- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 03 October 2016

Current state of ethics literature synthesis: a systematic review of reviews

- Marcel Mertz 1 , 2 ,

- Hannes Kahrass 1 &

- Daniel Strech 1

BMC Medicine volume 14 , Article number: 152 ( 2016 ) Cite this article

10k Accesses

42 Citations

10 Altmetric

Metrics details

Modern standards for evidence-based decision making in clinical care and public health still rely solely on eminence-based input when it comes to normative ethical considerations. Manuals for clinical guideline development or health technology assessment (HTA) do not explain how to search, analyze, and synthesize relevant normative information in a systematic and transparent manner. In the scientific literature, however, systematic or semi-systematic reviews of ethics literature already exist, and scholarly debate on their opportunities and limitations has recently bloomed.

A systematic review was performed of all existing systematic or semi-systematic reviews for normative ethics literature on medical topics. The study further assessed how these reviews report on their methods for search, selection, analysis, and synthesis of ethics literature.

We identified 84 reviews published between 1997 and 2015 in 65 different journals and demonstrated an increasing publication rate for this type of review. While most reviews reported on different aspects of search and selection methods, reporting was much less explicit for aspects of analysis and synthesis methods: 31 % did not fulfill any criteria related to the reporting of analysis methods; for example, only 25 % of the reviews reported the ethical approach needed to analyze and synthesize normative information.

Conclusions

While reviews of ethics literature are increasingly published, their reporting quality for analysis and synthesis of normative information should be improved. Guiding questions are: What was the applied ethical approach and technical procedure for identifying and extracting the relevant normative information units? What method and procedure was employed for synthesizing normative information? Experts and stakeholders from bioethics, HTA, guideline development, health care professionals, and patient organizations should work together to further develop this area of evidence-based health care.

Peer Review reports

Decision making in clinical care, public health, biomedical research, and other fields is strongly based on “external” knowledge (e.g., knowledge from clinical trials, health services research, or economic studies). Non-systematic retrieval and appraisal of external information, however, risks several types of bias and therefore diminishes the quality and accountability of decisions. Systematic reviews (SRs) aim to identify and process information from published material in a systematic, transparent, and reproducible manner. Their ultimate goals are to guarantee comprehensiveness and to reduce systematic errors (bias) in the identification and processing of relevant information, and they are therefore conducive to good evidence-based decision making.

Decision making in medicine, research, and health policy often explicitly or implicitly includes normative ethical considerations. For example, should trial participants be granted access to trial drugs after the end of the study? When health professionals and parents disagree about the appropriate course of medical treatment for a child, under what circumstances is the health professional ethically justified in overriding the parents’ wishes? What are ethical arguments for and against sham interventions? Is it allowable to store biological samples and DNA of minors for non-therapeutic research? When is public health surveillance ethical?

Since the rise of scholarly conduct in “applied” ethical analysis in the 1960s and the establishment of institutes for medical ethics, corresponding peer-reviewed journals, conferences, etc., it seems to be unquestioned that normative ethical input in medical and health policy decision making is a professional enterprise that can be more or less appropriate, of high or low quality, etc. However, it is also known that scholars can come to contrasting but equally well-argued conclusions on what is normatively right or wrong, or more or less appropriate [ 1 – 3 ].

Against this background it is surprising that modern standards for evidence-based decision making in clinical care and public health still rely on eminence-based input alone regarding normative ethical information, even though review methodology has been increasingly used in various disciplines and fields.

Scientific communities such as the Cochrane Collaboration, the Campbell Collaboration, and institutions such as the Institute of Medicine (IOM) or the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) provide detailed guidance for review methodologies in different fields [ 4 – 6 ]. While these guidelines cover qualitative as well as quantitative research, they do not explicitly mention whether or how current methodological standards apply to normative ethical literature (“normative literature” for short). Similarly, manuals for evidence-based guideline development do not explain how to include ethical issues in a systematic and transparent manner [ 7 ]. Recent methodological debate demonstrated the need of knowledge synthesis methods that are specified for particular types of information [ 8 ]. But here again, normative ethical information was not acknowledged explicitly.

The ethics literature includes empirical and normative studies on morally challenging topics. Normative literature aims to evaluate or prescribe policies, (moral) reasons, and decisions for or against particular (moral) judgements and policies. Most often, this type of literature can also be described as “argument-based” or “reason-based” literature [ 9 , 10 ]. The “source material” of ethics research includes (ethical) theory, intuitions, common sense, and scientifically produced empirical data.

Despite the neglect of reviews on normative literature by manuals for the development of clinical guidelines and health technology assessment (HTA), and despite any explicit guidance on methodological particularities, such reviews of normative literature already exist, and scholarly debate on their opportunities and limitations has recently bloomed [ 10 – 13 ].

This study aimed to identify trends in the quantity of published systematic and semi-systematic reviews of normative ethical or “mixed” (empirical and normative ethical) literature, the academic affiliations of corresponding authors, and other review characteristics. The study further particularly assessed how these reviews report on their methods for (1) search, (2) selection, (3) analysis, and (4) synthesis of ethics literature.

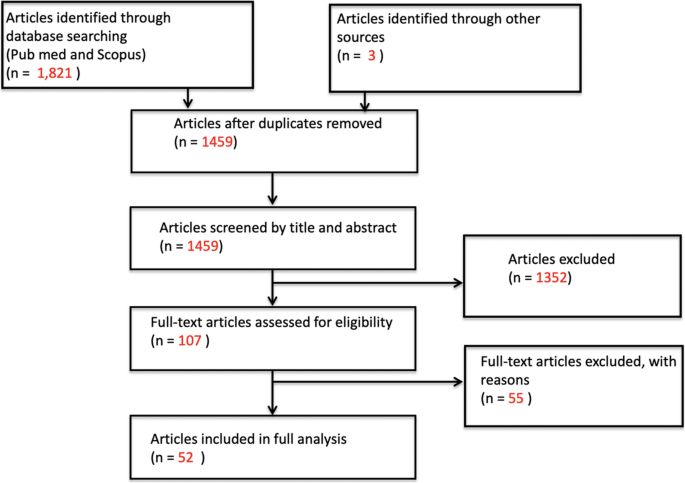

The review was based on two PubMed searches (15 April 2015, 27 April 2015), with additional searches in PhilPapers (29 April 2015) and Google Scholar (30 April 2015). For PubMed , two search strings were used. The first one was composed for screening purposes, and the second one used a refined search string. See Table 1 and the flowchart in Fig. 1 .

Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) flowchart

It proved to be impossible to search directly and solely for reviews of normative literature, as such a distinction is not established or standardized yet in databases (e.g., no standardized key words refer to this kind of review). Therefore, the search had to be intentionally broad in order to capture any review done related to topics of medical ethics or bioethics, even if this included reviews that solely analyzed and synthesized empirical literature.

We have not used a language restriction for the search in order to assess the overall amount of identifiable reviews.

For the purpose of this meta-review on a still little-standardized review area we decided to apply rather sensitive and not too restrictive selection criteria. We selected all reviews that explicitly or implicitly indicated their objective to analyze and present ethics literature in a systematic manner. To be included, reviews had to be explicitly concerned with normative ethical considerations of medical topics; e.g., they had to pose an ethical question or determine ethical challenges. It was not deemed sufficient for the results of a review to be able to be regarded as “ethically relevant.” Furthermore, reviews should have an identifiable description of at least some methodological elements describing a reproducible literature search (e.g., search terms, databases used, or inclusion/exclusion criteria). See Table 2 . We labeled such reviews as semi-systematic reviews . Only those reviews that explicitly or implicitly reported on search, selection, analysis, and synthesis were labeled as (full) systematic reviews . Finally, we only included reviews written in English, German, or French.

Articles were selected first according to their title or abstract, and later by full text screening. See Table 2 . All reviews for empirical, normative, and “mixed” literature were included at this stage. The in-depth analysis and corresponding data presented in this paper focused on the normative and mixed literature, because methodological particularities, especially concerning analysis and synthesis, have been much less widely discussed for normative and conceptual literature than for empirical research.

The selection was initially done by one researcher (MM). Then, a second researcher (HK) checked all the selection results (inclusion and exclusion) for consistency with the selection criteria. Discrepancies were discussed and successfully overcome via consensus-seeking discussions.

Because we aimed to assess the current state of the art of reviews of normative ethical literature, we did not exclude reviews that did not fulfill all PRISMA criteria. Depicting the state of art must also include reviews of “relatively bad” reporting quality. Also, it is possible that certain reviews demonstrate a fair reporting of analysis and synthesis of normative information but are not able to fulfill some basic PRISMA criteria. Excluding such reviews would deprive our review of important insights about how reviews of normative information are analyzing and synthesizing information. Nevertheless, we present slightly adapted PRISMA ratings as part of our results.

Apart from the reporting quality, it would also be impossible to assess the methodological quality of the included reviews because of the lack of specific quality assessment tools for reviews of normative ethics literature.

We determined the academic fields of the journals that published included reviews based on how they were classified by the Journal Citation Reports ( JCR ) Science Edition 2014 and JCR Social Science Edition 2014 . Where no entry was available, the journal was categorized as “not found”.

We further categorized the affiliation of all authors. (Table 4 lists the different categories used.) For this purpose, we considered the affiliation of all first authors. We took the lowest identifiable organizational unit if several organizational units/levels were mentioned. If the last author had a differing affiliation, this affiliation was also considered. Finally, if additional authors of a review had further differing affiliations, these were also considered. Therefore, the amount of authors considered regarding affiliations is not equal to the total amount of authors.

The method of qualitative content analysis (QCA) [ 14 , 15 ] was employed to analyze the literature in detail, i.e., to identify and categorize the methods used for search, selection, analysis, and synthesis, and the information given about methodology (e.g., stating aims, discussing limitations, providing a flowchart). In applying this method, we used a combined deductive and inductive strategy for building up categories [ 14 ]. This was done iteratively by two researchers (MM, HK).

The qualitatively analyzed content of the reviews was synthesized into descriptive statistics assessing how often the description of methods corresponded to established (and slightly adapted) criteria of the PRISMA guideline [ 16 ] (See Table 6 ).

From the initially identified 1393 references we finally included 160 reviews covering three types of ethics reviews: (1) empirical ethics ( n = 76), (2) normative ethics ( n = 51), and (3) mixed literature ( n = 33). For the above-described reasons we further excluded the 76 reviews of empirical ethics literature from the in-depth analysis. See the flowchart in Fig. 1 . The following results therefore represent the remaining 84 reviews of normative or mixed literature. Additional file 1 : Tables S1–S3 present all references for the three types of ethics reviews.

Languages, publication dates, and self-labeling

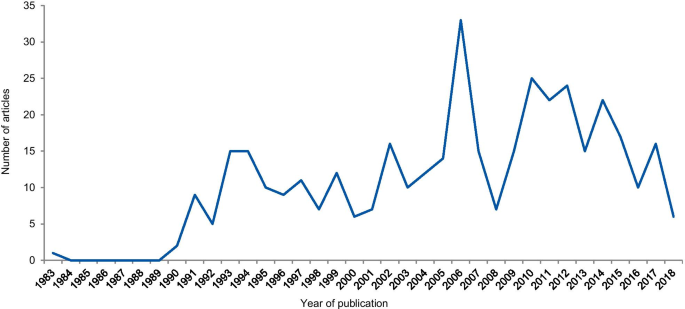

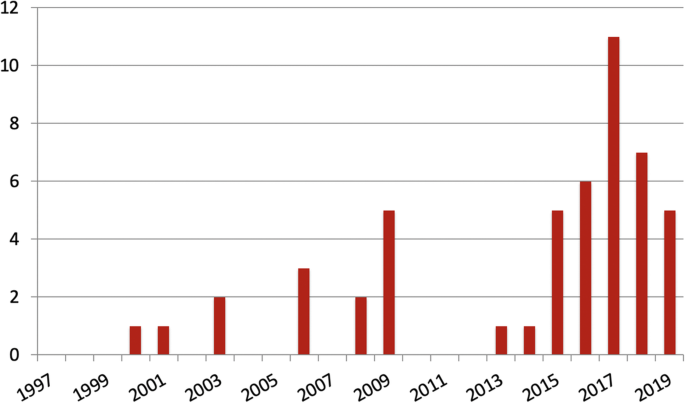

Of all 84 reviews, 98 % ( n = 82) were in English, one in French, and one in German. The earliest reviews were published in 1997. Of the 84 reviews, 82 % were published in the last ten years. See Fig. 2 . In total, 31 (37 %) labeled themselves as “systematic review” or used the term “systematic” in labelings such as “systematic literature review” or “systematic survey.”

Publication dates of the reviews

Journals: academic fields and titles

The academic fields most prominent were Nursing ( n = 17, 15 %), Medical Ethics and Ethics ( n = 10 + 2 = 12, 11 %), Public, Environmental, and Occupational Health ( n = 8, 7 %), and Genetics and Heredity ( n = 8, 7 %). See Table 3 . Note that a journal can be classified in two or more fields.

The journal that published the most reviews was Nursing Ethics ( n = 7, 8 %), followed by Journal of Medical Ethics ( n = 4, 5 %), BMC Medical Ethics ( n = 4, 5 %), Journal of Advanced Nursing ( n = 4, 5 %), and European Journal of Human Genetics ( n = 4, 5 %). However, roughly 70 % ( n = 59) of all finally included reviews ( n = 84) were found in journals that only appeared once in our review. See Table 3 .

Authors: number, country of origin, and affiliations

The greatest number of reviews were authored by two authors ( n = 26, 31 %), followed by three ( n = 18, 21 %) and four authors ( n = 16, 19 %) with an arithmetic mean of 3.45. See Table 4 .

Twenty reviews (24 %) were written by authors from the USA, 10 (12 %) from the UK, 10 (12 %) from Belgium, 8 (10 %) from Germany, and 6 (8 %) from the Netherlands. The remaining 30 reviews were written by authors from 18 other countries. See Table 4 .

We analyzed the affiliation of 205 authors with different affiliations. The greatest number, namely 60 (30 %), were affiliated to Bioethics institutions, 51 (25 %) to institutions related to medicine, 23 (11 %) to Nursing and Allied Health Practitioners (AHP)-related institutions, 18 (9 %) to Health Sciences institutions, and 7 (3 %) were affiliated to Philosophy and the Humanities. See Table 4 .

Standards/guidelines and limitations

Twenty (24 %) of the 84 reviews stated that they used an established/published review methodology (see Table 5 ). Only the approach of McCullough et al. and Garrard were mentioned more than once ( n = 9, 45 %, n = 2, 10 %). Ten reviews (12 %) stated that they took guidance from established reporting standards or guidelines (whether general or specific to SRs). The only standard mentioned more than once was PRISMA, with 8 entries. Thirty-three reviews (39 %) reported on limitations.

Reported methods for search, selection, analysis, and synthesis

Table 6 presents detailed data on how often the reviews were transparent about methodological criteria for search, selection, analysis, and synthesis. Table 6 also highlights how these criteria match with reporting items mentioned in PRISMA. Most reviews reported, for example, on what databases (93 %), search terms (91 %), or inclusion/exclusion criteria (81 %) they used. Overall, only 1 % and 8 % did not fulfill any criteria related to search and selection, respectively. However, only a minority reported on other essential details such as the procedure for information extraction (37 %) and information synthesis (18 %). In fact, 31 % did not fulfill any criteria related to the reporting of analysis methods. For example, only 25 % of the reviews reported the ethical approach needed to analyze and synthesize normative information.

A comprehensive qualitative analysis and comparison of all applied methods for search, selection, analysis, and synthesis is beyond the scope of this paper and is to be published elsewhere. The applied methods for search and selection of relevant normative literature are largely comparable with standard “systematic review” methodology. Methods for analysis and synthesis of normative information, however, are of substantial differences. In the following, therefore, we highlight some core findings with regard to the reported analysis and synthesis.

Regarding extraction and analysis of normative information, the most sought types of information were ethical issues, topics, or dilemmas ( n = 27), arguments or reasons ( n = 14), and ethical principles, values, or norms ( n = 13) (multiple responses possible). Among the procedures for extracting information we broadly distinguished between “coding and categorizing” ( n = 9), “collecting” ( n = 7), or “close reading” ( n = 6). See Table 7 for more detailed explanations and case examples.

Regarding synthesis, we could broadly distinguish between qualitative methods ( n = 44), quantitative methods ( n = 5), and narrative/hermeneutical methods ( n = 3). In most cases, qualitative analyses aimed to develop overarching normative issues, reasons, or principles that allowed summarizing the more detailed normative information. To do this, a variety of deductively and inductively developed category systems with main and subcategories were employed. Quantitative analyses aimed, for example, to quantify the distribution of qualitatively assessed topics. See Table 8 for more detailed explanations and case examples.

Thirty-eight (45 %) of the included reviews ( n = 84) reported on at least some aspects of all four domains of the methodology (search, selection, analysis, and synthesis).

Most reviews reported on the essential elements for search and selection methods (e.g., databases, search terms, inclusion/exclusion) except for flowcharts (reported by only 29 %). However, reporting was much less explicit for analysis and synthesis methods. Almost one third of all reviews did not report on any essential element of the analysis methods (what information to extract and how). For example, only 25 % of reviews on normative literature reported on the kind of ethical approach/theory needed to identify relevant normative information. Only 45 % of reviews reported on all methods and could therefore be labeled as (full) systematic reviews, implying that most reviews we found are rather semi-systematic. Somehow in line with the aforementioned neglect of important method reporting is the fact that only 39 % of reviews discussed their limitations.

A limitation of our review is that we only searched the databases PubMed, PhilPapers, and Google Scholar . We restricted our search to these three databases mainly because of experiences from former systematic reviews of normative information demonstrating that most of the literature can be found in PubMed and Google Scholar , and that searching other ethics-specific databases did not add a substantial proportion of references [ 17 ]. In our review, 86 % of all included reviews were found by PubMed searches alone. Furthermore, all languages other than English, German, or French were excluded, but this only resulted in the exclusion of three reviews.

Our results demonstrate that most elements of searching and selecting normative literature reflect the widely accepted PRISMA recommendations. However, appropriate elements for the analysis and synthesis of normative literature are less standardized. Further meta-research and conceptual analysis are needed to inform the development of minimal standards for the analysis and synthesis of normative literature. The quality assessment of normative literature might be one of the most controversial topics in this regard [ 10 ]. The required degree of transparency for all steps of information processing in analyzing and synthesizing normative information will be another controversial topic, because strong requirements in this regard might result in excessive workloads for review authors [ 18 ].

Nevertheless, our review demonstrates that analysis and synthesis methods can be described and justified with regard to the specific review objectives. This demands that the following elements for analysis and synthesis should be clarified prior to each review of normative information and should be reported with the dissemination of results: (1) normative information unit (e.g., ethical issues, ethical reasons, ethical norms, etc.), (2) ethical approach (e.g., a specific ethical theory) and the technical procedure used to identify and extract the relevant normative information units, (3) method for synthesizing normative information (e.g., category building). See Tables 7 and 8 . Researchers should also be aware that these three steps are interrelated; i.e., that using a specific ethical approach will lead to a specific way of identifying normative information units, or, vice versa, that the set of normative information units identified will depend on the ethical approach (e.g., a deontological ethical theory would identify some issues as “ethical issues,” which a consequentialist ethical theory would not).

Thus, future clarification is also needed for the personal competencies and skills necessary to realize a valid and informative review of normative information. Based on our personal experiences with reviews of normative information, it is also important to clarify the expectations and needs of the intended readership. In particular, the choice of synthesis methods for normative information might differ substantially if the review group aims to inform either expert discourse in bioethics or policy decision making in guideline or HTA development. Stakeholder orientation, therefore, is another issue that should be clarified prior to conducting ethics reviews.

This is the first study, to our knowledge, to analyze the state of systematic and semi-systematic reviews of normative literature on medical topics. We identified 84 reviews published between 1997 and 2015 in 65 different journals and demonstrated an increasing publication rate for this type of review. The reference lists for all included reviews (Additional file 1 : Tables S1–S3) provide a rich source for those interested in medical ethics and those wanting to conduct (systematic) reviews of normative literature themselves.

Further research as well as interdisciplinary discussion and consent are needed to define detailed best practice recommendations for the respective steps of a review of normative information. Experts from different fields such as bioethics, HTA and guideline development, as well as health care professionals and patient representatives, should work together to further develop the methodology of (systematic) reviews of normative ethical information to support evidence-based health care.

Sugarman J, Sulmasy DP. Methods in medical ethics. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press; 2010.

Google Scholar

Yoder SD. The nature of ethical expertise. Hastings Cent Rep. 1998;28(6):11–9.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Brock DW. Truth or consequences: the role of philosophers in policy-making. Ethics. 1987;97(4):786–91.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Institute of Medicine, Committee on Standards for Systematic Reviews of Comparative Effectiveness Research, Eden J, Levit LA, Berg AO, Morton SC, editors. Finding what works in health care: standards for systematic reviews. Washington, DC; The National Academies Press; 2011.

Higgins JPT, Green S, editors. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Oxford: The Cochrane Collaboration; 2011.

Petticrew M, Roberts H. Systematic reviews in the social sciences: a practical guide. Malden, MA; Oxford: Blackwell; 2006.

Book Google Scholar

Knüppel H, Mertz M, Schmidhuber M, Neitzke G, Strech D. Inclusion of ethical issues in dementia guidelines: a thematic text analysis. PLoS Med. 2013;10(8):e1001498.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Straus SE, Kastner M, Soobiah C, Antony J, Tricco AC. Engaging researchers on developing, using, and improving knowledge synthesis methods: introduction to a series of articles describing the results of a scoping review on emerging knowledge synthesis methods. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016;73:15–8.

McCullough LB, Coverdale JH, Chervenak FA. Constructing a systematic review for argument-based clinical ethics literature: the example of concealed medications. J Med Philos. 2007;32(1):65–76.

Sofaer N, Strech D. The need for systematic reviews of reasons. Bioethics. 2012;26(6):315–28.

Davies R, Ives J, Dunn M. A systematic review of empirical bioethics methodologies. BMC Med Ethics. 2015;16:15.

McDougall RJ, Notini L. Overriding parents’ medical decisions for their children: a systematic review of normative literature. J Med Ethics. 2014;40(7):448–52.

Mertz M, Sofaer N, Strech D. Did we describe what you meant? Findings and methodological discussion of an empirical validation study for a systematic review of reasons. BMC Med Ethics. 2014;15:69.

Schreier M. Qualitative content analysis in practice. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2012.

Mayring P. Qualitative Inhaltsanalyse: Grundlagen und Techniken. Weinheim: Beltz; 2010.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, The PG. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097.

Strech D, Sofaer N. How to write a systematic review of reasons. J Med Ethics. 2012;38(2):121–6.

Mertz M, Strech D. Systematic and transparent inclusion of ethical issues and recommendations in clinical practice guidelines: a six-step approach. Implement Sci. 2014;9:184.

McDougall R. Reviewing literature in bioethics research: increasing rigour in non-systematic reviews. Bioethics. 2015;29(7):523–8.

McCullough LB, Coverdale JH, Chervenak FA. Argument-based medical ethics: a formal tool for critically appraising the normative medical ethics literature. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;191(4):1097–102.

Droste S, Gerhardus A. Ethische Aspekte in Kurz-HTA-Berichten: Eine systematische Übersicht. ZEFQ. 2003;97(10):711–5.

Vergnes JN, Marchal-Sixou C, Nabet C, Maret D, Hamel O. Ethics in systematic reviews. J Med Ethics. 2010;36(12):771–4.

Higgins JPT, Green S (editors). Cochrane Handbook forSystematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]. The Cochrane Collaboration. Available from www.handbook.cochrane.org

Stroup DF, et al. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) group. JAMA. 2000;283(15):2008–12.

Institute of Medicine. Finding What Works in Health Care: Standards for Systematic Reviews. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2011.

Garrard J. Health sciences literature review made easy: the matrix method. Jones & Bartlett Learning 1999

Aveyard H. Doing a literature review in health and social care: a practical guide. Open University Press 2012

Jesson J, Matheson K, Lacey FM. Doing your literature review. Traditional and systematic techniques. SAGE Publications Ltd. 2011.

Centre for Reviews and Dissemination: Systematic reviews. CRD’s guidance for undertaking reviews in health care. York Publishing Services Ltd 2008

Hofmann B. Toward a procedure for integrating moral issues in health technology assessment. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2005;21(3):312–8.

Whittemore R, Knafl K. The integrative review: updated methodology. J Adv Nurs. 2005;2(5):546–53.

Aluas M, Colombetti E, Osimani B, Musio A, Pessina A. Disability, human rights, and the International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health: systematic review. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2012;91(13 Suppl 1):S146–154.

Monteiro MAA, Barbosa RCM, Barroso MGT, Vieira NFC, Pinheiro AKB. Ethical dilemmas experienced by nurses presented in nursing publications. Revista Latino-Americana de Enfermagem. 2008;16:1054–9.

Wernow JR, Gastmans C. A review and taxonomy of argument-based ethics literature regarding conscientious objections to end-of-life procedures. Christ Bioeth. 2010;16(3):274–95.

Article Google Scholar

Ashcroft RE, Chadwick DW, Clark SR, Edwards RH, Frith L, Hutton JL. Implications of socio-cultural contexts for the ethics of clinical trials. Health Technol Assess. 1997;1(9). 1–65.

Borry P, Stultiens L, Nys H, Cassiman JJ, Dierickx K. Presymptomatic and predictive genetic testing in minors: a systematic review of guidelines and position papers. Clin Genet. 2006;70(5):374–81.

Caplan L, Hoffecker L, Prochazka AV. Ethics in the rheumatology literature: a systematic review. Arthritis Care Res. 2008;59(6):816–21.

Chung KC, Pushman AG, Bellfi LT. A systematic review of ethical principles in the plastic surgery literature. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;124(5):1711–8.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Fourie C, Biller-Andorno N, Wild V. Systematically evaluating the impact of diagnosis-related groups (DRGs) on health care delivery: a matrix of ethical implications. Health Policy. 2014;115(2–3):157–64.

Naudé AM, Bornman J. A systematic review of ethics knowledge in audiology (1980–2010). Am J Audiol. 2014;23(2):151–7.

Thys K, Van Assche K, Nobile H, Siebelink M, Aujoulat I, Schotsmans P, Dobbels F, Borry P. Could minors be living kidney donors? A systematic review of guidelines, position papers and reports. Transpl Int. 2013;26(10):949–60.

Schleidgen S, Klingler C, Bertram T, Rogowski WH, Marckmann G. What is personalized medicine: sharpening a vague term based on a systematic literature review. BMC Med Ethics. 2013;14:55.

Niemansburg SL, van Delden JJ, Dhert WJ, Bredenoord AL. Reconsidering the ethics of sham interventions in an era of emerging technologies. Surgery. 2015;157(4):801–10.

Zwijsen SA, Niemeijer AR, Hertogh CM. Ethics of using assistive technology in the care for community-dwelling elderly people: an overview of the literature. Aging Ment Health. 2011;15(4):419–27.

Heilferty CM. Ethical considerations in the study of online illness narratives: a qualitative review. J Adv Nurs. 2011;67(5):945–53.

Shahriari M, Mohammadi E, Abbaszadeh A, Bahrami M. Nursing ethical values and definitions: a literature review. Iran J Nurs Midwifery Res. 2013;18(1):1–8.

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Christenhusz GM, Devriendt K, Dierickx K. To tell or not to tell? A systematic review of ethical reflections on incidental findings arising in genetics contexts. Eur J Hum Genet. 2013;21(3):248–55.

Kölch M, Ludolph AG, Plener PL, Fangerau H, Vitiello B, Fegert JM. Safeguarding children’s rights in psychopharmacological research: ethical and legal issues. Curr Pharm Des. 2010;16(22):2398–406.

Hanlon C, Tesfaye M, Wondimagegn D, Shibre T. Ethical and professional challenges in mental health care in low- and middle-income countries. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2010;22(3):245–51.

Download references

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank our student assistant Nadine Komeinda for her help in retrieving and electronically archiving the full text versions of the articles we found, and our student assistant Christopher Schürmann for his help in analyzing review characteristics.

Authors’ contributions

MM wrote the main draft of the paper (all sections), devised search algorithms and conducted the search, worked out most of the methods employed, and revised and finalized the manuscript. HK assisted in devising the search algorithms, cross-checked selection, was one of two researchers analyzing and synthesizing the material, and contributed to writing the manuscript. DS originated the idea of conducting a systematic review about reviews of normative ethical literature on medical topics, gave input to the review design, acted as third (“control”) researcher in the analysis procedure, and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

Financial competing interests: There are none to declare. Non-financial competing interests: In three reviews finally included in this review DS was one of the authors. In one review MM and HK were co-authors.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Institute of History, Ethics and Philosophy of Medicine, Hannover Medical School, Hannover, Germany

Marcel Mertz, Hannes Kahrass & Daniel Strech

Research Unit Ethics, Institute of History and Ethics of Medicine, University Hospital Cologne, Cologne, Germany

Marcel Mertz

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Daniel Strech .

Additional file

Additional file 1: table s1..

Reviews (English/German/French): empirical literature. Table S2 : Reviews (English/German/French): normative literature. Table S3 : Reviews (English/German/French): mixed literature. (DOCX 56 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Mertz, M., Kahrass, H. & Strech, D. Current state of ethics literature synthesis: a systematic review of reviews. BMC Med 14 , 152 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-016-0688-1

Download citation

Received : 29 June 2016

Accepted : 08 September 2016

Published : 03 October 2016

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-016-0688-1

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Systematic review

- Literature review

- Normative literature

- Argument-based literature

- Empirical ethics

- Literature search

- Evidence-based medicine

BMC Medicine

ISSN: 1741-7015

- Submission enquiries: [email protected]

- General enquiries: [email protected]

- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 30 April 2021

A scoping review of the literature featuring research ethics and research integrity cases

- Anna Catharina Vieira Armond ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-7121-5354 1 ,

- Bert Gordijn 2 ,

- Jonathan Lewis 2 ,

- Mohammad Hosseini 2 ,

- János Kristóf Bodnár 1 ,

- Soren Holm 3 , 4 &

- Péter Kakuk 5

BMC Medical Ethics volume 22 , Article number: 50 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

14k Accesses

25 Citations

28 Altmetric

Metrics details

The areas of Research Ethics (RE) and Research Integrity (RI) are rapidly evolving. Cases of research misconduct, other transgressions related to RE and RI, and forms of ethically questionable behaviors have been frequently published. The objective of this scoping review was to collect RE and RI cases, analyze their main characteristics, and discuss how these cases are represented in the scientific literature.

The search included cases involving a violation of, or misbehavior, poor judgment, or detrimental research practice in relation to a normative framework. A search was conducted in PubMed, Web of Science, SCOPUS, JSTOR, Ovid, and Science Direct in March 2018, without language or date restriction. Data relating to the articles and the cases were extracted from case descriptions.

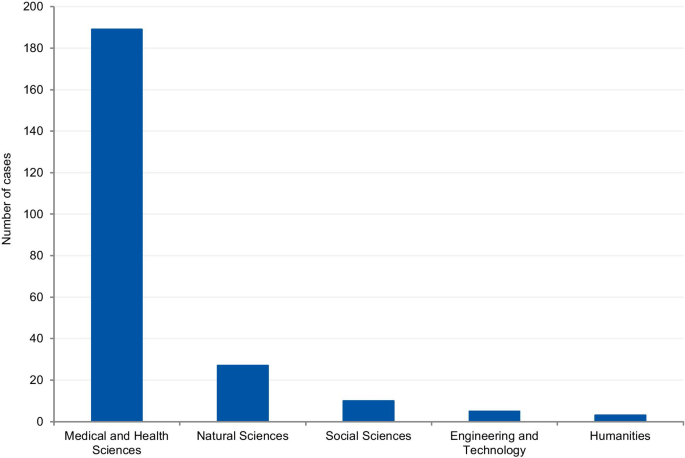

A total of 14,719 records were identified, and 388 items were included in the qualitative synthesis. The papers contained 500 case descriptions. After applying the eligibility criteria, 238 cases were included in the analysis. In the case analysis, fabrication and falsification were the most frequently tagged violations (44.9%). The non-adherence to pertinent laws and regulations, such as lack of informed consent and REC approval, was the second most frequently tagged violation (15.7%), followed by patient safety issues (11.1%) and plagiarism (6.9%). 80.8% of cases were from the Medical and Health Sciences, 11.5% from the Natural Sciences, 4.3% from Social Sciences, 2.1% from Engineering and Technology, and 1.3% from Humanities. Paper retraction was the most prevalent sanction (45.4%), followed by exclusion from funding applications (35.5%).

Conclusions

Case descriptions found in academic journals are dominated by discussions regarding prominent cases and are mainly published in the news section of journals. Our results show that there is an overrepresentation of biomedical research cases over other scientific fields compared to its proportion in scientific publications. The cases mostly involve fabrication, falsification, and patient safety issues. This finding could have a significant impact on the academic representation of misbehaviors. The predominance of fabrication and falsification cases might diverge the attention of the academic community from relevant but less visible violations, and from recently emerging forms of misbehaviors.

Peer Review reports

There has been an increase in academic interest in research ethics (RE) and research integrity (RI) over the past decade. This is due, among other reasons, to the changing research environment with new and complex technologies, increased pressure to publish, greater competition in grant applications, increased university-industry collaborative programs, and growth in international collaborations [ 1 ]. In addition, part of the academic interest in RE and RI is due to highly publicized cases of misconduct [ 2 ].

There is a growing body of published RE and RI cases, which may contribute to public attitudes regarding both science and scientists [ 3 ]. Different approaches have been used in order to analyze RE and RI cases. Studies focusing on ORI files (Office of Research Integrity) [ 2 ], retracted papers [ 4 ], quantitative surveys [ 5 ], data audits [ 6 ], and media coverage [ 3 ] have been conducted to understand the context, causes, and consequences of these cases.

Analyses of RE and RI cases often influence policies on responsible conduct of research [ 1 ]. Moreover, details about cases facilitate a broader understanding of issues related to RE and RI and can drive interventions to address them. Currently, there are no comprehensive studies that have collected and evaluated the RE and RI cases available in the academic literature. This review has been developed by members of the EnTIRE consortium to generate information on the cases that will be made available on the Embassy of Good Science platform ( www.embassy.science ). Two separate analyses have been conducted. The first analysis uses identified research articles to explore how the literature presents cases of RE and RI, in relation to the year of publication, country, article genre, and violation involved. The second analysis uses the cases extracted from the literature in order to characterize the cases and analyze them concerning the violations involved, sanctions, and field of science.

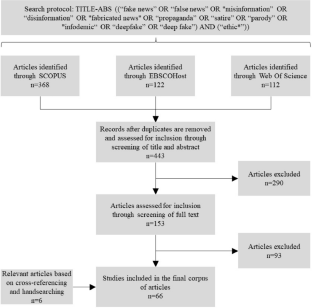

This scoping review was performed according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement and PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR). The full protocol was pre-registered and it is available at https://ec.europa.eu/research/participants/documents/downloadPublic?documentIds=080166e5bde92120&appId=PPGMS .

Eligibility

Articles with non-fictional case(s) involving a violation of, or misbehavior, poor judgment, or detrimental research practice in relation to a normative framework, were included. Cases unrelated to scientific activities, research institutions, academic or industrial research and publication were excluded. Articles that did not contain a substantial description of the case were also excluded.

A normative framework consists of explicit rules, formulated in laws, regulations, codes, and guidelines, as well as implicit rules, which structure local research practices and influence the application of explicitly formulated rules. Therefore, if a case involves a violation of, or misbehavior, poor judgment, or detrimental research practice in relation to a normative framework, then it does so on the basis of explicit and/or implicit rules governing RE and RI practice.

Search strategy

A search was conducted in PubMed, Web of Science, SCOPUS, JSTOR, Ovid, and Science Direct in March 2018, without any language or date restrictions. Two parallel searches were performed with two sets of medical subject heading (MeSH) terms, one for RE and another for RI. The parallel searches generated two sets of data thereby enabling us to analyze and further investigate the overlaps in, differences in, and evolution of, the representation of RE and RI cases in the academic literature. The terms used in the first search were: (("research ethics") AND (violation OR unethical OR misconduct)). The terms used in the parallel search were: (("research integrity") AND (violation OR unethical OR misconduct)). The search strategy’s validity was tested in a pilot search, in which different keyword combinations and search strings were used, and the abstracts of the first hundred hits in each database were read (Additional file 1 ).

After searching the databases with these two search strings, the titles and abstracts of extracted items were read by three contributors independently (ACVA, PK, and KB). Articles that could potentially meet the inclusion criteria were identified. After independent reading, the three contributors compared their results to determine which studies were to be included in the next stage. In case of a disagreement, items were reassessed in order to reach a consensus. Subsequently, qualified items were read in full.

Data extraction

Data extraction processes were divided by three assessors (ACVA, PK and KB). Each list of extracted data generated by one assessor was cross-checked by the other two. In case of any inconsistencies, the case was reassessed to reach a consensus. The following categories were employed to analyze the data of each extracted item (where available): (I) author(s); (II) title; (III) year of publication; (IV) country (according to the first author's affiliation); (V) article genre; (VI) year of the case; (VII) country in which the case took place; (VIII) institution(s) and person(s) involved; (IX) field of science (FOS-OECD classification)[ 7 ]; (X) types of violation (see below); (XI) case description; and (XII) consequences for persons or institutions involved in the case.

Two sets of data were created after the data extraction process. One set was used for the analysis of articles and their representation in the literature, and the other set was created for the analysis of cases. In the set for the analysis of articles, all eligible items, including duplicate cases (cases found in more than one paper, e.g. Hwang case, Baltimore case) were included. The aim was to understand the historical aspects of violations reported in the literature as well as the paper genre in which cases are described and discussed. For this set, the variables of the year of publication (III); country (IV); article genre (V); and types of violation (X) were analyzed.

For the analysis of cases, all duplicated cases and cases that did not contain enough information about particularities to differentiate them from others (e.g. names of the people or institutions involved, country, date) were excluded. In this set, prominent cases (i.e. those found in more than one paper) were listed only once, generating a set containing solely unique cases. These additional exclusion criteria were applied to avoid multiple representations of cases. For the analysis of cases, the variables: (VI) year of the case; (VII) country in which the case took place; (VIII) institution(s) and person(s) involved; (IX) field of science (FOS-OECD classification); (X) types of violation; (XI) case details; and (XII) consequences for persons or institutions involved in the case were considered.

Article genre classification

We used ten categories to capture the differences in genre. We included a case description in a “news” genre if a case was published in the news section of a scientific journal or newspaper. Although we have not developed a search strategy for newspaper articles, some of them (e.g. New York Times) are indexed in scientific databases such as Pubmed. The same method was used to allocate case descriptions to “editorial”, “commentary”, “misconduct notice”, “retraction notice”, “review”, “letter” or “book review”. We applied the “case analysis” genre if a case description included a normative analysis of the case. The “educational” genre was used when a case description was incorporated to illustrate RE and RI guidelines or institutional policies.

Categorization of violations

For the extraction process, we used the articles’ own terminology when describing violations/ethical issues involved in the event (e.g. plagiarism, falsification, ghost authorship, conflict of interest, etc.) to tag each article. In case the terminology was incompatible with the case description, other categories were added to the original terminology for the same case. Subsequently, the resulting list of terms was standardized using the list of major and minor misbehaviors developed by Bouter and colleagues [ 8 ]. This list consists of 60 items classified into four categories: Study design, data collection, reporting, and collaboration issues. (Additional file 2 ).

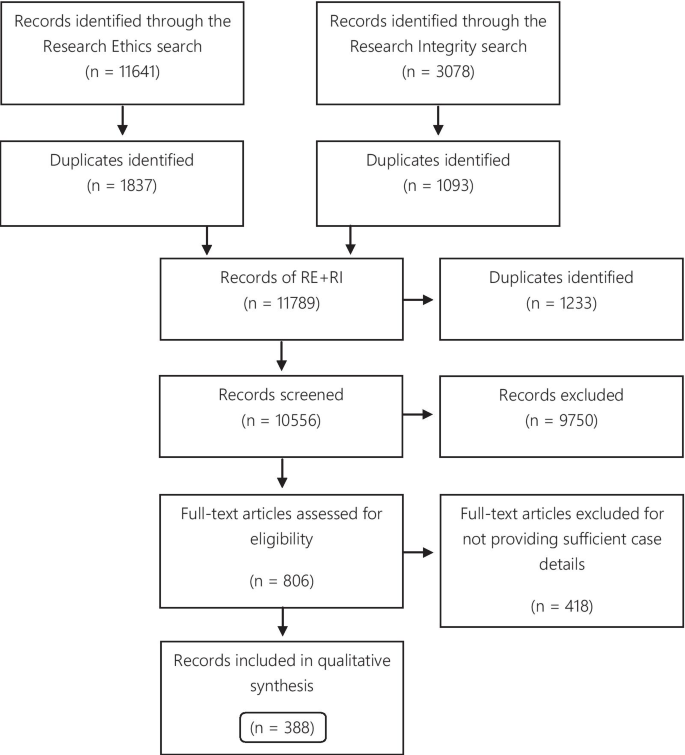

Systematic search

A total of 11,641 records were identified through the RE search and 3078 in the RI search. The results of the parallel searches were combined and the duplicates removed. The remaining 10,556 records were screened, and at this stage, 9750 items were excluded because they did not fulfill the inclusion criteria. 806 items were selected for full-text reading. Subsequently, 388 articles were included in the qualitative synthesis (Fig. 1 ).

Flow diagram

Of the 388 articles, 157 were only identified via the RE search, 87 exclusively via the RI search, and 144 were identified via both search strategies. The eligible articles contained 500 case descriptions, which were used for the analysis of the publications articles analysis. 256 case descriptions discussed the same 50 cases. The Hwang case was the most frequently described case, discussed in 27 articles. Furthermore, the top 10 most described cases were found in 132 articles (Table 1 ).

For the analysis of cases, 206 (41.2% of the case descriptions) duplicates were excluded, and 56 (11.2%) cases were excluded for not providing enough information to distinguish them from other cases, resulting in 238 eligible cases.

Analysis of the articles

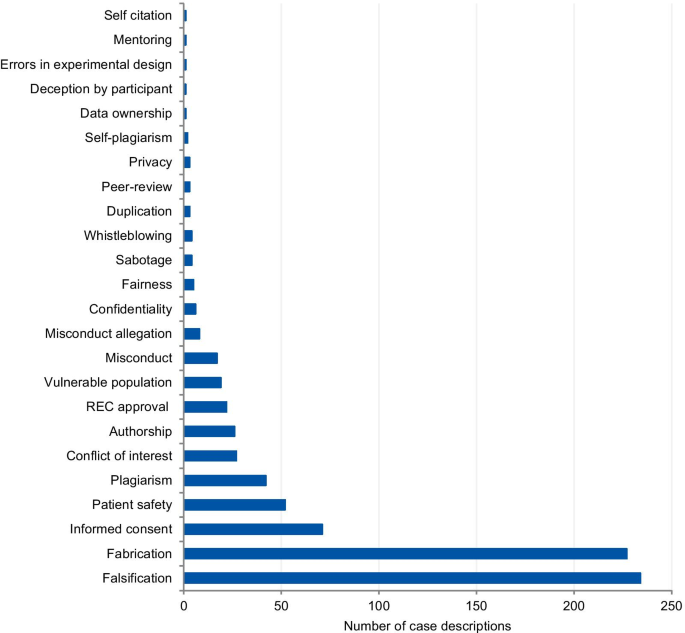

The categories used to classify the violations include those that pertain to the different kinds of scientific misconduct (falsification, fabrication, plagiarism), detrimental research practices (authorship issues, duplication, peer-review, errors in experimental design, and mentoring), and “other misconduct” (according to the definitions from the National Academies of Sciences and Medicine, [ 1 ]). Each case could involve more than one type of violation. The majority of cases presented more than one violation or ethical issue, with a mean of 1.56 violations per case. Figure 2 presents the frequency of each violation tagged to the articles. Falsification and fabrication were the most frequently tagged violations. The violations accounted respectively for 29.1% and 30.0% of the number of taggings (n = 780), and they were involved in 46.8% and 45.4% of the articles (n = 500 case descriptions). Problems with informed consent represented 9.1% of the number of taggings and 14% of the articles, followed by patient safety (6.7% and 10.4%) and plagiarism (5.4% and 8.4%). Detrimental research practices, such as authorship issues, duplication, peer-review, errors in experimental design, mentoring, and self-citation were mentioned cumulatively in 7.0% of the articles.

Tagged violations from the article analysis

Analysis of the cases

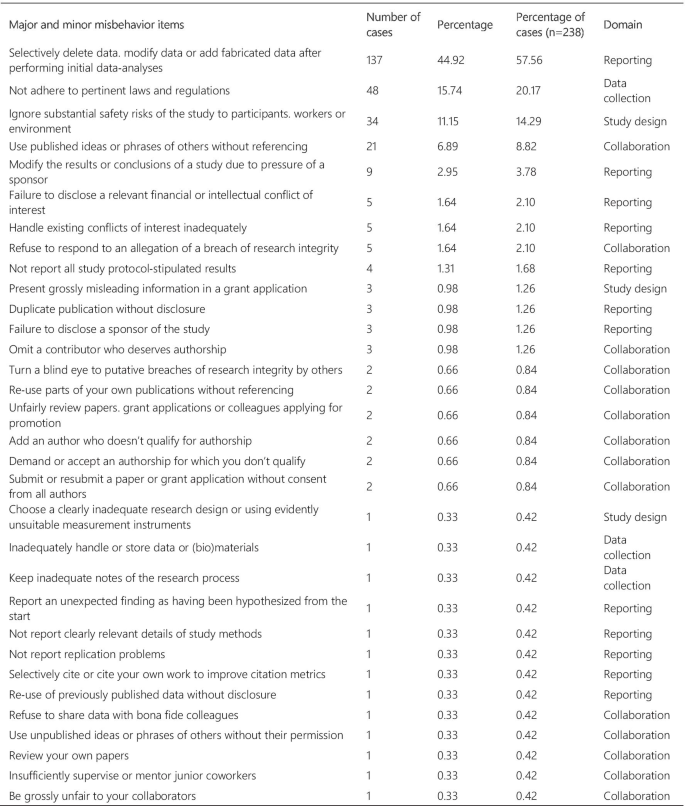

Figure 3 presents the frequency and percentage of each violation found in the cases. Each case could include more than one item from the list. The 238 cases were tagged 305 times, with a mean of 1.28 items per case. Fabrication and falsification were the most frequently tagged violations (44.9%), involved in 57.7% of the cases (n = 238). The non-adherence to pertinent laws and regulations, such as lack of informed consent and REC approval, was the second most frequently tagged violation (15.7%) and involved in 20.2% of the cases. Patient safety issues were the third most frequently tagged violations (11.1%), involved in 14.3% of the cases, followed by plagiarism (6.9% and 8.8%). The list of major and minor misbehaviors [ 8 ] classifies the items into study design, data collection, reporting, and collaboration issues. Our results show that 56.0% of the tagged violations involved issues in reporting, 16.4% in data collection, 15.1% involved collaboration issues, and 12.5% in the study design. The items in the original list that were not listed in the results were not involved in any case collected.

Major and minor misbehavior items from the analysis of cases

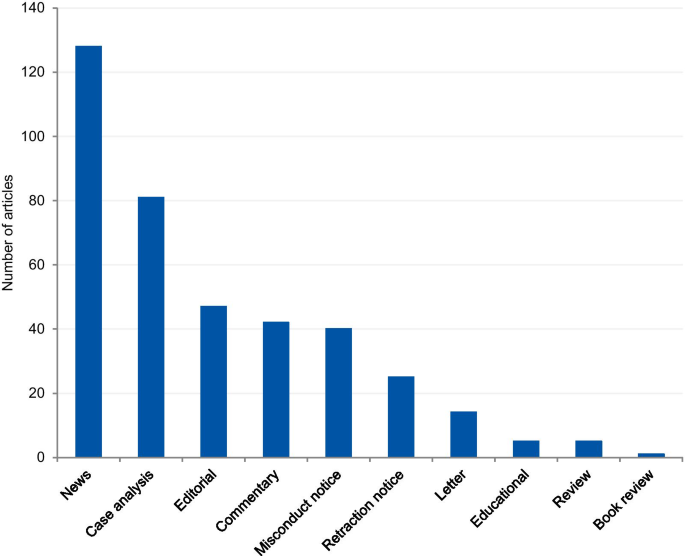

Article genre

The articles were mostly classified into “news” (33.0%), followed by “case analysis” (20.9%), “editorial” (12.1%), “commentary” (10.8%), “misconduct notice” (10.3%), “retraction notice” (6.4%), “letter” (3.6%), “educational paper” (1.3%), “review” (1%), and “book review” (0.3%) (Fig. 4 ). The articles classified into “news” and “case analysis” included predominantly prominent cases. Items classified into “news” often explored all the investigation findings step by step for the associated cases as the case progressed through investigations, and this might explain its high prevalence. The case analyses included mainly normative assessments of prominent cases. The misconduct and retraction notices included the largest number of unique cases, although a relatively large portion of the retraction and misconduct records could not be included because of insufficient case details. The articles classified into “editorial”, “commentary” and “letter” also included unique cases.

Article genre of included articles

Article analysis

The dates of the eligible articles range from 1983 to 2018 with notable peaks between 1990 and 1996, most probably associated with the Gallo [ 9 ] and Imanishi-Kari cases [ 10 ], and around 2005 with the Hwang [ 11 ], Wakefield [ 12 ], and CNEP trial cases [ 13 ] (Fig. 5 ). The trend line shows an increase in the number of articles over the years.

Frequency of articles according to the year of publication

Case analysis

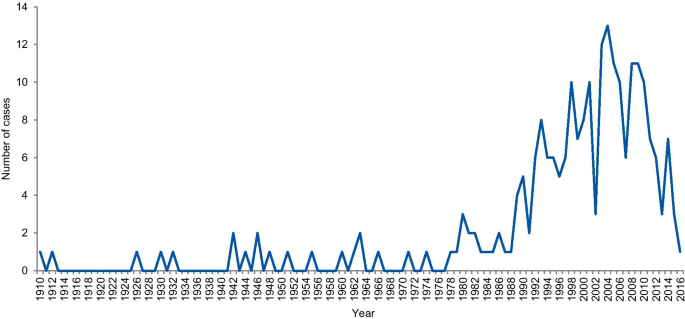

The dates of included cases range from 1798 to 2016. Two cases occurred before 1910, one in 1798 and the other in 1845. Figure 6 shows the number of cases per year from 1910. An increase in the curve started in the early 1980s, reaching the highest frequency in 2004 with 13 cases.

Frequency of cases per year

Geographical distribution

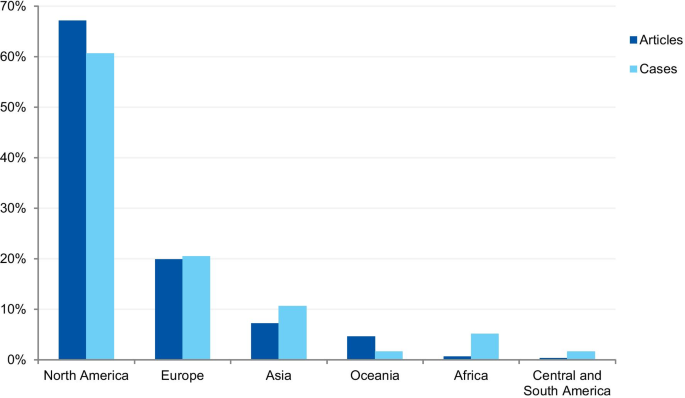

The first analysis concerned the authors’ affiliation and the corresponding author’s address. Where the article contained more than one country in the affiliation list, only the first author’s location was considered. Eighty-one articles were excluded because the authors’ affiliations were not available, and 307 articles were included in the analysis. The articles originated from 26 different countries (Additional file 3 ). Most of the articles emanated from the USA and the UK (61.9% and 14.3% of articles, respectively), followed by Canada (4.9%), Australia (3.3%), China (1.6%), Japan (1.6%), Korea (1.3%), and New Zealand (1.3%). Some of the most discussed cases occurred in the USA; the Imanishi-Kari, Gallo, and Schön cases [ 9 , 10 ]. Intensely discussed cases are also associated with Canada (Fisher/Poisson and Olivieri cases), the UK (Wakefield and CNEP trial cases), South Korea (Hwang case), and Japan (RIKEN case) [ 12 , 14 ]. In terms of percentages, North America and Europe stand out in the number of articles (Fig. 7 ).

Percentage of articles and cases by continent

The case analysis involved the location where the case took place, taking into account the institutions involved in the case. For cases involving more than one country, all the countries were considered. Three cases were excluded from the analysis due to insufficient information. In the case analysis, 40 countries were involved in 235 different cases (Additional file 4 ). Our findings show that most of the reported cases occurred in the USA and the United Kingdom (59.6% and 9.8% of cases, respectively). In addition, a number of cases occurred in Canada (6.0%), Japan (5.5%), China (2.1%), and Germany (2.1%). In terms of percentages, North America and Europe stand out in the number of cases (Fig. 7 ). To enable comparison, we have additionally collected the number of published documents according to country distribution, available on SCImago Journal & Country Rank [ 16 ]. The numbers correspond to the documents published from 1996 to 2019. The USA occupies the first place in the number of documents, with 21.9%, followed by China (11.1%), UK (6.3%), Germany (5.5%), and Japan (4.9%).

Field of science

The cases were classified according to the field of science. Four cases (1.7%) could not be classified due to insufficient information. Where information was available, 80.8% of cases were from the Medical and Health Sciences, 11.5% from the Natural Sciences, 4.3% from Social Sciences, 2.1% from Engineering and Technology, and 1.3% from Humanities (Fig. 8 ). Additionally, we have retrieved the number of published documents according to scientific field distribution, available on SCImago [ 16 ]. Of the total number of scientific publications, 41.5% are related to natural sciences, 22% to engineering, 25.1% to health and medical sciences, 7.8% to social sciences, 1.9% to agricultural sciences, and 1.7% to the humanities.

Field of science from the analysis of cases

This variable aimed to collect information on possible consequences and sanctions imposed by funding agencies, scientific journals and/or institutions. 97 cases could not be classified due to insufficient information. 141 cases were included. Each case could potentially include more than one outcome. Most of cases (45.4%) involved paper retraction, followed by exclusion from funding applications (35.5%). (Table 2 ).

RE and RI cases have been increasingly discussed publicly, affecting public attitudes towards scientists and raising awareness about ethical issues, violations, and their wider consequences [ 5 ]. Different approaches have been applied in order to quantify and address research misbehaviors [ 5 , 17 , 18 , 19 ]. However, most cases are investigated confidentially and the findings remain undisclosed even after the investigation [ 19 , 20 ]. Therefore, the study aimed to collect the RE and RI cases available in the scientific literature, understand how the cases are discussed, and identify the potential of case descriptions to raise awareness on RE and RI.

We collected and analyzed 500 detailed case descriptions from 388 articles and our results show that they mostly relate to extensively discussed and notorious cases. Approximately half of all included cases was mentioned in at least two different articles, and the top ten most commonly mentioned cases were discussed in 132 articles.

The prominence of certain cases in the literature, based on the number of duplicated cases we found (e.g. Hwang case), can be explained by the type of article in which cases are discussed and the type of violation involved in the case. In the article genre analysis, 33% of the cases were described in the news section of scientific publications. Our findings show that almost all article genres discuss those cases that are new and in vogue. Once the case appears in the public domain, it is intensely discussed in the media and by scientists, and some prominent cases have been discussed for more than 20 years (Table 1 ). Misconduct and retraction notices were exceptions in the article genre analysis, as they presented mostly unique cases. The misconduct notices were mainly found on the NIH repository, which is indexed in the searched databases. Some federal funding agencies like NIH usually publicize investigation findings associated with the research they fund. The results derived from the NIH repository also explains the large proportion of articles from the US (61.9%). However, in some cases, only a few details are provided about the case. For cases that have not received federal funding and have not been reported to federal authorities, the investigation is conducted by local institutions. In such instances, the reporting of findings depends on each institution’s policy and willingness to disclose information [ 21 ]. The other exception involves retraction notices. Despite the existence of ethical guidelines [ 22 ], there is no uniform and a common approach to how a journal should report a retraction. The Retraction Watch website suggests two lists of information that should be included in a retraction notice to satisfy the minimum and optimum requirements [ 22 , 23 ]. As well as disclosing the reason for the retraction and information regarding the retraction process, optimal notices should include: (I) the date when the journal was first alerted to potential problems; (II) details regarding institutional investigations and associated outcomes; (III) the effects on other papers published by the same authors; (IV) statements about more recent replications only if and when these have been validated by a third party; (V) details regarding the journal’s sanctions; and (VI) details regarding any lawsuits that have been filed regarding the case. The lack of transparency and information in retraction notices was also noted in studies that collected and evaluated retractions [ 24 ]. According to Resnik and Dinse [ 25 ], retractions notices related to cases of misconduct tend to avoid naming the specific violation involved in the case. This study found that only 32.8% of the notices identify the actual problem, such as fabrication, falsification, and plagiarism, and 58.8% reported the case as replication failure, loss of data, or error. Potential explanations for euphemisms and vague claims in retraction notices authored by editors could pertain to the possibility of legal actions from the authors, honest or self-reported errors, and lack of resources to conduct thorough investigations. In addition, the lack of transparency can also be explained by the conflicts of interests of the article’s author(s), since the notices are often written by the authors of the retracted article.

The analysis of violations/ethical issues shows the dominance of fabrication and falsification cases and explains the high prevalence of prominent cases. Non-adherence to laws and regulations (REC approval, informed consent, and data protection) was the second most prevalent issue, followed by patient safety, plagiarism, and conflicts of interest. The prevalence of the five most tagged violations in the case analysis was higher than the prevalence found in the analysis of articles that involved the same violations. The only exceptions are fabrication and falsification cases, which represented 45% of the tagged violations in the analysis of cases, and 59.1% in the article analysis. This disproportion shows a predilection for the publication of discussions related to fabrication and falsification when compared to other serious violations. Complex cases involving these types of violations make good headlines and this follows a custom pattern of writing about cases that catch the public and media’s attention [ 26 ]. The way cases of RE and RI violations are explored in the literature gives a sense that only a few scientists are “the bad apples” and they are usually discovered, investigated, and sanctioned accordingly. This implies that the integrity of science, in general, remains relatively untouched by these violations. However, studies on misconduct determinants show that scientific misconduct is a systemic problem, which involves not only individual factors, but structural and institutional factors as well, and that a combined effort is necessary to change this scenario [ 27 , 28 ].

Analysis of cases

A notable increase in RE and RI cases occurred in the 1990s, with a gradual increase until approximately 2006. This result is in agreement with studies that evaluated paper retractions [ 24 , 29 ]. Although our study did not focus only on retractions, the trend is similar. This increase in cases should not be attributed only to the increase in the number of publications, since studies that evaluated retractions show that the percentage of retraction due to fraud has increased almost ten times since 1975, compared to the total number of articles. Our results also show a gradual reduction in the number of cases from 2011 and a greater drop in 2015. However, this reduction should be considered cautiously because many investigations take years to complete and have their findings disclosed. ORI has shown that from 2001 to 2010 the investigation of their cases took an average of 20.48 months with a maximum investigation time of more than 9 years [ 24 ].

The countries from which most cases were reported were the USA (59.6%), the UK (9.8%), Canada (6.0%), Japan (5.5%), and China (2.1%). When analyzed by continent, the highest percentage of cases took place in North America, followed by Europe, Asia, Oceania, Latin America, and Africa. The predominance of cases from the USA is predictable, since the country publishes more scientific articles than any other country, with 21.8% of the total documents, according to SCImago [ 16 ]. However, the same interpretation does not apply to China, which occupies the second position in the ranking, with 11.2%. These differences in the geographical distribution were also found in a study that collected published research on research integrity [ 30 ]. The results found by Aubert Bonn and Pinxten (2019) show that studies in the United States accounted for more than half of the sample collected, and although China is one of the leaders in scientific publications, it represented only 0.7% of the sample. Our findings can also be explained by the search strategy that included only keywords in English. Since the majority of RE and RI cases are investigated and have their findings locally disclosed, the employment of English keywords and terms in the search strategy is a limitation. Moreover, our findings do not allow us to draw inferences regarding the incidence or prevalence of misconduct around the world. Instead, it shows where there is a culture of publicly disclosing information and openly discussing RE and RI cases in English documents.

Scientific field analysis

The results show that 80.8% of reported cases occurred in the medical and health sciences whilst only 1.3% occurred in the humanities. This disciplinary difference has also been observed in studies on research integrity climates. A study conducted by Haven and colleagues, [ 28 ] associated seven subscales of research climate with the disciplinary field. The subscales included: (1) Responsible Conduct of Research (RCR) resources, (2) regulatory quality, (3) integrity norms, (4) integrity socialization, (5) supervisor/supervisee relations, (6) (lack of) integrity inhibitors, and (7) expectations. The results, based on the seven subscale scores, show that researchers from the humanities and social sciences have the lowest perception of the RI climate. By contrast, the natural sciences expressed the highest perception of the RI climate, followed by the biomedical sciences. There are also significant differences in the depth and extent of the regulatory environments of different disciplines (e.g. the existence of laws, codes of conduct, policies, relevant ethics committees, or authorities). These findings corroborate our results, as those areas of science most familiar with RI tend to explore the subject further, and, consequently, are more likely to publish case details. Although the volume of published research in each research area also influences the number of cases, the predominance of medical and health sciences cases is not aligned with the trends regarding the volume of published research. According to SCImago Journal & Country Rank [ 16 ], natural sciences occupy the first place in the number of publications (41,5%), followed by the medical and health sciences (25,1%), engineering (22%), social sciences (7,8%), and the humanities (1,7%). Moreover, biomedical journals are overrepresented in the top scientific journals by IF ranking, and these journals usually have clear policies for research misconduct. High-impact journals are more likely to have higher visibility and scrutiny, and consequently, more likely to have been the subject of misconduct investigations. Additionally, the most well-known general medical journals, including NEJM, The Lancet, and the BMJ, employ journalists to write their news sections. Since these journals have the resources to produce extensive news sections, it is, therefore, more likely that medical cases will be discussed.

Violations analysis

In the analysis of violations, the cases were categorized into major and minor misbehaviors. Most cases involved data fabrication and falsification, followed by cases involving non-adherence to laws and regulations, patient safety, plagiarism, and conflicts of interest. When classified by categories, 12.5% of the tagged violations involved issues in the study design, 16.4% in data collection, 56.0% in reporting, and 15.1% involved collaboration issues. Approximately 80% of the tagged violations involved serious research misbehaviors, based on the ranking of research misbehaviors proposed by Bouter and colleagues. However, as demonstrated in a meta-analysis by Fanelli (2009), most self-declared cases involve questionable research practices. In the meta-analysis, 33.7% of scientists admitted questionable research practices, and 72% admitted when asked about the behavior of colleagues. This finding contrasts with an admission rate of 1.97% and 14.12% for cases involving fabrication, falsification, and plagiarism. However, Fanelli’s meta-analysis does not include data about research misbehaviors in its wider sense but focuses on behaviors that bias research results (i.e. fabrication and falsification, intentional non-publication of results, biased methodology, misleading reporting). In our study, the majority of cases involved FFP (66.4%). Overrepresentation of some types of violations, and underrepresentation of others, might lead to misguided efforts, as cases that receive intense publicity eventually influence policies relating to scientific misconduct and RI [ 20 ].

Sanctions analysis

The five most prevalent outcomes were paper retraction, followed by exclusion from funding applications, exclusion from service or position, dismissal and suspension, and paper correction. This result is similar to that found by Redman and Merz [ 31 ], who collected data from misconduct cases provided by the ORI. Moreover, their results show that fabrication and falsification cases are 8.8 times more likely than others to receive funding exclusions. Such cases also received, on average, 0.6 more sanctions per case. Punishments for misconduct remain under discussion, ranging from the criminalization of more serious forms of misconduct [ 32 ] to social punishments, such as those recently introduced by China [ 33 ]. The most common sanction identified by our analysis—paper retraction—is consistent with the most prevalent types of violation, that is, falsification and fabrication.

Publicizing scientific misconduct

The lack of publicly available summaries of misconduct investigations makes it difficult to share experiences and evaluate the effectiveness of policies and training programs. Publicizing scientific misconduct can have serious consequences and creates a stigma around those involved in the case. For instance, publicized allegations can damage the reputation of the accused even when they are later exonerated [ 21 ]. Thus, for published cases, it is the responsibility of the authors and editors to determine whether the name(s) of those involved should be disclosed. On the one hand, it is envisaged that disclosing the name(s) of those involved will encourage others in the community to foster good standards. On the other hand, it is suggested that someone who has made a mistake should have the right to a chance to defend his/her reputation. Regardless of whether a person's name is left out or disclosed, case reports have an important educational function and can help guide RE- and RI-related policies [ 34 ]. A recent paper published by Gunsalus [ 35 ] proposes a three-part approach to strengthen transparency in misconduct investigations. The first part consists of a checklist [ 36 ]. The second suggests that an external peer reviewer should be involved in investigative reporting. The third part calls for the publication of the peer reviewer’s findings.

Limitations

One of the possible limitations of our study may be our search strategy. Although we have conducted pilot searches and sensitivity tests to reach the most feasible and precise search strategy, we cannot exclude the possibility of having missed important cases. Furthermore, the use of English keywords was another limitation of our search. Since most investigations are performed locally and published in local repositories, our search only allowed us to access cases from English-speaking countries or discussed in academic publications written in English. Additionally, it is important to note that the published cases are not representative of all instances of misconduct, since most of them are never discovered, and when discovered, not all are fully investigated or have their findings published. It is also important to note that the lack of information from the extracted case descriptions is a limitation that affects the interpretation of our results. In our review, only 25 retraction notices contained sufficient information that allowed us to include them in our analysis in conformance with the inclusion criteria. Although our search strategy was not focused specifically on retraction and misconduct notices, we believe that if sufficiently detailed information was available in such notices, the search strategy would have identified them.

Case descriptions found in academic journals are dominated by discussions regarding prominent cases and are mainly published in the news section of journals. Our results show that there is an overrepresentation of biomedical research cases over other scientific fields when compared with the volume of publications produced by each field. Moreover, published cases mostly involve fabrication, falsification, and patient safety issues. This finding could have a significant impact on the academic representation of ethical issues for RE and RI. The predominance of fabrication and falsification cases might diverge the attention of the academic community from relevant but less visible violations and ethical issues, and recently emerging forms of misbehaviors.

Availability of data and materials

This review has been developed by members of the EnTIRE project in order to generate information on the cases that will be made available on the Embassy of Good Science platform ( www.embassy.science ). The dataset supporting the conclusions of this article is available in the Open Science Framework (OSF) repository in https://osf.io/3xatj/?view_only=313a0477ab554b7489ee52d3046398b9 .

National Academies of Sciences E, Medicine. Fostering integrity in research. National Academies Press; 2017.

Davis MS, Riske-Morris M, Diaz SR. Causal factors implicated in research misconduct: evidence from ORI case files. Sci Eng Ethics. 2007;13(4):395–414. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11948-007-9045-2 .

Article Google Scholar

Ampollini I, Bucchi M. When public discourse mirrors academic debate: research integrity in the media. Sci Eng Ethics. 2020;26(1):451–74. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11948-019-00103-5 .

Hesselmann F, Graf V, Schmidt M, Reinhart M. The visibility of scientific misconduct: a review of the literature on retracted journal articles. Curr Sociol La Sociologie contemporaine. 2017;65(6):814–45. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011392116663807 .

Martinson BC, Anderson MS, de Vries R. Scientists behaving badly. Nature. 2005;435(7043):737–8. https://doi.org/10.1038/435737a .

Loikith L, Bauchwitz R. The essential need for research misconduct allegation audits. Sci Eng Ethics. 2016;22(4):1027–49. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11948-016-9798-6 .

OECD. Revised field of science and technology (FoS) classification in the Frascati manual. Working Party of National Experts on Science and Technology Indicators 2007. p. 1–12.

Bouter LM, Tijdink J, Axelsen N, Martinson BC, ter Riet G. Ranking major and minor research misbehaviors: results from a survey among participants of four World Conferences on Research Integrity. Res Integrity Peer Rev. 2016;1(1):17. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41073-016-0024-5 .

Greenberg DS. Resounding echoes of Gallo case. Lancet. 1995;345(8950):639.

Dresser R. Giving scientists their due. The Imanishi-Kari decision. Hastings Center Rep. 1997;27(3):26–8.

Hong ST. We should not forget lessons learned from the Woo Suk Hwang’s case of research misconduct and bioethics law violation. J Korean Med Sci. 2016;31(11):1671–2. https://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2016.31.11.1671 .

Opel DJ, Diekema DS, Marcuse EK. Assuring research integrity in the wake of Wakefield. BMJ (Clinical research ed). 2011;342(7790):179. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.d2 .

Wells F. The Stoke CNEP Saga: did it need to take so long? J R Soc Med. 2010;103(9):352–6. https://doi.org/10.1258/jrsm.2010.10k010 .

Normile D. RIKEN panel finds misconduct in controversial paper. Science. 2014;344(6179):23. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.344.6179.23 .

Wager E. The Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE): Objectives and achievements 1997–2012. La Presse Médicale. 2012;41(9):861–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lpm.2012.02.049 .

SCImago nd. SJR — SCImago Journal & Country Rank [Portal]. http://www.scimagojr.com . Accessed 03 Feb 2021.

Fanelli D. How many scientists fabricate and falsify research? A systematic review and meta-analysis of survey data. PLoS ONE. 2009;4(5):e5738. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0005738 .

Steneck NH. Fostering integrity in research: definitions, current knowledge, and future directions. Sci Eng Ethics. 2006;12(1):53–74. https://doi.org/10.1007/PL00022268 .

DuBois JM, Anderson EE, Chibnall J, Carroll K, Gibb T, Ogbuka C, et al. Understanding research misconduct: a comparative analysis of 120 cases of professional wrongdoing. Account Res. 2013;20(5–6):320–38. https://doi.org/10.1080/08989621.2013.822248 .

National Academy of Sciences NAoE, Institute of Medicine Panel on Scientific R, the Conduct of R. Responsible Science: Ensuring the Integrity of the Research Process: Volume I. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US) Copyright (c) 1992 by the National Academy of Sciences; 1992.

Bauchner H, Fontanarosa PB, Flanagin A, Thornton J. Scientific misconduct and medical journals. JAMA. 2018;320(19):1985–7. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2018.14350 .

COPE Council. COPE Guidelines: Retraction Guidelines. 2019. https://doi.org/10.24318/cope.2019.1.4 .

Retraction Watch. What should an ideal retraction notice look like? 2015, May 21. https://retractionwatch.com/2015/05/21/what-should-an-ideal-retraction-notice-look-like/ .

Fang FC, Steen RG, Casadevall A. Misconduct accounts for the majority of retracted scientific publications. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109(42):17028–33. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1212247109 .

Resnik DB, Dinse GE. Scientific retractions and corrections related to misconduct findings. J Med Ethics. 2013;39(1):46–50. https://doi.org/10.1136/medethics-2012-100766 .

de Vries R, Anderson MS, Martinson BC. Normal misbehavior: scientists talk about the ethics of research. J Empir Res Hum Res Ethics JERHRE. 2006;1(1):43–50. https://doi.org/10.1525/jer.2006.1.1.43 .

Sovacool BK. Exploring scientific misconduct: isolated individuals, impure institutions, or an inevitable idiom of modern science? J Bioethical Inquiry. 2008;5(4):271. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11673-008-9113-6 .

Haven TL, Tijdink JK, Martinson BC, Bouter LM. Perceptions of research integrity climate differ between academic ranks and disciplinary fields: results from a survey among academic researchers in Amsterdam. PLoS ONE. 2019;14(1):e0210599. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0210599 .

Trikalinos NA, Evangelou E, Ioannidis JPA. Falsified papers in high-impact journals were slow to retract and indistinguishable from nonfraudulent papers. J Clin Epidemiol. 2008;61(5):464–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2007.11.019 .

Aubert Bonn N, Pinxten W. A decade of empirical research on research integrity: What have we (not) looked at? J Empir Res Hum Res Ethics. 2019;14(4):338–52. https://doi.org/10.1177/1556264619858534 .

Redman BK, Merz JF. Scientific misconduct: do the punishments fit the crime? Science. 2008;321(5890):775. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1158052 .

Bülow W, Helgesson G. Criminalization of scientific misconduct. Med Health Care Philos. 2019;22(2):245–52. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11019-018-9865-7 .

Cyranoski D. China introduces “social” punishments for scientific misconduct. Nature. 2018;564(7736):312. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-018-07740-z .