An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- BMC Public Health

Rural definition of health: a systematic literature review

Charles gessert.

Essentia Institute of Rural Health, 502 E 2nd St, Duluth, MN 55805 USA

Stephen Waring

Lisa bailey-davis.

Geisinger Center for Health Research, Danville, PA 17822 USA

Melissa Roberts

LCF Research, Albuquerque, NM 87106 USA

Jeffrey VanWormer

Marshfield Clinic Research Foundation, Marshfield, WI 54449 USA

The advent of patient-centered care challenges policy makers, health care administrators, clinicians, and patient advocates to understand the factors that contribute to effective patient activation. Improved understanding of how patients think about and define their health is needed to more effectively “activate” patients, and to nurture and support patients’ efforts to improve their health. Researchers have intimated for over 25 years that rural populations approach health in a distinct fashion that may differ from their non-rural counterparts.

We conducted a systematic review of the literature to assess the extent and strength of evidence for rural definition of health. Studies were eligible for inclusion if they were published in English, reported on original research and presented findings or commentary relevant to rural definition of health, were published over the last 40 years, and were based on observations of rural U.S., Canadian, or Australian populations. Two reviewers were assigned to each selected article and blinded to the other reviewer’s comments. For discordant reviews, a third blinded review was performed.

Of the 125 published articles identified from the literature, 34 included commentary or findings relevant to a rural definition of health. Of these studies, 6 included an urban comparison group. Few studies compared rural and urban definitions of health directly. Findings relevant to rural definition of health covered a broad range; however, good health was commonly characterized as being able to work, reciprocate in social relationships, and maintain independence.

This review largely confirmed many general characteristics on rural views of health, but also documented the extensive methodological limitations, both in terms of quantity and quality, of studies that empirically compare rural vs. urban samples. Most notably, the evidence base in this area is weakened by the frequent absence of parallel comparison groups and standardized assessment tools.

Conclusions

To engage and activate rural patients in their own healthcare, a better understanding of the health beliefs in rural populations is needed. This review suggests that rural residents may indeed hold distinct views on how to define health, but more rigorous studies are needed to confirm these findings.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s12889-015-1658-9) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

The passage of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) in 2010 heralded a significant shift in American health care, with increased emphasis on population health, disease prevention, and cost containment. These new areas of emphasis are prominent in several initiatives that have emerged in the wake of the ACA, including Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs), which tie provider reimbursements to measures of quality of care and reductions in the total cost of care for assigned populations of patients. The Patient Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) also emerged, charged with examining the relative health outcomes, clinical effectiveness, and appropriateness of medical treatments. Underlying these initiatives is a renewed emphasis on patient engagement in health care and, more specifically, on patient activation.

While patient engagement and patient activation are often used interchangeably, patient engagement denotes the broad involvement of patients and caregivers in all aspects of health care is based on the principle of shared responsibility [ 1 ]. Patient activation , a component of patient engagement, emphasizes patients’ willingness and ability to take independent actions to manage their health and care [ 2 ]. Patient activation has been found to be associated with better health outcomes, better health care experiences, and reduced probability of adverse markers such as emergency department use, obesity, and smoking [ 2 , 3 ]. Health care systems are encouraging primary care providers to practice patient-centered care, employing strategies that engage with and activate patients. This approach is grounded in the perspective that care should focus on patients and finding a common ground between patients and clinicians when choosing preventive and treatment care pathways.

This focus on patient-centered care challenges policy makers, health care administrators, clinicians, and patient advocates to understand the factors that contribute to effective patient activation. Individuals define “health” on the basis of their personal health-related beliefs, values and knowledge. Improved understanding of how patients think about and define their health is needed to more effectively “activate” patients, and to nurture and support patients’ efforts to improve their health.

For more than 25 years, researchers have suggested that rural populations may have a distinct view of health that differs from other non-rural populations. Seminal research in 1987 by Weinert and Long reported that rural people predominantly associated health with “the ability to work” [ 4 ], but were less likely to regard cosmetic, comfort, or life-prolonging aspects of health as important. In subsequent work, Weinert and Burman concluded that the rural “function-based definition of health” may contribute to delays in seeking health care, even in the face of grave illness [ 5 ]. In a study of the health beliefs of rural elders, Davis et al. found that subjects described health in terms of autonomy and self-reliance; they feared loss of health primarily because it could lead to “being a burden to others” [ 6 ].

These early studies indicate the need for a richer understanding of rural “frames” for health, but they lacked a direct comparison to health views from non-rural counterparts. If rural and non-rural populations indeed commonly think about or define their health differently, then efforts to engage such populations in promoting and preserving health must be better informed, particularly as health care providers increasingly focus on patient-centered care. The purpose of this study was to systematically review and critique the extent and strength of the published literature regarding how persons living in rural areas define health. In addition, we sought comparisons between rural and urban concepts of health. We were interested in findings that could guide improved patient engagement and patient activation in rural communities of the United States and similar industrialized countries. We specifically examined health values and beliefs as constructs rather than knowledge per se , as knowledge generation is better understood as a continuous process influenced by values, beliefs, motivation, skills, and context [ 7 , 8 ].

We conducted a systematic review of the literature to assess the current scientific understanding of rural definitions of health [ 9 ]. The online databases PubMed, CINAHL, PsycINFO, AnthroSource, and Sociological Abstracts were searched, followed by a manual search of the reference sections of studies identified through the online database search. Key search terms that were used were “rural population, “attitude to health,” “health behavior,” “health promotion,” “health belief,” and “health values.” Studies were eligible for inclusion if they were published in English, reported on original research, presented findings or commentary relevant to rural definitions of health, were published over the last 40 years (01/01/1972-03/31/14), and were based on observations of rural U.S., Canadian, or Australian populations. These countries were selected because of their large rural populations, including remote/frontier communities, and their access to Western health care. No restrictions were placed on sample size, research design, or length of follow-up.

For data extraction and synthesis, two reviewers were assigned to each article and blinded to the other reviewer’s comments. For discordant reviews, a third blinded review was performed. Articles were reviewed for content, methodology and rigor, with information collected on study design, characteristics of the study population, whether articles related to rural definitions of health, the definition of rural, and whether there was a comparison group (e.g., rural vs. urban). All information was captured in a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet for summarizing and comparisons. Further details on the review process are provided in Additional file 1 .

The review process identified 34 articles as having fulfilled the criterion of assessing how rural residents define health. These articles were assigned an evidence grade of A, B, or C depending on methodological quality and supporting evidence of the conclusions, based on a previously used adaptation of the American Diabetes Association's (ADA) evidence grading system [ 10 , 11 ].

Because this was a retrospective review of data from previous published studies, no patient informed consent procedures were applicable, and the study was exempt from review by the Essentia Health Institutional Review Board.

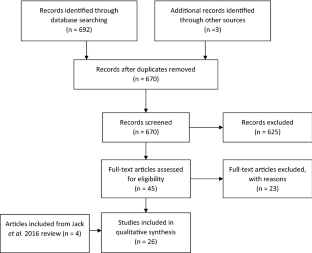

Three hundred and eighty two articles were identified using the study’s search terms; an additional fifteen articles were identified as cited references during the review process. From these, 125 articles were selected for initial review by the lead author. Ninety-one articles were excluded because they did not report on original research or were outside of the scope of the current inquiry. Thirty-four were utilized for this review; 4 were commentaries about a rural definition of health [ 4 , 12 - 14 ] and 30 contained findings relevant to a rural definition of health (see Figure 1 ). Of the latter 30 studies, 6 [ 15 - 20 ] included an urban comparison group (see Table 1 ). The remaining 24 articles [ 6 , 21 - 43 ] did not include a comparison group. Few studies compared rural and urban definitions of health directly.

PRISMA diagram of literature review process.

Published research relevant to rural definition of health: with comparison groups (N = 6) and without comparison groups (N = 24)

The 6 studies that compared findings from both rural and urban populations were of primary interest. Findings relevant to a rural definition of health covered a broad range; however, good health was commonly characterized as being able to work, reciprocate in social relationships, and maintain independence (see Table 1 ). In a focus group study by Gessert et al., rural responders were more likely to express greater willingness to accept ill health and even death as natural phenomena, whereas urban residents expressed stronger aversion to death and greater insistence on aggressive end of life care [ 15 ]. In a study to examine factors influencing individual capacity to manage coronary artery disease risk, both gender and culture (rural vs urban) were identified [ 18 ]. Rural residents expressed belief that a “work hard, eat hard” attitude kept them healthy despite the stress of their work and living in a rural environment. Additionally, rural residents would only seek a physician’s help if physical functioning was severely impaired [ 18 ]. Rural vs. urban differences were also evident in driving behavior, with rural residents more likely to participate in risky behaviors and less likely to have confidence in the utility of safety interventions [ 16 ]. Another study found that persons living in the most remote environments were more likely to hold highly stigmatized attitudes toward mental health care and these views were strongly predictive of willingness to actually seek care [ 17 ].

Comments from participants in several of the reviewed studies (see Table 1 ) centered on three traits that influenced their definition of health: independence, stoicism, and fatalism. Thorson et al. found that rural elders were less likely than urban elders to turn to health care providers for issues they considered non-urgent, regardless of how long a particular symptom had been present [ 20 ]. Hoyt et al. concluded that the agrarian ideology of self-reliance and rugged independence, coupled with a lessened sense of confidentiality and increased pressure to conform due to the smaller, more intimate nature of smaller rural environments, was not conducive to seeking mental health care, particularly for males [ 17 ]. Attitudes of rural and urban residents toward seeking medical care were similar in the Harju et al. study [ 16 ], but were somewhat incongruent with self-reported care seeking behaviors. Fear of hospitals was associated with medical adherence in rural residents and good health habits in urbanites [ 16 ].

Original research articles that did not include a comparison group (n = 29) also revealed influential themes among rural residents’ definitions of health: autonomy, avoiding medical care, and spiritual health. Rural elders participating in a study in Alberta (Canada) reported that ability to work and ability to function, irrespective of symptoms or underlying illness, was their definition of “health” [ 29 ]. In a focus group study of individuals from rural communities in Wyoming, “cowboy up to continue doing what you have to do” was a prevailing theme in responses pertaining to how participants viewed health [ 34 ]. Arcury et al., reporting from interviews of elderly residents in two rural communities in North Carolina, concluded that the residents’ definition of health integrated physical, mental, spiritual, and social aspects of health [ 21 ]. Another study of rural elderly in New Mexico reported that the common definition of health consisted of remaining autonomous and independent, avoiding contact with the health care system [ 23 ]. Lastly, from a study that included interviews of rural health providers in Colorado, one provider’s perspective, based on a 90 year old patient still engaged in ranching, was that work at any age gave patients a sense of purpose that kept them going regardless of the physical challenges of getting around [ 35 ].

This review assessed the extent and strength of evidence regarding how rural people in the United States, Canada and Australia view health differently than their urban counterparts. The overarching objective of this review was to better understand rural definitions of health and how they might be applied in health education messaging and patient engagement/ activation strategies related to disease prevention and treatment. This review largely confirmed many general characteristics previously observed on rural views of health, but also documented the extensive methodological limitations of studies that empirically compared rural vs. urban samples. The evidence in this area is particularly weakened by the routine absence of parallel comparison groups and standardized assessment tools, among other limitations.

Despite these limitations, several consistent characteristics of a rural definition of health were identified. Rural populations tend to emphasize functional aspects of health, especially the preservation of the ability to work and to fulfill (traditional) social roles. Rural people tend to frame health in terms of independence and self-sufficiency, and to accept ill health with higher degrees of stoicism and seemingly more fatalism. If more rigorous future studies can confirm these findings in rural populations, health education and patient engagement/activation programs can be better structured in ways that capitalize on the strong underlying motivations to preserve independence through good health practices. Our findings suggest that rural populations might be more responsive to health messages that emphasize physical function, independence, self-sufficiency, and the ability to reciprocate in social roles and perceived obligations.

Projects designed to improve the health of rural populations face a number of challenges. At a macro level, rural settings are not homogenous in terms of culture, economic hardship, or sense of history/community. Accordingly, findings from one rural community or similar group of rural communities may not be applicable to other rural communities or regions. Much of the previous research on rural health reported findings from primarily agrarian samples, which is an increasingly small subset of rural settings and not necessarily similar to other rural areas that rely heavily on manufacturing, forestry, or subsistence occupations. This distinction has become more pronounced in recent years with the growth of rural recreation and retirement communities, as well as other rural environments where the agrarian economy or culture has limited influence.

Individual characteristics are also important in rural health attitudes and beliefs. Several investigators reported that religious or spiritual health was an integral part of the definition of health in the rural communities studied. Socioeconomic status is recognized as a key factor in health attitudes and practices, yet few studies in the current review controlled for the socioeconomic status of rural participants. Age and length of time in the community may also be important because some of the most distinctive rural definitions of health were held by older residents (particularly those who had a life-long history of rural residence). The current review also suggests that some work histories such as lifelong farming or ranching may be associated with the more distinct views of health framed by physical function and capacity to work. A better understanding of rural attitudes and beliefs is needed to engage and activate rural residents in managing their health and care. Thus, further study of how rural residents define health will contribute to the implementation of patient-centered care in rural communities.

This study was limited principally by its focus on industrialized Western countries. Additional research is needed both to examine rural concepts of health in a wider range of settings, especially in the developing world. This study was also limited by the paucity of rigorous studies that compared rural and urban perceptions of health directly. This is a rich arena for future research.

There is increasing interest in engaging and activating patients in their own healthcare. To do so effectively in rural areas, a better understanding of the health beliefs in rural populations is needed. This review suggests that rural residents may indeed define health in their own way (e.g., functional independence). However, a formal assessment of the risk of bias was not performed in this paper because the vast majority of studies were qualitative and did not include direct comparisons between rural vs. non-rural samples. As such, selection bias remains an overshadowing concern in this collective body of literature, highlighting the need for more rigorous studies to confirm our findings. Research on rural definitions of health is further complicated by continuously changing rural lifestyles and landscapes as demographics and economic emphases shift. Despite such challenges, however, further research on rural health beliefs and attitudes is critical as American healthcare reform legislation calls for broader, systems-based strategies to improve the public’s health. To better engage and activate rural patients in their own healthcare, a better understanding of the health beliefs of targeted rural populations is needed.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge Allise Taran (Essentia Institute of Rural Health) for assisting with final preparation of the manuscript.

Abbreviations

Additional file.

Literature search and review methodology.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

All six of the authors participated actively in the conception and design of this review of the literature; the selection and review of articles from the literature; the drafting, review and editing of the manuscript; and the preparation of the final draft. All of the authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ information

CG has conducted and published research on rural health issues, including access to care in rural areas and rural-urban differences in end-of-life care. SW currently conducts and publishes research on rural health issues, particularly in the elderly. LBD has conducted and published research that observed rural and urban disparities in the prevalence of childhood obesity while controlling for socio-economic factors. PC has conducted research regarding rural and tribal communities and health (including behavioral health) outcomes and prevention strategies. MR has focused on patient satisfaction with care as part of her chronic disease and primary care outcomes research. JV has led several studies on rural disparities in preventive healthcare, as well as a large rural health improvement initiative in Minnesota.

Contributor Information

Charles Gessert, Email: moc.oohay@tressegc .

Stephen Waring, Email: [email protected] .

Lisa Bailey-Davis, Email: ude.regnisieg@sivadyeliabdl .

Pat Conway, Email: [email protected] .

Melissa Roberts, Email: gro.hcraeserfcl@streborm .

Jeffrey VanWormer, Email: [email protected] .

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Rural definition of health: a systematic literature review

2015, BMC public health

The advent of patient-centered care challenges policy makers, health care administrators, clinicians, and patient advocates to understand the factors that contribute to effective patient activation. Improved understanding of how patients think about and define their health is needed to more effectively "activate" patients, and to nurture and support patients' efforts to improve their health. Researchers have intimated for over 25 years that rural populations approach health in a distinct fashion that may differ from their non-rural counterparts. We conducted a systematic review of the literature to assess the extent and strength of evidence for rural definition of health. Studies were eligible for inclusion if they were published in English, reported on original research and presented findings or commentary relevant to rural definition of health, were published over the last 40 years, and were based on observations of rural U.S., Canadian, or Australian populations. Tw...

Related Papers

Palliative Medicine

Steve Iliffe

Canadian journal on aging = La revue canadienne du vieillissement

Juanita Bacsu

Existing cognitive health literature focuses on the perspectives of older adults with dementia. However, little is known about the ways in which healthy older adults without dementia understand their cognitive health. In rural communities, early dementia diagnosis may be impeded by numerous factors including transportation challenges, cultural obstacles, and inadequate access to health and support services. Based on participant observation and two waves of 42 semi-structured interviews, this study examined healthy, rural older adults' perceptions of cognitive health. By providing an innovative theoretical foundation informed by local perspectives and culture, findings reveal a complex and multidimensional view of cognitive health. Rural older adults described four key areas of cognitive health ranging from independence to social interaction. As policy makers, community leaders, and researchers work to address the cognitive health needs of the rural aging demographic, it is essen...

Rural and Remote Health

Prairie Women's Centre of Excellence, …

Brigette Krieg

Janice Linton

FROM AUTHOR]; Copyright of Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology is the property of Springer Science & Business Media B.V. and its content may not be copied or emailed to multiple sites or posted to a listserv without the copyright holder's express written permission. However, users may print, download, or email articles for individual use. This abstract may be abridged. No warranty is given about the accuracy of the copy. Users should refer to the original published version of the material for the full abstract. (Copyright applies to all Abstracts.) LaVallie, D. L., Wolf, F. M., Jacobsen, C., & Buchwald, D. (2008). Barriers to cancer clinical trial participation among native elders. Ethnicity and Disease, 18(2), 210-217. Objectives: American Indians/Alaska Native: are underrepresented in clinical trials. There fore, they must participate in large-scak cancer clinical trials to ensure the generaliz ability of trial results and improve their acces: to high-quality treatment. Our ...

International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health

Reproductive health disparities in the Appalachian region may be driven by barriers to healthcare access. However, the barriers specific to accessing family planning services in Appalachia have not yet been identified from the perspectives of Appalachian community members. Moreover, it is unclear how community members might perceive elevated levels of opioid use in the region to impact family planning practices. To fill this gap in knowledge, the current qualitative study explored community perspectives about family planning in Appalachia in the context of the opioid epidemic for the purpose of developing a survey instrument based on these responses. We conducted three video call focus group interviews with community stakeholders, those who live, work and are invested in Appalachia (N = 16), and analyzed the responses using Levesque, Harris, and Russell’s (2013) five pillars of healthcare access as a framework to categorize family planning practices and perceptions of service needs ...

Tom Shakespeare

We aim to explore the barriers to accessing primary care for socio-economically disadvantaged older people in rural areas. Using a community recruitment strategy, fifteen people over 65 years, living in a rural area, and receiving financial support were recruited for semi-structured interviews. Four focus groups were held with rural health professionals. Interviews and focus groups were audio-recorded and transcribed. Thematic analysis was used to identify barriers to primary care access. Older people's experience can be understood within the context of a patient perceived set of unwritten rules or social contract-an individual is careful not to bother the doctor in return for additional goodwill when they become unwell. However, most found it difficult to access primary care due to engaged telephone lines, availability of appointments, interactions with receptionists; breaching their perceived social contract. This left some feeling unwelcome, worthless or marginalised, especia...

Journal of Nursing Scholarship

Kathy Magilvy

Diversity of Research in Health Journal

Roger Pilon

RELATED PAPERS

International Journal of Qualitative Methods

Lic. Maria Gabriela Mangas

BMC Public Health

Carol Cummings

Fenna Van Nes

Nursing Ethics

Inbal Hochwald

The Gerontologist

Jordan Lewis

Jordan Lewis, Ph.D.

Joshua Hauser

Sue Lawrence

Rob Beamish

BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth

Tamara Mulenga

The Journal of Rural Health

Cynthia Peden-mcalpine

Journal of Rural Health

Robin Kruse

Journal of Aging and Health

Betty Black

Asian Nursing Research

farahnaz mohammadi

The Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing

Karen Harkness , Kay Currie

Journal of Cross Cultural Gerontology

Jordan P Lewis

Charles Furlotte

International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry

Health Expectations

Marcella Ambenne

African Health Sciences

Sharon Koehn

BMC Medical Ethics

Joan Bottorff

BMC Health Services Research

INQUIRY: The Journal of Health Care Organization, Provision, and Financing

Drona Rasali

International Journal of Mental Health Systems

Rishav Koirala

Tracy Wasylak

John Stanifer

BMC Geriatrics

Jiong Tu 涂炯

Kate Riegle van West

Annual review of nursing research

Deirdre Thornlow

Bonnie Duran

Ketaki Chowkhani

INNOVATIONS in pharmacy

ellis owusu-dabo

2019 AAG Conference Oral Presentations – Abstracts

Daphne Flynn , Eden Potter [she/her] , Jon McCormack

Emily Hauenstein

Madhusudan Subedi

Canadian Journal on Aging / La Revue canadienne du vieillissement

Wendy Hulko

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

ACC 2024 Congress

Catch up on all the top stories and latest evidence in cardiology research with our ACC 2024 Congress hub page.

Springer Medicine

Open Access 01-12-2015 | Research article

Rural definition of health: a systematic literature review

Authors: Charles Gessert, Stephen Waring, Lisa Bailey-Davis, Pat Conway, Melissa Roberts, Jeffrey VanWormer

Published in: BMC Public Health | Issue 1/2015

Conclusions

Please log in to get access to this content, other articles of this issue 1/2015.

Research article

Tuberculosis treatment delays and associated factors within the Zimbabwe national tuberculosis programme

Reaching older people with pa delivered in football clubs: the reach, adoption and implementation characteristics of the extra time programme, do discrimination, residential school attendance and cultural disruption add to individual-level diabetes risk among aboriginal people in canada, does the social context of early alcohol use affect risky drinking in adolescents prospective cohort study, physician and patient concordance of report of tobacco cessation intervention in primary care in india, efficient national surveillance for health-care-associated infections.

- Medical Journals

- Webcasts & Webinars

- CME & eLearning

- Newsletters

- ESMO Congress 2023

- 2023 ERS Congress

- ESC Congress 2023

- EHA2023 Hybrid Congress

- 2023 ASCO Annual Meeting Coverage

- Advances in Alzheimer’s

- About Springer Medicine

- Diabetology

- Endocrinology

- Gastroenterology

- Geriatrics and Gerontology

- Gynecology and Obstetrics

- Infectious Disease

- Internal Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine

- Rheumatology

Advertisement

Impact of Community Health Workers on Access to Care for Rural Populations in the United States: A Systematic Review

- Published: 24 November 2021

- Volume 47 , pages 539–553, ( 2022 )

Cite this article

- Carole R. Berini ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-1772-7970 1 , 2 ,

- Heather S. Bonilha 3 &

- Annie N. Simpson 1

2009 Accesses

17 Citations

2 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

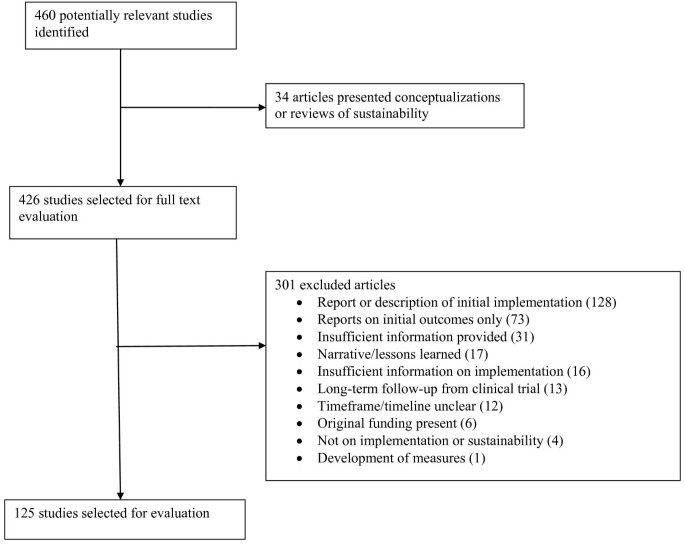

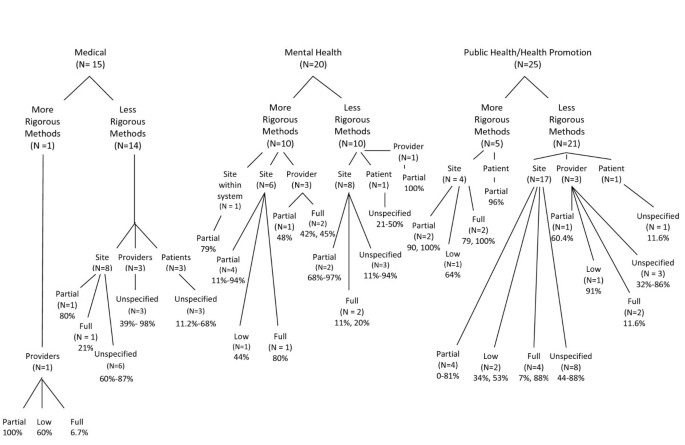

Community Health Worker (CHW) interventions have shown potential to reduce inequities for underserved populations. However, there is a lack of support for CHW integration in the delivery of health care. This may be of particular importance in rural areas in the Unites States where access to care remains problematic. This review aims to describe CHW interventions and their outcomes in rural populations in the US. Peer reviewed literature was searched in PubMed and PsycINFO for articles published in English from 2015 to February 2021. Title and abstract screening was performed followed by full text screening. Quality of the included studies was assessed using the Downs and Black score. A total of 26 studies met inclusion criteria. The largest proportion were pre-post program evaluation or cohort studies (46.2%). Many described CHW training (69%). Almost a third (30%) indicated the CHW was integrated within the health care team. Interventions aimed to provide health education (46%), links to community resources (27%), or both (27%). Chronic conditions were the concern for most interventions (38.5%) followed by women’s health (34.6%). Nearly all studies reported positive improvement in measured outcomes. In addition, studies examining cost reported positive return on investment. This review offers a broad overview of CHW interventions in rural settings in the United States. It provides evidence that CHW can improve access to care in rural settings and may represent a cost-effective investment for the healthcare system.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Access to health services among culturally and linguistically diverse populations in the Australian universal health care system: issues and challenges

Resham B. Khatri & Yibeltal Assefa

Public health system challenges in the Free State, South Africa: a situation appraisal to inform health system strengthening

B. Malakoane, J. C. Heunis, … W. H. Kruger

Aboriginal community controlled health organisations address health equity through action on the social determinants of health of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples in Australia

O. Pearson, K. Schwartzkopff, … on behalf of the Leadership Group guiding the Centre for Research Excellence in Aboriginal Chronic Disease Knowledge Translation and Exchange (CREATE)

Data Availability

All data is from the published literature.

Code Availability

not applicable.

Bolin, J. N., Bellamy, G. R., Ferdinand, A. O., et al. (2015). Rural healthy people 2020: new decade, same challenges. The Journal of Rural Health, 31 (3), 326–333.

Article Google Scholar

Cardarelli, R., Bausch, G., Murdock, J., & Chyatte, M. R. (2018). Return-on-Investment (ROI) analyses of an inpatient lay health worker model on 30-day readmission rates in a rural community hospital. The Journal of Rural Health, 34 (4), 411–422.

Cardarelli, R., Horsley, M., Ray, L., et al. (2018). Reducing 30-day readmission rates in a high-risk population using a lay-health worker model in Appalachia Kentucky. Health Education Research, 33 (1), 73–80.

Center for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020). About Rural Health. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/ruralhealth/about.html

Cramer, M. E., Mollard, E. K., Ford, A. L., Kupzyk, K. A., & Wilson, F. A. (2018). The feasibility and promise of mobile technology with community health worker reinforcement to reduce rural preterm birth. Public Health Nursing, 35 (6), 508–516.

Crespo, R., Christiansen, M., Tieman, K., & Wittberg, R. (2020). An emerging model for community health worker-based chronic care management for patients with high health care costs in rural Appalachia. Preventing Chronic Disease, 17 , E13.

Downs, S. H., & Black, N. (1998). The feasibility of creating a checklist for the assessment of the methodological quality both of randomised and non-randomised studies of health care interventions. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health, 52 (6), 377–384.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Falk, D., Falk, D., Cubbin, C., et al. (2018). Increasing breast and cervical cancer screening in rural and border texas with friend to friend plus patient navigation. Journal of Cancer Education, 33 (4), 798–805.

Falk, D., Foley, K., Weaver, K. E., Jones, B., & Cubbin, C. (2020). An Evaluation of Breast and Cervical Cancer Screening Outcomes in an Education and Patient Navigation Program in Rural and Border Texas. Journal of Cancer Education, 10, Epub ahead of print.

Fawcett, K., Neff, R., Freese Decker, C., & Faber, J. (2018). Achieving IHIʼs triple aim by utilizing core health program with community health workers in rural communities. Family & Community Health, 41 (4), 255–264.

Felix, H. C., Ali, M., Bird, T. M., Cottoms, N., & Stewart, M. K. (2019). Are community health workers more effective in identifying persons in need of home and community-based long-term services than standard-passive approaches. Home Health Care Services Quarterly, 38 (3), 194–208.

Felix, H. C., Mays, G. P., Stewart, M. K., Cottoms, N., & Olson, M. (2011). Medicaid savings resulted when community health workers matched those with needs to home and community care. Health Affairs, 30 (7), 1366–1374.

Feltner, F., Thompson, S., Baker, W., & Slone, M. (2017). Community health workers improving diabetes outcomes in a rural Appalachian population. Social Work in Health Care, 56 (2), 115–123.

Glenn, L. E., Nichols, M., Enriquez, M., & Jenkins, C. (2020). Impact of a community-based approach to patient engagement in rural, low-income adults with type 2 diabetes. Public Health Nursing, 37 (2), 178–187.

Hopper, L. N., Blackman, K. F., Page, R. A., et al. (2017). Seeds of HOPE: incorporating community-based strategies to implement a weight-loss and empowerment intervention in Eastern North Carolina. North Carolina Medical Journal, 78 (4), 230–236.

Hunter, J. B., de Zapien, J. G., Papenfuss, M., Fernandez, M. L., Meister, J., & Giuliano, A. R. (2004). The impact of a “Promotora” on increasing routine chronic disease prevention among women aged 40 and older at the US-Mexico Border. Health Education & Behavior, 31 (4), 18–28.

Jack, H. E., Arabadjis, S. D., Sun, L., Sullivan, E. E., & Phillips, R. S. (2016). Impact of community health workers on use of healthcare services in the United States: a systematic review. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 32 (3), 325–344.

Kitzman, P., Hudson, K., Sylvia, V., Feltner, F., & Lovins, J. (2017). Care coordination for community transitions for individuals post-stroke returning to low-resource rural communities. Journal of Community Health, 42 (3), 565–572.

Krantz, M. J., Coronel, S. M., Whitley, E. M., Dale, R., Yost, J., & Estacio, R. O. (2013). Effectiveness of a community health worker cardiovascular risk reduction program in public health and health care settings. American Journal of Public Health, 103 (1), e19–e27.

Krok-Schoen, J. L., Oliveri, J. M., Young, G. S., Katz, M. L., Tatum, C. M., & Paskett, E. D. (2015). Evaluating the stage of change model to a cervical cancer screening intervention among Ohio Appalachian women. Women and Health, 56 (4), 468–4886.

Logan, R. I., & Castañeda, H. (2020). Addressing health disparities in the rural United States: advocacy as caregiving among community health workers and Promotores de Salud. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17 (24), 10.

Luque, J., Tarasenko, Y., Reyes-Garcia, C., et al. (2017). Salud es Vida: a Cervical Cancer Screening Intervention for Rural Latina Immigrant Women. Journal of Cancer Education, 32 (4), 690–699.

Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., Altman, D. G., & Group, T. P. (2009) Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLOS Medicine, 6 (7), e1000097

NACHW. (2021). CHW Networks and Training Programs. NACHW. https://nachw.org/membership/chw-networks-and-certification-programs/

Nkonki, L., Tugendhaft, A., & Hofman, K. (2017). A systematic review of economic evaluations of CHW interventions aimed at improving child health outcomes. Human Resources for Health, 15 (1), 19.

Postma, J. M., Smalley, K., Ybarra, V., & Kieckhefer, G. (2011). The Feasibility and acceptability of a home-visitation, asthma education program in a rural, Latino a population. The Journal of Asthma, 48 (2), 139–146.

Probst, J., Zahnd, W., & Breneman, C. (2019). Declines in pediatric mortality fall short for rural US children. Health Affairs, 38 (12), 2069–2076.

Reed, P. H., & Hulton, L. J. (2017). Community health workers in collaboration with case managers to improve quality of life for patients with heart failure. Professional Case Management, 22 (3), 144–148.

Riedy, C. A., Weinstein, P., Mancl, L., Garson, G., Huebner, C. E., Milgrom, P., Grembowski, D., Shepherd-Banigan, M., Smolen, D., & Sutherland, M. (2015). Dental attendance among low-income women and their children following a brief motivational counseling intervention: a community randomized trial. Social Science & Medicine, 1982 (144), 9–18.

Roland, K. B., Milliken, E. L., Rohan, E. A., et al. (2017). Use of Community health workers and patient navigators to improve cancer outcomes among patients served by federally qualified health centers: a systematic literature review. Health Equity, 1 (1), 61–76.

Rural Health Information Hub. (2020). Substance Use and Misuse in Rural Areas. Rural Health Information Hub. https://www.ruralhealthinfo.org/topics/substance-use#:~:text=Though%20often%20perceived%20to%20be,in%20towns%20of%20every%20size .

Ryabov, I. (2014). Cost-effectiveness of community health workers in controlling diabetes epidemic on the US–Mexico border. Public Health, 128 (7), 636–642.

Samuel-Hodge, C. D., Gizlice, Z., Allgood, S. D., et al. (2020). Strengthening community-clinical linkages to reduce cardiovascular disease risk in rural NC: feasibility phase of the CHANGE study. BMC Public Health, 20 (1), 264.

Schleiff, M. J., Peters, D. H., & Surkan, P. J. (2020). Comparative case analysis of the role of community health workers in rural and low-income populations of west Virginia and the United States. The Journal of Ambulatory Care Management, 43 (3), 205–220.

Smith, L., Atherly, A., Campbell, J., Flattery, N., Coronel, S., & Krantz, M. (2019). Cost-effectiveness of a statewide public health intervention to reduce cardiovascular disease risk. BMC Public Health, 19 (1), 1234.

Suther, S., Battle, A. M., Battle-Jones, F., & Seaborn, C. (2016). Utilizing health ambassadors to improve type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease outcomes in Gadsden County, Florida. Evaluation and Program Planning, 55 , 17–26.

Thompson, B., Carosso, E. A., Jhingan, E., et al. (2017). Results of a randomized controlled trial to increase cervical cancer screening among rural Latinas. Cancer, 123 (4), 666–674.

Trump, L. J., & Mendenhall, T. J. (2017). Community health workers in diabetes care: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Families Systems & Health, 35 (3), 320–340.

Turner, B. J., Liang, Y., Rodriguez, N., et al. (2018). Randomized trial of a low-literacy chronic pain self-management program: analysis of secondary pain and psychological outcome measures. The Journal of Pain, 19 (12), 1471–1479. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpain.2018.06.010

Vilchis, H., Onstad, L. E., Benavidez, R., et al. (2019). Una Mano Amiga: pilot test of a patient navigator program for Southwest New Mexico. Journal of Cancer Education, 34 (1), 173–179.

Weaver, A., & Lapidos, A. (2018). Mental health interventions with community health workers in the United States: a systematic review. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, 29 (1), 159–180.

Yaemsiri, S., Alfier, J. M., Moy, E., et al. (2019). Healthy people 2020: rural areas lag in achieving targets for major causes of death. Health Affairs (Project Hope), 38 (12), 2027–2031.

Download references

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Teri Lynn Herbert for her expert assistance in finalizing the database search strategies.

There was no funding for this study.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Healthcare Leadership and Management, Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, SC, 29425, USA

Carole R. Berini & Annie N. Simpson

Department of Family Medicine, Medical University of South Carolina, 5 Charleston Center Dr., Suite 263, MSC192, Charleston, SC, 29425, USA

Carole R. Berini

Department of Rehabilitation Sciences, Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, SC, 29425, USA

Heather S. Bonilha

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

All authors contributed to the conceptualization of the study; the first author performed the initial literature search and rating, the second author served as second rater, all authors contributed to subsequent analysis; the first author produced the initial draft, all authors critically revised the work and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Carole R. Berini .

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest.

Authors have no conflicts of interests to disclose.

Ethical Approval

Because the study is based on previously published information, no institutional review board approval is needed.

Consent to Participate

Not applicable.

Consent for Publication

Additional information, publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Search strategies

PubMed: ((Rural OR “rural health”) AND (“continuum of care” OR “Access to care” OR “health systems” OR “Women’s health” OR “disease prevention” OR “patient education” OR “managed care” OR “program cost” OR “health care system” OR "cost–benefit" OR "cost-effectiveness" OR "ED visit" OR “fees” OR "emergency department visit" OR "emergency room visit" OR "ER visit" OR "urgent care use" OR "urgent care visit" OR cost OR expenditure OR expense OR finance OR hospitalization OR payment OR profit OR readmission OR “Return on investment” OR savings OR utilization OR “insurance, health” [MeSH Terms] OR "costs and cost analysis"[MeSH Terms] OR "Medicaid/economics"[MeSH Terms] OR "Medicaid/utilization"[MeSH Terms] OR "Models, econometric"[MeSH Terms]) AND ("Abuse Counselor" OR "Birth attendant" OR "Case coordinator" OR "Community coordinator" OR "Community health advocate" OR "Community health aide" OR "Community health educator" OR "Community health representative" OR "Community health worker" OR "Community liaison" OR "Community organizer" OR "Community social worker" OR "Doula" OR "Family advocate" OR "Family support worker" OR "Health adviser" OR "Health advisor" OR "Health advocate" OR "Health agent" OR "Health assistant" OR "Health attendant" OR “health care volunteer” OR "Health coach" OR "Health Communicator" OR "Health Educator" OR "Home Care Worker" OR "Home health aide" OR "Home Visitor" OR "Intake specialist" OR "Lay attendant" OR "Lay health advisor" OR “Lay health adviser” OR "Lay health worker" OR "Lay personnel" OR "Medical representative" OR "Mental Health Worker" OR "Nutrition educator" OR "Outreach Coordinator" OR "Outreach Educator" OR "Outreach Worker" OR "Parent Aide" OR "Parent Liaison" OR "Patient navigator" OR "Peer advocate" OR "Peer coach" OR "Peer leader" OR "Promotora” OR "Recovery coach" OR Paraprofessional OR "community health workers"[MeSH Terms] OR "health educators"[MeSH Terms] OR "patient navigation"[MeSH Terms] OR "home health aides"[MeSH Terms])).

PsycINFO: (Rural OR “rural health”) AND (“continuum of care” OR “Access to care” OR “health systems” OR “Women’s health” OR “disease prevention” OR “patient education” OR “managed care” OR “program cost” OR “health care system” OR "cost–benefit" OR "cost-effectiveness" OR "ED visit" OR “fees” OR "emergency department visit" OR "emergency room visit" OR "ER visit" OR "urgent care use" OR "urgent care visit" OR cost OR expenditure OR expense OR finance OR hospitalization OR payment OR profit OR readmission OR “Return on investment” OR savings OR utilization) AND ("Abuse Counselor" OR "Birth attendant" OR "Case coordinator" OR "Community coordinator" OR "Community health advocate" OR "Community health aide" OR "Community health educator" OR "Community health representative" OR "Community health worker" OR "Community liaison" OR "Community organizer" OR "Community social worker" OR "Doula" OR "Family advocate" OR "Family support worker" OR "Health adviser" OR "Health advisor" OR "Health advocate" OR "Health agent" OR "Health assistant" OR "Health attendant" OR “health care volunteer” OR "Health coach" OR "Health Communicator" OR "Health Educator" OR "Home Care Worker" OR "Home health aide" OR "Home Visitor" OR "Intake specialist" OR "Lay attendant" OR "Lay health advisor" OR “Lay health adviser” OR "Lay health worker" OR "Lay personnel" OR "Medical representative" OR "Mental Health Worker" OR "Nutrition educator" OR "Outreach Coordinator" OR "Outreach Educator" OR "Outreach Worker" OR "Parent Aide" OR "Parent Liaison" OR "Patient navigator" OR "Peer advocate" OR "Peer coach" OR "Peer leader" OR "Promotora” OR "Recovery coach" OR Paraprofessional).

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Berini, C.R., Bonilha, H.S. & Simpson, A.N. Impact of Community Health Workers on Access to Care for Rural Populations in the United States: A Systematic Review. J Community Health 47 , 539–553 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-021-01052-6

Download citation

Accepted : 12 November 2021

Published : 24 November 2021

Issue Date : June 2022

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-021-01052-6

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Community Health Worker

- Rural Health

- Underserved Populations

- Access to Health Care

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

Europe PMC requires Javascript to function effectively.

Either your web browser doesn't support Javascript or it is currently turned off. In the latter case, please turn on Javascript support in your web browser and reload this page.

Search life-sciences literature (43,960,127 articles, preprints and more)

- Free full text

- Citations & impact

- Similar Articles

Rural definition of health: a systematic literature review.

Author information, affiliations.

- Gessert C 1

- Bailey-Davis L 2

- Roberts M 3

- VanWormer J 4

ORCIDs linked to this article

- Roberts M | 0000-0002-1314-4906

- Bailey-Davis L | 0000-0002-8781-1521

- Waring S | 0000-0002-9674-0083

BMC Public Health , 14 Apr 2015 , 15: 378 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-015-1658-9 PMID: 25879818 PMCID: PMC4406172

Abstract

Conclusions, free full text .

Rural definition of health: a systematic literature review

Charles gessert.

Essentia Institute of Rural Health, 502 E 2nd St, Duluth, MN 55805 USA

Stephen Waring

Lisa bailey-davis.

Geisinger Center for Health Research, Danville, PA 17822 USA

Melissa Roberts

LCF Research, Albuquerque, NM 87106 USA

Jeffrey VanWormer

Marshfield Clinic Research Foundation, Marshfield, WI 54449 USA

The advent of patient-centered care challenges policy makers, health care administrators, clinicians, and patient advocates to understand the factors that contribute to effective patient activation. Improved understanding of how patients think about and define their health is needed to more effectively “activate” patients, and to nurture and support patients’ efforts to improve their health. Researchers have intimated for over 25 years that rural populations approach health in a distinct fashion that may differ from their non-rural counterparts.

We conducted a systematic review of the literature to assess the extent and strength of evidence for rural definition of health. Studies were eligible for inclusion if they were published in English, reported on original research and presented findings or commentary relevant to rural definition of health, were published over the last 40 years, and were based on observations of rural U.S., Canadian, or Australian populations. Two reviewers were assigned to each selected article and blinded to the other reviewer’s comments. For discordant reviews, a third blinded review was performed.

Of the 125 published articles identified from the literature, 34 included commentary or findings relevant to a rural definition of health. Of these studies, 6 included an urban comparison group. Few studies compared rural and urban definitions of health directly. Findings relevant to rural definition of health covered a broad range; however, good health was commonly characterized as being able to work, reciprocate in social relationships, and maintain independence.

This review largely confirmed many general characteristics on rural views of health, but also documented the extensive methodological limitations, both in terms of quantity and quality, of studies that empirically compare rural vs. urban samples. Most notably, the evidence base in this area is weakened by the frequent absence of parallel comparison groups and standardized assessment tools.

To engage and activate rural patients in their own healthcare, a better understanding of the health beliefs in rural populations is needed. This review suggests that rural residents may indeed hold distinct views on how to define health, but more rigorous studies are needed to confirm these findings.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s12889-015-1658-9) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

The passage of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) in 2010 heralded a significant shift in American health care, with increased emphasis on population health, disease prevention, and cost containment. These new areas of emphasis are prominent in several initiatives that have emerged in the wake of the ACA, including Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs), which tie provider reimbursements to measures of quality of care and reductions in the total cost of care for assigned populations of patients. The Patient Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) also emerged, charged with examining the relative health outcomes, clinical effectiveness, and appropriateness of medical treatments. Underlying these initiatives is a renewed emphasis on patient engagement in health care and, more specifically, on patient activation.

While patient engagement and patient activation are often used interchangeably, patient engagement denotes the broad involvement of patients and caregivers in all aspects of health care is based on the principle of shared responsibility [ 1 ]. Patient activation , a component of patient engagement, emphasizes patients’ willingness and ability to take independent actions to manage their health and care [ 2 ]. Patient activation has been found to be associated with better health outcomes, better health care experiences, and reduced probability of adverse markers such as emergency department use, obesity, and smoking [ 2 , 3 ]. Health care systems are encouraging primary care providers to practice patient-centered care, employing strategies that engage with and activate patients. This approach is grounded in the perspective that care should focus on patients and finding a common ground between patients and clinicians when choosing preventive and treatment care pathways.

This focus on patient-centered care challenges policy makers, health care administrators, clinicians, and patient advocates to understand the factors that contribute to effective patient activation. Individuals define “health” on the basis of their personal health-related beliefs, values and knowledge. Improved understanding of how patients think about and define their health is needed to more effectively “activate” patients, and to nurture and support patients’ efforts to improve their health.

For more than 25 years, researchers have suggested that rural populations may have a distinct view of health that differs from other non-rural populations. Seminal research in 1987 by Weinert and Long reported that rural people predominantly associated health with “the ability to work” [ 4 ], but were less likely to regard cosmetic, comfort, or life-prolonging aspects of health as important. In subsequent work, Weinert and Burman concluded that the rural “function-based definition of health” may contribute to delays in seeking health care, even in the face of grave illness [ 5 ]. In a study of the health beliefs of rural elders, Davis et al. found that subjects described health in terms of autonomy and self-reliance; they feared loss of health primarily because it could lead to “being a burden to others” [ 6 ].

These early studies indicate the need for a richer understanding of rural “frames” for health, but they lacked a direct comparison to health views from non-rural counterparts. If rural and non-rural populations indeed commonly think about or define their health differently, then efforts to engage such populations in promoting and preserving health must be better informed, particularly as health care providers increasingly focus on patient-centered care. The purpose of this study was to systematically review and critique the extent and strength of the published literature regarding how persons living in rural areas define health. In addition, we sought comparisons between rural and urban concepts of health. We were interested in findings that could guide improved patient engagement and patient activation in rural communities of the United States and similar industrialized countries. We specifically examined health values and beliefs as constructs rather than knowledge per se , as knowledge generation is better understood as a continuous process influenced by values, beliefs, motivation, skills, and context [ 7 , 8 ].

We conducted a systematic review of the literature to assess the current scientific understanding of rural definitions of health [ 9 ]. The online databases PubMed, CINAHL, PsycINFO, AnthroSource, and Sociological Abstracts were searched, followed by a manual search of the reference sections of studies identified through the online database search. Key search terms that were used were “rural population, “attitude to health,” “health behavior,” “health promotion,” “health belief,” and “health values.” Studies were eligible for inclusion if they were published in English, reported on original research, presented findings or commentary relevant to rural definitions of health, were published over the last 40 years (01/01/1972-03/31/14), and were based on observations of rural U.S., Canadian, or Australian populations. These countries were selected because of their large rural populations, including remote/frontier communities, and their access to Western health care. No restrictions were placed on sample size, research design, or length of follow-up.

For data extraction and synthesis, two reviewers were assigned to each article and blinded to the other reviewer’s comments. For discordant reviews, a third blinded review was performed. Articles were reviewed for content, methodology and rigor, with information collected on study design, characteristics of the study population, whether articles related to rural definitions of health, the definition of rural, and whether there was a comparison group (e.g., rural vs. urban). All information was captured in a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet for summarizing and comparisons. Further details on the review process are provided in Additional file 1 .

The review process identified 34 articles as having fulfilled the criterion of assessing how rural residents define health. These articles were assigned an evidence grade of A, B, or C depending on methodological quality and supporting evidence of the conclusions, based on a previously used adaptation of the American Diabetes Association's (ADA) evidence grading system [ 10 , 11 ].

Because this was a retrospective review of data from previous published studies, no patient informed consent procedures were applicable, and the study was exempt from review by the Essentia Health Institutional Review Board.

Three hundred and eighty two articles were identified using the study’s search terms; an additional fifteen articles were identified as cited references during the review process. From these, 125 articles were selected for initial review by the lead author. Ninety-one articles were excluded because they did not report on original research or were outside of the scope of the current inquiry. Thirty-four were utilized for this review; 4 were commentaries about a rural definition of health [ 4 , 12 - 14 ] and 30 contained findings relevant to a rural definition of health (see Figure 1 ). Of the latter 30 studies, 6 [ 15 - 20 ] included an urban comparison group (see Table 1 ). The remaining 24 articles [ 6 , 21 - 43 ] did not include a comparison group. Few studies compared rural and urban definitions of health directly.

PRISMA diagram of literature review process.

The 6 studies that compared findings from both rural and urban populations were of primary interest. Findings relevant to a rural definition of health covered a broad range; however, good health was commonly characterized as being able to work, reciprocate in social relationships, and maintain independence (see Table 1 ). In a focus group study by Gessert et al., rural responders were more likely to express greater willingness to accept ill health and even death as natural phenomena, whereas urban residents expressed stronger aversion to death and greater insistence on aggressive end of life care [ 15 ]. In a study to examine factors influencing individual capacity to manage coronary artery disease risk, both gender and culture (rural vs urban) were identified [ 18 ]. Rural residents expressed belief that a “work hard, eat hard” attitude kept them healthy despite the stress of their work and living in a rural environment. Additionally, rural residents would only seek a physician’s help if physical functioning was severely impaired [ 18 ]. Rural vs. urban differences were also evident in driving behavior, with rural residents more likely to participate in risky behaviors and less likely to have confidence in the utility of safety interventions [ 16 ]. Another study found that persons living in the most remote environments were more likely to hold highly stigmatized attitudes toward mental health care and these views were strongly predictive of willingness to actually seek care [ 17 ].

Comments from participants in several of the reviewed studies (see Table 1 ) centered on three traits that influenced their definition of health: independence, stoicism, and fatalism. Thorson et al. found that rural elders were less likely than urban elders to turn to health care providers for issues they considered non-urgent, regardless of how long a particular symptom had been present [ 20 ]. Hoyt et al. concluded that the agrarian ideology of self-reliance and rugged independence, coupled with a lessened sense of confidentiality and increased pressure to conform due to the smaller, more intimate nature of smaller rural environments, was not conducive to seeking mental health care, particularly for males [ 17 ]. Attitudes of rural and urban residents toward seeking medical care were similar in the Harju et al. study [ 16 ], but were somewhat incongruent with self-reported care seeking behaviors. Fear of hospitals was associated with medical adherence in rural residents and good health habits in urbanites [ 16 ].

Original research articles that did not include a comparison group (n = 29) also revealed influential themes among rural residents’ definitions of health: autonomy, avoiding medical care, and spiritual health. Rural elders participating in a study in Alberta (Canada) reported that ability to work and ability to function, irrespective of symptoms or underlying illness, was their definition of “health” [ 29 ]. In a focus group study of individuals from rural communities in Wyoming, “cowboy up to continue doing what you have to do” was a prevailing theme in responses pertaining to how participants viewed health [ 34 ]. Arcury et al., reporting from interviews of elderly residents in two rural communities in North Carolina, concluded that the residents’ definition of health integrated physical, mental, spiritual, and social aspects of health [ 21 ]. Another study of rural elderly in New Mexico reported that the common definition of health consisted of remaining autonomous and independent, avoiding contact with the health care system [ 23 ]. Lastly, from a study that included interviews of rural health providers in Colorado, one provider’s perspective, based on a 90 year old patient still engaged in ranching, was that work at any age gave patients a sense of purpose that kept them going regardless of the physical challenges of getting around [ 35 ].

This review assessed the extent and strength of evidence regarding how rural people in the United States, Canada and Australia view health differently than their urban counterparts. The overarching objective of this review was to better understand rural definitions of health and how they might be applied in health education messaging and patient engagement/ activation strategies related to disease prevention and treatment. This review largely confirmed many general characteristics previously observed on rural views of health, but also documented the extensive methodological limitations of studies that empirically compared rural vs. urban samples. The evidence in this area is particularly weakened by the routine absence of parallel comparison groups and standardized assessment tools, among other limitations.

Despite these limitations, several consistent characteristics of a rural definition of health were identified. Rural populations tend to emphasize functional aspects of health, especially the preservation of the ability to work and to fulfill (traditional) social roles. Rural people tend to frame health in terms of independence and self-sufficiency, and to accept ill health with higher degrees of stoicism and seemingly more fatalism. If more rigorous future studies can confirm these findings in rural populations, health education and patient engagement/activation programs can be better structured in ways that capitalize on the strong underlying motivations to preserve independence through good health practices. Our findings suggest that rural populations might be more responsive to health messages that emphasize physical function, independence, self-sufficiency, and the ability to reciprocate in social roles and perceived obligations.

Projects designed to improve the health of rural populations face a number of challenges. At a macro level, rural settings are not homogenous in terms of culture, economic hardship, or sense of history/community. Accordingly, findings from one rural community or similar group of rural communities may not be applicable to other rural communities or regions. Much of the previous research on rural health reported findings from primarily agrarian samples, which is an increasingly small subset of rural settings and not necessarily similar to other rural areas that rely heavily on manufacturing, forestry, or subsistence occupations. This distinction has become more pronounced in recent years with the growth of rural recreation and retirement communities, as well as other rural environments where the agrarian economy or culture has limited influence.

Individual characteristics are also important in rural health attitudes and beliefs. Several investigators reported that religious or spiritual health was an integral part of the definition of health in the rural communities studied. Socioeconomic status is recognized as a key factor in health attitudes and practices, yet few studies in the current review controlled for the socioeconomic status of rural participants. Age and length of time in the community may also be important because some of the most distinctive rural definitions of health were held by older residents (particularly those who had a life-long history of rural residence). The current review also suggests that some work histories such as lifelong farming or ranching may be associated with the more distinct views of health framed by physical function and capacity to work. A better understanding of rural attitudes and beliefs is needed to engage and activate rural residents in managing their health and care. Thus, further study of how rural residents define health will contribute to the implementation of patient-centered care in rural communities.

This study was limited principally by its focus on industrialized Western countries. Additional research is needed both to examine rural concepts of health in a wider range of settings, especially in the developing world. This study was also limited by the paucity of rigorous studies that compared rural and urban perceptions of health directly. This is a rich arena for future research.

There is increasing interest in engaging and activating patients in their own healthcare. To do so effectively in rural areas, a better understanding of the health beliefs in rural populations is needed. This review suggests that rural residents may indeed define health in their own way (e.g., functional independence). However, a formal assessment of the risk of bias was not performed in this paper because the vast majority of studies were qualitative and did not include direct comparisons between rural vs. non-rural samples. As such, selection bias remains an overshadowing concern in this collective body of literature, highlighting the need for more rigorous studies to confirm our findings. Research on rural definitions of health is further complicated by continuously changing rural lifestyles and landscapes as demographics and economic emphases shift. Despite such challenges, however, further research on rural health beliefs and attitudes is critical as American healthcare reform legislation calls for broader, systems-based strategies to improve the public’s health. To better engage and activate rural patients in their own healthcare, a better understanding of the health beliefs of targeted rural populations is needed.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge Allise Taran (Essentia Institute of Rural Health) for assisting with final preparation of the manuscript.

Abbreviations

Additional file.

Additional file 1: (138K, pdf)

Literature search and review methodology.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

All six of the authors participated actively in the conception and design of this review of the literature; the selection and review of articles from the literature; the drafting, review and editing of the manuscript; and the preparation of the final draft. All of the authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ information

CG has conducted and published research on rural health issues, including access to care in rural areas and rural-urban differences in end-of-life care. SW currently conducts and publishes research on rural health issues, particularly in the elderly. LBD has conducted and published research that observed rural and urban disparities in the prevalence of childhood obesity while controlling for socio-economic factors. PC has conducted research regarding rural and tribal communities and health (including behavioral health) outcomes and prevention strategies. MR has focused on patient satisfaction with care as part of her chronic disease and primary care outcomes research. JV has led several studies on rural disparities in preventive healthcare, as well as a large rural health improvement initiative in Minnesota.

Contributor Information

Charles Gessert, Email: moc.oohay@tressegc .

Stephen Waring, Email: [email protected] .

Lisa Bailey-Davis, Email: ude.regnisieg@sivadyeliabdl .

Pat Conway, Email: [email protected] .

Melissa Roberts, Email: gro.hcraeserfcl@streborm .

Jeffrey VanWormer, Email: [email protected] .

Full text links

Read article at publisher's site: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-015-1658-9

Citations & impact

Impact metrics, citations of article over time, alternative metrics.

Smart citations by scite.ai Smart citations by scite.ai include citation statements extracted from the full text of the citing article. The number of the statements may be higher than the number of citations provided by EuropePMC if one paper cites another multiple times or lower if scite has not yet processed some of the citing articles. Explore citation contexts and check if this article has been supported or disputed. https://scite.ai/reports/10.1186/s12889-015-1658-9

Article citations, double disparity of sexual minority status and rurality in cardiometabolic hospitalization risk: a secondary analysis using linked population-based data..

Gupta N , Cookson SR

Healthcare (Basel) , 11(21):2854, 30 Oct 2023

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 37957999 | PMCID: PMC10650143

Rural-urban disparities in health outcomes, clinical care, health behaviors, and social determinants of health and an action-oriented, dynamic tool for visualizing them.

Weeks WB , Chang JE , Pagán JA , Lumpkin J , Michael D , Salcido S , Kim A , Speyer P , Aerts A , Weinstein JN , Lavista JM

PLOS Glob Public Health , 3(10):e0002420, 03 Oct 2023

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 37788228 | PMCID: PMC10547156

Rural health and rural industries: Opportunities for partnership and action.

Scott KA , Elliott KC , Lincoln J , Flynn MA , Hill R , Hall DM

J Rural Health , 40(2):401-405, 05 Sep 2023

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 37669228

A perspective on the role of language about pain.

van Rysewyk S

Front Pain Res (Lausanne) , 4:1251676, 02 Aug 2023

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 37599863 | PMCID: PMC10433376

The impact of health literacy interventions on glycemic control and self-management outcomes among type 2 diabetes mellitus: A systematic review.

Butayeva J , Ratan ZA , Downie S , Hosseinzadeh H

J Diabetes , 15(9):724-735, 05 Jul 2023

Cited by: 2 articles | PMID: 37407516 | PMCID: PMC10509520

Similar Articles

To arrive at the top five similar articles we use a word-weighted algorithm to compare words from the Title and Abstract of each citation.

Work disability prevention in rural healthcare workers.

Franche RL , Murray EJ , Ostry A , Ratner PA , Wagner SL , Harder HG

Rural Remote Health , 10(4):1502, 16 Oct 2010

Cited by: 5 articles | PMID: 20964467

The patient experience of patient-centered communication with nurses in the hospital setting: a qualitative systematic review protocol.

Newell S , Jordan Z

JBI Database System Rev Implement Rep , 13(1):76-87, 01 Jan 2015

Cited by: 46 articles | PMID: 26447009

Student and educator experiences of maternal-child simulation-based learning: a systematic review of qualitative evidence protocol.

MacKinnon K , Marcellus L , Rivers J , Gordon C , Ryan M , Butcher D

JBI Database System Rev Implement Rep , 13(1):14-26, 01 Jan 2015

Cited by: 18 articles | PMID: 26447004

Telehealth services in rural and remote Australia: a systematic review of models of care and factors influencing success and sustainability.

Bradford NK , Caffery LJ , Smith AC

Rural Remote Health , 16(4):3808, 17 Oct 2016

Cited by: 89 articles | PMID: 27744708

The effectiveness of internet-based e-learning on clinician behavior and patient outcomes: a systematic review protocol.

Sinclair P , Kable A , Levett-Jones T

JBI Database System Rev Implement Rep , 13(1):52-64, 01 Jan 2015

Cited by: 74 articles | PMID: 26447007

Europe PMC is part of the ELIXIR infrastructure

- Systematic review

- Open access

- Published: 14 March 2012

The sustainability of new programs and innovations: a review of the empirical literature and recommendations for future research

- Shannon Wiltsey Stirman 1 , 2 , 3 ,

- John Kimberly 4 ,

- Natasha Cook 1 , 2 ,

- Amber Calloway 1 , 2 , 3 ,

- Frank Castro 1 , 2 , 3 &

- Martin Charns 2 , 5 , 6

Implementation Science volume 7 , Article number: 17 ( 2012 ) Cite this article

55k Accesses

759 Citations

39 Altmetric

Metrics details

The introduction of evidence-based programs and practices into healthcare settings has been the subject of an increasing amount of research in recent years. While a number of studies have examined initial implementation efforts, less research has been conducted to determine what happens beyond that point. There is increasing recognition that the extent to which new programs are sustained is influenced by many different factors and that more needs to be known about just what these factors are and how they interact. To understand the current state of the research literature on sustainability, our team took stock of what is currently known in this area and identified areas in which further research would be particularly helpful. This paper reviews the methods that have been used, the types of outcomes that have been measured and reported, findings from studies that reported long-term implementation outcomes, and factors that have been identified as potential influences on the sustained use of new practices, programs, or interventions. We conclude with recommendations and considerations for future research.