An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Springer Nature - PMC COVID-19 Collection

The Use of Critical Thinking to Identify Fake News: A Systematic Literature Review

Paul machete.

Department of Informatics, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, 0001 South Africa

Marita Turpin

With the large amount of news currently being published online, the ability to evaluate the credibility of online news has become essential. While there are many studies involving fake news and tools on how to detect it, there is a limited amount of work that focuses on the use of information literacy to assist people to critically access online information and news. Critical thinking, as a form of information literacy, provides a means to critically engage with online content, for example by looking for evidence to support claims and by evaluating the plausibility of arguments. The purpose of this study is to investigate the current state of knowledge on the use of critical thinking to identify fake news. A systematic literature review (SLR) has been performed to identify previous studies on evaluating the credibility of news, and in particular to see what has been done in terms of the use of critical thinking to evaluate online news. During the SLR’s sifting process, 22 relevant studies were identified. Although some of these studies referred to information literacy, only three explicitly dealt with critical thinking as a means to identify fake news. The studies on critical thinking noted critical thinking as an essential skill for identifying fake news. The recommendation of these studies was that information literacy be included in academic institutions, specifically to encourage critical thinking.

Introduction

The information age has brought a significant increase in available sources of information; this is in line with the unparalleled increase in internet availability and connection, in addition to the accessibility of technological devices [ 1 ]. People no longer rely on television and print media alone for obtaining news, but increasingly make use of social media and news apps. The variety of information sources that we have today has contributed to the spread of alternative facts [ 1 ]. With over 1.8 billion active users per month in 2016 [ 2 ], Facebook accounted for 20% of total traffic to reliable websites and up to 50% of all the traffic to fake news sites [ 3 ]. Twitter comes second to Facebook, with over 400 million active users per month [ 2 ]. Posts on social media platforms such as Facebook and Twitter spread rapidly due to how they attempt to grab the readers’ attention as quickly as possible, with little substantive information provided, and thus create a breeding ground for the dissemination of fake news [ 4 ].

While social media is a convenient way of accessing news and staying connected to friends and family, it is not easy to distinguish real news from fake news on social media [ 5 ]. Social media continues to contribute to the increasing distribution of user-generated information; this includes hoaxes, false claims, fabricated news and conspiracy theories, with primary sources being social media platforms such as Facebook and Twitter [ 6 ]. This means that any person who is in possession of a device, which can connect to the internet, is potentially a consumer or distributor of fake news. While social media platforms and search engines do not encourage people to believe the information being circulated, they are complicit in people’s propensity to believe the information they come across on these platforms, without determining their validity [ 6 ]. The spread of fake news can cause a multitude of damages to the subject; varying from reputational damage of an individual, to having an effect on the perceived value of a company [ 7 ].

The purpose of this study is to investigate the use of critical thinking methods to detect news stories that are untrue or otherwise help to develop a critical attitude to online news. This work was performed by means of a systematic literature review (SLR). The paper is presented as follows. The next section provides background information on fake news, its importance in the day-to-day lives of social media users and how information literacy and critical thinking can be used to identify fake news. Thereafter, the SLR research approach is discussed. Following this, the findings of the review are reported, first in terms of descriptive statistics and the in terms of a thematic analysis of the identified studies. The paper ends with the Conclusion and recommendations.

Background: Fake News, Information Literacy and Critical Thinking

This section discusses the history of fake news, the fake news that we know today and the role of information literacy can be used to help with the identification of fake news. It also provides a brief definition of critical thinking.

The History of Fake News

Although fake news has received increased attention recently, the term has been used by scholars for many years [ 4 ]. Fake news emerged from the tradition of yellow journalism of the 1890s, which can be described as a reliance on the familiar aspects of sensationalism—crime news, scandal and gossip, divorces and sex, and stress upon the reporting of disasters, sports sensationalism as well as possibly satirical news [ 5 ]. The emergence of online news in the early 2000s raised concerns, among them being that people who share similar ideologies may form “echo chambers” where they can filter out alternative ideas [ 2 ]. This emergence came about as news media transformed from one that was dominated by newspapers printed by authentic and trusted journalists to one where online news from an untrusted source is believed by many [ 5 ]. The term later grew to describe “satirical news shows”, “parody news shows” or “fake-news comedy shows” where a television show, or segment on a television show was dedicated to political satire [ 4 ]. Some of these include popular television shows such as The Daily Show (now with Trevor Noah), Saturday Night Live ’s “The Weekend Update” segment, and other similar shows such as Last Week Tonight with John Oliver and The Colbert Report with Stephen Colbert [ 4 ]. News stories in these shows were labelled “fake” not because of their content, but for parodying network news for the use of sarcasm, and using comedy as a tool to engage real public issues [ 4 ]. The term “Fake News” further became prominent during the course of the 2016 US presidential elections, as members of the opposing parties would post incorrect news headlines in order to sway the decision of voters [ 6 ].

Fake News Today

The term fake news has a more literal meaning today [ 4 ]. The Macquarie Dictionary named fake news the word of the year for 2016 [ 8 ]. In this dictionary, fake news is described it as a word that captures a fascinating evolution in the creation of deceiving content, also allowing people to believe what they see fit. There are many definitions for the phrase, however, a concise description of the term can be found in Paskin [ 4 ] who states that certain news articles originating from either social media or mainstream (online or offline) platforms, that are not factual, but are presented as such and are not satirical, are considered fake news. In some instances, editorials, reports, and exposés may be knowingly disseminating information with intent to deceive for the purposes of monetary or political benefit [ 4 ].

A distinction amongst three types of fake news can be made on a conceptual level, namely: serious fabrications, hoaxes and satire [ 3 ]. Serious fabrications are explained as news items written on false information, including celebrity gossip. Hoaxes refer to false information provided via social media, aiming to be syndicated by traditional news platforms. Lastly, satire refers to the use of humour in the news to imitate real news, but through irony and absurdity. Some examples of famous satirical news platforms in circulation in the modern day are The Onion and The Beaverton , when contrasted with real news publishers such as The New York Times [ 3 ].

Although there are many studies involving fake news and tools on how to detect it, there is a limited amount of academic work that focuses on the need to encourage information literacy so that people are able to critically access the information they have been presented, in order to make better informed decisions [ 9 ].

Stein-Smith [ 5 ] urges that information/media literacy has become a more critical skill since the appearance of the notion of fake news has become public conversation. Information literacy is no longer a nice-to-have proficiency but a requirement for interpreting news headlines and participation in public discussions. It is essential for academic institutions of higher learning to present information literacy courses that will empower students and staff members with the prerequisite tools to identify, select, understand and use trustworthy information [ 1 ]. Outside of its academic uses, information literacy is also a lifelong skill with multiple applications in everyday life [ 5 ]. The choices people make in their lives, and opinions they form need to be informed by the appropriate interpretation of correct, opportune, and significant information [ 5 ].

Critical Thinking

Critical thinking covers a broad range of skills that includes the following: verbal reasoning skills; argument analysis; thinking as hypothesis testing; dealing with likelihood and uncertainties; and decision making and problem solving skills [ 10 ]. For the purpose of this study, where we are concerned with the evaluation of the credibility of online news, the following definition will be used: critical thinking is “the ability to analyse and evaluate arguments according to their soundness and credibility, respond to arguments and reach conclusions through deduction from given information” [ 11 ]. In this study, we want to investigate how the skills mentioned by [ 11 ] can be used as part of information literacy, to better identify fake news.

The next section presents the research approach that was followed to perform the SLR.

Research Method

This section addresses the research question, the search terms that were applied to a database in relation to the research question, as well as the search criteria used on the search results. The following research question was addressed in this SLR:

- What is the role of critical thinking in identifying fake news, according to previous studies?

The research question was identified in accordance to the research topic. The intention of the research question is to determine if the identified studies in this review provide insights into the use of critical thinking to evaluate the credibility of online news and in particular to identify fake news.

Delimitations.

In the construction of this SLR, the following definitions of fake news and other related terms have been excluded, following the suggestion of [ 2 ]:

- Unintentional reporting mistakes;

- Rumours that do not originate from a particular news article;

- Conspiracy theories;

- Satire that is unlikely to be misconstrued as factual;

- False statements by politicians; and

- Reports that are slanted or misleading, but not outright false.

Search Terms.

The database tool used to extract sources to conduct the SLR was Google Scholar ( https://scholar.google.com ). The process for extracting the sources involved executing the search string on Google Scholar and the retrieval of the articles and their meta-data into a tool called Mendeley, which was used for reference management.

The search string used to retrieve the sources was defined below:

(“critical think*” OR “critically (NEAR/2) reason*” OR “critical (NEAR/2) thought*” OR “critical (NEAR/2) judge*” AND “fake news” AND (identify* OR analyse* OR find* OR describe* OR review).

To construct the search criteria, the following factors have been taken into consideration: the research topic guided the search string, as the key words were used to create the base search criteria. The second step was to construct the search string according to the search engine requirements on Google Scholar.

Selection Criteria.

The selection criteria outlined the rules applied in the SLR to identify sources, narrow down the search criteria and focus the study on a specific topic. The inclusion and exclusion criteria are outlined in Table 1 to show which filters were applied to remove irrelevant sources.

Table 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria for paper selection

Source Selection.

The search criteria were applied on the online database and 91 papers were retrieved. The criteria in Table 1 were used on the search results in order to narrow down the results to appropriate papers only.

PRISMA Flowchart.

The selection criteria included four stages of filtering and this is depicted in Fig. 1 . In then Identification stage, the 91 search results from Google Scholar were returned and 3 sources were derived from the sources already identified from the search results, making a total of 94 available sources. In the screening stage, no duplicates were identified. After a thorough screening of the search results, which included looking at the availability of the article (free to use), 39 in total records were available – to which 55 articles were excluded. Of the 39 articles, nine were excluded based on their titles and abstract being irrelevant to the topic in the eligibility stage. A final list of 22 articles was included as part of this SLR. As preparation for the data analysis, a data extraction table was made that classified each article according to the following: article author; article title; theme (a short summary of the article); year; country; and type of publication. The data extraction table assisted in the analysis of findings as presented in the next section.

PRISMA flowchart

Analysis of Findings

Descriptive statistics.

Due to the limited number of relevant studies, the information search did not have a specified start date. Articles were included up to 31 August 2019. The majority of the papers found were published in 2017 (8 papers) and 2018 (9 papers). This is in line with the term “fake news” being announced the word of the year in the 2016 [ 8 ].

The selected papers were classified into themes. Figure 2 is a Venn diagram that represents the overlap of articles by themes across the review. Articles that fall under the “fake news” theme had the highest number of occurrences, with 11 in total. Three articles focused mainly on “Critical Thinking”, and “Information Literacy” was the main focus of four articles. Two articles combined all three topics of critical thinking, information literacy, and fake news.

Venn diagram depicting the overlap of articles by main focus

An analysis of the number of articles published per country indicate that the US had a dominating amount of articles published on this topic, a total of 17 articles - this represents 74% of the selected articles in this review. The remaining countries where articles were published are Australia, Germany, Ireland, Lebanon, Saudi Arabia, and Sweden - with each having one article published.

In terms of publication type, 15 of the articles were journal articles, four were reports, one was a thesis, one was a magazine article and one, a web page.

Discussion of Themes

The following emerged from a thematic analysis of the articles.

Fake News and Accountability.

With the influence that social media has on the drive of fake news [ 2 ], who then becomes responsible for the dissemination and intake of fake news by the general population? The immediate assumption is that in the digital age, social media platforms like Facebook and Twitter should be able to curate information, or do some form of fact-checking when posts are uploaded onto their platforms [ 12 ], but that leans closely to infringing on freedom of speech. While different authors agree that there need to be measures in place for the minimisation of fake news being spread [ 12 , 13 ], where that accountability lies differs between the authors. Metaxas and Mustafaraj [ 13 ] aimed to develop algorithms or plug-ins that can assist in trust and postulated that consumers should be able to identify misinformation, thus making an informed decision on whether to share that information or not. Lazer et al. [ 12 ] on the other hand, believe the onus should be on the platform owners to put restrictions on the kind of data distributed. Considering that the work by Metaxas and Mustafaraj [ 13 ] was done seven years ago, one can conclude that the use of fact-checking algorithms/plug-ins has not been successful in curbing the propulsion of fake news.

Fake News and Student Research.

There were a total of four articles that had a focus on student research in relation to fake news. Harris, Paskin and Stein-Smith [ 4 , 5 , 14 ] all agree that students do not have the ability to discern between real and fake news. A Stanford History Education Group study reveals that students are not geared up for distinguishing real from fake news [ 4 ]. Most students are able to perform a simple Google search for information; however, they are unable to identify the author of an online source, or if the information is misleading [ 14 ]. Furthermore, students are not aware of the benefits of learning information literacy in school in equipping them with the skills required to accurately identify fake news [ 5 ]. At the Metropolitan Campus of Fairleigh Dickson University, librarians have undertaken the role of providing training on information literacy skills for identifying fake news [ 5 ].

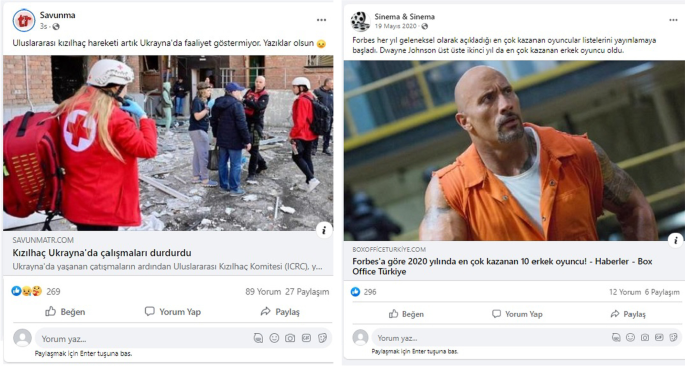

Fake News and Social Media.

A number of authors [ 6 , 15 ] are in agreement that social media, the leading source of news, is the biggest driving force for fake news. It provides substantial advantage to broadcast manipulated information. It is an open platform of unfiltered editors and open to contributions from all. According to Nielsen and Graves as well as Janetzko, [ 6 , 15 ], people are unable to identify fake news correctly. They are likely to associate fake news with low quality journalism than false information designed to mislead. Two articles, [ 15 ] and [ 6 ] discussed the role of critical thinking when interacting on social media. Social media presents information to us that has been filtered according to what we already consume, thereby making it a challenge for consumers to think critically. The study by Nielsen and Graves [ 6 ] confirm that students’ failure to verify incorrect online sources requires urgent attention as this could indicate that students are a simple target for presenting manipulated information.

Fake News That Drive Politics.

Two studies mention the effect of social and the spread of fake news, and how it may have propelled Donald Trump to win the US election in 2016 [ 2 , 16 ]. Also, [ 8 ] and [ 2 ] mention how a story on the Pope supporting Trump in his presidential campaign, was widely shared (more than a million times) on Facebook in 2016. These articles also point out how in the information age, fact-checking has become relatively easy, but people are more likely to trust their intuition on news stories they consume, rather than checking the reliability of a story. The use of paid trolls and Russian bots to populate social media feeds with misinformation in an effort to swing the US presidential election in Donald Trump’s favour, is highlighted [ 16 ]. The creation of fake news, with the use of alarmist headlines (“click bait”), generates huge traffic into the original websites, which drives up advertising revenue [ 2 ]. This means content creators are compelled to create fake news, to drive ad revenue on their websites - even though they may not be believe in the fake news themselves [ 2 ].

Information Literacy.

Information literacy is when a person has access to information, and thus can process the parts they need, and create ways in which to best use the information [ 1 ]. Teaching students the importance of information literacy skills is key, not only for identifying fake news but also for navigating life aspects that require managing and scrutinising information, as discussed by [ 1 , 17 ], and [ 9 ]. Courtney [ 17 ] highlights how journalism students, above students from other disciplines, may need to have some form of information literacy incorporated into their syllabi to increase their awareness of fake news stories, creating a narrative of being objective and reliable news creators. Courtney assessed different universities that teach journalism and media-related studies, and established that students generally lack awareness on how useful library services are in offering services related to information literacy. Courtney [ 17 ] and Rose-Wiles [ 9 ] discuss how the use of library resources should be normalised to students. With millennials and generation Z having social media as their first point of contact, Rose-Wiles [ 9 ] urges universities, colleges and other academic research institutes to promote the use of more library resources than those from the internet, to encourage students to lean on reliable sources. Overall, this may prove difficult, therefore Rose-Wiles [ 9 ] proposes that by teaching information literacy skills and critical thinking, students can use these skills to apply in any situation or information source.

Referred to as “truth decay”, people have reached a point where they no longer need to agree with facts [ 18 ]. Due to political polarisation, the general public hold the opinion of being part of an oppressed group of people, and therefore will believe a political leader who appeals to that narrative [ 18 ]. There needs to be tangible action put into driving civil engagement, to encourage people to think critically, analyse information and not believe everything they read.

Critical Thinking.

Only three of the articles had critical thinking as a main theme. Bronstein et al. [ 19 ] discuss how certain dogmatic and religious beliefs create a tendency in individuals to belief any information given, without them having a need to interrogate the information further and then deciding ion its veracity. The article further elaborates how these individuals are also more likely to engage in conspiracy theories, and tend to rationalise absurd events. Bronstein et al.’s [ 19 ] study conclude that dogmatism and religious fundamentalism highly correlate with a belief in fake news. Their study [ 19 ] suggests the use of interventions that aim to increase open-minded thinking, and also increase analytical thinking as a way to help religious, curb belief in fake news. Howlett [ 20 ] describes critical thinking as evidence-based practice, which is taking the theories of the skills and concepts of critical thinking and converting those for use in everyday applications. Jackson [ 21 ] explains how the internet purposely prides itself in being a platform for “unreviewed content”, due to the idea that people may not see said content again, therefore it needs to be attention-grabbing for this moment, and not necessarily accurate. Jackson [ 21 ] expands that social media affected critical thinking in how it changed the view on published information, what is now seen as old forms of information media. This then presents a challenge to critical thinking in that a large portion of information found on the internet is not only unreliable, it may also be false. Jackson [ 21 ] posits that one of the biggest dangers to critical thinking may be that people have a sense of perceived power for being able to find the others they seek with a simple web search. People are no longer interested in evaluation the credibility of the information they receive and share, and thus leading to the propagation of fake news [ 21 ].

Discussion of Findings

The aggregated data in this review has provided insight into how fake news is perceived, the level of attention it is receiving and the shortcomings of people when identifying fake news. Since the increase in awareness of fake news in 2016, there has been an increase in academic focus on the subject, with most of the articles published between 2017 and 2018. Fifty percent of the articles released focused on the subject of fake news, with 18% reflecting on information literacy, and only 13% on critical thinking.

The thematic discussion grouped and synthesised the articles in this review according to the main themes of fake news, information literacy and critical thinking. The Fake news and accountability discussion raised the question of who becomes accountable for the spreading of fake news between social media and the user. The articles presented a conclusion that fact-checking algorithms are not successful in reducing the dissemination of fake news. The discussion also included a focus on fake news and student research , whereby a Stanford History Education Group study revealed that students are not well educated in thinking critically and identifying real from fake news [ 4 ]. The Fake news and social media discussion provided insight on social media is the leading source of news as well as a contributor to fake news. It provides a challenge for consumers who are not able to think critically about online news, or have basic information literacy skills that can aid in identifying fake news. Fake news that drive politics highlighted fake news’ role in politics, particularly the 2016 US presidential elections and the influence it had on the voters [ 22 ].

Information literacy related publications highlighted the need for educating the public on being able to identify fake news, as well as the benefits of having information literacy as a life skill [ 1 , 9 , 17 ]. It was shown that students are often misinformed about the potential benefits of library services. The authors suggested that university libraries should become more recognised and involved as role-players in providing and assisting with information literacy skills.

The articles that focused on critical thinking pointed out two areas where a lack of critical thinking prevented readers from discerning between accurate and false information. In the one case, it was shown that people’s confidence in their ability to find information online gave made them overly confident about the accuracy of that information [ 21 ]. In the other case, it was shown that dogmatism and religious fundamentalism, which led people to believe certain fake news, were associated with a lack of critical thinking and a questioning mind-set [ 21 ].

The articles that focused on information literacy and critical thinking were in agreement on the value of promoting and teaching these skills, in particular to the university students who were often the subjects of the studies performed.

This review identified 22 articles that were synthesised and used as evidence to determine the role of critical thinking in identifying fake news. The articles were classified according to year of publication, country of publication, type of publication and theme. Based on the descriptive statistics, fake news has been a growing trend in recent years, predominantly in the US since the presidential election in 2016. The research presented in most of the articles was aimed at the assessment of students’ ability to identify fake news. The various studies were consistent in their findings of research subjects’ lack of ability to distinguish between true and fake news.

Information literacy emerged as a new theme from the studies, with Rose-Wiles [ 9 ] advising academic institutions to teach information literacy and encourage students to think critically when accessing online news. The potential role of university libraries to assist in not only teaching information literacy, but also assisting student to evaluate the credibility of online information, was highlighted. The three articles that explicitly dealt with critical thinking, all found critical thinking to be lacking among their research subjects. They further indicated how this lack of critical thinking could be linked to people’s inability to identify fake news.

This review has pointed out people’s general inability to identify fake news. It highlighted the importance of information literacy as well as critical thinking, as essential skills to evaluate the credibility of online information.

The limitations in this review include the use of students as the main participants in most of the research - this would indicate a need to shift the academic focus towards having the general public as participants. This is imperative because anyone who possesses a mobile device is potentially a contributor or distributor of fake news.

For future research, it is suggested that the value of the formal teaching of information literacy at universities be further investigated, as a means to assist students in assessing the credibility of online news. Given the very limited number of studies on the role of critical thinking to identify fake news, this is also an important area for further research.

Contributor Information

Marié Hattingh, Email: [email protected] .

Machdel Matthee, Email: [email protected] .

Hanlie Smuts, Email: [email protected] .

Ilias Pappas, Email: [email protected] .

Yogesh K. Dwivedi, Email: moc.liamg@ideviwdky .

Matti Mäntymäki, Email: [email protected] .

- LEARNING SKILLS

Critical Thinking and Fake News

Search SkillsYouNeed:

Learning Skills:

- A - Z List of Learning Skills

- What is Learning?

- Learning Approaches

- Learning Styles

- 8 Types of Learning Styles

- Understanding Your Preferences to Aid Learning

- Lifelong Learning

- Decisions to Make Before Applying to University

- Top Tips for Surviving Student Life

- Living Online: Education and Learning

- 8 Ways to Embrace Technology-Based Learning Approaches

- Critical Thinking Skills

- Understanding and Addressing Conspiracy Theories

- Critical Analysis

- Study Skills

- Exam Skills

- Writing a Dissertation or Thesis

- Research Methods

- Teaching, Coaching, Mentoring and Counselling

- Employability Skills for Graduates

Subscribe to our FREE newsletter and start improving your life in just 5 minutes a day.

You'll get our 5 free 'One Minute Life Skills' and our weekly newsletter.

We'll never share your email address and you can unsubscribe at any time.

Since the 2016 US presidential election, the phrase ‘ fake news ’ has become standard currency. But what does the term actually mean, and how can you distinguish fake from ‘real’ news?

The bad news is that ‘fake news’ is often very believable, and it is extremely easy to get caught out.

This page explains how you can apply critical thinking techniques to news stories to reduce the chances of believing fake news, or at least starting to understand that ‘not everything you read is true’.

What is ‘ Fake News ’?

‘Fake news’ is news stories that are either completely untrue, or do not contain all the truth, with a view to deliberately misleading readers.

Fake news became prominent during the US election, with supporters of both sides tweeting false information in the hope of influencing voters. But it is nothing new.

“The report of my death was an exaggeration.”

In May 1897, Mark Twain, the American author, was in London. Rumours reached the US that he was very ill and, later, that he had died. In a letter to Frank Marshall White, a journalist who inquired after his health as a result, Mark Twain suggested that the rumours had started because his cousin, who shared his surname, had been ill a few weeks before. He noted dryly to White,

“The report of my death was an exaggeration”.

It had, nonetheless, been widely reported in the US, with one newspaper even printing an obituary.

Fake news is not:

Articles on satirical or humorous websites, or related publications, that make a comment on the news by satirising them, because this is intended to inform and amuse, not misinform;

Anything obvious that ‘everyone already knows’ (often described using the caption ‘that’s not news’; or

An article whose content you disagree with.

The deliberate intention of fake news to mislead is crucial.

Why is Fake News a Problem?

If fake news has been around for so long, why is it suddenly a problem?

The answer is that social media means that credible fake news stories can spread very quickly.

In the worst cases, they can have major effects. There are suggestions that fake news influenced the 2016 US election. In another case, a gunman opened fire at a pizzeria that had been falsely but widely reported as being the centre of a paedophile ring involving prominent politicians. In less critical cases, fake news reports can result in distress or reputational damage for the people or organisations mentioned in the articles.

It is, therefore, important to be alert to the potential for reports to be fake, and to ensure that you are not party to their spread.

Spotting fake news

Unfortunately, it is not always easy to spot false news.

Sometimes, a story may be obviously false – for example, it may contain typos or spelling mistakes, or formatting errors. Like phishing emails, however, some fake news stories are a lot more subtle than that.

Facebook famously issued a guide to spotting fake news in May 2017. Its advice ranges from the obvious to the much less intuitive. Useful tips include:

Investigate the source

Be wary of stories written by unknown sources, and check their website for more information. Stories from reliable news sources, such as national newspapers or broadcasters, are more likely to have been checked and verified. It is also worth looking at the URL, to make sure it is a genuine news organisation.

Look at the evidence on which the article bases its claims, and check whether they seem credible. If there are no sources given, or the source is an unknown ‘expert’ or ‘friend’ of someone concerned, be sceptical.

Check whether other, reliable news sources are carrying the story

Sometimes, even otherwise reliable news sources get carried away and forget to do all the necessary checks. But one very good check is to ask whether other reliable sources are also carrying the story. If yes, it is likely to be correct. If not, you should at least be doubtful.

Facebook’s advice boils down to reading news stories critically.

That does not mean looking for their flaws, or criticising them, although this can be part of critical reading and thinking. Instead, it means applying logic and reason to your thinking and reading, so that you make a sensible judgement about what you are reading.

In practice, this means being alert to why the article has been written, and what the author wants you to feel, think or even do as a result of reading it. Even accurate stories may have been written in a way that is designed to steer you towards a particular point of view or action.

For more about this see our pages on Critical Thinking and Critical Reading .

A word about bias

It is worth remembering that everyone has their opinions, and therefore sources of potential bias in what they write. These may be conscious or unconscious. News organisations tend to have an organisational ‘view’ or political slant. For example, the UK’s Guardian is broadly left-wing, and most of the UK tabloids are right-wing in their views, and this affects both what they report and how they report it.

As a reader, you also have biases, both conscious and unconscious, and these affect the stories you choose to read, and the sources you use. It is therefore possible to self-select only stories that confirm your own view of the world, and social media is very good at helping with this.

To overcome this, it is important to use more than one source of information, and try to ensure that they have at least small differences in their political views.

A final thought

Fake news spreads so fast because we all like the idea of telling people something that they did not already know, something exclusive, and because we want to share our view of the world. It’s a bit like gossip.

But like false gossip, fake news can harm. Next time, before you click on ‘share’ or ‘retweet’, just take a moment to think about whether the story that you are spreading is likely to be true or not. Even if you think it is true, consider the possible effect of spreading it. Is it going to hurt anyone if it turns out to be false?

If so, don’t go there, think before you share.

Continue to: Understanding and Addressing Conspiracy Theories Critical Thinking Skills

See also: Making Sense of Financial News Understanding and Interpreting Online Product Reviews Critical Analysis

You have exceeded your limit for simultaneous device logins.

Your current subscription allows you to be actively logged in on up to three (3) devices simultaneously. click on continue below to log out of other sessions and log in on this device., the importance of critical thinking in the age of fake news.

Experts shared advice on how to teach students to analyze information during an S LJ /ISTE webcast on critical thinking in the age of fake news, misinformation, and disinformation.

In today’s complex media environment, students must learn how to identify the source of information, verify it, and analyze how it was designed to make them feel, according to news and information literacy experts.

SLJ and ISTE recently hosted a webcast, Critical Thinking in the Age of Fake News , with panelists Peter Adams, senior vice president of education at the News Literacy Project, Renee DiResta, research manager at Stanford University Internet Observatory, and Jennifer LaGarde, an educator and the co-author of Fact vs. Fiction: Critical Thinking Skills in the Age of Fake News. SLJ ’s editor, news and features, Sarah Bayliss moderated.

“One of the main issues is how do you think critically when there is such a myriad of sources,” DiRosa said. “It’s so hard to even know where your information is coming from.”

DiResta explained the differences between four important terms that are used in academia and research: fake news, misinformation, disinformation, and propaganda.

- Fake news is a term that used to refer to information that was demonstrably false. The term has fallen out of favor since it has become so politicized and is often used to dismiss news that someone just doesn’t like, DiResta said.

- Misinformation refers to information that is inadvertently wrong and not intended to misinform people.

- Disinformation refers to information or the distribution of information that is deliberately incorrect or deceptive and intended to spread a false message.

- Propaganda refers to information with an agenda. It is intended to persuade, and while it is not always false, it contains a lot of cheerleading or an unnecessarily positive spin.

There is a wide range of people now active in the creation and dissemination of information, DiResta said. Disinformation and propaganda are no longer produced only by state government or state media. Now it can also come from terrorist organizations, domestic ideologues, spammers, or people who are economically motivated.

Adams noted that the coronavirus pandemic and recent protests to “reopen” the country have sparked a lot of misinformation. For example, some people have spread false medical information and doctored photos to support conspiratorial claims, he said.

“It’s easy for people to believe that sharing this kind of information can’t hurt,” Adams said. “But it can give them a false confidence that they might not need to take the kinds of precautions that they otherwise would.”

Adams shared four key skills educators can teach students to help them combat misinformation.

- Lateral reading. Verifying information as you read it. This can be done by leaving the site and looking at other sites to make sure the original source is reliable and authentic.

- Critical observation. Using critical thinking to look more carefully at images and think about where those images were taken.

- Reverse image search. A digital investigative technique used to find the original source of photographs. Google has specific tools for this, and other sites such as TinEye and Yandex , also help users with these searches.

- Geolocation. Verifying the location of online information. It involves using Google Street View and other sites to confirm the location of an image.

LaGarde said educators need to start making the connection between news and information literacy and social-emotional learning.

“We have to teach kids that they need to think about how the news and information makes them feel,” she said. “And we need to provide some strategies for navigating that emotional response.”

She also noted that many schools teach kids about news literacy on desktops and laptops, while most people, including students, now access information through their phones. She advised listeners to teach students how to parse information for credibility on phones.

LaGarde also stressed the importance of getting students to think about what motivates someone to create and share information, and she noted that many kids are already creating content on YouTube and Instagram.

“We can harness their interest in creating content to help them think about the choices that content creators make when creating information that is suspect or false,” LaGarde said. “We can help kids get inside the minds of people who create news and information.”

Melanie Kletter is an educator and freelance writer and editor.

Get Print. Get Digital. Get Both!

Libraries are always evolving. Stay ahead. Log In.

Add Comment :-

Comment policy:.

- Be respectful, and do not attack the author, people mentioned in the article, or other commenters. Take on the idea, not the messenger.

- Don't use obscene, profane, or vulgar language.

- Stay on point. Comments that stray from the topic at hand may be deleted.

- Comments may be republished in print, online, or other forms of media.

- If you see something objectionable, please let us know . Once a comment has been flagged, a staff member will investigate.

First Name should not be empty !!!

Last Name should not be empty !!!

email should not be empty !!!

Comment should not be empty !!!

You should check the checkbox.

Please check the reCaptcha

Ethan Smith

Lorem Ipsum is simply dummy text of the printing and typesetting industry. Lorem Ipsum has been the industry's standard dummy text ever since the 1500s, when an unknown printer took a galley of type and scrambled it to make a type specimen book.

Posted 6 hours ago REPLY

Jane Fitgzgerald

Posted 6 hours ago

Michael Woodward

Continue reading.

Added To Cart

Related , early readers to ignite imaginations | read woke, alabama educators earn grant for trip to scotland to spark students’ reading and writing, the practical art of kindness: navigating the world demands it | great books, preschoolers and the science of reading | first steps, school and public librarians describe on-the-job harassment, webcast: found in translation — bringing world storytelling to young readers | december 14, "what is this" design thinking from an lis student.

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, --> Log In

You did not sign in correctly or your account is temporarily disabled

REGISTER FREE to keep reading

If you are already a member, please log in.

Passwords must include at least 8 characters.

Your password must include at least three of these elements: lower case letters, upper case letters, numbers, or special characters.

The email you entered already exists. Please reset your password to gain access to your account.

Create an account password and save time in the future. Get immediate access to:

News, opinion, features, and breaking stories

Exclusive video library and multimedia content

Full, searchable archives of more than 300,000 reviews and thousands of articles

Research reports, data analysis, white papers, and expert opinion

Passwords must include at least 8 characters. Please try your entry again.

Your password must include at least three of these elements: lower case letters, upper case letters, numbers, or special characters. Please try your entry again.

Thank you for registering. To have the latest stories delivered to your inbox, select as many free newsletters as you like below.

No thanks. return to article, already a subscriber log in.

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Thank you for visiting.

We’ve noticed you are using a private browser. To continue, please log in or create an account.

CREATE AN ACCOUNT

SUBSCRIPTION OPTIONS

Already a subscriber log in.

Most SLJ reviews are exclusive to subscribers.

As a subscriber, you'll receive unlimited access to all reviews dating back to 2010.

To access other site content, visit our homepage .

Fake News & Critical Thinking: Critical Thinking

- Critical Thinking

- Finding Real News

What is Critical Thinking?

Think critically about what you read, hear, see, and about how you absorb information. It's a good way to begin figuring out and interpreting fake news, alternative facts, post-truth, and misinformation.

Resources - Articles, Books, & Websites

- Critical Thinking: Where to Begin? from the Foundation for Critical Thinking

- Critical Thinking: Why Is It So Hard to Teach (article) Willingham, D. T. (2008). Critical thinking: why is it so hard to teach? Arts Education Policy Review, 109 (4), 21–29.

- Civic Online Reasoning (COR) A free curriculum developed by the Stanford History Education Group

- Center for News Literacy

- FakeOut Can you spot ‘fake news’? Have fun finding the facts with this social media-emulating game.

Figuring Out Images

With advanced image altering software, images can provide false or misleading information too. Google Reverse Image Search allows users to verify what websites used the image. When viewing images, ask yourself these questions:

- When was the picture taken?

- Where was the picture taken?

- Who took the picture?

- Look closely?

- Why are you seeing this now?

Analyzing News Sources

- Avoid websites that end in “lo” ex: Newslo. These sites take pieces of accurate information and then packaging that information with other false or misleading “facts” (sometimes for the purposes of satire or comedy).

- Watch out for websites that end in “.com.co” as they are often fake versions of real news sources.

- Watch out if known/reputable news sites are not also reporting on the story. Sometimes lack of coverage is the result of corporate media bias and other factors, but there should typically be more than one source reporting on a topic or event.

- Odd domain names generally equal odd and rarely truthful news.

- Lack of author attribution may, but not always, signify that the news story is suspect and requires verification.

- Some news organizations are also letting bloggers post under the banner of particular news brands; however, many of these posts do not go through the same editing process (ex: BuzzFeed Community Posts, Kinja blogs, Forbes blogs).

- Check the “About Us” tab on websites or look up the website on Snopes or Wikipedia for more information about the source.

- Bad web design and use of ALL CAPS can also be a sign that the source you’re looking at should be verified and/or read in conjunction with other sources.

- If the story makes you REALLY ANGRY it’s probably a good idea to keep reading about the topic via other sources to make sure the story you read wasn’t purposefully trying to make you angry (with potentially misleading or false information) in order to generate shares and ad revenue.

- If the website you’re reading encourages you to dox individuals (doxing is searching for and publishing private or identifying information about someone on the Internet, typically with malicious intent), it’s unlikely to be a legitimate source of news.

- It’s always best to read multiple sources of information to get a variety of viewpoints and media frames. Some sources not yet included in this list (although their practices at times may qualify them for addition), such as The Daily Kos, The Huffington Post, and Fox News, vacillate between providing important, legitimate, problematic, and/or hyperbolic news coverage, requiring readers and viewers to verify and contextualize information with other sources.

[from M. Zimbar, False, misleading, clickbait-y, and / or satirical "news" sources. Retrieved from Pace University Library Research Guide . Illustration by Jim Cooke .]

A Word About Search Engines

Search engine creators, like Google, are businesses whose purpose is to turn a profit, not help you find information. Using several different search engines when seeking information is good practice, don't become loyal to just one. In addition, consider using search engines that are uncensored and anonymous, such as, DuckDuckGo or GIBIRU .

- << Previous: So What?

- Next: Finding Real News >>

- Last Updated: Apr 2, 2024 6:52 PM

- URL: https://libguides.su.edu/fake_news

- Reference Manager

- Simple TEXT file

People also looked at

Original research article, “fake news” or real science critical thinking to assess information on covid-19.

- 1 Department of Applied Didactics, Universidade de Santiago de Compostela (USC), Santiago de Compostela, Spain

- 2 IES Ramón Cabanillas, Xunta de Galicia, Cambados, Spain

Few people question the important role of critical thinking in students becoming active citizens; however, the way science is taught in schools continues to be more oriented toward “what to think” rather than “how to think.” Researchers understand critical thinking as a tool and a higher-order thinking skill necessary for being an active citizen when dealing with socio-scientific information and making decisions that affect human life, which the pandemic of COVID-19 provides many opportunities for. The outbreak of COVID-19 has been accompanied by what the World Health Organization (WHO) has described as a “massive infodemic.” Fake news covering all aspects of the pandemic spread rapidly through social media, creating confusion and disinformation. This paper reports on an empirical study carried out during the lockdown in Spain (March–May 2020) with a group of secondary students ( N = 20) engaged in diverse online activities that required them to practice critical thinking and argumentation for dealing with coronavirus information and disinformation. The main goal is to examine students’ competence at engaging in argumentation as critical assessment in this context. Discourse analysis allows for the exploration of the arguments and criteria applied by students to assess COVID-19 news headlines. The results show that participants were capable of identifying true and false headlines and assessing the credibility of headlines by appealing to different criteria, although most arguments were coded as needing only a basic epistemic level of assessment, and only a few appealed to the criterion of scientific procedure when assessing the headlines.

Introduction: Critical Thinking for Social Responsibility – An Urgent Need in the Covid-19 Pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic is a global phenomenon that affects almost all spheres of our life, aside from its obvious direct impacts on human health and well-being. As mentioned by the UN Secretary General, in his call for solidarity, “We are facing a global health crisis unlike any in the 75-year history of the United Nations — one that is spreading human suffering, infecting the global economy and upending people’s lives.” (19 March 2020, Guterres, 2020 ). COVID-19 has revealed the vulnerability of global systems’ abilities to protect the environment, health and economy, making it urgent to provide a responsible response that involves collaboration between diverse social actors. For science education the pandemic has raised new and unthinkable challenges ( Dillon and Avraamidou, 2020 ; Jiménez-Aleixandre and Puig, 2021 ), which highlight the importance of critical thinking (CT) development in promoting responsible actions and responses to the coronavirus disease, which is the focus of this paper. Despite the general public’s respect of science and scientific advances, denial movements – such as the ones that reject the use of vaccines and advocate for alternative health therapies – are increasing during this period ( Dillon and Avraamidou, 2020 ). The rapid global spread of the coronavirus disease has been accompanied by what the World Health Organization (WHO) has described as the COVID-19 social media infodemic. The term infodemic refers to an overabundance of information (real or not) associated with a specific topic, whose growth can occur exponentially in a short period of time [ World Health Organization (WHO), 2020 ]. The case of the COVID-19 pandemic shows the crucial importance of socio-scientific instruction toward students’ development of critical thinking (CT) for citizenship.

Critical thinking is embedded within the framework of “21st century skills” and is considered one of the goals of education ( van Gelder, 2005 ). Despite its importance, there is not a clear consensus on how to better promote CT in science instruction, and teachers often find it unclear what CT means and requires from them in their teaching practice ( Vincent-Lacrin et al., 2019 ). CT is understood in this study as a set of skills and dispositions that enable students and people to take critical actions based on reasons and values, but also as independent thinking ( Jiménez-Aleixandre and Puig, 2021 ). It is also considered as a dialogic practice that students can enact and thereby become predisposed to practice ( Kuhn, 2019 ). We consider that CT has two fundamental roles in SSI instruction: one role linked to the promotion of rational arguments, cognitive skills and dispositions; and the other related to the idea of critical action and social activism, which is consistent with the characterization of CT provided by Jiménez-Aleixandre and Puig (2021) . Although research on SSIs has provided us with empirical evidence supporting the benefits of SSI instruction, particularly argumentation and students’ motivation toward learning science, there is still scarce knowledge on how CT is articulated in these contexts. One challenge with promoting CT, especially in SSIs, is linked to new forms of communication that generate a rapid increase of information and easy access to it ( Puig et al., 2020 ).

The study was developed in an unprecedented scenario, during the lockdown in Spain (March–May 2020), which forced the change of face-to-face teaching to virtual teaching, involving students in online activities that embraced the application of scientific notions related to COVID-19 and CT for assessing claims published in news headlines related to it. Previous studies have pointed out the benefits of virtual environments to foster CT among students, particularly asynchronous discussions that minimize social presence and favor all students expressing their own opinion ( Puig et al., 2020 ).

In this research, we aim to explore students’ ability to critically engage in the assessment of the credibility of COVID-19 claims during a moment in which fake news disseminated by social media was shared by the general public and disinformation on the virus was easier to access than real news.

Theoretical Framework

We will first discuss the crucial role of CT to address controversial issues and to fight against the rise of misinformation on COVID-19; and then turn attention to the role of argumentation in students’ development of CT in SSI instruction in epistemic education.

Critical Thinking on Socio-Scientific Instruction to Face the Rise of Disinformation

SSIs are compelling issues for the application of knowledge and processes contributing to the development of CT. They are multifaceted problems, as is the case of COVID-19, that involve informal reasoning and elements of critique where decisions present direct consequences to the well-being of human society and the environment ( Jiménez-Aleixandre and Puig, 2021 ). People need to balance subject matter knowledge, personal values, and societal norms when making decisions on SSIs ( Aikenhead, 1985 ) but they also have to be critical of the discourses that shape their own beliefs and practices to act responsibly ( Bencze et al., 2020 ). According to Duschl (2020) , science education should involve the creation of a dialogic discourse among members of a class that focuses on the teaching and learning of “how did we come to know?” and “why do we accept that knowledge over alternatives?” Studies on SSIs during the last decades have pointed out students’ difficulties in building arguments and making critical choices based on evidence ( Evagorou et al., 2012 ). However, literature also indicates that students find SSIs motivational for learning and increase their community involvement ( Eastwood et al., 2012 ; Evagorou, 2020 ), thus they are appropriate contexts for CT development. While research on content knowledge and different modes of reasoning on SSIs is extensive, the practice of CT is understudied in science instruction. Of particular interest in science education are SSIs that involve health controversies, since they include some of the challenges posed by the post-truth era, as the health crisis produced by coronavirus shows. The COVID-19 pandemic is affecting most countries and territories around the world, which is why it is considered the greatest challenge that humankind has faced since the 2nd World War ( Chakraborty and Maity, 2020 ). Issues like COVID-19 that affect society in multiple ways require literate citizens who are capable of making critical decisions and taking actions based on reasons. As the world responds to the COVID-19 pandemic, we face the challenge of an overabundance of information related to the virus. Some of this information may be false and potentially harmful [ World Health Organization (WHO), 2020 ]. In the context of growing disinformation related to the COVID-19 outbreak, EU institutions have worked to raise awareness of the dangers of disinformation and promoted the use of authoritative sources ( European Council of the European Union, 2020 ). Educators and science educators have been increasingly concerned with what can be done in science instruction to face the spread of misinformation and denial of well-established claims; helping students to identify what is true can be a hard task ( Barzilai and Chinn, 2020 ). As these authors suggest, diverse factors may shape what people perceive as true, such as the socio-cultural context in which people live, their personal experiences and their own judgments, that could be biased. We concur with these authors and Feinstein and Waddington (2020) , who argue that science education should not focus on achieving the knowledge, but rather on gaining appropriate scientific knowledge and skills, which in our view involves CT development. Furthermore, according to Sperber et al. (2010) , there are factors that affect the acceptance or rejection of a piece of information. These factors have to do either with the source of the information – “who to believe” – or with its content – “what to believe.” The pursuit of truth when dealing with SSIs can be facilitated by the social practices used to develop knowledge ( Duschl, 2020 ), such as argumentation understood as the evaluation of claims based on evidence, which is part of CT development.

We consider CT and argumentation as overlapping competencies in their contexts of practice; for instance, when assessing claims on COVID-19, as in this study. According to Sperber et al. (2010) , we now have almost no filters on information, and this requires a much more vigilant, knowledgeable reader. As these authors point out, individuals need to become aware of their own cognitive biases and how to avoid being victims themselves. If we want students to learn how to critically evaluate the information and claims they will encounter in social media outside the classroom, we need to engage them in the practice of argumentation and CT. This raises the question of what type of information is easier or harder for students to assess, especially when they are directly affected by the problem. In this paper we aim to explore this issue by exploring students’ arguments while assessing diverse claims on COVID-19. We think that students’ arguments reflect their ability to apply CT in this context, although this does not mean that CT skills always produce a well-reasoned argument ( Halpern, 1998 ). Students should be encouraged to express their own thoughts in SSI instruction, but also to support their views reasonably ( Puig and Ageitos, 2021 ). Specifically, when they must assess the validity of information that affects not only them as individuals but also the whole society and environment. CT may equip citizens to discard fake news and to use appropriate criteria to evaluate information. This requires the design and implementation of specific CT tasks, as this study presents.

Argumentation to Enhance Critical Thinking Development in Epistemic Education on SSIs

While the concept of CT has a long tradition and educators agree on its importance, there is a lack of agreement on what this notion involves ( Thomas and Lok, 2015 ). CT has been used with a wide range of meanings in theoretical literature ( Facione, 1990 ; Ennis, 2018 ). In 1990, The American Philosophical Association convened an authoritative panel of forty-six noted experts on CT to produce a definitive account of the concept, which was published in the Delphi Report ( Facione, 1990 ). The Delphi definition provides a list of skills and dispositions that can be useful and guide CT instruction. However, as Davies and Barnett (2015) point out, this Delphi definition does not include the phenomenon of action. We concur with these authors that CT education should involve students in “CT for action,” since decision making – a way of deciding on a course of action – is based on judgments derived from argumentation using CT. Drawing from Halpern (1998) , we also think that CT requires awareness of one’s own knowledge. CT requires, for instance, insight into what one knows and the extent and importance of what one does not know in order to assess socio-scientific news and its implications ( Puig and Ageitos, 2021 ).

Critical thinking and argumentation share core elements like rationality and reflection ( Andrews, 2015 ). Some researchers suggest understanding CT as a dialogic practice ( Kuhn, 2019 ) has implications in CT instruction and development. Argumentation on SSIs, particularly on health controversies, is receiving increasing attention in science education in the post-truth era, as the coronavirus pandemic and denial movements related to its origin, prevention, and treatment show. Science education should involve the creation of a dialogic discourse among members of a class that enable them to develop CT. One of the central features in argumentation is the development of epistemic criteria for knowledge evaluation ( Jiménez Aleixandre and Erduran, 2008 ), which is a necessary skill to be a critical thinker. We see the practice of CT as the articulation of cognitive skills through the practice of argumentation ( Giri and Paily, 2020 ).

This article argues that science education needs to explore learning experiences and ways of instruction that support CT by engaging learners in argumentation on SSIs. Despite CT being considered a seminal goal in education and the large body of research on CT supporting this ( Dominguez, 2018 ), debates still persist about the manner in which CT skills can be achieved through education ( Abrami et al., 2008 ). Niu et al. (2013) remark that educators have made a striking effort to foster CT among students, showing that the belief that CT can be taught and learned has spread and gained support. Therefore, CT has slowly made its way into general school education and specific instructional interventions. Problem-based learning is one of the most widely used learning approaches nowadays in CT instruction ( Dominguez, 2018 ) because it is motivating, challenging, and enjoyable ( Pithers and Soden, 2000 ; Niu et al., 2013 ). We see active learning methodologies and real-word problems such as SSIs as appropriate contexts for CT development.

The view that CT can be developed by engagement in argumentation practices plays a central role in this study, as Kuhn (2019) suggested. However, the post-truth condition poses some challenges to the evaluation of sources of information and scientific evidence disseminated by social media. According to Sinatra and Lombardi (2020) , the post-truth context raises the need for critical evaluation of online information about SSIs. Students need to be better prepared to assess science information they can easily find online from a variety of sources. Previous studies described by these authors emphasized the importance of source evaluation instruction to equip students toward this goal ( Bråten et al., 2019 ), however, this is not sufficient. Sinatra and Lombardi (2020) note that students should learn how to evaluate the connections between sources of information and knowledge claims. This requires, from our view, engaging students in CT and epistemic performance. If we want students to learn to think critically about the claims they will encounter on social media, they need to practice argumentation as critical evaluation.

We draw on research on epistemic education ( Chinn et al., 2018 ) which considers that learning science entails students’ participation in the science epistemic goals ( Kelly and Licona, 2018 ); in other words, placing scientific practices at the center of SSI instruction. Our study is framed in a broader research project that aims to embed CT in epistemic design and performance. In Chinn et al. (2018) AIR model, epistemic cognition has three core elements that represent the three letters of the acronym: epistemic Aims, goals related to inquiry; epistemic Ideals, standards and criteria used to evaluate epistemic products, such as explanations or arguments; and Reliable processes for attaining epistemic achievements. Of particular interest for our focus on CT is that the AIR model also proposes that epistemic cognition has a social nature, and it is situated. The purpose of epistemic education ( Barzilai and Chinn, 2017 ) should be to enable students to succeed in epistemic activities ( apt epistemic performance ), such as constructing and evaluating arguments, and to assess through meta-competence when success can be achieved. This paper attends to one aspect of epistemic performance proposed by Barzilai and Chinn (2017) , which is cognitive engagement in epistemic assessment. Epistemic assessment encompasses in our study the evaluation of the content of claims disseminated by media. Aligned with these authors we understand that this process requires cognitive and metacognitive competences. Thus, epistemic assessment needs adequate disciplinary knowledge, but also meta-cognitive competence for recognizing unsupported beliefs.

Goal and Research Questions

This paper examines students’ competence to engage in argumentation and CT in an online task that requires them to critically assess diverse information presented in media headlines on COVID-19. Competence in general can be defined as “a disposition to succeed with a certain aim” ( Sosa, 2015 , p. 43) and epistemic competence, as a special case of competence, is at its core a dispositional ability to discern the true from the false in a certain domain. For the purposes of this paper, the attention is on epistemic competence, being the research questions that drive the analysis of the following:

1. What is the competence of students to assess the credibility of COVID-19 information appearing in news headlines?

2. What is the level of epistemic assessment showed in students’ arguments according to the criteria appealed while assessing COVID-19 news headlines?

Materials and Methods

Context, participants, and design.

A teaching sequence about COVID-19 was designed at the beginning of the lockdown in Spain (Mid-March 2020) in response to the rise of misinformation about coronavirus on the internet and social media. The design process involved collaboration between the first and second author (researchers in science education) and the third author (a biology teacher in secondary education).

The participants are a group of twenty secondary students (14–15 years old), eleven of them girls, from a state public school located in a well-known seaside village in Galicia (Spain). They were mostly from middle-class families and within an average range of ability and academic achievement.

Students were from the same classroom and participated in previous online activities as part of their biology classes, taught by their biology teacher, who collaborated on previous studies on CT and learning science through epistemic practices on health controversies.

The activities were integrated in their biology curriculum and carried out when participants received instruction on the topics of health, infectious diseases, and the immune system.

Google Forms was used for the design and implementation of all activities included in the sequence. The reason to select Google Forms is that it is free and a well-known tool for online surveys. Besides, all students were familiar with its use before the lockdown and the teacher valued its usefulness for engaging them in online debates and in their own evaluation processes. This online resource provides anonymous results and statistics that the teacher could share with the students for debates. It needs to be highlighted that during the lockdown students did not have the same work conditions; particularly, quality and availability of access to the internet differed among them. Thus, all activities were asynchronous. They had 1 week to complete each task and the teacher could be consulted anytime if they had difficulties or any question regarding the activities.

The design was inspired by a previous one carried out by the authors when the first case of Ebola disease was introduced in Spain ( Puig et al., 2016 ), and follows a constructivist and scientific-based approach. The sequence began with an initial task, in which students were required to express their own views and knowledge on COVID-19 and health notions related with it, before then being progressively involved in the application of knowledge through the practice of modeling and argumentation. The third activity engaged them in critical evaluation of COVID-19 information. A more detailed description of the activities carried out in the different steps of the sequence is provided below.

Stage 1: General Knowledge on Health Notions Related to COVID-19

An individual Google Forms survey around some notions and health concepts that appear in social media during the lockdown, such as “pandemic”, “virus,” etc.

Stage 2: Previous Knowledge on Coronavirus Disease

This stage consisted of three parts: (2.1) Individual online survey on infectious diseases; (2.2) Introduction of knowledge about infectious diseases provided in the e-bugs project website 1 and activities; virtual visit to the exhibition “Outbreaks: epidemics in a connected world” available in the Natural History Museum website (blinded for review); (2.3) Building a poster with the chain of infection of the COVID-19 disease and some relevant information to consider in order to stop the spread of the disease.

Stage 3: COVID-19, Sources of Information

This stage consisted first of a virtual forum in which students shared their own habits when consulting scientific information, particularly coronavirus-related, and debated on the main media sources they used to consult for this purpose. Secondly, students had to analyze ten news headlines on COVID-19 disseminated by social media during the outbreaks; six corresponded to fake news and four were true. They were asked to critically assess them and distinguish which they thought were true, providing their arguments. Media sources were not provided until the end of the task, since the act of asking for the source was considered as part of the data analysis (see Table 1 ). The second part of this stage is the focus of our analysis.

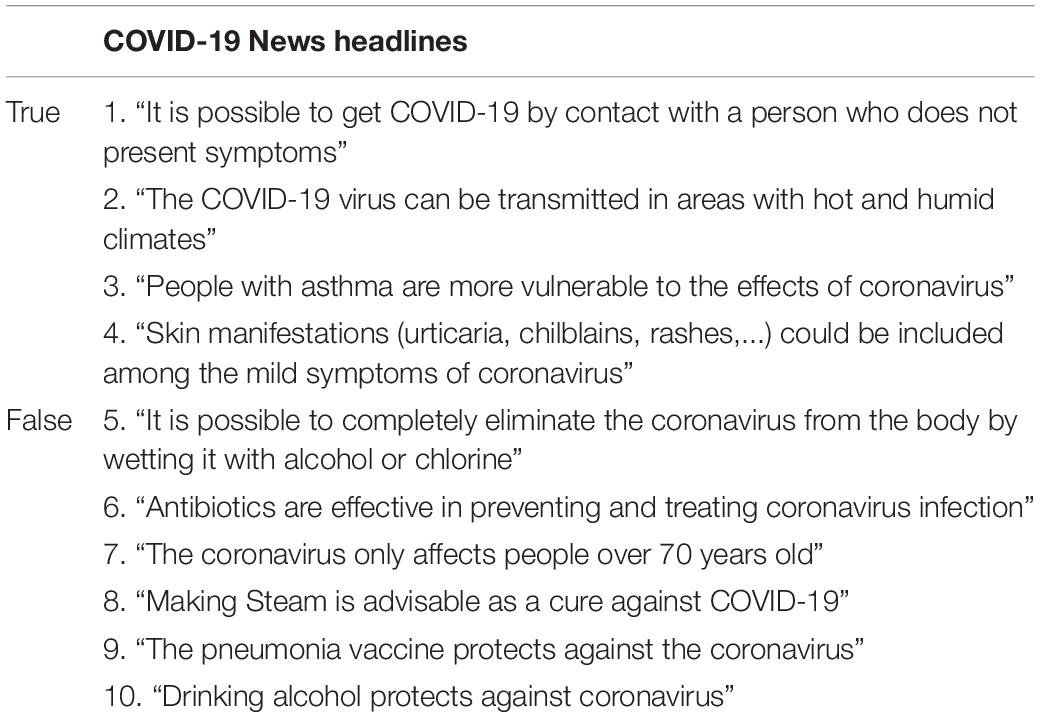

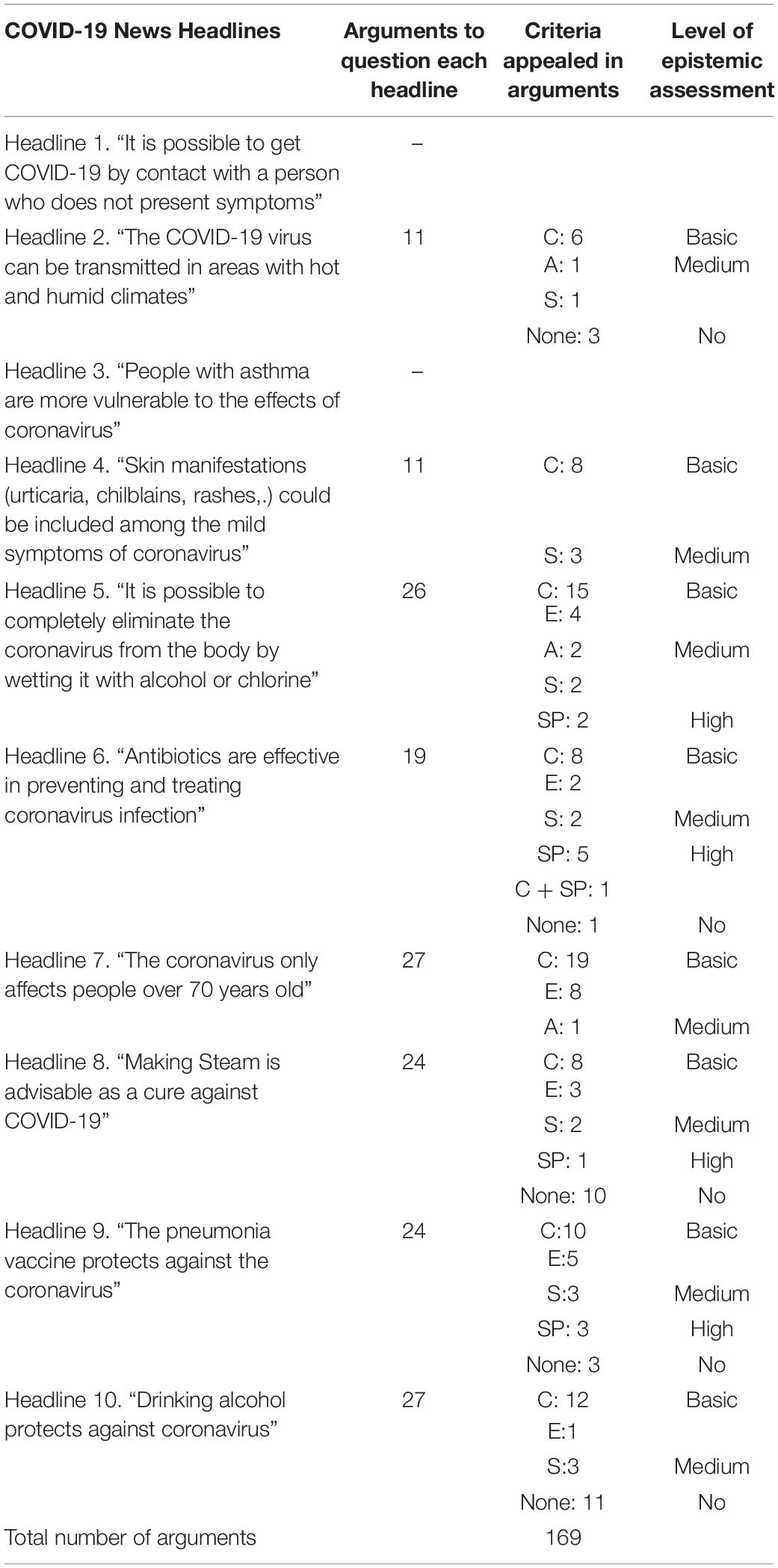

Table 1. COVID-19 News Headlines provided to students.

Stage 4: Act and Raise Awareness on COVID-19

The sequence ended with the creation of a short video in which the students had to provide some tips to avoid the transmission of the virus. The information provided in the video must be supported and based on established scientific knowledge.

Data Corpus and Analysis

Data collection includes all individual surveys and activities developed in Google Forms. We analyzed students’ individual responses ( N = 28) presented in Stage 3. The research is designed as a qualitative study that utilizes the methods of discourse analysis in accordance with the data and the purpose of the study. Discourse analysis allows the analysis of the content (implicit or explicit) of written arguments produced by students, and so the examination of the research questions. Our analysis focuses on students’ arguments and criteria used to assess the credibility of COVID-19 headlines (ten headlines in total). It was carried out through an iterative process in which students’ responses were read and revised several times in order to develop an open-coded scheme that captures the arguments provided. To ensure the internal reliability of our codes, each student response was examined by the first and the second author separately and then contrasted and discussed until 100% agreement was achieved. The codes obtained were established according to the following criteria, summarized in Table 2 .

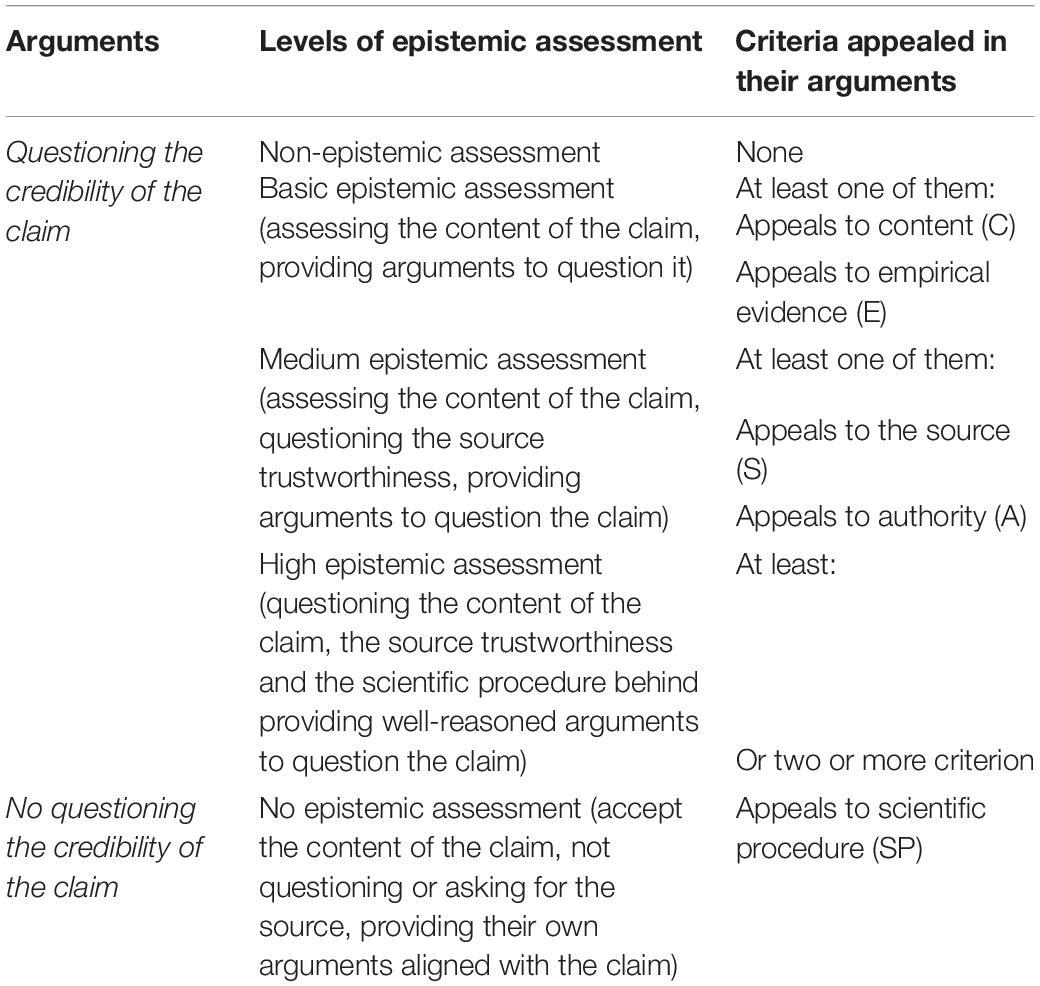

Table 2. Code scheme for research questions 1 and 2.

For Research Question 1, we distributed the arguments in two main categories: (1) Arguments that question the credibility of the information ; (2) Arguments that do not question the credibility of the information.

For Research Question 2, we classify arguments that question the credibility of the headline in accordance with the level of epistemic assessment into three levels (see Table 2 ). The level of epistemic assessment (basic, medium, and high) was established by the authors based on the criteria that students applied and expressed explicitly or implicitly in their arguments. These criteria emerged from the data, thus the categories were not pre-established; they were coded by the authors as the following: content (using the knowledge that each student has about the topic), source (questioning the origin of the information), evidence (appealing to empirical evidence as real live situations that students experienced), authority (justifying according to who supports or is behind the claim) and scientific procedure (drawing on the evolution of scientific knowledge).

Students’ Competence to Critically Assess the Credibility of COVID-19 Claims

In general, most students were able to distinguish fallacious from true headlines, which was an important step to assess their credibility. For those that were false, students were able to question their credibility, providing arguments against them. On the contrary, for true news headlines, as it was expected, most participants developed arguments supporting them. Thus, they did not question their content. In both cases, the arguments elaborated by students appealed to different criteria discussed in the next section of results.

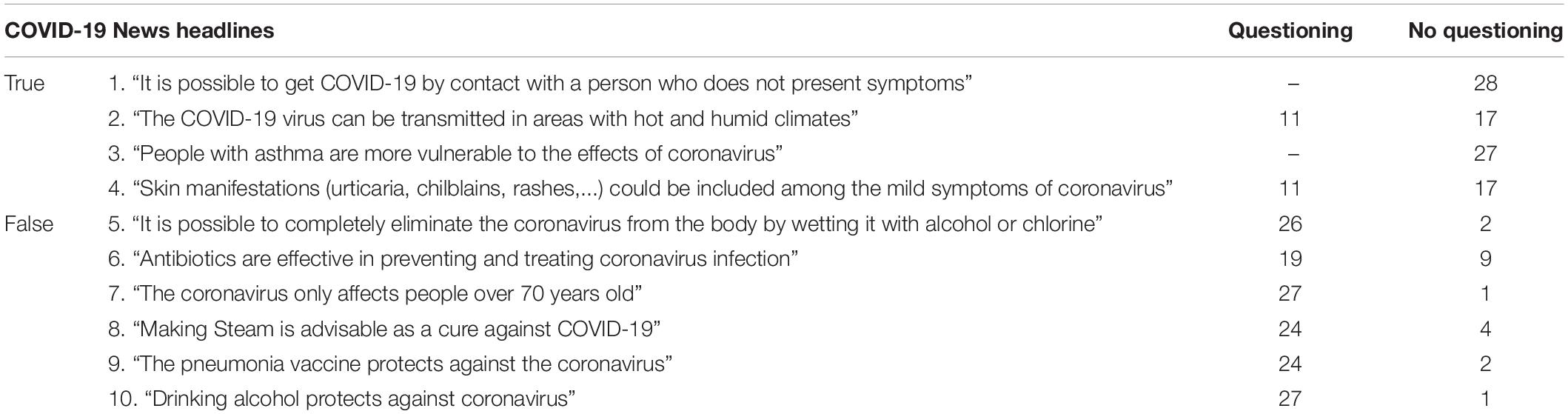

As shown in Table 3 , 147 arguments were elaborated by students to question the false headlines; they created just 22 arguments to assess the true ones. This finding was expected by the authors, as arguments for questioning or criticality appear more frequently when the information presented differs from students’ opinions.

Table 3. Number of students who questioned or not each news headline on COVID-19.

Students showed a higher capacity for questioning those claims they considered false or fake news , which can be related to the need to justify properly why they consider them false and/or what should be said to counter them.

The headlines that were most controversial, meaning they created diverse positions among students, were these three: “The COVID-19 virus can be transmitted in areas with hot and humid climates,” “Skin manifestations (urticaria, chilblains, rashes…) could be among the mild symptoms of coronavirus” and “Antibiotics are effective in preventing and treating coronavirus infection.”

The first two were questioned by 11 students out of 28, despite being real headlines. According to students’ answers, they were not familiar with this information, e.g., “I think the heat is not good for the virus.” On the contrary, 17 students did not question these headlines, arguing for instance as this student did: “because it was shown that both in hot climates and in cold climates it is contagious in the same way.”