About the Journal

Journal of Popular Music Studies is the peer-reviewed, quarterly publication of the U.S. Branch of the International Association for the Study of Popular Music.

The journal’s purview encompasses all genres of music that have been dubbed popular in any geographic region. In addition to mainstream genres such as rock, hip hop, EDM, punk, or country, it explores popular forms ranging from broadsides to Broadway to Bollywood film music. It aims to present popular music scholarship from a variety of disciplinary perspectives, including history, sociology, musicology, ethnomusicology, cultural studies, and communication.

Learn more about Journal of Popular Music Studies here .

eISSN : 1533-1598

Published Quarterly – March, June, September, December

Impact Factor: 0.2

Co-Editors: K.E. Goldschmitt, Wellesley College and Elliott H. Powell, University of Minnesota

Music Subject Collection

UC Press is pleased to offer our complete list of music journals packaged together as a collection for the first time.

Read the latest posts about the Journal of Popular Music Studies on the UC Press blog.

"Uncharted Country" Special Issue Wins the American Musicological Society's Ruth A. Solie Award

“ Uncharted Country: New Voices and Perspectives in Country Music Studies ” (Vol. 32, Issue 2, June 2020), guest edited by Nadine Hubbs and Francesca T. Royster, won the AMS's 2021 Ruth A Solie Award for an outstanding collection of essays (in either a book or journal). Read the issue for free for a limited time.

Issue Alerts

Sign up to receive JPMS table of contents alerts as new issues publish.

Library Recommendation

Recommend JPMS to your library.

Affiliations

- Recent Content

- Browse Issues

- All Content

- Info for Authors

- Info for Librarians

- Editorial Team

- Online ISSN 1533-1598

- Copyright © 2024

Stay Informed

Disciplines.

- Ancient World

- Anthropology

- Communication

- Criminology & Criminal Justice

- Film & Media Studies

- Food & Wine

- Browse All Disciplines

- Browse All Courses

- Book Authors

- Booksellers

- Instructions

- Journal Authors

- Journal Editors

- Media & Journalists

- Planned Giving

About UC Press

- Press Releases

- Seasonal Catalog

- Acquisitions Editors

- Customer Service

- Exam/Desk Requests

- Media Inquiries

- Print-Disability

- Rights & Permissions

- UC Press Foundation

- © Copyright 2024 by the Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Privacy policy Accessibility

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 26 July 2012

Measuring the Evolution of Contemporary Western Popular Music

- Joan Serrà 1 ,

- Álvaro Corral 2 ,

- Marián Boguñá 3 ,

- Martín Haro 4 &

- Josep Ll. Arcos 1

Scientific Reports volume 2 , Article number: 521 ( 2012 ) Cite this article

101k Accesses

107 Citations

1054 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Applied physics

- Mathematics and computing

- Statistical physics, thermodynamics and nonlinear dynamics

Popular music is a key cultural expression that has captured listeners' attention for ages. Many of the structural regularities underlying musical discourse are yet to be discovered and, accordingly, their historical evolution remains formally unknown. Here we unveil a number of patterns and metrics characterizing the generic usage of primary musical facets such as pitch, timbre and loudness in contemporary western popular music. Many of these patterns and metrics have been consistently stable for a period of more than fifty years. However, we prove important changes or trends related to the restriction of pitch transitions, the homogenization of the timbral palette and the growing loudness levels. This suggests that our perception of the new would be rooted on these changing characteristics. Hence, an old tune could perfectly sound novel and fashionable, provided that it consisted of common harmonic progressions, changed the instrumentation and increased the average loudness.

Similar content being viewed by others

The diachronic development of Debussy’s musical style: a corpus study with Discrete Fourier Transform

Sabrina Laneve, Ludovica Schaerf, … Martin Rohrmeier

The pace of modern culture

Ben Lambert, Georgios Kontonatsios, … Armand M. Leroi

Statistical Evolutionary Laws in Music Styles

Eita Nakamura & Kunihiko Kaneko

Introduction

Isn't it always the same? This question could be easily posed while listening to the music of any mainstream radio station in a western country. Like language, music is a human universal involving perceptually discrete elements displaying organization 1 . Therefore, contemporary popular music may have a well-established set of underlying patterns and regularities 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , some of them potentially inherited from the classical tradition 5 , 6 , 7 . Yet, as an incomparable artistic product for conveying emotions 8 , music must incorporate variation over such patterns in order to play upon people's memories and expectations, making it attractive to listeners 3 , 4 , 5 . For the very same reasons, long-term variations of the underlying patterns may also occur across years 9 . Many of these aspects remain formally unknown or lack scientific evidence, specially the latter, which is very often neglected in music-related studies, from musicological analyses to technological applications. The study of patterns and long-term variations in popular music could shed new light on relevant issues concerning its organization, structure and dynamics 10 . More importantly, it addresses valuable questions for the basic understanding of music as one of the main expressions of contemporary culture: Can we identify some of the patterns behind music creation? Do musicians change them over the years? Can we spot differences between new and old music? Is there an ‘evolution’ of musical discourse?

Current technologies for music information processing 11 , 12 provide a unique opportunity to answer the above questions under objective, empirical and quantitative premises. Moreover, akin to recent advances in other cultural assets 13 , they allow for unprecedented large-scale analyses. One of the first publicly-available large-scale collections that has been analyzed by standard music processing technologies is the million song dataset 14 . Among others, the dataset includes the year annotations and audio descriptions of 464,411 distinct music recordings (from 1955 to 2010), which roughly corresponds to more than 1,200 days of continuous listening. Such recordings span a variety of popular genres, including rock, pop, hip hop, metal, or electronic. Explicit descriptions available in the dataset 15 cover three primary and complementary musical facets 2 : loudness, pitch and timbre. Loudness basically correlates with our perception of sound amplitude or volume (notice that we refer to the intrinsic loudness of a recording, not the loudness a listener could manipulate). Pitch roughly corresponds to the harmonic content of the piece, including its chords, melody and tonal arrangements. Timbre accounts for the sound color, texture, or tone quality and can be essentially associated with instrument types, recording techniques and some expressive performance resources. These three music descriptions can be obtained at the temporal resolution of the beat, which is perhaps the most relevant temporal unit in music, specially in western popular music 2 , 4 .

Here we study the music evolution under the aforementioned premises and large-scale resources. By exploiting tools and concepts from statistical physics and complex networks 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , we unveil a number of statistical patterns and metrics characterizing the general usage of pitch, timbre and loudness in contemporary western popular music. Many of these patterns and metrics remain consistently stable for a period of more than 50 years, which points towards a great degree of conventionalism in the creation and production of this type of music. Yet, we find three important trends in the evolution of musical discourse: the restriction of pitch sequences (with metrics showing less variety in pitch progressions), the homogenization of the timbral palette (with frequent timbres becoming more frequent) and growing average loudness levels (threatening a dynamic richness that has been conserved until today). This suggests that our perception of the new would be essentially rooted on identifying simpler pitch sequences, fashionable timbral mixtures and louder volumes. Hence, an old tune with slightly simpler chord progressions, new instrument sonorities that were in agreement with current tendencies and recorded with modern techniques that allowed for increased loudness levels could be easily perceived as novel, fashionable and groundbreaking.

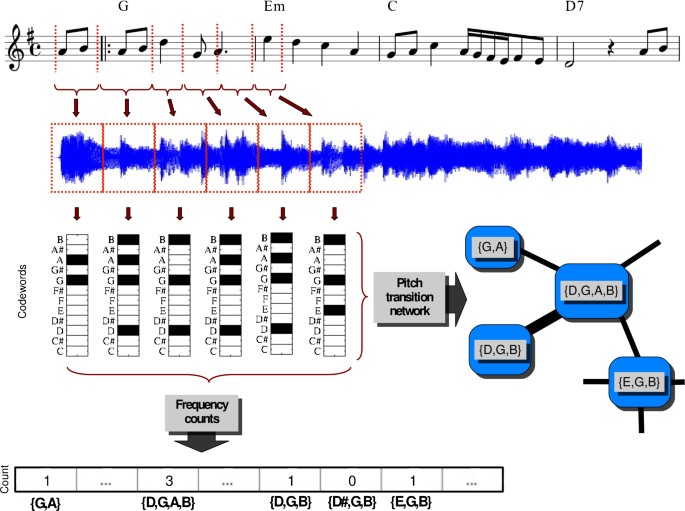

To identify structural patterns of musical discourse we first need to build a ‘vocabulary’ of musical elements ( Fig. 1 ). To do so, we encode the dataset descriptions by a discretization of their values, yielding what we call music codewords 20 (see Supplementary Information, SI ). In the case of pitch, the descriptions of each song are additionally transposed to an equivalent main tonality, such that all of them are automatically considered within the same tonal context or key. Next, to quantify long-term variations of a vocabulary, we need to obtain samples of it at different periods of time. For that we perform a Monte Carlo sampling in a moving window fashion. In particular, for each year, we sample one million beat-consecutive codewords, considering entire tracks and using a window length of 5 years (the window is centered at the corresponding year such that, for instance, for 1994 we sample one million consecutive beats by choosing full tracks whose year annotation is between 1992 and 1996, both included). This procedure, which is repeated 10 times, guarantees a representative sample with a smooth evolution over the years.

Method schematic summary with pitch data.

The dataset contains the beat-based music descriptions of the audio rendition of a musical piece or score (G, Em and D7 on the top of the staff denote chords). For pitch, these descriptions reflect the harmonic content of the piece 15 and encapsulate all sounding notes of a given time interval into a compact representation 11 , 12 , independently of their articulation (they consist of the 12 pitch class relative energies, where a pitch class is the set of all pitches that are a whole number of octaves apart, e.g. notes C1, C2 and C3 all collapse to pitch class C). All descriptions are encoded into music codewords, using a binary discretization in the case of pitch. Codewords are then used to perform frequency counts and as nodes of a complex network whose links reflect transitions between subsequent codewords.

We first count the frequency of usage of pitch codewords (i.e. the number of times each codeword type appears in a sample). We observe that most used pitch codewords generally correspond to well-known harmonic items 21 , while unused codewords correspond to strange/dissonant pitch combinations ( Fig. 2a ). Sorting the frequency counts in decreasing order provides a very clear pattern behind the data: a power law 17 of the form z ∝ r −α , where z corresponds to the frequency count of a codeword, r denotes its rank (i.e. r = 1 for the most used codeword and so forth) and α is the power law exponent. Specifically, we find that the distribution of codeword frequencies for a given year nicely fits to P ( z ) ∝ ( c + z ) −β for z > z min , where we take z as the random variable 22 , β = 1 + 1/α as the exponent and c as a constant ( Fig. 2b ). A power law indicates that a few codewords are very frequent while the majority are highly infrequent (intuitively, the latter provide the small musical nuances necessary to make a discourse attractive to listeners 3 , 4 , 5 ). Nonetheless, it also states that there is no characteristic frequency nor rank separating most used codewords from largely unused ones (except for the largest rank values due to the finiteness of the vocabulary). Another non-trivial consequence of power-law behavior is that when α ≤ 2, extreme events (i.e. very rare codewords) will certainly show up in a continuous discourse providing the listening time is sufficient and the pre-arranged dictionary of musical elements is big enough.

Pitch distributions and networks.

Importantly, we find this power-law behavior to be invariant across years, with practically the same fit parameters. In particular, the exponent β remains close to an average of 2.18 ± 0.06 (corresponding to α around 0.85), which is similar to Zipf's law in linguistic text corpora 23 and contrasts with the exponents found in previous small-scale, symbolic-based music studies 24 , 25 . The slope of the least squares linear regression of β as a function of the year is negligible within statistical significance ( p > 0.05, t-test). This makes a high stability of the distribution of pitch codeword frequencies across more than 50 years of music evident. However, it could well be that, even though the distribution is the same for all years, codeword rankings were changing (e.g. a certain codeword was used frequently in 1963 but became mostly unused by 2005). To assess this possibility we compute the Spearman's rank correlation coefficients 26 for all possible year pairs and find that they are all extremely high, with an average of 0.97 ± 0.02 and a minimum above 0.91. These high correlations indicate that codeword rankings practically do not vary with years.

Codeword frequency distributions provide a generic picture of vocabulary usage. However, they do not account for discourse syntax, as well as a simple selection of words does not necessarily constitute an intelligible sentence. One way to account for syntax is to look at local interactions or transitions between codewords, which define explicit relations that capture most of the underlying regularities of the discourse and that can be directly mapped into a network or graph 18 , 19 . Hence, analogously to language-based analyses 27 , 28 , 29 , we consider the transition networks formed by codeword successions, where each node represents a codeword and each link represents a transition (see SI ). The topology of these networks and common metrics extracted from them can provide us with valuable clues about the evolution of musical discourse.

All the transition networks we obtain are sparse, meaning that the number of links connecting codewords is of the same order of magnitude as the number of codewords. Thus, in general, only a limited number of transitions between codewords is possible. Such constraints would allow for music recognition and enjoyment, since these capacities are grounded in our ability for guessing/learning transitions 3 , 4 , 8 and a non-sparse network would increase the number of possibilities in a way that guessing/learning would become unfeasible. Thinking in terms of originality and creativity, a sparse network means that there are still many ‘composition paths’ to be discovered. However, some of these paths could run into the aforementioned guessing/learning tradeoff 9 . Overall, network sparseness provides a quantitative account of music's delicate balance between predictability and surprise.

In sparse networks, the most fundamental characteristic of a codeword is its degree k , which measures the number of links to other codewords. With pitch networks, this quantity is distributed according to a power law P ( k ) ∝ k −γ for k > k min , with the same fit parameters for all considered years. The exponent γ, which has an average of 2.20±0.06, is similar to many other real complex networks 18 and the median of the degree k is always 4. Nevertheless, we observe important trends in the other considered network metrics, namely the average shortest path length l , the clustering coefficient C and the assortativity with respect to random Γ. Specifically, l slightly increases from 2.9 to 3.2, values comparable to the ones obtained when randomizing the network links. The values of C show a considerable decrease from 0.65 to 0.45 and are much higher than those obtained for the randomized network. Thus, the small-worldness 30 of the networks decreases with years ( Fig. 2c ). This trend implies that the reachability of a pitch codeword becomes more difficult. The number of hops or steps to jump from one codeword to the other (as reflected by l ) tends to increase and, at the same time, the local connectivity of the network (as reflected by C ) tends to decrease. Additionally, Γ is always below 1, which indicates that the networks are always less assortative than random (i.e. well-connected nodes are less likely to be connected among them), a tendency that grows with time if we consider the biggest hubs of the network ( SI ). The latter suggests that there are less direct transitions between ‘referential’ or common codewords. Overall, a joint reduction of the small-worldness and the network assortativity shows a progressive restriction of pitch transitions, with less transition options and more defined paths between codewords.

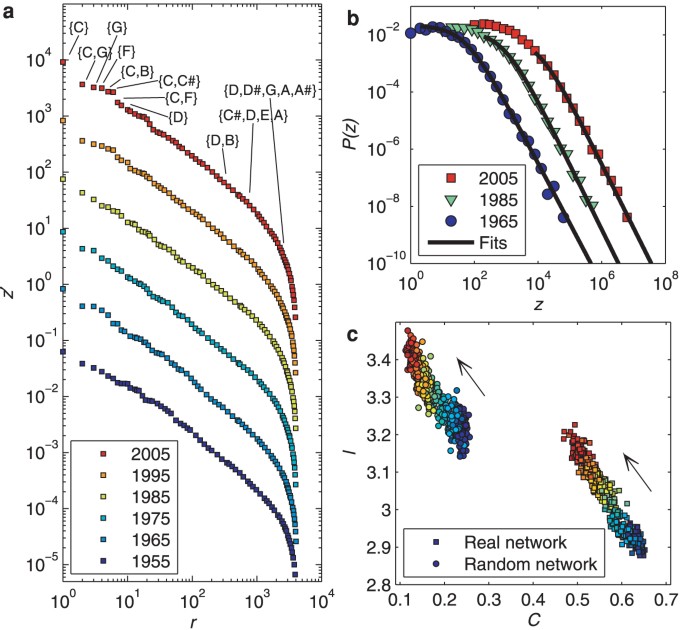

As opposed to pitch, timbre provides a different picture. Even though the distribution of timbre codeword frequencies is also well-fitted by a power law ( Fig. 3a ), the parameters of this distribution vary across years. In particular, since 1965, β constantly decreases to values approaching 4 ( Fig. 3b ). Although such large values of β would imply that other fits could also be acceptable, the power law provides a simple parameterization to compare the changes over the years (and is not rejected in a likelihood ratio test in front of other alternatives). Smaller values of β indicate less timbral variety: frequent codewords become more frequent and infrequent ones become even less frequent. This evidences a growing homogenization of the global timbral palette. It also points towards a progressive tendency to follow more fashionable, mainstream sonorities. Interestingly, rank correlation coefficients are generally below 0.7, with an average of 0.57 ± 0.15 ( Fig. 3c ). These rather low rank correlations would act as an attenuator of the sensation that contemporary popular music is becoming more homogeneous, timbrically speaking. The fact that frequent timbres of a certain time period become infrequent after some years could mask global homogeneity trends to listeners.

Timbre distributions.

(a) Examples of the density values and fits taking z as the random variable. (b) Fitted exponents β. (c) Spearman's rank correlation coefficients for all possible year pairs.

Compared to timbre codeword frequencies, metrics obtained from timbre transition networks show no substantial variation. Again, similar median degrees (all equal to 8) and degree distributions were observed for all considered years. However, we were not able to achieve a proper fit for the latter ( SI ). Values of Γ are larger than 1 and increasing since 1965. Thus, in contrast to pitch, timbre networks are more assortative than random. The values of l fluctuate around 4.8 and C is always below 0.01. Noticeably, both are close to the values obtained with randomly wired networks. This close to random topology quantitatively demonstrates that, as opposed to language, timbral contrasts (or transitions) are rarely the basis for a musical discourse 1 . This does not regard timbre as a meaningless facet. Global timbre properties, like the aforementioned power law and rankings, are clearly important for music categorization tasks 2 , 11 (one example is genre classification 31 ). Notice however that the evolving characteristics of musical discourse have important implications for artificial or human systems dealing with such tasks. For instance, the homogenization of the timbral palette and general timbral restrictions clearly challenge tasks exploiting this facet. A further example is found with the aforementioned restriction of pitch codeword connectivity, which could hinder song recognition systems (artificial song recognition systems are rooted on pitch codeword-like sequences, cf. 32 ).

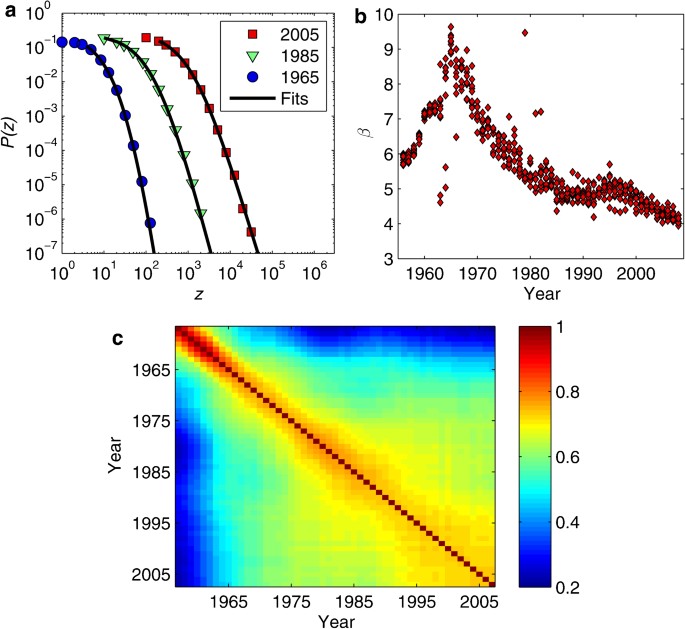

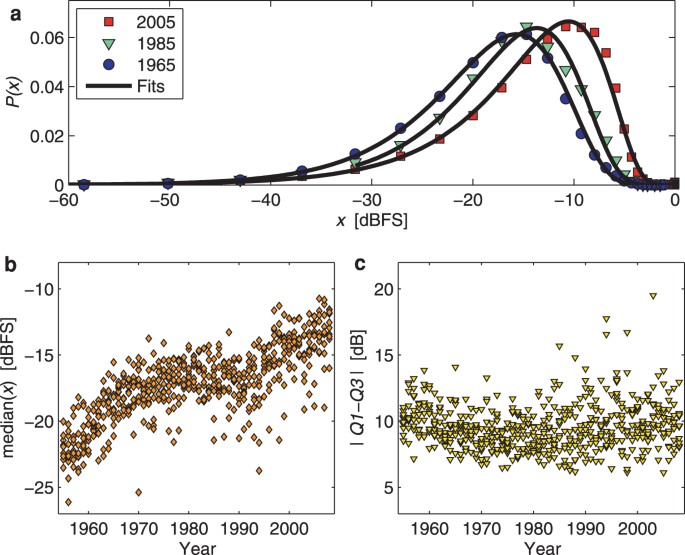

Loudness distributions are generally well-fitted by a reversed log-normal function ( Fig. 4a ). Plotting them provides a visual account of the so-called loudness race (or loudness war), a terminology that is used to describe the apparent competition to release recordings with increasing loudness 33 , 34 , perhaps with the aim of catching potential customers' attention in a music broadcast (from our point of view, loudness changes are not only the result of technological developments but, in part, also the result of conscious decisions made by musicians and producers in the musical creation process, cf. 33 ). The empiric median of the loudness values x grows from −22 dB FS to −13 dB FS ( Fig. 4b ), with a least squares linear regression yielding a slope of 0.13 dB/year ( p < 0.01, t-test). In contrast, the absolute difference between the first and third quartiles of x remains constant around 9.5 dB ( Fig. 4c ), with a regression slope that is not statistically significant ( p > 0.05, t-test). This shows that, although music recordings become louder, their absolute dynamic variability has been conserved, understanding dynamic variability as the range between higher and lower loudness passages of a recording 34 . However and perhaps most importantly, one should notice that digital media cannot output signals over 0 dB FS 35 , which severely restricts the possibilities for maintaining the dynamic variability if the median continues to grow.

Loudness distributions.

(a) Examples of the density values and fits of the loudness variable x . (b) Empiric distribution medians. (c) Dynamic variability, expressed as absolute loudness differences between the first and third quartiles of x , | Q 1 − Q 3 |.

Finally we look at loudness transition networks, which show comparable degree distributions, a median degree between 13 and 14, values of l between 8 and 10 and a Γ fluctuating around 1.08. Noticeably, l is appreciably beyond the values obtained by randomly wired networks. The values of C have an average of 0.59 ± 0.02, also much above the values obtained by the random networks. These two observations suggest that the network has a one-dimensional character, inferring that no extreme loudness transitions occur (one rarely finds loudness transitions to drive a musical discourse). The very stable metrics obtained for loudness networks imply that, despite the race towards louder music, the topology of loudness transitions is maintained.

Beyond the specific outcomes discussed above, we now focus on the evolution of musical discourse. Much of the gathered evidence points towards an important degree of conventionalism, in the sense of blockage or no-evolution, in the creation and production of contemporary western popular music. Thus, from a global perspective, popular music would have no clear trends and show no considerable changes in more than fifty years. Pitch codeword frequencies are found to be always under the same underlying pattern: a power law with the same exponent and fitting parameters. Moreover, frequency-based rankings of pitch codewords are practically identical and several of the network metrics for pitch, timbre and loudness remain immutable. Frequency distributions for timbre and loudness also fall under a universal pattern: a power law and a reversed log-normal distribution, respectively. However, these distributions' parameters do substantially change with years. In addition, some metrics for pitch networks clearly show a progression. Thus, beyond the global perspective, we observe a number of trends in the evolution of contemporary popular music. These point towards less variety in pitch transitions, towards a consistent homogenization of the timbral palette and towards louder and, in the end, potentially poorer volume dynamics.

Each of us has a perception of what is new and what is not in popular music. According to our findings, this perception should be largely rooted on the simplicity of pitch sequences, the usage of relatively novel timbral mixtures that are in agreement with the current tendencies and the exploitation of modern recording techniques that allow for louder volumes. This brings us to conjecture that an old popular music piece would be perceived as novel by essentially following these guidelines. In fact, it is informally known that a ‘safe’ way for contemporizing popular music tracks is to record a new version of an existing piece with current means, but without altering the main ‘semantics’ of the discourse.

Some of the conclusions reported here have historically remained as conjectures, based on restricted resources, or rather framed under subjective, qualitative and non-systematic premises. With the present work, we gain empirical evidence through a formal, quantitative and systematic analysis of a large-scale music collection. We encourage the development of further historical databases to be able to quantify the major transitions in the history of music and to start looking at more subtle evolving characteristics of particular genres or artists, without forgetting the whole wealth of cultures and music styles present in the world.

Detailed method descriptions are provided in the SI .

Patel, A. D. Music, language and the brain (Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK, 2007).

Ball, P. The music instinct: how music works and why we can't do without it (Bodley Head, London, UK, 2010).

Huron, D. Sweet anticipation: music and the psychology of expectation (MIT Press, Cambridge, USA, 2006).

Honing, H. Musical cognition: a science of listening (Transaction Publishers, Piscataway, USA, 2011).

Levitin, D. J., Chordia, P. & Menon, V. Musical rhythm spectra from Bach to Joplin obey a 1/f power law. Proc. of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA 109, 3716–3720 (2012).

Article CAS ADS Google Scholar

Lerdahl, F. & Jackendoff, R. A generative theory of tonal music (MIT Press, Cambridge, USA, 1983).

Temperley, D. Music and probability (MIT Press, Cambridge, USA, 2007).

Juslin, P. & Sloboda, J. A. Music and emotion: theory and research (Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK, 2001).

Reynolds, R. The evolution of sensibility. Nature 434, 316–319 (2005).

Zanette, D. H. Playing by numbers. Nature 453, 988–989 (2008).

Casey, M. A. et al. Content-based music information retrieval: current directions and future challenges. Proc. of the IEEE 96, 668–696 (2008).

Article Google Scholar

Müller, M., Ellis, D. P. W., Klapuri, A. & Richard, G. Signal processing for music analysis. IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Signal Processing 5, 1088–1110 (2011).

Article ADS Google Scholar

Michel, J.-B. et al. Quantitative analysis of culture using millions of digitized books. Science 331, 176–182 (2011).

Bertin-Mahieux, T., Ellis, D. P. W., Whitman, B. & Lamere, P. The million song dataset. In: Proc. of the Int. Soc. for Music Information Retrieval Conf. (ISMIR), 591–596 (2011).

Jehan, T. Creating music by listening. Ph.D. thesis, Massachussets Institute of Technology, Cambridge, USA (2005).

Bak, P. How nature works: the science of self-organized criticality (Copernicus, New York, USA, 1996).

Newman, M. E. J. Power laws, Pareto distributions and Zipf's law. Contemporary Physics 46, 323–351 (2005).

Newman, M. E. J. Networks: an introduction (Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK, 2010).

Barrat, A., Barthélemy, M. & Vespignani, A. Dynamical processes on complex networks (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, 2008).

Haro, M., Serrà, J., Herrera, P. & Corral, A. Zipf's law in short-time timbral codings of speech, music and environmental sound signals. PLoS ONE 7, e33993 (2012).

De Clercq, T. & Temperley, D. A corpus analysis of rock harmony. Popular Music 30, 47–70 (2011).

Adamic, L. A. & Huberman, B. A. Zipf's law and the internet. Glottometrics 3, 143–150 (2002).

Google Scholar

Zipf, G. K. Human behavior and the principle of least effort (Addison-Wesley, Boston, USA, 1949).

Zanette, D. Zipf's law and the creation of musical context. Musicae Scientiae 10, 3–18 (2006).

Beltrán del Río, M., Cocho, G. & Naumis, G. G. Universality in the tail of musical note rank distribution. Physica A 387, 5552–5560 (2008).

Hollander, M. & Wolfe, D. A. Nonparametric statistical methods (Wiley, New York, USA, 1999), 2nd edn.

Sigman, M. & Cecchi, G. A. Global organization of the Wordnet lexicon. Proc. of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA 99, 1742–1747 (2002).

Ferrer i Cancho, R., Solé, R. V. & Köhler, R. Patterns in syntactic dependency networks. Physical Review E 69, 051915 (2004).

Amancio, D. R., Altmann, E. G., Oliveira, O. N. & Costa, L. d. F. Comparing intermittency and network measurements of words and their dependence on authorship. New Journal of Physics 13, 123024 (2011).

Watts, D. J. & Strogatz, S. H. Collective dynamics of ‘small-world’ networks. Nature 393, 440–442 (1998).

Scaringella, N., Zoia, G. & Mlynek, D. Automatic genre classification of music content: a survey. Signal Processing Magazine 23, 133–141 (2006).

Serrà, J., Gómez, E. & Herrera, P. Audio cover song identification and similarity: background, approaches, evaluation and beyond. In Raś Z. W., & Wieczorkowska A. A., (eds.) Advances in Music Information Retrieval , vol. 274 of Studies in Computational Intelligence , chap. 14, 307–332 (Springer, Berlin, Germany, 2010).

Milner, G. Perfecting sound forever: an aural history of recorded music (Faber and Faber, London, UK, 2009).

Deruty, E. ‘Dynamic range’ and the loudness war. Sound on Sound – September 2011 22–24 (2011).

Oppenheim, A. V., Schafer, R. W. & Buck, J. R. Discrete-time signal processing (Prentice-Hall, Upper Saddle River, USA, 1999), 2nd edn.

Download references

Acknowledgements

This work was partially supported by Catalan Government grants 2009-SGR-164 (A.C.), 2009-SGR-1434 (J.S. and J.Ll.A.), 2009-SGR-838 (M.B.) and ICREA Academia Prize 2010 (M.B.), European Comission grant FP7-ICT-2011.1.5-287711 (M.H.), Spanish Government grants FIS2009-09508 (A.C.), FIS2010-21781-C02-02 (M.B.) and TIN2009-13692-C03-01 (J.Ll.A.) and Spanish National Research Council grant JAEDOC069/2010 (J.S.). The authors would like to thank the million song dataset team for making this massive source of data publicly available.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Artificial Intelligence Research Institute, Spanish National Research Council (IIIA-CSIC), Bellaterra, Barcelona, Spain

Joan Serrà & Josep Ll. Arcos

Complex Systems Group, Centre de Recerca Matemàtica, Bellaterra, Barcelona, Spain

- Álvaro Corral

Departament de Física Fonamental, Universitat de Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain

- Marián Boguñá

Music Technology Group, Universitat Pompeu Fabra, Barcelona, Spain

Martín Haro

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

J.S., A.C. and M.B. performed research. All authors designed research, discussed results and wrote the paper.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareALike 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Serrà, J., Corral, Á., Boguñá, M. et al. Measuring the Evolution of Contemporary Western Popular Music. Sci Rep 2 , 521 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep00521

Download citation

Received : 11 May 2012

Accepted : 04 July 2012

Published : 26 July 2012

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/srep00521

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

This article is cited by

Originality, influence, and success: a model of creative style.

- Karol Jan Borowiecki

- Caterina Adelaide Mauri

Journal of Cultural Economics (2023)

Magnetoencephalography recordings reveal the spatiotemporal dynamics of recognition memory for complex versus simple auditory sequences

- Gemma Fernández-Rubio

- Elvira Brattico

- Leonardo Bonetti

Communications Biology (2022)

Lognormals, power laws and double power laws in the distribution of frequencies of harmonic codewords from classical music

- Marc Serra-Peralta

Scientific Reports (2022)

- Ben Lambert

- Georgios Kontonatsios

- Armand M. Leroi

Nature Human Behaviour (2020)

Multiscale unfolding of real networks by geometric renormalization

- Guillermo García-Pérez

- M. Ángeles Serrano

Nature Physics (2018)

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines . If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

Ask Yale Library

My Library Accounts

Find, Request, and Use

Help and Research Support

Visit and Study

Explore Collections

Popular Music: Pop Music Research

- Pop Music Research

- Documentaries

- Journals and Books

- Finding scholarly articles

- Pop Music and Gender

- Pop Music Analysis

- Pop Music and The Law

- Archival Research

Pop Music News

- NPR's Fresh Air

- Red Bull Music Academy

- Dancecult bibliography and info related to electronic dance music

- Why is this music important?

- To whom is this music important?

- What kinds of ideological messages does this music communicate?

- What is striking about the way the music is organized?

Magazines at the Music Library

The following magazines can be browsed in the current periodicals section on the first floor of the Music Library. You may also use the link above to find online issues.

Electronic Musician

Journal of Popular Music Studies

Living Blues

Popular Music & Society

Rock Music Studies

Rolling Stone

- << Previous: Home

- Next: Reference >>

- Last Updated: Oct 24, 2023 1:20 PM

- URL: https://guides.library.yale.edu/popularmusic

Site Navigation

P.O. BOX 208240 New Haven, CT 06250-8240 (203) 432-1775

Yale's Libraries

Bass Library

Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library

Classics Library

Cushing/Whitney Medical Library

Divinity Library

East Asia Library

Gilmore Music Library

Haas Family Arts Library

Lewis Walpole Library

Lillian Goldman Law Library

Marx Science and Social Science Library

Sterling Memorial Library

Yale Center for British Art

SUBSCRIBE TO OUR NEWSLETTER

@YALELIBRARY

Yale Library Instagram

Accessibility Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Giving Privacy and Data Use Contact Our Web Team

© 2022 Yale University Library • All Rights Reserved

Popular Music Resources

Subject librarian.

Quick Introduction

MSPAL has a variety of resources to help you with your popular music research project, including databases, articles, books, CDs, and some unique primary sources.

Below, you will find a brief description of some of the tools that may be most helpful to you.

Online Resources

- Music Index Music Index is probably the best all-around source for finding journal and magazine articles on popular music. It covers both scholarly sources (e.g. the journal Popular Music) as well as popular glossy magazines (e.g. Rolling Stone). There are two caveats. Caveat #1 is that Music Index is not a fully full-text database. When searching Music Index, look for links to 'full-text" for the articles you want to read. If you do not see the full-text button, click the red Find It button to see if the UMD Libraries have it in another full-text repository or in paper--if we do not have the article in any form, you will be see with a link to request it through interlibrary loan. Caveat #2 is that the Music Index database only covers articles written in 1976 or more recently, which misses a lot of primary sources for the study of popular music history. If you are looking for articles written before 1976, try the print version of Music Index (going back to 1949), the RILM database (back to 1967), or a bibliography on popular music. For REALLY old stuff, like 19th century and early 20th century music, try RIPM.

- Entertainment Industry Magazine Archive Entertainment Industry Magazine Archive is a series of digital collections focused on 20th and 21st century genres such as Rock, Folk, and Hip-Hop & Rap. Researchers will find all material represented in the original publications, preserved in its original context, fully searchable and in high-resolution full color. The dates of coverage are1960-2016. There isn't a ton of material here but just about everything is interesting and there is some great primary source material.

- JSTOR JSTOR is a very large online repository of full-text scholarly journals. Its advantage for the study of popular music is that just about everything in JSTOR is high quality, all the articles you find will be immediately downloadable as PDFs, and the coverage is vast. One major downside is that due to licensing agreements, JSTOR doesn't typically have content from the most recent five years or so. For the most recent articles, try Music Index, RILM, or Google Scholar. Since JSTOR is such a large repository, one downside is you can easily get irrelevant search results (e.g., Lizzo--the Physical Chemist--will show up if you just search for "Lizzo"). You can get around this issue by adding more words to your search (Lizzo and (rap or music or flute)). Another good option is to click Browse and then drill down to a specific subject area (e.g. Arts>Music). Tip: popular music is quite interdisciplinary--you will find lots of good stuff not just in the Music category, but in many others as well. Particularly fruitful subjects to browse in JSTOR would be: History, Language & Literature, Performing Arts of course, and all the areas listed under Area Studies.

- RILM Music RILM is similar to Music Index in that it is mainly an index and not fully full-text. It uses the same interface as well. (Follow the advice under Music Index above for locating articles that are not available as full-text within RILM. RILM differs from Music Index in its coverage--RILM skews noticeably more scholarly and it doesn't cover all the popular magazines that Music Index does. RILM is also more international in scope. Finally, the online version of RILM goes back further (it has coverage back to 1967).

There are many discographies and guides to research in the reference section of MSPAL. Here are a few that may be especially useful:

Special Collections in Popular Music

You can find collections of rare or unique materials at Special Collections in the Performing Arts (SCPA) , located inside MSPAL. A few collections might be especially interesting to popular music researchers:

- The Keesing Collection on Popular Music and Culture "The Keesing Collection on Popular Music and Culture consists of books, serials, recordings, sheet music, clippings, memorabilia, and teaching and research materials related to twentieth-century American popular music, and to rock and roll music in particular. The materials were collected by Hugo Keesing, a popular culture scholar and former professor of American Studies at the University of Maryland, and by Dr. Keesing's brother, Wouter Keesing. The bulk of the collection covers the period from the 1950s to the 1990s. Serials in the collection include Rolling Stone, Pulse, Discoveries, Goldmine, and many other national and regional music serials. Research and teaching materials include Dr. Keesing's University of Maryland syllabi and class notes, writings, auction lists, catalogues, and price guides. In addition to the books housed with the archival collection, there are an additional 3,000 books that are can be found through the University of Maryland catalog. The collection is broad in its coverage of twentieth-century popular music; however, the collection originally contained a significant number of books, magazines, clippings, and memorabilia related to Elvis Presley, The Beatles, Roy Orbison, and Fats Domino, respectively. These materials have been organized into four separate collections; each collection has its own finding aid. Please note: While the majority of this collection has been processed, select series may not yet have complete inventories. Please contact the curator for more information."

- D.C. Punk and Indie Fanzine Collection "The Washington, D.C. Punk and Indie Fanzine Collection (DCPIFC) seeks to document the variety of publications that were created by fans of and participants in the punk and indie music scenes that have thrived in the Washington, D.C.-area since the late 1970s. The DCPIFC contains fanzines - publications produced by enthusiasts, generally in small runs - created by members of the D.C. punk and indie music communities, as well as fanzines from outside of D.C. that include coverage of D.C. punk and indie music. The collection includes primarily paper fanzines, but it also includes born digital fanzines and digitized files of some paper fanzine materials."

- Last Updated: Nov 29, 2023 1:33 PM

- URL: https://lib.guides.umd.edu/popmusic

Popular Music Criticism

- Journals and articles

- Reference and books

- Citing your sources

Key journals

- Billboard (in ProQuest Research Library)

- Journal of Popular Music Studies

- NME. New Musical Express (in LexisNexis Academic; selected full-text only)

- Popular Music

- Popular Music and Society

- Popular Music History

Online databases

General/Multidisciplinary

Specialized

to find specific document types (for example, an interview or a music review) select the appropriate document type from the menu in the search form, if applicable (see illustration below), or type it in the search box as one of the search terms, for example: Beyonce and interview "the chainsmokers" and "music review"

See also tips for searching the catalog .

Illustration: fragment of the Academic Search Complete search form with the "Document type" limit

- << Previous: Home

- Next: Reference and books >>

- Last Updated: Mar 11, 2024 12:02 PM

- URL: https://guides.libraries.uc.edu/popmusic

University of Cincinnati Libraries

PO Box 210033 Cincinnati, Ohio 45221-0033

Phone: 513-556-1424

Contact Us | Staff Directory

University of Cincinnati

Alerts | Clery and HEOA Notice | Notice of Non-Discrimination | eAccessibility Concern | Privacy Statement | Copyright Information

© 2021 University of Cincinnati

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Popular Music

- Most Cited Papers

- Most Downloaded Papers

- Newest Papers

- Save to Library

- Last »

- Popular Music Studies Follow Following

- Musicology Follow Following

- Ethnomusicology Follow Following

- Music Follow Following

- Popular Culture Follow Following

- Sociology of Music Follow Following

- Popular musicology Follow Following

- Cultural Musicology Follow Following

- Sound studies Follow Following

- Music and Politics Follow Following

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- Academia.edu Publishing

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

25 Most Popular Music Research Paper Topics for Writing

Research papers aren't just for history class or the social sciences. Research papers can be assigned in any course, and that includes music class. The world's musical traditions are fertile ground for research, but because we have been conditioned from childhood to think of music as entertainment rather than a subject for academic research, it is often difficult to come up with interesting and effective topics for a music research paper. Fortunately, music research papers are often more fun to write than other types of research paper because they have such a wide range of interesting topics to explore.

Choose from these stellar popular music research paper topics

Are you stuck looking for a music research topic? Well, you're in luck. We have twenty-five music research paper topics that will spark your creativity and get you started with your next paper. You can pick up one from this list, you can combine several of them, or maybe you will get inspired by this list and come with several topics on your own. In any case, make sure that the popular music topic for your research paper is interesting to you personally, and doesn't just sound potentially easy to write about.

1. How is music marketed by demographic? Explore the different ways music companies target various demographic groups such as age and gender. 2. How does the categorization of music affect consumer purchasing decisions? Examine how the emphasis on genre either enhances sales or limits consumer interest. 3. Does the album have a future in the streaming era? Consider whether the album can survive in an era when singles are streamed in customized playlists. 4. How has music changed over the past half century? Explore some of the major themes and developments that have shaped popular music since the dawn of the rock-n-roll era. 5. Research the most influential musicians of a specific era. By comparing and contrasting the careers of key figures from a particular era, you can pain a picture of a moment in time. 6. What makes music "classical"? How we define "classical" music says a lot about power and privilege. Explore who decides and what criteria get used. 7. Does music have an impact on our bodies? Research medical evidence whether music can impact human health. 8. Does music have an impact on our mental health? Examine research on the use of music for mental health and therapeutic purposes. 9. Music and children: Is the Mozart effect real? How can music education impact children's academic and social development? 10. Can music education aid in memory training and memory development? Consider the current academic research and evaluate the validity of claims for music as a memory aid. 11. How does music impact dance? Music and dance are inextricably linked. Look at some of the ways that music impacts the development of dance. 12. How does a musician become successful? Examine key routes to success and what a music student can do to set themselves up for a career. 13. What other careers does a music degree prepare a student for? Research how music degrees can set the stage for careers beyond the music industry. 14. How does music impact fashion? Look at how rock-n-roll and hip hop have shaped fashion trends. 15. How is music used in advertising? Look into the reasons that artists are licensing hit singles to sell products and how that impacts consumers' views of music. 16. Classical music vs. rock-n-roll: Which has been more influential? Examine the arguments for both sides and take a position. 17. Look into the sociology of tribute bands and consider the reasons that people would dedicate their lives to imitating other musicians. 18. It is often said that "music soothes the savage beast," and farmers often use music to calm livestock. Is there truth to the notion that music has a positive impact on animals? Explore the research and draw conclusions.

19. Music has been an important part of war throughout history, both martial music meant to rally the troops and anti-war songs. Examine the role of music in supporting and opposing war. 20. Music vs. poetry: Can song lyrics be considered a form of poetry? Why or why not? 21. How does hip-hop support African American culture and heritage? 22. Is there a problem with the close association of country music with political conservatism? 23. Select your favorite piece of music and research the influences that played a role in its creation and development. 24. Research the processes that archaeologists have used to reconstruct the sound of ancient music. 25. How do covers transform songs? Explore how covers are created now meaning.

After choosing the topic you like the most, save this list or this page to bookmarks for further references. It is good to have a library of resources at your fingertips.

Let experts rock when you are stuck

If these topics aren't enough to get you started, there is another trick to help you succeed. You can always find someone to help you with your research paper. You can contact a paper writing service online like WriteMyPaperHub and ask a professional essay writer, "Can I pay you to write my paper like an expert?" Once you do, a writer will determine what you need for your project and will begin writing a high-quality music research paper that will address your essay topic quickly, effectively, and with exceptional research and writing. You should feel free to take advantage of services like this whenever you get stuck so you can be successful with each and every music research paper.

Learning from the best and the brightest is more than beneficial. You have an opportunity to see how professional writers elaborate on a particular topic, which references they use, how they structure the whole thing. One ordered paper can be an example for your further works for months. Also, it is proven that students these days are overwhelmed with the number of assignments, and due to continuous lockdowns and limitations have less access to libraries and other necessary resources. If you feel like the pressure is too high, don't hesitate to delegate this assignment.

Kesha Updates 'Tik Tok' Lyric to 'F--- P. Diddy' During Surprise Coachella Performance with Reneé Rapp

CoacHella Good: No Doubt Triumph with One of the Festival's All-Time Greatest Reunions

Taylor Swift & Travis Kelce Kiss, Cuddle During Ice Spice’s Coachella ‘Karma’ Performance — While Ex-Scooter Braun Client Justin Bieber Looks On

Ladies First: Sabrina Carpenter, Chappell Roan, and Chlöe Slay Coachella 2024 Day 1

Coachella 2024 Friday Surprises: Suki Waterhouse's Baby Announcement, Becky G's Peso Pluma Reunion, and Shakira, Shakira!

Jimmy Buffett Would Befriend 'Lesbian Fisherwomen' By Saying He Knew Brandi Carlile

Diddy's Alleged Confession: Lil Rod Claims to Have Recording of Sean Combs Admitting to More Crimes

Justin Bieber Song with Lyrics ‘Lost Myself at a Diddy Party’ Viral on TikTok, Youtube: Is This Exposé Real?

Vanessa Williams Shows Off 'Legs' at 61 With New Dance Single

Kelly Clarkson Leaves This Singer 'Sobbing' After Out-Doing Him With Cover

'What's Happening?' Top 20 Reveal Might Be Weepiest Episode in 'American Idol' History

Machine Gun Kelly Banned From Coachella Since 2012: Is This the Real Reason?

We use cookies to give you the best experience possible. By continuing we’ll assume you’re on board with our cookie policy

- A Research Guide

- Research Paper Topics

120 Music Research Paper Topics

How to choose a topic for music research paper:.

Music Theory Research Paper Topics:

- The influence of harmonic progression on emotional response in music

- Analyzing the use of chromaticism in the compositions of Johann Sebastian Bach

- The role of rhythm and meter in creating musical tension and release

- Examining the development of tonality in Western classical music

- Exploring the impact of cultural and historical context on musical form and structure

- Investigating the use of polyphony in Renaissance choral music

- Analyzing the compositional techniques of minimalist music

- The relationship between melody and harmony in popular music

- Examining the influence of jazz improvisation on contemporary music

- The role of counterpoint in the compositions of Ludwig van Beethoven

- Investigating the use of microtonality in experimental music

- Analyzing the impact of technology on music composition and production

- The influence of musical modes on the development of different musical genres

- Exploring the use of musical symbolism in film scoring

- Investigating the role of music theory in the analysis and interpretation of non-Western music

Music Industry Research Paper Topics:

- The impact of streaming services on music consumption patterns

- The role of social media in promoting and marketing music

- The effects of piracy on the music industry

- The influence of technology on music production and distribution

- The relationship between music and mental health

- The evolution of music genres and their impact on the industry

- The economics of live music events and festivals

- The role of record labels in shaping the music industry

- The impact of globalization on the music industry

- The representation and portrayal of gender in the music industry

- The effects of music streaming platforms on artist revenue

- The role of music education in fostering talent and creativity

- The influence of music videos on audience perception and engagement

- The impact of music streaming on physical album sales

- The role of music in advertising and brand marketing

Music Therapy Research Paper Topics:

- The effectiveness of music therapy in reducing anxiety in cancer patients

- The impact of music therapy on improving cognitive function in individuals with Alzheimer’s disease

- Exploring the use of music therapy in managing chronic pain

- The role of music therapy in promoting emotional well-being in children with autism spectrum disorder

- Music therapy as a complementary treatment for depression: A systematic review

- The effects of music therapy on stress reduction in pregnant women

- Examining the benefits of music therapy in improving communication skills in individuals with developmental disabilities

- The use of music therapy in enhancing motor skills rehabilitation after stroke

- Music therapy interventions for improving sleep quality in patients with insomnia

- Exploring the impact of music therapy on reducing symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)

- The role of music therapy in improving social interaction and engagement in individuals with schizophrenia

- Music therapy as a non-pharmacological intervention for managing symptoms of dementia

- The effects of music therapy on pain perception and opioid use in hospitalized patients

- Exploring the use of music therapy in promoting relaxation and reducing anxiety during surgical procedures

- The impact of music therapy on improving quality of life in individuals with Parkinson’s disease

Music Psychology Research Paper Topics:

- The effects of music on mood and emotions

- The role of music in enhancing cognitive abilities

- The impact of music therapy on mental health disorders

- The relationship between music and memory recall

- The influence of music on stress reduction and relaxation

- The psychological effects of different genres of music

- The role of music in promoting social bonding and cohesion

- The effects of music on creativity and problem-solving abilities

- The psychological benefits of playing a musical instrument

- The impact of music on motivation and productivity

- The psychological effects of music on physical exercise performance

- The role of music in enhancing learning and academic performance

- The influence of music on sleep quality and patterns

- The psychological effects of music on individuals with autism spectrum disorder

- The relationship between music and personality traits

Music Education Research Paper Topics:

- The impact of music education on cognitive development in children

- The effectiveness of incorporating technology in music education

- The role of music education in promoting social and emotional development

- The benefits of music education for students with special needs

- The influence of music education on academic achievement

- The importance of music education in fostering creativity and innovation

- The relationship between music education and language development

- The impact of music education on self-esteem and self-confidence

- The role of music education in promoting cultural diversity and inclusivity

- The effects of music education on students’ overall well-being and mental health

- The significance of music education in developing critical thinking skills

- The role of music education in enhancing students’ teamwork and collaboration abilities

- The impact of music education on students’ motivation and engagement in school

- The effectiveness of different teaching methods in music education

- The relationship between music education and career opportunities in the music industry

Music History Research Paper Topics:

- The influence of African music on the development of jazz in the United States

- The role of women composers in classical music during the 18th century

- The impact of the Beatles on the evolution of popular music in the 1960s

- The cultural significance of hip-hop music in urban communities

- The development of opera in Italy during the Renaissance

- The influence of folk music on the protest movements of the 1960s

- The role of music in religious rituals and ceremonies throughout history

- The evolution of electronic music and its impact on contemporary music production

- The contribution of Latin American musicians to the development of salsa music

- The influence of classical music on film scores in the 20th century

- The role of music in the Civil Rights Movement in the United States

- The development of reggae music in Jamaica and its global impact

- The influence of Mozart’s compositions on the classical music era

- The role of music in the French Revolution and its impact on society

- The evolution of punk rock music and its influence on alternative music genres

Music Sociology Research Paper Topics:

- The impact of music streaming platforms on the music industry

- The role of music in shaping cultural identity

- Gender representation in popular music: A sociological analysis

- The influence of social media on music consumption patterns

- Music festivals as spaces for social interaction and community building

- The relationship between music and political activism

- The effects of globalization on local music scenes

- The role of music in constructing and challenging social norms

- The impact of technology on music production and distribution

- Music and social movements: A comparative study

- The role of music in promoting social change and social justice

- The influence of socioeconomic factors on music taste and preferences

- The role of music in constructing and reinforcing gender stereotypes

- The impact of music education on social and cognitive development

- The relationship between music and mental health: A sociological perspective

Classical Music Research Paper Topics:

- The influence of Ludwig van Beethoven on the development of classical music

- The role of women composers in classical music history

- The impact of Johann Sebastian Bach’s compositions on future generations

- The evolution of opera in the classical period

- The significance of Mozart’s symphonies in the classical era

- The influence of nationalism on classical music during the Romantic period

- The portrayal of emotions in classical music compositions

- The use of musical forms and structures in the works of Franz Joseph Haydn

- The impact of the Industrial Revolution on the production and dissemination of classical music

- The relationship between classical music and dance in the Baroque era

- The role of patronage in the development of classical music

- The influence of folk music on classical composers

- The representation of nature in classical music compositions

- The impact of technological advancements on classical music performance and recording

- The exploration of polyphony in the works of Johann Sebastian Bach

- Writing a Research Paper

- Research Paper Title

- Research Paper Sources

- Research Paper Problem Statement

- Research Paper Thesis Statement

- Hypothesis for a Research Paper

- Research Question

- Research Paper Outline

- Research Paper Summary

- Research Paper Prospectus

- Research Paper Proposal

- Research Paper Format

- Research Paper Styles

- AMA Style Research Paper

- MLA Style Research Paper

- Chicago Style Research Paper

- APA Style Research Paper

- Research Paper Structure

- Research Paper Cover Page

- Research Paper Abstract

- Research Paper Introduction

- Research Paper Body Paragraph

- Research Paper Literature Review

- Research Paper Background

- Research Paper Methods Section

- Research Paper Results Section

- Research Paper Discussion Section

- Research Paper Conclusion

- Research Paper Appendix

- Research Paper Bibliography

- APA Reference Page

- Annotated Bibliography

- Bibliography vs Works Cited vs References Page

- Research Paper Types

- What is Qualitative Research

Receive paper in 3 Hours!

- Choose the number of pages.

- Select your deadline.

- Complete your order.

Number of Pages

550 words (double spaced)

Deadline: 10 days left

By clicking "Log In", you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We'll occasionally send you account related and promo emails.

Sign Up for your FREE account

Forget about ChatGPT and get quality content right away.

What I’ve been up to lately

This blog will contain news, bits of writing about things I’m interested in, and occasional data science notes and tutorials.

Dr Craig Hamilton

I am currently working as a Data Fellowship Coach at Multiverse , helping to build an outstanding alternative to university and corporate training through professional apprenticeships. I work with individuals from a variety of organisations to help them develop and apply Data Analysis skills in their roles.

Prior to that I was a Research Fellow in the Birmingham Centre for Media and Cultural Research at Birmingham City University . My research explored contemporary popular music reception practices and the role of digital, data and internet technologies on the business and cultural environments of music consumption. In the main this research was built around the development of The Harkive Project , an online, crowd-sourced method of generating data from music consumers about their everyday relationships with music and technology. I was also the co-Managing Editor of Riffs: Experimental Writing on Popular Music , a member of the PEC-funded Live Music Research team, and the Project Coordinator for the AHRC-funded Songwriting Studies Network .

Outside of work, I continue to build on my 20+ years of working in the business of popular music, working as digital catalogue manager for Static Caravan Recordings and as a musician and recording artist with Independent Country .

I live in Birmingham, England, with my wife and sons and two unruly dogs, and when not working I enjoy collecting records, following Aston Villa, coaching kids football, and developing skills related to data science.

This website pulls together all of my personal and professional interests and projects. The views represented here are my own.

If you would like to discuss potential projects or collaborations around popular music, technology and data analytics, drop me a line

- Popular Music

- Digital Humanities

- Online Cultures

- Data Science

- Record Collecting

PhD Popular Music Studies, 2018

Birmingham City University

MA Music Industries, 2013

BA English Literature & Media and Cultural Studies, 1995

Middelsex University

Some of the things I write about

Click on the tags to explore my blog

Featured Publication

My most recently published article, book or chapter. Scroll down for a complete list of publications.

Exploring podcast review data via digital humanities methods

Publications

Some of my writing published in peer-reviewed academic journals and edited collections, plus project reports and other pieces published elsewhere online

Some of the work I have undertaken in recent years, either as part of funded academic research or as personal projects

If you would like to discuss working together, or would just like to say hello, please feel free to drop me a line

- Connect on LinkedIn

- ..or say hello on Twitter

Explore your training options in 10 minutes Get Started

- Graduate Stories

- Partner Spotlights

- Bootcamp Prep

- Bootcamp Admissions

- University Bootcamps

- Coding Tools

- Software Engineering

- Web Development

- Data Science

- Tech Guides

- Tech Resources

- Career Advice

- Online Learning

- Internships

- Apprenticeships

- Tech Salaries

- Associate Degree

- Bachelor's Degree

- Master's Degree

- University Admissions

- Best Schools

- Certifications

- Bootcamp Financing

- Higher Ed Financing

- Scholarships

- Financial Aid

- Best Coding Bootcamps

- Best Online Bootcamps

- Best Web Design Bootcamps

- Best Data Science Bootcamps

- Best Technology Sales Bootcamps

- Best Data Analytics Bootcamps

- Best Cybersecurity Bootcamps

- Best Digital Marketing Bootcamps

- Los Angeles

- San Francisco

- Browse All Locations

- Digital Marketing

- Machine Learning

- See All Subjects

- Bootcamps 101

- Full-Stack Development

- Career Changes

- View all Career Discussions

- Mobile App Development

- Cybersecurity

- Product Management

- UX/UI Design

- What is a Coding Bootcamp?

- Are Coding Bootcamps Worth It?

- How to Choose a Coding Bootcamp

- Best Online Coding Bootcamps and Courses

- Best Free Bootcamps and Coding Training

- Coding Bootcamp vs. Community College

- Coding Bootcamp vs. Self-Learning

- Bootcamps vs. Certifications: Compared

- What Is a Coding Bootcamp Job Guarantee?

- How to Pay for Coding Bootcamp

- Ultimate Guide to Coding Bootcamp Loans

- Best Coding Bootcamp Scholarships and Grants

- Education Stipends for Coding Bootcamps

- Get Your Coding Bootcamp Sponsored by Your Employer

- GI Bill and Coding Bootcamps

- Tech Intevriews

- Our Enterprise Solution

- Connect With Us

- Publication

- Reskill America

- Partner With Us

- Resource Center

- Bachelor’s Degree

- Master’s Degree

The Top 10 Most Interesting Music Research Topics

Music is a vast and ever-growing field. Because of this, it can be challenging to find excellent music research topics for your essay or thesis. Although there are many examples of music research topics online, not all are appropriate.

This article covers all you need to know about choosing suitable music research paper topics. It also provides a clear distinction between music research questions and topics to help you get started.

Find your bootcamp match

What makes a strong music research topic.

A strong music research topic must be short, straightforward, and easy to grasp. The primary aim of music research is to apply various research methods to provide valuable insights into a particular subject area. Therefore, your topic must also address issues that are relevant to present-day readers.

Also, for your research topic to be compelling, it should not be overly generic. Try to avoid topics that seem to be too broad. A strong research topic is always narrow enough to draw out a comprehensive and relevant research question.

Tips for Choosing a Music Research Topic

- Check with your supervisor. In some cases, your school or supervisor may have specific requirements for your research. For example, some music programs may favor a comparative instead of a descriptive or correlational study. Knowing what your institution demands is essential in choosing an appropriate research topic.

- Explore scientific papers. Journal articles are a great way to find the critical areas of interest in your field of study. You can choose from a wide range of journals such as The Journal of Musicology and The Journal of the Royal Musical Association . These resources can help determine the direction of your research.

- Determine your areas of interest. Choosing a topic you have a personal interest in will help you stay motivated. Researching music-related subjects is a painstakingly thorough process. A lack of motivation would make it difficult to follow through with your research and achieve optimal results.

- Confirm availability of data sources. Not all music topics are researchable. Before selecting a topic, you must be sure that there are enough primary and secondary data sources for your research. You also need to be sure that you can carry out your research with tested and proven research methods.

- Ask your colleagues: Asking questions is one of the many research skills you need to cultivate. A short discussion or brainstorming session with your colleagues or other music professionals could help you identify a suitable topic for your research paper.

What’s the Difference Between a Research Topic and a Research Question?

A research topic is a particular subject area in a much wider field that a researcher chooses to place his emphasis on. Most subjects are extensive. So, before conducting research, a researcher must first determine a suitable area of interest that will act as the foundation for their investigation.

Research questions are drawn from research topics. However, research questions are usually more streamlined. While research topics can take a more generic viewpoint, research questions further narrow the focus down to specific case studies or seek to draw a correlation between two or more datasets.

How to Create Strong Music Research Questions

Strong music research questions must be relevant and specific. Music is a broad field with many genres and possible research areas. However, your research question must focus on a single subject matter and provide valuable insights. Also, your research question should be based on parameters that can be quantified and studied using available research methods.

Top 10 Music Research Paper Topics

1. understanding changes in music consumption patterns.

Although several known factors affect how people consume music, there is still a significant knowledge gap regarding how these factors influence listening choices. Your music research paper could outline some of these factors that affect music consumer behavior and highlight their mechanism of action.

2. Hip-hop Culture and Its Effect on Teenage Behavior

In 2020, hip-hop and RnB had the highest streaming numbers , according to Statista. Without a doubt, hip-hop music has had a significant influence on the behavior of young adults. There is still the need to conduct extensive research on this subject to determine if there is a correlation between hip-hop music and specific behavioral patterns, especially among teenagers.

3. The Application of Music as a Therapeutic Tool

For a long time, music has been used to manage stress and mental health disorders like anxiety, PTSD, and others. However, the role of music in clinical treatment still remains a controversial topic. Further research is required to separate fact from fiction and provide insight into the potential of music therapy.

4. Contemporary Rock Music and Its Association With Harmful Social Practices

Rock music has had a great influence on American culture since the 1950s. Since its rise to prominence, it has famously been associated with vices such as illicit sex and abuse of recreational drugs. An excellent research idea could be to evaluate if there is a robust causal relationship between contemporary rock music and adverse social behaviors.

5. The Impact of Streaming Apps on Global Music Consumption

Technology has dramatically affected the music industry by modifying individual music consumption habits. Presently, over 487 million people subscribe to a digital streaming service, according to Statista. Your research paper could examine how much of an influence popular music streaming platforms like Spotify and Apple Music have had on how we listen to music.

6. Effective American Music Education Practices

Teaching practices have always had a considerable impact on students’ academic success. However, not all strategies have an equal effect in enhancing learning experiences for students. You can conduct comparative research on two or more American music education practices and evaluate their impact on learning outcomes.

7. The Evolution of Music Production in the Technology-driven Era

One of the aspects of music that is experiencing a massive change is sound production. More than ever before, skilled, tech-savvy music producers are in high demand. At the moment, music producers earn about $70,326 annually, according to ZipRecruiter. So, your research could focus on the changes in music production techniques since the turn of the 21st century.

8. Jazz Music and Its Influence on Western Music Genres

The rich history of jazz music has established it as one of the most influential genres of music since the 19th century. Over the years, several famous composers and leading voices across many other western music genres have been shaped by jazz music’s sound and culture. You could carry out research on the influence of this genre of music on modern types of music.

9. The Effect of Wars on Music

Wars have always brought about radical changes in several aspects of culture, including music styles. Throughout history, we have witnessed wars result in the death of famous musicians. If you are interested in learning about music history in relation to global events, a study on the impact of wars on music will make an excellent music research paper.

10. African Tribal Percussion

African music is well recognized for its unique application of percussion. Historically, several tribes and cultures had their own percussion instruments and original methods of expression. Unfortunately, this musical style has mainly gone undocumented. An in-depth study into ancient African tribal percussion would make a strong music research paper.

Other Examples of Music Research Topics & Questions

Music research topics.

- Popular musical styles of the 20th century

- The role of musical pieces in political movements

- Biographies of influential musicians during the baroque period

- The influence of classical music on modern-day culture

- The relationship between music and fashion

Music Research Questions

- What is the relationship between country music and conservationist ideologies among middle-aged American voters?

- What is the effect of listening to Chinese folk music on the critical thinking skills of high school students?

- How have electronic music production technologies influenced the sound quality of contemporary music?

- What is the correlation between punk music and substance abuse among Black-American males?

- How does background music affect learning and information retention in children?

Choosing the Right Music Research Topic

Your research topic is the foundation on which every other aspect of your study is built. So, you must select a music research topic that gives you room to adequately explore intriguing hypotheses and, if possible, proffer practically applicable solutions.

Also, if you seek to obtain a Bachelor’s Degree in Music , you must be prepared to conduct research during your study. Choosing the right music research topic is the first step in guaranteeing good grades and delivering relevant, high-quality contributions in this constantly expanding field.

Music Research Topics FAQ

A good music research topic should be between 10 to 12 words long. Long, wordy music essay topics are usually confusing. They can make it difficult for readers to understand the goal of your research. Avoid using lengthy phrases or vague terms that could confuse the reader.