- Privacy Policy

Buy Me a Coffee

Home » What is a Hypothesis – Types, Examples and Writing Guide

What is a Hypothesis – Types, Examples and Writing Guide

Table of Contents

Definition:

Hypothesis is an educated guess or proposed explanation for a phenomenon, based on some initial observations or data. It is a tentative statement that can be tested and potentially proven or disproven through further investigation and experimentation.

Hypothesis is often used in scientific research to guide the design of experiments and the collection and analysis of data. It is an essential element of the scientific method, as it allows researchers to make predictions about the outcome of their experiments and to test those predictions to determine their accuracy.

Types of Hypothesis

Types of Hypothesis are as follows:

Research Hypothesis

A research hypothesis is a statement that predicts a relationship between variables. It is usually formulated as a specific statement that can be tested through research, and it is often used in scientific research to guide the design of experiments.

Null Hypothesis

The null hypothesis is a statement that assumes there is no significant difference or relationship between variables. It is often used as a starting point for testing the research hypothesis, and if the results of the study reject the null hypothesis, it suggests that there is a significant difference or relationship between variables.

Alternative Hypothesis

An alternative hypothesis is a statement that assumes there is a significant difference or relationship between variables. It is often used as an alternative to the null hypothesis and is tested against the null hypothesis to determine which statement is more accurate.

Directional Hypothesis

A directional hypothesis is a statement that predicts the direction of the relationship between variables. For example, a researcher might predict that increasing the amount of exercise will result in a decrease in body weight.

Non-directional Hypothesis

A non-directional hypothesis is a statement that predicts the relationship between variables but does not specify the direction. For example, a researcher might predict that there is a relationship between the amount of exercise and body weight, but they do not specify whether increasing or decreasing exercise will affect body weight.

Statistical Hypothesis

A statistical hypothesis is a statement that assumes a particular statistical model or distribution for the data. It is often used in statistical analysis to test the significance of a particular result.

Composite Hypothesis

A composite hypothesis is a statement that assumes more than one condition or outcome. It can be divided into several sub-hypotheses, each of which represents a different possible outcome.

Empirical Hypothesis

An empirical hypothesis is a statement that is based on observed phenomena or data. It is often used in scientific research to develop theories or models that explain the observed phenomena.

Simple Hypothesis

A simple hypothesis is a statement that assumes only one outcome or condition. It is often used in scientific research to test a single variable or factor.

Complex Hypothesis

A complex hypothesis is a statement that assumes multiple outcomes or conditions. It is often used in scientific research to test the effects of multiple variables or factors on a particular outcome.

Applications of Hypothesis

Hypotheses are used in various fields to guide research and make predictions about the outcomes of experiments or observations. Here are some examples of how hypotheses are applied in different fields:

- Science : In scientific research, hypotheses are used to test the validity of theories and models that explain natural phenomena. For example, a hypothesis might be formulated to test the effects of a particular variable on a natural system, such as the effects of climate change on an ecosystem.

- Medicine : In medical research, hypotheses are used to test the effectiveness of treatments and therapies for specific conditions. For example, a hypothesis might be formulated to test the effects of a new drug on a particular disease.

- Psychology : In psychology, hypotheses are used to test theories and models of human behavior and cognition. For example, a hypothesis might be formulated to test the effects of a particular stimulus on the brain or behavior.

- Sociology : In sociology, hypotheses are used to test theories and models of social phenomena, such as the effects of social structures or institutions on human behavior. For example, a hypothesis might be formulated to test the effects of income inequality on crime rates.

- Business : In business research, hypotheses are used to test the validity of theories and models that explain business phenomena, such as consumer behavior or market trends. For example, a hypothesis might be formulated to test the effects of a new marketing campaign on consumer buying behavior.

- Engineering : In engineering, hypotheses are used to test the effectiveness of new technologies or designs. For example, a hypothesis might be formulated to test the efficiency of a new solar panel design.

How to write a Hypothesis

Here are the steps to follow when writing a hypothesis:

Identify the Research Question

The first step is to identify the research question that you want to answer through your study. This question should be clear, specific, and focused. It should be something that can be investigated empirically and that has some relevance or significance in the field.

Conduct a Literature Review

Before writing your hypothesis, it’s essential to conduct a thorough literature review to understand what is already known about the topic. This will help you to identify the research gap and formulate a hypothesis that builds on existing knowledge.

Determine the Variables

The next step is to identify the variables involved in the research question. A variable is any characteristic or factor that can vary or change. There are two types of variables: independent and dependent. The independent variable is the one that is manipulated or changed by the researcher, while the dependent variable is the one that is measured or observed as a result of the independent variable.

Formulate the Hypothesis

Based on the research question and the variables involved, you can now formulate your hypothesis. A hypothesis should be a clear and concise statement that predicts the relationship between the variables. It should be testable through empirical research and based on existing theory or evidence.

Write the Null Hypothesis

The null hypothesis is the opposite of the alternative hypothesis, which is the hypothesis that you are testing. The null hypothesis states that there is no significant difference or relationship between the variables. It is important to write the null hypothesis because it allows you to compare your results with what would be expected by chance.

Refine the Hypothesis

After formulating the hypothesis, it’s important to refine it and make it more precise. This may involve clarifying the variables, specifying the direction of the relationship, or making the hypothesis more testable.

Examples of Hypothesis

Here are a few examples of hypotheses in different fields:

- Psychology : “Increased exposure to violent video games leads to increased aggressive behavior in adolescents.”

- Biology : “Higher levels of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere will lead to increased plant growth.”

- Sociology : “Individuals who grow up in households with higher socioeconomic status will have higher levels of education and income as adults.”

- Education : “Implementing a new teaching method will result in higher student achievement scores.”

- Marketing : “Customers who receive a personalized email will be more likely to make a purchase than those who receive a generic email.”

- Physics : “An increase in temperature will cause an increase in the volume of a gas, assuming all other variables remain constant.”

- Medicine : “Consuming a diet high in saturated fats will increase the risk of developing heart disease.”

Purpose of Hypothesis

The purpose of a hypothesis is to provide a testable explanation for an observed phenomenon or a prediction of a future outcome based on existing knowledge or theories. A hypothesis is an essential part of the scientific method and helps to guide the research process by providing a clear focus for investigation. It enables scientists to design experiments or studies to gather evidence and data that can support or refute the proposed explanation or prediction.

The formulation of a hypothesis is based on existing knowledge, observations, and theories, and it should be specific, testable, and falsifiable. A specific hypothesis helps to define the research question, which is important in the research process as it guides the selection of an appropriate research design and methodology. Testability of the hypothesis means that it can be proven or disproven through empirical data collection and analysis. Falsifiability means that the hypothesis should be formulated in such a way that it can be proven wrong if it is incorrect.

In addition to guiding the research process, the testing of hypotheses can lead to new discoveries and advancements in scientific knowledge. When a hypothesis is supported by the data, it can be used to develop new theories or models to explain the observed phenomenon. When a hypothesis is not supported by the data, it can help to refine existing theories or prompt the development of new hypotheses to explain the phenomenon.

When to use Hypothesis

Here are some common situations in which hypotheses are used:

- In scientific research , hypotheses are used to guide the design of experiments and to help researchers make predictions about the outcomes of those experiments.

- In social science research , hypotheses are used to test theories about human behavior, social relationships, and other phenomena.

- I n business , hypotheses can be used to guide decisions about marketing, product development, and other areas. For example, a hypothesis might be that a new product will sell well in a particular market, and this hypothesis can be tested through market research.

Characteristics of Hypothesis

Here are some common characteristics of a hypothesis:

- Testable : A hypothesis must be able to be tested through observation or experimentation. This means that it must be possible to collect data that will either support or refute the hypothesis.

- Falsifiable : A hypothesis must be able to be proven false if it is not supported by the data. If a hypothesis cannot be falsified, then it is not a scientific hypothesis.

- Clear and concise : A hypothesis should be stated in a clear and concise manner so that it can be easily understood and tested.

- Based on existing knowledge : A hypothesis should be based on existing knowledge and research in the field. It should not be based on personal beliefs or opinions.

- Specific : A hypothesis should be specific in terms of the variables being tested and the predicted outcome. This will help to ensure that the research is focused and well-designed.

- Tentative: A hypothesis is a tentative statement or assumption that requires further testing and evidence to be confirmed or refuted. It is not a final conclusion or assertion.

- Relevant : A hypothesis should be relevant to the research question or problem being studied. It should address a gap in knowledge or provide a new perspective on the issue.

Advantages of Hypothesis

Hypotheses have several advantages in scientific research and experimentation:

- Guides research: A hypothesis provides a clear and specific direction for research. It helps to focus the research question, select appropriate methods and variables, and interpret the results.

- Predictive powe r: A hypothesis makes predictions about the outcome of research, which can be tested through experimentation. This allows researchers to evaluate the validity of the hypothesis and make new discoveries.

- Facilitates communication: A hypothesis provides a common language and framework for scientists to communicate with one another about their research. This helps to facilitate the exchange of ideas and promotes collaboration.

- Efficient use of resources: A hypothesis helps researchers to use their time, resources, and funding efficiently by directing them towards specific research questions and methods that are most likely to yield results.

- Provides a basis for further research: A hypothesis that is supported by data provides a basis for further research and exploration. It can lead to new hypotheses, theories, and discoveries.

- Increases objectivity: A hypothesis can help to increase objectivity in research by providing a clear and specific framework for testing and interpreting results. This can reduce bias and increase the reliability of research findings.

Limitations of Hypothesis

Some Limitations of the Hypothesis are as follows:

- Limited to observable phenomena: Hypotheses are limited to observable phenomena and cannot account for unobservable or intangible factors. This means that some research questions may not be amenable to hypothesis testing.

- May be inaccurate or incomplete: Hypotheses are based on existing knowledge and research, which may be incomplete or inaccurate. This can lead to flawed hypotheses and erroneous conclusions.

- May be biased: Hypotheses may be biased by the researcher’s own beliefs, values, or assumptions. This can lead to selective interpretation of data and a lack of objectivity in research.

- Cannot prove causation: A hypothesis can only show a correlation between variables, but it cannot prove causation. This requires further experimentation and analysis.

- Limited to specific contexts: Hypotheses are limited to specific contexts and may not be generalizable to other situations or populations. This means that results may not be applicable in other contexts or may require further testing.

- May be affected by chance : Hypotheses may be affected by chance or random variation, which can obscure or distort the true relationship between variables.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Data Collection – Methods Types and Examples

Delimitations in Research – Types, Examples and...

Research Process – Steps, Examples and Tips

Research Design – Types, Methods and Examples

Institutional Review Board – Application Sample...

Evaluating Research – Process, Examples and...

What is a scientific hypothesis?

It's the initial building block in the scientific method.

Hypothesis basics

What makes a hypothesis testable.

- Types of hypotheses

- Hypothesis versus theory

Additional resources

Bibliography.

A scientific hypothesis is a tentative, testable explanation for a phenomenon in the natural world. It's the initial building block in the scientific method . Many describe it as an "educated guess" based on prior knowledge and observation. While this is true, a hypothesis is more informed than a guess. While an "educated guess" suggests a random prediction based on a person's expertise, developing a hypothesis requires active observation and background research.

The basic idea of a hypothesis is that there is no predetermined outcome. For a solution to be termed a scientific hypothesis, it has to be an idea that can be supported or refuted through carefully crafted experimentation or observation. This concept, called falsifiability and testability, was advanced in the mid-20th century by Austrian-British philosopher Karl Popper in his famous book "The Logic of Scientific Discovery" (Routledge, 1959).

A key function of a hypothesis is to derive predictions about the results of future experiments and then perform those experiments to see whether they support the predictions.

A hypothesis is usually written in the form of an if-then statement, which gives a possibility (if) and explains what may happen because of the possibility (then). The statement could also include "may," according to California State University, Bakersfield .

Here are some examples of hypothesis statements:

- If garlic repels fleas, then a dog that is given garlic every day will not get fleas.

- If sugar causes cavities, then people who eat a lot of candy may be more prone to cavities.

- If ultraviolet light can damage the eyes, then maybe this light can cause blindness.

A useful hypothesis should be testable and falsifiable. That means that it should be possible to prove it wrong. A theory that can't be proved wrong is nonscientific, according to Karl Popper's 1963 book " Conjectures and Refutations ."

An example of an untestable statement is, "Dogs are better than cats." That's because the definition of "better" is vague and subjective. However, an untestable statement can be reworded to make it testable. For example, the previous statement could be changed to this: "Owning a dog is associated with higher levels of physical fitness than owning a cat." With this statement, the researcher can take measures of physical fitness from dog and cat owners and compare the two.

Types of scientific hypotheses

In an experiment, researchers generally state their hypotheses in two ways. The null hypothesis predicts that there will be no relationship between the variables tested, or no difference between the experimental groups. The alternative hypothesis predicts the opposite: that there will be a difference between the experimental groups. This is usually the hypothesis scientists are most interested in, according to the University of Miami .

For example, a null hypothesis might state, "There will be no difference in the rate of muscle growth between people who take a protein supplement and people who don't." The alternative hypothesis would state, "There will be a difference in the rate of muscle growth between people who take a protein supplement and people who don't."

If the results of the experiment show a relationship between the variables, then the null hypothesis has been rejected in favor of the alternative hypothesis, according to the book " Research Methods in Psychology " (BCcampus, 2015).

There are other ways to describe an alternative hypothesis. The alternative hypothesis above does not specify a direction of the effect, only that there will be a difference between the two groups. That type of prediction is called a two-tailed hypothesis. If a hypothesis specifies a certain direction — for example, that people who take a protein supplement will gain more muscle than people who don't — it is called a one-tailed hypothesis, according to William M. K. Trochim , a professor of Policy Analysis and Management at Cornell University.

Sometimes, errors take place during an experiment. These errors can happen in one of two ways. A type I error is when the null hypothesis is rejected when it is true. This is also known as a false positive. A type II error occurs when the null hypothesis is not rejected when it is false. This is also known as a false negative, according to the University of California, Berkeley .

A hypothesis can be rejected or modified, but it can never be proved correct 100% of the time. For example, a scientist can form a hypothesis stating that if a certain type of tomato has a gene for red pigment, that type of tomato will be red. During research, the scientist then finds that each tomato of this type is red. Though the findings confirm the hypothesis, there may be a tomato of that type somewhere in the world that isn't red. Thus, the hypothesis is true, but it may not be true 100% of the time.

Scientific theory vs. scientific hypothesis

The best hypotheses are simple. They deal with a relatively narrow set of phenomena. But theories are broader; they generally combine multiple hypotheses into a general explanation for a wide range of phenomena, according to the University of California, Berkeley . For example, a hypothesis might state, "If animals adapt to suit their environments, then birds that live on islands with lots of seeds to eat will have differently shaped beaks than birds that live on islands with lots of insects to eat." After testing many hypotheses like these, Charles Darwin formulated an overarching theory: the theory of evolution by natural selection.

"Theories are the ways that we make sense of what we observe in the natural world," Tanner said. "Theories are structures of ideas that explain and interpret facts."

- Read more about writing a hypothesis, from the American Medical Writers Association.

- Find out why a hypothesis isn't always necessary in science, from The American Biology Teacher.

- Learn about null and alternative hypotheses, from Prof. Essa on YouTube .

Encyclopedia Britannica. Scientific Hypothesis. Jan. 13, 2022. https://www.britannica.com/science/scientific-hypothesis

Karl Popper, "The Logic of Scientific Discovery," Routledge, 1959.

California State University, Bakersfield, "Formatting a testable hypothesis." https://www.csub.edu/~ddodenhoff/Bio100/Bio100sp04/formattingahypothesis.htm

Karl Popper, "Conjectures and Refutations," Routledge, 1963.

Price, P., Jhangiani, R., & Chiang, I., "Research Methods of Psychology — 2nd Canadian Edition," BCcampus, 2015.

University of Miami, "The Scientific Method" http://www.bio.miami.edu/dana/161/evolution/161app1_scimethod.pdf

William M.K. Trochim, "Research Methods Knowledge Base," https://conjointly.com/kb/hypotheses-explained/

University of California, Berkeley, "Multiple Hypothesis Testing and False Discovery Rate" https://www.stat.berkeley.edu/~hhuang/STAT141/Lecture-FDR.pdf

University of California, Berkeley, "Science at multiple levels" https://undsci.berkeley.edu/article/0_0_0/howscienceworks_19

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

AI-powered 'digital twin' of Earth could make weather predictions at super speeds

Part of the San Andreas fault may be gearing up for an earthquake

'Vampire' bacteria thirst for human blood — and cause deadly infections as they feed

Most Popular

- 2 NASA spacecraft snaps mysterious 'surfboard' orbiting the moon. What is it?

- 3 'Gambling with your life': Experts weigh in on dangers of the Wim Hof method

- 4 Viking Age women with cone-shaped skulls likely learned head-binding practice from far-flung region

- 5 'Exceptional' prosthesis of gold, silver and wool helped 18th-century man live with cleft palate

- 2 AI pinpoints where psychosis originates in the brain

- 3 NASA's downed Ingenuity helicopter has a 'last gift' for humanity — but we'll have to go to Mars to get it

- 4 Anglerfish entered the midnight zone 55 million years ago and thrived by becoming sexual parasites

- 5 2,500-year-old skeletons with legs chopped off may be elites who received 'cruel' punishment in ancient China

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- How to Write a Strong Hypothesis | Steps & Examples

How to Write a Strong Hypothesis | Steps & Examples

Published on May 6, 2022 by Shona McCombes . Revised on November 20, 2023.

A hypothesis is a statement that can be tested by scientific research. If you want to test a relationship between two or more variables, you need to write hypotheses before you start your experiment or data collection .

Example: Hypothesis

Daily apple consumption leads to fewer doctor’s visits.

Table of contents

What is a hypothesis, developing a hypothesis (with example), hypothesis examples, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about writing hypotheses.

A hypothesis states your predictions about what your research will find. It is a tentative answer to your research question that has not yet been tested. For some research projects, you might have to write several hypotheses that address different aspects of your research question.

A hypothesis is not just a guess – it should be based on existing theories and knowledge. It also has to be testable, which means you can support or refute it through scientific research methods (such as experiments, observations and statistical analysis of data).

Variables in hypotheses

Hypotheses propose a relationship between two or more types of variables .

- An independent variable is something the researcher changes or controls.

- A dependent variable is something the researcher observes and measures.

If there are any control variables , extraneous variables , or confounding variables , be sure to jot those down as you go to minimize the chances that research bias will affect your results.

In this example, the independent variable is exposure to the sun – the assumed cause . The dependent variable is the level of happiness – the assumed effect .

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

Step 1. Ask a question

Writing a hypothesis begins with a research question that you want to answer. The question should be focused, specific, and researchable within the constraints of your project.

Step 2. Do some preliminary research

Your initial answer to the question should be based on what is already known about the topic. Look for theories and previous studies to help you form educated assumptions about what your research will find.

At this stage, you might construct a conceptual framework to ensure that you’re embarking on a relevant topic . This can also help you identify which variables you will study and what you think the relationships are between them. Sometimes, you’ll have to operationalize more complex constructs.

Step 3. Formulate your hypothesis

Now you should have some idea of what you expect to find. Write your initial answer to the question in a clear, concise sentence.

4. Refine your hypothesis

You need to make sure your hypothesis is specific and testable. There are various ways of phrasing a hypothesis, but all the terms you use should have clear definitions, and the hypothesis should contain:

- The relevant variables

- The specific group being studied

- The predicted outcome of the experiment or analysis

5. Phrase your hypothesis in three ways

To identify the variables, you can write a simple prediction in if…then form. The first part of the sentence states the independent variable and the second part states the dependent variable.

In academic research, hypotheses are more commonly phrased in terms of correlations or effects, where you directly state the predicted relationship between variables.

If you are comparing two groups, the hypothesis can state what difference you expect to find between them.

6. Write a null hypothesis

If your research involves statistical hypothesis testing , you will also have to write a null hypothesis . The null hypothesis is the default position that there is no association between the variables. The null hypothesis is written as H 0 , while the alternative hypothesis is H 1 or H a .

- H 0 : The number of lectures attended by first-year students has no effect on their final exam scores.

- H 1 : The number of lectures attended by first-year students has a positive effect on their final exam scores.

If you want to know more about the research process , methodology , research bias , or statistics , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Sampling methods

- Simple random sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Cluster sampling

- Likert scales

- Reproducibility

Statistics

- Null hypothesis

- Statistical power

- Probability distribution

- Effect size

- Poisson distribution

Research bias

- Optimism bias

- Cognitive bias

- Implicit bias

- Hawthorne effect

- Anchoring bias

- Explicit bias

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

A hypothesis is not just a guess — it should be based on existing theories and knowledge. It also has to be testable, which means you can support or refute it through scientific research methods (such as experiments, observations and statistical analysis of data).

Null and alternative hypotheses are used in statistical hypothesis testing . The null hypothesis of a test always predicts no effect or no relationship between variables, while the alternative hypothesis states your research prediction of an effect or relationship.

Hypothesis testing is a formal procedure for investigating our ideas about the world using statistics. It is used by scientists to test specific predictions, called hypotheses , by calculating how likely it is that a pattern or relationship between variables could have arisen by chance.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, November 20). How to Write a Strong Hypothesis | Steps & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved April 17, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/hypothesis/

Is this article helpful?

The Scientific Method Tutorial

The scientific method, steps in the scientific method.

There is a great deal of variation in the specific techniques scientists use explore the natural world. However, the following steps characterize the majority of scientific investigations:

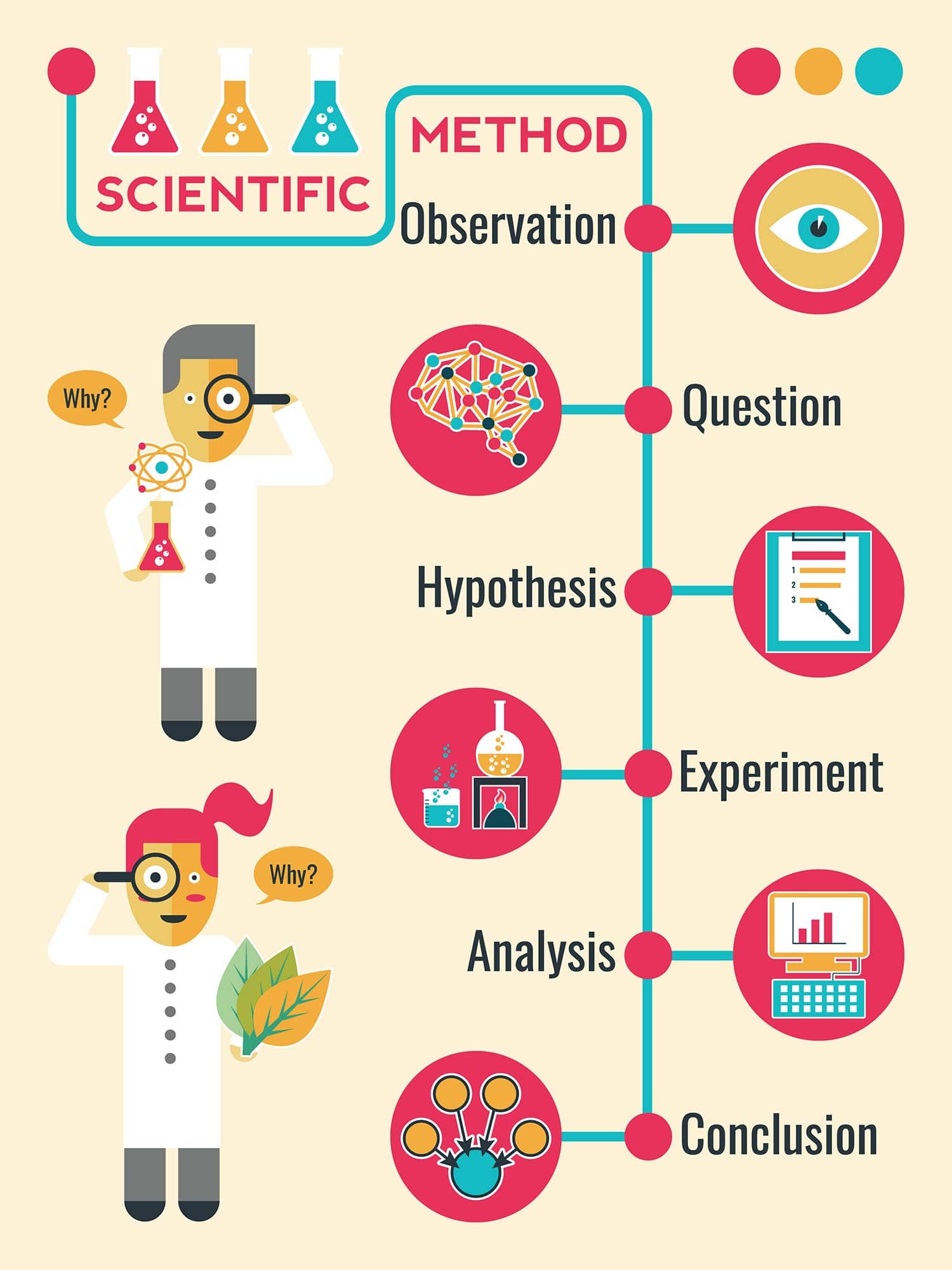

Step 1: Make observations Step 2: Propose a hypothesis to explain observations Step 3: Test the hypothesis with further observations or experiments Step 4: Analyze data Step 5: State conclusions about hypothesis based on data analysis

Each of these steps is explained briefly below, and in more detail later in this section.

Step 1: Make observations

A scientific inquiry typically starts with observations. Often, simple observations will trigger a question in the researcher's mind.

Example: A biologist frequently sees monarch caterpillars feeding on milkweed plants, but rarely sees them feeding on other types of plants. She wonders if it is because the caterpillars prefer milkweed over other food choices.

Step 2: Propose a hypothesis

The researcher develops a hypothesis (singular) or hypotheses (plural) to explain these observations. A hypothesis is a tentative explanation of a phenomenon or observation(s) that can be supported or falsified by further observations or experimentation.

Example: The researcher hypothesizes that monarch caterpillars prefer to feed on milkweed compared to other common plants. (Notice how the hypothesis is a statement, not a question as in step 1.)

Step 3: Test the hypothesis

The researcher makes further observations and/or may design an experiment to test the hypothesis. An experiment is a controlled situation created by a researcher to test the validity of a hypothesis. Whether further observations or an experiment is used to test the hypothesis will depend on the nature of the question and the practicality of manipulating the factors involved.

Example: The researcher sets up an experiment in the lab in which a number of monarch caterpillars are given a choice between milkweed and a number of other common plants to feed on.

Step 4: Analyze data

The researcher summarizes and analyzes the information, or data, generated by these further observations or experiments.

Example: In her experiment, milkweed was chosen by caterpillars 9 times out of 10 over all other plant selections.

Step 5: State conclusions

The researcher interprets the results of experiments or observations and forms conclusions about the meaning of these results. These conclusions are generally expressed as probability statements about their hypothesis.

Example: She concludes that when given a choice, 90 percent of monarch caterpillars prefer to feed on milkweed over other common plants.

Often, the results of one scientific study will raise questions that may be addressed in subsequent research. For example, the above study might lead the researcher to wonder why monarchs seem to prefer to feed on milkweed, and she may plan additional experiments to explore this question. For example, perhaps the milkweed has higher nutritional value than other available plants.

Return to top of page

The Scientific Method Flowchart

The steps in the scientific method are presented visually in the following flow chart. The question raised or the results obtained at each step directly determine how the next step will proceed. Following the flow of the arrows, pass the cursor over each blue box. An explanation and example of each step will appear. As you read the example given at each step, see if you can predict what the next step will be.

Activity: Apply the Scientific Method to Everyday Life Use the steps of the scientific method described above to solve a problem in real life. Suppose you come home one evening and flick the light switch only to find that the light doesn’t turn on. What is your hypothesis? How will you test that hypothesis? Based on the result of this test, what are your conclusions? Follow your instructor's directions for submitting your response.

The above flowchart illustrates the logical sequence of conclusions and decisions in a typical scientific study. There are some important points to note about this process:

1. The steps are clearly linked.

The steps in this process are clearly linked. The hypothesis, formed as a potential explanation for the initial observations, becomes the focus of the study. The hypothesis will determine what further observations are needed or what type of experiment should be done to test its validity. The conclusions of the experiment or further observations will either be in agreement with or will contradict the hypothesis. If the results are in agreement with the hypothesis, this does not prove that the hypothesis is true! In scientific terms, it "lends support" to the hypothesis, which will be tested again and again under a variety of circumstances before researchers accept it as a fairly reliable description of reality.

2. The same steps are not followed in all types of research.

The steps described above present a generalized method followed in a many scientific investigations. These steps are not carved in stone. The question the researcher wishes to answer will influence the steps in the method and how they will be carried out. For example, astronomers do not perform many experiments as defined here. They tend to rely on observations to test theories. Biologists and chemists have the ability to change conditions in a test tube and then observe whether the outcome supports or invalidates their starting hypothesis, while astronomers are not able to change the path of Jupiter around the Sun and observe the outcome!

3. Collected observations may lead to the development of theories.

When a large number of observations and/or experimental results have been compiled, and all are consistent with a generalized description of how some element of nature operates, this description is called a theory. Theories are much broader than hypotheses and are supported by a wide range of evidence. Theories are important scientific tools. They provide a context for interpretation of new observations and also suggest experiments to test their own validity. Theories are discussed in more detail in another section.

The Scientific Method in Detail

In the sections that follow, each step in the scientific method is described in more detail.

Step 1: Observations

Observations in science.

An observation is some thing, event, or phenomenon that is noticed or observed. Observations are listed as the first step in the scientific method because they often provide a starting point, a source of questions a researcher may ask. For example, the observation that leaves change color in the fall may lead a researcher to ask why this is so, and to propose a hypothesis to explain this phenomena. In fact, observations also will provide the key to answering the research question.

In science, observations form the foundation of all hypotheses, experiments, and theories. In an experiment, the researcher carefully plans what observations will be made and how they will be recorded. To be accepted, scientific conclusions and theories must be supported by all available observations. If new observations are made which seem to contradict an established theory, that theory will be re-examined and may be revised to explain the new facts. Observations are the nuts and bolts of science that researchers use to piece together a better understanding of nature.

Observations in science are made in a way that can be precisely communicated to (and verified by) other researchers. In many types of studies (especially in chemistry, physics, and biology), quantitative observations are used. A quantitative observation is one that is expressed and recorded as a quantity, using some standard system of measurement. Quantities such as size, volume, weight, time, distance, or a host of others may be measured in scientific studies.

Some observations that researchers need to make may be difficult or impossible to quantify. Take the example of color. Not all individuals perceive color in exactly the same way. Even apart from limiting conditions such as colorblindness, the way two people see and describe the color of a particular flower, for example, will not be the same. Color, as perceived by the human eye, is an example of a qualitative observation.

Qualitative observations note qualities associated with subjects or samples that are not readily measured. Other examples of qualitative observations might be descriptions of mating behaviors, human facial expressions, or "yes/no" type of data, where some factor is present or absent. Though the qualities of an object may be more difficult to describe or measure than any quantities associated with it, every attempt is made to minimize the effects of the subjective perceptions of the researcher in the process. Some types of studies, such as those in the social and behavioral sciences (which deal with highly variable human subjects), may rely heavily on qualitative observations.

Question: Why are observations important to science?

Limits of Observations

Because all observations rely to some degree on the senses (eyes, ears, or steady hand) of the researcher, complete objectivity is impossible. Our human perceptions are limited by the physical abilities of our sense organs and are interpreted according to our understanding of how the world works, which can be influenced by culture, experience, or education. According to science education specialist, George F. Kneller, "Surprising as it may seem, there is no fact that is not colored by our preconceptions" ("A Method of Enquiry," from Science and Its Ways of Knowing [Upper Saddle River: Prentice-Hall Inc., 1997], 15).

Observations made by a scientist are also limited by the sensitivity of whatever equipment he is using. Research findings will be limited at times by the available technology. For example, Italian physicist and philosopher Galileo Galilei (1564–1642) was reportedly the first person to observe the heavens with a telescope. Imagine how it must have felt to him to see the heavens through this amazing new instrument! It opened a window to the stars and planets and allowed new observations undreamed of before.

In the centuries since Galileo, increasingly more powerful telescopes have been devised that dwarf the power of that first device. In the past decade, we have marveled at images from deep space , courtesy of the Hubble Space Telescope, a large telescope that orbits Earth. Because of its view from outside the distorting effects of the atmosphere, the Hubble can look 50 times farther into space than the best earth-bound telescopes, and resolve details a tenth of the size (Seeds, Michael A., Horizons: Exploring the Universe , 5 th ed. [Belmont: Wadsworth Publishing Company, 1998], 86-87).

Construction is underway on a new radio telescope that scientists say will be able to detect electromagnetic waves from the very edges of the universe! This joint U.S.-Mexican project may allow us to ask questions about the origins of the universe and the beginnings of time that we could never have hoped to answer before. Completion of the new telescope is expected by the end of 2001.

Although the amount of detail observed by Galileo and today's astronomers is vastly different, the stars and their relationships have not changed very much. Yet with each technological advance, the level of detail of observation has been increased, and with it, the power to answer more and more challenging questions with greater precision.

Question: What are some of the differences between a casual observation and a 'scientific observation'?

Step 2: The Hypothesis

A hypothesis is a statement created by the researcher as a potential explanation for an observation or phenomena. The hypothesis converts the researcher's original question into a statement that can be used to make predictions about what should be observed if the hypothesis is true. For example, given the hypothesis, "exposure to ultraviolet (UV) radiation increases the risk of skin cancer," one would predict higher rates of skin cancer among people with greater UV exposure. These predictions could be tested by comparing skin cancer rates among individuals with varying amounts of UV exposure. Note how the hypothesis itself determines what experiments or further observations should be made to test its validity. Results of tests are then compared to predictions from the hypothesis, and conclusions are stated in terms of whether or not the data supports the hypothesis. So the hypothesis serves a guide to the full process of scientific inquiry.

The Qualities of a Good Hypothesis

- A hypothesis must be testable or provide predictions that are testable. It can potentially be shown to be false by further observations or experimentation.

- A hypothesis should be specific. If it is too general it cannot be tested, or tests will have so many variables that the results will be complicated and difficult to interpret. A well-written hypothesis is so specific it actually determines how the experiment should be set up.

- A hypothesis should not include any untested assumptions if they can be avoided. The hypothesis itself may be an assumption that is being tested, but it should be phrased in a way that does not include assumptions that are not tested in the experiment.

- It is okay (and sometimes a good idea) to develop more than one hypothesis to explain a set of observations. Competing hypotheses can often be tested side-by-side in the same experiment.

Question: Why is the hypothesis important to the scientific method?

Step 3: Testing the Hypothesis

A hypothesis may be tested in one of two ways: by making additional observations of a natural situation, or by setting up an experiment. In either case, the hypothesis is used to make predictions, and the observations or experimental data collected are examined to determine if they are consistent or inconsistent with those predictions. Hypothesis testing, especially through experimentation, is at the core of the scientific process. It is how scientists gain a better understanding of how things work.

Testing a Hypothesis by Observation

Some hypotheses may be tested through simple observation. For example, a researcher may formulate the hypothesis that the sun always rises in the east. What might an alternative hypothesis be? If his hypothesis is correct, he would predict that the sun will rise in the east tomorrow. He can easily test such a prediction by rising before dawn and going out to observe the sunrise. If the sun rises in the west, he will have disproved the hypothesis. He will have shown that it does not hold true in every situation. However, if he observes on that morning that the sun does in fact rise in the east, he has not proven the hypothesis. He has made a single observation that is consistent with, or supports, the hypothesis. As a scientist, to confidently state that the sun will always rise in the east, he will want to make many observations, under a variety of circumstances. Note that in this instance no manipulation of circumstance is required to test the hypothesis (i.e., you aren't altering the sun in any way).

Testing a Hypothesis by Experimentation

An experiment is a controlled series of observations designed to test a specific hypothesis. In an experiment, the researcher manipulates factors related to the hypothesis in such a way that the effect of these factors on the observations (data) can be readily measured and compared. Most experiments are an attempt to define a cause-and-effect relationship between two factors or events—to explain why something happens. For example, with the hypothesis "roses planted in sunny areas bloom earlier than those grown in shady areas," the experiment would be testing a cause-and-effect relationship between sunlight and time of blooming.

A major advantage of setting up an experiment versus making observations of what is already available is that it allows the researcher to control all the factors or events related to the hypothesis, so that the true cause of an event can be more easily isolated. In all cases, the hypothesis itself will determine the way the experiment will be set up. For example, suppose my hypothesis is "the weight of an object is proportional to the amount of time it takes to fall a certain distance." How would you test this hypothesis?

The Qualities of a Good Experiment

- The experiment must be conducted on a group of subjects that are narrowly defined and have certain aspects in common. This is the group to which any conclusions must later be confined. (Examples of possible subjects: female cancer patients over age 40, E. coli bacteria, red giant stars, the nicotine molecule and its derivatives.)

- All subjects of the experiment should be (ideally) completely alike in all ways except for the factor or factors that are being tested. Factors that are compared in scientific experiments are called variables. A variable is some aspect of a subject or event that may differ over time or from one group of subjects to another. For example, if a biologist wanted to test the effect of nitrogen on grass growth, he would apply different amounts of nitrogen fertilizer to several plots of grass. The grass in each of the plots should be as alike as possible so that any difference in growth could be attributed to the effect of the nitrogen. For example, all the grass should be of the same species, planted at the same time and at the same density, receive the same amount of water and sunlight, and so on. The variable in this case would be the amount of nitrogen applied to the plants. The researcher would not compare differing amounts of nitrogen across different grass species to determine the effect of nitrogen on grass growth. What is the problem with using different species of plants to compare the effect of nitrogen on plant growth? There are different kinds of variables in an experiment. A factor that the experimenter controls, and changes intentionally to determine if it has an effect, is called an independent variable . A factor that is recorded as data in the experiment, and which is compared across different groups of subjects, is called a dependent variable . In many cases, the value of the dependent variable will be influenced by the value of an independent variable. The goal of the experiment is to determine a cause-and-effect relationship between independent and dependent variables—in this case, an effect of nitrogen on plant growth. In the nitrogen/grass experiment, (1) which factor was the independent variable? (2) Which factor was the dependent variable?

- Nearly all types of experiments require a control group and an experimental group. The control group generally is not changed in any way, but remains in a "natural state," while the experimental group is modified in some way to examine the effect of the variable which of interest to the researcher. The control group provides a standard of comparison for the experimental groups. For example, in new drug trials, some patients are given a placebo while others are given doses of the drug being tested. The placebo serves as a control by showing the effect of no drug treatment on the patients. In research terminology, the experimental groups are often referred to as treatments , since each group is treated differently. In the experimental test of the effect of nitrogen on grass growth, what is the control group? In the example of the nitrogen experiment, what is the purpose of a control group?

- In research studies a great deal of emphasis is placed on repetition. It is essential that an experiment or study include enough subjects or enough observations for the researcher to make valid conclusions. The two main reasons why repetition is important in scientific studies are (1) variation among subjects or samples and (2) measurement error.

Variation among Subjects

There is a great deal of variation in nature. In a group of experimental subjects, much of this variation may have little to do with the variables being studied, but could still affect the outcome of the experiment in unpredicted ways. For example, in an experiment designed to test the effects of alcohol dose levels on reflex time in 18- to 22-year-old males, there would be significant variation among individual responses to various doses of alcohol. Some of this variation might be due to differences in genetic make-up, to varying levels of previous alcohol use, or any number of factors unknown to the researcher.

Because what the researcher wants to discover is average dose level effects for this group, he must run the test on a number of different subjects. Suppose he performed the test on only 10 individuals. Do you think the average response calculated would be the same as the average response of all 18- to 22-year-old males? What if he tests 100 individuals, or 1,000? Do you think the average he comes up with would be the same in each case? Chances are it would not be. So which average would you predict would be most representative of all 18- to 22-year-old males?

A basic rule of statistics is, the more observations you make, the closer the average of those observations will be to the average for the whole population you are interested in. This is because factors that vary among a population tend to occur most commonly in the middle range, and least commonly at the two extremes. Take human height for example. Although you may find a man who is 7 feet tall, or one who is 4 feet tall, most men will fall somewhere between 5 and 6 feet in height. The more men we measure to determine average male height, the less effect those uncommon extreme (tall or short) individuals will tend to impact the average. Thus, one reason why repetition is so important in experiments is that it helps to assure that the conclusions made will be valid not only for the individuals tested, but also for the greater population those individuals represent.

"The use of a sample (or subset) of a population, an event, or some other aspect of nature for an experimental group that is not large enough to be representative of the whole" is called sampling error (Starr, Cecie, Biology: Concepts and Applications , 4 th ed. [Pacific Cove: Brooks/Cole, 2000], glossary). If too few samples or subjects are used in an experiment, the researcher may draw incorrect conclusions about the population those samples or subjects represent.

Use the jellybean activity below to see a simple demonstration of samping error.

Directions: There are 400 jellybeans in the jar. If you could not see the jar and you initially chose 1 green jellybean from the jar, you might assume the jar only contains green jelly beans. The jar actually contains both green and black jellybeans. Use the "pick 1, 5, or 10" buttons to create your samples. For example, use the "pick" buttons now to create samples of 2, 13, and 27 jellybeans. After you take each sample, try to predict the ratio of green to black jellybeans in the jar. How does your prediction of the ratio of green to black jellybeans change as your sample changes?

Measurement Error

The second reason why repetition is necessary in research studies has to do with measurement error. Measurement error may be the fault of the researcher, a slight difference in measuring techniques among one or more technicians, or the result of limitations or glitches in measuring equipment. Even the most careful researcher or the best state-of-the-art equipment will make some mistakes in measuring or recording data. Another way of looking at this is to say that, in any study, some measurements will be more accurate than others will. If the researcher is conscientious and the equipment is good, the majority of measurements will be highly accurate, some will be somewhat inaccurate, and a few may be considerably inaccurate. In this case, the same reasoning used above also applies here: the more measurements taken, the less effect a few inaccurate measurements will have on the overall average.

Step 4: Data Analysis

In any experiment, observations are made, and often, measurements are taken. Measurements and observations recorded in an experiment are referred to as data . The data collected must relate to the hypothesis being tested. Any differences between experimental and control groups must be expressed in some way (often quantitatively) so that the groups may be compared. Graphs and charts are often used to visualize the data and to identify patterns and relationships among the variables.

Statistics is the branch of mathematics that deals with interpretation of data. Data analysis refers to statistical methods of determining whether any differences between the control group and experimental groups are too great to be attributed to chance alone. Although a discussion of statistical methods is beyond the scope of this tutorial, the data analysis step is crucial because it provides a somewhat standardized means for interpreting data. The statistical methods of data analysis used, and the results of those analyses, are always included in the publication of scientific research. This convention limits the subjective aspects of data interpretation and allows scientists to scrutinize the working methods of their peers.

Why is data analysis an important step in the scientific method?

Step 5: Stating Conclusions

The conclusions made in a scientific experiment are particularly important. Often, the conclusion is the only part of a study that gets communicated to the general public. As such, it must be a statement of reality, based upon the results of the experiment. To assure that this is the case, the conclusions made in an experiment must (1) relate back to the hypothesis being tested, (2) be limited to the population under study, and (3) be stated as probabilities.

The hypothesis that is being tested will be compared to the data collected in the experiment. If the experimental results contradict the hypothesis, it is rejected and further testing of that hypothesis under those conditions is not necessary. However, if the hypothesis is not shown to be wrong, that does not conclusively prove that it is right! In scientific terms, the hypothesis is said to be "supported by the data." Further testing will be done to see if the hypothesis is supported under a number of trials and under different conditions.

If the hypothesis holds up to extensive testing then the temptation is to claim that it is correct. However, keep in mind that the number of experiments and observations made will only represent a subset of all the situations in which the hypothesis may potentially be tested. In other words, experimental data will only show part of the picture. There is always the possibility that a further experiment may show the hypothesis to be wrong in some situations. Also, note that the limits of current knowledge and available technologies may prevent a researcher from devising an experiment that would disprove a particular hypothesis.

The researcher must be sure to limit his or her conclusions to apply only to the subjects tested in the study. If a particular species of fish is shown to consume their young 90 percent of the time when raised in captivity, that doesn't necessarily mean that all fish will do so, or that this fish's behavior would be the same in its native habitat.

Finally, the conclusions of the experiment are generally stated as probabilities. A careful scientist would never say, "drug x kills cancer cells;" she would more likely say, "drug x was shown to destroy 85 percent of cancerous skin cells in rats in lab trials." Notice how very different these two statements are. There is a tendency in the media and in the general public to gravitate toward the first statement. This makes a terrific headline and is also easy to interpret; it is absolute. Remember though, in science conclusions must be confined to the population under study; broad generalizations should be avoided. The second statement is sound science. There is data to back it up. Later studies may reveal a more universal effect of the drug on cancerous cells, or they may not. Most researchers would be unwilling to stake their reputations on the first statement.

As a student, you should read and interpret popular press articles about research studies very carefully. From the text, can you determine how the experiment was set up and what variables were measured? Are the observations and data collected appropriate to the hypothesis being tested? Are the conclusions supported by the data? Are the conclusions worded in a scientific context (as probability statements) or are they generalized for dramatic effect? In any researched-based assignment, it is a good idea to refer to the original publication of a study (usually found in professional journals) and to interpret the facts for yourself.

Qualities of a Good Experiment

- narrowly defined subjects

- all subjects treated alike except for the factor or variable being studied

- a control group is used for comparison

- measurements related to the factors being studied are carefully recorded

- enough samples or subjects are used so that conclusions are valid for the population of interest

- conclusions made relate back to the hypothesis, are limited to the population being studied, and are stated in terms of probabilities

1.2 The Scientific Methods

Section learning objectives.

By the end of this section, you will be able to do the following:

- Explain how the methods of science are used to make scientific discoveries

- Define a scientific model and describe examples of physical and mathematical models used in physics

- Compare and contrast hypothesis, theory, and law

Teacher Support

The learning objectives in this section will help your students master the following standards:

- (A) know the definition of science and understand that it has limitations, as specified in subsection (b)(2) of this section;

- (B) know that scientific hypotheses are tentative and testable statements that must be capable of being supported or not supported by observational evidence. Hypotheses of durable explanatory power which have been tested over a wide variety of conditions are incorporated into theories;

- (C) know that scientific theories are based on natural and physical phenomena and are capable of being tested by multiple independent researchers. Unlike hypotheses, scientific theories are well-established and highly-reliable explanations, but may be subject to change as new areas of science and new technologies are developed;

- (D) distinguish between scientific hypotheses and scientific theories.

Section Key Terms

[OL] Pre-assessment for this section could involve students sharing or writing down an anecdote about when they used the methods of science. Then, students could label their thought processes in their anecdote with the appropriate scientific methods. The class could also discuss their definitions of theory and law, both outside and within the context of science.

[OL] It should be noted and possibly mentioned that a scientist , as mentioned in this section, does not necessarily mean a trained scientist. It could be anyone using methods of science.

Scientific Methods

Scientists often plan and carry out investigations to answer questions about the universe around us. These investigations may lead to natural laws. Such laws are intrinsic to the universe, meaning that humans did not create them and cannot change them. We can only discover and understand them. Their discovery is a very human endeavor, with all the elements of mystery, imagination, struggle, triumph, and disappointment inherent in any creative effort. The cornerstone of discovering natural laws is observation. Science must describe the universe as it is, not as we imagine or wish it to be.

We all are curious to some extent. We look around, make generalizations, and try to understand what we see. For example, we look up and wonder whether one type of cloud signals an oncoming storm. As we become serious about exploring nature, we become more organized and formal in collecting and analyzing data. We attempt greater precision, perform controlled experiments (if we can), and write down ideas about how data may be organized. We then formulate models, theories, and laws based on the data we have collected, and communicate those results with others. This, in a nutshell, describes the scientific method that scientists employ to decide scientific issues on the basis of evidence from observation and experiment.

An investigation often begins with a scientist making an observation . The scientist observes a pattern or trend within the natural world. Observation may generate questions that the scientist wishes to answer. Next, the scientist may perform some research about the topic and devise a hypothesis . A hypothesis is a testable statement that describes how something in the natural world works. In essence, a hypothesis is an educated guess that explains something about an observation.

[OL] An educated guess is used throughout this section in describing a hypothesis to combat the tendency to think of a theory as an educated guess.

Scientists may test the hypothesis by performing an experiment . During an experiment, the scientist collects data that will help them learn about the phenomenon they are studying. Then the scientists analyze the results of the experiment (that is, the data), often using statistical, mathematical, and/or graphical methods. From the data analysis, they draw conclusions. They may conclude that their experiment either supports or rejects their hypothesis. If the hypothesis is supported, the scientist usually goes on to test another hypothesis related to the first. If their hypothesis is rejected, they will often then test a new and different hypothesis in their effort to learn more about whatever they are studying.

Scientific processes can be applied to many situations. Let’s say that you try to turn on your car, but it will not start. You have just made an observation! You ask yourself, "Why won’t my car start?" You can now use scientific processes to answer this question. First, you generate a hypothesis such as, "The car won’t start because it has no gasoline in the gas tank." To test this hypothesis, you put gasoline in the car and try to start it again. If the car starts, then your hypothesis is supported by the experiment. If the car does not start, then your hypothesis is rejected. You will then need to think up a new hypothesis to test such as, "My car won’t start because the fuel pump is broken." Hopefully, your investigations lead you to discover why the car won’t start and enable you to fix it.

A model is a representation of something that is often too difficult (or impossible) to study directly. Models can take the form of physical models, equations, computer programs, or simulations—computer graphics/animations. Models are tools that are especially useful in modern physics because they let us visualize phenomena that we normally cannot observe with our senses, such as very small objects or objects that move at high speeds. For example, we can understand the structure of an atom using models, without seeing an atom with our own eyes. Although images of single atoms are now possible, these images are extremely difficult to achieve and are only possible due to the success of our models. The existence of these images is a consequence rather than a source of our understanding of atoms. Models are always approximate, so they are simpler to consider than the real situation; the more complete a model is, the more complicated it must be. Models put the intangible or the extremely complex into human terms that we can visualize, discuss, and hypothesize about.

Scientific models are constructed based on the results of previous experiments. Even still, models often only describe a phenomenon partially or in a few limited situations. Some phenomena are so complex that they may be impossible to model them in their entirety, even using computers. An example is the electron cloud model of the atom in which electrons are moving around the atom’s center in distinct clouds ( Figure 1.12 ), that represent the likelihood of finding an electron in different places. This model helps us to visualize the structure of an atom. However, it does not show us exactly where an electron will be within its cloud at any one particular time.

As mentioned previously, physicists use a variety of models including equations, physical models, computer simulations, etc. For example, three-dimensional models are often commonly used in chemistry and physics to model molecules. Properties other than appearance or location are usually modelled using mathematics, where functions are used to show how these properties relate to one another. Processes such as the formation of a star or the planets, can also be modelled using computer simulations. Once a simulation is correctly programmed based on actual experimental data, the simulation can allow us to view processes that happened in the past or happen too quickly or slowly for us to observe directly. In addition, scientists can also run virtual experiments using computer-based models. In a model of planet formation, for example, the scientist could alter the amount or type of rocks present in space and see how it affects planet formation.

Scientists use models and experimental results to construct explanations of observations or design solutions to problems. For example, one way to make a car more fuel efficient is to reduce the friction or drag caused by air flowing around the moving car. This can be done by designing the body shape of the car to be more aerodynamic, such as by using rounded corners instead of sharp ones. Engineers can then construct physical models of the car body, place them in a wind tunnel, and examine the flow of air around the model. This can also be done mathematically in a computer simulation. The air flow pattern can be analyzed for regions smooth air flow and for eddies that indicate drag. The model of the car body may have to be altered slightly to produce the smoothest pattern of air flow (i.e., the least drag). The pattern with the least drag may be the solution to increasing fuel efficiency of the car. This solution might then be incorporated into the car design.

Using Models and the Scientific Processes

Be sure to secure loose items before opening the window or door.

In this activity, you will learn about scientific models by making a model of how air flows through your classroom or a room in your house.

- One room with at least one window or door that can be opened

- Work with a group of four, as directed by your teacher. Close all of the windows and doors in the room you are working in. Your teacher may assign you a specific window or door to study.

- Before opening any windows or doors, draw a to-scale diagram of your room. First, measure the length and width of your room using the tape measure. Then, transform the measurement using a scale that could fit on your paper, such as 5 centimeters = 1 meter.

- Your teacher will assign you a specific window or door to study air flow. On your diagram, add arrows showing your hypothesis (before opening any windows or doors) of how air will flow through the room when your assigned window or door is opened. Use pencil so that you can easily make changes to your diagram.

- On your diagram, mark four locations where you would like to test air flow in your room. To test for airflow, hold a strip of single ply tissue paper between the thumb and index finger. Note the direction that the paper moves when exposed to the airflow. Then, for each location, predict which way the paper will move if your air flow diagram is correct.

- Now, each member of your group will stand in one of the four selected areas. Each member will test the airflow Agree upon an approximate height at which everyone will hold their papers.

- When you teacher tells you to, open your assigned window and/or door. Each person should note the direction that their paper points immediately after the window or door was opened. Record your results on your diagram.

- Did the airflow test data support or refute the hypothetical model of air flow shown in your diagram? Why or why not? Correct your model based on your experimental evidence.

- With your group, discuss how accurate your model is. What limitations did it have? Write down the limitations that your group agreed upon.

- Yes, you could use your model to predict air flow through a new window. The earlier experiment of air flow would help you model the system more accurately.

- Yes, you could use your model to predict air flow through a new window. The earlier experiment of air flow is not useful for modeling the new system.

- No, you cannot model a system to predict the air flow through a new window. The earlier experiment of air flow would help you model the system more accurately.

- No, you cannot model a system to predict the air flow through a new window. The earlier experiment of air flow is not useful for modeling the new system.

This Snap Lab! has students construct a model of how air flows in their classroom. Each group of four students will create a model of air flow in their classroom using a scale drawing of the room. Then, the groups will test the validity of their model by placing weathervanes that they have constructed around the room and opening a window or door. By observing the weather vanes, students will see how air actually flows through the room from a specific window or door. Students will then correct their model based on their experimental evidence. The following material list is given per group:

- One room with at least one window or door that can be opened (An optimal configuration would be one window or door per group.)

- Several pieces of construction paper (at least four per group)

- Strips of single ply tissue paper

- One tape measure (long enough to measure the dimensions of the room)

- Group size can vary depending on the number of windows/doors available and the number of students in the class.

- The room dimensions could be provided by the teacher. Also, students may need a brief introduction in how to make a drawing to scale.

- This is another opportunity to discuss controlled experiments in terms of why the students should hold the strips of tissue paper at the same height and in the same way. One student could also serve as a control and stand far away from the window/door or in another area that will not receive air flow from the window/door.

- You will probably need to coordinate this when multiple windows or doors are used. Only one window or door should be opened at a time for best results. Between openings, allow a short period (5 minutes) when all windows and doors are closed, if possible.

Answers to the Grasp Check will vary, but the air flow in the new window or door should be based on what the students observed in their experiment.

Scientific Laws and Theories

A scientific law is a description of a pattern in nature that is true in all circumstances that have been studied. That is, physical laws are meant to be universal , meaning that they apply throughout the known universe. Laws are often also concise, whereas theories are more complicated. A law can be expressed in the form of a single sentence or mathematical equation. For example, Newton’s second law of motion , which relates the motion of an object to the force applied ( F ), the mass of the object ( m ), and the object’s acceleration ( a ), is simply stated using the equation

Scientific ideas and explanations that are true in many, but not all situations in the universe are usually called principles . An example is Pascal’s principle , which explains properties of liquids, but not solids or gases. However, the distinction between laws and principles is sometimes not carefully made in science.

A theory is an explanation for patterns in nature that is supported by much scientific evidence and verified multiple times by multiple researchers. While many people confuse theories with educated guesses or hypotheses, theories have withstood more rigorous testing and verification than hypotheses.

[OL] Explain to students that in informal, everyday English the word theory can be used to describe an idea that is possibly true but that has not been proven to be true. This use of the word theory often leads people to think that scientific theories are nothing more than educated guesses. This is not just a misconception among students, but among the general public as well.

As a closing idea about scientific processes, we want to point out that scientific laws and theories, even those that have been supported by experiments for centuries, can still be changed by new discoveries. This is especially true when new technologies emerge that allow us to observe things that were formerly unobservable. Imagine how viewing previously invisible objects with a microscope or viewing Earth for the first time from space may have instantly changed our scientific theories and laws! What discoveries still await us in the future? The constant retesting and perfecting of our scientific laws and theories allows our knowledge of nature to progress. For this reason, many scientists are reluctant to say that their studies prove anything. By saying support instead of prove , it keeps the door open for future discoveries, even if they won’t occur for centuries or even millennia.

[OL] With regard to scientists avoiding using the word prove , the general public knows that science has proven certain things such as that the heart pumps blood and the Earth is round. However, scientists should shy away from using prove because it is impossible to test every single instance and every set of conditions in a system to absolutely prove anything. Using support or similar terminology leaves the door open for further discovery.

Check Your Understanding

- Models are simpler to analyze.

- Models give more accurate results.

- Models provide more reliable predictions.

- Models do not require any computer calculations.

- They are the same.

- A hypothesis has been thoroughly tested and found to be true.

- A hypothesis is a tentative assumption based on what is already known.

- A hypothesis is a broad explanation firmly supported by evidence.

- A scientific model is a representation of something that can be easily studied directly. It is useful for studying things that can be easily analyzed by humans.

- A scientific model is a representation of something that is often too difficult to study directly. It is useful for studying a complex system or systems that humans cannot observe directly.

- A scientific model is a representation of scientific equipment. It is useful for studying working principles of scientific equipment.

- A scientific model is a representation of a laboratory where experiments are performed. It is useful for studying requirements needed inside the laboratory.

- The hypothesis must be validated by scientific experiments.

- The hypothesis must not include any physical quantity.

- The hypothesis must be a short and concise statement.

- The hypothesis must apply to all the situations in the universe.

- A scientific theory is an explanation of natural phenomena that is supported by evidence.

- A scientific theory is an explanation of natural phenomena without the support of evidence.

- A scientific theory is an educated guess about the natural phenomena occurring in nature.

- A scientific theory is an uneducated guess about natural phenomena occurring in nature.

- A hypothesis is an explanation of the natural world with experimental support, while a scientific theory is an educated guess about a natural phenomenon.

- A hypothesis is an educated guess about natural phenomenon, while a scientific theory is an explanation of natural world with experimental support.

- A hypothesis is experimental evidence of a natural phenomenon, while a scientific theory is an explanation of the natural world with experimental support.

- A hypothesis is an explanation of the natural world with experimental support, while a scientific theory is experimental evidence of a natural phenomenon.