Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Elements of Argument

9 Toulmin Argument Model

By liza long, amy minervini, and joel gladd.

Stephen Edelston Toulmin (born March 25, 1922) was a British philosopher, author, and educator. Toulmin devoted his works to analyzing moral reasoning. He sought to develop practical ways to evaluate ethical arguments effectively. The Toulmin Model of Argumentation, a diagram containing six interrelated components, was considered Toulmin’s most influential work, particularly in the fields of rhetoric, communication, and computer science. His components continue to provide useful means for analyzing arguments.

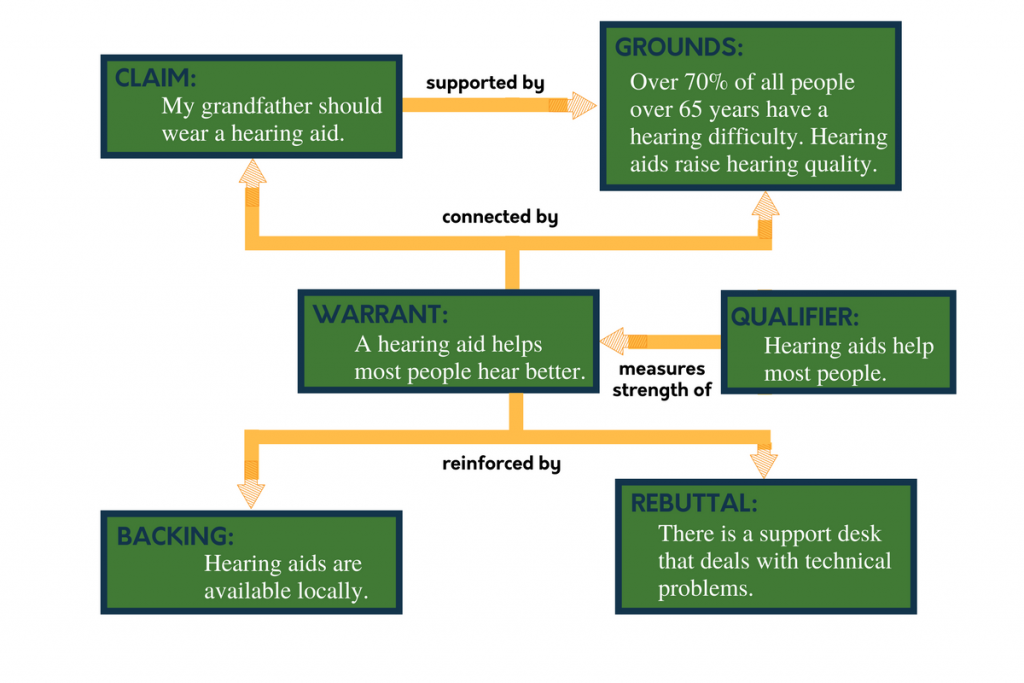

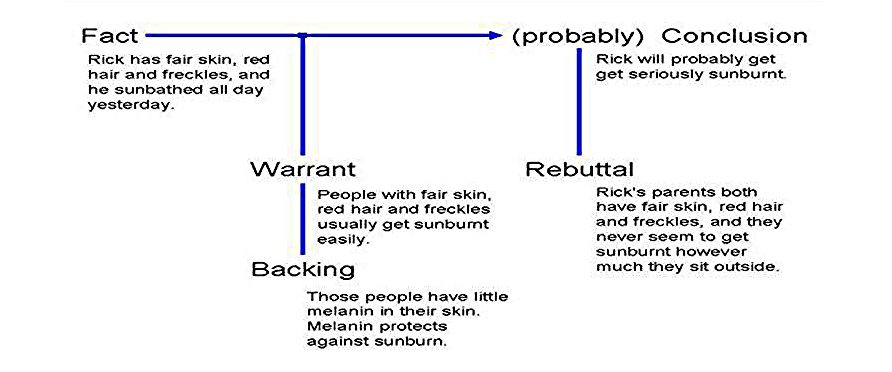

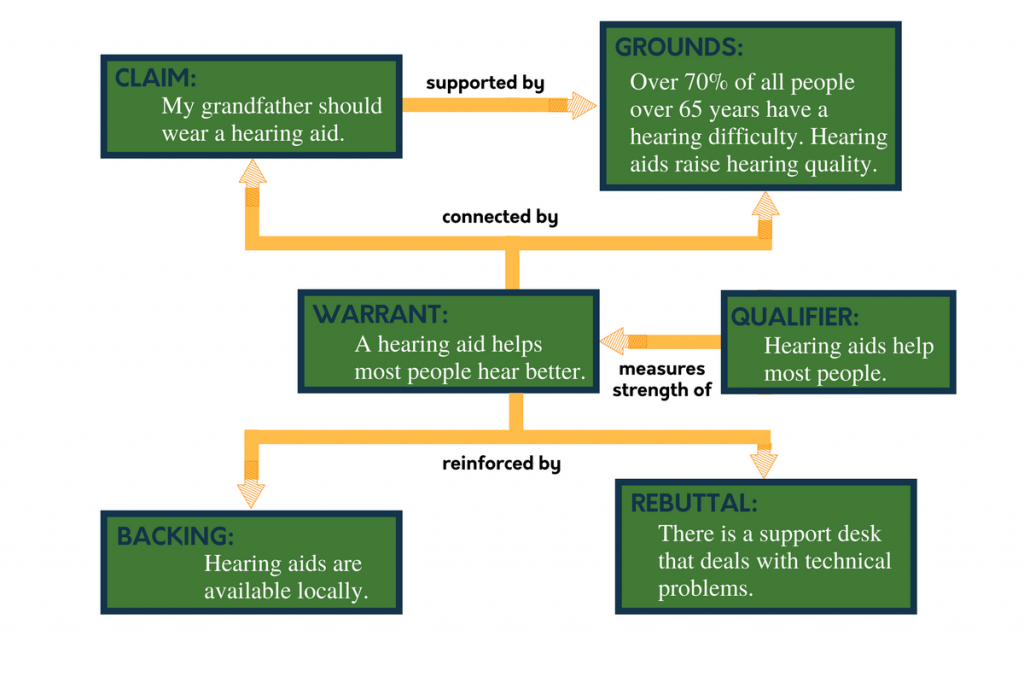

The following are the parts of a Toulmin argument (see Figure 9.1 for an example):

Claim: The claim is a statement that you are asking the other person to accept as true (i.e., a conclusion) and forms the nexus of the Toulmin argument because all the other parts relate back to the claim. The claim can include information and ideas you are asking readers to accept as true or actions you want them to accept and enact. One example of a claim is the following:

My grandfather should wear a hearing aid.

This claim both asks the reader to believe an idea and suggests an action to enact. However, like all claims, it can be challenged. Thus, a Toulmin argument does not end with a claim but also includes grounds and warrant to give support and reasoning to the claim.

Grounds: The grounds form the basis of real persuasion and include the reasoning behind the claim, data, and proof of expertise. Think of grounds as a combination of premises and support. The truth of the claim rests upon the grounds, so those grounds should be tested for strength, credibility, relevance, and reliability. The following are examples of grounds:

Over 70% of all people over 65 years have a hearing difficulty. Hearing aids raise hearing quality.

Information is usually a powerful element of persuasion, although it does affect people differently. Those who are dogmatic, logical, or rational will more likely be persuaded by factual data. Those who argue emotionally and who are highly invested in their own position will challenge it or otherwise try to ignore it. Thus, grounds can also include appeals to emotion, provided they aren’t misused. The best arguments, however, use a variety of support and rhetorical appeals.

Warrant: A warrant links data and other grounds to a claim, legitimizing the claim by showing the grounds to be relevant. The warrant may be carefully explained and explicit or unspoken and implicit. The warrant answers the question, “Why does that data mean your claim is true?” For example,

A hearing aid helps most people hear better.

The warrant may be simple, and it may also be a longer argument with additional sub-elements including those described below. Warrants may be based on logos, ethos or pathos, or values that are assumed to be shared with the listener. In many arguments, warrants are often implicit and, hence, unstated. This gives space for the other person to question and expose the warrant, perhaps to show it is weak or unfounded.

Backing: The backing for an argument gives additional support to the warrant. Backing can be confused with grounds, but the main difference is this: grounds should directly support the premises of the main argument itself, while backing exists to help the warrants make more sense. For example,

Hearing aids are available locally.

This statement works as backing because it gives credence to the warrant stated above, that a hearing aid will help most people hear better. The fact that hearing aids are readily available makes the warrant even more reasonable.

Qualifier: The qualifier indicates how the data justifies the warrant and may limit how universally the claim applies. The necessity of qualifying words comes from the plain fact that most absolute claims are ultimately false (all women want to be mothers, e.g.) because one counterexample sinks them immediately. Thus, most arguments need some sort of qualifier, words that temper an absolute claim and make it more reasonable. Common qualifiers include “most,” “usually,” “always,” or “sometimes.” For example,

Hearing aids help most people.

The qualifier “most” here allows for the reasonable understanding that rarely does one thing (a hearing aid) universally benefit all people. Another variant is the reservation, which may give the possibility of the claim being incorrect:

Unless there is evidence to the contrary, hearing aids do no harm to ears.

Qualifiers and reservations can be used to bolster weak arguments, so it is important to recognize them. They are often used by advertisers who are constrained not to lie. Thus, they slip “usually,” “virtually,” “unless,” and so on into their claims to protect against liability. While this may seem like sneaky practice, and it can be for some advertisers, it is important to note that the use of qualifiers and reservations can be a useful and legitimate part of an argument.

Rebuttal: Despite the careful construction of the argument, there may still be counterarguments that can be used. These may be rebutted either through a continued dialogue, or by pre-empting the counter-argument by giving the rebuttal during the initial presentation of the argument. For example, if you anticipated a counterargument that hearing aids, as a technology, may be fraught with technical difficulties, you would include a rebuttal to deal with that counterargument:

There is a support desk that deals with technical problems.

Any rebuttal is an argument in itself, and thus may include a claim, warrant, backing, and the other parts of the Toulmin structure.

Even if you do not wish to write an essay using strict Toulmin structure, using the Toulmin checklist can make an argument stronger. When first proposed, Toulmin based his layout on legal arguments, intending it to be used analyzing arguments typically found in the courtroom; in fact, Toulmin did not realize that this layout would be applicable to other fields until later. The first three elements–“claim,” “grounds,” and “warrant”–are considered the essential components of practical arguments, while the last three—“qualifier,” “backing,” and “rebuttal”—may not be necessary for all arguments.

Toulmin Exercise

Find an argument in essay form and diagram it using the Toulmin model. The argument can come from an Op-Ed article in a newspaper or a magazine think piece or a scholarly journal. See if you can find all six elements of the Toulmin argument. Use the structure above to diagram your article’s argument.

Attributions

“Toulmin Argument Model” by Liza Long, Amy Minervini, and Joel Gladd is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Writing Arguments in STEM Copyright © by Jason Peters; Jennifer Bates; Erin Martin-Elston; Sadie Johann; Rebekah Maples; Anne Regan; and Morgan White is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Feedback/errata.

Comments are closed.

Choose Your Test

Sat / act prep online guides and tips, 50 great argumentative essay topics for any assignment.

General Education

At some point, you’re going to be asked to write an argumentative essay. An argumentative essay is exactly what it sounds like—an essay in which you’ll be making an argument, using examples and research to back up your point.

But not all argumentative essay topics are created equal. Not only do you have to structure your essay right to have a good impact on the reader, but even your choice of subject can impact how readers feel about your work.

In this article, we’ll cover the basics of writing argumentative essays, including what argumentative essays are, how to write a good one, and how to pick a topic that works for you. Then check out a list of argumentative essay ideas to help you get started.

What Is an Argumentative Essay?

An argumentative essay is one that makes an argument through research. These essays take a position and support it through evidence, but, unlike many other kinds of essays, they are interested in expressing a specific argument supported by research and evidence.

A good argumentative essay will be based on established or new research rather than only on your thoughts and feelings. Imagine that you’re trying to get your parents to raise your allowance, and you can offer one of two arguments in your favor:

You should raise my allowance because I want you to.

You should raise my allowance because I’ve been taking on more chores without complaining.

The first argument is based entirely in feelings without any factual backup, whereas the second is based on evidence that can be proven. Your parents are more likely to respond positively to the second argument because it demonstrates that you have done something to earn the increased allowance. Similarly, a well-researched and reasoned argument will show readers that your point has a basis in fact, not just feelings.

The standard five-paragraph essay is common in writing argumentative essays, but it’s not the only way to write one. An argumentative essay is typically written in one of two formats, the Toulmin model or the Rogerian model.

The Toulmin model is the most common, comprised of an introduction with a claim (otherwise known as a thesis), with data to support it. This style of essay will also include rebuttals, helping to strengthen your argument by anticipating counterarguments.

The Rogerian model analyzes two sides of an argument and reaches a conclusion after weighing the strengths and weaknesses of each.

Both essay styles rely on well-reasoned logic and supporting evidence to prove a point, just in two different ways.

The important thing to note about argumentative essays as opposed to other kinds of essays is that they aim to argue a specific point rather than to explain something or to tell a story. While they may have some things in common with analytical essays, the primary difference is in their objective—an argumentative essay aims to convince someone of something, whereas an analytical essay contextualizes a topic with research.

What Makes a Good Argumentative Essay?

To write an effective argumentative essay, you need to know what a good one looks like. In addition to a solid structure, you’ll need an argument, a strong thesis, and solid research.

An Argument

Unlike other forms of essays, you are trying to convince your reader of something. You’re not just teaching them a concept or demonstrating an idea—you’re constructing an argument to change the readers’ thinking.

You’ll need to develop a good argument, which encompasses not just your main point, but also all the pieces that make it up.

Think beyond what you are saying and include how you’re saying it. How will you take an idea and turn it into a complex and well thought out argument that is capable of changing somebody’s mind?

A Strong Thesis

The thesis is the core of your argument. What specific message are you trying to get across? State that message in one sentence, and that will be your thesis.

This is the foundation on which your essay is built, so it needs to be strong and well-reasoned. You need to be able to expand on it with facts and sources, not just feelings.

A good argumentative essay isn’t just based on your individual thoughts, but research. That can be citing sources and other arguments or it can mean direct research in the field, depending on what your argument is and the context in which you are arguing it.

Be prepared to back your thesis up with reporting from scientific journals, newspapers, or other forms of research. Having well-researched sources will help support your argument better than hearsay or assumptions. If you can’t find enough research to back up your point, it’s worth reconsidering your thesis or conducting original research, if possible.

How to Come Up With an Argumentative Essay Topic

Sometimes you may find yourself arguing things you don’t necessarily believe. That’s totally fine—you don’t actually have to wholeheartedly believe in what you’re arguing in order to construct a compelling argument.

However, if you have free choice of topic, it’s a good idea to pick something you feel strongly about. There are two key components to a good argumentative essay: a strong stance, and an assortment of evidence. If you’re interested and feel passionate about the topic you choose, you'll have an easier time finding evidence to support it, but it's the evidence that's most important.

So, to choose a topic, think about things you feel strongly about, whether positively or negatively. You can make a list of ideas and narrow those down to a handful of things, then expand on those ideas with a few potential points you want to hit on.

For example, say you’re trying to decide whether you should write about how your neighborhood should ban weed killer, that your school’s lunch should be free for all students, or that the school day should be cut by one hour. To decide between these ideas, you can make a list of three to five points for each that cover the different evidence you could use to support each point.

For the weed killer ban, you could say that weed killer has been proven to have adverse impacts on bees, that there are simple, natural alternatives, and that weeds aren’t actually bad to have around. For the free lunch idea, you could suggest that some students have to go hungry because they can’t afford lunch, that funds could be diverted from other places to support free lunch, and that other items, like chips or pizza, could be sold to help make up lost revenue. And for the school day length example, you could argue that teenagers generally don’t get enough sleep, that you have too much homework and not enough time to do it, and that teenagers don’t spend enough time with their families.

You might find as you make these lists that some of them are stronger than others. The more evidence you have and the stronger you feel that that evidence is, the better the topic. Of course, if you feel that one topic may have more evidence but you’d rather not write about it, it’s okay to pick another topic instead. When you’re making arguments, it can be much easier to find strong points and evidence if you feel passionate about our topic than if you don't.

50 Argumentative Essay Topic Ideas

If you’re struggling to come up with topics on your own, read through this list of argumentative essay topics to help get you started!

- Should fracking be legal?

- Should parents be able to modify their unborn children?

- Do GMOs help or harm people?

- Should vaccinations be required for students to attend public school?

- Should world governments get involved in addressing climate change?

- Should Facebook be allowed to collect data from its users?

- Should self-driving cars be legal?

- Is it ethical to replace human workers with automation?

- Should there be laws against using cell phones while driving?

- Has the internet positively or negatively impacted human society?

- Should college athletes be paid for being on sports teams?

- Should coaches and players make the same amount of money?

- Should sports be segregated by gender?

- Should the concept of designated hitters in baseball be abolished?

- Should US sports take soccer more seriously?

- Should religious organizations have to pay taxes?

- Should religious clubs be allowed in schools?

- Should “one nation under God” be in the pledge of allegiance?

- Should religion be taught in schools?

- Should clergy be allowed to marry?

- Should minors be able to purchase birth control without parental consent?

- Should the US switch to single-payer healthcare?

- Should assisted suicide be legal?

- Should dietary supplements and weight loss items like teas be allowed to advertise through influencers?

- Should doctors be allowed to promote medicines?

Government/Politics

- Is the electoral college an effective system for modern America?

- Should Puerto Rico become a state?

- Should voter registration be automatic?

- Should people in prison be allowed to vote?

- Should Supreme Court justices be elected?

- Should sex work be legalized?

- Should Columbus Day be replaced with Indigenous Peoples’ Day?

- Should the death penalty be legal?

- Should animal testing be allowed?

- Should drug possession be decriminalized?

- Should unpaid internships be legal?

- Should minimum wage be increased?

- Should monopolies be allowed?

- Is universal basic income a good idea?

- Should corporations have a higher or lower tax rate?

- Are school uniforms a good idea?

- Should PE affect a student’s grades?

- Should college be free?

- Should Greek life in colleges be abolished?

- Should students be taught comprehensive sex ed?

Arts/Culture

- Should graffiti be considered art or vandalism?

- Should books with objectionable words be banned?

- Should content on YouTube be better regulated?

- Is art education important?

- Should art and music sharing online be allowed?

How to Argue Effectively

A strong argument isn’t just about having a good point. If you can’t support that point well, your argument falls apart.

One of the most important things you can do in writing a strong argumentative essay is organizing well. Your essay should have a distinct beginning, middle, and end, better known as the introduction, body and opposition, and conclusion.

This example follows the Toulmin model—if your essay follows the Rogerian model, the same basic premise is true, but your thesis will instead propose two conflicting viewpoints that will be resolved through evidence in the body, with your conclusion choosing the stronger of the two arguments.

Introduction

Your hook should draw the reader’s interest immediately. Questions are a common way of getting interest, as well as evocative language or a strong statistic

Don’t assume that your audience is already familiar with your topic. Give them some background information, such as a brief history of the issue or some additional context.

Your thesis is the crux of your argument. In an argumentative essay, your thesis should be clearly outlined so that readers know exactly what point you’ll be making. Don’t explain all your evidence in the opening, but do take a strong stance and make it clear what you’ll be discussing.

Your claims are the ideas you’ll use to support your thesis. For example, if you’re writing about how your neighborhood shouldn’t use weed killer, your claim might be that it’s bad for the environment. But you can’t just say that on its own—you need evidence to support it.

Evidence is the backbone of your argument. This can be things you glean from scientific studies, newspaper articles, or your own research. You might cite a study that says that weed killer has an adverse effect on bees, or a newspaper article that discusses how one town eliminated weed killer and saw an increase in water quality. These kinds of hard evidence support your point with demonstrable facts, strengthening your argument.

In your essay, you want to think about how the opposition would respond to your claims and respond to them. Don’t pick the weakest arguments, either— figure out what other people are saying and respond to those arguments with clearly reasoned arguments.

Demonstrating that you not only understand the opposition’s point, but that your argument is strong enough to withstand it, is one of the key pieces to a successful argumentative essay.

Conclusions are a place to clearly restate your original point, because doing so will remind readers exactly what you’re arguing and show them how well you’ve argued that point.

Summarize your main claims by restating them, though you don’t need to bring up the evidence again. This helps remind readers of everything you’ve said throughout the essay.

End by suggesting a picture of a world in which your argument and action are ignored. This increases the impact of your argument and leaves a lasting impression on the reader.

A strong argumentative essay is one with good structure and a strong argument , but there are a few other things you can keep in mind to further strengthen your point.

When you’re crafting an argument, it can be easy to get distracted by all the information and complications in your argument. It’s important to stay focused—be clear in your thesis and home in on claims that directly support that thesis.

Be Rational

It’s important that your claims and evidence be based in facts, not just opinion. That’s why it’s important to use reliable sources based in science and reporting—otherwise, it’s easy for people to debunk your arguments.

Don’t rely solely on your feelings about the topic. If you can’t back a claim up with real evidence, it leaves room for counterarguments you may not anticipate. Make sure that you can support everything you say with clear and concrete evidence, and your claims will be a lot stronger!

What’s Next?

No matter what kind of essay you're writing, a strong plan will help you have a bigger impact. This guide to writing a college essay is a great way to get started on your essay organizing journey!

Brushing up on your essay format knowledge to prep for the SAT? Check out this list of SAT essay prompts to help you kickstart your studying!

A bunch of great essay examples can help you aspire to greatness, but bad essays can also be a warning for what not to do. This guide to bad college essays will help you better understand common mistakes to avoid in essay writing!

Melissa Brinks graduated from the University of Washington in 2014 with a Bachelor's in English with a creative writing emphasis. She has spent several years tutoring K-12 students in many subjects, including in SAT prep, to help them prepare for their college education.

Ask a Question Below

Have any questions about this article or other topics? Ask below and we'll reply!

Improve With Our Famous Guides

- For All Students

The 5 Strategies You Must Be Using to Improve 160+ SAT Points

How to Get a Perfect 1600, by a Perfect Scorer

Series: How to Get 800 on Each SAT Section:

Score 800 on SAT Math

Score 800 on SAT Reading

Score 800 on SAT Writing

Series: How to Get to 600 on Each SAT Section:

Score 600 on SAT Math

Score 600 on SAT Reading

Score 600 on SAT Writing

Free Complete Official SAT Practice Tests

What SAT Target Score Should You Be Aiming For?

15 Strategies to Improve Your SAT Essay

The 5 Strategies You Must Be Using to Improve 4+ ACT Points

How to Get a Perfect 36 ACT, by a Perfect Scorer

Series: How to Get 36 on Each ACT Section:

36 on ACT English

36 on ACT Math

36 on ACT Reading

36 on ACT Science

Series: How to Get to 24 on Each ACT Section:

24 on ACT English

24 on ACT Math

24 on ACT Reading

24 on ACT Science

What ACT target score should you be aiming for?

ACT Vocabulary You Must Know

ACT Writing: 15 Tips to Raise Your Essay Score

How to Get Into Harvard and the Ivy League

How to Get a Perfect 4.0 GPA

How to Write an Amazing College Essay

What Exactly Are Colleges Looking For?

Is the ACT easier than the SAT? A Comprehensive Guide

Should you retake your SAT or ACT?

When should you take the SAT or ACT?

Stay Informed

Get the latest articles and test prep tips!

Looking for Graduate School Test Prep?

Check out our top-rated graduate blogs here:

GRE Online Prep Blog

GMAT Online Prep Blog

TOEFL Online Prep Blog

Holly R. "I am absolutely overjoyed and cannot thank you enough for helping me!”

Table of Contents

Ai, ethics & human agency, collaboration, information literacy, writing process, toulmin argument.

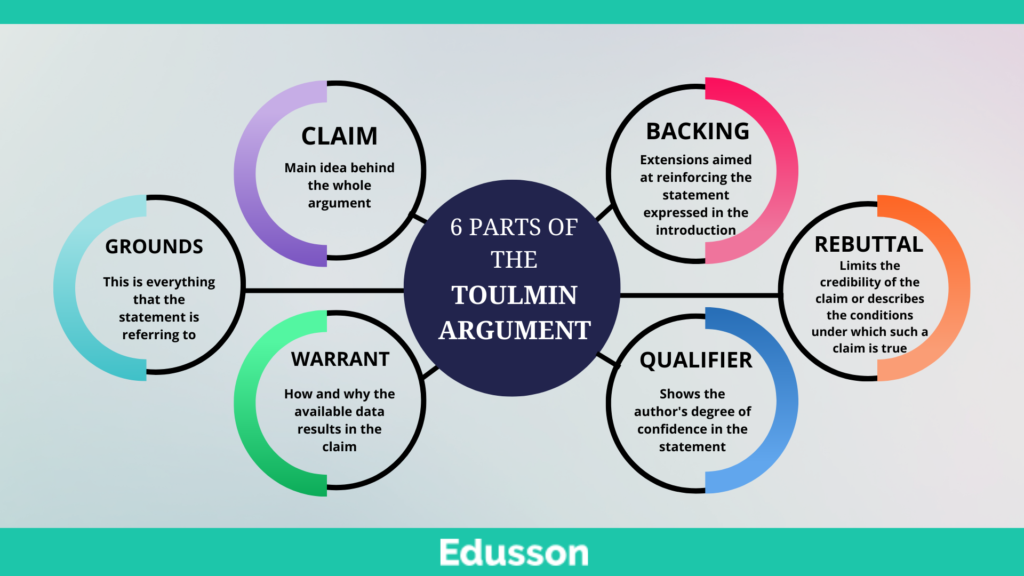

Stephen Toulmin's model of argumentation theorizes six rhetorical moves constitute argumentation: Evidence , Warrant , Claim , Qualifier , Rebuttal, and Backing . Learn to develop clear, persuasive arguments and to critique the arguments of others. By learning this model, you'll gain the skills to construct clearer, more persuasive arguments and critically assess the arguments presented by others, enhancing your writing and analytical abilities in academic and professional settings.

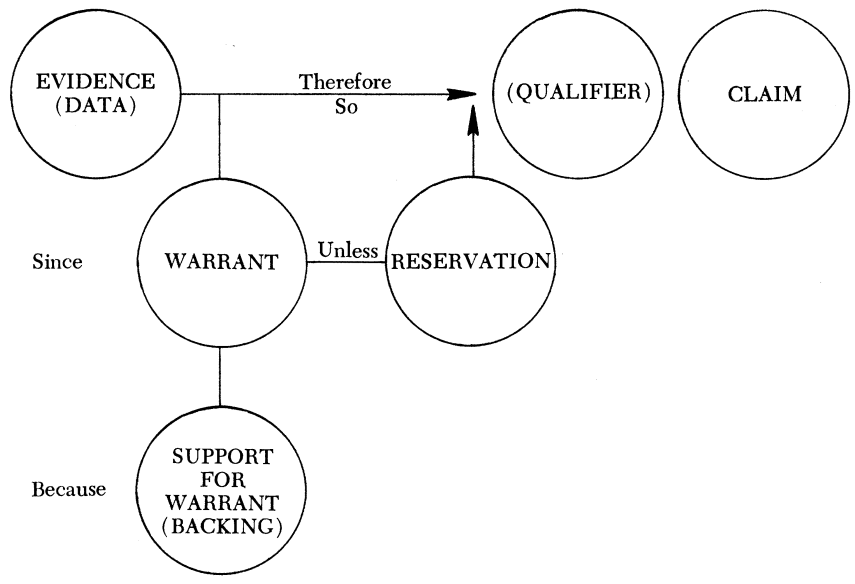

Stephen Toulmin’s (1958) model of argument conceptualizes argument as a series of six rhetorical moves :

- Data, Evidence

- Counterargument, Counterclaim

- Reservation/Rebuttal

Related Concepts

Evidence ; Persuasion; Rhetorical Analysis ; Rhetorical Reasoning

Why Does Toulmin Argument Matter?

Toulmin’s model of argumentation is particularly valuable for college students because it provides a structured framework for analyzing and constructing arguments, skills that are essential across various academic disciplines and real-world situations.

By understanding Toulmin’s components—claim, evidence, warrant, backing, qualifier, and rebuttal—students can develop more coherent, persuasive arguments and critically evaluate the arguments of others. This model encourages students to think deeply about the logic and effectiveness of their argumentation, emphasizing the importance of supporting claims with solid evidence and reasoning. Additionally, familiarity with Toulmin’s model prepares students for scenarios involving critical analysis and debate, whether in writing essays, participating in discussions, or presenting research.

By mastering this model, students enhance their ability to communicate effectively, a crucial skill for academic success and professional advancement.

When should writers or speakers consider Toulmin’s model of argument?

Toulmin’s model of argument works especially well in situations where disputes are being reviewed by a third party — such as judge, an arbitrator, or evaluation committee.

Declarative knowledge of Toulmin Argument helps with

- inventing or developing your own arguments (even if you’re developing a Rogerian or Aristotelian argument )

- critiquing your arguments or the arguments of others.

Summary of Stephen Toulmin’s Model of Argument

The three essential components of argument.

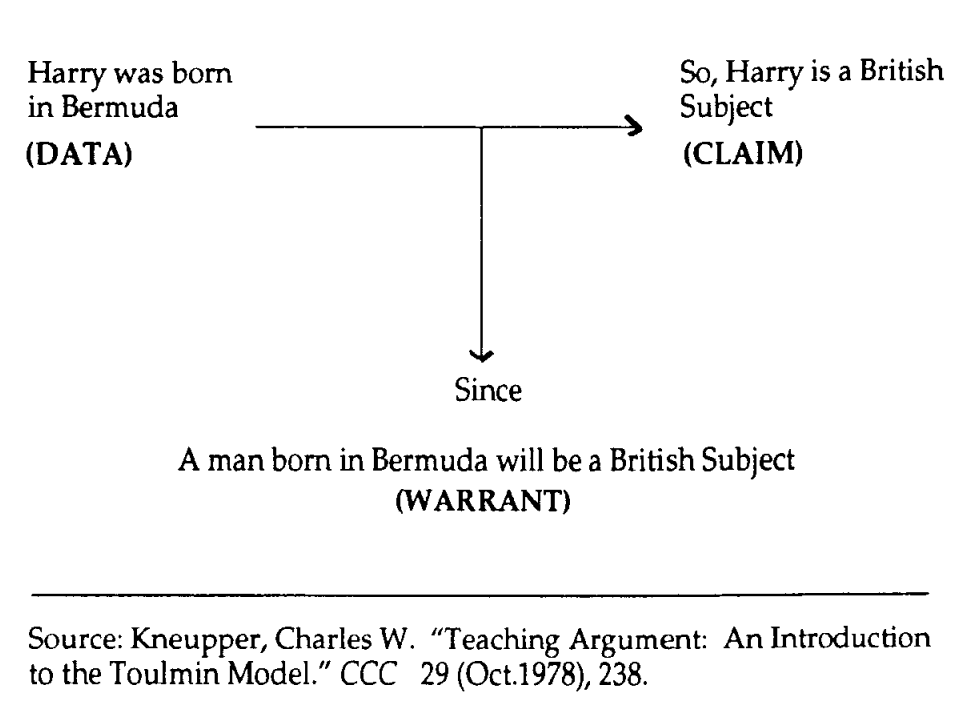

Stephen Toulmin’s model of argument posits the three essential elements of an argument are

- Data (aka a Fact or Evidence)

- Warrant (which the writer, speaker, knowledge worker . . . may imply rather than explicitly state).

Toulmin’s model presumes data, matters of fact and opinion, must be supplied as evidence to support a claim. The claim focuses the discourse by explicitly stating the desired conclusion of the argument.

In turn, a warrant, the third essential component of an argument, provides the reasoning that links the data to the claim.

The example in Figure 1 demonstrates the abstract, hypothetical linking between a claim and data that a warrant provides. Prior to this link–that. people born in Bermuda are British–the claim that Harry is a British subject because he was born in Bermuda is unsubstantiated.

The 6 Elements of Successful Argument

While the argument presented in Figure 1 is a simple one, life is not always simple.

In situations where people are likely to dispute the application of a warrant to data, you may need to develop backing for your warrants. o account for the conflicting desires and assumptions of an audience, Toulmin identifies a second triad of components that may not be used:

- Reservation

- Qualification.

Charles Kneupper provides us with the following diagram of these six elements (238):

*This article is adapted from Moxley, Joseph M. “ Reinventing the Wheel or Teaching the Basics ?: College Writers ‘ Knowledge of Argumentation .” Composition. Studies 21.2 (1993): 3-15.

Kneupper, C. W. (1978). Teaching Argument: An Introduction to the Toulmin Model. College Composition and Communication , 29 (3), 237–241. https://doi.org/10.2307/356935

Moxley, Joseph M. “ Reinventing the Wheel or Teaching the Basics ?: College Writers ‘ Knowledge of Argumentation .” Composition. Studies 21.2 (1993): 3-15.

Toulmin, S. (1969). The Uses of Argument , Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press

Brevity - Say More with Less

Clarity (in Speech and Writing)

Coherence - How to Achieve Coherence in Writing

Flow - How to Create Flow in Writing

Inclusivity - Inclusive Language

The Elements of Style - The DNA of Powerful Writing

Suggested Edits

- Please select the purpose of your message. * - Corrections, Typos, or Edits Technical Support/Problems using the site Advertising with Writing Commons Copyright Issues I am contacting you about something else

- Your full name

- Your email address *

- Page URL needing edits *

- Email This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

Other Topics:

Citation - Definition - Introduction to Citation in Academic & Professional Writing

- Joseph M. Moxley

Explore the different ways to cite sources in academic and professional writing, including in-text (Parenthetical), numerical, and note citations.

Collaboration - What is the Role of Collaboration in Academic & Professional Writing?

Collaboration refers to the act of working with others or AI to solve problems, coauthor texts, and develop products and services. Collaboration is a highly prized workplace competency in academic...

Genre may reference a type of writing, art, or musical composition; socially-agreed upon expectations about how writers and speakers should respond to particular rhetorical situations; the cultural values; the epistemological assumptions...

Grammar refers to the rules that inform how people and discourse communities use language (e.g., written or spoken English, body language, or visual language) to communicate. Learn about the rhetorical...

Information Literacy - Discerning Quality Information from Noise

Information Literacy refers to the competencies associated with locating, evaluating, using, and archiving information. In order to thrive, much less survive in a global information economy — an economy where information functions as a...

Mindset refers to a person or community’s way of feeling, thinking, and acting about a topic. The mindsets you hold, consciously or subconsciously, shape how you feel, think, and act–and...

Rhetoric: Exploring Its Definition and Impact on Modern Communication

Learn about rhetoric and rhetorical practices (e.g., rhetorical analysis, rhetorical reasoning, rhetorical situation, and rhetorical stance) so that you can strategically manage how you compose and subsequently produce a text...

Style, most simply, refers to how you say something as opposed to what you say. The style of your writing matters because audiences are unlikely to read your work or...

The Writing Process - Research on Composing

The writing process refers to everything you do in order to complete a writing project. Over the last six decades, researchers have studied and theorized about how writers go about...

Writing Studies

Writing studies refers to an interdisciplinary community of scholars and researchers who study writing. Writing studies also refers to an academic, interdisciplinary discipline – a subject of study. Students in...

Featured Articles

Academic Writing – How to Write for the Academic Community

Professional Writing – How to Write for the Professional World

Credibility & Authority – How to Be Credible & Authoritative in Speech & Writing

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

7 Toulmin Argument Model

In simplified terms this is the argument of “I am right — and here is why.” In this model of argument, the arguer creates a claim, also referred to as a thesis, that states the idea you are asking the audience to accept as true and then supports it with evidence and reasoning. The Toulmin argument goes further, though, than that basic model with a claim and support. It adds some additional parts such as rebuttals, warrants, backing, and qualifiers to create a water-tight argument.

Preview the Toulmin Argument Model

Stephen Toulmin and His Six-Part Argument Model

Stephen Edelston Toulmin (born March 25, 1922) was a British philosopher, author, and educator. Toulmin devoted his works to analyzing moral reasoning. He sought to develop practical ways to evaluate ethical arguments effectively. The Toulmin Model of Argumentation, a diagram containing six interrelated components, was considered Toulmin’s most influential work, particularly in the fields of rhetoric, communication, and computer science. His components continue to provide useful means for analyzing arguments.

Figure 8.1 “Toulmin Argument”

The following are the parts of a Toulmin argument:

1. Claim : The claim is a statement that you are asking the other person to accept as true (i.e., a conclusion) and forms the nexus of the Toulmin argument because all the other parts relate back to the claim. The claim can include information and ideas you are asking readers to accept as true or actions you want them to accept and enact. One example of a claim:

My grandfather should wear a hearing aid.

This claim both asks the reader to believe an idea and suggests an action to enact. However, like all claims, it can be challenged. Thus, a Toulmin argument does not end with a claim but also includes grounds and warrant to give support and reasoning to the claim.

2. Grounds : The grounds form the basis of real persuasion and includes the reasoning behind the claim, data, and proof of expertise. Think of grounds as a combination of premises and support . The truth of the claim rests upon the grounds, so those grounds should be tested for strength, credibility, relevance, and reliability. The following are examples of grounds:

Over 70% of all people over 65 years have a hearing difficulty.

Hearing aids raise hearing quality.

Information is usually a powerful element of persuasion, although it does affect people differently. Those who are dogmatic, logical, or rational will more likely be persuaded by factual data. Those who argue emotionally and who are highly invested in their own position will challenge it or otherwise try to ignore it. Thus, grounds can also include appeals to emotion, provided they aren’t misused. The best arguments, however, use a variety of support and rhetorical appeals.

3. Warrant : A warrant links data and other grounds to a claim, legitimizing the claim by showing the grounds to be relevant . The warrant may be carefully explained and explicit or unspoken and implicit. The warrant answers the question, “Why does that data mean your claim is true?” For example,

A hearing aid helps most people hear better.

The warrant may be simple, and it may also be a longer argument with additional sub-elements including those described below. Warrants may be based on logos , ethos or pathos , or values that are assumed to be shared with the listener. In many arguments, warrants are often implicit and, hence, unstated. This gives space for the other person to question and expose the warrant, perhaps to show it is weak or unfounded.

4. Backing : The backing for an argument gives additional support to the warrant. Backing can be confused with grounds, but the main difference is this: Grounds should directly support the premises of the main argument itself, while backing exists to help the warrants make more sense. For example,

Hearing aids are available locally.

This statement works as backing because it gives credence to the warrant stated above, that a hearing aid will help most people hear better. The fact that hearing aids are readily available makes the warrant even more reasonable.

5. Qualifier : The qualifier indicates how the data justifies the warrant and may limit how universally the claim applies. The necessity of qualifying words comes from the plain fact that most absolute claims are ultimately false (all women want to be mothers, e.g.) because one counterexample sinks them immediately. Thus, most arguments need some sort of qualifier, words that temper an absolute claim and make it more reasonable. Common qualifiers include “most,” “usually,” “always,” or “sometimes.” For example,

Hearing aids help most people.

The qualifier “most” here allows for the reasonable understanding that rarely does one thing (a hearing aid) universally benefit all people. Another variant is the reservation, which may give the possibility of the claim being incorrect:

Unless there is evidence to the contrary, hearing aids do no harm to ears.

Qualifiers and reservations can be used to bolster weak arguments, so it is important to recognize them. They are often used by advertisers who are constrained not to lie. Thus, they slip “usually,” “virtually,” “unless,” and so on into their claims to protect against liability. While this may seem like sneaky practice, and it can be for some advertisers, it is important to note that the use of qualifiers and reservations can be a useful and legitimate part of an argument.

6. Rebuttal : Despite the careful construction of the argument, there may still be counterarguments that can be used. These may be rebutted either through a continued dialogue, or by pre-empting the counter-argument by giving the rebuttal during the initial presentation of the argument. For example, if you anticipated a counterargument that hearing aids, as a technology, may be fraught with technical difficulties, you would include a rebuttal to deal with that counterargument:

There is a support desk that deals with technical problems.

Any rebuttal is an argument in itself, and thus may include a claim, warrant, backing, and the other parts of the Toulmin structure.

When to Use the Toulmin Argument Model

Overall, the Toulmin Argument Model may be used to create a strong, persuasive argument — and it can be used to analyze and examine an argument. You may use this approach for a speech, academic paper, or online argument that you are creating. This approach can help you to create a sound, persuasive argument. You also may use this model to analyze an argument that you read, watch, or hear. The model can help you to identify missing parts in an argument. Sometimes, an argument “feels” wrong, but this approach can help you to identify why it is flawed.

Even if you do not wish to write an essay using strict Toulmin structure, using the Toulmin checklist can make an argument stronger. When first proposed, Toulmin based his layout on legal arguments, intending it to be used analyzing arguments typically found in the courtroom; in fact, Toulmin did not realize that this layout would be applicable to other fields until later. The first three elements–“claim,” “grounds,” and “warrant”–are considered the essential components of practical arguments, while the last three—“qualifier,” “backing,” and “rebuttal”—may not be necessary for all arguments.

Find an argument in essay form and diagram it using the Toulmin model. The argument can come from an Op-Ed article in a newspaper or a magazine think piece or a scholarly journal. See if you can find all six elements of the Toulmin argument. Use the structure above to diagram your article’s argument.

Key Takeaways

- Toulmin’s Argument Model —six interrelated components used to diagram an argument.

- A Toulmin Argument may be used in academic writing or to persuade someone online.

- A Toulmin Argument model can be used to analyze an argument you read

- A Toulmin Argument model also can be used to create an argument when you are writing.

Chapter Attribution

The material in this chapter is a derivative (including a short section written by Liona Burnham) of the following sources:

“The Toulmin Argument Model” in Let’s Get Writing! by Kirsten DeVries is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License .

“Toulmin Argument” in Writing and Rhetoric by Heather Hopkins Bowers; Anthony Ruggiero; and Jason Saphara is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License .

Image Attributions

Figure 7.1: “Toulmin Argument,” Kalyca Schultz, Virginia Western Community College, CC-0

Upping Your Argument and Research Game Copyright © 2022 by Liona Burnham is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Arguing on the Toulmin Model

New Essays in Argument Analysis and Evaluation

- © 2006

- David Hitchcock 0 ,

- Bart Verheij 1

Department of Philosophy, Mc Master University, Hamilton, Canada

You can also search for this editor in PubMed Google Scholar

Artificial Intelligence, Rijksuniversiteit Groningen, Groningen, The Netherlands

- The only book-length comprehensive study of Stephen Toulmin’s influential model for the layout of arguments

- New essays on argument analysis and evaluation by 27 scholars from 10 countries in the fields of artificial intelligence, philosophy, psychology and speech communication

- Novel contributions to the theory of non-formal inferences, to the theory of defeaters, to the debate over relativism in argument evaluation, and to the classification of the components of arguments

Part of the book series: Argumentation Library (ARGA, volume 10)

54k Accesses

160 Citations

20 Altmetric

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this book

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Other ways to access

Licence this eBook for your library

Institutional subscriptions

Table of contents (25 chapters)

Front matter, introduction.

- David Hitchcock, Bart Verheij

Reasoning in Theory and Practice

- Stephen E. Toulmin

A Citation-Based Reflection on Toulmin and Argument

- Ronald P. Loui

Complex Cases and Legitimation Inference: Extending the Toulmin Model to Deliberative Argument in Controversy

- G. Thomas Goodnight

A Metamathematical Extension of the Toulmin Agenda

- Mark Weinstein

Toulmin's Model of Argument and the Question of Relativism

- Lilian Bermejo-Luque

Systematizing Toulmin's Warrants: An Epistemic Approach

- James B. Freeman

Warranting Arguments, the Virtue of Verb

- James F. Klumpp

Evaluating Inferences: The Nature and Role of Warrants

- Robert C. Pinto

- Robert H. Ennis

The Voice of the Other: A Dialogico-Rhetorical Understanding of Opponent and of Toulmin's Rebuttal

- Wouter H. Slob

Evaluating Arguments Based on Toulmin's Scheme

Bart Verheij

Good Reasoning on the Toulmin Model

David Hitchcock

The Fluidity of Warrants: Using the Toulmin Model to Analyse Practical Discourse

Artificial intelligence & law, logic and argument schemes.

- Henry Prakken

Multiple Warrants in Practical Reasoning

- Christian Kock

The Quest for Rationalism without Dogmas in Leibniz and Toulmin

- Txetxu Ausín

From Arguments to Decisions: Extending the Toulmin View

- John Fox, Sanjay Modgil

Using Toulmin Argumentation to Support Dispute Settlement in Discretionary Domains

- John Zeleznikow

- Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz

- artificial intelligence

- communication

- formal logic

- intelligence

About this book

Editors and affiliations, bibliographic information.

Book Title : Arguing on the Toulmin Model

Book Subtitle : New Essays in Argument Analysis and Evaluation

Editors : David Hitchcock, Bart Verheij

Series Title : Argumentation Library

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4020-4938-5

Publisher : Springer Dordrecht

eBook Packages : Humanities, Social Sciences and Law , Philosophy and Religion (R0)

Copyright Information : Springer Science+Business Media B.V. 2006

Hardcover ISBN : 978-1-4020-4937-8 Published: 26 January 2007

Softcover ISBN : 978-90-481-7233-7 Published: 19 November 2010

eBook ISBN : 978-1-4020-4938-5 Published: 24 January 2007

Series ISSN : 1566-7650

Series E-ISSN : 2215-1907

Edition Number : 1

Number of Pages : VIII, 440

Topics : Epistemology , Artificial Intelligence , Logic

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

The Toulmin Model of Argument

The Toulmin Model of Argument Podcast

The toulmin model of argument transcript.

Greetings everyone. I am Kurtis Clements with an effective writing podcast. In this episode, I am going to discuss argument and structure and take a look at the Toulmin Model of Argument.

Let’s start with a practical question: What exactly is meant by argument? For some, the word argument conjures up a heated verbal disagreement between two people replete with shouting and arm-waving and general unpleasantness. We’ve all had those kinds of arguments. In the academic world, however, argument tends to be much more civilized, meaning nothing more than one’s opinion on a topic or issue. In a very real sense, just about everything’s an argument. Now, one’s opinion, or argument, needs to be thoughtfully presented and developed for an audience who may not share the writer’s view. Credible evidence needs to be integrated. Sound logic needs to be employed. And steps need to be taken to convince an audience that what the writer claims to be true is, in fact, true, or at least it has merit and is worthy of consideration.

I know the analogy has been used before, but a good way to think about writing argument is to image that you are a lawyer arguing your case before a jury. In such a scenario, you would make a claim to the jury—not guilty!—and carefully build your case by presenting one compelling piece of evidence after another. You are trying to argue your case and persuade the jury to believe your client is innocent or that there is a reasonable doubt that he is guilty. Makes sense, right? Ok, so how do you do it? How do you convince an audience that what you claim to be true is, in fact, true? While there is truth to the saying that it’s easier said than done, with careful attention to the nature of argument and a good plan of development, you can learn how to make a good argument.

First things first—you have to be aware of the language of argument. The wording needs to be such that it is clear to your audience that you have a strong view about a particular issue and that you want others to see the value in what you have to say. You need to be aware of the words you use and how you express your ideas to be effective.

Let’s look at an example of a thesis for an argumentative essay:

Statistics show that many homeless people have mental instabilities that are not being treated which often leads to violence.

Thoughts? Good, bad, somewhere in between? The sentence does make a declarative statement, but is it an argumentative statement? What words in the sentence suggest an argument? Does the sentence get at what the writer is going to try to prove? And the answer is: This thesis is a start, but as is, it does not yet express a focused and specific argument.

How about this thesis: The city of Lewiston, Maine, needs to provide better services for its homeless population because many homeless people have medical and mental conditions that are going untreated; some suffer from psychological disorders that could put themselves and others at risk, and many do not have the skills or resources to make them more employable.

Is this thesis statement better? Well, it’s certainly more specific (as well as longer). What does this thesis claim to be true about its subject? The claim needs to be clear and it needs to use language that reflects the purpose is to argue. The claim this thesis makes is that Lewiston, Maine, needs to provide better services for its homeless population. Note the word “needs,” which in this context suggests that something is not being done that should. Is the statement an outright fact or is it someone’s opinion? Will there be disagreement and room for debate? Does the thesis assert a position on an issue? I think it’s safe to say the thesis is, indeed, argumentative. It asserts a position on an issue. There will be disagreement. The statement is opinion based. It’s a thesis that clearly reflects its argumentative purpose.

Ok, so let’s talk about how to put together an argument. A variety of structural models exist, such as the Classical Argument, Rogerian Argument, and the Toulmin Model of Argument. In this podcast, I’m going to focus on the practical aspects of the Toulmin Model.

What the Toulmin Model of Argument affords the writer is a framework for constructing and examining an argument. The Toulmin Model has three essential parts–the claim, the grounds, and warrants. There are more complicated renditions of the Toulmin Model, but I want to focus only on these essential parts.

Let’s take a look at each part, but please don’t get too hung up on the terminology, as I am sure that you have been working with claims, grounds, and warrants even if you didn’t use those terms.

The claim is simply the statement the writer makes about the topic. Since we are talking about the framework for an argumentative essay, the claim is the argument the writer makes about the topic and will be reflected in the thesis.

The grounds is the evidence. It’s what supports the argument. The grounds can be personal experience, examples, facts, testimony, statistics, studies, and the like.

The warrant is the assumption, or belief, the writer has in mind when forming an argument. The underlying assumption is generally not stated but, rather, implicit in the argument.

Let me illustrate the three parts of a Toulmin Model argument with this statement: Youth soccer players ten years old and under should not be allowed to head the ball because of the risk of getting a concussion.

Ok, so what’s the claim? Easy enough, right? The claim is the argument. In this example, the argument is that youth soccer players ten years old or under should not be allowed to head the ball.

So what’s the grounds, or evidence? The claim is that soccer players ten years old and under should not be allowed to head the ball, and the reason for this view, the grounds, is because of the risk of getting a concussion.

And what about the underlying assumption, or the warrant? Remember, the warrant is usually not an expressed part of the argument, but it is the underlying basis of the argument. In this example, certainly an underlying assumption the writer has is that people are concerned about the safety of children playing youth soccer (and perhaps youth sports in general).

Make sense?

Let’s look at another example.

Here’s a thesis from earlier in this podcast: The city of Lewiston, Maine, needs to provide better services for its homeless population because many homeless people have medical and mental conditions that are going untreated; some suffer from psychological disorders that could put themselves and others at risk, and many do not have the skills or resources to make them more employable.

And the claim is? The claim this thesis makes is the city of Lewiston, Maine, needs to provide better services for its homeless population.

What are the grounds? (Remember, the grounds refers to the evidence.) In this example, the grounds, or reasons in support of the claim, is that many homeless people have medical and mental conditions that are going untreated; homeless people suffer from psychological disorders that could put themselves and others at risk, and many homeless people do not have the skills or resources to make them more employable.

What is the underlying assumption or the warrant? One assumption could be that not enough is currently being done to help the homeless population. Is that a valid assumption? I am not asking whether or not you agree with this assumption; rather, is the assumption a sound, logical statement? Yes, the assumption is valid. I pose this question because sometimes the underlying assumption of an argument is faulty and if that is the case, then the argument itself will be flawed.

For example, let’s say you’re having a conversation with a coworker who tells you about an article he read in the newspaper about solar power. Your coworker scoffs at the idea of solar power, something he dubs “tree-hugger technology.” He rails on about the various reasons he dislikes solar power, offering one snarky remark after another and taking potshots along the way at those who see solar power as a viable form of alternative energy. In this example, the underlying assumption your coworker makes is that you will agree with what he has to say—otherwise, it’s unlikely he would be so insensitive to an opposing view. Right? I’m sure all of you have had a similar experience in which someone expresses a view on a topic in a way that assumes you share that someone’s view. If the underlying assumption is incorrect, it can make for a most awkward experience.

What the Toulmin Model of Argument offers the writer is a way to think about and structure one’s argument. The model breaks down the key parts of an argument so that the argument can be as clear and precise and thought out as possible. I hope you find the Toulmin Model of Argument a useful tool when writing or analyzing an argumentative essay.

Happy writing.

Share this:

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to print (Opens in new window)

Follow Blog via Email

Enter your email address to follow this blog and receive email notifications of new posts.

Email Address

- RSS - Posts

- RSS - Comments

- COLLEGE WRITING

- USING SOURCES & APA STYLE

- EFFECTIVE WRITING PODCASTS

- LEARNING FOR SUCCESS

- PLAGIARISM INFORMATION

- FACULTY RESOURCES

- Student Webinar Calendar

- Academic Success Center

- Writing Center

- About the ASC Tutors

- DIVERSITY TRAINING

- PG Peer Tutors

- PG Student Access

Subscribe to Blog via Email

Enter your email address to subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.

- College Writing

- Using Sources & APA Style

- Learning for Success

- Effective Writing Podcasts

- Plagiarism Information

- Faculty Resources

- Tutor Training

Twitter feed

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

IV. Types of Argumentation

4.4 Toulmin: Dissecting the Everyday Argument

Rebecca Jones

Philosopher Stephen Toulmin studies the arguments we make in our everyday lives. He developed his method out of frustration with logicians (philosophers of argumentation) that studied argument in a vacuum or through mathematical formulations:

All A are B. All B are C.

Therefore, all A are C. [1]

Instead, Toulmin views argument as it appears in a conversation, in a letter, or some other context because real arguments are much more complex than the syllogisms that make up the bulk of Aristotle’s logical program (for a review of syllogisms see section 3.4 of this text). Toulmin offers the contemporary writer/reader a way to map an argument. The result is a visualization of the argument process. This map comes complete with vocabulary for describing the parts of an argument. The vocabulary allows us to see the contours of the landscape—the winding rivers and gaping caverns. One way to think about a “good” argument is that it is a discussion that hangs together, a landscape that is cohesive (we can’t have glaciers in our desert valley). Sometimes we miss the faults of an argument because it sounds good or appears to have clear connections between the statement and the evidence, when in truth the only thing holding the argument together is a lovely sentence or an artistic flourish.

For Toulmin, argumentation is an attempt to justify a statement or a set of statements. The better the demand is met, the higher the audience’s appreciation. Toulmin’s vocabulary for the study of argument offers labels for the parts of the argument to help us create our map. [2]

Claim: The basic standpoint presented by a writer/ speaker.

Data: The evidence which supports the claim.

Warrant: The justification for connecting particular data to a particular claim. The warrant also makes clear the assumptions underlying the argument.

Backing: Additional information required if the warrant is not clearly supported.

Rebuttal: Conditions or standpoints that point out flaws in the claim or alternative positions.

Qualifiers: Terminology that limits a standpoint. Examples include applying the following terms to any part of an argument: sometimes, seems, occasionally, none, always, never, etc.

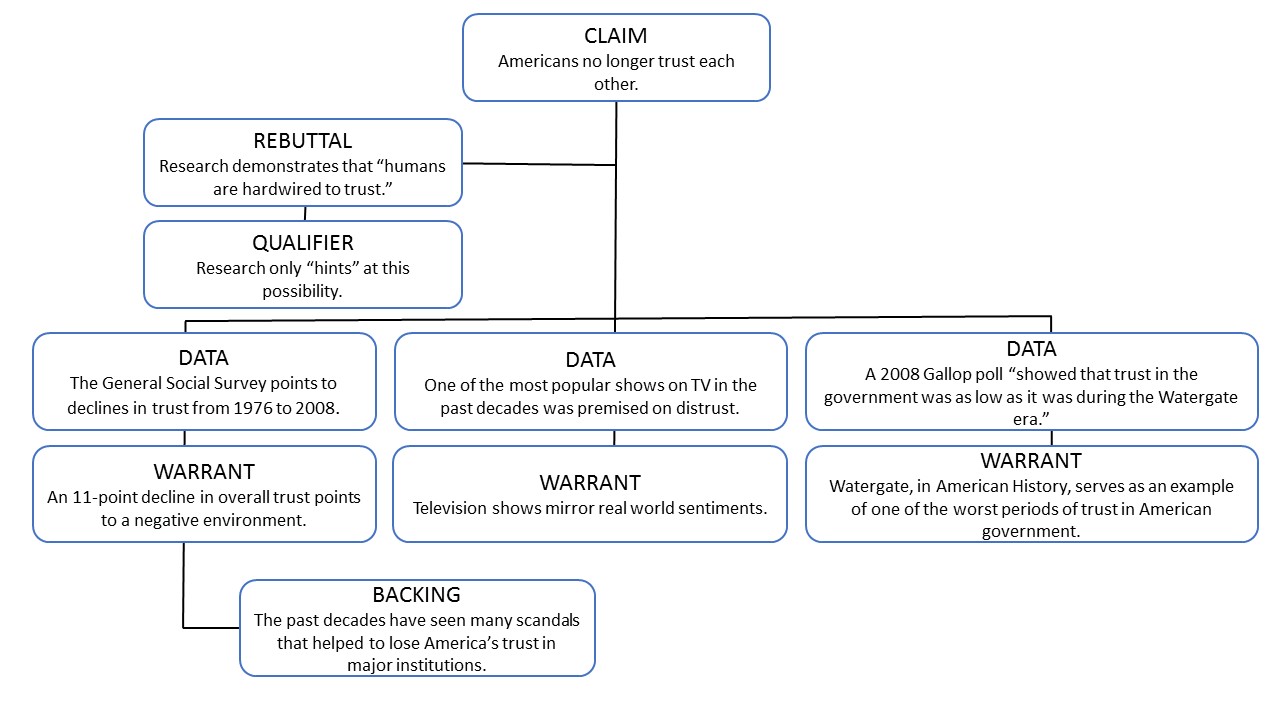

The following paragraphs come from an article reprinted in UTNE magazine by Pamela Paxton and Jeremy Adam Smith titled: “Not Everyone Is Out to Get You.” [3] Charting this excerpt helps us to understand some of the underlying assumptions found in the article.

Example: “Trust No One”

That was the slogan of The X-Files, the TV drama that followed two FBI agents on a quest to uncover a vast government conspiracy. A defining cultural phenomenon during its run from 1993–2002, the show captured a mood of growing distrust in America.

Since then, our trust in one another has declined even further. In fact, it seems that “Trust no one” could easily have been America’s motto for the past 40 years—thanks to, among other things, Vietnam, Watergate, junk bonds, Monica Lewinsky, Enron, sex scandals in the Catholic Church, and the Iraq war.

The General Social Survey, a periodic assessment of Americans’ moods and values, shows an 11-point decline from 1976–2008 in the number of Americans who believe other people can generally be trusted. Institutions haven’t fared any better. Over the same period, trust has declined in the press (from 29 to 9 percent), education (38–29 percent), banks (41 percent to 20 percent), corporations (23–16 percent), and organized religion (33–20 percent). Gallup’s 2008 governance survey showed that trust in the government was as low as it was during the Watergate era.

The news isn’t all doom and gloom, however. A growing body of research hints that humans are hardwired to trust, which is why institutions, through reform and high performance, can still stoke feelings of loyalty, just as disasters and mismanagement can inhibit it. The catch is that while humans want, even need, to trust, they won’t trust blindly and foolishly.

Figure 4.4.1 [4] below demonstrates one way to chart the argument that Paxton and Smith make in “Trust No One.” The remainder of the article offers additional claims and data, including the final claim that there is hope for overcoming our collective trust issues. The chart helps us to see that some of the warrants, in a longer research project, might require additional support. For example, the warrant that TV mirrors real life is an argument and not a fact that would require evidence.

Example of Visualizing an Argument

Charting your own arguments and the arguments of others helps you to visualize the meat of your discussion. All the flourishes are gone and the bones revealed. Even if you cannot fit an argument neatly into the boxes, the attempt forces you to ask important questions about your claim, your warrant, and possible rebuttals. By charting your argument you are forced to write your claim in a succinct manner and admit, for example, what you are using for evidence. Charted, you can see if your evidence is scanty, if it relies too much on one kind of evidence over another, and if it needs additional support. This charting might also reveal a disconnect between your claim and your warrant or cause you to reevaluate your claim altogether.

The Toulmin method is a useful way of determining the validity of an argument and is oftentimes the model used in legal proceedings. But the Toulmin method can leave you feeling as if you’re stuck in an either/or situation as it focuses on justifying the arguer’s reasons only. For a method that incorporates a humanistic approach, consider using the Rogerian method.

This section contains material from:

Jones, Rebecca. “Finding the Good Argument OR Why Bother With Logic?” In Writing Spaces: Readings on Writing, Volume 1 , edited by Charles Lowe and Pavel Zemliansky, 156-179. West Lafayette, IN: Parlor Press, 2010. https://writingspaces.org/?page_id=243 . Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 License.

- Frans H. van Eemeren, Rob Grootendorst, and Francesca Snoeck Henkemans, Argumentation: Analysis, Evaluation, Presentation (Mahwah: Erlbaum, NJ, 2002), 131. ↵

- Stephen Toulmin, The Uses of Argument, ( Ca mbridge: Cambridge University Press, 1958). ↵

- Pamela Paxton and Jeremy Adam Smith, “Reimagining a Politics of Trust: Not Everyone Is Out to Get Yo u,” UNTE Reader, September-October 2009, https://www.utne.com/politics/reimagining-a-political-community-of-trust . ↵

- This image was derived from “Figure 5: This Chart Demonstrates the Utility of Visualizing an Argument” by Rebecca Jones in: Rebecca Jones, “Finding the Good Argument OR Why Bother With Logic?,” i n Writing Spaces: Readings on Writing, Volume 1 , eds. Charles Lowe and Pavel Zemliansky (West Lafayette, IN: Parlor Press, 2010), 156-179, https://writingspaces.org/?page_id=243 . Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 License . ↵

A type of logic or reasoning associated with Aristotle involving a conclusion based on statements called premises which lead to a conclusion. A major premise is a statement of universal truth or common knowledge. A minor premise is a statement related to a major premise but concerns a specific situation. Together, major premises and minor premises form a conclusion. For example, “all dogs are mammals (major premise) and all dogs are mammals (minor premise), so, therefore, all dogs are animals (conclusion).”

To express an idea in as few words as possible; concise, brief, or to the point.

4.4 Toulmin: Dissecting the Everyday Argument Copyright © 2022 by Rebecca Jones is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Organizing Your Argument

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

How can I effectively present my argument?

In order for your argument to be persuasive, it must use an organizational structure that the audience perceives as both logical and easy to parse. Three argumentative methods —the Toulmin Method , Classical Method , and Rogerian Method — give guidance for how to organize the points in an argument.

Note that these are only three of the most popular models for organizing an argument. Alternatives exist. Be sure to consult your instructor and/or defer to your assignment’s directions if you’re unsure which to use (if any).

Toulmin Method

The Toulmin Method is a formula that allows writers to build a sturdy logical foundation for their arguments. First proposed by author Stephen Toulmin in The Uses of Argument (1958), the Toulmin Method emphasizes building a thorough support structure for each of an argument's key claims.

The basic format for the Toulmin Method is as follows:

Claim: In this section, you explain your overall thesis on the subject. In other words, you make your main argument.

Data (Grounds): You should use evidence to support the claim. In other words, provide the reader with facts that prove your argument is strong.

Warrant (Bridge): In this section, you explain why or how your data supports the claim. As a result, the underlying assumption that you build your argument on is grounded in reason.

Backing (Foundation): Here, you provide any additional logic or reasoning that may be necessary to support the warrant.

Counterclaim: You should anticipate a counterclaim that negates the main points in your argument. Don't avoid arguments that oppose your own. Instead, become familiar with the opposing perspective. If you respond to counterclaims, you appear unbiased (and, therefore, you earn the respect of your readers). You may even want to include several counterclaims to show that you have thoroughly researched the topic.

Rebuttal: In this section, you incorporate your own evidence that disagrees with the counterclaim. It is essential to include a thorough warrant or bridge to strengthen your essay’s argument. If you present data to your audience without explaining how it supports your thesis, your readers may not make a connection between the two, or they may draw different conclusions.

Example of the Toulmin Method:

Claim: Hybrid cars are an effective strategy to fight pollution.

Data1: Driving a private car is a typical citizen's most air-polluting activity.

Warrant 1: Due to the fact that cars are the largest source of private (as opposed to industrial) air pollution, switching to hybrid cars should have an impact on fighting pollution.

Data 2: Each vehicle produced is going to stay on the road for roughly 12 to 15 years.

Warrant 2: Cars generally have a long lifespan, meaning that the decision to switch to a hybrid car will make a long-term impact on pollution levels.

Data 3: Hybrid cars combine a gasoline engine with a battery-powered electric motor.

Warrant 3: The combination of these technologies produces less pollution.

Counterclaim: Instead of focusing on cars, which still encourages an inefficient culture of driving even as it cuts down on pollution, the nation should focus on building and encouraging the use of mass transit systems.

Rebuttal: While mass transit is an idea that should be encouraged, it is not feasible in many rural and suburban areas, or for people who must commute to work. Thus, hybrid cars are a better solution for much of the nation's population.

Rogerian Method

The Rogerian Method (named for, but not developed by, influential American psychotherapist Carl R. Rogers) is a popular method for controversial issues. This strategy seeks to find a common ground between parties by making the audience understand perspectives that stretch beyond (or even run counter to) the writer’s position. Moreso than other methods, it places an emphasis on reiterating an opponent's argument to his or her satisfaction. The persuasive power of the Rogerian Method lies in its ability to define the terms of the argument in such a way that:

- your position seems like a reasonable compromise.

- you seem compassionate and empathetic.

The basic format of the Rogerian Method is as follows:

Introduction: Introduce the issue to the audience, striving to remain as objective as possible.

Opposing View : Explain the other side’s position in an unbiased way. When you discuss the counterargument without judgement, the opposing side can see how you do not directly dismiss perspectives which conflict with your stance.

Statement of Validity (Understanding): This section discusses how you acknowledge how the other side’s points can be valid under certain circumstances. You identify how and why their perspective makes sense in a specific context, but still present your own argument.

Statement of Your Position: By this point, you have demonstrated that you understand the other side’s viewpoint. In this section, you explain your own stance.

Statement of Contexts : Explore scenarios in which your position has merit. When you explain how your argument is most appropriate for certain contexts, the reader can recognize that you acknowledge the multiple ways to view the complex issue.

Statement of Benefits: You should conclude by explaining to the opposing side why they would benefit from accepting your position. By explaining the advantages of your argument, you close on a positive note without completely dismissing the other side’s perspective.

Example of the Rogerian Method:

Introduction: The issue of whether children should wear school uniforms is subject to some debate.

Opposing View: Some parents think that requiring children to wear uniforms is best.

Statement of Validity (Understanding): Those parents who support uniforms argue that, when all students wear the same uniform, the students can develop a unified sense of school pride and inclusiveness.

Statement of Your Position : Students should not be required to wear school uniforms. Mandatory uniforms would forbid choices that allow students to be creative and express themselves through clothing.

Statement of Contexts: However, even if uniforms might hypothetically promote inclusivity, in most real-life contexts, administrators can use uniform policies to enforce conformity. Students should have the option to explore their identity through clothing without the fear of being ostracized.

Statement of Benefits: Though both sides seek to promote students' best interests, students should not be required to wear school uniforms. By giving students freedom over their choice, students can explore their self-identity by choosing how to present themselves to their peers.

Classical Method

The Classical Method of structuring an argument is another common way to organize your points. Originally devised by the Greek philosopher Aristotle (and then later developed by Roman thinkers like Cicero and Quintilian), classical arguments tend to focus on issues of definition and the careful application of evidence. Thus, the underlying assumption of classical argumentation is that, when all parties understand the issue perfectly, the correct course of action will be clear.

The basic format of the Classical Method is as follows:

Introduction (Exordium): Introduce the issue and explain its significance. You should also establish your credibility and the topic’s legitimacy.

Statement of Background (Narratio): Present vital contextual or historical information to the audience to further their understanding of the issue. By doing so, you provide the reader with a working knowledge about the topic independent of your own stance.

Proposition (Propositio): After you provide the reader with contextual knowledge, you are ready to state your claims which relate to the information you have provided previously. This section outlines your major points for the reader.

Proof (Confirmatio): You should explain your reasons and evidence to the reader. Be sure to thoroughly justify your reasons. In this section, if necessary, you can provide supplementary evidence and subpoints.

Refutation (Refuatio): In this section, you address anticipated counterarguments that disagree with your thesis. Though you acknowledge the other side’s perspective, it is important to prove why your stance is more logical.

Conclusion (Peroratio): You should summarize your main points. The conclusion also caters to the reader’s emotions and values. The use of pathos here makes the reader more inclined to consider your argument.

Example of the Classical Method:

Introduction (Exordium): Millions of workers are paid a set hourly wage nationwide. The federal minimum wage is standardized to protect workers from being paid too little. Research points to many viewpoints on how much to pay these workers. Some families cannot afford to support their households on the current wages provided for performing a minimum wage job .

Statement of Background (Narratio): Currently, millions of American workers struggle to make ends meet on a minimum wage. This puts a strain on workers’ personal and professional lives. Some work multiple jobs to provide for their families.

Proposition (Propositio): The current federal minimum wage should be increased to better accommodate millions of overworked Americans. By raising the minimum wage, workers can spend more time cultivating their livelihoods.

Proof (Confirmatio): According to the United States Department of Labor, 80.4 million Americans work for an hourly wage, but nearly 1.3 million receive wages less than the federal minimum. The pay raise will alleviate the stress of these workers. Their lives would benefit from this raise because it affects multiple areas of their lives.

Refutation (Refuatio): There is some evidence that raising the federal wage might increase the cost of living. However, other evidence contradicts this or suggests that the increase would not be great. Additionally, worries about a cost of living increase must be balanced with the benefits of providing necessary funds to millions of hardworking Americans.

Conclusion (Peroratio): If the federal minimum wage was raised, many workers could alleviate some of their financial burdens. As a result, their emotional wellbeing would improve overall. Though some argue that the cost of living could increase, the benefits outweigh the potential drawbacks.

Toulmin Method: Guide to Writing a Successful Essay

How to write an essay in the toulmin method.

Argumentative essays are a genre of writing that challenges the student to research a topic, gather, generate and evaluate evidence, and summarize a position on the issue. It helps to get as much benefit out of the study as possible. The Toulmin model essay could be part of the shaping and self-understanding of the individual, and one day it will provide evidence to rely on in becoming a professional.

What is the Toulmin Method?

The essay form has become widespread in contemporary higher education, so many students are faced with this question – how to write an essay using the Toulmin model? The idea of an essay comes to us from the Anglo-Saxon educational tradition, where it is one of the basic elements of learning, especially in the early years. Starting an essay, especially an argument one, is a creative and demanding task. Not all students have time for such a job, given their academic schedule. If you want professional assistance, you can hire a writer to write an argumentative essay to make sure of the quality.

Toulmin’s approach, based on logic and in-depth analysis, is best suited to solving complex questions. The British philosopher and professor engaged in practical argumentation believed that it is a process of proposing hypotheses involving the discovery of new ideas and verifying existing information. In The Uses of Argument (1958), Stephen Toulmin proposed a set containing six interrelated components for analyzing arguments, and these are what we will talk about today. Toulmin considered that a good argument could be successful in credibility and resistance to additional criticism. We shall therefore take a look at how it is done.

How do you compose an essay based on Toulmin model? Formulate the statement that you intend to defend. Provide evidence to support it. Then use the factors we talk about below. As an alternative, you can use information from a custom essay writing service that guarantees a good grade. Not everyone is really gifted at writing well-organized texts.

The Six Parts of The Toulmin Argument

The structure of Toulmin argumentative essay is slightly more complex than in other types of papers.

Think of this section as the main idea behind the whole argument. The claim can be divided into five following categories:

- definitions,

- strategies.

This is the part dealing with the answer to the question, “What is the author trying to prove?”.

The arguments are referred to as the basis for the claim. This is everything that the statement is referring to. It can be statistics, facts, evidence, expert opinions, or public attitudes. At this point, the following issue arises: “What is the author trying to demonstrate his point with?”. This is the body where the connection between the data and the argument is established.

Warrants are assumptions that show how and why the available data results in the claim. It gives credibility to the latter. In addition, it is often common knowledge for both the author and the audience, so in most cases, it is not expressed literally but only implied. The guiding question for determining the warrant of an argument has to be asked, “Why does the author draw this conclusion from the data?”.

Warrant Based Generalization

In the simplest Toulmin essays, the generalization essentially summarizes the common knowledge that applies to each specific case. Due to its simplicity, this technique is also used in public speaking as well as in Toulmin model essay.

Warrant Based on Analogy

An argument by analogy is an argument that is made by extrapolating information from one case to another. This is because they share many characteristics. Therefore, an argument by analogy is also very common.

Warrant Based on Sign