1590s, "trial, attempt, endeavor," also "short, discursive literary composition" (first attested in writings of Francis Bacon, probably in imitation of Montaigne), from French essai "trial, attempt, essay" (in Old French from 12c.), from Late Latin exagium "a weighing, a weight," from Latin exigere "drive out; require, exact; examine, try, test," from ex "out" (see ex- ) + agere "to set in motion, drive" (from PIE root *ag- "to drive, draw out or forth, move") apparently meaning here "to weigh." The suggestion is of unpolished writing. Compare assay , also examine .

"to put to proof, test the mettle of," late 15c., from French essaier , from essai "trial, attempt" (see essay (n.)). This sense has mostly gone with the divergent spelling assay . Meaning "to attempt" is from 1640s. Related: Essayed ; essaying .

Entries linking to essay

c. 1300, "to try, endeavor, strive; test the quality of," from Anglo-French assaier , from assai (n.), from Old French assai , variant of essai "trial" (see essay (n.)). Related: Assayed ; assaying .

c. 1300, "put (someone) to question in regard to knowledge, competence, or skill, inquire into qualifications or capabilities;" mid-14c., "inspect or survey (something) carefully, scrutinize, view or observe in all aspects with the purpose of forming a correct opinion or judgment," from Old French examiner "interrogate, question, torture," from Latin examinare "to test or try; consider, ponder," literally "to weigh," from examen "a means of weighing or testing," probably ultimately from exigere "demand, require, enforce," literally "to drive or force out," also "to finish, measure," from ex "out" (see ex- ) + agere "to set in motion, drive, drive forward; to do, perform" (from PIE root *ag- "to drive, draw out or forth, move"). Legal sense of "question or hear (a witness in court)" is from early 15c. Related: Examined ; examining .

- See all related words ( 6 ) >

Trends of essay

More to explore, share essay.

updated on December 09, 2020

Trending words

- 1 . confide

- 2 . confidence

- 3 . spatula

- 4 . excruciate

- 7 . schedule

- 9 . paschal

- 10 . galumph

Dictionary entries near essay

essentialism

- English (English)

- 简体中文 (Chinese)

- Deutsch (German)

- Español (Spanish)

- Français (French)

- Italiano (Italian)

- 日本語 (Japanese)

- 한국어 (Korean)

- Português (Portuguese)

- 繁體中文 (Chinese)

What Are the Different Types and Characteristics of Essays?

- An Introduction to Punctuation

- Ph.D., Rhetoric and English, University of Georgia

- M.A., Modern English and American Literature, University of Leicester

- B.A., English, State University of New York

The term essay comes from the French for "trial" or "attempt." French author Michel de Montaigne coined the term when he assigned the title Essais to his first publication in 1580. In "Montaigne: A Biography" (1984), Donald Frame notes that Montaigne "often used the verb essayer (in modern French, normally to try ) in ways close to his project, related to experience, with the sense of trying out or testing."

An essay is a short work of nonfiction , while a writer of essays is called an essayist. In writing instruction, essay is often used as another word for composition . In an essay, an authorial voice (or narrator ) typically invites an implied reader (the audience ) to accept as authentic a certain textual mode of experience.

Definitions and Observations

- "[An essay is a] composition , usually in prose .., which may be of only a few hundred words (like Bacon's "Essays") or of book length (like Locke's "Essay Concerning Human Understanding") and which discusses, formally or informally, a topic or a variety of topics." (J.A. Cuddon, "Dictionary of Literary Terms". Basil, 1991)

- " Essays are how we speak to one another in print — caroming thoughts not merely in order to convey a certain packet of information, but with a special edge or bounce of personal character in a kind of public letter." (Edward Hoagland, Introduction, "The Best American Essays : 1999". Houghton, 1999)

- "[T]he essay traffics in fact and tells the truth, yet it seems to feel free to enliven, to shape, to embellish, to make use as necessary of elements of the imaginative and the fictive — thus its inclusion in that rather unfortunate current designation ' creative nonfiction .'" (G. Douglas Atkins, "Reading Essays: An Invitation". University of Georgia Press, 2007)

Montaigne's Autobiographical Essays "Although Michel de Montaigne, who fathered the modern essay in the 16th century, wrote autobiographically (like the essayists who claim to be his followers today), his autobiography was always in the service of larger existential discoveries. He was forever on the lookout for life lessons. If he recounted the sauces he had for dinner and the stones that weighted his kidney, it was to find an element of truth that we could put in our pockets and carry away, that he could put in his own pocket. After all, Philosophy — which is what he thought he practiced in his essays, as had his idols, Seneca and Cicero, before him — is about 'learning to live.' And here lies the problem with essayists today: not that they speak of themselves, but that they do so with no effort to make their experience relevant or useful to anyone else, with no effort to extract from it any generalizable insight into the human condition." (Cristina Nehring, "What’s Wrong With the American Essay." Truthdig, Nov. 29, 2007)

The Artful Formlessness of the Essay "[G]ood essays are works of literary art. Their supposed formlessness is more a strategy to disarm the reader with the appearance of unstudied spontaneity than a reality of composition. . . . "The essay form as a whole has long been associated with an experimental method. This idea goes back to Montaigne and his endlessly suggestive use of the term essai for his writing. To essay is to attempt, to test, to make a run at something without knowing whether you are going to succeed. The experimental association also derives from the other fountain-head of the essay, Francis Bacon , and his stress on the empirical inductive method, so useful in the development of the social sciences." (Phillip Lopate, "The Art of the Personal Essay". Anchor, 1994)

Articles vs. Essays "[W]hat finally distinguishes an essay from an article may just be the author's gumption, the extent to which personal voice, vision, and style are the prime movers and shapers, even though the authorial 'I' may be only a remote energy, nowhere visible but everywhere present." (Justin Kaplan, ed. "The Best American Essays: 1990". Ticknor & Fields, 1990) "I am predisposed to the essay with knowledge to impart — but, unlike journalism, which exists primarily to present facts, the essays transcend their data, or transmute it into personal meaning. The memorable essay, unlike the article, is not place or time-bound; it survives the occasion of its original composition. Indeed, in the most brilliant essays, language is not merely the medium of communication ; it is communication." (Joyce Carol Oates, quoted by Robert Atwan in "The Best American Essays, College Edition", 2nd ed. Houghton Mifflin, 1998) "I speak of a 'genuine' essay because fakes abound. Here the old-fashioned term poetaster may apply, if only obliquely. As the poetaster is to the poet — a lesser aspirant — so the average article is to the essay: a look-alike knockoff guaranteed not to wear well. An article is often gossip. An essay is reflection and insight. An article often has the temporary advantage of social heat — what's hot out there right now. An essay's heat is interior. An article can be timely, topical, engaged in the issues and personalities of the moment; it is likely to be stale within the month. In five years it may have acquired the quaint aura of a rotary phone. An article is usually Siamese-twinned to its date of birth. An essay defies its date of birth — and ours, too. (A necessary caveat: some genuine essays are popularly called 'articles' — but this is no more than an idle, though persistent, habit of speech. What's in a name? The ephemeral is the ephemeral. The enduring is the enduring.)" (Cynthia Ozick, "SHE: Portrait of the Essay as a Warm Body." The Atlantic Monthly, September 1998)

The Status of the Essay "Though the essay has been a popular form of writing in British and American periodicals since the 18th century, until recently its status in the literary canon has been, at best, uncertain. Relegated to the composition class, frequently dismissed as mere journalism, and generally ignored as an object for serious academic study, the essay has sat, in James Thurber's phrase, ' on the edge of the chair of Literature.' "In recent years, however, prompted by both a renewed interest in rhetoric and by poststructuralist redefinitions of literature itself, the essay — as well as such related forms of 'literary nonfiction' as biography , autobiography , and travel and nature writing — has begun to attract increasing critical attention and respect." (Richard Nordquist, "Essay," in "Encylopedia of American Literature", ed. S. R. Serafin. Continuum, 1999)

The Contemporary Essay "At present, the American magazine essay , both the long feature piece and the critical essay, is flourishing, in unlikely circumstances... "There are plenty of reasons for this. One is that magazines, big and small, are taking over some of the cultural and literary ground vacated by newspapers in their seemingly unstoppable evaporation. Another is that the contemporary essay has for some time now been gaining energy as an escape from, or rival to, the perceived conservatism of much mainstream fiction... "So the contemporary essay is often to be seen engaged in acts of apparent anti-novelization: in place of plot , there is drift or the fracture of numbered paragraphs; in place of a frozen verisimilitude, there may be a sly and knowing movement between reality and fictionality; in place of the impersonal author of standard-issue third-person realism, the authorial self pops in and out of the picture, with a liberty hard to pull off in fiction." (James Wood, "Reality Effects." The New Yorker, Dec. 19 & 26, 2011)

The Lighter Side of Essays: "The Breakfast Club" Essay Assignment "All right people, we're going to try something a little different today. We are going to write an essay of not less than a thousand words describing to me who you think you are. And when I say 'essay,' I mean 'essay,' not one word repeated a thousand times. Is that clear, Mr. Bender?" (Paul Gleason as Mr. Vernon) Saturday, March 24, 1984 Shermer High School Shermer, Illinois 60062 Dear Mr. Vernon, We accept the fact that we had to sacrifice a whole Saturday in detention for whatever it was we did wrong. What we did was wrong. But we think you're crazy to make us write this essay telling you who we think we are. What do you care? You see us as you want to see us — in the simplest terms, in the most convenient definitions. You see us as a brain, an athlete, a basket case, a princess and a criminal. Correct? That's the way we saw each other at seven o'clock this morning. We were brainwashed... But what we found out is that each one of us is a brain and an athlete and a basket case, a princess, and a criminal. Does that answer your question? Sincerely yours, The Breakfast Club (Anthony Michael Hall as Brian Johnson, "The Breakfast Club", 1985)

- What Is a Personal Essay (Personal Statement)?

- The Difference Between an Article and an Essay

- The Essay: History and Definition

- What Is Expository Writing?

- 'Whack at Your Reader at Once': Eight Great Opening Lines

- Classic British and American Essays and Speeches

- Definition and Examples of Analysis in Composition

- The Title in Composition

- What is a Familiar Essay in Composition?

- Understanding Organization in Composition and Speech

- Development in Composition: Building an Essay

- List (Grammar and Sentence Styles)

- What Is Tone In Writing?

- Point of View in Grammar and Composition

- A Guide to Using Quotations in Essays

- Compose a Narrative Essay or Personal Statement

Literary Devices

Literary devices, terms, and elements, definition of essay.

An essay is a short piece writing, either formal or informal, which expresses the author’s argument about a particular subject. A formal essay has a serious purpose and highly structured organization, while an informal essay may contain humor, personal recollections and anecdotes, and any sort of organization or form which the author wants. Note that while a formal essay has a more detached tone, it can also represent the author’s personal opinions and be written from the author’s point of view . Essays are shorter than a thesis or dissertation, and thus deal with the matter at hand in a limited way. Essays can deal with many different themes, such as analysis of a text, political opinions, scientific ideas, abstract concepts, fragments of autobiography, and so on.

The word essay comes from the French word essayer , which means “to try” or “to attempt.” A sixteenth-century Frenchman named Michel de Montaigne was the first to create the modern-day definition of essay when he called his writing exercises essays, meaning that he was simply “trying” to get his thoughts on paper.

Common Examples of Essay

Essays are a mainstay of many educational systems around the world. Most essays include some form of analysis and argument, and thus develop a student’s critical thinking skills. Essays require a student to understand what he or she has read or learned well enough to write about it, and thus they are a good tool for ensuring that students have internalized the material. Tests such as the SATs and GREs include a very important essay section. Essays also can be important for admission to university programs and even to be hired for certain jobs.

There are many popular magazines which feature intellectual essays as a core part of their offerings, such as The New Yorker, The Atlantic, and Harper’s Magazine .

Significance of Essay in Literature

Many famous writers and thinkers have also written numerous examples of essays. For instance, the treatises of the philosophers Plutarch, Cicero, and Seneca are all early forms of essay writing. Essay writing might seem dull to school children, but in fact the form has become extremely popular, often converging with a type of writing called “creative non-fiction.” Authors are able to explore complex concepts through anecdote , evidence , and exploration. An author may want to persuade his or her audience to accept a central idea, or simply describe what he or she has experienced. Below you will find examples of essays from famous writers.

Examples of Essay in Literature

Trust thyself: every heart vibrates to that iron string. Accept the place the divine providence has found for you, the society of your contemporaries, the connection of events. Great men have always done so, and confided themselves childlike to the genius of their age, betraying their perception that the absolutely trustworthy was seated at their heart, working through their hands, predominating in all their being. And we are now men, and must accept in the highest mind the same transcendent destiny; and not minors and invalids in a protected corner, not cowards fleeing before a revolution, but guides, redeemers, and benefactors, obeying the Almighty effort, and advancing on Chaos and the Dark.

(“Self-Reliance” by Ralph Waldo Emerson)

Ralph Waldo Emerson was an essayist and poet who was a part of the Transcendentalist movement and who believed strongly in the importance of individualism and self-reliance. The above essay example, in fact, is titled “Self-Reliance,” and encourages human beings to trust themselves and strike out on their own.

Yet, because he was so small, and so simple a form of the energy that was rolling in at the open window and driving its way through so many narrow and intricate corridors in my own brain and in those of other human beings, there was something marvelous as well as pathetic about him. It was as if someone had taken a tiny bead of pure life and decking it as lightly as possible with down and feathers, had set it dancing and zig-zagging to show us the true nature of life. Thus displayed one could not get over the strangeness of it. One is apt to forget all about life, seeing it humped and bossed and garnished and cumbered so that it has to move with the greatest circumspection and dignity. Again, the thought of all that life might have been had he been born in any other shape caused one to view his simple activities with a kind of pity.

(“The Death of the Moth” by Virginia Woolf)

Virginia Woolf’s essay “The Death of the Moth” describes the simplest of experiences—her watching a moth die. And yet, due to her great descriptive powers, Woolf makes the experience seem nontrivial.

Here was I, the white man with his gun, standing in front of the unarmed native crowd — seemingly the leading actor of the piece; but in reality I was only an absurd puppet pushed to and fro by the will of those yellow faces behind. I perceived in this moment that when the white man turns tyrant it is his own freedom that he destroys. He becomes a sort of hollow, posing dummy, the conventionalized figure of a sahib. For it is the condition of his rule that he shall spend his life in trying to impress the ‘natives’, and so in every crisis he has got to do what the ‘natives’ expect of him. He wears a mask, and his face grows to fit it. I had got to shoot the elephant. I had committed myself to doing it when I sent for the rifle. A sahib has got to act like a sahib; he has got to appear resolute, to know his own mind and do definite things. To come all that way, rifle in hand, with two thousand people marching at my heels, and then to trail feebly away, having done nothing — no, that was impossible. The crowd would laugh at me. And my whole life, every white man’s life in the East, was one long struggle not to be laughed at.

(“Shooting an Elephant” by George Orwell)

George Orwell’s marvelous essay “Shooting an Elephant” tells the story of when he was a police officer in Lower Burma and was asked to deal with an elephant wandering through a market. Orwell brilliantly extrapolates his role in shooting and killing the animal to the effects of Imperialism and the British Empire.

Not that it’s profound, but I’m struck, amid the pig’s screams and wheezes, by the fact that these agricultural pros do not see their stock as pets or friends. They are just in the agribusiness of weight and meat. They are unconnected, even at the fair’s self-consciously special occasion of connection. And why not?—even at the fair their products continue to drool and smell and scream, and the work goes on. I can imagine what they think of us, cooing at the swine: we fairgoers don’t have to deal with the business of breeding and feeding our meat; our meat simply materializes at the corn-dog stand, allowing us to separate our healthy appetites from fur and screams and rolling eyes. We tourists get to indulge our tender animal-rights feelings with our tummies full of bacon. I don’t know how keen these sullen farmers’ sense of irony is, but mine’s been honed East Coast keen, and I feel like a bit of an ass in the Swine Barn.

(“Ticket to the Fair” by David Foster Wallace)

David Foster Wallace wrote many famous essays as well as novels; he often looks at modern life with a heightened attention to detail and different perspectives. In the essay “Ticket to the Fair,” he visits a fair and describes what he sees and feels, including the excerpt above where he considers the different way he and the farmers at the fair feel about animals.

Test Your Knowledge of Essay

1. Which of the following statements is the best essay definition? A. A research project of many tens of thousands of words concerning a particular argument. B. A short piece of writing that expresses the author’s opinion or perspective on a subject. C. A strict and highly organized piece of writing that doesn’t contain the author’s own opinion.

2. Which of the following is not likely to be featured in an example of essay? A. A political opinion B. An anecdote C. A fable

3. Which of the following statements is true? A. Essays are found in many intellectual magazines. B. Essays are only used in school settings. C. Essays are always boring.

French translation of 'essay'

Browse Collins English collocations essay

Video: pronunciation of essay.

Examples of 'essay' in a sentence essay

Trends of essay.

View usage over: Since Exist Last 10 years Last 50 years Last 100 years Last 300 years

Browse alphabetically essay

- esprit de corps

- essay question

- All ENGLISH words that begin with 'E'

Related terms of essay

- literary essay

- my essay plan

- to publish an essay

Quick word challenge

Quiz Review

Score: 0 / 5

Wordle Helper

Scrabble Tools

You are using an outdated browser. Please upgrade your browser or activate Google Chrome Frame to improve your experience.

How to Write an Essay in French Without Giving Yourself Away as a Foreigner

Have something to say?

When it comes to expressing your thoughts in French , there’s nothing better than the essay.

It is, after all, the favorite form of such famed French thinkers as Montaigne, Chateaubriand, Houellebecq and Simone de Beauvoir.

In this post, I’ve outlined the four most common types of essays in French, ranked from easiest to most difficult, to help you get to know this concept better.

Why Are French Essays Different?

Must-have french phrases for writing essays, 4 types of french essays and how to write them, 1. text summary (synthèse de texte).

- 2. Text Commentary (Commentaire de texte)

3. Dialectic Dissertation (Thèse, Antithèse, Synthèse)

- 4. Progressive Dissertation (Plan progressif)

And one more thing...

Download: This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you can take anywhere. Click here to get a copy. (Download)

Writing an essay in French is not the same as those typical 5-paragraph essays you’ve probably written in English.

In fact, there’s a whole other logic that has to be used to ensure that your essay meets French format standards and structure. It’s not merely writing your ideas in another language .

And that’s because the French use Cartesian logic (also known as Cartesian doubt) , developed by René Descartes , which requires a writer to begin with what is known and then lead the reader through to the logical conclusion: a paragraph that contains the thesis. Through the essay, the writer will reject all that is not certain or all that is subjective in his or her quest to find the objective truth.

Sound intriguing? Read on for more!

Before we get to the four main types of essays, here are a few French phrases that will be especially helpful as you delve into essay-writing in French:

Introductory phrases , which help you present new ideas.

Connecting phrases , which help you connect ideas and sections.

Contrasting phrases , which help you juxtapose two ideas.

Concluding phrases , which help you to introduce your conclusion.

The text summary or synthèse de texte is one of the easiest French writing exercises to get a handle on. It essentially involves reading a text and then summarizing it in an established number of words, while repeating no phrases that are in the original text. No analysis is called for.

A synthèse de texte should follow the same format as the text that is being synthesized. The arguments should be presented in the same way, and no major element of the original text should be left out of the synthèse.

Here is an informative post about writing a synthèse de texte , written for French speakers.

The text summary is a great exercise for exploring the following French language elements:

- Synonyms , as you will need to find other words to describe what is said in the original text.

- Nominalization , which involves turning verbs into nouns and generally cuts down on word count.

- Vocabulary , as the knowledge of more exact terms will allow you to avoid periphrases and cut down on word count.

While beginners may wish to work with only one text, advanced learners can synthesize as many as three texts in one text summary.

Since a text summary is simple in its essence, it’s a great writing exercise that can accompany you through your entire learning process.

2. Text Commentary (Commentaire de texte)

A text commentary or commentaire de texte is the first writing exercise where the student is asked to present an analysis of the materials at hand, not just a summary.

That said, a commentaire de texte is not a reaction piece. It involves a very delicate balance of summary and opinion, the latter of which must be presented as impersonally as possible. This can be done either by using the third person (on) or the general first person plural (nous) . The singular first person (je) should never be used in a commentaire de texte.

A commentaire de texte should be written in three parts:

- An introduction , where the text is presented.

- An argument , where the text is analyzed.

- A conclusion , where the analysis is summarized and elevated.

Here is a handy in-depth guide to writing a successful commentaire de texte, written for French speakers.

Unlike with the synthesis, you will not be able to address all elements of a text in a commentary. You should not summarize the text in a commentary, at least not for the sake of summarizing. Every element of the text that you speak about in your commentary must be analyzed.

To successfully analyze a text, you will need to brush up on your figurative language. Here are some great resources to get you started:

- Here’s an introduction to figurative language in French.

- This guide to figurative language presents the different elements in useful categories.

- This guide , intended for high school students preparing for the BAC—the exam all French high school students take, which they’re required to pass to go to university—is great for seeing examples of how to integrate figurative language into your commentaries.

- Speaking of which, here’s an example of a corrected commentary from the BAC, which will help you not only include figurative language but get a head start on writing your own commentaries.

The French answer to the 5-paragraph essay is known as the dissertation . Like the American 5-paragraph essay, it has an introduction, body paragraphs and a conclusion. The stream of logic, however, is distinct.

There are actually two kinds of dissertation, each of which has its own rules.

The first form of dissertation is the dialectic dissertation , better known as thèse, antithèse, synthèse . In this form, there are actually only two body paragraphs. After the introduction, a thesis is posited. Following the thesis, its opposite, the antithesis, is explored (and hopefully, debunked). The final paragraph, what we know as the conclusion, is the synthesis , which addresses the strengths of the thesis, the strengths and weaknesses of the antithesis, and concludes with the reasons why the original thesis is correct.

For example, imagine that the question was, “Are computers useful to the development of the human brain?” You could begin with a section showing the ways in which computers are useful for the progression of our common intelligence—doing long calculations, creating in-depth models, etc.

Then you would delve into the problems that computers pose to human intelligence, citing examples of the ways in which spelling proficiency has decreased since the invention of spell check, for example. Finally, you would synthesize this information and conclude that the “pro” outweighs the “con.”

The key to success with this format is developing an outline before writing. The thesis must be established, with examples, and the antithesis must be supported as well. When all of the information has been organized in the outline, the writing can begin, supported by the tools you have learned from your mastery of the synthesis and commentary.

Here are a few tools to help you get writing:

- Here’s a great guide to writing a dialectic dissertation .

- Here’s an example of a plan for a dialectic dissertation , showing you the three parts of the essay as well as things to consider when writing a dialectic dissertation.

4. Progressive Dissertation ( Plan progressif)

The progressive dissertation is slightly less common, but no less useful, than the first form.

The progressive form basically consists of examining an idea via multiple points of view—a sort of deepening of the understanding of the notion, starting with a superficial perspective and ending with a deep and profound analysis.

If the dialectic dissertation is like a scale, weighing pros and cons of an idea, the progressive dissertation is like peeling an onion, uncovering more and more layers as you get to the deeper crux of the idea.

Concretely, this means that you will generally follow this layout:

- A first, elementary exploration of the idea.

- A second, more philosophical exploration of the idea.

- A third, more transcendent exploration of the idea.

This format for the dissertation is more commonly used for essays that are written in response to a philosophical question, for example, “What is a person?” or “What is justice?”

Let’s say the question was, “What is war?” In the first part, you would explore dictionary definitions—a basic idea of war, i.e. an armed conflict between two parties, usually nations. You could give examples that back up this definition, and you could narrow down the definition of the subject as much as needed. For example, you might want to make mention that not all conflicts are wars, or you might want to explore whether the “War on Terror” is a war.

In the second part, you would explore a more philosophical look at the topic, using a definition that you provide. You first explain how you plan to analyze the subject, and then you do so. In French, this is known as poser une problématique (establishing a thesis question), and it usually is done by first writing out a question and then exploring it using examples: “Is war a reflection of the base predilection of humans for violence?”

In the third part, you will take a step back and explore this question from a distance, taking the time to construct a natural conclusion and answer for the question.

This form may not be as useful in as many cases as the first type of essay, but it’s a good form to learn, particularly for those interested in philosophy. Here’s an in-depth guide to writing a progressive dissertation.

As you progress in French and become more and more comfortable with writing, try your hand at each of these types of writing exercises, and even with other forms of the dissertation . You’ll soon be a pro at everything from a synthèse de texte to a dissertation!

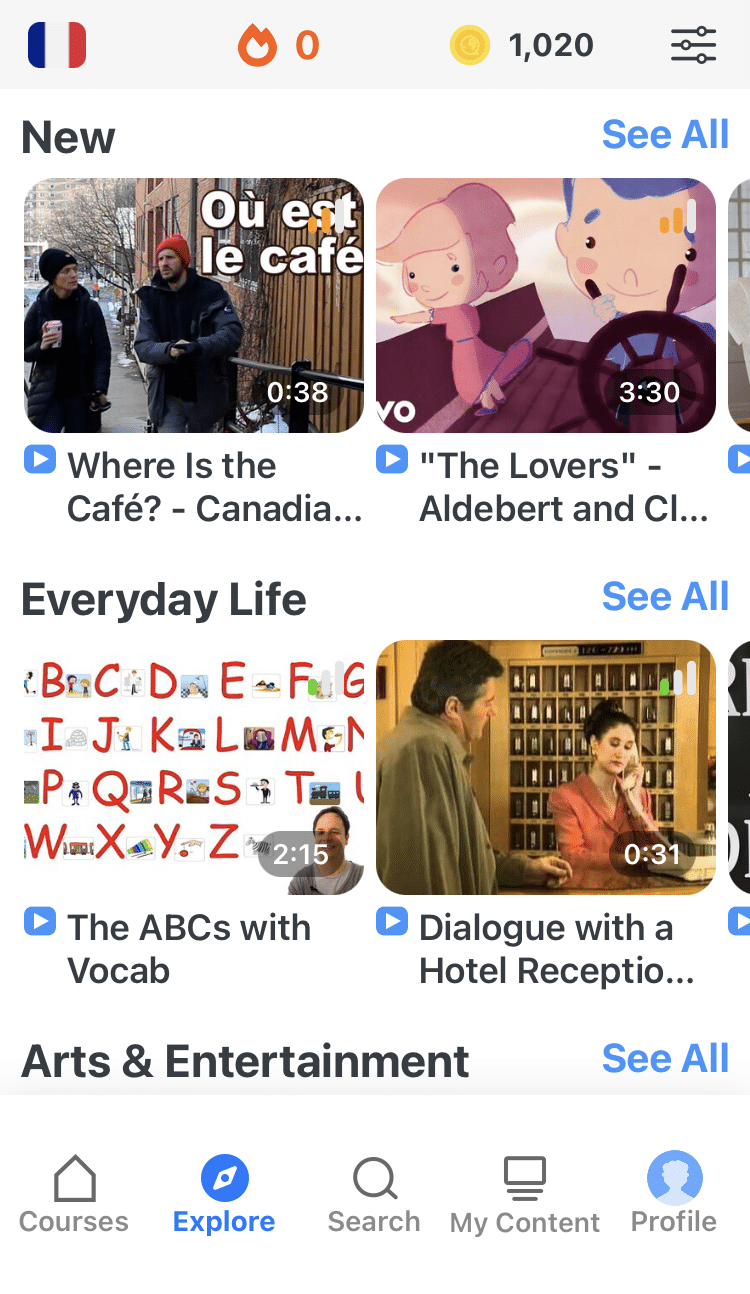

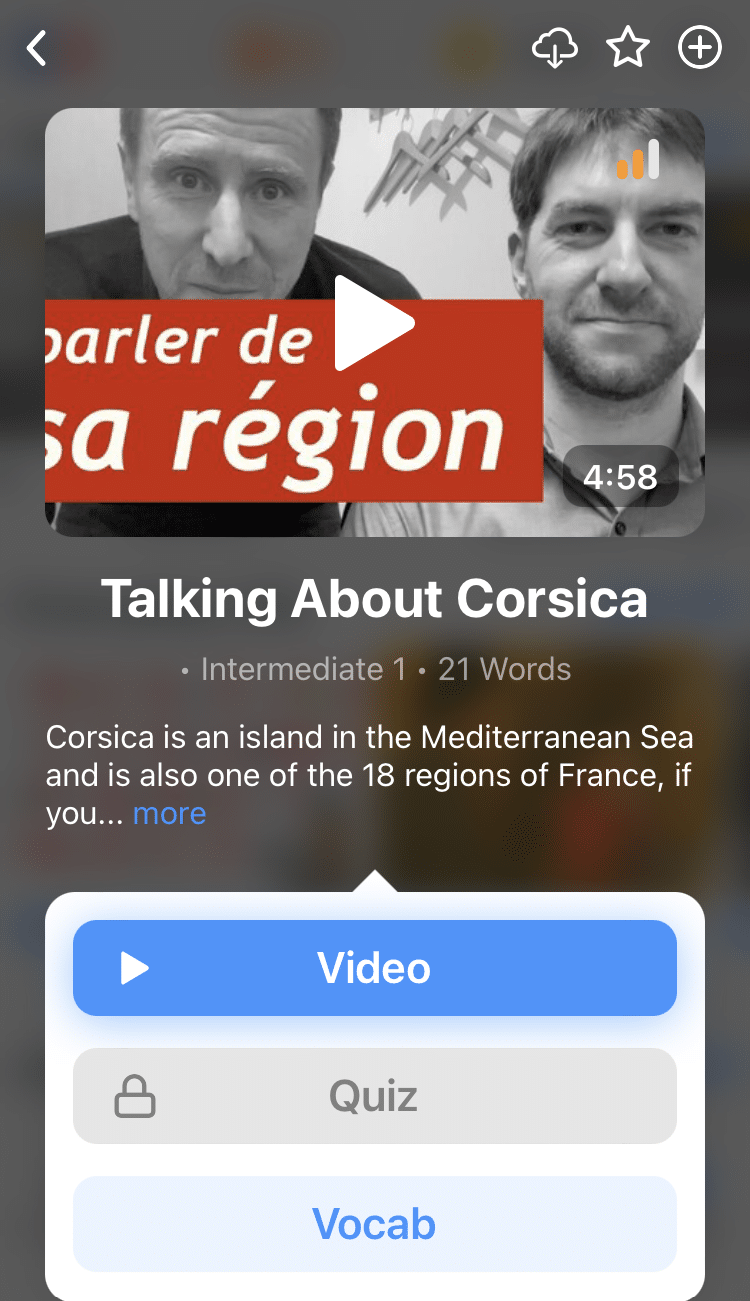

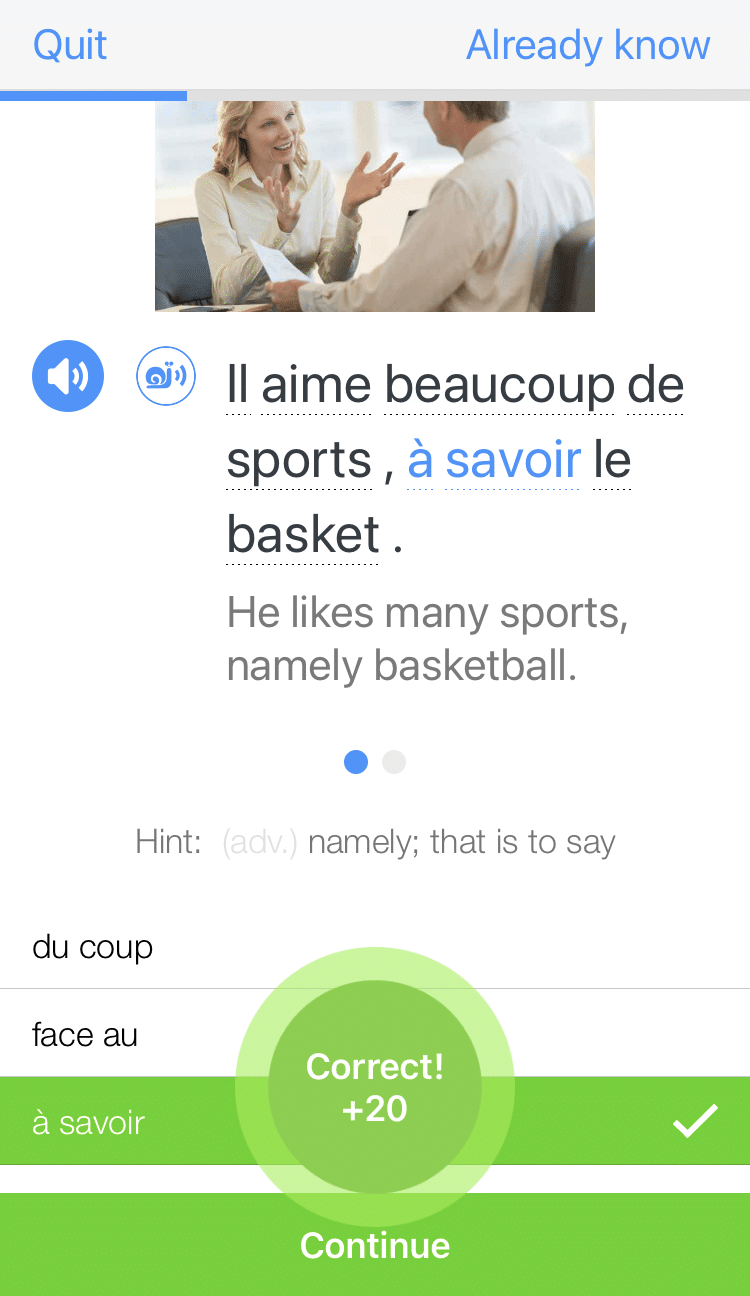

FluentU has a wide variety of great content, like interviews, documentary excerpts and web series, as you can see here:

FluentU brings native French videos with reach. With interactive captions, you can tap on any word to see an image, definition and useful examples.

For example, if you tap on the word "crois," you'll see this:

Practice and reinforce all the vocabulary you've learned in a given video with learn mode. Swipe left or right to see more examples for the word you’re learning, and play the mini-games found in our dynamic flashcards, like "fill in the blank."

All throughout, FluentU tracks the vocabulary that you’re learning and uses this information to give you a totally personalized experience. It gives you extra practice with difficult words—and reminds you when it’s time to review what you’ve learned.

Start using the FluentU website on your computer or tablet or, better yet, download the FluentU app from the iTunes or Google Play store. Click here to take advantage of our current sale! (Expires at the end of this month.)

Enter your e-mail address to get your free PDF!

We hate SPAM and promise to keep your email address safe

Creative Arts Toolkit

What is an essay.

The word ‘essay’ comes from the old French ‘essai’, meaning ‘trial’, ‘attempt’, ‘effort’. This might seem rather appropriate. After all, essays are an effort, as anyone who has ever written one will know. But they might be a different kind of effort to the one that they are often associated with. They are a trial, for sure, but if they are done in the right spirit, they might be seen as a trial of ideas and imagination, rather than a trial of endurance, commitment and sanity.

So, to essay something is to test, to weigh, to try out, to challenge…

The notion of an essay as a piece of writing on a particular subject begins with the work of a French writer called Michel de Montaigne (1533–92), who published his first book of essays in 1580. These had been written, it seems, partly to compensate for the death of a good friend, with whom he had enjoyed many evenings of lively discussion. In a sense, Montaigne’s essays were attempts to carry out arguments with himself, to exercise his brain, to think things through. The personal tone of Montaigne’s essays is something which is often discouraged in modern academic essay writing, but the importance of wrestling with ideas and carrying out an argument remains.

What is a good essay?

Here are three key things that you should remember when writing an essay:

- An essay is not a report Make sure that you focus on analysis and debate, not the literal reporting of facts.

- Stick to the brief Your essay must meet the specific requirements of your chosen brief. A topic that is relevant to the module as a whole may not necessarily meet the specific brief, so make sure that you read the brief carefully and understand what it requires of you.

- Research first You will not be able to plan and write a good essay unless you have explored the subject thoroughly, which includes looking at a range of other texts.

Essential aspects of good essay writing are:

- Relevance to the brief Make sure that every paragraph clearly contributes to the aims laid out in the brief, and that your conclusion responds directly to your stated aims.

- Evidence of appropriate research It is a good idea to refer directly to source texts. Make sure you choose sources that are appropriate academic texts such as journal articles and books. The reading list is a good place to start. Remember to reference all sources.

- Evidence that you understand and make appropriate use of source materials Show that you understand the texts that you have read. Demonstrate how they are relevant to your aims, and how they relate to other texts on the same subject.

- Adherence to appropriate essay conventions, including: Presentation/formatting, referencing, properly captioned illustrations.

- Good communication Use a spellchecker and grammar checker (available in Microsoft Word). Use formal English, and avoid ‘chattiness’, slang, and vague subjective words like ‘boring’ and ‘fantastic’.

- Structure Begin with an introduction and end with a conclusion. Make sure that your paragraphs flow logically from one to the next. Present your arguments prominently.

- Clear arguments Make reasoned arguments in response to your research. Make sure your arguments are appropriately conceptual and analytical, and that they are presented clearly.

- Understanding of contexts Show that you understand the broader context of your arguments, and their wider implications. Demonstrate a knowledge of how your essay topics are relevant to the wider field of art, design or media practice and criticism.

- Providing analysis This might mean critically evaluating selected artefacts, products, films or architecture, for example, or the work of a practitioner, and supporting every point you make with good quality criticism by respected experts. The bulk of your essay therefore will be analysis, and you should plan with this in mind.

Things to avoid include:

- Writing historical essays You need to provide some basic factual information and a sense of the context of your topic, but keep it short and only include what is relevant to the question. A technical account of CGI is not relevant to the relationship between fantasy film and social change in the 21st century, for example. Don’t include information just because you have it!

- A heavily biographical approach It might be interesting to know that F.W. Murnau liked to paint his earlobes with bat’s blood, or that Peter Jackson keeps a family of rare insects in his beard – but are these facts really relevant to the work?

- Generalisation and waffle Focus on specific aspects of the examples you discuss, and concentrate on criticism, analysis, evaluation, interpretation, argument, rather than simple survey and description.

- Relying on what you already know If you don’t research and build your knowledge and understanding, you will not write a successful essay.

- Plagiarism Plagiarism is the attempt to present another person’s work as your own. At best it is a sign of bad practice, at worst it is cheating and deception. It is avoided by following good practices of note-taking and adhering to academic conventions of quotation, referencing and bibliography. (See sections on Referencing and Academic Conduct)

Doing the groundwork: preparing to write your essay

Tackling an essay at degree level means doing some initial planning and developing habits of good practice. In the long run this will save you time and improve the quality of your essay. Before we look in detail at planning your essay, there are some key things you can do to help yourself:

- Read the brief and/or essay question If there is a selection of questions to choose from, you must discuss this choice with your tutor. Not all questions suit everyone! Similarly, if you are coming up with your own question, you need to talk this over with your tutor.

- Attend every session Even if you don’t think that it is directly relevant to your essay, you need to be there to understand the broader context of your topic and what is required of an essay at this level. It is impossible for a student with poor attendance to write a good essay. If you fail your essay and your attendance is poor you may have to repeat the whole course next year in addition to your other work – don’t risk it!

- Use StudyNet and check your email regularly The module website contains lots of information, including the module booklist and lecture notes. Email is likely to be your tutor’s only way to contact you, so if you don’t check it you will miss important information.

- 1 week to proofread, format, present, print and bind your essay

- 1-2 weeks to write it (Levels 4 and 5)

- 3-4 weeks to read and research the topic and plan the essay

- As you can see, this takes you almost to the beginning of your module. So, don’t put it off…

- Make use of tutorials and other offered support (e.g. dyslexia support)

- Tell your tutor at once if there’s a problem S/he can’t help you if you don’t!

- Back it up (and then back up the back-up!) Back everything up regularly and make sure you print a hard copy at every stage. Use the UH U-drive or Google Docs remote storage to store your work as well as a memory stick or CD. If you need a reminder to do this, click here!

- Use the Study Skills Guide

Two key ideas: argument and critical analysis

Core to successful essay writing (and to other kinds of academic work as well) are the concepts of argument and critical analysis. Tutors will often talk about these, and they tend to feature prominently in assignment briefs, learning outcomes, assessment criteria and feedback on work. So, what are they? Here are some notes:

An essay must develop a line of argument. This is likely to be formed from a series of smaller arguments, each of which should contribute to meeting the aims set out in the brief. An argument is a discussion based on evidence which is intended to make a particular case clearly and persuasively. It should be:

- Informed by research Respond directly to source texts and artefacts. Don’t present an argument as if it is personal opinion.

- Fair/Balanced Consider alternative perspectives, even (especially!) if you are going to argue for a particular case.

- Supported by evidence Without evidence, your argument will come across as speculation and waffle.

- Based on critical analysis…

Critical Analysis

When you present an artefact (artwork, media artefact, etc.) or text, you should not simply describe it. Don’t accept it at face value. You should explore its meaning and contexts, and show its particular significance to your essay. The question to ask is not so much what the thing is but why it is what it is.

Consider the following:

- What does it tell us? Does it reveal anything about its subject or a wider context?

- What ideas does it represent? What philosophies, opinions, beliefs, prejudices, etc. underlie the artefact?

- What are the artist’s/author’s motives? Why did (s)he create it, and what message did (s)he intend to communicate?

- Audience response How might difference audiences react to the artefact?

- What is the wider context? Does the artefact reflect a particular movement? Does it respond to anything that has come before?

How can we improve this article? If you would like a reply, please provide your email address.

Captcha: + = Verify Human or Spambot ?

- Sep 1, 2020

The Birth of the Essay: Reading Montaigne and Descartes

Andrea di carlo | university college cork.

I n France, in the sixteenth century, a new philosophical and literary genre emerged as a novel literary outlet, the essay. The word ‘essay’ comes from the French ‘essai’, which means ‘attempt’ or ‘try-out’. The essay is the attempt to redefine knowledge. The French philosopher Michel de Montaigne is credited with the creation of the essay. The sixteenth century had been shaken by epoch-making events like the discovery of America, the Reformation and the French Wars of Religion; as a result, Montaigne needed to spell out what he believed in. He could only do this through the essay, a genre which leaves authors ample leeway to explore new ideas.

Montaigne’s Essays went through three editions, the first appearing in 1580. This is because Montaigne’s ideas were always fleeting and volatile. Montaigne claimed that his essays were like ‘chimeras’, creations of his mind which, as such, would always change. Montaigne affirmed that the Essays were ‘consubstantial with its author’, meaning that Michel de Montaigne was the topic of his book. By writing essays, i.e. by attempting to define himself in few pages, he had feedback from himself. What he knew was what was contained in the book and it changed frequently because his ideas were always changing. The essay was a humble work. Its author knew that he did not know anything; thus, the only thing he could do was to get continuous feedback from himself by recording what he believed. In his Essays, Montaigne discussed topics from multiple perspective and drew a conclusion at the end. This strategy was employed by Montaigne as well in his editions of the Essays. Essays was Montaigne’s attempt to clarify his ideas. Montaigne did not feel that he could to commit to any final value judgement. He did, however, acknowledge the fallible nature of human knowledge and the equal worth of different ideas. This raises questions as to how twenty-first century forums for discourse, namely the major social media platforms, are indicative of their early-modern predecessors.

If sixteenth-century France consigned us Montaigne, another Frenchman René Descartes stood out as one of the most important intellectuals of seventeenth-century Europe. Both thinkers lived at a time of socio-political disharmony and both criticised established knowledge in order to develop new ideas. Descartes was to break ground in the way scientific research was conducted, and he did so in his essay Discourse on Method of Rightly Conducting One’s Reason and of Seeking Truth in Science (1637). In it, Descartes argued that in order to make ‘far greater progress in science’ observation and testing were necessary. Descartes (like Montaigne) invoked humbleness. Whilst it was desirable to advance the cause of science, this should not be done with ‘bias’. This is the reason why Descartes championed diligence: a novel system of knowledge should be systematically weighed and carefully considered. As well as confronting the challenges, Descartes also tried to sketch a new moral framework.

Descartes had been one of the many witnesses of the war between the influential Huguenot (Calvinist) minority and the Roman Catholic Church. Albeit a Roman Catholic himself, he needed a new place to pursue his studies and thus moved to Netherlands, which had harboured the large majority of run-away European scholars since the sixteenth century. Far away from religious strife, he sketched a temporary framework for morality. Consequently, Descartes rejected sweeping changes, but recommended abiding by ‘the laws and customs’ and the ‘faith’ of one’s country. Like science, even morality needed a new ‘road’, but it had to be carefully designed. Discourse on Method was Descartes’s essay in which he proposed a strategy as to how one can direct one’s scientific analyses at a time of change. He was not asserting that his method is unquestionable and perfect but quite the contrary. He was offering a new way to study science by asking his readership to co-operate with him. As for morality, Descartes intended to design a moral model, but this needed more time than he was afforded. Descartes committed himself to a temporary prototype, which demanded adherence to the customs and religion of one’s country.

Montaigne created a new philosophical genre to study himself at a time of great change, the essay. An essay is an attempt; it is a way to discuss ideas which can be subject to ongoing evolution. Montaigne’s Essays should be considered a sketch of an autobiography, because his surroundings could always change.

René Descartes tried to rebuild the developing basis of scientific investigation. Living against the backdrop of seismic intellectual change meant that a clearer and more systematic idea of what kind of scientific undertaking was necessary; hence, his Discourse on Method. It is in his Discourse that Descartes drew his road map to aspire to a certain degree of certainty in scientific discoveries. First and foremost, intellectuals ought not to take anything at face value: a careful and systematic analysis is required. Descartes’s principles demand one defines their objectives and provides the necessary evidence; no longer can one rely on dogmas or pre-established ideas; now one need testing and validation. In the same way science was being reformed, Descartes wanted to design a new approach to morality. It could not be done hastily, but it needed more time. Therefore, Descartes did not commit to significant changes, but he recommended abiding by the status quo. With the pandemic being the new normal, Montaigne and Descartes will make necessary and thought-provoking reading.

----------------------

Further Reading

Descartes, René, Discourse on the Method of Rightly Conducting One's Reason and of Seeking Truth in the Sciences (1637).

Montaigne, The Essays (1580) ( https://www.gutenberg.org/files/3600/3600-h/3600-h.htm) .

Moriarty, Micheal and Jennings, Jeremy, eds., The Cambridge History of French Thought (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2019).

Andrea DiCarlo is a third-year PhD candidate in early-modern political philosophy and history of philosophy at University College Cork. DiCarlo's research interests lie in early-modern philosophy and literature (Machiavelli, Montaigne, Descartes and Thomas Browne), continental philosophy (Fassin and Foucault) and early-modern history (the Reformation).

Twitter: @andreadicarlo89

Related Posts

Political and Party Passions: Girolamo Savonarola and the Florentine Crowds

Tackling the Archives: The PAST

Tackling the Archive: Unlocking Palaeography

Kommentarer

- 1.1.1 Pronunciation

- 1.1.2.1 Derived terms

- 1.1.2.2 Related terms

- 1.1.2.3 Translations

- 1.2.1 Pronunciation

- 1.2.2.1 Translations

- 1.3 Anagrams

- 2.1 Etymology

- 2.2 Pronunciation

- 2.3.1 Hypernyms

- 2.3.2 Derived terms

- 2.3.3 Descendants

- 3.1 Etymology

- 3.2.1 Derived terms

- 3.3 References

- 4.1 Etymology

- 4.2.1 Derived terms

- 4.3 References

English [ edit ]

Etymology 1 [ edit ].

Since late 16th century, borrowed from Middle French essay , essai ( “ essay ” ) , meaning coined by Montaigne in the same time, from the same words in earlier meanings 'experiment; assay; attempt', from Old French essay , essai , assay , assai , from Latin exagium ( “ weight; weighing, testing on the balance ” ) , from exigere + -ium .

Pronunciation [ edit ]

- ( Received Pronunciation , General American ) IPA ( key ) : /ˈɛs.eɪ/ (1), IPA ( key ) : /ɛˈseɪ/ (2-4)

- Rhymes: -ɛseɪ

- Homophone : ese

Noun [ edit ]

essay ( plural essays )

- 2013 January, Katie L. Burke, “Ecological Dependency”, in American Scientist [1] , volume 101 , number 1, archived from the original on 9 February 2017 , page 64 : In his first book since the 2008 essay collection Natural Acts: A Sidelong View of Science and Nature , David Quammen looks at the natural world from yet another angle: the search for the next human pandemic, what epidemiologists call “the next big one.”

- ( obsolete ) A test , experiment ; an assay .

- 1861 , E. J. Guerin, Mountain Charley , page 16 : My first essay at getting employment was fruitless; but after no small number of mortifying rebuffs from various parties to whom I applied for assistance, I was at last rewarded by a comparative success.

- 1988 , James McPherson, Battle Cry of Freedom , Oxford, published 2003 , page 455 : This was Lee's first essay in the kind of offensive-defensive strategy that was to become his hallmark.

- ( philately , finance ) A proposed design for a postage stamp or a banknote .

Derived terms [ edit ]

- argumentative essay

- automated essay scoring

- eight-legged essay

- essay question

- photo-essay

- photo essay

Related terms [ edit ]

Translations [ edit ], etymology 2 [ edit ].

From Middle French essayer , essaier , from Old French essaiier , essayer , essaier , assaiier , assayer , assaier , from essay , essai , assay , assai ( “ attempt; assay; experiment ” ) as above.

- ( UK , US ) IPA ( key ) : /ɛˈseɪ/

Verb [ edit ]

essay ( third-person singular simple present essays , present participle essaying , simple past and past participle essayed )

- 1900 , Charles W. Chesnutt , chapter II, in The House Behind the Cedars : He retraced his steps to the front gate, which he essayed to open.

- 1950 April, R. A. H. Weight, “They Passed by My Window”, in Railway Magazine , page 260 : The train took the slow to branch spur at the north end at a not much slower speed, then essayed the short sharply curved climb with a terrific roar, smoke rising straight from the chimney to a height of some 60 ft., the long train twisting and curling behind.

- ( intransitive ) To move forth, as into battle.

Anagrams [ edit ]

- Sayes , Seays , Sesay , eyass

Dutch [ edit ]

Etymology [ edit ].

Borrowed from English essay ( “ essay ” ) , from Middle French essai ( “ essay; attempt, assay ” ) , from Old French essai , from Latin exagium (whence the neuter gender).

- IPA ( key ) : /ɛˈseː/ , /ˈɛ.seː/

- Hyphenation: es‧say

- Rhymes: -eː

essay n ( plural essays , diminutive essaytje n )

Hypernyms [ edit ]

Descendants [ edit ], norwegian bokmål [ edit ].

Borrowed from English essay , from Middle French essai .

essay n ( definite singular essayet , indefinite plural essay or essayer , definite plural essaya or essayene )

- an essay , a written composition of moderate length exploring a particular subject

- essaysamling

References [ edit ]

- “essay” in The Bokmål Dictionary .

Norwegian Nynorsk [ edit ]

essay n ( definite singular essayet , indefinite plural essay , definite plural essaya )

- “essay” in The Nynorsk Dictionary .

- English terms derived from Proto-Indo-European

- English terms derived from the Proto-Indo-European root *h₂eǵ-

- English terms borrowed from Middle French

- English terms derived from Middle French

- English terms derived from Old French

- English terms derived from Latin

- English 2-syllable words

- English terms with IPA pronunciation

- English terms with audio links

- Rhymes:English/ɛseɪ

- Rhymes:English/ɛseɪ/2 syllables

- English terms with homophones

- English lemmas

- English nouns

- English countable nouns

- English terms with quotations

- English terms with obsolete senses

- English terms with rare senses

- en:Philately

- English verbs

- English dated terms

- English transitive verbs

- English intransitive verbs

- English heteronyms

- en:Literature

- Dutch terms borrowed from English

- Dutch terms derived from English

- Dutch terms derived from Middle French

- Dutch terms derived from Old French

- Dutch terms derived from Latin

- Dutch terms with IPA pronunciation

- Rhymes:Dutch/eː

- Dutch lemmas

- Dutch nouns

- Dutch nouns with plural in -s

- Dutch neuter nouns

- Norwegian Bokmål terms borrowed from English

- Norwegian Bokmål terms derived from English

- Norwegian Bokmål terms derived from Middle French

- Norwegian Bokmål lemmas

- Norwegian Bokmål nouns

- Norwegian Bokmål neuter nouns

- Norwegian Nynorsk terms borrowed from English

- Norwegian Nynorsk terms derived from English

- Norwegian Nynorsk terms derived from Middle French

- Norwegian Nynorsk lemmas

- Norwegian Nynorsk nouns

- Norwegian Nynorsk neuter nouns

- English entries with topic categories using raw markup

- English entries with language name categories using raw markup

- Quotation templates to be cleaned

- Cantonese terms with redundant transliterations

- Mandarin terms with redundant transliterations

- Russian terms with non-redundant manual transliterations

- Urdu terms with non-redundant manual transliterations

- Urdu terms with redundant transliterations

Navigation menu

bottom_desktop desktop:[300x250]

Where did the word essay come from?

'The etymology of the word essay is instructive. Essay is derived, by way of Middle English, from the Middle French essai . The French word was itself derived from the late Latin exagium (act of weighing).' OR 'Essay derives from the French infinitive essayer - - - '' to try'' or ''to attempt''.'

Add your answer:

What are the syllables for essay?

The word essay has two syllables. The syllables in the word are es-say.

What is the word count for an essay of an extract?

An essay that is written on exact or any topic should have a high word count. Once an essay is complete then the word count can be computed by most word processing document. Without a specific essay to review there is no exact word count.

Instead of using I in a essay paper what word do you use?

The original meaning of the word essay' is which of these?

What word can be used to replace you in an essay, what language does essay come from.

"essay" comes from the French language "essayer" and that in turn originates from the latin word "exigere" which means to test, examine.

Celery is important in the essay A Word for Autumn because it?

shows that the end of the summer has come.

What pronoun is in the word essay?

The word essay is a noun. The pronoun used to represent essay is it. Note: the letters in 'essay' do not spell any pronoun.

Is essay a french word?

The word essay derives from the Frenchinfinitive essayer, "to try" or "to attempt". In English essay first meant "a trial" or "an attempt"

What is a good word to start off a essay?

The purpose of the essay is

2000 word essay on respect?

respect is not asking for a 2000 word essay sta loco este wey

What is 750 word essay on Blood Red Ochard?

A 750 word essay on Blood Red Orchid is an essay about some aspect of Blood Red Orchid that is 750 words in length.

Can you help me with a 1000 word essay?

100 word essay of women empowerment.

How about rules on plagiarism instead? We will not do your educational essay for you.

Top Categories

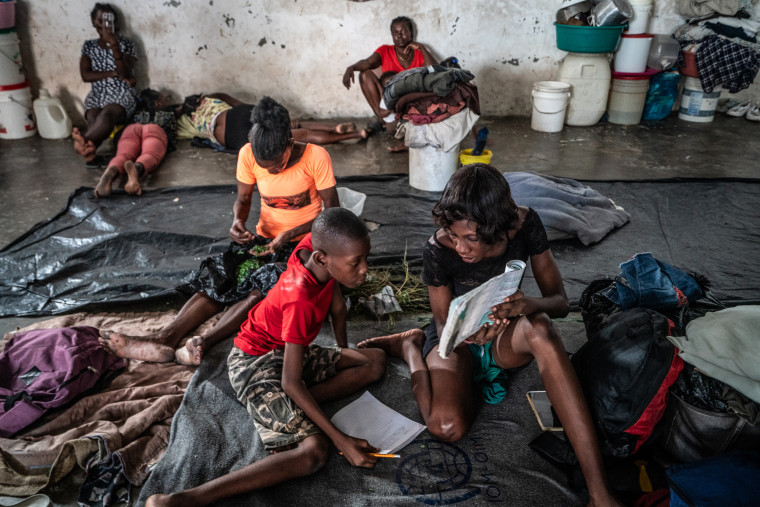

What to know about the crisis of violence, politics and hunger engulfing Haiti

A long-simmering crisis over Haiti’s ability to govern itself, particularly after a series of natural disasters and an increasingly dire humanitarian emergency, has come to a head in the Caribbean nation, as its de facto president remains stranded in Puerto Rico and its people starve and live in fear of rampant violence.

The chaos engulfing the country has been bubbling for more than a year, only for it to spill over on the global stage on Monday night, as Haiti’s unpopular prime minister, Ariel Henry, agreed to resign once a transitional government is brokered by other Caribbean nations and parties, including the U.S.

But the very idea of a transitional government brokered not by Haitians but by outsiders is one of the main reasons Haiti, a nation of 11 million, is on the brink, according to humanitarian workers and residents who have called for Haitian-led solutions.

“What we’re seeing in Haiti has been building since the 2010 earthquake,” said Greg Beckett, an associate professor of anthropology at Western University in Canada.

What is happening in Haiti and why?

In the power vacuum that followed the assassination of democratically elected President Jovenel Moïse in 2021, Henry, who was prime minister under Moïse, assumed power, with the support of several nations, including the U.S.

When Haiti failed to hold elections multiple times — Henry said it was due to logistical problems or violence — protests rang out against him. By the time Henry announced last year that elections would be postponed again, to 2025, armed groups that were already active in Port-au-Prince, the capital, dialed up the violence.

Even before Moïse’s assassination, these militias and armed groups existed alongside politicians who used them to do their bidding, including everything from intimidating the opposition to collecting votes . With the dwindling of the country’s elected officials, though, many of these rebel forces have engaged in excessively violent acts, and have taken control of at least 80% of the capital, according to a United Nations estimate.

Those groups, which include paramilitary and former police officers who pose as community leaders, have been responsible for the increase in killings, kidnappings and rapes since Moïse’s death, according to the Uppsala Conflict Data Program at Uppsala University in Sweden. According to a report from the U.N . released in January, more than 8,400 people were killed, injured or kidnapped in 2023, an increase of 122% increase from 2022.

“January and February have been the most violent months in the recent crisis, with thousands of people killed, or injured, or raped,” Beckett said.

Armed groups who had been calling for Henry’s resignation have already attacked airports, police stations, sea ports, the Central Bank and the country’s national soccer stadium. The situation reached critical mass earlier this month when the country’s two main prisons were raided , leading to the escape of about 4,000 prisoners. The beleaguered government called a 72-hour state of emergency, including a night-time curfew — but its authority had evaporated by then.

Aside from human-made catastrophes, Haiti still has not fully recovered from the devastating earthquake in 2010 that killed about 220,000 people and left 1.5 million homeless, many of them living in poorly built and exposed housing. More earthquakes, hurricanes and floods have followed, exacerbating efforts to rebuild infrastructure and a sense of national unity.

Since the earthquake, “there have been groups in Haiti trying to control that reconstruction process and the funding, the billions of dollars coming into the country to rebuild it,” said Beckett, who specializes in the Caribbean, particularly Haiti.

Beckett said that control initially came from politicians and subsequently from armed groups supported by those politicians. Political “parties that controlled the government used the government for corruption to steal that money. We’re seeing the fallout from that.”

Many armed groups have formed in recent years claiming to be community groups carrying out essential work in underprivileged neighborhoods, but they have instead been accused of violence, even murder . One of the two main groups, G-9, is led by a former elite police officer, Jimmy Chérizier — also known as “Barbecue” — who has become the public face of the unrest and claimed credit for various attacks on public institutions. He has openly called for Henry to step down and called his campaign an “armed revolution.”

But caught in the crossfire are the residents of Haiti. In just one week, 15,000 people have been displaced from Port-au-Prince, according to a U.N. estimate. But people have been trying to flee the capital for well over a year, with one woman telling NBC News that she is currently hiding in a church with her three children and another family with eight children. The U.N. said about 160,000 people have left Port-au-Prince because of the swell of violence in the last several months.

Deep poverty and famine are also a serious danger. Gangs have cut off access to the country’s largest port, Autorité Portuaire Nationale, and food could soon become scarce.

Haiti's uncertain future

A new transitional government may dismay the Haitians and their supporters who call for Haitian-led solutions to the crisis.

But the creation of such a government would come after years of democratic disruption and the crumbling of Haiti’s political leadership. The country hasn’t held an election in eight years.

Haitian advocates and scholars like Jemima Pierre, a professor at the University of British Columbia, Vancouver, say foreign intervention, including from the U.S., is partially to blame for Haiti’s turmoil. The U.S. has routinely sent thousands of troops to Haiti , intervened in its government and supported unpopular leaders like Henry.

“What you have over the last 20 years is the consistent dismantling of the Haitian state,” Pierre said. “What intervention means for Haiti, what it has always meant, is death and destruction.”

In fact, the country’s situation was so dire that Henry was forced to travel abroad in the hope of securing a U.N. peacekeeping deal. He went to Kenya, which agreed to send 1,000 troops to coordinate an East African and U.N.-backed alliance to help restore order in Haiti, but the plan is now on hold . Kenya agreed last October to send a U.N.-sanctioned security force to Haiti, but Kenya’s courts decided it was unconstitutional. The result has been Haiti fending for itself.

“A force like Kenya, they don’t speak Kreyòl, they don’t speak French,” Pierre said. “The Kenyan police are known for human rights abuses . So what does it tell us as Haitians that the only thing that you see that we deserve are not schools, not reparations for the cholera the U.N. brought , but more military with the mandate to use all kinds of force on our population? That is unacceptable.”

Henry was forced to announce his planned resignation from Puerto Rico, as threats of violence — and armed groups taking over the airports — have prevented him from returning to his country.

Now that Henry is to stand down, it is far from clear what the armed groups will do or demand next, aside from the right to govern.

“It’s the Haitian people who know what they’re going through. It’s the Haitian people who are going to take destiny into their own hands. Haitian people will choose who will govern them,” Chérizier said recently, according to The Associated Press .

Haitians and their supporters have put forth their own solutions over the years, holding that foreign intervention routinely ignores the voices and desires of Haitians.

In 2021, both Haitian and non-Haitian church leaders, women’s rights groups, lawyers, humanitarian workers, the Voodoo Sector and more created the Commission to Search for a Haitian Solution to the Crisis . The commission has proposed the “ Montana Accord ,” outlining a two-year interim government with oversight committees tasked with restoring order, eradicating corruption and establishing fair elections.

For more from NBC BLK, sign up for our weekly newsletter .

CORRECTION (March 15, 2024, 9:58 a.m. ET): An earlier version of this article misstated which university Jemima Pierre is affiliated with. She is a professor at the University of British Columbia, Vancouver, not the University of California, Los Angeles, (or Columbia University, as an earlier correction misstated).

Patrick Smith is a London-based editor and reporter for NBC News Digital.

Char Adams is a reporter for NBC BLK who writes about race.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

also from 1590s. essay (v.) "to put to proof, test the mettle of," late 15c., from French essaier, from essai "trial, attempt" (see essay (n.)). This sense has mostly gone with the divergent spelling assay. Meaning "to attempt" is from 1640s. Related: Essayed; essaying. also from late 15c.

Origins of the essay in French history. In 16 th century France, Michel de Montaigne retired from court life at the ripe old age of 38. He wanted to live out his days doing what he loved best - writing. At his family residence, Château de Montaigne near Bordeaux, he had built a specific tower for this, which he named his 'citadel'.

Definitions John Locke's 1690 An Essay Concerning Human Understanding. The word essay derives from the French infinitive essayer, "to try" or "to attempt".In English essay first meant "a trial" or "an attempt", and this is still an alternative meaning. The Frenchman Michel de Montaigne (1533-1592) was the first author to describe his work as essays; he used the term to characterize these as ...

French Translation of "ESSAY" | The official Collins English-French Dictionary online. Over 100,000 French translations of English words and phrases. TRANSLATOR. ... In this short article, we explain and provide some examples of the most common French verb tenses you'll come across. Read more. Updating our Usage.

The term essay comes from the French for "trial" or "attempt." French author Michel de Montaigne coined the term when he assigned the title Essais to his first publication in 1580. In "Montaigne: A Biography" (1984), Donald Frame notes that Montaigne "often used the verb essayer (in modern French, normally to try) in ways close to his project, related to experience, with the sense of trying ...

The word essay comes from the French word essayer, which means "to try" or "to attempt." A sixteenth-century Frenchman named Michel de Montaigne was the first to create the modern-day definition of essay when he called his writing exercises essays, meaning that he was simply "trying" to get his thoughts on paper. ...

French Translation of "ESSAY" | The official Collins English-French Dictionary online. Over 100,000 French translations of English words and phrases. LANGUAGE. TRANSLATOR. GAMES. SCHOOLS. ... Often these editions come with long and informative introductory essays and extended commentaries. Marius, Richard A Short Guide to Writing About ...

1. Text Summary (Synthèse de texte) The text summary or synthèse de texte is one of the easiest French writing exercises to get a handle on. It essentially involves reading a text and then summarizing it in an established number of words, while repeating no phrases that are in the original text.

The word "essay" comes from the Middle French word essayer, which in its turn comes from Latin exigere meaning "to test," "examine," and "drive out." This "archaeological" linguistic journey reveals the idea behind essays, which is encouraging learners to examine their ideas concerning a particular topic in-depth and test them.

The word 'essay' comes from the old French 'essai', meaning 'trial', 'attempt', 'effort'. This might seem rather appropriate. After all, essays are an effort, as anyone who has ever written one will know. But they might be a different kind of effort to the one that they are often associated with. They are a trial, for sure ...

The word 'essay' comes from the French 'essai', which means 'attempt' or 'try-out'. The essay is the attempt to redefine knowledge. The French philosopher Michel de Montaigne is credited with the creation of the essay. The sixteenth century had been shaken by epoch-making events like the discovery of America, the Reformation and ...

Borrowed from English essay, from Middle French essai. Noun [edit] essay n (definite singular essayet, indefinite plural essay or essayer, definite plural essaya or essayene) an essay, a written composition of moderate length exploring a particular subject; Derived terms [edit] essaysamling; References [edit] "essay" in The Bokmål ...

Using evidence. Evidence is the foundation of an effective essay and provides proof for your points. For an essay about a piece of literature, the best evidence will come from the text itself ...

What's the French word for essay? Here's a list of translations. French Translation. essai. More French words for essay. le essai noun. test, trial, testing, assay, try. essayer verb.

Study with Quizlet and memorize flashcards containing terms like The term essay comes from the French word "essayer." Using a quick internet search, select the general translation for this term from the following options. A. To write B. To try, or attempt C. To persuade D. To argue, In this Twitter essay, the author traces some of the historical connections that online writing has with older ...

Best Answer. Copy. 'The etymology of the word essay is instructive. Essay is derived, by way of Middle English, from the Middle French essai. The French word was itself derived from the late Latin ...

Study with Quizlet and memorize flashcards containing terms like Essay, Essay, Idea and more. ... Comes from the french word ESSAI which means trial or test. Essay. It is a pose composition of moderate length devoted to a single topic from a limited point of view. Idea.

The essay is a very new genre of nonfiction literature developed in the early twentieth century in America. false. The term essay comes from a French word essai , meaning to try to attempt something. true. An essay should always be serious and formal in tone because it is dealing with informational material that must be accurate and precise.

The essay is a very new genre of nonfiction literature developed in the early twentieth century in America. true or false` False. The term essay comes from a French word essai , meaning to try to attempt something. true or false. True.

The term essay comes from a French word essai, meaning to try to attempt something. a. True b. False. loading. See answer. loading. plus. Add answer +5 pts. loading. Ask AI. more. Log in to add comment. Advertisement. abTal7iyabanaley is waiting for your help. Add your answer and earn points. plus. Add answer +5 pts.

Chaos has gutted Port-au-Prince and Haiti's government, a crisis brought on by decades of political disruption, a series of natural disasters and a power vacuum left by the president's assassination.

The peak high point of the plot in fiction is: Analytical pattern. The process of dividing into parts to study the whole is: Propaganda. Using the argumentative pattern to persuade a person to a particular point of view is: Study with Quizlet and memorize flashcards containing terms like Essay, Formal Essay, Diaries, journals and letters and more.

7) Pelo. From: Lyon Meaning: A term used to refer to a guy, a bloke, a fella... If a teenager says "mon pelo", they mean their boyfriend - akin to "mon mec" or "mon petit ami". Example: "Après ...

Terms in this set (18) Prosus. meaning "direct' or "straight forward". Essay. comes from the French word "essai" which means an attempt or endeavor. Formal Essay. some essayist try to present the reader with information and keep their own personalities in the background. Informal Essay.