Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

How to Write the Definition of Terms in Chapter 1 of a Thesis

Related Papers

Meta: Journal des traducteurs

Phaedra Royle

Rahmadi Nirwanto

The study is intended to describe the methods of defining terms found in the theses of the English Foreign Language (EFL) students of IAIN Palangka Raya. The method to be used is a mixed method, qualitative and quantitative. Quantitative approach was used to identify, describe the frequencies, and classify the methods of defining terms. In interpreting and explaining the types of method to be used, the writer used qualitative approach. In qualitative approach, data were described in the form of words and explanation. The findings show that there were two methods of defining terms, dictionary approach and athoritative reference.

Terminology

Blaise Nkwenti

Sead Spuzic

Eurasia Review

Mohamed Chtatou

Terminology is the field of lexicology (or the study of lexicon) that deals with specialized vocabularies and sets of terms related to particular fields (aviation terminology, medical terminology, stylistics, agriculture, etc.). Terminology as a new academic field is located at the boundary among linguistics, logic, theory of existence, information science and specialized areas of science and technology, and in the interdisciplinary area.

Erikas Kupciunas

During the past several decades, the theory of terminology has been a subject of debates in various circles. The views on terminology as a scientific discipline vary considerably. Currently, there are a number of treatments of this field and a number of debatable questions involved. Is terminology a science, or just a practice? does terminology have a status of separate scholarly discipline with its own theory or does it owe its theoretical assumptions to more consolidated disciplines?

Tomasz Michta

Chapter 1.1 of my book A Model for an English-Polish Systematic Dictionary of Chemical Terminology

Alia Channel

Claudia Dobrina

Practical Tools for Leaders and Teams

Terry Schmidt

RELATED PAPERS

Gunilla Dahlberg

armando trento

Zahoor Kaloo

Urban Education

Cynthia Brock

Regina Lucia Alves de Lima

Journal of Materials Science

Claudia Roman

Teksty Drugie

Katarzyna Bojarska

Md Abdullah Al Mamun

Experimental cell research

Yoshinobu Nakamura

Marisol Abascal

Julia Lembo

Muscle & Nerve

Ambreen Asad

Agronomy research

Laura Gabriela Cooper

Marine Biology

Ângela Alves

Heart, Lung and Circulation

Interactive cardiovascular and thoracic surgery

Maurizio Salati

Lokesh Tiwari

Turkish journal of internal medicine

MEHMET FATİH İNECİKLİ

Journal of Cutaneous Medicine and Surgery

Damian Lake

Scientific Data

Antonio Loforte

Cassava - Recent Updates on Food, Feed and Industry [Working Title]

robet asnawi

Enfermería nefrológica

Ramon Roca-Tey

kusum yadav

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

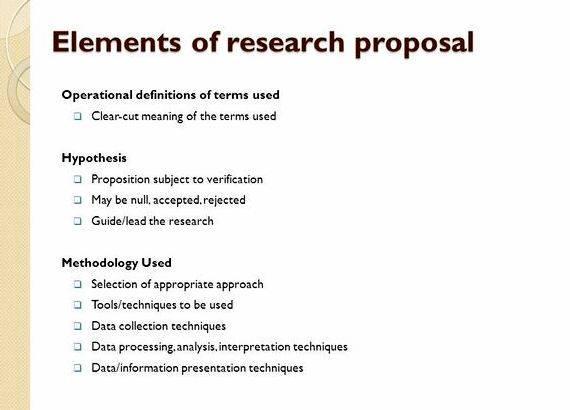

Operational Definition in Research

In addition to careful planning, one of the keys to successful research is the use of operational definitions in measuring the concepts and variables we are studying or the terms we are using in our research documents.

The operational definition is the specific way a variable is measured in a particular study.

It is critical to operationally define a variable to lend credibility to the methodology and ensure the reproducibility of the study’s results. Another study may identify the same variable differently, making it difficult to compare the results of these two studies.

To begin with, the operational definition is different from the dictionary definition, which is often conceptual, descriptive, and consequently imprecise.

In contrast, an operational definition gives an obvious, precise, and communicable meaning to a concept used to ensure comprehensive knowledge of the idea by specifying how the idea is measured and applied within a particular set of circumstances.

This definition highlights two important things about an operational definition:

- It gives a precise meaning to the spoken or written word, forming a ‘common language between two or more people.

- It defines how a term, word, or phrase is used when it is applied in a specific context. This implies that a word may have different meanings when used in different situations.

An operational definition must be valid, which implies that it should measure what it is supposed to measure. It must also be reliable, meaning that the results should be the same even when done by different people or by one person at different times.

An operational definition ensures a succinct description of concepts and terms applied to a specific situation to facilitate the collection of meaningful and standardized data.

When collecting data, it is important to define every term very clearly to assure all those who collect and analyze the data have the same understanding.

Therefore, operational definitions should be very precise and framed to avoid variation and confusion in interpretation.

Suppose, for example, we want to know whether a professional journal may be considered as a ‘standard journal’ or not. Here is a possible operational definition of a standard journal.

We set in advance that a journal is considered standard if

- It contains an ISSN number.

- It is officially published from a public or private university or from an internationally recognized research organization;

- It is peer-reviewed;

- It has a recognized editorial /advisory board;

- It is published on a regular basis at least once a year,

- It has an impact factor.

Thus, the researcher knows exactly what to look for when determining whether a published journal is standard or not.

The operational definition of literacy rate as adopted by the Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics (BBS) in their Vital Registration System is as follows:

“Percentage of the population of 7 years and above who can write a letter among the total population.”

In sum, an operational definition serves four purposes:

- It establishes the rules and procedures the researcher uses to measure the variable.

- It provides unambiguous and consistent meaning to terms/variables that can be interpreted differently.

- It makes the collection of data and analysis more focused and efficient.

- It guides what type of data and information we are looking for.

By operationally defining a variable, a researcher can communicate a common methodology to another researcher.

Operational definitions lay down the ground rules and procedures that the investigator will use to observe and record behavior and write down facts without bias.

The sole purpose of defining the variables operationally is to keep them unambiguous, thereby reducing errors.

How to operationalize a variable?

There is no hard and first rule for operationally defining a variable. Operational definitions may vary depending on your purpose and how you measure them.

Neither are there any universally accepted definitions of all the variables. A researcher can logically choose a definition of a variable that will serve his or her purpose.

Whenever possible, operational definitions used by others in their work of good standing could be used to compare the results.

Suppose a study classifies students according to their grades: A, B, C, etc. But the task is not easy if you must determine which students fall in which grade since there is seldom any universal rule for grades.

To do this, you need an operational definition.

In the goiter prevalence survey of 2004a person was classified as iodine deficient for a urinary iodine excretion (IUE) <100 pg/L and severely iodine-deficient for a urinary iodine excretion (IUE) <20 pg/L. One may choose a different threshold, too, in defining the iodine deficiency.

As another example, suppose it is intended to assess mothers’ knowledge of family planning. A set of 20 questions has been designed such that for every correct answer, a score of 1 will be given to the respondents.

Suppose further that we want to make 4 categories of knowledge: ‘no knowledge,’ ‘low knowledge,’ ‘medium knowledge,’ and ‘high knowledge.’ We decide to define these knowledge levels as follows:

One might, however, choose a different range of scores to define the knowledge levels.

Based on the body mass index (BMI), for example, the international health risk classification is operationally defined as follows

For the classification of nutritional status, internationally accepted categories already exist, which are based on the so-called NCHS/WHO standard growth curves. For the indicator ‘weight-for-age’, for example, children are assessed to be

- Well-nourished (normal) if they are above 80% of the standard.

- Moderately malnourished (moderate underweight) if they are between 60% and 80% of the standard.

- Severely malnourished (severely under-weight) if they are below 60% of the standard.

The nutritional status can also be classified based on the weight-for-age Z-score (WAZ) values. The Z- score of cut-off values are:

A farmer may be classified as landless, medium, and big, depending on his possession of landholding size. One such classification is as follows:

Similarly, a business firm may be classified as large, medium, or small in terms of its investment, capital, and a number of employees or assets, which may vary widely by the type of business firm.

In demographic research, a person may be categorized as a child, those who are under five years of age, adolescents in the age range 12-19, adults aged 20-65, and old aged 65 and over.

Not only that, but variables also need operationally defined. The terms that indicate the relationship between variables need to be defined.

For example, in many stated hypotheses, we use such terms as ‘frequent,’ ‘greater than,’ ‘less than,’ ‘significant,’ ‘higher than,’ ‘favorable,’ ‘different,’ ‘efficient,’ and the like.

These terms must be clearly and unambiguously defined so that they make sense and allow the researcher to measure the variables in question.

Consider the following hypothesis.

- Visits of Family Welfare Assistants will motivate the women resulting in significantly higher use of contraceptives.

‘Visit’ is the independent variable to which we might associate numbers 0, 1, and 2, to mean the frequency of visits made during a stipulated period. The term ‘higher use’ may mean a higher rate (dependent variable) than before.

This can be measured as the difference between the present and the past rate or between a post-test and a pretest measurement:

Difference =.Average CPR (pretest) – Average CPR (posttest)

But how much ‘higher’ will be regarded as significant? Thus the term’ significant’ needs to be defined clearly. We may decide to statistically verify at a 5% level with a probability of at least 95% that the difference in usage level is significant.

Thus, the operational definition of terms tells us the meaning of their use and the way of measuring the difference and testing its statistical significance, thereby accepting or rejecting the hypothesis.

In a study on the comparison of the performance of nationalized commercial banks (NCB) and private commercial banks (PCB) by Hasan (1995), one of the hypotheses was of the following form:

- PCBs are more efficient than NCBs in private deposit collection.

The term ‘more efficient’ was assessed by testing the statistical significance of the differences in the mean deposits of the two banks in question at a 5% level.

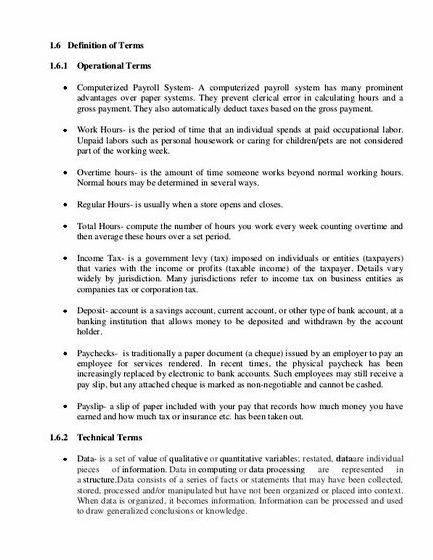

The concept of operational definition also applies to other technical terms that are not universally defined.

Here are some examples of such terms with their operational definitions:

Operational Definition of Terms

What is the primary purpose of an operational definition in research?

The primary purpose of an operational definition is to provide a clear, precise, and communicable meaning to a concept, ensuring comprehensive understanding by specifying how the concept is measured and applied within a specific set of circumstances.

How does an operational definition differ from a dictionary definition?

While a dictionary definition is often conceptual, descriptive, and may be imprecise, an operational definition offers a specific, clear, and applicable meaning to a term or concept when used in a particular context.

Why is it essential to operationally define a variable in research?

Operationally defining a variable is crucial to lend credibility to the research methodology , ensure reproducibility of the study’s results, and provide a common methodology for communication between researchers.

What are the key characteristics of a good operational definition?

A good operational definition should be valid (measuring what it’s supposed to measure), reliable (providing consistent results across different instances or by different people), precise, and framed to avoid variation and confusion in interpretation.

Can operational definitions vary between studies or researchers?

Yes, operational definitions can vary depending on the study’s purpose and how variables are measured. There are no universally accepted definitions for all variables, allowing researchers to choose definitions that best serve their objectives.

Why is it important to define terms when collecting data?

Defining terms clearly ensures that everyone involved in collecting and analyzing the data has the same understanding, making the data collection process more focused and efficient and reducing potential errors or misinterpretations.

How can operational definitions help in comparing results across different studies?

By providing clear and specific criteria for measuring variables, operational definitions allow for a standardized approach. If multiple studies use the same or similar operational definitions, it becomes easier to compare and contrast their results.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

STM1001 Topic 2B (Science and Health)

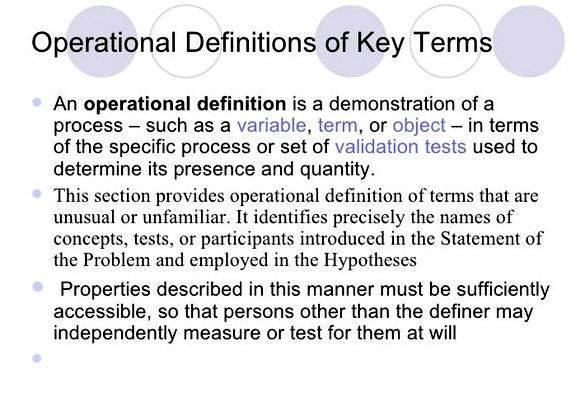

1.2 conceptual and operational definitions.

Research studies usually include terms that must be carefully and precisely defined, so that others know exactly what has been done and there are no ambiguities. Two types of definitions can be given: conceptual definitions and operational definitions .

Loosely speaking, a conceptual definition explains what to measure or observe (what a word or a term means for your study), and an operational definitions defines exactly how to measure or observe it.

For example, in a study of stress in students during a university semester, a conceptual definition would describe what is meant by 'stress'. An operational definition would describe how the 'stress' would be measured.

Sometimes the definitions themselves aren't important, provided a clear definition is given. Sometimes, commonly-accepted definitions exist, so should be used unless there is a good reason to use a different definition (for example, in criminal law, an 'adult' in Australia is someone aged 18 or over ).

Sometimes, a commonly-accepted definition does not exist, so the definition being used should be clearly articulated.

Example 1.2 (Operational and conceptual definitions) A student project at my university used this RQ:

Amongst students[...], on average do student who participate in competitive swimming have greater shoulder flexibility than the remainder of the able-bodied USC student population?

Example 1.3 (Operational and conceptual definitions) Players and fans have become more aware of concussions and head injuries in sport. A Conference on concussion in sport developed this conceptual definition ( McCrory et al. 2013 ) :

Concussion is a brain injury and is defined as a complex pathophysiological process affecting the brain, induced by biomechanical forces. Several common features that incorporate clinical, pathologic and biomechanical injury constructs that may be utilised in defining the nature of a concussive head injury include: Concussion may be caused either by a direct blow to the head, face, neck or elsewhere on the body with an "impulsive" force transmitted to the head. Concussion typically results in the rapid onset of short-lived impairment of neurological function that resolves spontaneously. However, in some cases, symptoms and signs may evolve over a number of minutes to hours. Concussion may result in neuropathological changes, but the acute clinical symptoms largely reflect a functional disturbance rather than a structural injury and, as such, no abnormality is seen on standard structural neuroimaging studies. Concussion results in a graded set of clinical symptoms that may or may not involve loss of consciousness. Resolution of the clinical and cognitive symptoms typically follows a sequential course. However, it is important to note that in some cases symptoms may be prolonged.

While this is all helpful... it does not explain how to identify a player with concussion during a game.

Rugby decided on this operational definition ( Raftery et al. 2016 ) :

... a concussion applies with any of the following: The presence, pitch side, of any Criteria Set 1 signs or symptoms (table 1)... [ Note : This table includes symptoms such as 'convulsion', 'clearly dazed', etc.]; An abnormal post game, same day assessment...; An abnormal 36--48 h assessment...; The presence of clinical suspicion by the treating doctor at any time...

Example 1.4 (Operational and conceptual definitions) Consider a study requiring water temperature to be measured.

An operational definition would explain how the temperature is measured: the thermometer type, how the thermometer was positioned, how long was it left in the water, and so on.

Example 1.5 (Operational definitions) Consider a study measuring stress in first-year university students.

Stress cannot be measured directly, but could be assessed using a survey (like the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) ( Cohen, Kamarck, and Mermelstein 1983 ) ).

The operational definition of stress is the score on the ten-question PSS. Other means of measuring stress are also possible (such as heart rate or blood pressure).

Meline ( 2006 ) discusses five studies about stuttering, each using a different operational definition:

- Study 1: As diagnosed by speech-language pathologist.

- Study 2: Within-word disfluences greater than 5 per 150 words.

- Study 3: Unnatural hesitation, interjections, restarted or incomplete phrases, etc.

- Study 4: More than 3 stuttered words per minute.

- Study 5: State guidelines for fluency disorders.

A study of snacking in Australia ( Fayet-Moore et al. 2017 ) used this operational definition of 'snacking':

...an eating occasion that occurred between meals based on time of day. --- Fayet-Moore et al. ( 2017 ) (p. 3)

A study examined the possible relationship between the 'pace of life' and the incidence of heart disease ( Levine 1990 ) in 36 US cities. The researchers used four different operational definitions for 'pace of life' (remember the article was published in 1990!):

- The walking speed of randomly chosen pedestrians.

- The speed with which bank clerks gave 'change for two $20 bills or [gave] two $20 bills for change'.

- The talking speed of postal clerks.

- The proportion of men and women wearing a wristwatch.

None of these perfectly measure 'pace of life', of course. Nonetheless, the researchers found that, compared to people on the West Coast,

... people in the Northeast walk faster, make change faster, talk faster and are more likely to wear a watch... --- Levine ( 1990 ) (p. 455)

- The Blogger

- Research Foundation

CONCEPTUAL AND OPERATIONAL DEFINITIONS: WHEN AND HOW TO USE THEM?

- by Dr J.D Ngo Ndjama

- November 30, 2020 November 30, 2020

To communicate their ideas to readers, researchers must be able to properly introduce their topic. Further definitions or explanation of terminologies also form part of the introduction and discussion. Definitions and explanations of keywords provide an overview of the subject while specifying important concepts, clarifying terms or concepts that researchers and readers are less familiar with; they also allow readers to have a synthesis of knowledge about a particular topic. However, particular attention must be given to the referencing of these definitions. Understanding a concept presupposes knowing its definition. To provide readers with an explanation of terminologies, researchers can use two modes of definition namely conceptual and operational definitions of terms.

Conceptual definition of constructs and variables

To properly explain and delimit your research topic and title, the use of conceptual definitions is encouraged. It aims to clearly express the idea conveyed by a construct. It is a way of stating the meaning of a variable in the context of its theoretical bases. Thus, it allows readers to have a clear, concise detailed definition of a construct. Conceptual definitions make it possible to define a concept by describing its characteristics and establishing relationships between its various defining elements. These definitions can be taken from all reference works such as journals, conference papers, newsletters, reports, magazines, seminars, newspapers, dissertations, theses and/or textbooks. These resources provide researchers and readers with a precise description of the terms. The need for operational definitions is fundamental when there is room for ambiguity, confusion, and uncertainty; and when a variable gives rise to multiple interpretations.

According to Leggett (2011), the process of specifying the exact meaning consist of describing the indicators researchers will be using to measure their concept and the different aspects of the concept, also called dimensions.

For example if you want to measure organisational commitment, you may choose to adopt its tri-dimensional model developed by Meyer and Allen (1997:106) namely affective commitment, continuance commitment and normative commitment. Or you may choose to measure organisational commitment using it four-dimensional model namely internalisation, compliance, affective and continuance commitment.

Operational definition of terms and variables

Operational definitions are definitions that you have formulated for your study. This is a way of stating the meaning of a variable depending on the purpose of the study. The researcher defines a variable based on how it will be used in his/her study and it is called ”the operationalisation” of the concept or variable. To operationalise a concept or variable in research means to specify precisely how a concept will be measured – the operations it will perform (Leggett, 2011). It is a process whereby researchers specify empirical concepts that can be taken as indicators of the attributes of a concept. To do so, researchers must understand the logic of the term, the idea convey by the variable and the perspective on which it is based. It also serve to identify metrics for quantifying a variable of interest.

An example of an operational definition is :

Many authors have defined organisation in different ways. However, in this study, it is viewed as a system made up of components that have unique properties, capabilities and mutual relationships.

The conceptual definition of organisation can be: a structure managed by a group of individuals working together towards a common goal.

As a researcher, you must be able to fully integrate the conceptual and operational definitions of terms or variables in your research projects to allow readers to fully grasp the essence of your work and show your examiners that you have a good comprehension of your title.

Leggett, A. (2011). Research problems and questions operationalization – constructs, concepts, variables and hypotheses. Marketing research, ch. 3.

8 thoughts on “CONCEPTUAL AND OPERATIONAL DEFINITIONS: WHEN AND HOW TO USE THEM?”

Fabulous content, I love it

Thanks Diane

I like using conceptual definitions but I also understand that it is important to operationalise my definitions to adapt them to the context. Great insight

Effectively Liezel, you should learn to incorporate both types of definition in your work as they will add more value to your work.

Greetings! Very useful advice in this particular post! Thanks for sharing!

I thank you Thabiso

Hi I would like to know if we can use both types of definitions in our dissertations

Dear Lesly, Of course it is highly recommended to include both types of definitions in your study. words can be defined in different ways and by different people, you must indicate which definition applies to your study and motivate your choice

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Unit 8: Theory…and Research…and Methods (oh my!)

31 Variables; Operational and Conceptual Definitions

Listen, this whole “conceptual and operational definition” stuff might seem painfully boring but it’s actually one of the most useful Superpowers in your SYBI toolbox. The disconnect between the actual concept, the conceptual definition, and the operational definition is more prevalent than you think! And the disconnect between the scholar’s ConceptConceptualDefinitionOperationalDefinition and the average journalist’s perception? Oi ve! It’s enough to make you want to laterally read EVERYTHING that comes your way. At least, I hope it does. Let’s start in nice and slow and think about what are variables anyway? Student textbook authors: Take it away!

Learning Objectives

What is a variable?

Variables; Operational and Conceptual Definitions

Many of you have probably heard of or know what a variable from other classes like algebra. Variables are important in research because they help define and measure what is being researched. In this unit you should be able to define a variable and know the two main components of variable.

Variables in social scientific research are similar to what you have learned in math classes, meaning they change depending on another element.

There are two components of a variable:

- A conceptual definition

- An operational definition

Conceptual Definitions- How we define something. It is the foundation of your research question because you must know what something is before you study its’ impact.

Example: How do Americans define the term freedom?

Operational Definitions- How we measure the variable. This is what you would typically think of when asked about the relationship between research and the research question. It relies on the conceptual definition.

Example: How do we measure what it means to have freedom?

Find the variables memory game .

Link to the “test” I mention in the video below:

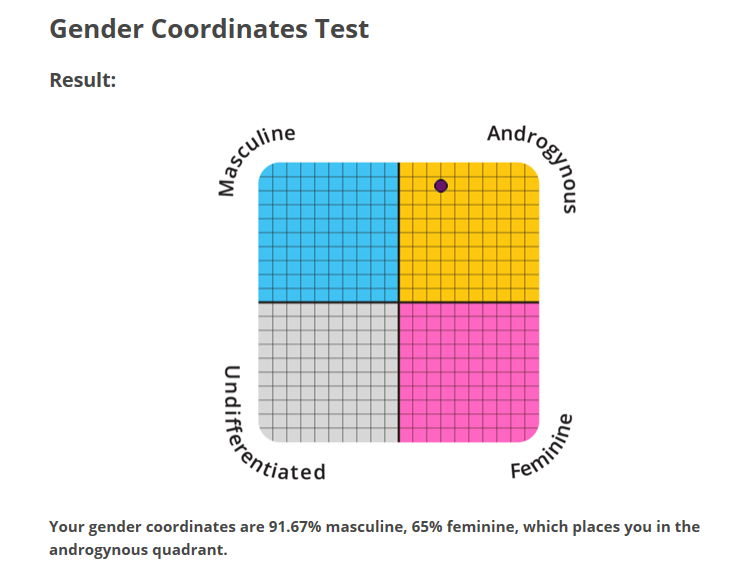

https://www.idrlabs.com/gender-coordinates/test.php

“Researchers H. Heilman, Ph.D. and C. Peus, Ph.D. used a multidimensional framework to assess how people view men and women respectively. Their research results found that men and women consistently ascribe the same characteristics to each gender.”

Give it a whirl , take the “test.” What do YOU think about how they have operationalized the concept of gender?

Humor me and read the information below the start of the questions when you visit that link [1] .

This second link takes you to a different test but of the same basic concept. This is the one I referenced as “Bem’s Sex Role Inventory [2] .” https://www.idrlabs.com/gender/test.php

Ok, so take this one too (it really doesn’t take long, I promise). What do you think about the questions? Did you “score” the same? If not, why do you think that is? What does that say about operationalizing the concept? In future chapters I’ll ask you to think about what this would say about results and implications! I know – you are so excited!!

Also. Was not exaggerating my results:

First image is coordinates (IN the blue box), second is Bem’s (under the blue box)

Got ideas for questions to include on the exam?

Click this link to add them!

… Unit 1 … Unit 2 …. Unit 3 … Unit 4 … Unit 5 … Unit 6 … Unit 7 … Unit 8 … Unit 9 … Unit 10 … Unit 11 … Unit 12 … Unit 13 … Unit 14 … Unit 15 … Unit 16 …

VIII . Unit 8: Theory…and Research…and Methods (oh my!)

28. Logical Systems: Induction and Deduction

29. Variables; Operational and Conceptual Definitions

30. Variable oh variable! Wherefore art thou o’ variable?

31. On being skeptical [about concepts and variables]

Gender Coordinates Test

Based on the work of heilman and peus, question 1 of 35.

Self-confident

- "Drawing on the work of Dr. Sandra Lipsitz Bem, this test classifies your personality as masculine or feminine. Though gender stereotyping is controversial, it is important to note that Bem's work has been tested in several countries and has repeatedly been shown to have high levels of validity and test-retest reliability. The test exclusively tests for immanent conceptions of gender (meaning that it doesn't theorize about whether gender roles are biological, cultural, or both). Consequently, the test has been used both by feminists as an instrument of cultural criticism and by gender traditionalists who seek to confirm that gender roles are natural and heritable." ↵

Introduction to Social Scientific Research Methods in the field of Communication 3rd Ed - under construction for Fall 2023 Copyright © 2023 by Kate Magsamen-Conrad. All Rights Reserved.

Share This Book

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

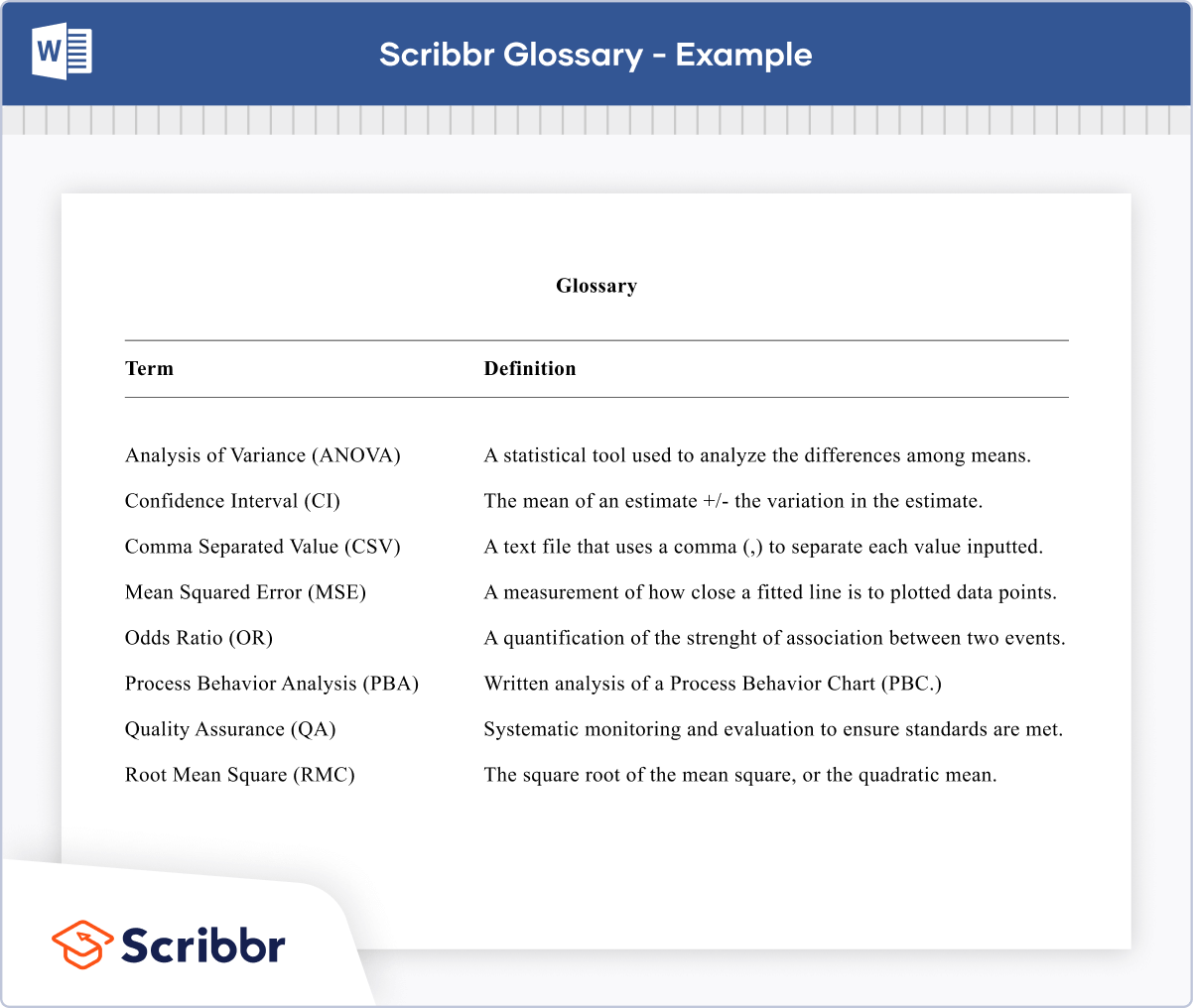

10.3 Operational definitions

Learning objectives.

Learners will be able to…

- Define and give an example of indicators and attributes for a variable

- Apply the three components of an operational definition to a variable

- Distinguish between levels of measurement for a variable and how those differences relate to measurement

- Describe the purpose of composite measures like scales and indices

Conceptual definitions are like dictionary definitions. They tell you what a concept means by defining it using other concepts. Operationalization occurs after conceptualization and is the process by which researchers spell out precisely how a concept will be measured in their study. It involves identifying the specific research procedures we will use to gather data about our concepts. It entails identifying indicators that can identify when your variable is present or not, the magnitude of the variable, and so forth.

Operationalization works by identifying specific indicators that will be taken to represent the ideas we are interested in studying. Let’s look at an example. Each day, Gallup researchers poll 1,000 randomly selected Americans to ask them about their well-being. To measure well-being, Gallup asks these people to respond to questions covering six broad areas: physical health, emotional health, work environment, life evaluation, healthy behaviors, and access to basic necessities. Gallup uses these six factors as indicators of the concept that they are really interested in, which is well-being .

Identifying indicators can be even simpler than this example. Political party affiliation is another relatively easy concept for which to identify indicators. If you asked a person what party they voted for in the last national election (or gained access to their voting records), you would get a good indication of their party affiliation. Of course, some voters split tickets between multiple parties when they vote and others swing from party to party each election, so our indicator is not perfect. Indeed, if our study were about political identity as a key concept, operationalizing it solely in terms of who they voted for in the previous election leaves out a lot of information about identity that is relevant to that concept. Nevertheless, it’s a pretty good indicator of political party affiliation.

Choosing indicators is not an arbitrary process. Your conceptual definitions point you in the direction of relevant indicators and then you can identify appropriate indicators in a scholarly manner using theory and empirical evidence. Specifically, empirical work will give you some examples of how the important concepts in an area have been measured in the past and what sorts of indicators have been used. Often, it makes sense to use the same indicators as previous researchers; however, you may find that some previous measures have potential weaknesses that your own study may improve upon.

So far in this section, all of the examples of indicators deal with questions you might ask a research participant on a questionnaire for survey research. If you plan to collect data from other sources, such as through direct observation or the analysis of available records, think practically about what the design of your study might look like and how you can collect data on various indicators feasibly. If your study asks about whether participants regularly change the oil in their car, you will likely not observe them directly doing so. Instead, you would rely on a survey question that asks them the frequency with which they change their oil or ask to see their car maintenance records.

TRACK 1 (IF YOU ARE CREATING A RESEARCH PROPOSAL FOR THIS CLASS):

What indicators are commonly used to measure the variables in your research question?

- How can you feasibly collect data on these indicators?

- Are you planning to collect your own data using a questionnaire or interview? Or are you planning to analyze available data like client files or raw data shared from another researcher’s project?

Remember, you need raw data . Your research project cannot rely solely on the results reported by other researchers or the arguments you read in the literature. A literature review is only the first part of a research project, and your review of the literature should inform the indicators you end up choosing when you measure the variables in your research question.

TRACK 2 (IF YOU AREN’T CREATING A RESEARCH PROPOSAL FOR THIS CLASS):

You are interested in studying older adults’ social-emotional well-being. Specifically, you would like to research the impact on levels of older adult loneliness of an intervention that pairs older adults living in assisted living communities with university student volunteers for a weekly conversation.

- How could you feasibly collect data on these indicators?

- Would you collect your own data using a questionnaire or interview? Or would you analyze available data like client files or raw data shared from another researcher’s project?

Steps in the Operationalization Process

Unlike conceptual definitions which contain other concepts, operational definition consists of the following components: (1) the variable being measured and its attributes, (2) the measure you will use, and (3) how you plan to interpret the data collected from that measure to draw conclusions about the variable you are measuring.

Step 1 of Operationalization: Specify variables and attributes

The first component, the variable, should be the easiest part. At this point in quantitative research, you should have a research question with identifiable variables. When social scientists measure concepts, they often use the language of variables and attributes . A variable refers to a quality or quantity that varies across people or situations. Attributes are the characteristics that make up a variable. For example, the variable hair color could contain attributes such as blonde, brown, black, red, gray, etc.

Levels of measurement

A variable’s attributes determine its level of measurement. There are four possible levels of measurement: nominal, ordinal, interval, and ratio. The first two levels of measurement are categorical , meaning their attributes are categories rather than numbers. The latter two levels of measurement are continuous , meaning their attributes are numbers within a range.

Nominal level of measurement

Hair color is an example of a nominal level of measurement. At the nominal level of measurement , attributes are categorical, and those categories cannot be mathematically ranked. In all nominal levels of measurement, there is no ranking order; the attributes are simply different. Gender and race are two additional variables measured at the nominal level. A variable that has only two possible attributes is called binary or dichotomous . If you are measuring whether an individual has received a specific service, this is a dichotomous variable, as the only two options are received or not received.

What attributes are contained in the variable hair color ? Brown, black, blonde, and red are common colors, but if we only list these attributes, many people may not fit into those categories. This means that our attributes were not exhaustive. Exhaustiveness means that every participant can find a choice for their attribute in the response options. It is up to the researcher to include the most comprehensive attribute choices relevant to their research questions. We may have to list a lot of colors before we can meet the criteria of exhaustiveness. Clearly, there is a point at which exhaustiveness has been reasonably met. If a person insists that their hair color is light burnt sienna , it is not your responsibility to list that as an option. Rather, that person would reasonably be described as brown-haired. Perhaps listing a category for other color would suffice to make our list of colors exhaustive.

What about a person who has multiple hair colors at the same time, such as red and black? They would fall into multiple attributes. This violates the rule of mutual exclusivity , in which a person cannot fall into two different attributes. Instead of listing all of the possible combinations of colors, perhaps you might include a multi-color attribute to describe people with more than one hair color.

Making sure researchers provide mutually exclusive and exhaustive attribute options is about making sure all people are represented in the data record. For many years, the attributes for gender were only male or female. Now, our understanding of gender has evolved to encompass more attributes that better reflect the diversity in the world. Children of parents from different races were often classified as one race or another, even if they identified with both. The option for bi-racial or multi-racial on a survey not only more accurately reflects the racial diversity in the real world but also validates and acknowledges people who identify in that manner. If we did not measure race in this way, we would leave empty the data record for people who identify as biracial or multiracial, impairing our search for truth.

Ordinal level of measurement

Unlike nominal-level measures, attributes at the ordinal level of measurement can be rank-ordered. For example, someone’s degree of satisfaction in their romantic relationship can be ordered by magnitude of satisfaction. That is, you could say you are not at all satisfied, a little satisfied, moderately satisfied, or highly satisfied. Even though these have a rank order to them (not at all satisfied is certainly worse than highly satisfied), we cannot calculate a mathematical distance between those attributes. We can simply say that one attribute of an ordinal-level variable is more or less than another attribute. A variable that is commonly measured at the ordinal level of measurement in social work is education (e.g., less than high school education, high school education or equivalent, some college, associate’s degree, college degree, graduate degree or higher). Just as with nominal level of measurement, ordinal-level attributes should also be exhaustive and mutually exclusive.

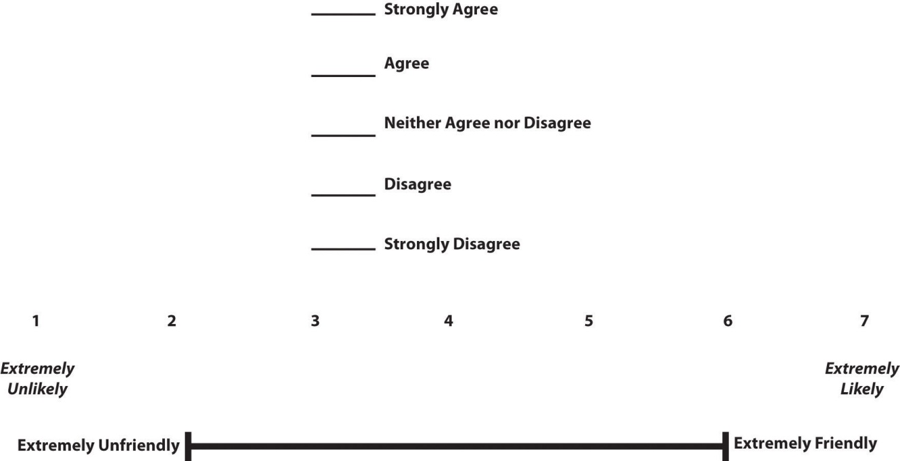

Rating scales for ordinal-level measurement

The fact that we cannot specify exactly how far apart the responses for different individuals in ordinal level of measurement can become clear when using rating scales . If you have ever taken a customer satisfaction survey or completed a course evaluation for school, you are familiar with rating scales such as, “On a scale of 1-5, with 1 being the lowest and 5 being the highest, how likely are you to recommend our company to other people?” Rating scales use numbers, but only as a shorthand, to indicate what attribute (highly likely, somewhat likely, etc.) the person feels describes them best. You wouldn’t say you are “2” likely to recommend the company, but you would say you are “not very likely” to recommend the company. In rating scales the difference between 2 = “ not very likely” and 3 = “ somewhat likely” is not quantifiable as a difference of 1. Likewise, we couldn’t say that it is the same as the difference between 3 = “ somewhat likely ” and 4 = “ very likely .”

Rating scales can be unipolar rating scales where only one dimension is tested, such as frequency (e.g., Never, Rarely, Sometimes, Often, Always) or strength of satisfaction (e.g., Not at all, Somewhat, Very). The attributes on a unipolar rating scale are different magnitudes of the same concept.

There are also bipolar rating scales where there is a dichotomous spectrum, such as liking or disliking (Like very much, Like somewhat, Like slightly, Neither like nor dislike, Dislike slightly, Dislike somewhat, Dislike very much). The attributes on the ends of a bipolar scale are opposites of one another. Figure 10.1 shows several examples of bipolar rating scales.

Interval level of measurement

Interval measures are continuous, meaning the meaning and interpretation of their attributes are numbers, rather than categories. Temperatures in Fahrenheit and Celsius are interval level, as are IQ scores and credit scores. Just like variables measured at the ordinal level, the attributes for variables measured at the interval level should be mutually exclusive and exhaustive, and are rank-ordered. In addition, they also have an equal distance between the attribute values.

The interval level of measurement allows us to examine “how much more” is one attribute when compared to another, which is not possible with nominal or ordinal measures. In other words, the unit of measurement allows us to compare the distance between attributes. The value of one unit of measurement (e.g., one degree Celsius, one IQ point) is always the same regardless of where in the range of values you look. The difference of 10 degrees between a temperature of 50 and 60 degrees Fahrenheit is the same as the difference between 60 and 70 degrees Fahrenheit.

We cannot, however, say with certainty what the ratio of one attribute is in comparison to another. For example, it would not make sense to say that a person with an IQ score of 140 has twice the IQ of a person with a score of 70. However, the difference between IQ scores of 80 and 100 is the same as the difference between IQ scores of 120 and 140.

You may find research in which ordinal-level variables are treated as if they are interval measures for analysis. This can be a problem because as we’ve noted, there is no way to know whether the difference between a 3 and a 4 on a rating scale is the same as the difference between a 2 and a 3. Those numbers are just placeholders for categories.

Ratio level of measurement

The final level of measurement is the ratio level of measurement . Variables measured at the ratio level of measurement are continuous variables, just like with interval scale. They, too, have equal intervals between each point. However, the ratio level of measurement has a true zero, which means that a value of zero on a ratio scale means that the variable you’re measuring is absent. For example, if you have no siblings, the a value of 0 indicates this (unlike a temperature of 0 which does not mean there is no temperature). What is the advantage of having a “true zero?” It allows you to calculate ratios. For example, if you have a three siblings, you can say that this is half the number of siblings as a person with six.

At the ratio level, the attribute values are mutually exclusive and exhaustive, can be rank-ordered, the distance between attributes is equal, and attributes have a true zero point. Thus, with these variables, we can say what the ratio of one attribute is in comparison to another. Examples of ratio-level variables include age and years of education. We know that a person who is 12 years old is twice as old as someone who is 6 years old. Height measured in meters and weight measured in kilograms are good examples. So are counts of discrete objects or events such as the number of siblings one has or the number of questions a student answers correctly on an exam. Measuring interval and ratio data is relatively easy, as people either select or input a number for their answer. If you ask a person how many eggs they purchased last week, they can simply tell you they purchased `a dozen eggs at the store, two at breakfast on Wednesday, or none at all.

The differences between each level of measurement are visualized in Table 10.2.

Levels of measurement=levels of specificity

We have spent time learning how to determine a variable’s level of measurement. Now what? How could we use this information to help us as we measure concepts and develop measurement tools? First, the types of statistical tests that we are able to use depend on level of measurement. With nominal-level measurement, for example, the only available measure of central tendency is the mode. With ordinal-level measurement, the median or mode can be used. Interval- and ratio-level measurement are typically considered the most desirable because they permit any indicators of central tendency to be computed (i.e., mean, median, or mode). Also, ratio-level measurement is the only level that allows meaningful statements about ratios of scores. The higher the level of measurement, the more options we have for the statistical tests we are able to conduct. This knowledge may help us decide what kind of data we need to gather, and how.

That said, we have to balance this knowledge with the understanding that sometimes, collecting data at a higher level of measurement could negatively impact our studies. For instance, sometimes providing answers in ranges may make prospective participants feel more comfortable responding to sensitive items. Imagine that you were interested in collecting information on topics such as income, number of sexual partners, number of times someone used illicit drugs, etc. You would have to think about the sensitivity of these items and determine if it would make more sense to collect some data at a lower level of measurement (e.g., nominal: asking if they are sexually active or not) versus a higher level such as ratio (e.g., their total number of sexual partners).

Finally, sometimes when analyzing data, researchers find a need to change a variable’s level of measurement. For example, a few years ago, a student was interested in studying the association between mental health and life satisfaction. This student used a variety of measures. One item asked about the number of mental health symptoms, reported as the actual number. When analyzing data, the student examined the mental health symptom variable and noticed that she had two groups, those with none or one symptoms and those with many symptoms. Instead of using the ratio level data (actual number of mental health symptoms), she collapsed her cases into two categories, few and many. She decided to use this variable in her analyses. It is important to note that you can move a higher level of data to a lower level of data; however, you are unable to move a lower level to a higher level.

- Check that the variables in your research question can vary…and that they are not constants or one of many potential attributes of a variable.

- Think about the attributes your variables have. Are they categorical or continuous? What level of measurement seems most appropriate?

Step 2 of Operationalization: Specify measures for each variable

Let’s pick a social work research question and walk through the process of operationalizing variables to see how specific we need to get. Suppose we hypothesize that residents of a psychiatric unit who are more depressed are less likely to be satisfied with care. Remember, this would be an inverse relationship—as levels of depression increase, satisfaction decreases. In this hypothesis, level of depression is the independent (or predictor) variable and satisfaction with care is the dependent (or outcome) variable.

How would you measure these key variables? What indicators would you look for? Some might say that levels of depression could be measured by observing a participant’s body language. They may also say that a depressed person will often express feelings of sadness or hopelessness. In addition, a satisfied person might be happy around service providers and often express gratitude. While these factors may indicate that the variables are present, they lack coherence. Unfortunately, what this “measure” is actually saying is that “I know depression and satisfaction when I see them.” In a research study, you need more precision for how you plan to measure your variables. Individual judgments are subjective, based on idiosyncratic experiences with depression and satisfaction. They couldn’t be replicated by another researcher. They also can’t be done consistently for a large group of people. Operationalization requires that you come up with a specific and rigorous measure for seeing who is depressed or satisfied.

Finding a good measure for your variable depends on the kind of variable it is. Variables that are directly observable might include things like taking someone’s blood pressure, marking attendance or participation in a group, and so forth. To measure an indirectly observable variable like age, you would probably put a question on a survey that asked, “How old are you?” Measuring a variable like income might first require some more conceptualization, though. Are you interested in this person’s individual income or the income of their family unit? This might matter if your participant does not work or is dependent on other family members for income. Do you count income from social welfare programs? Are you interested in their income per month or per year? Even though indirect observables are relatively easy to measure, the measures you use must be clear in what they are asking, and operationalization is all about figuring out the specifics about how to measure what you want to know. For more complicated variables such as constructs, you will need compound measures that use multiple indicators to measure a single variable.

How you plan to collect your data also influences how you will measure your variables. For social work researchers using secondary data like client records as a data source, you are limited by what information is in the data sources you can access. If a partnering organization uses a given measurement for a mental health outcome, that is the one you will use in your study. Similarly, if you plan to study how long a client was housed after an intervention using client visit records, you are limited by how their caseworker recorded their housing status in the chart. One of the benefits of collecting your own data is being able to select the measures you feel best exemplify your understanding of the topic.

Composite measures

Depending on your research design, your measure may be something you put on a survey or pre/post-test that you give to your participants. For a variable like age or income, one well-worded item may suffice. Unfortunately, most variables in the social world are not so simple. Depression and satisfaction are multidimensional concepts. Relying on a indicator that is a single item on a questionnaire like a question that asks “Yes or no, are you depressed?” does not encompass the complexity of constructs.

For more complex variables, researchers use scales and indices (sometimes called indexes) because they use multiple items to develop a composite (or total) score as a measure for a variable. As such, they are called composite measures . Composite measures provide a much greater understanding of concepts than a single item could.

It can be complex to delineate between multidimensional and unidimensional concepts. If satisfaction were a key variable in our study, we would need a theoretical framework and conceptual definition for it. Perhaps we come to view satisfaction has having two dimensions: a mental one and an emotional one. That means we would need to include indicators that measured both mental and emotional satisfaction as separate dimensions of satisfaction. However, if satisfaction is not a key variable in your theoretical framework, it may make sense to operationalize it as a unidimensional concept.

Although we won’t delve too deeply into the process of scale development, we will cover some important topics for you to understand how scales and indices developed by other researchers can be used in your project.

Need to make better sense of the following content:

Measuring abstract concepts in concrete terms remains one of the most difficult tasks in empirical social science research.

A scale , XXXXXXXXXXXX .

The scales we discuss in this section are a different from “rating scales” discussed in the previous section. A rating scale is used to capture the respondents’ reactions to a given item on a questionnaire. For example, an ordinally scaled item captures a value between “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree.” Attaching a rating scale to a statement or instrument is not scaling. Rather, scaling is the formal process of developing scale items, before rating scales can be attached to those items.

If creating your own scale sounds painful, don’t worry! For most constructs, you would likely be duplicating work that has already been done by other researchers. Specifically, this is a branch of science called psychometrics. You do not need to create a scale for depression because scales such as the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) [1] , the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) [2] , and Beck’s Depression Inventory [3] (BDI) have been developed and refined over dozens of years to measure variables like depression. Similarly, scales such as the Patient Satisfaction Questionnaire (PSQ-18) have been developed to measure satisfaction with medical care. As we will discuss in the next section, these scales have been shown to be reliable and valid. While you could create a new scale to measure depression or satisfaction, a study with rigor would pilot test and refine that new scale over time to make sure it measures the concept accurately and consistently before using it in other research. This high level of rigor is often unachievable in smaller research projects because of the cost and time involved in pilot testing and validating, so using existing scales is recommended.

Unfortunately, there is no good one-stop-shop for psychometric scales. The Mental Measurements Yearbook provides a list of measures for social science variables, though it is incomplete and may not contain the full documentation for instruments in its database. It is available as a searchable database by many university libraries.

Perhaps an even better option could be looking at the methods section of the articles in your literature review. The methods section of each article will detail how the researchers measured their variables, and often the results section is instructive for understanding more about measures. In a quantitative study, researchers may have used a scale to measure key variables and will provide a brief description of that scale, its names, and maybe a few example questions. If you need more information, look at the results section and tables discussing the scale to get a better idea of how the measure works.

Looking beyond the articles in your literature review, searching Google Scholar or other databases using queries like “depression scale” or “satisfaction scale” should also provide some relevant results. For example, searching for documentation for the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale, I found this report about useful measures for acceptance and commitment therapy which details measurements for mental health outcomes. If you find the name of the scale somewhere but cannot find the documentation (i.e., all items, response choices, and how to interpret the scale), a general web search with the name of the scale and “.pdf” may bring you to what you need. Or, to get professional help with finding information, ask a librarian!

Unfortunately, these approaches do not guarantee that you will be able to view the scale itself or get information on how it is interpreted. Many scales cost money to use and may require training to properly administer. You may also find scales that are related to your variable but would need to be slightly modified to match your study’s needs. You could adapt a scale to fit your study, however changing even small parts of a scale can influence its accuracy and consistency. Pilot testing is always recommended for adapted scales, and researchers seeking to draw valid conclusions and publish their results should take this additional step.

Types of scales

Likert scales.

Although Likert scale is a term colloquially used to refer to almost any rating scale (e.g., a 0-to-10 life satisfaction scale), it has a much more precise meaning. In the 1930s, researcher Rensis Likert (pronounced LICK-ert) created a new approach for measuring people’s attitudes (Likert, 1932) . [4] It involves presenting people with several statements—including both favorable and unfavorable statements—about some person, group, or idea. Respondents then express their approval or disapproval with each statement on a 5-point rating scale: Strongly Approve , Approve , Undecided , Disapprove, Strongly Disapprove . Numbers are assigned to each response a nd then summed across all items to produce a score representing the attitude toward the person, group, or idea. For items that are phrased in an opposite direction (e.g., negatively worded statements instead of positively worded statements), reverse coding is used so that the numerical scoring of statements also runs in the opposite direction. The scores for the entire set of items are totaled for a score for the attitude of interest. This type of scale came to be called a Likert scale, as indicated in Table 10.3 below. Scales that use similar logic but do not have these exact characteristics are referred to as “Likert-type scales.”

Semantic Differential Scales

Semantic differential scales are composite scales in which respondents are asked to indicate their opinions or feelings toward a single statement using different pairs of adjectives framed as polar opposites. Whereas in a Likert scale, a participant is asked how much they approve or disapprove of a statement, in a semantic differential scale the participant is asked to indicate how they about a specific item using several pairs of opposites. This makes the semantic differential scale an excellent technique for measuring people’s feelings toward objects, events, or behaviors. Table 10.4 provides an example of a semantic differential scale that was created to assess participants’ feelings about this textbook.

Guttman Scales

A specialized scale for measuring unidimensional concepts was designed by Louis Guttman. A Guttman scale (also called cumulative scale ) uses a series of items arranged in increasing order of intensity (least intense to most intense) of the concept. This type of scale allows us to understand the intensity of beliefs or feelings. Each item in the Guttman scale below has a weight (this is not indicated on the tool) which varies with the intensity of that item, and the weighted combination of each response is used as an aggregate measure of an observation.

Table XX presents an example of a Guttman Scale. Notice how the items move from lower intensity to higher intensity. A researcher reviews the yes answers and creates a score for each participant.

Example Guttman Scale Items

- I often felt the material was not engaging Yes/No

- I was often thinking about other things in class Yes/No

- I was often working on other tasks during class Yes/No

- I will work to abolish research from the curriculum Yes/No

An index is a composite score derived from aggregating measures of multiple indicators. At its most basic, an index sums up indicators. A well-known example of an index is the consumer price index (CPI), which is computed every month by the Bureau of Labor Statistics of the U.S. Department of Labor. The CPI is a measure of how much consumers have to pay for goods and services (in general) and is divided into eight major categories (food and beverages, housing, apparel, transportation, healthcare, recreation, education and communication, and “other goods and services”), which are further subdivided into more than 200 smaller items. Each month, government employees call all over the country to get the current prices of more than 80,000 items. Using a complicated weighting scheme that takes into account the location and probability of purchase for each item, analysts then combine these prices into an overall index score using a series of formulas and rules.

Another example of an index is the Duncan Socioeconomic Index (SEI). This index is used to quantify a person’s socioeconomic status (SES) and is a combination of three concepts: income, education, and occupation. Income is measured in dollars, education in years or degrees achieved, and occupation is classified into categories or levels by status. These very different measures are combined to create an overall SES index score. However, SES index measurement has generated a lot of controversy and disagreement among researchers.

The process of creating an index is similar to that of a scale. First, conceptualize the index and its constituent components. Though this appears simple, there may be a lot of disagreement on what components (concepts/constructs) should be included or excluded from an index. For instance, in the SES index, isn’t income correlated with education and occupation? And if so, should we include one component only or all three components? Reviewing the literature, using theories, and/or interviewing experts or key stakeholders may help resolve this issue. Second, operationalize and measure each component. For instance, how will you categorize occupations, particularly since some occupations may have changed with time (e.g., there were no Web developers before the Internet)? As we will see in step three below, researchers must create a rule or formula for calculating the index score. Again, this process may involve a lot of subjectivity, so validating the index score using existing or new data is important.

Differences between scales and indices

Though indices and scales yield a single numerical score or value representing a concept of interest, they are different in many ways. First, indices often comprise components that are very different from each other (e.g., income, education, and occupation in the SES index) and are measured in different ways. Conversely, scales typically involve a set of similar items that use the same rating scale (such as a five-point Likert scale about customer satisfaction).

Second, indices often combine objectively measurable values such as prices or income, while scales are designed to assess subjective or judgmental constructs such as attitude, prejudice, or self-esteem. Some argue that the sophistication of the scaling methodology makes scales different from indexes, while others suggest that indexing methodology can be equally sophisticated. Nevertheless, indexes and scales are both essential tools in social science research.

Scales and indices seem like clean, convenient ways to measure different phenomena in social science, but just like with a lot of research, we have to be mindful of the assumptions and biases underneath. What if the developers of scale or an index were influenced by unconscious biases? Or what if it was validated using only White women as research participants? Is it going to be useful for other groups? It very well might be, but when using a scale or index on a group for whom it hasn’t been tested, it will be very important to evaluate the validity and reliability of the instrument, which we address in the rest of the chapter.

Finally, it’s important to note that while scales and indices are often made up of items measured at the nominal or ordinal level, the scores on the composite measurement are continuous variables.

Looking back to your work from the previous section, are your variables unidimensional or multidimensional?

- Describe the specific measures you will use (actual questions and response options you will use with participants) for each variable in your research question.

- If you are using a measure developed by another researcher but do not have all of the questions, response options, and instructions needed to implement it, put it on your to-do list to get them.

- Describe at least one specific measure you would use (actual questions and response options you would use with participants) for the dependent variable in your research question.

Step 3 in Operationalization: Determine how to interpret measures

The final stage of operationalization involves setting the rules for how the measure works and how the researcher should interpret the results. Sometimes, interpreting a measure can be incredibly easy. If you ask someone their age, you’ll probably interpret the results by noting the raw number (e.g., 22) someone provides and that it is lower or higher than other people’s ages. However, you could also recode that person into age categories (e.g., under 25, 20-29-years-old, generation Z, etc.). Even scales or indices may be simple to interpret. If there is an index of problem behaviors, one might simply add up the number of behaviors checked off–with a range from 1-5 indicating low risk of delinquent behavior, 6-10 indicating the student is moderate risk, etc. How you choose to interpret your measures should be guided by how they were designed, how you conceptualize your variables, the data sources you used, and your plan for analyzing your data statistically. Whatever measure you use, you need a set of rules for how to take any valid answer a respondent provides to your measure and interpret it in terms of the variable being measured.

For more complicated measures like scales, refer to the information provided by the author for how to interpret the scale. If you can’t find enough information from the scale’s creator, look at how the results of that scale are reported in the results section of research articles. For example, Beck’s Depression Inventory (BDI-II) uses 21 statements to measure depression and respondents rate their level of agreement on a scale of 0-3. The results for each question are added up, and the respondent is put into one of three categories: low levels of depression (1-16), moderate levels of depression (17-30), or severe levels of depression (31 and over) ( NEEDS CITATION) .

Operationalization is a tricky component of basic research methods, so don’t get frustrated if it takes a few drafts and a lot of feedback to get to a workable operational definition.

Key Takeaways

- Operationalization involves spelling out precisely how a concept will be measured.

- Operational definitions must include the variable, the measure, and how you plan to interpret the measure.

- There are four different levels of measurement: nominal, ordinal, interval, and ratio (in increasing order of specificity).

- Scales and indices are common ways to collect information and involve using multiple indicators in measurement.

- A key difference between a scale and an index is that a scale contains multiple indicators for one concept, whereas an indicator examines multiple concepts (components).

- Using scales developed and refined by other researchers can improve the rigor of a quantitative study.

Use the research question that you developed in the previous chapters and find a related scale or index that researchers have used. If you have trouble finding the exact phenomenon you want to study, get as close as you can.

- What is the level of measurement for each item on each tool? Take a second and think about why the tool’s creator decided to include these levels of measurement. Identify any levels of measurement you would change and why.

- If these tools don’t exist for what you are interested in studying, why do you think that is?

Using your working research question, find a related scale or index that researchers have used to measure the dependent variable. If you have trouble finding the exact phenomenon you want to study, get as close as you can.

- What is the level of measurement for each item on the tool? Take a second and think about why the tool’s creator decided to include these levels of measurement. Identify any levels of measurement you would change and why.

- Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R. L., & Williams, J. B. (2001). The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. Journal of general internal medicine, 16(9), 606–613. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x ↵

- Radloff, L. S. (1977). The CES-D scale: A self report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurements, 1, 385-401. ↵

- Beck, A. T., Ward, C. H., Mendelson, M., Mock, J., & Erbaugh, J. (1961). An inventory for measuring depression. Archives of general psychiatry, 4, 561–571. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.1961.01710120031004 ↵

- Likert, R. (1932). A technique for the measurement of attitudes. Archives of Psychology, 140 , 1–55. ↵

process by which researchers spell out precisely how a concept will be measured in their study

Clues that demonstrate the presence, intensity, or other aspects of a concept in the real world

unprocessed data that researchers can analyze using quantitative and qualitative methods (e.g., responses to a survey or interview transcripts)

“a logical grouping of attributes that can be observed and measured and is expected to vary from person to person in a population” (Gillespie & Wagner, 2018, p. 9)

The characteristics that make up a variable

variables whose values are organized into mutually exclusive groups but whose numerical values cannot be used in mathematical operations.

variables whose values are mutually exclusive and can be used in mathematical operations

The lowest level of measurement; categories cannot be mathematically ranked, though they are exhaustive and mutually exclusive

Exhaustive categories are options for closed ended questions that allow for every possible response (no one should feel like they can't find the answer for them).

Mutually exclusive categories are options for closed ended questions that do not overlap, so people only fit into one category or another, not both.

Level of measurement that follows nominal level. Has mutually exclusive categories and a hierarchy (rank order), but we cannot calculate a mathematical distance between attributes.

An ordered set of responses that participants must choose from.

A rating scale where the magnitude of a single trait is being tested

A rating scale in which a respondent selects their alignment of choices between two opposite poles such as disagreement and agreement (e.g., strongly disagree, disagree, agree, strongly agree).

A level of measurement that is continuous, can be rank ordered, is exhaustive and mutually exclusive, and for which the distance between attributes is known to be equal. But for which there is no zero point.

The highest level of measurement. Denoted by mutually exclusive categories, a hierarchy (order), values can be added, subtracted, multiplied, and divided, and the presence of an absolute zero.

measurements of variables based on more than one one indicator

An empirical structure for measuring items or indicators of the multiple dimensions of a concept.

measuring people’s attitude toward something by assessing their level of agreement with several statements about it

Composite (multi-item) scales in which respondents are asked to indicate their opinions or feelings toward a single statement using different pairs of adjectives framed as polar opposites.

A composite scale using a series of items arranged in increasing order of intensity of the construct of interest, from least intense to most intense.

a composite score derived from aggregating measures of multiple concepts (called components) using a set of rules and formulas

Doctoral Research Methods in Social Work Copyright © by Mavs Open Press. All Rights Reserved.

Share This Book

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Dissertation

- Operationalisation | A Guide with Examples, Pros & Cons

Operationalisation | A Guide with Examples, Pros & Cons

Published on 6 May 2022 by Pritha Bhandari . Revised on 10 October 2022.

Operationalisation means turning abstract concepts into measurable observations. Although some concepts, like height or age, are easily measured, others, like spirituality or anxiety, are not.

Through operationalisation, you can systematically collect data on processes and phenomena that aren’t directly observable.

- Self-rating scores on a social anxiety scale

- Number of recent behavioural incidents of avoidance of crowded places

- Intensity of physical anxiety symptoms in social situations

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Be assured that you'll submit flawless writing. Upload your document to correct all your mistakes.

Table of contents

Why operationalisation matters, how to operationalise concepts, strengths of operationalisation, limitations of operationalisation, frequently asked questions about operationalisation.

In quantitative research , it’s important to precisely define the variables that you want to study.

Without transparent and specific operational definitions, researchers may measure irrelevant concepts or inconsistently apply methods. Operationalisation reduces subjectivity and increases the reliability of your study.

Your choice of operational definition can sometimes affect your results. For example, an experimental intervention for social anxiety may reduce self-rating anxiety scores but not behavioural avoidance of crowded places. This means that your results are context-specific and may not generalise to different real-life settings.

Generally, abstract concepts can be operationalised in many different ways. These differences mean that you may actually measure slightly different aspects of a concept, so it’s important to be specific about what you are measuring.

If you test a hypothesis using multiple operationalisations of a concept, you can check whether your results depend on the type of measure that you use. If your results don’t vary when you use different measures, then they are said to be ‘robust’.

The only proofreading tool specialized in correcting academic writing

The academic proofreading tool has been trained on 1000s of academic texts and by native English editors. Making it the most accurate and reliable proofreading tool for students.

Correct my document today

There are three main steps for operationalisation:

- Identify the main concepts you are interested in studying.

- Choose a variable to represent each of the concepts.

- Select indicators for each of your variables.

Step 1: Identify the main concepts you are interested in studying

Based on your research interests and goals, define your topic and come up with an initial research question .

There are two main concepts in your research question:

- Social media behaviour

Step 2: Choose a variable to represent each of the concepts

Your main concepts may each have many variables , or properties, that you can measure.

For instance, are you going to measure the amount of sleep or the quality of sleep? And are you going to measure how often teenagers use social media, which social media they use, or when they use it?

- Alternate hypothesis: Lower quality of sleep is related to higher night-time social media use in teenagers.

- Null hypothesis: There is no relation between quality of sleep and night-time social media use in teenagers.

Step 3: Select indicators for each of your variables

To measure your variables, decide on indicators that can represent them numerically.

Sometimes these indicators will be obvious: for example, the amount of sleep is represented by the number of hours per night. But a variable like sleep quality is harder to measure.

You can come up with practical ideas for how to measure variables based on previously published studies. These may include established scales or questionnaires that you can distribute to your participants. If none are available that are appropriate for your sample, you can develop your own scales or questionnaires.

- To measure sleep quality, you give participants wristbands that track sleep phases.