- Courses & Events

- In The News

- Video Clips

Norcross & Lambert 2018 metanalysis: Psychotherapy Relationships that Work III

Psychotherapy © 2018 American Psychological Association 2018, Vol. 55, No. 4, 303–315

0033-3204/18/$12.00

http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/pst0000193

Psychotherapy Relationships That Work III

John C. Norcross Michael J. Lambert University of Scranton Brigham Young University

This article introduces the journal issue devoted to the most recent iteration of evidence-based psycho- therapy relationships and frames it within the work of the Third Interdivisional American Psychological Association Task Force on Evidence-Based Relationships and Responsiveness. The authors summarize the overarching purposes and processes of the Task Force and trace the devaluation of the therapy relationship in contemporary treatment guidelines and evidence-based practices. The article outlines the meta-analytic results of the subsequent 16 articles in the issue, each devoted to the link between a particular relationship element and treatment outcome. The expert consensus deemed 9 of the relationship elements as demonstrably effective, 7 as probably effective, and 1 as promising but with insufficient research to judge. What works—and what does not—in the therapy relationship is emphasized through- out. The limitations of the task force work are also addressed. The article closes with the Task Force’s formal conclusions and 28 recommendations. The authors conclude that decades of research evidence and clinical experience converge: The psychotherapy relationship makes substantial and consistent contri- butions to outcome independent of the type of treatment.

Clinical Impact Statement Question: What, specifically, is effective in the powerful psychotherapy relationship? Findings: Clinicians can use these meta-analytic conclusions and the practice recommendations of the Task Force on Evidence-Based Relationships and Responsiveness to provide what works in the relation- ship and simultaneously to avoid what does not work. Meaning: Based on original meta-analyses, experts deemed nine of the relationship elements as demonstrably effective, seven as probably effective, and one as promising. Next Steps: Future directions are to disseminate these findings to practice communities, to implement them in training programs, and to examine the interrelations of the effective elements of the relationship.

Keywords: psychotherapy, therapeutic relationship, psychotherapy outcome, meta-analysis, evidence- based practice

Ask patients what they find most helpful in their psychotherapy. Ask practitioners which component of psychotherapy ensures the highest probability of success. Ask researchers what the evidence favors in predicting effective psychological treatment. Ask psy- chotherapists what they are most eager to learn about (Tasca et al., 2015). Ask proponents of diverse psychotherapy systems on what

John C. Norcross, Department of Psychology, University of Scranton; Michael J. Lambert, Department of Psychology, Brigham Young Univer- sity.

This article is adapted, by special permission of Oxford University Press, by the same authors in Norcross, J. C., & Lambert, M. J. (Eds.). (2019), Psychotherapy relationships that work (3rd ed., Vol. 1). New York, NY: Oxford University Press. The Interdivisional APA Task Force on Evidence-Based Psychotherapy Relationships and Responsiveness was co- sponsored by the APA divisions of Psychotherapy (29) and Counseling Psychology (17).

Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to John C. Norcross, Department of Psychology, University of Scranton, Scranton, PA 18510-4596. E-mail: [email protected]

point they can find commonality. The probable answer, for all these questions, is the psychotherapy relationship, the healing alliance between the client and the clinician.

In 1999, the American Psychological Association (APA) Divi- sion of Psychotherapy first commissioned a task force to identify, operationalize, and disseminate information on empirically sup- ported therapy relationships. That task force summarized its find- ings and detailed its recommendations in a 2001 special issue of this journal, Psychotherapy, and in a 2002 book (Norcross, 2002). In 2009, the APA Division of Psychotherapy along with the Division of Clinical Psychology commissioned a second task force on evidence-based therapy relationships to update the research base and clinical practices on the psychotherapist–patient relation- ship. A second edition of the book (Norcross, 2011) and a second special issue of this journal, appearing in 2011, did just that.

Our aim for the third task force and the third iteration of this special journal issue, Evidence-Based Psychotherapy Relation- ships III, is to build upon and update the first two task forces in the research evidence for the impacts of relational elements, the number of those elements reviewed, and the rigor of the meta- analyses. In short, this issue summarizes the best available

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers. This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

NORCROSS AND LAMBERT

research and clinical practices on numerous facets of the ther- apy relationship.

In this article, we frame this special issue on evidence-based psychotherapy relationships within the work of the Third Interdi- visional APA Task Force on Evidence-Based Relationships and Responsiveness, which was cosponsored by the Society for the Advancement of Psychotherapy (APA Division 29) and the Soci- ety for Counseling Psychology (APA Division 17). We begin by summarizing the overarching purposes and processes of the Task Force and trace the devaluation of the therapy relationship in contemporary treatment guidelines and evidence-based practices. We provide a numerical summary of the meta-analytic results and the evidentiary strength of the subsequent 16 articles in the issue, each devoted to a particular relationship element. We then empha- size what works—and what does not—in the relationship. Prom- inent limitations of the task force work are highlighted. We present the formal conclusions and recommendations of the Third Inter- divisional Task Force. Those statements, approved by the 10 members of the Steering Committee, refer to the work in both this special issue on therapy relationships and another volume on treatment adaptations or relational responsiveness (Norcross & Wampold, 2019).

The Third Interdivisional Task Force

The dual purposes of the Interdivisional APA Task Force on Evidence-Based Relationships and Responsiveness were to iden- tify effective elements of the therapy relationship and to determine effective methods of adapting or tailoring therapy to the individual patient on the basis of his or her transdiagnostic characteristics. In other words, the Task Force was interested in both what works in general and what works for particular patients.

For the purposes of our work, we again adopted Gelso and Carter’s (1985, 1994) operational definition of the relationship: The therapeutic relationship is the feelings and attitudes that the therapist and the client have toward one another, and the manner in which these are expressed. This definition is quite general, and the phrase “the manner in which it is expressed” potentially opens the relationship to include everything under the therapeutic sun (for an extended discussion, see Gelso & Hayes, 1998). Nonethe- less, it serves as a concise, consensual, theoretically neutral, and sufficiently precise definition.

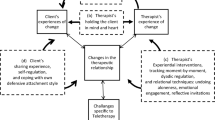

Treatment methods and the therapeutic relationship constantly shape and inform each other. Both clinical experience and research evidence point to a complex, reciprocal interaction between the interpersonal relationship and the instrumental methods. The rela- tionship does not exist apart from what the therapist does in terms of method, and we cannot imagine any treatment methods that would not have some relational impact. Put differently, treatment methods are relational acts (Safran & Muran, 2000).

For historical and research convenience, the field has distin- guished between relationships and techniques. Words like “relat- ing” and “interpersonal behavior” describe how therapists and clients behave toward each other. By contrast, terms like “tech- nique” or “intervention” describe what is done by the therapist. In research and theory, we often treat the how and the what—the relationship and the intervention, the interpersonal and the instru- mental—as separate categories. In reality, of course, what one does and how one does it are complementary and inseparable. Trying to

remove the interpersonal from the instrumental may be acceptable in research, but it is a fatal flaw when the aim is to extrapolate research results to clinical practice (see the 2005 special issue of Psychotherapy on the interplay of techniques and therapeutic relationship). In other words, the value of a treatment method is inextricably bound to the relational context in which it is applied.

The Task Force applies psychological science to the identifica- tion and promulgation of effective psychotherapy. It does so by expanding or enlarging the typical focus of evidence-based prac- tice to therapy relationships. Focusing on one area—in this case, the therapeutic relationship—may unfortunately convey the im- pression that this is the only area of importance. We review the scientific literature on the therapy relationship and provide clinical recommendations based on that literature in ways, we trust, that do not degrade the simultaneous contributions of treatment methods, patients, or therapists to outcome.

An immediate challenge to the Task Force was to establish the inclusion and exclusion criteria for the elements of the therapy relationship. We readily agreed that the traditional features of the therapeutic relationship—the alliance in individual therapy, cohe- sion in group therapy, and the Rogerian facilitative conditions, for example—would constitute core elements. We further agreed that discrete, relatively nonrelational techniques were not part of our purview; therapy methods were considered for inclusion if their content, goal, and context were inextricably interwoven into the emergent therapy relationship. We settled on several “relational” methods (e.g., collecting real-time client feedback, repairing alli- ance ruptures, facilitating emotional expression, and managing countertransference) because these methods are deeply embedded in the interpersonal character of the relationship itself. As “meth- ods,” it also proves possible to randomly assign patients to one treatment condition with the method (for instance, feedback or rupture repairs) and other patients to a treatment without them. But which relational behaviors to include and which to exclude under the rubric of the therapy relationship bedeviled us, as it has the field.

We struggled on how finely to slice the therapy relationship. As a general rule, we opted to divide the meta-analytic reviews into smaller chunks so that the research conclusions were more specific and the practice and training implications more concrete.

We consulted psychotherapy experts, the research literature, and potential authors to discern whether there were sufficient numbers of studies on a particular relationship element to conduct a sys- tematic review and meta-analysis. Three relational elements— therapist humor, self-doubt/humility, and deliberate practice— exhibited initial research support but not a sufficient number of empirical studies for a meta-analysis. Five new relationship be- haviors surpassed our research threshold, and thus, we added the real relationship, self-disclosure, immediacy, emotional expres- sion, and treatment credibility.

Once these decisions were finalized, we commissioned original meta-analyses on the relationship elements. Authors followed a comprehensive chapter structure and specific guidelines for their meta-analyses. The analyses quantitatively linked the relationship element to psychotherapy outcome. Outcome was primarily de- fined as distal posttreatment outcomes. Authors specified the out- come criterion when a particular study did not use a typical end-of-treatment measure; indeed, the type of outcome measure was frequently analyzed as a possible moderator of the overall

effect size. This emphasis on distal outcomes sharpened our focus on “what works” and countered the partial truth that some of the meta-analyses examining predominantly proximal outcome mea- sures in earlier iterations of the task force merely illustrated that “the good stuff in session correlates with other good stuff in session.” We have responded to that criticism in these articles while also explicating several consequential process linkages.

When the meta-analyses were finalized, the 10-person Steering Committee (identified in the Appendix) independently reviewed and rated the evidentiary strength of the relationship element according to the following criteria: number of empirical studies, consistency of empirical results, independence of supportive stud- ies, magnitude of association between the relationship element and outcome, evidence for causal link between relationship element and outcome, and the ecological or external validity of research. Using these criteria, experts independently judged the strength of the research evidence as demonstrably effective, probably effec- tive, promising but insufficient research to judge, important but not yet investigated, or not effective.

We then aggregated the individual ratings to render a consensus conclusion on each relationship element. These conclusions are presented later in this article, as are 28 recommendations approved by all members of the Steering Committee. Our deliberations relied on expert opinion referencing best practices, professional consensus using objective rating criteria, and, most importantly, meta-analytic reviews of the research evidence. But these were all human decisions—open to cavil, contention, and revision.

Following this introductory article are 16 articles on particular facets of the psychotherapy relationship and their relation to treat- ment outcome. Except for this introduction, each article uses identical major headings and consistent structure, as follows:

Introduction (untitled): Introduce the relationship element in a couple of reader-friendly paragraphs.

Definitions and Measures: Define in theoretically neutral language the relationship element. Identify any highly similar constructs from diverse theoretical traditions. Review the popular measures used in the research and included in the ensuing meta-analysis.

Clinical Examples: Provide a couple of concrete examples of the relationship behavior under consideration.

Results of Previous Reviews: Offer a quick synopsis of the findings of previous meta-analyses and systematic reviews on the topic.

Meta-Analytic Review: Compile all available empirical stud- ies linking the relationship behavior to treatment outcome (distal, end-of-treatment outcome); report results of the liter- ature search, preferably by means of a PRISMA flowchart if space allows; include only actual psychotherapy studies (not analogue studies); use a random-effects model; report the effect size as both weighted r and d (or g); provide a summary table for individual studies (if ?50; if ?50, provide a sup- plemental online appendix); perform and report a test of

homogeneity (Q and I); include a fail-safe statistic to address the file-drawer problem; and provide a table or funnel plot for each study in the meta-analysis (if fewer than 50 studies).

Mediators and Moderators: Present the results of the poten- tial mediators and moderators of the association between the relationship element and treatment outcome.

Patient Contributions: Address the patient’s contribution to that relationship and the distinctive perspective he or she brings to the interaction.

Limitations of the Research: Point to the major limitations of the research conducted to date.

Diversity Considerations: Outline how diversity (e.g., gender, race/ethnicity, sexual orientation, and socioeconomic status) fares in the research studies and the meta-analytic results.

Therapeutic Practices: Highlight the practice implications from the foregoing research, primarily in terms of the thera- pist’s contribution and secondarily in terms of the patient’s perspective. Go beyond the numerical data to provide prac- tical, bulleted clinical practices.

(Three sections of the book chapters—landmark studies, evi- dence for causality, and training implications—were jettisoned for these journal articles in the interest of space. Readers can access these sections and more methodological details in the book itself; Norcross & Lambert, 2019).

Insisting on quantitative meta-analyses for all articles (with one exception) enables direct estimates of the magnitude of association in the form of effect sizes. These are standardized difference between two group means, say psychotherapy and a control, di- vided by the (pooled) standard deviation. The resultant effect size is in standard deviation units. Both Cohen’s d and Hedges’s g estimate the population effect size.

The meta-analyses in this issue used the weighted r and its equivalent d or g. Most of the articles analyzed studies that were correlational in nature; for example, studies that correlated the patient’s ratings of empathy during psychotherapy with their out- come at the end of treatment. The correlation coefficients (r) were then converted into d or g. We did so for consistency among the meta-analyses, enhancing their interpretability (square r for the amount of variance accounted for) and enabling direct compari- sons of the meta-analytic results to one another as well as to d (the effect size typically used when comparing the relative effects of two treatments). In all of these analyses, the larger the magnitude of r or d, the higher the probability of patient success in psycho- therapy based on the relationship variable under consideration.

Table 1 presents several practical ways to interpret r and d in behavioral health care. By convention (Cohen, 1988), an r of .10 in the behavioral sciences is considered a small effect, .30 a medium effect, and .50 a large effect. By contrast, a d of .30 is considered a small effect, .50 a medium effect, and .80 a large effect. Of course, these general rules or conventions cannot be dissociated from the context of decisions and comparative values. There is little inherent value to an effect size of 2.0 or 0.2; it depends on what benefits can be achieved at what cost (Smith, Glass, & Miller, 1980).

PSYCHOTHERAPY RELATIONSHIPS THAT WORK III

Practical Interpretation of d and r Values

evidence-based treatments in psychotherapy (Barlow, 2000; Nor- cross, Hogan, Koocher, & Maggio, 2017).

Efforts to promulgate evidence-based psychotherapies have been noble in intent and timely in distribution. They are praise- worthy efforts to distill scientific research into clinical applications and to guide practice and training. They wisely demonstrate that, in a climate of accountability, psychotherapy stands up to empir- ical scrutiny with the best of health-care interventions. And within psychology, these have proactively counterbalanced documents that accorded primacy to biomedical treatments for mental disor- ders and largely ignored the outcome data for psychological ther- apies. On many accounts, then, the extant efforts addressed the realpolitik of the socioeconomic situation (Messer, 2001; Nathan & Gorman, 2015).

At the same time, many practitioners and researchers alike have found these recent efforts to codify evidence-based treatments seriously incomplete. Although scientifically laudable in their in- tent, these efforts largely ignored the therapy relationship and the person of the therapist. Practically all treatment guidelines have followed the antiquated medical model of identifying only partic- ular treatment methods for specific diagnoses: Treatment A for Disorder Z. If one reads the documents literally, disembodied providers apply manualized interventions to discrete DSM and ICD disorders. Not only is the language offensive on clinical grounds to some practitioners, but the research evidence is weak for validating treatment methods in isolation from specific thera- pists, the therapy relationship, and the individual patient.

Suppose we asked a neutral scientific panel from outside the field to review the corpus of psychotherapy research to determine what is the most powerful phenomenon we should be studying, practicing, and teaching. Henry (1998, p. 128) concluded that such a panel,

would find the answer obvious, and empirically validated. As a general trend across studies, the largest chunk of outcome variance not attributable to preexisting patient characteristics involves individual therapist differences and the emergent therapeutic relationship be- tween patient and therapist, regardless of technique or school of therapy. This is the main thrust of decades of empirical research.

What is missing in treatment guidelines, now across 5 decades of research, are the person of the therapist and the therapeutic relationship.

Person of the Therapist

Most practice or treatment guideline compilations depict inter- changeable providers performing treatment procedures. This stands in marked contrast to the clinician’s and the client’s expe- rience of psychotherapy as an intensely interpersonal and deeply emotional experience. Although efficacy research has gone to considerable lengths to eliminate the individual therapist as a variable that might account for patient improvement, the inescap- able fact of the matter is that it is simply not possible to mask the person and the contribution of the therapist (Castonguay & Hill, 2017; Orlinsky & Howard, 1977). The curative contribution of the person of the therapist is, arguably, as evidence based as manual- ized treatments or psychotherapy methods (Hubble, Wampold, Duncan, & Miller, 2011).

Cohen’s benchmark

Large Medium Small

Type of effect

Beneficial Beneficial Beneficial Beneficial Beneficial Beneficial Beneficial Beneficial Beneficial No effect No effect No effect Detrimental Detrimental

Percentile of treated patientsa

Success rate of treated patients (%)b

.80 .50 .70 .60 .50 .30 .40

.30 .20 .10 .10 .00 0

?.10 ?.20 .10 ?.30

Given the large number of factors contributing to patient suc- cess, and the inherent complexity of psychotherapy, we do not expect large, overpowering effects of any one relationship behav- ior. Instead, we expect to find a number of helpful facets. And that is exactly what we find in the following articles—beneficial, small-to-medium-sized effects of several elements of the complex therapy relationship.

For example, Elliott, Bohart, Watson, and Murphy (2018) con- ducted a meta-analysis of 82 studies that investigated the associ- ation between therapist empathy and patient success at the end of treatment. Their meta-analysis, involving a total of 6,138 patients, found a weighted mean r of .28. As shown in Table 1, this is a medium effect size. The corresponding d was .58. Relative to studies that compare one psychotherapy with another psychother- apy (where typical ds tend to be less than .20; Lambert, 2013; Wampold & Imel, 2015), a d of .58 is quite high. These numbers translate into happier and healthier clients; that is, clients with more empathic therapists tend to progress more in treatment and experience greater improvement.

Therapy Relationship

Recent decades have witnessed the controversial compilation of practice guidelines and evidence-based treatments in mental health. In the United States and other countries, the introduction of such guidelines has provoked practice modifications, training re- finements, and organizational conflicts. Insurance carriers and government policymakers increasingly turn to such guidelines to determine which psychotherapies to approve and fund. Indeed, along with the negative influence of managed care, there is prob- ably no issue more central to clinicians than the evolution of

Adapted from Cohen (1988); Norcross, Hogan, Koocher, and Mag- gio (2017); and Wampold and Imel (2015). a Each effect size can be conceptualized as reflecting a corresponding percentile value; in this case, the percentile standing of the average treated patient after psychotherapy relative to untreated patients. b Each effect size can also be translated into a success rate of treated patients relative to untreated patients; a d of .80, for example, would translate into approxi- mately 70% of patients being treated successfully compared with 50% of untreated patients.

Multiple and converging sources of evidence indicate that the person of the psychotherapist is inextricably intertwined with the outcome of psychotherapy. A large, naturalistic study estimated the outcomes attributable to 581 psychotherapists treating 6,146 patients in a managed care setting. About 5% of the outcome variation was due to therapist effects and 0% was due to specific treatment methods (Wampold & Brown, 2005).

Quantitative reviews of therapist effects in psychotherapy out- come studies show consistent and robust therapist effects, probably accounting for 5%–8% of psychotherapy outcome effects (Barkham, Lutz, Lambert, & Saxon, 2017; Crits-Christoph et al., 1991). The Barkham study combined data from four countries, 362 therapists, 14,254 clients, and four outcome measures. They found that about 8% of the variance in outcome was due to the therapist, so-called therapist effects. Moreover, the size of the therapist effect was strongly related to initial client severity. The more disturbed a client was at the beginning of therapy, the more it mattered which therapist the client saw.

A controlled study examining therapist effects in the outcomes of cognitive–behavioral therapy is instructive (Huppert et al., 2001). In the Multicenter Collaborative Study for the Treatment of Panic Disorder, considerable care was taken to standardize the treatment, the therapist, and the patients to increase the experi- mental rigor of the study and to minimize therapist effects. The treatment was manualized and structured, the therapists were iden- tically trained and monitored for adherence, and the patients were rigorously evaluated and relatively uniform. Nonetheless, the ther- apists significantly differed in the magnitude of change among caseloads. Effect sizes for therapist impact on outcome measures ranged from 0% to 18%. Despite impressive attempts to experi- mentally render individual practitioners as controlled variables, it is simply not possible to mask the person and the contribution of the therapist.

Even when treatments are effectively delivered with minimal therapist contact (King, Orr, Poulsen, Giacomantonio, & Haden, 2017), their relational context includes interpersonal skill, persua- sion, warmth, and even, on occasion, charisma. Self-help resources typically contain their developers’ self-disclosures, interpersonal support, and normalizing concerns. Thus, it is not surprising that the relation between treatment outcome and the therapeutic alli- ance in Internet-based psychotherapy is of the same strength as that for the alliance–outcome association in face-to-face psycho- therapy (Flückiger, Del Re, Wampold, & Horvath, 2018). Thera- pist effects are strong, ubiquitous, and sadly ignored in most guidelines on what works.

Therapeutic Relationship

A second omission in most treatment guidelines has been the decision to validate only the efficacy of treatment methods or technical interventions, as opposed to the therapy relationship or therapist interpersonal skills. This decision both reflects and rein- forces the ongoing movement toward high-quality, comparative effectiveness research on brand-name psychotherapies. “This trend of putting all of the eggs in the ‘technique’ basket began in the late 1970s and is now reaching the peak of influence” (Bergin, 1997, p. 83).

Both clinical experience and research findings underscore that the therapy relationship accounts for as much, and probably more,

of the outcome variance as particular treatment methods. Meta- analyses of psychotherapy outcome literature consistently reveal that specific treatment methods account for 0%–10% of the out- come variance (Lambert, 2013; Wampold & Imel, 2015), and much of that is attributable to the investigator’s therapy allegiance (Cuijpers et al., 2012; Luborsky et al., 1999).

Even those practice guidelines enjoining practitioners to attend to the therapy relationship do not provide specific, evidence-based means of doing so. For example, the scholarly and comprehensive review on treatment choice from Great Britain (Department of Health, 2001) devotes a single paragraph to the therapeutic rela- tionship. Its recommended principle is that “Effectiveness of all types of therapy depends on the patient and the therapist forming a good working relationship” (p. 35), but no evidence-based guid- ance is offered on which therapist behaviors contribute to or cultivate that relationship.

All of this is to say that treatment guidelines give short shrift— some would say lip service—to the person of the therapist and the emergent therapeutic relationship. The vast majority of current attempts are thus seriously incomplete and potentially misleading, both on clinical and empirical grounds.

Limitations of the Work

A single task force can accomplish only so much work and cover only so much content. As such, we wish to acknowledge publicly several necessary omissions and unfortunate truncations in our work.

The products of the third Task Force probably suffer first from content overlap. We may have cut the “diamond” of the therapy relationship too thin at times, leading to a profusion of highly related and possibly redundant constructs. Goal consensus, for example, correlates highly with collaboration, which is considered in the same article, and both of those are considered parts of the therapeutic alliance. Collecting client feedback and repairing alli- ance ruptures, for another example, may represent different sides of the same therapist behavior, but these too are covered in separate meta-analyses. Thus, to some the content may appear swollen; to others, the Task Force may have failed to make necessary distinctions.

Another lacuna in the Task Force work is that we may have neglected, relatively speaking, the productive contribution of the client to the therapy relationship. Virtually all of the relationship elements in this issue represent mutual processes of shared com- municative attunement (Orlinsky, Ronnestad, & Willutzki, 2004). They exist in the human connection, in the transactional process, rather than solely as a therapist (or client) variable. We encouraged authors to attend to the chain of events among the therapist’s contributions, the patient processes, and eventual treatment out- comes. Nevertheless, this limitation proves especially ironic in that the moderator analyses of several meta-analyses in this special issue indicated the patient’s perspective of the relationship proves more predictive of their treatment outcome than the therapist’s.

As with the previous two task forces, the overwhelming major- ity of research studies meta-analyzed were conducted in Western developed nations and published in English-language journals. The literature searches are definitely improving in accessing studies conducted internationally, but most authors did not translate arti- cles published in other languages. An encouraging exception were

the authors of the alliance meta-analysis (this issue), who included studies published in English, Italian, German, and French lan- guages.

Researcher allegiance may have also posed a problem in con- ducting and interpreting the meta-analyses. Of course, we invited authors with an interest and expertise in a relationship element, but in some cases, the authors might have experienced conflicts of interest due to their emotional, academic, or financial interests. The use of objective meta-analytic guidelines, peer review, and transparent data reporting may have attenuated the effects of their allegiance, but it remains a strong human propensity in any disci- pline.

Another prominent limitation across these research reviews is the difficulty of establishing causal connections between the rela- tionship behavior and treatment outcome. The only meta-analyses that contain randomized clinical trials (RCTs) capable of demon- strating a causal effect are collecting client feedback and repairing appliance ruptures. With these two exceptions, all of the meta- analyses in this issue reported the association and prediction of the relationship element to psychotherapy outcome. These were over- whelmingly correlational designs. It is methodologically difficult to meet the three conditions needed to make a causal claim: nonspuriousness, covariation between the process variable and the outcome measure, and temporal precedence of the process variable (Feeley, DeRubeis, & Gelfand, 1999). We still need to determine when the therapeutic relationship is a mediator, moderator, or mechanism of change in psychotherapy (Kazdin, 2007).

There is much confusion between relational factors related to outcome and those are characteristics or actions of effective ther- apists. Consider the example of empathy. There are dozens of studies and several meta-analyses now that indicate that empathy, as expressed or perceived in a session, is reliably related to psychotherapy outcome; that is called a total correlation. We do not know if that correlation is due to the patient (verbal and cooperative patients elicit empathy from their therapist and also get better) or the therapist (some therapists are generally more empathic than others, across patients, and these therapists achieve better outcomes).

Of all the relationship behaviors reviewed in this journal issue, only two (feedback and alliance ruptures) have addressed this disaggregation by means of RCTs and only one (alliance in indi- vidual therapy; Del Re, Flückiger, Horvath, Symonds, & Wampold, 2012) by other statistical means. And it turns out, the evidence is strong that it is the therapist who is important— therapists who generally form stronger alliances generally have better outcomes, but not vice versa (Del Re et al., 2012). It is largely the therapist’s contribution, not the patient’s contribution, that relates to therapy outcome (Baldwin, Wampold, & Imel, 2007; Wampold & Imel, 2015). Unfortunately, we do not know if this is true of empathy or most of the other relational elements.

At the same time as we acknowledge this limitation, let us remain mindful of several considerations about causation. First, in showing that these facets of a therapy relationship precede positive treatment outcome, we can certainly state that the relationship is, at a minimum, an important predictor and antecedent of that outcome. Second, dozens of lagged correlational, unconfounded regression, structural equation, and growth curve studies suggest that the therapy relationship probably casually contributes to out- come (Barber, Connolly, Crits-Christoph, Gladis, & Siqueland,

2000; Klein et al., 2003; alliance article, this issue). Third, some of the most precious behaviors in life are incapable on ethical grounds of random assignment and experimental manipulation. Take parental love as an exemplar. Not a single RCT has ever been conducted to conclusively determine the causal benefit of parents’ love on their children’s functioning, yet virtually all humans aspire to it and practice it. Nor can we envision an institutional review board ever approving a grant proposal to randomize patients in a psychotherapy study to an empathic, collaborative, and supportive therapist versus a nonempathic, authoritarian, and unsupportive therapist. We warn against an either/or conclusion on the ability of the therapy relationship to cause patient improvement.

A final interesting drawback to the present work involves the paucity of attention paid to the disorder-specific and treatment- specific nature of the therapy relationship. It is premature to aggregate the research on how the patient’s primary disorder or the type of treatment impacts the therapy relationship, but there are early links. For example, in the treatment of severe anxiety disor- ders (generalized anxiety disorder and obsessive–compulsive dis- order) and substance abuse, the relationship may well exert less impact (Flückiger et al., 2012; Graves et al., 2017) than in other disorders, such as depression. The therapeutic alliance in the National Institute of Mental Health Treatment of Depression Col- laborative Research Program, in both psychotherapy and pharma- cotherapy, emerged as the leading force in reducing a patient’s depression (Krupnick et al., 1996). The therapeutic relationship probably exhibits more impact in some disorders and in some therapies than others (Beckner, Vella, Howard, & Mohr, 2007; Bedics, Atkins, Harned, & Linehan, 2015). As with research on specific psychotherapies, it may no longer suffice to ask, “Does the relationship work?” but “How does the relationship work for this disorder and this treatment method?”

Conclusions of the Task Force on Evidence-Based Relationships and Responsiveness

The psychotherapy relationship makes substantial and con- sistent contributions to patient outcome independent of the specific type of psychological treatment.

The therapy relationship accounts for client improvement (or lack of improvement) as much as, and probably more than, the particular treatment method.

Practice and treatment guidelines should explicitly address therapist behaviors and qualities that promote a facilitative therapy relationship.

Efforts to promulgate best practices and evidence-based treat- ments without including the relationship and responsiveness are seriously incomplete and potentially misleading.

Adapting or tailoring the therapy relationship to specific patient characteristics (in addition to diagnosis) enhances the effectiveness of psychological treatment.

Adapting psychological treatment (or responsiveness) to transdiagnostic client characteristics contributes to successful outcomes at least as much as, and probably more than, adapt- ing treatment to the client’s diagnosis.

The therapy relationship acts in concert with treatment meth- ods, patient characteristics, and other practitioner qualities in determining effectiveness; a comprehensive understanding of effective (and ineffective) psychotherapy will consider all of these determinants and how they work together to produce benefit.

Table 2 summarizes the Task Force conclusions regarding the evidentiary strength of (a) elements of the therapy relation- ship primarily provided by the psychotherapist and (b) meth- ods of adapting psychotherapy to patient transdiagnostic char- acteristics.

The preceding conclusions do not constitute practice or treat- ment standards but represent current scientific knowledge to be understood and applied in the context of the clinical evidence available in each case.

Recommendations of the Task Force on Evidence- Based Relationships and Responsiveness

General Recommendations

- We recommend that the results and conclusions of this third Task Force be widely disseminated to enhance awareness and use of what “works” in the psychotherapy relationship and treatment adaptations.

- Readers are encouraged to interpret these findings in the context of the acknowledged limitations of the Task Force’s work.

- We recommend that future task forces be established periodically to review these findings, include new ele- ments of the relationship and responsiveness, incorporateTable 2

the results of non-English language publications (where practical), and update these conclusions.

Practice Recommendations

4. Practitioners are encouraged to make the creation and cultivation of the therapy relationship a primary aim of treatment. This is especially true for relationship ele- ments found to be demonstrably and probably effective.

5. Practitioners are encouraged to assess relational behav- iors (e.g., alliance, empathy, and cohesion) vis-a`-vis cut- off scores on popular clinical measures in ways that lead to more positive outcomes.

6. Practitioners are encouraged to adapt or tailor psycho- therapy to those specific client transdiagnostic character- istics in ways found to be demonstrably and probably effective.

7. Practitioners will experience increased treatment suc- cess by regularly assessing and responsively attuning psychotherapy to clients’ cultural identities (broadly defined).

8. Practitioners are encouraged to routinely monitor pa- tients’ satisfaction with the therapy relationship, comfort with responsiveness efforts, and response to treatment. Such monitoring leads to increased opportunities to re- establish collaboration, improve the relationship, modify technical strategies, and investigate factors external to therapy that may be hindering its effects.

9. Practitioners are encouraged to concurrently use evidence- based relationships and evidence-based treatments adapted

Task Force Conclusions Regarding the Evidentiary Strength of Elements of the Therapy Relationship and Methods of Adapting Psychotherapy

Evidentiary strength Demonstrably effective

Probably effective

Promising but insufficient research Important but not yet investigated

Elements of the relationship

Alliance in individual psychotherapy Alliance in child and adolescent psychotherapy Alliances in couple and family therapy Collaboration Goal consensus Cohesion in group therapy Empathy Positive regard and affirmation Collecting and delivering client feedback Congruence/genuineness Real relationship Emotional expression Cultivating positive expectations Promoting treatment credibility Managing countertransference Repairing alliance ruptures Self-disclosure and immediacy

Methods of adapting

Culture (race/ethnicity) Religion/spirituality Patient preferences

Reactance level Stages of change Coping style

Attachment style

Sexual orientation Gender identity

to the whole patient, as that is likely to generate the best outcomes in psychotherapy.

Training Recommendations

- Mental health training and continuing education pro- grams are encouraged to provide competency-based training in the demonstrably and probably effective elements of the therapy relationship.

- Mental health training and continuing education pro- grams are encouraged to provide competency-based training in adapting psychotherapy to the individual patient in ways that demonstrably and probably enhance treatment success.

- Psychotherapy educators and supervisors are encour- aged to train students in assessing and honoring clients’ cultural heritages, values, and beliefs in ways that en- hance the therapeutic relationship and inform treatment adaptations.

- Accreditation and certification bodies for mental health training programs are encouraged to develop criteria for assessing the adequacy of training in evidence-based therapy relationships and responsiveness.

Research Recommendations

- Researchers are encouraged to conduct research on the effectiveness of therapist relationship behaviors that do not presently have sufficient research evidence, such as self-disclosure, humility, flexibility, and deliberate practice.

- Researchers are encouraged to investigate further the effectiveness of adaptation methods in psychotherapy, such as to clients’ sexual orientation, gender identity, and attachment style, that do not presently have suffi- cient research evidence.

- Researchers are encouraged to proactively conduct re- lationship and responsiveness outcome studies with cul- turally diverse and historically marginalized clients.

- Researchers are encouraged to assess the relationship components using in-session observations in addition to postsession measures. The former track the client’s moment-to-moment experience of a session and the latter summarize the patient’s total experience of psy- chotherapy.

- Researchers are encouraged to progress beyond corre- lational designs that associate the frequency and quality of relationship behaviors with client outcomes to meth- odologies capable of examining the complex causal associations among client qualities, clinician behaviors, and psychotherapy outcomes.

- Researchers are encouraged to examine systematically the associations among the multitude of relationship

elements and adaptation methods to establish a more coherent and empirically based typology that will im- prove clinical training and practice.

20. Researchers are encouraged to disentangle the patient contributions and the therapist contributions to relation- ship elements and ultimately outcome.

21. Researchers are encouraged to examine the specific moderators between relationship elements and treat- ment outcomes.

22. Researchers are encouraged to address the observational perspective (i.e., therapist, patient, or external rater) in future studies and reviews of “what works” in the ther- apy relationship. Agreement among observational per- spectives provides a solid sense of established fact; divergence among perspectives holds important impli- cations for practice.

23. Researchers are encouraged to increase translational research and dissemination on those relational behaviors and treatment adaptations that already have been judged effective.

24. Researchers are encouraged to examine the effective- ness of educational, training, and supervision methods used to teach relational skills and treatment adaptations/ responsiveness.

Policy Recommendations

25. APA’s Society for the Advancement of Psychotherapy, the APA Society for Counseling Psychology, and all divisions are encouraged to educate their members on the benefits of evidence-based therapy relationships and responsiveness.

26. Mental health organizations as a whole are encouraged to educate their members about the improved out- comes associated with higher levels of therapist-offered evidence-based therapy relationships, as they frequently now do about evidence-based treatments.

27. We recommend that the APA and other mental health organizations advocate for the research-substantiated benefits of a nurturing and responsive human relation- ship in psychotherapy.

28. Finally, administrators of mental health services are encouraged to attend to and invest in the relational features and transdiagnostic adaptations of their ser- vices. Attempts to improve the quality of care should account for relationships and responsiveness, not only the implementation of evidence-based treatments for specific disorders.

Table 3 summarizes the meta-analytic associations between the relationship elements and psychotherapy outcomes. As seen there,

Summary of Meta-Analytic Associations Between Relationship Components and Psychotherapy Outcomes

Relationship element

Alliance in individual psychotherapy Alliance in child and adolescent therapy Alliances in couple and family therapy Collaboration

Goal consensus Cohesion in group therapy Empathy Positive regard and affirmation Congruence/genuineness The real relationship Self-disclosure and immediacy Emotional expression Cultivating positive expectation Promoting treatment credibility Managing countertransference Repairing alliance ruptures Collecting and delivering client feedback

Number of studies (k) 306

Number of patients (N) 30,000?

3,447 4,113 5,286 7,278 6,055 6,138 3,528 1,192 1,502 ?140

925 12,722 1,504

392 therapists 1,318 10,921

Effect size d or g

Note. NA ? not applicable; the chapter used qualitative a The effect sizes depended on the comparison group and the feedback method; feedback proved more effective with patients at risk for deterioration and less effective for all patients.

the expert consensus deemed nine of the relationship elements as demonstrably effective, seven as probably effective, and one as promising but insufficient research to judge. We were heartened to find the evidence base for all research elements had increased, and in some cases substantially, from the second edition (Norcross, 2011). We were also impressed by the disparate and perhaps elevated standards against which these relationship elements were evaluated.

Compare the evidentiary strength required for psychological treatments to be considered demonstrably efficacious in two influ- ential compilations of evidence-based practices. The Division of Clinical Psychology’s Subcommittee on Research-Supported Treatments (www.div12.org/PsychologicalTreatments/index.html) requires two between-groups design experiments demonstrating that a psychological treatment is either (a) statistically superior to pill or psychological placebo or to another treatment or (b) equiv- alent to an already established treatment in experiments with adequate sample sizes. The studies must have been conducted with treatment manuals and conducted by at least two different inves- tigators. The typical effect size of those studies was often smaller than the effects for the relationship elements reported in this series of articles. For listing in SAMHSA’s National Registry of Evidence-Based Programs and Practices (www.nrepp.samhsa .gov), which will be soon discontinued, only evidence of statisti- cally significant behavioral outcomes demonstrated in at least one study, using an experimental or quasi-experimental design, that has been published in a peer-reviewed journal or comprehensive evaluation report is needed. By these standards, practically all of the relationship elements in this journal issue would be considered demonstrably effective, if not for the requirement of an RCT, which proves neither clinically nor ethically feasible for most of the relationship elements.

In several ways, the effectiveness criteria for relationship ele- ments are more rigorous. Whereas the criteria for designating

treatments as evidence-based rely on only one or two studies, the evidence for relationship elements presented here is based on comprehensive meta-analyses of many studies (in excess of 40 studies in the majority of meta-analyses), spanning various treat- ments, a wide variety of treatment settings, patient populations, treatment formats, and research groups. The studies used to estab- lish evidence-based treatments are, however, RCTs. RCTs are often plagued by confounds, such as researcher allegiance, cannot be blinded, and often contain bogus comparisons (Luborsky et al., 1999; Mohr et al., 2009; Wampold, Baldwin, Holtforth, & Imel, 2017; Wampold et al., 2010). The point here is not to denigrate the criteria used to establish evidence-based treatments, but to under- score the robust scientific standards by which these relationship elements have been operationalized and evaluated. The evolving standards to judge evidence-based treatment methods are now moving away from the presence of an absolute number of studies to the presence of meta-analytic evidence (Tolin, McKay, Forman, Klonsky, & Thombs, 2015), a standard demonstrated repeatedly in this journal issue.

Consider as well the strength or magnitude of the therapy relationship. Across thousands of individual outcome studies and hundreds of meta-analytic reviews, the typical effect size differ- ence (d) between psychotherapy and no psychotherapy averages .80–.85 (Lambert, 2010; Wampold & Imel, 2015), a large effect size. The effect size (d) for any single relationship behavior in Table 3 ranges between .24 and .80. The alliance in individual psychotherapy, for example, demonstrates an aggregate r of .28 and a d of .57 with treatment outcome, making the quality of the alliance one of the strongest and most robust predictors of suc- cessful psychotherapy. These relationship behaviors are robustly effective components and predictors of patient success. We need to proclaim publicly what decades of research have discovered and what hundreds of thousands of practitioners have witnessed: The relationship can heal.

meta-analysis, which does not produce

effect sizes.

.28 .20 .30 .29 .24 .26 .28

.23 .37 NA .40 .18 .12 .39 .30

.57 .40 .62 .61 .49 .56 .58 .28 .46 .80 NA .85 .36 .24 .84 .62 .14–.49a

Consensus on evidentiary strength

Demonstrably effective Demonstrably effective Demonstrably effective Demonstrably effective Demonstrably effective Demonstrably effective Demonstrably effective Demonstrably effective Probably effective Probably effective Promising but insufficient research Probably effective

Probably effective Probably effective Probably effective Probably effective Demonstrably effective

It would probably prove advantageous to both practice and science to sum the individual effect sizes in Table 3 to arrive at a total of relationship contribution to treatment outcome, but reality is not so accommodating. Neither the research studies nor the relationship elements contained in the meta-analyses are indepen- dent; thus, the amount of variance accounted for by each element or construct cannot be added to estimate the overall contribution. For example, the correlations among the person-centered condi- tions (empathy, warmth/support, and congruence/genuineness) and the therapeutic alliance are typically in the .50s (Nienhuis et al., 2018; Watson & Geller, 2005). Many of the studies within the adult alliance meta-analysis also appear in the meta-analyses on collaboration and goal consensus, perhaps because a therapeutic alliance measure, subscale, or item was used to operationalize collaboration. Unfortunately, the degree of overlap between all the measures (and therefore relationship elements) is not available but bound to be substantial (Norcross & Lambert, 2014). Whether each relationship element is accounting for the same outcome variance or whether some of the elements are additive remains to be determined.

We present the relationship elements in this journal issue as separate, stand-alone practices, but every seasoned psychotherapist knows this is certainly never the case in clinical work. The alliance in individual therapy and cohesion in group therapy never act in isolation from other relationship behaviors, such as empathy or support. Nor does it seem humanly possible to cultivate a strong relationship with a patient without ascertaining her feedback on the therapeutic process and understanding the therapist’s countertrans- ference. All the relationship elements interconnect as we try to tailor therapy to the unique, complex individual. While these relationship elements “work,” they work together and interdepen- dently.

In any case, the meta-analytic results in this book probably underestimate the true effect due to the responsiveness problem (Kramer & Stiles, 2015; Stiles, Honos-Webb, & Surko, 1998). It is a problem for researchers but a boon to practitioners, who flexibly adjust the amount and timing of relational behaviors in psycho- therapy to fit the unique individual and singular context. Effective psychotherapists responsively provide varying levels of relation- ship elements in different cases and, within the same case, at different moments. This responsiveness tends to confound at- tempts to find naturalistically observed linear relations of outcome with therapist behaviors (e.g., cohesion and positive regard). As a consequence, the statistical relation between therapy relationship and outcome cannot always be trusted and tends to be lower than it actually is. By being clinically attuned and flexible, psychother- apists ironically make it more difficult in research studies to discern what works.

The profusion of research-supported relationship elements proves, at once, encouraging and disconcerting. Encouraging be- cause we have identified and measured potent predictors and contributions of the therapist that can be taught and implemented. Disconcerting because of the large number of potent relational behaviors that are highly intercorrelated and are without much organization or rationale.

Several researchers have clamored for a more coherent organi- zation of relationship behaviors that could guide practice and training. One proposal would arrange the relational elements in a conceptual hierarchy of helping relationships (Horvath, Symonds,

Flückiger, Del Re, & Lee, 2016). Superordinate, high-level De- scriptive Constructs describe the way of therapy. Featured here are the alliance, cohesion, and empathy as global ways of being in therapy. Below that are Strategies for managing the relationship, such as positive regard, self-disclosure, managing emotional ex- pression, promoting credibility, collecting formal feedback, and resolving ruptures. Then there are Therapist Qualities—more about the person than a strategy or skill. Exemplars are flexibility, congruence, and reactivity in responding to countertransference. The Strategies and the Therapist Qualities overlap of course, for example, in the personal quality of reactivity in responding to countertransference and in the Strategy of managing countertrans- ference. Finally, on the bottom of the hierarchy, come Client Contributions. These describe the client’s attachment style, pref- erences, expectations, coping styles, culture, reactance level, and diagnosis (all these may serve as reliable markers to adapt therapy and are featured in Volume 2 of Psychotherapy Relationships That Work; Norcross & Wampold, 2019). Horvath and colleagues’ (2016) four-level structure of the helping relationship provides greater organization and perhaps clarity.

That organization will assuredly benefit from multivariate meta- analyses conducted on several relationship constructs simultane- ously. However, too few studies exist to allow meta-analytic reviews of multiple relationship elements (e.g., measures of the therapeutic alliance, therapist empathy, and client expectations for improvement). Future multivariate meta-analyses could elevate the expectations for future scholarship, as most of these relationship variables share substantial variance and could inform conceptual schemes on their interrelations.

As the evidence base of therapist relationship behaviors devel- ops, we will know more about their effectiveness for particular circumstances and conditions. A case in point is the meta-analysis on collecting and delivering client feedback (Lambert, 2018). The evidence is quite clear that adding formal feedback helps clinicians effectively treat patients at risk for deterioration (d ? .49), whereas it is not needed in cases that are progressing well (see Table 3). How well, then, does relationship feedback work in psychother- apy? It depends; it depends on the purpose and the circumstances.

The strength of the therapy relationship also depends in some instances on the client’s principal disorder. The meta-analyses occasionally find some relationship elements less efficacious with some disorders, usually substance abuse, severe anxiety, and eat- ing disorders. Most moderator analyses usually find the relation- ship equally effective across disorders, but that conclusion may be due to the relatively small number of studies for any single disorder and the resulting low statistical power to find actual differences. And, of course, it gets more complicated as patients typically present with multiple, comorbid disorders.

Our point is that each context and patient needs something different. “We are differently organized,” as Lord Byron wrote. Empathy is demonstrably effective in psychotherapy, but suspi- cious patients respond negatively to classic displays of empathy, requiring therapist responsiveness and idiosyncratic expressions of empathy. The need to adapt or personalize therapy to the individ- ual patient is covered in detail in the other half of the Task Force’s work on evidence-based responsiveness (Norcross & Wampold, 2019).

What Does Not Work

Translational research is both prescriptive and proscriptive; it tells us what proves effective and what does not. We can optimize therapy relationships by simultaneously using what works and studiously avoiding what does not work. Here, we briefly highlight those therapist relational behaviors that are ineffective, perhaps even hurtful, in psychotherapy.

One means of identifying ineffective qualities of the therapeutic relationship is to reverse the effective behaviors identified in these meta-analyses. Thus, what does not work are poor alliances in adult, adolescent, child, couple, and family psychotherapy, as well as low levels of cohesion in group therapy. Paucity of collabora- tion, consensus, empathy, and positive regard predict treatment drop out and failure. The ineffective practitioner will not seek or be receptive to formal methods of providing client feedback on prog- ress and relationship, will ignore alliance ruptures, and will not be aware of his or her countertransference. Incongruent therapists, discreditable treatments, and emotional-less sessions detract from patient success.

Another means of identifying ineffective qualities of the rela- tionship is to scour the research literature (Duncan, Miller, Wampold, & Hubble, 2010; Lambert, 2010) and conduct polls of experts (Koocher, McMann, Stout, & Norcross, 2015; Norcross, Koocher, & Garofalo, 2006). In a previous review of that literature in 2011 (Norcross & Wampold, 2011), we recommended that practitioners avoid several behaviors: Confrontations, negative processes, assumptions, therapist–centricity, and rigidity. To that list we add cultural arrogance. Psychotherapy is inescapably bound to the cultures in which it is practiced by clinicians and experienced by clients. Arrogant impositions of therapists’ cultural beliefs in terms of gender, race/ethnicity, sexual orientation, and other intersecting dimensions of identity are culturally insensitive and demonstrably less effective (Soto, Smith, Griner, Rodriguez, & Bernal, 2019). By contrast, therapists expressing cultural hu- mility and tracking clients’ satisfaction with cultural responsive- ness markedly improve client engagement, retention, and eventual treatment outcome.

Concluding Reflections

The future of psychotherapy portends the integration of the instrumental and the interpersonal, of the technical and the rela- tional in the tradition of evidence-based practice (Norcross, Freed- heim, & VandenBos, 2011). Evidence-based psychotherapy rela- tionships align with this future and embody a crucial part of evidence-based practice, when properly conceptualized. We can imagine few practices in all of psychotherapy that can confidently boast that they integrate as well “the best available research with clinical expertise in the context of patient characteristics, culture, and preferences” (APA Presidential Task Force on Evidence- Based Practice, 2006) as the relational behaviors in this special issue. We are reminded daily that research can guide how to create, cultivate, and customize that powerful human relationship.

Of course, that research knowledge serves little practical pur- pose if psychotherapists do not know it and if they do not enact the specific behaviors to enhance these relationship elements. The meta-analyses are complete now, but not the tasks of dissemination and implementation. Members of the Task Force Steering Com- mittee plan to share these results widely in journal articles, public

presentations, training workshops, and professional websites. A Society for the Advancement of Psychotherapy initiative, Teach- ing and Learning Evidence-Based Relationships: Interviews with the Experts (societyforpsychotherapy.org/teaching-learning- evidence-based-relationships), is underway to assist students and educators in these evidence-based therapy relationships.

The three interdivisional APA task forces originated to augment patient benefit. We continue to explore what works in the therapy relationship (and what works when we adapt that relationship to transdiagnostic patient characteristics). That remains our goal: improving patient outcomes, however measured and manifested in a given case. A dispassionate analysis of the avalanche of meta- analyses in this journal issue reveals that multiple relationship behaviors positively associate with, temporally predict, and per- haps causally contribute to client outcomes. This is reassuring news in a technology-driven and drug-filled world (Greenberg, 2016).

To repeat one of the Task Force’s conclusions: The psychother- apy relationship makes substantial and consistent contributions to outcome independent of the type of treatment. Decades of research evidence and clinical experience converge: The relationship works! These effect sizes concretely translate into healthier and happier people.

APA Presidential Task Force on Evidence-Based Practice. (2006). Evidence-based practice in psychology. American Psychologist, 61, 271–285. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.61.4.271

Baldwin, S. A., Wampold, B. E., & Imel, Z. E. (2007). Untangling the alliance-outcome correlation: Exploring the relative importance of ther- apist and patient variability in the alliance. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 75, 842– 852. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X .75.6.842

Barber, J. P., Connolly, M. B., Crits-Christoph, P., Gladis, L., & Siqueland, L. (2000). Alliance predicts patients’ outcomes beyond in-treatment change in symptoms. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 68, 1027–1032.

Barkham, M., Lutz, W., Lambert, M. J., & Saxon, D. (2017). Therapist effects, effective therapists, and the law of variability. In L. Castonguay & C. Hill (Eds.), How and why are some therapists better than others? Understanding therapist effects (pp. 13–36). Washington, DC: Ameri- can Psychological Press. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0000034-002

Barlow, D. H. (2000). Evidence-based practice: A world view. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 7, 241–242. http://dx.doi.org/10 .1093/clipsy.7.3.241

Beckner, V., Vella, L., Howard, I., & Mohr, D. C. (2007). Alliance in two telephone-administered treatments: Relationship with depression and health outcomes. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 75, 508–512. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.75.3.508

Bedics, J. D., Atkins, D. C., Harned, M. S., & Linehan, M. M. (2015). The therapeutic alliance as a predictor of outcome in dialectical behavior therapy versus nonbehavioral psychotherapy by experts for borderline personality disorder. Psychotherapy, 52, 67–77. http://dx.doi.org/10 .1037/a0038457

Bergin, A. E. (1997). Neglect of the therapist and the human dimensions of change: A commentary. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 4, 83–89. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2850.1997.tb00102.x

Castonguay, L., & Hill, C. E. (Eds.). (2017). How and why are some therapists better than others? Understanding therapist effects. Washing- ton, DC: American Psychological Association. http://dx.doi.org/10 .1037/0000034-000

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Crits-Christoph, P., Baranackie, K., Kurcias, J. S., Beck, A. T., Carroll, K., Perry, K., . . . Zitrin, C. (1991). Meta-analysis of therapist effects in psychotherapy outcome studies. Psychotherapy Research, 1, 281–291. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10503309112331335511

Cuijpers, P., Driessen, E., Hollon, S. D., van Oppen, P., Barth, J., & Andersson, G. (2012). The efficacy of non-directive supportive therapy for adult depression: A meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 32, 280–291. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2012.01.003

Del Re, A. C., Flückiger, C., Horvath, A. O., Symonds, D., & Wampold, B. E. (2012). Therapist effects in the therapeutic alliance-outcome rela- tionship: A restricted-maximum likelihood meta-analysis. Clinical Psy- chology Review, 32, 642–649. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2012.07 .002

Department of Health. (2001). Treatment choice in psychological therapies and counseling. London, United Kingdom: Department of Health Pub- lications.

Duncan, B. L., Miller, S. D., Wampold, B. E., & Hubble, M. A. (Eds.). (2010). Heart & soul of change in psychotherapy (2nd ed.). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Elliott, R., Bohart, A. C., Watson, J. C., & Murphy, D. (2018). Therapist empathy and client outcome: An updated meta-analysis. Psychotherapy, 55, 399–410. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/pst0000175

Feeley, M., DeRubeis, R. J., & Gelfand, L. A. (1999). The temporal relation of adherence and alliance to symptom change in cognitive therapy for depression. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 67, 578–582. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.67.4.578

Flückiger, C., Del Re, A. C., Wampold, B. E., & Horvath, A. O. (2018). The alliance in adult psychotherapy: A meta-analytic synthesis. Psycho- therapy, 55, 316–340. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/pst0000172

Flückiger, C., Del Re, A. C., Wampold, B. E., Symonds, D., & Horvath, A. O. (2012). How central is the alliance in psychotherapy? A multilevel longitudinal meta-analysis. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 59, 10– 17. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0025749

Gelso, C. J., & Carter, J. A. (1985). The relationship in counseling and psychotherapy: Components, consequences, and theoretical antecedents. The Counseling Psychologist, 13, 155–243. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/ 0011000085132001

Gelso, C. J., & Carter, J. A. (1994). Components of the psychotherapy relationship: Their inter-action and unfolding during treatment. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 41, 296–306. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/ 0022-0167.41.3.296

Gelso, C. J., & Hayes, J. A. (1998). The psychotherapy research: Theory, research, and practice. New York, NY: Wiley.

Graves, T. A., Tabri, N., Thompson-Brenner, H., Franko, D. L., Eddy, K. T., Bourion-Bedes, S., & Thomas, J. J. (2017). A meta-analysis of the relation between therapeutic alliance and treatment outcome in eating disorders. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 50, 323–340. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/eat.22672

Greenberg, R. P. (2016). The rebirth of psychosocial importance in a drug-filled world. American Psychologist, 71, 781–791. http://dx.doi .org/10.1037/amp0000054

Henry, W. P. (1998). Science, politics, and the politics of science: The use and misuse of empirically validated treatment research. Psycho- therapy Research, 8, 126 –140. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/ 10503309812331332267

Horvath, A. O., Symonds, D. B., Flückiger, C., Del Re, A. C., & Lee, E. (2016, June). Integration across professional domains: The helping relationship. Paper presented at the 32nd Annual Conference of the Society for the Exploration of Psychotherapy Integration, Dublin, Ire- land.

Hubble, M. A., Wampold, B. E., Duncan, B. L., & Miller, S. D. (Eds.). (2011). The heart and soul of change (2nd ed.). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Huppert, J. D., Bufka, L. F., Barlow, D. H., Gorman, J. M., Shear, M. K., & Woods, S. W. (2001). Therapists, therapist variables, and cognitive- behavioral therapy outcome in a multicenter trial for panic disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 69, 747–755. http://dx .doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.69.5.747

Kazdin, A. E. (2007). Mediators and mechanisms of change in psycho- therapy research. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 3, 1–27. http:// dx.doi.org/10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091432

King, R. J., Orr, J. A., Poulsen, B., Giacomantonio, S. G., & Haden, C. (2017). Understanding the therapist contribution to psychotherapy out- come: A meta-analytic approach. Administration and Policy in Mental Health, 44, 664–680. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10488-016-0783-9

Klein, D. N., Schwartz, J. E., Santiago, N. J., Vivian, D., Vocisano, C., Castonguay, L. G., . . . Keller, M. B. (2003). Therapeutic alliance in depression treatment: Controlling for prior change and patient charac- teristics. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 71, 997–1006. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.71.6.997

Koocher, G. P., McMann, M. R., Stout, A. O., & Norcross, J. C. (2015). Discredited assessment and treatment methods used with children and adolescents: A Delphi poll. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 44, 722–729. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2014 .895941

Kramer, U., & Stiles, W. B. (2015). The responsiveness problem in psychotherapy: A review of proposed solutions. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 22, 277–295. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/cpsp .12107

Krupnick, J. L., Sotsky, S. M., Simmens, S., Moyer, J., Elkin, I., Watkins, J., & Pilkonis, P. A. (1996). The role of the therapeutic alliance in psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy outcome: Findings in the National Institute of Mental Health Treatment of Depression Collaborative Re- search Program. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 64, 532–539. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.64.3.532

Lambert, M. J. (2010). Prevention of treatment failure: The use of mea- suring, monitoring, & feedback in clinical practice. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/12141- 000

Lambert, M. J. (2013). The efficacy and effectiveness of psychotherapy. In M. J. Lambert (Ed.), Bergin & Garfield’s handbook of psychotherapy and behavior change (6th ed., pp. 169–218). New York, NY: Wiley.

Lambert, M. J., Whipple, J. L., & Kleinstäuber, M. (2018). Collecting and delivering progress feedback: A meta-analysis of routine outcome mon- itoring. Psychotherapy, 55, 520 –537. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/ pst0000167

Luborsky, L., Diguer, L., Seligman, D. A., Rosenthal, R., Krause, E. D., Johnson, S., . . . Schweitzer, E. (1999). The researcher’s own therapy allegiances: A “wild card” in comparisons of treatment efficacy. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 6, 95–106. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/ clipsy/6.1.95

Messer, S. B. (2001). Empirically supported treatments: What’s a nonbe- haviorist to do? In B. D. Slife, R. N. Williams, & S. H. Barlow (Eds.), Critical issues in psychotherapy (pp. 3–20). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. http://dx.doi.org/10.4135/9781452229126.n1

Mohr, D. C., Spring, B., Freedland, K. E., Beckner, V., Arean, P., Hollon, S. D., . . . Kaplan, R. (2009). The selection and design of control conditions for randomized controlled trials of psychological interven- tions. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 78, 275–284. http://dx.doi .org/10.1159/000228248

Nathan, P. E., & Gorman, J. M. (Eds.). (2015). A guide to treatments that work (4th ed.). New York, NY: Oxford University Press. http://dx.doi .org/10.1093/med:psych/9780195304145.001.0001

Nienhuis, J. B., Owen, J., Valentine, J. C., Black, S. W., Halford, T. C., Parazak, S. E., . . . Hilsenroth, M. (2018). Therapeutic alliance, empathy, and genuineness in individual adult psychotherapy: A meta-analytic review. Psychotherapy Research, 28, 593– 605. http://dx.doi.org/10 .1080/10503307.2016.1204023

Norcross, J. C. (Ed.). (2002). Psychotherapy relationships that work: Therapist contributions and responsiveness to patient needs. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Norcross, J. C. (Ed.). (2011). Psychotherapy relationships that work (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Oxford University Press. http://dx.doi.org/10 .1093/acprof:oso/9780199737208.001.0001

Norcross, J. C., Freedheim, D. K., & VandenBos, G. R. (2011). Into the future: Retrospect and prospect in psychotherapy. In J. C. Norcross, G. R. Vanderbos, & D. K. Freedheim (Eds.), History of psychotherapy (2nd ed., pp. 743–760). Washington, DC: American Psychological As- sociation. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/12353-049

Norcross, J. C., Hogan, T. P., Koocher, G. P., & Maggio, L. A. (2017).

Clinician’s guide to evidence-based practices: Behavioral health and addictions (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Oxford University Press. http:// dx.doi.org/10.1093/med:psych/9780190621933.001.0001

Norcross, J. C., Koocher, G. P., & Garofalo, A. (2006). Discredited psychological treatments and tests: A Delphi poll. Professional Psychol- ogy, Research and Practice, 37, 515–522. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/ 0735-7028.37.5.515

Norcross, J. C., & Lambert, M. J. (2014). Relationship science and practice in psychotherapy: Closing commentary. Psychotherapy, 51, 398–403. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0037418

Norcross, J. C., & Lambert, M. J. (Eds.). (2019). Psychotherapy relationships that work (3rd ed., Vol. 1). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Norcross, J. C., & Wampold, B. E. (2011). What works for whom: Adapting psychotherapy to the person. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 67, 127–132.

Norcross, J. C., & Wampold, B. E. (Eds.). (2019). Psychotherapy relation- ships that work (3rd ed., Vol. 2). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Orlinsky, D. E., Ronnestad, M. H., & Willutzki, U. (2004). Fifty years of psychoteherapy process-outcome research: Continuity and change. In M. J. Lambert (Ed.), Bergin and Garfield’s Handbook of psychotherapy and behavior change (4th ed., pp. 307–390). New York, NY: Wiley.

Orlinsky, D., & Howard, K. E. (1977). The therapist’s experience of psycho-

therapy. In A. S. Gurman & A. M. Razin (Eds.), Effective psychotherapy:

A handbook of research. New York, NY: Pergamon Press. Safran, J. D., & Muran, J. C. (2000). Negotiating the therapeutic alliance.

New York, NY: Guilford Press. Smith, M. I., Glass, G. W. V., & Miller, T. L. (1980). The benefits of

psychotherapy. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press. Soto, A., Smith, T. B., Griner, D., Rodriguez, M. D., & Bernal, G. (2019). Cultural adaptations and multicultural competence. In J. C. Norcross & B. E. Wampold (Eds.), Psychotherapy relationships that work (Vol. 2).

New York, NY: Oxford University Press. Stiles, W. B., Honos-Webb, L., & Surko, M. (1998). Responsiveness in

psychotherapy. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 5, 439 – 458.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2850.1998.tb00166.x

Tasca, G. A., Sylvestre, J., Balfour, L., Chyurlia, L., Evans, J., Fortin- Langelier, B., . . . Wilson, B. (2015). What clinicians want: Findings from a psychotherapy practice research network survey. Psychotherapy, 52, 1–11. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0038252