Prebisch-Singer Thesis: Assumptions and Criticisms | Trade | Economics

In this article we will discuss about:- 1. Introduction to Prebisch-Singer Thesis 2. Assumptions in the Prebisch-Singer thesis 3. Criticisms.

Introduction to Prebisch-Singer Thesis:

There is empirical evidence related to the fact that the terms of trade have been continuously moving against the developing countries. On the basis of exports statistics concerning the United Kingdom between 1870 and 1940, Raul Prebisch demonstrated that the terms of trade had secular tendency to move against the primary products and in favour of the manufactured and capital goods.

This viewpoint has been strongly supported by H. W. Singer. The essence of Prebisch-Singer thesis is that the peripheral or LDC’s had to export large amounts of their primary products in order to import manufactured goods from the industrially advanced countries. The deterioration of terms of trade has been a major inhibitory factor in the growth of the LDC’s.

Prebisch and Singer maintain that there has been technical progress in the advanced countries, the fruit of which have not percolated to the LDC’s. In addition, the industrialised countries have maintained a monopoly control over the production of industrial goods. They could manipulate the prices of manufactured goods in their favour and against the interest of the LDC’s.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Except the success of OPEC in raising the prices of crude oil since mid 1970’s, there has been a relative decline in the international prices of farm and plantation products, minerals and forest products. Consequently, the terms of trade have remained unfavourable to the developing countries.

Assumptions in the Prebisch-Singer thesis:

The main assumptions in the Prebisch-Singer thesis are as under:

(i) As income rises in the advanced countries, the pattern of demand shifts from primary products to the manufactured products due to Engel’s law.

(ii) There is slow rise in demand for products in the developed countries.

(iii) The export market for product of LDC’s is competitive.

(iv) The export market for products of developed countries is monopolistic.

(v) Wages and prices are low in LDC’s.

(vi) The appearance of substitutes for products of LDC’s reduces demand for them.

(vii) The benefit of increased productivity is not passed by the producers of manufactured products in advanced countries to the LDC’s through lower prices.

(viii) The economic growth in the LDC’s is indicated by income terms of trade.

Singer has pointed out that the recent increase in debt problem of the LDC’s has imparted another twist to the hypothesis of secular deterioration of terms of trade for them in two ways. Firstly, a high proportion of proceeds from exports are not available for imports.

Secondly, there is an increased pressure upon the LDC’s to raise exports in order to repay external debts on account of IMF-induced adjustment polices. These pressures make the debt- ridden LDC’s to compete with other poor countries to enlarge their export earnings. It results in decline in the prices of export products of these countries.

Criticisms of Prebisch-Singer Thesis :

The Prebisch-Singer Thesis has come to be criticized on several grounds:

(i) Not Firm Basis for Inference:

The inference of secular deterioration of terms of trade for the LDC’s rests upon the exports of primary vis-a-vis manufactured products. In this regards, it should be remembered that the LDC’s export wide variety of primary products. Sometimes they export also certain manufactured products.

They, at the same time, do not import only manufactured products but also a number of primary products. It is, therefore, not proper to draw a firm inference about terms of trade just on the basis of primary versus manufactured exports.

(ii) Faulty Statement of Gains and Losses of Primary Exporters:

Jagdish Bhagwati has pointed out that the index of terms of trade employed in this thesis understates the gains of exporters of primary products. At the same time, there is overstatement of losses of primary producers.

(iii) Faulty Index of TOT:

The Prebisch- Singer hypothesis rests upon the index, which is the inverse of the British commodity terms of trade. This index overlooks the qualitative changes in products, appearance of new varieties of products, services like transport etc. The generalisation based on British terms of trade for the period 1870 to 1930, according to Kindleberger, is not true for the other developed countries of Europe.

(iv) Neglect of Supply Conditions:

In the determination of terms of trade, the Prebisch-Singer thesis considers only demand conditions. The supply conditions, which are likely to change significantly over time, have been neglected. The relative prices, in fact, depend not only upon the demand conditions but also on the supply conditions.

(v) Little Effect of Monopoly Power:

One of the arguments in support of this thesis was that the higher degree of monopoly power existing in industry than in agriculture led to secular deterioration of terms of trade for the developing countries. In this connection, it was also agreed that the monopoly element prohibited the percolation of benefits of technical progress to the LDC’s. The empirical evidence has not supported such a line of argument.

(vi) Inapplicability of Engel’s Law:

The secular decline in the demand for primary products in developed countries was attributed to Engel’s Law. But this is not true because this law is applicable to food and not to the raw materials, which constitute sizeable proportion of exports from, the LDC’s.

(vii) Benefits from Foreign Investment:

The deterioration of the terms of trade for the LDC’s is sometimes linked not to non-transmission of productivity gains to them by advanced countries through lower prices of manufactured goods, yet the benefits from foreign investments have percolated to the LDC’s through the product innovations, product improvement and product diversification. These benefits can amply offset any adverse effects of foreign investment upon terms of trade and the process of growth.

(viii) Difficult to Assess Variation in Demand for Primary Products:

The secular deterioration in terms of trade of the LDC’s during 1870 to 1930 period was supposed to be on account of the declining world demand for primary products. During that period, there were tremendous changes in world population, production techniques, living standards and means of transport. Given those extensive developments, it is extremely difficult to assess precisely the changes in world demand for primary products and the impact of those changes upon the terms of trade.

(ix) Export Instability and Price Variations:

The Prebisch-Singer thesis suggested that export instability in the LDC’s was basically due to variations in prices of primary products relative to those of manufactured products. Mc Been, on the contrary, held that the export instability in those countries could be on account of quantity variations rather than the price variations.

(x) Development of Export Sector not at the Expense of Domestic Sector:

In this thesis, Singer contended that foreign investments in poor countries, no doubt, enlarged the export sector but it was at the expense of the growth of domestic sector. This contention is, however, not always true because the foreign investments have not always crowded out the domestic investment. If foreign investments have helped exclusively the growth of export sector, even that should be treated as acceptable because some growth is better than no growth. It is farfetched to relate worsening of terms of trade to the non-growth of domestic sector.

(xi) Faulty Policy Prescription:

Prebisch prescribed the adoption of protectionist policies by LDC’s to offset the worsening terms of trade. Any gains from tariff or non-tariff restrictions upon imports from advanced countries can at best be only short-lived because they will provoke retaliatory actions from them causing still greater injury to the LDC’s.

In the present W.TO regime of dismantling of trade restrictions, Prebisch suggestion is practically not possible to implement. There should be rather greater recourse to export promotion, import substitution, favourable trade agreements and adoption of appropriate monetary and fiscal action for improving the terms of trade in the developing countries.

(xii) Lack of Empirical Support:

The studies made by Morgan, Ellsworth, Haberler, Kindelberger and Lipsey have not supported the secular deterioration of terms of trade hypothesis, Lipsey has observed, “Although there have been very large swings in U.S. terms of trade since 1879, no long term trend has emerged. The average level of U.S. terms of trade since World War II has been almost the same as before World War I.” This objection of lack of empirical support against the Prebisch-Singer hypothesis is actually not very sound. A number of more recent empirical studies have, in fact, gone in favour of this hypothesis.

Despite all the objections raised against the Prebisch-Singer thesis, the empirical evidence has accumulated in support of it. The studies made by UNCTAD for 1950-61 and 1960-73 periods showed that there was a relative decline in the terms of trade of LDC’s vis-a-vis the developed countries. A study attempted by Thirlwall and Bergevin for the period 1973-82 indicated that there was an annual decline of terms of trade of LDC’s for all the primary commodity exports at the rate of 0.36 percent.

On the basis of their study related to exports of manufactured products for LDC’s to the advanced countries during 1970-87 period, Singer and Sarkar found that the terms of trade of LDC’s declined by about 1 percent per annum. Even the World Development Report 1955 recognised that the world prices of primary products declined sharply during I980’s and the terms of trade of LDC’s deteriorated during 1980-93 period.

According to the 1997 Human Development Report of UNDP, the terms of trade for the least developed countries declined by a cumulative 50 percent over the past 25 years. According to South Commission, compared with 1980, the terms of trade of developing countries had deteriorated by 29 percent in 1988. The average real price of non-oil commodities had declined by 25 percent during 1980-88 period compared with the previous two decades. The terms of trade of non-oil developing countries had deteriorated during 1980-88 period by 8 percent compared with 1960’s and 13 percent compared with 1970’s.

Related Articles:

- Reasons for Secular Deterioration of Terms of Trade | Economics

- Single Factorial Terms of Trade (With Criticisms) | Economics

- Export Pessimism: Nurkse’s Version and Testing | International Economics

- Income Terms of Trade (With Criticisms) | Economics

Declining Terms of Trade

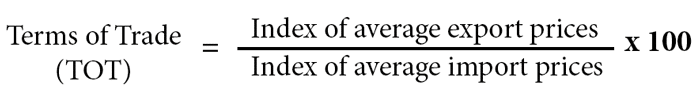

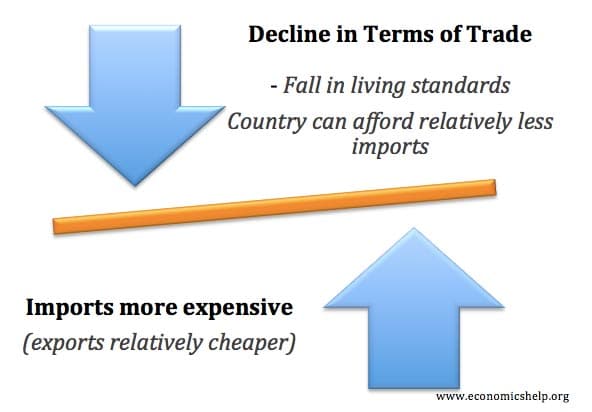

- The Terms of trade refer to the relative price of exports/imports.

- A decline in the terms of trade means the price of exports falls relative to imports. Imports become more expensive.

- Typically a country will have lower living standards and less ability to import.

Impact of decline in terms of trade on a developing economy

Suppose a developing country exports coffee beans and imports manufactured goods.

- A decline in the terms of trade will mean a country will see the price of coffee beans fall relative to the price of imported manufactured goods. This means it has to export relatively more coffee beans to get the same quantity of manufactured goods.

- A prolonged fall in the terms of trade could be seen as a problem because it can lead to declining living standards and lower GDP.

- It could also reduce export revenue and make it harder to pay foreign external debt. This would be a problem for developing economies with high external debt. TO meet the debt repayments may require a relatively higher percentage of national income on meeting repayments in foreign currency.

Cost of decline in terms of trade

World Bank estimates suggest that between 1970 and 1997 declining terms of trade cost non-oil-exporting countries in Africa the equivalent of 119 percent of their combined annual gross domestic product (GDP) in lost revenues. It will also be more difficult to earn more foreign currency to pay external debt. [1. State of Agricultural Markets FAO]

Many developing countries concentrate on producing primary products, but according to The Prebisch-Singer hypothesis, there is likely to be a fall in the terms of trade when you concentrate on primary products. This is because:

- Low income elasticity of demand. As incomes rise, demand doesn’t rise so much.

- Increased productivity (fertilizers e.t.c.) increases supply and reduces price.

Between 1961 and 2001, the average prices of agricultural commodities sold by LDCs fell by almost 70 percent relative to the price of manufactured goods purchased from developed countries [2. The State of Agricultural Markets 2004 FAO ]

- A decline in the terms of trade is not necessarily a bad thing. For example, a decline in the terms of trade may occur due to a devaluation in the exchange rate. This devaluation may enable a country to regain competitiveness and increase the quantity of exports. For example, the UK in 1992 benefited from a decline in the terms of trade.

- The impact of a decline in the terms of trade will depend on the elasticity of demand. If demand is elastic, the lower price of exports will cause a bigger % increase in demand.

- Some LDC’s have seen an improvement in terms of trade because of rising price of commodities and food post-2008. It is not always LDCs who see a decline in the terms of trade.

- It is important to distinguish between a short-term decline in terms of trade and a long-term decline. A long-term decline is more serious for reflecting a fall in living standards.

- Terms of trade and balance of trade

- Terms of trade effect in the UK

3 thoughts on “Declining Terms of Trade”

Discuss the secular declining hypothesis of terms of trade and its implication to project management. And, explain also how it is also connected with an informal network circumventing the overriding objective of government, market and NGOs.

Could you send me this question correct answer.

Comments are closed.

- Earth and Environment

- Literature and the Arts

- Philosophy and Religion

- Plants and Animals

- Science and Technology

- Social Sciences and the Law

- Sports and Everyday Life

- Additional References

- Social sciences

- Applied and social sciences magazines

Prebisch-Singer Hypothesis

The prebisch-singer hypothesis and its policy implications, the evolution of the prebisch-singer hypothesis, the prebisch-singer hypothesis: different explanations, bibliography.

The classical economists believed that the terms-of-trade of primary products would show long-term improvement vis- à -vis manufactures due to the operation of the law of diminishing returns in primary production and the law of increasing returns in manufactures. The policy implication of this classical proposition is that a primary-producing country need not industrialize to enjoy the gains from technical progress taking place in manufactures; free play of international market forces will distribute the gains from the industrial countries to the primary-producing countries through the higher prices of their exports of primary products relative to the prices of their imports of manufactures (that is, the terms-of-trade will move in favor of primary-product exporting countries).

The opposite hypothesis — the Prebisch-Singer hypothesis of long-term deterioration in the terms-of-trade of primary products — can be traced back to the early mid-twentieth-century writings of Charles Kindleberger. He thought it inexorable for the terms-of-trade to turn against primary producing countries because of the operation of Engel ’ s law — which states the demand for goods needed for bare subsistence such as food rises less than proportionately while demand for other luxury consumption goods rises more than proportionately — in the process of world economic growth and improvements in the standard of living . It was, however, a 1945 League of Nations report prepared by Folke Hilgerdt and its subsequent follow-up by the United Nations in 1949 that is actually the origin of the Prebisch-Singer hypothesis and the related debate. It was observed in these reports that during the sixty years preceding 1938 primary product prices had fallen relative to prices of manufactures.

In the 1950s both Ra ú l Prebisch and Hans Singer referred to this so-called historical fact and questioned the classical proposition and its implicit support for the colonial pattern of trade. It was pointed out that productivity increased faster in the industrialized countries (constituting the North or the industrial center) than in the primary-producing countries (constituting the South or the raw-material supplying periphery), so that the terms-of-trade should have moved in favor of the South , given the factors of free trade and competition. The South could have enjoyed the fruits of technical progress taking place in industry through free trade and specialization (in primary production) without going for industrialization, as suggested in the classical writings. But this did not happen as the available evidence showed. So the primary-producing countries were advised to pursue a vigorous policy of industrialization with the suspension of the free play of international market forces.

In the post – World War II period, the Prebisch – Singer hypothesis provided the theoretical basis for the policy makers of the newly independent countries to adopt a path of import-substituting industrialization (ISI) through protective commercial policy. The path of ISI in basically agricultural countries required imports of machines and technology. So, in the process of industrialization these countries began to face acute balance-of-payments problems. This led many southern countries to follow the path of export-oriented industrialization. Dependence on a few primary-product exports was reduced and these began to be substituted by manufactured exports.

Meanwhile, the emphasis of the Prebisch – Singer hypothesis shifted from the relations between types of commodities to relations between types of countries. The shift of emphasis too had its origin in the writings of Kindleberger in the mid- to late 1950s. He found no conclusive evidence of deterioration in the terms-of-trade of primary products, but he did have some evidence of a decline in the terms-of-trade of the primary-producing countries (South) vis- à -vis the industrialized countries (North). In fact, both Prebisch and Singer had in mind the concept of terms-of-trade between the North and the South. But, in the absence of appropriate data, they used the series on terms-of-trade between primary products and manufactures as a proxy, with the logic that primary products dominated the then export structure of the South and manufactures dominated that of the North.

The Prebisch-Singer hypothesis generated much controversy in the academic world. In their published papers, critics such as Jacob Viner (1953), R. E. Baldwin (1955), G. M. Meier (1958), G. Haberler (1961), R. E. Lipsey (1963), Harry Johnson (1967), Paul Bairoch (1975), Ronald Findlay (1981), and many others raised different statistical questions and discarded the hypothesis. Since the 1980s, a series of studies undertaken by John Spraos (1980), David Sapsford (1985), Prabirjit Sarkar (1986a, b, 1994, 2005), Sarkar and Singer (1991), E. R. Grilli, and M.C. Yang (1988), and many others questioned the validity of the criticism and provided strong statistical support for the Prebisch – Singer hypothesis, thereby bringing it back into the limelight.

The question that logically follows is what explains the deteriorating trends in the terms-of-trade of the South? The factor highlighted by Singer is the raw-material saving and/or substituting technical progress in the North which created a demand bias against southern exports in the process of growth of northern manufactures leading to a fall in the southern terms-of-trade.

In his 1950 work Prebisch tried to explain the phenomenon in terms of the interaction of the diverse economic structures of the North and the South with different phases of business cycles. In an upswing, wages and profit, and so prices, rise more in the North than in the South due to stronger labor unions and higher monopoly power of the northern capitalists. In the downswing, northern profits and wages do not fall much due to the same reason. The burden of adjustment falls on the raw material suppliers of the South; their prices fall more than the prices of manufactures.

The diverse economic structures created an asymmetry in the mechanism of distribution of the fruits of technical progress, argued Prebisch, Singer, and Arthur Lewis in their individual works published in the 1950s. In the North, technical progress and productivity improvements led to higher wages and profit while in the South, these led to lower prices. The North-South models of Findlay (1980) and Sarkar (1997 and 2001b) supported this asymmetry. Granted this asymmetry, the terms-of-trade would turn against the interest of the South in the process of long-term growth and technical progress in both the North and the South.

In 1997 Sarkar provided another explanation in terms of product cycles. A new product is often introduced in the North. Initially there is a craze for this product and its income elasticity is very high. Owing to a lack of knowledge of its production technique, the South cannot start its production. The South produces comparatively older goods with lower income elasticity. By the time the South acquires the knowledge, the North has introduced another new product. In such a product cycle scenario, the income elasticity of southern demand for northern goods is likely to be higher than that of the northern demand for southern goods. Under these circumstances, if both the North and the South grow at the same rate (or the South tries to catch up by pressing for a higher rate of growth), the global macro balance requires a steady deterioration in the terms-of-trade of the South vis- à -vis the North.

Many other theoretical models exist to explain the Prebisch-Singer hypothesis. As it is increasingly recognized to be a fact, not a myth, many other models will be forthcoming.

SEE ALSO Development Economics; Prebisch, Ra ú l; Singer, Hans; Terms of Trade; Unequal Exchange

Bairoch, Paul. 1975. The Economic Development of the Third World since 1900 . London: Methuen.

Baldwin, R. E. 1955. “ Secular Movements in the Terms of Trade. ” American Economic Review 45: 259 – 269.

Findlay, Ronald. 1980. “ The Terms of Trade and Equilibrium Growth in the World Economy. ” American Economic Review 70: 291 – 299.

Findlay, Ronald. 1981. “ The Fundamental Determinants of the Terms of Trade. ” In The World Economic Order , edited by S. Grassman and E. Lundberg. London: Macmillan: 425 – 457.

Grilli, E. R., and Yang, M. C. 1988. “ Primary Commodity Prices, Manufactured Goods Prices and the Terms of Trade of Developing Countries: What the Long-Run Shows. ” The World Bank Economic Review 2: 1 – 47.

Haberler, G. 1961. “ Terms of Trade and Economic Development. ” In Economic Development for Latin America , edited by H. S. Ellis. London: Macmillan: 275 – 297.

Johnson, Harry. 1967. Economic Policies towards Less Developed Countries . London: Allen & Unwin.

Kindleberger, Charles. 1943. “ Planning for Foreign Investment. ” American Economic Review 33: 347 – 354.

Kindleberger, Charles. 1950. The Dollar Shortage . New York : Wiley.

Kindleberger, Charles. 1956. The Terms of Trade: A European Case Study . New York : Wiley.

Kindleberger, Charles. 1958. “ The Terms of Trade and Economic Development. ” Review of Economics and Statistics 40: 72 – 85.

Kuznets, Simon. 1967. “ Quantitative Aspects of the Economic Growth of Nations ” . Economic Development and Cultural Change 15: 1 – 140.

League of Nations . 1945. Industrialisation and Foreign Trade . Geneva: League of Nations.

Lewis, Arthur. 1954. “ Economic Development with Unlimited Supplies of Labour. ” Manchester School of Economic and Social Studies 22: 139 – 191.

Lipsey, R. E. 1963. Price and Quantity Trends in the Foreign Trade of United States . Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press for NBER.

Meier, G. M. 1958. “ International Trade and International Inequality. ” Oxford Economic Papers 10 (New Series): 277 – 289.

Prebisch, Ra ú l. 1950. The Economic Development of Latin America and Its Principal Problems . New York: United Nations .

Prebisch, Ra ú l. 1959. “ Commercial Policy in the Underdeveloped Countries. ” American Economic Review 49: 251 – 273.

Sapsford, David. 1985. “ Some Further Evidence in the Statistical Debate on the Net Barter Terms of Trade between Primary Commodities and Manufactures. ” Economic Journal 95: 781 – 788.

Sarkar, Prabirjit. 1986a. “ Terms of Trade Experience of Britain since the Nineteenth Century. ” Journal of Development Studies 23: 20 – 39.

Sarkar, Prabirjit. 1986b. “ The Singer – Prebisch Hypothesis: A Statistical Evaluation. ” Cambridge Journal of Economics 10: 355 – 371.

Sarkar, Prabirjit. 1994. “ Long-term Behaviour of Terms of Trade of Primary Products vis- à -vis Manufactures: A Critical Review of Recent Debate. ” Economic and Political Weekly 29: 1612 – 1614.

Sarkar, Prabirjit. 1997. “ Growth and Terms of Trade: A North-South Macroeconomic Framework. ” Journal of Macroeconomics 19: 117 – 133.

Sarkar, Prabirjit. 2001a. “ The North-South Terms of Trade: A Re-examination. ” Progress in Development Studies 1 (4): 309 – 327.

Sarkar, Prabirjit. 2001b. “ Technical Progress and the North-South Terms of Trade. ” Review of Development Economics 5 (3): 433 – 443.

Sarkar, Prabirjit. 2005. “ Rising Manufacture Exports and Terms of Trade: The Case Study of Korea. ” Progress in Development Studies 5 (2): 83 – 88.

Sarkar, Prabirjit, and Singer, Hans. 1991. “ Manufactured Exports of Developing Countries and Their Terms of Trade Since 1965. ” World Development 19: 333 – 340.

Singer, Hans. 1950. “ The Distribution of Gains between Investing and Borrowing Countries. ” American Economic Review 40: 473 – 485.

Spraos, John. 1980. “ The Statistical Debates on the Net Barter Terms of Trade between Primary Commodities and Manufactures. ” Economic Journal 90: 107 – 128.

Spraos, John. 1983. Inequalising Trade? London: Clarendon Press.

United Nations. 1949. Relative Prices of Exports and Imports of Under-developed Countries . New York: United Nations.

Viner, Jacob. 1953. International Trade and Economic Development . Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Prabirjit Sarkar

Cite this article Pick a style below, and copy the text for your bibliography.

" Prebisch-Singer Hypothesis . " International Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences . . Encyclopedia.com. 10 Jul. 2024 < https://www.encyclopedia.com > .

"Prebisch-Singer Hypothesis ." International Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences . . Encyclopedia.com. (July 10, 2024). https://www.encyclopedia.com/social-sciences/applied-and-social-sciences-magazines/prebisch-singer-hypothesis

"Prebisch-Singer Hypothesis ." International Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences . . Retrieved July 10, 2024 from Encyclopedia.com: https://www.encyclopedia.com/social-sciences/applied-and-social-sciences-magazines/prebisch-singer-hypothesis

Citation styles

Encyclopedia.com gives you the ability to cite reference entries and articles according to common styles from the Modern Language Association (MLA), The Chicago Manual of Style, and the American Psychological Association (APA).

Within the “Cite this article” tool, pick a style to see how all available information looks when formatted according to that style. Then, copy and paste the text into your bibliography or works cited list.

Because each style has its own formatting nuances that evolve over time and not all information is available for every reference entry or article, Encyclopedia.com cannot guarantee each citation it generates. Therefore, it’s best to use Encyclopedia.com citations as a starting point before checking the style against your school or publication’s requirements and the most-recent information available at these sites:

Modern Language Association

http://www.mla.org/style

The Chicago Manual of Style

http://www.chicagomanualofstyle.org/tools_citationguide.html

American Psychological Association

http://apastyle.apa.org/

- Most online reference entries and articles do not have page numbers. Therefore, that information is unavailable for most Encyclopedia.com content. However, the date of retrieval is often important. Refer to each style’s convention regarding the best way to format page numbers and retrieval dates.

- In addition to the MLA, Chicago, and APA styles, your school, university, publication, or institution may have its own requirements for citations. Therefore, be sure to refer to those guidelines when editing your bibliography or works cited list.

More From encyclopedia.com

About this article, you might also like.

- Terms of Trade

- Singer, Hans

- Trade Surplus and Trade Deficit

- Economic Policy and Theory

- North-South Models

- Liberalization, Trade

- International Trade Controls

NEARBY TERMS

Quickonomics

Prebisch–Singer Hypothesis

Definition of the prebisch–singer hypothesis.

The Prebisch–Singer hypothesis is a theory in economics that suggests that the terms of trade between primary products and manufactured goods tend to deteriorate over time. This theory, posited by Raúl Prebisch and Hans Singer in the late 1940s and early 1950s, respectively, argues that countries that export commodities (a term closely associated with primary products) will become relatively poorer in comparison to those that export manufactured goods. The hypothesis is based on the observation that the income elasticity of demand for primary products is lower than that for manufactured goods. Thus, in a growing global economy, the prices for primary products will increase at a slower rate than those for manufactured goods, leading to a decline in the terms of trade for countries specializing in the export of commodities.

Consider two countries: Country A specializes in the production and export of copper, a primary commodity, while Country B specializes in the production and export of electronic gadgets, a manufactured product. As the global economy expands, the demand for electronic gadgets (with high-income elasticity) grows faster than the demand for copper (with lower income elasticity). Over time, the price of electronic gadgets increases more rapidly than the price of copper. Consequently, for Country A to purchase the same amount of electronic gadgets from Country B, it needs to export more copper than before. This illustrates the deteriorating terms of trade for Country A, as represented by the Prebisch–Singer hypothesis.

Why the Prebisch–Singer Hypothesis Matters

The Prebisch–Singer hypothesis has significant implications for trade policies and economic development strategies, especially for countries heavily reliant on the export of primary products. It supports the argument for these countries to diversify their economies and to develop their manufacturing sectors. The hypothesis also underpins the rationale for economic policies aimed at protecting infant industries and reducing dependency on commodity exports. It highlights the vulnerability of commodity-exporting countries to volatile global market conditions and the potential benefits of economic diversification and value addition.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

What are the main criticisms of the prebisch–singer hypothesis.

The Prebisch–Singer hypothesis has faced criticism on several fronts. Critics argue that it oversimplifies the dynamics of international trade by not accounting for factors such as technological progress and productivity gains in the primary sector, which can influence the terms of trade. Others suggest that the hypothesis underestimates the capacity of commodity-exporting countries to diversify their economies and to upgrade their production processes. Additionally, some economists have highlighted empirical evidence showing periods during which the terms of trade for primary products improved, contrary to what the hypothesis predicts.

How have some countries responded to the challenges highlighted by the Prebisch–Singer hypothesis?

Some countries have taken proactive steps to mitigate the challenges highlighted by the Prebisch–Singer hypothesis through policies aimed at economic diversification and industrialization. This includes investing in education and technology to improve productivity and competitiveness, implementing policies to support the growth of the manufacturing sector, and pursuing value-added processing of primary products. Countries have also engaged in regional trade agreements to enhance market access for their manufactured goods and reduce dependence on commodity exports.

How does the Prebisch–Singer hypothesis relate to the concept of sustainable development?

The Prebisch–Singer hypothesis is relevant to discussions of sustainable development, particularly in how it underscores the need for economic diversification and resilience in the face of global market volatility. By highlighting the risks associated with over-reliance on primary commodity exports, the hypothesis indirectly points to the importance of pursuing economic development strategies that are environmentally sustainable, economically viable, and socially inclusive. This includes promoting industries that not only generate economic growth but also contribute to environmental conservation and social well-being.

In conclusion, the Prebisch–Singer hypothesis has played a pivotal role in shaping economic thinking and policy-making related to international trade and development. Despite criticisms and challenges to its empirical validity, the core message of promoting economic diversification and reducing dependency on volatile commodity markets remains highly relevant, especially for developing countries seeking to achieve sustainable and inclusive economic growth.

To provide the best experiences, we and our partners use technologies like cookies to store and/or access device information. Consenting to these technologies will allow us and our partners to process personal data such as browsing behavior or unique IDs on this site and show (non-) personalized ads. Not consenting or withdrawing consent, may adversely affect certain features and functions.

Click below to consent to the above or make granular choices. Your choices will be applied to this site only. You can change your settings at any time, including withdrawing your consent, by using the toggles on the Cookie Policy, or by clicking on the manage consent button at the bottom of the screen.

The Prebisch-Singer Terms of Trade Hypothesis: Some (Very) New Evidence

Cite this chapter.

- David Sapsford &

- John-ren Chen

88 Accesses

2 Citations

The chapters in this section of the book are concerned with various dimensions of an hypothesis which has become inextricably associated with the names Hans Singer and Raul Prebisch. According to this hypothesis, which was launched simultaneously by Singer (1950) and Prebisch (1950), the net barter terms of trade between primary products and manufactures have been, and could be expected to continue to be, subject to a downward long-run trend. Being in direct contradiction with the then prevailing orthodoxy, it is not surprising that the Prebisch-Singer hypothesis (P–S hereafter) attracted criticism from a number of quarters. The ensuing debate, which initially focused its attack on the basis of issues related to the treatment of transport costs and quality change, is well summarized by Spraos (1980), who showed that adjustments for shipping costs and changing quality left the hypothesis largely undented, in the sense that they failed to destroy its empirical validity. However, since the mid-1980s the debate surrounding the P–S hypothesis has shifted to the statistical arena. Indeed, such is the interest generated by the hypothesis amongst econometricians and time-series statisticians that it has established itself as one of the major test beds on which they routinely evaluate their latest methods of trend estimation!

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Unable to display preview. Download preview PDF.

Similar content being viewed by others

The Janus Face of Eli Heckscher: Theory, History and Method

Commodity Prices in Empirical Research

Balance of Trade, History of the Theory

Ardeni, P.G. and B. Wright (1992) ‘The Prebisch-Singer Hypothesis: A Reappraisal Independent of Stationarity Hypotheses’, Economic Journal , vol. 102, no. 413 (1992) pp. 803–12.

Article Google Scholar

Bleaney, M. and D. Greenaway (1993) ‘Long-Run Trends in the Relative Price of Primary Commodities and in the Terms of Trade of Developing Countries’, Oxford Economic Papers , vol. 45, no. 3 (Oct.) pp. 349–63.

Google Scholar

Chen, J. (1985) Terms of Trade und Außenhandelsbeziehungen der Entwicklungsländer — eine ökonometrische Studie; Schriften zur angewandten Ökonometrie , Heft 14 (Frankfurt: Haag und Herchen Verlag).

—— (1992) ‘Die Entwicklung der Weltmarktpreise für Rohstoffe von 1960/1 bis 1982/3’, Journal für Entwicklungspolitik , pp. 387–411.

Cuddington, J. and C. Urzua (1989) ‘Trends and Cycles in the Net Barter Terms of Trade: A New Approach’, Economic Journal , vol. 99, no. 396, pp. 426–42.

Grilli, E. and M. C. Yang (1988) ‘Primary Commodity Prices, Manufactured Goods Prices and the Terms of Trade of Developing Countries: What the Long-Run Shows’, World Bank Economic Review , vol. 2, no. 1 (Jan.) pp. 1–47.

Powell, A. (1991) ‘Commodity and Developing Country Terms of Trade: What Does the Long Run Show?’, Economic Journal , vol. 101, no. 409, pp. 1485–96.

Prebisch, Raul (1950) ‘The Economic Development of Latin America and its Principal Problem’, UN ECLA; also published in Economic Bulletin for Latin America , vol. 7, no. 1 (1962) pp. 1–22.

Reinhart, C. and P. Wickham (1994) ‘Commodity Prices: Cyclical Weakness or Secular Decline?’, IME Staff Papers , vol. 41, no. 2, pp. 175–213.

Sapsford, D. (1985) ‘The Statistical Debate on the Net Barter Terms of Trade Between Primary Commodities and Manufactures: A Comment and Some Additional Evidence’, Economic Journal , vol. 95, no. 379 (Sep.) pp. 781–8.

—— (1990) ‘Primary Commodity Prices and the Terms of Trade’, Economic Record , vol. 66, no. 195, pp. 342–56.

—— and V.N. Balasubramanyam (1994) ‘The Long-Run Behavior of the Relative Price of Primary Commodities: Statistical Evidence and Policy Implications’, World Development , vol. 22, no. 11, pp. 1737–45.

—— P. Sarkar and H. Singer (1992) ‘The Prebisch-Singer Terms of Trade Controversy Revisited’, Journal of International Development , vol. 4, no. 3 (May) pp. 315–32.

Singer, H. (1950) ‘The Distribution of Gains Between Investing and Borrowing Countries’, American Economic Review, Papers and Proceedings , vol. 40 (May) pp. 473–85.

Spraos, J. (1980) ‘The Statistical Debate on the Net Barter Terms of Trade Between Primary Products and Manufactures’, Economic Journal , vol. 90, no. 357 (Jan.) pp. 107–28.

Thirlwall, T. and J. Bergevin (1985) ‘Trend, Cycles and Asymmetries in the Terms of Trade of Primary Commodities from Developed and Less Developed Countries’, World Development , vol. 13, no. 7 (Jul.) pp. 805–17.

Download references

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Lancaster University, England

David Sapsford ( Professor of Economics ) ( Professor of Economics )

University of Innsbruck, Austria

John-ren Chen ( Professor of Economics ) ( Professor of Economics )

Copyright information

© 1998 David Sapsford and John-ren Chen

About this chapter

Sapsford, D., Chen, Jr. (1998). The Prebisch-Singer Terms of Trade Hypothesis: Some (Very) New Evidence. In: Sapsford, D., Chen, Jr. (eds) Development Economics and Policy. Palgrave Macmillan, London. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-349-26769-9_3

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-349-26769-9_3

Publisher Name : Palgrave Macmillan, London

Print ISBN : 978-1-349-26771-2

Online ISBN : 978-1-349-26769-9

eBook Packages : Palgrave Economics & Finance Collection Economics and Finance (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Search Menu

Sign in through your institution

- Browse content in A - General Economics and Teaching

- Browse content in A1 - General Economics

- A10 - General

- A11 - Role of Economics; Role of Economists; Market for Economists

- A12 - Relation of Economics to Other Disciplines

- A13 - Relation of Economics to Social Values

- A14 - Sociology of Economics

- Browse content in A2 - Economic Education and Teaching of Economics

- A20 - General

- A29 - Other

- A3 - Collective Works

- Browse content in B - History of Economic Thought, Methodology, and Heterodox Approaches

- Browse content in B0 - General

- B00 - General

- Browse content in B1 - History of Economic Thought through 1925

- B10 - General

- B11 - Preclassical (Ancient, Medieval, Mercantilist, Physiocratic)

- B12 - Classical (includes Adam Smith)

- B13 - Neoclassical through 1925 (Austrian, Marshallian, Walrasian, Stockholm School)

- B14 - Socialist; Marxist

- B15 - Historical; Institutional; Evolutionary

- B16 - History of Economic Thought: Quantitative and Mathematical

- B17 - International Trade and Finance

- B19 - Other

- Browse content in B2 - History of Economic Thought since 1925

- B20 - General

- B21 - Microeconomics

- B22 - Macroeconomics

- B23 - Econometrics; Quantitative and Mathematical Studies

- B24 - Socialist; Marxist; Sraffian

- B25 - Historical; Institutional; Evolutionary; Austrian

- B26 - Financial Economics

- B27 - International Trade and Finance

- B29 - Other

- Browse content in B3 - History of Economic Thought: Individuals

- B30 - General

- B31 - Individuals

- Browse content in B4 - Economic Methodology

- B40 - General

- B41 - Economic Methodology

- B49 - Other

- Browse content in B5 - Current Heterodox Approaches

- B50 - General

- B51 - Socialist; Marxian; Sraffian

- B52 - Institutional; Evolutionary

- B53 - Austrian

- B54 - Feminist Economics

- B55 - Social Economics

- B59 - Other

- Browse content in C - Mathematical and Quantitative Methods

- Browse content in C0 - General

- C00 - General

- C02 - Mathematical Methods

- Browse content in C1 - Econometric and Statistical Methods and Methodology: General

- C10 - General

- C12 - Hypothesis Testing: General

- C13 - Estimation: General

- C14 - Semiparametric and Nonparametric Methods: General

- C18 - Methodological Issues: General

- C19 - Other

- Browse content in C2 - Single Equation Models; Single Variables

- C20 - General

- C21 - Cross-Sectional Models; Spatial Models; Treatment Effect Models; Quantile Regressions

- C22 - Time-Series Models; Dynamic Quantile Regressions; Dynamic Treatment Effect Models; Diffusion Processes

- C23 - Panel Data Models; Spatio-temporal Models

- C25 - Discrete Regression and Qualitative Choice Models; Discrete Regressors; Proportions; Probabilities

- Browse content in C3 - Multiple or Simultaneous Equation Models; Multiple Variables

- C30 - General

- C32 - Time-Series Models; Dynamic Quantile Regressions; Dynamic Treatment Effect Models; Diffusion Processes; State Space Models

- C34 - Truncated and Censored Models; Switching Regression Models

- C38 - Classification Methods; Cluster Analysis; Principal Components; Factor Models

- Browse content in C4 - Econometric and Statistical Methods: Special Topics

- C43 - Index Numbers and Aggregation

- C44 - Operations Research; Statistical Decision Theory

- Browse content in C5 - Econometric Modeling

- C50 - General

- Browse content in C6 - Mathematical Methods; Programming Models; Mathematical and Simulation Modeling

- C60 - General

- C61 - Optimization Techniques; Programming Models; Dynamic Analysis

- C62 - Existence and Stability Conditions of Equilibrium

- C63 - Computational Techniques; Simulation Modeling

- C65 - Miscellaneous Mathematical Tools

- C67 - Input-Output Models

- Browse content in C8 - Data Collection and Data Estimation Methodology; Computer Programs

- C82 - Methodology for Collecting, Estimating, and Organizing Macroeconomic Data; Data Access

- C89 - Other

- Browse content in C9 - Design of Experiments

- C90 - General

- C91 - Laboratory, Individual Behavior

- C92 - Laboratory, Group Behavior

- C93 - Field Experiments

- Browse content in D - Microeconomics

- Browse content in D0 - General

- D01 - Microeconomic Behavior: Underlying Principles

- D02 - Institutions: Design, Formation, Operations, and Impact

- D03 - Behavioral Microeconomics: Underlying Principles

- Browse content in D1 - Household Behavior and Family Economics

- D10 - General

- D11 - Consumer Economics: Theory

- D12 - Consumer Economics: Empirical Analysis

- D13 - Household Production and Intrahousehold Allocation

- D14 - Household Saving; Personal Finance

- Browse content in D2 - Production and Organizations

- D20 - General

- D21 - Firm Behavior: Theory

- D22 - Firm Behavior: Empirical Analysis

- D23 - Organizational Behavior; Transaction Costs; Property Rights

- D24 - Production; Cost; Capital; Capital, Total Factor, and Multifactor Productivity; Capacity

- D25 - Intertemporal Firm Choice: Investment, Capacity, and Financing

- Browse content in D3 - Distribution

- D30 - General

- D31 - Personal Income, Wealth, and Their Distributions

- D33 - Factor Income Distribution

- D39 - Other

- Browse content in D4 - Market Structure, Pricing, and Design

- D40 - General

- D41 - Perfect Competition

- D42 - Monopoly

- D43 - Oligopoly and Other Forms of Market Imperfection

- D46 - Value Theory

- Browse content in D5 - General Equilibrium and Disequilibrium

- D50 - General

- D51 - Exchange and Production Economies

- D57 - Input-Output Tables and Analysis

- D58 - Computable and Other Applied General Equilibrium Models

- Browse content in D6 - Welfare Economics

- D60 - General

- D61 - Allocative Efficiency; Cost-Benefit Analysis

- D62 - Externalities

- D63 - Equity, Justice, Inequality, and Other Normative Criteria and Measurement

- D64 - Altruism; Philanthropy

- D69 - Other

- Browse content in D7 - Analysis of Collective Decision-Making

- D71 - Social Choice; Clubs; Committees; Associations

- D72 - Political Processes: Rent-seeking, Lobbying, Elections, Legislatures, and Voting Behavior

- D73 - Bureaucracy; Administrative Processes in Public Organizations; Corruption

- D74 - Conflict; Conflict Resolution; Alliances; Revolutions

- Browse content in D8 - Information, Knowledge, and Uncertainty

- D80 - General

- D81 - Criteria for Decision-Making under Risk and Uncertainty

- D82 - Asymmetric and Private Information; Mechanism Design

- D83 - Search; Learning; Information and Knowledge; Communication; Belief; Unawareness

- D84 - Expectations; Speculations

- D85 - Network Formation and Analysis: Theory

- D86 - Economics of Contract: Theory

- D87 - Neuroeconomics

- Browse content in D9 - Micro-Based Behavioral Economics

- D91 - Role and Effects of Psychological, Emotional, Social, and Cognitive Factors on Decision Making

- Browse content in E - Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Browse content in E0 - General

- E00 - General

- E01 - Measurement and Data on National Income and Product Accounts and Wealth; Environmental Accounts

- E02 - Institutions and the Macroeconomy

- Browse content in E1 - General Aggregative Models

- E10 - General

- E11 - Marxian; Sraffian; Kaleckian

- E12 - Keynes; Keynesian; Post-Keynesian

- E13 - Neoclassical

- E16 - Social Accounting Matrix

- E17 - Forecasting and Simulation: Models and Applications

- Browse content in E2 - Consumption, Saving, Production, Investment, Labor Markets, and Informal Economy

- E20 - General

- E21 - Consumption; Saving; Wealth

- E22 - Investment; Capital; Intangible Capital; Capacity

- E23 - Production

- E24 - Employment; Unemployment; Wages; Intergenerational Income Distribution; Aggregate Human Capital; Aggregate Labor Productivity

- E25 - Aggregate Factor Income Distribution

- E26 - Informal Economy; Underground Economy

- E27 - Forecasting and Simulation: Models and Applications

- Browse content in E3 - Prices, Business Fluctuations, and Cycles

- E30 - General

- E31 - Price Level; Inflation; Deflation

- E32 - Business Fluctuations; Cycles

- E37 - Forecasting and Simulation: Models and Applications

- Browse content in E4 - Money and Interest Rates

- E40 - General

- E41 - Demand for Money

- E42 - Monetary Systems; Standards; Regimes; Government and the Monetary System; Payment Systems

- E43 - Interest Rates: Determination, Term Structure, and Effects

- E44 - Financial Markets and the Macroeconomy

- E49 - Other

- Browse content in E5 - Monetary Policy, Central Banking, and the Supply of Money and Credit

- E50 - General

- E51 - Money Supply; Credit; Money Multipliers

- E52 - Monetary Policy

- E58 - Central Banks and Their Policies

- Browse content in E6 - Macroeconomic Policy, Macroeconomic Aspects of Public Finance, and General Outlook

- E60 - General

- E61 - Policy Objectives; Policy Designs and Consistency; Policy Coordination

- E62 - Fiscal Policy

- E63 - Comparative or Joint Analysis of Fiscal and Monetary Policy; Stabilization; Treasury Policy

- E64 - Incomes Policy; Price Policy

- E65 - Studies of Particular Policy Episodes

- Browse content in F - International Economics

- Browse content in F0 - General

- F00 - General

- F01 - Global Outlook

- F02 - International Economic Order and Integration

- Browse content in F1 - Trade

- F10 - General

- F11 - Neoclassical Models of Trade

- F12 - Models of Trade with Imperfect Competition and Scale Economies; Fragmentation

- F13 - Trade Policy; International Trade Organizations

- F14 - Empirical Studies of Trade

- F15 - Economic Integration

- F16 - Trade and Labor Market Interactions

- F17 - Trade Forecasting and Simulation

- F18 - Trade and Environment

- Browse content in F2 - International Factor Movements and International Business

- F20 - General

- F21 - International Investment; Long-Term Capital Movements

- F22 - International Migration

- F23 - Multinational Firms; International Business

- Browse content in F3 - International Finance

- F30 - General

- F31 - Foreign Exchange

- F32 - Current Account Adjustment; Short-Term Capital Movements

- F33 - International Monetary Arrangements and Institutions

- F34 - International Lending and Debt Problems

- F35 - Foreign Aid

- F36 - Financial Aspects of Economic Integration

- F37 - International Finance Forecasting and Simulation: Models and Applications

- F39 - Other

- Browse content in F4 - Macroeconomic Aspects of International Trade and Finance

- F40 - General

- F41 - Open Economy Macroeconomics

- F42 - International Policy Coordination and Transmission

- F43 - Economic Growth of Open Economies

- F44 - International Business Cycles

- F45 - Macroeconomic Issues of Monetary Unions

- F47 - Forecasting and Simulation: Models and Applications

- Browse content in F5 - International Relations, National Security, and International Political Economy

- F50 - General

- F51 - International Conflicts; Negotiations; Sanctions

- F53 - International Agreements and Observance; International Organizations

- F54 - Colonialism; Imperialism; Postcolonialism

- F55 - International Institutional Arrangements

- F59 - Other

- Browse content in F6 - Economic Impacts of Globalization

- F60 - General

- F61 - Microeconomic Impacts

- F62 - Macroeconomic Impacts

- F63 - Economic Development

- F64 - Environment

- F65 - Finance

- Browse content in G - Financial Economics

- Browse content in G0 - General

- G00 - General

- G01 - Financial Crises

- Browse content in G1 - General Financial Markets

- G10 - General

- G11 - Portfolio Choice; Investment Decisions

- G12 - Asset Pricing; Trading volume; Bond Interest Rates

- G13 - Contingent Pricing; Futures Pricing

- G14 - Information and Market Efficiency; Event Studies; Insider Trading

- G15 - International Financial Markets

- G18 - Government Policy and Regulation

- G19 - Other

- Browse content in G2 - Financial Institutions and Services

- G20 - General

- G21 - Banks; Depository Institutions; Micro Finance Institutions; Mortgages

- G22 - Insurance; Insurance Companies; Actuarial Studies

- G23 - Non-bank Financial Institutions; Financial Instruments; Institutional Investors

- G24 - Investment Banking; Venture Capital; Brokerage; Ratings and Ratings Agencies

- G28 - Government Policy and Regulation

- Browse content in G3 - Corporate Finance and Governance

- G30 - General

- G32 - Financing Policy; Financial Risk and Risk Management; Capital and Ownership Structure; Value of Firms; Goodwill

- G33 - Bankruptcy; Liquidation

- G34 - Mergers; Acquisitions; Restructuring; Corporate Governance

- G35 - Payout Policy

- G38 - Government Policy and Regulation

- Browse content in G5 - Household Finance

- G51 - Household Saving, Borrowing, Debt, and Wealth

- Browse content in H - Public Economics

- Browse content in H1 - Structure and Scope of Government

- H10 - General

- H11 - Structure, Scope, and Performance of Government

- H12 - Crisis Management

- Browse content in H2 - Taxation, Subsidies, and Revenue

- H20 - General

- H22 - Incidence

- H23 - Externalities; Redistributive Effects; Environmental Taxes and Subsidies

- H25 - Business Taxes and Subsidies

- H26 - Tax Evasion and Avoidance

- Browse content in H3 - Fiscal Policies and Behavior of Economic Agents

- Browse content in H4 - Publicly Provided Goods

- H40 - General

- H41 - Public Goods

- Browse content in H5 - National Government Expenditures and Related Policies

- H50 - General

- H53 - Government Expenditures and Welfare Programs

- H55 - Social Security and Public Pensions

- H56 - National Security and War

- Browse content in H6 - National Budget, Deficit, and Debt

- H60 - General

- H62 - Deficit; Surplus

- H63 - Debt; Debt Management; Sovereign Debt

- H68 - Forecasts of Budgets, Deficits, and Debt

- Browse content in H7 - State and Local Government; Intergovernmental Relations

- H70 - General

- H74 - State and Local Borrowing

- H77 - Intergovernmental Relations; Federalism; Secession

- Browse content in I - Health, Education, and Welfare

- Browse content in I0 - General

- I00 - General

- Browse content in I1 - Health

- I10 - General

- I12 - Health Behavior

- I14 - Health and Inequality

- I15 - Health and Economic Development

- Browse content in I2 - Education and Research Institutions

- I20 - General

- I21 - Analysis of Education

- I23 - Higher Education; Research Institutions

- I24 - Education and Inequality

- I26 - Returns to Education

- Browse content in I3 - Welfare, Well-Being, and Poverty

- I30 - General

- I31 - General Welfare

- I32 - Measurement and Analysis of Poverty

- I38 - Government Policy; Provision and Effects of Welfare Programs

- Browse content in J - Labor and Demographic Economics

- Browse content in J0 - General

- J00 - General

- J01 - Labor Economics: General

- J08 - Labor Economics Policies

- Browse content in J1 - Demographic Economics

- J10 - General

- J13 - Fertility; Family Planning; Child Care; Children; Youth

- J15 - Economics of Minorities, Races, Indigenous Peoples, and Immigrants; Non-labor Discrimination

- J16 - Economics of Gender; Non-labor Discrimination

- J18 - Public Policy

- Browse content in J2 - Demand and Supply of Labor

- J20 - General

- J21 - Labor Force and Employment, Size, and Structure

- J22 - Time Allocation and Labor Supply

- J23 - Labor Demand

- J24 - Human Capital; Skills; Occupational Choice; Labor Productivity

- J26 - Retirement; Retirement Policies

- J28 - Safety; Job Satisfaction; Related Public Policy

- J29 - Other

- Browse content in J3 - Wages, Compensation, and Labor Costs

- J30 - General

- J31 - Wage Level and Structure; Wage Differentials

- J32 - Nonwage Labor Costs and Benefits; Retirement Plans; Private Pensions

- J33 - Compensation Packages; Payment Methods

- J38 - Public Policy

- Browse content in J4 - Particular Labor Markets

- J40 - General

- J41 - Labor Contracts

- J42 - Monopsony; Segmented Labor Markets

- J44 - Professional Labor Markets; Occupational Licensing

- J45 - Public Sector Labor Markets

- J46 - Informal Labor Markets

- J48 - Public Policy

- J49 - Other

- Browse content in J5 - Labor-Management Relations, Trade Unions, and Collective Bargaining

- J50 - General

- J51 - Trade Unions: Objectives, Structure, and Effects

- J52 - Dispute Resolution: Strikes, Arbitration, and Mediation; Collective Bargaining

- J53 - Labor-Management Relations; Industrial Jurisprudence

- J54 - Producer Cooperatives; Labor Managed Firms; Employee Ownership

- J58 - Public Policy

- Browse content in J6 - Mobility, Unemployment, Vacancies, and Immigrant Workers

- J60 - General

- J61 - Geographic Labor Mobility; Immigrant Workers

- J62 - Job, Occupational, and Intergenerational Mobility

- J63 - Turnover; Vacancies; Layoffs

- J64 - Unemployment: Models, Duration, Incidence, and Job Search

- J65 - Unemployment Insurance; Severance Pay; Plant Closings

- J68 - Public Policy

- J69 - Other

- Browse content in J7 - Labor Discrimination

- J71 - Discrimination

- J78 - Public Policy

- Browse content in J8 - Labor Standards: National and International

- J80 - General

- J81 - Working Conditions

- J83 - Workers' Rights

- J88 - Public Policy

- Browse content in K - Law and Economics

- Browse content in K0 - General

- K00 - General

- Browse content in K1 - Basic Areas of Law

- K11 - Property Law

- K12 - Contract Law

- K13 - Tort Law and Product Liability; Forensic Economics

- Browse content in K2 - Regulation and Business Law

- K20 - General

- K21 - Antitrust Law

- K22 - Business and Securities Law

- K23 - Regulated Industries and Administrative Law

- K25 - Real Estate Law

- Browse content in K3 - Other Substantive Areas of Law

- K31 - Labor Law

- K39 - Other

- Browse content in K4 - Legal Procedure, the Legal System, and Illegal Behavior

- K40 - General

- K41 - Litigation Process

- K42 - Illegal Behavior and the Enforcement of Law

- Browse content in L - Industrial Organization

- Browse content in L0 - General

- L00 - General

- Browse content in L1 - Market Structure, Firm Strategy, and Market Performance

- L10 - General

- L11 - Production, Pricing, and Market Structure; Size Distribution of Firms

- L12 - Monopoly; Monopolization Strategies

- L13 - Oligopoly and Other Imperfect Markets

- L14 - Transactional Relationships; Contracts and Reputation; Networks

- L16 - Industrial Organization and Macroeconomics: Industrial Structure and Structural Change; Industrial Price Indices

- Browse content in L2 - Firm Objectives, Organization, and Behavior

- L20 - General

- L21 - Business Objectives of the Firm

- L22 - Firm Organization and Market Structure

- L23 - Organization of Production

- L24 - Contracting Out; Joint Ventures; Technology Licensing

- L25 - Firm Performance: Size, Diversification, and Scope

- L26 - Entrepreneurship

- L29 - Other

- Browse content in L3 - Nonprofit Organizations and Public Enterprise

- L30 - General

- L31 - Nonprofit Institutions; NGOs; Social Entrepreneurship

- L32 - Public Enterprises; Public-Private Enterprises

- L33 - Comparison of Public and Private Enterprises and Nonprofit Institutions; Privatization; Contracting Out

- L39 - Other

- Browse content in L4 - Antitrust Issues and Policies

- L40 - General

- L41 - Monopolization; Horizontal Anticompetitive Practices

- L44 - Antitrust Policy and Public Enterprises, Nonprofit Institutions, and Professional Organizations

- Browse content in L5 - Regulation and Industrial Policy

- L50 - General

- L52 - Industrial Policy; Sectoral Planning Methods

- Browse content in L6 - Industry Studies: Manufacturing

- L60 - General

- L61 - Metals and Metal Products; Cement; Glass; Ceramics

- L66 - Food; Beverages; Cosmetics; Tobacco; Wine and Spirits

- L67 - Other Consumer Nondurables: Clothing, Textiles, Shoes, and Leather Goods; Household Goods; Sports Equipment

- Browse content in L7 - Industry Studies: Primary Products and Construction

- L78 - Government Policy

- Browse content in L8 - Industry Studies: Services

- L80 - General

- L82 - Entertainment; Media

- Browse content in L9 - Industry Studies: Transportation and Utilities

- L97 - Utilities: General

- L98 - Government Policy

- Browse content in M - Business Administration and Business Economics; Marketing; Accounting; Personnel Economics

- Browse content in M0 - General

- M00 - General

- Browse content in M1 - Business Administration

- M10 - General

- M12 - Personnel Management; Executives; Executive Compensation

- M13 - New Firms; Startups

- M16 - International Business Administration

- Browse content in M2 - Business Economics

- M21 - Business Economics

- Browse content in M3 - Marketing and Advertising

- M37 - Advertising

- Browse content in M4 - Accounting and Auditing

- M41 - Accounting

- M49 - Other

- Browse content in M5 - Personnel Economics

- M51 - Firm Employment Decisions; Promotions

- M52 - Compensation and Compensation Methods and Their Effects

- M54 - Labor Management

- M55 - Labor Contracting Devices

- Browse content in N - Economic History

- Browse content in N0 - General

- N00 - General

- N01 - Development of the Discipline: Historiographical; Sources and Methods

- Browse content in N1 - Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics; Industrial Structure; Growth; Fluctuations

- N10 - General, International, or Comparative

- N11 - U.S.; Canada: Pre-1913

- N12 - U.S.; Canada: 1913-

- N13 - Europe: Pre-1913

- N14 - Europe: 1913-

- N15 - Asia including Middle East

- N17 - Africa; Oceania

- Browse content in N2 - Financial Markets and Institutions

- N20 - General, International, or Comparative

- N23 - Europe: Pre-1913

- N24 - Europe: 1913-

- N25 - Asia including Middle East

- N26 - Latin America; Caribbean

- Browse content in N3 - Labor and Consumers, Demography, Education, Health, Welfare, Income, Wealth, Religion, and Philanthropy

- N30 - General, International, or Comparative

- N32 - U.S.; Canada: 1913-

- N34 - Europe: 1913-

- Browse content in N4 - Government, War, Law, International Relations, and Regulation

- N43 - Europe: Pre-1913

- Browse content in N5 - Agriculture, Natural Resources, Environment, and Extractive Industries

- N50 - General, International, or Comparative

- N51 - U.S.; Canada: Pre-1913

- N52 - U.S.; Canada: 1913-

- N55 - Asia including Middle East

- N7 - Transport, Trade, Energy, Technology, and Other Services

- Browse content in N8 - Micro-Business History

- N80 - General, International, or Comparative

- Browse content in O - Economic Development, Innovation, Technological Change, and Growth

- Browse content in O1 - Economic Development

- O10 - General

- O11 - Macroeconomic Analyses of Economic Development

- O12 - Microeconomic Analyses of Economic Development

- O13 - Agriculture; Natural Resources; Energy; Environment; Other Primary Products

- O14 - Industrialization; Manufacturing and Service Industries; Choice of Technology

- O15 - Human Resources; Human Development; Income Distribution; Migration

- O16 - Financial Markets; Saving and Capital Investment; Corporate Finance and Governance

- O17 - Formal and Informal Sectors; Shadow Economy; Institutional Arrangements

- O18 - Urban, Rural, Regional, and Transportation Analysis; Housing; Infrastructure

- O19 - International Linkages to Development; Role of International Organizations

- Browse content in O2 - Development Planning and Policy

- O20 - General

- O23 - Fiscal and Monetary Policy in Development

- O24 - Trade Policy; Factor Movement Policy; Foreign Exchange Policy

- O25 - Industrial Policy

- Browse content in O3 - Innovation; Research and Development; Technological Change; Intellectual Property Rights

- O30 - General

- O31 - Innovation and Invention: Processes and Incentives

- O32 - Management of Technological Innovation and R&D

- O33 - Technological Change: Choices and Consequences; Diffusion Processes

- O34 - Intellectual Property and Intellectual Capital

- O35 - Social Innovation

- O38 - Government Policy

- O39 - Other

- Browse content in O4 - Economic Growth and Aggregate Productivity

- O40 - General

- O41 - One, Two, and Multisector Growth Models

- O43 - Institutions and Growth

- O44 - Environment and Growth

- O47 - Empirical Studies of Economic Growth; Aggregate Productivity; Cross-Country Output Convergence

- Browse content in O5 - Economywide Country Studies

- O50 - General

- O51 - U.S.; Canada

- O52 - Europe

- O53 - Asia including Middle East

- O54 - Latin America; Caribbean

- O55 - Africa

- Browse content in P - Economic Systems

- Browse content in P0 - General

- P00 - General

- Browse content in P1 - Capitalist Systems

- P10 - General

- P11 - Planning, Coordination, and Reform

- P12 - Capitalist Enterprises

- P13 - Cooperative Enterprises

- P14 - Property Rights

- P16 - Political Economy

- P17 - Performance and Prospects

- Browse content in P2 - Socialist Systems and Transitional Economies

- P20 - General

- P21 - Planning, Coordination, and Reform

- P25 - Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Browse content in P3 - Socialist Institutions and Their Transitions

- P30 - General

- P31 - Socialist Enterprises and Their Transitions

- P32 - Collectives; Communes; Agriculture

- P35 - Public Economics

- P36 - Consumer Economics; Health; Education and Training; Welfare, Income, Wealth, and Poverty

- P37 - Legal Institutions; Illegal Behavior

- Browse content in P4 - Other Economic Systems

- P40 - General

- P41 - Planning, Coordination, and Reform

- P46 - Consumer Economics; Health; Education and Training; Welfare, Income, Wealth, and Poverty

- P48 - Political Economy; Legal Institutions; Property Rights; Natural Resources; Energy; Environment; Regional Studies

- Browse content in P5 - Comparative Economic Systems

- P50 - General

- P51 - Comparative Analysis of Economic Systems

- P52 - Comparative Studies of Particular Economies

- Browse content in Q - Agricultural and Natural Resource Economics; Environmental and Ecological Economics

- Browse content in Q0 - General

- Q00 - General

- Q01 - Sustainable Development

- Browse content in Q1 - Agriculture

- Q15 - Land Ownership and Tenure; Land Reform; Land Use; Irrigation; Agriculture and Environment

- Q18 - Agricultural Policy; Food Policy

- Browse content in Q3 - Nonrenewable Resources and Conservation

- Q30 - General

- Browse content in Q4 - Energy

- Q41 - Demand and Supply; Prices

- Q42 - Alternative Energy Sources

- Q48 - Government Policy

- Browse content in Q5 - Environmental Economics

- Q50 - General

- Q54 - Climate; Natural Disasters; Global Warming

- Q56 - Environment and Development; Environment and Trade; Sustainability; Environmental Accounts and Accounting; Environmental Equity; Population Growth

- Q57 - Ecological Economics: Ecosystem Services; Biodiversity Conservation; Bioeconomics; Industrial Ecology

- Browse content in R - Urban, Rural, Regional, Real Estate, and Transportation Economics

- Browse content in R0 - General

- R00 - General

- Browse content in R1 - General Regional Economics

- R10 - General

- R11 - Regional Economic Activity: Growth, Development, Environmental Issues, and Changes

- R12 - Size and Spatial Distributions of Regional Economic Activity

- R15 - Econometric and Input-Output Models; Other Models

- Browse content in R2 - Household Analysis

- R20 - General

- Browse content in R3 - Real Estate Markets, Spatial Production Analysis, and Firm Location

- R30 - General

- R31 - Housing Supply and Markets

- R4 - Transportation Economics

- Browse content in R5 - Regional Government Analysis

- R51 - Finance in Urban and Rural Economies

- R58 - Regional Development Planning and Policy

- Browse content in Y - Miscellaneous Categories

- Browse content in Y1 - Data: Tables and Charts

- Y10 - Data: Tables and Charts

- Browse content in Y3 - Book Reviews (unclassified)

- Y30 - Book Reviews (unclassified)

- Browse content in Y8 - Related Disciplines

- Y80 - Related Disciplines

- Browse content in Z - Other Special Topics

- Browse content in Z0 - General

- Z00 - General

- Browse content in Z1 - Cultural Economics; Economic Sociology; Economic Anthropology

- Z10 - General

- Z11 - Economics of the Arts and Literature

- Z12 - Religion

- Z13 - Economic Sociology; Economic Anthropology; Social and Economic Stratification

- Z18 - Public Policy

- Browse content in Z2 - Sports Economics

- Z29 - Other

- Advance articles

- Editor's Choice

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access

- About Cambridge Journal of Economics

- About the Cambridge Political Economy Society

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Terms and Conditions

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

- < Previous

Revisiting Prebisch and Singer: beyond the declining terms of trade thesis and on to technological capability development

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

P. Sai-wing Ho, Revisiting Prebisch and Singer: beyond the declining terms of trade thesis and on to technological capability development, Cambridge Journal of Economics , Volume 36, Issue 4, July 2012, Pages 869–893, https://doi.org/10.1093/cje/bes011

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Rather than the thesis of a secular decline in the commodity terms of trade, Prebisch and Singer were more concerned with the income terms of trade. Consequently, they advocated (moderate) import substitution (IS) and recommended having it interweaved with export promotion (EP). To avoid technological dependence but achieve integrated industrialisation while coordinating IS with EP, Prebisch emphasised enhancing indigenous ‘technological densities’ and Singer stressed building the indigenous ‘capacities to create wealth’. That means while foreign direct investments should be attracted, those activities should be managed and directed accordingly. Prebisch hoped to narrow the gap in centre–periphery technological uneven development while Singer aimed at tackling international dualism between rich and poor countries in the use of science and technology.

Personal account

- Sign in with email/username & password

- Get email alerts

- Save searches

- Purchase content

- Activate your purchase/trial code

- Add your ORCID iD

Institutional access

Sign in with a library card.

- Sign in with username/password

- Recommend to your librarian

- Institutional account management

- Get help with access

Access to content on Oxford Academic is often provided through institutional subscriptions and purchases. If you are a member of an institution with an active account, you may be able to access content in one of the following ways:

IP based access

Typically, access is provided across an institutional network to a range of IP addresses. This authentication occurs automatically, and it is not possible to sign out of an IP authenticated account.

Choose this option to get remote access when outside your institution. Shibboleth/Open Athens technology is used to provide single sign-on between your institution’s website and Oxford Academic.

- Click Sign in through your institution.

- Select your institution from the list provided, which will take you to your institution's website to sign in.

- When on the institution site, please use the credentials provided by your institution. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

- Following successful sign in, you will be returned to Oxford Academic.

If your institution is not listed or you cannot sign in to your institution’s website, please contact your librarian or administrator.

Enter your library card number to sign in. If you cannot sign in, please contact your librarian.

Society Members

Society member access to a journal is achieved in one of the following ways:

Sign in through society site

Many societies offer single sign-on between the society website and Oxford Academic. If you see ‘Sign in through society site’ in the sign in pane within a journal:

- Click Sign in through society site.

- When on the society site, please use the credentials provided by that society. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

If you do not have a society account or have forgotten your username or password, please contact your society.

Sign in using a personal account

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members. See below.

A personal account can be used to get email alerts, save searches, purchase content, and activate subscriptions.

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members.

Viewing your signed in accounts

Click the account icon in the top right to:

- View your signed in personal account and access account management features.

- View the institutional accounts that are providing access.

Signed in but can't access content

Oxford Academic is home to a wide variety of products. The institutional subscription may not cover the content that you are trying to access. If you believe you should have access to that content, please contact your librarian.

For librarians and administrators, your personal account also provides access to institutional account management. Here you will find options to view and activate subscriptions, manage institutional settings and access options, access usage statistics, and more.

Short-term Access

To purchase short-term access, please sign in to your personal account above.

Don't already have a personal account? Register

| Month: | Total Views: |

|---|---|