- USC Libraries

- Research Guides

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper

- 3. The Abstract

- Purpose of Guide

- Design Flaws to Avoid

- Independent and Dependent Variables

- Glossary of Research Terms

- Reading Research Effectively

- Narrowing a Topic Idea

- Broadening a Topic Idea

- Extending the Timeliness of a Topic Idea

- Academic Writing Style

- Applying Critical Thinking

- Choosing a Title

- Making an Outline

- Paragraph Development

- Research Process Video Series

- Executive Summary

- The C.A.R.S. Model

- Background Information

- The Research Problem/Question

- Theoretical Framework

- Citation Tracking

- Content Alert Services

- Evaluating Sources

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

- Tiertiary Sources

- Scholarly vs. Popular Publications

- Qualitative Methods

- Quantitative Methods

- Insiderness

- Using Non-Textual Elements

- Limitations of the Study

- Common Grammar Mistakes

- Writing Concisely

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Footnotes or Endnotes?

- Further Readings

- Generative AI and Writing

- USC Libraries Tutorials and Other Guides

- Bibliography

An abstract summarizes, usually in one paragraph of 300 words or less, the major aspects of the entire paper in a prescribed sequence that includes: 1) the overall purpose of the study and the research problem(s) you investigated; 2) the basic design of the study; 3) major findings or trends found as a result of your analysis; and, 4) a brief summary of your interpretations and conclusions.

Writing an Abstract. The Writing Center. Clarion University, 2009; Writing an Abstract for Your Research Paper. The Writing Center, University of Wisconsin, Madison; Koltay, Tibor. Abstracts and Abstracting: A Genre and Set of Skills for the Twenty-first Century . Oxford, UK: Chandos Publishing, 2010;

Importance of a Good Abstract

Sometimes your professor will ask you to include an abstract, or general summary of your work, with your research paper. The abstract allows you to elaborate upon each major aspect of the paper and helps readers decide whether they want to read the rest of the paper. Therefore, enough key information [e.g., summary results, observations, trends, etc.] must be included to make the abstract useful to someone who may want to examine your work.

How do you know when you have enough information in your abstract? A simple rule-of-thumb is to imagine that you are another researcher doing a similar study. Then ask yourself: if your abstract was the only part of the paper you could access, would you be happy with the amount of information presented there? Does it tell the whole story about your study? If the answer is "no" then the abstract likely needs to be revised.

Farkas, David K. “A Scheme for Understanding and Writing Summaries.” Technical Communication 67 (August 2020): 45-60; How to Write a Research Abstract. Office of Undergraduate Research. University of Kentucky; Staiger, David L. “What Today’s Students Need to Know about Writing Abstracts.” International Journal of Business Communication January 3 (1966): 29-33; Swales, John M. and Christine B. Feak. Abstracts and the Writing of Abstracts . Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 2009.

Structure and Writing Style

I. Types of Abstracts

To begin, you need to determine which type of abstract you should include with your paper. There are four general types.

Critical Abstract A critical abstract provides, in addition to describing main findings and information, a judgment or comment about the study’s validity, reliability, or completeness. The researcher evaluates the paper and often compares it with other works on the same subject. Critical abstracts are generally 400-500 words in length due to the additional interpretive commentary. These types of abstracts are used infrequently.

Descriptive Abstract A descriptive abstract indicates the type of information found in the work. It makes no judgments about the work, nor does it provide results or conclusions of the research. It does incorporate key words found in the text and may include the purpose, methods, and scope of the research. Essentially, the descriptive abstract only describes the work being summarized. Some researchers consider it an outline of the work, rather than a summary. Descriptive abstracts are usually very short, 100 words or less. Informative Abstract The majority of abstracts are informative. While they still do not critique or evaluate a work, they do more than describe it. A good informative abstract acts as a surrogate for the work itself. That is, the researcher presents and explains all the main arguments and the important results and evidence in the paper. An informative abstract includes the information that can be found in a descriptive abstract [purpose, methods, scope] but it also includes the results and conclusions of the research and the recommendations of the author. The length varies according to discipline, but an informative abstract is usually no more than 300 words in length.

Highlight Abstract A highlight abstract is specifically written to attract the reader’s attention to the study. No pretense is made of there being either a balanced or complete picture of the paper and, in fact, incomplete and leading remarks may be used to spark the reader’s interest. In that a highlight abstract cannot stand independent of its associated article, it is not a true abstract and, therefore, rarely used in academic writing.

II. Writing Style

Use the active voice when possible , but note that much of your abstract may require passive sentence constructions. Regardless, write your abstract using concise, but complete, sentences. Get to the point quickly and always use the past tense because you are reporting on a study that has been completed.

Abstracts should be formatted as a single paragraph in a block format and with no paragraph indentations. In most cases, the abstract page immediately follows the title page. Do not number the page. Rules set forth in writing manual vary but, in general, you should center the word "Abstract" at the top of the page with double spacing between the heading and the abstract. The final sentences of an abstract concisely summarize your study’s conclusions, implications, or applications to practice and, if appropriate, can be followed by a statement about the need for additional research revealed from the findings.

Composing Your Abstract

Although it is the first section of your paper, the abstract should be written last since it will summarize the contents of your entire paper. A good strategy to begin composing your abstract is to take whole sentences or key phrases from each section of the paper and put them in a sequence that summarizes the contents. Then revise or add connecting phrases or words to make the narrative flow clearly and smoothly. Note that statistical findings should be reported parenthetically [i.e., written in parentheses].

Before handing in your final paper, check to make sure that the information in the abstract completely agrees with what you have written in the paper. Think of the abstract as a sequential set of complete sentences describing the most crucial information using the fewest necessary words. The abstract SHOULD NOT contain:

- A catchy introductory phrase, provocative quote, or other device to grab the reader's attention,

- Lengthy background or contextual information,

- Redundant phrases, unnecessary adverbs and adjectives, and repetitive information;

- Acronyms or abbreviations,

- References to other literature [say something like, "current research shows that..." or "studies have indicated..."],

- Using ellipticals [i.e., ending with "..."] or incomplete sentences,

- Jargon or terms that may be confusing to the reader,

- Citations to other works, and

- Any sort of image, illustration, figure, or table, or references to them.

Abstract. Writing Center. University of Kansas; Abstract. The Structure, Format, Content, and Style of a Journal-Style Scientific Paper. Department of Biology. Bates College; Abstracts. The Writing Center. University of North Carolina; Borko, Harold and Seymour Chatman. "Criteria for Acceptable Abstracts: A Survey of Abstracters' Instructions." American Documentation 14 (April 1963): 149-160; Abstracts. The Writer’s Handbook. Writing Center. University of Wisconsin, Madison; Hartley, James and Lucy Betts. "Common Weaknesses in Traditional Abstracts in the Social Sciences." Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology 60 (October 2009): 2010-2018; Koltay, Tibor. Abstracts and Abstracting: A Genre and Set of Skills for the Twenty-first Century. Oxford, UK: Chandos Publishing, 2010; Procter, Margaret. The Abstract. University College Writing Centre. University of Toronto; Riordan, Laura. “Mastering the Art of Abstracts.” The Journal of the American Osteopathic Association 115 (January 2015 ): 41-47; Writing Report Abstracts. The Writing Lab and The OWL. Purdue University; Writing Abstracts. Writing Tutorial Services, Center for Innovative Teaching and Learning. Indiana University; Koltay, Tibor. Abstracts and Abstracting: A Genre and Set of Skills for the Twenty-First Century . Oxford, UK: 2010; Writing an Abstract for Your Research Paper. The Writing Center, University of Wisconsin, Madison.

Writing Tip

Never Cite Just the Abstract!

Citing to just a journal article's abstract does not confirm for the reader that you have conducted a thorough or reliable review of the literature. If the full-text is not available, go to the USC Libraries main page and enter the title of the article [NOT the title of the journal]. If the Libraries have a subscription to the journal, the article should appear with a link to the full-text or to the journal publisher page where you can get the article. If the article does not appear, try searching Google Scholar using the link on the USC Libraries main page. If you still can't find the article after doing this, contact a librarian or you can request it from our free i nterlibrary loan and document delivery service .

- << Previous: Research Process Video Series

- Next: Executive Summary >>

- Last Updated: Apr 24, 2024 10:51 AM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide

Writing an Abstract for Your Research Paper

Definition and Purpose of Abstracts

An abstract is a short summary of your (published or unpublished) research paper, usually about a paragraph (c. 6-7 sentences, 150-250 words) long. A well-written abstract serves multiple purposes:

- an abstract lets readers get the gist or essence of your paper or article quickly, in order to decide whether to read the full paper;

- an abstract prepares readers to follow the detailed information, analyses, and arguments in your full paper;

- and, later, an abstract helps readers remember key points from your paper.

It’s also worth remembering that search engines and bibliographic databases use abstracts, as well as the title, to identify key terms for indexing your published paper. So what you include in your abstract and in your title are crucial for helping other researchers find your paper or article.

If you are writing an abstract for a course paper, your professor may give you specific guidelines for what to include and how to organize your abstract. Similarly, academic journals often have specific requirements for abstracts. So in addition to following the advice on this page, you should be sure to look for and follow any guidelines from the course or journal you’re writing for.

The Contents of an Abstract

Abstracts contain most of the following kinds of information in brief form. The body of your paper will, of course, develop and explain these ideas much more fully. As you will see in the samples below, the proportion of your abstract that you devote to each kind of information—and the sequence of that information—will vary, depending on the nature and genre of the paper that you are summarizing in your abstract. And in some cases, some of this information is implied, rather than stated explicitly. The Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association , which is widely used in the social sciences, gives specific guidelines for what to include in the abstract for different kinds of papers—for empirical studies, literature reviews or meta-analyses, theoretical papers, methodological papers, and case studies.

Here are the typical kinds of information found in most abstracts:

- the context or background information for your research; the general topic under study; the specific topic of your research

- the central questions or statement of the problem your research addresses

- what’s already known about this question, what previous research has done or shown

- the main reason(s) , the exigency, the rationale , the goals for your research—Why is it important to address these questions? Are you, for example, examining a new topic? Why is that topic worth examining? Are you filling a gap in previous research? Applying new methods to take a fresh look at existing ideas or data? Resolving a dispute within the literature in your field? . . .

- your research and/or analytical methods

- your main findings , results , or arguments

- the significance or implications of your findings or arguments.

Your abstract should be intelligible on its own, without a reader’s having to read your entire paper. And in an abstract, you usually do not cite references—most of your abstract will describe what you have studied in your research and what you have found and what you argue in your paper. In the body of your paper, you will cite the specific literature that informs your research.

When to Write Your Abstract

Although you might be tempted to write your abstract first because it will appear as the very first part of your paper, it’s a good idea to wait to write your abstract until after you’ve drafted your full paper, so that you know what you’re summarizing.

What follows are some sample abstracts in published papers or articles, all written by faculty at UW-Madison who come from a variety of disciplines. We have annotated these samples to help you see the work that these authors are doing within their abstracts.

Choosing Verb Tenses within Your Abstract

The social science sample (Sample 1) below uses the present tense to describe general facts and interpretations that have been and are currently true, including the prevailing explanation for the social phenomenon under study. That abstract also uses the present tense to describe the methods, the findings, the arguments, and the implications of the findings from their new research study. The authors use the past tense to describe previous research.

The humanities sample (Sample 2) below uses the past tense to describe completed events in the past (the texts created in the pulp fiction industry in the 1970s and 80s) and uses the present tense to describe what is happening in those texts, to explain the significance or meaning of those texts, and to describe the arguments presented in the article.

The science samples (Samples 3 and 4) below use the past tense to describe what previous research studies have done and the research the authors have conducted, the methods they have followed, and what they have found. In their rationale or justification for their research (what remains to be done), they use the present tense. They also use the present tense to introduce their study (in Sample 3, “Here we report . . .”) and to explain the significance of their study (In Sample 3, This reprogramming . . . “provides a scalable cell source for. . .”).

Sample Abstract 1

From the social sciences.

Reporting new findings about the reasons for increasing economic homogamy among spouses

Gonalons-Pons, Pilar, and Christine R. Schwartz. “Trends in Economic Homogamy: Changes in Assortative Mating or the Division of Labor in Marriage?” Demography , vol. 54, no. 3, 2017, pp. 985-1005.

![fill in the blank. a research abstract should range from “The growing economic resemblance of spouses has contributed to rising inequality by increasing the number of couples in which there are two high- or two low-earning partners. [Annotation for the previous sentence: The first sentence introduces the topic under study (the “economic resemblance of spouses”). This sentence also implies the question underlying this research study: what are the various causes—and the interrelationships among them—for this trend?] The dominant explanation for this trend is increased assortative mating. Previous research has primarily relied on cross-sectional data and thus has been unable to disentangle changes in assortative mating from changes in the division of spouses’ paid labor—a potentially key mechanism given the dramatic rise in wives’ labor supply. [Annotation for the previous two sentences: These next two sentences explain what previous research has demonstrated. By pointing out the limitations in the methods that were used in previous studies, they also provide a rationale for new research.] We use data from the Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID) to decompose the increase in the correlation between spouses’ earnings and its contribution to inequality between 1970 and 2013 into parts due to (a) changes in assortative mating, and (b) changes in the division of paid labor. [Annotation for the previous sentence: The data, research and analytical methods used in this new study.] Contrary to what has often been assumed, the rise of economic homogamy and its contribution to inequality is largely attributable to changes in the division of paid labor rather than changes in sorting on earnings or earnings potential. Our findings indicate that the rise of economic homogamy cannot be explained by hypotheses centered on meeting and matching opportunities, and they show where in this process inequality is generated and where it is not.” (p. 985) [Annotation for the previous two sentences: The major findings from and implications and significance of this study.]](https://writing.wisc.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/535/2019/08/Abstract-1.png)

Sample Abstract 2

From the humanities.

Analyzing underground pulp fiction publications in Tanzania, this article makes an argument about the cultural significance of those publications

Emily Callaci. “Street Textuality: Socialism, Masculinity, and Urban Belonging in Tanzania’s Pulp Fiction Publishing Industry, 1975-1985.” Comparative Studies in Society and History , vol. 59, no. 1, 2017, pp. 183-210.

![fill in the blank. a research abstract should range from “From the mid-1970s through the mid-1980s, a network of young urban migrant men created an underground pulp fiction publishing industry in the city of Dar es Salaam. [Annotation for the previous sentence: The first sentence introduces the context for this research and announces the topic under study.] As texts that were produced in the underground economy of a city whose trajectory was increasingly charted outside of formalized planning and investment, these novellas reveal more than their narrative content alone. These texts were active components in the urban social worlds of the young men who produced them. They reveal a mode of urbanism otherwise obscured by narratives of decolonization, in which urban belonging was constituted less by national citizenship than by the construction of social networks, economic connections, and the crafting of reputations. This article argues that pulp fiction novellas of socialist era Dar es Salaam are artifacts of emergent forms of male sociability and mobility. In printing fictional stories about urban life on pilfered paper and ink, and distributing their texts through informal channels, these writers not only described urban communities, reputations, and networks, but also actually created them.” (p. 210) [Annotation for the previous sentences: The remaining sentences in this abstract interweave other essential information for an abstract for this article. The implied research questions: What do these texts mean? What is their historical and cultural significance, produced at this time, in this location, by these authors? The argument and the significance of this analysis in microcosm: these texts “reveal a mode or urbanism otherwise obscured . . .”; and “This article argues that pulp fiction novellas. . . .” This section also implies what previous historical research has obscured. And through the details in its argumentative claims, this section of the abstract implies the kinds of methods the author has used to interpret the novellas and the concepts under study (e.g., male sociability and mobility, urban communities, reputations, network. . . ).]](https://writing.wisc.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/535/2019/08/Abstract-2.png)

Sample Abstract/Summary 3

From the sciences.

Reporting a new method for reprogramming adult mouse fibroblasts into induced cardiac progenitor cells

Lalit, Pratik A., Max R. Salick, Daryl O. Nelson, Jayne M. Squirrell, Christina M. Shafer, Neel G. Patel, Imaan Saeed, Eric G. Schmuck, Yogananda S. Markandeya, Rachel Wong, Martin R. Lea, Kevin W. Eliceiri, Timothy A. Hacker, Wendy C. Crone, Michael Kyba, Daniel J. Garry, Ron Stewart, James A. Thomson, Karen M. Downs, Gary E. Lyons, and Timothy J. Kamp. “Lineage Reprogramming of Fibroblasts into Proliferative Induced Cardiac Progenitor Cells by Defined Factors.” Cell Stem Cell , vol. 18, 2016, pp. 354-367.

![fill in the blank. a research abstract should range from “Several studies have reported reprogramming of fibroblasts into induced cardiomyocytes; however, reprogramming into proliferative induced cardiac progenitor cells (iCPCs) remains to be accomplished. [Annotation for the previous sentence: The first sentence announces the topic under study, summarizes what’s already known or been accomplished in previous research, and signals the rationale and goals are for the new research and the problem that the new research solves: How can researchers reprogram fibroblasts into iCPCs?] Here we report that a combination of 11 or 5 cardiac factors along with canonical Wnt and JAK/STAT signaling reprogrammed adult mouse cardiac, lung, and tail tip fibroblasts into iCPCs. The iCPCs were cardiac mesoderm-restricted progenitors that could be expanded extensively while maintaining multipo-tency to differentiate into cardiomyocytes, smooth muscle cells, and endothelial cells in vitro. Moreover, iCPCs injected into the cardiac crescent of mouse embryos differentiated into cardiomyocytes. iCPCs transplanted into the post-myocardial infarction mouse heart improved survival and differentiated into cardiomyocytes, smooth muscle cells, and endothelial cells. [Annotation for the previous four sentences: The methods the researchers developed to achieve their goal and a description of the results.] Lineage reprogramming of adult somatic cells into iCPCs provides a scalable cell source for drug discovery, disease modeling, and cardiac regenerative therapy.” (p. 354) [Annotation for the previous sentence: The significance or implications—for drug discovery, disease modeling, and therapy—of this reprogramming of adult somatic cells into iCPCs.]](https://writing.wisc.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/535/2019/08/Abstract-3.png)

Sample Abstract 4, a Structured Abstract

Reporting results about the effectiveness of antibiotic therapy in managing acute bacterial sinusitis, from a rigorously controlled study

Note: This journal requires authors to organize their abstract into four specific sections, with strict word limits. Because the headings for this structured abstract are self-explanatory, we have chosen not to add annotations to this sample abstract.

Wald, Ellen R., David Nash, and Jens Eickhoff. “Effectiveness of Amoxicillin/Clavulanate Potassium in the Treatment of Acute Bacterial Sinusitis in Children.” Pediatrics , vol. 124, no. 1, 2009, pp. 9-15.

“OBJECTIVE: The role of antibiotic therapy in managing acute bacterial sinusitis (ABS) in children is controversial. The purpose of this study was to determine the effectiveness of high-dose amoxicillin/potassium clavulanate in the treatment of children diagnosed with ABS.

METHODS : This was a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Children 1 to 10 years of age with a clinical presentation compatible with ABS were eligible for participation. Patients were stratified according to age (<6 or ≥6 years) and clinical severity and randomly assigned to receive either amoxicillin (90 mg/kg) with potassium clavulanate (6.4 mg/kg) or placebo. A symptom survey was performed on days 0, 1, 2, 3, 5, 7, 10, 20, and 30. Patients were examined on day 14. Children’s conditions were rated as cured, improved, or failed according to scoring rules.

RESULTS: Two thousand one hundred thirty-five children with respiratory complaints were screened for enrollment; 139 (6.5%) had ABS. Fifty-eight patients were enrolled, and 56 were randomly assigned. The mean age was 6630 months. Fifty (89%) patients presented with persistent symptoms, and 6 (11%) presented with nonpersistent symptoms. In 24 (43%) children, the illness was classified as mild, whereas in the remaining 32 (57%) children it was severe. Of the 28 children who received the antibiotic, 14 (50%) were cured, 4 (14%) were improved, 4(14%) experienced treatment failure, and 6 (21%) withdrew. Of the 28children who received placebo, 4 (14%) were cured, 5 (18%) improved, and 19 (68%) experienced treatment failure. Children receiving the antibiotic were more likely to be cured (50% vs 14%) and less likely to have treatment failure (14% vs 68%) than children receiving the placebo.

CONCLUSIONS : ABS is a common complication of viral upper respiratory infections. Amoxicillin/potassium clavulanate results in significantly more cures and fewer failures than placebo, according to parental report of time to resolution.” (9)

Some Excellent Advice about Writing Abstracts for Basic Science Research Papers, by Professor Adriano Aguzzi from the Institute of Neuropathology at the University of Zurich:

Academic and Professional Writing

This is an accordion element with a series of buttons that open and close related content panels.

Analysis Papers

Reading Poetry

A Short Guide to Close Reading for Literary Analysis

Using Literary Quotations

Play Reviews

Writing a Rhetorical Précis to Analyze Nonfiction Texts

Incorporating Interview Data

Grant Proposals

Planning and Writing a Grant Proposal: The Basics

Additional Resources for Grants and Proposal Writing

Job Materials and Application Essays

Writing Personal Statements for Ph.D. Programs

- Before you begin: useful tips for writing your essay

- Guided brainstorming exercises

- Get more help with your essay

- Frequently Asked Questions

Resume Writing Tips

CV Writing Tips

Cover Letters

Business Letters

Proposals and Dissertations

Resources for Proposal Writers

Resources for Dissertators

Research Papers

Planning and Writing Research Papers

Quoting and Paraphrasing

Writing Annotated Bibliographies

Creating Poster Presentations

Thank-You Notes

Advice for Students Writing Thank-You Notes to Donors

Reading for a Review

Critical Reviews

Writing a Review of Literature

Scientific Reports

Scientific Report Format

Sample Lab Assignment

Writing for the Web

Writing an Effective Blog Post

Writing for Social Media: A Guide for Academics

Module 8: APA Citations

Apa abstract page.

The abstract acts as the second major section of the document and typically begins on the second page of the paper. It follows directly after the title page and precedes the main body of the paper.

The abstract is a succinct, single-paragraph summary of your paper’s purpose, main points, method, findings, and conclusions, and is often recommended to be written after the rest of your paper has been completed.

General Format

How should the abstract page be formatted.

The abstract’s length should be a minimum of 150 words and a maximum of 250 words; it should be confined within a single paragraph. Unlike in other paragraphs in the paper, the first line of the abstract should not be indented five spaces from the left margin.

Like the rest of the paper, the pages of the abstract should be double-spaced and typed in Times New Roman, 12 pt. The margins are set at 1” on all sides. While the running head is flush with the upper left-hand corner of every page, the page number is flush with the upper right-hand corner of every page. Note that all letters of the running head should be capitalized and should not exceed 50 characters, including punctuation, letters, and spaces.

The title of the abstract is centered at the top of the page; there is no extra space between the title and the paragraph. Avoid formatting the title with bold, italics, underlining, or quotation marks, or mislabeling the abstract with the title of the research paper.

When writing the abstract, note that the APA recommends using two spaces after sentences that end in a period; however, sentences that end in other punctuation marks may be followed by a single space. Additionally, the APA recommends using the active voice and past tense in the abstract, but the present tense may be used to describe conclusions and implications. Acronyms or abbreviated words should be defined in the abstract.

How should the list of keywords be formatted?

According to your professor’s directives, you may be required to include a short list of keywords to enable researchers and databases to locate your paper more effectively. The list of keywords should follow after the abstract paragraph, and the word Keywords should be italicized, indented five spaces from the left margin, and followed by a colon. There is no period at the end of the list of keywords.

- Formatting the Abstract Page (APA). Authored by : Jennifer Janechek. Provided by : Writing Commons. Located at : http://writingcommons.org/open-text/writing-processes/format/apa-format/1100-formatting-the-abstract-page-apa-sp-770492217 . License : CC BY-NC-ND: Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives

Privacy Policy

- Ask a Librarian

Abstracts - A Guide to Writing

What is an abstract.

Abstracts act as concise surrogates or representations of research projects. Abstracts precede papers in research journals and appear in programs of scholarly conferences. They should be brief, concise, and use clear language. A researcher reading an abstract should have a clear idea of what the research project is about after reading an abstract.

Abstracts allow readers to grasp the purpose and major ideas of a paper, poster, or presentation. A great abstract will be packed with information on the research project and will let other researchers know whether reading the entire paper or attending a presentation is worthwhile.

Why write an abstract?

Abstracts often serve as the advertisement of a research project. They allow readers to quickly scan a small amount of text and to make a decision as to whether the work will satisfy their information needs. If a researcher is interested, he or she will continue on to read the entire document or attend the session.

Many online databases use abstracts to index larger research projects. Using keywords from your research project in your abstract will ensure your project is easily searched.

Types of abstracts

Different academic disciplines have different research methods and requirements. For example, social sciences or hard science abstracts will typically include the parts of a research experiment; whereas abstracts in the humanities will often discuss the hypothesis being investigated and the conclusion. Conferences and journals may have specific requirements for abstract submissions, so be sure to review the requirements prior to writing an abstract for your project.

Informative abstracts

Informative abstracts are generally used for documents pertaining to experimental investigations, inquiries, or surveys. The original document is condensed reflecting its form and content and provides quantitative and qualitative information.

Informative Example

Daidzic, N. E. (2015). Efficient general computational method for estimation of standard atmosphere parameters. International Journal of Aviation, Aeronautics, and Aerospace, 2 (1). https://doi.org/10.15394/ijaaa.2015.1053

Knowledge of standard air temperature, pressure, density, speed of sound, and viscosity as a function of altitude is essential information in aircraft design, performance testing, pressure altimeter calibration, and several other aeronautical engineering and aviation science applications. A new efficient computational method for rapid calculations of standard atmospheric parameters up to 86 orthometric km is presented. Additionally, mass and weight of each standard atmospheric layer were calculated using a numerical integration method. The sum of all fractional masses and weights represents the total mass and weight of Earth’s atmosphere. The results obtained here agree well with measurements and models of the real atmosphere. Various ISA scale heights were estimated from numerical integration of atmospheric masses and weights. The nature of the geopotential and the orthometric heights and the definition of MSL have been explained. Essential thermodynamic considerations of still and dry air were highlighted. In addition to general working equations for air pressure and density vertical distribution for each atmospheric layer an extensive table of calculated values up to 86 km has been provided in appendix. Several models of air viscosity were also compared. It was found that simple Granger’s model agrees well with the widely accepted Sutherland-type viscosity equation. All computations were performed with the fourteen significant-digits accuracy although only seven significant digits were typically presented in tables.

Indicative abstracts

Indicative abstracts simply describe what the research project is about.

Indicative Example

Porter, L. (2014). Benedict Cumberbatch, transition completed: Films, fame, fans . MX Publishing. Abstract retrieved from https://works.bepress.com/lynnette_porter/3/

Star Trek: Into Darkness, The Fifth Estate, 12 Years a Slave, August: Osage County, The Hobbit: The Desolation of Smaug—these would be milestones in most actors’ entire career. For Benedict Cumberbatch, roles in these films are merely a year’s additions to his already-vast resume. 2013 proved to be the final step in Cumberbatch’s transition from respected working actor to bona fide worldwide celebrity and recipient of BAFTA Los Angeles’ Britannia Award for British Artist of the Year. Like its predecessor, Benedict Cumberbatch, In Transition (MX Publishing, 2013), Benedict Cumberbatch, Transition Completed: Films, Fame, Fans explores the nature of Cumberbatch’s fame and fandom while analysing his most recent roles. This in-depth performance biography does more than critique the actor’s radio, stage, film, and television performances—especially his star turn in the long-awaited yet controversial third series of Sherlock. It also analyses how and why the actor’s work is so memorable in each role, a perspective unique to this performance biography. Cumberbatch’s role in popular culture, as much as his acting in multiple media, is well worth such scrutiny to illustrate that Benedict Cumberbatch represents both the best of acting and of the power of celebrity.

Best practices

Additional resources.

- Eagle Writer Eagle Writer is a writing and research resource you can use throughout your time at ERAU. The skills discussed here will help you write at the college level, which is applicable to courses across the university.

- Virtual Communication Lab (VCL) The Virtual Communication Lab offers free tutoring, workshops, and online resources to support students with speech and writing help.

Got questions? Get answers!

Email a librarian, phone a librarian.

Need help on the go, or an answer to a quick question. Call or Text Us!

- Call: (386) 226-7656 or (800) 678-9428

- Text: (386) 968-8843

- Last Updated: May 15, 2023 8:31 AM

- URL: https://guides.erau.edu/abstracts

Hunt Library

Mori Hosseini Student Union 1 Aerospace Boulevard Daytona Beach, FL 32114

Phone: 386-226-6595 Toll-Free: 800-678-9428

Maps and Parking

- Report a Problem

- Suggest a Purchase

Library Information

- Departments and Staff

- Library Collections

- Library Facilities

- Library Newsletter

- Hunt Library Employment

University Initiatives

- Scholarly Commons

- Data Commons

- University Archives

- Open and Affordable Textbooks

When you choose to publish with PLOS, your research makes an impact. Make your work accessible to all, without restrictions, and accelerate scientific discovery with options like preprints and published peer review that make your work more Open.

- PLOS Biology

- PLOS Climate

- PLOS Complex Systems

- PLOS Computational Biology

- PLOS Digital Health

- PLOS Genetics

- PLOS Global Public Health

- PLOS Medicine

- PLOS Mental Health

- PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases

- PLOS Pathogens

- PLOS Sustainability and Transformation

- PLOS Collections

- How to Write an Abstract

Expedite peer review, increase search-ability, and set the tone for your study

The abstract is your chance to let your readers know what they can expect from your article. Learn how to write a clear, and concise abstract that will keep your audience reading.

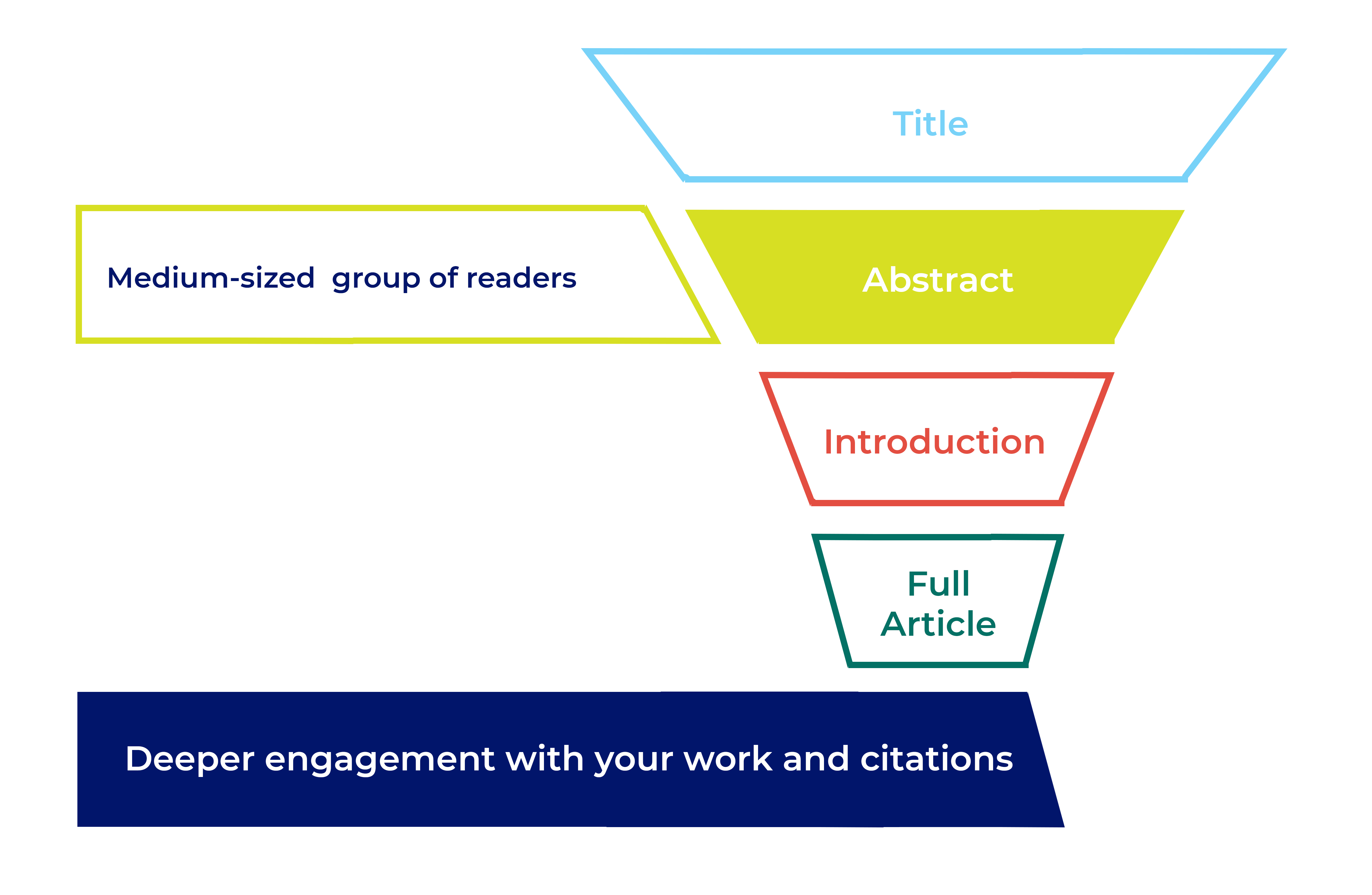

How your abstract impacts editorial evaluation and future readership

After the title , the abstract is the second-most-read part of your article. A good abstract can help to expedite peer review and, if your article is accepted for publication, it’s an important tool for readers to find and evaluate your work. Editors use your abstract when they first assess your article. Prospective reviewers see it when they decide whether to accept an invitation to review. Once published, the abstract gets indexed in PubMed and Google Scholar , as well as library systems and other popular databases. Like the title, your abstract influences keyword search results. Readers will use it to decide whether to read the rest of your article. Other researchers will use it to evaluate your work for inclusion in systematic reviews and meta-analysis. It should be a concise standalone piece that accurately represents your research.

What to include in an abstract

The main challenge you’ll face when writing your abstract is keeping it concise AND fitting in all the information you need. Depending on your subject area the journal may require a structured abstract following specific headings. A structured abstract helps your readers understand your study more easily. If your journal doesn’t require a structured abstract it’s still a good idea to follow a similar format, just present the abstract as one paragraph without headings.

Background or Introduction – What is currently known? Start with a brief, 2 or 3 sentence, introduction to the research area.

Objectives or Aims – What is the study and why did you do it? Clearly state the research question you’re trying to answer.

Methods – What did you do? Explain what you did and how you did it. Include important information about your methods, but avoid the low-level specifics. Some disciplines have specific requirements for abstract methods.

- CONSORT for randomized trials.

- STROBE for observational studies

- PRISMA for systematic reviews and meta-analyses

Results – What did you find? Briefly give the key findings of your study. Include key numeric data (including confidence intervals or p values), where possible.

Conclusions – What did you conclude? Tell the reader why your findings matter, and what this could mean for the ‘bigger picture’ of this area of research.

Writing tips

The main challenge you may find when writing your abstract is keeping it concise AND convering all the information you need to.

- Keep it concise and to the point. Most journals have a maximum word count, so check guidelines before you write the abstract to save time editing it later.

- Write for your audience. Are they specialists in your specific field? Are they cross-disciplinary? Are they non-specialists? If you’re writing for a general audience, or your research could be of interest to the public keep your language as straightforward as possible. If you’re writing in English, do remember that not all of your readers will necessarily be native English speakers.

- Focus on key results, conclusions and take home messages.

- Write your paper first, then create the abstract as a summary.

- Check the journal requirements before you write your abstract, eg. required subheadings.

- Include keywords or phrases to help readers search for your work in indexing databases like PubMed or Google Scholar.

- Double and triple check your abstract for spelling and grammar errors. These kind of errors can give potential reviewers the impression that your research isn’t sound, and can make it easier to find reviewers who accept the invitation to review your manuscript. Your abstract should be a taste of what is to come in the rest of your article.

Don’t

- Sensationalize your research.

- Speculate about where this research might lead in the future.

- Use abbreviations or acronyms (unless absolutely necessary or unless they’re widely known, eg. DNA).

- Repeat yourself unnecessarily, eg. “Methods: We used X technique. Results: Using X technique, we found…”

- Contradict anything in the rest of your manuscript.

- Include content that isn’t also covered in the main manuscript.

- Include citations or references.

Tip: How to edit your work

Editing is challenging, especially if you are acting as both a writer and an editor. Read our guidelines for advice on how to refine your work, including useful tips for setting your intentions, re-review, and consultation with colleagues.

- How to Write a Great Title

- How to Write Your Methods

- How to Report Statistics

- How to Write Discussions and Conclusions

- How to Edit Your Work

The contents of the Peer Review Center are also available as a live, interactive training session, complete with slides, talking points, and activities. …

The contents of the Writing Center are also available as a live, interactive training session, complete with slides, talking points, and activities. …

There’s a lot to consider when deciding where to submit your work. Learn how to choose a journal that will help your study reach its audience, while reflecting your values as a researcher…

Office of Undergraduate Research

- Office of Undergraduate Research FAQ's

- URSA Engage

- Resources for Students

- Resources for Faculty

- Engaging in Research

- Presenting Your Research

- Earn Money by Participating in Research Studies

- Transcript Notation

- Student Publications

How to Write an Abstract

How to write an abstract for a conference, what is an abstract and why is it important, an abstract is a brief summary of your research or creative project, usually about a paragraph long (250-350 words), and is written when you are ready to present your research or included in a thesis or research publication..

For additional support in writing your abstract, you can contact the Office of URSA at [email protected] or schedule a time to meet with a Writing and Research Consultant at the OSU Writing Center

Main Components of an Abstract:

The opening sentences should summarize your topic and describe what researchers already know, with reference to the literature.

A brief discussion that clearly states the purpose of your research or creative project. This should give general background information on your work and allow people from different fields to understand what you are talking about. Use verbs like investigate, analyze, test, etc. to describe how you began your work.

In this section you will be discussing the ways in which your research was performed and the type of tools or methodological techniques you used to conduct your research.

This is where you describe the main findings of your research study and what you have learned. Try to include only the most important findings of your research that will allow the reader to understand your conclusions. If you have not completed the project, talk about your anticipated results and what you expect the outcomes of the study to be.

Significance

This is the final section of your abstract where you summarize the work performed. This is where you also discuss the relevance of your work and how it advances your field and the scientific field in general.

- Your word count for a conference may be limited, so make your abstract as clear and concise as possible.

- Organize it by using good transition words found on the lef so the information flows well.

- Have your abstract proofread and receive feedback from your supervisor, advisor, peers, writing center, or other professors from different disciplines.

- Double-check on the guidelines for your abstract and adhere to any formatting or word count requirements.

- Do not include bibliographic references or footnotes.

- Avoid the overuse of technical terms or jargon.

Feeling stuck? Visit the OSU ScholarsArchive for more abstract examples related to your field

Contact Info

618 Kerr Administration Building Corvallis, OR 97331

541-737-5105

- Resources Home 🏠

- Try SciSpace Copilot

- Search research papers

- Add Copilot Extension

- Try AI Detector

- Try Paraphraser

- Try Citation Generator

- April Papers

- June Papers

- July Papers

Abstract Writing: A Step-by-Step Guide With Tips & Examples

Table of Contents

Introduction

Abstracts of research papers have always played an essential role in describing your research concisely and clearly to researchers and editors of journals, enticing them to continue reading. However, with the widespread availability of scientific databases, the need to write a convincing abstract is more crucial now than during the time of paper-bound manuscripts.

Abstracts serve to "sell" your research and can be compared with your "executive outline" of a resume or, rather, a formal summary of the critical aspects of your work. Also, it can be the "gist" of your study. Since most educational research is done online, it's a sign that you have a shorter time for impressing your readers, and have more competition from other abstracts that are available to be read.

The APCI (Academic Publishing and Conferences International) articulates 12 issues or points considered during the final approval process for conferences & journals and emphasises the importance of writing an abstract that checks all these boxes (12 points). Since it's the only opportunity you have to captivate your readers, you must invest time and effort in creating an abstract that accurately reflects the critical points of your research.

With that in mind, let’s head over to understand and discover the core concept and guidelines to create a substantial abstract. Also, learn how to organise the ideas or plots into an effective abstract that will be awe-inspiring to the readers you want to reach.

What is Abstract? Definition and Overview

The word "Abstract' is derived from Latin abstractus meaning "drawn off." This etymological meaning also applies to art movements as well as music, like abstract expressionism. In this context, it refers to the revealing of the artist's intention.

Based on this, you can determine the meaning of an abstract: A condensed research summary. It must be self-contained and independent of the body of the research. However, it should outline the subject, the strategies used to study the problem, and the methods implemented to attain the outcomes. The specific elements of the study differ based on the area of study; however, together, it must be a succinct summary of the entire research paper.

Abstracts are typically written at the end of the paper, even though it serves as a prologue. In general, the abstract must be in a position to:

- Describe the paper.

- Identify the problem or the issue at hand.

- Explain to the reader the research process, the results you came up with, and what conclusion you've reached using these results.

- Include keywords to guide your strategy and the content.

Furthermore, the abstract you submit should not reflect upon any of the following elements:

- Examine, analyse or defend the paper or your opinion.

- What you want to study, achieve or discover.

- Be redundant or irrelevant.

After reading an abstract, your audience should understand the reason - what the research was about in the first place, what the study has revealed and how it can be utilised or can be used to benefit others. You can understand the importance of abstract by knowing the fact that the abstract is the most frequently read portion of any research paper. In simpler terms, it should contain all the main points of the research paper.

What is the Purpose of an Abstract?

Abstracts are typically an essential requirement for research papers; however, it's not an obligation to preserve traditional reasons without any purpose. Abstracts allow readers to scan the text to determine whether it is relevant to their research or studies. The abstract allows other researchers to decide if your research paper can provide them with some additional information. A good abstract paves the interest of the audience to pore through your entire paper to find the content or context they're searching for.

Abstract writing is essential for indexing, as well. The Digital Repository of academic papers makes use of abstracts to index the entire content of academic research papers. Like meta descriptions in the regular Google outcomes, abstracts must include keywords that help researchers locate what they seek.

Types of Abstract

Informative and Descriptive are two kinds of abstracts often used in scientific writing.

A descriptive abstract gives readers an outline of the author's main points in their study. The reader can determine if they want to stick to the research work, based on their interest in the topic. An abstract that is descriptive is similar to the contents table of books, however, the format of an abstract depicts complete sentences encapsulated in one paragraph. It is unfortunate that the abstract can't be used as a substitute for reading a piece of writing because it's just an overview, which omits readers from getting an entire view. Also, it cannot be a way to fill in the gaps the reader may have after reading this kind of abstract since it does not contain crucial information needed to evaluate the article.

To conclude, a descriptive abstract is:

- A simple summary of the task, just summarises the work, but some researchers think it is much more of an outline

- Typically, the length is approximately 100 words. It is too short when compared to an informative abstract.

- A brief explanation but doesn't provide the reader with the complete information they need;

- An overview that omits conclusions and results

An informative abstract is a comprehensive outline of the research. There are times when people rely on the abstract as an information source. And the reason is why it is crucial to provide entire data of particular research. A well-written, informative abstract could be a good substitute for the remainder of the paper on its own.

A well-written abstract typically follows a particular style. The author begins by providing the identifying information, backed by citations and other identifiers of the papers. Then, the major elements are summarised to make the reader aware of the study. It is followed by the methodology and all-important findings from the study. The conclusion then presents study results and ends the abstract with a comprehensive summary.

In a nutshell, an informative abstract:

- Has a length that can vary, based on the subject, but is not longer than 300 words.

- Contains all the content-like methods and intentions

- Offers evidence and possible recommendations.

Informative Abstracts are more frequent than descriptive abstracts because of their extensive content and linkage to the topic specifically. You should select different types of abstracts to papers based on their length: informative abstracts for extended and more complex abstracts and descriptive ones for simpler and shorter research papers.

What are the Characteristics of a Good Abstract?

- A good abstract clearly defines the goals and purposes of the study.

- It should clearly describe the research methodology with a primary focus on data gathering, processing, and subsequent analysis.

- A good abstract should provide specific research findings.

- It presents the principal conclusions of the systematic study.

- It should be concise, clear, and relevant to the field of study.

- A well-designed abstract should be unifying and coherent.

- It is easy to grasp and free of technical jargon.

- It is written impartially and objectively.

What are the various sections of an ideal Abstract?

By now, you must have gained some concrete idea of the essential elements that your abstract needs to convey . Accordingly, the information is broken down into six key sections of the abstract, which include:

An Introduction or Background

Research methodology, objectives and goals, limitations.

Let's go over them in detail.

The introduction, also known as background, is the most concise part of your abstract. Ideally, it comprises a couple of sentences. Some researchers only write one sentence to introduce their abstract. The idea behind this is to guide readers through the key factors that led to your study.

It's understandable that this information might seem difficult to explain in a couple of sentences. For example, think about the following two questions like the background of your study:

- What is currently available about the subject with respect to the paper being discussed?

- What isn't understood about this issue? (This is the subject of your research)

While writing the abstract’s introduction, make sure that it is not lengthy. Because if it crosses the word limit, it may eat up the words meant to be used for providing other key information.

Research methodology is where you describe the theories and techniques you used in your research. It is recommended that you describe what you have done and the method you used to get your thorough investigation results. Certainly, it is the second-longest paragraph in the abstract.

In the research methodology section, it is essential to mention the kind of research you conducted; for instance, qualitative research or quantitative research (this will guide your research methodology too) . If you've conducted quantitative research, your abstract should contain information like the sample size, data collection method, sampling techniques, and duration of the study. Likewise, your abstract should reflect observational data, opinions, questionnaires (especially the non-numerical data) if you work on qualitative research.

The research objectives and goals speak about what you intend to accomplish with your research. The majority of research projects focus on the long-term effects of a project, and the goals focus on the immediate, short-term outcomes of the research. It is possible to summarise both in just multiple sentences.

In stating your objectives and goals, you give readers a picture of the scope of the study, its depth and the direction your research ultimately follows. Your readers can evaluate the results of your research against the goals and stated objectives to determine if you have achieved the goal of your research.

In the end, your readers are more attracted by the results you've obtained through your study. Therefore, you must take the time to explain each relevant result and explain how they impact your research. The results section exists as the longest in your abstract, and nothing should diminish its reach or quality.

One of the most important things you should adhere to is to spell out details and figures on the results of your research.

Instead of making a vague assertion such as, "We noticed that response rates varied greatly between respondents with high incomes and those with low incomes", Try these: "The response rate was higher for high-income respondents than those with lower incomes (59 30 percent vs. 30 percent in both cases; P<0.01)."

You're likely to encounter certain obstacles during your research. It could have been during data collection or even during conducting the sample . Whatever the issue, it's essential to inform your readers about them and their effects on the research.

Research limitations offer an opportunity to suggest further and deep research. If, for instance, you were forced to change for convenient sampling and snowball samples because of difficulties in reaching well-suited research participants, then you should mention this reason when you write your research abstract. In addition, a lack of prior studies on the subject could hinder your research.

Your conclusion should include the same number of sentences to wrap the abstract as the introduction. The majority of researchers offer an idea of the consequences of their research in this case.

Your conclusion should include three essential components:

- A significant take-home message.

- Corresponding important findings.

- The Interpretation.

Even though the conclusion of your abstract needs to be brief, it can have an enormous influence on the way that readers view your research. Therefore, make use of this section to reinforce the central message from your research. Be sure that your statements reflect the actual results and the methods you used to conduct your research.

Good Abstract Examples

Abstract example #1.

Children’s consumption behavior in response to food product placements in movies.

The abstract:

"Almost all research into the effects of brand placements on children has focused on the brand's attitudes or behavior intentions. Based on the significant differences between attitudes and behavioral intentions on one hand and actual behavior on the other hand, this study examines the impact of placements by brands on children's eating habits. Children aged 6-14 years old were shown an excerpt from the popular film Alvin and the Chipmunks and were shown places for the item Cheese Balls. Three different versions were developed with no placements, one with moderately frequent placements and the third with the highest frequency of placement. The results revealed that exposure to high-frequency places had a profound effect on snack consumption, however, there was no impact on consumer attitudes towards brands or products. The effects were not dependent on the age of the children. These findings are of major importance to researchers studying consumer behavior as well as nutrition experts as well as policy regulators."

Abstract Example #2

Social comparisons on social media: The impact of Facebook on young women’s body image concerns and mood. The abstract:

"The research conducted in this study investigated the effects of Facebook use on women's moods and body image if the effects are different from an internet-based fashion journal and if the appearance comparison tendencies moderate one or more of these effects. Participants who were female ( N = 112) were randomly allocated to spend 10 minutes exploring their Facebook account or a magazine's website or an appearance neutral control website prior to completing state assessments of body dissatisfaction, mood, and differences in appearance (weight-related and facial hair, face, and skin). Participants also completed a test of the tendency to compare appearances. The participants who used Facebook were reported to be more depressed than those who stayed on the control site. In addition, women who have the tendency to compare appearances reported more facial, hair and skin-related issues following Facebook exposure than when they were exposed to the control site. Due to its popularity it is imperative to conduct more research to understand the effect that Facebook affects the way people view themselves."

Abstract Example #3

The Relationship Between Cell Phone Use and Academic Performance in a Sample of U.S. College Students

"The cellphone is always present on campuses of colleges and is often utilised in situations in which learning takes place. The study examined the connection between the use of cell phones and the actual grades point average (GPA) after adjusting for predictors that are known to be a factor. In the end 536 students in the undergraduate program from 82 self-reported majors of an enormous, public institution were studied. Hierarchical analysis ( R 2 = .449) showed that use of mobile phones is significantly ( p < .001) and negative (b equal to -.164) connected to the actual college GPA, after taking into account factors such as demographics, self-efficacy in self-regulated learning, self-efficacy to improve academic performance, and the actual high school GPA that were all important predictors ( p < .05). Therefore, after adjusting for other known predictors increasing cell phone usage was associated with lower academic performance. While more research is required to determine the mechanisms behind these results, they suggest the need to educate teachers and students to the possible academic risks that are associated with high-frequency mobile phone usage."

Quick tips on writing a good abstract

There exists a common dilemma among early age researchers whether to write the abstract at first or last? However, it's recommended to compose your abstract when you've completed the research since you'll have all the information to give to your readers. You can, however, write a draft at the beginning of your research and add in any gaps later.

If you find abstract writing a herculean task, here are the few tips to help you with it:

1. Always develop a framework to support your abstract

Before writing, ensure you create a clear outline for your abstract. Divide it into sections and draw the primary and supporting elements in each one. You can include keywords and a few sentences that convey the essence of your message.

2. Review Other Abstracts

Abstracts are among the most frequently used research documents, and thousands of them were written in the past. Therefore, prior to writing yours, take a look at some examples from other abstracts. There are plenty of examples of abstracts for dissertations in the dissertation and thesis databases.

3. Avoid Jargon To the Maximum

When you write your abstract, focus on simplicity over formality. You should write in simple language, and avoid excessive filler words or ambiguous sentences. Keep in mind that your abstract must be readable to those who aren't acquainted with your subject.

4. Focus on Your Research

It's a given fact that the abstract you write should be about your research and the findings you've made. It is not the right time to mention secondary and primary data sources unless it's absolutely required.

Conclusion: How to Structure an Interesting Abstract?

Abstracts are a short outline of your essay. However, it's among the most important, if not the most important. The process of writing an abstract is not straightforward. A few early-age researchers tend to begin by writing it, thinking they are doing it to "tease" the next step (the document itself). However, it is better to treat it as a spoiler.

The simple, concise style of the abstract lends itself to a well-written and well-investigated study. If your research paper doesn't provide definitive results, or the goal of your research is questioned, so will the abstract. Thus, only write your abstract after witnessing your findings and put your findings in the context of a larger scenario.

The process of writing an abstract can be daunting, but with these guidelines, you will succeed. The most efficient method of writing an excellent abstract is to centre the primary points of your abstract, including the research question and goals methods, as well as key results.

Interested in learning more about dedicated research solutions? Go to the SciSpace product page to find out how our suite of products can help you simplify your research workflows so you can focus on advancing science.

The best-in-class solution is equipped with features such as literature search and discovery, profile management, research writing and formatting, and so much more.

But before you go,

You might also like.

Consensus GPT vs. SciSpace GPT: Choose the Best GPT for Research

Literature Review and Theoretical Framework: Understanding the Differences

Types of Essays in Academic Writing - Quick Guide (2024)

Abstracts are formal summaries writers prepare of their completed work. Abstracts are important tools for readers, especially as they try to keep up with an explosion of information in print and on the Internet.

Definition of Abstract

Abstracts, like all summaries, cover the main points of a piece of writing. Unlike executive summaries written for non-specialist audiences, abstracts use the same level of technical language and expertise found in the article itself. And unlike general summaries which can be adapted in many ways to meet various readers' and writers' needs, abstracts are typically 150 to 250 words and follow set patterns.

Because readers use abstracts for set purposes, these purposes further define abstracts.

Purposes for Abstracts

Abstracts typically serve five main goals:

Help readers decide if they should read an entire article

Readers use abstracts to see if a piece of writing interests them or relates to a topic they're working on. Rather than tracking down hundreds of articles, readers rely on abstracts to decide quickly if an article is pertinent. Equally important, readers use abstracts to help them gauge the sophistication or complexity of a piece of writing. If the abstract is too technical or too simplistic, readers know that the article will also be too technical or too simplistic.

Help readers and researchers remember key findings on a topic

Even after reading an article, readers often keep abstracts to remind them of which sources support conclusions. Because abstracts include complete bibliographic citations, they are helpful when readers begin writing up their research and citing sources.

Help readers understand a text by acting as a pre-reading outline of key points

Like other pre-reading strategies, reading an abstract before reading an article helps readers anticipate what's coming in the text itself. Using an abstract to get an overview of the text makes reading the text easier and more efficient.

Index articles for quick recovery and cross-referencing

Even before computers made indexing easier, abstracts helped librarians and researchers find information more easily. With so many indexes now available electronically, abstracts with their keywords are even more important because readers can review hundreds of abstracts quickly to find the ones most useful for their research. Moreover, cross-referencing through abstracts opens up new areas of research that readers might not have known about when they started researching a topic.

Allow supervisors to review technical work without becoming bogged down in details

Although many managers and supervisors will prefer the less technical executive summary, some managers need to keep abreast of technical work. Research shows that only 15% of managers read the complete text of reports or articles. Most managers, then, rely on the executive summary or abstract as the clearest overview of employees' work.

Types of Abstracts

Although you'll see two types of abstracts—informative and descriptive—most writers now provide informative abstracts of their work.

Descriptive Abstract

A descriptive abstract outlines the topics covered in a piece of writing so the reader can decide whether to read the entire document. In many ways, the descriptive abstract is like a table of contents in paragraph form. Unlike reading an informative abstract, reading a descriptive abstract cannot substitute for reading the document because it does not capture the content of the piece. Nor does a descriptive abstract fulfill the other main goals of abstracts as well as informative abstracts do. For all these reasons, descriptive abstracts are less and less common. Check with your instructor or the editor of the journal to which you are submitting a paper for details on the appropriate type of abstract for your audience.

Informative Abstract

An informative abstract provides detail about the substance of a piece of writing because readers will sometimes rely on the abstract alone for information. Informative abstracts typically follow this format:

- Identifying information (bibliographic citation or other identification of the document)

- Concise restatement of the main point, including the initial problem or other background

- Methodology (for experimental work) and key findings

- Major conclusions

Informative abstracts usually appear in indexes like Dissertation Abstracts International ; however, your instructor may ask you to write one as a cover sheet to a paper as well.

A More Detailed Comparison of Descriptive vs. Informative

The typical distinction between descriptive and informative is that the descriptive abstract is like a table of contents whereas the informative abstract lays out the content of the document. To show the differences as clearly as possible, we compare a shortened Table of Contents for a 100-page legal argument presented by the FDA and an informative abstract of the judge's decision in the case.

Related Information: Informative Abstract of the Decision

Summary of Federal District Court's Ruling on FDA's Jurisdiction Over, and Regulation of, Cigarettes and Smokeless Tobacco

May 2, 1997

http://www.fda.gov/opacom/backgrounders/bg97-9.html

On April 25, 1997, Judge William Osteen of the Federal District Court in Greensboro, North Carolina, ruled that FDA has jurisdiction under the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act to regulate nicotine-containing cigarettes and smokeless tobacco. The Court held that "tobacco products fit within the FDCA's definitions of drug and device, and that FDA can regulate cigarettes and smokeless tobacco products as drug delivery devices under the combination product and restricted device provisions of the Act.

With respect to the tobacco rule, the Court upheld all restrictions involving youth access and labeling, including two access provisions that went into effect Feb. 28: (1) the prohibition on sales of cigarettes and smokeless tobacco products to children and adolescents under 18, and (2) the requirement that retailers check photo identification of customers who are under 27 years of age.

The Court also upheld additional access and labeling restrictions originally scheduled to go into effect Aug. 28, 1997, including a prohibition on self-service displays and the placement of vending machines where children have access to them. The Court also upheld the ban on distribution of free samples, the sale of so-called kiddie packs of less than 20 cigarettes, and the sale of individual cigarettes. However, the Court delayed implementation of the provisions that have not yet gone into effect pending further action by the Court.

The Court invalidated on statutory grounds FDA's restrictions on the advertising and promotion of cigarettes and smokeless tobacco. Judge Osteen found that the statutory provision relied on by FDA, section 520(e) of the Act (21 U.S.C. 360j(e)), does not provide FDA with authority to regulate the advertising and promotion of tobacco products. Specifically, the Court found that the authority in that section to set "such other conditions" on the sale, distribution, or use of a restricted device does not encompass advertising restrictions. Because Judge Osteen based his ruling on the advertising provisions on purely statutory grounds, he declined to consider the First Amendment challenge to those parts of the rule. The government is appealing the advertising portion of the ruling.

(accessed January 26, 1998)

Related Information: Sample Descriptive Abstract

"Bonanza Creek LTER [Long Term Ecological Research] 1997 Annual Progress Report" http://www.lter.alaska.edu/pubs/1997pr.html

We continue to document all major climatic variables in the uplands and floodplains at Bonanza Creek. In addition, we have documented the successional changes in microclimate in 9 successional upland and floodplain stands at Bonanza Creek (BNZ) and in four elevational locations at Caribou-Poker Creek (CPCRW). A sun photometer is operated cooperatively with NASA to estimate high-latitude atmospheric extinction coefficients for remote-sensing images. Electronic data are collected monthly and loaded into a database which produces monthly summaries. The data are checked for errors, documented, and placed on-line on the BNZ Web page. Climate data for the entire state have been summarized for the period of station records and krieged to produce maps of climate zones for Alaska based on growing-season and annual temperature and precipitation.

Related Information: Sample Informative Abstract based on Experimental Work

Palmquist, M., & Young, R. (1992). The Notion of Giftedness and Student Expectations About Writing. Written Communication, 9(1), 137-168.

Research reported by Daly, Miller, and their colleagues suggests that writing apprehension is related to a number of factors we do not yet fully understand. This study suggests that included among those factors should be the belief that writing ability is a gift. Giftedness, as it is referred to in the study, is roughly equivalent to the Romantic notion of original genius. Results from a survey of 247 postsecondary students enrolled in introductory writing courses at two institutions indicate that higher levels of belief in giftedness are correlated with higher levels of writing apprehension, lower self-assessments of writing ability, lower levels of confidence in achieving proficiency in certain writing activities and genres, and lower self-assessments of prior experience with writing instructors. Significant differences in levels of belief in giftedness were also found among students who differed in their perceptions of the most important purpose for writing, with students who identified "to express your own feelings about something" as the most important purpose for writing having the highest mean level of belief in giftedness. Although the validity of the notion that writing ability is a special gift is not directly addressed, the results suggest that belief in giftedness may have deleterious effects on student writers.

Related Information: Sample Informative Abstract based on Non-experimental Work

Environmental Impact Statement. Federal Register: December 11, 1997 (Volume 62, Number 238). "Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants; Proposed Revision of Special Regulations for the Gray Wolf." Fish and Wildlife Service, Department of the Interior.

http://www.epa.gov/fedrgstr/EPA-SPECIES/1997/December/Day-11/e32440.htm

On November 22, 1994, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service published special rules to establish nonessential experimental populations of gray wolves (Canis lupus) in Yellowstone National Park and central Idaho. The nonessential experimental population areas include all of Wyoming, most of Idaho, and much of central and southern Montana. A close reading of the special regulations indicates that, unintentionally, the language reads as though wolf control measures apply only outside of the experimental population area. This proposed revision is intended to amend language in the special regulations so that it clearly applies within the Yellowstone nonessential experimental population area and the central Idaho nonessential experimental population area. This proposed change will not affect any of the assumptions and earlier analysis made in the environmental impact statement or other portions of the special rules. (accessed January 26, 1998)

Related Information: Table of Contents of the Argument

Court Brief (edited Table of Contents) Filed Dec. 2, 1996, by the Department of Justice in defense of FDA's determination of jurisdiction over cigarettes and smokeless tobacco products and its regulations restricting those products to protect children and adolescents. http://www.usdoj.gov/civil/cases/tocnts.htm Statement of the matter before the court; statement of material facts

- The health effects of cigarettes and smokeless tobacco

- The evidence that nicotine in cigarettes and smokeless tobacco "affect[s] the structure or any function of the body"

- The evidence that the pharmacological effects of nicotine in cigarettes and smokeless tobacco are "intended"

- The evidence that cigarettes and smokeless tobacco are "combination products"

- Cigarettes and smokeless tobacco as combination products

- The regulatory goal

- Youth access restrictions

- Advertising and promotion restrictions

Questions Presented

Congress has not precluded FDA from regulating cigarettes and smokeless tobacco under the FDCA.

- Standard of review: Chevron, U.S.A., Inc. v. Natural Resources Defense Council, Inc.

- Chevron, step one