- Career Advice

8 Motivational Tips for Dissertation Writing

By Elisa Modolo

You have / 5 articles left. Sign up for a free account or log in.

Istock.com/spicy truffel

Writing a dissertation is a grueling process that does not just require academic prowess, an excellent writing style and mastery of a very specific area of knowledge. It also demands discipline (in setting a writing schedule), perseverance (in keeping that schedule) and motivation (to get the writing done and the project completed).

The beginning of the academic year, with its array of looming deadlines, administrative procedures and mandatory adviser/graduate students/department meetings, can make it difficult to find motivation and hold on to it. The COVID-19 pandemic, with its utter disruption of normal operations, exacerbates this problem even further.

So, if you need additional motivation in these trying times, maybe a practice I followed when writing my own dissertation can help. I call it Motivational Post-it: a series of brief slogans to write on Post-it notes and put all over your desk or workstation, so you can see them every time you sit down to work. Here are some of mine.

Start with one (line/page). The idea of writing what may amount to hundreds of pages can feel disheartening, especially if you just started your project. So, if you find yourself staring at a white page while the white page stares back at you, don't think about the arduous work ahead. Focus on the present rather than the future. Start with one line or page. One is better than zero, and the lines, as well as pages, will accumulate over time if you keep it going regularly. Breaking down the work in more manageable chunks will get you writing and help you push through your writer's block.

Obsessing is not progressing. This is for all the perfectionists out there. I know it is not realistic to just stop obsessing on each line/quote/passage if you have done it for years and that is precisely what makes you great in an academic environment. Been there, done that! Thus, I propose what I call a “timed obsession”: leave a brief period -- such as three days -- out of the allotted time to obsess over the details of a specific chapter or phase of the project. Then, whether that chapter/project is now up to your standards or not, after your timed obsession, you let it go . You send it in as it is.

Finished is better than perfect. This is again along the lines of perfectionism, but it applies more broadly to the dissertation in its entirety rather than to the single chapters. Your dissertation is not (yet) an academic book. It has to pass the scrutiny of your dissertation committee -- not be published by a prestigious academic publishing house. Even if you wish to publish it in the future, that is not your goal right now.

Remember: the perfect dissertation does not exist, and a good dissertation is a finished or written dissertation. Prioritize writing all the chapters or completing all the experiments or sets of data rather than spending precious time refining small details in already written chapters.

Interruptions happen. When creating your writing schedule, try to plan with reasonable expectations on the amount and quality of your writing. That means you will need to accommodate the fact that some days you will exceed your writing goals, and some days you will not reach them, so your schedule will have to be adjusted accordingly.

Remember also to account for interruptions: it is normal and human to feel physically exhausted and/or emotionally drained in the middle of the daily emergency that is COVID-19. Recognize that such times will come and that you need a writing schedule flexible enough to allow you to get back on track without feeling overwhelmed.

Work backward. Write your introduction at the end. The intro to your entire dissertation? After you have written all the chapters, so you know precisely where you are going and which considerations to highlight. The intro to each single chapter? Again, after you have conducted your analysis, so you know which points you want your readers to concentrate on. In this way, you will create a more compelling text and avoid losing writing time at the very beginning that should be dedicated to the meat of your argument. (Note: This approach may not apply to those dissertations that acquire a linear approach.)

The most you can do is your best. Give it your best shot. Still feeling like your argument could have been more convincing or better framed? You did what you could, so you are at peace with your conscience. You cannot do more than your best.

Celebrate your accomplishments. Celebrate your achievements to feed your motivation. You sent your chapter in? Take one day to destress -- possibly with some pampering -- and celebrate this milestone. You reached your writing goals for today? Buy yourself a treat and/or your favorite latte and take a walk outside.

You may be tempted to capitalize on the adrenaline rush of completion or on being in the working/productive mind-set and try to tackle the next topic, but that is a recipe for burnout in the long run. Recognizing that you are progressing and getting closer to your main goal provides immediate reward and helps you envision your objective of completing a dissertation as feasible and attainable.

Why do you like it? If you got midway through your dissertation and are now feeling stuck, try focusing on the part of your project that you enjoy the most. That might be the close analysis of a particularly poignant passage or the application of a specific theory, method or approach to your data. If possible, see if you can start writing the chapter you are stuck on not from the beginning but from the portion that speaks to you the most.

Ask yourself: Which part of this study am I most looking forward to writing/dealing with? Then go there. The rest, the connective tissue between sections, will come. The goal is to get you going.

It can also be useful to just look at the beginning of your journey: Why did you choose this project? Focus on the reasons that got you interested in it in the first place. Remember the enthusiasm you felt when you started? The eagerness to jump right in? Tap in to that to motivate you to bring your project to the finish line.

Is More Debt Relief Imminent? A New Lawsuit Says Yes—and Aims to Stop It.

Seven Republican attorneys general have sued the Biden administration to stop its latest plan for loan forgiveness be

Share This Article

More from career advice.

How to Mitigate Bias and Hire the Best People

Patrick Arens shares an approach to reviewing candidates that helps you select those most suited to do the job rather

The Warning Signs of Academic Layoffs

Ryan Anderson advises on how to tell if your institution is gearing up for them and how you can prepare and protect y

Legislation Isn’t All That Negatively Impacts DEI Practitioners

Many experience incivility, bullying, belittling and a disregard for their views and feelings on their own campuses,

- Become a Member

- Sign up for Newsletters

- Learning & Assessment

- Diversity & Equity

- Career Development

- Labor & Unionization

- Shared Governance

- Academic Freedom

- Books & Publishing

- Financial Aid

- Residential Life

- Free Speech

- Physical & Mental Health

- Race & Ethnicity

- Sex & Gender

- Socioeconomics

- Traditional-Age

- Adult & Post-Traditional

- Teaching & Learning

- Artificial Intelligence

- Digital Publishing

- Data Analytics

- Administrative Tech

- Alternative Credentials

- Financial Health

- Cost-Cutting

- Revenue Strategies

- Academic Programs

- Physical Campuses

- Mergers & Collaboration

- Fundraising

- Research Universities

- Regional Public Universities

- Community Colleges

- Private Nonprofit Colleges

- Minority-Serving Institutions

- Religious Colleges

- Women's Colleges

- Specialized Colleges

- For-Profit Colleges

- Executive Leadership

- Trustees & Regents

- State Oversight

- Accreditation

- Politics & Elections

- Supreme Court

- Student Aid Policy

- Science & Research Policy

- State Policy

- Colleges & Localities

- Employee Satisfaction

- Remote & Flexible Work

- Staff Issues

- Study Abroad

- International Students in U.S.

- U.S. Colleges in the World

- Intellectual Affairs

- Seeking a Faculty Job

- Advancing in the Faculty

- Seeking an Administrative Job

- Advancing as an Administrator

- Beyond Transfer

- Call to Action

- Confessions of a Community College Dean

- Higher Ed Gamma

- Higher Ed Policy

- Just Explain It to Me!

- Just Visiting

- Law, Policy—and IT?

- Leadership & StratEDgy

- Leadership in Higher Education

- Learning Innovation

- Online: Trending Now

- Resident Scholar

- University of Venus

- Student Voice

- Academic Life

- Health & Wellness

- The College Experience

- Life After College

- Academic Minute

- Weekly Wisdom

- Reports & Data

- Quick Takes

- Advertising & Marketing

- Consulting Services

- Data & Insights

- Hiring & Jobs

- Event Partnerships

4 /5 Articles remaining this month.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

- Sign Up, It’s FREE

Nie den Fokus verlieren: Motivation für die Dissertation

Eine Dissertation ist der Gipfel einer akademischen Karriere. Der Weg zur Doktorwürde ist dabei vergleichbar mit einer herausfordernden Bergtour: Am Fuße des Berges blickt man zum Gipfel, der auf den ersten Blick unendlich weit entfernt scheint. Man fragt sich, ob es all die Anstrengungen, Zeit und Mühen wert ist, dorthin zu gelangen. Vielleicht beschleichen einen auch Zweifel, ob man es überhaupt wagen sollte, sich auf den beschwerlichen Weg zum Gipfel zu machen, ob die eigenen Fähigkeiten ausreichen.

Das Ziel der Dissertation fokussieren

Meilensteine zur motivation festlegen, etappensiege feiern als motivationshilfe, effektive arbeitszeiten verbindlich festlegen, kontinuierlich schreiben, die balance finden.

Wer gleich losrennt, wird am Ende seiner Kräfte sein, bevor er auch nur in die Nähe des Gipfels kommt. Wer hingegen in seinem eigenen Tempo Schritt für Schritt den Berg besteigt, sich Etappenziele setzt und deren Erreichen feiert, hat gute Chancen, es zu schaffen. Dabei gilt es, den Blick sowohl auf das Ziel als auch auf die bereits erfolgreich bewältigte Wegstrecke zu richten.

Dieser Beitrag liefert eine Motivationshilfe zur Dissertation und zeigt auf, wie man erfolgreich den Gipfel der akademischen Karriere erklimmt. Eine gut strukturierte Planung einer Dissertation ist dabei sehr hilfreich.

Die Basis der Motivation, eine Dissertation zu verfassen, ergibt sich aus dem Ziel, das man mit der Dissertation verfolgt. „Wenn man später in schwierige Phasen der Promotion gerät, ist es in der Regel das Wofür, das über Durchbeißen oder Abbrechen mitentscheidet.“ (Vuran/Seide, 2017).

Entscheidend ist dabei, mit sich selbst ehrlich zu sein und die wahren Beweggründe zu benennen. Persönliche Eitelkeit, der Wunsch, seinem Namen einen akademischen Titel hinzuzufügen, ist meist keine solide Grundlage für eine erfolgreiche Dissertation und keine gute Motivation. Der Wunsch, durch eine Doktorarbeit drohender Arbeitslosigkeit zu entgehen oder den Berufseinstieg zu verzögern, ist ebenfalls nicht der beste Grund. Dies betont unter anderem Jesse in seinen Zehn Anregungen für Doktoranden . Das Bedürfnis, selbst einen echten Mehrwert zur Forschung zu liefern, ist hingegen meist eine belastbares Motivation, die einen auf dem Weg zur Promotion tragen kann.

Diese grundsätzliche Motivation sollte man konkretisieren und verschriftlichen: „Ich leiste einen wichtigen Beitrag zur wissenschaftlichen Diskussion von XY.“, kann zum Beispiel ein solches verschriftlichtes Motiv sein. Diese Zielvorstellung sollte in großen Lettern den künftigen Arbeitsplatz zieren. So behält man sein wahres Ziel stets vor Augen.

Gleiches gilt für die Fragestellung der Dissertation. Auch sie gilt es auszuformulieren und dann gut lesbar am Schreibtisch, im Labor oder wo auch immer das Schreiben an der Doktorarbeit absolviert wird, zu platzieren. Diese Leitsätze, die zentrale Botschaft der Motivation sowie die Forschungsfrage, sind quasi das Gipfelkreuz, auf das man während des beschwerlichen Wegs der Promotion immer wieder den Blick richtet.

Hilfe für Deine Dissertation

- Lektorat Dissertation

- Formatierung

- Plagiatsprüfung

- Umschreiben

- Übersetzung

- Audio-Transkription

- Erstellung von Grafiken

- Drucken und Binden

Das Ziel der Doktorarbeit hat man nun klar und deutlich vor Augen – doch der Weg dorthin ist weit und führt nicht immer geradeaus. Daher ist es wichtig, bereits zu Beginn Meilensteine festzulegen und deren Erreichen zu feiern. Andernfalls bekommt man schnell den Eindruck, dass noch unendlich viel vor einem liegt und bekommt leicht Panik. Panik jedoch ist ein Killer für die Motivation und Leistung. Denn aufgrund biochemischer Vorgänge im Körper lähmen Stress und Angst die Kreativität und Leistungsfähigkeit, wie das Yerkes-Dodson-Gesetz beschreibt (Krengel, 2013). Das kann sogar zu einer Schreibblockade führen.

Diesem Stress kann man entgegenwirken, wenn man realistische Zwischenziele anvisiert und sich gleichzeitig für das Erreichen von Zwischenzielen angemessen belohnt. Dabei kann es als Hilfe für die Motivation nützlich sein, diese Ziele ebenso wie die Leitsätze zur Dissertation zu visualisieren, so dass sie einem beim Dissertation Schreiben stets vor Augen sind. Auf diese Weise wird zudem sichergestellt, dass der rote Faden der Forschungsarbeit nicht verloren geht. Der Weg zum Ziel bekommt Struktur, so dass man sich während der oft jahrelangen Auseinandersetzung mit der Forschungsfrage nicht verzettelt.

Das Festlegen realistischer Ziele hat einen wichtigen psychologischen Effekt, denn Motivation entsteht unter anderem aus Erfolgserlebnissen. Einzelne Punkte auf einer To do-Liste abhaken zu können, gibt ein positives Gefühl und gleichzeitig einen Schub für die eigene Motivation, die nächste Aufgabe anzugehen. Wenn man also Aufgaben wie „ Übersetzung von xy anfertigen“ oder „ Audio-Transkription verschriftlichen“, oder am Ende „ Layout “ oder „ Plagiatsprüfung “ auf einer langen Liste abhaken kann, schenkt man sich selbst Glückshormone.

Dazu kann es hilfreich sein, die erreichten Ziele anderen Menschen zu präsentieren – etwa im Rahmen von Arbeitsgruppen. Oder man führt ein persönliches Dissertationstagebuch, in dem jeden Tag stichwortartig der eigene Fortschritt festgehalten wird.

Beides führt dazu, die gewählten Pfade immer wieder kritisch zu hinterfragen. Führt dieser Weg wirklich zum Ziel? Oder ist das ein unnötiger Umweg, vielleicht sogar eine Sackgasse? Auch dazu ist ein Austausch anlässlich erreichter Ziele sowohl mit dem Betreuer als auch mit anderen Doktoranden geeignet. Besser frühzeitig einen Irrweg als solchen entlarven und umkehren, als stur einem einmal eingeschlagenen Weg folgen und deswegen wertvolle Zeit und Kraft verlieren.

Das richtige Arbeitsumfeld für die Dissertation schaffen

Für den richtigen Fokus sorgen nicht nur die Plakate zum Promotionsziel, zur zentralen Forschungsfrage sowie zu den anvisierten Meilensteinen. Darüber hinaus sollte der Arbeitsplatz, an dem die Hauptarbeit an der Dissertation geleistet wird, ein Rückzugsort sein, an dem Ruhe und Ordnung herrschen. Es ist wichtig, anhand äußerer Bedingungen klare Strukturen für den Arbeitsprozess zu schaffen. Ganz praktisch bedeutet dies zum Beispiel, den Schreibtisch ordentlich zu halten oder nach getaner Arbeit aufzuräumen, so dass man am nächsten Tag nicht – wortwörtlich – vor einem Berg an Arbeit zurückschreckt.

Das könnte dich auch interessieren

- Promotion finanzieren

- Berufsbegleitend promovieren

- Promotion Perspektiven

- Promovieren Voraussetzungen

Lektorat für Fremdsprachen

- Französisch

- Italienisch

Die Promotion stellt höchste Anforderungen an die Selbstdisziplin und Selbstorganisation der Doktoranden. Oft ist es dabei hilfreich, mit sich selbst feste Arbeitszeiten und Termine zu vereinbaren und diese in einem gut sichtbar platzierten Kalender schriftlich festzuhalten. Auf diese Weise schafft man Verbindlichkeit und einen festen zeitlichen Rahmen. Es gilt die Faustformel: „Jedes Mal, wenn du eine Handlung aufschiebst, entfernst du dich ein Stück mehr davon.“ (Bücher, 2014)

Während der Arbeitszeit sollte man Ablenkungen durch Telefon, E-Mails, Apps vermeiden und sich ganz auf die Arbeit konzentrieren. Dazu wird empfohlen, eher kürzere, effektive Arbeitsphasen einzuplanen.

Der Prozess der Promotion ist ein Marathon, kein Sprint. Dementsprechend ist es wichtig, sich den Weg zum Ziel und die eigene Kraft realistisch einzuteilen und dabei auch immer wieder Freiräume einzuplanen, regelrecht Urlaub von der Dissertation zu machen. Bewegung an der frischen Luft, Sport, gemeinsame Zeit mit Familie und Freunden sind wichtige Motivations-Booster, die den Kopf frei machen und die Akkus wieder aufladen.

Doktorarbeiten sind zu umfangreich, als dass man quasi wie beim Fazit Schreiben die eigene Forschung herunterschreiben könnte, nachdem man alle Erkenntnisse zusammengetragen hat. Vielmehr sollte das Schreiben Teil des Forschungsprozesses sein. Daher sollte man möglichst früh mit der Verschriftlichung der eigenen Forschungsergebnisse beginnen und den Prozess des Schreibens kontinuierlich fortführen. So vermeidet man, sich eines Tages einer riesigen Materialsammlung gegenüberzusehen, die dann in ihrer Fülle so gar nicht mehr aufs Papier zu bringen ist. Dazu kommen die Organisationsprobleme mit dem Material und den eigenen Notizen. Auf diese Art und Weise kommt es schnell zu Schusseligkeiten. Schließlich muss man eine Plagiatsprüfung machen, um wieder Sicherheit zurückzuerlangen. Darüber hinaus ist es auch eine große Motivationshilfe zu sehen, dass die eigene Doktorarbeit wächst und gedeiht, und wieder: dass man seinem Ziel Schritt für Schritt – Seite für Seite – näherkommt.

Wunderbar, wenn man sich mit großem Forschungseifer auf das Abenteuer Dissertation einlässt. Bei allem Ehrgeiz und Fleiß ist es jedoch wichtig, die eigenen Kräfte richtig einzuschätzen und sich nicht zu überfordern. Dabei ist die Rückbesinnung auf den visualisierten roten Faden eine große Hilfe. Ansonsten gerät man schnell in einen Strudel aus immer weiter und weiter führenden Gedanken, der einen vom richtigen Weg abbringen.

Professor Wolfgang Leidhold von der Universität zu Köln nennt dies das „Drama der Peripherie des Wissens“. Er stellt sich das eigene Wissen als eine Kugel vor. Je mehr die eigene Wissenskugel an Umfang gewinnt, desto größer ist ihre Außenfläche. Sprich: Je mehr Wissen man hat, desto mehr Kontakt hat man auch zu dem, das man (noch) nicht weiß. Dies impliziert die Versuchung, die eigene Wissenskugel immer weiter auszudehnen – und auf diese Weise letztlich nie wirklich mit der Dissertation fertig zu werden. Es gilt also, sich bewusst auf einen sinnvollen Umfang zu beschränken, der akademischen Ansprüchen genügt und gleichzeitig in einem angemessenen Zeitraum als Doktorarbeit zu bewältigen ist. das bedeutet dann aber auch, das eine oder andere Buch nur zu überfliegen und nicht zu lesen.

Wer eine Promotion anstrebt, hat eine anstrengende, entbehrungsreiche Zeit vor sich. Denn wer den Gipfel erklimmen will, muss sich bergauf kämpfen. Hinfallen, wieder aufstehen, Rückschritte und Irrwege verkraften – das gehört dazu. Selbst wenn man fokussiert und strukturiert arbeitet und Motivationsfallen vermeidet, bleibt die Zeit der Promotion eine schwierige Lebensphase. Es geht also nicht nur darum, sich auf dem akademischen Fachgebiet weiterzuentwickeln, sondern auch darum, an dieser Herausforderung persönlich zu wachsen: eigene Strategien zu entwickeln, mit Frust und Unlust umzugehen und Versagensängste zu überwinden.

Dein Job im Bereich Textservices

- Transkriptor

Dein Job im Bereich Statistik & Mathe

- Statistik Dozent & Tutor

- Mathematik Dozent & Tutor

- Statistiker

Bücher, Norman (2014) : Abenteuer Motivation: Lebensimpulse des Extremläufers Norman Bücher, Berlin.

Krengel, Martin (2013) : Golden Rules: Erfolgreich Lernen und Arbeiten, 4. Auflage Lauchhammer.

Vuran, Atilla/Seide, Gunnar (2017) : Promovieren heißt scheitern, Offenbach.

Weiterführende Literatur:

Bauer, Kristin (2017) : Kleines Handbuch zum erfolgreichen Verfassen und Vollenden einer Dissertation, Hamburg.

Glatthorn, Allan A./Joyner, Randy L. (2013) : Writing the Winning Thesis Or Dissertation: A Step-by-Step Guide, 3rd Edition, Thousand Oaks.

Martens, Jens-Uwe/Kuhl, Julius (2013) : Die Kunst der Selbstmotivierung: Neue Erkenntnisse der Motivationsforschung praktisch nutzen, Stuttgart.

Stock Seffen et.al. (Hrsg.) (2013) : Erfolgreich promovieren: Ein Ratgeber von Promovierten für Promovierende, 3. Auflage Berlin/Heidelberg.

In 6 Schritten Deine Dissertation schreiben

Deckblatt Dissertation | Hilfestellung + Hinweise

Eidesstattliche Erklärung Dissertation – eine ehrliche Ansage

- Danksagung Dissertation | Vorlagen zum Download

- Exposé Dissertation | Tipps für den perfekten Start

- Promotionsstellen finden

- Promotion Pharmazie

- Promotion: Betreuer wechseln?

- Promotion Informatik

- Promotion BWL

Marina Feidel

We Trust in Human Precision

20,000+ Professional Language Experts Ready to Help. Expertise in a variety of Niches.

API Solutions

- API Pricing

- Cost estimate

- Customer loyalty program

- Educational Discount

- Non-Profit Discount

- Green Initiative Discount1

Value-Driven Pricing

Unmatched expertise at affordable rates tailored for your needs. Our services empower you to boost your productivity.

- Special Discounts

- Enterprise transcription solutions

- Enterprise translation solutions

- Transcription/Caption API

- AI Transcription Proofreading API

Trusted by Global Leaders

GoTranscript is the chosen service for top media organizations, universities, and Fortune 50 companies.

GoTranscript

One of the Largest Online Transcription and Translation Agencies in the World. Founded in 2005.

Speaker 1: Hallo und herzlich willkommen zu einem weiteren G-Writers Video Tutorial. G-Writers ist eine akademische Agentur, die sich auf Coachings, Lektorate und die Unterstützung bei der Erstellung der wissenschaftlichen Texte spezialisiert und konkretisiert hat. Heute wollen wir uns mit dem Thema Dissertation beschäftigen. Ein Thema, mit dem sich sicherlich viele von Ihnen wahrscheinlich nur wenig oder vielleicht auch nur einmal im Leben beschäftigen werden. Nichtsdestotrotz eine ganz wichtige Thematik, wenn man sich mit einer Dissertation beschäftigt, weil es natürlich nicht etwas ist, was man gerade mal so in Anführungszeichen nebenher macht. Heute möchte ich Ihnen ein paar Tipps geben, wenn Sie eine Dissertation schreiben, wie Sie die Motivation beim Schreiben einer Dissertation nicht verlieren, weil eine Dissertation ist ein langwieriger und ein aufwendiger Prozess, der sich oftmals auch über mehrere Jahre hinweg strecken wird. Und gerade da ist es natürlich ganz, ganz wichtig, dass man dran bleibt am Thema, die Motivation nicht verliert, den roten Faden sozusagen nicht verliert, um am Ende auch zum Ziel zu kommen. Ein paar Tipps, wie Sie das am besten machen können, wenn Sie eine Dissertation schreiben. Das erste Punkt oder der erste wichtige Punkt ist, Sie sollten sich Klarheit über die Gründe verschaffen. Warum mache ich also überhaupt diese Dissertation? Was ist mein Ziel? Was möchte ich damit am Ende erreichen? Und wie immer im Leben ist es auch hier so, je konkreter, je klarer das Ziel ist, je leichter wird Ihnen auch die Erstellung der Dissertation fallen und je besser werden Sie sich auch selber motivieren können, wenn Sie am Ende ein klares Ziel haben. Das kann mit Sicherheit ein berufliches Ziel sein, ein Fortkommen, ein Weiterkommen im Beruf. Kann aber auch sein, dass man die Dissertation vielleicht, wenn man schon älter ist, nur in Anführungszeichen für sich schreibt oder um auch eine gewisse Reputation in der Wissenschaft und in der Forschung zu erhalten. Ganz egal, was es ist, diese Gründe, die sollten bei Ihnen klar sein und die sollten Sie sich auch immer gerne auch in visualisierter Form oder dergleichen immer wieder klar machen und sich immer wieder in den Kopf rufen. Dann haben Sie schon mal einen ganz wesentlichen Punkt erreicht, damit Sie die Motivation nicht verlieren werden. Ein zweiter wichtiger Punkt ist es, Meilensteine festlegen und feiern. Auch das ist jetzt mit Sicherheit nichts Neues und gilt mit Sicherheit nicht nur für eine Dissertation, gilt für viele Themen, wenn Sie im Leben unterwegs sind und Ziele verfolgen wollen. Aber gerade in einer Dissertation, Sie erarbeiten ja sowieso im Vorfeld einen Zeitplan und wenn Sie dann die Dissertation schreiben, dann ist es sicherlich ganz wichtig, sich an diesen Zeitplan zu halten, der auch nicht zu eng sein sollte, der auch entsprechende Lücken, entsprechenden Puffer haben sollte. Aber in diesem Zeitplan sollte es auch Meilensteine geben. Das könnten beispielsweise Fertigstellung von einzelnen Kapiteln, Fertigstellung von Forschungen, Fertigstellung von Befragungen oder auch Abstimmung, wir kommen gleich noch darauf zu sprechen, mit Ihrem Doktorvater sein. Und ganz bewusst dann auch ruhig mal diese bewussten Erfolge, diese bewussten Meilensteine dann auch feiern. Dann aber auch wieder aufhören zu feiern. Das heißt, hier sich dann auch erstmal vielleicht eine gewisse Ruhe nehmen für einige wenige Tage, vielleicht auch für ein, zwei Wochen. Aber und wir werden später noch auf den Punkt kommen, dann auch wieder anfangen zu schreiben, weiter zu schreiben, weil ein Meilenstein ist eben auch nur ein Meilenstein und heißt noch nicht, dass Sie am Ziel angekommen sind. Der dritte Punkt ist ein ganz, ganz wichtiger Punkt. Bauen Sie Vertrauen, bauen Sie ein Vertrauensverhältnis zu Ihrem Doktorvater auf und suchen Sie auch regelmäßig die Abstimmung mit Ihrem Doktorvater. Da geht es auch nicht nur darum, dass Sie jetzt irgendwelche fertigen Kapitel oder Teile von der Arbeit abliefern und er diese durchliest, sondern finden Sie einen regelmäßigen Kontakt, sprechen Sie mit ihm, tauschen Sie sich aus, zeigen Sie ihm auch, wie weit sind Sie, was sind vielleicht auch aktuelle Themenstellungen, aktuelle Fragestellungen, mit denen Sie sich gerade beschäftigen. Vielleicht gibt es auch ein, das eine oder andere Problem, das gerade bei Ihnen auftaucht, was man vielleicht mit ihm diskutieren kann. Kurzum, bleiben Sie mit Ihrem Doktorvater während der Erstellung der Doktorarbeit im Gespräch und bauen Sie ein vertrauensvolles Verhältnis mit ihm auf. Ganz, ganz wichtig, weil klar ist auch, je vertrauensvoller das Verhältnis ist, je näher Sie ihm auf die Erstellung der Doktorarbeit auch mitnehmen, je besser wird natürlich auch später eine Beurteilung stattfinden, weil dann erkennt die Doktorarbeit und er steigt im Prinzip nicht bei Null ein. Immer gefährlich ist es, wenn Sie eine Doktorarbeit quasi ohne Begleitung Ihres Doktorvaters schreiben, ihm am Ende die fertige Arbeit vorlegen und er sagt, nee, das war eigentlich nicht das, was ich mir vorgestellt habe, das sollte komplett in eine andere Richtung gehen. Das heißt hier, ganz wichtig, regelmäßige Abstimmungen und über diese Abstimmungen hinaus einfach auch immer wieder dieses Aufbau, dieser Aufbau eines Vertrauensverhältnisses. Schreiben und Pausen, ich habe es gerade eben schon mal ein bisschen angeschnitten, schreiben Sie regelmäßig. Eine Doktorarbeit hat ja auch einen gewissen Seitenumfang, hängt davon ab, in welchem medizinischen Bereich Sie beispielsweise unterwegs sind. Dort hat eine Doktorarbeit eher weniger Seitenzahlen, wenn Sie aber im betriebswirtschaftlichen Bereich unterwegs sind, dann können das schon mal auch 200, 300, 400, 500, 600 mit Anhängen dann auch mal bis zu 1.000 Seiten sein. Also von daher, Sie haben hier auch eine gewisse Menge einfach an Stoff, die es zu produzieren gilt und auch hier, wie immer im Leben, es ist wichtiger, es ist besser in kleinen Stücken, in kleinen Portionen zu arbeiten. Also hier auch mal vielleicht nur in Anführungszeichen wenige Seiten pro Tag oder pro Woche zu produzieren, als dass Sie große Pausen lassen, dann in Ihrem Zeitplan hinterherhinken und dann auf einmal wieder 20 oder 30 Seiten in einer Woche produzieren müssen. Deswegen dran bleiben, aber ganz bewusst auch wieder Pausen einbauen, sich regenerieren und dann weitermachen. Und legen Sie auch keinen Perfektionismus an den Tag. Ihre Doktorarbeit wird nie 100 Prozent, wird nie 1000 Prozent perfekt sein. Das heißt, wenn Sie ein Thema erforscht haben, wenn Sie der Meinung sind, Sie haben das ausreichend erforscht, machen Sie auch einen Haken dran. Sie werden wahrscheinlich immer, je mehr Sie lesen, noch neue Aspekte, neue Lücken an der einen oder anderen Stelle erkennen. Die können Sie dann vielleicht bei der Endkorrektur, am Endlektorat noch aufnehmen an der einen oder anderen Stelle, wo es sinnvoll scheint, das Ganze auch noch ergänzen. Aber begnügen Sie sich dann auch mit dem Stand, den Sie erreicht haben, wo Sie auch mit sich selber zufrieden sind und sagen können, das ist dann auch von meiner Seite aus eine ausreichende Erforschung, eine ausreichende Erhebung der Thematik. Sie sehen also, eine Dissertation, Schreiben durchaus ein herausforderndes Thema, ein herausforderndes Projekt, insbesondere deswegen, weil es sich eben über so lange Zeit, über so viele Jahre, über so einen großen Zeitraum eben auch hinweg streckt. Und gerade deswegen ist es eben wichtig, auch hier die Motivation zu behalten. Werden Sie sich klar über die Gründe, seien Sie sich klar über die Gründe, legen Sie Meilensteine fest und feiern diese. Haben Sie Vertrauen in Sie und im Dr. Vater, schreiben Sie und legen Sie auch entsprechende Pausen ein und zeigen Sie bitte keinen Perfektionismus. Wenn Sie diese Punkte berücksichtigen, dann werden Sie auch eine erfolgreiche Doktorarbeit schreiben können. Wenn Sie Unterstützung benötigen in diesem Thema, sei es jetzt bei einer Motivation, sei es jetzt aber auch bei einem Coaching, sei es auch im Sinne von Abstimmungen von einzelnen Kapiteln, vielleicht auch in der Unterstützung bei der Statistik, bei der Empirie, wie auch immer. In diesen Fällen lohnt es sich dann oftmals auch, externe Unterstützung zu nutzen. Hier ist G-Writers gerne Ihr Ansprechpartner. G-Writers kann Ihnen hier gerne Unterstützung liefern, externer Art, in all diesen genannten Fragestellungen. Von daher scheuen Sie sich auch nicht hier, die Begleitung in Anspruch zu nehmen. In diesem Sinne wünsche ich Ihnen viel Glück, viel Erfolg bei Ihrer Doktorarbeit und denken Sie an die Tipps, um die Motivation zu erhalten.

8 Most Effective Ways to Increase Motivation for Thesis Writing

Writing a master’s or doctoral thesis is a tough job, and many students struggle with writer’s block and putting off work. The journey requires not just skill and knowledge but a sustained motivation for thesis writing. Here are eight essential strategies to help you find and maintain your motivation to write your thesis throughout the thesis writing process.

Know why you lack motivation

It’s important to understand whether you’re just avoiding writing (procrastination) or if you genuinely don’t feel interested in it (lack of motivation). Procrastination is when you delay writing even though you want to finish it, while a lack of motivation for thesis writing is when you have no interest in writing at all. Knowing the difference helps you find the right solution. Remember, not feeling motivated doesn’t mean you can’t write; it just might be less enjoyable.

Recognize external vs. internal motivation

In the early stages of your academic journey, things like job prospects or recognition may motivate you to write your thesis. These are external motivators. Over time, they might become less effective. That’s why it’s important to develop internal motivators, like a real passion for your topic, curiosity, or wanting to make a difference in your field. Shifting to these internal motivators can keep you energized about your thesis writing for a longer period.

Develop a writing plan

As you regularly spend time on your thesis, you’ll start to overcome any initial resistance. Planning and thinking about your work will make the next steps easier. You might find yourself working more than 20 minutes some days. As you progress, plan for longer thesis writing periods and set goals for completing each chapter.

Don’t overwhelm yourself

Getting stuck is normal in thesis or dissertation writing. Don’t view these challenges as impossible obstacles. If you’re frustrated or unsure, take a break for a few days. Then, consult your advisor or a mentor to discuss your challenges and find ways to move forward effectively.

Work on your thesis daily

Try to spend 15-20 minutes daily on tasks related to your thesis or dissertation. This includes reading, researching, outlining, and other preparatory activities. You can fit these tasks into short breaks throughout your day, like waiting for appointments, during commutes, or even while cooking.

Understand that thesis writing motivation changes

Realize that thesis writing motivation isn’t always the same; it changes over time. Your drive to write will vary with different stages of your research and life changes. Knowing that motivation can go up and down helps you adapt. When you feel less motivated, focus on small, doable parts of your work instead of big, intimidating goals.

Recharge your motivation regularly

Just like you need to rest and eat well to keep your body energized, your motivation for thesis writing needs to be refreshed too. Do things that boost your mental and creative energy. This could be talking with colleagues, attending workshops, or engaging in hobbies that relax you. Stay aware of your motivation levels and take action to rejuvenate them. This way, you can avoid burnout and keep a consistent pace in your thesis work.

Keep encouraging yourself

Repeating encouraging phrases like “I will finish my thesis by year’s end” or “I’ll complete a lot of work this week” can really help. Saying these affirmations regularly can focus your energy and keep you on track with your thesis writing motivation .

Remember, the amount you write can vary each day. Some days you might write a lot, and other days less. The key is to keep writing, even if it’s just rough ideas or jumbled thoughts. Don’t let the need for perfection stop you. Listening to podcasts where researchers talk about their writing experiences can also be inspiring and motivate you in your writing journey.

Paperpal is an AI writing assistant that help academics write better, faster with real-time suggestions for in-depth language and grammar correction. Trained on millions of research manuscripts enhanced by professional academic editors, Paperpal delivers human precision at machine speed.

Try it for free or upgrade to Paperpal Prime , which unlocks unlimited access to premium features like academic translation, paraphrasing, contextual synonyms, consistency checks and more. It’s like always having a professional academic editor by your side! Go beyond limitations and experience the future of academic writing. Get Paperpal Prime now at just US$19 a month!

Related Reads:

How to make your thesis supervision work for you.

- 6 Tips for Post-Doc Researchers to Take Their Career to the Next Level

- How to Write a Conclusion for Research Papers (with Examples)

- Presenting Research Data Effectively Through Tables and Figures

CACTUS Joins Hands with Taylor & Francis to Simplify Editorial Process with a Pioneering AI Solution

You may also like, how to cite in apa format (7th edition):..., academic integrity vs academic dishonesty: types & examples, the ai revolution: authors’ role in upholding academic..., the future of academia: how ai tools are..., how to write your research paper in apa..., how to choose a dissertation topic, how to write a phd research proposal, how to write an academic paragraph (step-by-step guide), five things authors need to know when using..., 7 best referencing tools and citation management software....

Kostenlose Rechtschreibprüfung

Kostenlose plagiatsprüfung, korrektur deiner bachelorarbeit.

- Wissensdatenbank

- Aufbau und Gliederung

Wie finde ich eine gute Motivation für die Bachelorarbeit?

Veröffentlicht am 12. April 2017 von Luca Corrieri . Aktualisiert am 29. November 2021.

Scribbrs kostenlose Rechtschreibprüfung

Fehler kostenlos beheben

Inhaltsverzeichnis

Halte die motivation der bachelorarbeit einfach, 1. eine persönliche erfahrung, 2. ein aktuelles ereignis, 3. ein ereignis bei deiner firma, der nächste teil der einleitung deiner bachelorarbeit, häufig gestellte fragen.

Beschreibe deine Motivation in Bezug auf deine Problemstellung, indem du auf das eingehst, was dich zum Schreiben deiner Bachelorarbeit gebracht hat. Generell gibt es drei verschiedene Arten von Gründen:

- Eine persönliche Erfahrung , die zu dem Problem geführt hat

- Ein aktuelles Ereignis im Zusammenhang mit dem Problem

- Ein Ereignis bei der Firma , für die du das Problem untersuchst

Jede Art von Motivation für eine Bachelorarbeit – sie kann auch Aufhänger, Grund oder einfach Idee der Bachelorarbeit genannt werden – besteht insgesamt aus drei Teilen:

- Beginn : Er zieht die Aufmerksamkeit des Lesers durch die Schilderung des Ereignisses auf sich, das zu dem Problem geführt hat.

- Hintergrundinformationen (Herstellung des Kontexts) : Gehe tiefer auf das Ereignis ein, indem du mehr Informationen über es vermittelst und dabei auch den Rahmen deiner Forschung skizzierst.

- Brücke zur Problemstellung : Erläutere, inwiefern es sich hierbei um ein Problem handelt, und schlage somit die Brücke zur Problemstellung, die deiner Untersuchung zu Grunde liegt.

Die Motivation der Bachelorarbeit sollte kurz und knackig sein. Es ist nicht nötig, mehrere Anlässe zu nennen. Wähle den besten und schreibe ihn auf.

Ist deine Bachelorarbeit fehlerfrei?

Durchschnittlich enthält eine Bachelorarbeit 150 Fehler pro 1.000 Wörter .

Neugierig? Bewege den Regler von links nach rechts!

Zu deiner Korrektur

Wenn du eine eigene Erfahrung als Motivation der Bachelorarbeit beschreibst, solltest du sie erfrischend und anregend vortragen

| Abschnitt | Erklärung |

|---|---|

| Gib an, welche Erfahrung du machtest, nach der du irgendwo ein Fragezeichen vor dir gesehen hast. | |

| Beschreibe genau, was du hinterfragst. Gib Hintergrundinformationen. | |

| Führe aus, inwiefern es sich um ein Problem handelt, das du nun in deiner Bachelorarbeit wissenschaftlich untersuchst. |

Beispiel für eine Motivation der Bachelorarbeit aus eigener Erfahrung

Als ich im Mai auf einem Stuhl im Sommergarten saß, sah ich von einem Baum einen Apfel fallen. Dieses Ereignis brachte mich zu dem Thema ‚Fallen‘.

Als ich mich bei dem Versuch, das Phänomen zu definieren, tiefer mit dem ‚Fallen‘ beschäftigte, bemerkte ich, dass alle materiellen Dinge immer auf die Erde oder nach unten fallen.

Es war bis dahin noch nicht bekannt, was verursacht, dass alle materiellen Dinge immer auf die Erde fallen.

Wenn ein aktuelles Ereignis als Motivation deiner Bachelorarbeit diente, dann solltest du dieses Ereignis auch schildern, um deine Motivation zu verdeutlichen.

| Abschnitt | Erklärung |

|---|---|

| Beschreibe das Ereignis so klar wie möglich. Daten und Zahlen sind ein Plus! | |

| Gehe noch weiter auf das Ereignis ein, um die Situation gut zu skizzieren und dann in der Lage zu sein, eine Brücke zu deinem Problem zu bauen. Hier kannst du also den Rahmen deiner Untersuchung diskutieren. | |

| Baue eine Brücke zur Problemstellung. |

Beispiel für die Motivation der Bachelorarbeit durch ein aktuelles Ereignis

Am 7. September 2008 gewann die Finanzkrise mit der Verstaatlichung von Fannie Mae und Freddie Mac an Dynamik. Diese beiden Hypothekenbanken hatten zusammen einen Anteil von etwa der Hälfte am gesamten US-Hypothekenmarkt. Die steigenden Schulden in diesem Markt wurden eine Bedrohung für das Finanzsystem in der gesamten Welt. Viele Banken hatten verschiedene Finanzpositionen in unzähligen verschiedenen Finanzstrukturen, die auf einmal nichts wert waren. Das hatte die Ursache, dass viele Menschen in den USA wegen steigender Zinsen nicht mehr ihre Hypothek bezahlen konnten. Die Hypothekenblase kollabierte schließlich. Was folgte, war eine globale Bankenkrise. Dies führte dazu, dass viele Banken in Konkurs gingen und dass die Banken, die ‚too big to fail‘ waren, von den Regierungen unterstützt und verstaatlicht wurden.

Die gesamte Finanzkrise hatte nach IWF-Schätzungen bereits Ende 2009 8,4 Billionen Euro gekostet. Die Europäische Kommission schätzt, dass die verschiedenen Formen der finanziellen Unterstützung des europäischen Bankensektors bei etwa 16,5 % des europäischen BIP liegen. Dies hat die Debatte über die Frage befeuert, wie in Zukunft eine globale Finanzkrise verhindert werden könnte.

Seitdem sind bereits viele Vorschläge gemacht worden, von denen einige auch bereits umgesetzt worden sind. Obwohl also die globale Regulierung des Bankensektors in vollem Gange ist, wird zugleich deutlich, dass diese Regulierung nicht so einfach ist.

Die Kosten der Krise wurden von den Behörden und Bürger getragen, und der globale Trend ist, dass die Verursacher sie zurückzahlen sollen. Da das Bankensystem als Anstifter der globalen Wirtschaftskrise gesehen wird, wollen Regierungen diese Banken finanziell härter bestrafen. Dies hat auch eine Diskussion über die Einführung einer Bankensteuer eingeleitet.

Daher hat der Europäische Rat am Ende der Sitzung vom 17. Juni 2010, die anlässlich des G-20-Gipfels in Toronto stattfand, erklärt, dass die Europäische Union (EU) „[…] should lead efforts to set a global approach for introducing systems for levies and taxes on financial institutions with a view to maintaining a world-wide level playing field and will strongly defend this position with its G-20 partners. The introduction of a global financial transaction tax should be explored and developed further in that context.”

Der Europäische Rat ist daher der Auffassung, dass sie führend sein sollte bei der Suche nach einer globalen Lösung für die Einführung einer Bankensteuer. Nun wurde jedoch bald klar, dass eine Einigung auf globaler Ebene schwierig ist. Daher schlägt der Europäische Rat vor, zunächst eine europäische Lösung in Betracht zu ziehen.

Diese Arbeit beschäftigt sich mit der möglichen europäischen Bankensteuer.

Wenn du in deiner Bachelorarbeit ein Problem für ein Unternehmen untersucht hast, dann steht deine Motivation der Bachelorarbeit in Verbindung mit einem Ereignis, das einen Einfluss auf dieses Unternehmen hatte. Es kann sein, dass neue Möglichkeiten geschaffen worden sind, die die Firma nutzen möchte, oder dass es eine negative Entwicklung ist, sodass du prüfst, wie ein bestimmtes Problem gelöst werden könnte.

| Abschnitt | Erklärung |

|---|---|

| Besprich die Gründe, die dazu geführt haben, dass deine Firma dich darum gebeten hat, hier eine Untersuchung durchzuführen. | |

| Geh noch tiefer auf die Motivation ein, indem du Hintergrundinformationen gibst. So kannst du den Rahmen der Untersuchung beschreiben. | |

| Schlage nun eine Brücke zur Problemstellung, indem du erklärst, warum hier ein Problem für das Unternehmen vorliegt oder entstehen könnte. |

Beispiel für die Motivation der Bachelorarbeit durch ein Ereignis bei deiner Firma

Seit der Einführung des neuen Kundenmanagementsystems bei Unternehmen Y im November 2016 haben deutlich weniger Support-Mitarbeiter Freude an ihrer Arbeit.

So sind Mitarbeiter pro Monat um 15 % häufiger krank als im November 2016. Eine Umfrage, an der Mitarbeiter anonym teilnehmen konnten, zeigte, dass 6 der 17 Mitarbeiter hoffen, innerhalb eines Jahres einen neuen Job zu finden.

Dieser Rückgang der Zufriedenheit hat nicht nur negative Auswirkungen auf die Arbeitsumgebung, sondern auch auf den Umsatz. Es ist nicht klar, warum die Support-Mitarbeiter seit der Einführung des neuen Client-Management-Systems viel weniger zufrieden mit ihrer Arbeit sind.

Sobald du die Motivation verdeutlicht hast, gehst du an die Problemstellung der Bachelorarbeit. Diese beiden Komponenten sollten in der Einleitung logisch miteinander verbunden werden.

So schreibst du die Einleitung deiner Bachelorarbeit

Die Motivation gehört zu deiner Problemstellung.

Ja, die Motivation gehört in die Einleitung der Bachelorarbeit.

Mit dem Anlass oder der Motivation der Bachelorarbeit, die du schilderst, ermutigst du den Leser, deine Einleitung zu lesen, indem du bei ihm das Interesse an der Problemstellung (dem Thema der Arbeit) weckst.

In die Motivation deiner Bachelorarbeit gehören Informationen zu deiner Problemstellung, aus denen hervorgeht, was dich zum Schreiben deiner Bachelorarbeit gebracht hat. Generell gibt es drei verschiedene Arten von Gründen:

- Eine persönliche Erfahrung, die zu dem Problem geführt hat.

- Ein aktuelles Ereignis im Zusammenhang mit dem Problem.

- Ein Ereignis bei der Firma, für die du das Problem untersuchst.

Diesen Scribbr-Artikel zitieren

Wenn du diese Quelle zitieren möchtest, kannst du die Quellenangabe kopieren und einfügen oder auf die Schaltfläche „Diesen Artikel zitieren“ klicken, um die Quellenangabe automatisch zu unserem kostenlosen Zitier-Generator hinzuzufügen.

Corrieri, L. (2021, 29. November). Wie finde ich eine gute Motivation für die Bachelorarbeit?. Scribbr. Abgerufen am 3. September 2024, von https://www.scribbr.de/aufbau-und-gliederung/motivation-bachelorarbeit/

War dieser Artikel hilfreich?

Luca Corrieri

Luca hat seinen Master an der Universität von Amsterdam abgeschlossen und ist seit 2014 für den deutschen Markt von Scribbr verantwortlich. Mit seinen Kenntnissen im Online-Marketing hat er sich zum Ziel gesetzt, Studierende während der Abschlussphase online zu unterstützen.

Das hat anderen Studierenden noch gefallen

Eine hervorragende einleitung für eine bachelorarbeit schreiben, das richtige bachelorarbeit-thema finden: anleitung, der zeitplan für deine bachelorarbeit in 4 phasen mit excel vorlage, aus versehen plagiiert finde kostenlos heraus.

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Setting Goals & Staying Motivated

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

This vidcast talks about how to set goals and how to maintain motivation for long writing tasks. When setting goals for a writing project, it is important to think about goals for the entire project and also goals for specific writing times. These latter goals should be specific, measurable, and manageable within the time allotted for writing. The section on motivation shares ideas for boosting motivation over the course of a long writing project. The handouts on goal-setting and staying productive, as well as the scholarly writing inventory, complement the material in this vidcast and should be used in conjunction with it.

Note: Closed-captioning and a full transcript are available for this vidcast.

Handouts

Goal-Setting for your Personal Intensive Writing Experience (IWE) | [PDF]

This handout guides writers through the important process of goal-setting for the personal Intensive Writing Experience. Specifically, it talks about how to (1) formulate specific, measurable, and reasonable writing goals, (2) set an overall IWE goal, (3) break up the overall goal into smaller, daily goals, and (4) break up daily goals into smaller goals for individual writing sessions. Writers are prompted to clear their head of distracting thoughts before each writing session and, after each session, to debrief on their progress and recalibrate goals as needed.

Scholarly Writing Inventory (PDF)

This questionnaire helps writers identify and inventory their personal strengths and weaknesses as scholarly writers. Specifically, writers are prompted to answer questions pertaining to (1) the emotional/psychological aspects of writing, (2) writing routines, (3) research, (4) organization, (5) citation, (6) mechanics, (7) social support, and (8) access to help. By completing this questionnaire, scholarly writers will find themselves in a better position to build upon their strengths and address their weaknesses.

Stay ing Productive for Long Writing Tasks (PDF)

This resource offers some practical tips and tools to assist writers in staying productive for extended periods of time in the face of common challenges like procrastination. It discusses how the process of writing is more than putting words on a page and offers suggestions for addressing negative emotions towards writing, such as anxiety. The handout also lays out helpful methods for staying productive for long writing tasks: (1) time-based methods, (2) social-based methods, (3) output-based methods, (4) reward-based methods, and (5) mixed methods.

- Contributors

- Valuing Black Lives

- Black Issues in Philosophy

- Blog Announcements

- Climate Matters

- Genealogies of Philosophy

- Graduate Student Council (GSC)

- Graduate Student Reflection

- Into Philosophy

- Member Interviews

- On Congeniality

- Philosophy as a Way of Life

- Philosophy in the Contemporary World

- Precarity and Philosophy

- Recently Published Book Spotlight

- Starting Out in Philosophy

- Syllabus Showcase

- Teaching and Learning Video Series

- Undergraduate Philosophy Club

- Women in Philosophy

- Diversity and Inclusiveness

- Issues in Philosophy

- Public Philosophy

- Work/Life Balance

- Submissions

- Journal Surveys

- APA Connect

Dissertating Like a Distance Runner: Ten Tips for Finishing Your PhD

The above photo is of Sir Mo Farah running past Buckingham Palace into the home stretch of the London Marathon. I took the photo two days after my viva, in which I defended my PhD dissertation. Farah become a British hero when he and his training partner, Galen Rupp, won the gold and silver medals in the 10k at the London Olympic Games.

I had the honor of racing against Rupp at Nike’s Boarder Clash meet between the fastest high school distance runners in my home state of Washington and Rupp’s home state of Oregon. I’m happy to provide a link to the results and photos of our teenage selves since I beat Galen and Washington won the meet. (Note: In the results, ‘Owen’ is misspelled with the commonly added s , which I, as a fan of Jesse Owens, feel is an honor.) By the time we were running in college—Rupp for the University of Oregon and myself for the University of Washington—he was on an entirely different level. I never achieved anything close to the kind of running success Rupp has had. Yet, for most of us mortals, the real value in athletics is the character traits and principles that sports instill in us, and how those principles carry over to other aspects of life. Here I want to share ten principles that the sport of distance running teaches, which I found to be quite transferrable to writing my doctoral dissertation.

To provide some personal context, I began as a doctoral researcher at the University of Birmingham in 2014. At that time my grandparents, who helped my single father raise my sister and me, continued their ongoing struggle with my Grandfather’s Alzheimer’s. It was becoming increasingly apparent that they would benefit from having my wife and I nearby. So, in 2015 we moved to my hometown of Yakima, Washington. That fall I began a 2/2 teaching load at a small university on the Yakama Nation Reservation as I continued to write my dissertation. Since finishing my PhD four years ago, in 2018, I have published one book , five research articles , and two edited volume chapters related in various ways to my dissertation. As someone living in rural Eastern Washington, who is a first-gen college grad, I had to find ways to stay self-motivated and to keep chipping away at my academic work. I found the following principles that I learned through distance running very helpful.

(1) Establish community . There are various explanations, some of which border on superstitious, for why Kenyan distance runners have been so dominant. Yet one factor is certainly the running community great Kenyan distance runners benefit from at their elite training camps, as discussed in Train Hard, Win Easy: The Kenyan Way . Having a community that values distance running can compel each member of the community to pursue athletic excellence over a long period of time. The same can be said for academic work. Many doctoral researchers have built-in community in their university departments, but for various reasons this is not true for everyone. Thankfully, alternative ways to establish community have never been easier, predominantly due to technology.

Since my dissertation applied Aristotelian causation and neo-Thomistic hylomorphism to mental causation and neural correlates of consciousness, I found it immensely helpful to meet consistently with neuroscientist, Christof Koch, and philosopher of mind, Mihretu Guta. Mihretu does work on the philosophy of consciousness and Christof propelled the dawn of the neurobiology of consciousness with Francis Crick . Though Mihretu lives in Southern California, we met monthly through Skype, and I would drive over the Cascade Mountains once a month to meet with Christof in Seattle. As my dissertation examiner, Anna Marmodoro, once reminded me: the world is small—it’s easier than ever before to connect with other researchers.

It can also be helpful to keep in mind that your community can be large or small. As some athletes train in large camps consisting of many runners, others have small training groups, such as the three Ingebrigtsen brothers . Likewise, your community could be a whole philosophy department or several close friends. You can also mix it up. As an introvert, I enjoyed my relatively small consistent community, but I also benefitted from attending annual regional philosophy conferences where I could see the same folks each year. And I especially enjoyed developing relationships with other international researchers interested in Aristotelian philosophy of mind at a summer school hosted by the University of Oxford in Naples, which Marmodoro directed. For a brief period, we all stayed in a small villa and talked about hylomorphism all day, each day, while enjoying delicious Italian food.

Whatever your community looks like, whatever shape it takes, what matters is that you’re encouraged toward accomplishing your academic goal.

(2) Know your goal. Like writing a dissertation, becoming a good distance runner requires a lot of tedious and monotonous work. If you don’t have a clear goal of what you want to achieve, you won’t get up early, lace up your running shoes, and enter the frosty morning air as you take the first of many steps in your morning run. There are, after all, more enticing and perhaps even more pressing things to do. Similarly, if you don’t have a clear goal of when you want to finish your dissertation, it is easy to put off your daily writing for another day, which can easily become more distant into the future.

(3) Be realistic about your goal . While it is important to have a clear goal as a distance runner and as a doctoral researcher, it is important for your goal to be realistic. This means your goal should take into account the fact that you are human and therefore have both particular strengths and limitations. Everyone enters the sport of distance running with different strengths and weaknesses. When Diddy ran the city it would have been unrealistic for him to try to break the two-hour barrier in the marathon, as Eliud Kipchoge did . If Diddy made that his goal, he probably would have lost all hope in the first mile of the marathon and never finished. Because he set a more realistic goal of breaking four hours, not two hours, he paced himself accordingly and actually finished.

The parent of two young children who is teaching part-time can certainly finish a dissertation. But the parent will have a greater likelihood of doing so with a reasonable goal that fits that individual’s strengths and limitations. If the parent expects to finish on the same timescale as someone who is single with no children nor teaching responsibilities, this will likely lead to disappointment and less motivation in the middle of the process. Motivation will remain higher, and correspondingly so will productivity that is fueled by motivation, if one’s goal is realistic and achievable.

Another element of having a realistic goal is being willing to adapt the goal as your circumstances change. Sometimes a runner might enter a race expecting to place in the top five and midway through the race realize that she has a great chance of winning (consider, for example, Des Linden’s victory at the Boston Marathon ). At that point, it would be wise to revise one’s goal to be ‘win the race’ rather than simply placing in the top five. At other times, a runner might expect to win the race or be on the podium and midway realize that is no longer possible. Yet, if she is nevertheless within striking distance of placing in the top five, then she can make that her new goal, which is realistic given her current situation and will therefore sustain her motivation to the finish line. Sara Hall, who could have and wanted to crack the top three, held on for fifth at the World Championships marathon because she adjusted her goal midrace.

The PhD candidate who initially plans to finish her dissertation in three years but then finds herself in the midst of a pandemic or dealing with a medical issue or a family crisis may not need to give up on her goal of finishing her dissertation. Perhaps, she only needs to revise her goal so that it allows more time, so she finishes in five years rather than three. A PhD finished in five years is certainly more valuable than no PhD.

(4) Know why you want to achieve your goal . My high school cross-country coach, Mr. Steiner, once gave me a book about distance running entitled “Motivation is the Name of the Game.” It is one of those books you don’t really need to read because the main takeaway is in the title. Distance running requires much-delayed gratification—you must do many things that are not intrinsically enjoyable (such as running itself, ice baths, going to bed early, etc.) in order to achieve success. If you don’t have a solid reason for why you want to achieve your running goal, you won’t do the numerous things you do not want to do but must do to achieve your goal. The same is true for finishing a PhD. Therefore, it is important to know the reason(s) why you want to finish your dissertation and why you want a PhD.

As a side note, it can also be immensely helpful to choose a dissertation topic that you are personally very interested in, rather than a topic that will simply make you more employable. Of course, being employable is something many of us must consider. Yet, if you pick a topic that is so boring to you that you have significant difficulty finding the motivation to finish your dissertation, then picking an “employable dissertation topic” will be anything but employable.

(5) Prioritize your goal . “Be selfish” were the words of exhortation my college cross-country team heard from our coaches before we returned home for Christmas break. As someone who teaches ethics courses, I feel compelled to clarify that “be selfish” is not typically good advice. However, to be fair to my coaches, the realistic point they were trying to convey was that at home we would be surrounded by family and friends who may not fully understand our running goals and what it takes to accomplish them. For example, during my first Christmas break home from college, I was trying to run eighty miles per week. Because I was trying to fit these miles into my social schedule without much compromise, many of these miles were run in freezing temps, in the dark, on concrete sidewalks with streetlights, rather than dirt trails. After returning to campus following the holidays, I raced my first indoor track race with a terribly sore groin, which an MRI scan soon revealed was due to a stress fracture in my femur. I learned the hard way that I have limits to what I can do, which entails I must say “no thanks” to some invitations, even though that may appear selfish to some.

A PhD researcher writing a dissertation has a substantial goal before her. Yet, many people writing a dissertation have additional responsibilities, such as teaching, being a loving spouse, a faithful friend, or a present parent. As I was teaching while writing my dissertation, I often heard the mantra “put students first.” Yet, I knew if I prioritized my current students over and above finishing my dissertation, I would, like many, never finish my dissertation. However, I knew it would be best for my future students to be taught by an expert who has earned a PhD. So, I put my future students first by prioritizing finishing my PhD . This meant that I had to limit the teaching responsibilities I took on. Now, my current students are benefitting from my decision, as they are taught by an expert in my field.

While prioritizing your dissertation can mean putting it above some things in life, it also means putting it below other things. A friend once told me he would fail in a lot of areas in life before he fails as a father, which is often what it means to practically prioritize one goal above another. Prioritizing family and close friendships need not mean that you say ‘yes’ to every request, but that you intentionally build consistent time into your schedule to foster relationships with the people closest to you. For me, this practically meant not working past 6:00pm on weekdays and taking weekends off to hang out with family and friends. This relieved pressure, because I knew that if something went eschew with my plan to finish my PhD, I would still have the people in my life who I care most about. I could then work toward my goal without undue anxiety about the possibility of failing and the loss that would entail. I was positively motivated by the likely prospect that I would, in time, finish my PhD, and be able to celebrate it with others who supported me along the way.

(6) Just start writing . Yesterday morning, it was five degrees below freezing when I did my morning run. I wanted to skip my run and go straight to my heated office. So, I employed a veteran distance running trick to successfully finish my run. I went out the door and just started running. That is the hardest part, and once I do it, 99.9% of the time I finish my run.

You may not know what exactly you think about a specific topic in the chapter you need to write, nor what you are going to write each day. But perhaps the most simple and helpful dissertation advice I ever received was from David Horner, who earned his doctorate in philosophy from the University of Oxford. He told me: “just start writing.” Sometimes PhD researchers think they must have all their ideas solidified in their mind before they start writing their dissertation. In fact, writing your dissertation can actually help clarify what you think. So “just start writing” is not only simple but also sage advice.

(7) Never write a dissertation . No great marathoner focuses on running 26.2 miles. Great distance runners are masters of breaking up major goals into smaller goals and then focusing on accomplishing one small goal at a time, until they have achieved the major goal. Philosophers can understand this easily, as we take small, calculated steps through minor premises that support major premises to arrive at an overall conclusion in an argument.

Contained within each chapter of a dissertation is a premise(s) in an overall argument and individual sections can contain sub-premises supporting the major premise of each chapter. When you first start out as a doctoral researcher working on your dissertation, you have to construct an outline of your dissertation that maps out the various chapters and how they will relate to your overall conclusion. Once you have that outline in place, keep it in the back of your mind. But do not focus on writing the whole, which would be overwhelming and discouraging. Rather, focus on writing whichever chapter you are working on. The fastest American marathoner, Ryan Hall, wrote a book that sums up the only way to run long distances in the title Run the Mile You’re In . And Galen Rupp discusses in this interview how he mentally breaks up a marathon into segments and focuses on just finishing one segment at a time. Whatever chapter you’re writing, make it your goal to write that chapter. Once you’ve accomplished that goal, set a new goal: write the next chapter. Repeat that process several times and you will be halfway through your dissertation. Repeat the process a few more times, and you will be done.

By the time you have finished a master’s degree, you have written many chapter-length papers. To finish a dissertation, you essentially write about eight interconnected papers, one at a time, just as you have done many times before. If you just write the chapter (which you could call a “paper” if that feels like a lighter load) you’re writing, before you know it, you will have written a dissertation.

(8) Harness the power of habits . Becoming a great distance runner requires running an inordinate number of miles, which no one has the willpower to do. The best marathoners in the world regularly run well over one hundred miles a week, in addition to stretching, lifting weights, taking ice baths, and eating healthy. Not even the most tough-minded distance runner has the gumption to make all the individual decisions that would be required in order to get out the door for every run and climb into every ice bath apart from the development of habits. The most reliable way around each distance runner’s weakness of will, or akrasia , is developing and employing habits. The same can be true for writing.

If you simply try to write a little bit each weekday around the same time, you will develop a habit of writing at that time each day. Once you have that habit, the decision to write each weekday at that time will require less and less willpower over time. Eventually, it will take some willpower to not write at that time. I have found it helpful to develop the routine of freewriting for a few minutes just before starting my daily writing session of thirty minutes during which I write new content, before working on editing or revising existing content for about thirty minutes. My routine helped me develop the daily habit of writing, which removes the daily decision to write, as I “just do it” (to use Nike’s famous line) each day.

I have also found it helpful to divide my days up according to routines. As a morning person, I do well writing and researching in the morning, doing teaching prep and teaching during the middle of the day, and then doing mundane tasks such as email at the end of the day.

(9) Write for today and for tomorrow . Successful distance runners train for two reasons. One reason—to win upcoming races—is obvious. However, in addition to training for upcoming races, the successful distance runner trains today for the training that they want to be capable of months and years ahead. You cannot simply jump into running eighty, ninety, or one-hundred-mile weeks. It takes time to condition your body to sustain the stress of running high mileage weeks. A runner must have a long-term perspective and plan ahead as she works toward her immediate goals on the way to achieving her long-term goals. Similarly, for the PhD researcher, writing a dissertation lays the groundwork for future success.

For one, if the PhD candidate develops healthy, sustainable, productive habits while writing a dissertation, these habits can be continued once they land an academic job. It is no secret that the initial years on the job market, or in a new academic position, can be just as (or more) challenging than finishing a PhD. Effective habits developed while writing a dissertation can be invaluable during such seasons, allowing one to continue researching and writing even with more responsibilities and less time.

It is also worth noting that there is a sense in which research writing becomes easier, as one becomes accustomed to the work. A distance runner who has been running for decades, logging thousands of miles throughout their career, can run relatively fast without much effort. For example, my college roommate, Travis Boyd, decided to set the world record for running a half marathon pushing a baby stroller nearly a decade after we ran for the University of Washington. His training was no longer what it once was during our collegiate days. Nevertheless, his past training made it much easier for him to set the record, even though his focus had shifted to his full-time business career and being a present husband and father of two. I once asked my doctoral supervisors, Nikk Effingham and Jussi Suikkanen, how they were able to publish so much. They basically said it gets easier, as the work you have done in the past contributes to your future publications. Granted, not everyone is going to finish their PhD and then become a research super human like Liz Jackson , who finished her PhD in 2019, and published four articles that same year, three the next, and six the following year. Nevertheless, writing and publishing does become easier as you gain years of experience.

(10) Go running . As Cal Newport discusses in Deep Work , having solid boundaries around the time we work is conducive for highly effective academic work. And there is nothing more refreshing while dissertating than an athletic hobby with cognitive benefits . So, perhaps the best way to dissertate like a distance runner is to stop writing and go for a run.

Acknowledgments : Thanks are due to Aryn Owen and Jaden Anderson for their constructive feedback on a prior draft of this post.

- Matthew Owen

Matthew Owen (PhD, University of Birmingham) is a faculty member in the philosophy department at Yakima Valley College in Washington State. He is also an affiliate faculty member at the Center for Consciousness Science, University of Michigan. Matthew’s latest book is Measuring the Immeasurable Mind: Where Contemporary Neuroscience Meets the Aristotelian Tradition .

- Dissertating

- Finishing your PhD

- graduate students

- Sabrina D. MisirHiralall

RELATED ARTICLES

Indigenous philosophy, getty l. lustila, failure, camaraderie, and shared embodied learning, on divestiture, steven m. cahn, epistemic doubt: a dream we dreamed one afternoon long ago, how i got to questions, new series: ai and teaching, leave a reply cancel reply.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Notify me of follow-up comments by email.

Notify me of new posts by email.

WordPress Anti-Spam by WP-SpamShield

Currently you have JavaScript disabled. In order to post comments, please make sure JavaScript and Cookies are enabled, and reload the page. Click here for instructions on how to enable JavaScript in your browser.

Advanced search

Posts You May Enjoy

Is there a silver lining to algorithm bias pt. 1, mistaking good looks for goodness: yusuf dikeç and the halo effect, what we talk about when we talk about “personhood”: a critical..., the teaching workshop: preventing and coping with student disengagement, syllabus showcase: news & knowing, justin mcbrayer, on the political responsibilities of academics: an arendtian account.

How To Write A Dissertation Or Thesis

8 straightforward steps to craft an a-grade dissertation.

By: Derek Jansen (MBA) Expert Reviewed By: Dr Eunice Rautenbach | June 2020

Writing a dissertation or thesis is not a simple task. It takes time, energy and a lot of will power to get you across the finish line. It’s not easy – but it doesn’t necessarily need to be a painful process. If you understand the big-picture process of how to write a dissertation or thesis, your research journey will be a lot smoother.

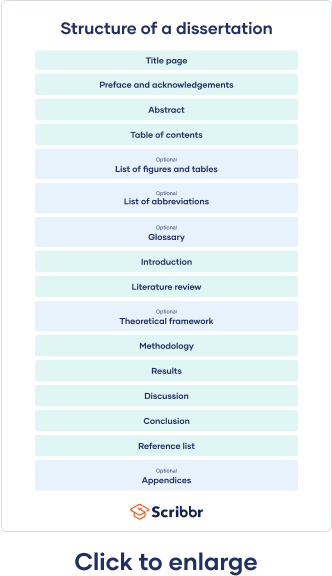

In this post, I’m going to outline the big-picture process of how to write a high-quality dissertation or thesis, without losing your mind along the way. If you’re just starting your research, this post is perfect for you. Alternatively, if you’ve already submitted your proposal, this article which covers how to structure a dissertation might be more helpful.

How To Write A Dissertation: 8 Steps

- Clearly understand what a dissertation (or thesis) is

- Find a unique and valuable research topic

- Craft a convincing research proposal

- Write up a strong introduction chapter

- Review the existing literature and compile a literature review

- Design a rigorous research strategy and undertake your own research

- Present the findings of your research

- Draw a conclusion and discuss the implications

Step 1: Understand exactly what a dissertation is

This probably sounds like a no-brainer, but all too often, students come to us for help with their research and the underlying issue is that they don’t fully understand what a dissertation (or thesis) actually is.

So, what is a dissertation?

At its simplest, a dissertation or thesis is a formal piece of research , reflecting the standard research process . But what is the standard research process, you ask? The research process involves 4 key steps:

- Ask a very specific, well-articulated question (s) (your research topic)

- See what other researchers have said about it (if they’ve already answered it)

- If they haven’t answered it adequately, undertake your own data collection and analysis in a scientifically rigorous fashion

- Answer your original question(s), based on your analysis findings

In short, the research process is simply about asking and answering questions in a systematic fashion . This probably sounds pretty obvious, but people often think they’ve done “research”, when in fact what they have done is:

- Started with a vague, poorly articulated question

- Not taken the time to see what research has already been done regarding the question

- Collected data and opinions that support their gut and undertaken a flimsy analysis

- Drawn a shaky conclusion, based on that analysis

If you want to see the perfect example of this in action, look out for the next Facebook post where someone claims they’ve done “research”… All too often, people consider reading a few blog posts to constitute research. Its no surprise then that what they end up with is an opinion piece, not research. Okay, okay – I’ll climb off my soapbox now.

The key takeaway here is that a dissertation (or thesis) is a formal piece of research, reflecting the research process. It’s not an opinion piece , nor a place to push your agenda or try to convince someone of your position. Writing a good dissertation involves asking a question and taking a systematic, rigorous approach to answering it.

If you understand this and are comfortable leaving your opinions or preconceived ideas at the door, you’re already off to a good start!

Step 2: Find a unique, valuable research topic

As we saw, the first step of the research process is to ask a specific, well-articulated question. In other words, you need to find a research topic that asks a specific question or set of questions (these are called research questions ). Sounds easy enough, right? All you’ve got to do is identify a question or two and you’ve got a winning research topic. Well, not quite…

A good dissertation or thesis topic has a few important attributes. Specifically, a solid research topic should be:

Let’s take a closer look at these:

Attribute #1: Clear

Your research topic needs to be crystal clear about what you’re planning to research, what you want to know, and within what context. There shouldn’t be any ambiguity or vagueness about what you’ll research.

Here’s an example of a clearly articulated research topic:

An analysis of consumer-based factors influencing organisational trust in British low-cost online equity brokerage firms.

As you can see in the example, its crystal clear what will be analysed (factors impacting organisational trust), amongst who (consumers) and in what context (British low-cost equity brokerage firms, based online).

Need a helping hand?

Attribute #2: Unique

Your research should be asking a question(s) that hasn’t been asked before, or that hasn’t been asked in a specific context (for example, in a specific country or industry).

For example, sticking organisational trust topic above, it’s quite likely that organisational trust factors in the UK have been investigated before, but the context (online low-cost equity brokerages) could make this research unique. Therefore, the context makes this research original.

One caveat when using context as the basis for originality – you need to have a good reason to suspect that your findings in this context might be different from the existing research – otherwise, there’s no reason to warrant researching it.

Attribute #3: Important