- Previous Article

- Next Article

Promises and Pitfalls of Technology

Politics and privacy, private-sector influence and big tech, state competition and conflict, author biography, how is technology changing the world, and how should the world change technology.

- Split-Screen

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

- Peer Review

- Open the PDF for in another window

- Guest Access

- Get Permissions

- Cite Icon Cite

- Search Site

Josephine Wolff; How Is Technology Changing the World, and How Should the World Change Technology?. Global Perspectives 1 February 2021; 2 (1): 27353. doi: https://doi.org/10.1525/gp.2021.27353

Download citation file:

- Ris (Zotero)

- Reference Manager

Technologies are becoming increasingly complicated and increasingly interconnected. Cars, airplanes, medical devices, financial transactions, and electricity systems all rely on more computer software than they ever have before, making them seem both harder to understand and, in some cases, harder to control. Government and corporate surveillance of individuals and information processing relies largely on digital technologies and artificial intelligence, and therefore involves less human-to-human contact than ever before and more opportunities for biases to be embedded and codified in our technological systems in ways we may not even be able to identify or recognize. Bioengineering advances are opening up new terrain for challenging philosophical, political, and economic questions regarding human-natural relations. Additionally, the management of these large and small devices and systems is increasingly done through the cloud, so that control over them is both very remote and removed from direct human or social control. The study of how to make technologies like artificial intelligence or the Internet of Things “explainable” has become its own area of research because it is so difficult to understand how they work or what is at fault when something goes wrong (Gunning and Aha 2019) .

This growing complexity makes it more difficult than ever—and more imperative than ever—for scholars to probe how technological advancements are altering life around the world in both positive and negative ways and what social, political, and legal tools are needed to help shape the development and design of technology in beneficial directions. This can seem like an impossible task in light of the rapid pace of technological change and the sense that its continued advancement is inevitable, but many countries around the world are only just beginning to take significant steps toward regulating computer technologies and are still in the process of radically rethinking the rules governing global data flows and exchange of technology across borders.

These are exciting times not just for technological development but also for technology policy—our technologies may be more advanced and complicated than ever but so, too, are our understandings of how they can best be leveraged, protected, and even constrained. The structures of technological systems as determined largely by government and institutional policies and those structures have tremendous implications for social organization and agency, ranging from open source, open systems that are highly distributed and decentralized, to those that are tightly controlled and closed, structured according to stricter and more hierarchical models. And just as our understanding of the governance of technology is developing in new and interesting ways, so, too, is our understanding of the social, cultural, environmental, and political dimensions of emerging technologies. We are realizing both the challenges and the importance of mapping out the full range of ways that technology is changing our society, what we want those changes to look like, and what tools we have to try to influence and guide those shifts.

Technology can be a source of tremendous optimism. It can help overcome some of the greatest challenges our society faces, including climate change, famine, and disease. For those who believe in the power of innovation and the promise of creative destruction to advance economic development and lead to better quality of life, technology is a vital economic driver (Schumpeter 1942) . But it can also be a tool of tremendous fear and oppression, embedding biases in automated decision-making processes and information-processing algorithms, exacerbating economic and social inequalities within and between countries to a staggering degree, or creating new weapons and avenues for attack unlike any we have had to face in the past. Scholars have even contended that the emergence of the term technology in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries marked a shift from viewing individual pieces of machinery as a means to achieving political and social progress to the more dangerous, or hazardous, view that larger-scale, more complex technological systems were a semiautonomous form of progress in and of themselves (Marx 2010) . More recently, technologists have sharply criticized what they view as a wave of new Luddites, people intent on slowing the development of technology and turning back the clock on innovation as a means of mitigating the societal impacts of technological change (Marlowe 1970) .

At the heart of fights over new technologies and their resulting global changes are often two conflicting visions of technology: a fundamentally optimistic one that believes humans use it as a tool to achieve greater goals, and a fundamentally pessimistic one that holds that technological systems have reached a point beyond our control. Technology philosophers have argued that neither of these views is wholly accurate and that a purely optimistic or pessimistic view of technology is insufficient to capture the nuances and complexity of our relationship to technology (Oberdiek and Tiles 1995) . Understanding technology and how we can make better decisions about designing, deploying, and refining it requires capturing that nuance and complexity through in-depth analysis of the impacts of different technological advancements and the ways they have played out in all their complicated and controversial messiness across the world.

These impacts are often unpredictable as technologies are adopted in new contexts and come to be used in ways that sometimes diverge significantly from the use cases envisioned by their designers. The internet, designed to help transmit information between computer networks, became a crucial vehicle for commerce, introducing unexpected avenues for crime and financial fraud. Social media platforms like Facebook and Twitter, designed to connect friends and families through sharing photographs and life updates, became focal points of election controversies and political influence. Cryptocurrencies, originally intended as a means of decentralized digital cash, have become a significant environmental hazard as more and more computing resources are devoted to mining these forms of virtual money. One of the crucial challenges in this area is therefore recognizing, documenting, and even anticipating some of these unexpected consequences and providing mechanisms to technologists for how to think through the impacts of their work, as well as possible other paths to different outcomes (Verbeek 2006) . And just as technological innovations can cause unexpected harm, they can also bring about extraordinary benefits—new vaccines and medicines to address global pandemics and save thousands of lives, new sources of energy that can drastically reduce emissions and help combat climate change, new modes of education that can reach people who would otherwise have no access to schooling. Regulating technology therefore requires a careful balance of mitigating risks without overly restricting potentially beneficial innovations.

Nations around the world have taken very different approaches to governing emerging technologies and have adopted a range of different technologies themselves in pursuit of more modern governance structures and processes (Braman 2009) . In Europe, the precautionary principle has guided much more anticipatory regulation aimed at addressing the risks presented by technologies even before they are fully realized. For instance, the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation focuses on the responsibilities of data controllers and processors to provide individuals with access to their data and information about how that data is being used not just as a means of addressing existing security and privacy threats, such as data breaches, but also to protect against future developments and uses of that data for artificial intelligence and automated decision-making purposes. In Germany, Technische Überwachungsvereine, or TÜVs, perform regular tests and inspections of technological systems to assess and minimize risks over time, as the tech landscape evolves. In the United States, by contrast, there is much greater reliance on litigation and liability regimes to address safety and security failings after-the-fact. These different approaches reflect not just the different legal and regulatory mechanisms and philosophies of different nations but also the different ways those nations prioritize rapid development of the technology industry versus safety, security, and individual control. Typically, governance innovations move much more slowly than technological innovations, and regulations can lag years, or even decades, behind the technologies they aim to govern.

In addition to this varied set of national regulatory approaches, a variety of international and nongovernmental organizations also contribute to the process of developing standards, rules, and norms for new technologies, including the International Organization for Standardization and the International Telecommunication Union. These multilateral and NGO actors play an especially important role in trying to define appropriate boundaries for the use of new technologies by governments as instruments of control for the state.

At the same time that policymakers are under scrutiny both for their decisions about how to regulate technology as well as their decisions about how and when to adopt technologies like facial recognition themselves, technology firms and designers have also come under increasing criticism. Growing recognition that the design of technologies can have far-reaching social and political implications means that there is more pressure on technologists to take into consideration the consequences of their decisions early on in the design process (Vincenti 1993; Winner 1980) . The question of how technologists should incorporate these social dimensions into their design and development processes is an old one, and debate on these issues dates back to the 1970s, but it remains an urgent and often overlooked part of the puzzle because so many of the supposedly systematic mechanisms for assessing the impacts of new technologies in both the private and public sectors are primarily bureaucratic, symbolic processes rather than carrying any real weight or influence.

Technologists are often ill-equipped or unwilling to respond to the sorts of social problems that their creations have—often unwittingly—exacerbated, and instead point to governments and lawmakers to address those problems (Zuckerberg 2019) . But governments often have few incentives to engage in this area. This is because setting clear standards and rules for an ever-evolving technological landscape can be extremely challenging, because enforcement of those rules can be a significant undertaking requiring considerable expertise, and because the tech sector is a major source of jobs and revenue for many countries that may fear losing those benefits if they constrain companies too much. This indicates not just a need for clearer incentives and better policies for both private- and public-sector entities but also a need for new mechanisms whereby the technology development and design process can be influenced and assessed by people with a wider range of experiences and expertise. If we want technologies to be designed with an eye to their impacts, who is responsible for predicting, measuring, and mitigating those impacts throughout the design process? Involving policymakers in that process in a more meaningful way will also require training them to have the analytic and technical capacity to more fully engage with technologists and understand more fully the implications of their decisions.

At the same time that tech companies seem unwilling or unable to rein in their creations, many also fear they wield too much power, in some cases all but replacing governments and international organizations in their ability to make decisions that affect millions of people worldwide and control access to information, platforms, and audiences (Kilovaty 2020) . Regulators around the world have begun considering whether some of these companies have become so powerful that they violate the tenets of antitrust laws, but it can be difficult for governments to identify exactly what those violations are, especially in the context of an industry where the largest players often provide their customers with free services. And the platforms and services developed by tech companies are often wielded most powerfully and dangerously not directly by their private-sector creators and operators but instead by states themselves for widespread misinformation campaigns that serve political purposes (Nye 2018) .

Since the largest private entities in the tech sector operate in many countries, they are often better poised to implement global changes to the technological ecosystem than individual states or regulatory bodies, creating new challenges to existing governance structures and hierarchies. Just as it can be challenging to provide oversight for government use of technologies, so, too, oversight of the biggest tech companies, which have more resources, reach, and power than many nations, can prove to be a daunting task. The rise of network forms of organization and the growing gig economy have added to these challenges, making it even harder for regulators to fully address the breadth of these companies’ operations (Powell 1990) . The private-public partnerships that have emerged around energy, transportation, medical, and cyber technologies further complicate this picture, blurring the line between the public and private sectors and raising critical questions about the role of each in providing critical infrastructure, health care, and security. How can and should private tech companies operating in these different sectors be governed, and what types of influence do they exert over regulators? How feasible are different policy proposals aimed at technological innovation, and what potential unintended consequences might they have?

Conflict between countries has also spilled over significantly into the private sector in recent years, most notably in the case of tensions between the United States and China over which technologies developed in each country will be permitted by the other and which will be purchased by other customers, outside those two countries. Countries competing to develop the best technology is not a new phenomenon, but the current conflicts have major international ramifications and will influence the infrastructure that is installed and used around the world for years to come. Untangling the different factors that feed into these tussles as well as whom they benefit and whom they leave at a disadvantage is crucial for understanding how governments can most effectively foster technological innovation and invention domestically as well as the global consequences of those efforts. As much of the world is forced to choose between buying technology from the United States or from China, how should we understand the long-term impacts of those choices and the options available to people in countries without robust domestic tech industries? Does the global spread of technologies help fuel further innovation in countries with smaller tech markets, or does it reinforce the dominance of the states that are already most prominent in this sector? How can research universities maintain global collaborations and research communities in light of these national competitions, and what role does government research and development spending play in fostering innovation within its own borders and worldwide? How should intellectual property protections evolve to meet the demands of the technology industry, and how can those protections be enforced globally?

These conflicts between countries sometimes appear to challenge the feasibility of truly global technologies and networks that operate across all countries through standardized protocols and design features. Organizations like the International Organization for Standardization, the World Intellectual Property Organization, the United Nations Industrial Development Organization, and many others have tried to harmonize these policies and protocols across different countries for years, but have met with limited success when it comes to resolving the issues of greatest tension and disagreement among nations. For technology to operate in a global environment, there is a need for a much greater degree of coordination among countries and the development of common standards and norms, but governments continue to struggle to agree not just on those norms themselves but even the appropriate venue and processes for developing them. Without greater global cooperation, is it possible to maintain a global network like the internet or to promote the spread of new technologies around the world to address challenges of sustainability? What might help incentivize that cooperation moving forward, and what could new structures and process for governance of global technologies look like? Why has the tech industry’s self-regulation culture persisted? Do the same traditional drivers for public policy, such as politics of harmonization and path dependency in policy-making, still sufficiently explain policy outcomes in this space? As new technologies and their applications spread across the globe in uneven ways, how and when do they create forces of change from unexpected places?

These are some of the questions that we hope to address in the Technology and Global Change section through articles that tackle new dimensions of the global landscape of designing, developing, deploying, and assessing new technologies to address major challenges the world faces. Understanding these processes requires synthesizing knowledge from a range of different fields, including sociology, political science, economics, and history, as well as technical fields such as engineering, climate science, and computer science. A crucial part of understanding how technology has created global change and, in turn, how global changes have influenced the development of new technologies is understanding the technologies themselves in all their richness and complexity—how they work, the limits of what they can do, what they were designed to do, how they are actually used. Just as technologies themselves are becoming more complicated, so are their embeddings and relationships to the larger social, political, and legal contexts in which they exist. Scholars across all disciplines are encouraged to join us in untangling those complexities.

Josephine Wolff is an associate professor of cybersecurity policy at the Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy at Tufts University. Her book You’ll See This Message When It Is Too Late: The Legal and Economic Aftermath of Cybersecurity Breaches was published by MIT Press in 2018.

Recipient(s) will receive an email with a link to 'How Is Technology Changing the World, and How Should the World Change Technology?' and will not need an account to access the content.

Subject: How Is Technology Changing the World, and How Should the World Change Technology?

(Optional message may have a maximum of 1000 characters.)

Citing articles via

Email alerts, affiliations.

- Special Collections

- Review Symposia

- Info for Authors

- Info for Librarians

- Editorial Team

- Emerging Scholars Forum

- Open Access

- Online ISSN 2575-7350

- Copyright © 2024 The Regents of the University of California. All Rights Reserved.

Stay Informed

Disciplines.

- Ancient World

- Anthropology

- Communication

- Criminology & Criminal Justice

- Film & Media Studies

- Food & Wine

- Browse All Disciplines

- Browse All Courses

- Book Authors

- Booksellers

- Instructions

- Journal Authors

- Journal Editors

- Media & Journalists

- Planned Giving

About UC Press

- Press Releases

- Seasonal Catalog

- Acquisitions Editors

- Customer Service

- Exam/Desk Requests

- Media Inquiries

- Print-Disability

- Rights & Permissions

- UC Press Foundation

- © Copyright 2024 by the Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Privacy policy Accessibility

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

Suggestions or feedback?

MIT News | Massachusetts Institute of Technology

- Machine learning

- Social justice

- Black holes

- Classes and programs

Departments

- Aeronautics and Astronautics

- Brain and Cognitive Sciences

- Architecture

- Political Science

- Mechanical Engineering

Centers, Labs, & Programs

- Abdul Latif Jameel Poverty Action Lab (J-PAL)

- Picower Institute for Learning and Memory

- Lincoln Laboratory

- School of Architecture + Planning

- School of Engineering

- School of Humanities, Arts, and Social Sciences

- Sloan School of Management

- School of Science

- MIT Schwarzman College of Computing

A comprehensive study of technological change

Press contact :.

Previous image Next image

The societal impacts of technological change can be seen in many domains, from messenger RNA vaccines and automation to drones and climate change. The pace of that technological change can affect its impact, and how quickly a technology improves in performance can be an indicator of its future importance. For decision-makers like investors, entrepreneurs, and policymakers, predicting which technologies are fast improving (and which are overhyped) can mean the difference between success and failure.

New research from MIT aims to assist in the prediction of technology performance improvement using U.S. patents as a dataset. The study describes 97 percent of the U.S. patent system as a set of 1,757 discrete technology domains, and quantitatively assesses each domain for its improvement potential.

“The rate of improvement can only be empirically estimated when substantial performance measurements are made over long time periods,” says Anuraag Singh SM ’20, lead author of the paper. “In some large technological fields, including software and clinical medicine, such measures have rarely, if ever, been made.”

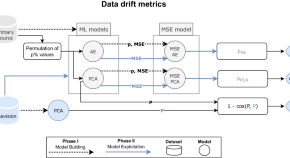

A previous MIT study provided empirical measures for 30 technological domains, but the patent sets identified for those technologies cover less than 15 percent of the patents in the U.S. patent system. The major purpose of this new study is to provide predictions of the performance improvement rates for the thousands of domains not accessed by empirical measurement. To accomplish this, the researchers developed a method using a new probability-based algorithm, machine learning, natural language processing, and patent network analytics.

Overlap and centrality

A technology domain, as the researchers define it, consists of sets of artifacts fulfilling a specific function using a specific branch of scientific knowledge. To find the patents that best represent a domain, the team built on previous research conducted by co-author Chris Magee, a professor of the practice of engineering systems within the Institute for Data, Systems, and Society (IDSS). Magee and his colleagues found that by looking for patent overlap between the U.S. and international patent-classification systems, they could quickly identify patents that best represent a technology. The researchers ultimately created a correspondence of all patents within the U.S. patent system to a set of 1,757 technology domains.

To estimate performance improvement, Singh employed a method refined by co-authors Magee and Giorgio Triulzi, a researcher with the Sociotechnical Systems Research Center (SSRC) within IDSS and an assistant professor at Universidad de los Andes in Colombia. Their method is based on the average “centrality” of patents in the patent citation network. Centrality refers to multiple criteria for determining the ranking or importance of nodes within a network.

“Our method provides predictions of performance improvement rates for nearly all definable technologies for the first time,” says Singh.

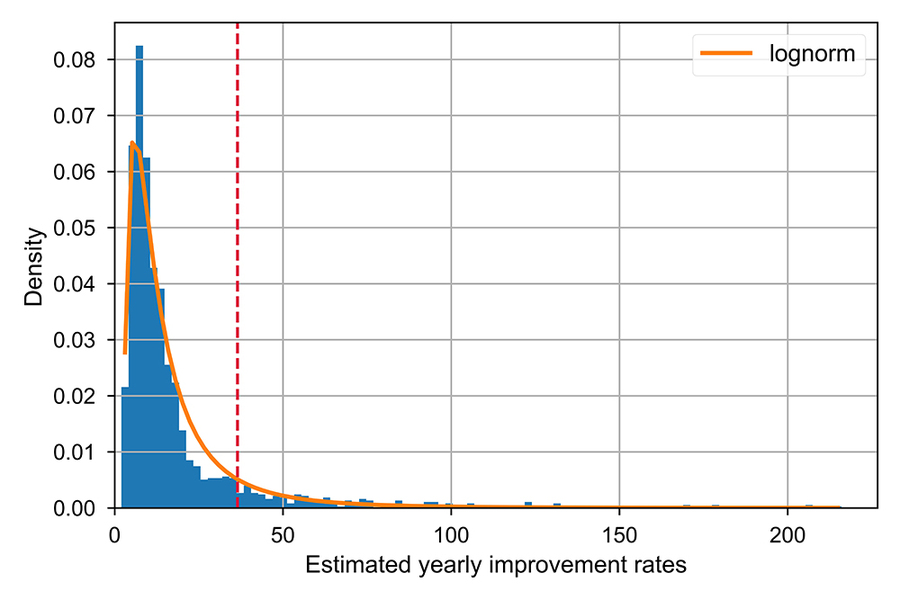

Those rates vary — from a low of 2 percent per year for the “Mechanical skin treatment — Hair removal and wrinkles” domain to a high of 216 percent per year for the “Dynamic information exchange and support systems integrating multiple channels” domain. The researchers found that most technologies improve slowly; more than 80 percent of technologies improve at less than 25 percent per year. Notably, the number of patents in a technological area was not a strong indicator of a higher improvement rate.

“Fast-improving domains are concentrated in a few technological areas,” says Magee. “The domains that show improvement rates greater than the predicted rate for integrated chips — 42 percent, from Moore’s law — are predominantly based upon software and algorithms.”

TechNext Inc.

The researchers built an online interactive system where domains corresponding to technology-related keywords can be found along with their improvement rates. Users can input a keyword describing a technology and the system returns a prediction of improvement for the technological domain, an automated measure of the quality of the match between the keyword and the domain, and patent sets so that the reader can judge the semantic quality of the match.

Moving forward, the researchers have founded a new MIT spinoff called TechNext Inc. to further refine this technology and use it to help leaders make better decisions, from budgets to investment priorities to technology policy. Like any inventors, Magee and his colleagues want to protect their intellectual property rights. To that end, they have applied for a patent for their novel system and its unique methodology.

“Technologies that improve faster win the market,” says Singh. “Our search system enables technology managers, investors, policymakers, and entrepreneurs to quickly look up predictions of improvement rates for specific technologies.”

Adds Magee: “Our goal is to bring greater accuracy, precision, and repeatability to the as-yet fuzzy art of technology forecasting.”

Share this news article on:

Related links.

- Sociotechnical Systems Research Center

- Institute for Data, Systems, and Society (IDSS)

Related Topics

- Technology and society

- Innovation and Entrepreneurship (I&E)

Related Articles

Shaping technology’s future

Tackling society’s big problems with systems theory

Patents forecast technological change

Previous item Next item

More MIT News

Four MIT faculty named 2023 AAAS Fellows

Read full story →

For more open and equitable public discussions on social media, try “meronymity”

Erin Kara named Edgerton Award winner

Q&A: Claire Walsh on how J-PAL’s King Climate Action Initiative tackles the twin climate and poverty crises

Knight Science Journalism Program launches HBCU Science Journalism Fellowship

Plant sensors could act as an early warning system for farmers

- More news on MIT News homepage →

Massachusetts Institute of Technology 77 Massachusetts Avenue, Cambridge, MA, USA

- Map (opens in new window)

- Events (opens in new window)

- People (opens in new window)

- Careers (opens in new window)

- Accessibility

- Social Media Hub

- MIT on Facebook

- MIT on YouTube

- MIT on Instagram

- Review article

- Open access

- Published: 02 October 2017

Computer-based technology and student engagement: a critical review of the literature

- Laura A. Schindler ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-8730-5189 1 ,

- Gary J. Burkholder 2 , 3 ,

- Osama A. Morad 1 &

- Craig Marsh 4

International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education volume 14 , Article number: 25 ( 2017 ) Cite this article

383k Accesses

137 Citations

39 Altmetric

Metrics details

Computer-based technology has infiltrated many aspects of life and industry, yet there is little understanding of how it can be used to promote student engagement, a concept receiving strong attention in higher education due to its association with a number of positive academic outcomes. The purpose of this article is to present a critical review of the literature from the past 5 years related to how web-conferencing software, blogs, wikis, social networking sites ( Facebook and Twitter ), and digital games influence student engagement. We prefaced the findings with a substantive overview of student engagement definitions and indicators, which revealed three types of engagement (behavioral, emotional, and cognitive) that informed how we classified articles. Our findings suggest that digital games provide the most far-reaching influence across different types of student engagement, followed by web-conferencing and Facebook . Findings regarding wikis, blogs, and Twitter are less conclusive and significantly limited in number of studies conducted within the past 5 years. Overall, the findings provide preliminary support that computer-based technology influences student engagement, however, additional research is needed to confirm and build on these findings. We conclude the article by providing a list of recommendations for practice, with the intent of increasing understanding of how computer-based technology may be purposefully implemented to achieve the greatest gains in student engagement.

Introduction

The digital revolution has profoundly affected daily living, evident in the ubiquity of mobile devices and the seamless integration of technology into common tasks such as shopping, reading, and finding directions (Anderson, 2016 ; Smith & Anderson, 2016 ; Zickuhr & Raine, 2014 ). The use of computers, mobile devices, and the Internet is at its highest level to date and expected to continue to increase as technology becomes more accessible, particularly for users in developing countries (Poushter, 2016 ). In addition, there is a growing number of people who are smartphone dependent, relying solely on smartphones for Internet access (Anderson & Horrigan, 2016 ) rather than more expensive devices such as laptops and tablets. Greater access to and demand for technology has presented unique opportunities and challenges for many industries, some of which have thrived by effectively digitizing their operations and services (e.g., finance, media) and others that have struggled to keep up with the pace of technological innovation (e.g., education, healthcare) (Gandhi, Khanna, & Ramaswamy, 2016 ).

Integrating technology into teaching and learning is not a new challenge for universities. Since the 1900s, administrators and faculty have grappled with how to effectively use technical innovations such as video and audio recordings, email, and teleconferencing to augment or replace traditional instructional delivery methods (Kaware & Sain, 2015 ; Westera, 2015 ). Within the past two decades, however, this challenge has been much more difficult due to the sheer volume of new technologies on the market. For example, in the span of 7 years (from 2008 to 2015), the number of active apps in Apple’s App Store increased from 5000 to 1.75 million. Over the next 4 years, the number of apps is projected to rise by 73%, totaling over 5 million (Nelson, 2016 ). Further compounding this challenge is the limited shelf life of new devices and software combined with significant internal organizational barriers that hinder universities from efficiently and effectively integrating new technologies (Amirault, 2012 ; Kinchin, 2012 ; Linder-VanBerschot & Summers 2015 ; Westera, 2015 ).

Many organizational barriers to technology integration arise from competing tensions between institutional policy and practice and faculty beliefs and abilities. For example, university administrators may view technology as a tool to attract and retain students, whereas faculty may struggle to determine how technology coincides with existing pedagogy (Lawrence & Lentle-Keenan, 2013 ; Lin, Singer, & Ha, 2010 ). In addition, some faculty may be hesitant to use technology due to lack of technical knowledge and/or skepticism about the efficacy of technology to improve student learning outcomes (Ashrafzadeh & Sayadian, 2015 ; Buchanan, Sainter, & Saunders, 2013 ; Hauptman, 2015 ; Johnson, 2013 ; Kidd, Davis, & Larke, 2016 ; Kopcha, Rieber, & Walker, 2016 ; Lawrence & Lentle-Keenan, 2013 ; Lewis, Fretwell, Ryan, & Parham, 2013 ; Reid, 2014 ). Organizational barriers to technology adoption are particularly problematic given the growing demands and perceived benefits among students about using technology to learn (Amirault, 2012 ; Cassidy et al., 2014 ; Gikas & Grant, 2013 ; Paul & Cochran, 2013 ). Surveys suggest that two-thirds of students use mobile devices for learning and believe that technology can help them achieve learning outcomes and better prepare them for a workforce that is increasingly dependent on technology (Chen, Seilhamer, Bennett, & Bauer, 2015 ; Dahlstrom, 2012 ). Universities that fail to effectively integrate technology into the learning experience miss opportunities to improve student outcomes and meet the expectations of a student body that has grown accustomed to the integration of technology into every facet of life (Amirault, 2012 ; Cook & Sonnenberg, 2014 ; Revere & Kovach, 2011 ; Sun & Chen, 2016 ; Westera, 2015 ).

The purpose of this paper is to provide a literature review on how computer-based technology influences student engagement within higher education settings. We focused on computer-based technology given the specific types of technologies (i.e., web-conferencing software, blogs, wikis, social networking sites, and digital games) that emerged from a broad search of the literature, which is described in more detail below. Computer-based technology (hereafter referred to as technology) requires the use of specific hardware, software, and micro processing features available on a computer or mobile device. We also focused on student engagement as the dependent variable of interest because it encompasses many different aspects of the teaching and learning process (Bryson & Hand, 2007 ; Fredricks, Blumenfeld, & Parks, 1994; Wimpenny & Savin-Baden, 2013 ), compared narrower variables in the literature such as final grades or exam scores. Furthermore, student engagement has received significant attention over the past several decades due to shifts towards student-centered, constructivist instructional methods (Haggis, 2009 ; Wright, 2011 ), mounting pressures to improve teaching and learning outcomes (Axelson & Flick, 2011 ; Kuh, 2009 ), and promising studies suggesting relationships between student engagement and positive academic outcomes (Carini, Kuh, & Klein, 2006 ; Center for Postsecondary Research, 2016 ; Hu & McCormick, 2012 ). Despite the interest in student engagement and the demand for more technology in higher education, there are no articles offering a comprehensive review of how these two variables intersect. Similarly, while many existing student engagement conceptual models have expanded to include factors that influence student engagement, none highlight the overt role of technology in the engagement process (Kahu, 2013 ; Lam, Wong, Yang, & Yi, 2012 ; Nora, Barlow, & Crisp, 2005 ; Wimpenny & Savin-Baden, 2013 ; Zepke & Leach, 2010 ).

Our review aims to address existing gaps in the student engagement literature and seeks to determine whether student engagement models should be expanded to include technology. The review also addresses some of the organizational barriers to technology integration (e.g., faculty uncertainty and skepticism about technology) by providing a comprehensive account of the research evidence regarding how technology influences student engagement. One limitation of the literature, however, is the lack of detail regarding how teaching and learning practices were used to select and integrate technology into learning. For example, the methodology section of many studies does not include a pedagogical justification for why a particular technology was used or details about the design of the learning activity itself. Therefore, it often is unclear how teaching and learning practices may have affected student engagement levels. We revisit this issue in more detail at the end of this paper in our discussions of areas for future research and recommendations for practice. We initiated our literature review by conducting a broad search for articles published within the past 5 years, using the key words technology and higher education , in Google Scholar and the following research databases: Academic Search Complete, Communication & Mass Media Complete, Computers & Applied Sciences Complete, Education Research Complete, ERIC, PsycARTICLES, and PsycINFO . Our initial search revealed themes regarding which technologies were most prevalent in the literature (e.g., social networking, digital games), which then lead to several, more targeted searches of the same databases using specific keywords such as Facebook and student engagement. After both broad and targeted searches, we identified five technologies (web-conferencing software, blogs, wikis, social networking sites, and digital games) to include in our review.

We chose to focus on technologies for which there were multiple studies published, allowing us to identify areas of convergence and divergence in the literature and draw conclusions about positive and negative effects on student engagement. In total, we identified 69 articles relevant to our review, with 36 pertaining to social networking sites (21 for Facebook and 15 for Twitter ), 14 pertaining to digital games, seven pertaining to wikis, and six pertaining to blogs and web-conferencing software respectively. Articles were categorized according to their influence on specific types of student engagement, which will be described in more detail below. In some instances, one article pertained to multiple types of engagement. In the sections that follow, we will provide an overview of student engagement, including an explanation of common definitions and indicators of engagement, followed by a synthesis of how each type of technology influences student engagement. Finally, we will discuss areas for future research and make recommendations for practice.

- Student engagement

Interest in student engagement began over 70 years ago with Ralph Tyler’s research on the relationship between time spent on coursework and learning (Axelson & Flick, 2011 ; Kuh, 2009 ). Since then, the study of student engagement has evolved and expanded considerably, through the seminal works of Pace ( 1980 ; 1984 ) and Astin ( 1984 ) about how quantity and quality of student effort affect learning and many more recent studies on the environmental conditions and individual dispositions that contribute to student engagement (Bakker, Vergel, & Kuntze, 2015 ; Gilboy, Heinerichs, & Pazzaglia, 2015 ; Martin, Goldwasser, & Galentino, 2017 ; Pellas, 2014 ). Perhaps the most well-known resource on student engagement is the National Survey of Student Engagement (NSSE), an instrument designed to assess student participation in various educational activities (Kuh, 2009 ). The NSSE and other engagement instruments like it have been used in many studies that link student engagement to positive student outcomes such as higher grades, retention, persistence, and completion (Leach, 2016 ; McClenney, Marti, & Adkins, 2012 ; Trowler & Trowler, 2010 ), further convincing universities that student engagement is an important factor in the teaching and learning process. However, despite the increased interest in student engagement, its meaning is generally not well understood or agreed upon.

Student engagement is a broad and complex phenomenon for which there are many definitions grounded in psychological, social, and/or cultural perspectives (Fredricks et al., 1994; Wimpenny & Savin-Baden, 2013 ; Zepke & Leach, 2010 ). Review of definitions revealed that student engagement is defined in two ways. One set of definitions refer to student engagement as a desired outcome reflective of a student’s thoughts, feelings, and behaviors about learning. For example, Kahu ( 2013 ) defines student engagement as an “individual psychological state” that includes a student’s affect, cognition, and behavior (p. 764). Other definitions focus primarily on student behavior, suggesting that engagement is the “extent to which students are engaging in activities that higher education research has shown to be linked with high-quality learning outcomes” (Krause & Coates, 2008 , p. 493) or the “quality of effort and involvement in productive learning activities” (Kuh, 2009 , p. 6). Another set of definitions refer to student engagement as a process involving both the student and the university. For example, Trowler ( 2010 ) defined student engagement as “the interaction between the time, effort and other relevant resources invested by both students and their institutions intended to optimize the student experience and enhance the learning outcomes and development of students and the performance, and reputation of the institution” (p. 2). Similarly, the NSSE website indicates that student engagement is “the amount of time and effort students put into their studies and other educationally purposeful activities” as well as “how the institution deploys its resources and organizes the curriculum and other learning opportunities to get students to participate in activities that decades of research studies show are linked to student learning” (Center for Postsecondary Research, 2017 , para. 1).

Many existing models of student engagement reflect the latter set of definitions, depicting engagement as a complex, psychosocial process involving both student and university characteristics. Such models organize the engagement process into three areas: factors that influence student engagement (e.g., institutional culture, curriculum, and teaching practices), indicators of student engagement (e.g., interest in learning, interaction with instructors and peers, and meaningful processing of information), and outcomes of student engagement (e.g., academic achievement, retention, and personal growth) (Kahu, 2013 ; Lam et al., 2012 ; Nora et al., 2005 ). In this review, we examine the literature to determine whether technology influences student engagement. In addition, we will use Fredricks et al. ( 2004 ) typology of student engagement to organize and present research findings, which suggests that there are three types of engagement (behavioral, emotional, and cognitive). The typology is useful because it is broad in scope, encompassing different types of engagement that capture a range of student experiences, rather than narrower typologies that offer specific or prescriptive conceptualizations of student engagement. In addition, this typology is student-centered, focusing exclusively on student-focused indicators rather than combining student indicators with confounding variables, such as faculty behavior, curriculum design, and campus environment (Coates, 2008 ; Kuh, 2009 ). While such variables are important in the discussion of student engagement, perhaps as factors that may influence engagement, they are not true indicators of student engagement. Using the typology as a guide, we examined recent student engagement research, models, and measures to gain a better understanding of how behavioral, emotional, and cognitive student engagement are conceptualized and to identify specific indicators that correspond with each type of engagement, as shown in Fig. 1 .

Conceptual framework of types and indicators of student engagement

Behavioral engagement is the degree to which students are actively involved in learning activities (Fredricks et al., 2004 ; Kahu, 2013 ; Zepke, 2014 ). Indicators of behavioral engagement include time and effort spent participating in learning activities (Coates, 2008 ; Fredricks et al., 2004 ; Kahu, 2013 ; Kuh, 2009 ; Lam et al., 2012 ; Lester, 2013 ; Trowler, 2010 ) and interaction with peers, faculty, and staff (Coates, 2008 ; Kahu, 2013 ; Kuh, 2009 ; Bryson & Hand, 2007 ; Wimpenny & Savin-Baden, 2013 : Zepke & Leach, 2010 ). Indicators of behavioral engagement reflect observable student actions and most closely align with Pace ( 1980 ) and Astin’s ( 1984 ) original conceptualizations of student engagement as quantity and quality of effort towards learning. Emotional engagement is students’ affective reactions to learning (Fredricks et al., 2004 ; Lester, 2013 ; Trowler, 2010 ). Indicators of emotional engagement include attitudes, interests, and values towards learning (Fredricks et al., 2004 ; Kahu, 2013 ; Lester, 2013 ; Trowler, 2010 ; Wimpenny & Savin-Baden, 2013 ; Witkowski & Cornell, 2015 ) and a perceived sense of belonging within a learning community (Fredricks et al., 2004 ; Kahu, 2013 ; Lester, 2013 ; Trowler, 2010 ; Wimpenny & Savin-Baden, 2013 ). Emotional engagement often is assessed using self-report measures (Fredricks et al., 2004 ) and provides insight into how students feel about a particular topic, delivery method, or instructor. Finally, cognitive engagement is the degree to which students invest in learning and expend mental effort to comprehend and master content (Fredricks et al., 2004 ; Lester, 2013 ). Indicators of cognitive engagement include: motivation to learn (Lester, 2013 ; Richardson & Newby, 2006 ; Zepke & Leach, 2010 ); persistence to overcome academic challenges and meet/exceed requirements (Fredricks et al., 2004 ; Kuh, 2009 ; Trowler, 2010 ); and deep processing of information (Fredricks et al., 2004 ; Kahu, 2013 ; Lam et al., 2012 ; Richardson & Newby, 2006 ) through critical thinking (Coates, 2008 ; Witkowski & Cornell, 2015 ), self-regulation (e.g., set goals, plan, organize study effort, and monitor learning; Fredricks et al., 2004 ; Lester, 2013 ), and the active construction of knowledge (Coates, 2008 ; Kuh, 2009 ). While cognitive engagement includes motivational aspects, much of the literature focuses on how students use active learning and higher-order thinking, in some form, to achieve content mastery. For example, there is significant emphasis on the importance of deep learning, which involves analyzing new learning in relation previous knowledge, compared to surface learning, which is limited to memorization, recall, and rehearsal (Fredricks et al., 2004 ; Kahu, 2013 ; Lam et al., 2012 ).

While each type of engagement has distinct features, there is some overlap across cognitive, behavioral, and emotional domains. In instances where an indicator could correspond with more than one type of engagement, we chose to match the indicator to the type of engagement that most closely aligned, based on our review of the engagement literature and our interpretation of the indicators. Similarly, there is also some overlap among indicators. As a result, we combined and subsumed similar indicators found in the literature, where appropriate, to avoid redundancy. Achieving an in-depth understanding of student engagement and associated indicators was an important pre-cursor to our review of the technology literature. Very few articles used the term student engagement as a dependent variable given the concept is so broad and multidimensional. We found that specific indicators (e.g., interaction, sense of belonging, and knowledge construction) of student engagement were more common in the literature as dependent variables. Next, we will provide a synthesis of the findings regarding how different types of technology influence behavioral, emotional, and cognitive student engagement and associated indicators.

Influence of technology on student engagement

We identified five technologies post-literature search (i.e., web-conferencing, blogs, wikis, social networking sites , and digital games) to include in our review, based on frequency in which they appeared in the literature over the past 5 years. One commonality among these technologies is their potential value in supporting a constructivist approach to learning, characterized by the active discovery of knowledge through reflection of experiences with one’s environment, the connection of new knowledge to prior knowledge, and interaction with others (Boghossian, 2006 ; Clements, 2015 ). Another commonality is that most of the technologies, except perhaps for digital games, are designed primarily to promote interaction and collaboration with others. Our search yielded very few studies on how informational technologies, such as video lectures and podcasts, influence student engagement. Therefore, these technologies are notably absent from our review. Unlike the technologies we identified earlier, informational technologies reflect a behaviorist approach to learning in which students are passive recipients of knowledge that is transmitted from an expert (Boghossian, 2006 ). The lack of recent research on how informational technologies affect student engagement may be due to the increasing shift from instructor-centered, behaviorist approaches to student-centered, constructivist approaches within higher education (Haggis, 2009 ; Wright, 2011 ) along with the ubiquity of web 2.0 technologies.

- Web-conferencing

Web-conferencing software provides a virtual meeting space where users login simultaneously and communicate about a given topic. While each software application is unique, many share similar features such as audio, video, or instant messaging options for real-time communication; screen sharing, whiteboards, and digital pens for presentations and demonstrations; polls and quizzes for gauging comprehension or eliciting feedback; and breakout rooms for small group work (Bower, 2011 ; Hudson, Knight, & Collins, 2012 ; Martin, Parker, & Deale, 2012 ; McBrien, Jones, & Cheng, 2009 ). Of the technologies included in this literature review, web-conferencing software most closely mimics the face-to-face classroom environment, providing a space where instructors and students can hear and see each other in real-time as typical classroom activities (i.e., delivering lectures, discussing course content, asking/answering questions) are carried out (Francescucci & Foster, 2013 ; Hudson et al., 2012 ). Studies on web-conferencing software deployed Adobe Connect, Cisco WebEx, Horizon Wimba, or Blackboard Collaborate and made use of multiple features, such as screen sharing, instant messaging, polling, and break out rooms. In addition, most of the studies integrated web-conferencing software into courses on a voluntary basis to supplement traditional instructional methods (Andrew, Maslin-Prothero, & Ewens, 2015 ; Armstrong & Thornton, 2012 ; Francescucci & Foster, 2013 ; Hudson et al., 2012 ; Martin et al., 2012 ; Wdowik, 2014 ). Existing studies on web-conferencing pertain to all three types of student engagement.

Studies on web-conferencing and behavioral engagement reveal mixed findings. For example, voluntary attendance in web-conferencing sessions ranged from 54 to 57% (Andrew et al., 2015 ; Armstrong & Thornton, 2012 ) and, in a comparison between a blended course with regular web-conferencing sessions and a traditional, face-to-face course, researchers found no significant difference in student attendance in courses. However, students in the blended course reported higher levels of class participation compared to students in the face-to-face course (Francescucci & Foster, 2013 ). These findings suggest while web-conferencing may not boost attendance, especially if voluntary, it may offer more opportunities for class participation, perhaps through the use of communication channels typically not available in a traditional, face-to-face course (e.g., instant messaging, anonymous polling). Studies on web-conferencing and interaction, another behavioral indicator, support this assertion. For example, researchers found that students use various features of web-conferencing software (e.g., polling, instant message, break-out rooms) to interact with peers and the instructor by asking questions, expressing opinions and ideas, sharing resources, and discussing academic content (Andrew et al., 2015 ; Armstrong & Thornton, 2012 ; Hudson et al., 2012 ; Martin et al., 2012 ; Wdowik, 2014 ).

Studies on web-conferencing and cognitive engagement are more conclusive than those for behavioral engagement, although are fewer in number. Findings suggest that students who participated in web-conferencing demonstrated critical reflection and enhanced learning through interactions with others (Armstrong & Thornton, 2012 ), higher-order thinking (e.g., problem-solving, synthesis, evaluation) in response to challenging assignments (Wdowik, 2014 ), and motivation to learn, particularly when using polling features (Hudson et al., 2012 ). There is only one study examining how web-conferencing affects emotional engagement, although it is positive suggesting that students who participated in web-conferences had higher levels of interest in course content than those who did not (Francescucci & Foster, 2013 ). One possible reason for the positive cognitive and emotional engagement findings may be that web-conferencing software provides many features that promote active learning. For example, whiteboards and breakout rooms provide opportunities for real-time, collaborative problem-solving activities and discussions. However, additional studies are needed to isolate and compare specific web-conferencing features to determine which have the greatest effect on student engagement.

A blog, which is short for Weblog, is a collection of personal journal entries, published online and presented chronologically, to which readers (or subscribers) may respond by providing additional commentary or feedback. In order to create a blog, one must compose content for an entry, which may include text, hyperlinks, graphics, audio, or video, publish the content online using a blogging application, and alert subscribers that new content is posted. Blogs may be informal and personal in nature or may serve as formal commentary in a specific genre, such as in politics or education (Coghlan et al., 2007 ). Fortunately, many blog applications are free, and many learning management systems (LMSs) offer a blogging feature that is seamlessly integrated into the online classroom. The ease of blogging has attracted attention from educators, who currently use blogs as an instructional tool for the expression of ideas, opinions, and experiences and for promoting dialogue on a wide range of academic topics (Garrity, Jones, VanderZwan, de la Rocha, & Epstein, 2014 ; Wang, 2008 ).

Studies on blogs show consistently positive findings for many of the behavioral and emotional engagement indicators. For example, students reported that blogs promoted interaction with others, through greater communication and information sharing with peers (Chu, Chan, & Tiwari, 2012 ; Ivala & Gachago, 2012 ; Mansouri & Piki, 2016 ), and analyses of blog posts show evidence of students elaborating on one another’s ideas and sharing experiences and conceptions of course content (Sharma & Tietjen, 2016 ). Blogs also contribute to emotional engagement by providing students with opportunities to express their feelings about learning and by encouraging positive attitudes about learning (Dos & Demir, 2013 ; Chu et al., 2012 ; Yang & Chang, 2012 ). For example, Dos and Demir ( 2013 ) found that students expressed prejudices and fears about specific course topics in their blog posts. In addition, Yang and Chang ( 2012 ) found that interactive blogging, where comment features were enabled, lead to more positive attitudes about course content and peers compared to solitary blogging, where comment features were disabled.

The literature on blogs and cognitive engagement is less consistent. Some studies suggest that blogs may help students engage in active learning, problem-solving, and reflection (Chawinga, 2017 ; Chu et al., 2012 ; Ivala & Gachago, 2012 ; Mansouri & Piki, 2016 ), while other studies suggest that students’ blog posts show very little evidence of higher-order thinking (Dos & Demir, 2013 ; Sharma & Tietjen, 2016 ). The inconsistency in findings may be due to the wording of blog instructions. Students may not necessarily demonstrate or engage in deep processing of information unless explicitly instructed to do so. Unfortunately, it is difficult to determine whether the wording of blog assignments contributed to the mixed results because many of the studies did not provide assignment details. However, studies pertaining to other technologies suggest that assignment wording that lacks specificity or requires low-level thinking can have detrimental effects on student engagement outcomes (Hou, Wang, Lin, & Chang, 2015 ; Prestridge, 2014 ). Therefore, blog assignments that are vague or require only low-level thinking may have adverse effects on cognitive engagement.

A wiki is a web page that can be edited by multiple users at once (Nakamaru, 2012 ). Wikis have gained popularity in educational settings as a viable tool for group projects where group members can work collaboratively to develop content (i.e., writings, hyperlinks, images, graphics, media) and keep track of revisions through an extensive versioning system (Roussinos & Jimoyiannis, 2013 ). Most studies on wikis pertain to behavioral engagement, with far fewer studies on cognitive engagement and none on emotional engagement. Studies pertaining to behavioral engagement reveal mixed results, with some showing very little enduring participation in wikis beyond the first few weeks of the course (Nakamaru, 2012 ; Salaber, 2014 ) and another showing active participation, as seen in high numbers of posts and edits (Roussinos & Jimoyiannis, 2013 ). The most notable difference between these studies is the presence of grading, which may account for the inconsistencies in findings. For example, in studies where participation was low, wikis were ungraded, suggesting that students may need extra motivation and encouragement to use wikis (Nakamaru, 2012 ; Salaber, 2014 ). Findings regarding the use of wikis for promoting interaction are also inconsistent. In some studies, students reported that wikis were useful for interaction, teamwork, collaboration, and group networking (Camacho, Carrión, Chayah, & Campos, 2016 ; Martínez, Medina, Albalat, & Rubió, 2013 ; Morely, 2012 ; Calabretto & Rao, 2011 ) and researchers found evidence of substantial collaboration among students (e.g., sharing ideas, opinions, and points of view) in wiki activity (Hewege & Perera, 2013 ); however, Miller, Norris, and Bookstaver ( 2012 ) found that only 58% of students reported that wikis promoted collegiality among peers. The findings in the latter study were unexpected and may be due to design flaws in the wiki assignments. For example, the authors noted that wiki assignments were not explicitly referred to in face-to-face classes; therefore, this disconnect may have prevented students from building on interactive momentum achieved during out-of-class wiki assignments (Miller et al., 2012 ).

Studies regarding cognitive engagement are limited in number but more consistent than those concerning behavioral engagement, suggesting that wikis promote high levels of knowledge construction (i.e., evaluation of arguments, the integration of multiple viewpoints, new understanding of course topics; Hewege & Perera, 2013 ), and are useful for reflection, reinforcing course content, and applying academic skills (Miller et al., 2012 ). Overall, there is mixed support for the use of wikis to promote behavioral engagement, although making wiki assignments mandatory and explicitly referring to wikis in class may help bolster participation and interaction. In addition, there is some support for using wikis to promote cognitive engagement, but additional studies are needed to confirm and expand on findings as well as explore the effect of wikis on emotional engagement.

Social networking sites

Social networking is “the practice of expanding knowledge by making connections with individuals of similar interests” (Gunawardena et al., 2009 , p. 4). Social networking sites, such as Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and LinkedIn, allow users to create and share digital content publicly or with others to whom they are connected and communicate privately through messaging features. Two of the most popular social networking sites in the educational literature are Facebook and Twitter (Camus, Hurt, Larson, & Prevost, 2016 ; Manca & Ranieri, 2013 ), which is consistent with recent statistics suggesting that both sites also are exceedingly popular among the general population (Greenwood, Perrin, & Duggan, 2016 ). In the sections that follow, we examine how both Facebook and Twitter influence different types of student engagement.

Facebook is a web-based service that allows users to create a public or private profile and invite others to connect. Users may build social, academic, and professional connections by posting messages in various media formats (i.e., text, pictures, videos) and commenting on, liking, and reacting to others’ messages (Bowman & Akcaoglu, 2014 ; Maben, Edwards, & Malone, 2014 ; Hou et al., 2015 ). Within an educational context, Facebook has often been used as a supplementary instructional tool to lectures or LMSs to support class discussions or develop, deliver, and share academic content and resources. Many instructors have opted to create private Facebook groups, offering an added layer of security and privacy because groups are not accessible to strangers (Bahati, 2015 ; Bowman & Akcaoglu, 2014 ; Clements, 2015 ; Dougherty & Andercheck, 2014 ; Esteves, 2012 ; Shraim, 2014 ; Maben et al., 2014 ; Manca & Ranieri, 2013 ; Naghdipour & Eldridge, 2016 ; Rambe, 2012 ). The majority of studies on Facebook address behavioral indicators of student engagement, with far fewer focusing on emotional or cognitive engagement.

Studies that examine the influence of Facebook on behavioral engagement focus both on participation in learning activities and interaction with peers and instructors. In most studies, Facebook activities were voluntary and participation rates ranged from 16 to 95%, with an average of rate of 47% (Bahati, 2015 ; Bowman & Akcaoglu, 2014 ; Dougherty & Andercheck, 2014 ; Fagioli, Rios-Aguilar, & Deil-Amen, 2015 ; Rambe, 2012 ; Staines & Lauchs, 2013 ). Participation was assessed by tracking how many students joined course- or university-specific Facebook groups (Bahati, 2015 ; Bowman & Akcaoglu, 2014 ; Fagioli et al., 2015 ), visited or followed course-specific Facebook pages (DiVall & Kirwin, 2012 ; Staines & Lauchs, 2013 ), or posted at least once in a course-specific Facebook page (Rambe, 2012 ). The lowest levels of participation (16%) arose from a study where community college students were invited to use the Schools App, a free application that connects students to their university’s private Facebook community. While the authors acknowledged that building an online community of college students is difficult (Fagioli et al., 2015 ), downloading the Schools App may have been a deterrent to widespread participation. In addition, use of the app was not tied to any specific courses or assignments; therefore, students may have lacked adequate incentive to use it. The highest level of participation (95%) in the literature arose from a study in which the instructor created a Facebook page where students could find or post study tips or ask questions. Followership to the page was highest around exams, when students likely had stronger motivations to access study tips and ask the instructor questions (DiVall & Kirwin, 2012 ). The wide range of participation in Facebook activities suggests that some students may be intrinsically motivated to participate, while other students may need some external encouragement. For example, Bahati ( 2015 ) found that when students assumed that a course-specific Facebook was voluntary, only 23% participated, but when the instructor confirmed that the Facebook group was, in fact, mandatory, the level of participation rose to 94%.

While voluntary participation in Facebook activities may be lower than desired or expected (Dyson, Vickers, Turtle, Cowan, & Tassone, 2015 ; Fagioli et al., 2015 ; Naghdipour & Eldridge, 2016 ; Rambe, 2012 ), students seem to have a clear preference for Facebook compared to other instructional tools (Clements, 2015 ; DiVall & Kirwin, 2012 ; Hurt et al., 2012 ; Hou et al., 2015 ; Kent, 2013 ). For example, in one study where an instructor shared course-related information in a Facebook group, in the LMS, and through email, the level of participation in the Facebook group was ten times higher than in email or the LMS (Clements, 2015 ). In other studies, class discussions held in Facebook resulted in greater levels of participation and dialogue than class discussions held in LMS discussion forums (Camus et al., 2016 ; Hurt et al., 2012 ; Kent, 2013 ). Researchers found that preference for Facebook over the university’s LMS is due to perceptions that the LMS is outdated and unorganized and reports that Facebook is more familiar, convenient, and accessible given that many students already visit the social networking site multiple times per day (Clements, 2015 ; Dougherty & Andercheck, 2014 ; Hurt et al., 2012 ; Kent, 2013 ). In addition, students report that Facebook helps them stay engaged in learning through collaboration and interaction with both peers and instructors (Bahati, 2015 ; Shraim, 2014 ), which is evident in Facebook posts where students collaborated to study for exams, consulted on technical and theoretical problem solving, discussed course content, exchanged learning resources, and expressed opinions as well as academic successes and challenges (Bowman & Akcaoglu, 2014 ; Dougherty & Andercheck, 2014 ; Esteves, 2012 Ivala & Gachago, 2012 ; Maben et al., 2014 ; Rambe, 2012 ; van Beynen & Swenson, 2016 ).

There is far less evidence in the literature about the use of Facebook for emotional and cognitive engagement. In terms of emotional engagement, studies suggest that students feel positively about being part of a course-specific Facebook group and that Facebook is useful for expressing feelings about learning and concerns for peers, through features such as the “like” button and emoticons (Bowman & Akcaoglu, 2014 ; Dougherty & Andercheck, 2014 ; Naghdipour & Eldridge, 2016 ). In addition, being involved in a course-specific Facebook group was positively related to students’ sense of belonging in the course (Dougherty & Andercheck, 2014 ). The research on cognitive engagement is less conclusive, with some studies suggesting that Facebook participation is related to academic persistence (Fagioli et al., 2015 ) and self-regulation (Dougherty & Andercheck, 2014 ) while other studies show low levels of knowledge construction in Facebook posts (Hou et al., 2015 ), particularly when compared to discussions held in the LMS. One possible reason may be because the LMS is associated with formal, academic interactions while Facebook is associated with informal, social interactions (Camus et al., 2016 ). While additional research is needed to confirm the efficacy of Facebook for promoting cognitive engagement, studies suggest that Facebook may be a viable tool for increasing specific behavioral and emotional engagement indicators, such as interactions with others and a sense of belonging within a learning community.

Twitter is a web-based service where subscribers can post short messages, called tweets, in real-time that are no longer than 140 characters in length. Tweets may contain hyperlinks to other websites, images, graphics, and/or videos and may be tagged by topic using the hashtag symbol before the designated label (e.g., #elearning). Twitter subscribers may “follow” other users and gain access to their tweets and also may “retweet” messages that have already been posted (Hennessy, Kirkpatrick, Smith, & Border, 2016 ; Osgerby & Rush, 2015 ; Prestridge, 2014 ; West, Moore, & Barry, 2015 ; Tiernan, 2014 ;). Instructors may use Twitter to post updates about the course, clarify expectations, direct students to additional learning materials, and encourage students to discuss course content (Bista, 2015 ; Williams & Whiting, 2016 ). Several of the studies on the use of Twitter included broad, all-encompassing measures of student engagement and produced mixed findings. For example, some studies suggest that Twitter increases student engagement (Evans, 2014 ; Gagnon, 2015 ; Junco, Heibergert, & Loken, 2011 ) while other studies suggest that Twitter has little to no influence on student engagement (Junco, Elavsky, & Heiberger, 2013 ; McKay, Sanko, Shekhter, & Birnbach, 2014 ). In both studies suggesting little to no influence on student engagement, Twitter use was voluntary and in one of the studies faculty involvement in Twitter was low, which may account for the negative findings (Junco et al., 2013 ; McKay et al., 2014 ). Conversely, in the studies that show positive findings, Twitter use was mandatory and often directly integrated with required assignments (Evans, 2014 ; Gagnon, 2015 ; Junco et al., 2011 ). Therefore, making Twitter use mandatory, increasing faculty involvement in Twitter, and integrating Twitter into assignments may help to increase student engagement.

Studies pertaining to specific behavioral student engagement indicators also reveal mixed findings. For example, in studies where course-related Twitter use was voluntary, 45-91% of students reported using Twitter during the term (Hennessy et al., 2016 ; Junco et al., 2013 ; Ross, Banow, & Yu, 2015 ; Tiernan, 2014 ; Williams & Whiting, 2016 ), but only 30-36% reported making contributions to the course-specific Twitter page (Hennessy et al., 2016 ; Tiernan, 2014 ; Ross et al., 2015 ; Williams & Whiting, 2016 ). The study that reported a 91% participation rate was unique because the course-specific Twitter page was accessible via a public link. Therefore, students who chose only to view the content (58%), rather than contribute to the page, did not have to create a Twitter account (Hennessy et al., 2016 ). The convenience of not having to create an account may be one reason for much higher participation rates. In terms of low participation rates, a lack of literacy, familiarity, and interest in Twitter , as well as a preference for Facebook , are cited as contributing factors (Bista, 2015 ; McKay et al., 2014 ; Mysko & Delgaty, 2015 ; Osgerby & Rush, 2015 ; Tiernan, 2014 ). However, when the use of Twitter was required and integrated into class discussions, the participation rate was 100% (Gagnon, 2015 ). Similarly, 46% of students in one study indicated that they would have been more motivated to participate in Twitter activities if they were graded (Osgerby & Rush, 2015 ), again confirming the power of extrinsic motivating factors.

Studies also show mixed results for the use of Twitter to promote interactions with peers and instructors. Researchers found that when instructors used Twitter to post updates about the course, ask and answer questions, and encourage students to tweet about course content, there was evidence of student-student and student-instructor interactions in tweets (Hennessy et al., 2016 ; Tiernan, 2014 ). Some students echoed these findings, suggesting that Twitter is useful for sharing ideas and resources, discussing course content, asking the instructor questions, and networking (Chawinga, 2017 ; Evans, 2014 ; Gagnon, 2015 ; Hennessy et al., 2016 ; Mysko & Delgaty, 2015 ; West et al., 2015 ) and is preferable over speaking aloud in class because it is more comfortable, less threatening, and more concise due to the 140 character limit (Gagnon, 2015 ; Mysko & Delgaty, 2015 ; Tiernan, 2014 ). Conversely, other students reported that Twitter was not useful for improving interaction because they viewed it predominately for social, rather than academic, interactions and they found the 140 character limit to be frustrating and restrictive. A theme among the latter studies was that a large proportion of the sample had never used Twitter before (Bista, 2015 ; McKay et al., 2014 ; Osgerby & Rush, 2015 ), which may have contributed to negative perceptions.

The literature on the use of Twitter for cognitive and emotional engagement is minimal but nonetheless promising in terms of promoting knowledge gains, the practical application of content, and a sense of belonging among users. For example, using Twitter to respond to questions that arose in lectures and tweet about course content throughout the term is associated with increased understanding of course content and application of knowledge (Kim et al., 2015 ; Tiernan, 2014 ; West et al., 2015 ). While the underlying mechanisms pertaining to why Twitter promotes an understanding of content and application of knowledge are not entirely clear, Tiernan ( 2014 ) suggests that one possible reason may be that Twitter helps to break down communication barriers, encouraging shy or timid students to participate in discussions that ultimately are richer in dialogue and debate. In terms of emotional engagement, students who participated in a large, class-specific Twitter page were more likely to feel a sense of community and belonging compared to those who did not participate because they could more easily find support from and share resources with other Twitter users (Ross et al., 2015 ). Despite the positive findings about the use of Twitter for cognitive and emotional engagement, more studies are needed to confirm existing results regarding behavioral engagement and target additional engagement indicators such as motivation, persistence, and attitudes, interests, and values about learning. In addition, given the strong negative perceptions of Twitter that still exist, additional studies are needed to confirm Twitter ’s efficacy for promoting different types of behavioral engagement among both novice and experienced Twitter users, particularly when compared to more familiar tools such as Facebook or LMS discussion forums.

- Digital games

Digital games are “applications using the characteristics of video and computer games to create engaging and immersive learning experiences for delivery of specified learning goals, outcomes and experiences” (de Freitas, 2006 , p. 9). Digital games often serve the dual purpose of promoting the achievement of learning outcomes while making learning fun by providing simulations of real-world scenarios as well as role play, problem-solving, and drill and repeat activities (Boyle et al., 2016 ; Connolly, Boyle, MacArthur, Hainey, & Boyle, 2012 ; Scarlet & Ampolos, 2013 ; Whitton, 2011 ). In addition, gamified elements, such as digital badges and leaderboards, may be integrated into instruction to provide additional motivation for completing assigned readings and other learning activities (Armier, Shepherd, & Skrabut, 2016 ; Hew, Huang, Chu, & Chiu, 2016 ). The pedagogical benefits of digital games are somewhat distinct from the other technologies addressed in this review, which are designed primarily for social interaction. While digital games may be played in teams or allow one player to compete against another, the focus of their design often is on providing opportunities for students to interact with academic content in a virtual environment through decision-making, problem-solving, and reward mechanisms. For example, a digital game may require students to adopt a role as CEO in a computer-simulated business environment, make decisions about a series of organizational issues, and respond to the consequences of those decisions. In this example and others, digital games use adaptive learning principles, where the learning environment is re-configured or modified in response to the actions and needs of students (Bower, 2016 ). Most of the studies on digital games focused on cognitive and emotional indicators of student engagement, in contrast to the previous technologies addressed in this review which primarily focused on behavioral indicators of engagement.

Existing studies provide support for the influence of digital games on cognitive engagement, through achieving a greater understanding of course content and demonstrating higher-order thinking skills (Beckem & Watkins, 2012 ; Farley, 2013 ; Ke, Xie, & Xie, 2016 ; Marriott, Tan, & Marriott, 2015 ), particularly when compared to traditional instructional methods, such as giving lectures or assigning textbook readings (Lu, Hallinger, & Showanasai, 2014 ; Siddique, Ling, Roberson, Xu, & Geng, 2013 ; Zimmermann, 2013 ). For example, in a study comparing courses that offered computer simulations of business challenges (e.g, implementing a new information technology system, managing a startup company, and managing a brand of medicine in a simulated market environment) and courses that did not, students in simulation-based courses reported higher levels of action-directed learning (i.e., connecting theory to practice in a business context) than students in traditional, non-simulation-based courses (Lu et al., 2014 ). Similarly, engineering students who participated in a car simulator game, which was designed to help students apply and reinforce the knowledge gained from lectures, demonstrated higher levels of critical thinking (i.e., analysis, evaluation) on a quiz than students who only attended lectures (Siddique et al., 2013 ).