Eliminating the Public Health Problem of Hepatitis B and C in the United States: Phase One Report (2016)

Chapter: 4 conclusion, 4 conclusion.

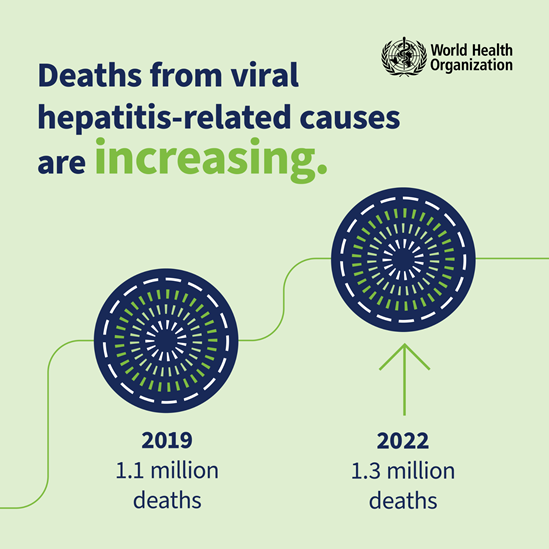

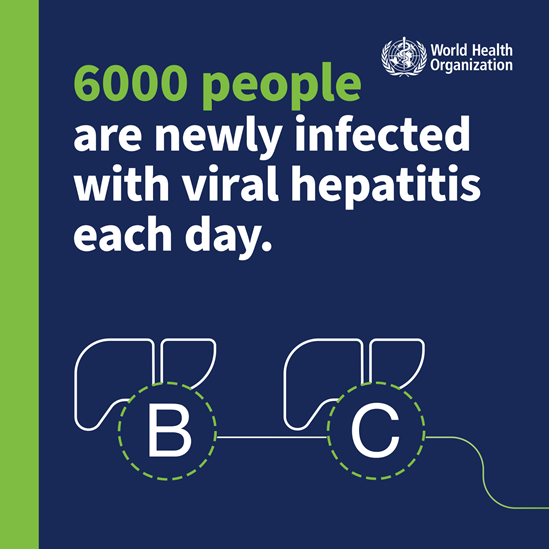

Hepatitis B and C kill about 20,000 people every year in the United States, and more than 1 million worldwide ( CDC, 2013 ; WHO, 2016 ). Hepatitis B virus (HBV) and hepatitis C virus (HCV) together account for most viral hepatitis, which kills more people every year than road traffic injuries, HIV and AIDS, and diabetes ( WHO, 2016 ). While the deaths from other common killers (i.e., malaria, tuberculosis, and HIV) have decreased since the early 2000s, deaths attributable to viral hepatitis continue to rise ( IHME, 2016 ).

These deaths can be averted. Three doses of HBV vaccine convey 95 percent immunity ( WHO, 2015 ). Though HBV infection cannot be cured, proper treatment can reduce viral load to an undetectable level ( EASL, 2012 ). While there is no vaccine for HCV, new curative treatments can eliminate the infection in over 95 percent of patients ( Afdhal et al., 2014 ; Charlton et al., 2015 ; Feld et al., 2014 ). Improved prevention and expanded access to viral hepatitis treatments could greatly reduce the burden of these infections. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that reducing the incidence of chronic hepatitis B and C by 90 percent and reducing mortality by 65 percent would save 7.1 million lives by 2030 ( WHO, 2016 ).

The United States has an opportunity and a responsibility to be part of the global action against hepatitis B and C. Already the Department of Health and Human Services’ viral hepatitis action plan lays out ambitious goals for improving prevention and care, and expanding hepatitis surveillance ( HHS, 2014 ). In the near term, the committee finds control of both diseases to be imminently possible. This committee also believes that a more ambitious goal is within our reach: Elimination of HBV and HCV as

public health problems in the United States. Although an elimination goal is entirely feasible, it is not necessarily likely without considerable attention to the barriers discussed in this report. First of all, disease reductions programs require an accurate understanding of the true burden of disease in a population. There is wide uncertainty in all estimates of HBV and HCV incidence and prevalence. Limited surveillance contributes to the uncertainty, as does the often asymptomatic course of the infections. Wider screening could help identify more chronically infected people, but screening for both infections is complicated.

Expanding screening for chronic HBV and HCV infections would surely identify new cases, but some would be among people with no access to care. Diagnosis with a chronic disease requires follow-up in primary care. Diagnosis of chronic hepatitis B carries with it the opportunity for treatment and monitoring to reduce the long-term risk of liver cancer and cirrhosis. It also offers the opportunity to vaccinate the patient’s uninfected contacts. Such follow-up is not an option for people who are uninsured and ineligible for Medicaid.

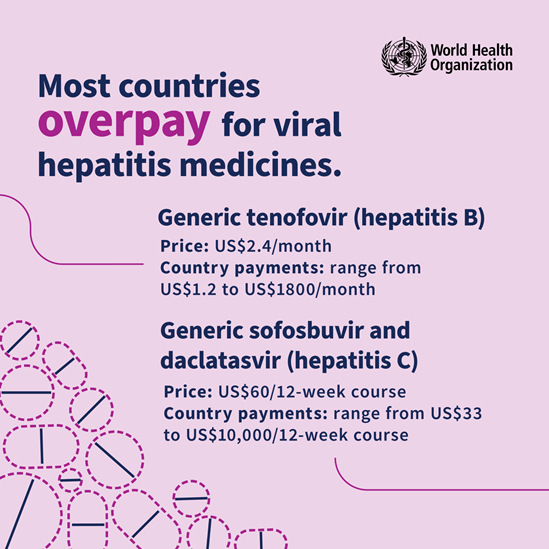

Hepatitis B and C care require a health workforce knowledgeable about long-term management of viral hepatitis. Much of the burden falls on primary care providers, who are already overworked, and extends indefinitely. There is no cure for hepatitis B, and infected individuals require management for the rest of their lives. Hepatitis C, in contrast, can be cured in 8 to 12 weeks, thanks to new direct-acting antiviral drugs. These drugs are expensive in the United States. The first of these treatments to gain Food and Drug Administration approval cost $1,000 per pill in 2014 ( Sanger-Katz, 2014 ). Competition from other products has brought the price down, but curing a chronically infected HCV patient in the United States still costs between $54,000 and $168,000 ( Bickerstaff, 2015 ; Loria, 2016 ). Even at such prices, curing hepatitis C is cost-effective ( Bickerstaff, 2015 ; Chhatwal et al., 2015 ; Najafzadeh et al., 2015 ; Younossi et al., 2015 ). The tension between the expense and cost-effectiveness of treating HCV puts Medicaid and insurance companies in a difficult position. They have responded by restricting access to treatment to only the sickest HCV patients. Even so, HCV treatments alone accounted for about a third of the sharp acceleration in drug spending between 2013 and 2014 ( Martin et al., 2015 ). It is currently not financially possible to treat all the estimated 2.7 to 4.7 million people thought to have chronic HCV infection given the current prices ( Edlin et al., 2015 ; Ward and Mermin, 2015 ).

The high price of treatment creates a tension in determining which patients’ treatment should be a priority. Those at most immediate risk of death are not necessarily those transmitting the virus, so the goals of ending HCV transmission and ending deaths from hepatitis C are somewhat at odds with each other.

There are creative strategies to mitigate this and other barriers to eliminating hepatitis B and C. Five years ago curing HCV infection with short-term, tolerable therapy seemed impossible. Similar breakthroughs in the treatment and management of hepatitis B are possible, as is the development of a prophylactic vaccine for HCV. This report has identified no shortage of research questions for basic scientists, pharmaceutical companies, and health services researchers. None of these questions is especially new, however. The challenge of directing more research interest to viral hepatitis remains.

It is also possible that limitations in disease surveillance, screening, treatment, vaccination, and research are all consequences of a more basic problem. Viral hepatitis is not a public priority in the United States. This too could change; attitudes toward disease can shift rapidly. Education and successful elimination of HBV among Alaskan Natives accompanied changes in local attitudes toward the disease. Liver disease often carries a stigma, perhaps because of its association with drug and alcohol use and sex; HBV and HCV can cause particular shame and distress in patients. Stigma, in turn, encourages silence and inaction among infected people, which is antithetical to any elimination program.

In making its conclusion regarding the feasibility of hepatitis B and C elimination, the committee acknowledges that considerable barriers must be overcome to meet these goals. For example, as elimination policies gain traction, the risk of infection should fall. Some people may respond by reducing efforts to protect themselves from infection. Public health campaigns highlighting the importance of elimination and the need to prevent individual infection might mitigate such behavior. A discussion of this and other solutions to the problems discussed in this report is not within the scope of the project. A second report, to be released in 2017, will outline a national strategy to eliminate hepatitis B and C. This report will discuss ways to address the critical factors and reduce the barriers to elimination set out in this document. The second phase of this project will also explore specific national targets for the elimination effort.

Afdhal, N., S. Zeuzem, P. Kwo, M. Chojkier, N. Gitlin, M. Puoti, M. Romero-Gomez, J. P. Zarski, K. Agarwal, P. Buggisch, G. R. Foster, N. Brau, M. Buti, I. M. Jacobson, G. M. Subramanian, X. Ding, H. Mo, J. C. Yang, P. S. Pang, W. T. Symonds, J. G. McHutchison, A. J. Muir, A. Mangia, P. Marcellin, and I. O. N. Investigators. 2014. Ledipasvir and sofosbuvir for untreated HCV genotype 1 infection. New England Journal of Medicine 370(20):1889-1898.

Bickerstaff, C. 2015. The cost-effectiveness of novel direct acting antiviral agent therapies for the treatment of chronic hepatitis C. Expert Review of Pharmacoeconomics & Outcomes Research 15(5):787-800.

CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). 2013. Viral hepatitis surveillance: United States, 2013. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Charlton, M., G. T. Everson, S. L. Flamm, P. Kumar, C. Landis, R. S. Brown, Jr., M. W. Fried, N. A. Terrault, J. G. O’Leary, H. E. Vargas, A. Kuo, E. Schiff, M. S. Sulkowski, R. Gilroy, K. D. Watt, K. Brown, P. Kwo, S. Pungpapong, K. M. Korenblat, A. J. Muir, L. Teperman, R. J. Fontana, J. Denning, S. Arterburn, H. Dvory-Sobol, T. Brandt-Sarif, P. S. Pang, J. G. McHutchison, K. R. Reddy, and N. Afdhal. 2015. Ledipasvir and sofosbuvir plus ribavirin for treatment of HCV infection in patients with advanced liver disease. Gastroenterology 149(3):649-659.

Chhatwal, J., F. Kanwal, M. S. Roberts, and M. A. Dunn. 2015. Cost-effectiveness and budget impact of hepatitis V virus treatment with sofosbuvir and ledipasvir in the United States. Annals of Internal Medicine 162(6):397-406.

EASL (Eurpoean Association for the Study of the Liver). 2012. EASL clinical practice guidelines: Management of chronic hepatitis B virus infection. Journal of Hepatology 57(1): 167-185.

Edlin, B. R., B. J. Eckhardt, M. A. Shu, S. D. Holmberg, and T. Swan. 2015. Toward a more accurate estimate of the prevalence of hepatitis C in the United States. Hepatology 62(5):1353-1363.

Feld, J. J., K. V. Kowdley, E. Coakley, S. Sigal, D. R. Nelson, D. Crawford, O. Weiland, H. Aguilar, J. Xiong, and T. Pilot-Matias. 2014. Treatment of HCV with abt-450/r-ombitasvir and dasabuvir with ribavirin. New England Journal of Medicine 370(17):1594-1603.

HHS (Department of Health and Human Services). 2014. Action plan for the prevention, care, & treatment of viral hepatitis. Washington, DC: Department of Health and Human Services.

IHME (Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation). 2016. Global burden of disease study 2013 (gbd 2013) data downloads—full results . http://ghdx.healthdata.org/global-burden-disease-study-2013-gbd-2013-data-downloads-full-results (accessed March 14, 2016).

Loria, P. 2016. This week in pharma: Questions for experts on Merck’s zepatier, Portola’s betrixaban . http://seekingalpha.com/article/3869636-week-pharma-questions-experts-mercks-zepatier-portolas-betrixaban (accessed March 14, 2016).

Martin, A. B., M. Hartman, J. Benson, and A. Catlin. 2015. National health spending in 2014: Faster growth driven by coverage expansion and prescription drug spending. Health Affairs (Millwood) 35(1):150-160.

Najafzadeh, M., K. Andersson, W. H. Shrank, A. A. Krumme, O. S. Matlin, T. Brennan, J. Avorn, and N. K. Choudhry. 2015. Cost-effectiveness of novel regimens for the treatment of hepatitis C virus. Annals of Internal Medicine 162(6):407-419.

Sanger-Katz, M. 2014. Boon for hepatitis C patients, disaster for prison budgets. The New York Times , August 7.

Ward, J. W., and J. H. Mermin. 2015. Simple, effective, but out of reach? Public health implications of HCV drugs. New England Journal of Medicine 373(27):2678-2680.

WHO (World Health Organization). 2015. Hepatitis B . http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs204/en (accessed January 15, 2016).

WHO. 2016 (unpublished). The case for investing in the elimination of hepatitis B and C as public health problems by 2030 .

Younossi, Z. M., H. Park, S. Saab, A. Ahmed, D. Dieterich, and S. C. Gordon. 2015. Cost-effectiveness of all-oral ledipasvir/sofosbuvir regimens in patients with chronic hepatitis C virus genotype 1 infection. Alimentary Pharmacology and Therapeutics 41(6):544-563.

Hepatitis B and C cause most cases of hepatitis in the United States and the world. The two diseases account for about a million deaths a year and 78 percent of world's hepatocellular carcinoma and more than half of all fatal cirrhosis. In 2013 viral hepatitis, of which hepatitis B virus (HBV) and hepatitis C virus (HCV) are the most common types, surpassed HIV and AIDS to become the seventh leading cause of death worldwide.

The world now has the tools to prevent hepatitis B and cure hepatitis C. Perfect vaccination could eradicate HBV, but it would take two generations at least. In the meantime, there is no cure for the millions of people already infected. Conversely, there is no vaccine for HCV, but new direct-acting antivirals can cure 95 percent of chronic infections, though these drugs are unlikely to reach all chronically-infected people anytime soon. This report, the first of two, examines the feasibility of hepatitis B and C elimination in the United States and identifies critical success factors. The phase two report will outline a strategy for meeting the elimination goals discussed in this report.

READ FREE ONLINE

Welcome to OpenBook!

You're looking at OpenBook, NAP.edu's online reading room since 1999. Based on feedback from you, our users, we've made some improvements that make it easier than ever to read thousands of publications on our website.

Do you want to take a quick tour of the OpenBook's features?

Show this book's table of contents , where you can jump to any chapter by name.

...or use these buttons to go back to the previous chapter or skip to the next one.

Jump up to the previous page or down to the next one. Also, you can type in a page number and press Enter to go directly to that page in the book.

Switch between the Original Pages , where you can read the report as it appeared in print, and Text Pages for the web version, where you can highlight and search the text.

To search the entire text of this book, type in your search term here and press Enter .

Share a link to this book page on your preferred social network or via email.

View our suggested citation for this chapter.

Ready to take your reading offline? Click here to buy this book in print or download it as a free PDF, if available.

Get Email Updates

Do you enjoy reading reports from the Academies online for free ? Sign up for email notifications and we'll let you know about new publications in your areas of interest when they're released.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- v.14(2); 2022 Feb

Viral Hepatitis as a Public Health Concern: A Narrative Review About the Current Scenario and the Way Forward

Ajeet s bhadoria.

1 Community and Family Medicine, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Rishikesh, Rishikesh, IND

Anushikha Dhankhar

Giten khwairakpam.

2 Public Health Sciences, Treat Asia/amfAR, Bangkok, THA

Gagandeep Singh Grover

3 Public Health Sciences, Department of Health & Family Welfare, Chandigarh, IND

Vineet Kumar Pathak

4 Community and Family Medicine, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Raipur, Raipur, IND

Pragya Pandey

Rohit gupta.

5 Gastroenterology and Hepatology, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Rishikesh, Rishikesh, IND

Viral hepatitis is one of the emerging public health problems, which urgently needs special attention. The disease has a varied presentation at the time of diagnosis, and it can progress from an accidental finding to life-threatening conditions like liver cirrhosis. It belongs to the rare group of diseases that can cause chronic inflammation inside the body, and it can have a delayed presentation. It contributes substantially to the global burden on healthcare. In terms of mortality, the burden due to viral hepatitis is similar to that of HIV and tuberculosis. It is among the major global public health challenges along with other communicable diseases, such as HIV, malaria, and tuberculosis; the major difference is that there are very limited preventive models in place for viral hepatitis, especially in developing countries like India. With limited resources for diagnosis and treatment, varied levels of presentation, and a rapidly increasing burden, it can become the next silent pandemic. In the current review, the authors aimed to compile the available global strategies for combating hepatitis, protocols available for disease surveillance, and the salient points from the national program for hepatitis control in India [National Viral Hepatitis Control Program (NVHCP)], and propose some recommendations. Ensuring a health facility equipped with a rapid diagnostic kit for screening, proper lab for the confirmation, robust Health Management Information System (HMIS) portal for the data management, and organizing regular workshops for physicians and lab technicians are some of the recommendations that we put forward.

Introduction and background

Global burden: viral hepatitis as a public health concern

Viral hepatitis refers to a pathologic condition wherein an infection due to hepatitis viruses causes inflammation of the liver [ 1 ]. It contributes substantially to the global burden on healthcare, with 248 million people infected with hepatitis B and 71 million infected with hepatitis C worldwide [ 2 ]. It is among the major global public health challenges besides other communicable diseases, such as HIV, malaria, and tuberculosis [ 3 ]. According to the World Health Organization Progress report on HIV, viral hepatitis, and sexually transmitted infections, the condition was responsible for 1.4 million deaths in the year 2016 [ 4 ]. Among all deaths attributed to viral hepatitis, 96% were due to hepatitis B virus (HBV) (48%) and HCV (47%) alone [ 5 ]. In addition, viral hepatitis is also among the major causes of mortality in people living with HIV (PLHIV). Among PLHIV, the global estimate of the burden of HIV-HCV coinfection and HIV-HBV coinfection is 2.75 million and 2.6 million respectively [ 6 ]. The importance given to viral hepatitis prevention can be gleaned from the fact that it has been selected as Target 3 of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, which emphasizes an urgent need to prevent and control viral hepatitis [ 7 ].

Epidemiology of viral hepatitis (Indian scenario)

The burden of viral hepatitis in India is currently wide-ranged, mainly due to the paucity of data. According to the National Health Profile 2019 report, a total of 1,64,826 cases of viral hepatitis were detected in India in the year 2017, out of which 89,780 were men and 74,509 women, with a total of 537 deaths. Also, out of the 1,64,289 cases reported across India in the year 2017, the top 10 states with the highest burden of viral hepatitis were Bihar, Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, Punjab, Delhi, Uttarakhand, Haryana, Maharashtra, and Rajasthan [ 8 ]. The proportion of hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg)-positive individuals in India ranges from 2 to 8%. It is also estimated that 15-25% of HBsAg carriers may later develop cirrhosis and cancer, consequently resulting in premature deaths. It has also been reported that around 40-50% of all hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) cases are attributable to chronic HBV infection while HCV is responsible for 12-32% of HCC cases [ 9 ]. Also, 20-30% of all cirrhosis cases are due to chronic HBV infection while 12-20% are due to chronic HCV infection [ 10 ].

The present article aims to assess the current status of viral hepatitis national programs and strategies implemented for its prevention, control, and management. The authors aim to compile the available global strategies for hepatitis, protocols available for disease surveillance, and the salient points from the national program for hepatitis control in India [National Viral Hepatitis Control Program (NVHCP)] and offer some recommendations.

Global strategies: guidelines on hepatitis B and C testing, 2017

Global Health Sector Strategy (GHSS) on Viral Hepatitis, 2016-2021 is the first GHSS on viral hepatitis, a mission that is expected to contribute to the achievement of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. It covers the first six years of the post-2015 health agenda, 2016-2021, building on the Prevention and Control of Viral Hepatitis Infection: Framework for Global Action [ 2 ] and on two resolutions on viral hepatitis adopted by the World Health Assembly in 2010 and in 2014 [ 11 ]. The strategy addresses all five hepatitis viruses (hepatitis A, B, C, D, and E), with a particular focus on hepatitis B and C, owing to the relatively severe public health burden they represent. This strategy proposes eliminating viral hepatitis as a public health threat by 2030. The success of this strategy requires the diagnosis of 90% of infected individuals and treatment of 80% of the diagnosed cases with the aim of a 65% reduction in mortality. This strategy was last updated in 2016 and required changes regarding the time and course of treatment owing to three key developments, viz the evolution of direct-acting antiviral (DAA) regimens; a reduction in the need for conducting genotyping after the approval of DAA medicines that are pan-genotypic in nature; rapid rolling out of treatment in low- and middle-income countries due to substantial cost reduction of DAAs. These guidelines entail evidence-based recommendations for program managers and healthcare providers for treating persons with chronic HCV infection. Guidelines for the care and treatment were updated on the principle of "screening, care, and treatment", which were issued by the WHO Guidelines Review Committee in 2017 [ 12 ]. Low- and middle-income countries have been reporting the majority of cases of HBV and HCV infections. However, the burden is more pronounced among specific population groups, such as persons who inject drugs (PWID) and individuals from certain indigenous communities.

Protocol for the surveillance of the fraction of cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma attributable to viral hepatitis in clinical centers of excellence, 2018

WHO recommends viral hepatitis surveillance that includes incidence of acute hepatitis and HBV and HCV prevalence, and mortality resulting from sequelae of liver disease, such as cirrhosis and HCC. Mortality reduction among HBV and HCV cases is used in the GHSS as one of the criteria for defining the goal of eliminating viral hepatitis as a public health threat by 2030 [ 10 ]. Therefore, laying down approaches to measure HBV- and HCV-related mortality are necessary. Initially, only deaths from acute infections were taken into account for measuring mortality; however, it ignored mortalities associated with chronic liver disease that resulted from hepatitis virus infection, such as cirrhosis and HCC.

Most countries do not have a systematic process to estimate national mortality rates from viral hepatitis, thereby needing to convert ad hoc approaches used in various research studies into routine surveillance systems. For this, deaths resulting from chronic liver disease (including cirrhosis and HCC) and the fraction of disease conditions that can be attributed to various hepatitis viruses can be used to estimate mortality. This protocol describes approaches that can be utilized in sentinel centers (e.g., hepatology or gastroenterology units) to estimate the proportion of individuals with cirrhosis and HCC due to HBV and HCV. This data is crucial to estimate the prevalence of cirrhosis and HCC, individuals in the advanced stage of liver disease, and mortality as a result of cirrhosis or HCC. The cases of cirrhosis and HCC can be followed up to understand the trends in disease development [ 13 ].

Hepatitis control through multi-disease testing

Although HIV-associated deaths have been controlled by antiretroviral therapy (ART), morbidity and mortality associated with coinfections like TB, HBV, and HCV pose a threat to investments in treatment. In 2016, approximately 2.75 million HIV patients also suffered from HCV coinfection [ 14 ]. Late detection of these coinfections results in infection progressing to an advanced stage by the time the patient reports to a healthcare facility, leading to costly care and management at the patient level. These coinfections also have a high potential for HIV transmission, its progression, and associated mortality. This necessitates the need to scale up screening for HIV and other coinfections in high-risk populations [ 15 , 16 ]. Multi-disease diagnostic platforms can help identify the presence of multiple infections and variations in the pathogen along with associated antimicrobial resistance. This will help streamline and simplify diagnosis and further management of multiple infectious diseases, thereby reducing cost, improving access for patients, and eventually controlling these outbreaks [ 17 ].

Elimination of hepatitis C virus infection in children, 2018

Approximately 6-11% of children acquire HCV from their infected mothers [ 18 ]. Out of these, only 20% show clearance within two years from birth, while the rest do not and develop chronic HCV infection later in life. As a result, these children are more likely to develop liver disease, which also tends to get severe with age. Adding to the problem is the limited preventive strategies and lack of evidence of their safety. DAAs have revolutionized HCV treatment across the world; however, evidence on their safety during pregnancy is scarce [ 19 ].

Standard operating procedures for enhanced reporting of cases of acute hepatitis, 2018

As per WHO, the surveillance of viral hepatitis must cover three key indicators of the disease burden: incidence (new infections of acute hepatitis), prevalence (chronic hepatitis cases), and mortality as a result of sequelae of infection including HCC and liver cirrhosis. To achieve a reduction in the incidence of HBV and HCV, countries need to adopt methods that identify associated risk factors. Although a major proportion of cases (50-70% for HBV and >80% for HCV) are asymptomatic, information on diagnosed symptomatic new infections can prove truly helpful and is the only way to study the change in disease trends among new infections in the community [ 20 ].

Progress on viral hepatitis, 2019: global targets, service coverage, and current status

Thanks to the ongoing hepatitis immunization and prevention programs, the incidence of hepatitis infection, especially hepatitis B, has declined. However, the reduction in mortality rates has been negligible, and this requires intervention for improving testing and treatment access. According to the WHO’s Progress Report [ 4 ] on HIV, Viral Hepatitis and Sexually Transmitted Diseases, 2019, the targets for 2020 and 2030 for viral hepatitis included a 30% reduction by 2020 and a 90% reduction by 2030 in the number of new chronic viral hepatitis B and C infections. Data suggest that in the year 2017, 1.1 million new cases of chronic hepatitis B were diagnosed; however, for chronic hepatitis C, only baseline data for the year 2015 is available, which reported 1.75 million newly diagnosed cases [ 21 ]. For reducing mortality, a target of 10% reduction by 2020 and 65% by 2030 was set for hepatitis B and C. However, only baseline data from the year 2016 is available, showing a total of 1.4 million deaths due to all types of viral hepatitis infections [ 22 ].

In order to achieve the 2030 targets for service coverage, the expedition of testing and treatment is necessary. Despite a strong immunization coverage program, the proportion of first doses given at birth is low [ 8 ]. Services to prevent mother-to-child transmission of HBV were set to have 50% coverage by 2020 and 90% coverage by 2030. As of 2017, there has been 43% global coverage of the services through a timely hepatitis B vaccination at birth [ 23 ]. About 97% of the blood donations were screened for quality assurance (as per baseline data of 2015) against a target of achieving 95% screening by 2020 and 100% by 2030 [ 2 ]. In the year 2017, 3.9% injection reuse was reported against a target of 50% injections to be administered following safety-engineering devices by 2020 and 90% by 2030. Harm-reduction services have also been observed to be in urgent need of action with only 33 needle sets provided per injection drug user in 2017 against the target of 200 sterile needle sets per injection drug user by 2020 and 300 by 2030 [ 24 ]. Diagnostic and treatment services also need to be made more equitable and accessible to achieve a target of diagnosing 30% of chronic viral hepatitis B and C cases by 2020 and 90% by 2030. However, only 10% (27 million) [ 25 ] of people with chronic hepatitis B and 19% (13.1 million) with chronic hepatitis C knew their status as per the 2016 baseline data. Out of these, only 4.5 million (17%) eligible and diagnosed chronic hepatitis B cases had been treated by the year 2016 and only five million diagnosed chronic hepatitis C cases by the year 2017 against a global target of 80% treatment coverage by 2030 [ 21 ].

Consolidated strategic information guidelines for viral hepatitis, 2019: planning and tracking progress towards elimination, 2019

Aiming to eliminate viral hepatitis as a public health threat by 2030, the first GHSS on viral hepatitis was endorsed by the World Health Assembly in the year 2016. The GHSS includes the implementation of five core interventions at an acceptable level of service coverage. These five core interventions include immunization, preventing vertical transmission of HBV, safe injection and blood transfusion, harm reduction for high-risk populations (e.g., those using injectable drugs), and testing and treatment. For the purpose of monitoring and evaluation, surveillance and documentation of cases, prevention, testing, and treatment of viral hepatitis have been implemented. The strategy also emphasizes the importance of implementing collaborative efforts in viral hepatitis programs with other different health programs, such as communicable disease control, HIV, TB, cancer care, immunization, and primary care to assist data collection and analysis without the need to set up separate systems [ 26 ].

Current status of National Viral Hepatitis Control Program (NVHCP): widening the scope

In India, HBsAg positivity in the general population ranges from 1.1 to 12.2%, with an average prevalence of 3-4%. Anti-HCV antibody prevalence in the general population is estimated to be between 0.09-15% [ 27 ]. Population-based syndromic and health facility-based surveillance of viral hepatitis is mandated under the Integrated Disease Surveillance Programme (IDSP). In India, approximately 40 million people are chronically infected with hepatitis B and 6-12 million people with hepatitis C. On the occasion of World Hepatitis Day on 28th July 2018, the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India launched the NVHCP [ 28 ]. The program covers all types of viral hepatitis infections (from A to E) and comprehensively focuses on all aspects, such as prevention of infection, early identification and treatment, and mapping of treatment outcomes. The program was launched along with the release of its operational guidelines, national laboratory guidelines for viral hepatitis testing, and national guidelines for the diagnosis and management of viral hepatitis.

On 24th February 2019, an advocacy event, "India’s Response to Viral Hepatitis", was held and Technical Guidelines for Diagnosis and Management of Hepatitis B and National Action Plan-Combating Viral Hepatitis in India were released, and the NVHCP website was launched. On World Hepatitis Day, 2019, the inauguration of the model treatment program was conducted at Sion Hospital, Mumbai, and the user manual of the NVHCP-MIS for hepatitis C and a national helpline number for viral hepatitis (1800-11-6666) were launched. Additionally, social media campaigns on prevention, identification of high-risk groups, the risk among pregnant women, as well as treatment-oriented campaigns about free drugs and diagnostics for hepatitis B and C, and laboratory testing and management of viral hepatitis were also created and run.

The program adopted an integrated approach and collaborated with other programs and schemes to provide a promotive, preventive, and curative package of services for individuals suffering from viral hepatitis. Under the ‘Training of Trainers’ initiative of the program, 800 experts were trained on diagnosis and management of viral hepatitis and NVHCP-MIS, while training on viral hepatitis, modes of transmission, and prevention were conducted for community members. Regular review and coordination meetings were also held. In addition, two national-level workshops were held for nodal officers to sensitize them about the services provided under the program. For state principal secretaries, mission directors, and state nodal officers for monitoring the program, video conferences were held twice.

The program has also seen major changes with respect to the existing infrastructure. Currently, model treatment centers have been established in all states and six union territories (UTs). This includes the establishment of 301 treatment centers in 285 districts for service delivery under the program. Nine states have made treatment sites functional in all the districts: Bihar, Haryana, Jharkhand, Kerala, Maharashtra, Mizoram, Nagaland, Punjab, and Rajasthan. Approximately 6.5 lakh serological tests have been done as of now for the diagnosis of viral hepatitis C and 16 lakh tests for hepatitis B, and more than 38,000 patients have been put on treatment for hepatitis C. The infection safety committee has been reconstituted. For enhancing skills and capacity building, the Extension for Community Healthcare Outcomes (ECHO) platform is being utilized for online clinical case discussion and conducting training for healthcare workers.

The main activities of the program involve prevention, diagnosis and treatment, monitoring and evaluation, surveillance and research, and review meetings. The NVHCP is coordinated by the center and state bodies. The National Viral Hepatitis Management Unit (NVHMU) is the center-level body and it controls and evaluates the implementation of programs across the country. The State Viral Hepatitis Management Unit (SVHMU) manages the program at the state level through a nodal officer of the State Health Society. At the district level, the program officer of the District Viral Hepatitis Management Unit (DVHMU) supervises program implementation and manages various activities such as supply chain management, outreach services, and logistics and training. Regarding the allocation of funds, the NVHMU at the center level is responsible for developing a program implementation plan (PIP) for states for achieving annual targets, and supervising, monitoring, and evaluating the overall program. The SVHMU assigns a nodal officer for program implementation at the state and district levels and develops PIP to be discussed and improvised after the approval from NVHMU. The DVHMU deals with ensuring the functionality of labs and treatment centers, identifying potential service delivery sites, training of staff, developing referral linkages, ensuring multi-program linkage, IEC material distribution, and data collection and reporting at the district level.

With the focus on the chronicity of the disease, the first cornerstone key component of the program was prevention through awareness generation, immunization against hepatitis B, and adhering to safe blood and injection practice. Early diagnosis through screening of pregnant women, and community involvement can boost adherence if treatment is placed as a second key component. Under the monitoring and evaluation component, effective linkages to the surveillance system would be established and operational research would be undertaken through the Department of Health Research (DHR) through an online web-based system. The last component as training and capacity building would be a continuous process and will be supported by National Centre for Disease Control (NCDC), the Institute of Liver and Biliary Sciences (ILBS), and state tertiary care institutes and coordinated by NVHCP. It would include the traditional cascade model of training through master trainers and various platforms available for enabling electronic, e-learning, and e-courses.

With the program being in its fourth year, a few challenges have been faced in successfully implementing it. The first concern is infrastructure and material management. Proper planning for the estimation of drugs and rapid diagnostic kits is a matter of huge concern for timely procurement and dissemination of materials. Also, the mobilization of human resources for effective service delivery in each district is a big challenge. Optimum procurement of quality testing kits, increasing viral load testing, reporting on the MIS platform, regular monitoring, and review of the program along with supportive supervision at all levels are some focus areas needing an immediate call to action.

Recommendations

Since the program is using preexisting healthcare infrastructure, it should be ensured that the healthcare facility that is designated as a treatment center is provided with rapid diagnostic kits for screening, machinery required for lab investigation, drugs, and a well-developed Health Management Information System (HMIS) portal. Program management units should disburse screening kits in a planned way for maximum utilization; this includes the distribution of kits in a tiered manner by following a top-to-bottom approach. Free-of-cost screening kits should be made available for screening key and bridge populations, as well as antenatal and preoperative screening. The willingness among the population and yield of screening for hepatitis should be studied [ 29 ]. There should be a well-established system for notification, confirmatory and auxiliary tests as well as treatment of rapid diagnostic test-positive patients. A decentralized approach could be adopted for better outcomes [ 30 ].

Many treatment centers (district hospitals) are not equipped with facilities for basic laboratory investigations to manage viral hepatitis, such as coagulation profile (PT/INR); in some centers, there is no HMIS portal, while in some other centers, even though screening kits and drugs are available, physicians are not aware of the program through which the logistics have been supplied. A well-developed HMIS portal may resolve these issues. Organizations like the Clinton Health Access Initiative (CHAI) and ECHO have shown promising results in the state of Punjab, and other states could also take assistance from these organizations for data management and capacity building [ 31 , 32 ]. The program has the provision for appointing human resources in the form of a medical officer, laboratory technician, data entry operator, and peer supporter. However, at some of the management units and treatment centers, the required staff has not been appointed yet; instead, there is a provision for incentivizing the preexisting healthcare workers. Considering the burden of patients, the feasibility of incentivization is questionable [ 33 ]. Moreover, many of these healthcare workers are appointed by the state and report to the chief medical officer at the district level rather than the district nodal officer for NVHCP, which sets two parallel systems in place; commissioning human resources exclusive to run the program could resolve this issue. Strengthening peer support can enable patient engagement with healthcare services, particularly for marginalized populations [ 34 ]. Under NVHCP, training workshops for physicians and lab technicians are routinely organized. The scope of such workshops needs to be broadened to include program managers, data entry operators, and peer supporters in order to have well-oriented and accountable staff at every level. Capacity-building should be synchronized with the development of infrastructure and human resources. Judicious nomination of specialty resources should be done for training, with a focus on training internists from centers where infrastructure and human resources have been provided.

There is a necessity for regular monitoring and conducting evaluation meetings and visits, as this can help understand the strengths and gaps in the implementation of the program at the grassroots level. Finally, based on the ground reports, state steering committees should remodel the operational guidelines for each state. It is also recommended to publish these reports to disseminate the best practices and strategies to overcome challenges.

Conclusions

The burden of viral hepatitis is increasing globally as well as in India. Being among the most populous countries, India contributes significantly to the disease burden. Despite having prevalence rates similar to HIV, tuberculosis, and malaria, political commitment and efforts made in the direction of prevention and control of viral hepatitis need more attention. Although the current scenario with respect to NVHCP has improved over the past few years, infrastructural, resource-related, and service-provision scenarios are still in a budding stage and need an urgent call to action owing to the growing burden of the disease at a faster rate than before. The program has a long way to go; however, with better initiatives at each level of the continuum of hepatitis control and prevention, appropriate action and care can contribute to improving the current trends and can accelerate the progress towards achieving the Sustainable Development Goal 3.3 sooner than expected.

The content published in Cureus is the result of clinical experience and/or research by independent individuals or organizations. Cureus is not responsible for the scientific accuracy or reliability of data or conclusions published herein. All content published within Cureus is intended only for educational, research and reference purposes. Additionally, articles published within Cureus should not be deemed a suitable substitute for the advice of a qualified health care professional. Do not disregard or avoid professional medical advice due to content published within Cureus.

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

YOUR FINAL GRADE - GUARANTEED UK Essay Experts

Disclaimer: This essay is provided as an example of work produced by students studying towards a biology degree, it is not illustrative of the work produced by our in-house experts. Click here for sample essays written by our professional writers.

This content is to be used for educational purposes only and may contain factual inaccuracies or be out of date.

Research into the Hepatitis B Virus

| ✅ Free Essay | ✅ Biology |

| ✅ 2194 words | ✅ 14th May 2018 |

Reference this

Get Help With Your Essay

If you need assistance with writing your essay, our professional essay writing service is here to help! Find out more about our Essay Writing Service

Abbreviation

What is shows, cite this work.

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing stye below:

Related Services

Essay Writing Service

- Dissertation Writing Service

- Assignment Writing Service

DMCA / Removal Request

If you are the original writer of this essay and no longer wish to have your work published on UKEssays.com then please:

Our academic writing and marking services can help you!

- Find out more about our Essay Writing Service

- Undergraduate 2:2

- 7 day delivery

- Marking Service

- Samples of our Service

- Full Service Portfolio

Related Lectures

Study for free with our range of university lecture notes!

- All Available Lectures

Freelance Writing Jobs

Looking for a flexible role? Do you have a 2:1 degree or higher?

Study Resources

Free resources to assist you with your university studies!

- Dissertation Resources at UKDiss.com

- How to Write an Essay

- Essay Buyers Guide

- Referencing Tools

- Essay Writing Guides

- Masters Writing Guides

Hepatitis B Essay

Hepatitis B

Page 2 Hepatitis B is a potentially life threatening liver infection caused by the virus HBV. A Hepatitis B infection could potentially become a chronic disease for some people because they run the risk of developing liver failure, cirrhosis of the liver or liver cancer if precautions are not taken. Cirrhosis causes permanent scarring to the liver. Some adults that have become infected with Hepatitis B do fully recover even if their symptoms are relentless. Symptoms can be mild to

Running head: EPIDEMIOLOGY PAPER - HEPATITIS B 1 Epidemiology Paper - Hepatitis B Concepts in Community and Public Health NRS-427V-0102 EPIDEMIOLOGY PAPER - HEPATITIS B Epidemiology Paper - Hepatitis B 2 ―Communicable disease‖ means an illness caused by an infectious agent or its toxins that occurs through the direct or indirect transmission of the infectious agent or its products from an infected individual or via an animal, vector or the inanimate environment to a susceptible animal

Epidemiology Hepatitis B Infection

Epidemiology Hepatitis B Dheer Chhabria MYP2A EPIDEMIOLOGY HEPATITIS B 1 The Causative Agent of Hepatitis B Infection The causative agent of the hepatitis B infection, known as serum hepatitis, is a Hepadna virus that attacks the liver causing inflammation of the liver . If this disease is left untreated it can result in liver cirrhosis , liver cancer, liver failure and death. The liver cancer caused by hepatitis B the virus is called Hepato Cellular Carcinoma which is the third most common cause

Epidemiology Hepatitis B

Epidemiology Hepatitis B affects 1 in 3 people worldwide (Hepatitis B Foundation [HBF], 2014). A vaccine has been available for over 30 years, yet it is the ninth leading cause of death worldwide (HBF, 2014). The epidemiology of hepatitis B, the role of the community health nurse along with the knowledge about what is being done to combat and reduce the impact of the virus gives a comprehensive look at hepatitis B. Hepatitis B virus (HBV) is a DNA virus, and belongs to the Hepadnaviridae family

Hepatitis B What is hepatitis B? Hepatitis means the inflammation of the liver. Hepatitis B, “formerly called serum hepatitis (Richard Adler)”, is caused by a serious liver infection with the hepatitis B virus (HBV) and the infection has two phases: acute and chronic (eMedicineHealth). Acute hepatitis B is short-term and occurs after being exposed to the virus and only few develop fulminant hepatitis which is very severe and life threatening. Chronic hepatitis can lead to “liver failure, liver

Hepatitis B Case Studies

said to be affected with hep-B in the United States than children. Since 1990 the routine for immunization against the disease has led to a decline in children for the past decades. African Americans are infected with the disease than either Hispanics or Caucasians, Alaskan Eskimos and Pacific Islanders however have a higher carrier status rate than other racial groups. Compared other racial groups Asian Americans are at increased risk of severe liver damage from hepatitis B. More males than females

Hepatitis B Research Paper

to offer, but what if they could do more? Bananas are also one of the best candidates to deliver oral vaccines for the hepatitis B Virus (HBV). Hepatitis B is caused by the hepatitis B virus (HBV) is a viral infection affecting the liver that can lead to serious illness or death, usually found in blood. There are approximately three hundred and fifty million carriers of hepatitis B in the world, an estimated amount of seventy five million to one hundred million of those infected with the virus dying

Mmwr Hepatitis B

MMWR Paper on Hepatitis B Microbiology 212-A April 27, 2012 Hepatitis B virus (HBV) is a DNA virus that affects the liver and belongs to the Hepadnaviridae group (Takkenberg, Weegink, Zaaijer, & Reesink, 2010). According to an article in Vox Sanguines, an international journal of transfusion medicine, (Takkenberg, Weegink, Zaaijer, & Reesink, 2010) “about 400 million people worldwide are chronically infected with HBV, and 2 billion people have serological evidence of past or present

Hepatitis B Vaccine

Hepatitis B Vaccine Hepatitis B is the most common liver infection in the world and is caused by the hepatitis b virus. The hepatitis b virus enters the body and travels to the liver via the bloodstream. In the liver the virus attacks the healthy liver cells and then multiplies. The cells create copies of them selves and the multiplying of the virus cells then triggers a response from the bodies’ immune system. Most people at this stage of the virus are unaware the have the virus as there are no

Hepatitis B Case

In Hepatitis B, it is the biggest part of your body your liver, it helps your body digest food and stores energy and also remove poison. What is Hepatitis B? A swerve from viral hepatitis transmitted in infected in the blood causing a fever and debility and jaundice. In Hepatitis B, you can also contact people by blood, semen or body fluids. How do you know if you have Hepatitis B? by yellow of skin of the eye, dark color urine and you will have pale movements. The worst part of having Hepatitis

Popular Topics

- Hepatitis C Essay

- Herbert Hoover Essay

- Herbs Essay

- Hercules Essay

- Hermann Hesse Demian Essay

- Hermann Hesse Siddhartha Essay

- Hero Archetype Essay

- Herodotus Essay

- Heroes Essay

- BiologyDiscussion.com

- Follow Us On:

- Google Plus

- Publish Now

Essay on Viral Hepatitis

ADVERTISEMENTS:

In this essay we will discuss about Viral Hepatitis. After reading this essay you will learn about: 1. Introduction to Hepatitis 2. Pathology of Hepatitis 3. Pathogenesis for Hepatitis 4. Hepatitis Vaccine 5. Classification of Hepatitis.

- Essay on the Classification of Hepatitis

Essay # Introduction to Hepatitis:

Viral hepatitis is a systemic disease with primary inflammation in the liver. Most of the viral hepatitis resemble each other in clinical symptoms; whereas Hepatitis B viral infection is mostly severe and fatal. Many cases of hepatocellular carcinoma are due to Hepatitis B and C viruses.

Essay # Pathology of Hepatitis:

The lesions in liver produced by all types of hepatitis viruses are similar and consist of infiltration of mononuclear cells (mainly lymphocytes), necrosis of hepatic cells, hyperplasia of Kupffer cells and variable degree of cholestasis. Parenchymal cell damage is due to hepatic cell degeneration and necrosis, ballooning of single cells and acidophilic degeneration of hepatocytes as they die.

In healthy carrier and chronic hepatitis due to Hepatitis B virus (HBV), large hepatocytes with a ground glass appearance of the cytoplasm may be seen; these cells contain Hepatitis B surface Antigen (HB s Ag). In chronic hepatitis, there is piece meal necrosis at first and later on fibrosis occurs which ultimately leads to cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma.

Essay # Pathogenesis for Hepatitis:

Though Hepatitis viruses differ antigenically, their clinical features are almost similar. These viruses cause acute inflammation of the liver with a clinical picture characterised by fever, anorexia and malaise followed by nausea, vomiting and liver tenderness (pre-icteric phase). This phase may last for a few days and sometimes it may continue longer (3 weeks or more).

As this phase subsides, the icteric phase appears with jaundice with dark urine, pale stools, obstructive jaundice with a slow recovery period of 4-6 weeks and longer severe cases. Symptomless or minor infection is also common in HAV and HEV types.

Essay # Hepatitis Vaccine:

Potato vaccine offered hope against Hepatitis A virus vaccine grown in genetically engineered potatoes—seemed to protect more people who ate them, reported by Times of India in February 2005.

About 60% of the volunteers who ate these potatoes showed an immune response that should protect against infection with hepatitis B virus that is shown to stimulate the immune system response.

Antibodies raised in most of 60% volunteers who ate more than three pieces of the genetically engineered potatoes and more than those who ate two pieces.

Hepatitis B virus vaccine shot should be kept refrigerated and expensive—meaning that it cannot be used in many poor countries. People prefer edible vaccine than to get a shot.

Scientists are working to grow the vaccine in banana, tomato or tobacco.

In 1996, 115 million people were infected with HBV even though vaccine isolated from yeast became available in 1986.

Global mortality due to HBV was to be one million cases per year. Hepatitis B vaccine booster was not required as published in Lancet, 2005—reported in Times of India (Oct. 2005) because of immunizing effect of Hepatitis B vaccine lasts for ten years. Infants and adolescent immune system recalls the response to Hepatitis B virus for more than 10 years after immunization.

Essay # Classification of Hepatitis:

There are six major types of primary hepatotrophic, acute hepatitis viruses. Besides, other viruses are also responsible for acute viral hepatitis.

Related Articles:

- Essay on Hepatitis A Virus (HAV)

- Essay on Hepatitis B Virus (HBV)

Biology , Disease , Microbiology , Essay , Viruses , Viral Hepatitis , Essay on Viral Hepatitis

- Anybody can ask a question

- Anybody can answer

- The best answers are voted up and rise to the top

Forum Categories

- Animal Kingdom

- Biodiversity

- Biological Classification

- Biology An Introduction 11

- Biology An Introduction

- Biology in Human Welfare 175

- Biomolecules

- Biotechnology 43

- Body Fluids and Circulation

- Breathing and Exchange of Gases

- Cell- Structure and Function

- Chemical Coordination

- Digestion and Absorption

- Diversity in the Living World 125

- Environmental Issues

- Excretory System

- Flowering Plants

- Food Production

- Genetics and Evolution 110

- Human Health and Diseases

- Human Physiology 242

- Human Reproduction

- Immune System

- Living World

- Locomotion and Movement

- Microbes in Human Welfare

- Mineral Nutrition

- Molecualr Basis of Inheritance

- Neural Coordination

- Organisms and Population

- Photosynthesis

- Plant Growth and Development

- Plant Kingdom

- Plant Physiology 261

- Principles and Processes

- Principles of Inheritance and Variation

- Reproduction 245

- Reproduction in Animals

- Reproduction in Flowering Plants

- Reproduction in Organisms

- Reproductive Health

- Respiration

- Structural Organisation in Animals

- Transport in Plants

- Trending 14

Privacy Overview

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |

- Search Menu

- Sign in through your institution

- Why Publish with Gastroenterology Report

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access Options

- Self-Archiving Policy

- About Gastroenterology Report

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

Introduction, authors’ contributions, acknowledgements.

- < Previous

Hepatitis D infection: from initial discovery to current investigational therapies

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Ben L Da, Theo Heller, Christopher Koh, Hepatitis D infection: from initial discovery to current investigational therapies, Gastroenterology Report , Volume 7, Issue 4, August 2019, Pages 231–245, https://doi.org/10.1093/gastro/goz023

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Hepatitis D is the most severe form of viral hepatitis associated with a more rapid progression to cirrhosis and an increased risk of hepatocellular carcinoma and mortality compared with hepatitis B mono-infection. Although once thought of as a disappearing disease, hepatitis D is now becoming recognized as a serious worldwide issue due to improvement in diagnostic testing and immigration from endemic countries. Despite these concerns, there is currently only one accepted medical therapy (pegylated-interferon-α) for the treatment of hepatitis D with less than desirable efficacy and significant side effects. Due to these reasons, many patients never undergo treatment. However, increasing knowledge about the virus and its life cycle has led to the clinical development of multiple promising new therapies that hope to alter the natural history of this disease and improve patient outcome. In this article, we will review the literature from discovery to the current investigational therapies.

Hepatitis D is a rare form of viral hepatitis that was first described in 1977 by Rizzetto et al . through immunofluorescence detection of the delta antigen and anti-delta antibody in the serum and liver tissues of hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) carriers [ 1 ]. While it has been estimated to affect 15–20 million people worldwide, more recent data suggest that the global disease burden may be closer to 62–72 million [ 2 ]. Hepatitis D virus (HDV) is an incomplete RNA virus that requires the assistance of the hepatitis B virus (HBV), specifically the HBsAg, to be infectious in humans [ 3 ]. Once chronicity is established, HDV has been described as the most severe form of viral hepatitis, with progression to cirrhosis in 10%–15% of patients within 2 years and in 70%–80% of patients within 5–10 years [ 4 , 5 ]. Despite this, a lack of adequate treatment options currently exists for HDV. Current international guidelines suggest the use of pegylated-interferon-α (peg-INF-α), although sustained virological response (SVR) rates with this treatment are reported to be only 20%–30% [ 6–8 ]. In addition, even after SVR is achieved, late relapse remains an issue [ 9 ]. Recent advances in our understanding of the HDV viral cycle have led to the development of several promising investigative therapies that are under investigation.

In this piece, we review the virology, epidemiology, diagnosis, clinical presentation, natural history, outcomes and the available and investigative treatments pertaining to this disease.

Viral structure and life cycle

HDV is a small, spherical RNA virus measuring ∼36 nm in diameter with an inner nucleocapsid that consists of a short (∼1.7-kb) single-stranded, circular RNA and approximately 200 molecules of hepatitis D antigen (HDAg) [ 10 , 11 ]. This viral genome is the smallest among known mammalian viruses and shares structural similarity to viroid RNAs [ 12–14 ]. It encodes for a single protein, the HDAg, which exists in two forms: the small HDAg (S-HDAg) and large HDAg (L-HDAg). Structurally, the two forms are identical except that the L-HDAg has an additional 19 amino acid sequence at the C-terminus [ 15 ]. The outer coat of the HDV virion consists of components taken from HBV, thus mandating a co-infective process with HBV, which includes the small, medium and large HBsAg [ 3 ]. The isoforms of HBsAg are embedded in a lipid envelope surrounding the HDV genome and HDV antigen isoforms. The large HBsAg then undergoes a process called myristoylation at the N-terminus to prepare for cell entry [ 16–18 ]. The life cycle of HDV is depicted in Figure 1 . First, the HDV virion binds to the human hepatocyte through an interaction between the myristoylated N-terminus of the pre-S1 domain of the large HBsAg and the host receptor, which has been identified as the multiple transmembrane receptor sodium taurocholate cotransporting polypeptide (NTCP) located on the basolateral membrane of hepatocytes [ 19 , 20 ]. After entry, the HDV genome is translocated to the nucleus via the HDAg [ 21 ]. Upon arriving in the nucleus, HDV commandeers host RNA polymerase II, a DNA-directed RNA polymerase, for transcription of HDV RNA [ 22 ]. Replication of the HDV occurs through a rolling-circle mechanism [ 12 , 23 ]. The initial step is synthesis of multimeric linear transcripts from the circular genomic template. Afterwards, these multimeric linear transcripts are cleaved into monomers by autocatalytic self-cleaving sequences called ribozymes. Subsequently, monomer RNAs are ligated by the ribozyme into an antigenomic, monomeric, circular RNA that serves as a template for another round of rolling-circle replication. The finished product is a circular genomic HDV RNA [ 13 ].

Hepatitis D virus viral life cycle and sites of drug target. 1. Hepatitis D virus (HDV) virion attaches to the hepatocyte via interaction between hepatitis B surface antigen proteins and the sodium taurocholate cotransporting polypeptide (NTCP), a multiple transmembrane transporter. 2. HDV ribonucleoprotein (RNP) is translocated to nucleus mediated by the hepatitis D antigen (HDAg). 3. HDV genome replication occurs via a ‘rolling-circle’ mechanism. 4. HDV antigenome is transported out of the nucleus to the endoplasmic reticulum (ER). 5. HDV antigenome is translated in the ER into small HDAg (S-HDAg) and large HDAg (L-HDAg). 6. L-HDAg undergoes prenylation prior to assembly. 7. S-HDAg is transported back to the nucleus where it supports HDV replication. 8. New HDAg molecules are associated with new transcripts of genomic RNA to form new RNPs that are exported to the cytoplasm. 9. New HDV RNP associates with hepatitis B virus (HBV) envelop proteins and assembled into HDV virions. 10. Completed HDV virions are released from the hepatocyte via the trans-Golgi network.

Three different RNAs are generated during the replication process: the HDV genome, the antigenome that is its exact complement and a third smaller antigenome that contains the open reading frame (ORF) that codes for the HDAg [ 22 ]. During replication, the HDV genome and antigenome collapses into a characteristic unbranched rod-like structure [ 24 ]. Both forms of HDAg are translated in the endoplasmic reticulum from the ORF located on the antigenomic HDV RNA strand [ 25 ]. The S-HDAg plays a significant role in replication, since it is required for RNA synthesis, while the L-HDAg inhibits RNA synthesis and is required for packaging. Cellular adenosine deaminase acting on RNA (ADAR) editing of the amber codon on the viral antigenome RNA enables the HDV to switch from replication to packaging [ 24 ].

The HDV RNA and HDAg proteins interact to form a ribonucleoprotein (RNP) particle at a molar ratio of 200 [ 12 , 26 ]. The modification of post-translation HDAg proteins is essential for this process but is also crucial for HDV replication and HDV-virion assembly [ 27 , 28 ]. One of these post-translational modification processes is called farnesylation, which is crucial for HDV-virion assembly and serves as a target for drug action. At the C-terminal of the L-HDAg is a 19-amino acid polypeptide that includes the C-terminal CXXX-box motif (where C = cysteine and X = any amino acid), which is the substrate for prenyltransferases to add a prenyl lipid group [ 15 , 29 ]. Farnesyl is one of the prenyl groups that can be added via the enzyme farnesyltransferase in a process specifically called farnesylation. Farnesylation anchors the RNP to the endoplasmic reticulum membrane where HBV envelop proteins are made and then makes the RNP more lipophilic and more amenable to interactions with HBsAg. This C-terminal 19-amino acid residue region, which is not well conserved between different HDV genotypes, plays a key role in the varied assembly efficiencies between genotypes, which likely has pathologic implications [ 30–32 ]. Interestingly, HBV envelope proteins are made in excess so, even when HBV is suppressed, additional HDV virions can still be assembled [ 33 ].

Finally, once the RNP interacts with the envelop protein of HBV and the HDV is assembled, the HDV virion is now ready for release. The HDV virion is released via the trans-Golgi network, where it can go on to infect other hepatocytes. However, the exact mechanism of HDV-virion release remains unknown [ 15 ].

Viral genotypes

To date, eight distinct HDV genotypes have been recognized, with two to four subtypes per genotype characterized by >90% similarity over the entire genome sequence [ 2 , 34 , 35 ]. The geographical distributions of the HDV genotypes have changed over time, most probably due to human migration patterns. Currently, genotype 1 is the most prevalent worldwide and the predominant genotype in Europe and North America [ 36 ]. Genotype 2 was previously confined to Asia but has now emerged in Middle Eastern countries including Iran [ 37 ] and Egypt [ 38 ]. Genotype 3 is mainly found in the Amazon Basin in South America and is the most different of all the genotypes exhibiting ∼40% divergence at the nucleic acid level [ 39 ]. Genotype 4 is predominately found in Taiwan, China and Japan [ 35 ]. Meanwhile, genotypes 5, 6, 7 and 8 have traditionally been found only in Africa, but recent reports describe the migration genotypes 5, 6 and 7 to various parts of Europe [ 40–42 ]. Notably, central Africa is thought to be main site of HDV diversification, with the presence of genotypes 1, 5, 6, 7 and 8 [ 35 ].

It is well known that specific HDV genotypes influence clinical outcomes. HDV genotype 3 appears to be the most pathogenic of all the HDV genotypes [ 43 , 44 ]. HDV genotype 1 patients have lower rates of remission, more aggressive disease and worse outcomes than HDV genotype 2 patients [ 45 , 46 ]. For example, in a study from Taiwan, Su et al . reported significantly lower rates of remission in HDV genotype 1 compared to HDV genotype 2 (15.2% vs 40.2%, P = 0.007) and more adverse outcomes (cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma [HCC] or mortality) (52.2% vs 25.0%, P = 0.005) [ 45 ]. This is likely due to HDV genotype 1 being a more efficient genotype in terms of virion assembly and RNA editing than genotype 2, resulting in the secretion of more viral particles [ 31 , 32 ].

Epidemiology and risk factors

The seroprevalence of HDV among HBsAg-positive carriers has substantial variations worldwide. These are depicted in Table 1 . Interestingly, more recent data have shown that 8% of the general Mongolian population is estimated to be positive for HDV [ 2 ]. Notably, in the USA, the prevalence of HDV among HBV carriers has been reported to range from 2% to 50%, depending on the patient population [ 63–66 ]. A large study of the US Veteran’s Affairs medical system more recently reported an HDV seroprevalence of 3.4% among patients with chronic HBV who are tested for HDV [ 78 ]. A study using the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey reported a HDV seroprevalence of 42% among HBV carriers [ 65 ]. Finally, the highest estimation of HDV seroprevalence came from a study of HBV-positive intravenous drug users (IVDU), which showed that the seroprevalence of HDV increased from 29% in 1988–1989 to 50% in 2005–2006 [ 66 ]. However, a general lack of HDV RNA validation in these studies prevents estimation of true HDV prevalence.

Epidemiology of hepatitis D

| Endemic country . | Seroprevalence . | Non-endemic country . | Seroprevalence . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Brazil | 41.9% [ ] | Australia | 4.1%–4.8% [ , ] |

| China | 3.5%–13.1% [ ] | England | 2.6%–8.5% [ , ] |

| Egypt | 9.9% [ ] | Greece | 4.2% [ ] |

| Germany | 8%–10.9% [ , ] | Japan | 6% [ ] |

| India | 10.6%–37.5% [ , ] | Jordan | 2% [ ] |

| Iran | 17%–48% [ , ] | United States | 2%–50% [ ] |

| Italy | 8.3%–23.0% [ ] | ||

| Mongolia | 56.5% [ ] | ||

| Pakistan | 16.6%–58.6% [ ] | ||

| Saudi Arabia | 8.6% [ ] | ||

| Taiwan | 4.4%–15.3% [ , ] | ||

| Thailand | 21.8%–65.5% [ , ] | ||

| Tunisia | 17.7% [ ] | ||

| Turkey | 7%–45.5% [ , ] |

| Endemic country . | Seroprevalence . | Non-endemic country . | Seroprevalence . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Brazil | 41.9% [ ] | Australia | 4.1%–4.8% [ , ] |

| China | 3.5%–13.1% [ ] | England | 2.6%–8.5% [ , ] |

| Egypt | 9.9% [ ] | Greece | 4.2% [ ] |

| Germany | 8%–10.9% [ , ] | Japan | 6% [ ] |

| India | 10.6%–37.5% [ , ] | Jordan | 2% [ ] |

| Iran | 17%–48% [ , ] | United States | 2%–50% [ ] |

| Italy | 8.3%–23.0% [ ] | ||

| Mongolia | 56.5% [ ] | ||

| Pakistan | 16.6%–58.6% [ ] | ||

| Saudi Arabia | 8.6% [ ] | ||

| Taiwan | 4.4%–15.3% [ , ] | ||

| Thailand | 21.8%–65.5% [ , ] | ||

| Tunisia | 17.7% [ ] | ||

| Turkey | 7%–45.5% [ , ] |

Despite the various HDV epidemiological reports, there continues to be insufficient data on the true global prevalence of HDV [ 2 ]. This is attributable to several factors. First, reported rates are likely to be underestimations, stemming from incomplete population testing because of a lack of clinician awareness resulting in a lack of diagnosis along with a lack of availability of HDV clinical tests. In a nationwide study in the USA of 25 603 HBV patients, only 8.5% of patients were ever tested for HDV [ 78 ]. Manesis et al . reported that only a third of Greek patients with chronic hepatitis B (CHB) were tested for HDV [ 55 ]. El Bouzidi et al . similarly reported that only 40% of British chronic HBV patients were tested for anti-HDV in patients with positive HBsAg [ 40 ]. Special focus also needs to be made for HDV testing among patients with hepatitis C virus (HCV) and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) due to a high rate of co-infection because of shared risk factors such as transfusions, tattooing, IVDU and high-risk sexual practices [ 79 ]. For example, reported co-infection rates with HCV have ranged from 26%–73% [ 42 , 48 , 53 , 68 ] and HIV of 12.7% [ 42 ].

Second, studies from the same country have reported discrepant numbers that may be due to significant geographical variations even within the same country. For example, a meta-analysis from Turkey described that the HDV seroprevalence of west Turkey was 4.8%, while the seroprevalence of HDV in southeast Turkey was 46.3% [ 80 ]. In addition, most of the epidemiologic studies on the seroprevalence of HDV among chronic HBV patients did not require HDV polymerase chain reaction (PCR) confirmation as an inclusion factor, further preventing the estimation of the true prevalence of HDV. Finally, the timing of the publication is also important because the seroprevalence of HDV declined drastically after the late 1980s due to the implementation of HBV vaccine programs around the world [ 81–83 ].

Despite an earlier notion that HDV was a disappearing disease in many parts of the world, this has proven to be no longer the case. In fact, more recent data have shown that the prevalence of HDV has remained stable or has increased in many endemic and non-endemic countries due to an increase in associated risk factors such as immigration, IVDU, men-who-have-sex-with men (MSM) and intra-familial spread [ 41 , 67 , 71 , 79 , 84 , 85 ]. For example, a collection of studies from Italy reported a decline in the prevalence of HDV among HBsAg-positive patients from 23% in 1987 to 14% in 1992 to 8.3% in 1997, which was attributed to HBV-vaccination programs [ 67 , 86 , 87 ]. However, more recent data have suggested that the prevalence of HDV in Italy has either remained stable at 8.1% [ 85 ] or has rebounded to 11.3% [ 84 ]. Lin et al . showed that the prevalence of HDV increased from 38.5% to 89.8% among HIV-infected IVDU patients with HBV from 2001 through 2012 [ 71 ]. Furthermore, outbreaks of HDV have been especially rampant among areas of with low social-economic levels [ 79 , 80 ]. Due to immigration from endemic countries, multiple studies have reported an increase in the prevalence of HDV in countries in which HDV was previously uncommon [ 48 , 49 , 53–55 ]. In a study by Coghill et al . from Australia, those born in Africa were shown to have a higher risk ratio (RR) for HDV infection (RR, 1.55; 95% confidence interval [95% CI], 1.14–2.09) [ 48 ]. Cross et al . reported in a study from England that over half of their HDV patients were from regions of the world where HDV is endemic including Southern or Eastern Europe (28.1%), Africa (26.8%) and the Middle East (7.3%) [ 53 ]. Similarly, Manesis et al . reported that immigrants represented over half of the HDV burden in Greece [ 55 ].

Due to these reasons, HDV is now becoming a serious issue worldwide. A recently published systematic review and meta-analysis reported a worldwide HDV seroprevalence of 14.6% among HBV-positive patients compared with prior estimates of approximately 5%, with a substantially higher seroprevalence in the IVDU and high-risk sexual-behavior populations [ 2 , 88 ]. These findings stress the importance of HDV awareness regardless of country of origin. Indeed, HDV needs to be especially considered in high-risk populations such as among patients who are immigrants from endemic countries, IVDU, MSM and with positive family members.

Diagnostics

This section will focus on the different diagnostic modalities and tests that are available ( Table 2 ). When HDV was first discovered, the diagnosis of HDV relied on immunohistochemical staining of HDAg in liver tissue that could only be obtained through liver biopsy [ 1 ]. Testing for serum immunoglobulin M (IgM)/immunoglobulin G (IgG) anti-HDV quickly became available, which, in addition to liver chemistries and the patient’s clinical picture, enabled classification of patients into the two stages of HDV infection: acute and chronic HDV [ 89 ]. The use of serum IgM/IgG anti-HDV for this purpose was not perfect, however, as anti-HDV IgG is not 100% specific to chronic HDV and can be found in acute HDV. Likewise, anti-HDV IgM is not specific to acute HDV and can frequently be found in chronic HDV [ 61 , 90 , 91 ].

Diagnostic tests for hepatitis D

| Diagnostic test . | Detection . | Significance . | Comments . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Liver HDAg | Detects HDV antigen on liver histology via immunohistochemical staining | Indicates active infection | Lack of availability. Poor sensitivity |

| Serum HDAg | Detects HDV antigen in the serum | Indicates active infection but disappears quickly | Rarely performed. May be undetectable in chronic HDV |

| Anti-HDV IgM | Detects the presence of IgM antibodies against HDV in the serum | Indicates active infection, usually found in acute but can be found in chronic HDV | Often negative in chronic HDV but can be positive during periods of increased HDV replication |

| Anti-HDV IgG | Detects the presence of IgG antibodies | Usually indicates previous infection or chronic HDV | Appears late in acute HDV but persistent in chronic HDV |

| HDV RNA PCR (Qualitative) | Detects HDV RNA in the serum | Indicates active infection, can be found in acute or chronic HDV | LLOD depends on the assay. Useful for diagnosis |

| HDV RNA PCR (Quantitative) | Quantifies HDV RNA in the serum | Indicates active infection, can be found in acute or chronic HDV | LLOQ depends on the assay. Useful for treatment monitoring |

| HDV genotyping | Determines HDV genotype | Distinguish specific HDV genotype (1–8) with possible prognostic significance | Not commercially available |

| Diagnostic test . | Detection . | Significance . | Comments . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Liver HDAg | Detects HDV antigen on liver histology via immunohistochemical staining | Indicates active infection | Lack of availability. Poor sensitivity |

| Serum HDAg | Detects HDV antigen in the serum | Indicates active infection but disappears quickly | Rarely performed. May be undetectable in chronic HDV |

| Anti-HDV IgM | Detects the presence of IgM antibodies against HDV in the serum | Indicates active infection, usually found in acute but can be found in chronic HDV | Often negative in chronic HDV but can be positive during periods of increased HDV replication |

| Anti-HDV IgG | Detects the presence of IgG antibodies | Usually indicates previous infection or chronic HDV | Appears late in acute HDV but persistent in chronic HDV |

| HDV RNA PCR (Qualitative) | Detects HDV RNA in the serum | Indicates active infection, can be found in acute or chronic HDV | LLOD depends on the assay. Useful for diagnosis |

| HDV RNA PCR (Quantitative) | Quantifies HDV RNA in the serum | Indicates active infection, can be found in acute or chronic HDV | LLOQ depends on the assay. Useful for treatment monitoring |

| HDV genotyping | Determines HDV genotype | Distinguish specific HDV genotype (1–8) with possible prognostic significance | Not commercially available |

HDAg, hepatitis D antigen; HDV, hepatitis d virus; RNA, ribonucleic acid; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; LLOD, lower limits of detection; LLOQ, lower limits of quantification.