned, boldface type. Headings use title case.

- The third level uses left-aligned, indented, boldface type. Headings use a capital letter only for the first word, and they end in a period.

- The fourth level follows the same style used for the previous level, but the headings are boldfaced and italicized.

- The fifth level follows the same style used for the previous level, but the headings are italicized and not boldfaced.

Visually, the hierarchy of information is organized as indicated in Table 13.1 “Section Headings” .

Table 13.1 Section Headings

A college research paper may not use all the heading levels shown in Table 13.1 “Section Headings” , but you are likely to encounter them in academic journal articles that use APA style. For a brief paper, you may find that level 1 headings suffice. Longer or more complex papers may need level 2 headings or other lower-level headings to organize information clearly. Use your outline to craft your major section headings and determine whether any subtopics are substantial enough to require additional levels of headings.

Working with the document you developed in Note 13.11 “Exercise 2” , begin setting up the heading structure of the final draft of your research paper according to APA guidelines. Include your title and at least two to three major section headings, and follow the formatting guidelines provided above. If your major sections should be broken into subsections, add those headings as well. Use your outline to help you.

Because Jorge used only level 1 headings, his Exercise 3 would look like the following:

Citation Guidelines

In-text citations.

Throughout the body of your paper, include a citation whenever you quote or paraphrase material from your research sources. As you learned in Chapter 11 “Writing from Research: What Will I Learn?” , the purpose of citations is twofold: to give credit to others for their ideas and to allow your reader to follow up and learn more about the topic if desired. Your in-text citations provide basic information about your source; each source you cite will have a longer entry in the references section that provides more detailed information.

In-text citations must provide the name of the author or authors and the year the source was published. (When a given source does not list an individual author, you may provide the source title or the name of the organization that published the material instead.) When directly quoting a source, it is also required that you include the page number where the quote appears in your citation.

This information may be included within the sentence or in a parenthetical reference at the end of the sentence, as in these examples.

Epstein (2010) points out that “junk food cannot be considered addictive in the same way that we think of psychoactive drugs as addictive” (p. 137).

Here, the writer names the source author when introducing the quote and provides the publication date in parentheses after the author’s name. The page number appears in parentheses after the closing quotation marks and before the period that ends the sentence.

Addiction researchers caution that “junk food cannot be considered addictive in the same way that we think of psychoactive drugs as addictive” (Epstein, 2010, p. 137).

Here, the writer provides a parenthetical citation at the end of the sentence that includes the author’s name, the year of publication, and the page number separated by commas. Again, the parenthetical citation is placed after the closing quotation marks and before the period at the end of the sentence.

As noted in the book Junk Food, Junk Science (Epstein, 2010, p. 137), “junk food cannot be considered addictive in the same way that we think of psychoactive drugs as addictive.”

Here, the writer chose to mention the source title in the sentence (an optional piece of information to include) and followed the title with a parenthetical citation. Note that the parenthetical citation is placed before the comma that signals the end of the introductory phrase.

David Epstein’s book Junk Food, Junk Science (2010) pointed out that “junk food cannot be considered addictive in the same way that we think of psychoactive drugs as addictive” (p. 137).

Another variation is to introduce the author and the source title in your sentence and include the publication date and page number in parentheses within the sentence or at the end of the sentence. As long as you have included the essential information, you can choose the option that works best for that particular sentence and source.

Citing a book with a single author is usually a straightforward task. Of course, your research may require that you cite many other types of sources, such as books or articles with more than one author or sources with no individual author listed. You may also need to cite sources available in both print and online and nonprint sources, such as websites and personal interviews. Chapter 13 “APA and MLA Documentation and Formatting” , Section 13.2 “Citing and Referencing Techniques” and Section 13.3 “Creating a References Section” provide extensive guidelines for citing a variety of source types.

Writing at Work

APA is just one of several different styles with its own guidelines for documentation, formatting, and language usage. Depending on your field of interest, you may be exposed to additional styles, such as the following:

- MLA style. Determined by the Modern Languages Association and used for papers in literature, languages, and other disciplines in the humanities.

- Chicago style. Outlined in the Chicago Manual of Style and sometimes used for papers in the humanities and the sciences; many professional organizations use this style for publications as well.

- Associated Press (AP) style. Used by professional journalists.

References List

The brief citations included in the body of your paper correspond to the more detailed citations provided at the end of the paper in the references section. In-text citations provide basic information—the author’s name, the publication date, and the page number if necessary—while the references section provides more extensive bibliographical information. Again, this information allows your reader to follow up on the sources you cited and do additional reading about the topic if desired.

The specific format of entries in the list of references varies slightly for different source types, but the entries generally include the following information:

- The name(s) of the author(s) or institution that wrote the source

- The year of publication and, where applicable, the exact date of publication

- The full title of the source

- For books, the city of publication

- For articles or essays, the name of the periodical or book in which the article or essay appears

- For magazine and journal articles, the volume number, issue number, and pages where the article appears

- For sources on the web, the URL where the source is located

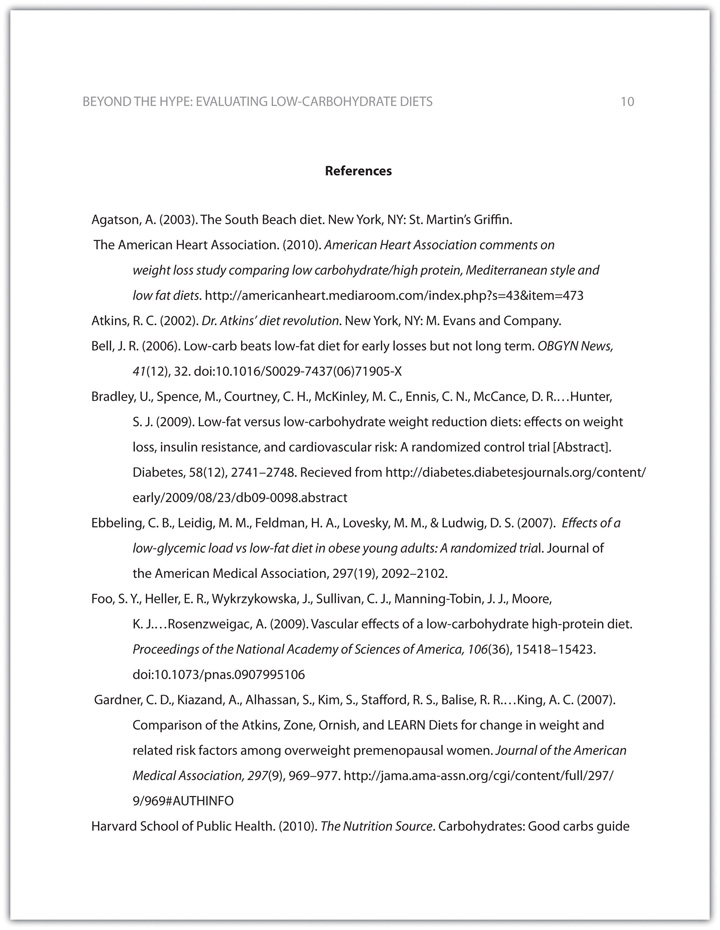

The references page is double spaced and lists entries in alphabetical order by the author’s last name. If an entry continues for more than one line, the second line and each subsequent line are indented five spaces. Review the following example. ( Chapter 13 “APA and MLA Documentation and Formatting” , Section 13.3 “Creating a References Section” provides extensive guidelines for formatting reference entries for different types of sources.)

In APA style, book and article titles are formatted in sentence case, not title case. Sentence case means that only the first word is capitalized, along with any proper nouns.

Key Takeaways

- Following proper citation and formatting guidelines helps writers ensure that their work will be taken seriously, give proper credit to other authors for their work, and provide valuable information to readers.

- Working ahead and taking care to cite sources correctly the first time are ways writers can save time during the editing stage of writing a research paper.

- APA papers usually include an abstract that concisely summarizes the paper.

- APA papers use a specific headings structure to provide a clear hierarchy of information.

- In APA papers, in-text citations usually include the name(s) of the author(s) and the year of publication.

- In-text citations correspond to entries in the references section, which provide detailed bibliographical information about a source.

Writing for Success Copyright © 2015 by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Chapter 1: Introduction to Research Methods

Learning Objectives

At the end of this chapter, you will be able to:

- Define the term “research methods”.

- List the nine steps in undertaking a research project.

- Differentiate between applied and basic research.

- Explain where research ideas come from.

- Define ontology and epistemology and explain the difference between the two.

- Identify and describe five key research paradigms in social sciences.

- Differentiate between inductive and deductive approaches to research.

Welcome to Introduction to Research Methods. In this textbook, you will learn why research is done and, more importantly, about the methods researchers use to conduct research. Research comes in many forms and, although you may feel that it has no relevance to you and/ or that you know nothing about it, you are exposed to research multiple times a day. You also undertake research yourself, perhaps without even realizing it. This course will help you to understand the research you are exposed to on a daily basis, and how to be more critical of the research you read and use in your own life and career.

This text is intended as an introduction. A plethora of resources exists related to more detailed aspects of conducting research; it is not our intention to replace any of these more comprehensive resources. Keep notes and build your own reading list of articles as you go through the course. Feedback helps to improve this open-source textbook, and is appreciated in the development of the resource.

Research Methods, Data Collection and Ethics Copyright © 2020 by Valerie Sheppard is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

- Link to facebook

- Link to linkedin

- Link to twitter

- Link to youtube

- Writing Tips

How to Structure the Table of Contents for a Research Paper

4-minute read

- 16th July 2023

So you’ve made it to the important step of writing the table of contents for your paper. Congratulations on making it this far! Whether you’re writing a research paper or a dissertation , the table of contents not only provides the reader with guidance on where to find the sections of your paper, but it also signals that a quality piece of research is to follow. Here, we will provide detailed instructions on how to structure the table of contents for your research paper.

Steps to Create a Table of Contents

- Insert the table of contents after the title page.

Within the structure of your research paper , you should place the table of contents after the title page but before the introduction or the beginning of the content. If your research paper includes an abstract or an acknowledgements section , place the table of contents after it.

- List all the paper’s sections and subsections in chronological order.

Depending on the complexity of your paper, this list will include chapters (first-level headings), chapter sections (second-level headings), and perhaps subsections (third-level headings). If you have a chapter outline , it will come in handy during this step. You should include the bibliography and all appendices in your table of contents. If you have more than a few charts and figures (more often the case in a dissertation than in a research paper), you should add them to a separate list of charts and figures that immediately follows the table of contents. (Check out our FAQs below for additional guidance on items that should not be in your table of contents.)

- Paginate each section.

Label each section and subsection with the page number it begins on. Be sure to do a check after you’ve made your final edits to ensure that you don’t need to update the page numbers.

- Format your table of contents.

The way you format your table of contents will depend on the style guide you use for the rest of your paper. For example, there are table of contents formatting guidelines for Turabian/Chicago and MLA styles, and although the APA recommends checking with your instructor for formatting instructions (always a good rule of thumb), you can also create a table of contents for a research paper that follows APA style .

- Add hyperlinks if you like.

Depending on the word processing software you’re using, you may also be able to hyperlink the sections of your table of contents for easier navigation through your paper. (Instructions for this feature are available for both Microsoft Word and Google Docs .)

To summarize, the following steps will help you create a clear and concise table of contents to guide readers through your research paper:

1. Insert the table of contents after the title page.

2. List all the sections and subsections in chronological order.

3. Paginate each section.

4. Format the table of contents according to your style guide.

5. Add optional hyperlinks.

If you’d like help formatting and proofreading your research paper , check out some of our services. You can even submit a sample for free . Best of luck writing your research paper table of contents!

What is a table of contents?

A table of contents is a listing of each section of a document in chronological order, accompanied by the page number where the section begins. A table of contents gives the reader an overview of the contents of a document, as well as providing guidance on where to find each section.

Find this useful?

Subscribe to our newsletter and get writing tips from our editors straight to your inbox.

What should I include in my table of contents?

If your paper contains any of the following sections, they should be included in your table of contents:

● Chapters, chapter sections, and subsections

● Introduction

● Conclusion

● Appendices

● Bibliography

Although recommendations may differ among institutions, you generally should not include the following in your table of contents:

● Title page

● Abstract

● Acknowledgements

● Forward or preface

If you have several charts, figures, or tables, consider creating a separate list for them that will immediately follow the table of contents. Also, you don’t need to include the table of contents itself in your table of contents.

Is there more than one way to format a table of contents?

Yes! In addition to following any recommendations from your instructor or institution, you should follow the stipulations of your style guide .

Share this article:

Post A New Comment

Got content that needs a quick turnaround? Let us polish your work. Explore our editorial business services.

3-minute read

How to Insert a Text Box in a Google Doc

Google Docs is a powerful collaborative tool, and mastering its features can significantly enhance your...

2-minute read

How to Cite the CDC in APA

If you’re writing about health issues, you might need to reference the Centers for Disease...

5-minute read

Six Product Description Generator Tools for Your Product Copy

Introduction If you’re involved with ecommerce, you’re likely familiar with the often painstaking process of...

What Is a Content Editor?

Are you interested in learning more about the role of a content editor and the...

The Benefits of Using an Online Proofreading Service

Proofreading is important to ensure your writing is clear and concise for your readers. Whether...

6 Online AI Presentation Maker Tools

Creating presentations can be time-consuming and frustrating. Trying to construct a visually appealing and informative...

Make sure your writing is the best it can be with our expert English proofreading and editing.

Chapter 1. Introduction

“Science is in danger, and for that reason it is becoming dangerous” -Pierre Bourdieu, Science of Science and Reflexivity

Why an Open Access Textbook on Qualitative Research Methods?

I have been teaching qualitative research methods to both undergraduates and graduate students for many years. Although there are some excellent textbooks out there, they are often costly, and none of them, to my mind, properly introduces qualitative research methods to the beginning student (whether undergraduate or graduate student). In contrast, this open-access textbook is designed as a (free) true introduction to the subject, with helpful, practical pointers on how to conduct research and how to access more advanced instruction.

Textbooks are typically arranged in one of two ways: (1) by technique (each chapter covers one method used in qualitative research); or (2) by process (chapters advance from research design through publication). But both of these approaches are necessary for the beginner student. This textbook will have sections dedicated to the process as well as the techniques of qualitative research. This is a true “comprehensive” book for the beginning student. In addition to covering techniques of data collection and data analysis, it provides a road map of how to get started and how to keep going and where to go for advanced instruction. It covers aspects of research design and research communication as well as methods employed. Along the way, it includes examples from many different disciplines in the social sciences.

The primary goal has been to create a useful, accessible, engaging textbook for use across many disciplines. And, let’s face it. Textbooks can be boring. I hope readers find this to be a little different. I have tried to write in a practical and forthright manner, with many lively examples and references to good and intellectually creative qualitative research. Woven throughout the text are short textual asides (in colored textboxes) by professional (academic) qualitative researchers in various disciplines. These short accounts by practitioners should help inspire students. So, let’s begin!

What is Research?

When we use the word research , what exactly do we mean by that? This is one of those words that everyone thinks they understand, but it is worth beginning this textbook with a short explanation. We use the term to refer to “empirical research,” which is actually a historically specific approach to understanding the world around us. Think about how you know things about the world. [1] You might know your mother loves you because she’s told you she does. Or because that is what “mothers” do by tradition. Or you might know because you’ve looked for evidence that she does, like taking care of you when you are sick or reading to you in bed or working two jobs so you can have the things you need to do OK in life. Maybe it seems churlish to look for evidence; you just take it “on faith” that you are loved.

Only one of the above comes close to what we mean by research. Empirical research is research (investigation) based on evidence. Conclusions can then be drawn from observable data. This observable data can also be “tested” or checked. If the data cannot be tested, that is a good indication that we are not doing research. Note that we can never “prove” conclusively, through observable data, that our mothers love us. We might have some “disconfirming evidence” (that time she didn’t show up to your graduation, for example) that could push you to question an original hypothesis , but no amount of “confirming evidence” will ever allow us to say with 100% certainty, “my mother loves me.” Faith and tradition and authority work differently. Our knowledge can be 100% certain using each of those alternative methods of knowledge, but our certainty in those cases will not be based on facts or evidence.

For many periods of history, those in power have been nervous about “science” because it uses evidence and facts as the primary source of understanding the world, and facts can be at odds with what power or authority or tradition want you to believe. That is why I say that scientific empirical research is a historically specific approach to understand the world. You are in college or university now partly to learn how to engage in this historically specific approach.

In the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries in Europe, there was a newfound respect for empirical research, some of which was seriously challenging to the established church. Using observations and testing them, scientists found that the earth was not at the center of the universe, for example, but rather that it was but one planet of many which circled the sun. [2] For the next two centuries, the science of astronomy, physics, biology, and chemistry emerged and became disciplines taught in universities. All used the scientific method of observation and testing to advance knowledge. Knowledge about people , however, and social institutions, however, was still left to faith, tradition, and authority. Historians and philosophers and poets wrote about the human condition, but none of them used research to do so. [3]

It was not until the nineteenth century that “social science” really emerged, using the scientific method (empirical observation) to understand people and social institutions. New fields of sociology, economics, political science, and anthropology emerged. The first sociologists, people like Auguste Comte and Karl Marx, sought specifically to apply the scientific method of research to understand society, Engels famously claiming that Marx had done for the social world what Darwin did for the natural world, tracings its laws of development. Today we tend to take for granted the naturalness of science here, but it is actually a pretty recent and radical development.

To return to the question, “does your mother love you?” Well, this is actually not really how a researcher would frame the question, as it is too specific to your case. It doesn’t tell us much about the world at large, even if it does tell us something about you and your relationship with your mother. A social science researcher might ask, “do mothers love their children?” Or maybe they would be more interested in how this loving relationship might change over time (e.g., “do mothers love their children more now than they did in the 18th century when so many children died before reaching adulthood?”) or perhaps they might be interested in measuring quality of love across cultures or time periods, or even establishing “what love looks like” using the mother/child relationship as a site of exploration. All of these make good research questions because we can use observable data to answer them.

What is Qualitative Research?

“All we know is how to learn. How to study, how to listen, how to talk, how to tell. If we don’t tell the world, we don’t know the world. We’re lost in it, we die.” -Ursula LeGuin, The Telling

At its simplest, qualitative research is research about the social world that does not use numbers in its analyses. All those who fear statistics can breathe a sigh of relief – there are no mathematical formulae or regression models in this book! But this definition is less about what qualitative research can be and more about what it is not. To be honest, any simple statement will fail to capture the power and depth of qualitative research. One way of contrasting qualitative research to quantitative research is to note that the focus of qualitative research is less about explaining and predicting relationships between variables and more about understanding the social world. To use our mother love example, the question about “what love looks like” is a good question for the qualitative researcher while all questions measuring love or comparing incidences of love (both of which require measurement) are good questions for quantitative researchers. Patton writes,

Qualitative data describe. They take us, as readers, into the time and place of the observation so that we know what it was like to have been there. They capture and communicate someone else’s experience of the world in his or her own words. Qualitative data tell a story. ( Patton 2002:47 )

Qualitative researchers are asking different questions about the world than their quantitative colleagues. Even when researchers are employed in “mixed methods” research ( both quantitative and qualitative), they are using different methods to address different questions of the study. I do a lot of research about first-generation and working-college college students. Where a quantitative researcher might ask, how many first-generation college students graduate from college within four years? Or does first-generation college status predict high student debt loads? A qualitative researcher might ask, how does the college experience differ for first-generation college students? What is it like to carry a lot of debt, and how does this impact the ability to complete college on time? Both sets of questions are important, but they can only be answered using specific tools tailored to those questions. For the former, you need large numbers to make adequate comparisons. For the latter, you need to talk to people, find out what they are thinking and feeling, and try to inhabit their shoes for a little while so you can make sense of their experiences and beliefs.

Examples of Qualitative Research

You have probably seen examples of qualitative research before, but you might not have paid particular attention to how they were produced or realized that the accounts you were reading were the result of hours, months, even years of research “in the field.” A good qualitative researcher will present the product of their hours of work in such a way that it seems natural, even obvious, to the reader. Because we are trying to convey what it is like answers, qualitative research is often presented as stories – stories about how people live their lives, go to work, raise their children, interact with one another. In some ways, this can seem like reading particularly insightful novels. But, unlike novels, there are very specific rules and guidelines that qualitative researchers follow to ensure that the “story” they are telling is accurate , a truthful rendition of what life is like for the people being studied. Most of this textbook will be spent conveying those rules and guidelines. Let’s take a look, first, however, at three examples of what the end product looks like. I have chosen these three examples to showcase very different approaches to qualitative research, and I will return to these five examples throughout the book. They were all published as whole books (not chapters or articles), and they are worth the long read, if you have the time. I will also provide some information on how these books came to be and the length of time it takes to get them into book version. It is important you know about this process, and the rest of this textbook will help explain why it takes so long to conduct good qualitative research!

Example 1 : The End Game (ethnography + interviews)

Corey Abramson is a sociologist who teaches at the University of Arizona. In 2015 he published The End Game: How Inequality Shapes our Final Years ( 2015 ). This book was based on the research he did for his dissertation at the University of California-Berkeley in 2012. Actually, the dissertation was completed in 2012 but the work that was produced that took several years. The dissertation was entitled, “This is How We Live, This is How We Die: Social Stratification, Aging, and Health in Urban America” ( 2012 ). You can see how the book version, which was written for a more general audience, has a more engaging sound to it, but that the dissertation version, which is what academic faculty read and evaluate, has a more descriptive title. You can read the title and know that this is a study about aging and health and that the focus is going to be inequality and that the context (place) is going to be “urban America.” It’s a study about “how” people do something – in this case, how they deal with aging and death. This is the very first sentence of the dissertation, “From our first breath in the hospital to the day we die, we live in a society characterized by unequal opportunities for maintaining health and taking care of ourselves when ill. These disparities reflect persistent racial, socio-economic, and gender-based inequalities and contribute to their persistence over time” ( 1 ). What follows is a truthful account of how that is so.

Cory Abramson spent three years conducting his research in four different urban neighborhoods. We call the type of research he conducted “comparative ethnographic” because he designed his study to compare groups of seniors as they went about their everyday business. It’s comparative because he is comparing different groups (based on race, class, gender) and ethnographic because he is studying the culture/way of life of a group. [4] He had an educated guess, rooted in what previous research had shown and what social theory would suggest, that people’s experiences of aging differ by race, class, and gender. So, he set up a research design that would allow him to observe differences. He chose two primarily middle-class (one was racially diverse and the other was predominantly White) and two primarily poor neighborhoods (one was racially diverse and the other was predominantly African American). He hung out in senior centers and other places seniors congregated, watched them as they took the bus to get prescriptions filled, sat in doctor’s offices with them, and listened to their conversations with each other. He also conducted more formal conversations, what we call in-depth interviews, with sixty seniors from each of the four neighborhoods. As with a lot of fieldwork , as he got closer to the people involved, he both expanded and deepened his reach –

By the end of the project, I expanded my pool of general observations to include various settings frequented by seniors: apartment building common rooms, doctors’ offices, emergency rooms, pharmacies, senior centers, bars, parks, corner stores, shopping centers, pool halls, hair salons, coffee shops, and discount stores. Over the course of the three years of fieldwork, I observed hundreds of elders, and developed close relationships with a number of them. ( 2012:10 )

When Abramson rewrote the dissertation for a general audience and published his book in 2015, it got a lot of attention. It is a beautifully written book and it provided insight into a common human experience that we surprisingly know very little about. It won the Outstanding Publication Award by the American Sociological Association Section on Aging and the Life Course and was featured in the New York Times . The book was about aging, and specifically how inequality shapes the aging process, but it was also about much more than that. It helped show how inequality affects people’s everyday lives. For example, by observing the difficulties the poor had in setting up appointments and getting to them using public transportation and then being made to wait to see a doctor, sometimes in standing-room-only situations, when they are unwell, and then being treated dismissively by hospital staff, Abramson allowed readers to feel the material reality of being poor in the US. Comparing these examples with seniors with adequate supplemental insurance who have the resources to hire car services or have others assist them in arranging care when they need it, jolts the reader to understand and appreciate the difference money makes in the lives and circumstances of us all, and in a way that is different than simply reading a statistic (“80% of the poor do not keep regular doctor’s appointments”) does. Qualitative research can reach into spaces and places that often go unexamined and then reports back to the rest of us what it is like in those spaces and places.

Example 2: Racing for Innocence (Interviews + Content Analysis + Fictional Stories)

Jennifer Pierce is a Professor of American Studies at the University of Minnesota. Trained as a sociologist, she has written a number of books about gender, race, and power. Her very first book, Gender Trials: Emotional Lives in Contemporary Law Firms, published in 1995, is a brilliant look at gender dynamics within two law firms. Pierce was a participant observer, working as a paralegal, and she observed how female lawyers and female paralegals struggled to obtain parity with their male colleagues.

Fifteen years later, she reexamined the context of the law firm to include an examination of racial dynamics, particularly how elite white men working in these spaces created and maintained a culture that made it difficult for both female attorneys and attorneys of color to thrive. Her book, Racing for Innocence: Whiteness, Gender, and the Backlash Against Affirmative Action , published in 2012, is an interesting and creative blending of interviews with attorneys, content analyses of popular films during this period, and fictional accounts of racial discrimination and sexual harassment. The law firm she chose to study had come under an affirmative action order and was in the process of implementing equitable policies and programs. She wanted to understand how recipients of white privilege (the elite white male attorneys) come to deny the role they play in reproducing inequality. Through interviews with attorneys who were present both before and during the affirmative action order, she creates a historical record of the “bad behavior” that necessitated new policies and procedures, but also, and more importantly , probed the participants ’ understanding of this behavior. It should come as no surprise that most (but not all) of the white male attorneys saw little need for change, and that almost everyone else had accounts that were different if not sometimes downright harrowing.

I’ve used Pierce’s book in my qualitative research methods courses as an example of an interesting blend of techniques and presentation styles. My students often have a very difficult time with the fictional accounts she includes. But they serve an important communicative purpose here. They are her attempts at presenting “both sides” to an objective reality – something happens (Pierce writes this something so it is very clear what it is), and the two participants to the thing that happened have very different understandings of what this means. By including these stories, Pierce presents one of her key findings – people remember things differently and these different memories tend to support their own ideological positions. I wonder what Pierce would have written had she studied the murder of George Floyd or the storming of the US Capitol on January 6 or any number of other historic events whose observers and participants record very different happenings.

This is not to say that qualitative researchers write fictional accounts. In fact, the use of fiction in our work remains controversial. When used, it must be clearly identified as a presentation device, as Pierce did. I include Racing for Innocence here as an example of the multiple uses of methods and techniques and the way that these work together to produce better understandings by us, the readers, of what Pierce studied. We readers come away with a better grasp of how and why advantaged people understate their own involvement in situations and structures that advantage them. This is normal human behavior , in other words. This case may have been about elite white men in law firms, but the general insights here can be transposed to other settings. Indeed, Pierce argues that more research needs to be done about the role elites play in the reproduction of inequality in the workplace in general.

Example 3: Amplified Advantage (Mixed Methods: Survey Interviews + Focus Groups + Archives)

The final example comes from my own work with college students, particularly the ways in which class background affects the experience of college and outcomes for graduates. I include it here as an example of mixed methods, and for the use of supplementary archival research. I’ve done a lot of research over the years on first-generation, low-income, and working-class college students. I am curious (and skeptical) about the possibility of social mobility today, particularly with the rising cost of college and growing inequality in general. As one of the few people in my family to go to college, I didn’t grow up with a lot of examples of what college was like or how to make the most of it. And when I entered graduate school, I realized with dismay that there were very few people like me there. I worried about becoming too different from my family and friends back home. And I wasn’t at all sure that I would ever be able to pay back the huge load of debt I was taking on. And so I wrote my dissertation and first two books about working-class college students. These books focused on experiences in college and the difficulties of navigating between family and school ( Hurst 2010a, 2012 ). But even after all that research, I kept coming back to wondering if working-class students who made it through college had an equal chance at finding good jobs and happy lives,

What happens to students after college? Do working-class students fare as well as their peers? I knew from my own experience that barriers continued through graduate school and beyond, and that my debtload was higher than that of my peers, constraining some of the choices I made when I graduated. To answer these questions, I designed a study of students attending small liberal arts colleges, the type of college that tried to equalize the experience of students by requiring all students to live on campus and offering small classes with lots of interaction with faculty. These private colleges tend to have more money and resources so they can provide financial aid to low-income students. They also attract some very wealthy students. Because they enroll students across the class spectrum, I would be able to draw comparisons. I ended up spending about four years collecting data, both a survey of more than 2000 students (which formed the basis for quantitative analyses) and qualitative data collection (interviews, focus groups, archival research, and participant observation). This is what we call a “mixed methods” approach because we use both quantitative and qualitative data. The survey gave me a large enough number of students that I could make comparisons of the how many kind, and to be able to say with some authority that there were in fact significant differences in experience and outcome by class (e.g., wealthier students earned more money and had little debt; working-class students often found jobs that were not in their chosen careers and were very affected by debt, upper-middle-class students were more likely to go to graduate school). But the survey analyses could not explain why these differences existed. For that, I needed to talk to people and ask them about their motivations and aspirations. I needed to understand their perceptions of the world, and it is very hard to do this through a survey.

By interviewing students and recent graduates, I was able to discern particular patterns and pathways through college and beyond. Specifically, I identified three versions of gameplay. Upper-middle-class students, whose parents were themselves professionals (academics, lawyers, managers of non-profits), saw college as the first stage of their education and took classes and declared majors that would prepare them for graduate school. They also spent a lot of time building their resumes, taking advantage of opportunities to help professors with their research, or study abroad. This helped them gain admission to highly-ranked graduate schools and interesting jobs in the public sector. In contrast, upper-class students, whose parents were wealthy and more likely to be engaged in business (as CEOs or other high-level directors), prioritized building social capital. They did this by joining fraternities and sororities and playing club sports. This helped them when they graduated as they called on friends and parents of friends to find them well-paying jobs. Finally, low-income, first-generation, and working-class students were often adrift. They took the classes that were recommended to them but without the knowledge of how to connect them to life beyond college. They spent time working and studying rather than partying or building their resumes. All three sets of students thought they were “doing college” the right way, the way that one was supposed to do college. But these three versions of gameplay led to distinct outcomes that advantaged some students over others. I titled my work “Amplified Advantage” to highlight this process.

These three examples, Cory Abramson’s The End Game , Jennifer Peirce’s Racing for Innocence, and my own Amplified Advantage, demonstrate the range of approaches and tools available to the qualitative researcher. They also help explain why qualitative research is so important. Numbers can tell us some things about the world, but they cannot get at the hearts and minds, motivations and beliefs of the people who make up the social worlds we inhabit. For that, we need tools that allow us to listen and make sense of what people tell us and show us. That is what good qualitative research offers us.

How Is This Book Organized?

This textbook is organized as a comprehensive introduction to the use of qualitative research methods. The first half covers general topics (e.g., approaches to qualitative research, ethics) and research design (necessary steps for building a successful qualitative research study). The second half reviews various data collection and data analysis techniques. Of course, building a successful qualitative research study requires some knowledge of data collection and data analysis so the chapters in the first half and the chapters in the second half should be read in conversation with each other. That said, each chapter can be read on its own for assistance with a particular narrow topic. In addition to the chapters, a helpful glossary can be found in the back of the book. Rummage around in the text as needed.

Chapter Descriptions

Chapter 2 provides an overview of the Research Design Process. How does one begin a study? What is an appropriate research question? How is the study to be done – with what methods ? Involving what people and sites? Although qualitative research studies can and often do change and develop over the course of data collection, it is important to have a good idea of what the aims and goals of your study are at the outset and a good plan of how to achieve those aims and goals. Chapter 2 provides a road map of the process.

Chapter 3 describes and explains various ways of knowing the (social) world. What is it possible for us to know about how other people think or why they behave the way they do? What does it mean to say something is a “fact” or that it is “well-known” and understood? Qualitative researchers are particularly interested in these questions because of the types of research questions we are interested in answering (the how questions rather than the how many questions of quantitative research). Qualitative researchers have adopted various epistemological approaches. Chapter 3 will explore these approaches, highlighting interpretivist approaches that acknowledge the subjective aspect of reality – in other words, reality and knowledge are not objective but rather influenced by (interpreted through) people.