A literature review on the design and implementation of central bank digital currencies

- Research Article

- Open access

- Published: 24 January 2024

- Volume 18 , pages 197–225, ( 2024 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Huseyin Oguz Genc ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-5997-1763 1 &

- Soichiro Takagi 1

1752 Accesses

1 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Within the last five years, research on Central Bank Digital Currencies (CBDCs) has increased with increased momentum. Particular events, such as the growth of private digital currencies, Facebook’s attempt to release a stablecoin, the long-term development of Chinese CBDC, and Covid-19, are the leading causes for this growing significant interest. Most recently, the interest converged in more specific design and implementation directions. Many scholars show particular interest in account-based retail CBDCs with interest-bearing capabilities. In contrast, few others urge caution by favoring a wholesale model that is representative of the setting of the current financial system. Unsurprisingly, the primary source of such literature stems from global financial institutions and their close central banking networks. Academia and research institutions have recently increased their focus on the potential economic and social impacts of such purported design choices. As specific design principles for CBDCs have started to take shape, the policy objectives of implementing different CBDC designs are studied from the perspective of benefits and risks. These trade-offs are either generic or related to macroeconomic and financial stability implications. Evidence exists that purported generic benefits can often be achieved without CBDCs, while the purported monetary and fiscal policy benefits rely on theoretical results that lack real-world data. Some of the risks could be amplified depending on CBDC design choices. Theoretical and alternative literature is reviewed along with the evidence from use-case applications to spot the possible shortcomings in the current stage of the design and implementation literature of CBDCs. The scope is limited to the impact on economic policies and the relevant potential socioeconomic impact. The results show that further research and debate are needed from a multidisciplinary perspective.

Similar content being viewed by others

Central Bank Digital Currencies (CBDCs): The Global Development Trends and Prospects for Use as Investment Objects

Towards Optimal Technological Solutions for Central Bank Digital Currencies

The Future of Money: Central Bank Digital Currencies

Michael Lloyd

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Central Bank Digital Currencies (CBDCs) are a topic that has gained the attention of researchers with increasing momentum in recent years. The research landscape has rapidly developed with a strong interest in upgrading public digital monetary infrastructures.

As research on CBDCs increased, specific topics have trended among researchers. Such issues have clustered around core arguments that either indicate certain events as stimulants for CBDC developments or attempt to assess the implications of introducing CBDCs. Concurrently, the institutional patterns and their preferred political choices became apparent. Many researchers have conducted in-depth research to understand the associated tradeoffs and the reasoning for those preferred CBDC design choices.

Among the narratives that have matured around scholarship on CBDCs, the design and implementation discussions have become one of the most important topics before the global-scale rollout of these new digital currency systems. This paper provides a detailed review of the fundamental debates in this realm and its relevant subjects. Another focus is to investigate whether there are skewed preferences for particular design choices and the potential reasons behind those tendencies. The findings are classified within the scope of the expected impact of CBDC design and implementation on the macro policy and financial stability. Meanwhile, alternative discussions and practical implications are also covered to draw comprehensive and diverse results. Another effort of this review is to identify critical points that the existing literature have not addressed thus far.

The paper will proceed in the following order. The next section offers a summary of the results and research methodology of the review. Section three covers an overview of the generic research on CBDCs that begins with an introduction of relevant research background. It continues with a classification of the generic design features of CBDCs and winds up with a survey of the frequently mentioned benefits, risks, and implementation costs. The fourth section deals with the theoretical results, which consist of the mainstream central banking approach to the potential macro policy and financial stability implications of different CBDC design and implementation choices. The next part of the section provides alternative research methods, covering historical discussions relevant to private and public digital currencies. The paper continues by reviewing the findings of the existing CBDC case studies that have reached the implementation stage. The final section concludes with a summary of the contributions and limitations of the research.

Summary of results and methodology

This section consists of two parts. The first provides a high-level summary of the research results, while the second part describes the methodology used in the review.

Summary of results

In a high-level overview, we identify the current state of the literature as predominantly theoretical. The leading research efforts on CBDCs stem from international institutes such as the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) and International Monetary Fund (IMF). Central bank staff of most leading economies and well-known research institutes are in arms-distance with these international institutions and are similarly active in parallel research efforts. Most of these researchers study the theoretical research on the macro policy and financial stability impact of CBDCs’ which will be covered in section four. Macroeconomic studies focus on the potential functional gains for unconventional monetary and fiscal policies and other topics, such as, welfare effects, and price stability. Financial stability research builds on the central theme of how CBDC design choices may impact financial intermediaries and the global financial order.

As a complimentary analysis, we identify the critical events highlighted within the current narratives in CBDCs research that are either implicitly or explicitly mentioned as a stimulant for the recent increase in the research and development of CBDCs. We identify four key events. These are Covid-19, China's leading position in CBDC development, the rise of Bitcoin, and the attempt by Meta (previously Facebook) to release a global digital stablecoin, namely Libra. From the 86 covered pieces of literature, the keywords “China” and “Bitcoin” are, respectively, featured in 48 and 41 of the works, whereas “Libra” and “Covid” are mentioned in 37 and 25 of those pieces. In light of these events, the political motivations for a global push for CBDC implementations could be more specifically explained. One clear trend in the literature shows that although scholars often mention Bitcoin, it is not taken as an equally strong reason for the sudden spurt in CBDC research and development. At the same time, Libra is deemed to have more of a direct stimulant effect.

There is a general tendency among many scholars to take certain innate traits of CBDCs as given benefits. However, there is abundant evidence that most of the generic benefits associated with CBDCs can be achieved with legacy financial technologies. Therefore, such claims are false or require tangible data to prove their points. For example, the decline in cash usage is asserted as a deterministic fact that mandates the need for developing advanced digital payment systems. None of the literature covered in this review has provided data about cash payments to support their claims. However, some studies do not imply a dramatic reduction in cash usage as it remains a ubiquitous means of payment in many economies [ 57 ].

Meanwhile, the offshore availability of reserve currencies in cash complicates the situation further [ 43 ]. Therefore, the methodological and scientific arguments of such claims should be debated. Another topic that accumulates strong assertions is financial inclusion. Besides the fact that no tangible data could be found in this review to support the claim that CBDCs can improve financial inclusion, the recent rollout of the Nigerian CBDC, e-Naira, has shown contrary evidence, suggesting that socioeconomic stability may be jeopardized under the disguise of financial inclusion objectives. Therefore, further research seems necessary to scrutinize the alleged benefits of CBDCs.

It is important to note that the way e-Naira’s launch was politically enforced provides clear implications that the most relevant research on CBDCs is more likely to fall within the scopes of globalism and political economy. Such matters are not directly within the scope of this paper. Nevertheless, some essential literature was surveyed to achieve the objective of a comprehensive review. In [ 31 ] underlines such a trajectory for the global financial system by highlighting that technological developments provide an opportunity to build new multipolar reserve currencies in the long term. A fundamental assertion is that such events could ameliorate the balance sheet implications of the unipolar reserve currency setting that is currently in place. The new system can help prevent disrupting the incumbent reserve currencies by creating network externalities. Another critical claim is that the adoption of CBDCs could grow through the usefulness of such currencies as a medium of exchange in international payments. In [ 47 ] reports the ongoing work within the body of G20 to establish a multipolar setting that focuses on cross-border payments. The process is proceeding quickly from its early stages as the goal is establishing common standards and some adoption within this decade. Discussions on establishing regional digital currencies other than the digital Euro are also prevalent, as [ 54 ] proposes issuing a common digital currency in Asia by the early stages of Covid-19. The authors indicate that the primary objective of such a currency would also serve the purpose of settling cross-border trade payments.

There is an overwhelming focus within the scope of central banking research to comprehend the potential functional gains of CBDCs for monetary and fiscal policy purposes. A couple of these functions are implementing negative real interest rates and introducing programmable money. Such a trend makes perfect sense as central bankers are reaching towards introducing a very significant technology. However, there needs to be more focus on the theoretical implications of CBDCs under a persistently high inflation environment. This topic is relevant within the current economic realities and may provide a rational approach to why CBDCs will be adopted without any resistance. In this respect, another important point that is abundantly clear within the reviewed literature is that public opinion is, by and large, ignored. Some central bankers propose potentially disruptive changes to how society interfaces with money, such as eliminating cash and central programming of what people can do with their money. Therefore, more research is needed to understand the perception of the public on the matter.

In the following, the detailed results of this research are presented in four categories. First, the generic research on CBDCs will be inquired. Next category deals with the mainstream theoretical research on the potential macro policy and financial stability implications of CBDCs; yet also extends into alternative topics, such as the indispensable role of central bank money in payment networks, Footnote 1 currency competition, and private and public money coexistence schemes. The last category is dedicated to the existing case studies.

Research methodology

This review conducts discourse analysis. A keyword search on Google Scholar and ProQuest was conducted as a first step. Based on the results, articles within the scope of economic policy studies with the highest citation numbers on Google Scholar and higher impact metrics on ProQuest were selected. Next, backward and forward snowballing was done to identify a group of the most cross-referenced works, and the articles irrelevant to the general scopes of either economic policies or design or implementation were eliminated. The remaining literature was reviewed, seven main themes were designated, then classified into three groups. The third group consolidated alternative research topics, which were purposefully carried out to avoid potential research bias. The evaluated literature was primarily limited to peer-reviewed articles, research reports of financial and economic research institutions, and other relevant academic material.

Overview of the generic research on CBDCs

This section begins with a simple overview of the background of CBDC research and continues with a summary of the core design features established around the scope of CBDCs. A comprehensive survey of the generic benefits, risks, and costs associated with implementing these novel digital currencies is carried out in the latter part.

Background on CBDC research

The earliest mention of CBDCs is traced back to 2014 when Zhou Xiaochuan, the governor of the People’s Bank of China (PBoC) of the time, expressed the need to study the possibility of issuing a central bank digital currency [ 63 ]. Bank of England entered the discussion in 2015 by promoting research on the costs and benefits of a new form of central bank money that could extend the holdership directly to businesses and individuals [ 24 ].

Several studies compile a set of definitions for CBDCs [ 62 , 83 ], while [ 70 ] conducts a literature review on the topic, which provides various definitions according to the potential design characteristics. The survey of different works shows a consensus on a clear description of CBDCs has yet to be reached. As a narrow definition, CBDCs are digital representations of sovereign currencies. In this regard, CBDCs differ from cash, the central bank liability in physical form. In other words, they are poised to become digital liabilities of central banks and are envisioned as the core component of national reserve money systems [ 42 ].

Meanwhile, in the broader sense, the set design choices can alter the definition depending on several characteristics, such as extending CBDCs to retail use cases and adding programmability features. If the households are direct holders of the CBDC, it would be a digital currency of cash-like characteristics that would instead represent outside money [ 68 ]. Yet, unlike the physical control of cash by the individual, the oversight of the digital ledger will be limited in the hands of central banks and trusted parties.

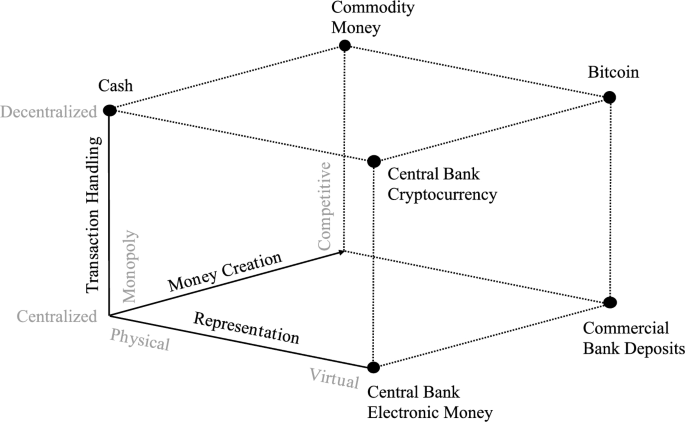

In [ 20 ] classify different forms of money according to their control structures, as shown in Fig. 1 . They categorize these structures based on three features such as (1) representation (physical vs. virtual), (2) transaction handling (centralized vs. decentralized), and (3) money creation (monopoly vs. competitive). According to this definition, commercial bank deposits are virtual, like CBDCs, and they only exist as electronic records in the accounting system. However, since commercial banks compete for deposits, which they subsequently use for credit creation, the monetary form of a CBDC depends on whether the transaction handling is designed to replicate the existing bank deposit system.

Source : Reproduced from [ 20 ]

Control structure of CBDCs vs. other types of currencies.

So far, most CBDCs are still in the trial phase. According to the CBDC Tracker of the Atlantic Council, eleven nations have already launched their CBDC projects, while twenty-one active pilots and thirty-two ongoing development projects are in the making. In total, a hundred and thirty countries are currently tracked. Footnote 2 Central banks usually publish whitepapers explaining the digital currency’s intended purpose.

Since there are many retail CBDC pilots, the research on the potential impact of CBDCs is highly theoretical [ 67 ]. A variety of scopes alternating according to the design characteristics are studied. Nevertheless, there is a general acceptance that retail CBDCs will become a reality as the future of payment agents. Therefore, the specific design choices required for their implementation will differ from a wholesale CBDC system that would instead replicate the existing financial system.

Generic design features of CBDCs

The BIS provides one of the earlier attempts among international financial institutions to issue a guideline for the essential design attributes [ 16 ]. Many later iterations have followed a similar framework. In essence, purported design choices are theoretical, yet the extent of the debate around some characteristics has become sophisticated over recent years.

Since the early phases of the design research for CBDCs, three fundamental debates revolve around the design models. The first of these models is the distribution model of CBDCs, which refers to either a retail or wholesale distribution model. A retail CBDC is a direct central bank liability, similar to cash. At the same time, the wholesale model, by default, means that the CBDC is distributed through the intermediaries in the financial system. In [ 5 ] survey the literature on the economics of retail CBDCs that study the implications of CBDCs on the financial system and policy-related issues.

Next comes the distribution model, directly related to the operating model. This function determines whether the distribution will be through intermediaries, namely the distribution of a wholesale CBDC through banks and payment system providers (PSPs) or a combination of direct/indirect operating models. It is essential to understand that an intermediated wholesale distribution prevents non-financial parties from directly executing transactions with the central banks. This setup is analogous to the current system in which accredited financial institutions, by and large, are the only parties with exclusive access to the balance sheet of central banks. Most research on CBDC design choices aims to find an optimal design to avoid the disintermediation of banks. Nevertheless, there is a strong urge to experiment with retail CBDCs to understand their potential implications on the intermediation role of banks and PSPs.

Another fundamental discussion on CBDC design is related to the access mechanism. The access design is contingent on the distribution and operating models yet procures options based on the technical grounds of how the consumers will interface with the CBDC ledger. Widely discussed options are token-based, account-based, or a combination of both, referred to as the hybrid model. The token-based model is reminiscent of digital currencies such as Bitcoin, which may provide anonymous peer-to-peer payments. Many researchers highlight that the token-based access model may provide privacy to users. On the other hand, an account-based retail CBDC model may allow individuals and corporations to open an account at the central bank ledgers, which on the contrary, is directly linked to their identities.

In [ 36 ] present a survey of these design choices for CBDCs, provided in Table 1 . Based on this categorization, most of the material reviewed in this paper falls under a particular design set. In [ 7 ] provide a comprehensive design study on the technical considerations of CBDCs, such as ledger infrastructure and identity management. In [ 1 ] focus on the identity scheme integration into CBDCs per se, which may get a lot more attention soon. Neither of these topics is included within the scope of this paper, yet they are among the most crucial subjects to study to have an in-depth understanding of the design and implementation process of CBDCs.

Benefits, risks, and costs for CBDCs

This section reviews the literature on the potential benefits and risks of prospective CBDC implementations from a generic perspective. A summary is provided in Table 2 . Lastly, a discussion on the potential costs of CBDCs is also included. The disintermediation of conventional financial institutions, a critical subject of risk associated with CBDCs, is covered in detail in the next section.

The generic benefits that are expected by the introduction of CBDCs can be simplified into three categories: political benefits, technical benefits, and social benefits. At the top of the political benefits, many studies focus on the potential advantages of CBDCs over cash and bank deposits. The primarily expected usefulness against cash is the potential broadening of the tax base, which is a parallel argument to the public sector gaining the ability to execute more efficient compliance on anti-money laundering (AML) processes. There is a firm conviction among researchers that the anonymous nature of cash makes it a disadvantageous tool for preventing tax evasion. In [ 30 ] summarizes the often-cited potential benefits and risks of an account-based retail CBDC model. However, the argument that governments can improve AML enforcement needs a reality check. The current inefficiencies in AML policies are prevalent [ 64 ], yet none of the covered literature alludes to this point for supporting their improved AML prevention case for CBDCs. For example, shadow economies may shift into using privacy-focused cryptocurrencies, rendering the case of an enhanced execution of AML policies useless.

The technical benefits of CBDCs require a sophisticated technical discussion. Thus, this subject is primarily out of the scope of this paper. In [ 75 ] underscores the variety of electronic systems in the United States for wholesale and retail payments. They purport that the economic contribution of a CBDC might be limited without enough demand for such a digital infrastructure. Meanwhile, financial technology (FinTech) applications are already widely used in many locations without the active operational involvement of governments. The potential technical efficiency improvements, such as low-cost instant payment settlements, have already been achieved in many jurisdictions worldwide.

Financial inclusion is often mentioned as a social benefit of introducing CBDCs, assuming that the government provides better access to the populations that do not have access to financial services. In [ 8 ] studies a model where CBDCs can be designed to oblige banks to compete for customer deposits, which is expected to improve financial inclusion. There needs to be a clear elaboration on how CBDCs can enable such a competition to increase financial inclusion.

Another political motivation for implementing CBDCs becomes even more ambiguous as governments try to limit the growing power of FinTech companies. China is imposing stringent controls on the local FinTech giants, and the adverse global reaction against Libra has shown that governments have discontent with the excessive power of Big Tech. The logic behind such policies may be residing on financial stability concerns, which will be covered in detail in section four.

The most anticipated case for CBDCs is the potential improvements they are expected to introduce for cross-border payments. In [ 41 ] discusses the viability of interoperable CBDCs for cross-border payments. In [ 22 ] argues that a competitive foreign exchange conversion layer should be built on top of domestic CBDC infrastructures to improve cross-border payments. The authors analyze the validity of Bitcoin, stablecoins, and settlement systems operated by legacy financial technologies to take on intermediary roles. They claim that domestically interlinked payment systems should be allowed to compete with CBDCs to see if the private sector can develop more promising solutions. Also, some markets are large enough to require the private sector’s contribution, per the authors’ views. Recent developments support this popular opinion, as [ 23 ] Footnote 3 and [ 48 ] mention that China's public and private–public partnership initiatives have started cross-border payment trials.

Bank for International Settlements’ role is central to cross-border settlement trials with CBDCs. In [ 14 ] go to length to conceptualize a multi-CBDC cross-border payment system framework, which can either represent the existing banking system or radically change the infrastructure through a single infrastructure and rulebook. While the current system is expected to work in a hybrid wholesale model, the paper asserts that an integrated approach could allow central banks to combine retail CBDCs with a direct operating model. However, a practical deliberation of how such national-scale compromises could be feasible is yet to be determined. The authors are critical of Libra, as they deem the currency to increase the risk of currency substitution while admitting that CBDCs alone are insufficient to prevent the phenomenon as currency digitalization is likely to worsen the outlook for economies with weak currencies. Nevertheless, the paper purports a paradigm of national CBDC networks that coexist in a more globally interlinked system. Economic networks that consist of actors with higher trade and remittance interlinkages may work on more modular monetary alliances, such as regional or strategic currency coalitions.

As a possible solution to the credible neutrality of setting common technical and legal standards to multi-CBDC settlement networks, a most recent project by the BIS considers interfacing CBDCs with established private stablecoin conversion networks in the cryptocurrency industry [ 18 ]. While the national networks may allow modular access to domestic participants, the protocol-level design can be implemented with an interoperable infrastructure that interfaces with international liquidity protocols. This setup enables direct settlements between the participants of different CBDC networks through the desired unit of account as long as they can assure technical interoperability with an off-shore liquidity protocol. Once technical and legal standards start shaping out, such a mechanism seems interesting as the future outlook of how private–public networks may interface, which includes considerations for the interaction between CBDCs and stablecoins.

The case of cross-border payments, in particular, shows that it is essential to underscore once more that a technical discussion is necessary to achieve a comprehensive understanding of the potential improvements of CBDCs over the existing digital payment systems. Although such topics are beyond the scope of this paper, this review acknowledges the difficulty of running a design-related discussion without extending the research area to technical grounds.

CBDC implementations are expected to have potential risks. Based on their relevancy, these risks can be narrowed down to the same three categories, like the benefits. The political issues governments may face during the design and implantation of CBDCs point to a lack of regulatory expertise and higher-than-ideal government involvement in the economy. Meanwhile, technical vulnerabilities and entrenched design mistakes are some other prominent risks. The social perils are loss of financial privacy and potential loss of funds [ 7 ].

The Bank for International Settlements strongly advocates an account-based retail CBDC despite underscoring the privacy and security risks of implementing CBDCs [ 17 ]. By attaching a digital ID as an online identification service, the Bank argues that users may benefit from a wide range of financial services while upholding protection against fraud and identity theft. However, there is overwhelming evidence about database infringements that have already exposed personally identifiable information about billions of people worldwide. Footnote 4 There is also extensive data from private cryptocurrency applications that achieving the security of funds in digital platforms contains high risk. Footnote 5 Different from identification data, the public opinion on governments to run secure digital payment schemes may diminish at a broader scale due to loss of funds.

[ 2 ] provide a detailed outlook on the potential risks of using direct operating mechanisms and advise central banks to adopt a more hybrid approach to avoid reputational risks. Despite much theoretical analysis, the practical evidence for validating or falsifying such benefits and risks is limited. In [ 67 ] asserts that the research on CBDCs is too theoretical and that more pilot projects are needed to measure the real-world impact of CBDCs. They refer to the feedback from Israel and Danish central banks, which have reportedly yet to see convincing benefits for replacing the legacy financial infrastructures with CBDCs. In [ 69 ] provides a comprehensive discussion on whether the financial inclusion benefits of CBDCs are as sound as they are claimed to be.

In [ 70 ] reviews the potential costs of issuing a central bank digital currency. The author refers to possible scenarios of increasing credit costs. The author also refers to [ 82 ] the likely costs of issuing a CBDC for public use, which can theoretically lead to cost savings for currency distribution. In contrast, new hardware and security costs, such as network setup and maintenance costs, need to be clarified regarding the costs of public spending. Meanwhile, further investment is required in fraud detection and prevention of phishing attacks to ensure consumer protection to avoid inflicting costs on users in the form of lost funds.

Another cost incurred is associated with adopting CBDC payment systems [ 37 ]. The cost of hardware infrastructure to work with CBDC applications can extend to various agencies, such as merchants, mobile operators, users, and governments, potentially making adopting CBDCs costly. Such issues can particularly slow down the adoption curve if financial costs are higher for merchants and users compared to using cash and existing payment systems.

Lastly, the introduction of CBDCs may have intangible costs. Since CBDCs may herald a cashless society, many scholars claim that eliminating cash from circulation may have significant socioeconomic consequences, particularly underscoring privacy concerns. Existing evidence shows that privacy concerns are already prominent [ 9 ]. Footnote 6 Meanwhile, broader adoption of fewer CBDC protocols may amplify the attack vector against a developing financial system. This threat may lead to significant social consequences when a lack of a physical medium of exchange serves as a unit of account. A potential cyberattack can erode the public trust in the public money network and harm the robustness of economic activity by undermining the payment function of CBDCs.

Theoretical results on CBDCs

This section provides the results of the theoretical literature. The first part delves into the mainstream approach that primarily consists of macroeconomic and financial stability works. The second part covers the literature that is relevant to economic policies and CBDC design and implementation considerations yet falls outside the scope of the defined mainstream approach.

Mainstream approach

The central themes of this part are the theoretical research on monetary and fiscal policies and financial stability, which are covered in two parts. The first part probes the potential macroeconomic impact of implementing varying CBDC designs, focusing on tentative improvements for unconventional monetary and fiscal policy applications, welfare effects, and price stability policies. The second part narrows down the focus on the issue of how CBDC designs may impact financial stability. A previous literature review by the Federal Reserve [ 30 ] was used as a critical piece, while another recent article by [ 53 ] also provides a more updated literature review focused on similar themes.

Macroeconomic impact

A frequently underscored political benefit is the flexible monetary policy improvements of interest-bearing CBDCs. [ 26 ] argues that CBDCs can satisfy all essential functions of money: a nearly costless medium of exchange, a secure store of value, and a stable unit of account. The paper reviews various theoretical works on how central banks may lose monetary control and macroeconomic stability and how a CBDC may answer such systemic risks. A critical discussion revolves around the potential of utilizing interest-bearing CBDCs to break below the Zero Lower Bound (ZLB) Footnote 7 during severe adverse shocks. The claim is that central banks can use account-based CBDCs to avoid being squeezed by the ZLB limitation, Footnote 8 which could help them circumvent controversial lender-of-last-resort practices such as quantitative easing. Committing to a transparent and credible monetary policy framework, a strong sentiment toward validating price-level targeting might benefit macroeconomic stability. However, it is politically challenging to implement such a CBDC model under the current financial regime as individuals would hoard cash, particularly in developed economies. This situation would be equivalent to a bank run; therefore, achieving a completely cashless economy is necessary for adopting an interest-bearing CBDC model that can break below the zero lower bound.

In [ 29 ] assesses a practical use case for CBDCs and their implications on the ZLB. The paper contends that the central bank can use a more direct helicopter money function, which would be delivered to CBDC accounts of households. Such a tool would seek to achieve a more direct monetary policy transmission on prices and the real economy, particularly when central banks meet the ZLB limitation. The result would be the replacement of asset purchase programs used for price stability objectives during economic shocks, simultaneously showing a reverse effect on the increasing wealth inequality caused by the same unconventional policies.

In [ 65 ] argue that negative nominal interest rates and helicopter money can be more impactful, thanks to CBDCs, yet maintain that central banks can still implement such policy tools without their introduction. The paper’s main findings suggest that assuming a universally accessible, freely convertible, and interest-bearing CBDC design choice, central banks can maintain the current monetary policy practices without much practical change. The paper also argues that CBDC policy rate transmission to the secondary lending market and the real economy would be more robust.

The purported use-case of direct payments to households may be attractive to governments, particularly under the current economic outlook with weakening demand, Footnote 9 all-time high youth unemployment, Footnote 10 and global wealth imbalances. Footnote 11 By implementing programmability into such digital money vouchers, some governments may aim to engineer the effective demand to enforce demand-side policies. Footnote 12 Such an objective, however, would stir up another dispute about the duties of governments and central banks potentially becoming exceedingly interventional in the economy. Meanwhile, [ 49 , 58 , 59 ] show that Covid-19 stimulants' data resembling such policies did not achieve the desired outcomes.

In [ 32 ] suggests that central banks should focus on money supply growth instead of only taking interest rates as the focal point. They argue that McCallum’s monetary policy rule is better suited than Taylor’s rule to understand the theoretical impact of CBDCs. The authors assert that their approach can help central banks monitor money aggregates and the inflationary effect of financial innovation more effectively. They explore the tentative inflationary impact of CBDCs based on the historical behavior of the velocity of circulation. Their results indicate that CBDCs need not produce higher inflation, yet policy considerations regarding the potential design attributes exist. One particular issue highlighted is the operating model. If central banks decide on a direct operating mechanism, the authors argue that such policies may lead to further cost reduction of financial services that households receive.

Using a structural New Keynesian Phillips curve (NKPC) framework with an explicit velocity term, [ 52 ] explore the potential implications of a Central Bank Digital Currency (CBDC) issuance on aggregate fluctuations in the Indonesian economy. The study finds that a 10% decrease in money velocity, facilitated by a CBDC issuance, would reduce the inflation rate by 0.6–1.7%. The authors highlight the importance of considering money velocity for policy deliberations. The study also indicates that a larger-scale model is necessary to achieve more accurate projections on the potential impact of a CBDC issuance on aggregate fluctuations and the conduct of monetary policy.

It is essential to note that none of these studies mainly deal with a scenario where inflation remains sticky in the long run. Therefore, this subject is identified as an essential missing subject within the existing literature, and further research is necessary. In a high-emission scenario in the long term, central banks might offer CBDCs as the only option for inflation protection. In such a scenario, although adoption may not be mandatory, high levels of indirect taxing serve would as a pseudo-enforced policy.

In [ 19 ] study the long-run macroeconomic effects of a universally-accessible and interest-bearing central bank digital currency issued against government bonds and limited in nature against competing with bank deposits as a medium of exchange. They run a New Keynesian dynamic stochastic general equilibrium (DSGE) model in a closed economy to find that interest rates and distortionary taxes decrease, leading to a 3% increase in GDP. They claim that countercyclical policy for CBDCs can serve as an alternative monetary policy tool that stabilizes the business cycle when the economy faces a liquidity demand shock. Bank lending increases during such times, assuming the central bank can alter the interest rate on the CBDC and arbitrarily adjust the quantity of issuance of the CBDC.

In [ 85 ] studies the welfare-increasing policy rate conditions under which CBDCs can be run as a narrow banking facility that competes with private bank deposits while serving as a privacy-enabling payment option. In [ 37 ] finds that welfare may be lower when cash and an interest-bearing CBDC are simultaneously available and perfectly convertible. Unless the cost of carrying CBDC is less than cash, CBDC is under-utilized in a co-existence scheme.

In [ 33 ] make a contrarian argument that introducing an interest-bearing CBDC can increase bank intermediation if the central bank introduces competition to the lending market by implementing optimal CBDC deposit rates, which would intuitively increase deposits and lower loan rates. However, the empirical findings do not provide feedback on the desired welfare effect of introducing CBDC-induced competition on the monopoly of the banking sector [ 8 ].

In [ 56 ] run a money search model to study the impact of a retail CBDC introduction on interest rates, bank lending, output, and welfare. The study focuses on the policy trade-offs for CBDC designs that simultaneously compete with physical currency or bank deposits. Issuing a cash-like CBDC is desirable only if the volume of cash transactions is high. Meanwhile, a deposit-like CBDC may crowd out bank deposits; however, such an attribute may be desirable when credit market frictions are moderate and productive investment opportunities are rare. If a CBDC competes with cash and bank deposits simultaneously, the central bank becomes subject to a single interest rate restriction on a universally accessible digital currency. The results often show improvement in aggregate welfare.

In [ 4 ] seek an optimal design for a CBDC in a linear-city setup where participants can choose among cash, CBDC, and bank deposits based on their perceived levels of risk and privacy. The critical design choices for their CBDC model are based on whether it bears interest and resembles cash as an anonymous payment agent. The more CBDCs are designed similarly to either one, the more likely it is to crowd out that respective financial agent. However, if central banks choose between the two, they would opt for protecting intermediation, as the paper argues that increasing lending frictions of a deposit-like CBDC could dampen lending activities. This problem results in choosing a cash-like design choice, leading to cash disappearance if network effects are reached with a non-interest-bearing CBDC. Therefore, the authors argue that central banks should apply negative interest on CBDCs to ensure that demand for cash usage stays intact to maximize welfare effects by sustaining the most comprehensive variety of payment instruments.

Without featuring a bank run scenario, [ 76 ] run a nominal version of [ 38 ]. The study lies at the intersection of macroeconomic and financial stability discussions, thus presented as the last work to be reviewed in this part. The results demonstrate that central banks which offer token-based CBDC accounts (with anonymous payments) can achieve at most two of the three goals among the efficient allocation of resources, price stability, and financial stability.

Financial stability

This part differentiates financial stability from macro policy considerations by segregating the literature on whether introducing CBDCs would disrupt the legacy financial system. Particular topics of interest are covered, such as bank disintermediation, bank runs, currency substitution, and destabilizing effects of cross-border or regional economic interdependencies. Many researchers seek to outline conditions in which such disruptions may occur and the extent of the potential impact on banks and payment systems.

Most of the reviewed literature does not cover the scenario in which the negative interest rate policies could impact consumer behavior in ways that could negatively impact financial stability. Assuming that social awareness of negative nominal rates is negligibly low, the desired policy goals may backfire due to diminishing consumer confidence as individuals could take riskier bets in the face of negative rates. Thus, such scenarios need to be studied extensively, particularly concerning more speculative investment vehicles.

In [ 60 ] discuss the balance sheet implications of introducing CBDCs and the necessary design qualities to minimize the risk of bank runs or disintermediation. Possible scenarios on how bank deposits may shift to CBDC accounts are presented with a comprehensive thought exercise for the proposed design principles. Based on their analysis, they find a set of core design principles: adjustable interest rate, non-convertibility against reserves, non-convertibility of bank deposits into CBDCs on-demand, and the exclusive limitation of issuance of CBDCs against government securities. The model also indicates the risk of unacceptable negative interest rates in the short or long term.

In [ 21 ] analyzes the potential of negative interest rates to fail at creating the desired stabilizing economic impact. The author offers a two-tiered remuneration approach to mitigate the effects of economic shocks when the central banks need to implement negative rates. The first tier is the retail CBDCs used by households, and the interest rate on these holdings would be more attractive to avoid the risk of bank runs. Beyond a specific limit of CBDC holdings, each additional unit held in the non-household accounts would be subject to diminishing returns. Also, commercial bank liquidity may be further affected depending on the payment services central bank accounts may offer. The ability to execute online payments via central bank accounts may reduce the importance of the larger banks in a financial system that pursues liquidity concentration.

In [ 13 ] draft their proposal on a minimally invasive CBDC. The focus is on eliminating the potential risk of disintermediation for the banking sector. The outcome claims CBDCs should be designed as a direct claim on the central bank, like cash. The functional model architecture should be intermediated or hybrid to support such a system, while the CBDC should not be interest-bearing. This design aims to enable the private sector to have a robust record-keeping vehicle for the direct claims on the central bank, which primarily serves as a medium of exchange.

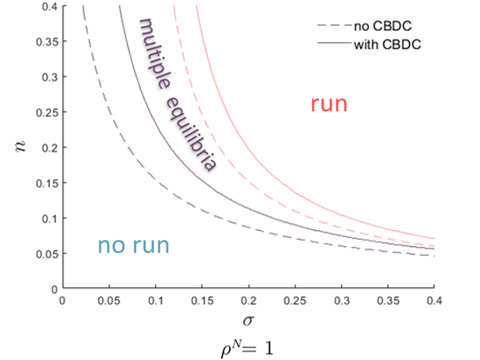

In [ 55 ] construct a model in which banks perform maturity transformation to insure depositors against idiosyncratic liquidity risk. The resulting maturity mismatch can create financial fragility, leading to a bank run by depositors following an adverse shock. The findings suggest that introducing CBDCs leads to fewer maturity transformations. At the same time, the ability of policymakers to monitor the flow of funds in real-time enables them to interfere quicker with the banks that reach fragile conditions.

In [ 46 ] assume a model based on a two-country open economy where only one issues a CBDC. They run a DSGE model to study the effects of potential international spillovers. Their results suggest that the CBDC design is crucial regarding the extent of the shock events. One primary policy recommendation in the paper is applying tight restrictions on foreigners to transact with CBDCs. At the same time, another suggestion is using a flexible interest rate policy on CBDCs. Without optimizing for such policy execution by the issuing economy, the availability of CBDC to non-residents leads to additional volatility in capital flows, exchange rates, and interest rates. CBDC issuance reduces the degree of monetary policy autonomy for the non-issuing economy, making it more than twice more sensitive to fluctuations in inflation and output. The findings suggest a first-mover advantage may be in place if CBDC adoption is inevitable in open economies.

In [ 61 ] discuss particular design choices to be made by policymakers to avoid disrupting the financial system, particularly the disintermediation of private financial institutions. The paper warns against implementing a direct access model, asserting it might lead to disintermediation. In [ 44 ] employs a theoretical framework to show the conditions under which the euro area banking system can avoid similar impediments. The results imply that the increasing role of the European Central Bank (ECB) as the lender of last resort over the past decade may be exacerbated by the introduction of CBDCs designed to prevent disruption to the credit facility and cash. Such a setting may make the ECB politically too involved, a point also made by [ 45 ], who study an account-based CBDC that serves retail and wholesale facilities. In [ 32 ] highlight a similar point regarding the increasing role of central banks in managing financial stability by underscoring that introducing CBDCs may potentially lead to further diminishing the distinction between fiscal and monetary policies.

In [ 12 , 28 , 39 , 45 , 51 ] argue that CBDCs may entirely crowd out bank deposits in weaker economies, underscoring the risk of currency substitution. Inadequate countries with weak monetary and fiscal institutions in the global hierarchy may witness increased currency substitution unless CBDC regulations are designed appropriately to protect the local currencies. Current data on cryptocurrency ownership may be supportive of this proposition. Footnote 13 In [ 74 ] indicates that unregulated global stablecoins such as Libra may exacerbate global wealth imbalances. At the same time, [ 79 ] analyzes the systematic risks of Libra for the euro area and urges a CBDC-backed full-reserve backing license model for such currencies. In [ 35 ] expects private money to coexist with CBDCs and urges central banks to initiate CBDCs as soon as possible to avoid losing political leverage against the increasing currency competition from private currencies. The central claim is that private currencies will be the method of choice for remittances thanks to the lowered transaction costs they offer for exchanging across multiple fiat currencies.

Despite the caveats, there is a more positive view towards specific CBDC designs that may enable fortification state control over domestic payment networks to increase policy robustness against potential currency substitution effects. However, the risk of currency substitution in weaker economies is expected to increase due to this trend. This topic needs a comprehensive discussion on the issue of digital currencies. For example, even though governments may attempt to crack down on private digital payment services, Footnote 14 such currencies are likely to strengthen their use cases as long as a currency is needed for cash-like transactions. Therefore, the purported benefit of CBDCs in preventing dollarization for countries with weak institutional setups may also have little validity unless governments can prevent shadow economies. After all, the source of the demand for stronger currencies results from weak governance, which is outside the scope of macro policy literature.

Alternative approaches

This section reviews the literature on CBDCs that offers an alternative perspective to mainstream research. It covers the scholarly efforts to outline the historical narrative relevant to design approaches for digital money.

In [ 73 ] lays out a more fundamental discussion that enters the realm of the philosophy of money by claiming that digitalization brings forward the immaterial essence of money as a social technology of account. Firmly believing that private digital coins induce pressure on governments to protect public sovereignty, the author expects intense currency competition in immaterial money. The paper argues that deliberate policy choices will be adopted after the experimental phase of private digital currencies to supplant the private rivals in the long run to protect public sovereignty on monetary policy. If individuals/businesses had the option to decide between fully insured central bank deposits and commercial bank deposits, the banking industry would experience a higher risk of disintermediation, as depositors may opt for holding their money in the central bank accounts in times of financial turmoil, as [ 78 ] have proposed.

In [ 40 ] elaborates on the history of financial innovation that began with money in the form of commodities leading to fiduciary money. The paper displays how the past decentralized money precedents tend to consolidate into a public monopoly. In conclusion, the expectation is that the governments will hold onto their monopolistic rights on payment networks. The author questions whether private digital currencies can exist alongside a central bank digital currency, agreeing with [ 80 ] that history suggests competing currencies are nationalized and regulated. Although CBDCs are technically more scalable and historically more favorable to be a winner as the digital form of money, the case comes with significant risks, such as opening the digital money infrastructure to a direct attack vector. Another argument refers to the currency competition envisioned by [ 50 ], which the author also deems unlikely as governments would design their CBDCs to protect their monetary sovereignty.

In [ 27 ] underscores that CBDCs are a global phenomenon and argues that Covid-19 resembles other historically significant shock events such as big wars and the Great Depression. The paper argues that such occasions bring inevitable innovations to the financial system but also acknowledges that central banks must have a comparative advantage over the private sector to achieve innovation, which is challenging. Therefore, it would strengthen the case for CBDCs if public–private cooperation is achieved. Agreeing with [ 40 ] that governments historically have an indispensable role in providing money, the paper speculates that CBDC may bring transparency and innovation to monetary policy, as elaborated in [ 26 ].

In [ 25 ] support the digitalization of public money via the introduction of CBDCs to protect the interest of state instruments, as private digital currencies are increasing at high speed. Through poised regulation, the paper argues that policymakers should strike a balance between private stablecoins and public CBDCs to avoid hampering innovative initiatives in the financial markets. The suggested high-level scheme envisions increasing the stringency of regulations on the increased level of private money adoption while advocating convertibility between the two forms of money.

A critical study missing in this realm is the comparison of CBDCs to previous financial innovations. This review provides a basic comparison between the existing digital financial infrastructure and the improvements expected from the introduction of CBDC with varying design features. However, a more comprehensive study regarding the development of other financial innovations and the development process of central bank monopoly on legal tender could add value as informative literature.

Case studies on CBDCs

The existing case studies are reviewed in this part. The results demonstrate that practical evidence is scarce for the possible implications of leading CBDC design choices. Most of the literature does not exclusively refer to particular design choices.

In [ 81 ] studies the feedback regarding e-Naira’’s adoption, which provides the unique case where a nation with a significant population has released a retail CBDC. In [10, 11] covers the social impacts of the adoption process, showing that the adoption process is dramatically slow. The level of adoption only increased to 6% as of May 2023 despite heavy restrictions on cash usage that led to social problems. On the contrary, cryptocurrency adoption is significantly higher at 50%. Therefore, Nigeria shows that the potential financial inclusion benefits of the e-Naira, as claimed by [ 71 , 72 ], are achieved by cryptocurrencies. Thus, CBDC proponents should decide whether the necessity for adopting CBDCs is to prevent disruption of the existing financial status quo or offer tangible benefits to society. The evidence from Nigeria shows that it is unlikely that CBDC achieves both.

Among the most significant pilot programs, PBoC gradually expands the e-CNY trial. The expansion occurs on a regional basis, where certain cities are selected for inclusion in the pilot. Currently, the pilot adopts an account-based hybrid retail CBDC model. Individuals use a dedicated smartphone wallet application to top-up via cash over the counter or connecting their bank accounts. Despite the strong promotion, the payment system has seen lackluster adoption, as it competes against arguably the most sophisticated digital payment applications in the world with exceptionally high usage rates. In [ 6 ] run a comprehensive review of these Chinese FinTech applications. The advanced form of the Chinese FinTech industry shows the effectiveness of such technologies regarding the improvements in financial inclusion. The authors claim that China may gain further competitive advantage thanks to introducing its CBDC and transforming the international monetary order. The regulations and the current developments on the e-CNY use cases are covered, yet the extent of the available data is slim, as China keeps usage data private.

Based on the feedback loop set through the pilot CBDC cases in the Bahamas, Uruguay, and Sweden, [ 66 ] derive that central bank regulations should foster innovation, allowing a solid private–public partnership to flourish. However, the paper underscores that most experimental work is still in theoretical scope with few pilot programs and even fewer proof of concepts. More time and experimentation are required to obtain better know-how regarding the real-world impact of implementing different CBDC designs.

A recent IMF paper by [ 77 ] focuses on the existing CBDC projects in advanced stages based on their description. These projects belong to the Bahamas, China, Eastern Caribbean, Uruguay, Sweden, and Canada. The scope of the paper is comprehensive as a wide range of topics, such as policy goals, operating models, design features, technical and legal details, and feedback from the operational side of the implementation process, are covered. All of the covered projects use an intermediated operating model. Another observation shows a clear motivation by central banks to avoid disrupting legacy financial systems while upgrading their digital money infrastructure. The authors explain how CBDCs can be designed to avoid competing with bank deposits. Another highlight in the paper concerns the opinion of Sweden's Riksbank that a centralized ledger infrastructure poses the risk of a single point of failure.

An analysis of the design of the Bahamian Sand Dollar, which is the first retail CBDC, highlights the compliance and anti-money laundering requirements despite the tax haven status of the nation [ 84 ]. The Central Bank of Bahamas officially aims to strengthen efforts against anti-money laundering through decreased cash usage. For this reason, the author argues that CBDCs are less advantageous than private cryptocurrencies in reaching adoption. Bahamian Sand Dollars adopt intermediated distribution through banks. The main objective is to prevent bank disintermediation and increase the efficiency and accessibility of the payment network to the domestic market. However, the paper suggests that increasing competition from innovative applications by private cryptocurrencies may undermine the case for a retail CBDC. Overall, the practical feedback generated by the Sand Dollar case is limited.

The conclusion provides a summary of the findings and a discussion on this review’s academic contribution and limitations.

Summary of findings

This literature review aims to identify the underlying determinants of design and implementation-related research on central bank digital currencies. The summary of results shows that there has been a global movement for implementing CBDCs ever since Covid-19 and the proliferation of other digital currencies. The simplest definition is that they are the digital representation of cash, established as a network with a novel technical architecture. The findings are clustered into three distinct approaches: generic research on CBDCs, the mainstream central banking approach, and alternative research approaches. The generic research deals with the standard design features and a comprehensive analysis of benefits, risks, and costs. This section is followed by a survey of mainstream publications on the theoretical macro policy and financial stability topics, trailed by a review of alternative research methods to diversify the scope of opinions. Lastly, the existing case studies are surveyed to identify the practical implications of CBDCs.

Several debates have revolved around the design of central bank digital currencies. Among those, this paper chooses three that are deemed the most crucial. The first debate concerns the distribution model, which can be retail or wholesale. Retail CBDCs are direct central bank liabilities, just like cash, while wholesale CBDCs are distributed through the existing intermediaries in the financial system, such as banks and payment system providers. The next critical design choice is about the operating model, which determines whether the distribution will be solely through intermediaries (indirect), central bank accounts (direct), or a combination of these models. The last significant discussion concerns the access mechanism, which is contingent on the distribution and operating models and deals with the technical grounds of how consumers will interface with the central bank ledger. The options are token-based, account-based, or a combination of both, referred to as the hybrid model. Token-based models are not directly linked to the user's identity, while the account-based model is the opposite. Different combinations of choices have different tradeoffs, and most research on CBDC design choices aims to understand these tradeoffs to find an optimal design based on policy preferences.

Research on potential benefits, risks, and costs associated with CBDCs is widely available for different design characteristics. Besides the functional monetary policy improvements purported by macro policy and financial stability research, most of the expected benefits of introducing CBDCs need more evidence to make a winning case for central bank digital currencies. One scenario that stands out is the landscape of cross-border payments, which can substantially benefit from potential efficiency improvements. Nevertheless, the design discussion for cross-border payments falls heavily within the scope of software architecture to analyze the possible enhancements of CBDC networks over existing payment systems.

Regarding the purported technical and social benefits of introducing CBDCs, such as financial inclusion and improved efficiency in payment systems, there is tangible evidence that the existing financial technologies can already achieve such functions. From private money applications, much evidence shows that security issues can lead to devastating financial losses. Large-scale cyberattacks can shake the confidence in digital public money networks and create social hazards by undermining trust in the financial system.

The majority of the mainstream literature focuses on the design of CBDCs that aims to seek a delicate balance between macro policy considerations and the prevention of disrupting the financial sector. Adopting an account-based retail CBDC is in high demand among central bankers. However, the wholesale CBDC model is often considered a preferable design feature. A primary political objective is to avoid disintermediation of the banks while maintaining the current financial system operationally identical. Therefore, some researchers prefer the intermediated access model due to its conservative nature of placing the banks in an indispensable position and its resemblance to the current functional setting between central banks and financial institutions.

The macro policy considerations focus on expected monetary and fiscal policy benefits. Two studies stand out among the many policy implications that are studied. The first is the introduction of programmable helicopter money, which anticipates a functional gain to make direct payments to households. Such a policy tool may empower state tools to experiment with the demand function of the economy instead of implementing unconventional monetary policies. Another highly anticipated functional gain for central banks is negative nominal interest rates. Some researchers argue that such a feature may bring the added benefits of a higher pass-through speed for the impact of the monetary policy during times of financial turmoil and improve transparency for policy rates.

A radical outcome of introducing negative rates may be the necessity of eliminating cash, which is arguably the most disruptive potential side effect of CBDCs. Multiple authors argue that taking cash out of circulation would be politically too tricky, indicating privacy concerns. However, many believe it will have potential benefits, such as limiting tax evasion, enforcing better AML standards, and preventing the usage of counterfeit cash. However, the expectation of a broader tax and improved AML measures may also be irrelevant since off-the-record economies are not an exclusive by-product of cash usage. Meanwhile, eliminating cash may lead to higher adoption levels for private digital currencies, increasing currency substitution in weaker economies.

Looking at the sheer extent of such implications, multiple authors underscore an increasing obscurity of the separation between fiscal and monetary policies. There are worries that the independence of the central banks may be undermined in the long term, as normalization of such a trend may further engulf central banks in politics.

Alternative literature partly focuses on the practical results from regulatory preparations and adoption challenges, while some scholars study relevant historical arguments for CBDCs. The socioeconomic impact of the digitalization of money, currency competition between private and public money, and direct access to central bank liabilities are vital themes that researchers focus on to bridge past research with the recent rise of digital currencies.

An important finding is that most of the literature disregards public opinion. No evidence supports that CBDCs are demanded by the public, and the communication of the process with the public can be deemed questionable at best, as adoption rates are low for any existing CBDC project. Therefore, research that focuses on public opinion on CBDCs is urgently needed. Notwithstanding, it is possible to speculate that adoption rates may voluntarily increase if inflation remains high in the long term. This review shows that the existing literature could pay more attention to the possibility of persistent high inflation, observing another topic for further theoretical research. To add a more profound perspective to the possibility of a continuous high inflation scenario, a dedicated comparison of the previous financial innovations and the particular policies to establish central bank monopoly on legal tender would provide insight into the upcoming releases of CBDCs and their adoption processes, which may not continue on a smooth transition path.

The practical data from the existing use cases are currently limited. The most significant use case for retail CBDCs is in Nigeria, which displays low adoption rates despite being enforced in society. The outcome of this enforcement has shown results of risking social stability. Meanwhile, meaningful empirical data from such a mass real-world experiment have yet to be retrieved. Several other central banks are ready to take their CBDC networks online. The most notable one is the retail CBDC pilot of China, the e-CNY. Nevertheless, adoption is once again low as Chinese consumers have already adopted very advanced financial technology applications, which have been at their disposal for almost a decade. All in all, as the primary purpose of the R&D efforts shifts from the design stage to the implementation phase, the use cases fail to provide the desired feedback loops for checking the validity of potential benefits and risks associated with different design characteristics.

Academic contribution and limitations

This review endorses a comprehensive and unbiased approach to spot shortcomings and concerns about the fast-growing literature on CBDCs and their design implications.

A significant contribution of this analysis is that it reveals the need for further elaboration of the practical grounds endorsed to justify the urgency for implementing CBDCs at a global level. While doing so, some of the shortcomings within the existing literature are also identified. Ample evidence shows that governments can achieve most of the purported benefits without CBDCs, which are already the reality in certain jurisdictions. Results also display privacy, security, and social risks in implementing retail CBDCs. There needs to be systematic research that considers public opinion on CBDCs. Meanwhile, more research is required to understand the potential scenario where high inflation and negative real interest rates remain sticky in the long term.

Another contribution is the identification of the preferred design choices as the implementation of CBDCs nears at a global scale. The wholesale distribution model is gaining favoritism for the early stages of implementation to avoid disrupting the financial system. The results also show no consensus between wholesale and retail CBDCs, while the latter attracts significant research among central bankers.

Although the movement of CBDC research and development is a global phenomenon, more nuance is needed regarding local considerations. The results exhibit that the literature requires a clear differentiation between local and international implications of implementing CBDCs, and discuss how these implications may differ based on the design choices. The absence of an approach that prioritizes regional implications gives reason to question the scope of CBDC research. After all the research from first-world economies and international institutions, Nigeria became the experimental ground for retail CBDCs. Our findings show that no substantial evidence suggests that Nigerian society is in demand of such a technology. Hence, the conclusive contribution is that the most crucial scope of CBDC research likely lies within the realm of political economy and globalization studies.

As for the limitations, more practical data must be collected from the existing use cases. The difficulty in obtaining sufficient data on cash usage makes it harder to analyze specific claims regarding declining cash usage, which is an often-posed reason for justifying CBDCs. Nonetheless, the most critical limitation is the exclusion of a comparative study on the software architecture of CBDCs. Although such a shift may push the research out of the scope of economic policies, technical discussions are an indispensable part of CBDC research at this point, as specific claims about improved efficiency for cross-border payments require a more comprehensive research scope.

Research data policy and data availability statements

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article (and its supplementary information files).

In [ 15 ] provides a detailed guideline of the role of central bank money in the payment networks.

Data publicly available at https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/cbdctracker/ .

The Digital Currency Institute of the People’s Bank of China, the Hong Kong Monetary Authority, the Bank of Thailand, and the Central Bank of the United Arab Emirates have conducted a six-week trial to conduct a series of real-value transactions among commercial banks. A custom distributed ledger technology-based platform was used to carry out transactions between respective CBDCs [ 23 ].

An exhaustive database for public data breaches is not publicly available. The following are some of the notable recent data exploits that append personally identifiable data: (1) The biometric ID data of the Indian digital ID scheme that even disclosed the banking details of the citizens. (2) Argentina and Turkey national ID database hacks that even include the ID photos of the individuals. (3) Most recently, the personal information of approximately 1 billion Chinese citizens, including names, addresses, national ID numbers, contact information, and criminal records, were hacked.

The cryptocurrency company, Rekt DAO, maintains a comprehensive database of the hacking events that lead to the loss of funds in the cryptocurrency ecosystem. Data publicly available at https://rekt.news/ .

According to the public survey by the Federal Reserve, among more than 2000 commenters, two-thirds have negative opinions about the release of a CBDC in the United States, as “the most common concerns were over financial privacy, financial oppression, and the risk of disintermediating the banking system.”.

Zero Lower Bound is not a deterministic limitation but one that is generally recognized to apply. In practice, central banks have applied negative policy rates. See [ 34 ] for a detailed explanation.

The discussion on negative nominal interest rates precedes CBDCs. In [ 3 ] theorizes a potential solution by applying different time-varying interest rates on electronic and paper money. The peg between paper and electronic money breaks temporarily until desired results are obtained. Electronic money remains the unit of account, and inflation happens relative to paper money. This approach may be susceptible to cash being voluntarily eliminated from circulation depending on the execution of central bank policies during market downturns. CBDC technology is offered as a possible solution for eliminating the systemic risks due to current monetary policy limitations.

World Bank data for Households and NPISHs final consumption expenditure (% of GDP). Data publicly available at https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NE.CON.PRVT.ZS .

World Bank data for youth unemployment as a percentage of labor force. Data publicly available at https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SL.UEM.1524.ZS .

A specific indicator we have in mind here is the change in income gains of the top 1% against the rest of the population worldwide. The demand continues to weaken as the rich can only spend a certain amount of their wealth. For a detailed guide on the historical trends in the subject, see [ 78 ].

In [ 86 ] claims that the Chinese CBDC should be superior to the existing FinTech systems in all aspects to justify its adoption by public opinion. According to the author, such superiority can be achieved by instituting the programmability function via smart contracts.

Although different surveys may show different results, a market research company, GWI, publishes quarterly data on cryptocurrency ownership by country. There is an evident trend of crypto asset ownership in economies that suffer from high inflation. Details available at https://datareportal.com/reports/digital-2022-july-global-statshot .

In August 2022, the Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) sanctioned the Ethereum mixer service Tornado Cash, which helps transactions on the Ethereum blockchain to be anonymized. The sanction decision was followed by the arrest of a developer of the service in the Netherlands.

Adams, M., Boldrin, L., Ohlhausen, R., & Wagner, E. (2021). An integrated approach for electronic identification and central bank digital currencies. Journal of Payments Strategy & Systems, 15 (3), 287–304.

Google Scholar

Adrian, T., & Manchini-Griffoli, T. (2019). The rise of digital money (NOTE/19/01; Fintech Notes). International Monetary Fund. https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/fintech-notes/Issues/2019/07/12/The-Rise-of-Digital-Money-47097

Agarwal, R., & Kimball, M. (2015). Breaking through the zero lower bound (IMF Working Papers 15/224). International Monetary Fund. https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WP/Issues/2016/12/31/Breaking-Through-the-Zero-Lower-Bound-43358

Agur, I., Ari, A., & Dell’Ariccia, G. (2022). Designing central bank digital currencies. Journal of Monetary Economics, 125 , 62–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmoneco.2021.05.002

Article Google Scholar

Ahnert, T., Assenmacher, K., Hoffman, P., Leonello, A., Monnet, C., & Porcellacchia, D. (2022). The economics of central bank digital currency (Working Paper Series No 2713). European Central Bank.

Allen, F., Gu, X., & Jagtiani, J. (2022). Fintech, cryptocurrencies, and CBDC: Financial structural transformation in China. Journal of International Money and Finance, 124 , 102625. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jimonfin.2022.102625

Allen, S., Čapkun, S., Eyal, I., Fanti, G., Ford, B. A., Grimmelmann, J., Juels, A., Kostiainen, K., Meiklejohn, S., Miller, A., Prasad, E., Wüst, K., & Zhang, F. (2020). Design choices for central bank digital currency: Policy and technical considerations (NBER Working Paper No. 27634). National Bureau Of Economıc Research. http://www.nber.org/papers/w27634

Andolfatto, D. (2021). Assessing the impact of central bank digital currency on private banks. The Economic Journal (London), 131 (634), 525–540. https://doi.org/10.1093/ej/ueaa073

Anthony, N. (2022). Update: two thirds of commenters concerned about CBDC . Cato.org. Retrieved August 27, 2022, from https://www.cato.org/blog/update-two-thirds-commenters-concerned-about-cbdc

Anthony, N. (2023). Nigerians’ rejection of their CBDC Is a cautionary tale for other countries | Cato Institute . https://www.cato.org/commentary/nigerians-rejection-their-cbdc-cautionary-tale-other-countries

Anthony, N. (2023). Nigeria’s CBDC was not chosen. It Was Forced | Cato at Liberty Blog . https://www.cato.org/blog/nigerias-cbdc-was-not-chosen-it-was-forced

Arauz, A. (2021). The international hierarchy of money in cross-border payment systems: Developing countries’ regulation for central bank digital currencies and Facebook’s Stablecoin. International Journal of Political Economy, 50 (3), 226–243. https://doi.org/10.1080/08911916.2021.1984728

Auer, R., & Böhme, R. (2021). Central bank digital currency: The quest for minimally invasive technology (BIS Working Papers No. 948). Bank for International Settlements. https://www.bis.org/publ/work948.htm

Auer, R., Haene, P., & Holden, H. (2021). Multi-CBDC arrangements and the future of cross-border payments (BIS Papers No. 115). Bank for International Settlements. https://www.bis.org/publ/bppdf/bispap115.htm

Bank for International Settlements. (2003). The role of central bank money in the payment systems . (Committee on Payment and Settlement Systems). https://www.bis.org/cpmi/publ/d55.pdf .

Bank for International Settlements. (2018). Central bank digital currencies (CPMI, Markets Committee Papers No. 174). https://www.bis.org/cpmi/publ/d174.pdf

Bank for International Settlements. (2021). Annual economic report . Bank for International Settlements. https://www.bis.org/publ/arpdf/ar2021e.pdf

Bank for International Settlements. (2023). Cross-border exchange of wholesale CBDCs using automated market-makers [Interim report]. Bank for International Settlements.

Barrdear, J., & Kumhof, M. (2022). The macroeconomics of central bank digital currencies. Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control, 142 , 104148. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jedc.2021.104148

Article MathSciNet Google Scholar

Berentsen, A., & Schar, F. (2018). The case for central bank electronic money and the non-case for central bank cryptocurrencies. Quarterly Research Journals, 100 (2), 97–106. https://doi.org/10.20955/r.2018.97-106

Bindseil, U. (2019). Central bank digital currency: Financial system implications and control. International Journal of Political Economy, 48 (4), 303–335. https://doi.org/10.1080/08911916.2019.1693160

Bindseil, U., & Pantelopoulos, G. (2022). Towards the holy grail of cross-border payments. SSRN Electronic Journal . https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4057995

BIS Innovation Hub. (2022). Project mBridge: Connecting economies through CBDC . https://www.bis.org/publ/othp59.htm