13.1 What is an Informative Speech?

An informative speech can first be defined as a speech based entirely and exclusively on facts. Basically, an informative speech conveys knowledge, a task that every person engages in every day in some form or another. Whether giving someone who is lost driving directions, explaining the specials of the day as a server, or describing the plot of a movie to friends, people engage in forms of informative speaking daily. Secondly, an informative speech does not attempt to convince the audience that one thing is better than another. It does not advocate a course of action.

Consider the following two statements:

George Washington was the first President of the United States.

In each case, the statement made is what can be described as irrefutable, meaning a statement or claim that cannot be argued. In the first example, even small children are taught that having two apples and then getting two more apples will result in having four apples. This statement is irrefutable in that no one in the world will (or should!) argue this: It is a fact.

Similarly, with the statement “George Washington was the first President of the United States,” this again is an irrefutable fact. If you asked one hundred history professors and read one hundred history textbooks, the professors and textbooks would all say the same thing: Washington was the first president. No expert, reliable source, or person with any common sense would argue about this.

(Someone at this point might say, “No, John Hanson was the first president.” However, he was president under the Articles of Confederation for a short period—November 5, 1781, to November 3, 1782—not under our present Constitution. This example shows the importance of stating your facts clearly and precisely and being able to cite their origins.)

Informative Speech is Not a Persuasive Speech

Informative speech is fundamentally different from a persuasive speech in that it does not incorporate opinion as its basis. This can be the tricky part of developing an informative speech, because some opinion statements sometimes sound like facts (since they are generally agreed upon by many people), but are really opinion. For example, in an informative speech on George Washington, you might say, “George Washington was one of the greatest presidents in the history of the United States.” While this statement may be agreed upon by most people, it is possible for some people to disagree and argue the opposite point of view. The statement “George Washington was one of the greatest presidents in the history of the United States” is not irrefutable, meaning someone could argue this claim. If, however, you present the opinion as an opinion from a source, that is acceptable: it is a fact that someone (hopefully someone with expertise) holds the opinion. You do not want your central idea, your main points, and the majority of your supporting material to be opinion or argument in an informative speech.

Unlike in persuasive speeches, in an informative speech, you should never take sides on an issue, nor should you “spin” the issue in order to influence the opinions of the listeners. Even if you are informing the audience about differences in views on controversial topics, you should simply and clearly describe and explain the issues. This is not to say, however, that the audience’s needs and interests have nothing to do with the informative speech. We come back to the WIIFM principle (“What’s in it for me?”) because even though an informative speech is fact-based, it still needs to relate to people’s lives in order to maintain their attention.

Why Informative Speech Is Important

The question may arise here, “If we can find anything on the Internet now, why bother to give an informative speech?” The answer lies in the unique relationship between audience and speaker found in the public speaking context. The speaker can choose to present information that is of most value to the audience. Secondly, the speaker is not just overloading the audience with data. As we have mentioned before, that’s not really a good idea because audiences cannot remember great amounts of data and facts after listening. The focus of the content is what matters. This is where the specific purpose and central idea come into play. Remember, public speaking is not a good way to “dump data” on the audience, but to make information meaningful.

Finally, although we have stressed that the informative speech is fact-based and does not have the purpose of persuasion, information still has an indirect effect on someone. If a classmate gives a speech on correctly using the Heimlich Maneuver to help a choking victim, the side effect (and probably desired result) is that the audience would use it when confronted with the situation.

It’s About Them: Public Speaking in the 21st Century Copyright © 2022 by LOUIS: The Louisiana Library Network is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Planning and Presenting an Informative Speech

In this guide, you can learn about the purposes and types of informative speeches, about writing and delivering informative speeches, and about the parts of informative speeches.

Purposes of Informative Speaking

Informative speaking offers you an opportunity to practice your researching, writing, organizing, and speaking skills. You will learn how to discover and present information clearly. If you take the time to thoroughly research and understand your topic, to create a clearly organized speech, and to practice an enthusiastic, dynamic style of delivery, you can be an effective "teacher" during your informative speech. Finally, you will get a chance to practice a type of speaking you will undoubtedly use later in your professional career.

The purpose of the informative speech is to provide interesting, useful, and unique information to your audience. By dedicating yourself to the goals of providing information and appealing to your audience, you can take a positive step toward succeeding in your efforts as an informative speaker.

Major Types of Informative Speeches

In this guide, we focus on informative speeches about:

These categories provide an effective method of organizing and evaluating informative speeches. Although they are not absolute, these categories provide a useful starting point for work on your speech.

In general, you will use four major types of informative speeches. While you can classify informative speeches many ways, the speech you deliver will fit into one of four major categories.

Speeches about Objects

Speeches about objects focus on things existing in the world. Objects include, among other things, people, places, animals, or products.

Because you are speaking under time constraints, you cannot discuss any topic in its entirety. Instead, limit your speech to a focused discussion of some aspect of your topic.

Some example topics for speeches about objects include: the Central Intelligence Agency, tombstones, surgical lasers, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, the pituitary gland, and lemmings.

To focus these topics, you could give a speech about Franklin Delano Roosevelt and efforts to conceal how he suffered from polio while he was in office. Or, a speech about tombstones could focus on the creation and original designs of grave markers.

Speeches about Processes

Speeches about processes focus on patterns of action. One type of speech about processes, the demonstration speech, teaches people "how-to" perform a process. More frequently, however, you will use process speeches to explain a process in broader terms. This way, the audience is more likely to understand the importance or the context of the process.

A speech about how milk is pasteurized would not teach the audience how to milk cows. Rather, this speech could help audience members understand the process by making explicit connections between patterns of action (the pasteurization process) and outcomes (a safe milk supply).

Other examples of speeches about processes include: how the Internet works (not "how to work the Internet"), how to construct a good informative speech, and how to research the job market. As with any speech, be sure to limit your discussion to information you can explain clearly and completely within time constraints.

Speeches about Events

Speeches about events focus on things that happened, are happening, or will happen. When speaking about an event, remember to relate the topic to your audience. A speech chronicling history is informative, but you should adapt the information to your audience and provide them with some way to use the information. As always, limit your focus to those aspects of an event that can be adequately discussed within the time limitations of your assignment.

Examples of speeches about events include: the 1963 Civil Rights March on Washington, Groundhog's Day, the Battle of the Bulge, the World Series, and the 2000 Presidential Elections.

Speeches about Concepts

Speeches about concepts focus on beliefs, ideas, and theories. While speeches about objects, processes, and events are fairly concrete, speeches about concepts are more abstract. Take care to be clear and understandable when creating and presenting a speech about a concept. When selecting a concept, remember you are crafting an informative speech. Often, speeches about concepts take on a persuasive tone. Focus your efforts toward providing unbiased information and refrain from making arguments. Because concepts can be vague and involved, limit your speech to aspects that can be readily explained and understood within the time limits.

Some examples of topics for concept speeches include: democracy, Taoism, principles of feminism, the philosophy of non-violent protest, and the Big Bang theory.

Strategies for Selecting a Topic

In many cases, circumstances will dictate the topic of your speech. However, if the topic has not been assigned or if you are having difficulty figuring out how to frame your topic as an informative speech,the following may be useful.

Begin by thinking of your interests. If you have always loved art, contemplate possible topics dealing with famous artists, art works, or different types of art. If you are employed, think of aspects of your job or aspects of your employer's business that would be interesting to talk about. While you cannot substitute personal experience for detailed research, your own experience can supplement your research and add vitality to your presentation. Choose one of the items below to learn more about selecting a topic.

Learn More about an Unfamiliar Topic

You may benefit more by selecting an unfamiliar topic that interests you. You can challenge yourself by choosing a topic you'd like to learn about and to help others understand it. If the Buddhist religion has always been an interesting and mysterious topic to you, research the topic and create a speech that offers an understandable introduction to the religion. Remember to adapt Buddhism to your audience and tell them why you think this information is useful to them. By taking this approach, you can learn something new and learn how to synthesize new information for your audience.

Think about Previous Classes

You might find a topic by thinking of classes you have taken. Think back to concepts covered in those classes and consider whether they would serve as unique, interesting, and enlightening topics for the informative speech. In astronomy, you learned about red giants. In history, you learned about Napoleon. In political science, you learned about The Federalist Papers. Past classes serve as rich resources for informative speech topics. If you make this choice, use your class notes and textbook as a starting point. To fully develop the content, you will need to do extensive research and perhaps even a few interviews.

Talk to Others

Topic selection does not have to be an individual effort. Spend time talking about potential topics with classmates or friends. This method can be extremely effective because other people can stimulate further ideas when you get stuck. When you use this method, always keep the basic requirements and the audience in mind. Just because you and your friend think home-brew is a great topic does not mean it will enthrall your audience or impress your instructor. While you talk with your classmates or friends, jot notes about potential topics and create a master list when you exhaust the possibilities. From this list, choose a topic with intellectual merit, originality, and potential to entertain while informing.

Framing a Thesis Statement

Once you settle on a topic, you need to frame a thesis statement. Framing a thesis statement allows you to narrow your topic, and in turns allows you to focus your research in this specific area, saving you time and trouble in the process.

Selecting a topic and focusing it into a thesis statement can be a difficult process. Fortunately, a number of useful strategies are available to you.

Thesis Statement Purpose

The thesis statement is crucial for clearly communicating your topic and purpose to the audience. Be sure to make the statement clear, concise, and easy to remember. Deliver it to the audience and use verbal and nonverbal illustrations to make it stand out.

Strategies For Framing a Thesis Statement

Focus on a specific aspect of your topic and phrase the thesis statement in one clear, concise, complete sentence, focusing on the audience. This sentence sets a goal for the speech. For example, in a speech about art, the thesis statement might be: "The purpose of this speech is to inform my audience about the early works of Vincent van Gogh." This statement establishes that the speech will inform the audience about the early works of one great artist. The thesis statement is worded conversationally and included in the delivery of the speech.

Thesis Statement and Audience

The thesis appears in the introduction of the speech so that the audience immediately realizes the speaker's topic and goal. Whatever the topic may be, you should attempt to create a clear, focused thesis statement that stands out and could be repeated by every member of your audience. It is important to refer to the audience in the thesis statement; when you look back at the thesis for direction, or when the audience hears the thesis, it should be clear that the most important goal of your speech is to inform the audience about your topic. While the focus and pressure will be on you as a speaker, you should always remember that the audience is the reason for presenting a public speech.

Avoid being too trivial or basic for the average audience member. At the same time, avoid being too technical for the average audience member. Be sure to use specific, concrete terms that clearly establish the focus of your speech.

Thesis Statement and Delivery

When creating the thesis statement, be sure to use a full sentence and frame that sentence as a statement, not as a question. The full sentence, "The purpose of this speech is to inform my audience about the early works of Vincent van Gogh," provides clear direction for the speech, whereas the fragment "van Gogh" says very little about the purpose of the speech. Similarly, the question "Who was Vincent van Gogh?" does not adequately indicate the direction the speech will take or what the speaker hopes to accomplish.

If you limit your thesis statement to one distinct aspect of the larger topic, you are more likely to be understood and to meet the time constraints.

Researching Your Topic

As you begin to work on your informative speech, you will find that you need to gather additional information. Your instructor will most likely require that you locate relevant materials in the library and cite those materials in your speech. In this section, we discuss the process of researching your topic and thesis.

Conducting research for a major informative speech can be a daunting task. In this section, we discuss a number of strategies and techniques that you can use to gather and organize source materials for your speech.

Gathering Materials

Gathering materials can be a daunting task. You may want to do some research before you choose a topic. Once you have a topic, you have many options for finding information. You can conduct interviews, write or call for information from a clearinghouse or public relations office, and consult books, magazines, journals, newspapers, television and radio programs, and government documents. The library will probably be your primary source of information. You can use many of the libraries databases or talk to a reference librarian to learn how to conduct efficient research.

Taking Notes

While doing your research, you may want to carry notecards. When you come across a useful passage, copy the source and the information onto the notecard or copy and paste the information. You should maintain a working bibliography as you research so you always know which sources you have consulted and so the process of writing citations into the speech and creating the bibliography will be easier. You'll need to determine what information-recording strategies work best for you. Talk to other students, instructors, and librarians to get tips on conducting efficient research. Spend time refining your system and you will soon be able to focus on the information instead of the record-keeping tasks.

Citing Sources Within Your Speech

Consult with your instructor to determine how much research/source information should be included in your speech. Realize that a source citation within your speech is defined as a reference to or quotation from material you have gathered during your research and an acknowledgement of the source. For example, within your speech you might say: "As John W. Bobbitt said in the December 22, 1993, edition of the Denver Post , 'Ouch!'" In this case, you have included a direct quotation and provided the source of the quotation. If you do not quote someone, you might say: "After the first week of the 1995 baseball season, attendance was down 13.5% from 1994. This statistic appeared in the May 7, 1995, edition of the Denver Post ." Whatever the case, whenever you use someone else's ideas, thoughts, or words, you must provide a source citation to give proper credit to the creator of the information. Failure to cite sources can be interpreted as plagiarism which is a serious offense. Upon review of the specific case, plagiarism can result in failure of the assignment, the course, or even dismissal from the University. Take care to cite your sources and give credit where it is due.

Creating Your Bibliography

As with all aspects of your speech, be sure to check with your instructor to get specific details about the assignment.

Generally, the bibliography includes only those sources you cited during the speech. Don't pad the bibliography with every source you read, saw on the shelf, or heard of from friends. When you create the bibliography, you should simply go through your complete sentence outline and list each source you cite. This is also a good way to check if you have included enough reference material within the speech. You will need to alphabetize the bibiography by authors last name and include the following information: author's name, article title, publication title, volume, date, page number(s). You may need to include additional information; you need to talk with your instructor to confirm the required bibliographical format.

Some Cautions

When doing research, use caution in choosing your sources. You need to determine which sources are more credible than others and attempt to use a wide variety of materials. The broader the scope of your research, the more impressive and believable your information. You should draw from different sources (e.g., a variety of magazines-- Time, Newsweek, US News & World Report, National Review, Mother Jones ) as well as different types of sources (i.e., use interviews, newspapers, periodicals, and books instead of just newspapers). The greater your variety, the more apparent your hard work and effort will be. Solid research skills result in increased credibility and effectiveness for the speaker.

Structuring an Informative Speech

Typically, informative speeches have three parts:

Introduction

In this section, we discuss the three parts of an informative speech, calling attention to specific elements that can enhance the effectiveness of your speech. As a speaker, you will want to create a clear structure for your speech. In this section, you will find discussions of the major parts of the informative speech.

The introduction sets the tone of the entire speech. The introduction should be brief and to-the-point as it accomplishes these several important tasks. Typically, there are six main components of an effective introduction:

Attention Getters

Thesis statement, audience adaptation, credibility statement, transition to the body.

As in any social situation, your audience makes strong assumptions about you during the first eight or ten seconds of your speech. For this reason, you need to start solidly and launch the topic clearly. Focus your efforts on completing these tasks and moving on to the real information (the body) of the speech. Typically, there are six main components of an effective introduction. These tasks do not have to be handled in this order, but this layout often yields the best results.

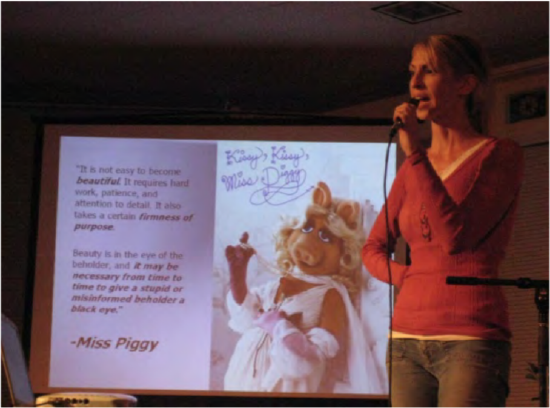

The attention-getter is designed to intrigue the audience members and to motivate them to listen attentively for the next several minutes. There are infinite possibilities for attention-getting devices. Some of the more common devices include using a story, a rhetorical question, or a quotation. While any of these devices can be effective, it is important for you to spend time strategizing, creating, and practicing the attention-getter.

Most importantly, an attention-getter should create curiosity in the minds of your listeners and convince them that the speech will be interesting and useful. The wording of your attention-getter should be refined and practiced. Be sure to consider the mood/tone of your speech; determine the appropriateness of humor, emotion, aggressiveness, etc. Not only should the words get the audiences attention, but your delivery should be smooth and confident to let the audience know that you are a skilled speaker who is prepared for this speech.

The crowd was wild. The music was booming. The sun was shining. The cash registers were ringing.

This story-like re-creation of the scene at a Farm Aid concert serves to engage the audience and causes them to think about the situation you are describing. Touching stories or stories that make audience members feel involved with the topic serve as good attention-getters. You should tell a story with feeling and deliver it directly to the audience instead of reading it off your notecards.

Example Text : One dark summer night in 1849, a young woman in her 20's left Bucktown, Maryland, and followed the North Star. What was her name? Harriet Tubman. She went back some 19 times to rescue her fellow slaves. And as James Blockson relates in a 1984 issue of National Geographic , by the end of her career, she had a $40,000.00 price on her head. This was quite a compliment from her enemies (Blockson 22).

Rhetorical Question

Rhetorical questions are questions designed to arouse curiosity without requiring an answer. Either the answer will be obvious, or if it isn't apparent, the question will arouse curiosity until the presentation provides the answer.

An example of a rhetorical question to gain the audiences attention for a speech about fly-fishing is, "Have you ever stood in a freezing river at 5 o'clock in the morning by choice?"

Example Text: Have you ever heard of a railroad with no tracks, with secret stations, and whose conductors were considered criminals?

A quotation from a famous person or from an expert on your topic can gain the attention of the audience. The use of a quotation immediately launches you into the speech and focuses the audience on your topic area. If it is from a well-known source, cite the author first. If the source is obscure, begin with the quote itself.

Example Text : "No day dawns for the slave, nor is it looked for. It is all night--night forever . . . ." (Pause) This quote was taken from Jermain Loguen, a fugitive who was the son of his Tennessee master and a slave woman.

Unusual Statement

Making a statement that is unusual to the ears of your listeners is another possibility for gaining their attention.

Example Text : "Follow the drinking gourd. That's what I said, friend, follow the drinking gourd." This phrase was used by slaves as a coded message to mean the Big Dipper, which revealed the North Star, and pointed toward freedom.

You might chose to use tasteful humor which relates to the topic as an effective way to attract the audience both to you and the subject at hand.

Example Text : "I'm feeling boxed in." [PAUSE] I'm not sure, but these may have been Henry "Box" Brown's very words after being placed on his head inside a box which measured 3 feet by 2 feet by 2 1\2 feet for what seemed to him like "an hour and a half." He was shipped by Adams Express to freedom in Philadelphia (Brown 60,92; Still 10).

Shocking Statistic

Another possibility to consider is the use of a factual statistic intended to grab your listener's attention. As you research the topic you've picked, keep your eyes open for statistics that will have impact.

Example Text : Today, John Elway's talents are worth millions, but in 1840 the price of a human life, a slave, was worth $1,000.00.

Example Text : Today I'd like to tell you about the Underground Railroad.

In your introduction, you need to adapt your speech to your audience. To keep audience members interested, tell them why your topic is important to them. To accomplish this task, you need to undertake audience analysis prior to creating the speech. Figure out who your audience members are, what things are important to them, what their biases may be, and what types of subjects/issues appeal to them. In the context of this class, some of your audience analysis is provided for you--most of your listeners are college students, so it is likely that they place some value on education, most of them are probably not bathing in money, and they live in Colorado. Consider these traits when you determine how to adapt to your audience.

As you research and write your speech, take note of references to issues that should be important to your audience. Include statements about aspects of your speech that you think will be of special interest to the audience in the introduction. By accomplishing this task, you give your listeners specific things with which they can identify. Audience adaptation will be included throughout the speech, but an effective introduction requires meaningful adaptation of the topic to the audience.

You need to find ways to get the members of your audience involved early in the speech. The following are some possible options to connect your speech to your audience:

Reference to the Occasion

Consider how the occasion itself might present an opportunity to heighten audience receptivity. Remind your listeners of an important date just passed or coming soon.

Example Text : This January will mark the 130th anniversary of a "giant interracial rally" organized by William Still which helped to end streetcar segregation in the city of Philadelphia (Katz i).

Reference to the Previous Speaker

Another possibility is to refer to a previous speaker to capitalize on the good will which already has been established or to build on the information presented.

Example Text : As Alice pointed out last week in her speech on the Olympic games of the ancient world, history can provide us with fascinating lessons.

The credibility statement establishes your qualifications as a speaker. You should come up with reasons why you are someone to listen to on this topic. Why do you have special knowledge or understanding of this topic? What can the audience learn from you that they couldn't learn from someone else? Credibility statements can refer to your extensive research on a topic, your life-long interest in an issue, your personal experience with a thing, or your desire to better the lives of your listeners by sifting through the topic and providing the crucial information.

Remember that Aristotle said that credibility, or ethos, consists of good sense, goodwill, and good moral character. Create the feeling that you possess these qualities by creatively stating that you are well-educated about the topic (good sense), that you want to help each member of the audience (goodwill), and that you are a decent person who can be trusted (good moral character). Once you establish your credibility, the audience is more likely to listen to you as something of an expert and to consider what you say to be the truth. It is often effective to include further references to your credibility throughout the speech by subtly referring to the traits mentioned above.

Show your listeners that you are qualified to speak by making a specific reference to a helpful resource. This is one way to demonstrate competence.

Example Text : In doing research for this topic, I came across an account written by one of these heroes that has deepened my understanding of the institution of slavery. Frederick Douglass', My Bondage and My Freedom, is the account of a man whose master's kindness made his slavery only more unbearable.

Your listeners want to believe that you have their best interests in mind. In the case of an informative speech, it is enough to assure them that this will be an interesting speech and that you, yourself, are enthusiastic about the topic.

Example Text : I hope you'll enjoy hearing about the heroism of the Underground Railroad as much as I have enjoyed preparing for this speech.

Preview the Main Points

The preview informs the audience about the speech's main points. You should preview every main body point and identify each as a separate piece of the body. The purpose of this preview is to let the audience members prepare themselves for the flow of the speech; therefore, you should word the preview clearly and concisely. Attempt to use parallel structure for each part of the preview and avoid delving into the main point; simply tell the audience what the main point will be about in general.

Use the preview to briefly establish your structure and then move on. Let the audience get a taste of how you will divide the topic and fulfill the thesis and then move on. This important tool will reinforce the information in the minds of your listeners. Here are two examples of a preview:

Simply identify the main points of the speech. Cover them in the same order that they will appear in the body of the presentation.

For example, the preview for a speech about kites organized topically might take this form: "First, I will inform you about the invention of the kite. Then, I will explain the evolution of the kite. Third, I will introduce you to the different types of kites. Finally, I will inform you about various uses for kites." Notice that this preview avoids digressions (e.g., listing the various uses for kites); you will take care of the deeper information within the body of the speech.

Example Text : I'll tell you about motivations and means of escape employed by fugitive slaves.

Chronological

For example, the preview for a speech about the Pony Express organized chronologically might take this form: "I'll talk about the Pony Express in three parts. First, its origins, second, its heyday, and third, how it came to an end." Notice that this preview avoids digressions (e.g., listing the reasons why the Pony Express came to an end); you will cover the deeper information within the body of the speech.

Example Text : I'll talk about it in three parts. First, its origins, second, its heyday, and third, how it came to an end.

After you accomplish the first five components of the introduction, you should make a clean transition to the body of the speech. Use this transition to signal a change and prepare the audience to begin processing specific topical information. You should round out the introduction, reinforce the excitement and interest that you created in the audience during the introduction, and slide into the first main body point.

Strategic organization helps increase the clarity and effectiveness of your speech. Four key issues are discussed in this section:

Organizational Patterns

Connective devices, references to outside research.

The body contains the bulk of information in your speech and needs to be clearly organized. Without clear organization, the audience will probably forget your information, main points, perhaps even your thesis. Some simple strategies will help you create a clear, memorable speech. Below are the four key issues used in organizing a speech.

Once you settle on a topic, you should decide which aspects of that topic are of greatest importance for your speech. These aspects become your main points. While there is no rule about how many main points should appear in the body of the speech, most students go with three main points. You must have at least two main points; aside from that rule, you should select your main points based on the importance of the information and the time limitations. Be sure to include whatever information is necessary for the audience to understand your topic. Also, be sure to synthesize the information so it fits into the assigned time frame. As you choose your main points, try to give each point equal attention within the speech. If you pick three main points, each point should take up roughly one-third of the body section of your speech.

There are four basic patterns of organization for an informative speech.

- Chronological order

- Spatial order

- Causal order

- Topical order

There are four basic patterns of organization for an informative speech. You can choose any of these patterns based on which pattern serves the needs of your speech.

Chronological Order

A speech organized chronologically has main points oriented toward time. For example, a speech about the Farm Aid benefit concert could have main points organized chronologically. The first main point focuses on the creation of the event; the second main point focuses on the planning stages; the third point focuses on the actual performance/concert; and the fourth point focuses on donations and assistance that resulted from the entire process. In this format, you discuss main points in an order that could be followed on a calendar or a clock.

Spatial Order

A speech organized spatially has main points oriented toward space or a directional pattern. The Farm Aid speech's body could be organized in spatial order. The first main point discusses the New York branch of the organization; the second main point discusses the Midwest branch; the third main point discusses the California branch of Farm Aid. In this format, you discuss main points in an order that could be traced on a map.

Causal Order

A speech organized causally has main points oriented toward cause and effect. The main points of a Farm Aid speech organized causally could look like this: the first main point informs about problems on farms and the need for monetary assistance; the second main point discusses the creation and implementation of the Farm Aid program. In this format, you discuss main points in an order that alerts the audience to a problem or circumstance and then tells the audience what action resulted from the original circumstance.

Topical Order

A speech organized topically has main points organized more randomly by sub-topics. The Farm Aid speech could be organized topically: the first main point discusses Farm Aid administrators; the second main point discusses performers; the third main point discusses sponsors; the fourth main point discusses audiences. In this format, you discuss main points in a more random order that labels specific aspects of the topic and addresses them in separate categories. Most speeches that are not organized chronologically, spatially, or causally are organized topically.

Within the body of your speech, you need clear internal structure. Connectives are devices used to create a clear flow between ideas and points within the body of your speech--they serve to tie the speech together. There are four main types of connective devices:

Transitions

Internal previews, internal summaries.

Within the body of your speech, you need clear internal structure. Think of connectives as hooks and ladders for the audience to use when moving from point-to-point within the body of your speech. These devices help re-focus the minds of audience members and remind them of which main point your information is supporting. The four main types of connective devices are:

Transitions are brief statements that tell the audience to shift gears between ideas. Transitions serve as the glue that holds the speech together and allow the audience to predict where the next portion of the speech will go. For example, once you have previewed your main points and you want to move from the introduction to the body of the Farm Aid speech, you might say: "To gain an adequate understanding of the intricacies of this philanthropic group, we need to look at some specific information about Farm Aid. We'll begin by looking at the administrative branch of this massive fund-raising organization."

Internal previews are used to preview the parts of a main point. Internal previews are more focused than, but serve the same purpose as, the preview you will use in the introduction of the speech. For example, you might create an internal preview for the complex main point dealing with Farm Aid performers: "In examining the Farm Aid performers, we must acknowledge the presence of entertainers from different genres of music--country and western, rhythm and blues, rock, and pop." The internal preview provides specific information for the audience if a main point is complex or potentially confusing.

Internal summaries are the reverse of internal previews. Internal summaries restate specific parts of a main point. To internally summarize the main point dealing with Farm Aid performers, you might say: "You now know what types of people perform at the Farm Aid benefit concerts. The entertainers come from a wide range of musical genres--country and western, rhythm and blues, rock, and pop." When using both internal previews and internal summaries, be sure to stylize the language in each so you do not become redundant.

Signposts are brief statements that remind the audience where you are within the speech. If you have a long point, you may want to remind the audience of what main point you are on: "Continuing my discussion of Farm Aid performers . . . "

When organizing the body of your speech, you will integrate several references to your research. The purpose of the informative speech is to allow you and the audience to learn something new about a topic. Additionally, source citations add credibility to your ideas. If you know a lot about rock climbing and you cite several sources who confirm your knowledge, the audience is likely to see you as a credible speaker who provides ample support for ideas.

Without these references, your speech is more like a story or a chance for you to say a few things you know. To complete this assignment satisfactorily, you must use source citations. Consult your textbook and instructor for specific information on how much supporting material you should use and about the appropriate style for source citations.

While the conclusion should be brief and tight, it has a few specific tasks to accomplish:

Re-assert/Reinforce the Thesis

Review the main points, close effectively.

Take a deep breath! If you made it to the conclusion, you are on the brink of finishing. Below are the tasks you should complete in your conclusion:

When making the transition to the conclusion, attempt to make clear distinctions (verbally and nonverbally) that you are now wrapping up the information and providing final comments about the topic. Refer back to the thesis from the introduction with wording that calls the original thesis into memory. Assert that you have accomplished the goals of your thesis statement and create the feeling that audience members who actively considered your information are now equipped with an understanding of your topic. Reinforce whatever mood/tone you chose for the speech and attempt to create a big picture of the speech.

Within the conclusion, re-state the main points of the speech. Since you have used parallel wording for your main points in the introduction and body, don't break that consistency in the conclusion. Frame the review so the audience will be reminded of the preview and the developed discussion of each main point. After the review, you may want to create a statement about why those main points fulfilled the goals of the speech.

Finish strongly. When you close your speech, craft statements that reinforce the message and leave the audience with a clear feeling about what was accomplished with your speech. You might finalize the adaptation by discussing the benefits of listening to the speech and explaining what you think audience members can do with the information.

Remember to maintain an informative tone for this speech. You should not persuade about beliefs or positions; rather, you should persuade the audience that the speech was worthwhile and useful. For greatest effect, create a closing line or paragraph that is artistic and effective. Much like the attention-getter, the closing line needs to be refined and practiced. Your close should stick with the audience and leave them interested in your topic. Take time to work on writing the close well and attempt to memorize it so you can directly address the audience and leave them thinking of you as a well-prepared, confident speaker.

Outlining an Informative Speech

Two types of outlines can help you prepare to deliver your speech. The complete sentence outline provides a useful means of checking the organization and content of your speech. The speaking outline is an essential aid for delivering your speech. In this section, we discuss both types of outlines.

Two types of outlines can help you prepare to deliver your speech. The complete sentence outline provides a useful means of checking the organization and content of your speech. The speaking outline is an essential aid for delivering your speech.

The Complete Sentence Outline

A complete sentence outline may not be required for your presentation. The following information is useful, however, in helping you prepare your speech.

The complete sentence outline helps you organize your material and thoughts and it serves as an excellent copy for editing the speech. The complete sentence outline is just what it sounds like: an outline format including every complete sentence (not fragments or keywords) that will be delivered during your speech.

Writing the Outline

You should create headings for the introduction, body, and conclusion and clearly signal shifts between these main speech parts on the outline. Use standard outline format. For instance, you can use Roman numerals, letters, and numbers to label the parts of the outline. Organize the information so the major headings contain general information and the sub-headings become more specific as they descend. Think of the outline as a funnel: you should make broad, general claims at the top of each part of the outline and then tighten the information until you have exhausted the point. Do this with each section of the outline. Be sure to consult with your instructor about specific aspects of the outline and refer to your course book for further information and examples.

Using the Outline

If you use this outline as it is designed to be used, you will benefit from it. You should start the outline well before your speech day and give yourself plenty of time to revise it. Attempt to have the final, clean copies ready two or three days ahead of time, so you can spend a day or two before your speech working on delivery. Prepare the outline as if it were a final term paper.

The Speaking Outline

Depending upon the assignment and the instructor, you may use a speaking outline during your presentation. The following information will be helpful in preparing your speech through the use of a speaking outline.

This outline should be on notecards and should be a bare bones outline taken from the complete sentence outline. Think of the speaking outline as train tracks to guide you through the speech.

Many speakers find it helpful to highlight certain words/passages or to use different colors for different parts of the speech. You will probably want to write out long or cumbersome quotations along with your source citation. Many times, the hardest passages to learn are those you did not write but were spoken by someone else. Avoid the temptation to over-do the speaking outline; many speakers write too much on the cards and their grades suffer because they read from the cards.

The best strategy for becoming comfortable with a speaking outline is preparation. You should prepare well ahead of time and spend time working with the notecards and memorizing key sections of your speech (the introduction and conclusion, in particular). Try to become comfortable with the extemporaneous style of speaking. You should be able to look at a few keywords on your outline and deliver eloquent sentences because you are so familiar with your material. You should spend approximately 80% of your speech making eye-contact with your audience.

Delivering an Informative Speech

For many speakers, delivery is the most intimidating aspect of public speaking. Although there is no known cure for nervousness, you can make yourself much more comfortable by following a few basic delivery guidelines. In this section, we discuss those guidelines.

The Five-Step Method for Improving Delivery

- Read aloud your full-sentence outline. Listen to what you are saying and adjust your language to achieve a good, clear, simple sentence structure.

- Practice the speech repeatedly from the speaking outline. Become comfortable with your keywords to the point that what you say takes the form of an easy, natural conversation.

- Practice the speech aloud...rehearse it until you are confident you have mastered the ideas you want to present. Do not be concerned about "getting it just right." Once you know the content, you will find the way that is most comfortable for you.

- Practice in front of a mirror, tape record your practice, and/or present your speech to a friend. You are looking for feedback on rate of delivery, volume, pitch, non-verbal cues (gestures, card-usage, etc.), and eye-contact.

- Do a dress rehearsal of the speech under conditions as close as possible to those of the actual speech. Practice the speech a day or two before in a classroom. Be sure to incorporate as many elements as possible in the dress rehearsal...especially visual aids.

It should be clear that coping with anxiety over delivering a speech requires significant advanced preparation. The speech needs to be completed several days beforehand so that you can effectively employ this five-step plan.

Anderson, Thad, & Ron Tajchman. (1994). Informative Speaking. Writing@CSU . Colorado State University. https://writing.colostate.edu/guides/guide.cfm?guideid=52

14.1 What is an Informative Speech?

“ The improvement of understanding is for two ends: first our own increase for knowledge; secondly, to enable us to deliver that knowledge to others.” -John Locke

Defining what an informative speech is can be both straight-forward and somewhat tricky at the same time. Very simply, an informative speech can first be defined as a speech based entirely and exclusively on facts. Basically, an informative speech conveys knowledge, a task that every person engages in every day in some form or another. Whether giving someone who is lost driving directions, explaining the specials of the day as a server, or describing the plot of a movie to friends, people engage in forms of informative speaking daily. Secondly, an informative speech does not attempt to convince the audience that one thing is better than another. It does not advocate a course of action.

Consider the following two statements:

2 + 2 = 4 George Washington was the first President of the United States.

In each case, the statement made is what can be described as irrefutable , meaning a statement or claim that cannot be argued. In the first example, even small children are taught that having two apples and then getting two more apples will result in having four apples. This statement is irrefutable in that no one in the world will (or should!) argue this: It is a fact.

Similarly, with the statement “George Washington was the first President of the United States,” this again is an irrefutable fact. If you asked one hundred history professors and read one hundred history textbooks, the professors and textbooks would all say the same thing: Washington was the first president. No expert, reliable source, or person with any common sense would argue about this.

(Someone at this point might say, “No, John Hanson was the first president.” However, he was president under the Articles of Confederation for a short period—November 5, 1781, to November 3, 1782—not under our present Constitution. This example shows the importance of stating your facts clearly and precisely and being able to cite their origins.)

Therefore, an informative speech should not incorporate opinion as its basis. This can be the tricky part of developing an informative speech, because some opinion statements sometimes sound like facts (since they are generally agreed upon by many people), but are really opinion.

For example, in an informative speech on George Washington, you might say, “George Washington was one of the greatest presidents in the history of the United States.” While this statement may be agreed upon by most people, it is possible for some people to disagree and argue the opposite point of view. The statement “George Washington was one of the greatest presidents in the history of the United States” is not irrefutable, meaning someone could argue this claim. If, however, you present the opinion as an opinion from a source, that is acceptable: it is a fact that someone (hopefully someone with expertise) holds the opinion. You do not want your central idea, your main points, and the majority of your supporting material to be opinion or argument in an informative speech.

Additionally, you should never take sides on an issue in an informative speech, nor should you “spin” the issue in order to influence the opinions of the listeners. Even if you are informing the audience about differences in views on controversial topics, you should simply and clearly explain the issues. This is not to say, however, that the audience’s needs and interests have nothing to do with the informative speech. We come back to the WIIFM principle (“What’s in it for me?) because even though an informative speech is fact-based, it still needs to relate to people’s lives in order to maintain their attention.

The question may arise here, “If we can find anything on the Internet now, why bother to give an informative speech?” The answer lies in the unique relationship between audience and speaker found in the public speaking context. The speaker can choose to present information that is of most value to the audience. Secondly, the speaker is not just overloading the audience with data. As we have mentioned before, that’s not really a good idea because audiences cannot remember great amounts of data and facts after listening. The focus of the content is what matters. This is where the specific purpose and central idea come into play. Remember, public speaking is not a good way to “dump data” on the audience, but to make information meaningful.

Finally, although we have stressed that the informative speech is fact-based and does not have the purpose of persuasion, information still has an indirect effect on someone. If a classmate gives a speech on correctly using the Heimlich Maneuver to help a choking victim, the side effect (and probably desired result) is that the audience would use it when confronted with the situation.

With his informative speech about the traditions of OSU looming, Pistol Pete knew he needed to ensure his preparation outline was in tip-top shape. While he was confident about his content, he wanted to make certain his structure was clear and cohesive. Who better to help with that than the experts at the OSU Writing Center?

As he approached the Writing Center, Pete felt a mix of nervousness and excitement. The Writing Center had a reputation for being a resourceful hub, a place where many students had honed their writing skills.

He was greeted warmly by a student consultant named Sarah. “How can I help you today, Pistol Pete?” she asked with a smile. Pete explained his assignment and his desire to refine his preparation outline.

Sarah began by asking Pete about his main objectives for the speech. As he shared his thoughts, she listened attentively, jotting down notes. She then asked to see the current state of his outline. As Pete handed it over, he explained his three main points and how he intended to delve into each one.

Sarah reviewed the outline, making annotations. She noticed that while Pete had a wealth of information, it would be beneficial to reorganize some points to improve flow and cohesiveness. They worked together to structure the outline, ensuring each point logically led to the next.

She also gave Pete tips on effective transitions to maintain audience engagement and create a seamless progression between points. Pete, always eager to learn, scribbled down notes, asking questions when needed.

Noticing that Pete had included a lot of historical details in his outline, Sarah suggested incorporating personal anecdotes or experiences related to the traditions to add a touch of relatability. Pete loved the idea and thought of a couple of personal stories he could weave in.

Before wrapping up, Sarah directed Pete to some online resources available through the Writing Center’s website, which could further help him refine his speech. She also reminded him about the importance of rehearsing his speech multiple times to ensure it flowed smoothly with the revised outline.

Pistol Pete left the Writing Center feeling empowered and grateful. Sarah’s guidance had transformed his outline into a clear and engaging roadmap for his speech. He felt more prepared than ever to share the rich traditions of OSU with his audience, all thanks to the support he received at the Writing Center. Have you ever visited the Writing Center on campus?

a speech based entirely and exclusively on facts and whose main purpose is to inform rather than persuade, amuse, or inspire

a statement or claim that cannot be argued

a personal view, attitude, or belief about something

Introduction to Speech Communication Copyright © 2021 by Individual authors retain copyright of their work. is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

The Art of Public Speaking

“There are always three speeches, for every one you actually gave. The one you practiced, the one you gave, and the one you wish you gave.” –Dale Carnegie

Writing an Informative Speech

Part 1: As the title denotes, an informative speech is speech that informs people. But why should people listen to you instead of reading an article online? To draw audiences’ attention to your informative speech, you will need to – -Know the content well by doing thorough research so your audiences will learn from your expertise. -Provide accurate information on the topic you are speaking about since your audience will rely on your expertise and diligence. -Show passion about the topic that will inspire your audience’s interests. -Make the subject matter for your audience by revealing the “universal truth”, which matters not only you but everyone else who hears it. -Connect with your audience by making your information sound interesting and personal through story telling. -Apply rhetorical appeals to enhance the purpose of your speech.

Part 2: Watch two Ted talks.

First, a TedTalk video about a doctor who gave us modern pain relief( https://www.ted.com/talks/latif_nasser_the_amazing_story_of_the_man_who_gave_us_modern_pain_relief );

Secondly, a Ted Talk about Decentralized Internet( https://www.ted.com/talks/tamas_kocsis_the_case_for_a_decentralized_internet ).

Use the speech guidelines above to analyze both speech and their delivery using our speech rubric.

Resources for informative speeches: https://www.ted.com/search?q=Informative

Types of Informative Speeches:

Speaking to Inform

How to Narrow Down Topics for your Research

- Do a Quick –dirty research using google search engine

- Gather general information about the person or event or landmark or anything else you may be interested in finding more information

- Categorize the information

- Use” Why Does It Matter” or “ How does it connect to ‘now’?” to help you decide which category of information you will use as the focus

- Once you have the category, you will go to data bases to do in-depth research to collect more specific information on the topic.

- Use the information to tell a story

- Select information by asking “Why do I want to speak about this? Will my audience be interested? Why?”

- What’s the universal truth you want to reveal? Why should the audience care?

A Sample Essay

Informative speaking, welcome to informative speaking.

An informative speech conveys knowledge, a task that you’ve engaged in throughout your life. When you give driving directions, you convey knowledge. When you caution someone about crossing the street at a certain intersection, you are describing a dangerous situation. When you steer someone away from using the car pool lane, you are explaining what it’s for.

When your professors greet you on the first day of a new academic term, they typically hand out a course syllabus, which informs you about the objectives and expectations of the course. Much of the information comes to have greater meaning as you actually encounter your coursework. Why doesn’t the professor explain those meanings on the first day? He or she probably does, but in all likelihood, the explanation won’t really make sense at the time because you don’t yet have the supporting knowledge to put it in context.

However, it is still important that the orientation information be offered. It is likely to answer some specific questions, such as the following: Am I prepared to take this course? Is a textbook required? Will the course involve a great deal of writing? Does the professor have office hours? The answers to these questions should be of central importance to all the students. These orientations are informative because they give important information relevant to the course.

An informative speech does not attempt to convince the audience that one thing is better than another. It does not advocate a course of action. Let’s say, for instance, that you have carefully followed the news about BP’s Deepwater Horizon oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico. Let’s further say that you felt outraged by the sequence of events that led to the spill and, even more so, by its consequences. Consider carefully whether this is a good topic for your informative speech. If your speech describes the process of offshore oil exploration, it will be informative. However, if it expresses your views on what petroleum corporations should do to safeguard their personnel and the environment, save that topic for a persuasive speech.

Being honest about your private agenda in choosing a topic is important. It is not always easy to discern a clear line between informative and persuasive speech. Good information has a strong tendency to be persuasive, and persuasion relies on good information. Thus informative and persuasive speaking do overlap. It remains up to you to examine your real motives in choosing your topic. As we have said in various ways, ethical speaking means respecting the intelligence of your audience. If you try to circumvent the purpose of the informative speech in order to plant a persuasive seed, your listeners will notice. Such strategies often come across as dishonest.

16.1 Informative Speaking Goals

Learning objectives.

- Explain the importance of accuracy, clarity, and listener interest in informative speaking.

- Discuss why speaking to inform is important. Identify strategies for making information clear and interesting to your speaking audience.

A good informative speech conveys accurate information to the audience in a way that is clear and that keeps the listener interested in the topic. Achieving all three of these goals—accuracy, clarity, and interest—is the key to your effectiveness as a speaker. If information is inaccurate, incomplete, or unclear, it will be of limited usefulness to the audience. There is no topic about which you can give complete information, and therefore, we strongly recommend careful narrowing. With a carefully narrowed topic and purpose, it is possible to give an accurate picture that isn’t misleading.

Part of being accurate is making sure that your information is current. Even if you know a great deal about your topic or wrote a good paper on the topic in a high school course, you need to verify the accuracy and completeness of what you know. Most people understand that technology changes rapidly, so you need to update your information almost constantly, but the same is true for topics that, on the surface, may seem to require less updating. For example, the American Civil War occurred 150 years ago, but contemporary research still offers new and emerging theories about the causes of the war and its long-term effects. So even with a topic that seems to be unchanging, you need to carefully check your information to be sure it’s accurate and up to date.

In order for your listeners to benefit from your speech, you must convey your ideas in a fashion that your audience can understand. The clarity of your speech relies on logical organization and understandable word choices. You should not assume that something that’s obvious to you will also be obvious to the members of your audience. Formulate your work with the objective of being understood in all details, and rehearse your speech in front of peers who will tell you whether the information in your speech makes sense.

In addition to being clear, your speech should be interesting. Your listeners will benefit the most if they can give sustained attention to the speech, and this is unlikely to happen if they are bored. This often means you will decide against using some of the topics you know a great deal about. Suppose, for example, that you had a summer job as a veterinary assistant and learned a great deal about canine parasites. This topic might be very interesting to you, but how interesting will it be to others in your class? In order to make it interesting, you will need to find a way to connect it with their interests and curiosities. Perhaps there are certain canine parasites that also pose risks to humans—this might be a connection that would increase audience interest in your topic.

Why We Speak to Inform

Informative speaking is a means for the delivery of knowledge. In informative speaking, we avoid expressing opinion.

This doesn’t mean you may not speak about controversial topics. However, if you do so, you must deliver a fair statement of each side of the issue in debate. If your speech is about standardized educational testing, you must honestly represent the views both of its proponents and of its critics. You must not take sides, and you must not slant your explanation of the debate in order to influence the opinions of the listeners. You are simply and clearly defining the debate. If you watch the evening news on a major network television (ABC, CBS, or NBC), you will see newscasters who undoubtedly have personal opinions about the news, but are trained to avoid expressing those opinions through the use of loaded words, gestures, facial expressions, or vocal tone. Like those newscasters, you are already educating your listeners simply by informing them. Let them make up their own minds. This is probably the most important reason for informative speaking.

Making Information Clear and Interesting for the Audience

A clear and interesting speech can make use of description, causal analysis, or categories. With description, you use words to create a picture in the minds of your audience. You can describe physical realities, social realities, emotional experiences, sequences, consequences, or contexts. For instance, you can describe the mindset of the Massachusetts town of Salem during the witch trials. You can also use causal analysis, which focuses on the connections between causes and consequences. For example, in speaking about health care costs, you could explain how a serious illness can put even a well-insured family into bankruptcy. You can also use categories to group things together. For instance, you could say that there are three categories of investment for the future: liquid savings, avoiding debt, and acquiring properties that will increase in value.

There are a number of principles to keep in mind as a speaker to make the information you present clear and interesting for your audience. Let’s examine several of them.

Adjust Complexity to the Audience

If your speech is too complex or too simplistic, it will not hold the interest of your listeners. How can you determine the right level of complexity? Your audience analysis is one important way to do this. Will your listeners belong to a given age group, or are they more diverse? Did they all go to public schools in the United States, or are some of your listeners international students? Are they all students majoring in communication studies, or is there a mixture of majors in your audience? The answers to these and other audience analysis questions will help you to gauge what they know and what they are curious about.

Never assume that just because your audience is made up of students, they all share your knowledge set. If you base your speech on an assumption of similar knowledge, you might not make sense to everyone. If, for instance, you’re an intercultural communication student discussing multiple identities , the psychology students in your audience will most likely reject your message. Similarly, the term “viral” has very different meanings depending on whether it is used with respect to human disease, popular response to a website, or population theory. In using the word “viral,” you absolutely must explain specifically what you mean. You should not hurry your explanation of a term that’s vulnerable to misinterpretation. Make certain your listeners know what you mean before continuing your speech. Stephen Lucas explains, “You cannot assume they will know what you mean. Rather, you must be sure to explain everything so thoroughly that they cannot help but understand.”Lucas, Stephen E. (2004). The art of public speaking . Boston: McGraw-Hill. Define terms to help listeners understand them the way you mean them to. Give explanations that are consistent with your definitions, and show how those ideas apply to your speech topic. In this way, you can avoid many misunderstandings.

Similarly, be very careful about assuming there is anything that “everybody knows.” Suppose you’ve decided to present an informative speech on the survival of the early colonists of New England. You may have learned in elementary school that their survival was attributable, in part, to the assistance of Squanto. Many of your listeners will know which states are in New England, but if there are international students in the audience, they might never have heard of New England. You should clarify the term either by pointing out the region on a map or by stating that it’s the six states in the American northeast. Other knowledge gaps can still confound the effectiveness of the speech. For instance, who or what was Squanto? What kind of assistance did the settlers get? Only a few listeners are likely to know that Squanto spoke English and that fact had greatly surprised the settlers when they landed. It was through his knowledge of English that Squanto was able to advise these settlers in survival strategies during that first harsh winter. If you neglect to provide that information, your speech will not be fully informative.

Beyond the opportunity to help improve your delivery, one important outcome of practicing your speech in front of a live audience of a couple of friends or classmates is that you can become aware of terms that are confusing or that you should define for your audience.

Avoid Unnecessary Jargon

If you decide to give an informative speech on a highly specialized topic, limit how much technical language or jargon you use. Loading a speech with specialized language has the potential to be taxing on the listeners. It can become too difficult to “translate” your meanings, and if that happens, you will not effectively deliver information. Even if you define many technical terms, the audience may feel as if they are being bombarded with a set of definitions instead of useful information. Don’t treat your speech as a crash course in an entire topic. If you must, introduce one specialized term and carefully define and explain it to the audience. Define it in words, and then use a concrete and relevant example to clarify the meaning.

Some topics, by their very nature, are too technical for a short speech. For example, in a five-minute speech you would be foolish to try to inform your audience about the causes of the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear emergency that occurred in Japan in 2011. Other topics, while technical, can be presented in audience-friendly ways that minimize the use of technical terms. For instance, in a speech about Mount Vesuvius, the volcano that buried the ancient cities of Pompeii and Herculaneum, you can use the term “pyroclastic flow” as long as you take the time to either show or tell what it means.

Create Concrete Images

As a college student, you have had a significant amount of exposure to abstract terms. You have become comfortable using and hearing a variety of abstract ideas. However, abstract terms lend themselves to many interpretations. For instance, the abstract term “responsibility” can mean many things. Among other meanings, it can mean duty, task, authority, or blame. Because of the potential for misunderstanding, it is better to use a concrete word. For example, instead of saying, “Helen Worth was responsible for the project,” you will convey clearer meaning when you say, “Helen Worth was in charge of the project,” “Helen Kimes made the project a success,” or “Helen Worth was to blame for the failure of the project.”

To illustrate the differences between abstract and concrete language, let’s look at a few pairs of terms:

By using an abstraction in a sentence and then comparing the concrete term in the sentence, you will notice the more precise meanings of the concrete terms. Those precise terms are less likely to be misunderstood. In the last pair of terms, “knowledgeable” is listed as a concrete term, but it can also be considered an abstract term. Still, it’s likely to be much clearer and more precise than “profound.”

Keep Information Limited

When you developed your speech, you carefully narrowed your topic in order to keep information limited yet complete and coherent. If you carefully adhere to your own narrowing, you can keep from going off on tangents or confusing your audience. If you overload your audience with information, they will be unable to follow your narrative. Use the definitions, descriptions, explanations, and examples you need in order to make your meanings clear, but resist the temptation to add tangential information merely because you find it interesting.

Link Current Knowledge to New Knowledge

Certain sets of knowledge are common to many people in your classroom audience. For instance, most of them know what Wikipedia is. Many have found it a useful and convenient source of information about topics related to their coursework. Because many Wikipedia entries are lengthy, greatly annotated, and followed by substantial lists of authoritative sources, many students have relied on information acquired from Wikipedia in writing papers to fulfill course requirements. All this is information that virtually every classroom listener is likely to know. This is the current knowledge of your audience.

Because your listeners are already familiar with Wikipedia, you can link important new knowledge to their already-existing knowledge. Wikipedia is an “open source,” meaning that anyone can supplement, edit, correct, distort, or otherwise alter the information in Wikipedia. In addition to your listeners’ knowledge that a great deal of good information can be found in Wikipedia, they must now know that it isn’t authoritative. Some of your listeners may not enjoy hearing this message, so you must find a way to make it acceptable.

One way to make the message acceptable to your listeners is to show what Wikipedia does well. For example, some Wikipedia entries contain many good references at the end. Most of those references are likely to be authoritative, having been written by scholars. In searching for information on a topic, a student can look up one or more of those references in full-text databases or in the library. In this way, Wikipedia can be helpful in steering a student toward the authoritative information they need. Explaining this to your audience will help them accept, rather than reject, the bad news about Wikipedia.

Make It Memorable

If you’ve already done the preliminary work in choosing a topic, finding an interesting narrowing of that topic, developing and using presentation aids, and working to maintain audience contact, your delivery is likely to be memorable. Now you can turn to your content and find opportunities to make it appropriately vivid. You can do this by using explanations, comparisons, examples, or language.

Let’s say that you’re preparing a speech on the United States’ internment of Japanese American people from the San Francisco Bay area during World War II. Your goal is to paint a memorable image in your listeners’ minds. You can do this through a dramatic contrast, before and after. You could say, “In 1941, the Bay area had a vibrant and productive community of Japanese American citizens who went to work every day, opening their shops, typing reports in their offices, and teaching in their classrooms, just as they had been doing for years. But on December 7, 1941, everything changed. Within six months, Bay area residents of Japanese ancestry were gone, transported to internment camps located hundreds of miles from the Pacific coast.”

This strategy rests on the ability of the audience to visualize the two contrasting situations. You have alluded to two sets of images that are familiar to most college students, images that they can easily visualize. Once the audience imagination is engaged in visualization, they are likely to remember the speech.

Your task of providing memorable imagery does not stop after the introduction. While maintaining an even-handed approach that does not seek to persuade, you must provide the audience with information about the circumstances that triggered the policy of internment, perhaps by describing the advice that was given to President Roosevelt by his top advisers. You might depict the conditions faced by Japanese Americans during their internment by describing a typical day one of the camps. To conclude your speech on a memorable note, you might name a notable individual—an actor, writer, or politician—who is a survivor of the internment.

Such a strategy might feel unnatural to you. After all, this is not how you talk to your friends or participate in a classroom discussion. Remember, though, that public speaking is not the same as talking. It’s prepared and formal. It demands more of you. In a conversation, it might not be important to be memorable; your goal might merely be to maintain friendship. But in a speech, when you expect the audience to pay attention, you must make the speech memorable.

Make It Relevant and Useful

When thinking about your topic, it is always very important to keep your audience members center stage in your mind. For instance, if your speech is about air pollution, ask your audience to imagine feeling the burning of eyes and lungs caused by smog. This is a strategy for making the topic more real to them, since it may have happened to them on a number of occasions; and even if it hasn’t, it easily could. If your speech is about Mark Twain, instead of simply saying that he was very famous during his lifetime, remind your audience that he was so prominent that their own great-grandparents likely knew of his work and had strong opinions about it. In so doing, you’ve connected your topic to their own forebears.

Personalize Your Content

Giving a human face to a topic helps the audience perceive it as interesting. If your topic is related to the Maasai rite of passage into manhood, the prevalence of drug addiction in a particular locale, the development of a professional filmmaker, or the treatment of a disease, putting a human face should not be difficult. To do it, find a case study you can describe within the speech, referring to the human subject by name. This conveys to the audience that these processes happen to real people.