An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- HHS Author Manuscripts

Driving Under the Influence of Alcohol: Findings from the NSDUH, 2002-2017

1 College of Social Work, The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH 43210, United States.

Michael G. Vaughn

2 School of Social Work, College for Public Health and Social Justice, Saint Louis University, St. Louis, MO 63103, United States.

3 Graduate School of Social Welfare, Yonsei University, Seoul, Republic of Korea.

Christopher P. Salas-Wright

4 School of Social Work, Boston University, Boston, MA 02215, United States.

Millan A. AbiNader

5 School of Social Work, Arizona State University, Phoenix, AZ 85006, United States.

Mariana Sanchez

6 Robert Stempel College of Public Health and Social Work, Florida International University, Miami, FL 33199, United States.

Author Statement

Michael G. Vaughn: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing - review & editing

Christopher P. Salas-Wright: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing - review & editing

Millan A. AbiNader: Investigation; Writing - review & editing

Mariana Sanchez : Validation; Writing - review & editing

Based on a nationally representative adult sample, the present study examined the prevalence and trends of driving under the influence (DUI) of alcohol in the United States from 2002 to 2017.

Using data from the 2002–2017 National Survey on Drug Use and Health, the prevalence of DUI of alcohol in 2012–2017 were estimated to test for changes in trend and to identify populations at elevated risks of alcohol-involved driving.

Since 2002, the prevalence of DUI of alcohol has gradually decreased from a high of 15.1% in 2002–2004 to 11.8% in 2012–2014 and 8.5% in 2016–2017, indicating percent decreases by 21.6% and 43.7%, respectively. While decreasing trends were observed across all major sociodemographic and criminal justice subgroups (except older adults), men, young adults, Whites, and those with higher household income continued to be associated with greater risks of alcohol-involved driving. Nevertheless, DUI arrests continued to increase among women, narrowing the gender gap.

Discussion:

Despite the decreased alcohol-involved driving over the past decade, there remains worrisome levels among young adult males. This underscores the need for alcohol policies and public awareness campaigns targeting young adult males. Moreover, further research is needed to elucidate the potential differences in the populations who reported driving under any influence of alcohol and who were involved in fatal crashes.

1. Introduction

Driving under the influence (DUI) of alcohol is a significant public health problem. Over 30% of motor vehicle traffic fatalities were caused by alcohol-impaired driving, resulting in 10,874 lives lost and $44 billion costs incurred in 2017 alone ( Naimi et al., 2018 ; National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, 2018 ). Additionally, nearly 1 million arrests were made for DUI during the same year ( The Federal Bureau of Investigation, n.d. ). Several key policies have been implemented to reduce DUI of Alcohol. For instance, by 2004, all states enacted new legal limits of alcohol-impaired driving at a blood alcohol concentration [BAC] of 0.08g/dL. By 2011, 42 states adopted so-called the “Administrative License Revocation” law, which enables states to suspend or revoke driver licenses when a driver was found driving with a BAC of 0.08% or above ( Ying et al., 2013 ).

Despite recent policy changes at the federal and state levels, evidence is limited about how many Americans are involved in drinking and driving and how these rates have changed. NHTSA releases data on drivers’ alcohol involvement, but this data only captures those involved in fatal traffic crashes. Some studies ( Quinlan et al., 2005 ; Schwartz & Beltz, 2018 ) report population-based estimates based on national surveys such as the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS), but these studies also have limitations. For instance, the BRFSS asks whether respondents drove when they have had “perhaps too much” drink during the past month ( Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2018a ). Due to the possibility of subjective interpretation of the question, consistent estimation and comparison of the DUI of alcohol prevalence may not be warranted across respondents and years.

To inform prevention efforts while triangulating existing evidence, further evaluation of trends in the prevalence of DUI of alcohol and identification of populations at heightened risk is critical. Especially, evidence on the scope of the population who drive under any degree of alcohol influence is important to provide insights on more general alcohol-involved driving behaviors and to enable early detection and intervention of problematic driving activities. Moreover, large variations in DUI of alcohol patterns and risks across population subgroups (e.g., age, sex, race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status [SES], criminal justice history) require investigations into identifying those at greatest risk ( Calling et al., 2019 ; Casswell et al., 2003 ; Dickson et al., 2013 ; Impinen et al., 2011 ; Schwartz & Beltz, 2018 ). For instance, Schwartz and Beltz (2018) showed that men’s alcohol-impaired driving rates continue to remain higher than women’ despite an overall decreasing trend. Yet, DUI arrests have increased among women since 1985, narrowing the gender gap ( Schwartz & Beltz, 2018 ; Schwartz & Rookey, 2008 ). In a study examining major racial/ethnic groups, Whites were more likely to be involved in alcohol-impaired driving than African-Americans and Hispanics–though people of color were overrepresented in arrests and crashes ( Romano et al., 2010 ). Studies also point to the different drinking and driving behaviors by prior DUI and other criminal arrests. Labrie and colleagues (2007) found that a history of anti-social behavior and criminal justice system encounters were as important as prior alcohol-related problems in predicting a higher recidivism rate.

The present study addresses prior gaps by examining the prevalence and trends of DUI of alcohol in the United States since 2002 using data from National Survey of Drug Use and Health (NSDUH). We present population-based prevalence estimates for past-year DUI of alcohol among all respondents aged 18 or older and various subgroups by sociodemographic characteristics and criminal justice involvement. Then we tested for changes in trend in DUI of alcohol by comparing with the rates from 2002 to 2017.

2. Material and Methods

2.1. data and sample.

The NSDUH provides nationally representative cross-sectional estimates of substance use and behavioral health outcomes among non-institutionalized civilians aged 12 and older in the United States. In each year, multistage area probability sampling strategy was used to recruit participants, who were interviewed privately at their residence. To reduce socially desirable responding of sensitive behaviors, the interview was carried out using computer-assisted interviewing methodology as a confidential means of reporting. From the 2002–2017 NSDUH data, the present study included an analytic sample of 615,882 adults aged 18 or above (286,562 men and 329,320 women). More detailed descriptions of the NSDUH are available elsewhere ( Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, 2018 ).

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. dui of alcohol..

All participants were asked: “During the past 12 months, have you driven a vehicle while you were under the influence of alcohol?” Those who reported yes were classified as having involved in DUI of alcohol and were coded as 1, and coded 0 otherwise. While this measure is fully comparable across years from 2002 to 2014, changes in the respondents eligible for DUI questions in 2015 and changes to the drug-related questions in 2016 require caution in comparing estimates between pre-2014 and post-2014 ( Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, 2016 , 2017 ).

2.2.2. Sociodemographic factors and criminal justice involvement.

In addition to key sociodemographic characteristics including age, sex, race/ethnicity, household income, and urbanicity of residence, three indicators (0=no, 1=yes) of criminal justice system involvement in the past 12 months were also examined. These included: any arrests and booking, not counting minor traffic violations, arrests/booking for DUI, and probation/parole status.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

Using the fully comparable data, we first assessed the prevalence of DUI of alcohol in the early 2000s (2002–2004) and 2010s (2012–2014) for the total sample and sociodemographic and criminal justice involvement subgroups. Samples of three adjacent years were combined to obtain a more stable and consistent estimation. Additionally, the prevalence in years 2016–2017 was examined to provide the most recent rates of DUI of alcohol. Second, annual trends of DUI of alcohol among the whole sample and the trends of DUI arrests and booking among those reporting past-year DUI of alcohol were examined while stratifying by key demographic factors. Third, we tested the significance of the DUI of alcohol trends by including year as a continuous independent variable in multiple logistic regression models (while controlling for the sociodemographic factors) as the CDC (2016) suggests. All estimates were weighted to account for the NSDUH’s stratified cluster sampling design ( Substance Abuse and Mental Health Data Archive, 2014 ). While supplementary analyses including the 2015–2017 data follow similar steps above, adjusted weights were created to account for three additional years of data in consistent with the CDC (2018b) ’s technical guideline.

3.1. Trends in DUI of Alcohol among U.S. Adults

Table 1 displays the prevalence and trends of DUI of alcohol from the early 2000s to 2010s among the full sample and subgroups by demographic characteristics and criminal justice involvement. The prevalence in DUI of alcohol decreased from 15.1% in 2002–2004 to 11.8% in 2012–2014, indicating a 21.6% reduction. This decreasing trends were supported by test of trends for 2002–2014 (AOR = 0.967, 95% CI = 0.963–0.971) and 2002–2017 (AOR = 0.956, 95% CI = 0.953–0.958) as shown in Table A.1 .

Past Year Prevalence of Self-Reported Driving Under the Influence of Alcohol among Adults in the United States, NSDUH 2002–2017

Note: Estimates adjusted for survey design effects. According to SAMHDA, data from 2015–2017 are not fully comparable due to changes in survey design; therefore, we conduct separate supplemental tests. Δ pp = percentage point change from 2002–2004. % change determined by dividing the pp change by the 2002–2004 value.

All major sociodemographic and criminal justice subgroups except older adults aged 65+ showed decline in 2012–2014 and then again in 2016–2017 (see Table 1 ). In 2012–2014, 15.6% (11.1% in 2016–2017) of men and 8.4% (6.1% in 2016–2017) of women reported DUI of alcohol, indicating reductions by 23.2% and 18.9% from 2002–2004, respectively. Declines were gradual and consistent over the study period as shown in the upper chart of Figure 1 . Test of trends supported significant decreases over the past decade for both men (AOR = 0.966, 95% CI = 0.961–0.971) and women (AOR = 0.968, 95% CI = 0.963–0.974).

Prevalence of Driving Under the Influence (DUI) of Alcohol and DUI Arrests among Respondents Who Reported Past-year DUI of Alcohol by Sex in the United States, NSDUH 2002–2017.

Notes. Y-axis displays the survey adjusted prevalence for the corresponding outcome. According to Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services’ Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality (2018) , data for self-reported DUI of alcohol from 2015–2017 are not fully comparable to data prior to 2015 due to changes in survey design.

Additionally, several findings from subgroup analyses are worth noting. First, respondents aged 26–35, due to their slower declining rate than those aged 18–25 (during 2002–2014, AOR = 0.967 for ages 26–34 and AOR = 0.941 for ages 18–25), matched the rates of DUI of alcohol of the youngest age group in 2012–2014. In 2016–2017, 12.1% of respondents aged 26–34 drove under the influence of alcohol, significantly higher than the rates among those aged 18–25 (10.7%). Second, Whites continued to be the racial/ethnic group with the highest prevalence of DUI of alcohol with more than one in every ten adults involved in drunk driving. Third, those with higher SES (i.e., household income of $75,000+ and college education or above) reported the highest prevalence in drunk driving and showed the smallest percent decline over the last decade compared to lower SES groups. Lastly, respondents who encountered the criminal justice system in the past year had greater likelihoods of DUI of alcohol. However, the magnitudes of the decrease in DUI of alcohol prevalence over time were similar to those who were not arrested or booked.

3.2. Trends of DUI Arrests/Booking among Those Engaged in DUI of Alcohol

The lower chart in Figure 1 displays the prevalence of DUI arrests and booking among those reporting DUI of alcohol in the past year. Overall, higher percentages of men reporting DUI of alcohol were more likely to be arrested and booked, ranging between 2.6% and 4.9%, with no significant time trends since 2002 (AOR = 0.999; 95% CI = 0.980–1.018 for 2002–2014). Additionally, significant and gradual increases in women’s DUI arrests and booking were observed from 1.2% in 2002 to 2.3% in 2014 (AOR = 1.055; 95% CI = 1.070–1.082) and 2.5% in 2017 (AOR = 1.040, 95% CI = 1.021–1.059).

4. Discussion

Although we identified decreasing trends in DUI of alcohol (except among older adults), we also found that nearly one in every ten adults in the United States drove under the influence of alcohol. Respondents who were aged 26–34, male, and White, and who reported higher SES as well as those with past-year criminal justice system encounters were more likely to engage in alcohol-involved driving in consistent with prior literature such as Caetano and McGrath (2005) and Labrie et al. (2007) . While greater reductions in the prevalence of DUI of alcohol among those under 26 years old is encouraging, preventive efforts targeting those in their late 20s and early 30s as well as other at-risk sociodemographic subgroups are needed. Moreover, special attention is needed with respect to observed gains in the number of women arrested. Increased alcohol use among women in adolescence and young adulthood as well as a lower legal limit of alcohol-impaired driving are considered important factors underlying the gendered DUI arrest trends ( Robertson et al., 2011 ; Schwartz, 2008 ). Thus, further investigation elucidating who were more affected by the recent alcohol use trends and driving behaviors among women involved in DUI of alcohol is warranted.

Importantly, national reports reveal that the number of alcohol-impaired drivers involved in fatal crashes have started to rise since 2011 in contrast to overall decreases in DUI of alcohol throughout the past decade (see Figure A.1 ). This implies that though fewer Americans drive under any influence of alcohol, the number of alcohol-impaired drivers who are involved in fatal crashes has not subsided since the early 2010s. Thus, it is important to implement measures focused on recalcitrant heavy drinkers who drive that may also have co-existent substance use problems ( Hingson et al., 2008 ). Unfortunately, this may be especially common among young adults who constitutes the largest age group involved in fatal drunk-driving crashes ( National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, 2018 ).

The present study has several limitations. First, data on DUI of alcohol and criminal justice involvement were derived from respondents’ self-reports. Social desirability bias and subjective assessment of intoxication may have affected responses’ accuracy. However, NSDUH’s adoption of the computer-assisted self-interviewing method is considered effective in encouraging honest disclosures. Second, DUI of drugs, an increasingly important part of the DUI problem ( Nochajski & Stasiewicz, 2006 ), was not examined in the study due to multiple changes in the NSDUH’s study designs specific to these questions. Third, DUI trends by different degrees of alcohol influence could not be examined due to lack of BAC information. Data on BAC are needed to better understand the slower reductions in traffic fatalities involving alcohol-impaired drivers than the rates of reductions in DUI of alcohol. Lastly, lack of contextual information limited further investigations into the underlying mechanisms of a higher DUI risk such as higher SES and neighborhood characteristics (e.g., ethnic densities, policing practices). Future research is needed to elucidate the role of salient individual (e.g., affordability, drinking behaviors) and neighborhood factors.

Despite the aforementioned limitations, the present study provides an important triangulation source for existing evidence which largely focuses on driving with BACs of 0.08g/dL or above. While we observed decreasing trends in DUI of alcohol influence among a nationally-representative U.S. adult sample, we also identified target groups for prevention efforts. Specifically, the present investigation points to further division between Americans who drive following heavy drinking episodes and the aggregates who refrain from drinking and driving at all. Alcohol policies and public awareness campaigns need to target young adult males (mostly White) concomitantly with additional research that sheds light on the potential differences in the populations who were involved in fatal crashes and who reported driving under any influence of alcohol.

- About one in ten Americans are driving under the influence of alcohol(DUI-Alcohol).

- Contrary to overall decreases, DUI-Alcohol remained unchanged among older adults.

- The prevalence among those aged 26–34 exceeded the rates among those 25 or under.

- Male, White, and higher income continue to be associated with a greater prevalence.

- DUI arrests increased among Women, narrowing the gender gap.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism of the National Institutes of Health [Award Number K01AA026645]. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of NIAAA or the NIH.

Test of Significance for Trends in Past Year Driving Under the Influence of Alcohol among Adults (Aged 18+) in the United States, NSDUH 2002–2017

Notes. The models were adjusted for sociodemographic factors including sex, age, race/ethnicity, employment status, marital status, educational attainment, annual household income, and urbanicity of residence. Odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals in bold are statistically significant at .05. Caution in interpretation of the supplemental tests is needed due to potential incomparability of DUI data between pre- and post-Year 2015.

Figure A.1.

Prevalence of Driving Under the Influence (DUI) of Alcohol and Number of Alcohol-Impaired Drivers Involved in Fatal Traffic Crashes, 2004–2017

Notes. Data on driving under the influence (DUI) of alcohol and alcohol-impaired drivers were derived from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health and National Highway Traffic Safety Administration’s Fatality Analysis Reporting System, respectively. According to Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services’ Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality (2018) , data for self-reported DUI of alcohol from 2015–2017 are not fully comparable to data prior to 2015 due to changes in survey design.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest

- Caetano R, & McGrath C (2005). Driving under the influence (DUI) among U.S. ethnic groups . Accident Analysis & Prevention , 37 ( 2 ), 217–224. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Calling S, Ohlsson H, Sundquist J, Sundquist K, & Kendler KS (2019). Socioeconomic status and alcohol use disorders across the lifespan: A co-relative control study . PloS one , 14 ( 10 ), e0224127. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Casswell S, Pledger M, & Hooper R (2003). Socioeconomic status and drinking patterns in young adults . Addiction , 98 ( 5 ), 601–610. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. (2016). 2015 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Methodological summary and definitions . Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; Retrieved from https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUH-MethodSummDefsHTML-2015/NSDUH-MethodSummDefsHTML-2015/NSDUH-MethodSummDefs-2015.htm . [ Google Scholar ]

- Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. (2017). 2016 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Methodological summary and definitions . Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; Retrieved from https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUH-MethodSummDefs-2016/NSDUH-MethodSummDefs-2016.htm . [ Google Scholar ]

- Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. (2018). 2017 National Survey on Drug Use and Health final analytic file codebook . Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; Retrieved from http://samhda.s3-us-gov-west-1.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/field-uploads-protected/studies/NSDUH-2017/NSDUH-2017-datasets/NSDUH-2017-DS0001/NSDUH-2017-DS0001-info/NSDUH-2017-DS0001-info-codebook.pdf . [ Google Scholar ]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2018a). 2018 BRFSS questionnaire . Atlanta, GA: United States Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/brfss/questionnaires/pdfques/2018_BRFSS_English_Questionnaire.pdf . [ Google Scholar ]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2018b). NSDUH: Technical guidance for analysts . Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/rdc/b1datatype/datafiles/Guidelines-for-Using-NSDUH-Restricted-use-Data.pdf .

- Dickson MF, Wasarhaley NE, & Webster JM (2013). A comparison of first-time and repeat rural DUI offenders . Journal of Offender Rehabilitation , 52 ( 6 ), 421–437. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hingson RW, Heeren T, & Edwards EM (2008). Age at drinking onset, alcohol dependence, and their relation to drug use and dependence, driving under the influence of drugs, and motor-vehicle crash involvement because of drugs . Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs , 69 ( 2 ), 192–201. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Impinen A, Makela P, Karjalainen K, Haukka J, Lintonen T, Lillsunde P, … Ostamo A (2011). The association between social determinants and drunken driving: A 15-year register-based study of 81,125 suspects . Alcohol and Alcoholism , 46 ( 6 ), 721–728. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Labrie RA, Kidman RC, Albanese M, Peller AJ, & Shaffer HJ (2007). Criminality and continued DUI offense: criminal typologies and recidivism among repeat offenders . Behavioral Sciences & the Law , 25 ( 4 ), 603–614. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Naimi TS, Xuan Z, Sarda V, Hadland SE, Lira MC, Swahn MH, … Heeren TC (2018). Association of state alcohol policies with alcohol-related motor vehicle crash fatalities among US adults . JAMA internal medicine , 178 ( 7 ), 894–901. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- National Center for HIV/AIDS, V. H., STD, and TB Prevention. (2016). Conducting trend analyses of YRBS data . Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [ Google Scholar ]

- National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. (2018). Traffic safety facts 2017 data: Alcohol-impaired driving . Washington, DC: National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. [ Google Scholar ]

- Nochajski TH, & Stasiewicz PR (2006). Relapse to driving under the influence (DUI): A review . Clinical Psychology Review , 26 ( 2 ), 179–195. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Quinlan KP, Brewer RD, Siegel P, Sleet DA, Mokdad AH, Shults RA, & Flowers N (2005). Alcohol-impaired driving among U.S. adults, 1993–2002 . American Journal of Preventive Medicine , 28 ( 4 ), 346–350. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Robertson AA, Liew H, & Gardner S (2011). An evaluation of the narrowing gender gap in DUI arrests . Accident Analysis & Prevention , 43 ( 4 ), 1414–1420. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Romano E, Voas RB, & Lacey JH (2010). Alcohol and highway safety: Special report on race/ethnicity and impaired driving : National Highway Traffic Safety Administration; Washington, DC. [ Google Scholar ]

- Schwartz J (2008). Gender differences in drunk driving prevalence rates and trends: A 20-year assessment using multiple sources of evidence . Addictive Behaviors , 33 ( 9 ), 1217–1222. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Schwartz J, & Beltz L (2018). Trends in female and male drunken driving prevalence over thirty years: Triangulating diverse sources of evidence (1985–2015) . Addictive Behaviors , 84 , 7–12. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Schwartz J, & Rookey BD (2008). The narrowing gender gap in arrests: Assessing competing explanations using self-report, traffic fatality, and official data on drunk driving, 1980–2004 . Criminology , 46 ( 3 ), 637–671. [ Google Scholar ]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Data Archive. (2014). How do I account for complex sampling design when analyzing NSDUH data? Retrieved from http://samhdafaqs.blogspot.com/2014/03/how-do-i-account-complex-sampling.html

- The Federal Bureau of Investigation. (n.d.). 2017. crime in the United States . Washington, DC: The Federal Bureau of Investigation; Retrieved from https://ucr.fbi.gov/crime-in-the-u.s/2017/crime-in-the-u.s.−2017/topic-pages/tables/table-29 . [ Google Scholar ]

- Ying Y-H, Wu C-C, & Chang K (2013). The effectiveness of drinking and driving policies for different alcohol-related fatalities: A quantile regression analysis . International journal of environmental research and public health , 10 ( 10 ), 4628–4644. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Open access

- Published: 12 March 2015

Driving under the influence of alcohol: frequency, reasons, perceived risk and punishment

- Francisco Alonso 1 ,

- Juan C Pastor 1 ,

- Luis Montoro 2 &

- Cristina Esteban 1

Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, and Policy volume 10 , Article number: 11 ( 2015 ) Cite this article

71k Accesses

41 Citations

8 Altmetric

Metrics details

The aim of this study was to gain information useful to improve traffic safety, concerning the following aspects for DUI (Driving Under the Influence): frequency, reasons, perceived risk, drivers' knowledge of the related penalties, perceived likelihood of being punished, drivers’ perception of the harshness of punitive measures and drivers’ perception of the probability of behavioral change after punishment for DUI.

A sample of 1100 Spanish drivers, 678 men and 422 women aged from 14 to 65 years old, took part in a telephone survey using a questionnaire to gather sociodemographic and psychosocial information about drivers, as well as information on enforcement, clustered in five related categories: “Knowledge and perception of traffic norms”; “Opinions on sanctions”; “Opinions on policing”; “Opinions on laws” (in general and on traffic); and “Assessment of the effectiveness of various punitive measures”.

Results showed around 60% of respondents believe that driving under the influence of alcohol is maximum risk behavior. Nevertheless, 90.2% of the sample said they never or almost never drove under the influence of alcohol. In this case, the main reasons were to avoid accidents (28.3%) as opposed to avoiding sanctions (10.4%). On the contrary, the remaining 9.7% acknowledged they had driven after consuming alcohol. It is noted that the main reasons for doing so were “not having another way to return home” (24.5%) and alcohol consumption being associated with meals (17.3%).

Another important finding is that the risk perception of traffic accident as a result of DUI is influenced by variables such as sex and age. With regard to the type of sanctions, 90% think that DUI is punishable by a fine, 96.4% that it may result in temporary or permanent suspension of driving license, and 70% that it can be punished with imprisonment.

Conclusions

Knowing how alcohol consumption impairs safe driving and skills, being aware of the associated risks, knowing the traffic regulations concerning DUI, and penalizing it strongly are not enough. Additional efforts are needed to better manage a problem with such important social and practical consequences.

In Europe, traffic accidents are one of the main causes of mortality in people between 15 and 29 years old, and driving under the influence of alcohol (DUI) is a major risk factor in most crashes [ 1 , 2 ].

In the year 2001 in Spain, 40,174 people were treated in public hospitals for traffic injuries. Some 28% of these injuries were serious or very serious and drinking was involved in a high percentage of cases. According to the Spanish Directorate General of Traffic (DGT), alcohol is involved in 30-50% of fatal accidents and in 15 to 35% of crashes causing serious injury, constituting a major risk factor in traffic accidents. This problem is especially important among young people and worsens on weekend nights [ 3 , 4 ].

In more recent years, several studies have shown that more than a third of adults and half of teenagers admit they have driven drunk. We also know that most of them were not detected. Generally, the rate of arrests for driving under the influence is very low and even those drivers who were arrested were mostly “first-time” offenders [ 5 ].

Some studies show that many young people lack information or knowledge about the legislation regulating consumption of alcohol for drivers, as well as the effects of this drug on the user [ 6 - 8 ].

There are also some widespread beliefs and misconceptions regarding the actions the driver can take in order to neutralize the effects of alcohol before driving (for instance drinking coffee, having a cold shower or breathing fresh air). As suggested by Becker’s model of health beliefs [ 9 , 10 ], preventive behavior is unlikely to occur unless the subject considers the action necessary, hence the importance of providing adequate information and disproving false beliefs.

Drivers are not usually aware of the risk they assume when they drive under the influence of alcohol, as they do not suffer a traffic accident every time they drink and drive. Hence they tend to think there is no danger in driving under the influence of alcohol, incurring the same risk behavior once and again.

But the reality is quite different. Alcohol causes very obvious alterations in behavior, as it affects almost all the physical skills we need for safe driving. It can interfere with attention, perceptual functioning and motor skills, as well as in decision making while driving.

Drinking impairs the ability to drive and increases the risk of causing an accident. The effects of alcohol consumption on driving-related functions are modulated by some factors, such as form of consumption (regular or infrequent), expectations about their consumption, expertise in driving and driver’s age. The increased risk of accident starts at a lower blood alcohol level when drivers are inexperienced or they are occasional drinkers, and begins at a higher blood alcohol level when these are more experienced drivers or regular drinkers [ 11 , 12 ].

The BAC represents the volume of alcohol in the blood and is measured in grams of alcohol per liter of blood (g / l) or its equivalent in exhaled air.

Any amount of alcohol in blood, however small, can impair driving, increasing the risk of accident. Therefore, the trend internationally is to lower the maximum rates allowed.

After drinking, the rate of alcohol in blood that a driver is showing can vary widely due to numerous modulating variables. Among them, some important factors are the speed of drinking, the type of alcohol (fermented drinks such as beer or wine, or distilled beverages like rum or whisky) or the fact of having previously ingested some food, as well as the age, sex or body weight. Ideally, if everyone drank alcohol responsibly and never drove after drinking many deaths would be avoided. Accurate information about how driving under the influence effects traffic safety would be a positive step towards this goal.

Study framework

Research on enforcement of traffic safety norms has a long tradition. In 1979, a classic work [ 13 ] showed that increasing enforcement and toughening sanctions can reduce accidents as an initial effect, although the number of accidents tends to normalize later.

Justice in traffic is needed insofar as many innocent people die on the roads unjustly. This is our starting point and our central principle. In order to prevent traffic accidents, a better understanding is needed of the driver’s knowledge, perceptions and actions concerning traffic regulations. Drivers have to be aware of how important rules are for safety. The present study comes from a broader body of research on traffic enforcement, designed to develop a more efficient sanctions system [ 5 , 14 ].

Our research used a questionnaire to gain sociodemographic and psychosocial information about drivers, as well as additional information on enforcement clustered in five related categories: “Knowledge and perception of traffic norms”; “Opinions on sanctions”; “Opinions on policing”; “Opinions on laws” (general ones and traffic laws in particular); and “Assessment of the effectiveness of various punitive measures”.

A number of additional factors were also explored, including: driving too fast or at an improper speed for the traffic conditions, not keeping a safe distance while driving, screaming or verbal abuse while driving, driving under the influence, smoking while driving, driving without a seat belt and driving without insurance. For a more complete review, see the original study [ 14 ].

The aim of this study was to gain useful information to improve traffic safety, concerning the following aspects:

Frequency of driving under the influence of alcohol (DUI).

Reasons for either driving or not driving under the influence (DUI).

Perceived risk of DUI.

Drivers’ knowledge of DUI-related penalties.

The perceived likelihood of being punished for DUI.

Drivers’ perception of the harshness of punitive measures for DUI.

Drivers’ knowledge of the penalties for DUI.

Drivers’ perception concerning the probability of behavior change after punishment for DUI.

Sociodemographic and psychosocial factors related with alcohol consumption and driving.

Participants

The sample consisted of 1100 Spanish drivers: 678 men (61.64%) and 422 women (38.36%), between 14 and 65 years of age. The initial sample size was proportional by quota to segments of Spanish population by gender and age. The number of participants represents a margin of error for the general data of ± 3 with a confidence interval of 95% in the worst case of p = q = 50%; with a significance level of 0.05.

Drivers completed a telephone survey. 1100 drivers answered interviews, and the response rate was 98.5%; as it was a survey on social issues, most people consented to collaborate.

Procedure and design

The survey was conducted by telephone. A telephone sample using random digit dialing was selected. Every phone call was screened to determine the number of drivers (aged 14 or older) in the household. The selection criteria were possession of any type of driving license for vehicles other than motorcycles and driving frequently. Interviewers systematically selected one valid driver per home. The survey was carried out using computer assisted telephone interview (CATI) in order to reduce interview length and minimize recording errors, ensuring the anonymity of the participants at all times and emphasizing the fact that the data would be used only for statistical and research purposes. The importance of answering all the questions truthfully was also stressed.

In this article, we present the data on driving under the influence of alcohol. The first question raised was: How often do you currently drive after drinking any alcoholic beverage? Possible responses were: Almost always, Often, Sometimes, Rarely or Never.

If they answered either Almost always, Often or Sometimes, they were asked: What is the reason that leads you to drive under the influence? If they answered Rarely or Never, they were asked: What is the reason you rarely or never drive under the influence? In both cases, respondents had the option of an open answer.

Later they were asked to rate from 0 to 10 the risk that driving under the influence of alcohol can cause a traffic accident in their opinion (0 being the minimum risk and 10 the maximum risk of crash).

Then they were asked to rate from 0 to 10 the harshness with which they thought DUI sanctions should be administered.

They were also asked: Is driving exceeding alcohol limits punishable? In this case, participants had the chance of answering Yes or No . We would then compare the correct answers with the standard to determine the knowledge.

Drivers who were unaware that DUI is punishable were asked about the probability of being sanctioned for this reason using the following question: When driving exceeding the limits of alcohol, out of 10 times, how many times is it usually sanctioned?

Another question dealt with the type of penalties. The participants were asked if the penalties for DUI consisted of economic fines, imprisonment or license suspension, either temporary or permanent. The question raised was: Have you ever received any penalty for driving under the influence? Possible answers were Yes or No . Those drivers who answered affirmatively were then asked about the harshness of punishment: How do you consider the punishment for DUI? The response options were Hard enough, Insufficient or Excessive. Furthermore, they were asked whether or not they changed their behavior after the punishment.

The questionnaire was used to ascribe drivers to different groups according to demographic and psychosocial characteristics, as well as to identify driving habits and risk factors.

Demographic variables

Gender: male or female.

Age: 14-17, 18-24, 25-29, 30-44, 45-65 and over 65 years old.

Educational level.

Type of driver: professional or non-professional.

Employment status: currently employed, retired, unemployed, unemployed looking for the first job, homemaker or student.

Driving habits

Frequency: the frequency with which the participant drive, the possible choices being Every day, Nearly every day, Just weekends, A few days a week, or A few days per month.

Mileage: the total distance in number of kilometers driven or travelled weekly, monthly or annually.

Route: type of road used regularly, including street, road, highway or motorway, and tollway.

Car use: motives for car use, for instance, to work, to go to work and return home from work or study centre, personal, family, recreational, leisure and others.

Experience/risk

Experience: number of years the participant has held a driver license, grouping them as 2 years or less, 3-6, 7-10, 11-15, 16-20, 21-25, 26-30 and over 30 years.

Traffic offenses. Number of sanctions in the past three years (none, one, two, three or more).

Accidents. Number of accidents as driver throughout life (none, one or more than one), and their consequences (casualties or deaths, or minor damages).

Once data were collected, a number of statistical analyses were performed, using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS), in order to obtain relevant information according to the aims of the study.

74.7% of the sample said that they had never driven under the influence. 15.5% of drivers said they did it almost never, and only the remaining 9.7% (sometimes 9,1%, often 0,2% or always 0,5%) acknowledged that they had driven after consuming alcohol (Figure 1 ).

Frequency of DUI.

Regarding the main reasons that led the drivers to act this way, expressed among drivers who admitted to having driven under the influence of alcoholic beverages, 24.5% of them indicated that it was unavoidable, as “I had to go home and couldn’t do anything else”, while 17.3% claimed that the act of drink-driving was an unintentional consequence or “something associated with meals”, and only 16.4% admitted having done it “intentionally”. In addition, 12.7% considered that “alcohol doesn’t impair driving” anyway (Figure 2 ).

Reasons for DUI.

“In any case, 60% of the interviewees perceived driving under the influence of alcohol as the highest risk factor for traffic accidents.”

Among them, the perception of this risk (or dangerousness of driving under the influence) is greater in women [F (1, 1081) = 41.777 p <0.05], adults aged between 18 and 44 [F (5, 1075) = 4.140 p <0.05], drivers who have never been fined for this infraction [F (2, 1080) = 29.650 p <0.05], drivers who had never committed the offense [F (4, 1077) = 40.489 p <0.05], and drivers who have never been involved in an accident [F (1, 1081) = 12.296 p <0.05]. Table 1 shows the values for this perception by gender and age.

There appears to be no significant relationship between the perceived risk attributed to DUI and other variables such as educational level, type of driver, driving frequency, vehicle use and years of experience.

The main reasons put forward for not drinking and driving included not drinking in any circumstances (50,5%), to avoid accidents (28,3%) as opposed to avoiding sanctions (10,4%) - such as financial penalties (8,4%), withdrawal of driving license (1,8%) or jail (0,2%) - or other reasons related to attitudes to road safety (16,6%).

On a scale of 0-10, participants rated the risk of economic penalties when driving under the influence of the alcohol with an average of 5.2, in other words they estimate the probability of being fined as roughly half of the times one drives drunk.

The perception of this risk (penalty or financial punishment for driving under the influence) is also greater in women [F (1, 1095) = 30,966 p <0.05], drivers who have never been involved in an accident [F (1, 1095) = 8.479 p <0.05], and drivers who had never been fined for this infraction [F (2 1094) = 12.515 p <0.05].

There appears to be no significant relationship between the perceived risk of financial penalty and other variables such as educational level, employment, type of driver, driving frequency, vehicle use and years of experience.

Almost everyone (99.1%) thinks that DUI is punishable and only 0.9% of drivers think it is not.

On a scale of 0-10, participants assigned an average of 9.1 to the need to punish this traffic breach severely. The score is higher in women [F (1, 1086) = 29.474 p <0.05], adults aged 18 to 24 years [F (5, 1089) = 2.699 p <0.05], drivers who have never been involved in an accident [F (1, 1095) = 8.479 p <0.05], and people who had never been fined for this reason [F (2, 1085) = 26,745 p <0.05], which means that these groups are less tolerant of this kind of behavior. By age, college students are the least tolerant and retirees are the most tolerant.

There was no significant relationship between the perceived need to punish this behavior harshly and variables such as type of driver, driving frequency and vehicle use.

Regarding the type of sanctions, 89.5% of drivers think that driving under the influence is subject to an economic fine, almost 70% say it could even be punished by imprisonment, while 96.4% believe it can lead to a temporary or permanent suspension of the license (Figure 3 ).

Type of sanction the driver think DUI is subject to.

Among the drivers who had been fined for DUI, nearly 75% considered that the imposed punishment was adequate, while the remaining 25% saw it as excessive (Figure 4 ). Finally, 91.7% of this group found they had changed their behavior after punishment (Figure 5 ).

Perception of punishment harshness imposed for DUI.

Perception concerning behavior change after punishment for DUI.

Alcohol is a major risk factor in traffic accidents. From the objective standpoint, alcohol interferes with the skills needed to drive safely, as evidenced by numerous studies on driving under the influence of alcohol conducted to date. From the subjective point of view, drivers also perceive it as dangerous, as our study shows.

Around 60% of respondents believe that driving under the influence of alcohol is maximum risk behavior. A smaller percentage compared to those reported by other studies in which the percentage of people that saw drink-driving as a major threat to safety reached 81% [ 15 ].

First, we note a clear correlation between perceived risk and avoidance behavior. In general the higher the perceived risk, the lower the probability of committing the offense, and vice versa: the lower the perceived risk, the greater the likelihood of driving after consuming alcohol.

Thus, drivers who do not commit this offense perceive that the risk of accidents associated with DUI is very high. When it comes to drivers who commit the offense occasionally, the perceived risk is lower, and when it comes to drivers who often drive under the influence of the alcohol, the perception of risk is clearly inferior. Thus, the frequency of DUI and risk perception seem to be inversely related.

These results are related to the hypothesis of optimistic bias, which states that drinkers are overly optimistic about probabilities of adverse consequences from drink. In a study [ 16 ] about overconfidence about consequences of high levels of alcohol consumption, the authors established an alternative to the optimism bias hypothesis that could explain our findings, affirming that persons who drink frequently and consume large amounts of alcohol daily could be more familiar with the risks of such behaviors.

Another important finding is that the risk perception of traffic accident as a result of DUI is influenced by variables such as sex and age. In relation to gender, the perception of risk seems to be higher in women than in men. In relation to age, risk perception is higher in adults between 18 and 44 years old.

The finding about the reason for not drinking and driving supports the already evident need for an integrative approach to developing sustainable interventions, combining a range of measures that can be implemented together. In this way, sustainable measures against alcohol and impaired driving should continue to include a mix of approaches, such as legislation, enforcement, risk reduction and education, but focus efforts more closely on strategies aimed at raising awareness and changing behavior and cultural views on alcohol and impaired driving.

Almost all the drivers surveyed are well aware that driving after drinking any alcoholic beverage is a criminal offense. They also consider that this is a type of infraction that should be punished harshly. In this respect, they assign nine points on a scale of ten possible.

Finally, with regard to the type of sanctions, 90% of drivers think that driving drunk is punishable by a fine. 96.4% consider that it may result in temporary or permanent suspension of driving license, and 70% believe that it can be punished with imprisonment.

In any case, there are several limitations of this study. This was a population-based study of Spanish drivers; there is possibly a lack of generalizability of this population to other settings.

Another possible limitation of this study is the use of self-report questionnaires to derive information rather than using structured interviews. Similarly, self-reported instruments may be less accurate than objective measures of adherence as a result of social desirability bias.

In Spain, various traffic accident prevention programs have been implemented in recent years. Some of them were alcohol-focused, designed to prevent driving under the influence and to inform the Spanish population about the dangers associated with this kind of risk behavior.

As a result, many Spanish drivers seem to be sensitized to the risk of driving drunk. As revealed in our survey, many Spanish drivers never drive under the influence of alcohol, and many of them identify DUI as maximum risk behavior. This shows that a high percentage of the Spanish population know and avoid the risks of DUI.

In any case, the reality is far from ideal, and one out of four drivers has committed this offense at least once. When asked why they did it, the two major risk factors of DUI we identified were the lack of an alternative means of transport and the influence of meals on alcohol consumption. Both situations, especially the latter, occur frequently, almost daily, while it is true that the amount of alcohol consumed in the former is considerably higher and therefore more dangerous.

In addition, most drivers are aware of the dangers of driving under the influence, and they tend to avoid the risk of accident or penalty for this reason. Some drivers never drive under the influence, to avoid a possible accident. To a lesser extent, some do not drive under the influence to avoid a possible fine. They usually think that the possibility of sanction in the event of DUI is so high that they will be fined every two times they risk driving drunk.

Moreover, drivers know the legislation regulating DUI and they believe that the current penalty for DUI is strong enough. Nevertheless, even though almost all the drivers that were fined for this reason say they changed their behavior after the event, nine out of ten drivers would penalize this kind of offense even more strongly.

Knowing how alcohol consumption impairs safety and driving skills, being aware of the associated risks, knowing the traffic regulations concerning DUI and penalizing it strongly are not enough. Many drivers habitually drive after consuming alcohol and this type of traffic infraction is still far from being definitively eradicated.

Additional efforts are needed for better management of a problem with such important social and practical consequences. Efforts should be focused on measures which are complementary to legislation and enforcement, increasing their effectiveness, such as education, awareness and community mobilization; Alcolock™; accessibility to alcohol or brief interventions.

Abbreviations

- Driving under the influence

Racioppi F, Eriksson L, Tingvall C, Villaveces A. Preventing Road Traffic Injury: a public health perspective for Europe. Copenhagen: World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe; 2004. Download from: http://www.euro.who.int/document/E82659.pdf . Accessed March 2009.

Google Scholar

Fell JC. Repeat DWI, offenders involvement in fatal crashes in 2010. Traffic Inj Prev. 2014;15(5):431–3.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Pedragosa JL. Analisi dels accidents de transit a Catalunya i causes més rellevants. Anuario de Psicologia/Facultat de Psicologia, Universidad de Barcelona. 1995;65:205–13.

Summala H, Mikkola T. Fatal accidents among car and truck drivers: Effect of fatigue, age, and alcohol consumption. Ergonomics. 1994;36:315–26.

CAS Google Scholar

Alonso F, Esteban C, Calatayud C, Medina JE, Alamar B. La justicia en el tráfico: análisis del ciclo legislativo-ejecutivo a nivel internacional. Barcelona: Attitudes; 2005.

Reppetto E, Senra MP. Incidencia de algunos factores educativos, sociales y afectivos en el consumo de alcohol de los adolescentes. Rev Electron Investig Psicoeduc Psigopedag. 1997;15(1):31–42.

Turrisi R, Jaccard J, Kelly SQ, O’Mally CM. Social psychological factors involved in adolescents’ efforts to prevent their friends from driving while intoxicated. J Youth Adolesc. 1993;22(2):147–69.

Article Google Scholar

Weiss J. What do Israeli Jewish and Arab adolescents know about drinking and driving? Accid Anal Prev. 1996;28(6):765–9.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Becker MH, Maiman LA. Sociobehavioural determinants of compliance with health and medical care recommendations. Med Care. 1975;13(1):10–24.

Rodriguez-Marin J. Evaluación en prevención y promoción de la salud. In: Fernández R, editor. Evaluación conductural hoy. Madrid: Pirámide; 1994. p. 652–712.

Wall IF, Karch SB. Traffic Medicine. In: Stark MM, editor. Clinical Forensic Medicine. A Physician’s Guide. London: Humana Press; 2011. p. 423–58.

Peck RC, Gebers MA, Voas RB, Romano E. The relationship between blood alcohol concentration (BAC), age, and crash risk. J Safety Res. 2008;39(3):311–9.

Kaiser G. Delincuencia de tráfico y prevención general: Investigaciones sobre la criminología y el derecho penal del tráfico. Madrid: Espasa-Calpe; 1979.

Alonso F, Sanmartín J, Calatayud C, Esteban C, Alamar B, Ballestar ML. La justicia en el tráfico. Conocimiento y valoración de la población española. Barcelona: Attitudes; 2005.

Drew L, Royal D, Moulton B, Peterson A, Haddix D. National Survey of Drinking and Driving Attitudes and Behaviors. DOT HS 811-342. Washington, D.C: US Department of Transportation; 2010.

Sloan FA, Eldred LM, Guo T, Yu Y. Are people overoptimistic about the effects of heaving drinking? J Risk Uncertain. 2013;47(1):93–127.

Article PubMed Central PubMed Google Scholar

Download references

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the Audi Corporate Social Responsibility program, Attitudes, for sponsoring the basic research. Also thanks to Mayte Duce for the revisions.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

DATS (Development and Advising in Traffic Safety) Research Group, INTRAS (University Research Institute on Traffic and Road Safety), University of Valencia, Serpis 29, 46022, Valencia, Spain

Francisco Alonso, Juan C Pastor & Cristina Esteban

FACTHUM.lab (Human Factor and Road Safety), INTRAS (University Research Institute on Traffic and Road Safety), University of Valencia, Serpis 29, 46022, Valencia, Spain

Luis Montoro

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Francisco Alonso .

Additional information

Competing interests.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

All authors contributed to the design of the study and also wrote and approved the final manuscript. FA drew up the design of the study with the help of CE; the rest of the authors also contributed. JCP and LM were in charge of the data revision. JCP and CE also drafted the manuscript. FA performed the statistical analysis. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly credited. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Alonso, F., Pastor, J.C., Montoro, L. et al. Driving under the influence of alcohol: frequency, reasons, perceived risk and punishment. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy 10 , 11 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13011-015-0007-4

Download citation

Received : 07 November 2014

Accepted : 02 March 2015

Published : 12 March 2015

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s13011-015-0007-4

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Road safety

- Driving while intoxicated

Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, and Policy

ISSN: 1747-597X

- General enquiries: [email protected]

- Open access

- Published: 10 November 2022

Evaluating the effect of drunk driving on fatal injuries among vulnerable road users in Taiwan: a population-based study

- Hui-An Lin 1 , 2 na1 ,

- Cheng-Wei Chan 3 , 4 , 5 na1 ,

- Bayu Satria Wiratama 6 ,

- Ping-Ling Chen 2 ,

- Ming-Heng Wang 7 ,

- Chung-Jen Chao 8 ,

- Wafaa Saleh 9 ,

- Hung-Chang Huang 10 &

- Chih-Wei Pai 2

BMC Public Health volume 22 , Article number: 2059 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

3672 Accesses

6 Citations

1 Altmetric

Metrics details

Most studies have focused on injuries sustained by intoxicated drivers themselves, but few have examined the effect of drunk driving on injury outcomes among VRUs (vulnerable road users) in developing countries. This study aims to evaluate the effect of drunk driving on fatal injuries among VRUs (pedestrians, cyclists, or motorcyclists).

The data were extracted from the National Taiwan Traffic Crash Dataset from January 1, 2011, to December 31, 2019. Crashes involving one motorized vehicle and one VRU were considered. This study examines the effect of drunk driving by estimating multivariate logistic regression models of fatal injuries among VRUs after controlling for other variables.

Among 1,416,168 casualties, the fatality rate of VRUs involved in drunk driving was higher than that of general road users (2.1% vs. 0.6%). Drunk driving was a significant risk factor for fatal injuries among VRUs. Other risk factors for fatal injuries among VRUs included VRU age ≥ 65 years (adjusted odds ratio [AOR]: 5.24, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 5.53–6.07), a nighttime accident (AOR: 4.52, 95% CI: 4.22–4.84), and being hit by a heavy-duty vehicle (AOR: 2.83, 95% CI: 2.26–3.55). Subgroup analyses revealed a linear relationship between driver blood alcohol concentration (BAC) and the risk of fatal injury among motorcyclists. Motorcyclists exhibited the highest fatality rate when they had a BAC ≤ 0.03% (AOR: 3.54, 95% CI: 3.08–4.08).

Drunk driving was associated with a higher risk of fatality for all VRUs. The risk of fatal injury among motorcyclists was linearly related to the BAC of the drunk drivers. Injuries were more severe for intoxicated motorcyclists, even those with BAC ≤ 0.03%, which is within the legal limit.

Peer Review reports

Alcohol acts as a central nervous system depressant that alters the level of consciousness [ 1 , 2 ] and reduces the attentional and behavioral control of drivers [ 3 , 4 ]. Drunk driving is a risky behavior; drunk drivers may judge the traffic condition improperly because they exhibit overestimation of personal abilities [ 5 ], excessive bravery [ 6 ], and a tendency to be affected by false memory [ 7 ]. Alcohol also interferes with visual acuity, perception, and psychomotor function; reduces reactions to impulses and environmental vigilance; and impairs the postural control of drivers [ 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 ]. Moreover, impaired decision-making [ 14 ] and information processing are evident among drivers with a positive blood alcohol concentration (BAC) [ 15 ]. Simulation studies have also demonstrated negative effects of alcohol on driving speed [ 16 , 17 ], accelerating and braking behavior [ 18 ], and lane positioning [ 19 ].

The positive correlation between drunk driving and motor vehicle crashes (MVCs) has been well documented [ 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 ]. Even with a mildly elevated BAC (0.01–0.03%), drunk drivers cause more MVCs than do drivers who have not consumed alcohol [ 35 , 36 , 37 ]. Drunk driving not only increases the MVC risk but also results in more fatal crashes [ 28 , 38 , 39 ]. Zador et al. revealed that drivers with BACs < 0.1% contributed to more fatal injuries to both themselves and other road users [ 40 ]. Reynaud et al. analyzed the French police records through a 5-year period and found that 31.5% of those who died in an accident had a positive BAC, and 9.8% of them had a BAC over the legal limit [ 41 ]. The detrimental effect of alcohol use has also been confirmed in another French study [ 42 ], suggesting that fatigue, when combined with alcohol, presented a particularly high risk of crashes leading to death or serious injuries. Moreover, the victims of alcohol-impaired driving have higher risks of hospitalization, hypotension, Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) scores, and events of cardiac arrest [ 28 ]. A retrospective analysis of 474 autopsy reports documenting fatalities in traffic crashes revealed 177 victims with a positive BAC [ 39 ]. Substance and alcohol use was also reported to be associated with reduced reaction times [ 43 ], as well as several risky behaviours such as driving without a seatbelt [ 44 ], unlicensed driving [ 45 ], and speeding [ 46 ].

In traffic accidents, vulnerable road users (VRUs)—motorcyclists, bicyclists, and pedestrians—sustain severe injuries and death at a higher rate than motorists. This is because without the protection afforded by a metal structure, VRUs generally sustain more severe injuries than car occupants [ 47 ]. Moreover, car drivers may have difficulty identifying or perceiving VRUs in traffic due to their being poorly visible and having a small size, which may increase the severity of a crash in the event of an accident [ 48 , 49 , 50 , 51 ].

Most studies have focused on injuries sustained by intoxicated drivers themselves, but few have examined the effect of drunk driving towards VRUs (vulnerable road users) in developing countries such as Taiwan. To fill this research gap, we analyzed Taiwan’s national police crash data and investigated the effects of drunk driving with other risk factors on fatal injuries among VRUs.

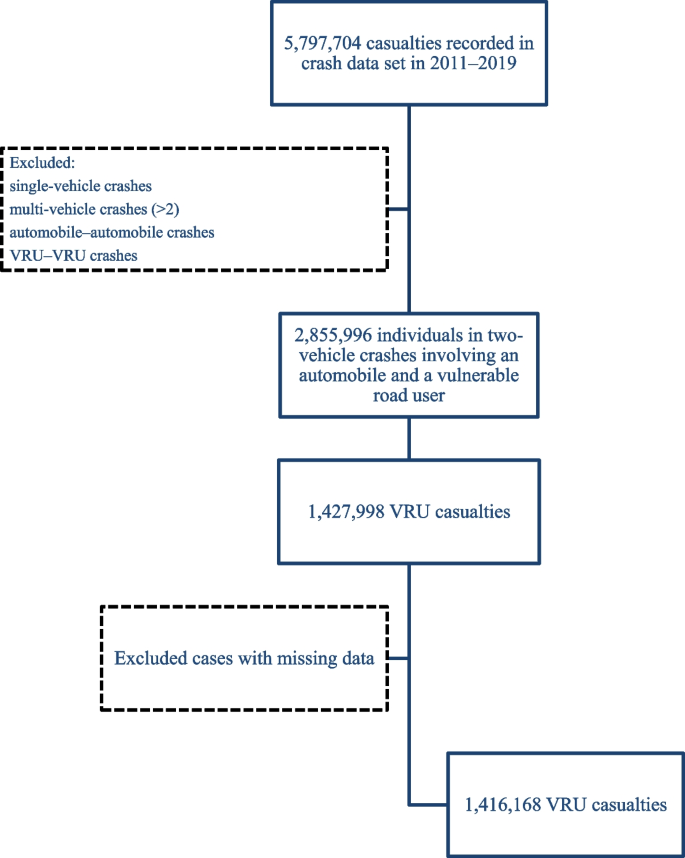

Study participants and data source

This study analyzed the National Taiwan Traffic Crash Dataset from January 1, 2011, to December 31, 2019. The dataset is administrated by the National Police Agency of Taiwan. Experienced police crash investigators are assigned to arrive at the scene and record the information which includes crash, vehicle, and victim files. Crash files contain data on road traffic crash characteristics such as time of crash, date of crash, weather condition, light condition, and various environmental factors (such as geographic location, speed limit, type and condition of road, and apparent distance). Vehicle files contain data on characteristics of the vehicle involved in the crash, such as first point of impact, type of vehicle, and vehicle maneuver. Furthermore, data on victim characteristics such as age, sex, injury severity level, license status, BAC, travel purpose, and restraint use are contained in the victim files. Similar to those in other countries, the Dataset is considered complete for multi-vehicle crashes but less complete for single-vehicle crashes; such an underreporting problem is less of a concern as the present study focuses on multi-vehicle crashes (i.e., an automobile and a VRU). In addition, variables that contain numerous missing data (e.g., hit-and-run crashes) or are unreliable (e.g., mobile phone use) were not considered in the current research. Every road traffic-related crash reported to the police was recorded in the dataset, which is maintained by the National Police Agency of Taiwan. In this study, we focused on crashes involving one automobile and one VRU (motorcyclist, cyclist, or pedestrian). Figure 1 illustrates the data extraction flowchart for this study. We excluded single-vehicle crashes, multiple-vehicle (> 2) crashes, VRU–VRU crashes, and crashes involving no VRUs from the dataset. Finally, we removed cases with missing data because we used a complete case analysis approach for our data analysis. This study was approved by the Joint Institutional Review Board of Taipei Medical University (number: N202007045). The current research analysed national crash data without individuals’ confidential information such as names or identity numbers. As a result, the Institutional Review Board affiliated with Taipei Medical University waived the informed consent.

Selection of casualties

Study variables

Two injury severity levels were recorded: fatal injury (death within 24 h after crash) and nonfatal injuries (sustained injuries and survived for > 24 h). We also collected basic demographic data such as age, sex, participant’s safety behaviors, including helmet use by motorcyclists and bicyclists, BAC level, and the license status of drivers and motorcyclists. Because bicyclists and pedestrians are not required to be tested for alcohol use in the event of traffic accident, their BAC levels were not included in the present analysis.

Temporal variables included in this research were the time of the crash (rush hour, daytime, night, or early morning) and whether the accident occurred on a weekday or weekend. Rush hour was defined as 07:00 AM to 08:59 AM and 5:00 PM to 7:59 PM, daytime was defined as 09:00 AM to 4:59 PM, evening was defined as 8:00 PM to 11:59 PM, and nighttime was defined as 12:00 AM to 06:59 AM.

The following road and environmental factors were analyzed: weather (fine weather refers to sunny and cloudy days; adverse weather includes rainy, snowy, foggy, or sandy conditions and strong winds), and light conditions (no light at night, illuminated at night, morning or dawn, and daytime with natural light; if the incident was in a tunnel or underpass, the setting was deemed night). Taiwan has six municipalities: Kaohsiung, New Taipei, Taichung, Tainan, Taipei, and Taoyuan. Other regions are defined as counties. Several road conditions were considered in this study, including road type (crossroad or not), road surface conditions (slippery road includes snowy/icy, oily, muddy, or damp road), road defect (intact road surface or a defective road, meaning soft terrain, uneven road, or road with pit or hole), and driver’s sightline (clear sight or obstacle in sight). Speed limit was divided into less than 50 km/h and ≥ 50 km/h. Injured body regions of VRUs were categorized as a head and neck injury and other injuries including the chest, abdomen, back, pelvis, and extremities. Table 1 illustrates variables included in analysis.

Statistical analysis

We first compared the distribution of fatal injuries by demographic factors, behaviors, vehicle attributes, crash characteristics, environmental factors, time factors, and crash types. A p value < 0.2 was used as the cutoff point to incorporate risk factors into multivariate analysis. Multiple logistic regression analysis with backward selection was used to calculate the adjusted odds ratios (AORs). Multicollinearity was assessed using Cramer’s V and the chi-square independent test. A subgroup analysis was conducted separately for motorcyclists, bicyclists, and pedestrians. A full model (automobile VRUs) was first estimated, followed by three additional models: an automobile–motorcycle (A-M) model, an automobile–bicycle (A-B) model, and an automobile–pedestrian (A-P) model. Statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05. The binary logistic regression model has been broadly utilized in the field of medicine and trauma [ 52 , 53 , 54 ] to identify the significant risk factors of the dichotomous outcome. In binary logistic regression model, the dependent variable is not limited by the assumptions of a continuous or normal distribution.

In the binary logistic regression model, the equation is formulated as follows:

where x j is the value of the jth independent variable, β j is the corresponding coefficient for j = 1, 2, 3,. .., p, and p is the number of independent variables.

The conditional probability of a positive outcome given the independent variable is as follows:

The maximum likelihood method was used to estimate the parameters of the logistic regression model by constructing the likelihood function:

where y i denotes the ith observed outcome with a value of either 0 or 1 and i = 1, 2, 3,. .., n, where n is the number of observations. The best regression estimation of β was determined by maximizing the log-likelihood expression:

The exponentiated coefficient exp( β j ), odds ratio (OR), demonstrates the effect of attributes on the likelihood of fatal injuries in logistic regression model, with a 95% confidence interval (CI) of (exp( β j − 1.96 sβ j ), exp( β j + 1.96 sβ j )), where sβ is the standard error of coefficient β . An OR of > 1 indicated a positive association between the target independent variable and fatal injuries, whereas an OR of < 1 indicated a negative association between the interest attribute and fatal injuries. An OR of 1 indicated that no association was found between the interest attributes and outcomes. If there were missing data, we conducted a sensitivity analysis to compare data with and without missing data by using the chi-square test. We used IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 22.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp to perform the statistical analysis.

A total of 5,797,704 victims involved in traffic accidents were documented by police from 2011 to 2019. After applying the exclusion criteria, 2,855,996 casualties remained in the automobile–VRU crash category. Half of the casualties in automobile–VRU crashes were VRUs, and the other half were automobile drivers; accordingly, 1,427,998 VRU casualties were included in our analysis. After excluding missing data, 1,416,168 casualties with intact records were analyzed. Figure 1 illustrates the data extraction flowchart for this study. A total of 5,797,704 victims involved in traffic accidents were documented by police from 2011 to 2019. We excluded single-vehicle crashes, multiple-vehicle (> 2) crashes, VRU–VRU crashes, and crashes involving no VRUs from the dataset. Furthermore, we removed cases with missing data because we used a complete case analysis approach for our data analysis. Finally, 1,416,168 casualties with intact records were analyzed.

Table 2 presents the distribution of injury severity across a set of independent variables. Both being hit by a male driver and being a male VRU were associated with higher rates of fatal injuries to VRUs (both were 0.7%). VRUs aged ≥65 years had a higher mortality rate than other age groups. Higher than at other times, 2.9% of fatal injuries occurred at night. Regions outside a municipality (0.8%) and with a speed limit over 50 km/h (0.6%) were associated with a higher rate of fatal injuries. Nighttime with unlit streets was associated with a higher mortality rate (2.4%) than daytime. Fatal injuries were less prevalent under some road conditions, such as being a crossroad (0.6% vs. not crossroad 0.7%), a slippery road surface (0.5% vs. dry surface 0.6%), and an unobstructed view of the road (0.6% vs. with sight obstacle 1.0%). Weather did not significantly affect fatality rates. A positive BAC and a driver being unlicensed were associated with higher rates of fatal injuries among VRUs. Furthermore, the rates of fatal injuries were higher in crashes with buses and trucks (4.1%) and when the casualties were pedestrians (2.7%); bicyclists (1.6%) and motorcyclists (0.5%) had lower fatality rates. Notably, motorcyclists accounted for 91.8% of all VRUs involved in vehicle–VRU crashes. VRUs who sustained head and neck injuries had higher mortality rates (7.2%) compared with VRUs with other injured regions (0.4%).

Table 3 presents the results of the multivariate logistic models of fatal injuries. Male drivers (AOR: 1.55, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.45–1.67) and male VRUs (AOR: 1.63, 95% CI: 1.55–1.72) were both associated with higher risks of fatalities. VRUs aged ≥65 years were over 5 times more likely to sustain fatal injuries (AOR: 5.24, 95% CI: 4.53–6.07) than were younger groups. Fatal injuries among VRUs were more prevalent at nighttime (AOR: 4.52, 95% CI: 4.22–4.84) and in dark environments without illumination (AOR: 2.37, 95% CI: 2.05–2.75). When the travel speed was considered, counties rather than municipalities (AOR: 1.22, 95% CI: 1.16–1.28) and a speed limit ≥50 km/h (AOR: 1.29, 95% CI: 1.21–1.37) both contributed to higher likelihoods of fatal injuries. When the road surface was dry (AOR: 1.34, 95% CI: 1.24–1.44) and driver sight was obstructed (AOR: 1.39, 95% CI: 1.24–1.56), VRUs also had an additional risk of fatal injuries. Road type and road defects were not significant risk factors in multivariate analysis. Alcohol use among drivers was associated with an increased likelihood of fatal injuries to VRUs compared with alcohol nonuse. Drivers with an alcohol level ≥ 0.08% were associated with a higher VRU fatality risk (BAC 0.08–0.11%, AOR: 2.79, 95% CI: 2.14–3.63; BAC ≥ 0.11%, AOR: 2.73, 95% CI: 2.30–3.23). Unlicensed driving (AOR: 2.03, 95% CI: 1.82–2.26) and the accident involving a truck or bus (AOR: 2.82, 95% CI: 2.26–3.55) also appeared to be independent risk factors for deaths. Pedestrians (AOR: 2.17, 95% CI: 2.02–2.32) had a higher mortality rate than did other VRUs. VRUs with head and neck injuries were 12 times more likely to have fatal injuries (AOR: 12.38, 95% CI: 11.78–13.02).

Table 4 presents the results of the subgroup analysis by VRU category. Drivers with a positive BAC were associated with higher odds of fatal injuries in all VRU groups. Driver BAC had a linear relationship with fatality risk among motorcyclists but not among bicyclists or pedestrians. Motorcyclists had the highest risk of death when their alcohol level was as low as 0.01–0.03% (AOR: 3.54, 95% CI: 3.08–4.08). Unlicensed riders also had a higher risk of fatalities (AOR: 1.71, 95% CI: 1.59–1.84). With regard to the effect of unlit darkness, the magnitude of the increased risk of fatal injury was the highest for pedestrians (AOR: 3.57, 95% CI: 2.68–4.76), followed by that for bicyclists (AOR: 2.66, 95% CI: 1.77–3.99) and motorcyclists (AOR: 1.55, 95% CI: 1.27–1.89).

Our study demonstrated that VRUs had additional risks of fatal injuries caused by drunk drivers after controlling for other variables. The higher the alcohol concentration of the driver was, the worse the fatality rates for the VRUs were, and this conclusion is in line with previous research [ 55 , 56 , 57 , 58 ]. A linear relationship was noted between driver BAC and the risk of fatalities among motorcyclists but not among cyclists and pedestrians. Such effects are likely attributed to several dimensions. First, in spite of speed data were not available in the Dataset, motorcyclists are generally moving much faster than those cycling or walking, thereby in turn leading to more devastating crash impacts [ 59 , 60 , 61 , 62 ], less reaction time [ 63 ], and high tendencies to lose control [ 64 ]. High traveling speed of motorcycles, relative to other VRUs, may act synergistically with driver BAC to increase injury severity. Such a linear relationship is likely due to the traffic exposure: fewer cyclists and pedestrians, compared with motorcycles, travel on roadways with higher speed limits. Our conjecture here needs to be ascertained in future research with additional data on crash locations and speed. While drunk driving appeared to be the main risk factors for fatal injuries among vulnerable road users, other studies [ 65 ] pointed out that mobile phone use may compromise pedestrians’ safety. Due to a lack of reliable data on mobile phone use, we identify this as a fruitful area for future studies.

Our data also highlighted that drunk riding increases motorcyclists’ mortality rate, concordant with previous research [ 66 ]. Notably, motorcyclists experienced the highest fatality rate at a legal BAC level (0.01–0.03%). In contrast to drivers, riders had the peak of fatality rate in a relative low BAC, and one early study also concluded that a low BAC level was associated with more crashes in motorcyclists than in drivers [ 67 ]. The relation between the risk of motorcyclists and their low BAC could attribute to the complexity of motorcycling, which requires concentration, balance, control and precision of movement through curves, and familiarity with the operation of the motorcycle [ 68 ]; these skills, especially balance, can be impaired at even a low alcohol concentration [ 69 , 70 ]. Creaser and colleagues suggested that although riders with a low BAC preserved their cognitive and visual ability, they had to concentrate more on maintaining their riding balance, thereby sacrificing attention to cornering and hazard perception [ 68 ].

Traveling at night is generally considered risky due to poor visibility [ 56 , 71 , 72 , 73 , 74 , 75 , 76 ]. In our data, VRUs had the highest risk of fatalities during night hours (00:00 AM to 06:59 AM), and pedestrians exhibited an additional increment in fatalities in this time frame. Compared with motorcycles and bicycles, pedestrians usually have less or no lightning instruments or reflectors, and drivers are prone to miss them in dim light. Furthermore, pedestrians also are smaller in size than other road users (i.e., machines), making them more difficult to be observed at night [ 77 ]. Appropriate measures to prevent crashes in dark environments include enhancing VRUs’ visibility through the use of lighting equipment or reflective clothes.