- Science Notes Posts

- Contact Science Notes

- Todd Helmenstine Biography

- Anne Helmenstine Biography

- Free Printable Periodic Tables (PDF and PNG)

- Periodic Table Wallpapers

- Interactive Periodic Table

- Periodic Table Posters

- How to Grow Crystals

- Chemistry Projects

- Fire and Flames Projects

- Holiday Science

- Chemistry Problems With Answers

- Physics Problems

- Unit Conversion Example Problems

- Chemistry Worksheets

- Biology Worksheets

- Periodic Table Worksheets

- Physical Science Worksheets

- Science Lab Worksheets

- My Amazon Books

Understanding Peer Review in Science

Peer review is an essential element of the scientific publishing process that helps ensure that research articles are evaluated, critiqued, and improved before release into the academic community. Take a look at the significance of peer review in scientific publications, the typical steps of the process, and and how to approach peer review if you are asked to assess a manuscript.

What Is Peer Review?

Peer review is the evaluation of work by peers, who are people with comparable experience and competency. Peers assess each others’ work in educational settings, in professional settings, and in the publishing world. The goal of peer review is improving quality, defining and maintaining standards, and helping people learn from one another.

In the context of scientific publication, peer review helps editors determine which submissions merit publication and improves the quality of manuscripts prior to their final release.

Types of Peer Review for Manuscripts

There are three main types of peer review:

- Single-blind review: The reviewers know the identities of the authors, but the authors do not know the identities of the reviewers.

- Double-blind review: Both the authors and reviewers remain anonymous to each other.

- Open peer review: The identities of both the authors and reviewers are disclosed, promoting transparency and collaboration.

There are advantages and disadvantages of each method. Anonymous reviews reduce bias but reduce collaboration, while open reviews are more transparent, but increase bias.

Key Elements of Peer Review

Proper selection of a peer group improves the outcome of the process:

- Expertise : Reviewers should possess adequate knowledge and experience in the relevant field to provide constructive feedback.

- Objectivity : Reviewers assess the manuscript impartially and without personal bias.

- Confidentiality : The peer review process maintains confidentiality to protect intellectual property and encourage honest feedback.

- Timeliness : Reviewers provide feedback within a reasonable timeframe to ensure timely publication.

Steps of the Peer Review Process

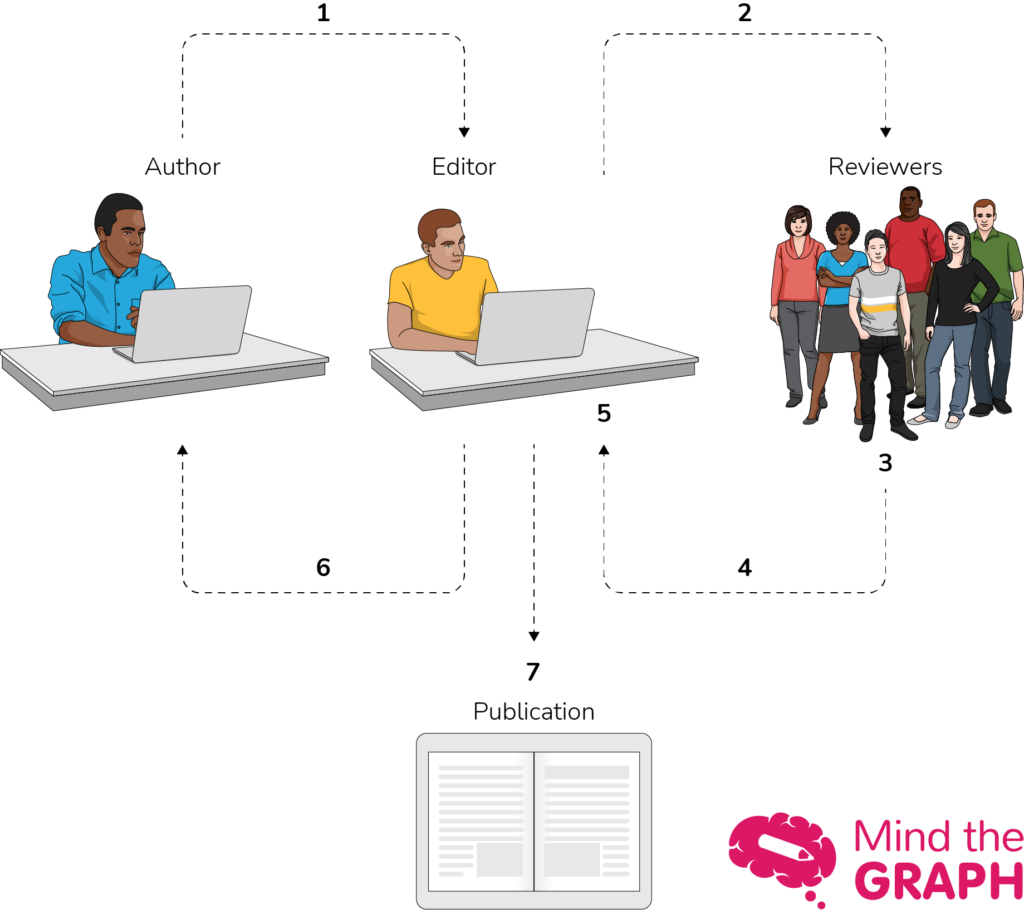

The typical peer review process for scientific publications involves the following steps:

- Submission : Authors submit their manuscript to a journal that aligns with their research topic.

- Editorial assessment : The journal editor examines the manuscript and determines whether or not it is suitable for publication. If it is not, the manuscript is rejected.

- Peer review : If it is suitable, the editor sends the article to peer reviewers who are experts in the relevant field.

- Reviewer feedback : Reviewers provide feedback, critique, and suggestions for improvement.

- Revision and resubmission : Authors address the feedback and make necessary revisions before resubmitting the manuscript.

- Final decision : The editor makes a final decision on whether to accept or reject the manuscript based on the revised version and reviewer comments.

- Publication : If accepted, the manuscript undergoes copyediting and formatting before being published in the journal.

Pros and Cons

While the goal of peer review is improving the quality of published research, the process isn’t without its drawbacks.

- Quality assurance : Peer review helps ensure the quality and reliability of published research.

- Error detection : The process identifies errors and flaws that the authors may have overlooked.

- Credibility : The scientific community generally considers peer-reviewed articles to be more credible.

- Professional development : Reviewers can learn from the work of others and enhance their own knowledge and understanding.

- Time-consuming : The peer review process can be lengthy, delaying the publication of potentially valuable research.

- Bias : Personal biases of reviews impact their evaluation of the manuscript.

- Inconsistency : Different reviewers may provide conflicting feedback, making it challenging for authors to address all concerns.

- Limited effectiveness : Peer review does not always detect significant errors or misconduct.

- Poaching : Some reviewers take an idea from a submission and gain publication before the authors of the original research.

Steps for Conducting Peer Review of an Article

Generally, an editor provides guidance when you are asked to provide peer review of a manuscript. Here are typical steps of the process.

- Accept the right assignment: Accept invitations to review articles that align with your area of expertise to ensure you can provide well-informed feedback.

- Manage your time: Allocate sufficient time to thoroughly read and evaluate the manuscript, while adhering to the journal’s deadline for providing feedback.

- Read the manuscript multiple times: First, read the manuscript for an overall understanding of the research. Then, read it more closely to assess the details, methodology, results, and conclusions.

- Evaluate the structure and organization: Check if the manuscript follows the journal’s guidelines and is structured logically, with clear headings, subheadings, and a coherent flow of information.

- Assess the quality of the research: Evaluate the research question, study design, methodology, data collection, analysis, and interpretation. Consider whether the methods are appropriate, the results are valid, and the conclusions are supported by the data.

- Examine the originality and relevance: Determine if the research offers new insights, builds on existing knowledge, and is relevant to the field.

- Check for clarity and consistency: Review the manuscript for clarity of writing, consistent terminology, and proper formatting of figures, tables, and references.

- Identify ethical issues: Look for potential ethical concerns, such as plagiarism, data fabrication, or conflicts of interest.

- Provide constructive feedback: Offer specific, actionable, and objective suggestions for improvement, highlighting both the strengths and weaknesses of the manuscript. Don’t be mean.

- Organize your review: Structure your review with an overview of your evaluation, followed by detailed comments and suggestions organized by section (e.g., introduction, methods, results, discussion, and conclusion).

- Be professional and respectful: Maintain a respectful tone in your feedback, avoiding personal criticism or derogatory language.

- Proofread your review: Before submitting your review, proofread it for typos, grammar, and clarity.

- Couzin-Frankel J (September 2013). “Biomedical publishing. Secretive and subjective, peer review proves resistant to study”. Science . 341 (6152): 1331. doi: 10.1126/science.341.6152.1331

- Lee, Carole J.; Sugimoto, Cassidy R.; Zhang, Guo; Cronin, Blaise (2013). “Bias in peer review”. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology. 64 (1): 2–17. doi: 10.1002/asi.22784

- Slavov, Nikolai (2015). “Making the most of peer review”. eLife . 4: e12708. doi: 10.7554/eLife.12708

- Spier, Ray (2002). “The history of the peer-review process”. Trends in Biotechnology . 20 (8): 357–8. doi: 10.1016/S0167-7799(02)01985-6

- Squazzoni, Flaminio; Brezis, Elise; Marušić, Ana (2017). “Scientometrics of peer review”. Scientometrics . 113 (1): 501–502. doi: 10.1007/s11192-017-2518-4

Related Posts

- Technical Support

- Find My Rep

You are here

What is peer review.

Peer review is ‘a process where scientists (“peers”) evaluate the quality of other scientists’ work. By doing this, they aim to ensure the work is rigorous, coherent, uses past research and adds to what we already know.’ You can learn more in this explainer from the Social Science Space.

Peer review brings academic research to publication in the following ways:

- Evaluation – Peer review is an effective form of research evaluation to help select the highest quality articles for publication.

- Integrity – Peer review ensures the integrity of the publishing process and the scholarly record. Reviewers are independent of journal publications and the research being conducted.

- Quality – The filtering process and revision advice improve the quality of the final research article as well as offering the author new insights into their research methods and the results that they have compiled. Peer review gives authors access to the opinions of experts in the field who can provide support and insight.

Types of peer review

- Single-anonymized – the name of the reviewer is hidden from the author.

- Double-anonymized – names are hidden from both reviewers and the authors.

- Triple-anonymized – names are hidden from authors, reviewers, and the editor.

- Open peer review comes in many forms . At Sage we offer a form of open peer review on some journals via our Transparent Peer Review program , whereby the reviews are published alongside the article. The names of the reviewers may also be published, depending on the reviewers’ preference.

- Post publication peer review can offer useful interaction and a discussion forum for the research community. This form of peer review is not usual or appropriate in all fields.

To learn more about the different types of peer review, see page 14 of ‘ The Nuts and Bolts of Peer Review ’ from Sense about Science.

Please double check the manuscript submission guidelines of the journal you are reviewing in order to ensure that you understand the method of peer review being used.

- Journal Author Gateway

- Journal Editor Gateway

- Transparent Peer Review

- How to Review Articles

- Using Sage Track

- Peer Review Ethics

- Resources for Reviewers

- Reviewer Rewards

- Ethics & Responsibility

- Sage Editorial Policies

- Publication Ethics Policies

- Sage Chinese Author Gateway 中国作者资源

- Open Resources & Current Initiatives

- Discipline Hubs

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- 16 April 2024

Structure peer review to make it more robust

- Mario Malički 0

Mario Malički is associate director of the Stanford Program on Research Rigor and Reproducibility (SPORR) and co-editor-in-chief of the Research Integrity and Peer Review journal.

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

You have full access to this article via your institution.

In February, I received two peer-review reports for a manuscript I’d submitted to a journal. One report contained 3 comments, the other 11. Apart from one point, all the feedback was different. It focused on expanding the discussion and some methodological details — there were no remarks about the study’s objectives, analyses or limitations.

My co-authors and I duly replied, working under two assumptions that are common in scholarly publishing: first, that anything the reviewers didn’t comment on they had found acceptable for publication; second, that they had the expertise to assess all aspects of our manuscript. But, as history has shown, those assumptions are not always accurate (see Lancet 396 , 1056; 2020 ). And through the cracks, inaccurate, sloppy and falsified research can slip.

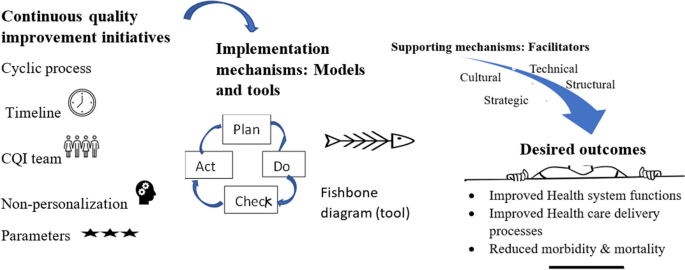

As co-editor-in-chief of the journal Research Integrity and Peer Review (an open-access journal published by BMC, which is part of Springer Nature), I’m invested in ensuring that the scholarly peer-review system is as trustworthy as possible. And I think that to be robust, peer review needs to be more structured. By that, I mean that journals should provide reviewers with a transparent set of questions to answer that focus on methodological, analytical and interpretative aspects of a paper.

For example, editors might ask peer reviewers to consider whether the methods are described in sufficient detail to allow another researcher to reproduce the work, whether extra statistical analyses are needed, and whether the authors’ interpretation of the results is supported by the data and the study methods. Should a reviewer find anything unsatisfactory, they should provide constructive criticism to the authors. And if reviewers lack the expertise to assess any part of the manuscript, they should be asked to declare this.

Anonymizing peer review makes the process more just

Other aspects of a study, such as novelty, potential impact, language and formatting, should be handled by editors, journal staff or even machines, reducing the workload for reviewers.

The list of questions reviewers will be asked should be published on the journal’s website, allowing authors to prepare their manuscripts with this process in mind. And, as others have argued before, review reports should be published in full. This would allow readers to judge for themselves how a paper was assessed, and would enable researchers to study peer-review practices.

To see how this works in practice, since 2022 I’ve been working with the publisher Elsevier on a pilot study of structured peer review in 23 of its journals, covering the health, life, physical and social sciences. The preliminary results indicate that, when guided by the same questions, reviewers made the same initial recommendation about whether to accept, revise or reject a paper 41% of the time, compared with 31% before these journals implemented structured peer review. Moreover, reviewers’ comments were in agreement about specific parts of a manuscript up to 72% of the time ( M. Malički and B. Mehmani Preprint at bioRxiv https://doi.org/mrdv; 2024 ). In my opinion, reaching such agreement is important for science, which proceeds mainly through consensus.

Stop the peer-review treadmill. I want to get off

I invite editors and publishers to follow in our footsteps and experiment with structured peer reviews. Anyone can trial our template questions (see go.nature.com/4ab2ppc ), or tailor them to suit specific fields or study types. For instance, mathematics journals might also ask whether referees agree with the logic or completeness of a proof. Some journals might ask reviewers if they have checked the raw data or the study code. Publications that employ editors who are less embedded in the research they handle than are academics might need to include questions about a paper’s novelty or impact.

Scientists can also use these questions, either as a checklist when writing papers or when they are reviewing for journals that don’t apply structured peer review.

Some journals — including Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences , the PLOS family of journals, F1000 journals and some Springer Nature journals — already have their own sets of structured questions for peer reviewers. But, in general, these journals do not disclose the questions they ask, and do not make their questions consistent. This means that core peer-review checks are still not standardized, and reviewers are tasked with different questions when working for different journals.

Some might argue that, because different journals have different thresholds for publication, they should adhere to different standards of quality control. I disagree. Not every study is groundbreaking, but scientists should view quality control of the scientific literature in the same way as quality control in other sectors: as a way to ensure that a product is safe for use by the public. People should be able to see what types of check were done, and when, before an aeroplane was approved as safe for flying. We should apply the same rigour to scientific research.

Ultimately, I hope for a future in which all journals use the same core set of questions for specific study types and make all of their review reports public. I fear that a lack of standard practice in this area is delaying the progress of science.

Nature 628 , 476 (2024)

doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-024-01101-9

Reprints and permissions

Competing Interests

M.M. is co-editor-in-chief of the Research Integrity and Peer Review journal that publishes signed peer review reports alongside published articles. He is also the chair of the European Association of Science Editors Peer Review Committee.

Related Articles

- Scientific community

- Peer review

Londoners see what a scientist looks like up close in 50 photographs

Career News 18 APR 24

Researchers want a ‘nutrition label’ for academic-paper facts

Nature Index 17 APR 24

Deadly diseases and inflatable suits: how I found my niche in virology research

Spotlight 17 APR 24

Is ChatGPT corrupting peer review? Telltale words hint at AI use

News 10 APR 24

Three ways ChatGPT helps me in my academic writing

Career Column 08 APR 24

Is AI ready to mass-produce lay summaries of research articles?

Nature Index 20 MAR 24

Postdoctoral Position

We are seeking highly motivated and skilled candidates for postdoctoral fellow positions

Boston, Massachusetts (US)

Boston Children's Hospital (BCH)

Qiushi Chair Professor

Distinguished scholars with notable achievements and extensive international influence.

Hangzhou, Zhejiang, China

Zhejiang University

ZJU 100 Young Professor

Promising young scholars who can independently establish and develop a research direction.

Head of the Thrust of Robotics and Autonomous Systems

Reporting to the Dean of Systems Hub, the Head of ROAS is an executive assuming overall responsibility for the academic, student, human resources...

Guangzhou, Guangdong, China

The Hong Kong University of Science and Technology (Guangzhou)

Head of Biology, Bio-island

Head of Biology to lead the discovery biology group.

BeiGene Ltd.

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

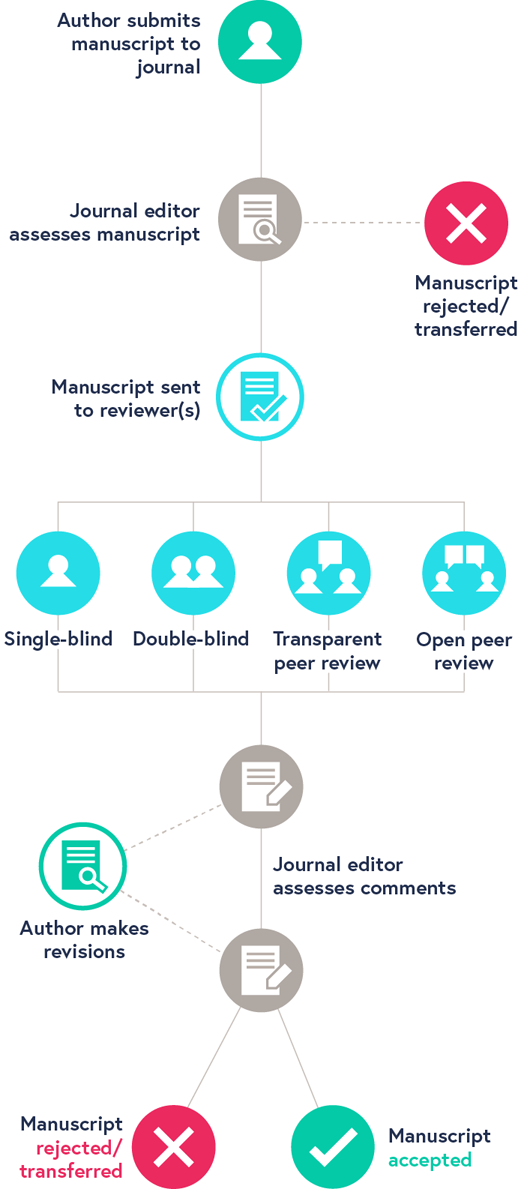

Peer review process

Introduction to peer review, what is peer review.

Peer review is the system used to assess the quality of a manuscript before it is published. Independent researchers in the relevant research area assess submitted manuscripts for originality, validity and significance to help editors determine whether a manuscript should be published in their journal.

How does it work?

When a manuscript is submitted to a journal, it is assessed to see if it meets the criteria for submission. If it does, the editorial team will select potential peer reviewers within the field of research to peer-review the manuscript and make recommendations.

There are four main types of peer review used by BMC:

Single-blind: the reviewers know the names of the authors, but the authors do not know who reviewed their manuscript unless the reviewer chooses to sign their report.

Double-blind: the reviewers do not know the names of the authors, and the authors do not know who reviewed their manuscript.

Open peer: authors know who the reviewers are, and the reviewers know who the authors are. If the manuscript is accepted, the named reviewer reports are published alongside the article and the authors’ response to the reviewer.

Transparent peer: the reviewers know the names of the authors, but the authors do not know who reviewed their manuscript unless the reviewer chooses to sign their report. If the manuscript is accepted, the anonymous reviewer reports are published alongside the article and the authors’ response to the reviewer.

Different journals use different types of peer review. You can find out which peer-review system is used by a particular journal in the journal’s ‘About’ page.

Why do peer review?

Peer review is an integral part of scientific publishing that confirms the validity of the manuscript. Peer reviewers are experts who volunteer their time to help improve the manuscripts they review. By undergoing peer review, manuscripts should become:

More robust - peer reviewers may point out gaps in a paper that require more explanation or additional experiments.

Easier to read - if parts of your paper are difficult to understand, reviewers can suggest changes.

More useful - peer reviewers also consider the importance of your paper to others in your field.

For more information and advice on how to get published, please see our blog series here .

How peer review works

The peer review process can be single-blind, double-blind, open or transparent.

You can find out which peer review system is used by a particular journal in the journal's 'About' page.

N. B. This diagram is a representation of the peer review process, and should not be taken as the definitive approach used by every journal.

The peer review process

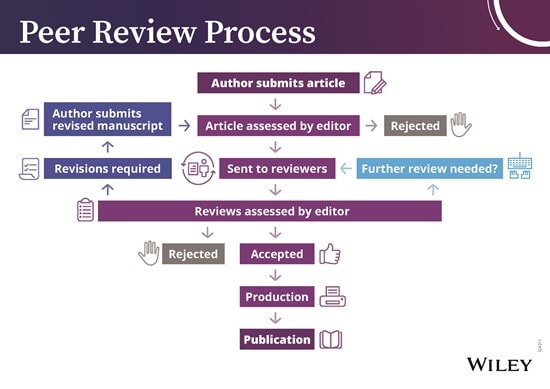

The peer review process can be broadly summarized into 10 steps, although these steps can vary slightly between journals. Explore what’s involved, below.

Editor Feedback: “Reviewers should remember that they are representing the readers of the journal. Will the readers of this particular journal find this informative and useful?”

1. Submission of Paper

The corresponding or submitting author submits the paper to the journal. This is usually via an online system such as ScholarOne Manuscripts. Occasionally, journals may accept submissions by email.

2. Editorial Office Assessment

The Editorial Office checks that the paper adheres to the requirements described in the journal’s Author Guidelines. The quality of the paper is not assessed at this point.

3. Appraisal by the Editor-in-Chief (EIC)

The EIC checks assesses the paper, considering its scope, originality and merits. The EiC may reject the paper at this stage.

4. EIC Assigns an Associate Editor (AE)

Some journals have Associate Editors ( or equivalent ) who handle the peer review. If they do, they would be assigned at this stage.

5. Invitation to Reviewers

The handling editor sends invitations to individuals he or she believes would be appropriate reviewers. As responses are received, further invitations are issued, if necessary, until the required number of reviewers is secured– commonly this is 2, but there is some variation between journals.

6. Response to Invitations

Potential reviewers consider the invitation against their own expertise, conflicts of interest and availability. They then accept or decline the invitation to review. If possible, when declining, they might also suggest alternative reviewers.

7. Review is Conducted

The reviewer sets time aside to read the paper several times. The first read is used to form an initial impression of the work. If major problems are found at this stage, the reviewer may feel comfortable rejecting the paper without further work. Otherwise, they will read the paper several more times, taking notes to build a detailed point-by-point review. The review is then submitted to the journal, with the reviewer’s recommendation (e.g. to revise, accept or reject the paper).

8. Journal Evaluates the Reviews

The handling editor considers all the returned reviews before making a decision. If the reviews differ widely, the editor may invite an additional reviewer so as to get an extra opinion before making a decision.

9. The Decision is Communicated

The editor sends a decision email to the author including any relevant reviewer comments. Comments will be anonymous if the journal follows a single-anonymous or double-anonymous peer review model. Journals with following an open or transparent peer review model will share the identities of the reviewers with the author(s).

10. Next Steps

An editor's perspective.

Listen to a podcast from Roger Watson, Editor-in-Chief of Journal of Advanced Nursing, as he discusses 'The peer review process'.

If accepted , the paper is sent to production. If the article is rejected or sent back for either major or minor revision , the handling editor should include constructive comments from the reviewers to help the author improve the article. At this point, reviewers should also be sent an email or letter letting them know the outcome of their review. If the paper was sent back for revision , the reviewers should expect to receive a new version, unless they have opted out of further participation. However, where only minor changes were requested this follow-up review might be done by the handling editor.

Page Content

What is the reviewer looking for, possible outcomes of peer review, common reasons for rejection, what to do if your manuscript gets rejected, responding to the reviewer, peer review.

You want your work to be the best it can possibly be, and that’s where peer review comes in.

Learn more with Wiley Research Academy

This online, on-demand learning program guides you through the publishing process. Take courses to build your skills and understanding, including our course on peer review and responding to reviewer comments. Sign up for a free trial today!

Your work is shared with experts in your field of study in order to gain their insight and suggestions. Reviewers will evaluate the originality and thoroughness of your work, and whether it is within scope for the journal you have submitted to. There are many forms of peer review , from traditional models like single-blind and double-blind review to newer models, such as open and transferable review. Learn about our Transparent Peer Review pilot in collaboration with Publons and ScholarOne (part of Clarivate, Web of Science).

The length of the peer review process varies by journal, so check with the editors or the staff of the journal to which you are submitting to for details of the process for that particular journal. Click here to read Wiley’s review confidentiality policy and check the review model for each journal we publish.

Originality, scientific significance, conciseness, precision, and completeness

In general, at first read-through reviewers will be assessing your argument’s construction, the clarity of the language, and content. They will be asking themselves the following questions:

- What is the main question addressed by the research? Is it relevant and interesting?

- How original is the topic? What does it add to the subject area compared with other published material?

- Is the paper well written? Is the text clear and easy to read?

- Are the conclusions consistent with the evidence and arguments presented? Do they address the main question posed?

- If the author is disagreeing significantly with the current academic consensus, do they have a substantial case? If not, what would be required to make their case credible?

- If the paper includes tables or figures, what do they add to the paper? Do they aid understanding or are they superfluous?

- Is the argument well-constructed and clear? Are there any factual errors or invalid arguments?

They may also consider the following:

- Does the title properly reflect the subject of the paper?

- Does the abstract provide an accessible summary of the paper?

- Do the keywords accurately reflect the content?

- Does the paper follow a clear and organized structure?

- Is the paper an appropriate length?

- Are the key messages short, accurate and clear?

Upon closer readings, the reviewer will be looking for any major issues:

- Are there any major flaws?

- If experimental design features prominently in the paper, is the methodology sound?

- Is the research replicable, reproducible, and robust? Does it follow best practice and meet ethical standards?

- Has similar work already been published without the authors acknowledging this?

- Are there published studies that show similar or dissimilar trends that should be discussed?

- Are the authors presenting findings that challenge current thinking? Is the evidence they present strong enough to prove their case? Have they cited all the relevant work that would contradict their thinking and addressed it appropriately?

- Are there any major presentational problems? Are figures & tables, language and manuscript structure all clear enough to accurately assess the work?

- Are there any ethical issues?

The reviewer will also note minor issues that need to be corrected:

- Are the correct references cited? Are citations excessive, limited, or biased?

- Are there any factual, numerical, or unit errors? If so, what are they?

- Are all tables and figures appropriate, sufficient, and correctly labelled?

The journal’s editor or editorial board considers the feedback provided by the peer reviewers and uses this information to arrive at a decision. In addition to the comments received from the review, editors also base their decisions on:

- The journal’s aims and audience

- The state of knowledge in the field

- The level of competition for acceptance and page space within the journal

The following represent the range of possible outcomes:

- Accept without any changes (acceptance): The journal will publish the paper in its original form. This type of decision outcome is rare

- Accept with minor revisions (acceptance): The journal will publish the paper and asks the author to make small corrections. This is typically the best outcome that authors should hope for

- Accept after major revisions (conditional acceptance): The journal will publish the paper provided the authors make the changes suggested by the reviewers and/or editors

- Revise and resubmit (conditional rejection): The journal is willing to reconsider the paper in another round of decision making after the authors make major changes

- Reject the paper (outright rejection): The journal will not publish the paper or reconsider it even if the authors make major revisions

The decision outcome will be accompanied by the reviewer reports and some commentary from the editor that explains why the decision has been reached. If the decision involves revision for the author, the specific changes that are required should be clearly stated in the decision letter and review reports. The author can then respond to each point in turn.

The manuscript fails the technical screening: Before manuscripts are sent to the EIC or handling editor, many editorial offices first perform some checks. The main reasons that papers can be rejected at this stage are:

- The article contains elements that are suspected to be plagiarized, or it is currently under review at another journal (submitting the same paper to multiple journals at the same time is not allowed)

- The manuscript is insufficiently well prepared; for example, lacking key elements such as the title, authors, affiliations, keywords, main text, references, and tables and figures

- The English is not of sufficient quality to allow a useful peer review to take place

- The figures are not complete or are not clear enough to read

- The article does not conform to the most important aspects of the specific journal’s Author Guidelines

The manuscript does not fall within the Aims and Scope of the journal: The work is not of interest to the readers of the specific journal

The manuscript is incomplete: For example, the article contains observations but is not a full study or it discusses findings in relation to some of the work in the field but ignores other important work

A clear hypothesis or research aim was not established or the question behind the work is not of interest in the field

The goal of the research was over-ambitious, and hence it could not realistically be achieved

There are flaws in the procedures and/or analysis of the data:

- The study lacked clear control groups or other comparison metrics

- The study did not conform to recognized procedures or methodology that can be repeated

- The analysis is not statistically valid or does not follow the norms of the field

The conclusions were exaggerated: The conclusions cannot be justified on the basis of the rest of the paper

- The arguments are illogical, unstructured or invalid

- The data do not support the conclusions

- The conclusions ignore large portions of the literature

The research topic was of little significance:

- It is archival, or of marginal interest to the field; it is simply a small extension of a different paper, often from the same authors

- Findings are incremental and do not significantly advance the field

- The work is clearly part of a larger study, chopped up to make as many articles as possible (so-called “salami publication”)

Bad writing: If the language, structure, or figures are so poor that the merit of the paper can’t be assessed, then the paper will be rejected. It’s a good idea to ask a native English speaker to read the paper before submitting. Wiley Editing Services offers English Language Editing services, which you can use prior to submission if you are not confident in the quality of your English writing skills

It is very common for papers to be rejected. Studies indicate that 21% of papers are rejected without review, and approximately 40% of papers are rejected after peer review.

If your paper has been rejected prior to peer review due to lack of subject fit, then find a new journal to submit your work to and move on.

However, if you receive a rejection after your paper has been reviewed, you will have a rich source of information about possible improvements that you could make. You have the following options:

Make the recommended changes and resubmit to the same journal:

This option could well be your top choice if you are keen to publish in a particular journal and if the editor has indicated that they will accept your paper if revisions are made. If the editor has issued an outright rejection and does not wish to reconsider the paper, you should respect this decision and submit to a different journal.

Make changes and submit to a different journal:

If you decide to try a different journal, you should still carefully consider the comments you received during the first round of review, and work on improving your manuscript before submitting elsewhere. Make sure that you adjust details like the cover letter, referencing and any other journal specific details before submitting to a different journal.

Make no changes and submit to a different journal:

While this option is an easy one, it is not recommended. It’s likely that many of the suggestions made during the original review would lead to an improved paper and by not addressing these points you are wasting a) the effort expended in the first round of review, and b) the opportunity to increase your chances of acceptance at the next journal. Furthermore, there is a chance that your manuscript may be assessed by the same reviewers at a new journal (particularly if you are publishing in a niche field). In this case, their recommendation will not change if you have not addressed the concerns raised in their earlier review. One exception would be if you are submitting to a journal that participates in a transfer program , where authors can agree to have their manuscript and reviews transferred to a new journal for consideration without making changes.

Appeal against the decision:

The journal should have a publicly described policy for appealing against editorial decisions. If you feel that the decision was based on an unfair assessment of your paper, or that there were major errors in the review process, then you are within your rights as an author to appeal. If you wish to appeal a decision, take the time to research that journal’s appeal process and review and address the points raised by the reviewer to prepare a reasoned and logical response.

Throw the manuscript away and never resubmit it:

Rejection can be disheartening, and it may be tempting to decide that it’s not worth the trouble of resubmitting. But, this is not the best outcome for either you or the wider research community. Your data may be highly valuable to someone else, or may help another researcher to avoid generating similar negative results.

You may not be able to control what the reviewers write in their review comments, but you can control the way you react to their comments. It’s useful to remember these points:

Reviewers have, on the whole, given time and effort to constructively criticize your article

Reviewers are volunteers and have given up their own time to evaluate your paper in order to contribute to the research community. Reviewers very rarely receive formal compensation beyond recognition from the editors of the effort they have expended. The author will get the ultimate credit, but reviewers are often key contributors to the shape of the final paper. Although the comments you receive may feel harsh, most reviewers are also authors and therefore will be trying to highlight how the paper could be improved. So, it is important to be grateful for the time that both reviewers and editors have spent evaluating your paper – and to express this gratitude in your response.

The importance of good manners

You should remain polite and thoughtful throughout any and all response to reviewers and editors. You are much more likely to receive a positive response in return and this will help build a constructive relationship with both reviewer and editor in the future.

Don’t take criticism as a personal attack

As stated previously, it is very rare that a paper will be accepted without any form of revisions requested. It is the job of the editor and reviewer to make sure that the published papers are scientifically sound, factual, clear and complete. In order to achieve this, it will be necessary to draw attention to areas of improvement. While this may be difficult for you as an author, the criticism received is not intended to be personal.

Avoid personalizing responses to the reviewer

Sticking to the facts and avoiding personal attacks is imperative. It’s a good idea to wait 24 to 72 hours before responding to a decision letter—then re-read the email. This simple process will remove much of the personal bias that could pollute appeals letters written in rage or disappointment. If you respond in anger, or in an argumentative fashion the editor and reviewers are much less likely to respond favorably.

Remember, even if you think the reviewer is wrong, this doesn’t necessarily mean that you are right! It is possible that the reviewer has made a mistake, but it is also possible that the reviewer was not able to understand your point because of a lack of clarity, or omission of crucial detail in your paper.

Evaluating the reviewer comments and planning your response

After you have read the decision letter and the reviewers comments, wait for at least 24 hours, then take a fresh look at the comments provided. This will help to neutralize the initial emotional response you may have and allow you to determine what the reviewers are asking for in a more objective manner.

Spending time assessing the scope of the revisions requested will help you evaluate the extent of effort required and prioritize the work you may need to undertake. It will also help you to provide a comprehensive response in your letter of reply.

Some useful steps to consider:

- Make a list of all the reviewer comments and number them

- Categorize the list as follows

- requests for clarification of existing text, addition of text to fill a gap in the paper, or additional experimental details

- requests to reanalyze, re-express, or reinterpret existing data

- requests for additional experiments or further proof of concept

- requests you simply cannot meet

- Note down the action/response that you plan to undertake for each comment. If there are requests that you cannot meet, you need to address these in your response – providing a logical, reasoned explanation for why the study is not detrimentally affected by not making the changes requested

Want to become a peer reviewer? Learn more about peer review, including how to become a reviewer in our Reviewer Resource Center .

Further reading:

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Methodology

- What Is Peer Review? | Types & Examples

What Is Peer Review? | Types & Examples

Published on 6 May 2022 by Tegan George . Revised on 2 September 2022.

Peer review, sometimes referred to as refereeing , is the process of evaluating submissions to an academic journal. Using strict criteria, a panel of reviewers in the same subject area decides whether to accept each submission for publication.

Peer-reviewed articles are considered a highly credible source due to the stringent process they go through before publication.

There are various types of peer review. The main difference between them is to what extent the authors, reviewers, and editors know each other’s identities. The most common types are:

- Single-blind review

- Double-blind review

- Triple-blind review

Collaborative review

Open review.

Relatedly, peer assessment is a process where your peers provide you with feedback on something you’ve written, based on a set of criteria or benchmarks from an instructor. They then give constructive feedback, compliments, or guidance to help you improve your draft.

Table of contents

What is the purpose of peer review, types of peer review, the peer review process, providing feedback to your peers, peer review example, advantages of peer review, criticisms of peer review, frequently asked questions about peer review.

Many academic fields use peer review, largely to determine whether a manuscript is suitable for publication. Peer review enhances the credibility of the manuscript. For this reason, academic journals are among the most credible sources you can refer to.

However, peer review is also common in non-academic settings. The United Nations, the European Union, and many individual nations use peer review to evaluate grant applications. It is also widely used in medical and health-related fields as a teaching or quality-of-care measure.

Peer assessment is often used in the classroom as a pedagogical tool. Both receiving feedback and providing it are thought to enhance the learning process, helping students think critically and collaboratively.

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

Depending on the journal, there are several types of peer review.

Single-blind peer review

The most common type of peer review is single-blind (or single anonymised) review . Here, the names of the reviewers are not known by the author.

While this gives the reviewers the ability to give feedback without the possibility of interference from the author, there has been substantial criticism of this method in the last few years. Many argue that single-blind reviewing can lead to poaching or intellectual theft or that anonymised comments cause reviewers to be too harsh.

Double-blind peer review

In double-blind (or double anonymised) review , both the author and the reviewers are anonymous.

Arguments for double-blind review highlight that this mitigates any risk of prejudice on the side of the reviewer, while protecting the nature of the process. In theory, it also leads to manuscripts being published on merit rather than on the reputation of the author.

Triple-blind peer review

While triple-blind (or triple anonymised) review – where the identities of the author, reviewers, and editors are all anonymised – does exist, it is difficult to carry out in practice.

Proponents of adopting triple-blind review for journal submissions argue that it minimises potential conflicts of interest and biases. However, ensuring anonymity is logistically challenging, and current editing software is not always able to fully anonymise everyone involved in the process.

In collaborative review , authors and reviewers interact with each other directly throughout the process. However, the identity of the reviewer is not known to the author. This gives all parties the opportunity to resolve any inconsistencies or contradictions in real time, and provides them a rich forum for discussion. It can mitigate the need for multiple rounds of editing and minimise back-and-forth.

Collaborative review can be time- and resource-intensive for the journal, however. For these collaborations to occur, there has to be a set system in place, often a technological platform, with staff monitoring and fixing any bugs or glitches.

Lastly, in open review , all parties know each other’s identities throughout the process. Often, open review can also include feedback from a larger audience, such as an online forum, or reviewer feedback included as part of the final published product.

While many argue that greater transparency prevents plagiarism or unnecessary harshness, there is also concern about the quality of future scholarship if reviewers feel they have to censor their comments.

In general, the peer review process includes the following steps:

- First, the author submits the manuscript to the editor.

- Reject the manuscript and send it back to the author, or

- Send it onward to the selected peer reviewer(s)

- Next, the peer review process occurs. The reviewer provides feedback, addressing any major or minor issues with the manuscript, and gives their advice regarding what edits should be made.

- Lastly, the edited manuscript is sent back to the author. They input the edits and resubmit it to the editor for publication.

In an effort to be transparent, many journals are now disclosing who reviewed each article in the published product. There are also increasing opportunities for collaboration and feedback, with some journals allowing open communication between reviewers and authors.

It can seem daunting at first to conduct a peer review or peer assessment. If you’re not sure where to start, there are several best practices you can use.

Summarise the argument in your own words

Summarising the main argument helps the author see how their argument is interpreted by readers, and gives you a jumping-off point for providing feedback. If you’re having trouble doing this, it’s a sign that the argument needs to be clearer, more concise, or worded differently.

If the author sees that you’ve interpreted their argument differently than they intended, they have an opportunity to address any misunderstandings when they get the manuscript back.

Separate your feedback into major and minor issues

It can be challenging to keep feedback organised. One strategy is to start out with any major issues and then flow into the more minor points. It’s often helpful to keep your feedback in a numbered list, so the author has concrete points to refer back to.

Major issues typically consist of any problems with the style, flow, or key points of the manuscript. Minor issues include spelling errors, citation errors, or other smaller, easy-to-apply feedback.

The best feedback you can provide is anything that helps them strengthen their argument or resolve major stylistic issues.

Give the type of feedback that you would like to receive

No one likes being criticised, and it can be difficult to give honest feedback without sounding overly harsh or critical. One strategy you can use here is the ‘compliment sandwich’, where you ‘sandwich’ your constructive criticism between two compliments.

Be sure you are giving concrete, actionable feedback that will help the author submit a successful final draft. While you shouldn’t tell them exactly what they should do, your feedback should help them resolve any issues they may have overlooked.

As a rule of thumb, your feedback should be:

- Easy to understand

- Constructive

Below is a brief annotated research example. You can view examples of peer feedback by hovering over the highlighted sections.

Influence of phone use on sleep

Studies show that teens from the US are getting less sleep than they were a decade ago (Johnson, 2019) . On average, teens only slept for 6 hours a night in 2021, compared to 8 hours a night in 2011. Johnson mentions several potential causes, such as increased anxiety, changed diets, and increased phone use.

The current study focuses on the effect phone use before bedtime has on the number of hours of sleep teens are getting.

For this study, a sample of 300 teens was recruited using social media, such as Facebook, Instagram, and Snapchat. The first week, all teens were allowed to use their phone the way they normally would, in order to obtain a baseline.

The sample was then divided into 3 groups:

- Group 1 was not allowed to use their phone before bedtime.

- Group 2 used their phone for 1 hour before bedtime.

- Group 3 used their phone for 3 hours before bedtime.

All participants were asked to go to sleep around 10 p.m. to control for variation in bedtime . In the morning, their Fitbit showed the number of hours they’d slept. They kept track of these numbers themselves for 1 week.

Two independent t tests were used in order to compare Group 1 and Group 2, and Group 1 and Group 3. The first t test showed no significant difference ( p > .05) between the number of hours for Group 1 ( M = 7.8, SD = 0.6) and Group 2 ( M = 7.0, SD = 0.8). The second t test showed a significant difference ( p < .01) between the average difference for Group 1 ( M = 7.8, SD = 0.6) and Group 3 ( M = 6.1, SD = 1.5).

This shows that teens sleep fewer hours a night if they use their phone for over an hour before bedtime, compared to teens who use their phone for 0 to 1 hours.

Peer review is an established and hallowed process in academia, dating back hundreds of years. It provides various fields of study with metrics, expectations, and guidance to ensure published work is consistent with predetermined standards.

- Protects the quality of published research

Peer review can stop obviously problematic, falsified, or otherwise untrustworthy research from being published. Any content that raises red flags for reviewers can be closely examined in the review stage, preventing plagiarised or duplicated research from being published.

- Gives you access to feedback from experts in your field

Peer review represents an excellent opportunity to get feedback from renowned experts in your field and to improve your writing through their feedback and guidance. Experts with knowledge about your subject matter can give you feedback on both style and content, and they may also suggest avenues for further research that you hadn’t yet considered.

- Helps you identify any weaknesses in your argument

Peer review acts as a first defence, helping you ensure your argument is clear and that there are no gaps, vague terms, or unanswered questions for readers who weren’t involved in the research process. This way, you’ll end up with a more robust, more cohesive article.

While peer review is a widely accepted metric for credibility, it’s not without its drawbacks.

- Reviewer bias

The more transparent double-blind system is not yet very common, which can lead to bias in reviewing. A common criticism is that an excellent paper by a new researcher may be declined, while an objectively lower-quality submission by an established researcher would be accepted.

- Delays in publication

The thoroughness of the peer review process can lead to significant delays in publishing time. Research that was current at the time of submission may not be as current by the time it’s published.

- Risk of human error

By its very nature, peer review carries a risk of human error. In particular, falsification often cannot be detected, given that reviewers would have to replicate entire experiments to ensure the validity of results.

Peer review is a process of evaluating submissions to an academic journal. Utilising rigorous criteria, a panel of reviewers in the same subject area decide whether to accept each submission for publication.

For this reason, academic journals are often considered among the most credible sources you can use in a research project – provided that the journal itself is trustworthy and well regarded.

Peer review can stop obviously problematic, falsified, or otherwise untrustworthy research from being published. It also represents an excellent opportunity to get feedback from renowned experts in your field.

It acts as a first defence, helping you ensure your argument is clear and that there are no gaps, vague terms, or unanswered questions for readers who weren’t involved in the research process.

Peer-reviewed articles are considered a highly credible source due to this stringent process they go through before publication.

In general, the peer review process follows the following steps:

- Reject the manuscript and send it back to author, or

- Lastly, the edited manuscript is sent back to the author. They input the edits, and resubmit it to the editor for publication.

Many academic fields use peer review , largely to determine whether a manuscript is suitable for publication. Peer review enhances the credibility of the published manuscript.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

George, T. (2022, September 02). What Is Peer Review? | Types & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved 15 April 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/research-methods/peer-reviews/

Is this article helpful?

Tegan George

Other students also liked, what is a double-blind study | introduction & examples, a quick guide to experimental design | 5 steps & examples, data cleaning | a guide with examples & steps.

Disclaimer » Advertising

- HealthyChildren.org

- Previous Article

- Next Article

What is the Purpose of Peer Review?

What makes a good peer reviewer, how do you decide whether to review a paper, how do you complete a peer review, limitations of peer review, conclusions, research methods: how to perform an effective peer review.

- Split-Screen

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

- Peer Review

- CME Quiz Close Quiz

- Open the PDF for in another window

- Get Permissions

- Cite Icon Cite

- Search Site

Elise Peterson Lu , Brett G. Fischer , Melissa A. Plesac , Andrew P.J. Olson; Research Methods: How to Perform an Effective Peer Review. Hosp Pediatr November 2022; 12 (11): e409–e413. https://doi.org/10.1542/hpeds.2022-006764

Download citation file:

- Ris (Zotero)

- Reference Manager

Scientific peer review has existed for centuries and is a cornerstone of the scientific publication process. Because the number of scientific publications has rapidly increased over the past decades, so has the number of peer reviews and peer reviewers. In this paper, drawing on the relevant medical literature and our collective experience as peer reviewers, we provide a user guide to the peer review process, including discussion of the purpose and limitations of peer review, the qualities of a good peer reviewer, and a step-by-step process of how to conduct an effective peer review.

Peer review has been a part of scientific publications since 1665, when the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society became the first publication to formalize a system of expert review. 1 , 2 It became an institutionalized part of science in the latter half of the 20 th century and is now the standard in scientific research publications. 3 In 2012, there were more than 28 000 scholarly peer-reviewed journals and more than 3 million peer reviewed articles are now published annually. 3 , 4 However, even with this volume, most peer reviewers learn to review “on the (unpaid) job” and no standard training system exists to ensure quality and consistency. 5 Expectations and format vary between journals and most, but not all, provide basic instructions for reviewers. In this paper, we provide a general introduction to the peer review process and identify common strategies for success as well as pitfalls to avoid.

Modern peer review serves 2 primary purposes: (1) as “a screen before the diffusion of new knowledge” 6 and (2) as a method to improve the quality of published work. 1 , 5

As screeners, peer reviewers evaluate the quality, validity, relevance, and significance of research before publication to maintain the credibility of the publications they serve and their fields of study. 1 , 2 , 7 Although peer reviewers are not the final decision makers on publication (that role belongs to the editor), their recommendations affect editorial decisions and thoughtful comments influence an article’s fate. 6 , 8

As advisors and evaluators of manuscripts, reviewers have an opportunity and responsibility to give authors an outside expert’s perspective on their work. 9 They provide feedback that can improve methodology, enhance rigor, improve clarity, and redefine the scope of articles. 5 , 8 , 10 This often happens even if a paper is not ultimately accepted at the reviewer’s journal because peer reviewers’ comments are incorporated into revised drafts that are submitted to another journal. In a 2019 survey of authors, reviewers, and editors, 83% said that peer review helps science communication and 90% of authors reported that peer review improved their last paper. 11

Expertise: Peer reviewers should be up to date with current literature, practice guidelines, and methodology within their subject area. However, academic rank and seniority do not define expertise and are not actually correlated with performance in peer review. 13

Professionalism: Reviewers should be reliable and objective, aware of their own biases, and respectful of the confidentiality of the peer review process.

Critical skill : Reviewers should be organized, thorough, and detailed in their critique with the goal of improving the manuscript under their review, regardless of disposition. They should provide constructive comments that are specific and addressable, referencing literature when possible. A peer reviewer should leave a paper better than he or she found it.

Is the manuscript within your area of expertise? Generally, if you are asked to review a paper, it is because an editor felt that you were a qualified expert. In a 2019 survey, 74% of requested reviews were within the reviewer’s area of expertise. 11 This, of course, does not mean that you must be widely published in the area, only that you have enough expertise and comfort with the topic to critique and add to the paper.

Do you have any biases that may affect your review? Are there elements of the methodology, content area, or theory with which you disagree? Some disagreements between authors and reviewers are common, expected, and even helpful. However, if a reviewer fundamentally disagrees with an author’s premise such that he or she cannot be constructive, the review invitation should be declined.

Do you have the time? The average review for a clinical journal takes 5 to 6 hours, though many take longer depending on the complexity of the research and the experience of the reviewer. 1 , 14 Journals vary on the requested timeline for return of reviews, though it is usually 1 to 4 weeks. Peer review is often the longest part of the publication process and delays contribute to slower dissemination of important work and decreased author satisfaction. 15 Be mindful of your schedule and only accept a review invitation if you can reasonably return the review in the requested time.

Once you have determined that you are the right person and decided to take on the review, reply to the inviting e-mail or click the associated link to accept (or decline) the invitation. Journal editors invite a limited number of reviewers at a time and wait for responses before inviting others. A common complaint among journal editors surveyed was that reviewers would often take days to weeks to respond to requests, or not respond at all, making it difficult to find appropriate reviewers and prolonging an already long process. 5

Now that you have decided to take on the review, it is best of have a systematic way of both evaluating the manuscript and writing the review. Various suggestions exist in the literature, but we will describe our standard procedure for review, incorporating specific do’s and don’ts summarized in Table 1 .

Dos and Don’ts of Peer Review

First, read the manuscript once without making notes or forming opinions to get a sense of the paper as whole. Assess the overall tone and flow and define what the authors identify as the main point of their work. Does the work overall make sense? Do the authors tell the story effectively?

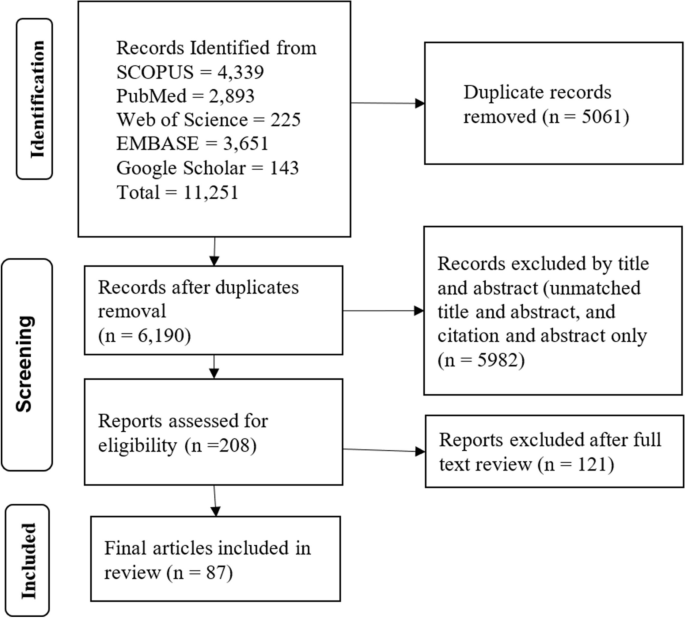

Next, read the manuscript again with an eye toward review, taking notes and formulating thoughts on strengths and weaknesses. Consider the methodology and identify the specific type of research described. Refer to the corresponding reporting guideline if applicable (CONSORT for randomized control trials, STROBE for observational studies, PRISMA for systematic reviews). Reporting guidelines often include a checklist, flow diagram, or structured text giving a minimum list of information needed in a manuscript based on the type of research done. 16 This allows the reviewer to formulate a more nuanced and specific assessment of the manuscript.

Next, review the main findings, the significance of the work, and what contribution it makes to the field. Examine the presentation and flow of the manuscript but do not copy edit the text. At this point, you should start to write your review. Some journals provide a format for their reviews, but often it is up to the reviewer. In surveys of journal editors and reviewers, a review organized by manuscript section was the most favored, 5 , 6 so that is what we will describe here.

As you write your review, consider starting with a brief summary of the work that identifies the main topic, explains the basic approach, and describes the findings and conclusions. 12 , 17 Though not universally included in all reviews, we have found this step to be helpful in ensuring that the work is conveyed clearly enough for the reviewer to summarize it. Include brief notes on the significance of the work and what it adds to current knowledge. Critique the presentation of the work: is it clearly written? Is its length appropriate? List any major concerns with the work overall, such as major methodological flaws or inaccurate conclusions that should disqualify it from publication, though do not comment directly on disposition. Then perform your review by section:

Abstract : Is it consistent with the rest of the paper? Does it adequately describe the major points?

Introduction : This section should provide adequate background to explain the need for the study. Generally, classic or highly relevant studies should be cited, but citations do not have to be exhaustive. The research question and hypothesis should be clearly stated.

Methods: Evaluate both the methods themselves and the way in which they are explained. Does the methodology used meet the needs of the questions proposed? Is there sufficient detail to explain what the authors did and, if not, what needs to be added? For clinical research, examine the inclusion/exclusion criteria, control populations, and possible sources of bias. Reporting guidelines can be particularly helpful in determining the appropriateness of the methods and how they are reported.

Some journals will expect an evaluation of the statistics used, whereas others will have a separate statistician evaluate, and the reviewers are generally not expected to have an exhaustive knowledge of statistical methods. Clarify expectations if needed and, if you do not feel qualified to evaluate the statistics, make this clear in your review.

Results: Evaluate the presentation of the results. Is information given in sufficient detail to assess credibility? Are the results consistent with the methodology reported? Are the figures and tables consistent with the text, easy to interpret, and relevant to the work? Make note of data that could be better detailed in figures or tables, rather than included in the text. Make note of inappropriate interpretation in the results section (this should be in discussion) or rehashing of methods.

Discussion: Evaluate the authors’ interpretation of their results, how they address limitations, and the implications of their work. How does the work contribute to the field, and do the authors adequately describe those contributions? Make note of overinterpretation or conclusions not supported by the data.

The length of your review often correlates with your opinion of the quality of the work. If an article has major flaws that you think preclude publication, write a brief review that focuses on the big picture. Articles that may not be accepted but still represent quality work merit longer reviews aimed at helping the author improve the work for resubmission elsewhere.

Generally, do not include your recommendation on disposition in the body of the review itself. Acceptance or rejection is ultimately determined by the editor and including your recommendation in your comments to the authors can be confusing. A journal editor’s decision on acceptance or rejection may depend on more factors than just the quality of the work, including the subject area, journal priorities, other contemporaneous submissions, and page constraints.

Many submission sites include a separate question asking whether to accept, accept with major revision, or reject. If this specific format is not included, then add your recommendation in the “confidential notes to the editor.” Your recommendation should be consistent with the content of your review: don’t give a glowing review but recommend rejection or harshly criticize a manuscript but recommend publication. Last, regardless of your ultimate recommendation on disposition, it is imperative to use respectful and professional language and tone in your written review.

Although peer review is often described as the “gatekeeper” of science and characterized as a quality control measure, peer review is not ideally designed to detect fundamental errors, plagiarism, or fraud. In multiple studies, peer reviewers detected only 20% to 33% of intentionally inserted errors in scientific manuscripts. 18 , 19 Plagiarism similarly is not detected in peer review, largely because of the huge volume of literature available to plagiarize. Most journals now use computer software to identify plagiarism before a manuscript goes to peer review. Finally, outright fraud often goes undetected in peer review. Reviewers start from a position of respect for the authors and trust the data they are given barring obvious inconsistencies. Ultimately, reviewers are “gatekeepers, not detectives.” 7

Peer review is also limited by bias. Even with the best of intentions, reviewers bring biases including but not limited to prestige bias, affiliation bias, nationality bias, language bias, gender bias, content bias, confirmation bias, bias against interdisciplinary research, publication bias, conservatism, and bias of conflict of interest. 3 , 4 , 6 For example, peer reviewers score methodology higher and are more likely to recommend publication when prestigious author names or institutions are visible. 20 Although bias can be mitigated both by the reviewer and by the journal, it cannot be eliminated. Reviewers should be mindful of their own biases while performing reviews and work to actively mitigate them. For example, if English language editing is necessary, state this with specific examples rather than suggesting the authors seek editing by a “native English speaker.”

Peer review is an essential, though imperfect, part of the forward movement of science. Peer review can function as both a gatekeeper to protect the published record of science and a mechanism to improve research at the level of individual manuscripts. Here, we have described our strategy, summarized in Table 2 , for performing a thorough peer review, with a focus on organization, objectivity, and constructiveness. By using a systematized strategy to evaluate manuscripts and an organized format for writing reviews, you can provide a relatively objective perspective in editorial decision-making. By providing specific and constructive feedback to authors, you contribute to the quality of the published literature.

Take-home Points

FUNDING: No external funding.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST DISCLOSURES: The authors have indicated they have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

Dr Lu performed the literature review and wrote the manuscript. Dr Fischer assisted in the literature review and reviewed and edited the manuscript. Dr Plesac provided background information on the process of peer review, reviewed and edited the manuscript, and completed revisions. Dr Olson provided background information and practical advice, critically reviewed and revised the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript.

Advertising Disclaimer »

Citing articles via

Email alerts.

Affiliations

- Editorial Board

- Editorial Policies

- Pediatrics On Call

- Online ISSN 2154-1671

- Print ISSN 2154-1663

- Pediatrics Open Science

- Hospital Pediatrics

- Pediatrics in Review

- AAP Grand Rounds

- Latest News

- Pediatric Care Online

- Red Book Online

- Pediatric Patient Education

- AAP Toolkits

- AAP Pediatric Coding Newsletter

First 1,000 Days Knowledge Center

Institutions/librarians, group practices, licensing/permissions, integrations, advertising.

- Privacy Statement | Accessibility Statement | Terms of Use | Support Center | Contact Us

- © Copyright American Academy of Pediatrics

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

Explainer: what is peer review?

Professor of Organisational Behaviour, Cass Business School, City, University of London

Novak Druce Research Fellow, University of Oxford

Disclosure statement

Thomas Roulet does not work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has no relevant affiliations.

Andre Spicer does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

City, University of London provides funding as a founding partner of The Conversation UK.

University of Oxford provides funding as a member of The Conversation UK.

View all partners

We’ve all heard the phrase “peer review” as giving credence to research and scholarly papers, but what does it actually mean? How does it work?

Peer review is one of the gold standards of science. It’s a process where scientists (“peers”) evaluate the quality of other scientists’ work. By doing this, they aim to ensure the work is rigorous, coherent, uses past research and adds to what we already knew.

Most scientific journals, conferences and grant applications have some sort of peer review system. In most cases it is “double blind” peer review. This means evaluators do not know the author(s), and the author(s) do not know the identity of the evaluators. The intention behind this system is to ensure evaluation is not biased.

The more prestigious the journal, conference, or grant, the more demanding will be the review process, and the more likely the rejection. This prestige is why these papers tend to be more read and more cited.

The process in details

The peer review process for journals involves at least three stages.

1. The desk evaluation stage

When a paper is submitted to a journal, it receives an initial evaluation by the chief editor, or an associate editor with relevant expertise.

At this stage, either can “desk reject” the paper: that is, reject the paper without sending it to blind referees. Generally, papers are desk rejected if the paper doesn’t fit the scope of the journal or there is a fundamental flaw which makes it unfit for publication.

In this case, the rejecting editors might write a letter summarising his or her concerns. Some journals, such as the British Medical Journal , desk reject up to two-thirds or more of the papers.

2. The blind review

If the editorial team judges there are no fundamental flaws, they send it for review to blind referees. The number of reviewers depends on the field: in finance there might be only one reviewer, while journals in other fields of social sciences might ask up to four reviewers. Those reviewers are selected by the editor on the basis of their expert knowledge and their absence of a link with the authors.

Reviewers will decide whether to reject the paper, to accept it as it is (which rarely happens) or to ask for the paper to be revised. This means the author needs to change the paper in line with the reviewers’ concerns.

Usually the reviews deal with the validity and rigour of the empirical method, and the importance and originality of the findings (what is called the “contribution” to the existing literature). The editor collects those comments, weights them, takes a decision, and writes a letter summarising the reviewers’ and his or her own concerns.

It can therefore happen that despite hostility on the part of the reviewers, the editor could offer the paper a subsequent round of revision. In the best journals in the social sciences, 10% to 20% of the papers are offered a “revise-and-resubmit” after the first round.

3. The revisions – if you are lucky enough

If the paper has not been rejected after this first round of review, it is sent back to the author(s) for a revision. The process is repeated as many times as necessary for the editor to reach a consensus point on whether to accept or reject the paper. In some cases this can last for several years.

Ultimately, less than 10% of the submitted papers are accepted in the best journals in the social sciences. The renowned journal Nature publishes around 7% of the submitted papers.

Strengths and weaknesses of the peer review process

The peer review process is seen as the gold standard in science because it ensures the rigour, novelty, and consistency of academic outputs. Typically, through rounds of review, flawed ideas are eliminated and good ideas are strengthened and improved. Peer reviewing also ensures that science is relatively independent.

Because scientific ideas are judged by other scientists, the crucial yardstick is scientific standards. If other people from outside of the field were involved in judging ideas, other criteria such as political or economic gain might be used to select ideas. Peer reviewing is also seen as a crucial way of removing personalities and bias from the process of judging knowledge.

Despite the undoubted strengths, the peer review process as we know it has been criticised . It involves a number of social interactions that might create biases – for example, authors might be identified by reviewers if they are in the same field, and desk rejections are not blind.

It might also favour incremental (adding to past research) rather than innovative (new) research. Finally, reviewers are human after all and can make mistakes, misunderstand elements, or miss errors.

Are there any alternatives?

Defenders of the peer review system say although there are flaws, we’re yet to find a better system to evaluate research. However, a number of innovations have been introduced in the academic review system to improve its objectivity and efficiency.

Some new open-access journals (such as PLOS ONE ) publish papers with very little evaluation (they check the work is not deeply flawed methodologically). The focus there is on the post-publication peer review system: all readers can comment and criticise the paper.

Some journals such as Nature, have made part of the review process public (“open” review), offering a hybrid system in which peer review plays a role of primary gate keepers, but the public community of scholars judge in parallel (or afterwards in some other journals) the value of the research.

Another idea is to have a set of reviewers rating the paper each time it is revised. In this case, authors will be able to choose whether they want to invest more time in a revision to obtain a better rating, and get their work publicly recognised.

- Peer review

Sydney Horizon Educators (Identified)

Senior Disability Services Advisor

Deputy Social Media Producer

Associate Professor, Occupational Therapy

GRAINS RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT CORPORATION CHAIRPERSON

Peer Review Process: Understanding The Pathway To Publication

Demystifying peer review process: Insights into the rigorous evaluation process shaping scholarly research and ensuring academic quality.