2.1 Why Is Research Important?

Learning objectives.

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Explain how scientific research addresses questions about behavior

- Discuss how scientific research guides public policy

- Appreciate how scientific research can be important in making personal decisions

Scientific research is a critical tool for successfully navigating our complex world. Without it, we would be forced to rely solely on intuition, other people’s authority, and blind luck. While many of us feel confident in our abilities to decipher and interact with the world around us, history is filled with examples of how very wrong we can be when we fail to recognize the need for evidence in supporting claims. At various times in history, we would have been certain that the sun revolved around a flat earth, that the earth’s continents did not move, and that mental illness was caused by possession ( Figure 2.2 ). It is through systematic scientific research that we divest ourselves of our preconceived notions and superstitions and gain an objective understanding of ourselves and our world.

The goal of all scientists is to better understand the world around them. Psychologists focus their attention on understanding behavior, as well as the cognitive (mental) and physiological (body) processes that underlie behavior. In contrast to other methods that people use to understand the behavior of others, such as intuition and personal experience, the hallmark of scientific research is that there is evidence to support a claim. Scientific knowledge is empirical : It is grounded in objective, tangible evidence that can be observed time and time again, regardless of who is observing.

While behavior is observable, the mind is not. If someone is crying, we can see behavior. However, the reason for the behavior is more difficult to determine. Is the person crying due to being sad, in pain, or happy? Sometimes we can learn the reason for someone’s behavior by simply asking a question, like “Why are you crying?” However, there are situations in which an individual is either uncomfortable or unwilling to answer the question honestly, or is incapable of answering. For example, infants would not be able to explain why they are crying. In such circumstances, the psychologist must be creative in finding ways to better understand behavior. This chapter explores how scientific knowledge is generated, and how important that knowledge is in forming decisions in our personal lives and in the public domain.

Use of Research Information

Trying to determine which theories are and are not accepted by the scientific community can be difficult, especially in an area of research as broad as psychology. More than ever before, we have an incredible amount of information at our fingertips, and a simple internet search on any given research topic might result in a number of contradictory studies. In these cases, we are witnessing the scientific community going through the process of reaching a consensus, and it could be quite some time before a consensus emerges. For example, the explosion in our use of technology has led researchers to question whether this ultimately helps or hinders us. The use and implementation of technology in educational settings has become widespread over the last few decades. Researchers are coming to different conclusions regarding the use of technology. To illustrate this point, a study investigating a smartphone app targeting surgery residents (graduate students in surgery training) found that the use of this app can increase student engagement and raise test scores (Shaw & Tan, 2015). Conversely, another study found that the use of technology in undergraduate student populations had negative impacts on sleep, communication, and time management skills (Massimini & Peterson, 2009). Until sufficient amounts of research have been conducted, there will be no clear consensus on the effects that technology has on a student's acquisition of knowledge, study skills, and mental health.

In the meantime, we should strive to think critically about the information we encounter by exercising a degree of healthy skepticism. When someone makes a claim, we should examine the claim from a number of different perspectives: what is the expertise of the person making the claim, what might they gain if the claim is valid, does the claim seem justified given the evidence, and what do other researchers think of the claim? This is especially important when we consider how much information in advertising campaigns and on the internet claims to be based on “scientific evidence” when in actuality it is a belief or perspective of just a few individuals trying to sell a product or draw attention to their perspectives.

We should be informed consumers of the information made available to us because decisions based on this information have significant consequences. One such consequence can be seen in politics and public policy. Imagine that you have been elected as the governor of your state. One of your responsibilities is to manage the state budget and determine how to best spend your constituents’ tax dollars. As the new governor, you need to decide whether to continue funding early intervention programs. These programs are designed to help children who come from low-income backgrounds, have special needs, or face other disadvantages. These programs may involve providing a wide variety of services to maximize the children's development and position them for optimal levels of success in school and later in life (Blann, 2005). While such programs sound appealing, you would want to be sure that they also proved effective before investing additional money in these programs. Fortunately, psychologists and other scientists have conducted vast amounts of research on such programs and, in general, the programs are found to be effective (Neil & Christensen, 2009; Peters-Scheffer, Didden, Korzilius, & Sturmey, 2011). While not all programs are equally effective, and the short-term effects of many such programs are more pronounced, there is reason to believe that many of these programs produce long-term benefits for participants (Barnett, 2011). If you are committed to being a good steward of taxpayer money, you would want to look at research. Which programs are most effective? What characteristics of these programs make them effective? Which programs promote the best outcomes? After examining the research, you would be best equipped to make decisions about which programs to fund.

Link to Learning

Watch this video about early childhood program effectiveness to learn how scientists evaluate effectiveness and how best to invest money into programs that are most effective.

Ultimately, it is not just politicians who can benefit from using research in guiding their decisions. We all might look to research from time to time when making decisions in our lives. Imagine that your sister, Maria, expresses concern about her two-year-old child, Umberto. Umberto does not speak as much or as clearly as the other children in his daycare or others in the family. Umberto's pediatrician undertakes some screening and recommends an evaluation by a speech pathologist, but does not refer Maria to any other specialists. Maria is concerned that Umberto's speech delays are signs of a developmental disorder, but Umberto's pediatrician does not; she sees indications of differences in Umberto's jaw and facial muscles. Hearing this, you do some internet searches, but you are overwhelmed by the breadth of information and the wide array of sources. You see blog posts, top-ten lists, advertisements from healthcare providers, and recommendations from several advocacy organizations. Why are there so many sites? Which are based in research, and which are not?

In the end, research is what makes the difference between facts and opinions. Facts are observable realities, and opinions are personal judgments, conclusions, or attitudes that may or may not be accurate. In the scientific community, facts can be established only using evidence collected through empirical research.

NOTABLE RESEARCHERS

Psychological research has a long history involving important figures from diverse backgrounds. While the introductory chapter discussed several researchers who made significant contributions to the discipline, there are many more individuals who deserve attention in considering how psychology has advanced as a science through their work ( Figure 2.3 ). For instance, Margaret Floy Washburn (1871–1939) was the first woman to earn a PhD in psychology. Her research focused on animal behavior and cognition (Margaret Floy Washburn, PhD, n.d.). Mary Whiton Calkins (1863–1930) was a preeminent first-generation American psychologist who opposed the behaviorist movement, conducted significant research into memory, and established one of the earliest experimental psychology labs in the United States (Mary Whiton Calkins, n.d.).

Francis Sumner (1895–1954) was the first African American to receive a PhD in psychology in 1920. His dissertation focused on issues related to psychoanalysis. Sumner also had research interests in racial bias and educational justice. Sumner was one of the founders of Howard University’s department of psychology, and because of his accomplishments, he is sometimes referred to as the “Father of Black Psychology.” Thirteen years later, Inez Beverly Prosser (1895–1934) became the first African American woman to receive a PhD in psychology. Prosser’s research highlighted issues related to education in segregated versus integrated schools, and ultimately, her work was very influential in the hallmark Brown v. Board of Education Supreme Court ruling that segregation of public schools was unconstitutional (Ethnicity and Health in America Series: Featured Psychologists, n.d.).

Although the establishment of psychology’s scientific roots occurred first in Europe and the United States, it did not take much time until researchers from around the world began to establish their own laboratories and research programs. For example, some of the first experimental psychology laboratories in South America were founded by Horatio Piñero (1869–1919) at two institutions in Buenos Aires, Argentina (Godoy & Brussino, 2010). In India, Gunamudian David Boaz (1908–1965) and Narendra Nath Sen Gupta (1889–1944) established the first independent departments of psychology at the University of Madras and the University of Calcutta, respectively. These developments provided an opportunity for Indian researchers to make important contributions to the field (Gunamudian David Boaz, n.d.; Narendra Nath Sen Gupta, n.d.).

When the American Psychological Association (APA) was first founded in 1892, all of the members were White males (Women and Minorities in Psychology, n.d.). However, by 1905, Mary Whiton Calkins was elected as the first female president of the APA, and by 1946, nearly one-quarter of American psychologists were female. Psychology became a popular degree option for students enrolled in the nation’s historically Black higher education institutions, increasing the number of Black Americans who went on to become psychologists. Given demographic shifts occurring in the United States and increased access to higher educational opportunities among historically underrepresented populations, there is reason to hope that the diversity of the field will increasingly match the larger population, and that the research contributions made by the psychologists of the future will better serve people of all backgrounds (Women and Minorities in Psychology, n.d.).

The Process of Scientific Research

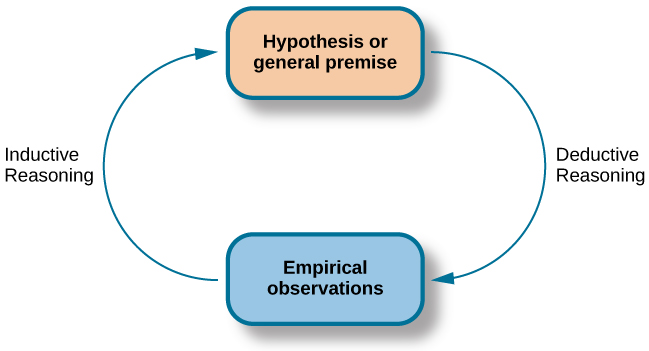

Scientific knowledge is advanced through a process known as the scientific method . Basically, ideas (in the form of theories and hypotheses) are tested against the real world (in the form of empirical observations), and those empirical observations lead to more ideas that are tested against the real world, and so on. In this sense, the scientific process is circular. The types of reasoning within the circle are called deductive and inductive. In deductive reasoning , ideas are tested in the real world; in inductive reasoning , real-world observations lead to new ideas ( Figure 2.4 ). These processes are inseparable, like inhaling and exhaling, but different research approaches place different emphasis on the deductive and inductive aspects.

In the scientific context, deductive reasoning begins with a generalization—one hypothesis—that is then used to reach logical conclusions about the real world. If the hypothesis is correct, then the logical conclusions reached through deductive reasoning should also be correct. A deductive reasoning argument might go something like this: All living things require energy to survive (this would be your hypothesis). Ducks are living things. Therefore, ducks require energy to survive (logical conclusion). In this example, the hypothesis is correct; therefore, the conclusion is correct as well. Sometimes, however, an incorrect hypothesis may lead to a logical but incorrect conclusion. Consider this argument: all ducks are born with the ability to see. Quackers is a duck. Therefore, Quackers was born with the ability to see. Scientists use deductive reasoning to empirically test their hypotheses. Returning to the example of the ducks, researchers might design a study to test the hypothesis that if all living things require energy to survive, then ducks will be found to require energy to survive.

Deductive reasoning starts with a generalization that is tested against real-world observations; however, inductive reasoning moves in the opposite direction. Inductive reasoning uses empirical observations to construct broad generalizations. Unlike deductive reasoning, conclusions drawn from inductive reasoning may or may not be correct, regardless of the observations on which they are based. For instance, you may notice that your favorite fruits—apples, bananas, and oranges—all grow on trees; therefore, you assume that all fruit must grow on trees. This would be an example of inductive reasoning, and, clearly, the existence of strawberries, blueberries, and kiwi demonstrate that this generalization is not correct despite it being based on a number of direct observations. Scientists use inductive reasoning to formulate theories, which in turn generate hypotheses that are tested with deductive reasoning. In the end, science involves both deductive and inductive processes.

For example, case studies, which you will read about in the next section, are heavily weighted on the side of empirical observations. Thus, case studies are closely associated with inductive processes as researchers gather massive amounts of observations and seek interesting patterns (new ideas) in the data. Experimental research, on the other hand, puts great emphasis on deductive reasoning.

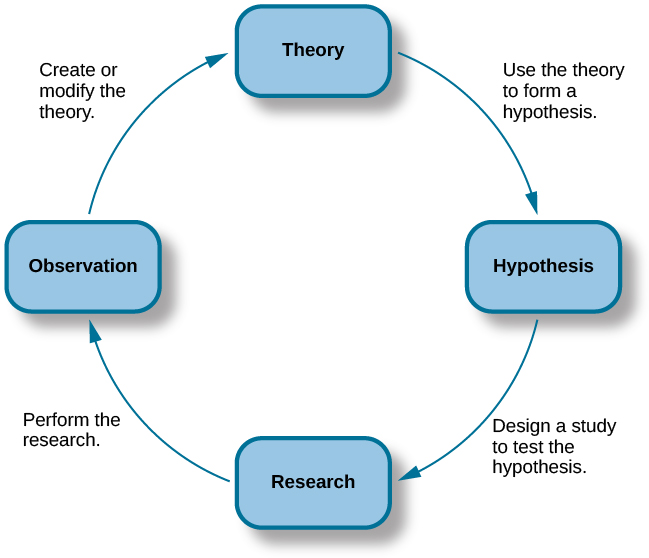

We’ve stated that theories and hypotheses are ideas, but what sort of ideas are they, exactly? A theory is a well-developed set of ideas that propose an explanation for observed phenomena. Theories are repeatedly checked against the world, but they tend to be too complex to be tested all at once; instead, researchers create hypotheses to test specific aspects of a theory.

A hypothesis is a testable prediction about how the world will behave if our idea is correct, and it is often worded as an if-then statement (e.g., if I study all night, I will get a passing grade on the test). The hypothesis is extremely important because it bridges the gap between the realm of ideas and the real world. As specific hypotheses are tested, theories are modified and refined to reflect and incorporate the result of these tests Figure 2.5 .

To see how this process works, let’s consider a specific theory and a hypothesis that might be generated from that theory. As you’ll learn in a later chapter, the James-Lange theory of emotion asserts that emotional experience relies on the physiological arousal associated with the emotional state. If you walked out of your home and discovered a very aggressive snake waiting on your doorstep, your heart would begin to race and your stomach churn. According to the James-Lange theory, these physiological changes would result in your feeling of fear. A hypothesis that could be derived from this theory might be that a person who is unaware of the physiological arousal that the sight of the snake elicits will not feel fear.

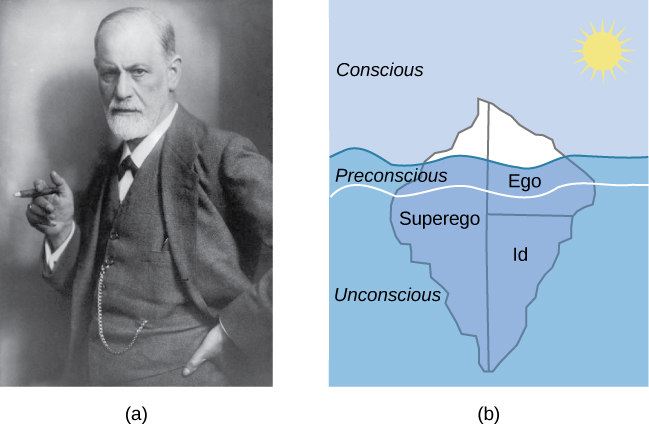

A scientific hypothesis is also falsifiable , or capable of being shown to be incorrect. Recall from the introductory chapter that Sigmund Freud had lots of interesting ideas to explain various human behaviors ( Figure 2.6 ). However, a major criticism of Freud’s theories is that many of his ideas are not falsifiable; for example, it is impossible to imagine empirical observations that would disprove the existence of the id, the ego, and the superego—the three elements of personality described in Freud’s theories. Despite this, Freud’s theories are widely taught in introductory psychology texts because of their historical significance for personality psychology and psychotherapy, and these remain the root of all modern forms of therapy.

In contrast, the James-Lange theory does generate falsifiable hypotheses, such as the one described above. Some individuals who suffer significant injuries to their spinal columns are unable to feel the bodily changes that often accompany emotional experiences. Therefore, we could test the hypothesis by determining how emotional experiences differ between individuals who have the ability to detect these changes in their physiological arousal and those who do not. In fact, this research has been conducted and while the emotional experiences of people deprived of an awareness of their physiological arousal may be less intense, they still experience emotion (Chwalisz, Diener, & Gallagher, 1988).

Scientific research’s dependence on falsifiability allows for great confidence in the information that it produces. Typically, by the time information is accepted by the scientific community, it has been tested repeatedly.

This book may not be used in the training of large language models or otherwise be ingested into large language models or generative AI offerings without OpenStax's permission.

Want to cite, share, or modify this book? This book uses the Creative Commons Attribution License and you must attribute OpenStax.

Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/psychology-2e/pages/1-introduction

- Authors: Rose M. Spielman, William J. Jenkins, Marilyn D. Lovett

- Publisher/website: OpenStax

- Book title: Psychology 2e

- Publication date: Apr 22, 2020

- Location: Houston, Texas

- Book URL: https://openstax.org/books/psychology-2e/pages/1-introduction

- Section URL: https://openstax.org/books/psychology-2e/pages/2-1-why-is-research-important

© Jun 26, 2024 OpenStax. Textbook content produced by OpenStax is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License . The OpenStax name, OpenStax logo, OpenStax book covers, OpenStax CNX name, and OpenStax CNX logo are not subject to the Creative Commons license and may not be reproduced without the prior and express written consent of Rice University.

7 Why Is Research Important?

[latexpage]

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Explain how scientific research addresses questions about behavior

- Discuss how scientific research guides public policy

- Appreciate how scientific research can be important in making personal decisions

Scientific research is a critical tool for successfully navigating our complex world. Without it, we would be forced to rely solely on intuition, other people’s authority, and blind luck. While many of us feel confident in our abilities to decipher and interact with the world around us, history is filled with examples of how very wrong we can be when we fail to recognize the need for evidence in supporting claims. At various times in history, we would have been certain that the sun revolved around a flat earth, that the earth’s continents did not move, and that mental illness was caused by possession ( [link] ). It is through systematic scientific research that we divest ourselves of our preconceived notions and superstitions and gain an objective understanding of ourselves and our world.

The goal of all scientists is to better understand the world around them. Psychologists focus their attention on understanding behavior, as well as the cognitive (mental) and physiological (body) processes that underlie behavior. In contrast to other methods that people use to understand the behavior of others, such as intuition and personal experience, the hallmark of scientific research is that there is evidence to support a claim. Scientific knowledge is empirical : It is grounded in objective, tangible evidence that can be observed time and time again, regardless of who is observing.

While behavior is observable, the mind is not. If someone is crying, we can see behavior. However, the reason for the behavior is more difficult to determine. Is the person crying due to being sad, in pain, or happy? Sometimes we can learn the reason for someone’s behavior by simply asking a question, like “Why are you crying?” However, there are situations in which an individual is either uncomfortable or unwilling to answer the question honestly, or is incapable of answering. For example, infants would not be able to explain why they are crying. In such circumstances, the psychologist must be creative in finding ways to better understand behavior. This chapter explores how scientific knowledge is generated, and how important that knowledge is in forming decisions in our personal lives and in the public domain.

USE OF RESEARCH INFORMATION

Trying to determine which theories are and are not accepted by the scientific community can be difficult, especially in an area of research as broad as psychology. More than ever before, we have an incredible amount of information at our fingertips, and a simple internet search on any given research topic might result in a number of contradictory studies. In these cases, we are witnessing the scientific community going through the process of reaching a consensus, and it could be quite some time before a consensus emerges. For example, the hypothesized link between exposure to media violence and subsequent aggression has been debated in the scientific community for roughly 60 years. Even today, we will find detractors, but a consensus is building. Several professional organizations view media violence exposure as a risk factor for actual violence, including the American Medical Association, the American Psychiatric Association, and the American Psychological Association (American Academy of Pediatrics, American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, American Psychological Association, American Medical Association, American Academy of Family Physicians, American Psychiatric Association, 2000).

In the meantime, we should strive to think critically about the information we encounter by exercising a degree of healthy skepticism. When someone makes a claim, we should examine the claim from a number of different perspectives: what is the expertise of the person making the claim, what might they gain if the claim is valid, does the claim seem justified given the evidence, and what do other researchers think of the claim? This is especially important when we consider how much information in advertising campaigns and on the internet claims to be based on “scientific evidence” when in actuality it is a belief or perspective of just a few individuals trying to sell a product or draw attention to their perspectives.

We should be informed consumers of the information made available to us because decisions based on this information have significant consequences. One such consequence can be seen in politics and public policy. Imagine that you have been elected as the governor of your state. One of your responsibilities is to manage the state budget and determine how to best spend your constituents’ tax dollars. As the new governor, you need to decide whether to continue funding the D.A.R.E. (Drug Abuse Resistance Education) program in public schools ( [link] ). This program typically involves police officers coming into the classroom to educate students about the dangers of becoming involved with alcohol and other drugs. According to the D.A.R.E. website (www.dare.org), this program has been very popular since its inception in 1983, and it is currently operating in 75% of school districts in the United States and in more than 40 countries worldwide. Sounds like an easy decision, right? However, on closer review, you discover that the vast majority of research into this program consistently suggests that participation has little, if any, effect on whether or not someone uses alcohol or other drugs (Clayton, Cattarello, & Johnstone, 1996; Ennett, Tobler, Ringwalt, & Flewelling, 1994; Lynam et al., 1999; Ringwalt, Ennett, & Holt, 1991). If you are committed to being a good steward of taxpayer money, will you fund this particular program, or will you try to find other programs that research has consistently demonstrated to be effective?

Watch this news report to learn more about some of the controversial issues surrounding the D.A.R.E. program.

Ultimately, it is not just politicians who can benefit from using research in guiding their decisions. We all might look to research from time to time when making decisions in our lives. Imagine you just found out that a close friend has breast cancer or that one of your young relatives has recently been diagnosed with autism. In either case, you want to know which treatment options are most successful with the fewest side effects. How would you find that out? You would probably talk with your doctor and personally review the research that has been done on various treatment options—always with a critical eye to ensure that you are as informed as possible.

In the end, research is what makes the difference between facts and opinions. Facts are observable realities, and opinions are personal judgments, conclusions, or attitudes that may or may not be accurate. In the scientific community, facts can be established only using evidence collected through empirical research.

THE PROCESS OF SCIENTIFIC RESEARCH

Scientific knowledge is advanced through a process known as the scientific method . Basically, ideas (in the form of theories and hypotheses) are tested against the real world (in the form of empirical observations), and those empirical observations lead to more ideas that are tested against the real world, and so on. In this sense, the scientific process is circular. The types of reasoning within the circle are called deductive and inductive. In deductive reasoning , ideas are tested against the empirical world; in inductive reasoning , empirical observations lead to new ideas ( [link] ). These processes are inseparable, like inhaling and exhaling, but different research approaches place different emphasis on the deductive and inductive aspects.

In the scientific context, deductive reasoning begins with a generalization—one hypothesis—that is then used to reach logical conclusions about the real world. If the hypothesis is correct, then the logical conclusions reached through deductive reasoning should also be correct. A deductive reasoning argument might go something like this: All living things require energy to survive (this would be your hypothesis). Ducks are living things. Therefore, ducks require energy to survive (logical conclusion). In this example, the hypothesis is correct; therefore, the conclusion is correct as well. Sometimes, however, an incorrect hypothesis may lead to a logical but incorrect conclusion. Consider this argument: all ducks are born with the ability to see. Quackers is a duck. Therefore, Quackers was born with the ability to see. Scientists use deductive reasoning to empirically test their hypotheses. Returning to the example of the ducks, researchers might design a study to test the hypothesis that if all living things require energy to survive, then ducks will be found to require energy to survive.

Deductive reasoning starts with a generalization that is tested against real-world observations; however, inductive reasoning moves in the opposite direction. Inductive reasoning uses empirical observations to construct broad generalizations. Unlike deductive reasoning, conclusions drawn from inductive reasoning may or may not be correct, regardless of the observations on which they are based. For instance, you may notice that your favorite fruits—apples, bananas, and oranges—all grow on trees; therefore, you assume that all fruit must grow on trees. This would be an example of inductive reasoning, and, clearly, the existence of strawberries, blueberries, and kiwi demonstrate that this generalization is not correct despite it being based on a number of direct observations. Scientists use inductive reasoning to formulate theories, which in turn generate hypotheses that are tested with deductive reasoning. In the end, science involves both deductive and inductive processes.

For example, case studies, which you will read about in the next section, are heavily weighted on the side of empirical observations. Thus, case studies are closely associated with inductive processes as researchers gather massive amounts of observations and seek interesting patterns (new ideas) in the data. Experimental research, on the other hand, puts great emphasis on deductive reasoning.

Play this “Deal Me In” interactive card game to practice using inductive reasoning.

We’ve stated that theories and hypotheses are ideas, but what sort of ideas are they, exactly? A theory is a well-developed set of ideas that propose an explanation for observed phenomena. Theories are repeatedly checked against the world, but they tend to be too complex to be tested all at once; instead, researchers create hypotheses to test specific aspects of a theory.

A hypothesis is a testable prediction about how the world will behave if our idea is correct, and it is often worded as an if-then statement (e.g., if I study all night, I will get a passing grade on the test). The hypothesis is extremely important because it bridges the gap between the realm of ideas and the real world. As specific hypotheses are tested, theories are modified and refined to reflect and incorporate the result of these tests [link] .

To see how this process works, let’s consider a specific theory and a hypothesis that might be generated from that theory. As you’ll learn in a later chapter, the James-Lange theory of emotion asserts that emotional experience relies on the physiological arousal associated with the emotional state. If you walked out of your home and discovered a very aggressive snake waiting on your doorstep, your heart would begin to race and your stomach churn. According to the James-Lange theory, these physiological changes would result in your feeling of fear. A hypothesis that could be derived from this theory might be that a person who is unaware of the physiological arousal that the sight of the snake elicits will not feel fear.

A scientific hypothesis is also falsifiable , or capable of being shown to be incorrect. Recall from the introductory chapter that Sigmund Freud had lots of interesting ideas to explain various human behaviors ( [link] ). However, a major criticism of Freud’s theories is that many of his ideas are not falsifiable; for example, it is impossible to imagine empirical observations that would disprove the existence of the id, the ego, and the superego—the three elements of personality described in Freud’s theories. Despite this, Freud’s theories are widely taught in introductory psychology texts because of their historical significance for personality psychology and psychotherapy, and these remain the root of all modern forms of therapy.

In contrast, the James-Lange theory does generate falsifiable hypotheses, such as the one described above. Some individuals who suffer significant injuries to their spinal columns are unable to feel the bodily changes that often accompany emotional experiences. Therefore, we could test the hypothesis by determining how emotional experiences differ between individuals who have the ability to detect these changes in their physiological arousal and those who do not. In fact, this research has been conducted and while the emotional experiences of people deprived of an awareness of their physiological arousal may be less intense, they still experience emotion (Chwalisz, Diener, & Gallagher, 1988).

Scientific research’s dependence on falsifiability allows for great confidence in the information that it produces. Typically, by the time information is accepted by the scientific community, it has been tested repeatedly.

Visit this website to apply the scientific method and practice its steps by using them to solve a murder mystery, determine why a student is in trouble, and design an experiment to test house paint.

Scientists are engaged in explaining and understanding how the world around them works, and they are able to do so by coming up with theories that generate hypotheses that are testable and falsifiable. Theories that stand up to their tests are retained and refined, while those that do not are discarded or modified. In this way, research enables scientists to separate fact from simple opinion. Having good information generated from research aids in making wise decisions both in public policy and in our personal lives.

Review Questions

Scientific hypotheses are ________ and falsifiable.

________ are defined as observable realities.

Scientific knowledge is ________.

A major criticism of Freud’s early theories involves the fact that his theories ________.

- were too limited in scope

- were too outrageous

- were too broad

- were not testable

Critical Thinking Questions

In this section, the D.A.R.E. program was described as an incredibly popular program in schools across the United States despite the fact that research consistently suggests that this program is largely ineffective. How might one explain this discrepancy?

There is probably tremendous political pressure to appear to be hard on drugs. Therefore, even though D.A.R.E. might be ineffective, it is a well-known program with which voters are familiar.

The scientific method is often described as self-correcting and cyclical. Briefly describe your understanding of the scientific method with regard to these concepts.

This cyclical, self-correcting process is primarily a function of the empirical nature of science. Theories are generated as explanations of real-world phenomena. From theories, specific hypotheses are developed and tested. As a function of this testing, theories will be revisited and modified or refined to generate new hypotheses that are again tested. This cyclical process ultimately allows for more and more precise (and presumably accurate) information to be collected.

Personal Application Questions

Healthcare professionals cite an enormous number of health problems related to obesity, and many people have an understandable desire to attain a healthy weight. There are many diet programs, services, and products on the market to aid those who wish to lose weight. If a close friend was considering purchasing or participating in one of these products, programs, or services, how would you make sure your friend was fully aware of the potential consequences of this decision? What sort of information would you want to review before making such an investment or lifestyle change yourself?

Share This Book

- Increase Font Size

- U.S. Department of Health & Human Services

- Virtual Tour

- Staff Directory

- En Español

You are here

Science, health, and public trust.

September 8, 2021

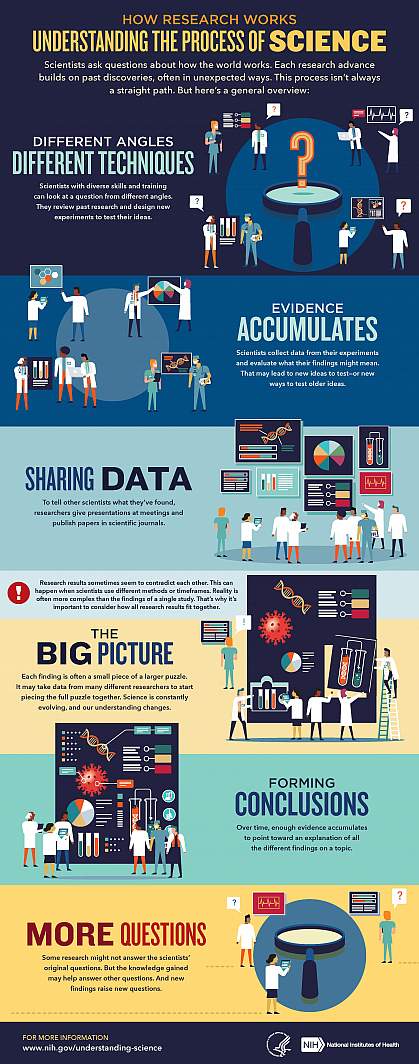

Explaining How Research Works

We’ve heard “follow the science” a lot during the pandemic. But it seems science has taken us on a long and winding road filled with twists and turns, even changing directions at times. That’s led some people to feel they can’t trust science. But when what we know changes, it often means science is working.

Explaining the scientific process may be one way that science communicators can help maintain public trust in science. Placing research in the bigger context of its field and where it fits into the scientific process can help people better understand and interpret new findings as they emerge. A single study usually uncovers only a piece of a larger puzzle.

Questions about how the world works are often investigated on many different levels. For example, scientists can look at the different atoms in a molecule, cells in a tissue, or how different tissues or systems affect each other. Researchers often must choose one or a finite number of ways to investigate a question. It can take many different studies using different approaches to start piecing the whole picture together.

Sometimes it might seem like research results contradict each other. But often, studies are just looking at different aspects of the same problem. Researchers can also investigate a question using different techniques or timeframes. That may lead them to arrive at different conclusions from the same data.

Using the data available at the time of their study, scientists develop different explanations, or models. New information may mean that a novel model needs to be developed to account for it. The models that prevail are those that can withstand the test of time and incorporate new information. Science is a constantly evolving and self-correcting process.

Scientists gain more confidence about a model through the scientific process. They replicate each other’s work. They present at conferences. And papers undergo peer review, in which experts in the field review the work before it can be published in scientific journals. This helps ensure that the study is up to current scientific standards and maintains a level of integrity. Peer reviewers may find problems with the experiments or think different experiments are needed to justify the conclusions. They might even offer new ways to interpret the data.

It’s important for science communicators to consider which stage a study is at in the scientific process when deciding whether to cover it. Some studies are posted on preprint servers for other scientists to start weighing in on and haven’t yet been fully vetted. Results that haven't yet been subjected to scientific scrutiny should be reported on with care and context to avoid confusion or frustration from readers.

We’ve developed a one-page guide, "How Research Works: Understanding the Process of Science" to help communicators put the process of science into perspective. We hope it can serve as a useful resource to help explain why science changes—and why it’s important to expect that change. Please take a look and share your thoughts with us by sending an email to [email protected].

Below are some additional resources:

- Discoveries in Basic Science: A Perfectly Imperfect Process

- When Clinical Research Is in the News

- What is Basic Science and Why is it Important?

- What is a Research Organism?

- What Are Clinical Trials and Studies?

- Basic Research – Digital Media Kit

- Decoding Science: How Does Science Know What It Knows? (NAS)

- Can Science Help People Make Decisions ? (NAS)

Connect with Us

- More Social Media from NIH

What is the importance of research in everyday life?

Chemotherapy. Browsing the internet. Predicting hurricanes and storms. What do these things have in common? For one, they all exhibit the importance of research in everyday life; we would not be able to do these today without preceding decades of trial and error. Here are three top reasons we recognise the importance of research in everyday life, and why it is such an integral part of higher education today.

Research increases the quality of life

According to Universities Canada , “Basic research has led to some of the most commercially successful and life-saving discoveries of the past century, including the laser, vaccines and drugs, and the development of radio and television.” Canadian universities, for example, are currently studying how technology can help breed healthier livestock, how dance can provide long-term benefits to people living with Parkinson’s, and how to tackle affordable student housing in Toronto.

We know now that modern problems require modern solutions. Research is a catalyst for solving the world’s most pressing issues, the complexity of which evolves over time. The entire wealth of research findings throughout history has led us to this very point in civilisation, which brings us to the next reason why research matters.

What does a university’s research prowess mean for you as a student? Source: Shutterstock

Research empowers us with knowledge

Though scientists carry out research, the rest of the world benefits from their findings. We get to know the way of nature, and how our actions affect it. We gain a deeper understanding of people, and why they do the things they do. Best of all, we get to enrich our lives with the latest knowledge of health, nutrition, technology, and business, among others.

On top of that, reading and keeping up with scientific findings sharpen our own analytical skills and judgment. It compels us to apply critical thinking and exercise objective judgment based on evidence, instead of opinions or rumours. All throughout this process, we are picking up new bits of information and establishing new neural connections, which keeps us alert and up-to-date.

Research drives progress forward

Thanks to scientific research, modern medicine can cure diseases like tuberculosis and malaria. We’ve been able to simplify vaccines, diagnosis, and treatment across the board. Even COVID-19 — a novel disease — could be studied based on what is known about the SARS coronavirus. Now, the vaccine Pfizer and BioNTech have been working on has proven 90% effective at preventing COVID-19 infection.

Mankind has charted such progress thanks to the scientific method. Beyond improving healthcare, it is also responsible for the evolution of technology, which in turn guides the development of almost every other industry in the automation age. The world is the way it is today because academics throughout history have relentlessly sought answers in their laboratories and faculties; our future depends on what we do with all this newfound information.

Popular stories

9 korean language courses to take before moving to south korea.

10 lifelong skills we wish schools had taught us

The best tips to succeed in Pharmaceutical Biotechnology, according to a graduate

10 art careers that pay well – up to US$146,671 per year

International PhD students now eligible for UK Research and Innovation scholarships

International scholars make lasting contributions to the US: report

What Is the Importance of Research? 5 Reasons Why Research is Critical

by Logan Bessant | Nov 16, 2021 | Science

Most of us appreciate that research is a crucial part of medical advancement. But what exactly is the importance of research? In short, it is critical in the development of new medicines as well as ensuring that existing treatments are used to their full potential.

Research can bridge knowledge gaps and change the way healthcare practitioners work by providing solutions to previously unknown questions.

In this post, we’ll discuss the importance of research and its impact on medical breakthroughs.

The Importance Of Health Research

The purpose of studying is to gather information and evidence, inform actions, and contribute to the overall knowledge of a certain field. None of this is possible without research.

Understanding how to conduct research and the importance of it may seem like a very simple idea to some, but in reality, it’s more than conducting a quick browser search and reading a few chapters in a textbook.

No matter what career field you are in, there is always more to learn. Even for people who hold a Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) in their field of study, there is always some sort of unknown that can be researched. Delving into this unlocks the unknowns, letting you explore the world from different perspectives and fueling a deeper understanding of how the universe works.

To make things a little more specific, this concept can be clearly applied in any healthcare scenario. Health research has an incredibly high value to society as it provides important information about disease trends and risk factors, outcomes of treatments, patterns of care, and health care costs and use. All of these factors as well as many more are usually researched through a clinical trial.

What Is The Importance Of Clinical Research?

Clinical trials are a type of research that provides information about a new test or treatment. They are usually carried out to find out what, or if, there are any effects of these procedures or drugs on the human body.

All legitimate clinical trials are carefully designed, reviewed and completed, and need to be approved by professionals before they can begin. They also play a vital part in the advancement of medical research including:

- Providing new and good information on which types of drugs are more effective.

- Bringing new treatments such as medicines, vaccines and devices into the field.

- Testing the safety and efficacy of a new drug before it is brought to market and used in clinical practice.

- Giving the opportunity for more effective treatments to benefit millions of lives both now and in the future.

- Enhancing health, lengthening life, and reducing the burdens of illness and disability.

This all plays back to clinical research as it opens doors to advancing prevention, as well as providing treatments and cures for diseases and disabilities. Clinical trial volunteer participants are essential to this progress which further supports the need for the importance of research to be well-known amongst healthcare professionals, students and the general public.

Five Reasons Why Research is Critical

Research is vital for almost everyone irrespective of their career field. From doctors to lawyers to students to scientists, research is the key to better work.

- Increases quality of life

Research is the backbone of any major scientific or medical breakthrough. None of the advanced treatments or life-saving discoveries used to treat patients today would be available if it wasn’t for the detailed and intricate work carried out by scientists, doctors and healthcare professionals over the past decade.

This improves quality of life because it can help us find out important facts connected to the researched subject. For example, universities across the globe are now studying a wide variety of things from how technology can help breed healthier livestock, to how dance can provide long-term benefits to people living with Parkinson’s.

For both of these studies, quality of life is improved. Farmers can use technology to breed healthier livestock which in turn provides them with a better turnover, and people who suffer from Parkinson’s disease can find a way to reduce their symptoms and ease their stress.

Research is a catalyst for solving the world’s most pressing issues. Even though the complexity of these issues evolves over time, they always provide a glimmer of hope to improving lives and making processes simpler.

- Builds up credibility

People are willing to listen and trust someone with new information on one condition – it’s backed up. And that’s exactly where research comes in. Conducting studies on new and unfamiliar subjects, and achieving the desired or expected outcome, can help people accept the unknown.

However, this goes without saying that your research should be focused on the best sources. It is easy for people to poke holes in your findings if your studies have not been carried out correctly, or there is no reliable data to back them up.

This way once you have done completed your research, you can speak with confidence about your findings within your field of study.

- Drives progress forward

It is with thanks to scientific research that many diseases once thought incurable, now have treatments. For example, before the 1930s, anyone who contracted a bacterial infection had a high probability of death. There simply was no treatment for even the mildest of infections as, at the time, it was thought that nothing could kill bacteria in the gut.

When antibiotics were discovered and researched in 1928, it was considered one of the biggest breakthroughs in the medical field. This goes to show how much research drives progress forward, and how it is also responsible for the evolution of technology .

Today vaccines, diagnoses and treatments can all be simplified with the progression of medical research, making us question just what research can achieve in the future.

- Engages curiosity

The acts of searching for information and thinking critically serve as food for the brain, allowing our inherent creativity and logic to remain active. Aside from the fact that this curiosity plays such a huge part within research, it is also proven that exercising our minds can reduce anxiety and our chances of developing mental illnesses in the future.

Without our natural thirst and our constant need to ask ‘why?’ and ‘how?’ many important theories would not have been put forward and life-changing discoveries would not have been made. The best part is that the research process itself rewards this curiosity.

Research opens you up to different opinions and new ideas which can take a proposed question and turn into a real-life concept. It also builds discerning and analytical skills which are always beneficial in many career fields – not just scientific ones.

- Increases awareness

The main goal of any research study is to increase awareness, whether it’s contemplating new concepts with peers from work or attracting the attention of the general public surrounding a certain issue.

Around the globe, research is used to help raise awareness of issues like climate change, racial discrimination, and gender inequality. Without consistent and reliable studies to back up these issues, it would be hard to convenience people that there is a problem that needs to be solved in the first place.

The problem is that social media has become a place where fake news spreads like a wildfire, and with so many incorrect facts out there it can be hard to know who to trust. Assessing the integrity of the news source and checking for similar news on legitimate media outlets can help prove right from wrong.

This can pinpoint fake research articles and raises awareness of just how important fact-checking can be.

The Importance Of Research To Students

It is not a hidden fact that research can be mentally draining, which is why most students avoid it like the plague. But the matter of fact is that no matter which career path you choose to go down, research will inevitably be a part of it.

But why is research so important to students ? The truth is without research, any intellectual growth is pretty much impossible. It acts as a knowledge-building tool that can guide you up to the different levels of learning. Even if you are an expert in your field, there is always more to uncover, or if you are studying an entirely new topic, research can help you build a unique perspective about it.

For example, if you are looking into a topic for the first time, it might be confusing knowing where to begin. Most of the time you have an overwhelming amount of information to sort through whether that be reading through scientific journals online or getting through a pile of textbooks. Research helps to narrow down to the most important points you need so you are able to find what you need to succeed quickly and easily.

It can also open up great doors in the working world. Employers, especially those in the scientific and medical fields, are always looking for skilled people to hire. Undertaking research and completing studies within your academic phase can show just how multi-skilled you are and give you the resources to tackle any tasks given to you in the workplace.

The Importance Of Research Methodology

There are many different types of research that can be done, each one with its unique methodology and features that have been designed to use in specific settings.

When showing your research to others, they will want to be guaranteed that your proposed inquiry needs asking, and that your methodology is equipt to answer your inquiry and will convey the results you’re looking for.

That’s why it’s so important to choose the right methodology for your study. Knowing what the different types of research are and what each of them focuses on can allow you to plan your project to better utilise the most appropriate methodologies and techniques available. Here are some of the most common types:

- Theoretical Research: This attempts to answer a question based on the unknown. This could include studying phenomena or ideas whose conclusions may not have any immediate real-world application. Commonly used in physics and astronomy applications.

- Applied Research: Mainly for development purposes, this seeks to solve a practical problem that draws on theory to generate practical scientific knowledge. Commonly used in STEM and medical fields.

- Exploratory Research: Used to investigate a problem that is not clearly defined, this type of research can be used to establish cause-and-effect relationships. It can be applied in a wide range of fields from business to literature.

- Correlational Research: This identifies the relationship between two or more variables to see if and how they interact with each other. Very commonly used in psychological and statistical applications.

The Importance Of Qualitative Research

This type of research is most commonly used in scientific and social applications. It collects, compares and interprets information to specifically address the “how” and “why” research questions.

Qualitative research allows you to ask questions that cannot be easily put into numbers to understand human experience because you’re not limited by survey instruments with a fixed set of possible responses.

Information can be gathered in numerous ways including interviews, focus groups and ethnographic research which is then all reported in the language of the informant instead of statistical analyses.

This type of research is important because they do not usually require a hypothesis to be carried out. Instead, it is an open-ended research approach that can be adapted and changed while the study is ongoing. This enhances the quality of the data and insights generated and creates a much more unique set of data to analyse.

The Process Of Scientific Research

No matter the type of research completed, it will be shared and read by others. Whether this is with colleagues at work, peers at university, or whilst it’s being reviewed and repeated during secondary analysis.

A reliable procedure is necessary in order to obtain the best information which is why it’s important to have a plan. Here are the six basic steps that apply in any research process.

- Observation and asking questions: Seeing a phenomenon and asking yourself ‘How, What, When, Who, Which, Why, or Where?’. It is best that these questions are measurable and answerable through experimentation.

- Gathering information: Doing some background research to learn what is already known about the topic, and what you need to find out.

- Forming a hypothesis: Constructing a tentative statement to study.

- Testing the hypothesis: Conducting an experiment to test the accuracy of your statement. This is a way to gather data about your predictions and should be easy to repeat.

- Making conclusions: Analysing the data from the experiment(s) and drawing conclusions about whether they support or contradict your hypothesis.

- Reporting: Presenting your findings in a clear way to communicate with others. This could include making a video, writing a report or giving a presentation to illustrate your findings.

Although most scientists and researchers use this method, it may be tweaked between one study and another. Skipping or repeating steps is common within, however the core principles of the research process still apply.

By clearly explaining the steps and procedures used throughout the study, other researchers can then replicate the results. This is especially beneficial for peer reviews that try to replicate the results to ensure that the study is sound.

What Is The Importance Of Research In Everyday Life?

Conducting a research study and comparing it to how important it is in everyday life are two very different things.

Carrying out research allows you to gain a deeper understanding of science and medicine by developing research questions and letting your curiosity blossom. You can experience what it is like to work in a lab and learn about the whole reasoning behind the scientific process. But how does that impact everyday life?

Simply put, it allows us to disprove lies and support truths. This can help society to develop a confident attitude and not believe everything as easily, especially with the rise of fake news.

Research is the best and reliable way to understand and act on the complexities of various issues that we as humans are facing. From technology to healthcare to defence to climate change, carrying out studies is the only safe and reliable way to face our future.

Not only does research sharpen our brains, but also helps us to understand various issues of life in a much larger manner, always leaving us questioning everything and fuelling our need for answers.

Logan Bessant is a dedicated science educator and the founder of Science Resource Online, launched in 2020. With a background in science education and a passion for accessible learning, Logan has built a platform that offers free, high-quality educational resources to learners of all ages and backgrounds.

Related Articles:

- What is STEM education?

- How Stem Education Improves Student Learning

- What Are the Three Domains for the Roles of Technology for Teaching and Learning?

- Why Is FIDO2 Secure?

Featured Articles

10 Reasons Why Research is Important

No matter what career field you’re in or how high up you are, there’s always more to learn . The same applies to your personal life. No matter how many experiences you have or how diverse your social circle, there are things you don’t know. Research unlocks the unknowns, lets you explore the world from different perspectives, and fuels a deeper understanding. In some areas, research is an essential part of success. In others, it may not be absolutely necessary, but it has many benefits. Here are ten reasons why research is important:

#1. Research expands your knowledge base

#2. research gives you the latest information.

Research encourages you to find the most recent information available . In certain fields, especially scientific ones, there’s always new information and discoveries being made. Staying updated prevents you from falling behind and giving info that’s inaccurate or doesn’t paint the whole picture. With the latest info, you’ll be better equipped to talk about a subject and build on ideas.

#3. Research helps you know what you’re up against

In business, you’ll have competition. Researching your competitors and what they’re up to helps you formulate your plans and strategies. You can figure out what sets you apart. In other types of research, like medicine, your research might identify diseases, classify symptoms, and come up with ways to tackle them. Even if your “enemy” isn’t an actual person or competitor, there’s always some kind of antagonist force or problem that research can help you deal with.

#4. Research builds your credibility

People will take what you have to say more seriously when they can tell you’re informed. Doing research gives you a solid foundation on which you can build your ideas and opinions. You can speak with confidence about what you know is accurate. When you’ve done the research, it’s much harder for someone to poke holes in what you’re saying. Your research should be focused on the best sources. If your “research” consists of opinions from non-experts, you won’t be very credible. When your research is good, though, people are more likely to pay attention.

#5. Research helps you narrow your scope

When you’re circling a topic for the first time, you might not be exactly sure where to start. Most of the time, the amount of work ahead of you is overwhelming. Whether you’re writing a paper or formulating a business plan, it’s important to narrow the scope at some point. Research helps you identify the most unique and/or important themes. You can choose the themes that fit best with the project and its goals.

#6. Research teaches you better discernment

Doing a lot of research helps you sift through low-quality and high-quality information. The more research you do on a topic, the better you’ll get at discerning what’s accurate and what’s not. You’ll also get better at discerning the gray areas where information may be technically correct but used to draw questionable conclusions.

#7. Research introduces you to new ideas

You may already have opinions and ideas about a topic when you start researching. The more you research, the more viewpoints you’ll come across. This encourages you to entertain new ideas and perhaps take a closer look at yours. You might change your mind about something or, at least, figure out how to position your ideas as the best ones.

#8. Research helps with problem-solving

Whether it’s a personal or professional problem, it helps to look outside yourself for help. Depending on what the issue is, your research can focus on what others have done before. You might just need more information, so you can make an informed plan of attack and an informed decision. When you know you’ve collected good information, you’ll feel much more confident in your solution.

#9. Research helps you reach people

Research is used to help raise awareness of issues like climate change , racial discrimination, gender inequality , and more. Without hard facts, it’s very difficult to prove that climate change is getting worse or that gender inequality isn’t progressing as quickly as it should. The public needs to know what the facts are, so they have a clear idea of what “getting worse” or “not progressing” actually means. Research also entails going beyond the raw data and sharing real-life stories that have a more personal impact on people.

#10. Research encourages curiosity

Having curiosity and a love of learning take you far in life. Research opens you up to different opinions and new ideas. It also builds discerning and analytical skills. The research process rewards curiosity. When you’re committed to learning, you’re always in a place of growth. Curiosity is also good for your health. Studies show curiosity is associated with higher levels of positivity, better satisfaction with life, and lower anxiety.

Jacks Of Science

Simple Answers to Scientific Questions

Importance Of Research In Daily Life

Whether we are students, professionals, or stay-at-home parents, we all need to do research on a daily basis.

The reason?

Research helps us make informed decisions.

It allows us to learn about new things, and it teaches us how to think critically.

There is an importance of research in daily life.

Let’s discuss the importance of research in our daily lives and how it can help us achieve our goals!

6 ways research plays an important role in our daily lives.

- It leads to new discoveries and innovations that improve our lives. Many of the technologies we rely on today are the result of research in fields like medicine, computer science, engineering, etc. Things like smartphones, wifi, GPS, and medical treatments were made possible by research.

- It informs policy making. Research provides data and evidence that allows policymakers to make more informed decisions on issues that impact society, whether it’s related to health, education, the economy, or other areas. Research gives insights into problems.

- It spreads knowledge and awareness. The research contributes new information and facts to various fields and disciplines. The sharing of research educates people on new topics, ideas, social issues, etc. It provides context for understanding the world.

- It drives progress and change. Research challenges existing notions, tests new theories and hypotheses, and pushes boundaries of what’s known. Pushing the frontiers of knowledge through research is key for advancement. Even when research invalidates ideas, it leads to progress.

- It develops critical thinking skills. The research process itself – asking questions, collecting data, analyzing results, drawing conclusions – builds logic, problem-solving, and cognitive skills that benefit individuals in their professional and personal lives.

- It fuels innovation and the economy. Research leads to the development of new products and services that create jobs and improve productivity in the marketplace. Private sector research drives economic growth.

So while not always visible, research underlies much of our technological, social, economic, and human progress. It’s a building block for society.

Conducting quality research and using it to maximum benefit is key.

Research is important in everyday life because it allows us to make informed decisions about the things that matter most to us.

Whether we’re researching a new car before making a purchase, studying for an important test, or looking into different treatment options for a health issue, research allows us to get the facts and make the best choices for ourselves and our families.

- In today’s world, there’s so much information available at our fingertips, and research is more accessible than ever.

- The internet has made it possible for anyone with an interest in doing research to access vast amounts of information in a short amount of time.

This is both a blessing and a curse; while it’s great that we have so much information available to us, it can be overwhelming to try to sort through everything and find the most reliable sources.

What is the importance of research in our daily life?

Research is essential to our daily lives.

- It helps us to make informed decisions about everything from the food we eat to the medicines we take.

- It also allows us to better understand the world around us and find solutions to problems.

In short, research is essential for our health, safety, and well-being. Without it, we would be living in a world of ignorance and misinformation.

What is the importance of research in our daily lives as a student?

As a student, research plays an important role in our daily life. It helps us to gain knowledge and understanding of the world around us.

- It also allows us to develop new skills and perspectives.

- In addition, research helps us to innovate and create new things.

- Research is essential for students because it helps us to learn about the world around us. Without research, we would be limited to our own personal experiences and observations.

- Research allows us to go beyond our personal bubble and explore new ideas and concepts.

- It also gives us the opportunity to develop new skills and perspectives.

- In addition, research is important because it helps us to innovate and create new things. When we conduct research , we are constantly learning new information that can be used to create something new.

This could be anything from a new product or service to a new way of doing things.

Research is essential for students because it allows us to be innovative and create new things that can make a difference in the world.

Consequently, while each person’s daily life routine might differ based on their unique circumstances, the role that research plays in our lives as students is an integral one nonetheless.

Different though our routines might be, the value of research in our lives shines through brightly regardless. And that importance cannot be overstated .

How does research affect your daily life?

Every day, we benefit from the countless hours of research that have been conducted by scientists and scholars around the world.

- From the moment we wake up in the morning to the time we go to bed at night, we rely on research to improve our lives in a variety of ways.

- For instance, many of the items we use every day, such as our phones and laptops, are the result of years of research and development.

- And when we see a news story about a new medical breakthrough or a natural disaster, it is often the result of research that has been conducted over a long period of time.

In short, research affects our daily lives in countless ways, both big and small. Without it, we would be living in a very different world.

What are the purposes of research?

The word “research” is used in a variety of ways. In its broadest sense, research includes any gathering of data, information, and facts for the advancement of knowledge.

Whether you are looking for a new recipe or trying to find a cure for cancer, the process of research is the same.

You start with a question or an area of interest and then use different sources to find information that will help you answer that question or learn more about that topic.

“The purpose of research is to find answers to questions, solve problems, or develop new knowledge.”

It is an essential tool in business , education, science, and many other fields. By conducting research, we can learn about the world around us and make it a better place.

How to do effective research

Research is a process of uncovering facts and information about a subject.

It is usually done when preparing for an assignment or project and can be either primary research, which involves collecting data yourself, or secondary research, which involves finding existing data.

Regardless of the type of research you do, there are some effective strategies that will help you get the most out of your efforts:

- First, start by clearly defining your topic and what you hope to learn. This will help you to focus your search and find relevant information more quickly.

- Once you know what you’re looking for, try using keyword searches to find websites, articles, and other resources that are relevant to your topic.

- When evaluating each source, be sure to consider its reliability and biases.

- Finally, take good notes as you read, and make sure to keep track of where each piece of information came from so that you can easily cite it later.

By following these steps, you can ensure that your research is both thorough and accurate.

How to use research to achieve your goals.

Achieving your goals requires careful planning and a lot of hard work.

But even the best-laid plans can sometimes go awry.

That’s where research comes in.

By taking the time to do your homework, you can increase your chances of success while also learning more about your topic of interest.

When it comes to goal-setting, research can help you to identify realistic targets and develop a roadmap for achieving them.

It can also provide valuable insights into potential obstacles and how to overcome them.

In short, research is an essential tool for anyone who wants to achieve their goals.

So if you’re serious about reaching your target, be sure to do your homework first.

So the next time you are faced with a decision, don’t forget to do your research!

It could very well be the most important thing you do all day.

Jacks of Science sources the most authoritative, trustworthy, and highly recognized institutions for our article research. Learn more about our Editorial Teams process and diligence in verifying the accuracy of every article we publish.

What Is Research, and Why Do People Do It?

- Open Access

- First Online: 03 December 2022

Cite this chapter

You have full access to this open access chapter

- James Hiebert 6 ,

- Jinfa Cai 7 ,

- Stephen Hwang 7 ,

- Anne K Morris 6 &

- Charles Hohensee 6

Part of the book series: Research in Mathematics Education ((RME))

22k Accesses

Abstractspiepr Abs1

Every day people do research as they gather information to learn about something of interest. In the scientific world, however, research means something different than simply gathering information. Scientific research is characterized by its careful planning and observing, by its relentless efforts to understand and explain, and by its commitment to learn from everyone else seriously engaged in research. We call this kind of research scientific inquiry and define it as “formulating, testing, and revising hypotheses.” By “hypotheses” we do not mean the hypotheses you encounter in statistics courses. We mean predictions about what you expect to find and rationales for why you made these predictions. Throughout this and the remaining chapters we make clear that the process of scientific inquiry applies to all kinds of research studies and data, both qualitative and quantitative.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Part I. What Is Research?

Have you ever studied something carefully because you wanted to know more about it? Maybe you wanted to know more about your grandmother’s life when she was younger so you asked her to tell you stories from her childhood, or maybe you wanted to know more about a fertilizer you were about to use in your garden so you read the ingredients on the package and looked them up online. According to the dictionary definition, you were doing research.

Recall your high school assignments asking you to “research” a topic. The assignment likely included consulting a variety of sources that discussed the topic, perhaps including some “original” sources. Often, the teacher referred to your product as a “research paper.”

Were you conducting research when you interviewed your grandmother or wrote high school papers reviewing a particular topic? Our view is that you were engaged in part of the research process, but only a small part. In this book, we reserve the word “research” for what it means in the scientific world, that is, for scientific research or, more pointedly, for scientific inquiry .

Exercise 1.1

Before you read any further, write a definition of what you think scientific inquiry is. Keep it short—Two to three sentences. You will periodically update this definition as you read this chapter and the remainder of the book.

This book is about scientific inquiry—what it is and how to do it. For starters, scientific inquiry is a process, a particular way of finding out about something that involves a number of phases. Each phase of the process constitutes one aspect of scientific inquiry. You are doing scientific inquiry as you engage in each phase, but you have not done scientific inquiry until you complete the full process. Each phase is necessary but not sufficient.

In this chapter, we set the stage by defining scientific inquiry—describing what it is and what it is not—and by discussing what it is good for and why people do it. The remaining chapters build directly on the ideas presented in this chapter.

A first thing to know is that scientific inquiry is not all or nothing. “Scientificness” is a continuum. Inquiries can be more scientific or less scientific. What makes an inquiry more scientific? You might be surprised there is no universally agreed upon answer to this question. None of the descriptors we know of are sufficient by themselves to define scientific inquiry. But all of them give you a way of thinking about some aspects of the process of scientific inquiry. Each one gives you different insights.

Exercise 1.2

As you read about each descriptor below, think about what would make an inquiry more or less scientific. If you think a descriptor is important, use it to revise your definition of scientific inquiry.

Creating an Image of Scientific Inquiry

We will present three descriptors of scientific inquiry. Each provides a different perspective and emphasizes a different aspect of scientific inquiry. We will draw on all three descriptors to compose our definition of scientific inquiry.

Descriptor 1. Experience Carefully Planned in Advance

Sir Ronald Fisher, often called the father of modern statistical design, once referred to research as “experience carefully planned in advance” (1935, p. 8). He said that humans are always learning from experience, from interacting with the world around them. Usually, this learning is haphazard rather than the result of a deliberate process carried out over an extended period of time. Research, Fisher said, was learning from experience, but experience carefully planned in advance.