Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism

- Our Board of Trustees

- Books & Videos

2021 State of Press Freedom in the Philippines

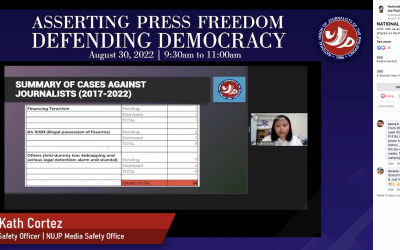

Center for Media Freedom and Responsibility executive director Melinda De Jesus presented this report during the celebration of the World Press Freedom Day on May 3, 2021.

CMFR executive director Melinda De Jesus discusses the history of the Philippine press fighting the Marcos dictatorship to restore democracy, and the country's recent decline to authoritarianism under President Rodrigo Duterte. She also discusses CMFR's database on attacks and threats against journalists, new laws that tighten restrictions on the Philippines media, and how the coronavirus pandemic exacerbated the situation.

By law, the Duterte presidency ends in 2022. It renders this assessment of press freedom in the PH in a new light. The next election confronts the nation with a fork on the road; to turn the page or stay with the status quo. Filipinos must make their choice with a conscious review of the state of the nation, of which the state of press freedom is only a part, albeit a critical one.

We must take note of the larger global context as well, as the election of President Duterte in 2016 counted him among other strong men leaders whose rise in power signified the wave of populism, a trend toward greater authoritarianism and the decline of democracy around the world. The emergence of an undemocratic China as a major global power is also a factor in our national situation.

This annual assessment of press freedom should serve as an examination of how far down the road of authoritarianism the country has come and the consequences of this drift.

It is accurate to say that the Duterte administration has not conducted itself as a democratic government. Duterte himself has behaved as a feudal or political warlord, relying on “shock and awe” tactics to ensure the submission of the population to his will and to his way.

Many Filipinos did not mind the willfulness of the strongman president. With so many struggling just to survive from day to day, submission or resignation is a common response to government. Even before the pandemic, the majority of Filipinos have borne the burden of desperate poverty and hardship. You cannot expect those who suffer daily the urban blight and endless traffic, or the severe lack for basic needs — to be concerned about political questions, to be inclined even to evaluate how well or how poorly they are being served.

While democracy promotes freedom and equality for all, in many countries, it is precisely this inequality, the unfairness in the experience of public goods, that has added to the appeal of the so-called populist message and the pro-poor platform. To strengthen his position, Duterte also expressed his hostility against so called wealthy “oligarchs.”

In power as president, he immediately established the securitization of policy and program implementation, promoting the status of military and police agencies to establish control, the outcome of which has been the massive loss of human rights. As politicians quickly shifted their allegiance to the ruling coalition, the Executive quickly dominated Congress, eliminating an instrument for check and balance. And with his unprecedented attack on the independence of the Supreme Court, Duterte also demolished the power of the judiciary to effectively check presidential will and executive power.

We cannot talk about media without this larger political context.

Our concern today focuses particularly on the impact of the Duterte presidency on the press or media, as an institution, as a community, and the most obvious of all, in the coverage of news.

As we celebrate World Press Freedom Day, we need to engage in a review of the values reflected in the conduct of our work and role in society. How well have we all fulfilled our mandate to build an informed citizenry? What values have we upheld in the coverage of news?

The media operates in society and reflects the nature of that society. Reporting the news, the media holds up a mirror the images, the ideas and insights, and yes, the values expressed in a way of life. The press works according to a set of values. The capacity to reflect, to hold up a mirror may be affected by values that rule society. To ensure the quality of journalism and the freedom of the press, those who work in the media must deepen both their individual well as their institutional values.

Journalistic practice that relies only on recording what “he said-she said” does the job with less questioning, less probing scrutiny of the subject covered. Such coverage echoes the strong authoritarian impulse, should that be the case, which lets the elected powers to do as they please, without question or criticism.

This kind of reporting has allowed this administration to revise our standards for acceptable presidential conduct, for public decency and good taste; as it has allowed the claim that government was doing something to act on the aggressive presence of China in the West Philippine Sea all the while de-bunking the ruling that favored the Philippine’s claim by the arbitral tribunal in the Hague. It has reported without interpretation the primacy of law enforcement agencies in implementing programs, the enhanced militarization and the consequent marginalization of human rights, public interest and common good.

There has been little analysis about the impact of the country’s buy-into the POGO industry, China’s massive Silk Road to support “Build, Build, Build.” – opening the gates to a flood of foreign workers in a country that has for so long sent off Filipinos to work abroad. Surely it is obvious that the president’s favor for China has not recognized our national interest..

This kind of reporting roots out all values in journalism, as though journalism had none.

As Filipinos, we need to ask ourselves, how did we let this happen. Our country was an unlikely home for this global shift. Its history has been rooted in the national struggle of independence from colonial power, the first to succeed in Asia, a liberal framework that protected free expression and press freedom from laws, provided for no less than its constitutions of 1935 and 1987.

But scholarly studies have identified the conditions which show how Philippine democracy has been seeded in soil which was perhaps not sufficiently enriched with nutrients required for democracy to thrive.

Societal structures did not open up enough to allow institutional checks and balances. The forces of clan and family were retained and legitimized as a political dynasties which treated all public affairs as part of their family enterprise.

Indeed, news organizations even reflect so much of this political culture. Despite the constitutional protection of media autonomy and the liberal values asserted in the legal framework; the media community in the country had not always been impervious to state pressure, and enough journalists have been willing to follow government’s lead with obsequious coverage.

The most recent and dramatic example has been the wholesale co-optation of the press by the Ferdinand Marcos when he ruled through Martial Law from 1972 until 1986; and only then when people themselves gathered on the streets to demand his withdrawal from power, forcing the Marcos family, his cronies and officials to exile.

But lest we forget, even under repressive conditions in the past, there have always been journalists who set themselves apart to sustain the function of the fourth estate to check the abuse of power. The alternative press has taken many forms and is showing itself even now, the courage, the fortitude, the will to speak truth to power.

The Duterte administration has succeeded to control the flow of information and dominate coverage, but there are forces in media who retain their fearless independence.

The question now is whether these forces will gain the people’s support or if it will be reduced only to a voice in the wilderness.

Animosity against all critics. Lack of Transparency and Accountability. Social media campaign against mainstream media. Targetting Rappler, ABS-CBN and Inquirer.

These may now be well known facts. But I suggest we force ourselves to recall them.

A brief review indicates that actual interaction of the president with members of the press has been minimal. And yet it is the impact on the press that demonstrates most dramatically the country’s drift toward authoritarianism, indeed of the tyranny of his leadership.

Within the first six months, with media restraining its natural impulse to criticize a new government to observe the traditional good will “honeymoon,” Duterte unleashed the savage force of TokHang against the poorest communities; an army of trolls and his genuine supporters waged a massive social media campaign to demonize the mainstream press along with ceaseless attacks on the political opposition. The connection between troll armies and the Palace communications office became visible as social media influencers were given positions in government or were featured in Palace programs.

In 2017, the intimidation of media, particularly of their owners, set in, instilling an almost visceral fear, a deep-seated terror at being made a target of unfounded charges.

In his second year in office, he singled our three media organizations with threats against their owners – which he acted on. All three,The Philippine Daily Inquirer, broadcast network ABS-CBN and online Rappler, had proactively investigated the rising number of deaths from the government “war on drugs.”

Like a contagion, this animosity toward the free press spread among government officials at all levels, who adopted the president’s own bullying stance, initiating an array of actions against the press, the range of which I will present as recorded in CMFR data base.

The question then: Is there press freedom still in the Philippines?

The answer is, yes, in parts; as the press community itself is also divided.

Actually, the answer one gets depends on who you ask. The press like the rest of the population is divided, working as it were in separate cells even in the same news organization or as news organizations form opposing camps. In some newsrooms, efforts were made to discourage stories that would put the president and the administration in a bad light. Only recently, CMFR has noted take downs or modifications of original reports, self-censorship of the most open kind.

One senses a lack of institutional solidarity, as though organizations were watching out only for own interests alone and not caring about how other organizations fare. As though the institution itself did not exist.

What is the future for this divided press?

The answer may depend on who the public believes more. But bear in mind that even public opinion polls are now being questioned because in an atmosphere of limited information and fear, these methods may no longer make sense.

The conditions then are complex. The constitution remains the sanctuary of its protection. Whether this is effective enough requires more extended and nuanced discussion.

International media watchdogs noted a pattern of restrictions on the press and free speech during the pandemic. Quarantine conditions inherently restrict all activities. But more in some cases than in others. Filipino journalists were required to submit to accreditation, which added another layer of bureaucratic involvement in the press conduct. Everyone knows that such credentials can be withdrawn for no reason at all.

Pandemic conditions heightened the securitization of all government conduct, which made media workers more vulnerable to close examination at check-points and to heightened surveillance.

The economic impact of the lockdowns in different places also caused the demise of numerous daily and weekly news publications based in the communities, small press outlets which served the people with a channel which connected the people to their elected officials.

Lately all the community papers which suspended publications have reportedly returned with both digital and print issues. But we have yet to check if these are doing more or less independently as they did in the past.

There is good news in the resilience shown by community radio. But unfortunately, radio in this country has been dependent on government information, or chat programs that are politically sponsored through the system of block-timing. So whether radio can provide the force among communities to assist them in their political choices remains an open question.

The effect on haccess to information is deeply felt. With poor wi-fi conditions, the digital meetings are difficult to maintain and poor connectivity can easily be used as a cover for officials who do not want to give an answer.

Some officials have resorted to pre-packaged text/online briefings on a a take-it or leave-it basis. There are less and less officials who bother to return calls to answer questions or to clarify questions.

PCIJ reported how the low response rate of government worsened during the quarantine periods. A review period from March 13 to May 27 showed that only one out of ten requests filed before the government’s FOI portal was answered.

Two laws passed in 2020 included provisions that legalize penalties for passing “fake news” adding to those in the Anti-Cybercrime Law – provisions which have been contested in the courts, the latter lost in the High Court. Among the provisions expanding presidential powers to address the COVID-19 challenge in the Bayanihan to Heal as One Law places in the hands of government the determination of what constitutes fake news and its penalties.

Another legislation “Anti-Terror” Law” is now being challenged in the Supreme Court for its unconstitutional provisions, including those that could be used by police and military to curtail legitimate criticism, with at least two cases already recorded for the arrest of critical media practitioners.

The Supreme Court began hearing oral arguments against the Anti-Terror Act. The decision of the High Court will be a major factor in shaping the future of the press. Its implementation will further tighten government’s hold over the once free press of the country. But the discussion should be re-opened on whether there is need for Cyber-libel law?

Even without the pandemic, the deepening culture of fear is itself effectively controlling newsrooms.

The effective closure of the country’s major broadcast network ABS-CBN was an unprecedented act of state power which struck at the core of the media system and the communities, leaving the community still shaken by the experience. If this can happen to ABS-CBN, then it can happen to any of the others.

The counter-insurgency campaign pursued by the National Task Force to End Local Communist Armed Conflict (NTF-ELCAC) has used red-tagging which has included journalists. The unit is chaired by the president himself.

The practice – the quick labeling of individuals or groups as supporters of the Communist Party of the Philippines (CPP), the New People’s Army (NPA) and National Democratic Front (NDF) – endangers victims, including journalists, of being hauled to court on trumped up charges such as illegal possession of firearms and make them vulnerable to harassment or worse.

We have not counted as a threat or attack but flag the role of the National Intelligence Coordinating Agency (NICA) which in 2019 held forums for community media where media members were asked to sign on to a “Manifesto of Commitment” a declaration of their “wholehearted support and commitment to the implementation of President Rodrigo R. Duterte ‘s regional task force to end local communist armed conflict. In this kind of situation, asking journalists to sign makes the act “compelling.”

The state of the community press reveals where and how journalists are most vulnerable, as police and military actions can occur with less national attention, delaying all kinds of assistance and protection. Also with the level of familiarity in the community, it is also easier to intimidate without too much force.

For this reason, we are hoping to work with NUJP members to invigorate the reporting on these attacks and threats which have evolved all kinds of actions, given the changing environment of PH journalism.

With the two years of lockdown and quarantine, some of the practices adopted because of the pandemic may become ingrained. The Reporters sans Fronteres (RSF) Secretary General Christophe de Loire summed up the warning: “What will freedom of information, pluralism and reliability look like in 2030? The answer to that question is being determined today.”

Self-censorship, the wariness of other owners of news organizations holds up the dark clouds over the prospects of press freedom in the Philippines.

Even before the pandemic, CMFR had begun to track numerous issues left un-investigated, stories un-told that the people have a right to know. The effect overall is government’s control of the news agenda. CMFR’s media monitor counts government officials as the predominant sources in the news. They set the news narrative and are generally given more space and time than those opposing them.

As other international media watchdog organizations have pointed out, the pandemic has exacerbated the crisis of limited information and government control which had been going on with democratic decline.

From the CMFR data base, 223 incidents were recorded as reported from June 30 2016 to April 30 2020: these included various levels of harassment, verbal and physical assault, intimidation, libel charges and the banning of journalists from coverage.

CMFR started its data base on the killings of journalists in 1992, verifying the reported 32 cases which at the time already ranked as high as those killed in countries at actual war and battle zones. Our killings map has been upgraded to include more information about the cases.

The FMFA exercise on press freedom day has involved both CMFR and the NUJP whose members report from the ground to evaluate cases together for more enhanced verification.

Nineteen journalists were killed in the line of work from June 30, 2016 to April 30, 2021. All male victims. Four were killed in 2020 during the Covid-19 pandemic. Cornelio Pepino on May 5, two days after the World Press Freedom Day celebration; Jobert Bercasio on September 4; Virgilio Maganes on November 8; and, Ronnie Villamor on November 17.

Thirteen worked in radio, five in print and one online. Nine of those killed were from Mindanao, seven from Luzon and three from Visayas. Five from the Bicol region, four from SOCCSKSARGEN, three from Central Visayas, two each from Western Mindanao and from Caraga, and one from Davao region

CMFR notes the increase in the number of intimidation and libel cases in 2020.

Intimidation includes red-tagging, surveillance and other kinds of harassments including threats to file cases against journalists, doxing and extortion.

Of the 51 cases of intimidation from June 30 2016 to April 30 2021, 30 were incidents of red-tagging.

• Paola Espiritu, Northern Dispatch correspondent, was accused as a communist and otherwise maligned publicly by military officers in a manner that forced her to seek refuge and withdraw from her work.

• Red-tagging has led to arrests in some cases. Journalist Frenchie Mae Cumpio of Eastern Vista was arrested on February 7, 2020 in the Eastern Vista staff house for illegal possession of fire arms. Cumpio remains in prison as of press time.

• On December 10, CIDG members arrested Manila Today Editor Lady Ann Salem for illegal possession of fire arms along with six others in separate raids in Metro Manila. Salem was released on March 5, 2021 after the court cleared her and another for the charges.

Five incidents of surveillance were also recorded. Surveillance includes police visits and vehicle “tailing.”

22 or 43 percent of these incidents were recorded during the pandemic.

There were 37 cases of libel and oral defamation recorded from June 30, 2016 to April 30, 2021. Eighteen of these were online libel. Eight of 37 cases involved actual arrests.

20 or 54 percent of these libel cases were recorded during the pandemic.

The database shows that 114 cases were linked to state agents. CMFR already has already called attention to the increased involvement of state agents as perpetrators with 114 out of 223 cases. LGU 38, police 34, NGov 34 military 8. This is a notable increase that indicates the position that government officials have taken in dealing with the press.

CMFR has also noted the increased reporting of other attacks and threats under the Duterte administration. This may be out of a greater sense of danger for media and journalists that they have begun to report these incidents – some of which they may have tended to ignore in the past.

We should make the effort to find hope and strength in the global solidarity expressed by World Press Freedom Day. It is not an easy thing to do.

The landscape of press freedom has long been darkened by the endemic violence seeded by the “gun culture” evident in so many aspects of public life. This aspect of our national culture should be a understood as a major deterrent to democratic practice. The latter promotes dialogue and debate, talk and conversation. It prescribes for those involved in disagreements, in fights and feuds to come to the table and settle these differences peaceably.

Since 2016, the Duterte administration has deepened political as well as cultural differences highlighting and encouraging hate speech and all kinds of hostility on all communication platforms.

He has unleashed the forces of hate and violence, first through the indiscriminate killings as part of the drug campaign, through the bombing and destruction of Marawi, through the overzealous punishment of those failing to comply with curfew or other measures.

Take the example of the barangay tanod wanting to punish a youth who may have simply stepped out for a breath of fresh air and found himself having to run for his life.

Once our keepers of the law lose their way, violence, guns and weapons become a way of life.

And so today, we must pledge ourselves to use the news as a way out of this dark place. Let us shine our light on the goodness that Filipinos have shown in the midst of so much suffering, the great capacity of the poor to share what little they have, the custom of our country, damayan, pakikiramay, bayanihan. Let there be no mistake about where the press stands when something like the “community pantry” is made to look bad or dubious in terms of its intent.

Indeed, how else can we counter the forces of anger and hate – but to report the simplicity of doing good.

Follow PCIJ on Facebook , Twitter , and Instagram .

'We want the trial to start': What happens now to ICC's probe into Duterte's drug war?

Human rights lawyer Kristina Conti, counsel of the families of drug war victims, said ICC's decisions are hard to predict because its actions are highly compartmentalized. What is clear from the recent developments, though, is that they have strong evidence to begin a trial, she told the Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism (PCIJ).

Philippine rice farmers wish for set price amid chaotic rice value chain

PCIJ traces how prices were set in the market during the rice shortage season last year. It finds that prices increased by at least 80% to as much as 157% from farmgate to retail.

Philippine power transmission monopoly NGCP questions rate review amid calls for refund

Delays in the rate review process mean the National Grid Corporation of the Philippines will continue to charge transmission rates that critics have described as ‘excessive.’

Philippine Media Statement on the Anti-Terrorism Act of 2020

Government’s assurance that protection clauses are in place fly in the face of the experience of news organizations and journalists who have been red-tagged and branded as “terrorists” by government and security officials.

Red-tagging, intimidation vs. press: Duterte, state agents behind 69 cases

Fraught still with attacks and threats -- that is the sorry state of media freedom in the Philippines under the Duterte Administration. It highlights the unyielding reign of impunity, even as the nation awaits next week the promulgation of judgment on Dec. 19, 2019 of the Ampatuan Massacre case of Nov. 23, 2009 that claimed the lives of 58 persons, including 32 journalists and media workers.

OUR NETWORK

Center for Media Freedom & Responsibility

Freedom for Media, Freedom for All Network

International Consortium of Investigative Journalists

Global Investigative Journalism Network (GIJN)

National Union of Journalists of the Philippines

Philippine Press Institute

Right To Know, Right Now! Coalition

Southeast Asian Press Alliance (SEAPA)

Watchdog Asia

Court Appointments Watch

CONNECT WITH US

FAX (632) 3433-0152 Executive Director (632) 3433-0331 Training (632) 3434-6193 Research (632) 3433-0152 Admin (632) 8283-6030

[email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected]

@pcijdotorg pcij.org

pcijdotorg pcij

Philippine journalists’ perspectives on press freedom: The impact of international media campaigns

- Rachel Khan University of the Philippines-Diliman, Quezon City

Legally, press freedom in the Philippines is protected by the 1987 Constitution. However, media laws in the country, especially those referring to freedom of the expression and the press, tend to be inconsistent and volatile. In fact, the country continues to be low ranking in the Reporters Without Borders Press Freedom Index. In response to attacks on press freedom, international media organisations have stepped up to defend and support the Philippine press. Drawing from data gathered through 20 semi-structured indepth interviews with Filipino journalists, this study sought to examine the effect of the government hostility against media on journalists’ perception of press freedom and their attitude towards interventions from international media organisations and coalitions. More specifically, it looks at the impact (or lack thereof) of global media coalitions and foreign media organisations in the country. Findings show that local media are appreciative of the support given by international media organisations in promoting media freedom in the country. However, journalists also noted that when only one segment of the media is targeted, it can lead to divisiveness among local media practitioners.

Balod, S., & Hameleers, M.(2019). Fighting for truth? The role perceptions of Filipino journalists in an era of mis- and disinformation. Political Science, 22, 2368-2385. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884919865109 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884919865109

BBC (2020, May 5). ABS-CBN: Philippines’ biggest broadcaster forced off air. Retrieved May 31, 2022, from https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-52548703

Buan, L. (2019, February 25). Cases vs Maria Ressa, Rappler directors, staff since 2018. Retrieved June 17, 2021, from https://www.rappler.com/nation/223968-list-cases-filed-against-maria-ressa-rappler-reporters/

Butuyan, J. R. (2020, June 22). PH libel law violates international law. Philippine Daily Inquirer, p. 1

Clooney, A. (2020, June 12). A test for democracy in the Philippines. The Washington Post. Retrieved January 2, 2022, from https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/2020/06/12/amal-clooney-test-democracy-philippines/

CMFR (n.d.). Marshall McLuhan fellowship archives – CMFR. Retrieved May 31, 2022, from https://cmfr-phil.org/tag/marshall-mcluhan-fellowship/

CMFR. (2020, May 3). State of media freedom. Retrieved from CMFR: https://cmfr-phil.org/press-freedom-protection/state-of-media-freedom-in-ph/

CMFR. (2021, May 3). State of media freedom. Retrieved from https://pcij.org/article/6425/2021-state-of-press-freedom-in-the-philippines

CPJ (June 10, 2020). Anti-terrorism legislation threatens press freedom in the Philippines. Retrieved May 31, 2022, from https://cpj.org/2020/06/anti-terrorism-legislation-threatens-press-freedom-in-the-philippines/

CPJ (2022). Journalists killed in the Philippines. Retrieved May 31, 2022, from https://cpj.org/data/killed/asia/Philippines/?status=Killed&motiveConfirmed%5B%5D=Confirmed&type%5B%5D=Journalist&cc_fips%5B%5D=RP&start_year=2016&end_year=2022&group_by=location

Corbin, J., & Strauss, A. (1996). Analytic ordering for theoretical purposes. 2(2), 139-150. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/107780049600200201

Daguno-Bersamina, Kristine (2017, July 24). Duterte uses SONA time to lash out against media. Philippine Star, p. 1.

De Jesus, M. (2020, November 4). Statement during the Philippine Press Institute online forum on ‘Safety of journalists in time of crisis’.

Elemia, C. (2020, December 2). Why the PH needs to change old ways of covering Duterte when he lies” in Rappler. Accessed on October 7, 2021 from https://www.rappler.com/newsbreak/in-depth/reasons-philippine-media-need-change-old-ways-covering-duterte-when-he-lies

Estella, P. G. (2020). Journalism competence and the COVID-19 crisis in Southeast Asia: Toward journalism as a transformative and interdisciplinary enterprise. Pacific Journalism Review : Te Koakoa, 26(2), 15-34. https://doi.org/10.24135/pjr.v26i2.1132 DOI: https://doi.org/10.24135/pjr.v26i2.1132

Fact check. (n.d.) Rappler. retrieved from https://www.rappler.com/section/newsbreak/fact-check/

Freedom for Media Freedom for All. (2020). Press freedom further restricted amid COVID-19 pandemic. Manila: Freedom for Media Freedom for All.

Guiterrez, J. (2020, December 15). Philippine Congress officially shuts down leading broadcaster. New York Times. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2020/07/10/world/asia/philippines-congress-media-duterte-abs-cbn.html

ICFJ. (2020, July). #Holdtheline campaign launched in support of Maria Ressa and independent media in the Philippines. International Center for Journalists.

IFJ. (2021). Philippines: Journalists falsely ‘red-tagged’ by military. International Federation of Journalists. Retrieved January 10, 2022, from https://www.ifj.org/media-centre/news/detail/category/press-freedom/article/philippines-journalists-falsely-red-tagged-by-military.html

Ilagan, K. (2020, June 5). Quarantine curbs access to information. Rappler. Retrieved July 20, 2021, from at http://manilastandardtoday.com/2014/03/04/ending-criminal-libel/

Interaksyon (2017, April 28). Di ko masikmura: Duterte threatens to squeeze PDI and ABS-CBN. Retrieved July 20, 2021, from https://interaksyon.philstar.com/breaking-news/2017/04/28/68713/oligarch-media-du30-hits-inquirer-abs-cbn-anew-to-recover-property-from-pdi-owners-block-lopez-firms-franchise-renewal/

Internews (n.d.). Region: Philippines. Retrieved May 31, 2022, from https://internews.org/region/philippines/

Media Freedom Coalition (2022). About/history. Retrieved May 31, 2022, from https://mediafreedomcoalition.org/about/history

Meinardus, R. (2006). Liberal times in the Philippines: Reflections on politics, society and the role of media. Germany: Friedrich Naumann Foundation.

Mellado, C., & Lagos, C. (2014). Professional roles in news content: Analyzing journalistic performance in the Chilean national press. International Journal of Communication, 8: 2090–112.

Mellado, C., & Hellmueller, L. (2017). Journalistic role performance: A new research agenda in a digital and global media environment. In C. Mellado, L. Hellmueller, & W. Donsbach (Eds.), Journalistic role performance: Concepts, contexts, and methods. New York, NY: Routledge. DOI: https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315768854

Myers, M., Scott, M., Bunce, M., Yassin, L., Fernandez, M. C., & Khan, R. (2022). Re-set required? Evaluating the Media Freedom Coalition after its first two years. London, UK: Foreign Policy Centre.

Pingel, J. (2014, April). Challenging red-baiting. OBSERVER: A Journal on threatened Human Rights Defenders in the Philippines, 6(1), 4-6.

Pinlac, M. (2012, February 17). Decriminalizing libel: UN declares PH libel law ‘excessive’. Retrieved from https://cmfr-phil.org/press-freedom-protection/press-freedom/decriminalizing-libel-un-declares-ph-libel-law-excessive/

Ranada, P. (2017). Duterte claims Rappler ‘fully owned by Americans’. Rappler. Retrieved from https://www.rappler.com/nation/176565-sona-2017-duterte-rappler-ownership/

Ratcliffe, R. (2020, June 15). Maria Ressa: Rappler editor found guilty of cyber libel charges in Philippines. The Guardian. Retrieved November 15, 2020, from https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/jun/15/maria-ressa-rappler-editor-found-guilty-of-cyber-libel-charges-in-philippines

Reporters Without Borders (2001). 2001 World press freedom index. Retrieved May 31, 2022, from https://rsf.org/en/index?year=2001

Reporters Without Borders (2021a). 2021 World press freedom index. https://rsf.org/en/index?year=2021

Reporters Without Borders (2021b). Journalism, the vaccine against disinformation, blocked in more than 130 countries. Retrieved from https://rsf.org/en/2021-world-press-freedom-index-journalism-vaccine-against-disinformation-blocked-more-130-countries

Reporters Without Borders (2022). 2022 World press freedom index. Retrieved May 31, 2022, from https://rsf.org/en/index

Rey, A. (2020, May 5). ABS-CBN shutdown, a betrayal of 11,000 workers, labor groups say. Rappler. Retrieved October, 2021, from https://www.rappler.com/nation/260007-abs-cbn-shutdown-betrayal-workers-labor-groups-statement/

Robie, D., & Abcede, D. (2015). PHILIPPINES: Cybercrime, criminal libel and the media: From ‘e-martial law’ to the Magna Carta in the Philippines. Pacific Journalism Review : Te Koakoa, 21(1), 211-229. https://doi.org/10.24135/pjr.v21i1.158 DOI: https://doi.org/10.24135/pjr.v21i1.158

Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. (1990). Basics of qualitative research: Grounded theory Procedures and techniques. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publications.

Strauss A. & Corbin, J. (1998). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory (2nd edition). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Talambong, R. (2021, December 10). Rappler’s Maria Ressa makes history, receives Nobel peace prize in Oslo. Rappler. Retrieved January 1, 2022, from https://www.rappler.com/world/global-affairs/maria-ressa-makes-history-receives-nobel-peace-prize-oslo-norway/

The Nobel Peace Prize (n.d.). About the prize. Retrieved January 15, 2022, from https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/peace/

Tandoc, E. (2017). Watching over the watchdogs. Journalism Studies, 18(1), 102-117. https://doi.org/10.1080/1461670X.2016.1218298 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/1461670X.2016.1218298

Westerman, A. (2019). Journalist’s arrest in Philippines sparks demonstrations, fears of wider crackdown. NPR. Retrieved January 15, 2022, from https://www.npr.org/2019/02/15/695062771/journalists-arrest-in-philippines-sparks-demonstrations-fears-of-wider-crackdown

- Endnote/Zotero/Mendeley (RIS)

Copyright (c) 2022 Rachel Khan

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License .

Pacific Journalism Review

Print ISSN: 1023-9499 Online ISSN: 2324-2035

Published by Asia Pacific Media Network | Te Koakoa Incorporated , in collaboration with Tuwhera at Auckland University of Technology, Aotearoa New Zealand.

PJR on SJR Scimago impact metrics

PJR citations on Google Scholar

Pacific Journalism Review: Twenty years on the front line of regional identity and freedom »

Pacific Media Centre Online Archive 2007-2020

30th Year of Publication »

2024 Pacific Media Conference

Pacific Journalism Review is collaborating with IKAT: The Indonesian Journal of Southeast Asian Studies , published by the Center for Southeast Asian Social Studies (CESASS) at the Universitas Gadjah Mada in Yogyakarta, Indonesia, for special joint editions on media, climate change and maritime disasters in July 2018.

Hosted by Tuwhera , an initiative of the Auckland University of Techology Library .

Your subscription makes our work possible.

We want to bridge divides to reach everyone.

Get stories that empower and uplift daily.

Already a subscriber? Log in to hide ads .

Select free newsletters:

A selection of the most viewed stories this week on the Monitor's website.

Every Saturday

Hear about special editorial projects, new product information, and upcoming events.

Select stories from the Monitor that empower and uplift.

Every Weekday

An update on major political events, candidates, and parties twice a week.

Twice a Week

Stay informed about the latest scientific discoveries & breakthroughs.

Every Tuesday

A weekly digest of Monitor views and insightful commentary on major events.

Every Thursday

Latest book reviews, author interviews, and reading trends.

Every Friday

A weekly update on music, movies, cultural trends, and education solutions.

The three most recent Christian Science articles with a spiritual perspective.

Every Monday

In the Philippines, free press won’t go down without a fight

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

- By Mark Saludes Contributor

July 25, 2022 | MANILA, Philippines

The Philippines is one of the most dangerous countries in the world to be a journalist, with reporters regularly enduring verbal abuse, online attacks, libel charges, and physical harassment. The National Union of Journalists of the Philippines reports that at least 23 journalists have been killed since 2016.

Experts say the new administration could be worse. President Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos Jr. and Vice President Sarah Duterte both come from political families that are hostile toward journalists. A few days after Mr. Marcos assumed the presidency on June 30, the Court of Appeals upheld the conviction of Nobel Peace Prize laureate Maria Ressa for cyber libel, marking the latest in a series of blows to the acclaimed journalist, who now faces nearly seven years in prison.

Why We Wrote This

The Philippine government has a history of targeting adversarial journalists. Until press freedom is fully protected, experts say it’s the public that loses out.

In courts and newsrooms across the country, journalists such as Ms. Ressa are fighting for their right to work freely. Danilo Arao, an associate professor journalism at the University of the Philippines in Diliman, says the magnitude of harassment and intimidation is producing a “chilling effect” and hinders the Philippine press from doing its job.

“If this continues, you’ll end up with docile and servile people who favor political power, rather than adversarial journalists,” he says.

Freedom of press is guaranteed by the Philippines’ Constitution. Yet the island nation has become one of the most dangerous places in the world to exercise that right.

Journalists endured verbal abuse, online attacks, libel charges, and physical harassment for years under the strongman rule of Rodrigo Duterte. The National Union of Journalists of the Philippines reports that at least 23 journalists have been killed since 2016, and many expect the new administration will be worse.

Both President Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos Jr., son and namesake of the famous dictator, and Vice President Sarah Duterte, daughter of Mr. Duterte, come from political families that are openly hostile toward journalists. It remains to be seen whether they will build on their parents’ legacies of cracking down on press freedom, but the past few weeks haven’t been encouraging. A few days after Mr. Marcos assumed the presidency on June 30, the Court of Appeals upheld the conviction of Nobel Peace Prize laureate Maria Ressa for cyber libel, marking the latest in a series of blows to the acclaimed journalist and her embattled publication Rappler. She now faces nearly seven years in prison.

It’s one thing to enshrine a freedom in the constitution – it’s another to ensure that freedom in practice. In courts and newsrooms across the country, journalists are fighting for their right to work freely. Still, experts worry about how the press would fare under six more years of persecution, and the impact this all has on Philippine democracy.

Danilo Arao, an associate professor of journalism at the University of the Philippines in Diliman, says the magnitude of harassment and intimidation is producing a “chilling effect” and hinders the Philippine press from “performing the highest normative standards of journalism.”

Defending press freedom in court

Ms. Ressa, who is also a U.S. citizen, is facing seven active cases before the Philippine courts, all filed during the time of Mr. Duterte.

She says she hasn’t given up “hope that these next six years will be slightly better,” because the Marcoses “are more sophisticated [than the Dutertes] in some ways.” But she’s ready to fight if things get worse. Despite losing her recent appeal against the cyber libel conviction, Ms. Ressa’s legal team considers the ruling an opportunity for the Supreme Court to examine the constitutionality of cyber libel and the continuing criminalization of libel.

In a statement , Ms. Ressa’s lawyer Amal Clooney said she hopes the high court will “restore the country’s constitutional commitment to freedom of speech. And I hope that the new Marcos administration will show the world that it is strong enough to withstand scrutiny and allow a free press.”

Ms. Ressa says the string of cases against Rappler and the onslaught of attacks against the Philippine media aimed to “make us voluntarily stay quiet, to voluntarily give up our rights.”

“We’re not going to do that in Rappler. I’ve said this repeatedly over the last six years – and apparently, for another six years: We’re not going to go away,” she says.

Alternative news site Bulatlat.com, one of 27 websites that were blocked by the National Telecommunications Commission during Mr. Duterte’s final weeks in office, has also brought the battle to the courts.

“The memorandum order clearly violates our constitutional freedoms of the press, speech, and expression,” says Ronalyn Olea, managing editor of Bulatlat.com. “It does not just constitute censorship; it also deprived us of due process of law.”

The site is still blocked, but Ms. Olea hopes the court will rule “in favor of press freedom and the public’s right to information” at a preliminary injunction set for Aug. 2.

In peril: public’s right to know

News organizations in the Philippines face a plethora of threats that make it difficult to deliver information to the public. Several outlets including CNN Philippines and Rappler have been targets of distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) attacks, a form of internet censorship in which attackers crash a website for hours or days by flooding it with traffic.

Last year, DDoS attacks on Bulatlat.com and Altermidya.net – another alternative news site blocked in June by the National Telecommunications Commission – were traced to an IP address assigned to the Philippine army. No one has been held accountable.

Experts say alternative and community publications, which are small and scattered in nature, are especially vulnerable to “red-tagging,” in which authorities open up specific reporters or publications to harassment by linking them to communist or rebel groups. Rhea Padilla, national coordinator of Alternative Media Network, says the government has tagged journalists “for publishing stories that depict the people’s struggle and stimulate critical public discourse.”

Jonathan de Santos, president of the National Union of Journalists of the Philippines, calls these attacks “a disservice to the Filipino people.”

“They want people to become blinded followers,” he says.

Search for solidarity

Over the past six years, there is a growing solidarity among journalists amid the intensifying attack on press freedom. Mr. de Santos says many individual journalists, especially the young ones, “are setting aside competition to strengthen the fight against disinformation and confront all kinds of attacks on press freedom.”

“However, we still have to translate this kind of solidarity among newsrooms and media organizations. We need to push back as one industry,” he says.

For Ms. Ressa, winning the war against media repression requires winning the trust and confidence of the Filipino public, who shaped the foundation of press freedom in the country.

When Ferdinand Marcos Sr. imposed martial law in 1972, he immediately ordered the military to seize major media outlets’ assets. The closure of trusted news outlets and murder of adversarial journalists eventually gave birth to the “mosquito press,” a collective name for alternative publications that criticized the dictatorship. They were said to be “small, but have a stinging bite.” Later, the 1986 People Power Revolt that ousted the senior Mr. Marcos also helped restore press freedom, enshrining the right in the 1987 constitution. It’s a history that Ms. Ressa hopes Filipino people will remember going into this new era.

“The point is, if only one stands up, it’s easy to slap them down. But if a thousand stand up, then it becomes harder. So it’s not just journalists you have to turn to. It is also Filipinos,” she says. “This is a time when we have to stand up for our rights.”

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Unlimited digital access $11/month.

Digital subscription includes:

- Unlimited access to CSMonitor.com.

- CSMonitor.com archive.

- The Monitor Daily email.

- No advertising.

- Cancel anytime.

Related stories

Catholic nation the filipino church rethinks its role in politics., journalism in mexico: where getting the story could mean getting killed, afghan journalists’ battle: to keep free expression alive, focus in the philippines, divided politics feed – and feed on – a divided web, share this article.

Link copied.

Dear Reader,

About a year ago, I happened upon this statement about the Monitor in the Harvard Business Review – under the charming heading of “do things that don’t interest you”:

“Many things that end up” being meaningful, writes social scientist Joseph Grenny, “have come from conference workshops, articles, or online videos that began as a chore and ended with an insight. My work in Kenya, for example, was heavily influenced by a Christian Science Monitor article I had forced myself to read 10 years earlier. Sometimes, we call things ‘boring’ simply because they lie outside the box we are currently in.”

If you were to come up with a punchline to a joke about the Monitor, that would probably be it. We’re seen as being global, fair, insightful, and perhaps a bit too earnest. We’re the bran muffin of journalism.

But you know what? We change lives. And I’m going to argue that we change lives precisely because we force open that too-small box that most human beings think they live in.

The Monitor is a peculiar little publication that’s hard for the world to figure out. We’re run by a church, but we’re not only for church members and we’re not about converting people. We’re known as being fair even as the world becomes as polarized as at any time since the newspaper’s founding in 1908.

We have a mission beyond circulation, we want to bridge divides. We’re about kicking down the door of thought everywhere and saying, “You are bigger and more capable than you realize. And we can prove it.”

If you’re looking for bran muffin journalism, you can subscribe to the Monitor for $15. You’ll get the Monitor Weekly magazine, the Monitor Daily email, and unlimited access to CSMonitor.com.

Subscribe to insightful journalism

Subscription expired

Your subscription to The Christian Science Monitor has expired. You can renew your subscription or continue to use the site without a subscription.

Return to the free version of the site

If you have questions about your account, please contact customer service or call us at 1-617-450-2300 .

This message will appear once per week unless you renew or log out.

Session expired

Your session to The Christian Science Monitor has expired. We logged you out.

No subscription

You don’t have a Christian Science Monitor subscription yet.

Press freedom under attack: why Filipino journalist Maria Ressa’s arrest should matter to all of us

Professor of Journalism and Communications, The University of Queensland

Disclosure statement

Peter Greste is UNESCO Chair in Journalism and Communications at the University of Queensland. He is also a founding member and spokesman for the Alliance for Journalists Freedom.

University of Queensland provides funding as a member of The Conversation AU.

View all partners

- Bahasa Indonesia

In a scene right out of a thriller, agents from the Filipino National Bureau of Investigation (NBI) raided journalist and editor Maria Ressa’s Manila office at 5pm on Wednesday February 13, after most courts had closed. They took her from the Rappler newsroom where she is editor, to a police watch house and threw her in a cell.

Ressa’s lawyer bagged up enough cash to post bail and rushed to the only available judge who was presiding over the night court. The judge refused bail, forcing the journalist to spend the night in prison before another judge finally released her the following day.

Ressa’s crime? According to the NBI, she had been arrested on charges of “cyber-libel” – online defamation – for a story alleging a prominent businessman was involved in criminal activity.

Why it matters

Maria Ressa’s case is important not only because a government used a crime statute to intimidate and lock up a journalist for what should have been treated as a civil dispute, but because of what it says about the way governments are increasingly using the “rule of law” to silence the legitimate work of journalists.

“As a journalist, I know firsthand how the law is being weaponised against perceived critics,” Ressa told CNN .

“I’m not a critic,” she continued. “I’m a journalist and I’m doing my job, holding the government to account.”

Ressa is one of the world’s most decorated reporters. A former CNN correspondent, she set up the news website Rappler.com early in 2012 with a group of colleagues. Since then, it has won numerous awards and become one of the most respected news organisations in the Philippines, fearlessly covering the Duterte government and the consequences of its war on drugs that has claimed thousands of lives.

Last year, TIME Magazine named Ressa a “Person of the Year” – among several journalists including the recently murdered Jamal Khashoggi – for her courageous defence of press freedom.

Read more: Four journalists, one newspaper: Time Magazine's Person of the Year recognises the global assault on journalism

Rappler published the disputed story in May 2012, four months before the government passed the cyber-libel law. (Under the Philippines’ constitution, no law can be retroactive .) The law also requires complaints to be filed within a year of publication.

The NBI said Rappler had updated the story in 2014 (it corrected a spelling error), and argued that because the story was still online, the website was guilty of “ continuous publication ”.

The cyber-libel charge is the latest in a long string of legal attacks Rappler is fighting off. Ressa told CNN she is involved in no less than seven separate cases, including charges of violating laws that prohibit foreign ownership of media companies and tax evasion.

She vehemently denies all the allegations, and to date there has been no evidence to support them. Instead, the legal assault has widely been condemned as a blatant attack on press freedom.

After the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) – responsible for registering companies in the Philippines – warned it was revoking Rappler’s license to operate because of breaches of the ownership laws, Philippines Senator Risa Hontiveros tweeted this was “a move straight out of the dictator’s playbook. I urge the public and all media practitioners to defend press freedom and the right to speak truth to power.”

The Foreign Correspondents Association of the Philippines expressed “deep concern” over the SEC decision, saying it was “tantamount to killing the online news site”. And, the Economic Journalists Association of the Philippines said the decision

will be remembered in Philippine press history infamy. It is the day that a government built on democratic principles struck a blow on one of the pillars of Asia’s most vibrant democracy.

The SEC has allowed Rappler to continue operating while the case is pending, but the threat of closure remains.

In its defence, the country’s justice department denied it was an attack on press freedom, arguing free speech did not give licence to engage in libel. That is true of course, but the way the authorities in the Philippines have been twisting the law to suit a blatantly political purpose should be troubling to all of us.

Read more: Maria Ressa: journalists need protection in Duterte’s Philippines, but we must also heed the stories they tell

How governments silence journalists

The Duterte administration isn’t the first to do this. It happened to my two colleagues and I in Egypt, where we were charged and convicted for terrorism offences after we spoke to the Muslim Brotherhood - the group who had six months earlier been ousted from power as the first legitimately elected government in Egypt’s history.

As responsible journalists, we had a duty to speak to all parties involved in the political crisis, and for doing our jobs, we were sentenced to seven years for “promoting terrorist ideology”.

Turkey is the world’s most prolific jailer of journalists, with 68 in prison . Yet all are there on terrorism charges.

And the problem is not limited to authoritarian regimes. As much as former US President Barack Obama spoke out in our defence while we were imprisoned in Cairo, his administration used the Espionage Act (passed in 1917 to deal with foreign spies) more than all his predecessors combined.

The act was applied against government workers leaking information to the press. If the leaks exposed genuinely sensitive information, this would be understandable, but in almost every case it was to go after journalists or their sources revealing politically embarrassing stories.

Read more: United States will stay on the Greste case, Ambassador says

In Australia, a slew of laws have come in that, in their own way, choke off journalists’ ability to hold the government, courts and individuals to account. Whether it is the data retention law that makes it almost impossible to protect sources, or the chronic overuse of suppression orders that restrict journalists’ capacity to report on court cases, or defamation laws weighted heavily in against the media, all make the our societies more opaque without providing protection for legitimate journalistic inquiry.

As Maria Ressa said after she was released on bail :

Press freedom is not just about journalists. This is certainly not just about me or Rappler. Press freedom is the foundation of every Filipino’s right to the truth. We will keep fighting. We will hold the line. This has become more important than ever.

- Press freedom

- Peter Greste

- Rodrigo Duterte

- Maria Ressa

Biocloud Project Manager - Australian Biocommons

Director, Defence and Security

Opportunities with the new CIEHF

School of Social Sciences – Public Policy and International Relations opportunities

Deputy Editor - Technology

- Staff portal

Griffith Asia Insights

Posted by Griffith Asia Institute | Published 13 July 2020

Reflections on press freedom as a pillar of democracy

Image credit: The STAR/KJ Rosales

STEFAN ARMBRUSTER |

The news isn’t great for journalists and democracy in the Asia-Pacific region right now, with existing pressures on media freedom amplified as the COVID-19 pandemic rages and coinciding with government attempts to stifle critical voices. While parliaments are partially suspended due to the coronavirus, laws have been introduced not just to lockdown populations to prevent infection but also on the pretext of state security. The role of the media to independently inform citizens and hold governments to account is now more critical than ever before.

The 2020 Reporters Without Borders (RSF) World Press Freedom Index is just the latest to highlight “converging crises affecting the future of journalism”, particularly in the Asia-Pacific region “that saw the greatest rise in press freedom violations”.

In “ Holding the Line: A Report into Impunity, Journalist Safety and Working Conditions ”, the International Federation of Journalists (IFJ) reported media workers were increasingly being targeted by authorities and enmeshed in “debilitating legal maelstroms” with one objective: to “silence the media and shut down the truth”.

For the Griffith Asia Institute (GAI)’s next Perspectives Asia event, three eminent journalists from the region – Philippines, Papua New Guinea and Australia – will discuss the “Role of press freedom as a pillar of democracy”.

Director of GAI Professor Caitlin Byrne invites you to join a forthright discussion by these brave and respected champions of press freedom in the Asia-Pacific region on the right to speak truth to power.

“A free press plays an essential role in our democratic societies – holding governments to account, highlighting corruption, injustice and abuse of power while enabling societies to be more informed and engaged in the decisions and policies that affect them. The World Press Freedom Index 2020 reports a fairly gloomy picture of press freedom worldwide, but makes particular note of the worrying trends at play in the Asia Pacific. Increasing forms of government intimidation, censorship and oppression of journalists and media outlets in Australia and across the region threaten to undermining the very nature and resilience of our democracies. How we address this issue in the next decade will be decisive.”

The conviction of Maria Ressa, CEO of Philippines website Rappler , and former researcher Reynaldo Santos for “cyber libel” is the first of a string of charges the Philippines authorities brought against this independent news organisation that has been successfully prosecuted. Current editor-at-large Marites Vitug warns her country is “losing its grip on democracy, courtesy of an autocratic president who is using state agencies to weaken the media”. Ms Vitug joins the panel as international condemnation grows of what the European Parliament’s Media Working Group this month described as an “ orchestrated campaign of legal harassment .”

President Duterte came to power in 2016 with a blood-curdling warning : “Just because you’re a journalist, you are not exempted from assassination, if you’re a son of a bitch.” Ten years on from the Ampatuan massacre that claimed the lives of 32 media workers, the Philippines is still considered one of the most dangerous places in the world to be a journalist.

“The Philippine media are under siege and the greatest threat to media freedom is President Duterte himself. He has broken the rule of law in the country, he doesn’t brook dissent. His rule is vengeful and punitive,” Ms Vutig comments.

“The recent passage of the Anti-Terror Act (during the pandemic) opens the floodgates for law enforcement authorities to tag perceived enemies of the state as ‘terrorists’ including journalists,” she added.

In Australia too, new national security laws are before parliament and come as a chill was sent through the media community by federal police raids targeting colleagues over public interest reportage that embarrassed the government. Search and seizure operations against the national broadcaster the ABC and the home of a major newspaper’s journalist saw charges recommended against one reporter. RSF reports Australia “used to be the regional model but is now characterised by its threats to the confidentiality of sources and to investigative journalism”.

On the panel is Professor Peter Greste, a foreign correspondent for 25 years with Reuters, CNN, BBC and Al-Jazeera and co-founder of the Alliance for Journalists Freedom . His reportage in Egypt saw him spend 400 days in jail and face court on terrorism charges in a case that was internationally condemned as a politically motivated show trial .

“In Australia, we have seen more than 80 separate pieces of national security legislation pass through the Commonwealth many of which seriously limit press freedom,” he said.

“The War on Terror has given governments the freedom to draft loosely-framed national security legislation and related technologies that they have then used to spy on journalists and their sources.

“The effect is to expose journalists to overbearing investigations, criminalising otherwise legitimate inquiries, and silencing their work.”

In Papua New Guinea last year there was a glimmer of hope with the installation of Prime Minister James Marape for greater media freedom after what RSF describes as almost a decade of “dictatorial tendencies marked by press freedom violations, including intimidation, direct threats, censorship, prosecutions and attempts to bribe journalists”.

However, Transparency International PNG (TIPNG) in its forthcoming Media Trends report, the “first to provide an objective basis to evaluate claims of whether the media in PNG are fair”, suggests little has changed.

Joining the panel is Scott Waide who is a PNG investigative journalist and Lae Bureau chief at commercial broadcaster EMTV . He has repeatedly stared down attempts to stifle his reporting. As a member of the Melanesia Media Freedom Forum (MMFF) he warns of a “dangerous downward trend” in PNG and the region.

“Corruption is normalised and legalised, politicians feel that government policy should not be questioned, and critical thinking is largely absent in public debate,” he said.

“Journalists are threatened, abused and ridiculed, editors, CEOs and board members are put under pressure, you are excluded from events or deliberately not informed. Politicians feel invincible. They want us to report the facts but not report the why and how.”

“As well as the steady exit of senior journalists, taking with them years of accumulated institutional knowledge, younger journalists leave after an average of five years, there is always a constant void that needs filling in newsrooms and (results in) the absence of critical debate driven by the media.”

Join us on July 16 (5 pm AEST) to hear more from our panel members and be part of this critical and very timely conversation. Register for the next Perspectives Asia Event .

Stefan Armbruster is SBS correspondent for Queensland and the Pacific. He is an Industry Fellow at the Griffith Asia Institute

Share this:

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Region-Australia

- Region-PNG and the Pacific

Please enter your details to receive articles as they are published.

Type your email…

Recent Posts

- Digital technologies vis- à-vis trade in Pacific island countries

- Warfare in the robotics age

- Leaving nothing to chance: Sustaining Pacific development beyond 2024

Our research focuses on the trade and business, politics, governance, security, economies and development of the Asia Pacific and their significance for Australia. Griffith University is committed to advancing Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) across the region.

Feedback | Privacy policy | Copyright matters | CRICOS Provider - 00233E | TEQSA – PRV12076

Gold Coast • Logan • Brisbane | Australia

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

A 'Fraught Time' For Press Freedom In The Philippines

Sheila S. Coronel

College students protest to defend press freedom in Manila on Wednesday, after the government cracked down on Rappler, an independent online news site. Noel Celis/AFP/Getty Images hide caption

College students protest to defend press freedom in Manila on Wednesday, after the government cracked down on Rappler, an independent online news site.

Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte does not like the press. Stung by critical media reporting, he has in the past months called some of the country's largest media organizations "bullshit," "garbage," "son of a bitch." Journalists, he said, have no shame. They are corrupt fabulists and hypocrites who "pretend to be the moral torch of the country."

But Duterte does not just get mad; he gets even. This week, the Philippine Securities and Exchange Commission revoked the corporate registration of Rappler , an online media startup that has reported aggressively on Duterte's troll army and police abuses in the government's war on drugs. If the order is confirmed by an appeals court, the company may have to shut down.

Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte, shown here on Dec. 20 at a ceremony marking the anniversary of the military, became president as the Philippine media were losing prestige and market power. Ted Aljibe/AFP/Getty Images hide caption

Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte, shown here on Dec. 20 at a ceremony marking the anniversary of the military, became president as the Philippine media were losing prestige and market power.

Threatening as this crackdown is, it's only one arm of a pincer-like assault on the press. Duterte is drawing from the Modern Autocrat's Field Guide to Information Control. The aim is complete encirclement so as to drown out critical and independent voices. Like Vladimir Putin, Turkey's Recip Tayyip Erdogan and Hungary's Viktor Orban, he has launched a two-pronged attack.

One prong is media muzzling through government regulation. In Russia, Turkey and Hungary, autocratic leaders have shut down critical news outlets or transferred their ownership to friendly proprietors. In all these countries, government regulators have hounded recalcitrant media owners with spurious allegations like tax evasion and failure to obtain licenses.

More insidiously, populist leaders have tried to de-legitimize independent and critical media by ridiculing their editorial standards and their claims to a moral high ground. The press, said Dutere , "throw[s] garbage at us ... [but] How about you? Are you also clean?"

Demonization by government — something President Trump also deploys against media outlets he dislikes — is just one tactic. The other is letting loose an army of trolls , bloggers on the state's payroll , propagandists and paid hacks who ensure the strongman's attacks against the press are amplified in newspaper columns and on the airwaves, on social media and fake news sites.

In 1972, when Ferdinand Marcos declared martial law, he closed down all newspapers and broadcast stations and hauled dozens of journalists to jail. When the presses and broadcast networks reopened, they were all owned by Marcos kin and cronies and were censored by the presidential palace. The flow of information was strictly controlled: There were only three daily newspapers and a limited number of TV and radio stations.

Employees of Rappler, an online news outfit known for its critical reporting on Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte, continued to work in their office in Manila on Tuesday. The Philippine Securities and Exchange Commission revoked Rappler's corporate registration this week. Aaron Favila/AP hide caption

Employees of Rappler, an online news outfit known for its critical reporting on Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte, continued to work in their office in Manila on Tuesday. The Philippine Securities and Exchange Commission revoked Rappler's corporate registration this week.

Duterte is an admirer of Marcos, but he is using a 21st century playbook for media control. The strategy is no longer restricting information flows, but flooding the information space with disinformation and propaganda while also attacking legitimate purveyors of the news.

Last year, the president launched blistering assaults against two news organizations that reported allegations he had stashed millions in secret bank accounts. As he turned up the heat, the owners of the Philippine Daily Inquirer , the country's second largest newspaper, announced they would sell the daily to a businessman chummy with the president. Duterte also tightened the screws on the top television network, ABS-CBN, threatening to block the renewal of its franchise and to sue its owners for failing to air campaign ads that he said he had already paid for.

Rappler was investigated supposedly because it violated the ban on foreign media ownership. The pioneering startup issued $1 million in securities, called Philippine depository receipts, to the Omidyar Network, the philanthropic arm of eBay founder Pierre Omidyar.

Other companies, including a giant telecommunications firm and two broadcast networks, have similar arrangements with foreign investors. But only Rappler's registration has been revoked — tellingly, six months after Duterte accused the news site of being U.S.-owned.

During the Marcos era, Filipino journalists and citizens used innovative ways to skirt censorship. There was a robust underground press and above-ground media used allegory and allusion to evade restrictions.

The new media landscape requires new strategies for ensuring that genuine news evades encirclement by poisoned information. More cautious news outlets have taken the path of self-preservation through self-censorship. Rappler, for one, has said it will not stand down, and it has the support of major journalist groups in the Philippines and overseas. In the past, journalists, with the support of outraged citizens, have successfully resisted gagging.

But the Philippine press has never been weaker. Media influence and market power soared after Marcos fell in a 1986 popular uprising. There was a hunger for news and uncensored information and crusading journalists and newspapers were feted for their role in the democracy movement. Before long, powerful families bought newspapers and broadcast networks, using their media clout to advance their interests. Sensationalism ruled in a crowded and competitive media market.

Like elsewhere, technology has disrupted the media business in the Philippines: Revenues have fallen, and audiences have moved online, gravitating toward Facebook, which has become the de facto news source for most Filipinos.

Duterte became president as the media were losing prestige and market power. He attacked the press where it was most vulnerable: His tirades against sensationalist journalists and elitist media owners resonated among many Filipinos.

This is a fraught time for the Philippine press. In the past, journalists and citizens have stood together to defend the right to know. They may do so again, but they need a clear vision, an ark that will see them through the Duterte era's deluge of disinformation.

Sheila S. Coronel (@sheilacoronel) is Director of the Toni Stabile Center for Investigative Journalism and Dean of Academic Affairs at the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism. She co-founded the Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism.

- rodrigo duterte

- press freedom

- Philippines

- Our Supporters

The Job Of Preserving Oahu’s Historic Sites Is Complicated By The Push For Development

Proposed Law Would Address ‘Terrible Impacts’ Of Unlicensed Animal Surgeries In Hawaii

Ben Lowenthal: The Surprising Persistence Of Conservatism In True Blue Hawaii

The Senate Just Killed Green’s Plan For A Climate Fee For Visitors

This State Agency Transformed Kakaako. Should It Do The Same For Lahaina?

- Special Projects

- Mobile Menu

Freedom Of The Press Is An Old Issue In The Philippines. What Will Marcos Jr. Do Now?

The fatal shooting of Filipino radio broadcaster Percival Mabasa in Manila earlier this month has heightened concerns that the media will remain under attack during the new administration of President Ferdinand Marcos Jr. in one of the most dangerous countries in the world for journalists.

The 63-year-old host of the “Lapid Fire” show was known for his sharp critiques of both Marcos Jr., the son of a dictator ousted in a pro-democracy uprising in 1986, and the previous president, Rodrigo Duterte, who oversaw a deadly crackdown on illegal drugs.

The Philippine police and a presidential task force on media security are still investigating the case but presume that the killing was work-related.

Mabasa, who used the broadcast name Percy Lapid, was the second j ournalist killed since Marcos Jr. took office at the end of June. According to the National Union of Journalists of the Philippines, nearly 200 journalists have been killed since the late Ferdinand Marcos was overthrown and went into exile in Hawaii in 1986.

Mabasa’s killing stood out because it took place in the capital of Manila, while most other attacks against journalists have been outside of the capital. Another Filipino radio journalist, Renato “Rey” Blanco, was killed last month in the Negros Oriental province in the central Philippines.

Mabasa was killed when two men on a motorcycle approached the vehicle he was driving and shot him twice in the head on Oct. 3 in suburban Las Pinas City, The Associated Press reported, adding that the attackers escaped.

He was on his way to work, his brother, Roy Mabasa said on social media.

LAST time I saw my brother #PercyLapid alive in person was about 2 weeks ago. Percy was ambushed Monday night while on his way to his #lapidfire studio in Las Piñas. I'll always remember him for his deep faith in God & his undying love for his country. #JusticeForPercyLapid pic.twitter.com/ZWwlW3XgkH — ROY MABASA (@roymabasa) October 5, 2022

Local and international advocacy organizations condemned the killing and the New York-based Committee to Protect Journalists called on Philippine authorities to bring the perpetrators to justice. The organization also said it had emailed Marcos Jr.’s office and the presidential task force for comment.

Decades of killings, institutional corruption, legal persecution, false labeling as communists or terrorists and disinformation campaigns have rendered the Philippines one of the most hazardous places for media workers. The Southeast Asian nation also is plagued by private armies controlled by powerful clans and weak law enforcement.

One of the worst journalist massacres occurred in 2009 when 32 reporters were killed in Maguindanao province. A decade passed before any of the killers faced justice .

Threats to the Philippine media received global attention when Maria Ressa, CEO of the online Filipino news platform Rappler, won the Nobel Peace Prize last year alongside Russian journalist Dmitry Andreyevich Muratov. She has since been fighting a cyber libel conviction in the Philippines .

Carlos Conde, head Philippines researcher for Human Rights Watch, said that over half of the journalists killed had worked in radio, a medium in which reporting and commentary blur together in efforts to stand out in an industry of competing voices. He said that demonization of the media was just one of the human rights challenges aggravated under Duterte’s term.

“The killing of journalists is not something that occurs in a vacuum,” he said in a phone interview from his hotel room in Geneva, where he attended the 51st session of the U.N. Human Rights Council on Oct. 5.

Attacks against journalists reflect the poor quality of law enforcement institutions in the country as well as widespread corruption, Conde said.

“It’s been so commonplace and nobody’s shocked anymore – they’ve been inured to the violence,” Conde said.

Meanwhile, social media has facilitated the faster and easier spread of false narratives by government officials, journalists and citizens alike. And so-called red-tagging — the practice of harassing, threatening or blacklisting somebody by accusing them of being a communist or a terrorist — has bled over from the Duterte era.

“Troll armies” in the service of politicians make powerful accusations that become magnified among people who can no longer discern between real and fake news, Conde said. The problem is exacerbated in radio and broadcast journalism because of the selling of air time to the highest bidders, who can say whatever they want.

“This distinction really needs to be highlighted, especially for people outside of the Philippines: the fact is that a lot of this disinformation is put out by those with money to do that. It’s not some organic thing that happens,” Conde said.

He said such disinformation campaigns contributed to Marcos Jr.’s victory over former Vice President Leni Robredo in the presidential election.

The escalation of international attention on the human rights struggle in the Philippines started when Duterte took office in 2016 and began his war on drugs that drew international condemnation for widespread human rights abuses.

“It could be many years before the attitude towards the media changes.” — Journalists’ Union Chair Jonathan de Santos

The new president has vowed that journalists would be protected under his administration, and he reiterated that commitment in a speech after Mabasa’s killing.