To read this content please select one of the options below:

Please note you do not have access to teaching notes, influencing factors of social media addiction: a systematic review.

Aslib Journal of Information Management

ISSN : 2050-3806

Article publication date: 5 September 2023

As an unhealthy dependence on social media platforms, social media addiction (SMA) has become increasingly commonplace in the digital era. The purpose of this paper is to provide a general overview of SMA research and develop a theoretical model that explains how different types of factors contribute to SMA.

Design/methodology/approach

Considering the nascent nature of this research area, this study conducted a systematic review to synthesize the burgeoning literature examining influencing factors of SMA. Based on a comprehensive literature search and screening process, 84 articles were included in the final sample.

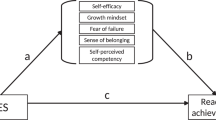

Analyses showed that antecedents of SMA can be classified into three conceptual levels: individual, environmental and platform. The authors further proposed a theoretical framework to explain the underlying mechanisms behind the relationships amongst different types of variables.

Originality/value

The contributions of this review are two-fold. First, it used a systematic and rigorous approach to summarize the empirical landscape of SMA research, providing theoretical insights and future research directions in this area. Second, the findings could help social media service providers and health professionals propose relevant intervention strategies to mitigate SMA.

- Social media addiction

- Influencing factors

- Literature review

- Theoretical framework

- Addiction mechanism

- Stimulus-organism-response framework

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the editor and reviewers whose constructive comments have improved the quality of this manuscript considerably. This research was supported and funded by the following grants: National Social Science Foundation of China (21&ZD334) and the Science Fund for Creative Research Groups of NSFC (71921002).

Liang, M. , Duan, Q. , Liu, J. , Wang, X. and Zheng, H. (2023), "Influencing factors of social media addiction: a systematic review", Aslib Journal of Information Management , Vol. ahead-of-print No. ahead-of-print. https://doi.org/10.1108/AJIM-10-2022-0476

Emerald Publishing Limited

Copyright © 2023, Emerald Publishing Limited

Related articles

All feedback is valuable.

Please share your general feedback

Report an issue or find answers to frequently asked questions

Contact Customer Support

Systematic Review on Social Media Addiction: Bibliometric Analysis Application

16 Pages Posted: 19 Aug 2024 Publication Status: Under Review

Thanh Ngoc Dan Nguyen

Ho Chi Minh City Open University

Hao Yen Tran

Social media addiction has become a prevalent issue, affecting the psychological and social behaviors of individuals globally. This study systematically reviews 37 existing literature to identify key factors influencing social media addiction, its consequences on life satisfaction, and potential areas for future research. By employing bibliometric analysis, the study analyzes trends and gaps in research from 2014 to 2023, providing a comprehensive understanding of social media addiction and offering recommendations for further investigation.

Keywords: Social media addiction, life satisfaction, bibliometric analysis, well-being

Suggested Citation: Suggested Citation

Thanh Ngoc Dan Nguyen (Contact Author)

Ho chi minh city open university ( email ), do you have a job opening that you would like to promote on ssrn, paper statistics, related ejournals, data science, data analytics & informatics ejournal.

Subscribe to this fee journal for more curated articles on this topic

Information Policy, Ethics, Access & Use eJournal

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- My Bibliography

- Collections

- Citation manager

Save citation to file

Email citation, add to collections.

- Create a new collection

- Add to an existing collection

Add to My Bibliography

Your saved search, create a file for external citation management software, your rss feed.

- Search in PubMed

- Search in NLM Catalog

- Add to Search

A review of theories and models applied in studies of social media addiction and implications for future research

Affiliations.

- 1 School of Information, The University of Texas at Austin, USA. Electronic address: [email protected].

- 2 School of Information, The University of Texas at Austin, USA. Electronic address: [email protected].

- PMID: 33268185

- DOI: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2020.106699

With the increasing use of social media, the addictive use of this new technology also grows. Previous studies found that addictive social media use is associated with negative consequences such as reduced productivity, unhealthy social relationships, and reduced life-satisfaction. However, a holistic theoretical understanding of how social media addiction develops is still lacking, which impedes practical research that aims at designing educational and other intervention programs to prevent social media addiction. In this study, we reviewed 25 distinct theories/models that guided the research design of 55 empirical studies of social media addiction to identify theoretical perspectives and constructs that have been examined to explain the development of social media addiction. Limitations of the existing theoretical frameworks were identified, and future research areas are proposed.

Keywords: Facebook addiction; Internet addiction; Literature review; Problematic use; Social media addiction; Theoretical framework.

Copyright © 2020 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

PubMed Disclaimer

Similar articles

- Scaling Up Research on Drug Abuse and Addiction Through Social Media Big Data. Kim SJ, Marsch LA, Hancock JT, Das AK. Kim SJ, et al. J Med Internet Res. 2017 Oct 31;19(10):e353. doi: 10.2196/jmir.6426. J Med Internet Res. 2017. PMID: 29089287 Free PMC article.

- Predictors of Problematic Social Media Use: Personality and Life-Position Indicators. Sheldon P, Antony MG, Sykes B. Sheldon P, et al. Psychol Rep. 2021 Jun;124(3):1110-1133. doi: 10.1177/0033294120934706. Epub 2020 Jun 24. Psychol Rep. 2021. PMID: 32580682

- Empirical Relationships between Problematic Alcohol Use and a Problematic Use of Video Games, Social Media and the Internet and Their Associations to Mental Health in Adolescence. Wartberg L, Kammerl R. Wartberg L, et al. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020 Aug 21;17(17):6098. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17176098. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020. PMID: 32825700 Free PMC article.

- The "Vicious Circle of addictive Social Media Use and Mental Health" Model. Brailovskaia J. Brailovskaia J. Acta Psychol (Amst). 2024 Jul;247:104306. doi: 10.1016/j.actpsy.2024.104306. Epub 2024 May 11. Acta Psychol (Amst). 2024. PMID: 38735249 Review.

- Prevalence of social media addiction across 32 nations: Meta-analysis with subgroup analysis of classification schemes and cultural values. Cheng C, Lau YC, Chan L, Luk JW. Cheng C, et al. Addict Behav. 2021 Jun;117:106845. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2021.106845. Epub 2021 Jan 26. Addict Behav. 2021. PMID: 33550200 Review.

- Social Media Use, Emotional Investment, Self-Control Failure, and Addiction in Relation to Mental and Sleep Health in Hispanic University Emerging Adults. Garcia MA, Cooper TV. Garcia MA, et al. Psychiatr Q. 2024 Aug 22. doi: 10.1007/s11126-024-10085-8. Online ahead of print. Psychiatr Q. 2024. PMID: 39172319

- Scrolling for fun or to cope? Associations between social media motives and social media disorder symptoms in adolescents and young adults. Thorell LB, Autenrieth M, Riccardi A, Burén J, Nutley SB. Thorell LB, et al. Front Psychol. 2024 Aug 2;15:1437109. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1437109. eCollection 2024. Front Psychol. 2024. PMID: 39156819 Free PMC article.

- The enduring echoes of juvenile bullying: the role of self-esteem and loneliness in the relationship between bullying and social media addiction across generations X, Y, Z. Lissitsa S, Kagan M. Lissitsa S, et al. Front Psychol. 2024 Aug 2;15:1446000. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1446000. eCollection 2024. Front Psychol. 2024. PMID: 39156810 Free PMC article.

- A cross-lagged analysis of the relationship between short video overuse behavior and depression among college students. Zhang D, Yang Y, Guan M. Zhang D, et al. Front Psychol. 2024 Jul 17;15:1345076. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1345076. eCollection 2024. Front Psychol. 2024. PMID: 39086426 Free PMC article.

- Adolescent Social Media Use through a Self-Determination Theory Lens: A Systematic Scoping Review. West M, Rice S, Vella-Brodrick D. West M, et al. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2024 Jun 30;21(7):862. doi: 10.3390/ijerph21070862. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2024. PMID: 39063439 Free PMC article. Review.

Publication types

- Search in MeSH

Related information

Linkout - more resources, full text sources.

- Elsevier Science

Other Literature Sources

- scite Smart Citations

- Citation Manager

NCBI Literature Resources

MeSH PMC Bookshelf Disclaimer

The PubMed wordmark and PubMed logo are registered trademarks of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Unauthorized use of these marks is strictly prohibited.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 28 August 2024

Academic self-discipline as a mediating variable in the relationship between social media addiction and academic achievement: mixed methodology

- Özge Erduran Tekin ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-4052-1914 1

Humanities and Social Sciences Communications volume 11 , Article number: 1096 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

Metrics details

- Health humanities

This study examines the mediating role of academic self-discipline in the effect of university students’ social media addictions on academic achievement. The study sample consisted of 520 university students with a daily social media usage time of four hours or more, selected using the convenience sampling method. Data were collected from 36 cities in Turkey. Bergen Social Media Addiction Scale, Academic Self-discipline Scale, Personal Information Form, and Semi-structured Interview Form were used as data collection tools. The relationships between variables were analyzed using Pearson correlation analysis and regression analysis using Process Macro (model 4). In the regression analysis, mediation was tested with the Bootstrap technique. According to the analysis results, social media addiction predicts academic achievement. In addition, academic self-discipline has a partial mediating role in the relationship between social media addiction and academic achievement. As a result of the content analysis of the interviews, three themes were reached: “The Reasons for Social Media Addiction, The Effect of Social Media Addiction on Academic Achievement, and The Role of Academic Self-discipline in the Effect of Social Media Addiction on Academic Achievement.” The qualitative results obtained supported the quantitative results. Based on all these, suggestions were made based on increasing academic self-discipline to prevent social media addiction from affecting academic achievement.

Similar content being viewed by others

Different motivation, different achievements: the relationship of motivation and dedication to academic pursuits with final grades among Jewish and Arab undergraduates studying together

Self-perceptions as mechanisms of achievement inequality: evidence across 70 countries

Bidirectional longitudinal associations of mental health with academic performance in adolescents: DADOS study

Introduction.

Excessive and misuse of social media is a crucial problem for the young age group, and social media addiction is quite common among university students (Chen and Peng, 2008 ; Ehrenberg et al. 2008 ; Kalaitzaki et al. 2020 ). When the reasons that push university students to use social media intensively are analyzed; the reasons such as communicating with others more easily, having fun, getting away from disturbing experiences and emotional situations and spending time are in the first place (Cohen et al. 2019 ; Özdemir, 2019 ; Zachos et al. 2018 ). Social media addiction has many negative consequences, including academic failure (Kaplan and Özdemir, 2023 ; Masood et al. 2020 ; Shi et al. 2020 ; Zhao, 2023 ). Problematic social media users are unable to control themselves, at this very point self-discipline may be important in preventing social media addiction (Li et al. 2010 ; Zahrai et al. 2022 ). According to research, self-discipline affects problematic internet use behaviors more than any other variable (Kim et al. 2007 ; Li et al. 2013 ). On the contrary, no study in the literature examines the mediating role of academic self-discipline, which represents the sustainability of self-discipline in academic subjects, in the relationship between social media addiction and academic achievement.

Relationship between social media addiction and academic achievement

Academic achievement is shaped by very comprehensive variables and is challenging to systematize in a specific model (Thomas and Maree, 2021 ; Whelan et al. 2020 ). However, the reflection of generally learned knowledge and skills in students’ examination performances is accepted as a critical indicator of academic achievement. Given that academic achievement significantly affects the student’s development in future processes, it is considered significant to examine what factors increase and decrease academic achievement (Shi and Qu, 2022 ).

It is important to examine the relationship between social media addiction, which is accepted as one of the problematic behaviors, and academic achievement (Zhao, 2023 ). Social media is an inclusive concept that describes the social networking sites and messaging applications that young people frequently use (Wartberg et al. 2020 ). Social media addiction, which is also accepted as an impulse control disorder, consists of problematic behaviors that manifest themselves as an individual’s irresistible desire for social media applications and loss of willpower, neglecting work, relationships, and daily routines due to intensive social media use (Andreassen and Pallesen, 2014 ; Young, 1996 ). Social media use has both positive and negative effects from an academic perspective. Social media can facilitate the exchange of information by connecting students and classrooms, provide a personalized learning environment, address different learning domains, and improve learning motivation (Arquero and Romero-Frı́as, 2013 ; Gazibara et al. 2020 ; Hrastinski, 2008 ; Kasperski and Blau, 2020 ). Therefore, the findings suggest that social media contributes to learning processes when used correctly (Jain et al. 2012 ). In addition, studies show that excessive and improper use of social media applications causes a decrease in academic achievement (Masood et al. 2020 ; Wu and Cheng, 2019 ). Social media negatively affects academic achievement because it distracts attention, causes procrastination, and reduces the time allocated to lessons by causing time loss (Junco, 2012 ; O’Keeffe et al. 2011 ). On the other hand, the self-control levels of individuals may be effective in preventing behaviors, such as spending a much longer time on social media applications than normal usage times and often not being aware of this situation and postponing daily tasks that need to be performed during this time (Diker and Taşdelen, 2017 ; Tutgun-Ünal and Deniz, 2015 ; Zahrai et al. 2022 ).

The mediating role of academic self-discipline

Behavioral theories try to explain the limitations of self-control, and the Uses and Gratifications Theory defines the lack of self-control as the inability to neglect smaller and momentarily pleasurable rewards to achieve larger goals (Katz et al. 1973 ). The conscious development and maintenance of self-control is defined as self-discipline (Bear, 2009 ). However, many disciplines use the concept of self-discipline by, it has also been expressed as self-regulation, self-control, self-motivation, and willpower. Duckworth and Seligman ( 2006 ) used the concepts of self-discipline and self-control interchangeably and defined self-discipline as a conscious and sustainable effort to suppress momentary desires to achieve planned goals. Therefore, it can be said that the concept of self-discipline, which refers to taking and maintaining responsibility, refers to the continuity in the ability of individuals to postpone their wants consciously and needs to achieve their long-term goals (Duckworth and Seligman, 2006 ). Academic self-discipline, which is the equivalent of self-discipline in the academic field, is defined as the ability to stay away from various stimuli by controlling oneself to achieve one’s academic goals, to focus one’s attention on the subject to be studied, and to maintain a certain working order in a planned manner (Pustika, 2020 ). By the definition, the scale used to measure academic self-discipline in this study has two sub-dimensions: Planned study and attention. Therefore, academic self-discipline was analyzed in this study, especially within the scope of these two dimensions.

Concentration is the ability to maintain one’s attention despite being bored, tired, or other negative emotional states by focusing sufficiently on the subject one is working on (Taylor et al. 2002 ). Considering that one of the dimensions of academic self-discipline is concentration, it is assumed that increased academic self-discipline may be effective in academic achievement. Planning is another dimension considered in terms of academic self-discipline (Cao and Cao, 2004 ). When considered within the scope of self-discipline theory, planning also includes perseverance and self-motivation and provides convenience in achieving individual goals and fulfilling tasks (Shi and Qu, 2022 ). Students can achieve their goals for better performance (Malte et al. 2009 ). In a study, it was observed that there was no significant difference between students with high and low academic achievement in terms of self-discipline. However, there were differences in various dimensions of time management, including planning (Fang and Wang, 2003 ). Unlike self-discipline, it can be meaningful to examine academic self-discipline in the axis of planning and attention separately and examine the relationship between academic self-discipline and academic achievement in depth through both quantitative and qualitative data to make more concrete suggestions to increase academic achievement.

The present study

Self-discipline, which consists of three dimensions: concentration, impulse control, and delayed gratification, allows one to consider the possible advantages and disadvantages of the action before taking the action. Thus, it helps the person to stay away from risky behaviors and postpone immediate pleasures by being patient for long-term gains (Taylor et al. 2002 ). Therefore, self-discipline is recognized as one of the main factors affecting students’ academic achievement (Liang et al. 2020 ; Van Endert, 2021 ). Students with insufficient self-discipline face academic failure (Tominey and McClelland, 2011 ). Although studies have shown a relationship between self-discipline and academic achievement (Duckworth et al. 2019 ), it is still unclear how self-control and self-discipline affect academic achievement (Shi and Qu, 2022 ). In addition, it requires self-discipline to focus on academic tasks by moving away from harmful internet or social media use that causes time loss (Mbaluka, 2017 ). Self-discipline is important in controlling behavioral addiction types, such as social media addiction. In addition, considering that self-discipline significantly affects academic achievement (Duckworth and Carlson, 2013 ; Zhao and Kuo, 2015 ), it suggests that high academic self-discipline may have a protective role in the negative effects of impulse behavior disorders, such as social media addiction, on academic achievement. Although there are studies examining the relationship between self-control, self-discipline, and social media addiction (Koç et al. 2023 ; Sağar, 2021 ; Zahrai et al. 2022 ), there is no study investigating the mediating role of academic self-discipline in the relationship between social media addiction and academic achievement with a mixed method. Based on all these, this study aimed to examine the mediating role of academic self-discipline in the relationship between university students’ social media addictions and their academic achievement. The quantitative and qualitative sub-objectives created within the scope of this purpose are as follows.

Quantitative sub-objectives:

-Is there a significant relationship between social media addiction, academic achievement, and academic self-discipline in university students?

Is there a mediating role of academic self-discipline in the effect of social media addiction on academic achievement in university students?

Qualitative sub-objectives:

What are the common themes related to university students’ experiences of social media addiction, academic achievement, and academic self-discipline?

How do academic self-discipline experiences mediate the relationship between university students’ social media addictions and academic achievement?

This study was designed as an exploratory sequential mixed design. With mixed methods, a weak or missing aspect of one of the quantitative and qualitative methods can be covered by the strengths of the other (Creswell and Plano Clark, 2018 ). The calculated regression coefficients guide the examination of the relationship between social media addiction and academic achievement and the mediating role of academic self-discipline. However, to better understand the effect of social media addiction on academic achievement and make academic self-discipline-based intervention suggestions, a mixed-method approach was used in this study, considering that it is critical to collect data from students through their opinions.

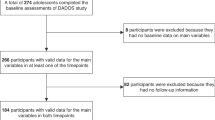

Participants

The sample of this study consisted of 520 university senior students ranging from 22 to 27 ( \(\bar{x}\) = 24.43; Sd = 1.49) studying in various departments (Psychology, Law, Engineering, and Teaching) at state universities in Turkey in the 2023–2024 academic year. Data were collected from 36 cities in Turkey. Considering the ease of accessing the data, the convenience sampling method was preferred. In the convenience sampling method, due to the limitations in terms of the labor force and time, the sample is selected from easily accessible and applicable units (Büyüköztürk et al. 2014 ). Firstly, data were collected from 873 students through Google Forms. Then, the analyses continued with the data obtained from 520 people who stated that their daily social media usage time was four hours or more. It was aimed to provide more reliable information about the effect of social media addiction on the academic achievement of the 520 students, 299 (57.5%) were female, and 221 (42.5%) were male. Of the participants, 307 (57.9%) defined their socioeconomic level as low, 135 (26%) defined their socioeconomic level as medium, and 84 (16.2%) defined their socioeconomic level as high. The students wrote the transcript grade median, which consisted of the calculation of the end-of-term grades of the courses they had taken until the last year. To obtain more comprehensive information about their academic achievements throughout their university life, the sample consisted of final-year university students. In this context, 182 (35%) of the students who participated in the study had general weighted grade point averages between 1.00 and 2.00, 179 (34.4%) between 2.00 and 3.00, and 159 (30.6%) between 3.00 and 4.00.

In the qualitative phase of this study, 20 volunteer students were selected by purposive sampling method from the students who participated in the quantitative data collection phase. To ensure maximum diversity, male and female students studying in different departments were selected and interviews were conducted with students with high levels of social media addiction to obtain in-depth information. In this context, nine of the students aged between 22 and 25 were male and 11 were female. Three of them were law students, four were teachers, four were psychology students and nine were final-year students studying in various engineering departments.

Data collection tools

Bergen Social Media Addiction Scale developed by Andreassen et al. ( 2016 ) was adapted to Turkish culture by Demirci ( 2019 ). The scale was constructed to fulfill the basic addiction criteria of mental preoccupation, mood change, tolerance, withdrawal, conflict, and failed quit attempts. The scale, graded on a five-point Likert scale, consists of six items. The scores that can be obtained from the scale vary between 6 and 30. In the adaptation study, the Cronbach’s alpha internal consistency coefficient of the scale was calculated as 0.83 and the test-retest reliability coefficient was calculated as 0.83. The suitability of the scale for use in this study was examined by reliability analysis, and exploratory factor analysis was applied. In this context, the KMO value was found to be 0.89 and the Barlett Sphericity test p < 0.000, and it was accepted that the data set was suitable for factor analysis. The unidimensional structure of the scale (explaining 64% of the total variance) was also confirmed in this data set. The fact that the factor loadings of the scale ranged from 0.77 to 0.85 indicates that the items of the scale are compatible with the structure in which it is located. In addition, the Cronbach’s alpha reliability coefficient of the scale was calculated as 0.89 in this study. Based on all these, it can be said that it is appropriate to use the scale within the scope of this study. Some of the items that make up the Bergen Social Media Addiction Scale are as follows:

Have you felt the urge to use social media more and more?

Has using social media too much negatively affected your work/studies?

Would you be uncomfortable or distressed if you were banned from using social media?

The Academic Self-discipline Scale was developed by Şal ( 2022 ) to measure the academic self-discipline levels of university students and adapted to Turkish culture by Erduran Tekin and Şal ( 2023 ). The scale, which consists of eighteen items, has two sub-dimensions “planned work” and “attention.” The scale is scored on a five-point Likert scale and items 6, 7, and 16 are evaluated as reverse. While the scores obtained from the scale vary between 18 and 90, an increase in the scores means an increase in academic self-discipline. In the adaptation study, the structure consisting of two sub-dimensions was confirmed, and the goodness of fit indices of the model indicated an acceptable fit. In the adaptation study, Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of the Academic Self-discipline Scale was calculated as 0.86. The suitability of the scale for use in this study was examined by reliability analysis, and exploratory factor analysis was applied. In this context, the KMO value was found to be 0.87 and the Barlett Sphericity test p < 0.000, and the data set was accepted as suitable for factor analysis. The two-dimensional structure of the scale (explaining 40% of the total variance) was also confirmed in this data set. The factor loadings of the scale ranged from 0.39 to 0.74, indicating that the items belonging to the scale are compatible with the structure in which it is located. In addition, the Cronbach’s alpha reliability coefficient of the scale was calculated as 0.85 in this study. Based on all these, it can be said that it is appropriate to use the scale within the scope of this study. Some of the items that make up the Academic Self-discipline Scale are as follows:

I have my schedule where I plan my study time.

I organize my study environment so that there are no distractions.

If I have planned to study, I can refuse to hang out with my best friend.”

The participants were asked to fill out the Personal Information Form. The form includes sections for age, gender, city of residence, and graduation grades. The academic achievements of the participants were examined based on the General Weighted Grade Point Average (GPA) written on the last semester’s transcript from the undergraduate program they studied. Those with GPAs between 1.00 and 2.00 were considered low academic achievers (2.00 was considered low academic achievement), and those with GPAs between 2.01 and 3.00 were considered medium academic achievers (3.00 was considered medium academic achievement). Those with GPAs between 3.01 and 4.00 were considered high academic achievers.

In the qualitative dimension of the study, semi-structured interview forms created by the researcher in this study were used. These forms were prepared based on the findings obtained by analyzing the quantitative data and researching the literature. After the forms were examined by two expert lecturers, a pilot application was carried out with a student on the comprehensibility of the questions, and the final version was given after the necessary corrections. While one of the most basic ways to ensure validity in qualitative research is the accuracy and detailed reporting of the categories and interpretations obtained, reliability is to minimize the difference in the interpretation of data by different experts (Büyüköztürk et al. 2014 ; Yıldırım and Şimşek, 2019 ). Thus, two academic members who were experts in their fields were consulted during the data interpretation process. The questions in the interview form are as follows:

What are the things that cause you to spend a lot of time on social media tools during the day?

How do you think spending too much time on social media tools affects your academic achievement?

Do you have academic self-discipline? How do you evaluate yourself?

Do you work in a planned way? How do you think working in a planned way affects academic achievement?

Do you ever get distracted while studying because of social media tools? If yes, what measures do you take to prevent social media tools from distracting you while studying?

What do you think you need to improve your academic achievement?

What should happen so that social media does not affect your academic achievement?

Data collection

Considering the ease of access to the data in the present study, the data were collected online using Google Forms. All ethical rules required by scientific research were followed in data collection. Ethics committee approval dated 23.01.2024 and numbered E-35592990-050.01.04-3222142 was obtained from the National Defense University Scientific Research and Publication Ethics Board for the study.

To examine the suitability of the data for parametric tests, kurtosis, skewness, and Z score analyses were performed (Schumacker and Tomek, 2013 ). Multivariate outliers in the data set were analyzed by calculating the Mahalanobis distance. Skewness and kurtosis values were re-analyzed and presented in Table 1 , and it was assumed that the data were normally distributed. In addition to descriptive analyses in which values, such as arithmetic mean and standard deviation, were calculated, ANOVA and t -test analyses were used to determine differences, and correlation analysis was used to determine the relationships between variables. The presence of multicollinearity, one of the prerequisites for regression analysis, was examined through variance inflation factors (VIF) and tolerance values (TV) of the variables in the model. If VIF ≥ 10 and TV ≤ 0.10, the multicollinearity problem is mentioned and the VIF values of the variables in this model are 2.23, and TV values are 0.45, and there is no multicollinearity problem. In this study, the mediating role of academic self-discipline in the relationship between social media addiction and academic achievement was analyzed with the regression of the Bootstrapping Technique (Hayes, 2017 ). Analyses were conducted with SPSS 26 PROCESS programs.

The “content analysis” method was preferred when analyzing qualitative data. With content analysis, the data obtained are conceptualized and organized in a way to be understood, and themes are created (Yıldırım and Şimşek, 2019 ). Content analysis aims to collect similar data collected through interviews under certain themes and to put these themes into a regular format. Firstly, the data obtained from 20 interviews were transferred to the computer environment in writing. A total of 62 pages of data were obtained from the interviews. Twenty interview data were recorded with student codes (e.g., P1, P2, P3, P4, and P5). Then, these organized data were regularised with MAXQDA 2020 software. For the analysis, the data were read repeatedly and analyzed within the scope of the research questions. The themes obtained were coded by two more academicians except the researcher. The coding reliability percentage was calculated using the formula “Agreement/(Agreement + Disagreement)” suggested by Miles and Huberman ( 1994 ). Coding reliability above 80% (Miles and Huberman, 1994 ), the lowest recommended percentage of agreement, was achieved, and the reliability was calculated as 90%. In cases where consensus could not be reached on the codes, participant confirmation was used to build consensus and increase reliability. The data obtained were given systematically according to the research questions in the findings section and supported with direct quotations to increase credibility.

Pearson analysis

Within the scope of the first sub-objective of this study, the skewness and kurtosis values of the social media addiction, academic achievement, and academic self-discipline scale scores and the correlation analysis results examining the relationships between the variables are presented in Table 1 .

Considering the data obtained from this study, it can be said that the skewness and kurtosis values are in the range of +−2 and the data have a normal distribution (George and Mallery, 2019 ). As a result of the analyses, it was seen that the social media addiction scores ( \(\overline{{\boldsymbol{x}}}\) = 15.67) of the data constituting the study group were above the average. Considering the relationship between the variables of this study, as seen in Table 1 , there was a negative and highly significant relationship between social media addiction and academic achievement ( r = −0.63, p < 0.01) and a negative and highly significant relationship between social media addiction and academic self-discipline ( r = −0.74, p < 0.01). When the relationship between academic achievement and academic self-discipline was analyzed, it was seen that there was a positive and highly significant relationship ( r = 0.60, p < 0.01). The findings suggest that as social media addiction increases, academic achievement and academic self-discipline decrease, and as academic self-discipline increases, academic achievement increases.

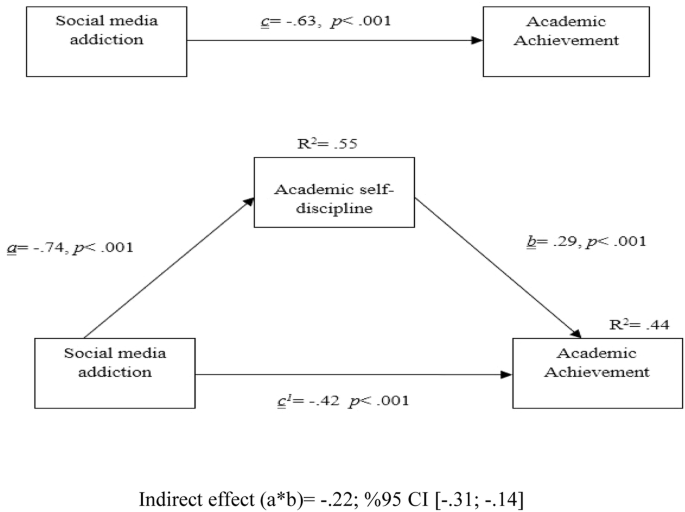

Results of mediation analysis

Within the scope of the second sub-objective of this study, the mediating role of academic self-discipline in the effect of social media addiction on academic achievement was analyzed using the Regression-based Bootstrapping Technique. In the analyses, 1000 bootstrap sampling was used and the estimates were evaluated at 95% confidence intervals reflecting the results adjusted for bias error. The model used for the mediation role was designed according to Model 4 proposed by Hayes ( 2017 ) in the presence of one independent, one dependent, and one mediator variable. The model is shown in Fig. 1 , and the analysis results of the mediation of academic self-discipline in the effect of social media addiction on academic achievement are presented in Table 2 :

Social media addiction predicts academic achievement through academic self-discipline [ R 2 = 0.44; F (2-519) = 203.530; p < 0.001].

As shown in Fig. 1 , social media addiction directly predicted academic self-discipline negatively ( a = −0.74; p < 0.001). Likewise, it was seen that academic self-discipline directly predicted academic achievement positively ( b = 0.29; p < 0.001). In addition, social media addiction directly predicted academic achievement negatively ( c = −0.63; p < 0.001). When academic self-discipline, the mediating variable, was included in the model, it was observed that this effect was c 1 = −0.42 and the value was still significant.

There was a partial mediation effect since the coefficient resulting from the inclusion of mediator variables in the model was still a significant coefficient and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for the significance of the indirect effects of partial mediation determined in the model are given in Table 2 .

It was understood that the partial mediation model was significant [ F (2-519) = 203.530, p < 0.001]. Social media addiction and academic self-discipline explained 44% of the variance in academic achievement (Table 2 ). In the mediation analysis using the bootstrapping technique, for the hypothesis of this study to be confirmed, the 95% confidence interval (CI) values obtained from the analysis should not contain a zero (0) value to support the research hypothesis (Gürbüz, 2019 ). The mediating role of academic self-discipline in the effect of social media addiction on academic achievement was significant (Bootstrap Coefficient = −0.22, 95% CI [−0.31; −0.14]), and these confidence intervals did not include any zero (0) point.

Qualitative analysis results

Table 3 lists the codes formed as a result of question-based analyses of the data collected from semi-structured interviews with students.

The codes obtained as a result of the analysis of semi-structured interviews conducted to examine the mediating role of academic self-discipline in the effect of university students’ social media addictions on their academic achievement are brought together in three themes and presented in Table 4 .

The quotations related to the most frequently repeated codes explaining the “Reasons for social media addiction” which constitutes Theme 1, are given below:

Desire to receive news “ When I don’t use social media tools, such as Twitter and Instagram, I miss the current news. There is a new event every minute in our country and I see many things on those platforms that I cannot see on television. Therefore, I find myself constantly looking at Twitter and Instagram (P4).”

Entertainment and relaxation “ Life is already hard and boring. At the moment, if you want to do something outside, everything is expensive. Even going to a cinema is incredibly costly for a student. In this case, social media applications are the place where there is content that relaxes, entertains, and makes you laugh at a cheap price (P17).”

Communicating with others “ Social media tools are as much a part of our body as our hands and feet. Instagram is the main way I communicate with other people, my friends, my date. For example, I always check Instagram to see what stories he has posted . (P9).”

The quotations related to the most frequently repeated codes explaining “The effect of social media addiction on academic achievement”, which constitutes Theme 2, are given below:

Loss of time “ I sit at my desk to study, and then a notification comes. I pick up my phone, thinking I’ll check it for a minute, but that’s not the case. I find myself constantly scrolling through posts and watching meaningless videos. This creates an incredible waste of time. I realize that hours have passed, but I haven’t studied at all because I was looking at Instagram or Twitter (P20).”

Inability to pay attention to the lessons, “ My mind stays on social media tools and I can’t concentrate on my lessons. I’m always looking at who went where and what story they shared. Then I started to envy people’s virtual happiness even though I knew it was not real. I can’t concentrate on my lessons thinking about all these things (P11).”

Inability to work regularly “ I am preparing a full study plan, I start, and I say I will take a 10 min break. In the meantime, I look at social media applications, 10 min has become 40 min. I say it’s okay and start over, but it’s the same again. Even if I work regularly one day, I cannot work regularly the next day. This cycle repeats itself (P1).”

The quotations related to the most frequently repeated codes explaining Theme 3, “The role of academic self-discipline in the effect of social media addiction on academic achievement” are given below:

To be disciplined “ As long as I am disciplined and can control myself, I can stay away from social media tools. Of course, one of the biggest benefits of this is my academic achievement . As I continue to control myself, use social media tools less, and stay away from them while studying, my attention and interest in the lesson increases. I can be more successful (P17).”

To focus on lessons “ Social media tools are a very serious stimulant. At least while studying, it is very useful to take the phone out of the room, and if the computer is open, it is very useful to keep only the file being studied open without opening different tabs. As usage is limited, study time remains. In this case, it allows us to focus more on the lessons and not pay attention to unnecessary stimuli (P13).”

Adhering to the work plan “ When I work more regularly, when I do not pay attention to other things even for a short time during the study and, I can follow my study program prepared for me, this makes me more successful (P6).”

This study aimed to examine the mediating role of academic self-discipline in the relationship between social media addiction and the academic achievement of university students in Turkey. In this context, the first sub-objective of the present research is to examine the relationship between social media addiction, academic achievement, and academic self-discipline. There is a significant negative relationship between social media addiction and academic achievement. When the relationship between academic self-discipline and academic achievement is analyzed, there is a significant positive relationship. Accordingly, as social media addiction increases, academic achievement and academic self-discipline decrease, and as academic self-discipline increases, academic achievement increases. The results obtained from this study are consistent with studies showing that social media addiction negatively affects academic achievement (Kaplan and Özdemir, 2023 ; Masood et al. 2020 ; Shi et al. 2020 ; Zhao, 2023 ).

The second sub-objective of this study is to examine the mediating role of academic self-discipline in the relationship between university students’ social media addictions and academic achievement. It was found that social media addiction and academic self-discipline explained 44% of the variance in academic achievement. The mediating role of academic self-discipline in the effect of social media addiction on academic achievement was significant. To determine the appropriate preventive and intervention mental health services that can be offered to university students, it is important to examine the variables that may mediate the relationship between social media addiction and academic achievement when the studies conducted in the literature are examined, seen that self-control and self-discipline are related to student’s academic achievement (Duckworth and Carlson, 2013 ; Liang et al. 2020 ; Mbaluka, 2017 ; van Endert, 2021 ; Zhao and Kuo, 2015 ). The themes obtained within the scope of the third and fourth sub-objectives of the research provide information about the causes of social media addiction, how social media addiction affects academic achievement, and what is the mediating role of academic self-discipline in this effect. When the literature is examined, similar to the results obtained from this study, social media addiction negatively affects academic achievement (Zhao, 2023 ), self-discipline significantly predicts academic achievement positively (Lin, 2021 ), and there are negative relationships between self-control and problematic social media use (Wu et al. 2013 ). Ning and Inan ( 2023 ) examined the mediating role of self-control in the effect of social media addiction on academic success. They concluded that self-control has a mediating role in the relationship between social media addiction and academic success, similar to the results obtained from this study. In another study conducted by Putri et al. ( 2022 ) with university students, it was concluded that high self-discipline reduces social media use. According to the same study, although there is no direct relationship between social media use and academic success, academic success is associated with higher self-control (Putri et al. 2022 ). According to Lindner et al. ( 2017 ), students with high self-control show higher attention skills, are more motivated to fulfill their responsibilities, and have higher academic achievement. In a study examining the mediating role of self-discipline in the relationship between cognitive ability and academic success, it was concluded that the mediating role of self-discipline is significant, and planning is a moderating variable in this relationship (Shi and Qu, 2022 ).

According to the qualitative analysis results, university students exhibit social media addiction behaviors for various reasons such as entertainment, relaxation, receiving news, communicating with others, and habit. These results are consistent with other studies in the literature (Cohen et al. 2019 ; Özdemir, 2019 ; Zachos et al. 2018 ). As a result of the interviews, social media use causes a waste of time, prevents students from devoting themselves to lessons and regular study, and increases their reluctance to study. They have difficulty controlling themselves in terms of social media use, which can be considered the negative effects of social media. According to the students, for social media addiction not to affect academic achievement, they should work in a planned manner, use time effectively, remove distracting stimuli from the environment while studying, pay attention to the lessons, continue their study activities in a disciplined manner, improve their self-control, and follow their study plans continuously. These results support other studies emphasizing the impact of attention, planned study, and time management on academic success (Cao and Cao, 2004 ; Shi and Qu, 2022 ; Taylor et al. 2002 ). Based on all these, although the results obtained from this study are consistent with the literature, more studies are needed examining the relationship between social media addiction and academic achievement. On the other hand, no mixed methodology with study has been found that addresses the mediating role of academic self-discipline in the relationship between social media addiction and academic success, and it is assumed that this study will make a significant contribution to the relevant literature. Additionally, this study encourages further examination of the protective role of the academic self-discipline variable in reducing social media addiction and increasing academic achievement.

Conclusion and suggestions

According to the results of this study, while social media addiction reduces academic achievement, academic self-discipline can prevent social media addiction from reducing academic achievement. Thus, it is recommended that academic self-discipline-based psychoeducation practices be implemented to reduce social media addiction among university students and increase their academic achievement. The obtained qualitative results allow us to understand the mediating role of academic self-discipline in this relationship in more detail. Given the themes, it is recommended that preventive guidance activities that can improve academic self-discipline, especially planned work, and attention, should be implemented more by both educators and school psychologists working in universities. Helping students create a structured study plan, providing regular guidance to help them implement this plan, teaching attention exercises and various memory exercises, and giving behavioral assignments to develop self-discipline are examples of these activities. When the themes explaining the reasons that lead students to use the internet are examined, the creation of other entertainment and recreation areas that can replace social media can contribute to distancing university students from social media. On the other hand, more quantitative and qualitative studies are needed in the literature to examine the relationship between social media addiction and academic achievement in terms of different variables.

Limitations

This study is limited to the quantitative and qualitative data obtained from students who continue to study as seniors in the 2023–2024 academic year at public universities in Turkey. Although there is no mixed methodology with studies examining the relationship between social media addiction and academic achievement variables with academic self-discipline, a very limited number of studies have examined the relationship with self-discipline. This study was supported by studies on self-control and self-regulation, which are used by some researchers instead of the concept of self-discipline. To prevent conceptual confusion and reveal the mediating role of academic self-discipline, such a path was followed, which some researchers may consider a limitation.

Data availability

The data generated and/or analyzed during the present study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. The data cannot be directly placed in a public repository due to limited permissions obtained from the participants. However, the corresponding author is willing to share anonymized data with interested researchers upon request.

Arquero JL, Romero-Frı́as E (2013) Using social network sites in higher education: An experience in business studies. Innov Educ Teach Int, 50(3):238–249. https://doi.org/10.1080/14703297.2012.760772

Article Google Scholar

Andreassen CS, Billieux J, Griffiths MD, Kuss DJ, Demetrovics Z, Mazzoni E, Pallesen S (2016) The relationship between addictive use of social media and video games and symptoms of psychiatric disorder: A large-scale cross-sectional study. Psychol Addictive Behav 30(2):252–262. https://doi.org/10.1037/adb0000160

Andreassen CS, Pallesen S (2014) Social network site addiction overview. Curr Pharm Des 20:4053–4061. https://doi.org/10.2174/13816128113199990616

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Bear, GG (2009). The positive in positive models of discipline. In R Gilman, ES Huebner, & MJ Furlong (Eds.), Handbook of positive psychology in schools (pp. 305-321). Taylor & Francis

Büyüköztürk, Ş, Çakmak, EK, Akgün, ÖE, Karadeniz, Ş, & Demirel, F (2014). Bilimsel araştırma yöntemleri . Pegem Academy

Cao LR, Cao XH (2004) The effects of time management tendencies, cognitive styles, and meta-concern levels on academic achievement of high school students. Chin J Ergonomics 10(3):13–15. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1006-8309.2004.03.005

Chen YF, Peng SS (2008) University students’ Internet use and its relationships with academic performance, interpersonal relationships, psychosocial adjustment, and self-evaluation. CyberPsychology Behav 11(4):467–469. https://doi.org/10.1089/cpb.2007.0128

Cohen R, Irwin L, Newton-John T, Slater A (2019) #bodypositivity: A content analysis of body-positive accounts on Instagram. Body Image 29:47–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2019.02.007

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Creswell, JW, & Plano Clark, VL (2018). Designing and conducting mixed methods research (3rd edition). Sage

Demirci İ (2019) The adaptation of the Bergen Social Media Addiction Scale to Turkish and its evaluation of the relationship with depression and anxiety symptoms. Anatol J Psychiatry 20:15–22. https://doi.org/10.5455/apd.41585

Diker E, Taşdelen B (2017) Sosyal medya olmasaydı ne olurdu? Sosyal medya bağımlısı gençlerin görüşlerine ilişkin nitel bir araştırma. Uluslar Hakemli İletişim ve Edeb Araştırmaları Derg 17:189–206. https://doi.org/10.17361/UHIVE.2017.4.17

Duckworth, AL, & Carlson, SM (2013). Self-regulation and school success. In BW Sokol, FME Grouzet, & U Müller (Eds.), Self-regulation and autonomy: Social and developmental dimensions of human conduct (pp. 208-230). Cambridge University Press

Duckworth AL, Seligman MEP (2006) Self-discipline gives girls the edge: Gender in self-discipline, grades, and achievement test scores. J Educ Psychol 98(1):198–208. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.98.1.198

Duckworth AL, Taxer JL, Eskreis-Winkler L, Galla BM, Gross JJ(2019) Self-control and academic achievement. 70(1)):373–399. Annual Review of Psychology 70(1):373–399. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-010418-103230

Ehrenberg A, Juckes S, White KM, Walsh SP (2008) Personality and self-esteem as predictors of young people’s technology use. CyberPsychology Behav 11:739–741. https://doi.org/10.1089/cpb.2008.0030

Erduran Tekin Ö, Şal F (2023) Akademik Öz Disiplin Ölçeği’nin Türkçeye Uyarlanması. Cumhur Uluslar Eğitim Derg 12(4):942–953. https://doi.org/10.30703/cije.1262071

Fang AR, Wang HP (2003) A comparative study of study time management between academically gifted students and academically disadvantaged students. Prim Second Sch Abroad 4:45–49. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1007-8495.2003.04.005

Gazibara T, Cakic J, Cakic M, Grgurevic A, Pekmezovic T (2020) Searching for online health information instead of seeing a physician: A cross-sectional study among high school students in Belgrade, Serbia. Int J Public Health 65:1269–1278. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00038-020-01471-7

George, D, & Mallery, P (2019). IBM SPSS statistics 25 step by step: A simple guide and reference (15th edition). Routledge

Gürbüz, S (2019). Sosyal bilimlerde aracı, düzenleyici ve durumsal etki analizleri . Seçkin Publishing

Hayes, AF (2017). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach . Guilford Press

Hrastinski S (2008) The potential of synchronous communication to enhance participation in online discussions: A case study of two e-learning courses. Inf Manag 45(7):499–506. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.im.2008.07.005

Jain N, Verma R, Tiwari P (2012) Going social: The impact of social networking in promoting education. Int J Computer Sci 9(1):483–485

Google Scholar

Junco R (2012) Too much face and not enough books: The relationship between multiple indices of Facebook use and academic performance. Computers Hum Behav 28(1):187–198. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2011.08.026

Kalaitzaki AE, Tamiolaki A, Rovithis M (2020) The health care professional amidst COVID-19 pandemic: A perspective of resilience and posttraumatic growth. Asian J Psychiatry 52:102172. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102172

Kaplan A, Özdemir C (2023) Hemşirelik öğrencilerinde sosyal medya bağimliliğinin iletişim becerisi ve akademik başari düzeylerine etkisi. önü Üniversitesi Sağlık Hizmetleri Mesl Yüksek Okulu Derg 11(1):1344–1357. https://doi.org/10.33715/inonusaglik.1155787

Kasperski R, Blau I (2020) Social capital in high schools: Teacher-student relationships within an online social network and their association with in-class interactions and learning. Interact Learn Environ 31(2):955–971. https://doi.org/10.1080/10494820.2020.1815220

Katz E, Gurevitch M, Haas H (1973) On the use of the mass media for important things. Am Sociological Rev 38(2):164–181. https://doi.org/10.2307/2094393

Kim EJ, Namkoong K, Ku T, Kim SJ (2007) The relationship between online game addiction and aggression, self-control, and narcissistic personality traits. Eur Psychiatry 23(3):212218. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eurpsy.2007.10.010

Koç H, Şimşir Gökalp Z, Seki T (2023) The relationships between self-control and distress among emerging adults: A serial mediating roles of fear of missing out and social media addiction. Emerg Adulthood 11(3):626–638. https://doi.org/10.1177/21676968231151776

Liang XL, He J, Liu PP (2020) The influence of cognitive ability on academic achievement of junior middle school students: a mediated moderation model. Psychological Dev Educ 36(4):449–461. https://doi.org/10.16187/j.cnki.issn1001-4918.2020.04.08

Li X, Li D, Newman J (2013) Parental behavioral and psychological control and problematic internet use among Chinese adolescents: The mediating role of self-control. Cyberpsychology, Behav, Soc Netw 16(6):1–6. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2012.0293

Li D, Zhang W, Li X, Zhen S, Wang Y (2010) Stressful life events and problematic Internet use by adolescent females and males: a mediated moderation model. Comput Hum Behav 26(5):1199–1207. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2010.03.031

Lin HP (2021) Comprehensively promote the reform of the college entrance examination content to help build a high-quality education system. J China Exam 1:1–7. https://doi.org/10.19360/j.cnki.11-3303/g4.2021.01.001

Article CAS Google Scholar

Lindner C, Nagy G, Arhuis WAR, Retelsdorf J (2017) A new perspective on the interplay between self-control and cognitive performance: Modeling progressive depletion patterns. Plos One 12(6):e0180149. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0180149

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Mbaluka, SN (2017). The impact of student self-discipline and parental involvement in students’ academic activities on student academic performance [Doctoral Dissertation, Andrews University]. https://doi.org/10.32597/dissertations/1654

Malte S, Ricarda S, Birgit S (2009) How do motivational regulation strategies affect achievement: mediated by effort management and moderated by intelligence. Learn Individ Differences 19(4):621–627. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2009.08.006

Masood A, Luqman A, Feng Y, Ali A (2020) Adverse consequences of excessive social networking site use on academic performance: Explaining underlying mechanism from stress perspective. Comput Hum Behav 113:106476. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2020.106476

Miles, MB, & Huberman, AM (1994). Qualitative data analysis: An expanded sourcebook (2nd edition). Sage

Ning, W, & Inan, FA (2023). Impact of social media addiction on college student’s academic performance: an interdisciplinary perspective. Journal of Research on Technology in Education , 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/15391523.2023.2196456

O’Keeffe GS, Clarke-Pearson K, Council on Communications and Media (2011) The impact of social media on children, adolescents, and families. Pediatrics 127(4):800–804. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2011-0054

Özdemir Z (2019) Social media addiction among university students. Beykoz J Acad 7(2):91–105. https://doi.org/10.14514/byk.m.26515393.2019.7/2.91-105

Article MathSciNet Google Scholar

Pustika R (2020) Future English teachers’ perspective towards the implementation of e-learning in the COVID-19 pandemic era. J Engl Lang Teach Linguist 5(3):383–391. https://doi.org/10.21462/jeltl.v5i3.448

Putri FI, Nila S, Widayati KA (2022) Correlation between social networking time use and self-control of university students in Indonesia. Kasetsart J Soc Sci 43:949–956. https://doi.org/10.34044/j.kjss.2022.43.4.18

Sağar, ME (2021). Predictive role of cognitive flexibility and self-control on social media addiction in university students. International Education Studies , 14 (4), https://doi.org/10.5539/ies.v14n4p1

Schumacker, R, & Tomek, S (2013). Understanding statistics using R . Springer

Shi Y, Qu S (2022) The effect of cognitive ability on academic achievement: The mediating role of self-discipline and the moderating role of planning. Front Psychol 13:1014655. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1014655

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Shi C, Yu L, Wang N, Cheng B, Cao X (2020) Effects of social media overload on academic performance: A stressor-strain-outcome perspective. Asian J Commun 30(2):1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/01292986.2020.1748073

Şal F (2022) Development of an Academic Self-discipline Questionnaire for university students. Pedagogical Perspect 1(2):76–88. https://doi.org/10.29329/pedper.2022.493.1

Taylor AF, Kuo FE, Sullivan WC (2002) Views of nature and self-discipline: Evidence from inner-city children. J Environ Psychol 22(1-2):49–63. https://doi.org/10.1006/jevp.2001.0241

Thomas TA, Maree D (2021) Student factors affecting academic success among undergraduate students at two South African higher education institutions. South Afr J Psychol 52(1):99–111. https://doi.org/10.1177/0081246320986287

Tominey SL, McClelland MM (2011) Red light, purple light: Findings from a randomized trial using circle time games to improve behavioral self-regulation in preschool. Early Educ Dev 22(3):489–519. https://doi.org/10.1080/10409289.2011.574258

Tutgun-Ünal A, Deniz L (2015) Development of the Social Media Addiction Scale. Online Academic J Inf Technol 6(21):51–70. https://doi.org/10.5824/1309-1581.2015.4.004.x

Van Endert TS (2021) Addictive use of digital devices in young children: Associations with delay discounting, self-control and academic performance. PloS One 16(6):e0253058. 10.1371/journal.pone.0253058

Wartberg L, Kriston L, Thomasius R (2020) Internet gaming disorder and problematic social media use in a representative sample of German adolescents: Prevalence estimates, comorbid depressive symptoms, and related psychosocial aspects. Comput Hum Behav 103:31–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2019.09.014

Whelan E, Islam AN, Brooks S (2020) Applying the SOBC paradigm to explain how social media overload affects academic performance. Comput Educ 143:103692. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2019.103692

Wu J-Y, Cheng T (2019) Who is better adapted in learning online within the personal learning environment? Relating gender differences in cognitive attention networks to digital distraction. Comput Educ 128:312–329. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2018.08.016

Wu AMS, Cheung VI, Ku L, Hung EPW (2013) Psychological risk factors of addiction to social networking sites among Chinese smartphone users. J Behav Addictions 2(3):160–166. https://doi.org/10.1556/jba.2.2013.006

Yıldırım, A, & Şimşek, H (2019). Sosyal bilimlerde nitel araştırma yöntemleri (11th edition). Seçkin Publishing

Young KS (1996) Psychology of computer use: XL. Addictive use of the internet: A case that breaks the stereotype. Psychol Rep. 79(3):899–902. https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.1996.79.3.899

Zachos G, Paraskevopoulou-Kollia EA, Anagnostopoulos I (2018) Social media use in higher education: A review. Educ Sci 8(4):194. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci8040194

Zahrai K, Veer E, Ballantine PW, Peter de Vries H (2022) Conceptualizing self-control on problematic social media use. Australas Mark J 30(1):74–89. https://doi.org/10.1177/1839334921998866

Zhao L (2023) Social media addiction and its impact on college students’ academic performance: The mediating role of stress. Asia-Pac Educ Res 32:81–90. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40299-021-00635-0

Zhao R, Kuo YL (2015) The role of self-discipline in predicting achievement for 10th graders. Int J Intell Technol Appl Stat 8(1):61–70. https://doi.org/10.6148/IJITAS.2015.0801.05

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

National Defense University/ Air Force Academy/ Department of Humanities and Social Sciences, İstanbul, Turkey

Özge Erduran Tekin

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

Özge Erduran Tekin collected data, undertook formal analysis, wrote and revised the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Özge Erduran Tekin .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The author declares no competing interests.

Ethical approval

Ethics committee approval dated 23.01.2024 and numbered E-35592990-050.01.04-3222142 was obtained from this study’s National Defense University Scientific Research and Publication Ethics Committee. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were by the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from the participants before filling in the scales of the study. In this consent, the purpose of the study, the confidentiality of the data, and the method of destruction were mentioned, and if they were willing to participate in the study, they were asked to start filling in the scales by approving this consent form. All participants approved the consent form and voluntarily completed the scales. Then, interviews were conducted with the participants who were also volunteers, completed the consent form, and fulfilled the selection criteria.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Erduran Tekin, Ö. Academic self-discipline as a mediating variable in the relationship between social media addiction and academic achievement: mixed methodology. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 11 , 1096 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03633-x

Download citation

Received : 18 March 2024

Accepted : 20 August 2024

Published : 28 August 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03633-x

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Epidemiologia (Basel)

- PMC11348197

Video Game Addiction in Young People (8–18 Years Old) after the COVID-19 Pandemic: The Grey Area of Addiction and the Phenomenon of “Gaming Non-Pathological Abuse (GNPA)”

Domenico piccininno.

1 Department of Forensic Criminology, Forensic Science Academy (FSA), 84083 Castel San Giorgio, Italy; moc.liamg@572onniniccipocinemod

Giulio Perrotta

2 Istituto per lo Studio delle Psicoterapie (ISP), 00185 Rome, Italy

Associated Data

The data were received and stored by Giovanni Della Porta.

Introduction: In the literature, video game addiction in youths is correlated with dysfunctional symptoms of anxiety, emotional disorders, and mood disorders, and the pandemic period of 2020–2022 has favored the aggravation of this behavioral addiction. Therefore, we identified the need to analyze this phenomenon with an emphasis on the risks and correlates related to deviance and maladjustment from a prospective perspective, seeking to understand the impact of the individual variables examined. Aim: To demonstrate whether the condition of “gaming non-pathological abuse” (GNPA) promotes psychopathological features of clinical interest, in the absence of a diagnosis of “gaming disorder” (GD). Materials and methods: A search performed on PubMed and administration of an ad hoc sociological questionnaire were used to investigate individual variables of criminological interest in a representative population sample (531 males/females, 8–18 years old, M: 14.4, SD: 2.5). Results: Statistical analysis showed that after the pandemic period, digital video game addiction was reinforced, feeding psychopathological traits consistent with anxiety, emotional disorders, and mood disorders. Variables correlated with impulsive, aggressive, and violent behavior related to age, gender, socio-environmental and economic background, and the severity of digital video game addiction. Conclusions: In the youth population (8–18 years), “gaming non-pathological abuse” (GNPA) is related to aggressive, impulsive and violent behaviors that foster phenomena of social maladjustment and deviance, especially in individuals living in disadvantaged or otherwise complex socio-economic and family contexts. Looking forward, the study of structural and functional personality profiles is essential in order to anticipate and reduce the future risk of psychopathological and criminal behavior.

1. Introduction

Video game use has constantly increased among children and adolescents, having uncertain consequences for their health [ 1 ]. Video game addiction or gaming disorder (GD) is defined as the constant and repetitive use of the Internet to play frequently with different players, potentially leading to negative consequences in many aspects of life. In clinical settings, addiction to video game use for recreational purposes is considered a psychopathology only if the behavioral pattern of persistent and recurrent video game use leads to significant impairment of daily functioning or psychological distress. It is diagnosed according to the Diagnostic Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM5-TR) criteria, Section 3 , wherein over a period of 12 months at least, five criteria are enough confirm GD, with concerns resulting from gaming (cognitive salience), withdrawal symptoms when gaming is not possible, tolerance (need to increase gaming time), failure in attempts to control/reduce use, loss of interest in other hobbies or activities (behavioral salience), overuse despite acknowledging the existence of a problem, lies about time spent playing, video games use to sedate/regulate/reduce an unpleasant emotional experience, loss or impairment of relevant interpersonal relationships, and impairment of school or work performance [ 2 , 3 ]. As recent technological development has allowed easy access to gaming on many devices, video game addiction has become a serious public health problem with increasing prevalence [ 4 ]. The non-pathological abuse of video games for recreational activity (“gaming non-pathological abuse”, or GNPA), which does not meet the diagnostic criteria of the DSM-5-TR, is not yet considered in the scientific literature, although it may be a potential cause of psychological distress for the subject [ 5 , 6 , 7 ].

With the advent of the global COVID-19 pandemic, social isolation and fear of viral contagion resulted in profound changes in social relationships among people [ 8 ], generating or fueling the psychopathological symptoms of anxiety, emotional distress, low mood [ 9 , 10 , 11 ], and psychosis [ 12 ] in those affected by internet gaming disorder and video game addiction. It also fostered deviant and criminal conduct, such as cyberbullying [ 13 ] and other behavioral addictions [ 2 , 6 , 7 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 ] that promote isolation, aggression, and deviant and criminal behavior and suicide risk [ 6 , 7 , 20 , 21 , 22 ] and also influence cognitive and behavioral performance [ 23 ]; thus, all of the above are clinically relevant conditions worthy of psychotherapeutic [ 24 ] and pharmacological evaluation and treatment [ 25 , 26 ].

Recent systematic review and meta-analysis studies have shown and confirmed that the prolonged effects of the recreational use of video games determine an increase in anxiety (phobias, fixations, panic and sleep disorders), emotional (aggression and impulsivity) and mood (manic and depressive) symptoms, and risk of suicidal ideations [ 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 ]. Additionally, from a neurobiological point of view, recent studies have shown that the reckless use of certain types of games, violent ones in particular, can impact brain circuits by leading to their structural and functional modification of the cognitive performance of attentional, control–rational, and visuospatial skills and reward processing [ 31 , 32 ]. However, contrary studies also emerge from the literature, praising the cognitive, motivational, emotional, and social benefits of the playful activity of using video games [ 33 , 34 , 35 ] in terms of the cognitive behavioral approach to therapy [ 36 ] and cognitive and psychopathological assessment [ 37 , 38 , 39 , 40 ], thus leading to confusion between the outcomes of published research.

The purpose of the present study is to analyze the impact of the post-COVID-19-pandemic period on the youth population (8–18 years old) who use video games for recreational purposes, in the absence of a psychopathological diagnosis of “Gaming Disorder” (GD) but with an attenuated condition that the literature does not take into consideration (i.e., “gaming non-pathological abuse”, or GNPA) and then correlate the data obtained from the administration of a questionnaire survey to assess the severity of dependency using the variables of age gender; socio-environmental and economic background; and impulsive, aggressive, and violent behaviors, if present. In the absence of a GD diagnosis according to DSM-5-TR criteria, the aim was to demonstrate that such a condition is still worthy of socio-clinical intervention because it can generate potential psychological distress.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. materials and methods.

From January 1991 to June 2024, we actively searched PubMed for systematic reviews, meta-analyses, clinical trials, and randomized controlled trials using “Addiction AND Video games”, selecting 257 eligible results, 35 of which were included by removing duplicate content, irrelevant items, and absence of search items. To get a broader and more complete overview of the topic, 6 more references were added (from elsewhere and not the Pubmed platform, being materials from the academic literature), for a total of 41 results. Simple reviews, opinion contributions, or publications in popular volumes were excluded as redundant or not relevant to this work. An artificial intelligence program was not used for the automatic selection of results, but the tools and services offered by the PubMed platform were used. The search was not limited to English and Italian language papers ( Figure 1 ).

PRISMA flow diagram template. Adapted from Page M.J. et al. [ 41 ].

The use of the literature was necessary to construct the introduction section of this study and to understand the usefulness of delving into the topic of “gaming non-pathological abuse” (GNPA), which is still not discussed in the literature because it is not considered clinically relevant.

Having identified the criteria for selecting the population, various meetings in educational institutions were arranged to raise awareness among students and ask for their participation, subject to prior signing of informed consent and data processing, signed by parents or by students over 18. Having indicated the link to fill out the specially prepared Sociological Questionnaire (with 50 items, analyzing the variables listed in Table 1 , with single yes/no, multiple, or open-ended responses), the students (independently or helped by a familiar adult) logged on to complete it. The present research work was carried out from January 2023 to June 2024. All participants were guaranteed anonymity and the ethical requirements of the Declaration of Helsinki were met. Since this research was not funded by anyone, it is free of conflicts of interest.

List of selected variables, specifying type and description.

| N | Variable | Type_Variable | Type_Answer | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Age | Generic | Continued: 8–18 years old | Variable related to age |

| 2 | Gender | Generic | Dichotomous_Yes/No | Variable related to gender |

| 3 | Cluster | Generic | Dichotomous_Yes/No | Variable related to membership in the clinical group (daily recreational use of video games, more than 60 min) or control group (daily recreational use of video games, less than or equal to 60 min), including non-continuous |