How To Write A Dissertation Or Thesis

8 straightforward steps to craft an a-grade dissertation.

By: Derek Jansen (MBA) Expert Reviewed By: Dr Eunice Rautenbach | June 2020

Writing a dissertation or thesis is not a simple task. It takes time, energy and a lot of will power to get you across the finish line. It’s not easy – but it doesn’t necessarily need to be a painful process. If you understand the big-picture process of how to write a dissertation or thesis, your research journey will be a lot smoother.

In this post, I’m going to outline the big-picture process of how to write a high-quality dissertation or thesis, without losing your mind along the way. If you’re just starting your research, this post is perfect for you. Alternatively, if you’ve already submitted your proposal, this article which covers how to structure a dissertation might be more helpful.

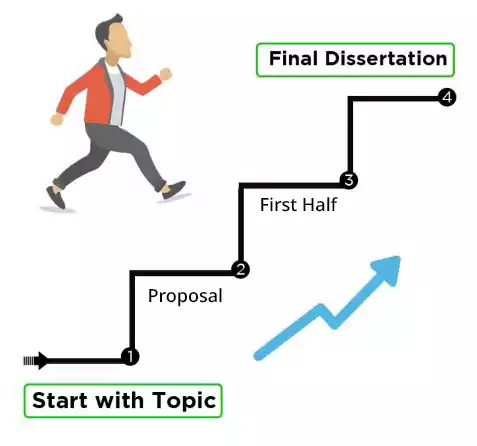

How To Write A Dissertation: 8 Steps

- Clearly understand what a dissertation (or thesis) is

- Find a unique and valuable research topic

- Craft a convincing research proposal

- Write up a strong introduction chapter

- Review the existing literature and compile a literature review

- Design a rigorous research strategy and undertake your own research

- Present the findings of your research

- Draw a conclusion and discuss the implications

Step 1: Understand exactly what a dissertation is

This probably sounds like a no-brainer, but all too often, students come to us for help with their research and the underlying issue is that they don’t fully understand what a dissertation (or thesis) actually is.

So, what is a dissertation?

At its simplest, a dissertation or thesis is a formal piece of research , reflecting the standard research process . But what is the standard research process, you ask? The research process involves 4 key steps:

- Ask a very specific, well-articulated question (s) (your research topic)

- See what other researchers have said about it (if they’ve already answered it)

- If they haven’t answered it adequately, undertake your own data collection and analysis in a scientifically rigorous fashion

- Answer your original question(s), based on your analysis findings

In short, the research process is simply about asking and answering questions in a systematic fashion . This probably sounds pretty obvious, but people often think they’ve done “research”, when in fact what they have done is:

- Started with a vague, poorly articulated question

- Not taken the time to see what research has already been done regarding the question

- Collected data and opinions that support their gut and undertaken a flimsy analysis

- Drawn a shaky conclusion, based on that analysis

If you want to see the perfect example of this in action, look out for the next Facebook post where someone claims they’ve done “research”… All too often, people consider reading a few blog posts to constitute research. Its no surprise then that what they end up with is an opinion piece, not research. Okay, okay – I’ll climb off my soapbox now.

The key takeaway here is that a dissertation (or thesis) is a formal piece of research, reflecting the research process. It’s not an opinion piece , nor a place to push your agenda or try to convince someone of your position. Writing a good dissertation involves asking a question and taking a systematic, rigorous approach to answering it.

If you understand this and are comfortable leaving your opinions or preconceived ideas at the door, you’re already off to a good start!

Step 2: Find a unique, valuable research topic

As we saw, the first step of the research process is to ask a specific, well-articulated question. In other words, you need to find a research topic that asks a specific question or set of questions (these are called research questions ). Sounds easy enough, right? All you’ve got to do is identify a question or two and you’ve got a winning research topic. Well, not quite…

A good dissertation or thesis topic has a few important attributes. Specifically, a solid research topic should be:

Let’s take a closer look at these:

Attribute #1: Clear

Your research topic needs to be crystal clear about what you’re planning to research, what you want to know, and within what context. There shouldn’t be any ambiguity or vagueness about what you’ll research.

Here’s an example of a clearly articulated research topic:

An analysis of consumer-based factors influencing organisational trust in British low-cost online equity brokerage firms.

As you can see in the example, its crystal clear what will be analysed (factors impacting organisational trust), amongst who (consumers) and in what context (British low-cost equity brokerage firms, based online).

Need a helping hand?

Attribute #2: Unique

Your research should be asking a question(s) that hasn’t been asked before, or that hasn’t been asked in a specific context (for example, in a specific country or industry).

For example, sticking organisational trust topic above, it’s quite likely that organisational trust factors in the UK have been investigated before, but the context (online low-cost equity brokerages) could make this research unique. Therefore, the context makes this research original.

One caveat when using context as the basis for originality – you need to have a good reason to suspect that your findings in this context might be different from the existing research – otherwise, there’s no reason to warrant researching it.

Attribute #3: Important

Simply asking a unique or original question is not enough – the question needs to create value. In other words, successfully answering your research questions should provide some value to the field of research or the industry. You can’t research something just to satisfy your curiosity. It needs to make some form of contribution either to research or industry.

For example, researching the factors influencing consumer trust would create value by enabling businesses to tailor their operations and marketing to leverage factors that promote trust. In other words, it would have a clear benefit to industry.

So, how do you go about finding a unique and valuable research topic? We explain that in detail in this video post – How To Find A Research Topic . Yeah, we’ve got you covered 😊

Step 3: Write a convincing research proposal

Once you’ve pinned down a high-quality research topic, the next step is to convince your university to let you research it. No matter how awesome you think your topic is, it still needs to get the rubber stamp before you can move forward with your research. The research proposal is the tool you’ll use for this job.

So, what’s in a research proposal?

The main “job” of a research proposal is to convince your university, advisor or committee that your research topic is worthy of approval. But convince them of what? Well, this varies from university to university, but generally, they want to see that:

- You have a clearly articulated, unique and important topic (this might sound familiar…)

- You’ve done some initial reading of the existing literature relevant to your topic (i.e. a literature review)

- You have a provisional plan in terms of how you will collect data and analyse it (i.e. a methodology)

At the proposal stage, it’s (generally) not expected that you’ve extensively reviewed the existing literature , but you will need to show that you’ve done enough reading to identify a clear gap for original (unique) research. Similarly, they generally don’t expect that you have a rock-solid research methodology mapped out, but you should have an idea of whether you’ll be undertaking qualitative or quantitative analysis , and how you’ll collect your data (we’ll discuss this in more detail later).

Long story short – don’t stress about having every detail of your research meticulously thought out at the proposal stage – this will develop as you progress through your research. However, you do need to show that you’ve “done your homework” and that your research is worthy of approval .

So, how do you go about crafting a high-quality, convincing proposal? We cover that in detail in this video post – How To Write A Top-Class Research Proposal . We’ve also got a video walkthrough of two proposal examples here .

Step 4: Craft a strong introduction chapter

Once your proposal’s been approved, its time to get writing your actual dissertation or thesis! The good news is that if you put the time into crafting a high-quality proposal, you’ve already got a head start on your first three chapters – introduction, literature review and methodology – as you can use your proposal as the basis for these.

Handy sidenote – our free dissertation & thesis template is a great way to speed up your dissertation writing journey.

What’s the introduction chapter all about?

The purpose of the introduction chapter is to set the scene for your research (dare I say, to introduce it…) so that the reader understands what you’ll be researching and why it’s important. In other words, it covers the same ground as the research proposal in that it justifies your research topic.

What goes into the introduction chapter?

This can vary slightly between universities and degrees, but generally, the introduction chapter will include the following:

- A brief background to the study, explaining the overall area of research

- A problem statement , explaining what the problem is with the current state of research (in other words, where the knowledge gap exists)

- Your research questions – in other words, the specific questions your study will seek to answer (based on the knowledge gap)

- The significance of your study – in other words, why it’s important and how its findings will be useful in the world

As you can see, this all about explaining the “what” and the “why” of your research (as opposed to the “how”). So, your introduction chapter is basically the salesman of your study, “selling” your research to the first-time reader and (hopefully) getting them interested to read more.

How do I write the introduction chapter, you ask? We cover that in detail in this post .

Step 5: Undertake an in-depth literature review

As I mentioned earlier, you’ll need to do some initial review of the literature in Steps 2 and 3 to find your research gap and craft a convincing research proposal – but that’s just scratching the surface. Once you reach the literature review stage of your dissertation or thesis, you need to dig a lot deeper into the existing research and write up a comprehensive literature review chapter.

What’s the literature review all about?

There are two main stages in the literature review process:

Literature Review Step 1: Reading up

The first stage is for you to deep dive into the existing literature (journal articles, textbook chapters, industry reports, etc) to gain an in-depth understanding of the current state of research regarding your topic. While you don’t need to read every single article, you do need to ensure that you cover all literature that is related to your core research questions, and create a comprehensive catalogue of that literature , which you’ll use in the next step.

Reading and digesting all the relevant literature is a time consuming and intellectually demanding process. Many students underestimate just how much work goes into this step, so make sure that you allocate a good amount of time for this when planning out your research. Thankfully, there are ways to fast track the process – be sure to check out this article covering how to read journal articles quickly .

Literature Review Step 2: Writing up

Once you’ve worked through the literature and digested it all, you’ll need to write up your literature review chapter. Many students make the mistake of thinking that the literature review chapter is simply a summary of what other researchers have said. While this is partly true, a literature review is much more than just a summary. To pull off a good literature review chapter, you’ll need to achieve at least 3 things:

- You need to synthesise the existing research , not just summarise it. In other words, you need to show how different pieces of theory fit together, what’s agreed on by researchers, what’s not.

- You need to highlight a research gap that your research is going to fill. In other words, you’ve got to outline the problem so that your research topic can provide a solution.

- You need to use the existing research to inform your methodology and approach to your own research design. For example, you might use questions or Likert scales from previous studies in your your own survey design .

As you can see, a good literature review is more than just a summary of the published research. It’s the foundation on which your own research is built, so it deserves a lot of love and attention. Take the time to craft a comprehensive literature review with a suitable structure .

But, how do I actually write the literature review chapter, you ask? We cover that in detail in this video post .

Step 6: Carry out your own research

Once you’ve completed your literature review and have a sound understanding of the existing research, its time to develop your own research (finally!). You’ll design this research specifically so that you can find the answers to your unique research question.

There are two steps here – designing your research strategy and executing on it:

1 – Design your research strategy

The first step is to design your research strategy and craft a methodology chapter . I won’t get into the technicalities of the methodology chapter here, but in simple terms, this chapter is about explaining the “how” of your research. If you recall, the introduction and literature review chapters discussed the “what” and the “why”, so it makes sense that the next point to cover is the “how” –that’s what the methodology chapter is all about.

In this section, you’ll need to make firm decisions about your research design. This includes things like:

- Your research philosophy (e.g. positivism or interpretivism )

- Your overall methodology (e.g. qualitative , quantitative or mixed methods)

- Your data collection strategy (e.g. interviews , focus groups, surveys)

- Your data analysis strategy (e.g. content analysis , correlation analysis, regression)

If these words have got your head spinning, don’t worry! We’ll explain these in plain language in other posts. It’s not essential that you understand the intricacies of research design (yet!). The key takeaway here is that you’ll need to make decisions about how you’ll design your own research, and you’ll need to describe (and justify) your decisions in your methodology chapter.

2 – Execute: Collect and analyse your data

Once you’ve worked out your research design, you’ll put it into action and start collecting your data. This might mean undertaking interviews, hosting an online survey or any other data collection method. Data collection can take quite a bit of time (especially if you host in-person interviews), so be sure to factor sufficient time into your project plan for this. Oftentimes, things don’t go 100% to plan (for example, you don’t get as many survey responses as you hoped for), so bake a little extra time into your budget here.

Once you’ve collected your data, you’ll need to do some data preparation before you can sink your teeth into the analysis. For example:

- If you carry out interviews or focus groups, you’ll need to transcribe your audio data to text (i.e. a Word document).

- If you collect quantitative survey data, you’ll need to clean up your data and get it into the right format for whichever analysis software you use (for example, SPSS, R or STATA).

Once you’ve completed your data prep, you’ll undertake your analysis, using the techniques that you described in your methodology. Depending on what you find in your analysis, you might also do some additional forms of analysis that you hadn’t planned for. For example, you might see something in the data that raises new questions or that requires clarification with further analysis.

The type(s) of analysis that you’ll use depend entirely on the nature of your research and your research questions. For example:

- If your research if exploratory in nature, you’ll often use qualitative analysis techniques .

- If your research is confirmatory in nature, you’ll often use quantitative analysis techniques

- If your research involves a mix of both, you might use a mixed methods approach

Again, if these words have got your head spinning, don’t worry! We’ll explain these concepts and techniques in other posts. The key takeaway is simply that there’s no “one size fits all” for research design and methodology – it all depends on your topic, your research questions and your data. So, don’t be surprised if your study colleagues take a completely different approach to yours.

Step 7: Present your findings

Once you’ve completed your analysis, it’s time to present your findings (finally!). In a dissertation or thesis, you’ll typically present your findings in two chapters – the results chapter and the discussion chapter .

What’s the difference between the results chapter and the discussion chapter?

While these two chapters are similar, the results chapter generally just presents the processed data neatly and clearly without interpretation, while the discussion chapter explains the story the data are telling – in other words, it provides your interpretation of the results.

For example, if you were researching the factors that influence consumer trust, you might have used a quantitative approach to identify the relationship between potential factors (e.g. perceived integrity and competence of the organisation) and consumer trust. In this case:

- Your results chapter would just present the results of the statistical tests. For example, correlation results or differences between groups. In other words, the processed numbers.

- Your discussion chapter would explain what the numbers mean in relation to your research question(s). For example, Factor 1 has a weak relationship with consumer trust, while Factor 2 has a strong relationship.

Depending on the university and degree, these two chapters (results and discussion) are sometimes merged into one , so be sure to check with your institution what their preference is. Regardless of the chapter structure, this section is about presenting the findings of your research in a clear, easy to understand fashion.

Importantly, your discussion here needs to link back to your research questions (which you outlined in the introduction or literature review chapter). In other words, it needs to answer the key questions you asked (or at least attempt to answer them).

For example, if we look at the sample research topic:

In this case, the discussion section would clearly outline which factors seem to have a noteworthy influence on organisational trust. By doing so, they are answering the overarching question and fulfilling the purpose of the research .

For more information about the results chapter , check out this post for qualitative studies and this post for quantitative studies .

Step 8: The Final Step Draw a conclusion and discuss the implications

Last but not least, you’ll need to wrap up your research with the conclusion chapter . In this chapter, you’ll bring your research full circle by highlighting the key findings of your study and explaining what the implications of these findings are.

What exactly are key findings? The key findings are those findings which directly relate to your original research questions and overall research objectives (which you discussed in your introduction chapter). The implications, on the other hand, explain what your findings mean for industry, or for research in your area.

Sticking with the consumer trust topic example, the conclusion might look something like this:

Key findings

This study set out to identify which factors influence consumer-based trust in British low-cost online equity brokerage firms. The results suggest that the following factors have a large impact on consumer trust:

While the following factors have a very limited impact on consumer trust:

Notably, within the 25-30 age groups, Factors E had a noticeably larger impact, which may be explained by…

Implications

The findings having noteworthy implications for British low-cost online equity brokers. Specifically:

The large impact of Factors X and Y implies that brokers need to consider….

The limited impact of Factor E implies that brokers need to…

As you can see, the conclusion chapter is basically explaining the “what” (what your study found) and the “so what?” (what the findings mean for the industry or research). This brings the study full circle and closes off the document.

Let’s recap – how to write a dissertation or thesis

You’re still with me? Impressive! I know that this post was a long one, but hopefully you’ve learnt a thing or two about how to write a dissertation or thesis, and are now better equipped to start your own research.

To recap, the 8 steps to writing a quality dissertation (or thesis) are as follows:

- Understand what a dissertation (or thesis) is – a research project that follows the research process.

- Find a unique (original) and important research topic

- Craft a convincing dissertation or thesis research proposal

- Write a clear, compelling introduction chapter

- Undertake a thorough review of the existing research and write up a literature review

- Undertake your own research

- Present and interpret your findings

Once you’ve wrapped up the core chapters, all that’s typically left is the abstract , reference list and appendices. As always, be sure to check with your university if they have any additional requirements in terms of structure or content.

Psst... there’s more!

This post was based on one of our popular Research Bootcamps . If you're working on a research project, you'll definitely want to check this out ...

20 Comments

thankfull >>>this is very useful

Thank you, it was really helpful

unquestionably, this amazing simplified way of teaching. Really , I couldn’t find in the literature words that fully explicit my great thanks to you. However, I could only say thanks a-lot.

Great to hear that – thanks for the feedback. Good luck writing your dissertation/thesis.

This is the most comprehensive explanation of how to write a dissertation. Many thanks for sharing it free of charge.

Very rich presentation. Thank you

Thanks Derek Jansen|GRADCOACH, I find it very useful guide to arrange my activities and proceed to research!

Thank you so much for such a marvelous teaching .I am so convinced that am going to write a comprehensive and a distinct masters dissertation

It is an amazing comprehensive explanation

This was straightforward. Thank you!

I can say that your explanations are simple and enlightening – understanding what you have done here is easy for me. Could you write more about the different types of research methods specific to the three methodologies: quan, qual and MM. I look forward to interacting with this website more in the future.

Thanks for the feedback and suggestions 🙂

Hello, your write ups is quite educative. However, l have challenges in going about my research questions which is below; *Building the enablers of organisational growth through effective governance and purposeful leadership.*

Very educating.

Just listening to the name of the dissertation makes the student nervous. As writing a top-quality dissertation is a difficult task as it is a lengthy topic, requires a lot of research and understanding and is usually around 10,000 to 15000 words. Sometimes due to studies, unbalanced workload or lack of research and writing skill students look for dissertation submission from professional writers.

Thank you 💕😊 very much. I was confused but your comprehensive explanation has cleared my doubts of ever presenting a good thesis. Thank you.

thank you so much, that was so useful

Hi. Where is the excel spread sheet ark?

could you please help me look at your thesis paper to enable me to do the portion that has to do with the specification

my topic is “the impact of domestic revenue mobilization.

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

Dissertation Strategies

What this handout is about.

This handout suggests strategies for developing healthy writing habits during your dissertation journey. These habits can help you maintain your writing momentum, overcome anxiety and procrastination, and foster wellbeing during one of the most challenging times in graduate school.

Tackling a giant project

Because dissertations are, of course, big projects, it’s no surprise that planning, writing, and revising one can pose some challenges! It can help to think of your dissertation as an expanded version of a long essay: at the end of the day, it is simply another piece of writing. You’ve written your way this far into your degree, so you’ve got the skills! You’ll develop a great deal of expertise on your topic, but you may still be a novice with this genre and writing at this length. Remember to give yourself some grace throughout the project. As you begin, it’s helpful to consider two overarching strategies throughout the process.

First, take stock of how you learn and your own writing processes. What strategies have worked and have not worked for you? Why? What kind of learner and writer are you? Capitalize on what’s working and experiment with new strategies when something’s not working. Keep in mind that trying out new strategies can take some trial-and-error, and it’s okay if a new strategy that you try doesn’t work for you. Consider why it may not have been the best for you, and use that reflection to consider other strategies that might be helpful to you.

Second, break the project into manageable chunks. At every stage of the process, try to identify specific tasks, set small, feasible goals, and have clear, concrete strategies for achieving each goal. Small victories can help you establish and maintain the momentum you need to keep yourself going.

Below, we discuss some possible strategies to keep you moving forward in the dissertation process.

Pre-dissertation planning strategies

Get familiar with the Graduate School’s Thesis and Dissertation Resources .

Create a template that’s properly formatted. The Grad School offers workshops on formatting in Word for PC and formatting in Word for Mac . There are online templates for LaTeX users, but if you use a template, save your work where you can recover it if the template has corrruption issues.

Learn how to use a citation-manager and a synthesis matrix to keep track of all of your source information.

Skim other dissertations from your department, program, and advisor. Enlist the help of a librarian or ask your advisor for a list of recent graduates whose work you can look up. Seeing what other people have done to earn their PhD can make the project much less abstract and daunting. A concrete sense of expectations will help you envision and plan. When you know what you’ll be doing, try to find a dissertation from your department that is similar enough that you can use it as a reference model when you run into concerns about formatting, structure, level of detail, etc.

Think carefully about your committee . Ideally, you’ll be able to select a group of people who work well with you and with each other. Consult with your advisor about who might be good collaborators for your project and who might not be the best fit. Consider what classes you’ve taken and how you “vibe” with those professors or those you’ve met outside of class. Try to learn what you can about how they’ve worked with other students. Ask about feedback style, turnaround time, level of involvement, etc., and imagine how that would work for you.

Sketch out a sensible drafting order for your project. Be open to writing chapters in “the wrong order” if it makes sense to start somewhere other than the beginning. You could begin with the section that seems easiest for you to write to gain momentum.

Design a productivity alliance with your advisor . Talk with them about potential projects and a reasonable timeline. Discuss how you’ll work together to keep your work moving forward. You might discuss having a standing meeting to discuss ideas or drafts or issues (bi-weekly? monthly?), your advisor’s preferences for drafts (rough? polished?), your preferences for what you’d like feedback on (early or late drafts?), reasonable turnaround time for feedback (a week? two?), and anything else you can think of to enter the collaboration mindfully.

Design a productivity alliance with your colleagues . Dissertation writing can be lonely, but writing with friends, meeting for updates over your beverage of choice, and scheduling non-working social times can help you maintain healthy energy. See our tips on accountability strategies for ideas to support each other.

Productivity strategies

Write when you’re most productive. When do you have the most energy? Focus? Creativity? When are you most able to concentrate, either because of your body rhythms or because there are fewer demands on your time? Once you determine the hours that are most productive for you (you may need to experiment at first), try to schedule those hours for dissertation work. See the collection of time management tools and planning calendars on the Learning Center’s Tips & Tools page to help you think through the possibilities. If at all possible, plan your work schedule, errands and chores so that you reserve your productive hours for the dissertation.

Put your writing time firmly on your calendar . Guard your writing time diligently. You’ll probably be invited to do other things during your productive writing times, but do your absolute best to say no and to offer alternatives. No one would hold it against you if you said no because you’re teaching a class at that time—and you wouldn’t feel guilty about saying no. Cultivating the same hard, guilt-free boundaries around your writing time will allow you preserve the time you need to get this thing done!

Develop habits that foster balance . You’ll have to work very hard to get this dissertation finished, but you can do that without sacrificing your physical, mental, and emotional wellbeing. Think about how you can structure your work hours most efficiently so that you have time for a healthy non-work life. It can be something as small as limiting the time you spend chatting with fellow students to a few minutes instead of treating the office or lab as a space for extensive socializing. Also see above for protecting your time.

Write in spaces where you can be productive. Figure out where you work well and plan to be there during your dissertation work hours. Do you get more done on campus or at home? Do you prefer quiet and solitude, like in a library carrel? Do you prefer the buzz of background noise, like in a coffee shop? Are you aware of the UNC Libraries’ list of places to study ? If you get “stuck,” don’t be afraid to try a change of scenery. The variety may be just enough to get your brain going again.

Work where you feel comfortable . Wherever you work, make sure you have whatever lighting, furniture, and accessories you need to keep your posture and health in good order. The University Health and Safety office offers guidelines for healthy computer work . You’re more likely to spend time working in a space that doesn’t physically hurt you. Also consider how you could make your work space as inviting as possible. Some people find that it helps to have pictures of family and friends on their desk—sort of a silent “cheering section.” Some people work well with neutral colors around them, and others prefer bright colors that perk up the space. Some people like to put inspirational quotations in their workspace or encouraging notes from friends and family. You might try reconfiguring your work space to find a décor that helps you be productive.

Elicit helpful feedback from various people at various stages . You might be tempted to keep your writing to yourself until you think it’s brilliant, but you can lower the stakes tremendously if you make eliciting feedback a regular part of your writing process. Your friends can feel like a safer audience for ideas or drafts in their early stages. Someone outside your department may provide interesting perspectives from their discipline that spark your own thinking. See this handout on getting feedback for productive moments for feedback, the value of different kinds of feedback providers, and strategies for eliciting what’s most helpful to you. Make this a recurring part of your writing process. Schedule it to help you hit deadlines.

Change the writing task . When you don’t feel like writing, you can do something different or you can do something differently. Make a list of all the little things you need to do for a given section of the dissertation, no matter how small. Choose a task based on your energy level. Work on Grad School requirements: reformat margins, work on bibliography, and all that. Work on your acknowledgements. Remember all the people who have helped you and the great ideas they’ve helped you develop. You may feel more like working afterward. Write a part of your dissertation as a letter or email to a good friend who would care. Sometimes setting aside the academic prose and just writing it to a buddy can be liberating and help you get the ideas out there. You can make it sound smart later. Free-write about why you’re stuck, and perhaps even about how sick and tired you are of your dissertation/advisor/committee/etc. Venting can sometimes get you past the emotions of writer’s block and move you toward creative solutions. Open a separate document and write your thoughts on various things you’ve read. These may or may note be coherent, connected ideas, and they may or may not make it into your dissertation. They’re just notes that allow you to think things through and/or note what you want to revisit later, so it’s perfectly fine to have mistakes, weird organization, etc. Just let your mind wander on paper.

Develop habits that foster productivity and may help you develop a productive writing model for post-dissertation writing . Since dissertations are very long projects, cultivating habits that will help support your work is important. You might check out Helen Sword’s work on behavioral, artisanal, social, and emotional habits to help you get a sense of where you are in your current habits. You might try developing “rituals” of work that could help you get more done. Lighting incense, brewing a pot of a particular kind of tea, pulling out a favorite pen, and other ritualistic behaviors can signal your brain that “it is time to get down to business.” You can critically think about your work methods—not only about what you like to do, but also what actually helps you be productive. You may LOVE to listen to your favorite band while you write, for example, but if you wind up playing air guitar half the time instead of writing, it isn’t a habit worth keeping.

The point is, figure out what works for you and try to do it consistently. Your productive habits will reinforce themselves over time. If you find yourself in a situation, however, that doesn’t match your preferences, don’t let it stop you from working on your dissertation. Try to be flexible and open to experimenting. You might find some new favorites!

Motivational strategies

Schedule a regular activity with other people that involves your dissertation. Set up a coworking date with your accountability buddies so you can sit and write together. Organize a chapter swap. Make regular appointments with your advisor. Whatever you do, make sure it’s something that you’ll feel good about showing up for–and will make you feel good about showing up for others.

Try writing in sprints . Many writers have discovered that the “Pomodoro technique” (writing for 25 minutes and taking a 5 minute break) boosts their productivity by helping them set small writing goals, focus intently for short periods, and give their brains frequent rests. See how one dissertation writer describes it in this blog post on the Pomodoro technique .

Quit while you’re ahead . Sometimes it helps to stop for the day when you’re on a roll. If you’ve got a great idea that you’re developing and you know where you want to go next, write “Next, I want to introduce x, y, and z and explain how they’re related—they all have the same characteristics of 1 and 2, and that clinches my theory of Q.” Then save the file and turn off the computer, or put down the notepad. When you come back tomorrow, you will already know what to say next–and all that will be left is to say it. Hopefully, the momentum will carry you forward.

Write your dissertation in single-space . When you need a boost, double space it and be impressed with how many pages you’ve written.

Set feasible goals–and celebrate the achievements! Setting and achieving smaller, more reasonable goals ( SMART goals ) gives you success, and that success can motivate you to focus on the next small step…and the next one.

Give yourself rewards along the way . When you meet a writing goal, reward yourself with something you normally wouldn’t have or do–this can be anything that will make you feel good about your accomplishment.

Make the act of writing be its own reward . For example, if you love a particular coffee drink from your favorite shop, save it as a special drink to enjoy during your writing time.

Try giving yourself “pre-wards” —positive experiences that help you feel refreshed and recharged for the next time you write. You don’t have to “earn” these with prior work, but you do have to commit to doing the work afterward.

Commit to doing something you don’t want to do if you don’t achieve your goal. Some people find themselves motivated to work harder when there’s a negative incentive. What would you most like to avoid? Watching a movie you hate? Donating to a cause you don’t support? Whatever it is, how can you ensure enforcement? Who can help you stay accountable?

Affective strategies

Build your confidence . It is not uncommon to feel “imposter phenomenon” during the course of writing your dissertation. If you start to feel this way, it can help to take a few minutes to remember every success you’ve had along the way. You’ve earned your place, and people have confidence in you for good reasons. It’s also helpful to remember that every one of the brilliant people around you is experiencing the same lack of confidence because you’re all in a new context with new tasks and new expectations. You’re not supposed to have it all figured out. You’re supposed to have uncertainties and questions and things to learn. Remember that they wouldn’t have accepted you to the program if they weren’t confident that you’d succeed. See our self-scripting handout for strategies to turn these affirmations into a self-script that you repeat whenever you’re experiencing doubts or other negative thoughts. You can do it!

Appreciate your successes . Not meeting a goal isn’t a failure–and it certainly doesn’t make you a failure. It’s an opportunity to figure out why you didn’t meet the goal. It might simply be that the goal wasn’t achievable in the first place. See the SMART goal handout and think through what you can adjust. Even if you meant to write 1500 words, focus on the success of writing 250 or 500 words that you didn’t have before.

Remember your “why.” There are a whole host of reasons why someone might decide to pursue a PhD, both personally and professionally. Reflecting on what is motivating to you can rekindle your sense of purpose and direction.

Get outside support . Sometimes it can be really helpful to get an outside perspective on your work and anxieties as a way of grounding yourself. Participating in groups like the Dissertation Support group through CAPS and the Dissertation Boot Camp can help you see that you’re not alone in the challenges. You might also choose to form your own writing support group with colleagues inside or outside your department.

Understand and manage your procrastination . When you’re writing a long dissertation, it can be easy to procrastinate! For instance, you might put off writing because the house “isn’t clean enough” or because you’re not in the right “space” (mentally or physically) to write, so you put off writing until the house is cleaned and everything is in its right place. You may have other ways of procrastinating. It can be helpful to be self-aware of when you’re procrastinating and to consider why you are procrastinating. It may be that you’re anxious about writing the perfect draft, for example, in which case you might consider: how can I focus on writing something that just makes progress as opposed to being “perfect”? There are lots of different ways of managing procrastination; one way is to make a schedule of all the things you already have to do (when you absolutely can’t write) to help you visualize those chunks of time when you can. See this handout on procrastination for more strategies and tools for managing procrastination.

Your topic, your advisor, and your committee: Making them work for you

By the time you’ve reached this stage, you have probably already defended a dissertation proposal, chosen an advisor, and begun working with a committee. Sometimes, however, those three elements can prove to be major external sources of frustration. So how can you manage them to help yourself be as productive as possible?

Managing your topic

Remember that your topic is not carved in stone . The research and writing plan suggested in your dissertation proposal was your best vision of the project at that time, but topics evolve as the research and writing progress. You might need to tweak your research question a bit to reduce or adjust the scope, you might pare down certain parts of the project or add others. You can discuss your thoughts on these adjustments with your advisor at your check ins.

Think about variables that could be cut down and how changes would affect the length, depth, breadth, and scholarly value of your study. Could you cut one or two experiments, case studies, regions, years, theorists, or chapters and still make a valuable contribution or, even more simply, just finish?

Talk to your advisor about any changes you might make . They may be quite sympathetic to your desire to shorten an unwieldy project and may offer suggestions.

Look at other dissertations from your department to get a sense of what the chapters should look like. Reverse-outline a few chapters so you can see if there’s a pattern of typical components and how information is sequenced. These can serve as models for your own dissertation. See this video on reverse outlining to see the technique.

Managing your advisor

Embrace your evolving status . At this stage in your graduate career, you should expect to assume some independence. By the time you finish your project, you will know more about your subject than your committee does. The student/teacher relationship you have with your advisor will necessarily change as you take this big step toward becoming their colleague.

Revisit the alliance . If the interaction with your advisor isn’t matching the original agreement or the original plan isn’t working as well as it could, schedule a conversation to revisit and redesign your working relationship in a way that could work for both of you.

Be specific in your feedback requests . Tell your advisor what kind of feedback would be most helpful to you. Sometimes an advisor can be giving unhelpful or discouraging feedback without realizing it. They might make extensive sentence-level edits when you really need conceptual feedback, or vice-versa, if you only ask generally for feedback. Letting your advisor know, very specifically, what kinds of responses will be helpful to you at different stages of the writing process can help your advisor know how to help you.

Don’t hide . Advisors can be most helpful if they know what you are working on, what problems you are experiencing, and what progress you have made. If you haven’t made the progress you were hoping for, it only makes it worse if you avoid talking to them. You rob yourself of their expertise and support, and you might start a spiral of guilt, shame, and avoidance. Even if it’s difficult, it may be better to be candid about your struggles.

Talk to other students who have the same advisor . You may find that they have developed strategies for working with your advisor that could help you communicate more effectively with them.

If you have recurring problems communicating with your advisor , you can make a change. You could change advisors completely, but a less dramatic option might be to find another committee member who might be willing to serve as a “secondary advisor” and give you the kinds of feedback and support that you may need.

Managing your committee

Design the alliance . Talk with your committee members about how much they’d like to be involved in your writing process, whether they’d like to see chapter drafts or the complete draft, how frequently they’d like to meet (or not), etc. Your advisor can guide you on how committees usually work, but think carefully about how you’d like the relationship to function too.

Keep in regular contact with your committee , even if they don’t want to see your work until it has been approved by your advisor. Let them know about fellowships you receive, fruitful research excursions, the directions your thinking is taking, and the plans you have for completion. In short, keep them aware that you are working hard and making progress. Also, look for other ways to get facetime with your committee even if it’s not a one-on-one meeting. Things like speaking with them at department events, going to colloquiums or other events they organize and/or attend regularly can help you develop a relationship that could lead to other introductions and collaborations as your career progresses.

Share your struggles . Too often, we only talk to our professors when we’re making progress and hide from them the rest of the time. If you share your frustrations or setbacks with a knowledgeable committee member, they might offer some very helpful suggestions for overcoming the obstacles you face—after all, your committee members have all written major research projects before, and they have probably solved similar problems in their own work.

Stay true to yourself . Sometimes, you just don’t entirely gel with your committee, but that’s okay. It’s important not to get too hung up on how your committee does (or doesn’t) relate to you. Keep your eye on the finish line and keep moving forward.

Helpful websites:

Graduate School Diversity Initiatives : Groups and events to support the success of students identifying with an affinity group.

Graduate School Career Well : Extensive professional development resources related to writing, research, networking, job search, etc.

CAPS Therapy Groups : CAPS offers a variety of support groups, including a dissertation support group.

Advice on Research and Writing : Lots of links on writing, public speaking, dissertation management, burnout, and more.

How to be a Good Graduate Student: Marie DesJardins’ essay talks about several phases of the graduate experience, including the dissertation. She discusses some helpful hints for staying motivated and doing consistent work.

Preparing Future Faculty : This page, a joint project of the American Association of Colleges and Universities, the Council of Graduate Schools, and the Pew Charitable Trusts, explains the Preparing Future Faculty Programs and includes links and suggestions that may help graduate students and their advisors think constructively about the process of graduate education as a step toward faculty responsibilities.

Dissertation Tips : Kjell Erik Rudestam, Ph.D. and Rae Newton, Ph.D., authors of Surviving Your Dissertation: A Comprehensive Guide to Content and Process.

The ABD Survival Guide Newsletter : Information about the ABD Survival Guide newsletter (which is free) and other services from E-Coach (many of which are not free).

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout and attribute the source: The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Make a Gift

Creative & Critical Writing MA: Dissertation Project

- Creative and Critical Writing Workshops

- Writing Historical Fiction

- Children’s Literature: Through the Looking Glass

- Writers in Residence

- Adaptation: New Creative/Critical Directions

- Dissertation Project

- Databases and Journals

- Books and e-books

- Using Images, Media and Specialist Websites

- Latest Library News

Welcome to your Dissertation Project reading list. Here you will find the resources to support you throughout this module.

Recommended reading.

- << Previous: Adaptation: New Creative/Critical Directions

- Next: Subject Guides >>

- Last Updated: Jun 3, 2024 12:47 PM

- URL: https://libguides.uos.ac.uk/CreativeWriting

➔ About the Library

➔ Meet the Team

➔ Customer Service Charter

➔ Library Policies & Regulations

➔ Privacy & Data Protection

Essential Links

➔ A-Z of eResources

➔ Frequently Asked Questions

➔Discover the Library

➔Referencing Help

➔ Print & Copy Services

➔ Service Updates

Library & Learning Services, University of Suffolk, Library Building, Long Street, Ipswich, IP4 1QJ

✉ Email Us: [email protected]

✆ Call Us: +44 (0)1473 3 38700

The Gale Review

A blog from Gale International

My Top 10 Tips to Ace Your Dissertation

│By Emily Priest, Gale Ambassador at the University of Portsmouth│

Being a student and working from home in the middle of a pandemic can be hard, and it can be even harder when you have your final dissertation looming. But, despite how challenging things seem, there are a few key things you can do to ease your anxiety and make your work dazzle! Here are ten of my top tips for writing your dissertation whilst studying from home during the pandemic. Tweet us @GaleAmbassadors if they work for you – and share if you have any special dissertation or essay-writing tricks of your own!

1. Do the worst first – get your citation process sorted!

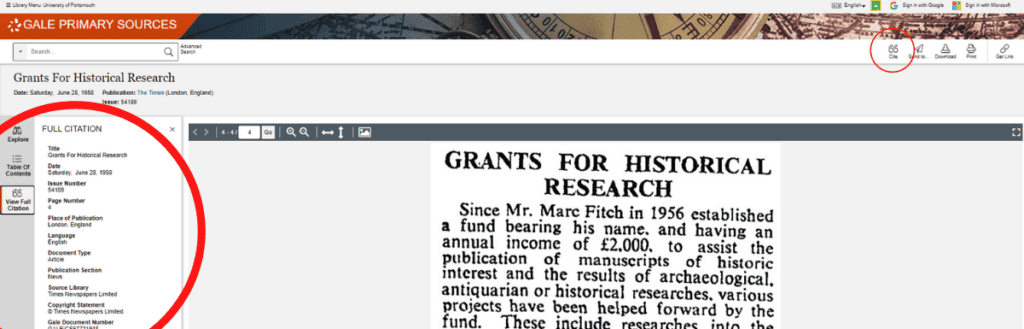

My first and favourite tip for dissertation and essay writing is to get your citations and sources sorted first. I know what you’re thinking – “ But I hate doing the citations!” – and that is exactly why you should do them first! There is nothing worse than working hard on an essay, finishing it, and then realising you have to spend hours re-finding each source to get hold of the citation, before formatting them in the required way. If you make a separate document, or list, before you start, and update it with your citations as you go along, you will feel a lot better as you go along, and be in a better position when you’ve finished writing. And, when you get around to doing your bibliography, it’ll be no sweat! It’s all there, ready to be tweaked, copy and pasted into your final document. Don’t forget too that some research platforms such as Gale Primary Sources generate citations for you, and provide many different formats!

2. Research and plan thoroughly – don’t start writing straight away.

It may be tempting to start writing straight away – but resist the urge! Start with research, followed by thorough planning. If you begin writing before finishing (or even starting!) your research, you may find that you used valuable time writing something that isn’t relevant, or that your research is taking you in a completely different direction. Reading, reading a bit more, followed by some more reading may seem tedious, but it will give you more ideas, greater focus and encourage high-quality, consistent writing when you do get to that stage. And if your initial reading is starting to get tedious, mix it up with early-stage planning. Write down key topics or structural points and make visual maps and tables. Creating tools and recording your thoughts in this way, will, in the end, help you write with greater clarity, shaping your dissertation into a high-grade piece.

3. Break it down – structuring yourself like a pro.

If you’re like me, you may find essays overwhelming and, in your head, build them up into mammoth tasks. What you can do to help is to divide the dissertation up into smaller tasks. For example, finding sources is a task for one day, writing up citations is for another day and writing the introduction is for the day after that. You can divide up your dissertation into as big or as little chunks as you want, right down to each paragraph or section, and then write up a list of tasks that you need to do at each stage. If you need help doing this, consider online planners and guides which help provide this structure such as MyStudyLife or GetRevising . If you incorporate this step into your planning stage, and organise your time straight away, you will be in a better position, both mentally and timewise, to shoot for those higher grades.

4. Mini deadlines – better for you than you may think.

Another way you can create organisation and structure for yourself is by setting mini deadlines: rather than focusing on one final deadline, break your dissertation down into tasks and set mini deadlines for each task. I also like to set myself a deadline for a final draft a week before the actual deadline. This way I have at least a week for any last-minute problems or editing. Leaving it until the last minute is never ideal, so creating mini deadlines for planning, writing and editing is a great way to motivate and organise yourself and stay ahead of the game.

5. Appearances aren’t everything…but they do help!

A dissertation is a special piece of a work and you should take pride in that. Whilst appearances are not as important as your research and arguments, they do help add a flare of professionalism which can score you a few extra points! Now, I’m not talking about emojis or sparkles but paying close attention to the formatting required in the type of piece you’re writing. (If you’re writing a report with data findings it will look very different to a creative writing dissertation, so keep in mind what different features you may need such as tables, headings or content pages.) Ensure your formatting is consistent, relevant and well-crafted and at the very least, give it a flashy front cover! This is your big dissertation, after all! It deserves to be treated with pride! Adding those little touches demonstrates this pride in your work, and undoubtedly your skill and academic growth will shine through to your lecturers.

6. Don’t go word blind – why taking breaks is important.

Have you ever written a piece of university work, submitted it, and then found out there was a typo that you swore wasn’t there before? That’s word blindness and it happens to the best of us. To ensure you’re reading what you’ve actually written, don’t edit straight after writing. Your brain remembers what you intended to write and projects that onto what you’re reading so it’s really easy to skim over a spelling mistake or other error. Half an hour or more outside, doing a hobby, thinking about something else, will reset your brain and make it ready to skim your work for mistakes. I personally recommend only returning to edit after a good night’s rest!

7. Locked in? Get your study space right.

With many of us working from home, trying to focus and find the motivation has become particularly challenging. There are so many indoor distractions and sitting in your bedroom isn’t quite as motivating as a seminar classroom or university library. To help, be as strict as possible with yourself; make a study space with no distractions – that includes no phones – and consider restricting your access to social media on your laptop or desktop. My “Surviving Lockdown” blog post, which you can read here , has many other tips on how to remove distractions. And if you’re a phone-a-holic consider a timed phone safe – yes, really, they exist !

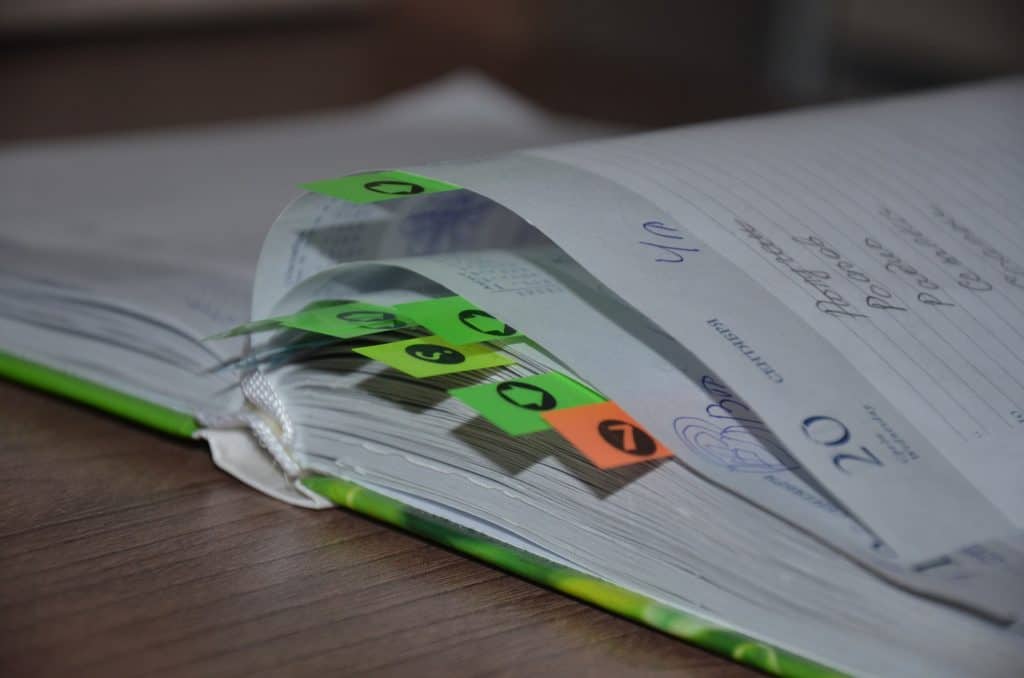

8. Get arty with editing – use colour coding.

If you’re not editing your work with colour-coded highlighters, you’re missing out! Seriously, this is a process that I found particularly useful. Editing can be one of the hardest stages of writing a dissertation and can easily feel overwhelming if you aren’t being smart with your tools. I recommend taking at least four coloured pens or highlighters and marking citations with one colour, every paraphrase or direct quote with another, then spelling mistakes and other word that need changing such as clunky verbs or first-person pronouns. Break apart each sentence slowly and carefully, highlighting each component at a time, being sure not to rush over any sentences. When you’re finished your dissertation will look a bit messy but you will be able to easily see which components need changing, and where some areas are lacking citations – or are too quote-heavy.

9. You don’t have to do this alone – building a support network.

If you are a distanced learner like me, you may feel the isolation settling in, breeding nasty thoughts and anxieties like, “ this isn’t any good ”, “ I don’t know what I’m doing ” or “ I’m going to fail” . If you’re not regularly talking to lecturers or university friends, you’re not getting the support and feedback you need. This isn’t good for your wellbeing. Consider building a support network around yourself, made up of lecturers, university support services, friends, family or online groups. Reach out to people and ask for help – they’ll always be someone willing to offer support. Whilst it may seem that no one cares and lecturers are too busy, if you drop any one of these people a message and let them know how you’re feeling, you’ll find you’re not as alone as you thought. Reach out, accept help when it presents itself and if you are struggling, there’s no pride lost in admitting that and getting help. We all need it.

10. Keepin’ it fresh – make your research varied.

My final tip is to keep your research fresh and diverse. A good dissertation writer incorporates many document types into their research, from primary sources to journal articles and practitioner reports. If relevant, try to use different types of information from credible sites and mix up your searching. Perhaps you normally search for reading on Google Scholar, why not have another look at what’s available through your university library’s discovery service? Gale Primary Sources , one of the great research databases available through your university library, has a wealth of information for dissertations on all manner of topics. If your current sources are a bit journal-heavy, what newspaper articles can you incorporate, to add a new dimension to your work? Explore all the archives, sites and databases at your fingertips and don’t forget to ask your tutor, other lecturers, peers or university librarians for the sources they recommend.

Want more help with your dissertation and need more tricks and tips? Why not read How Gale Primary Sources Helped Me with My Dissertation – and Can Help You Too! and How to Handle Primary Source Archives – University Lecturer’s Top Tips .

Blog post cover image citation: Image from Ketut Subiyanto on Pexels.com – https://www.pexels.com/photo/student-with-documents-and-laptop-happy-about-getting-into-university-4560083/

About the Author

I’m currently a Marketing Executive in the Gale International Strategic Marketing team. I love the combination of creativity, strategic thinking and project management required in this busy role. Having studied History and English at Durham, it’s a great pleasure to work for a company producing historical archives and literary materials – meandering through Gale’s abundant resources never really feels like work! And to pad out this depiction of me, I can frequently be found running through the Hampshire countryside, and have a strong partiality for coffee cake.

Home · Article · 20 Tips to help you finish your dissertation

20 Tips to help you finish your dissertation

i haven’t met many ph.d. students who don’t like to write. some may like writing more than others, but most enjoy writing—or, at least, the satisfaction of having written. wherever you find yourself on the love-for-writing spectrum, a dissertation awaits completion, and you must finish. here are a few tips to help you. 1. write sooner. the….

I haven’t met many Ph.D. students who don’t like to write. Some may like writing more than others, but most enjoy writing—or, at least, the satisfaction of having written. Wherever you find yourself on the love-for-writing spectrum, a dissertation awaits completion, and you must finish. Here are a few tips to help you.

1. Write sooner. The dissertation writing process can quickly become paralyzing because of its size and importance. It is a project that will be reviewed rigorously by your advisor and your committee, and your graduation depends on your successful completion and defense. Facing these realities can be daunting and tempt you to wait until you can determine that you’ve researched or thought enough about the topic. Yet, the longer you delay writing, the more difficult it will be to actually start the process. The answer to your paralysis is to start writing . Are you unsure of your argument or not fully convinced you have done the requisite research? You may be right: your argument may not be airtight, and you may need to do more reading; but you will be able to determine to what degree these problems need attention when you start writing. Productivity begets productivity, and you will be amazed at how arguments take shape and the direction of your research is forged as you write.

2. Write continually. So, don’t stop writing. Of course, you need to continue to read and study and take notes—I will talk about this more in a moment—but it is best if you keep the gears from grinding to a halt. Keep your mind working and your project moving. Your assignment is not to turn in a hundred pages of notes to your supervisor—you must produce a dissertation with complete sentences and paragraphs and chapters. Keep writing.

3. Write in order to rewrite. Writing sooner and writing continually can only happen if you aren’t consumed with perfection. Some of us are discouraged from writing because we think our first draft needs to be our final draft. But this is exactly the problem. Get your thoughts on paper and plan to go back and fix awkward sentences, poor word choices, and illogical or unsubstantiated arguments in your subsequent drafts. Knowing that rewriting is part of the writing process will free you to write persistently, make progress, and look forward to fixing things later.

4. Spend adequate time determining your thesis and methodology. This probably could fit in the number one slot, but I wanted to emphasize the importance writing right away. Besides, you might find that you modify your thesis and methodology slightly as you write and make progress in developing your overall argument. Nevertheless, the adage is true: form a solid thesis and methodology statement and your dissertation will “write itself.” Plan to spend some time writing and rewriting and rewriting (again) your thesis and methodology statements so that you will know where you are going and where you need to go.

5. If you get stuck, move to another section. Developing a clear thesis and methodology will allow you to move around in your dissertation when you get stuck. Granted, we should not make a habit of avoiding difficult tasks, but there are times when it will be a more effective use of time to move to sections that will write easy. As you continue to make progress in your project and get words on paper, you will also help mitigate the panic that so often looms over your project when you get stuck and your writing ceases.

6. Fight the urge to walk away from writing when it gets difficult. Having encouraged you to move to another section when you get stuck, it is also important to add a balancing comment to encourage you to fight through the tough spots in your project. I don’t mean that you should force writing when it is clear that you may need to make some structural changes or do a little more research on a given topic. But if you find yourself dreading a particular portion of your dissertation because it will require some mind-numbing, head-on-your-desk, prayer-producing rigor, then my advice is to face these tough sections head on and sit in your chair until you make some progress. You will be amazed at how momentum will grow out of your dogged persistence to hammer out these difficult portions of your project.

7. Strive for excellence but remember that this is not your magnum opus. A dissertation needs to be of publishable quality and it will need to past the muster of your supervisor and committee. But it is also a graduation requirement. Do the research. Make a contribution. Finish the project. And plan to write your five-volume theology when you have 30-40 more years of study, reflection, and teaching under your belt.

8. Take careful notes. Taking careful notes is essential for two reasons. First, keeping a meticulous record of the knowledge you glean from your research will save you time: there will be no need to later revisit your resources and chase bibliographic information, and you will find yourself less prone to the dreaded, “Where did I read that?” Second, and most importantly, you will avoid plagiarism. If you fail to take good notes and are not careful to accurately copy direct quotes and make proper citations, you will be liable to reproducing material in your dissertation that is not original with you. Pleading that your plagiarism was inadvertent will not help your cause. It is your responsibility to take careful notes and attribute all credit to whom it is due through proper citation.

9. Know when to read. Write sooner, write continually, and write in order to rewrite. But you need to know when you are churning an empty barrel. Reading and research should be a stimulus to write and you need to know when that stimulus is needed. Be willing to stop writing for a short period so that you can refresh your mind with new ideas and research.

10. Establish chunks of time to research and write. While it is important to keep writing and make the most of the time that you have, it is best for writing projects specifically to set aside large portions of time with which to write. Writing requires momentum, and momentum gathers over time. Personally, I have found that I need at least an hour to get things rolling, and that three to four hours is ideal.

Related: Learn more about our Research Doctoral Studies Degrees ( D.Miss., Ed.D., Th.M., Ph.D). See also the Doctoral Studies viewbook .

11. Get exercise, adequate sleep, and eat well. Because our minds and bodies are meant to function in harmony, you will probably find that your productivity suffers to the degree that you are not giving attention to your exercise, sleep, and eating habits. Like it or not, our ability to maintain long periods of sustained concentration, think carefully over our subject matter, and find motivation to complete tasks is dependent in a significant sense upon how we are caring for our bodies. When we neglect exercise, fail to get adequate sleep, or constantly indulge in an unhealthy diet, we will find it increasingly difficult to muster the energy and clarity with which to complete our dissertation.

12. Stay on task. Completing a dissertation, in large measure, is not so much a feat of the intellect as it is the result of discipline. If you are able to set aside large chunks of time with which to research and write, make sure that you are not using that time for other tasks. This means that you must strive against multi-tasking. In truth, studies have shown that multi-tasking is a cognitive impossibility. Our brains can only concentrate on one thing at a time. When we think we are multitasking we are actually “switch-tasking;” rather than doing several things at once, our brains are constantly toggling from one task to the other (listening to a song on the radio to reading a book, back to the song, etc.). You will be amazed at how much you can accomplish if you give an undistracted 60-90 minutes to something. Stay on task.

13. Don’t get stuck on introductions. This is a basic writing principle, but one that bears repeating here: write the body of a given chapter or section and then return to the introductions. It is usually easier to introduce something that you have already written for the simple fact that you now know what you are introducing. You might be tempted to write the introduction first and labor to capture your reader with a gripping illustration or perfect quote while refusing to enter into the body of your paper until your preliminary remarks are flawless. This is a sure recipe for frustration. Wait until you have completed a particular section or chapter’s content until you write introductions. This practice will save you time and loads of trouble.

14. Use a legal pad. There’s nothing magic about a legal pad; my only aim here is to encourage you to push back from the keyboard occasionally and stimulate your mind by sketching your argument and writing your ideas by hand. I have found my way out of many dry spells by closing the laptop for a few minutes and writing on a piece of paper. I might bullet point a few key ideas, diagram my chapter outlines, or sketch the entire dissertation with boxes and arrows and notes scribbled over several pages.

15. Go on walks. It has been said recently that walking promotes creativity . I agree. Whether you like to walk among the trees or besides the small coffee shops along quaint side streets, I recommend that you go on walks and think specifically about your dissertation. You might find that the change of scenery, the stimulus of a bustling community, or the refreshing quiet of a park trail is just the help you need.

16. Make use of a capture journal. In order to make the most of your walks, you will need a place to “capture” your ideas. You may prefer to use the voice memo or notepad feature on your smartphone, or, if you’re like me, a small 2.5”x4” lined journal . Whatever your preference, find a method that allows you to store your ideas as they come to you during your walks or as you fall to sleep at night. I wonder how many useful ideas many of us have lost because we failed to write them down? Don’t let this happen to you. Resolve to be a good steward of your thinking time and seize those thoughts.

17. Talk about your ideas with others. When you are writing your dissertation, you might be tempted to lock away your ideas and avoid discussing them with others. This is unwise. Talking with others about your ideas helps you to refine and stimulate your thinking; it also creates opportunities for you to learn of important resources and how your contribution will affect other branches of scholarship. Also, as people ask questions about your project, you will begin to see where your argument is unclear or unsubstantiated.

18. Learn how to read. Writing a dissertation requires a massive amount of reading. You must become familiar with the arguments of several hundred resources—books, articles, reviews, and other dissertations. What will you do? You must learn how to read. Effective reading does not require that you read every book word-for-word, cover-to-cover. Indeed, sometimes very close reading of a given volume may actually impede your understanding of the author’s argument. In order to save time and cultivate a more effective approach to knowledge acquisition, you must learn how to use your resources. This means knowing when to read a book or article closely, and knowing when to skim. It means knowing how to read large books within a matter of an hour by carefully reviewing the table of contents, reading and rereading key chapters and paragraphs, and using the subject index. If you want to finish your dissertation, learn how to read.

19. Set deadlines. Depending on your project, you may have built in deadlines that force you to produce material at a steady clip. If you do not have built in deadlines, you must impose them on yourself. Deadlines produce results, and results lead to completed writing projects. Set realistic deadlines and stick to them. You will find that you are able to accomplish much more than you anticipated if you set and stick to deadlines.

20. Take productive breaks. Instead of turning to aimless entertainment to fill your break times, try doing something that will indirectly serve your writing process. We need breaks: they refresh us and help us stay on task. In fact, studies have shown that overall productivity diminishes if employees are not allowed to take regular, brief pauses from their work during the day. What is not often mentioned, however, is that a break does not necessarily have to be unrelated to our work in order to be refreshing; it needs only to be different from what we were just doing. So, for example, if you have been writing for 90 minutes, instead of turning on YouTube to watch another mountain biking video, you could get up, stretch, and pull that book off the shelf you’ve been wanting to read, or that article that has been sitting in Pocket for the past six weeks. Maybe reorganizing your desk or taking a walk (see above) around the library with your capture journal would be helpful. Whatever you choose, try to make your breaks productive.

Derek J. Brown is an M.Div and Ph.D graduate of Southern Seminary and is currently serving as pastoral assistant at Grace Bible Fellowship of Silicon Valley overseeing their young adult ministry, Grace Campus Ministries , mid-week Bible studies, website, and social media. He is also an adjunct professor of Christian Theology at Southern Seminary. This article was originally published on his blog www.derekjamesbrown.com . Follow Derek on twitter at @DerekBrown24 .

Academic Lectures

Bookstore events.

Dissertation Writing: Home

Check your Library Account

Dissertation writing.

- Illustrations

What is a dissertation? An extended essay exploring a specified research question or area of practice in depth. Although the word count can vary it is usually longer than most essays, between 5000 - 10000 words.

Your dissertation should demonstrate your ability to:

- Study independently;

- Plan and undertake an in-depth piece of research;

- Select and evaluate information;

- Develop a reasoned argument based on examples and evidence;

- Communicate your ideas and findings effectively.

Dissertation Webinars For further help see - Library & Learning Webinars and Events (see Recorded Webinars tab and Dissertations).

Developing your research Consider your overarching hypothesis and the argument you are going to construct. Be aware that these may change as your research deepens. Use tutor and peer feedback to develop your research.

Begin writing before you have completed your research, because the process of writing will help you clarify your ideas and inform your research.

Research methods To some extent, the topic you choose to investigate will be shaped by existing studies on related topics, so it is important to explore existing literature.

Once you have some awareness of what has already been written about, you need to select the texts, ideas and methods that are most relevant to your particular enquiry.

You may want to research people’s responses to a recent phenomenon, and there may not be very much written about your specific topic: in which case look at the ways that other people have investigated public opinion, find out more about primary research methods (e.g. writing and delivering surveys, interviews, carrying out focus groups and observations etc.)

However, many art subjects are continuations or variations of existing practices and disciplines, and a lot of research is based on evaluating existing texts, which is known as secondary research (e.g. texts written by another researcher).

See also: Finding Resources

See 'The Introduction' under the 'Writing' tab at: Essay Writing .

For longer pieces of writing, chapters serve to break up sections that have different, but related topics. Traditionally, dissertations included a literature review as the first chapter (after the introduction), and a methodology, but check your course requirements.

Chapters can be arranged into key themes, case studies, or they can follow the development of something, chronologically. How you organise them will depend on your topic, and what you want to emphasize. It is helpful for your reader if you explain how you have arranged your chapters in the introduction, so that they know what to expect.

See: Literature Reviews

A methodology is a theoretically-informed approach to the production of knowledge. It usually refers to a chapter or section of a chapter that explains how you went about finding and verifying information, and why you used the methods and processes that you decided to use.

Since research is about finding out more about a subject, methodologies are designed to aid the process, so a good starting point is deciding what you want to find out.

- Your research question (aim)

- What smaller questions (objectives) you think you may need to explore in order to answer your main research question (aim)

- What practical experiments/primary research/secondary research activities you think you will need to undertake to answer these questions (objectives)