4.5 Subculture Theories

The dominant culture is the majority group that has its certain norms, values, and preferences that are imposed on everyone else. This culture is forced on everyone as the accepted way to live, behave, and believe whether or not groups who are not represented in this dominant majority agree and even when they contradict what is preferred for smaller, less powerful groups. These other groups have their own subculture, which may not align with the dominant culture.

A subculture is an identifiable subgroup within the larger culture whose values may differ from those present in the dominant group. This could include specific standards of behavior that are learned and passed down from generation to generation, for example. Crime, gangs, violence, and inner-city neighborhoods have been studied in a manner that ties the concept of subculture to criminal and even violent behavior.

4.5.1 Gangs

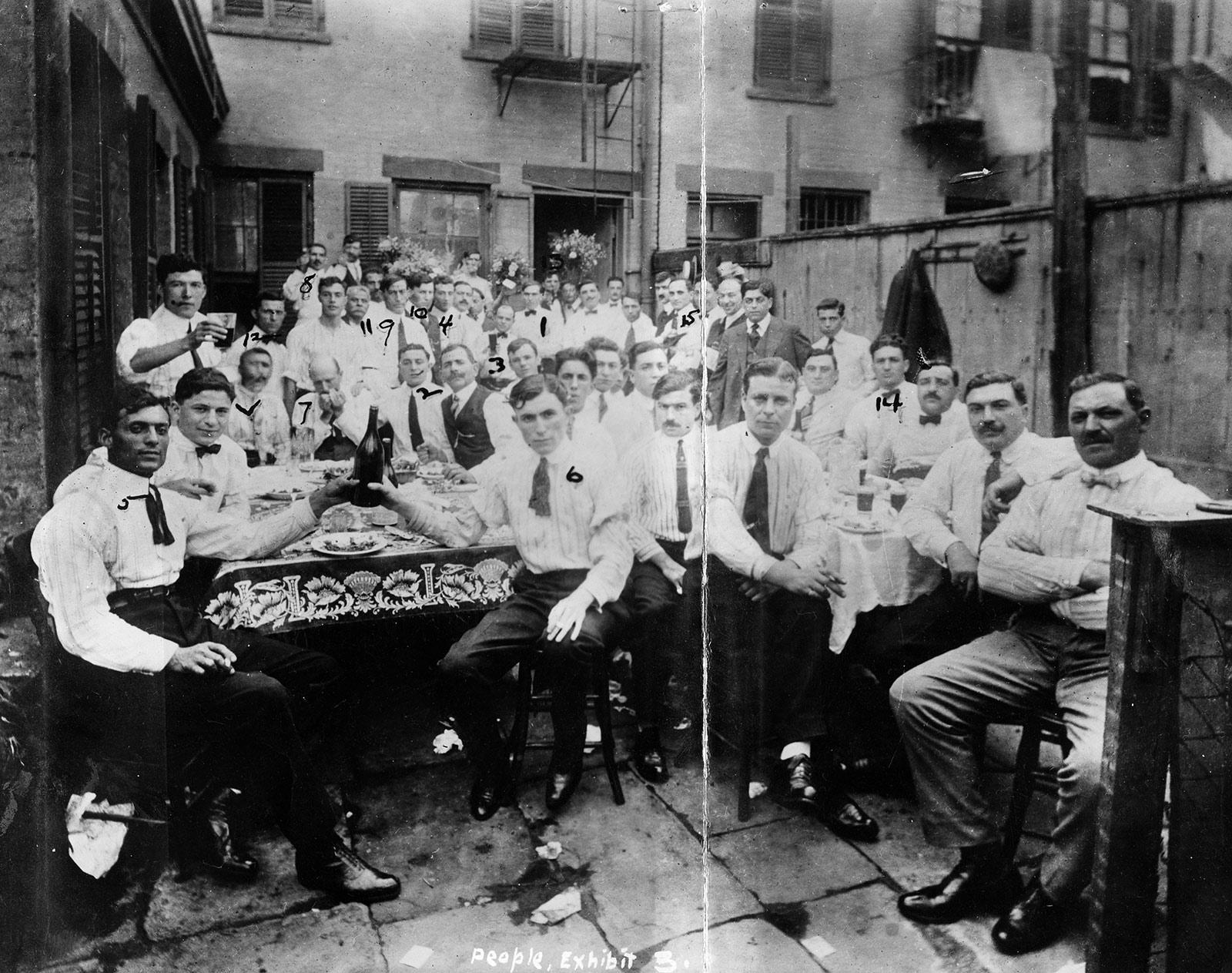

Figure 4.6 Photograph of the Navy Street gang in Brooklyn, New York used as a prosecution exhibit at trial in 1918.

Frederic Thrasher, another sociologist from the famed Chicago School, conducted a classic study in 1927 in which he described gangs as coming together spontaneously at first, then becoming integrated through conflict with other gangs and the surrounding community. The gangs had similar features to formal organizations, such as an identity as a group, stability, commitment, exclusivity, and an internal structure with distinct statuses and roles (figure 4.6).

Thrasher’s study included 1,313 gangs that each occupied a part of Chicago. He believed that the social conditions in the United States at the end of the nineteenth century encouraged the development of street gangs. An influx of immigrants filled the inner-city neighborhoods and they created a more culturally diverse population that was subjected to deteriorating housing, poor employment prospects, and a rapid turnover in the population. The conditions created socially disorganized neighborhoods (remember social disorganization theory) with weak and ineffective social institutions and social control mechanisms. It was this lack of social control that Thrasher believed encouraged youth to discover alternative ways to establish social order which was accomplished by forming gangs.

4.5.2 Violence

American criminologist Marvin Wolfgang and Italian criminologist Franco Ferracuti (1982) developed the subculture of violence theory in which they used norms and values as explanatory variables for the origin of violent crime. They implied that norms of behavior are created in social conditions, social classes, and ethnic and racial groups. Wolfgang (1958) conducted a study on homicide in Philadelphia and discovered evidence consistent with his and Ferracuti’s theory. Forty-three percent of the homicide offenders had been arrested previously for crimes against persons with about one-fourth of homicide victims having been previously arrested for violent crimes. The conclusion is that there are certain groups in certain areas where there exists a norm that favors the use of violence to deal with conflict and it is seen as normal in these communities.

For some, violence is more common during their youth, but as they become older, they distance themselves from the violence that once may have been common. Reacting to situations with violence is a learned behavior that can be unlearned.

4.5.3 Code of the Streets

In 1990, Elijah Anderson published his findings of a study that looked at Black neighborhoods along Philadelphia’s Germantown Avenue in his book The Code of the Street . In his study, Anderson detailed the aspects of the code of the street, or street culture, that stressed a hyperinflated notion of manhood that centers on the idea of respect. According to Anderson, respect was defined as being treated right or being granted one’s props or the deference an individual deserves. Learn directly from Anderson about his book here .

In the code, a man’s sense of worth is determined by the respect he can command in public. How is this respect gained? Anderson found that since they lived in a subculture that was violent, an individual could not back down from any threat no matter how serious. Also, since economic and social circumstances limited opportunities for legitimate success, many tried to find alternative ways of making money to provide for their families.

One major distinction that Anderson made was between both families and people in the inner-city neighborhoods by dividing them into two different groups: decent families and street families. “Decent families” upheld positive values. Conversely, “street families” were oriented to the values of the streets which involved displays of physical strength and intellectual prowess that demonstrated their ability to take care of themselves and their families.

The code was helpful to achieve success on the streets but was very detrimental when it came to socially accepted (and legal) success. Violence in society does not generally increase opportunities, rather it actually limits opportunities. This makes for a difficult transition for individuals who wish to leave “the life” but do not have the skills to achieve success in a society where one doesn’t benefit from being street-smart.

4.5.4 Licenses and Attributions for Subculture Theories

“Subculture Theories” by Curt Sobolewski is licensed under CC BY 4.0 .

Figure 4.6 Photo by unknown photographer is in the Public domain , via Wikimedia Commons.

Introduction to Criminology Copyright © by Taryn VanderPyl. All Rights Reserved.

Share This Book

- Tools and Resources

- Customer Services

- Corrections

- Crime, Media, and Popular Culture

- Criminal Behavior

- Criminological Theory

- Critical Criminology

- Geography of Crime

- International Crime

- Juvenile Justice

- Prevention/Public Policy

- Race, Ethnicity, and Crime

- Research Methods

- Victimology/Criminal Victimization

- White Collar Crime

- Women, Crime, and Justice

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Article contents

Crime, diversity, culture, and cultural defense.

- Clara Rigoni Clara Rigoni Max Planck Institute for Foreign and International Criminal Law

- https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190264079.013.409

- Published online: 30 July 2018

Contemporary societies are culturally diverse. This diversity can be the result of different historical and social processes and might affect the uniformity and efficiency of criminal justice systems. Colonization of indigenous populations that started in the 15th century later European colonization of Africa and migration flows following the Second World War have contributed to this diversity in different ways. The growing importance acquired by culture in the criminal law domain went hand in hand with the attention received by it both in the human rights field (especially linked to minority rights) and in the field of sociological and criminological theories.

Nowadays, crimes such as female genital mutilation, forced marriages, and other behaviors grounded in “culture or tradition” form the object of several international human rights instruments and media reports. The way in which criminal justice systems deal with such cases, and more in general with cultural factors, varies greatly. Different instruments have been proposed to allow the consideration of cultural elements within criminal proceedings among which (in common law countries) is the formalization of an autonomous “cultural defense.” However, international human rights instruments, especially those protecting the rights of vulnerable subjects such as women and children, have repeatedly discouraged states to take into account “culture, religion, and tradition” as grounds for justification (see, e.g., the Istanbul Convention).

Criminal proceedings are not the only setting to deal with culture and crime. More recently, the development of alternative dispute resolution mechanisms and restorative justice both within formal and informal (community) settings have given an additional option to take culture into account in the resolution of disputes (in terms of procedures used and normativities in play). Concerns exist with regard to the substantive and procedural rights of participants to these programs. However, these alternatives could represent a way to allow a certain degree of legal pluralism and facilitate access to justice for minority groups.

- indigenous people

- immigration

- cultural defense

- alternative dispute resolution

- restorative justice

A Definition of “Culture”

A first question to be posed when dealing with crime and culture is what we intend with the term “culture.” The definition of culture has been at the center of the debate among cultural anthropologists for centuries. The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) recalling a definition given by the English anthropologist Edward Burnett Tylor has defined culture as “that complex whole which includes knowledge, beliefs, arts, morals, laws, customs, and any other capabilities and habits acquired by a human as a member of society” (Tylor, 1871 ; UNESCO website). During the course of the 20th century , a myriad of definitions and approaches to culture characterized different trends in social and cultural anthropology (and many other disciplines). While some scholars (Kroeber & Kluckhohn, 1952 ; Parsons, 1951 ) understood culture merely as a system of values, beliefs, and normative standards, later doctrine (Bourdieu, 1977 ; Ortner, 1984 ) associated culture with action and practices (Merry, 2003 ). A great deal of the discussion on culture, developed in the second half of the 1900s, revolves around the quarrel between those who describe culture as something static, monolithic, well-defined, and those who underline the need for looking at it as a practice, a process in constant transformation exposed to both external and internal challenges. In the last few decades, an increasing number of social and cultural anthropologists have denounced the risk that conceiving culture as static and homogeneous brings in terms of its compatibility with human rights. According to these scholars, the only way to reconcile culture (and cultural diversity) with human rights is to recognize that cultures are often hybrid, complex, and in a process of constant transformation (Parolari, 2016 ). “Essentializing” cultures risks to conceive them as separate entities; overemphasize their boundaries; and favor stereotypes and prejudices about them but also to portray them as internally homogeneous and silence the voices of those members that do not share or criticize certain practices and traditions (Benhabib, 2002 ). Even if certain aspects of a culture endure over time and are transmitted from one generation to another, it is also true that cultures themselves are exposed to a variety of factors, including other cultures that have an impact on their preservation and transformation. This phenomenon is known as “acculturation” and takes place when individuals coming from different cultural groups come into contact with each other and change their cultural patterns as a result of this contact (Redfield, Linton, & Herskovits, 1936 ; Renteln, 2004 ). It was so during the past, under big empires, during colonization, and it is even more so in today’s globalized societies, where communication, contact, and exchange among people coming from different parts of the world have become very easy. The same is true for migrants belonging to second or third generations, who are exposed to a variety of cultures and often contribute to change them from within. Admitting that cultures are heterogeneous and not always uniform also means recognizing the existence of a plurality of voices and positions with regard to certain specific cultural practices. The different attitudes individuals might have toward a given tradition might be due to a variety of factors, such as gender, age, individual beliefs, level of exposure to other cultures, and many other structural factors (including, of course, socioeconomic ones) (van Broeck, 2001 ). Individual identities can be described by a plurality of collective narratives and in most cases cannot be reduced to defined ethnic, religious, cultural, or linguistic boundaries (Benhabib, 2002 ). Undisputed is, however, that culture affects, to a certain extent, individual perceptions and behaviors. This phenomenon has been named by social anthropologists “enculturation,” a concept that refers to “the process of socialization into and maintenance of the norms of one’s indigenous culture, including its salient ideas, concepts and values” (Kim, Ahn, & Lam, 2009 , quoting Herskovits, 1948 ). Conrad Philipp Kottak defines enculturation as:

the process where the culture that is currently established teaches an individual the accepted norms and values of the culture or society where the individual lives. The individual can become an accepted member and fulfil the needed functions and roles of the group. Most importantly the individual knows and establishes a context of boundaries and accepted behaviour that dictates what is acceptable and not acceptable within the framework of that society. It teaches individuals their role within society as well as what is accepted behaviour within that society and lifestyle. (Kottak, 2007 )

Each individual internalizes certain elements of one (or more) culture that he/she learns through socialization. These cultural influences are so deep that they are reflected in one’s behavior, even subconsciously (Linton, 1955 ).

Cultural Diversity in Contemporary Societies

As mentioned in the previous paragraph, contemporary societies are culturally diverse. This diversity can be the result of different historical and social processes and might affect the uniformity and efficiency of criminal justice systems. Among these processes, those that mostly influenced the pluralization of our societies in the last few centuries, three are worth mentioning: the colonization process initiated by European settlers at the end of the 15th century that destroyed indigenous peoples’ cultures and justice systems in different parts of the world and the subsequent attempt to restore the damages caused by the so-called conquista; later colonization processes in sub-Saharan Africa and the introduction of a two-layer system of (European) state law and customary law; and the huge migration flows directed to European and North American states that followed the Second World War and caused a diversification in the population of these countries and the increase of cultural clashes.

Indigenous Peoples

Colonial (and neocolonial) processes that took place in the last six centuries in countries such as Canada, the United States, Australia, New Zealand, and Latin American states strongly affected the development of indigenous populations living in these territories. Upon their arrival, European settlers did not only take control of the land and natural resources but also of educational, cultural, religious, and justice institutions. This resulted in the partial destruction of indigenous culture, values, social and political organization, and brought to the socioeconomic marginalization of indigenous groups within new colonial societies. The level of marginalization varies depending on several factors, especially on the territorial distribution of indigenous peoples, often confined in remote areas such as reservations or indigenous protected areas where they are granted a certain degree of sovereignty (Cunneen & Tauri, 2016 ; Nielsen & Robyn, 2003 ). One of the areas in which this marginalization is more evident is that of criminal justice. The overrepresentation of indigenous populations within the criminal justice system, with regard to both victims and offenders, is a common trait of all settler colonial states. The reasons for such an overrepresentation are many and go from socioeconomic conditions, unemployment, and widespread substance abuse, to racism and discriminatory attitudes of criminal justice authorities in policing, charging, judging, and sentencing indigenous people. Little access to justice and legal aid also contribute to increased levels of victimization and to higher incarceration rates. Moreover, in the colonial process criminal law (and criminalization) became a way to impose new sociocultural values and a new social order, to legitimize the use of force by the colonizers on indigenous people, to increase control and policing over these communities, and reduce their political and institutional independency (Anthony, 2013 ; Cunneen & Tauri, 2016 ; Monchalin, 2016 ). It should not surprise, therefore, that indigenous claims for self-determination often go through requests for autonomy within the criminal justice sphere.

In order to accommodate these claims and to reduce the overrepresentation of indigenous people in prison, several countries have recognized indigenous traditional programs as an alternative or a supplement to the formal criminal justice system (see, among others, Canada, the United States, Australia, and New Zealand). These programs are run by the justice system in cooperation with indigenous groups; they employ indigenous (and sometimes also non-indigenous) personnel; they make extensive use of rituals, alternative forms of punishment, community policing, and community-based sanctions that better respond to the group’s idea of (substantive and procedural) justice, which often rests on a restorative rather than retributive conception. Ideas of law and justice within indigenous groups differ from colonial ones under several aspects. Collective responsibility for the wrongdoing overrides the individual one; ideas of “guilt” and “innocence” do not exist in many indigenous cultures; the role of the victim and the community (and their restoration) becomes crucial in the judicial process. Examples of traditional programs are family group conferences, peacemaking circles, sentencing circles, and elder panels, where the victim and the offender accompanied by their supporters and/or family members sit together with other members of the community, including community leaders and elders, in order to find a solution to the conflict and repair the harm done (Cunneen & Tauri, 2016 ; Morris & Maxwell, 2003 ; Williams, 2002 ).

Concerns exist with regard to guarantees offered to vulnerable subjects, especially women and children. The use of traditional programs for crimes such as domestic and sexual violence is regarded with high skepticism. Criticisms are related to the concern that communities might condone harmful practices and undermine the rights of victims. Despite these risks, however, these programs are also seen as a way to reaffirm indigenous culture and tradition, and the culturally sensitive procedures that they entail are practices to which the community is accustomed and are therefore seen by many as capable of empowering victims and of facilitating their access to justice (Jahan, 2008 ).

Colonialism in Africa

European colonization of Africa (especially sub-Saharan Africa) started at the end of the 18th century . Law was the instrument through which colonial powers imposed their control on colonized territories and sought to transform these societies and impose a new culture. European colonizers brought with them their legal systems and imposed values and rules on the colonized countries initially through existing institutions. With the increase of colonial power, a set of state courts was developed in order to allow the enforcement of Western laws for Europeans. African courts, especially in rural areas, were instead charged with the enforcement of indigenous (precolonial) law. This resulted in the creation of a dual system, one for the colonizers and one for the colonized, and it marked the beginning of a policy of legal pluralism that in many cases survives until now. The contact with Western values and the need for adapting to a new economic and social context produced a transformation of indigenous laws, culture, and traditions, giving rise to what we define as “customary law,” which partially differs also from precolonial law (Kämmerer, 2008 ; Merry, 1991 ; Tamanaha, 2015 ).

Postcolonial countries are still struggling to reconcile this dual system and to decide which law has to be applied in which courts. In many former colonies, the partition between official legislation enforced by state institutions and customary norms adopted by informal courts can still be found today and usually reflects a division between urban and rural areas. Here, state institutions are often weak or nonexistent, and the organization of the population (e.g., in tribes or kin groups) facilitates the survival of customary or traditional courts run by tribal elders and community leaders (Merry, 1991 ; Tamanaha, 2015 ). Traditional and informal mechanisms also exist in certain areas of North Africa, the Middle East, and South East Asia, especially in areas where formal justice institutions are missing or are lacking legitimacy and political authority (Chirayath, Sage, & Woolcock, 2005 ; Wardak, 2004 , 2006 ). This is not only the case in colonized territories but also in post-conflict societies where both accountability and reconciliation are needed. Recently, governmental and non-governmental organizations have promoted the development of alternative and informal mechanisms as part of a grassroots and more informal approach to justice in order to facilitate access to justice, conciliation, and local control (Jahan, 2008 ; Merry, 1991 ; Sullo, 2016 ).

The situation is even more complicated in countries, such as Togo or Uganda, in which several colonial administrations (German, French, British, etc.) followed one another. Here the postcolonial scenario is even more fragmented. State law consists of several layers of different Western legislation, which contributed to shape, and nowadays interact with the customary law of the colonized territory.

Immigration After the Second World War

A third factor of cultural diversity in contemporary societies is the phenomenon of immigration. Contemporary international migration is unprecedented to what concerns its scale, character, and intensity (Orgad, 2015 ). On the global level, the number of migrants has increased steadily in the last decades and has doubled or even tripled in developed countries such as the United States and Europe. The so-called European migration crisis has led to an escalation in the increase of third country nationals in Europe, which became the destination for millions of migrants, refugees, and asylum seekers arriving to Southern European countries through the Mediterranean and the Balkan routes. Eurostat estimates that as of January 1, 2016 , the non-EU citizens living in the 28 European states were 20.7 million, a number that is intended to grow in the next years (Eurostat Migration and Migrant Population Statistics). Also, the character of migration somehow changed in the last century. During the 19th and the beginning of the 20th centuries , migration flows were mainly restricted to the Western world (typically, although not only, from Europe to North America) and consisted of labor migrants who moved to another country usually for a limited period of time (Orgad, 2015 ). After the end of the Second World War, refugees’ movements across the globe and the end of colonization changed this pattern. Former colonial powers, for instance France and the United Kingdom, started receiving immigrants from their previous colonies, while Northern European countries recruited labor forces from Southern Europe and later on Eastern Europe. Family reunification started acquiring importance and brought a certain stability to migration, previously mainly seen as temporary (Orgad, 2015 ; De la Rica, Glitz, & Ortega, 2013 ; Stalker, 2002 ; Weissbrodt, 2014 ). Nowadays, the majority of migrants crossing European borders come from the Middle East (in particular Syria, Afghanistan, and Iraq), Pakistan, and sub-Saharan Africa (UNHCR-Refugee/Migrants Emergency Response). Next to more traditional labor migrants, both asylum seeking and family reunification play a major role in this process. The intensity of contemporary migration is also remarkable. The pace at which migrants are arriving in Europe is rapidly changing demographic trends in these countries. Western population and the total fertility rate in Western countries are declining, and in many European cities the growth of the migrant population is faster than that of the non-migrant population (Orgad, 2015 ).

High levels of social, cultural, and religious heterogeneity resulting from these processes challenge the model of nation-state on the basis of which European and North American states are organized since centuries (Algan, Bisin, & Verdier, 2012 ). Nation-states used to rely on a strong concept of sovereignty exercised through the instrument of citizenship, the only relevant criterion of affiliation. All other identity (collective) dimensions, such as ethnicity or religion, were meant to fade in front of a universal idea of the right-bearing individual. In the 1980s/1990s, the claims of minority groups to see their cultures, religions, and traditions recognized within Western liberal states brought to the adoption of multicultural policies aimed at the accommodation of minority rights in the public sphere. The traditional conception of citizenship, based on the belonging to a nation-state was juxtaposed to a new idea of multiple belonging and collective identity. The recognition of difference became essential to reach equality at a broader level (Carens, 2000 ; Comaroff & Comaroff, 2003 ). However, the so-called war on terror initiated after the 9/11 attacks in New York and the peak in the migration flows directed toward Europe and North America, together with the growing claims of autonomy coming from minority groups, have somehow reversed the trend and have brought the discourse on integration at the center of the political agenda of most European countries. The perceived threat to Western liberal values and the revival of national identities have led to a retreat from multiculturalism and to the rise of nationalist movements (Algan et al., 2012 ; Orgad, 2015 ). Clashes between minority and majority groups are framed in human rights terms and become particularly heated in the area of criminal law. Violence against women and children (such as female genital mutilations, forced marriages, sexual and domestic violence, etc.) and discourses on gender roles are often at the center of the debate. The plurality of normativities to which members of minority groups are subjected is perceived to threaten an ideal universal conception of rights and principles such as equality, freedom, justice, and autonomy, while the claims for jurisdictional autonomy coming from minority groups challenge the value-imposing function of criminal law and fundamental principles such as the rule of law and the monopoly of the state over the use of violence.

The Relationship Between Culture and Crime

In some ways, all crime is related to or influenced by culture. However, in the last few years, the attention of the international community and of Western liberal democracies has increasingly focused on the relationship between crime and culture and especially of certain cultural traditions. In the last few decades Europe has witnessed the arrival of flows of Muslim immigrants that have revitalized the debate on religion. While in the past, religiosity was connected to the idea of law-abiding citizens, nowadays religion, especially Islam, is often associated with violence. In this discourse religion and culture have been used interchangeably, and the latter has often provided an alternative to avoid discussing sensitive issues such as freedom of religion. Other reasons have contributed to associate culture with crime; among those, two are worth mentioning: the growing importance of culture within the human rights scenario and the development of criminological theories focused on the interaction between culture and crime.

Human Rights and the Right to Culture

The place occupied by culture within the human rights discourse is highly debated. While initially the recognition of culture and cultural differences was seen as an obstacle for the pursuit of (universal) individual human rights, later on the supporters of cultural relativism reversed this opposition. During the 20th century , many international instruments started recognizing the value of cultural features and protecting them, at first in the form of individual rights, later on also under the category of group (collective) rights. Starting from the 1980s, international and supranational institutions increasingly focused on minority rights and cultural diversity, especially, although not only, in connection with indigenous peoples’ claims. Such claims related mainly to issues of self-determination, cultural autonomy, language rights, control over land and national resources, possibility of exercising traditional practices, right to specific education, and exemptions from laws (Cowan, Dembour, & Wilson, 2001 ; Firestone, Lily, & Torres de Noronha, 2005 ; Henrard, 2013 ; Wenzel, 2011 ).

Through a process that has been named “culturalization of human rights law” (Lenzerini, 2014 ), culture became a human right of its own. Today, the right to culture is enshrined in many international human rights documents (see, among others, article 27 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights; article 15 of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights; and article 27 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights). The UNESCO Universal Declaration on Cultural Diversity, adopted in 2001 , recognizes the value of cultural diversity as a “common heritage of humanity” (art. 1). It underlines the value of cultural diversity and cultural pluralism for democratic societies and fosters the implementation of cultural rights as an integral part of human rights. Of course, being the right to culture (and to cultural diversity) fully recognized as a fundamental right, it is also subject to the limits, which derive from the universal, indivisible, and interdependent character of human rights. Article 4 of the Declaration clearly states that “no one can invoke cultural diversity to infringe upon human rights guaranteed by international law, nor to limit their scope.” This limitation becomes particularly important in the relationship between culture and crime.

Criminological Theories Investigating the Role of Culture in Crime

During the first half of the 20th century , the concept of culture became central also to another field of study, that of sociology and, in particular, of criminology. The interaction between cultural and criminal practices was at the heart of several criminological theories, which developed between the 1930s and the 1960s, such as the culture conflict theory and subcultural theories. These theories saw crime as a collective behavior, resulting from the adherence to a (sub)cultural group, different from the dominant one.

Thorsten Sellin and the “Culture Conflict Theory”

In the 1930s, the Swedish American sociologist Thorsten Sellin developed the culture conflict theory , which explains crime as a conflict between different conduct norms regulating the behaviors of (groups of) individuals (Sellin, 1938 ). Drawing from cultural anthropology studies, Sellin defines conduct norms as a product of social life, aimed at protecting the social values of a group. These norms “define the reaction or response which in a given person is approved or disapproved by the normative group” when this person is acting under certain circumstances (Sellin, 1938 ). While acting in his/her daily routine, a person is supposed to conform to the conduct norms of the group(s) he/she belongs to, such as the familial, religious, political, or other groups. It might happen that one specific life situation is simultaneously regulated by a plurality of conduct norms (deriving from the different social groups of which an individual is a member) and that these norms fail to agree with each other. By breaching one of these conflicting rules, an individual adopts what, in the eyes of the relevant social group, is considered an “abnormal” (deviant) conduct. If, however, the rule infringed coincides with a criminal norm in force in the dominant society, this deviant behavior amounts to crime (Sellin, 1938 ). Sellin further distinguishes between what he calls primary and secondary conflicts. Primary conflicts occur when the norms of two different cultures (or cultural codes) clash. They may arise when two different codes regulate two contiguous areas; when the law of one group is extended to the territory of another group (as in the case of indigenous peoples or colonized territories); or, finally, when members of one cultural group migrate to another group. Secondary conflicts, by contrast, are the result of a process of “social differentiation,” that is to say of the evolution and fragmentation of one single culture into several ones. As mentioned, primary conflicts are typical of indigenous populations, colonized territories, and first-generation (foreign-born) migrants, who often preserve their loyalty to the norms of their original group and fail to assimilate to the behavioral and/or legal norms of the “new” dominant society. Secondary conflicts characterize, among others, the behavior of second-generation migrants. These individuals are often caught between two or more cultures, and their behavior is therefore influenced by different normative orders. While receiving a certain education within their families, they are at least partially acculturated with the norms of the host society. The result is confusion in their standards and codes of behavior and an internal struggle between conflicting forces (Adler, Mueller, & Laufer, 2013 ; Foblets, 1998 ; Melossi, 2015 ; Sellin, 1938 ).

The Chicago School and Subcultural Theories

Subcultural theories were developed in the context of the Chicago School of Sociology, which since the beginning of the 1900s focused on the study of urban sociology, in particular of immigration and minority communities. A subculture is defined as a “subdivision within the dominant culture that has its own norms, beliefs, and values” (Adler et al., 2013 ). Subcultural theories explain crime as a collective phenomenon, resulting from the adherence to values and norms, which are different from those of the dominant society. In situations of marginalization from the mainstream society, individuals bond together and develop their own norms, beliefs, and symbols, creating new identities and ways of life. In his Delinquent Boys ( 1955 ), Albert Cohen develops Merton’s theory of anomia to explain what he calls the “gang culture.” According to Cohen, youth from lower socioeconomic classes fail to achieve success within the mainstream (middle-class) society because of their disadvantaged backgrounds. The frustration resulting from this failure brings them to a refusal of the values of the middle class and pushes them toward subcultures, where they can aim at achieving success and status by committing crime. Walter Miller further developed Cohen’s theory rejecting, however, the role assigned by the latter to middle-class values. According to Miller, members of subcultures conform to a different set of values, which are different from and not influenced by those of the middle class. These lower-class values include, among others, toughness, smartness, and autonomy and are often demonstrated through the commission of crime (Adler et al., 2013 ; Cohen, 1955 ; Ferrell, 1995 ; Miller, 1958 ; Nwalozie, 2015 ).

Behaviors Resulting From the Influence of Cultural (and Subcultural) Values

Situations in which individuals commit acts that are influenced by the cultural norms of the minority group of which they are part but are contrary to the criminal laws of the dominant society have been named by certain doctrine as cultural offenses or culturally motivated crimes . According to Jeroen van Broeck a cultural offense is an:

act by a member of a minority culture, which is considered an offence by the legal system of the dominant culture. That same act is nevertheless, within the cultural group of the offender, condoned, accepted as normal behaviour and approved or even endorsed and promoted in the given situation.” (van Broeck, 2001 )

This definition is, however, too vague to provide clear criteria that could help assessing the role that culture had in the commission of the crime and the weight that it should be given in the criminal proceeding. The examples that follow might help identifying those behaviors that often have been labeled by the doctrine as cultural offenses.

Examples of Behaviors

The dynamic character of cultures and traditions and the difficulties encountered in identifying cases in which a cultural element is crucial in the offense make it hard, if not impossible, to crystallize all possible conducts giving rise to a cultural clash amounting to crime in a given state. However, examples deriving from national case law and legislation have been collected by scholars and help identifying “categories” of crimes, which often are considered, especially in Western countries, as grounded in a cultural, or better said norm conflict. Some of them fall within existing offenses and have as a peculiarity the cultural “motivation” ( in concreto ) for the offender. Others, instead, have been formalized as new and specific offenses with the aim of recognizing the specificity of these crimes and their connection with a specific cultural tradition in order to provide better protection for victims.

Female Genital Mutilation

Certainly, the most problematic are crimes that involve women and children as victims and are usually referred to as “harmful traditional practices” (UN Women website). These practices have been the object of international documents and conventions aimed at the protection of women and children and have been introduced as specific offenses in the criminal codes of many countries. The most known is the crime of female genital mutilation (FGM), which includes clitoridectomy, excision, infibulation, and any other harmful procedure to female genitalia that is performed for non-medical purposes (World Health Organization, 2018 ). This ritual is practiced in many areas of Africa, the Middle East, and Asia and among immigrant communities in Europe and North America. It is usually performed on young girls (but sometimes also on adult women) and is deemed to ensure their virginity until marriage and her fidelity afterward. It becomes also a sign of cultural identity and a requirement for community membership (World Health Organization, 2018 ). This practice has formed the object of several international resolutions and recommendations and has been introduced in many national criminal codes as a specific offense. A similar discussion regarding the possibility of making male circumcision a crime was held in the last few years in some European countries. So far, no country has criminalized circumcision, which however remains punishable under provisions incriminating bodily harm. In certain countries, such as Germany, the willingness to shield certain (religious) groups from punishment has brought to the introduction of a justification for the practice of circumcision grounded on the right to parental care and custody and on freedom of religion.

Forced Marriage

Another practice, which has recently been at the center of national and international human rights strategies and has been criminalized by several countries as a specific offense is that of forced marriage . In certain countries, especially in rural areas, girls and boys (but also adult women) are forced to marry the partner their family has chosen for them and/or to remain married later on in life. This practice is closely linked to the idea of honor governing certain societies, but it is also influenced by economic reasons (such as the protection of family assets) and by issues related to migration (e.g., the preservation of the group in the diaspora or the facilitation of migration for other members of the family or the community) (Payton, 2015 ). Forced marriages can also be linked to other forms of violence perpetrated before the marriage by the parents (domestic violence, segregation, abduction, etc.), during the marriage by the husband (sexual and domestic violence) and also after the marriage in the event of a divorce, by the family of the wife or the husband (violence that can amount to killing).

Honor-Based Violence

Also connected to the idea of honor (and the related concept of shame) is so-called honor-based violence . Nowadays, cultures of honor are found in societies with tribal traditions, dominated by patrilineal, extended family clans (for example in South and Central Asia, Middle East, and North Africa) and in Western countries with high rates of immigrant population coming from these same societies (Oberwittler & Kasselt, 2014 ). In these patriarchal societies, the code of honor reproduces the status of a family or an entire group and relies largely on the sexuality of female family (or group) members. When the honor of a group is breached (or is perceived to have been breached) and shame is brought on that group, a reaction is needed in order to re-establish the status quo ante . A variety of crimes can be committed in the attempt to prevent or avenge a loss of honor. The most serious form of honor crime is homicide, so-called honor killing , usually perpetrated toward girls (rarely men) who are perceived to have brought shame on the family with their immoral behavior. In order to qualify as an honor killing, the murder should be premeditated and organized; it is seen as the result of a collective decision-making process that involves a “family council” in which the final decision is made and the details of the killing are specified (Honour-Based Violence Awareness Network). Another form of murder related to the idea of honor is the one perpetrated in the context of a blood feud . Blood feuds usually arise due to quarrels over land or over women and can last years or even decades. The killing of a member of the family of the “perpetrator” by the family of the “victim” triggers a spiral of violence fostered by revenge, which may result in the murder of several members of both families until an agreement is reached (Tellenbach, 2006 ). Other crimes, often committed in the name of honor and tradition, are, among others, sex-selective abortion , female infanticide , and forced abortion (for cases of pre-marital or extra-marital pregnancy). A different conception of honor, not necessarily linked to sexuality but more to moral integrity and respect, can be at the basis of other types of violence, including murder. This is the case of reactions to certain insults whose seriousness can only be understood by having a look at the cultural context in which they are exchanged (Basile, 2010 ).

Other Offenses

Other forms of killings are related to old superstitions. It is, for example, the case of witch killing and the killing of albinos , especially diffused in certain African regions or to rituals such as the Japanese oyaku shinju , parent-child suicide as a reaction to shame (Carstens, 2009 ; Renteln, 2004 ).

Overall, the majority of cases in which the cultural element is invoked by the defendant as a justification for his/her behavior are related to crimes perpetrated against family members. They consist of domestic violence , sexual violence , child abuse , and sometime amount to segregation or slavery . The justification brought forward by the accused is linked to a different conception of parental authority and the role of the pater familias , a different code of conduct for women, especially with regard to the relationship between men and women. Sometimes they concern the refusal of parents to send their children to school or to the use of minor children for begging or the extraction of social welfare (for example, in rom communities) or the refusal to authorize medical treatments (such as surgeries or blood transfusions). A variety of rituals linked to healing, superstition, and possession may also involve physical violence, scars (so-called scarification) and tattoos. In certain countries, marriage by capture is still practiced and involves the kidnapping and rape of the future wife (Basile, 2010 ; Renteln, 2004 ; Ruggiu, 2012 ).

Other offenses conflict with public order in Western societies. Among them are drug consumption (linked to religious or ritual ceremonies), traditional or religious attire (such as covering the face or wearing a weapon like the Sikh kirpan ), use of animals for certain ceremonies or their ritual slaughtering (prohibited in some countries), polygamy , and ritual burials (Renteln, 2004 ).

Cultural Differences in Criminal Law

The identification of the most common conflicts of norms is only a first step in the analysis of the relationship between culture and crime or, better said, between culture and the criminal justice system. Criminal law defines what behavior is deviant and what is not and has a value-imposing function. Criminal justice systems reflect principles and values shared by the dominant society and help orient the behavior of citizens (Durkheim, 1983 ). An important question to be answered pertains to the weight that cultures others than the dominant one is or should be given within criminal law and criminal proceedings. Is multicultural criminal justice desirable or should criminal justice authorities rely on a strict principle of formal equality and ignore any cultural considerations? And if cultural difference is taken into account, what could be a suitable instrument to do so?

The doctrinal debate has engaged both political philosophers and criminal lawyers who have brought reasons in support and against the use of culture within criminal proceedings. While political philosophers have mainly focused on the construction of the individual identity; on issues of socialization and agency; and on concepts such as equality, freedom, and justice in multicultural contexts, criminal lawyers have analyzed fundamental criminal law principles, paying attention to the ascription of responsibility, the assessment of blameworthiness, and to questions of punishment and just desert (Kymlicka, Lernestedt, & Matravers, 2014 ). The following paragraphs will try to recall the major arguments appearing in the mentioned debate and the different instruments used to bring culture in the criminal justice system, sometimes with the purpose of excluding punishment for members of minority groups, some others with the intent to extend punitivity.

Criminalization

A first way in which culture enters the criminal justice system is through choices of criminalization. Criminalization is necessarily based upon cultural assumptions and is used to avoid harm and ensure the respect of human rights and protect victims. Gender equality, protection of minors, as well as protection of public health and safety, are often at the basis of criminalization of behaviors that despite being detrimental to certain subjects are considered acceptable within certain groups, including the majority of a society (Kymlicka, Lernestedt, & Matravers, 2014 ). One example is represented by the evolution of legislations on sexual and domestic violence, which now criminalize behaviors considered “normal” by the majority of the society 50 or 60 years ago. Currently, at least in Western countries, the focus has shifted toward behaviors responding to traditional practices or customs considered expressions of different normative systems, contrary to international human rights standards and to the principles of liberal democracies. Typical examples of criminalization of “cultural” practices are recent legislations criminalizing forced and child marriages and female genital mutilation. The legislators of many countries have felt the need to expressly criminalize acts that would have fallen under more general categories of crimes (such has bodily harm, threat, coercion, etc.) to reinforce the disvalue attached to such behaviors, practiced by certain groups within their societies, and deny any room for pluralism in this area (see European Fundamental Rights Agency, 2014 ; Haenen, 2014 ; Thiara, Condon & Schröttle, 2011 ). While in the past, the discourse on cultural practices and their recognition within the criminal justice system was aimed at reducing punitivity for offenders coming from minority groups, 1 more recently the discussion moved in the opposite direction. Great importance in this sense is to be given to the Council of Europe convention on preventing and combating violence against women and domestic violence (hereinafter Istanbul Convention). The convention encourages states to take action to eliminate any form of violence against women, and in doing so it often stresses the need to eradicate “prejudices, customs, traditions and other practices which are based on the idea of the inferiority of women or on stereotyped roles for women and men” and to “ensure that culture, custom, religion, tradition or so-called ‘honour’ shall not be considered as justification for any acts of violence covered by the scope of this Convention” (Istanbul Convention, art. 12). The convention also encourages states to criminalize behaviors such as that of forcing somebody into a marriage (art. 37) and of coercing someone to undergo (or performing) female genital mutilation (art. 38). Article 42 of the convention underlines once again that “culture, custom, religion, tradition or so-called ‘honour’ shall not be regarded as justification for such acts. This covers, in particular, claims that the victim has transgressed cultural, religious, social or traditional norms or customs of appropriate behaviour.” It seems clear from the text that no room should be left for the appreciation of cultural practices with a decriminalizing or mitigating purpose.

Decriminalization and Exemptions

A second, and to some extent opposite, way through which culture can play a role within the criminal justice system is through decriminalization of certain behaviors or exemptions from criminal provisions for certain groups in order to allow them to perform their traditions and customs. In such a way, decriminalization of certain practices can be used to shield individuals from punishment and ensure the respect of their human rights. This has been the case for homosexuality, which has been decriminalized in Western Europe in the last few decades. Although this practice remains a crime in many areas of Africa and South East Asia, the respect of human rights imposes nowadays a complete decriminalization (see Johnson & Vanderbeck, 2014 ). A similar discourse has been made for polygamy, which is instead considered a crime in most of the Western world, although some claim for its decriminalization (for a discussion on this point, see Husak, 2014 ; Parekh, 2006 ). Partially different is the question of (women) adultery, which is still punished in several countries, especially Muslim ones, sometimes very severely. International organizations and NGOs working for the protection of women’s rights have repeatedly asked states to remove from their criminal codes provisions incriminating adultery (see UN Virtual Knowledge Centre to End Violence against Women and Girls).

Exemptions from criminal law provisions for minority groups have been discussed and sometimes granted in the name of freedom of religion and belief and in the name of tolerance. This is, for example, the case of indigenous peoples and other groups, such as Rastafarians, that in certain states are exempted from laws criminalizing the possession and consumption of narcotics (Kymlicka et al., 2014 ; Renteln, 2004 ). A similar decision, although on a different matter, has been taken by the German Parliament, which in 2012 passed a bill to decriminalize non-therapeutic male circumcision performed under certain circumstances on children (art. 1631 German Criminal Code), in order to shield parents of certain religious groups from the accuse of bodily injury.

Other Instruments That Diminish or Exclude Defendant’s Culpability

Another possible form of interaction between culture and criminal law concerns the way in which responsibility is ascribed and blameworthiness assessed. The idea of a just punishment necessarily involves evaluations of individual blameworthiness and implies a certain degree of agency in the subject to be punished (Kymlicka et al., 2014 ). So far, traditional criminal law instruments have been used by defendants (not always successfully) in order to see their cultural claims analyzed in courts and their responsibility reduced or eliminated.

Ignorance of the Law

A first argument that could be raised by defendants is ignorance of the law . A defendant might argue that when committing the crime, he/she was not aware of the existence of a criminal provision prohibiting that behavior, either because of his/her recent arrival in the country (often coupled with the absence of a similar provision in the country of origin) or because of his/her culture, which allows or even encourages such a behavior (Greenawalt, 2014 ). The general principle in criminal law is that “ignorance of the law is no excuse.” However, in order to comply with standards of due process and to fully respect the principle of individual responsibility, the principle has been mitigated, especially at the jurisprudential level, and exceptions are now admitted in cases where ignorance of the law is considered reasonably justified (Greenawalt, 2014 ; Renteln, 1992 –1993).

Mistake of Fact

A similar discourse can be made for mistake of fact , when the perception of reality, and therefore the mistake, is caused by the cultural background of the accused. A mistake negates the mens rea when the act would have been lawful if the facts were as the defendants supposed them to be (Sams, 1986 ). The mistake should be honest and the behavior should be a consequence of the mistake itself. In case of immigrant defendants, their belief and societal norms might be considered the cause for a mistake and therefore exclude responsibility (Sams, 1986 ).

Justifications

Justifications might be invoked in order to exclude responsibility of the offender. They preclude the existence of a criminal offense, even in the presence of both actus reus and mens rea . While the harm caused by the crime remains a legally recognized harm, under certain conditions, it is outweighed by the need to avoid a greater harm and is therefore justified (Robinson, 1982 ). This is the case, for example, in situations of necessity (in which a subject is forced to make a choice between two evils) and in situations in which the subject acts in self-defense , that is to say in response to an unlawful aggression. In such cases, the author is morally justified for the action committed. Cultural considerations have sometimes been used by defendants as a ground for justifications as they could affect the appreciation of what constitutes an evil or an unlawful aggression (Greenawalt, 2014 ; Renteln, 1992 –1993). However, given the exceptional and exculpatory character of justifications, broadening their scope on the basis of cultural considerations does not seem to be advisable.

Other typical instruments that might be grounded on cultural evidence are excuses. Excuses recognize the wrongfulness of the act but exclude, at least partially, the liability of the offender. They refer to the circumstances or conditions under which the accused has acted and which have influenced his/her conduct (Lacey, 2011 ). The application of criminal law and punishment presupposes the existence of an individual (the actor) with certain minimum capacities, both volitional and cognitive ones (Lacey, 2016 ). Volitional capacities (or conditions) refer to the ability of the offender to control his/her behavior and might be reduced in situations of fear, distress, or rage. Cognitive conditions, instead, refer to the capability of the offender to appreciate the wrongful character of his/her conduct and its consequences. Socialization can play a significant role in the way in which this appreciation takes place (Lacey, 2016 ). One example of excuse is provocation that in given circumstances is capable of reducing accuses of murder to manslaughter. Different systems have different rules to what concerns provocation, but usually the excuse applies when the author has committed the act under extreme emotional disturbance caused by somebody else’s unjust behavior. The question therefore becomes whether the loss of control of the actor can be understood as reasonable or not. Here cultural consideration might again play a significant role (Greenawalt, 2014 ; see also Amirthalingam, 2009 ; Sing, 1999 ).

A further possibility is to consider a defendant’s cultural arguments in the sentencing phase, either in the sense of mitigating or enhancing punishment. As already mentioned, international instruments such as the Istanbul Convention prevent states from granting mitigation of punishment on the basis of “culture, custom, religion, tradition or so-called honour” while some countries have considered enhancing punishment based on cultural arguments. In some cases, however, sentencing guidelines and judges’ discretion have been used to reduce punishment for offenders coming from minority groups, on the basis of the motivations brought forward by them 2 (Shein, 2007 ; Sikora, 2001 ; Woodman, 2009 ). On the one hand, this could allow the necessary flexibility required in a field that is hardly subject to generalization. On the other hand, however, giving judges high degrees of discretion would endanger equality of treatment and would leave considerations about the relevance of cultural traditions to personal evaluations (Greenawalt, 2014 ).

Specific rehabilitation programs, focused on the cultural influence experienced by the offender, might also be imposed in addition or as an alternative to ordinary punishment, such as those recommended to so-called Latino batterers in the United States. Restorative justice practices (see the next paragraphs) also make extensive use of alternative forms of punishment, often tailored to the need of the offender, the victim, and the affected community.

Formalization of an Autonomous Cultural Defense?

The previous paragraphs identified existing criminal law instruments that are or might be used in order to introduce culture in a criminal proceeding. In the last few decades, however, scholars have been discussing the possibility of introducing an autonomous defense based solely on culture. The discussion took place mainly in common low systems; and so far, no country has decided to introduce such an instrument. “A cultural defence is a defence asserted by immigrants, refugees and indigenous people based on their customs or customary law. A successful cultural defence would permit the reduction (and possible elimination) of a charge with a concomitant reduction in punishment” (Renteln, 1992 –1993). This autonomous, general defense would create an exception for certain defendants who could see their culpability diminished (if not excluded) based on their cultural traditions. However, a lot of questions would be raised in case such a defense had to be introduced. First, it is not clear who would be entitled to raise the defense (Greenawalt, 2014 ; Sams, 1986 ). Second, one could wonder why such a defense should be allowed for culture and not for other relevant factors or background conditions that have a similar impact on the life of individuals, such as socioeconomic conditions, abusive parents, violent neighborhood, and so on (Greenawalt, 2014 ; Lacey, 2011 , 2016 ).

The debate on the opportunity of introducing a cultural defense involved both policy and legal arguments. The following paragraphs will retrace the main arguments in support and against the formalization of such an instrument.

Arguments in Support of the Cultural Defense

Those who support the formalization of a cultural defense see it as an expression of the principles of individualized justice and cultural pluralism. In cases in which the offender acted without fully comprehending the disvalue of his/her conduct or did so in adherence to fundamental cultural values conflicting with the criminal norms of the dominant society, this element should not be underestimated in the evaluation of his/her degree of culpability (Anonymous, 1986 ). Moreover, by judging everyone according to the standards of his/her native culture, cultural diversity would be preserved and the principle of equality among ethnic groups fulfilled (Wong, 1999 ).

Supporters of the cultural defense rely on the theory of enculturation to stress the importance that cultural values have in shaping people’s personality and in orientating (even subconsciously) human behavior. Alison Dundes Renteln argues for the recognition of a cultural defense as a partial excuse. According to the author, a partial excuse would allow the accommodation of the motivation of the defendant and his/her degree of culpability, without requiring an acquittal or, on the contrary, excessive punishment. In order to allow some flexibility but at the same time guide judges and prevent abuses, Renteln formulates a test that should help in the application of the defense. The test should rely on the testimony of an expert and consists of three questions: (1) Is the litigant a member of the ethnic group? (2) Does the group have such a tradition? (3) Was the litigant influenced by the tradition when he or she acted? (Renteln, 2004 ). A longer and more elaborated test was proposed by Ilenia Ruggiu in 2012 . This second test encompasses 12 passages and deals with objective, subjective, and relational aspects. The following questions need to be answered: (1) Is it possible to define the practice as cultural? (2) What description of the cultural practice and the group that adopts it should be given? (3) Should the practice be placed within the bigger cultural (normative) system of the group? (4) Is the practice essential and mandatory within this system? (5) Is the practice undisputed or do discussions and criticism exist? (6) Is the group discriminated against within the society? (7) How would have the “reasonable cultural person” (a member of the same group) reacted? (8) How honest is the subject? (9) Does one need to find a practice in the dominant culture that has a similar meaning for a member of that culture (a “cultural equivalent”)? (10) Does the practice involve harm? (11) What is the impact of the practice on the dominant culture? (12) What are the reasons brought by the defendant that explain why the practice should be maintained? (Ruggiu, 2012 ).

The test proposed by Ruggiu touches upon many of the problematic issues related to the introduction of a formal cultural defense in the criminal justice system. These same issues are often raised by opponents of this instrument to show the risks and disadvantages of the formalization of a specific defense related to culture.

Arguments Against the Cultural Defence

Arguments against the formalization of a cultural defense relate mainly to three aspects: the problematic definition of the concept of culture, the consequences in terms of gender and power imbalances, and the impact of the defense on core legal principles.

To what concerns the first aspect, according to opponents of the cultural defense, culture is a fluid and evolving concept, and any attempt to define it under standardized criteria brings with it the risk of essentialism. Even through the use of experts in courts, it would be impossible to get a comprehensive idea of a cultural group and its practices and to create a rule flexible enough to be applied to a variety of cases. Describing a culture through its most problematic practices risks creating divisions between the dominant society and the minority group, promoting “othering” and stereotypes. Rather than offering minorities a more equal solution, the defense might create a differential set of rules along ethnic lines and contribute to the revival of old racist and exclusionary discourses (Chiu, 1994 ; Coleman, 1996 ; Fournier, 2002 ; Karayanni, 2009 ; Volpp, 1996 ; Wong, 1999 ).

A second argument used against the recognition of a specific defense is the alleged incompatibility between multiculturalism and women’s rights. The majority of feminist movements challenge the idea that multicultural policies provide better freedom and security for all members of a group. In their view, a strong tension exists between feminism and multiculturalism, as multicultural policies (including the cultural defense) tend to overlook the differences existing within groups and the gender and power imbalances, which play a role in the communitarian dimension. Cultures (and religions) in history have favored the control of women by men, through practices such as female genital mutilations, forced marriages, and polygamy. Granting these groups specific rights in the name of culture means reinforcing patriarchal traditions. (Chiu, 1994 ; Okin, 1997 ; Phillips, 2003 ; Volpp, 2001 ). In this direction moved the above-mentioned Istanbul Convention that forbids states to take into account culture and tradition as a ground for reduction of punishment.

A third category of criticism relates to some core principles of criminal justice systems that could be endangered by the recognition of such an instrument. The first one is the principle of equality (and non-discrimination). Allowing a special treatment for certain “categories” of subjects would open the way for a multitude of claims for differential regimes and undermine the uniformity and stability of the criminal justice system and the maintenance of social order. Besides this, both general and specific deterrence would be weakened as well as the normative function of criminal law. As it would be impossible to foresee all possible cases to which the cultural defense could be applied (including behaviors, ethnic or religious groups, individuals, etc.) the principle of legal certainty, a core element of the rule of law, would also be infringed (Bernardi, 2006 ; Coleman, 1996 ). Moreover, according to its opponents, the cultural defense clashes with another founding principle of most Western criminal justice systems, that of individual responsibility. Considering culture as the primary motive of action, the responsibility would inevitably shift from the offender to the culture, or more specifically to the tradition or custom at stake. According to some scholars, therefore, the role assigned to culture would be too big and would obfuscate other conditions and circumstances that also had an impact on the offender’s conduct (Chiu, 1994 ; Wong, 1999 ). Related to this last point is the accusation that a cultural defense would portray members of minority cultures as lacking autonomy. The determinist understanding of culture, which often pervades the debate about accommodation of minorities, represents individuals coming from minority groups as entirely controlled by cultural norms, incapable of making independent choices and of exiting the group (Phillips, 2007 ).

At the moment, the formalization of a cultural defense seems unlikely. Although cultural evidence is sometimes taken into account by judges through existing defenses, international human rights instruments are clearly discouraging states to recognize culture, religion, and tradition as a justification for crime, at least when harm (and vulnerable subjects such as women and children) is involved.

As suggested by Nicola Lacey, the overall debate on the cultural defense should probably be placed within a broader discussion on the scope and role of criminal law, its normative character, and the goals of criminalization ( 2011 ).

Alternative Dispute Resolution and Restorative Justice

The considerations made so far concerned the place for cultural differences within the criminal justice system. There are, however, ways of dealing with such differences outside the formal system. For the purpose of this article, it is worth mentioning the importance acquired in the last few decades by alternative dispute resolution mechanisms (ADR) and in particular by the restorative justice (RJ) movement (Braithwaite, 2003 ; Christie, 1977 ). Often, it is not only the criminalization of certain behaviors that clashes with specific cultures or traditions but also the procedures used to assess a person’s guilt. ADR and, more specifically for criminal cases, RJ mechanisms are sometimes used to allow room for discussion and appreciation of cultural practices and to deliver justice in a more culturally sensitive way (Williams, 2002 ). These mechanisms can be linked to the formal justice system (which can refer cases to external RJ agencies) or act independently from it (as the example of community-based organizations or leaders).

Restorative Justice Mechanisms

The diffusion of ADR in the Western world began between the 1960s and the 1970s with the aim of reducing the costs and the duration of legal proceedings. Some features clearly distinguish Western dispute resolution from a traditional, indigenous one. In particular, professionalism is at the center of this new trend, and specific knowledge is required in order to perform the role of mediator or arbitrator. Moreover Western countries have tried to partially incorporate ADR within the framework of the formal justice system with the aim of extending a state’s control over them (Abu-Nimer, 2001 ; Singer, 1990 ). While ADR such as arbitration and negotiation are mainly used for civil and commercial issues, restorative justice, and in particular mediation, is suitable to solve criminal disputes. RJ has been described as “a process whereby parties with a stake in a specific offence collectively resolve how to deal with the aftermath of the offence and its implications for the future” (Marshall, 1999 ). The appearance of restorative justice in Western contemporary debate dates back to the publication, in 1997 , of the article “Conflicts as Property” by the Norwegian criminologist Nils Christie, in which he criticizes the predominant role of the State within criminal proceedings and he claims the need “to return[s] conflicts to their rightful owners,” that is to say, the victim, the offender, and the community affected by the crime (Christie, 1977 ). Restorative justice originates from the practices of indigenous communities in Canada, Australia, and New Zealand. It refuses a strictly retributive conception of punishment, and it focuses instead on the reparation of the harm done by the crime often through the compensation of the victim (and sometimes of the community) and the reintegration of the offender in the community (so-called reintegrative shaming) (Braithwaite, 1989 ). RJ models are mainly three: victim-offender-mediation; family-group-conferencing; and peacemaking (or sentencing) circles. All programs bring together the offender and the victim of a crime and a third, neutral person, while the two latter involve a larger circle of people somehow connected to the parties or affected by the crime. Sometimes representatives of the state are involved. All the mentioned mechanisms allow a great deal of dialogue among participants and a discussion among values and principles relevant for the parties and for the community involved and some degree of flexibility to what concerns the solutions to be adopted in order to punish the offender and repair the harm done by the crime. Often a plurality of normativities, including state law, religious; and cultural norms, play a role in understanding and resolving a dispute.

Community Alternative Dispute Resolution

The diffusion of ADR within immigrant communities in Europe is often looked at with skepticism. These forms of private or informal justice usually make use of mediation or arbitration procedures relying on customary or religious norms.

Particularly debated is the role of the Muslim Arbitration Tribunal and Sharia Councils in the United Kingdom. The Muslim Arbitration Tribunal (MAT) is recognized under the Arbitration Act ( 1996 ) and provides services in the area of family disputes and divorce, commercial and civil arbitration, and inheritance, arbitrating on the basis of Sharia law. In 2008 , it launched an initiative on forced marriages, a practice that was criminalized in 2014 (MAT website). The tribunal has also been accused of dealing with situations of domestic and family violence through the practice of arbitration, failing to report cases to the police. Similar accusations have been directed toward Islamic Sharia Councils, established in the United Kingdom to advise Muslims on issues of personal and family law. Once again, criticism has been raised with regard to the procedures followed and cases heard within the councils. Religious leaders operating within these bodies are accused of pressuring female victims of violence to reconcile with the perpetrators (often the husbands) of threatening them and deterring them from reporting crimes to the police (MacEoin & Green, 2009 ; One Law for All Report, 2010 ; Zee, 2016 ).

In Germany, a similar discussion is currently going on with regard to certain migrant groups (Turkish, Kurdish, Lebanese, etc.) that tend to solve their internal conflicts without recurring to the formal criminal justice system (so-called Paralleljustiz) (Rohe & Jaraba, 2015 ). Imams or other well-respected persons within the community are addressed when disputes related to family, marriage, personal status, honor, and other forms of violence occur. As for criminal cases, the resolution of the dispute sees the involvement of a third person (the mediator or arbitrator) and the families of the victim and offender. Common meetings might take place and compensation from the perpetrator to the victim is prescribed. Traditional, customary, and religious norms might play a role in the resolution of the dispute. In such cases, the participation of formal justice institutions becomes unnecessary or, in certain cases, even counterproductive and victims and witnesses are forced (or spontaneously decide) to withdraw their declarations (Rottleuthner, 2012 ; Wagner, 2011 ).

Despite the fact that most criminal offenses are not reported to the police, such a privatization of criminal law is seen by many as a threat to the state’s monopoly over the use of force. Moreover, it raises questions about the respect of both victims’ and offenders’ substantive and procedural rights in the resolution of the dispute. Besides these critical positions there are, however, those who see an important function carried out by these mediators or arbitrators, such as breaking the circle of violence in situations of revenge and retaliatory action (e.g., blood feuds) between clans and facilitating access to justice for certain members of the community whose needs are not addressed by the formal justice system (Rottleuthner, 2014 ).

In lack of a criminal justice system capable of addressing the needs of victims and defendants coming from minority groups, community dispute resolution mechanisms represent a possible alternative for them. The risks presented above exist also with regard to these programs. State authorities should be able to make use of the expertise existing within communities and cooperate with community bodies in order to ensure the respect of human rights while allowing a certain degree of pluralism and facilitating access to justice for all.

Further Reading

- Addo, M. K. (2010). Practice of United Nations human rights treaty bodies in the reconciliation of cultural diversity with universal respect for human rights. Human Rights Quarterly , 32 (3), 601–664.

- Albrecht, H.-J. (1997). Ethnic minorities, crime, and criminal justice in Germany. Crime and Justice , 21 , 31–99.

- Bovenkerk, F. (1993). Crime and the multi-ethnic society: A view from Europe. Crime, Law and Social Change , 19 , 271–280.

- Bovenkerk, F. , & Yesilgoz, Y. (2004). Crime, ethnicity and the multicultural administration of justice. In J. Ferrell , K. Hayward , W. Morrison , & M. Presdee (Eds.), Cultural criminology unleashed (pp. 81–96). London, UK: Glasshouse.

- Chiu, E. M. (2006). Culture as justification, not excuse. American Criminal Law Review , 43 , 1–79.

- Foblets, M.-C. (2013). Accommodating Islamic family law(s). A critical analysis of some recent developments and experiments in Europe. In M. S. Berger (Ed.), Applying Shariʻa in the West. Facts, fears and the future of Islamic rules on family relations in the West (pp. 207–226). Leiden, The Netherlands: Leiden University Press.

- Huntington, S. P. (1993). The clash of civilizations? Foreign Affairs , 72 (3), 22–49.

- Kymlicka, W. (1995). Multicultural citizenship: A liberal theory of minority rights . Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Maguigan, H. (1995). Cultural evidence and male violence: Are feminist and multiculturalist reformers on a collision course in criminal courts? New York University Law Review , 36 , 36–99.

- Merton, R. (1938). Social structure and anomie. American Sociological Review , 3 (5), 672–682.

- Abu-Nimer, M. (2001). Reconciliation, justice and coexistence: Theory and practice . Lanham, MD: Lexington Books.

- Adler, F. , Mueller, G. O. W. , & Laufer, W. S. (2013). Criminology . New York, NY: McGraw Hill.

- Algan, Y. , Bisin, A. , & Verdier, T. (2012). Introduction: Perspectives on cultural integration of immigrants. In Y. Algan , A. Bisin , A. Manning , & T. Verdier (Eds.), Cultural integration of immigrants in Europe (pp. 1–48). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Amirthalingam, K. (2009). Culture, crime, and culpability: Perspectives on the defence of provocation. In M.-C. Foblets & A. D. Renteln (Eds.), Multicultural jurisprudence. Comparative perspectives on the cultural defense (pp. 35–60). Portland, OR: Hart.

- Anonymous (1986). The cultural defense in the criminal law. Harvard Law Review , 99 , 1293–1311.

- Anthony, T. (2013). Indigenous people, crime and punishment . New York, NY: Routledge.

- Basile, F. (2010). Immigrazione e reati culturalmente motivati . Il diritto Ppnale nelle società multiculturali . Milano, Italy: Griuffré Editore.

- Benhabib, S. (2002). The claims of culture. Equality and diversity in the global era . Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Bernardi, A. (2006). Modelli penali e società multiculturale . Torino, Italy: Giappichelli Editore.

- Bourdieu, P. (1977). Outline of a theory of practice . Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.