- Privacy Policy

Home » Research Process – Steps, Examples and Tips

Research Process – Steps, Examples and Tips

Table of Contents

Research Process

Definition:

Research Process is a systematic and structured approach that involves the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data or information to answer a specific research question or solve a particular problem.

Research Process Steps

Research Process Steps are as follows:

Identify the Research Question or Problem

This is the first step in the research process. It involves identifying a problem or question that needs to be addressed. The research question should be specific, relevant, and focused on a particular area of interest.

Conduct a Literature Review

Once the research question has been identified, the next step is to conduct a literature review. This involves reviewing existing research and literature on the topic to identify any gaps in knowledge or areas where further research is needed. A literature review helps to provide a theoretical framework for the research and also ensures that the research is not duplicating previous work.

Formulate a Hypothesis or Research Objectives

Based on the research question and literature review, the researcher can formulate a hypothesis or research objectives. A hypothesis is a statement that can be tested to determine its validity, while research objectives are specific goals that the researcher aims to achieve through the research.

Design a Research Plan and Methodology

This step involves designing a research plan and methodology that will enable the researcher to collect and analyze data to test the hypothesis or achieve the research objectives. The research plan should include details on the sample size, data collection methods, and data analysis techniques that will be used.

Collect and Analyze Data

This step involves collecting and analyzing data according to the research plan and methodology. Data can be collected through various methods, including surveys, interviews, observations, or experiments. The data analysis process involves cleaning and organizing the data, applying statistical and analytical techniques to the data, and interpreting the results.

Interpret the Findings and Draw Conclusions

After analyzing the data, the researcher must interpret the findings and draw conclusions. This involves assessing the validity and reliability of the results and determining whether the hypothesis was supported or not. The researcher must also consider any limitations of the research and discuss the implications of the findings.

Communicate the Results

Finally, the researcher must communicate the results of the research through a research report, presentation, or publication. The research report should provide a detailed account of the research process, including the research question, literature review, research methodology, data analysis, findings, and conclusions. The report should also include recommendations for further research in the area.

Review and Revise

The research process is an iterative one, and it is important to review and revise the research plan and methodology as necessary. Researchers should assess the quality of their data and methods, reflect on their findings, and consider areas for improvement.

Ethical Considerations

Throughout the research process, ethical considerations must be taken into account. This includes ensuring that the research design protects the welfare of research participants, obtaining informed consent, maintaining confidentiality and privacy, and avoiding any potential harm to participants or their communities.

Dissemination and Application

The final step in the research process is to disseminate the findings and apply the research to real-world settings. Researchers can share their findings through academic publications, presentations at conferences, or media coverage. The research can be used to inform policy decisions, develop interventions, or improve practice in the relevant field.

Research Process Example

Following is a Research Process Example:

Research Question : What are the effects of a plant-based diet on athletic performance in high school athletes?

Step 1: Background Research Conduct a literature review to gain a better understanding of the existing research on the topic. Read academic articles and research studies related to plant-based diets, athletic performance, and high school athletes.

Step 2: Develop a Hypothesis Based on the literature review, develop a hypothesis that a plant-based diet positively affects athletic performance in high school athletes.

Step 3: Design the Study Design a study to test the hypothesis. Decide on the study population, sample size, and research methods. For this study, you could use a survey to collect data on dietary habits and athletic performance from a sample of high school athletes who follow a plant-based diet and a sample of high school athletes who do not follow a plant-based diet.

Step 4: Collect Data Distribute the survey to the selected sample and collect data on dietary habits and athletic performance.

Step 5: Analyze Data Use statistical analysis to compare the data from the two samples and determine if there is a significant difference in athletic performance between those who follow a plant-based diet and those who do not.

Step 6 : Interpret Results Interpret the results of the analysis in the context of the research question and hypothesis. Discuss any limitations or potential biases in the study design.

Step 7: Draw Conclusions Based on the results, draw conclusions about whether a plant-based diet has a significant effect on athletic performance in high school athletes. If the hypothesis is supported by the data, discuss potential implications and future research directions.

Step 8: Communicate Findings Communicate the findings of the study in a clear and concise manner. Use appropriate language, visuals, and formats to ensure that the findings are understood and valued.

Applications of Research Process

The research process has numerous applications across a wide range of fields and industries. Some examples of applications of the research process include:

- Scientific research: The research process is widely used in scientific research to investigate phenomena in the natural world and develop new theories or technologies. This includes fields such as biology, chemistry, physics, and environmental science.

- Social sciences : The research process is commonly used in social sciences to study human behavior, social structures, and institutions. This includes fields such as sociology, psychology, anthropology, and economics.

- Education: The research process is used in education to study learning processes, curriculum design, and teaching methodologies. This includes research on student achievement, teacher effectiveness, and educational policy.

- Healthcare: The research process is used in healthcare to investigate medical conditions, develop new treatments, and evaluate healthcare interventions. This includes fields such as medicine, nursing, and public health.

- Business and industry : The research process is used in business and industry to study consumer behavior, market trends, and develop new products or services. This includes market research, product development, and customer satisfaction research.

- Government and policy : The research process is used in government and policy to evaluate the effectiveness of policies and programs, and to inform policy decisions. This includes research on social welfare, crime prevention, and environmental policy.

Purpose of Research Process

The purpose of the research process is to systematically and scientifically investigate a problem or question in order to generate new knowledge or solve a problem. The research process enables researchers to:

- Identify gaps in existing knowledge: By conducting a thorough literature review, researchers can identify gaps in existing knowledge and develop research questions that address these gaps.

- Collect and analyze data : The research process provides a structured approach to collecting and analyzing data. Researchers can use a variety of research methods, including surveys, experiments, and interviews, to collect data that is valid and reliable.

- Test hypotheses : The research process allows researchers to test hypotheses and make evidence-based conclusions. Through the systematic analysis of data, researchers can draw conclusions about the relationships between variables and develop new theories or models.

- Solve problems: The research process can be used to solve practical problems and improve real-world outcomes. For example, researchers can develop interventions to address health or social problems, evaluate the effectiveness of policies or programs, and improve organizational processes.

- Generate new knowledge : The research process is a key way to generate new knowledge and advance understanding in a given field. By conducting rigorous and well-designed research, researchers can make significant contributions to their field and help to shape future research.

Tips for Research Process

Here are some tips for the research process:

- Start with a clear research question : A well-defined research question is the foundation of a successful research project. It should be specific, relevant, and achievable within the given time frame and resources.

- Conduct a thorough literature review: A comprehensive literature review will help you to identify gaps in existing knowledge, build on previous research, and avoid duplication. It will also provide a theoretical framework for your research.

- Choose appropriate research methods: Select research methods that are appropriate for your research question, objectives, and sample size. Ensure that your methods are valid, reliable, and ethical.

- Be organized and systematic: Keep detailed notes throughout the research process, including your research plan, methodology, data collection, and analysis. This will help you to stay organized and ensure that you don’t miss any important details.

- Analyze data rigorously: Use appropriate statistical and analytical techniques to analyze your data. Ensure that your analysis is valid, reliable, and transparent.

- I nterpret results carefully : Interpret your results in the context of your research question and objectives. Consider any limitations or potential biases in your research design, and be cautious in drawing conclusions.

- Communicate effectively: Communicate your research findings clearly and effectively to your target audience. Use appropriate language, visuals, and formats to ensure that your findings are understood and valued.

- Collaborate and seek feedback : Collaborate with other researchers, experts, or stakeholders in your field. Seek feedback on your research design, methods, and findings to ensure that they are relevant, meaningful, and impactful.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Problem Statement – Writing Guide, Examples and...

Data Collection – Methods Types and Examples

Institutional Review Board – Application Sample...

Chapter Summary & Overview – Writing Guide...

Informed Consent in Research – Types, Templates...

What is a Hypothesis – Types, Examples and...

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

- QuestionPro

- Solutions Industries Gaming Automotive Sports and events Education Government Travel & Hospitality Financial Services Healthcare Cannabis Technology Use Case AskWhy Communities Audience Contactless surveys Mobile LivePolls Member Experience GDPR Positive People Science 360 Feedback Surveys

- Resources Blog eBooks Survey Templates Case Studies Training Help center

Home Market Research Research Tools and Apps

Research Process Steps: What they are + How To Follow

There are various approaches to conducting basic and applied research. This article explains the research process steps you should know. Whether you are doing basic research or applied research, there are many ways of doing it. In some ways, each research study is unique since it is conducted at a different time and place.

Conducting research might be difficult, but there are clear processes to follow. The research process starts with a broad idea for a topic. This article will assist you through the research process steps, helping you focus and develop your topic.

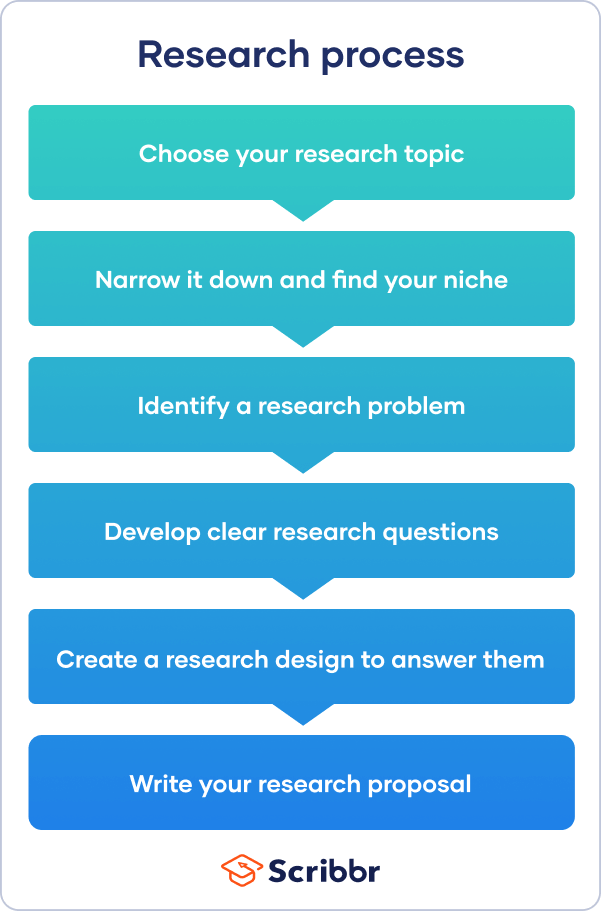

Research Process Steps

The research process consists of a series of systematic procedures that a researcher must go through in order to generate knowledge that will be considered valuable by the project and focus on the relevant topic.

To conduct effective research, you must understand the research process steps and follow them. Here are a few steps in the research process to make it easier for you:

Step 1: Identify the Problem

Finding an issue or formulating a research question is the first step. A well-defined research problem will guide the researcher through all stages of the research process, from setting objectives to choosing a technique. There are a number of approaches to get insight into a topic and gain a better understanding of it. Such as:

- A preliminary survey

- Case studies

- Interviews with a small group of people

- Observational survey

Step 2: Evaluate the Literature

A thorough examination of the relevant studies is essential to the research process . It enables the researcher to identify the precise aspects of the problem. Once a problem has been found, the investigator or researcher needs to find out more about it.

This stage gives problem-zone background. It teaches the investigator about previous research, how they were conducted, and its conclusions. The researcher can build consistency between his work and others through a literature review. Such a review exposes the researcher to a more significant body of knowledge and helps him follow the research process efficiently.

Step 3: Create Hypotheses

Formulating an original hypothesis is the next logical step after narrowing down the research topic and defining it. A belief solves logical relationships between variables. In order to establish a hypothesis, a researcher must have a certain amount of expertise in the field.

It is important for researchers to keep in mind while formulating a hypothesis that it must be based on the research topic. Researchers are able to concentrate their efforts and stay committed to their objectives when they develop theories to guide their work.

Step 4: The Research Design

Research design is the plan for achieving objectives and answering research questions. It outlines how to get the relevant information. Its goal is to design research to test hypotheses, address the research questions, and provide decision-making insights.

The research design aims to minimize the time, money, and effort required to acquire meaningful evidence. This plan fits into four categories:

- Exploration and Surveys

- Data Analysis

- Observation

Step 5: Describe Population

Research projects usually look at a specific group of people, facilities, or how technology is used in the business. In research, the term population refers to this study group. The research topic and purpose help determine the study group.

Suppose a researcher wishes to investigate a certain group of people in the community. In that case, the research could target a specific age group, males or females, a geographic location, or an ethnic group. A final step in a study’s design is to specify its sample or population so that the results may be generalized.

Step 6: Data Collection

Data collection is important in obtaining the knowledge or information required to answer the research issue. Every research collected data, either from the literature or the people being studied. Data must be collected from the two categories of researchers. These sources may provide primary data.

- Questionnaire

Secondary data categories are:

- Literature survey

- Official, unofficial reports

- An approach based on library resources

Step 7: Data Analysis

During research design, the researcher plans data analysis. After collecting data, the researcher analyzes it. The data is examined based on the approach in this step. The research findings are reviewed and reported.

Data analysis involves a number of closely related stages, such as setting up categories, applying these categories to raw data through coding and tabulation, and then drawing statistical conclusions. The researcher can examine the acquired data using a variety of statistical methods.

Step 8: The Report-writing

After completing these steps, the researcher must prepare a report detailing his findings. The report must be carefully composed with the following in mind:

- The Layout: On the first page, the title, date, acknowledgments, and preface should be on the report. A table of contents should be followed by a list of tables, graphs, and charts if any.

- Introduction: It should state the research’s purpose and methods. This section should include the study’s scope and limits.

- Summary of Findings: A non-technical summary of findings and recommendations will follow the introduction. The findings should be summarized if they’re lengthy.

- Principal Report: The main body of the report should make sense and be broken up into sections that are easy to understand.

- Conclusion: The researcher should restate his findings at the end of the main text. It’s the final result.

LEARN ABOUT: 12 Best Tools for Researchers

The research process involves several steps that make it easy to complete the research successfully. The steps in the research process described above depend on each other, and the order must be kept. So, if we want to do a research project, we should follow the research process steps.

QuestionPro’s enterprise-grade research platform can collect survey and qualitative observation data. The tool’s nature allows for data processing and essential decisions. The platform lets you store and process data. Start immediately!

LEARN MORE FREE TRIAL

MORE LIKE THIS

Participant Engagement: Strategies + Improving Interaction

Sep 12, 2024

Employee Recognition Programs: A Complete Guide

Sep 11, 2024

A guide to conducting agile qualitative research for rapid insights with Digsite

Cultural Insights: What it is, Importance + How to Collect?

Sep 10, 2024

Other categories

- Academic Research

- Artificial Intelligence

- Assessments

- Brand Awareness

- Case Studies

- Communities

- Consumer Insights

- Customer effort score

- Customer Engagement

- Customer Experience

- Customer Loyalty

- Customer Research

- Customer Satisfaction

- Employee Benefits

- Employee Engagement

- Employee Retention

- Friday Five

- General Data Protection Regulation

- Insights Hub

- Life@QuestionPro

- Market Research

- Mobile diaries

- Mobile Surveys

- New Features

- Online Communities

- Question Types

- QuestionPro Products

- Release Notes

- Research Tools and Apps

- Revenue at Risk

- Survey Templates

- Training Tips

- Tuesday CX Thoughts (TCXT)

- Uncategorized

- What’s Coming Up

- Workforce Intelligence

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

3 The research process

In Chapter 1, we saw that scientific research is the process of acquiring scientific knowledge using the scientific method. But how is such research conducted? This chapter delves into the process of scientific research, and the assumptions and outcomes of the research process.

Paradigms of social research

Our design and conduct of research is shaped by our mental models, or frames of reference that we use to organise our reasoning and observations. These mental models or frames (belief systems) are called paradigms . The word ‘paradigm’ was popularised by Thomas Kuhn (1962) [1] in his book The structure of scientific r evolutions , where he examined the history of the natural sciences to identify patterns of activities that shape the progress of science. Similar ideas are applicable to social sciences as well, where a social reality can be viewed by different people in different ways, which may constrain their thinking and reasoning about the observed phenomenon. For instance, conservatives and liberals tend to have very different perceptions of the role of government in people’s lives, and hence, have different opinions on how to solve social problems. Conservatives may believe that lowering taxes is the best way to stimulate a stagnant economy because it increases people’s disposable income and spending, which in turn expands business output and employment. In contrast, liberals may believe that governments should invest more directly in job creation programs such as public works and infrastructure projects, which will increase employment and people’s ability to consume and drive the economy. Likewise, Western societies place greater emphasis on individual rights, such as one’s right to privacy, right of free speech, and right to bear arms. In contrast, Asian societies tend to balance the rights of individuals against the rights of families, organisations, and the government, and therefore tend to be more communal and less individualistic in their policies. Such differences in perspective often lead Westerners to criticise Asian governments for being autocratic, while Asians criticise Western societies for being greedy, having high crime rates, and creating a ‘cult of the individual’. Our personal paradigms are like ‘coloured glasses’ that govern how we view the world and how we structure our thoughts about what we see in the world.

Paradigms are often hard to recognise, because they are implicit, assumed, and taken for granted. However, recognising these paradigms is key to making sense of and reconciling differences in people’s perceptions of the same social phenomenon. For instance, why do liberals believe that the best way to improve secondary education is to hire more teachers, while conservatives believe that privatising education (using such means as school vouchers) is more effective in achieving the same goal? Conservatives place more faith in competitive markets (i.e., in free competition between schools competing for education dollars), while liberals believe more in labour (i.e., in having more teachers and schools). Likewise, in social science research, to understand why a certain technology was successfully implemented in one organisation, but failed miserably in another, a researcher looking at the world through a ‘rational lens’ will look for rational explanations of the problem, such as inadequate technology or poor fit between technology and the task context where it is being utilised. Another researcher looking at the same problem through a ‘social lens’ may seek out social deficiencies such as inadequate user training or lack of management support. Those seeing it through a ‘political lens’ will look for instances of organisational politics that may subvert the technology implementation process. Hence, subconscious paradigms often constrain the concepts that researchers attempt to measure, their observations, and their subsequent interpretations of a phenomenon. However, given the complex nature of social phenomena, it is possible that all of the above paradigms are partially correct, and that a fuller understanding of the problem may require an understanding and application of multiple paradigms.

Two popular paradigms today among social science researchers are positivism and post-positivism. Positivism , based on the works of French philosopher Auguste Comte (1798–1857), was the dominant scientific paradigm until the mid-twentieth century. It holds that science or knowledge creation should be restricted to what can be observed and measured. Positivism tends to rely exclusively on theories that can be directly tested. Though positivism was originally an attempt to separate scientific inquiry from religion (where the precepts could not be objectively observed), positivism led to empiricism or a blind faith in observed data and a rejection of any attempt to extend or reason beyond observable facts. Since human thoughts and emotions could not be directly measured, they were not considered to be legitimate topics for scientific research. Frustrations with the strictly empirical nature of positivist philosophy led to the development of post-positivism (or postmodernism) during the mid-late twentieth century. Post-positivism argues that one can make reasonable inferences about a phenomenon by combining empirical observations with logical reasoning. Post-positivists view science as not certain but probabilistic (i.e., based on many contingencies), and often seek to explore these contingencies to understand social reality better. The post-positivist camp has further fragmented into subjectivists , who view the world as a subjective construction of our subjective minds rather than as an objective reality, and critical realists , who believe that there is an external reality that is independent of a person’s thinking but we can never know such reality with any degree of certainty.

Burrell and Morgan (1979), [2] in their seminal book Sociological p aradigms and organizational a nalysis , suggested that the way social science researchers view and study social phenomena is shaped by two fundamental sets of philosophical assumptions: ontology and epistemology. Ontology refers to our assumptions about how we see the world (e.g., does the world consist mostly of social order or constant change?). Epistemology refers to our assumptions about the best way to study the world (e.g., should we use an objective or subjective approach to study social reality?). Using these two sets of assumptions, we can categorise social science research as belonging to one of four categories (see Figure 3.1).

If researchers view the world as consisting mostly of social order (ontology) and hence seek to study patterns of ordered events or behaviours, and believe that the best way to study such a world is using an objective approach (epistemology) that is independent of the person conducting the observation or interpretation, such as by using standardised data collection tools like surveys, then they are adopting a paradigm of functionalism . However, if they believe that the best way to study social order is though the subjective interpretation of participants, such as by interviewing different participants and reconciling differences among their responses using their own subjective perspectives, then they are employing an interpretivism paradigm. If researchers believe that the world consists of radical change and seek to understand or enact change using an objectivist approach, then they are employing a radical structuralism paradigm. If they wish to understand social change using the subjective perspectives of the participants involved, then they are following a radical humanism paradigm.

To date, the majority of social science research has emulated the natural sciences, and followed the functionalist paradigm. Functionalists believe that social order or patterns can be understood in terms of their functional components, and therefore attempt to break down a problem into small components and studying one or more components in detail using objectivist techniques such as surveys and experimental research. However, with the emergence of post-positivist thinking, a small but growing number of social science researchers are attempting to understand social order using subjectivist techniques such as interviews and ethnographic studies. Radical humanism and radical structuralism continues to represent a negligible proportion of social science research, because scientists are primarily concerned with understanding generalisable patterns of behaviour, events, or phenomena, rather than idiosyncratic or changing events. Nevertheless, if you wish to study social change, such as why democratic movements are increasingly emerging in Middle Eastern countries, or why this movement was successful in Tunisia, took a longer path to success in Libya, and is still not successful in Syria, then perhaps radical humanism is the right approach for such a study. Social and organisational phenomena generally consist of elements of both order and change. For instance, organisational success depends on formalised business processes, work procedures, and job responsibilities, while being simultaneously constrained by a constantly changing mix of competitors, competing products, suppliers, and customer base in the business environment. Hence, a holistic and more complete understanding of social phenomena such as why some organisations are more successful than others, requires an appreciation and application of a multi-paradigmatic approach to research.

Overview of the research process

So how do our mental paradigms shape social science research? At its core, all scientific research is an iterative process of observation, rationalisation, and validation. In the observation phase, we observe a natural or social phenomenon, event, or behaviour that interests us. In the rationalisation phase, we try to make sense of the observed phenomenon, event, or behaviour by logically connecting the different pieces of the puzzle that we observe, which in some cases, may lead to the construction of a theory. Finally, in the validation phase, we test our theories using a scientific method through a process of data collection and analysis, and in doing so, possibly modify or extend our initial theory. However, research designs vary based on whether the researcher starts at observation and attempts to rationalise the observations (inductive research), or whether the researcher starts at an ex ante rationalisation or a theory and attempts to validate the theory (deductive research). Hence, the observation-rationalisation-validation cycle is very similar to the induction-deduction cycle of research discussed in Chapter 1.

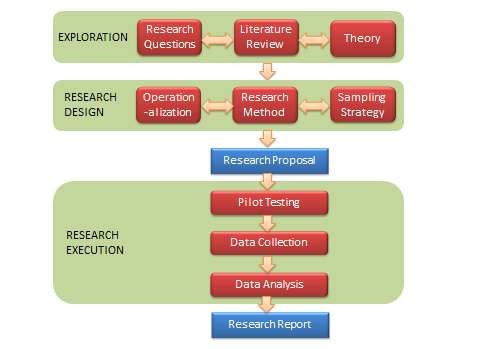

Most traditional research tends to be deductive and functionalistic in nature. Figure 3.2 provides a schematic view of such a research project. This figure depicts a series of activities to be performed in functionalist research, categorised into three phases: exploration, research design, and research execution. Note that this generalised design is not a roadmap or flowchart for all research. It applies only to functionalistic research, and it can and should be modified to fit the needs of a specific project.

The first phase of research is exploration . This phase includes exploring and selecting research questions for further investigation, examining the published literature in the area of inquiry to understand the current state of knowledge in that area, and identifying theories that may help answer the research questions of interest.

The first step in the exploration phase is identifying one or more research questions dealing with a specific behaviour, event, or phenomena of interest. Research questions are specific questions about a behaviour, event, or phenomena of interest that you wish to seek answers for in your research. Examples include determining which factors motivate consumers to purchase goods and services online without knowing the vendors of these goods or services, how can we make high school students more creative, and why some people commit terrorist acts. Research questions can delve into issues of what, why, how, when, and so forth. More interesting research questions are those that appeal to a broader population (e.g., ‘how can firms innovate?’ is a more interesting research question than ‘how can Chinese firms innovate in the service-sector?’), address real and complex problems (in contrast to hypothetical or ‘toy’ problems), and where the answers are not obvious. Narrowly focused research questions (often with a binary yes/no answer) tend to be less useful and less interesting and less suited to capturing the subtle nuances of social phenomena. Uninteresting research questions generally lead to uninteresting and unpublishable research findings.

The next step is to conduct a literature review of the domain of interest. The purpose of a literature review is three-fold: one, to survey the current state of knowledge in the area of inquiry, two, to identify key authors, articles, theories, and findings in that area, and three, to identify gaps in knowledge in that research area. Literature review is commonly done today using computerised keyword searches in online databases. Keywords can be combined using Boolean operators such as ‘and’ and ‘or’ to narrow down or expand the search results. Once a shortlist of relevant articles is generated from the keyword search, the researcher must then manually browse through each article, or at least its abstract, to determine the suitability of that article for a detailed review. Literature reviews should be reasonably complete, and not restricted to a few journals, a few years, or a specific methodology. Reviewed articles may be summarised in the form of tables, and can be further structured using organising frameworks such as a concept matrix. A well-conducted literature review should indicate whether the initial research questions have already been addressed in the literature (which would obviate the need to study them again), whether there are newer or more interesting research questions available, and whether the original research questions should be modified or changed in light of the findings of the literature review. The review can also provide some intuitions or potential answers to the questions of interest and/or help identify theories that have previously been used to address similar questions.

Since functionalist (deductive) research involves theory-testing, the third step is to identify one or more theories can help address the desired research questions. While the literature review may uncover a wide range of concepts or constructs potentially related to the phenomenon of interest, a theory will help identify which of these constructs is logically relevant to the target phenomenon and how. Forgoing theories may result in measuring a wide range of less relevant, marginally relevant, or irrelevant constructs, while also minimising the chances of obtaining results that are meaningful and not by pure chance. In functionalist research, theories can be used as the logical basis for postulating hypotheses for empirical testing. Obviously, not all theories are well-suited for studying all social phenomena. Theories must be carefully selected based on their fit with the target problem and the extent to which their assumptions are consistent with that of the target problem. We will examine theories and the process of theorising in detail in the next chapter.

The next phase in the research process is research design . This process is concerned with creating a blueprint of the actions to take in order to satisfactorily answer the research questions identified in the exploration phase. This includes selecting a research method, operationalising constructs of interest, and devising an appropriate sampling strategy.

Operationalisation is the process of designing precise measures for abstract theoretical constructs. This is a major problem in social science research, given that many of the constructs, such as prejudice, alienation, and liberalism are hard to define, let alone measure accurately. Operationalisation starts with specifying an ‘operational definition’ (or ‘conceptualization’) of the constructs of interest. Next, the researcher can search the literature to see if there are existing pre-validated measures matching their operational definition that can be used directly or modified to measure their constructs of interest. If such measures are not available or if existing measures are poor or reflect a different conceptualisation than that intended by the researcher, new instruments may have to be designed for measuring those constructs. This means specifying exactly how exactly the desired construct will be measured (e.g., how many items, what items, and so forth). This can easily be a long and laborious process, with multiple rounds of pre-tests and modifications before the newly designed instrument can be accepted as ‘scientifically valid’. We will discuss operationalisation of constructs in a future chapter on measurement.

Simultaneously with operationalisation, the researcher must also decide what research method they wish to employ for collecting data to address their research questions of interest. Such methods may include quantitative methods such as experiments or survey research or qualitative methods such as case research or action research, or possibly a combination of both. If an experiment is desired, then what is the experimental design? If this is a survey, do you plan a mail survey, telephone survey, web survey, or a combination? For complex, uncertain, and multifaceted social phenomena, multi-method approaches may be more suitable, which may help leverage the unique strengths of each research method and generate insights that may not be obtained using a single method.

Researchers must also carefully choose the target population from which they wish to collect data, and a sampling strategy to select a sample from that population. For instance, should they survey individuals or firms or workgroups within firms? What types of individuals or firms do they wish to target? Sampling strategy is closely related to the unit of analysis in a research problem. While selecting a sample, reasonable care should be taken to avoid a biased sample (e.g., sample based on convenience) that may generate biased observations. Sampling is covered in depth in a later chapter.

At this stage, it is often a good idea to write a research proposal detailing all of the decisions made in the preceding stages of the research process and the rationale behind each decision. This multi-part proposal should address what research questions you wish to study and why, the prior state of knowledge in this area, theories you wish to employ along with hypotheses to be tested, how you intend to measure constructs, what research method is to be employed and why, and desired sampling strategy. Funding agencies typically require such a proposal in order to select the best proposals for funding. Even if funding is not sought for a research project, a proposal may serve as a useful vehicle for seeking feedback from other researchers and identifying potential problems with the research project (e.g., whether some important constructs were missing from the study) before starting data collection. This initial feedback is invaluable because it is often too late to correct critical problems after data is collected in a research study.

Having decided who to study (subjects), what to measure (concepts), and how to collect data (research method), the researcher is now ready to proceed to the research execution phase. This includes pilot testing the measurement instruments, data collection, and data analysis.

Pilot testing is an often overlooked but extremely important part of the research process. It helps detect potential problems in your research design and/or instrumentation (e.g., whether the questions asked are intelligible to the targeted sample), and to ensure that the measurement instruments used in the study are reliable and valid measures of the constructs of interest. The pilot sample is usually a small subset of the target population. After successful pilot testing, the researcher may then proceed with data collection using the sampled population. The data collected may be quantitative or qualitative, depending on the research method employed.

Following data collection, the data is analysed and interpreted for the purpose of drawing conclusions regarding the research questions of interest. Depending on the type of data collected (quantitative or qualitative), data analysis may be quantitative (e.g., employ statistical techniques such as regression or structural equation modelling) or qualitative (e.g., coding or content analysis).

The final phase of research involves preparing the final research report documenting the entire research process and its findings in the form of a research paper, dissertation, or monograph. This report should outline in detail all the choices made during the research process (e.g., theory used, constructs selected, measures used, research methods, sampling, etc.) and why, as well as the outcomes of each phase of the research process. The research process must be described in sufficient detail so as to allow other researchers to replicate your study, test the findings, or assess whether the inferences derived are scientifically acceptable. Of course, having a ready research proposal will greatly simplify and quicken the process of writing the finished report. Note that research is of no value unless the research process and outcomes are documented for future generations—such documentation is essential for the incremental progress of science.

Common mistakes in research

The research process is fraught with problems and pitfalls, and novice researchers often find, after investing substantial amounts of time and effort into a research project, that their research questions were not sufficiently answered, or that the findings were not interesting enough, or that the research was not of ‘acceptable’ scientific quality. Such problems typically result in research papers being rejected by journals. Some of the more frequent mistakes are described below.

Insufficiently motivated research questions. Often times, we choose our ‘pet’ problems that are interesting to us but not to the scientific community at large, i.e., it does not generate new knowledge or insight about the phenomenon being investigated. Because the research process involves a significant investment of time and effort on the researcher’s part, the researcher must be certain—and be able to convince others—that the research questions they seek to answer deal with real—and not hypothetical—problems that affect a substantial portion of a population and have not been adequately addressed in prior research.

Pursuing research fads. Another common mistake is pursuing ‘popular’ topics with limited shelf life. A typical example is studying technologies or practices that are popular today. Because research takes several years to complete and publish, it is possible that popular interest in these fads may die down by the time the research is completed and submitted for publication. A better strategy may be to study ‘timeless’ topics that have always persisted through the years.

Unresearchable problems. Some research problems may not be answered adequately based on observed evidence alone, or using currently accepted methods and procedures. Such problems are best avoided. However, some unresearchable, ambiguously defined problems may be modified or fine tuned into well-defined and useful researchable problems.

Favoured research methods. Many researchers have a tendency to recast a research problem so that it is amenable to their favourite research method (e.g., survey research). This is an unfortunate trend. Research methods should be chosen to best fit a research problem, and not the other way around.

Blind data mining. Some researchers have the tendency to collect data first (using instruments that are already available), and then figure out what to do with it. Note that data collection is only one step in a long and elaborate process of planning, designing, and executing research. In fact, a series of other activities are needed in a research process prior to data collection. If researchers jump into data collection without such elaborate planning, the data collected will likely be irrelevant, imperfect, or useless, and their data collection efforts may be entirely wasted. An abundance of data cannot make up for deficits in research planning and design, and particularly, for the lack of interesting research questions.

- Kuhn, T. (1962). The structure of scientific revolutions . Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ↵

- Burrell, G. & Morgan, G. (1979). Sociological paradigms and organisational analysis: elements of the sociology of corporate life . London: Heinemann Educational. ↵

Social Science Research: Principles, Methods and Practices (Revised edition) Copyright © 2019 by Anol Bhattacherjee is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- My Bibliography

- Collections

- Citation manager

Save citation to file

Email citation, add to collections.

- Create a new collection

- Add to an existing collection

Add to My Bibliography

Your saved search, create a file for external citation management software, your rss feed.

- Search in PubMed

- Search in NLM Catalog

- Add to Search

Stages in the research process

Affiliation.

- 1 Faculty of Health, Social Care and Education, Anglia Ruskin University, Cambridge, England.

- PMID: 25736674

- DOI: 10.7748/ns.29.27.44.e8745

Research should be conducted in a systematic manner, allowing the researcher to progress from a general idea or clinical problem to scientifically rigorous research findings that enable new developments to improve clinical practice. Using a research process helps guide this process. This article is the first in a 26-part series on nursing research. It examines the process that is common to all research, and provides insights into ten different stages of this process: developing the research question, searching and evaluating the literature, selecting the research approach, selecting research methods, gaining access to the research site and data, pilot study, sampling and recruitment, data collection, data analysis, and dissemination of results and implementation of findings.

Keywords: Clinical nursing research; nursing research; qualitative research; quantitative research; research; research ethics; research methodology; research process; sampling.

PubMed Disclaimer

Similar articles

- Challenges of the grounded theory approach to a novice researcher. Backman K, Kyngäs HA. Backman K, et al. Nurs Health Sci. 1999 Sep;1(3):147-53. doi: 10.1046/j.1442-2018.1999.00019.x. Nurs Health Sci. 1999. PMID: 10894637 Review.

- Getting involved in research: lessons learned from a novice researcher. Lawrence C. Lawrence C. AWHONN Lifelines. 2006 Dec-2007 Jan;10(6):463-5. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6356.2006.00094.x. AWHONN Lifelines. 2006. PMID: 17207208 No abstract available.

- Data collection methods series. Part 5: Training for data collection. Harwood EM, Hutchinson E. Harwood EM, et al. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs. 2009 Sep-Oct;36(5):476-81. doi: 10.1097/WON.0b013e3181b35248. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs. 2009. PMID: 19752655 No abstract available.

- Mixed methods research. Halcomb E, Hickman L. Halcomb E, et al. Nurs Stand. 2015 Apr 8;29(32):41-7. doi: 10.7748/ns.29.32.41.e8858. Nurs Stand. 2015. PMID: 25850508 Review.

- The complexities of nursing research with men. White A, Johnson M. White A, et al. Int J Nurs Stud. 1998 Feb-Apr;35(1-2):41-8. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7489(98)00010-8. Int J Nurs Stud. 1998. PMID: 9695009 Review.

- 'Snapshot in time': a cross-sectional study exploring stakeholder experiences with environmental scans in health services delivery research. Charlton P, Nagel DA, Azar R, Kean T, Campbell A, Lamontagne ME, Déry J, Kelly KJ, Fahim C. Charlton P, et al. BMJ Open. 2024 Feb 2;14(2):e075374. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2023-075374. BMJ Open. 2024. PMID: 38309766 Free PMC article.

- ChatGPT in academic writing: Maximizing its benefits and minimizing the risks. Mondal H, Mondal S. Mondal H, et al. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2023 Dec 1;71(12):3600-3606. doi: 10.4103/IJO.IJO_718_23. Epub 2023 Nov 20. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2023. PMID: 37991290 Free PMC article. Review.

- Formulating the Research Question and Framing the Hypothesis. Willis LD. Willis LD. Respir Care. 2023 Aug;68(8):1180-1185. doi: 10.4187/respcare.10975. Epub 2023 Apr 11. Respir Care. 2023. PMID: 37041024 Free PMC article.

- Search in MeSH

- Citation Manager

NCBI Literature Resources

MeSH PMC Bookshelf Disclaimer

The PubMed wordmark and PubMed logo are registered trademarks of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Unauthorized use of these marks is strictly prohibited.

The Research Process | Steps, How to Start & Tips

Introduction

Basic steps in the research process, conducting a literature review, designing the research project, collecting and analyzing data.

- Interpretation, conclusion and presentation of findings

Key principles for conducting research

The research process is a systematic method used to gather information and answer specific questions. The process ensures the findings are credible, high-quality, and applicable to a broader context. It can vary slightly between disciplines but typically follows a structured pathway from initial inquiry to final presentation of results.

What is the research process?

At its core, the research process involves several fundamental activities: identifying a topic that needs further investigation, reviewing existing knowledge on the subject, forming a precise research question , and designing a method to investigate it. This is followed by collecting and analyzing data , interpreting the results, and reporting the findings. Each step is crucial and builds upon the previous one, requiring meticulous attention to detail and rigorous methodology.

The research process is important because it provides a scientific basis for decision-making. Whether in academic, scientific, or commercial fields, research helps us understand complex issues, develop new tools or products, and improve existing practices. By adhering to a structured research process , researchers can produce results that are not only insightful but also transparent so that others can understand how the findings were developed and build on them in future studies. The integrity of the research process is essential for advancing knowledge and making informed decisions that can have significant social, economic, and scientific impacts.

The research process fosters critical thinking and problem-solving skills. It demands a clear articulation of a problem, thorough investigation, and thoughtful interpretation of data, all of which are valuable skills in any professional field. By following this process, researchers are better equipped to tackle complex questions and contribute meaningful solutions to real-world problems.

From finding the key theoretical concepts to presenting the research findings in a report, every step in the research process forms a cohesive pathway that supports researchers in systematically uncovering deep insights and generating meaningful knowledge, which is crucial for the success of any qualitative investigation.

Identifying key theoretical concepts

The first step in the research process involves finding the key theoretical concepts or words that specify the research topic and are always included in the title of the investigation. Without a definition, these words have no sense or meaning (Daft, 1995). To identify these concepts, a researcher must ask which theoretical keywords are implicit in the investigation. To answer this question a researcher should identify the logical relationships among the two words that catch the focus of the investigation. It is also crucial that researchers provide clear definitions for their theoretical keywords. The title of the research can then include these theoretical keywords and signal how they are being studied.

A piece of useful advice is to draw a conceptual map to visualize the direct or indirect relationships between the key theoretical words and choose a relationship between them as the focus of the investigation.

Developing a research question

One of the most important steps in the research endeavor is identifying a research question. Research questions answer aspects of the topic that need more knowledge or shed light on information that has to be prioritized before others. It is the first step in identifying which participants or type of data collection methods. Research questions put into practice the conceptual framework and make the initial theoretical concepts more explicit.

A research question carries a different implicit meaning depending on how it is framed. Questions starting with what, who, and where usually identify a phenomenon or elements of one, while how, why, when and how much describe, explain, predict or control a phenomenon.

Overall, research questions must be clear, focused and complex. They must also generate knowledge relevant to society and the answers must pose a comprehensive understanding that contributes to the scientific community.

Make the most of your data with ATLAS.ti

Powerful tools in an intuitive interface, ready for you with a free trial today.

A literature review is the synthesis of the existing body of research relevant to a research topic . It allows researchers to identify the current state of the art of knowledge of a particular topic. When conducting research, it is the foundation and guides the researcher to the knowledge gaps that need to be covered to best contribute to the scientific community.

Common methodologies include miniaturized or complete reviews, descriptive or integrated reviews, narrative reviews, theoretical reviews, methodological reviews and systematic reviews.

When navigating through the literature, researchers must try to answer their research question with the most current peer-reviewed research when finding relevant data for a research project. It is important to use the existing literature in at least two different databases and adapt the key concepts to amplify their search. Researchers also pay attention to the titles, summaries and references of each article. It is recommended to have a research diary for useful previous research as it could be the researcher´s go-to source when writing the final report.

A good research design involves data analysis methods suited to the research question, and where data collection generates appropriate data for the analysis method (Willig, 2001).

Designing a qualitative study is a critical step in the research process, serving as the blueprint for the research study. This phase is a fundamental part of the planning process, ensuring that the chosen research methods align perfectly with the research's purpose. During this stage, a researcher decides on a specific approach—such as narrative , phenomenological , grounded theory , ethnographic , or case study —tailoring the design to the unique research problem and needs of the research project. By carefully selecting the research method and planning how to approach the data, researchers can ensure that their work remains focused and relevant to the intended study area.

A well-constructed research design is vital for maintaining the integrity and credibility of the study. It guides the researcher through the research process steps, from data collection to analysis, helping to manage and mitigate potential interpretations and errors. This detailed planning is crucial, particularly in qualitative studies, where the depth of understanding and interpretive nature of analysis can significantly influence outcomes.

The design of a qualitative study is more than a procedural formality; it is a strategic component of the research that enhances the quality of the results. It requires thoughtful consideration of the research question, ensuring that every aspect of the methodology contributes effectively to the overarching goals of the project.

Collecting data

Gathering data can involve various methods tailored to the study's specific needs. To collect data , techniques may include interviews , focus groups, surveys and observations , each chosen for its ability to target a specific group relevant to the research population. For example, focus groups might explore attitudes within a specific age group, while observations might analyze behaviours in a community for population research projects. Data may also come from secondary sources with quantitative and qualitative approaches such as library resources, market research, customer feedback or employee evaluations.

Effective data management is crucial, ensuring that primary data from direct collection and secondary data from sources like public health records are organized and maintained properly. This step is vital for maintaining the integrity of the data throughout the research process steps, supporting the overall goal of conducting thorough and coherent research.

Analyzing data

Once research data has been collected, the next critical step is to analyze the data. This phase is crucial for transforming raw data into high-quality information for meaningful research findings.

Analyzing qualitative data often involves coding and thematic analysis , which helps identify patterns and themes within the data. While qualitative research typically does not focus on drawing statistical conclusions, integrating basic statistical methods can sometimes add depth to the data interpretation, especially in mixed-methods research where quantitative data complements qualitative insights.

In each of the research process steps, researchers utilize various research tools and techniques to conduct research and analyze the data systematically. This may include computer-assisted qualitative data analysis software (CAQDAS) such as ATLAS.ti, which assists in organizing, sorting, and coding the data efficiently. It can also host the research diary and apply analysis methods such as word frequencies and network visualizations.

Interpretation, conclusion and presentation of research findings

Interpreting research findings.

By meticulously following systematic procedures and working through the data, researchers can ensure that their interpretations are grounded in the actual data collected, enhancing the trustworthiness and credibility of the research findings.

The interpretation of data is not merely about extracting information but also involves making sense of the data in the context of the existing literature and research objectives. This step is not only about what the data is, but what it means in the broader context of the study, enabling researchers to draw insightful conclusions that contribute to the academic and practical understanding of the field.

Concluding and presenting research findings

The final step is concluding and presenting the research data which are crucial for transforming analyzed data into meaningful insights and credible findings.

The results are typically shared in a research report or academic paper, detailing the findings and contextualizing them within the broader field. This document outlines how the insights contribute to existing knowledge, suggests areas for future research, and may propose practical applications.

Effective presentation is key to ensuring that these findings reach and impact the intended audience. This involves not just articulating the conclusions clearly but also using engaging formats and visual aids to enhance comprehension and engagement with the research.

The research process is a dynamic journey, characterized by a series of systematic research process steps designed to guide researchers successfully from inception to conclusion. Each step—from designing the study and collecting data to analyzing results and drawing conclusions—plays a critical role in ensuring the integrity and credibility of the research.

Qualitative research is guided by key principles designed to ensure the rigour and depth of the research study. Credibility is crucial, achieved through accurate representations of participant experiences, often verified by peer-review revision. Transferability is addressed by providing rich context, allowing others to evaluate the applicability of findings to similar settings. Dependability emphasizes the stability and consistency of data, maintained through detailed documentation of the research process (such as in a research diary), facilitating an audit trail. This aligns with confirmability, where the neutrality of the data is safeguarded by documenting researcher interpretations and decisions, ensuring findings are shaped by participants and not researcher predispositions.

Ethical integrity is paramount, upholding standards like informed consent and confidentiality to protect participant rights throughout the research journey. Qualitative research also strives for a richness and depth of data that captures the complex nature of human experiences and interactions, often exploring these phenomena through an iterative learning process. This involves cycles of data collection and analysis, allowing for ongoing adjustments based on emerging insights. Lastly, a holistic perspective is adopted to view phenomena in their entirety, considering all aspects of the context and environment, which enriches the understanding and relevance of the research outcomes. Together, these principles ensure qualitative research is both profound and ethically conducted, yielding meaningful and applicable insights.

Daft, R. L. (1995). Organization Theory and Design. West Publishing Company.

Willig, C. (2001). Introducing Qualitative Research in Psychology: Adventures in Theory and Method. McGraw-Hill Companies, Incorporated.

Whatever your research objectives, make it happen with ATLAS.ti. Download a free trial today.

Key Steps in the Research Process - A Comprehensive Guide

Embarking on a research journey can be both thrilling and challenging. Whether you're a student, journalist, or simply inquisitive about a subject, grasping the research process steps is vital for conducting thorough and efficient research. In this all-encompassing guide, we'll navigate you through the pivotal stages of what is the research process, from pinpointing your topic to showcasing your discoveries.

We'll delve into how to formulate a robust research question, undertake preliminary research, and devise a structured research plan. You'll acquire strategies for gathering and scrutinizing data, along with advice for effectively disseminating your findings. By adhering to these steps in the research process, you'll be fully prepared to confront any research endeavor that presents itself.

Step 1: Identify and Develop Your Topic

Identifying and cultivating a research topic is the foundational first step in the research process. Kick off by brainstorming potential subjects that captivate your interest, as this will fuel your enthusiasm throughout the endeavor.

Employ the following tactics to spark ideas and understand what is the first step in the research process:

- Review course materials, lecture notes, and assigned readings for inspiration

- Engage in discussions with peers, professors, or experts in the field

- Investigate current events, news pieces, or social media trends pertinent to your field of study to uncover valuable market research insights.

- Reflect on personal experiences or observations that have sparked your curiosity

Once you've compiled a roster of possible topics, engage in preliminary research to evaluate the viability and breadth of each concept. This initial probe may encompass various research steps and procedures to ensure a comprehensive understanding of the topics at hand.

- Scanning Wikipedia articles or other general reference sources for an overview

- Searching for scholarly articles, books, or media related to your topic

- Identifying key concepts, theories, or debates within the field

- Considering the availability of primary sources or data for analysis

While amassing background knowledge, begin to concentrate your focus and hone your topic. Target a subject that is specific enough to be feasible within your project's limits, yet expansive enough to permit substantial analysis. Mull over the following inquiries to steer your topic refinement and address the research problem effectively:

- What aspect of the topic am I most interested in exploring?

- What questions or problems related to this topic remain unanswered or unresolved?

- How can I contribute new insights or perspectives to the existing body of knowledge?

- What resources and methods will I need to investigate this topic effectively?

Step 2: Conduct Preliminary Research

Having pinpointed a promising research topic, it's time to plunge into preliminary research. This essential phase enables you to deepen your grasp of the subject and evaluate the practicality of your project. Here are some pivotal tactics for executing effective preliminary research using various library resources:

- Literature Review

To effectively embark on your scholarly journey, it's essential to consult a broad spectrum of sources, thereby enriching your understanding with the breadth of academic research available on your topic. This exploration may encompass a variety of materials.

- Online catalogs of libraries (local, regional, national, and special)

- Meta-catalogs and subject-specific online article databases

- Digital institutional repositories and open access resources

- Works cited in scholarly books and articles

- Print bibliographies and internet sources

- Websites of major nonprofit organizations, research institutes, museums, universities, and government agencies

- Trade and scholarly publishers

- Discussions with fellow scholars and peers

- Identify Key Debates

Engaging with the wealth of recently published materials and seminal works in your field is a pivotal part of the research process definition. Focus on discerning the core ideas, debates, and arguments that define your topic, which will in turn sharpen your research focus and guide you toward formulating pertinent research questions.

- Narrow Your Focus

Hone your topic by leveraging your initial findings to tackle a specific issue or facet within the larger subject, a fundamental step in the research process steps. Consider various factors that could influence the direction and scope of your inquiry.

- Subtopics and specific issues

- Key debates and controversies

- Timeframes and geographical locations

- Organizations or groups of people involved

A thorough evaluation of existing literature and a comprehensive assessment of the information at hand will pinpoint the exact dimensions of the issue you aim to explore. This methodology ensures alignment with prior research, optimizes resources, and can bolster your case when seeking research funding by demonstrating a well-founded approach.

Step 3: Establish Your Research Question

Having completed your preliminary research and topic refinement, the next vital phase involves formulating a precise and focused research question. This question, a cornerstone among research process steps, will steer your investigation, keeping it aligned with relevant data and insights. When devising your research question, take into account these critical factors:

Initiate your inquiry by defining the requirements and goals of your study, a key step in the research process steps. Whether you're testing a hypothesis, analyzing data, or constructing and supporting an argument, grasping the intent of your research is crucial for framing your question effectively.

Ensure that your research question is feasible, given your constraints in time and word count, an important consideration in the research process steps. Steer clear of questions that are either too expansive or too constricted, as they may impede your capacity to conduct a comprehensive analysis.

Your research question should transcend a mere 'yes' or 'no' response, prompting a thorough engagement with the research process steps. It should foster a comprehensive exploration of the topic, facilitating the analysis of issues or problems beyond just a basic description.

- Researchability

Ensure that your research question opens the door to quality research materials, including academic books and refereed journal articles. It's essential to weigh the accessibility of primary data and secondary data that will bolster your investigative efforts.

When establishing your research question, take the following steps:

- Identify the specific aspect of your general topic that you want to explore

- Hypothesize the path your answer might take, developing a hypothesis after formulating the question

- Steer clear of certain types of questions in your research process steps, such as those that are deceptively simple, fictional, stacked, semantic, impossible-to-answer, opinion or ethical, and anachronistic, to maintain the integrity of your inquiry.

- Conduct a self-test on your research question to confirm it adheres to the research process steps, ensuring it is flexible, testable, clear, precise, and underscores a distinct reason for its importance.

By meticulously formulating your research question, you're establishing a solid groundwork for the subsequent research process steps, guaranteeing that your efforts are directed, efficient, and yield productive outcomes.

Step 4: Develop a Research Plan

Having formulated a precise research question, the ensuing phase involves developing a detailed research plan. This plan, integral to the research process steps, acts as a navigational guide for your project, keeping you organized, concentrated, and on a clear path to accomplishing your research objectives. When devising your research plan, consider these pivotal components:

- Project Goals and Objectives

Articulate the specific aims and objectives of your research project with clarity. These should be in harmony with your research question and provide a structured framework for your investigation, ultimately aligning with your overarching business goals.

- Research Methods

Select the most appropriate research tools and statistical methods to address your question effectively. This may include a variety of qualitative and quantitative approaches to ensure comprehensive analysis.

- Quantitative methods (e.g., surveys, experiments)

- Qualitative methods (e.g., interviews, focus groups)

- Mixed methods (combining quantitative and qualitative approaches)

- Access to databases, archives, or special collections

- Specialized equipment or software

- Funding for travel, materials, or participant compensation

- Assistance from research assistants, librarians, or subject matter experts

- Participant Recruitment

If your research involves human subjects, develop a strategic plan for recruiting participants. Consider factors such as the inclusion of diverse ethnic groups and the use of user interviews to gather rich, qualitative data.

- Target population and sample size

- Inclusion and exclusion criteria

- Recruitment strategies (e.g., flyers, social media, snowball sampling)

- Informed consent procedures

- Instruments or tools for gathering data (e.g., questionnaires, interview guides)

- Data storage and management protocols

- Statistical or qualitative analysis techniques

- Software or tools for data analysis (e.g., SPSS, NVivo)

Create a realistic project strategy for your research project, breaking it down into manageable stages or milestones. Consider factors such as resource availability and potential bottlenecks.

- Literature review and background research

- IRB approval (if applicable)

- Participant recruitment and data collection

- Data analysis and interpretation

- Writing and revising your findings

- Dissemination of results (e.g., presentations, publications)

By developing a comprehensive research plan, incorporating key research process steps, you'll be better equipped to anticipate challenges, allocate resources effectively, and ensure the integrity and rigor of your research process. Remember to remain flexible and adaptable to navigate unexpected obstacles or opportunities that may arise.

Step 5: Conduct the Research

With your research plan in place, it's time to dive into the data collection phase. As you conduct your research, adhere to the established research process steps to ensure the integrity and quality of your findings.

Conduct your research in accordance with federal regulations, state laws, institutional SOPs, and policies. Familiarize yourself with the IRB-approved protocol and follow it diligently, as part of the essential research process steps.

- Roles and Responsibilities

Understand and adhere to the roles and responsibilities of the principal investigator and other research team members. Maintain open communication lines with all stakeholders, including the sponsor and IRB, to foster cross-functional collaboration.

- Data Management

Develop and maintain an effective system for data collection and storage, utilizing advanced research tools. Ensure that each member of the research team has seamless access to the most up-to-date documents, including the informed consent document, protocol, and case report forms.

- Quality Assurance

Implement comprehensive quality assurance measures to verify that the study adheres strictly to the IRB-approved protocol, institutional policy, and all required regulations. Confirm that all study activities are executed as planned and that any deviations are addressed with precision and appropriateness.

- Participant Eligibility

As part of the essential research process steps, verify that potential study subjects meet all eligibility criteria and none of the ineligibility criteria before advancing with the research.

To maintain the highest standards of academic integrity and ethical conduct:

- Conduct research with unwavering honesty in all facets, including experimental design, data generation, and analysis, as well as the publication of results, as these are critical research process steps.

- Maintain a climate conducive to conducting research in strict accordance with good research practices, ensuring each step of the research process is meticulously observed.

- Provide appropriate supervision and training for researchers.

- Encourage open discussion of ideas and the widest dissemination of results possible.

- Keep clear and accurate records of research methods and results.

- Exercise a duty of care to all those involved in the research.

When collecting and assimilating data:

- Use professional online data analysis tools to streamline the process.

- Use metadata for context

- Assign codes or labels to facilitate grouping or comparison

- Convert data into different formats or scales for compatibility

- Organize documents in both the study participant and investigator's study regulatory files, creating a central repository for easy access and reference, as this organization is a pivotal step in the research process.

By adhering to these guidelines and upholding a commitment to ethical and rigorous research practices, you'll be well-equipped to conduct your research effectively and contribute meaningful insights to your field of study, thereby enhancing the integrity of the research process steps.

Step 6: Analyze and Interpret Data

Embarking on the research process steps, once you have gathered your research data, the subsequent critical phase is to delve into analysis and interpretation. This stage demands a meticulous examination of the data, spotting trends, and forging insightful conclusions that directly respond to your research question. Reflect on these tactics for a robust approach to data analysis and interpretation:

- Organize and Clean Your Data

A pivotal aspect of the research process steps is to start by structuring your data in an orderly and coherent fashion. This organizational task may encompass:

- Creating a spreadsheet or database to store your data

- Assigning codes or labels to facilitate grouping or comparison

- Cleaning the data by removing any errors, inconsistencies, or missing values

- Converting data into different formats or scales for compatibility

- Calculating measures of central tendency (mean, median, mode)

- Determining measures of variability (range, standard deviation)

- Creating frequency tables or histograms to visualize the distribution of your data

- Identifying any outliers or unusual patterns in your data

- Perform Inferential Analysis

Integral to the research process steps, you might engage in inferential analysis to evaluate hypotheses or extrapolate findings to a broader demographic, contingent on your research design and query. This analytical step may include:

- Selecting appropriate statistical tests (e.g., t-tests, ANOVA, regression analysis)

- As part of the research process steps, establishing a significance threshold (e.g., p < 0.05) is essential to gauge the likelihood of your results being a random occurrence rather than a significant finding.

- Interpreting the results of your statistical tests in the context of your research question

- Considering the practical significance of your findings, in addition to statistical significance

When interpreting your data, it's essential to: