- Tools and Resources

- Customer Services

- Original Language Spotlight

- Alternative and Non-formal Education

- Cognition, Emotion, and Learning

- Curriculum and Pedagogy

- Education and Society

- Education, Change, and Development

- Education, Cultures, and Ethnicities

- Education, Gender, and Sexualities

- Education, Health, and Social Services

- Educational Administration and Leadership

- Educational History

- Educational Politics and Policy

- Educational Purposes and Ideals

- Educational Systems

- Educational Theories and Philosophies

- Globalization, Economics, and Education

- Languages and Literacies

- Professional Learning and Development

- Research and Assessment Methods

- Technology and Education

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Article contents

Youth and media culture.

- Stuart R. Poyntz Stuart R. Poyntz Simon Fraser University

- and Jennesia Pedri Jennesia Pedri Simon Fraser University

- https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190264093.013.75

- Published online: 24 January 2018

Media in the 21st century are changing when, where, what, and how young people learn. Some educators, youth researchers, and parents lament this reality; but youth, media culture, and learning nevertheless remain entangled in a rich set of relationships today. These relationships and the anxieties they produce are not new; they echo worries about the consequences of young people’s media attachments that have been around for decades.

These anxieties first appeared in response to the fear that violence, vulgarity, and sexual desire in early popular culture was thought to pose to culture. Others, however, believed that media could be repurposed to have a broader educational impact. This sentiment crept into educational discourses throughout the 1960s in a way that would shift thinking about youth, media culture, and education. For example, it shaped the development of television shows such as Sesame Street as a kind of learning portal. In addition to the idea that youth can learn from the media, educators and activists have also turned to media education as a more direct intervention. Media education addresses how various media operate in and through particular institutions, technologies, texts, and audiences in an effort to affect how young people learn and engage with media culture. These developments have been enhanced by a growing interest in a broad project of literacy. By the 1990s and 2000s, media production became a common feature in media education practices because it was thought to enable young people to learn by doing , rather than just by analyzing or reading texts. This was enabled by the emergence of new digital media technologies that prioritize user participation.

As we have come to read and write media differently in a digital era, however, a new set of problems have arisen that affect how media cultures are understood in relation to learning. Among these issues is how a participatory turn in media culture allows others, including corporations, governments, and predatory individuals, to monitor, survey, coordinate, and guide our activities as never before. Critical media literacy education addresses this context and continues to provide a framework to address the future of youth, media culture and learning.

- media culture

- media literacy

- consumer culture

Introduction

It would be absurd for teenagers today to forgo the Internet as a resource for schoolwork and learning experiences of all sorts. Whether to research an essay, acquire new skills, find an expert, watch a video clip, or contribute a blog post, the Internet is often the first source that students turn to pick up new information, to access useful networks, or to find resources that they need to accomplish whatever it is they want to learn. And why wouldn’t it be? The Internet is now a digital learning economy populated by YouTube and Vimeo channels, social media sites like Wikipedia, software and learning games, library data archives, learning television shows, documentaries, massive open online courses (MOOCs), and assorted other resources that are changing when, where, what, and how young people learn. Some educators, youth researchers, and parents lament this reality (Bakan, 2011 ; Louv, 2008 ), but today’s youth, media culture, and learning are nevertheless entangled in a rich set of relationships.

These relationships and the anxieties that they produce are not new. Since the earliest decades of the 20th century , learning dynamics have been thought to be integral to the way youth and media cultures weave together. But these relationships are vexed; the connections among youth lives, media, and education are sites of tremendous anxiety and concern around the world. Yet learning is now such a profoundly mediated experience that traditional dichotomies separating education and entertainment, work and leisure, expert and nonexpert, and pedagogy and everyday life are no longer helpful.

In this article, we examine this context and address how relations among youth, media culture, and learning have been understood since the turn of the last century. Our story begins in the Anglo-American world, but it has quickly become global as media and youth cultures expand around the world. We highlight the anxieties and panics common to thinking about media in young people’s lives and indicate where and how the mediation of youth learning has been taken up to support progressive ends through the development of novel resources, institutions, and pedagogies that nurture young people’s agency, identities, and citizenship. Our survey examines how specific media forms, including film, television, and Web design, have been calibrated to support young people’s learning through the media, and the development of media literacy education to promote critical learning about the media. To conclude, we detail three major problematics that continue to shape the relationships among youth, media culture, and learning.

Teen Screens

Teenagers graduating from high school in 2017 across the global North and much of the global South have always known smart mobile devices, social media, and YouTube, near-constant data surveillance, the ability to Google facts as needed, and texting, messaging, and posting as part of the regular rhythms of daily life. While many statistics have been collected over the years about the time that adolescents spend immersed in media, the general impression is that most children and youth are more involved than ever with media technologies and content. A new area of children’s and youth media has emerged in recent years. It is a world where the Internet, mobile devices, and “television,” now consumed across multiple platforms, compete for attention alongside older media (i.e., radio, appointment television, and movies). Various studies conducted in recent years have sought to understand these developments, with particular attention given to investigating the role of the Internet, social media, smartphones, and mobile technologies in young people’s lives. Regular television and radio continue to hold a place among teenagers’ media choices, and along with mobile phones, they are part of a primary youth media ecology in the global North and South (Common Sense Media, 2015 ; Livingstone et al., 2014 ).

Today, however, one can no longer assume that television programming is viewed on a television set via regularly scheduled broadcasting. While watching television continues to make up a significant portion of teens’ overall media usage in the United States, Canada, Europe, and other regions (Common Sense Media, 2015 ; Caron et al., 2012 ; Livingstone et al., 2014 ), smart TVs, on-demand services, mobile devices such as smartphones and tablets, and video-streaming services such as YouTube, Netflix, and Baidu have redefined what it means to “watch television.” Because the options for consuming content now exist simultaneously across many platforms, there is also a significant amount of diversity in young people’s preferences and patterns of use. Music, for example, remains the most preferred medium among teens, but among only about one-third of teens (30%). After music, video games are a favorite among 15%, reading among 10%, social media among 10%, and television among 9%. The fragmenting of tastes and preferences is notable, with no single medium standing out above all. Added to this is the diversity of ways that teens can engage in these activities, as well as differences in relation to class, gender, and race/ethnicity (Common Sense Media, 2015 ). The point to be made is that changes in how young people spend time with the media are taking place as part of longer-term trends in how media is knit into adolescents’ lives.

At the center of this trend is the fact that young people simply have more media options—both in terms of the media technology used and the content available—and these options are tightly wedded to the daily lives of children and youth. For instance, 57% of teens in the United States have a television set in their bedroom, 47% have a laptop computer, 37% have a tablet, and 31% have a portable game player (Common Sense Media, 2015 ). Sonia Livingstone ( 2009 , p. 21) identifies these technologies with “screen-rich ‘bedroom cultures,’” which have become the norm for kids in countries across the global North. Adding to and fostering media use in screen-rich bedroom cultures is the fact that two-thirds of teens (67%) now own their own smartphone, on which they talk and text, access social media (40%), and listen to music in daily patterns and rhythms (Common Sense Media, 2015 ).

With all these media options available, it is not surprising that teens are more likely than in the past to be media multitaskers, able to pack more media into an hour of consumption than was possible in previous generations. Young people in the United States spend approximately nine hours a day consuming media, for example, but they consume more than one medium at a time. In fact, 50% of teens say that they watch television while doing homework, and 51% say that they use social media some of or all the time when they do homework (Common Sense Media, 2015 ). The typical teenage user today is someone doing homework while watching Netflix, listening to music, and responding to the occasional text, Snapchat, or Instagram message. In this way, screens do not go away as much as they have become environmental in youths’ lives.

This story casts a pall over contemporary youth cultures for some. It is as though the media machine is never absent from youths’ time and space. It is attached to and formative of the worlds of young people, and it would appear to allow for no distance or time away from screens and representations in everyday life. Concerns of this sort are not new. They echo panicked worries about the consequences of young people’s media attachments that have existed for decades. To make sense of these worries, it is helpful to begin with the history of youth and youth culture, terms which are not exclusive to, but find an early emergence in, the West.

Youth as a Distinct Life Stage

The concept of youth can feel as though it has been with us for centuries. But while the age of transition between childhood and adulthood exists across societies, the idea that this period is associated with a particular group of people—youth—and the cultures that they partake in is a recent phenomenon. Andy Bennett (Bennett & Kahn-Harris, 2004 ) tells us that historical instances of what we now call “youth culture” can be traced back to the 17th and 18th centuries to a group of London apprentices whose dress, drinking, and riotous conduct set them apart from others. Early youth cultures can also be linked to stylistically distinct groups of young workers in northern England in the late 19th century , and to what Timothy Gilfoyle ( 2004 , p. 870) calls the “street rats and gutter snipes” of New York City, who developed oppositional subcultures to challenge adult authority from the mid- 19th century onward. But it wasn’t until the turn of the last century that a modern notion of youth took hold. Schooling would be key to this development.

Publicly funded or supported schooling on a mass scale was regularized in the United Kingdom by the late 19th century and had been ongoing in the United States in the post–Civil War period (i.e., after 1860–1865 ). Public schools developed around the same time in French and English Canada, and slightly later ( 1880 ) in Australia. The practice of batching students into groups by age contributed to the emergence of a new subject position linked to the teen years. If schools started this process, worries about delinquency served to consolidate the notion of youth as a stage of development. Juvenile crime in particular, initially considered primarily an affliction of poor and working-class youth, became generalized by the 1890s as juvenile delinquency and applied to all youth (Gillis, 1974 ). The fear of rising crime rates led to legislative action and the expansion of welfare provisions in the United Kingdom and the United States. The resulting system of social services addressed adolescents as a particular age cohort with specific interests and needs (Osgerby, 2004 ).

By the early 20th century , in psychology and pedagogy studies, G. Stanley Hall’s seminal text, Adolescence: Its Psychology and Its Relations to Physiology, Anthropology, Sociology, Sex, Crime, and Education (Hall, 1904 ) addressed this stage of life as a specific period of development associated with tumult and uncertainty—the sturm and drang of adolescence. Thinking of adolescence in these terms reflected the worries of legislators, educators, and reformers, but it was not until the early 1940s that the notion of youth culture was coined by the American sociologist Talcott Parsons ( 1942 ). Parsons used the phrase youth culture to name a specific generational cohort experiencing distinct processes of socialization that set them apart from others. Fears about young people’s maladjustment to war during the 1940s continued to feed worries about youth delinquency (Gilbert, 1986 ). But more significantly, a series of changes in the social, economic, and cultural lives of adolescents that began prior to World War II and consolidated during the postwar years proved essential to marking out a modern notion of youth culture.

Media and consumer markets were integral to these changes. From the start of the 20th century , mass media were among the key developments shaping youth culture and learning. This was evident in the United Kingdom and the United States, where industrialization and mass consumer markets emerged earlier than in other nations. This reveals something about the characteristics of youth culture; in many ways, youth cultures (dance, music, fashion, sports, etc.) have always been mediated and shaped by the effects of mass production, wage labor relations, and urban experience. In this way, youth and modernity are tightly connected. Modernity is linked to experiences of change driven by urbanization and migration, the expansion of mass, factory-based production, and the proliferation of images and consumerism as normative conditions of everyday life. Since the late 19th and early 20th centuries , youth have been harbingers of these developments and have often been considered the archetypical subject of modernity.

Early Mass Media and Youth Audiences

The tendency to link youth with the changes characterized by modernity has produced a history of anxieties where the relationships among youth, media culture, and education are concerned. These anxieties first appeared in response to the violence, vulgarity, and sexual desire in early popular culture (e.g., penny novels and mass sporting events, like Major League Baseball), which many educators thought posed an imminent threat to culture. The emergence of the cinema at the turn of the 20th century epitomized these fears by forever changing the nature of the intergenerational transmission of knowledge. Movies can be understood with little tuition, meaning that they can fix the attention of all age groups on the screen, a development that proved particularly attractive to children. Early cinematographers were able to stage dramas on a scale unheard of in live theater, to command an audience much greater than literature could, and hence to shape the popular imagination as never before. But because movies work through the language of images, they were thought to create highly emotional—and intellectually deceitful—effects. Images were thought to leave audiences (particularly young people) in something like a trance, a state of passivity that left adolescents open to forms of manipulation that were morally suspect and politically dangerous.

These fears were common, and yet for some, the very fact that movies could reach larger and more diverse audiences—including women and the working class—meant that the medium held a promise for learning that couldn’t be ignored. Such responses not only reflected the sentiment of early film boosters, but they also were part of a more nuanced sense of how life—including the experience of learning—was changing in the 20th century . In a remarkable series of essays, Walter Benjamin ( 1969 , 1970 ) argued thus, suggesting that movies could widen audiences’ horizons through the unique technology of the shot, the power of editing, and sound design. These tools allowed people to see and experience distant lands, other times, and new and fantastical experiences in live-action and highly structured narrative formats. Charlie Chaplin’s The Gold Rush ( 1925 ), MGM’s The Great Ziegfeld ( 1936 ), and Victor Fleming’s The Wizard of Oz ( 1939 ) exemplified film’s early appeal because they seemed capable of helping people to dream and escape vicariously from everyday experiences to imagine a different (and perhaps better) world.

Not surprisingly, Benjamin’s was a minority view in the mid- 20th century . Far more common were fears that modern media would serve to undermine how young people learn proper culture—meaning good books and the right music and stories thought to foster a vibrant and meaningful cultural life. Benjamin’s colleagues in the Frankfurt School (so-called for the city where their work began), Theodor Adorno and Max Horkheimer, were especially influential in this regard. Drawing from their experiences with the role that media (i.e., radio and film) played in the rise of fascism in Germany, as well as their disappointment with the quality of early popular music and Hollywood movies, Adorno and Horkheimer ( 1972 ) argued that the culture industries (the artifacts and experiences produced by the corporations who sold or transmitted film, popular music, magazines, and radio) threatened to undermine rich and autonomous forms of cultural life. They meant that movies, advertisements, and eventually television were signs of the commodification of culture, an indication that culture itself—epitomized by the rich European traditions of classical music, painting, and literature—was being reduced to a sellable thing, a commodity just like any other in capitalist societies.

In this context, Adorno and Horkheimer suggested that culture no longer works to promote critical and autonomous thought; rather, the culture industries promote sameness, a uniformity of experience and a standardization of life that at best serve to distract people from significant issues of the day. Through childish illusion and fantasy, the culture industries produce false consciousness, a form of thinking that misinterprets the real issues that matter in our lives, leaving young people and adults blissfully unaware of key issues of common concern that demand our attention and action. For those suspicious of these observations, they are worth considering in light of Donald Trump’s election as president of the United States in 2016 . Since the election, it has become clear that distraction (by “fake news,” for instance) and illusion (facilitated at least in part by foreign manipulation of social media) played a vital role in the campaign and Trump’s eventual election.

Youth Markets and Media Panics

The concerns of the Frankfurt School found a receptive audience in the second half of the 20th century . The postwar decades mark an especially significant period of expansion in youth markets and youth culture in the West (Osgerby, 2004 ). Increasing birth rates during the postwar baby boom fueled the expansion of youth markets, as did the extension of mass schooling, which “accentuated youth as a generational cohort” (Osgerby, 2004 , p. 16). Complicating this were the emergence of television and an intensely organized effort to shape and calibrate the spending power of young people in the service of conspicuous consumer consumption.

First introduced to the general public at the 1939 New York World’s Fair, in the postwar years, television became a new kind of hearth around which parents and children would gather. In the United States, television was initially thought potentially promising for children’s education. The small screen represented the promise and possibility of modern times. Not surprisingly, this sentiment was short lived (Goldfarb, 2002 ). By the late 1950s and 1960s, it became apparent that “most children’s programming was produced with the size of the audience rather than children’s education in mind. [As a result,] television [became] the source of anxious discourses about mesmerized children entranced by mindless cartoons, punctuated by messages from paying sponsors” (Kline, Stewart, & Murphy, 2006 , p. 132; also see Kline, 1993 ). These worries aligned with increasing concerns about the dangerous and morally compromising influence of rock ‘n’ roll, popular magazines, early celebrities, and movies in youths’ lives, and what resulted was a media panic that harkened back to the earliest days of mass media.

Most often characterized by exaggerated claims about the impact of popular commercial culture on children and youth, media panics are a special kind of moral frenzy over the influence of media on vulnerable populations (Drotner, 1999 ). Stanley Cohen’s groundbreaking study of the mods and rockers, Folk Devils and Moral Panics , suggests that emerging youth cultures became the most recurrent type of moral panic in Britain after World War II (Cohen, 1972 ). He reveals how youth are positioned in postwar industrial societies as a source of fear and often misplaced anxiety. His study has been criticized for simplifying the meaning of the term moral panics and for underestimating how complex media environments can shape them (McRobbie & Thornton, 1995 ); nonetheless, his work draws attention to the ways that overwrought fears of youth and media culture can come to act as stand-ins for larger social anxieties. In the process, youth and youth culture become scapegoats. Media panics don’t offer helpful tools for explaining social change, in other words, as much as they distract parents, educators, and others from making sense of the formative conditions shaping young lives.

Media panics continued to appear throughout the 1980s, 1990s, and 2000s. In the United Kingdom, for instance, media panics arose around “video nasties” and the risks that horror films and sexually explicit material were thought to pose for youth (Oswell, 2002 ). Related concerns arose in the 1990s regarding video games and violence, the presence of dangerous and disturbing messages buried in the lyrics of popular music, and fears about fantasy board games, including Dungeons and Dragons . More recently, anxieties have come to the fore having to do with the role of the Internet and social media in young people’s lives, including fears of “stranger danger,” cyberbullying, and the likelihood that teenagers are sharing explicit images of themselves and others online (i.e., “sexting”).

We note these fears not to dismiss them outright, but to draw attention to the history of anxieties that have characterized worries about youth and media culture. Such concerns are often underpinned by the view that young people are vulnerable and highly impressionable persons unable to manage the impact of media in their lives. Indeed, the wariness of public officials, parents, health practitioners, and educators toward media is still today often underpinned by deeper commitments to a sense that youth is a time of innocence and hope. Whether understood biologically as a period of maturation toward adulthood or as a distinct generational cohort characterized by shared processes of socialization, adolescence has long been a repository for both the greatest hopes and fears of a nation. While youth are often considered a risk to society and the reproduction of social order, they also have long been framed in connection with the future health and well-being of nations. The result is that youth often occupy a contradictory space in relation to media culture (Drotner, 1999 ).

On the one hand, popular media culture has been a vital resource through which youth communities, subcultures, and generations have defined themselves, their desires, and their hopes and dreams for decades. This continues to be reflected in the dynamic ways that youth are using and creating digital media to shape their lives and address matters of common concern in societies around the world. We take up these developments in more detail later in this article.

On the other hand, it is evident that consumerism and commercial media culture remain sources of tremendous anxiety. The media content that teenagers access—beyond the watchful eye of guardians and educators—and the way that they learn about gender, race, sexuality, the environment, and other issues continues to raise alarms. From at least the 1980s onward, the quantity of media culture has expanded around the world, meaning that more advertising, more commercial screens, more branded experiences of play, and more intensive systems of corporate surveillance and tracking have become common features of youths’ lives.

The digitization of media and the emergence of more dynamic, participatory media cultures (Jenkins, 2006 ) are crucial to this development, as we explain in the final section. But changes in media concentration and the development of vast media conglomerates—including Google, Disney, Time Warner, Viacom, Baidu, and News Corp—that produce media commodities and experiences for various national markets have been instrumental in shaping the tensions and impact of media culture on youth lives. It is just these sorts of developments that have long raised the concerns of educators and others who remain deeply ambivalent about the relationship between consumer media and young people. The consequence of this ambivalence has led some educators to argue that media, including film, television, and the Internet, can have a broader educational impact, particularly given their ability to reach large audiences. In the following sections, we take up this possibility and address how learning media and media education have been developed to create forms of public pedagogy with the potential to enrich young people’s learning.

The Media as Learning Portal

While the ties between consumer culture and media continue to raise worries, television’s reach and increasingly central role in families have drawn the attention of educators who argue that it can be repurposed to have a broader educational impact. This sentiment crept into educational discourses throughout the 1960s in a way that would shift the thinking about youth, media culture, and education. Educational media programming was not a new idea in the decade so much as it extended and contributed to an older tradition of using stories and folk tales to teach moral lessons to children (Singhal & Rogers, 1999 ). What was different in the 1960s (and today), however, is that this work wasn’t (and isn’t) being undertaken around the local hearth; it was (and is) developing through the conventions, institutions, and practices of a highly complex media system.

Using this media system to create successful learning resources has been a delicate business. The idea of using radio and documentary movies as informational (and often didactic) educational tools to teach kids social studies, geography, and history has a long tradition in national schooling systems. More dynamic forms of educational programming came online in the late 1960s, led by a then-remarkable new program called Sesame Street that came to epitomize these developments.

Created by the Children’s Television Workshop (CTW) in 1969 as part of the so-called American war on poverty (Spring, 2009 ), Sesame Street helped launch the Public Broadcasting System (PBS) in the United States as a counterweight to the influence of commercial programming in the American mediasphere. Originated by Joan Ganz Cooney and Lloyd Morrisett, Sesame Street drew lessons from early children’s television programming in countries like Canada and the United Kingdom (Coulter, 2016 ) and set out to promote peaceful multicultural societies and to provide inner-city kids with a head start in developing literacy and numeracy skills. To do this, the now well-known strategy was to adapt conventions of commercial media—muppets, music, animation, live-action film, special effects, and visits from celebrities—to deliver mass literacy to home audiences.

By the late 1990s, approximately 40% of all American children aged 2–5 watched Sesame Street weekly. From the 2000s onward, the reach of Sesame Street became global, extending to 120 countries and including many foreign-language adaptations developed with local educators in Bangladesh, China, Egypt, Germany, Israel, Palestine, Russia, South Africa, and many other places (Spring, 2009 ). With global audiences, the show’s storylines and issues addressed have also changed. Sesame Street is now engaged in raising awareness and understanding about a host of global issues. For instance, in the South African coproduction, a muppet named Kami who is HIV-positive was introduced in response to the large numbers of South African children who are HIV-positive. Through Kami and related stories, the goal of the program is “to create tolerance of HIV-positive children and disseminate information about the disease” across South Africa” (Spring, 2009 , p. 80). Meanwhile in Bangladesh, the local version of Sesame Street has been used to promote “equality between social classes, genders, castes, and religions” (Spring, 2009 , p. 80).

This success led to the development of other CTW educational programs, including The Electric Company , 3-2-1 Contact , and Square One TV . A conviction that electronic and digital media can support progressive educational goals has also fueled the development of a learning media industry over the past two decades. We are in fact witnessing a veritable explosion of educational media, including an array of educational learning software ( Math Blaster , JumpStart , Where in the World Is Carmen Sandiego , etc.) designed to improve older students’ competencies (Ito, 2008 ). Some of this media may be useful, but evidence about the learning value of many of these programs remains scant (Barbaro, 2008 ). On the other hand, at least three other forms of educational media have continued to develop, and in ways that can be beneficial to youth learning. They include public service announcements (PSAs), entertainment education, and cultural jamming.

Public Service Announcements

Public service announcements (PSAs) are now ubiquitous. They can be seen in schools, on television, online, and at commercial film screenings. They address issues ranging from the dangers of smoking, alcohol, and drugs, to concerns about youth driving habits, bullying in schools, what children are eating, and a host of other media-related social causes and health crises. At root, the strategy with PSAs isn’t altogether different from that of learning-oriented programs like Sesame Street . While the broad research and learning agenda that informs Sesame Street isn’t often replicated with PSAs, the idea that commercial media language can be repurposed to influence behavior is common to both formats.

PSAs use the language of advertising—quick, emotional, and sometimes funny messages that emphasize hard-hitting lessons—and the practices of branding to alter behavior or encourage youth to get involved with issues shaping their lives. Studies suggest these strategies can be remarkably effective for influencing young people’s behavior (Montgomery, 2007 , 2008 ; Wakefield, Flay, Nichter, & Giovino, 2003 ; Singhal & Rogers, 1999 ; DeJong & Winston, 1990 ). Wakefield et al. ( 2003 ) for instance, review a number of studies that show antismoking PSAs are useful tools for changing kids’ attitudes, especially when combined with school support programs that help youth to quit or avoid smoking.

These successes are important, of course, because they attest to the ways that learning through media can be nurtured in creative, dynamic, and effective ways, even in a time when media saturation is common in youth lives. A cautionary note is nonetheless in order. PSAs have become so common today that companies are using PSA-like formats to promote everything from cars to personal care products. The personal health products company, Unilever Inc., for instance, has been especially successful with their Dove “Campaign for Real Beauty.” Cutting across online platforms as well as television and film, the campaign has foregrounded the way that beauty ads create unrealistic notions about women’s body images. This is an important message, to be sure; however, while this campaign was underway, Unilever launched an equally provocative campaign for AXE body products for men. What stood out in the latter campaign was precisely the opposite message about women’s body images; AXE ads in fact seemed to suggest that women matter only when their appearance corresponds to a rather tired and old set of stereotypes. This doesn’t necessarily undermine the value of the Dove Campaign for Real Beauty, but it does suggest that the value of PSAs (particularly when developed as singular learning resources) may be waning as this style of communication becomes just one more strategy for channeling commercial messages to youth.

Entertainment Education

Another strategy, often called entertainment education , has a similarly long history in both the global North and South (Singhal & Rogers, 1999 ; Tufte, 2004 ). Distinct from the more explicit focus of learning TV and PSA campaigns, this strategy takes advantage of the fact that it has been clear for some time that youth negotiate their identities and values through popular media representations and celebrity identifications. Because of this, educators and youth activists have turned to network programming (e.g., Dawson’s Creek , MTV’s Real People , and Glee ), as well as teen magazines (e.g., Teen People and Seventeen ) as vehicles for developing storylines and articles that address issues in youth’s lives. Similar practices are evident around the world. In India, Mexico, Brazil, and South Africa, for instance, popular television formats like soap operas and youth dramas (e.g., Soul City and Soul Brothers in South Africa) have been used to raise awareness and change unhealthy behaviors related to a host of issues, including child poverty, community health, HIV-AIDS, and gun violence.

In a related vein, the Kaiser Foundation in the United States has been influential in the development of a multinational set of entertainment education programs on HIV-AIDS in partnership with the United Nations. Since 2004 , the Kaiser Foundation has partnered with the United Nations, the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC), the South African Broadcasting Corporation, Russia’s Gazprom-Media, Rupert Murdoch’s Star Group Ltd. in India, and more than 10 other media companies to develop a Global AIDS initiative. This eventually led to the integration of HIV-AIDS messages into various programs watched by young people, including a reality series in India modeled on American Idol , called Indian Idol (Montgomery, 2007 ). Similarly, series like the Degrassi franchise in Canada and the United States have addressed issues such as family violence, school shootings, mental illness, and questions about sexuality (Byers, 2008 ). Other series, including Buffy the Vampire Slayer , have ventured into similar territory, and while many educators are perhaps wary of the close working partnership between commercial broadcasters and producers in entertainment education, others note that the very success of this kind of programming demonstrates that media culture can be more than entertainment; it can be a form of meaningful pedagogy that helps young people engage in real social, cultural, and political debate.

Culture Jamming

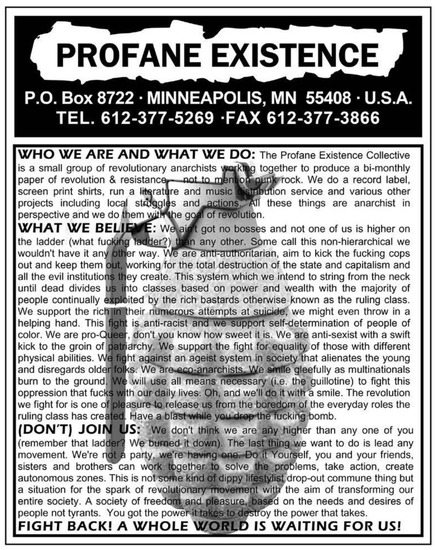

Fomenting social, cultural, and political debate has been the objective of a third strategy used by educators and progressives concerned about youth, media culture, and education. Culture jamming draws on a long tradition of using media techniques with satire and parody “to draw attention to what may otherwise go unnoticed” in society (Meikle, 2007 , p. 168). Antecedents to culture jamming include the anti-Nazi dada posters of John Heartfield (born Helmut Herzfeld) and the détournment tactics of the Situationist Movement of the mid-1950s and 1960s, which sought to dismantle the world of commercial media culture that transforms “[e]verything that [is] directly lived . . . into a representation” (Debord, 1994 , p. 1).

Culture jammers frequently argue that our lives are dominated by a vast electronic and digital field of multimodal texts (images, audio, and now hypertext and hyperlinks), and the only way to respond is to use the design methods (pastiche, bricolage, parody, and montage) and genres (advertising, journalism, and filmmaking) that characterize commercial media to challenge media power and taken-for-granted assumptions within contemporary culture (Kenway & Bullen, 2008 ). Mark Dery ( 1993 , p. 1) calls this a form of “semiological guerrilla warfare,” through which culture jammers fight the status quo by using the principles of media culture to upend the meanings and assumptions operating in this culture.

Perhaps the most common and popular form of culture jamming is the sub-vertisement that groups like Adbusters have made popular. Sub-vertisements use popular references and techniques in branding campaigns to turn the meaning of logos, branded characters, and signs (like the Absolut Vodka bottle) on their heads. (See http://adbusters.org/spoofads/index.php for a gallery of examples that target fast food culture, alcohol and fashion ads, and political communication.) Other groups, including the Yes Men , have developed another culture-jamming strategy based around highly elaborate spoofs of websites, media interviews, and public corporate communications. Reverend Billy and his Church of Stop Shopping is yet another example of culture jamming. Reverend Billy and his allies use impromptu, guerrilla theater tactics to raise awareness of the deleterious effects of consumerism (i.e., sweat shop labor, debt, climate degradation, etc.) in society. The idea behind this and similar work is to use fun yet subversive tactics to offer radical commentary about common images, brands, and ideas that circulate in our lives. These learning practices are open to all, of course, but they have been especially relevant among educators eager to address critical issues about youth media culture.

Media Education and Direct Interventions in Youth Learning

Learning media aims to educate people through various media forms, and while this continues to be a popular strategy, for more than 80 years educators and activists have also turned to more direct interventions to affect how young people learn and engage with media culture. Media literacy education addresses how media operates in and through particular institutions, technologies, texts, and audiences. In its early development, media education tended to position schools and teachers as the defenders of traditional culture and impressionable youths. Early relationships among youths, media cultures, and education were framed around a reactionary stance that implored educators to protect youth from the media. F. R. Leavis and Denys Thompson ( 1933 ) were the first to champion this protectionist phase of media education in their book Culture and Environment , which is credited as the first set of proposals for systematic teaching about mass media in schools. Leavis and Thompson’s work includes a strong prejudice against American popular culture and mass media in general and reflects the aspirations for early media education within schools to inoculate young people against media messages to protect literary (i.e., high) culture from the commoditization lamented by mass culture theorists (Hoechsmann & Poyntz, 2012 ).

These sentiments remained strong into the early 1960s, but much as learning media took a new and compelling turn in this decade, so too did media education. Fueling this trend was the belief that educators could adapt curricula and teaching practices to the increasing role of commercial television and movies in young people’s lives. In the United Kingdom, this sentiment led educators to develop a screen education movement based around the critical use of movies in classrooms. Drawing from the influential work of Richard Hoggart’s Uses of Literacy ( 1957 ) and Raymond Williams’s Culture and Society ( 1958 ), the purpose of screen education was to study the popular media that teenagers were watching so that they would be in a better position to understand their own situation in the world, including the causes of their alienation and marginalization.

A similar desire to help youth see connections between school and everyday life motivated early initiatives in media education in Australia and Canada. Pedagogically, this led to the development of film analysis and film production courses, which drew inspiration from cultural shifts in the way that movies were understood. No longer seen simply as forms of entertainment, film education focused on the way that popular Hollywood movies (e.g., Easy Rider and Medium Cool in 1969 ) reflected social and cultural values and were thus thought deserving of critical attention. This meant teaching students to understand the language of cinema and the ways that movies engage and shape prospects for social and political change.

As an outgrowth of this work, the 1980s and 1990s witnessed the first sustained period of institutionalization of media education. Key curricular documents were produced, and media education entered the school curricula in many countries in a formal way for the first time. The Canadian province of Ontario led the way, mandating the teaching of media literacy in the high school English curriculum in 1987 . Eventually K–12 students across Canada would receive some form of media education by the end of the 1990s. Meanwhile in the United Kingdom, the late 1980s witnessed the integration of media education into the curriculum as an examinable subject for students pursuing university entrance. This helped to fuel the popularity of courses in media studies, film studies, and communication studies in schools, and by the 1990s and 2000s, additional intermediate courses in media studies were added to the curriculum.

In Australia, the late 1980s and 1990s marked a period of expansion in school-based production and media education training, in part because such training was seen to be an ideal way to equip young people with the technical skills and competencies needed to compete in a globally competitive, highly mediated world (Edith, 2003 ; McMahon & Edith, 1999 ). Similarly, in various non-English-speaking countries, including Norway, Sweden, and Finland, media literacy developed and expanded throughout the 1990s (Tufte, 1999 ).

Even when not included in the formal curriculum, media education became a pedagogical practice of teachers aware of the impact of the media in the lives of their students. In particular, in those countries in the global South where the broader educational needs of the society were still focused on getting children to school and teaching basic literacy and numeracy, media education may not have emerged in the mandated curriculum, but teachers were drawing on media education strategies to help youth make sense of and affect their worlds.

In the United States, school-based media education initiatives were slower to get off the ground. In 1978 , in response to children’s increasing television consumption, the Parents-Teachers Association (PTA) convinced the U.S. Office of Education to launch a research and development initiative on the effects of commercial television on young people. In short order, this initiative led the Office of Education to recommend a national curriculum to enhance students’ understanding of commercials, their ability to distinguish fact from fiction, the recognition of competing points of view in programs, an understanding of the style and formats in public affairs programming, and the ability to understand the relationship between television and printed materials (Kline et al., 2006 ).

Ultimately, attempts to implement this curriculum were hampered in the early 1980s as President Ronald Reagan’s move to deregulate the communications industry challenged efforts to develop media education in U.S. schools. Nonetheless, these early developments proved crucial in establishing the ground from which more recent media education initiatives have grown. Robert Kubey ( 2003 ) noted that as of 2000 , all 50 states included some education about the media in core curricular areas such as English, social studies, history, civics, health, and consumer education.

Beyond schools, a number of key nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) have developed over the past two decades and have promoted dynamic forms of media education. The Alliance for a Media Literate America (AMLA), a national membership organization chartered in 2001 to organize and host the National Media Education Conference every two years and to promote professional development, is of particular note. So too are the Media Education Foundation (MEF), which produces some of the most important media education resources in North America, and the Centre for Media Literacy (CML), which offers a helpful MediaLit Kit to promote teaching and learning in a media age.

Literacy and Production

While often led by educators, parents, and young people, these developments in media education have been enhanced by interest in a broad project of literacy. The role and discussion of literacy discourse in media education go back to at least the early 1970s in the United States (Kline et al., 2006 ). As media education has internationalized, however, there has been a tendency to turn to literacy metaphors to conceptualize the kinds of media learning enabled through media education. As media education has increasingly become part of school curricula, the language of literacies also has been a familiar and useful framework to situate classroom (and out-of-school) practices. The New London Group’s ( 1996 ) “pedagaogy of multiple literacies” has been especially influential, offering a framework to address the diverse modalities of literacy (thus, multiple literacies) in complex media cultures, alongside a focus on the design and development of critical media education curricula.

While the New London Group’s work has helped to support the development of media literacy education in an era of multimodal texts, the arrival of the personal computer and the emergence of the Internet have been accompanied by the proliferation of a whole host of digital media technologies (e.g., cameras, visual and audio editing systems, distribution platforms, etc.), encouraging the integration of youth media production into the work of media education. Media production has an impressive history in the field of media literacy education going back to at least the 1960s, when experiments with 16-mm film production in community groups and schools were part of early film education initiatives in the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, and other countries. By the 1990s and 2000s, media production became a common feature in media education practices because it was thought to enable young people to learn by doing , rather than just by analyzing or reading media texts. Newly accessible broadcasting (or narrowcasting) opportunities made available through Web 2.0 platforms (e.g., YouTube, Facebook, wiki spaces, etc.) accelerated these developments, encouraging the growth of information training programs in schools that focus on Web design, software training, and mastering camera skills in ways that emphasize technological mastery as an end in itself.

The turn to information training is perhaps not surprising, but while technical skills training can help young people to learn key competencies that may lead to job prospects, technical training on its own misrepresents the critical and civic concerns that have long animated media literacy education. How the civic and political involvement of youth are emerging inside highly engaging digital media cultures is one of three major issues examined in the next and final section of this article, where we address pressing questions about contemporary relationships among youth, media culture, and learning.

Contemporary Issues in Youth Media Culture and Education

Recent questions about youth and media culture are tangled up with the participatory condition common to network societies (Sterne, Coleman, Ross, Barney, & Tembeck, 2016 ; Castells, 1996 ). The age of mass media was preoccupied with problems of representation, atomization, homogenization, and manipulation, and these problems defined the thinking about youth consumption and commercial culture in much of the 20th century . This is reflected in the anxieties and studies noted earlier in this article. As we have come to read and write media differently in a digital era, however, a new set of problems has arisen (Chun, 2016 ). Among these is the new role of participation and a participatory turn in media culture that has enabled users (or those we used to call audiences ) to become more active and involved with brands, franchises, celebrities, technologies, and social media networks across everyday life (Jenkins, 2006 ). This turn is evidenced by the increasing amount of time that youth spend with screens, but it is also a function of the way that many of us now interact with media culture. Audiences have always been actively involved with still and moving images, celebrities, sports, and popular music, among other artifacts. Fan cultures exemplify this, as do studies of how real-life audiences talk about and use media (Buckingham, 1993 ; Williams, 2003 ; Silverstone, 2001 ; Scannell, 1989 ; Radway, 1984 ).

But today we are called on to participate in digital media culture in new ways. Participation has become a condition that is “both environmental (a state of affairs) and normative (a binding principle of right action)” (p. vii), and our digital technologies and highly concentrated media industries are woven into the fabric of this state of affairs (Sterne et al., 2016 , p. vii). “These media allow a growing number of people to access, modify, store, circulate, and share media content” in ways that have been available only to professionals or a select few in the past (Sterne et al., 2016 , p. viii). As digitalization has changed the nature of media production, we have not only become more involved and active in our media use, but our interaction with digital media has allowed others to interact with us in new and sometimes troubling ways. This is the paradox of the participatory condition, and it shapes how youth media culture and education are connected today.

Issue 1: Surveillance, Branding, and the Production of Youth

To begin with, the pointy end of the participatory paradox has to do with the way that digital media cultures allow others, including corporations, governments, and predatory individuals, to monitor, survey, coordinate, and guide our activities as never before. With our data footprint, states, political parties, media, toy, and technology companies (as well as health, insurance, and a host of other industries) become data aggregation units that map and monitor youth behavior to interact with, brand, and modify this behavior for profitable ends. Big data enables the production of complex algorithms that produce what Wendy Chun ( 2016 , p. 363) calls “a universe of dramas” that dominate our attention economies. These dramas (the stories, celebrities, associations, and products with which we interact) are “co-produced transnationally by corporations and states through intertwining databases of action and unique identifiers.” Databases and identifiers enable algorithms to target, engage, and integrate a diverse range of youth into the global imaginary of consumer celebrity cultures and the archives of surveillance states (Chun, 2016 ). The American former military contractor and dissident Edward Snowden draws our attention to this universe in the documentary CitizenFour , which tells his story, and makes clear that instead of governments and corporations being accountable to us, we are now, regularly and without knowing it, accountable to them (Snowden, 2016 ).

Compounding these concerns, strangers can now access youth in ways that magnify the potential damage done by the pointy end of the participatory paradox. Fears about stranger danger and cyberbullying have been especially acute in recent years, and while these fears are not new (Poyntz, 2013a ), they have been central to panicked reactions among parents, educators, and others wary of youth media culture. These fears are often connected to worries about online content that young people now access, including vast troves of pornography available at the click of a button, as well as worrying online sites that promote hate, terrorism, and the radicalization of youth. The actual merits of concerns about who is accessing youth and what content they are accessing are sometimes difficult to gauge; nonetheless, it remains the case that for the foreseeable future, one of the fundamental issues shaping relationships between youth, media culture, and education is how and through what means youth are produced and made ready to participate in contemporary promotional and surveillance cultures—particularly when this happens for the benefit of people and institutions that exercise immense and often dubious power in young lives.

Issue 2—Creative Media and Youth Producing Politics

On the other end of the participatory paradox is a second issue shaping youth, media culture, and learning. While network societies produce new risk conditions (like those noted previously) for teenagers, digital media undoubtedly have enabled new forms of creative participation and media production that are changing how youth agency and activism operate. Mobile phones, cameras, editing platforms, and distribution networks have become more easily accessible for young people across the global North and South in recent years, and as this has happened, youth have gained opportunities to create, circulate, collaborate, and connect with others to address civic issues and matters of broad personal and public concern in ways that simply have not been available in the past. Since the mid-1990s, online media worlds have emerged as counterenvironments that afford teenagers a rich and inviting sphere of digitally mediated experiences to explore their imaginations, hopes, and desires (Giroux, 2011 ).

The fact that young people’s online worlds are dominated by the plots and affective commodities of commercial corporations means that these worlds can foster a culture of choice and personalized goods that encourage youth to act in highly individualized ways (Livingstone, 2009 ). But the skills and networks that teens nurture online can be publicly relevant (Boyd, 2014 ; Ito et al., 2015 ). The Internet, social media, and other digital resources have in fact become central to new kinds of participatory politics and shared civic spaces that are emerging as an outgrowth and extension of young people’s cultural experiences and activities (Ito et al., 2015 ; Soep, 2014 ; Kahne, Middaugh, & Allen, 2014 ; Poyntz, 2017 ; Bennett & Segerberg, 2012 ; Bakardjieva, 2010 ).

These practices extend a history of youth actions wherein culture and cultural texts have been drawn on to contest politics and power (including issues of gender, class, race, sexuality, and ability) and matters of public concern (including climate change and the rights of indigenous communities). Youth who lack representation and recognition in formal political institutions and practices often turn to culture and cultural texts to contest politics and power (Williams, 1958 ; Dimitriadis, 2009 ; Maira & Soep, 2005 ; McRobbie, 1993 ; Hebdige, 1979 ; Hall & Jefferson, 1976 ). Recently, these tendencies have been evident in the actions of the Black Lives Matter movement , which has produced an array of cultural expressions, including a video story archive and a remarkable photo library that lays bare the experiences and hopes of a movement that aims to be “an ideological and political intervention in a world where Black lives are systematically and intentionally targeted for demise.”

Beyond North America, in Tunisia, Egypt, Israel, Chile, Spain, the United Kingdom, Turkey, and other places, a range of bottom-up communication for social change practices has been part of epochal political actions and assemblies often led by students and other young people demanding government action on social justice and economic and human rights (Dencik & Leistert, 2015 ; Tufte et al., 2013 ). The contexts for these actions are complex, but in general, they point to instances where political cultures are emerging from young people’s cultural experiences and learning, challenging the meaning, representation, and response of those in power to matters of public concern.

More generally, across a range of youth communities, peer networks, and affinity associations, participatory media cultures are enabling levels of engagement, circulation, and cultural production by young people that are altering relationships between youth creative acts and political life. Kahne et al., 2014 have described these emerging practices as part of a wave of participatory politics that include a cross-section of actions that often extend across global communities. Examples include consumer activism (e.g., product boycotting) and lifestyle politics (e.g., vegetarianism); groups like the Harry Potter Alliance (HPA), which use characters and social justice themes from the novels to encourage connections between cultural and civic life; a community gathered around the Nerdfighters , a YouTube channel and movement organized around John and Hank Green and their mission to “decrease world suck”; fascinating examples of participatory storytelling, including the use of video memes by and about undocumented immigrant youth to draw attention to lives that have largely disappeared from mainstream media culture; and youth-driven campaigns and petitions organized in conjunction with groups like Change.org and Openmedia.ca to challenge public policy and focus attention on major injustices by institutions and officials using memes, videos, and mobile phone recordings of violence, inequity, and exploitation (Ito et al., 2015 ).

In addition to politically mobilized youth and youth drawn into mediated politics through cultural pastimes, there is evidence that youth connections to politics are being nurtured further by a diverse range of community youth media initiatives and groups that have emerged in cities across the global North and South over the past 20 years (Poyntz, 2013b , 2017 ; Asthana, 2015 ; Tufte et al., 2013 ; Tyner, 2009 ). Such community groups are part of a response to the risk conditions that shape contemporary life. They are crucial to negotiating citizenship in highly mediated cultures and for addressing digital divides to equip young people with the resources and networks necessary to manage and respond to experiences of change, injustice, violence, and possibility.

Community youth media production groups are part of an informal cultural learning sector that is an increasingly significant part of the work of provision for socially excluded youth. These groups are of many types, but they are symptomatic of a participatory media culture in which new possibilities and new opportunities have arisen to nurture youth creativity and political action. How to foster these developments through media education and the challenges confronting these efforts represents the third major issue shaping connections between youth, media culture, and learning today.

Issue 3—Youth, Media Learning, and Media Education

Media literacy education refers to learning “a set of competencies that enable one to interpret media texts and institutions, to make media of [one’s] own, and to recognize and engage with the social and political influence of media in everyday life” (Hoechsmann & Poyntz, 2012 , p. 1). We might debate this definition, but the larger point is that since at least the mid-1990s, media literacy education has made many gains in school curricula and among community groups and social movements, as noted previously (Skinner, Hackett, & Poyntz, 2015 ). At the same time, the challenges facing media literacy education are significant. For instance, the massive and relentless turn to instrumental forms of technical and creative learning in the service of job markets and competitive global positioning in formal schooling has mitigated the impact of critical media education.

Over the past two decades, a broad set of changes in schooling environments around the world have increasingly put a premium on preparing teenagers to be globally competitive, employable subjects (McDougal, 2014 ). In this context, the lure of media training in the service of work initiatives and labor market preparation is strong; thus, there has been a tendency in school and community-based media projects and organizations to focus on questions of culture and industry know-how (i.e., knowing and making media for the culture industries), as opposed to the work of public engagement and media reform. This orientation has been further encouraged by a return to basics and standardized testing across educational policy and practice, which has encouraged a move away from citizen-learning curricula (Westheimer, 2011 ; Westheimer & Kahne, 2004 ). These developments have led to efforts to redefine media education in the English curriculum in the United Kingdom, in ways that discourage critical media analysis and production (Buckingham, 2014 ).

In like fashion, the pressure to return to more traditional forms of learning has led to education policies in the United States, Australia, and parts of Canada that are intended to dissuade critical and/or citizen-oriented learning practices in schools (Poyntz, 2015 ; Hoechsmann & DeWaard, 2015 ). Poyntz ( 2013 ) has indicated elsewhere how this orientation shapes the projects of some community media groups working with young people, but the upshot is that instrumental media learning has come to complicate and sometimes frustrate how media literacy education is used to intervene in relationships among youth, media culture, and learning (Livingstone, 2009 ; Sefton-Screen, 2006 ).

This situation has been complicated further as the field of media literacy education has evolved to become a global discourse composed of a range of sometimes contradictory practices, modalities, objectives, and traditions (McDougall, 2014 ). The globalization of media literacy education has been a welcome development and is no doubt a consequence of the globalization of communication systems and the intensification of consumerism among young people around the world. But if the result of this development has been an outpouring of policy discussions, policy papers, and pilot studies across Europe, North America, Asia, and other regions (Frau-Meigs & Torrent, 2009 ), this has at the same time also produced a complex field of media literacy practices and models that have led to a generalization (and even one suspects a depoliticization) of the field. This has happened as efforts have emerged to weave media literacy education into disparate education systems and media institutions (Poyntz, 2015 ).

As the proliferation of media literacies has been underway, a raft of new media forms and practices—including cross-media, transmedia, and spreadable media (Jenkins, Ford, & Green, 2013 ) have also encouraged the production of a myriad of discourses about “ digital literacy, new media literacy [and] transmedia literacy” (McDougall, 2014 , p. 6). These and similar developments have ensured that media literacy education remains a contested field of objectives and meanings. While this can be interesting for academics, it may be less than encouraging for young people, educators, and others eager to draw on media education to affect contemporary relationships between youth, media culture, and learning. And let it be noted that the impact of these developments is not only relevant to the ways that youth negotiate media culture, but also to the future of democracy itself.

Concluding Thoughts

Media cultures have come to play a significant role in the way that young people go about making meaning in the world; this is especially true of how knowledge is shared and acquired. As a result, media are part of the continual shaping and reshaping of what learning resources look like. Both inside and outside the classroom, young people are increasingly able, even expected, to utilize the vast number of resources now available to them. Yet, many of these resources now foster worry rather than learning. The fact that “Google it,” for instance is now a common phrase referring to the act of information seeking is in itself telling; a distinct culture of learning has emerged from the development of the Internet and other media technologies. In fact, many young people today have never experienced learning without the ability to “Google it.” Yet this very culture of learning is indistinguishable from an American multinational technology company that is not beholden to the idea of a “public good.” If the project of education is not just to be for the benefit of a select few, but for society and a healthy democracy as a whole, however, then these contradictions must be engaged. So while media cultures are a significant feature of young people’s lives, it is becoming clear that media cultures have augured complicated relationships between youth and education in ways that are not easily reconciled.

The project of media education is not without its own set of challenges and contradictions, including those highlighted in this article. But it remains indispensable if educators, parents, and researchers are to support young people in navigating learning environments and imagining democratic futures.

Acknowledgments

Parts of this article have been adapted from Hoechsmann et al. ( 2012 ).

Further Reading

- Bond, E. (2014). Childhood, mobile technologies, and everyday experiences . Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Bragg, S. , & Kehily, M. J. (Eds.). (2013). C hildren and young people’s cultural worlds . 2d ed. Bristol, CT: Policy Press.

- Buckingham, D. (1993). Children talking television: The making of television literacy . London and New York: RoutledgeFalmer.

- Buckingham, D. (2007). Beyond technology: Children’s learning in the age of digital culture . Cambridge and Malden, MA: Polity.

- Critter, C. (Ed.). (2006). Critical readings: Moral panics and the media . Maidenhead, U.K.: Open University Press.

- Cross, G. (2004). The cute and the cool: Wondrous innocence and modern American children’s culture . Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press.

- Dolby, N. , & Rizvi, F. (Eds.). (2008). Youth moves: Identities and education in global perspective . London: Routledge.

- Fraser, P. , & Wardle, J. (Eds.). (2013). Current perspectives in media education: Beyond a manifesto for media education . London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Ito, M. (2009). Engineering play: A cultural history of children’s software . Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Jenkins, H. (Ed.). (1999). The children’s culture reader . New York: New York University Press.

- Jenkins, H. (2006). Convergence culture: Where old and new media collide . New York: New York University Press.

- Jenks, C. (2005). Childhood . 2d ed. London and New York: Routledge.

- Livingstone, S. (2009). Children and the Internet . Cambridge, MA: Polity.

- Adorno, T. , & Horkheimer, M. (1972). Dialectic of enlightenment . J. Cumming (Trans.). New York: Herder and Herder.

- Asthana, S. (2015). Translocality, imagination, and the political: A hermeneutic exploration of youth media initiatives from India and Palestine. In S. R. Poyntz & J. Kennelly (Eds.), Phenomenology of youth cultures and globalization (pp. 23–52). New York: Routledge.

- Bakan, J. (2011). Childhood under siege: How big business targets children . Toronto: Allen Lane Canada.

- Bakardjieva, M. (2010). The Internet and subactivism: Cultivating young citizenship in everyday life. In P. Dahlgren & T. Olsson (Eds.), Young people, ICTS, and democracy: Theories, policies, identities, and websites (pp. 129–146). Gothenburg, Sweden: Nordicom.

- Barbaro, A. (Director). (2008). Consuming kids: The commercialization of childhood . Northampton, MA: Media Education Foundation.

- Benjamin, W. (1969). The work of art in the age of mechanical reproduction ( H. Zohn , Trans). In H. Arendt (Ed.), Illuminations: Essays and reflections (pp. 217–251). New York: Schocken Books.

- Benjamin, W. Author as producer. (1970). NLR, 62, 83–97.

- Bennett, A & Kahn-Harris, K. (Eds.). (2004). After subculture: Critical studies in contemporary youth culture . New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Bennett, W. L. , & Segerberg, A. (2012). The logic of connective action: Digital media and the personalization of contentious politics. Information, Communication, & Society , 15 (5), 39–768.

- Boyd, D. (2014). It’s complicated: The social lives of networked teens . New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- Buckingham, D. (Ed.). (1993). Reading audiences: Young people and the media . Manchester, U.K.: Manchester University Press.

- Buckingham, D. (2014). The success and failure of media education. Media Education Research Journal , 4 (2), 5–18.

- Byers, M. (2008). Education and entertainment: The many reals of Degrassi. In Z. Druick & A. Kotsopoulos (Eds.), Programming reality: Perspectives on English-Canadian television (pp. 187–204). Waterloo, Ontario, Canada: Wilfred Laurier University Press.

- Caron, A. H. , Hwang, J. M. , McPhedran, E. , Mathys, C. , Chabot, P.-L. , Marrder, N. , . . ., Caronia, L. (2012). Are the kids all right? Canadian families and television in the digital age . Montreal: Youth Media Alliance.

- Castells, M. (1996). The rise of the network society . Cambridge, MA: Blackwell Publishers.

- Chun, W. (2016). Big data as drama. EHL , 83 (2), 363–382.

- Cohen, S. (1972). Folk devils and moral panics: The creation of the mods and rockers . London: MacGibbon & Kee.

- Common Sense Media . (2015). The common sense census: Media use by tweens and teens . San Francisco: Common Sense Media.

- Coulter, N. (2016). Missed opportunity: The oversight of Canadian children’s media. Canadian Journal of Communication , 41 (1), 95–113.

- Debord, G. (1994). The society of the spectacle . New York: Zone Books.

- DeJong, W. , & Winsten, J. A. (1990). The use of mass media in substance abuse prevention. Health Affairs , 9 (2), 30–46.

- Dencik, L. , & Leistert, O. (Eds). (2015). Critical perspectives on social media and protest: Between control and emancipation . London and New York: Rowman & Littlefield International.

- Dery, M. (1993). Culture jamming: Hacking, slashing, and sniping in the empire of signs . Westfield, NJ: Open Magazine Pamphlet Series.

- Dimitriadis, G. (2009). Performing identity/performing culture: Hip hop as text, pedagogy, and lived practice . New York: P. Lang.

- Drotner, K. (1999). Dangerous media: Panic discourses and dilemmas of modernity. Pedagogica Historia , 35 (3), 593–619.

- Edith, R. Q. (2003). Questions of knowledge in Australian media education. Television and New Media , 4 (4), 439–460.

- Frau-Meigs, D. , & Torrent, J. (2009). Media education policy: Toward a global rational. Comunicar , 15 (32), 10–14.

- Gilbert, J. (1986). A cycle of outrage: America’s reaction to the juvenile delinquent in the 1950s . New York: Oxford University Press.

- Gilfoyle, T. J. (2004). Street rats and gutter-snipes: Child pickpockets and street culture in New York City, 1850–1900. Journal of Social History , 37 (4), 853–882.

- Gillis, J. (1974). Youth and history . New York: Academic Press.

- Giroux. H. A. (2011). The crisis of public values in the age of the new media. Critical Studies in Media Communication , 28 (1), 8–29.

- Goldfarb, B. (2002). Visual pedagogy: Media cultures in and beyond the classroom . Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Hall, G. S. (1904). Adolescence: Its psychology and its relations to physiology, anthropology, sociology, sex, crime, and education . New York: D. Appleton.

- Hall, H. , & Jefferson, T. (Eds). (1976). Resistance through rituals: Youth subcultures in post-war Britain . London: Hutchinson.

- Hebdige, D. (1979). Subculture: The meaning of style . London: Routledge.

- Hoechsmann, M. , & DeWaard, H. (2015). Mapping digital literacy policy and practice in the Canadian education landscape . Media Smarts .

- Hoechsmann, M. , & Poyntz, S. R. (2012). Media literacies: A critical introduction . Chichester, UK; Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Hoggart, R. (1957). Uses of literacy: Changing patterns in English mass culture . Fair Lawn, NJ: Essential Books.

- Ito, M. (2008). Education vs. entertainment: A cultural history of children’s software. In K. Salen (Ed.), The ecology of games: Connecting youth, games, and learning (pp. 89–116). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Ito, M. , Soep, E. , Kligler-Vilenchikc, N. , Shresthovac, S. , Gamber-Thompson, L. , & Zimmerman, A. (2015). Learning connected civics. Curriculum Inquiry , 45 (1), 10–29.

- Jenkins, H. , Ford, S. , & Green, J. (2013). Spreadable media: Creating value and meaning in a networked culture . New York: New York University Press.

- Kahne, J. , Middaugh, E. , & Allen, D. (2014). Youth, new media, and the rise of participatory politics . Youth and Participatory Politics Research Network, Working Paper No. 1, 1–25.

- Kenway, J. , & Bullen, E. (2008). The global corporate curriculum and the young cyberflâneur as global citizen. In N. Dolby & F. Rizvi (Eds.), Youth moves: Identities and education in global perspective (pp. 17–32). London: Routledge.

- Kline, S. (1993). Out of the garden: Toys, TV, and children’s culture in the age of marketing . Toronto: Garamond Press.

- Kline, S. , Stewart, K. , & Murphy, D. (2006). Media literacy in the risk society: Toward a risk reduction strategy. Canadian Journal of Education , 29 (1), 131–153.

- Kubey, R. W. (2003). Why U.S. media education lags behind the rest of the English-speaking world. Television & New Media , 4 (4), 351–370.

- Leavis, F. R. , & Thompson, D. (1933). Culture and environment: The training of critical awareness . London: Chatto & Windus.

- Livingstone, S. , Haddon, L. , Hasebrink, U. , Olafsson, K. , O’Neill, B. , Smahel, D. , & Staksrud, E. (2014). EU Kids Online: Findings, methods, recommendations . London: EU Kids Online.

- Louv, R. (2008). Last child in the woods: Saving our children from nature-deficit disorder . Chapel Hill, NC: Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill.

- Maira, S. , & Soep, E. (Eds.). (2005). Youthscapes: The popular, the national, the global . Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

- McDougall, J. (2014). Media literacy: An incomplete project. In B. S. De Abreu & P. Mihailidis (Eds.), Media literacy education in action: Theoretical and pedagogical perspectives (pp. 3–10). New York: Routledge.

- McMahon, B. , & Edith, R. Q. (1999). Australian children and the media. In C. von Feilitzen & U. Carlsson (Eds.), Children and media: Image, education, participation (pp. 189–203). Gothenburg, Sweden: UNESCO International Clearinghouse on Children and Violence on Screen.

- McRobbie, A. (1993). Shut up and dance: Youth culture and changing modes of femininity. Young , 1 (2), 13–31.

- McRobbie, A. , & Thornton, S. L. (1995). Rethinking “moral panic” for multi-mediated social worlds. British Journal of Sociology , 46 (4), 559–574.

- Meikle, G. (2007). Stop signs: An introduction to culture jamming. In K. Coyer , T. Dowmunt , & A. Fountain (Eds.), The alternative media handbook (pp. 166–179). London: Routledge.

- Mitchell, K. (2004). Crossing the neoliberal divide: Pacific Rim migration and the metropolis . Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

- Montgomery, K. C. (2007). Generation digital: Politics, commerce, and childhood in the age of the Internet . Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Montgomery, K. C. (2008). Youth and digital democracy: Intersections of practice, policy, and the marketplace. In L. Bennett (Ed.), Civic life online: Learning how digital media can engage youth (pp. 25–49). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- New London Group . (1996). A pedagogy of multiliteracies: Designing social futures. Harvard Educational Review , 66 (1), 60–93.

- Osgerby, B. (2004). Youth media . London: Rutledge.

- Oswell, D. (2002). Television, childhood, and the home: A history of the making of the child television audience in Britain . Oxford and New York: Clarendon and Oxford University Press.

- Parsons, T. (1942). Age and sex in the social structure of the United States. American Sociological Review , 7 (5), 604–616.

- Postman, N. (1994). The disappearance of childhood . New York: Vintage Books.

- Poyntz, S. R. (2013a). Eyes wide open: Stranger hospitality and the regulation of youth citizenship. Journal of Youth Studies , 16 (7), 864–880.

- Poyntz, S. R. (2013b). Public space and media education in the city. In P. Fraser & J. Wardle (Eds.), Current perspectives in media education—beyond a manifesto for media education (pp. 91–109). London: Palgrave Macmillan.