Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Methodology

Research Design | Step-by-Step Guide with Examples

Published on 5 May 2022 by Shona McCombes . Revised on 20 March 2023.

A research design is a strategy for answering your research question using empirical data. Creating a research design means making decisions about:

- Your overall aims and approach

- The type of research design you’ll use

- Your sampling methods or criteria for selecting subjects

- Your data collection methods

- The procedures you’ll follow to collect data

- Your data analysis methods

A well-planned research design helps ensure that your methods match your research aims and that you use the right kind of analysis for your data.

Table of contents

Step 1: consider your aims and approach, step 2: choose a type of research design, step 3: identify your population and sampling method, step 4: choose your data collection methods, step 5: plan your data collection procedures, step 6: decide on your data analysis strategies, frequently asked questions.

- Introduction

Before you can start designing your research, you should already have a clear idea of the research question you want to investigate.

There are many different ways you could go about answering this question. Your research design choices should be driven by your aims and priorities – start by thinking carefully about what you want to achieve.

The first choice you need to make is whether you’ll take a qualitative or quantitative approach.

| Qualitative approach | Quantitative approach |

|---|---|

Qualitative research designs tend to be more flexible and inductive , allowing you to adjust your approach based on what you find throughout the research process.

Quantitative research designs tend to be more fixed and deductive , with variables and hypotheses clearly defined in advance of data collection.

It’s also possible to use a mixed methods design that integrates aspects of both approaches. By combining qualitative and quantitative insights, you can gain a more complete picture of the problem you’re studying and strengthen the credibility of your conclusions.

Practical and ethical considerations when designing research

As well as scientific considerations, you need to think practically when designing your research. If your research involves people or animals, you also need to consider research ethics .

- How much time do you have to collect data and write up the research?

- Will you be able to gain access to the data you need (e.g., by travelling to a specific location or contacting specific people)?

- Do you have the necessary research skills (e.g., statistical analysis or interview techniques)?

- Will you need ethical approval ?

At each stage of the research design process, make sure that your choices are practically feasible.

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

Within both qualitative and quantitative approaches, there are several types of research design to choose from. Each type provides a framework for the overall shape of your research.

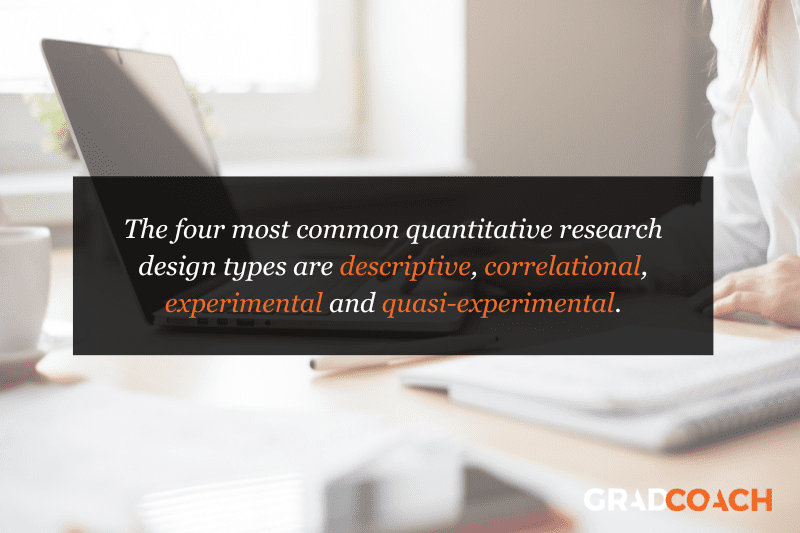

Types of quantitative research designs

Quantitative designs can be split into four main types. Experimental and quasi-experimental designs allow you to test cause-and-effect relationships, while descriptive and correlational designs allow you to measure variables and describe relationships between them.

| Type of design | Purpose and characteristics |

|---|---|

| Experimental | |

| Quasi-experimental | |

| Correlational | |

| Descriptive |

With descriptive and correlational designs, you can get a clear picture of characteristics, trends, and relationships as they exist in the real world. However, you can’t draw conclusions about cause and effect (because correlation doesn’t imply causation ).

Experiments are the strongest way to test cause-and-effect relationships without the risk of other variables influencing the results. However, their controlled conditions may not always reflect how things work in the real world. They’re often also more difficult and expensive to implement.

Types of qualitative research designs

Qualitative designs are less strictly defined. This approach is about gaining a rich, detailed understanding of a specific context or phenomenon, and you can often be more creative and flexible in designing your research.

The table below shows some common types of qualitative design. They often have similar approaches in terms of data collection, but focus on different aspects when analysing the data.

| Type of design | Purpose and characteristics |

|---|---|

| Grounded theory | |

| Phenomenology |

Your research design should clearly define who or what your research will focus on, and how you’ll go about choosing your participants or subjects.

In research, a population is the entire group that you want to draw conclusions about, while a sample is the smaller group of individuals you’ll actually collect data from.

Defining the population

A population can be made up of anything you want to study – plants, animals, organisations, texts, countries, etc. In the social sciences, it most often refers to a group of people.

For example, will you focus on people from a specific demographic, region, or background? Are you interested in people with a certain job or medical condition, or users of a particular product?

The more precisely you define your population, the easier it will be to gather a representative sample.

Sampling methods

Even with a narrowly defined population, it’s rarely possible to collect data from every individual. Instead, you’ll collect data from a sample.

To select a sample, there are two main approaches: probability sampling and non-probability sampling . The sampling method you use affects how confidently you can generalise your results to the population as a whole.

| Probability sampling | Non-probability sampling |

|---|---|

Probability sampling is the most statistically valid option, but it’s often difficult to achieve unless you’re dealing with a very small and accessible population.

For practical reasons, many studies use non-probability sampling, but it’s important to be aware of the limitations and carefully consider potential biases. You should always make an effort to gather a sample that’s as representative as possible of the population.

Case selection in qualitative research

In some types of qualitative designs, sampling may not be relevant.

For example, in an ethnography or a case study, your aim is to deeply understand a specific context, not to generalise to a population. Instead of sampling, you may simply aim to collect as much data as possible about the context you are studying.

In these types of design, you still have to carefully consider your choice of case or community. You should have a clear rationale for why this particular case is suitable for answering your research question.

For example, you might choose a case study that reveals an unusual or neglected aspect of your research problem, or you might choose several very similar or very different cases in order to compare them.

Data collection methods are ways of directly measuring variables and gathering information. They allow you to gain first-hand knowledge and original insights into your research problem.

You can choose just one data collection method, or use several methods in the same study.

Survey methods

Surveys allow you to collect data about opinions, behaviours, experiences, and characteristics by asking people directly. There are two main survey methods to choose from: questionnaires and interviews.

| Questionnaires | Interviews |

|---|---|

Observation methods

Observations allow you to collect data unobtrusively, observing characteristics, behaviours, or social interactions without relying on self-reporting.

Observations may be conducted in real time, taking notes as you observe, or you might make audiovisual recordings for later analysis. They can be qualitative or quantitative.

| Quantitative observation | |

|---|---|

Other methods of data collection

There are many other ways you might collect data depending on your field and topic.

| Field | Examples of data collection methods |

|---|---|

| Media & communication | Collecting a sample of texts (e.g., speeches, articles, or social media posts) for data on cultural norms and narratives |

| Psychology | Using technologies like neuroimaging, eye-tracking, or computer-based tasks to collect data on things like attention, emotional response, or reaction time |

| Education | Using tests or assignments to collect data on knowledge and skills |

| Physical sciences | Using scientific instruments to collect data on things like weight, blood pressure, or chemical composition |

If you’re not sure which methods will work best for your research design, try reading some papers in your field to see what data collection methods they used.

Secondary data

If you don’t have the time or resources to collect data from the population you’re interested in, you can also choose to use secondary data that other researchers already collected – for example, datasets from government surveys or previous studies on your topic.

With this raw data, you can do your own analysis to answer new research questions that weren’t addressed by the original study.

Using secondary data can expand the scope of your research, as you may be able to access much larger and more varied samples than you could collect yourself.

However, it also means you don’t have any control over which variables to measure or how to measure them, so the conclusions you can draw may be limited.

As well as deciding on your methods, you need to plan exactly how you’ll use these methods to collect data that’s consistent, accurate, and unbiased.

Planning systematic procedures is especially important in quantitative research, where you need to precisely define your variables and ensure your measurements are reliable and valid.

Operationalisation

Some variables, like height or age, are easily measured. But often you’ll be dealing with more abstract concepts, like satisfaction, anxiety, or competence. Operationalisation means turning these fuzzy ideas into measurable indicators.

If you’re using observations , which events or actions will you count?

If you’re using surveys , which questions will you ask and what range of responses will be offered?

You may also choose to use or adapt existing materials designed to measure the concept you’re interested in – for example, questionnaires or inventories whose reliability and validity has already been established.

Reliability and validity

Reliability means your results can be consistently reproduced , while validity means that you’re actually measuring the concept you’re interested in.

| Reliability | Validity |

|---|---|

For valid and reliable results, your measurement materials should be thoroughly researched and carefully designed. Plan your procedures to make sure you carry out the same steps in the same way for each participant.

If you’re developing a new questionnaire or other instrument to measure a specific concept, running a pilot study allows you to check its validity and reliability in advance.

Sampling procedures

As well as choosing an appropriate sampling method, you need a concrete plan for how you’ll actually contact and recruit your selected sample.

That means making decisions about things like:

- How many participants do you need for an adequate sample size?

- What inclusion and exclusion criteria will you use to identify eligible participants?

- How will you contact your sample – by mail, online, by phone, or in person?

If you’re using a probability sampling method, it’s important that everyone who is randomly selected actually participates in the study. How will you ensure a high response rate?

If you’re using a non-probability method, how will you avoid bias and ensure a representative sample?

Data management

It’s also important to create a data management plan for organising and storing your data.

Will you need to transcribe interviews or perform data entry for observations? You should anonymise and safeguard any sensitive data, and make sure it’s backed up regularly.

Keeping your data well organised will save time when it comes to analysing them. It can also help other researchers validate and add to your findings.

On their own, raw data can’t answer your research question. The last step of designing your research is planning how you’ll analyse the data.

Quantitative data analysis

In quantitative research, you’ll most likely use some form of statistical analysis . With statistics, you can summarise your sample data, make estimates, and test hypotheses.

Using descriptive statistics , you can summarise your sample data in terms of:

- The distribution of the data (e.g., the frequency of each score on a test)

- The central tendency of the data (e.g., the mean to describe the average score)

- The variability of the data (e.g., the standard deviation to describe how spread out the scores are)

The specific calculations you can do depend on the level of measurement of your variables.

Using inferential statistics , you can:

- Make estimates about the population based on your sample data.

- Test hypotheses about a relationship between variables.

Regression and correlation tests look for associations between two or more variables, while comparison tests (such as t tests and ANOVAs ) look for differences in the outcomes of different groups.

Your choice of statistical test depends on various aspects of your research design, including the types of variables you’re dealing with and the distribution of your data.

Qualitative data analysis

In qualitative research, your data will usually be very dense with information and ideas. Instead of summing it up in numbers, you’ll need to comb through the data in detail, interpret its meanings, identify patterns, and extract the parts that are most relevant to your research question.

Two of the most common approaches to doing this are thematic analysis and discourse analysis .

| Approach | Characteristics |

|---|---|

| Thematic analysis | |

| Discourse analysis |

There are many other ways of analysing qualitative data depending on the aims of your research. To get a sense of potential approaches, try reading some qualitative research papers in your field.

A sample is a subset of individuals from a larger population. Sampling means selecting the group that you will actually collect data from in your research.

For example, if you are researching the opinions of students in your university, you could survey a sample of 100 students.

Statistical sampling allows you to test a hypothesis about the characteristics of a population. There are various sampling methods you can use to ensure that your sample is representative of the population as a whole.

Operationalisation means turning abstract conceptual ideas into measurable observations.

For example, the concept of social anxiety isn’t directly observable, but it can be operationally defined in terms of self-rating scores, behavioural avoidance of crowded places, or physical anxiety symptoms in social situations.

Before collecting data , it’s important to consider how you will operationalise the variables that you want to measure.

The research methods you use depend on the type of data you need to answer your research question .

- If you want to measure something or test a hypothesis , use quantitative methods . If you want to explore ideas, thoughts, and meanings, use qualitative methods .

- If you want to analyse a large amount of readily available data, use secondary data. If you want data specific to your purposes with control over how they are generated, collect primary data.

- If you want to establish cause-and-effect relationships between variables , use experimental methods. If you want to understand the characteristics of a research subject, use descriptive methods.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, March 20). Research Design | Step-by-Step Guide with Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved 26 August 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/research-methods/research-design/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

- How it works

How to Write a Research Design – Guide with Examples

Published by Alaxendra Bets at August 14th, 2021 , Revised On June 24, 2024

A research design is a structure that combines different components of research. It involves the use of different data collection and data analysis techniques logically to answer the research questions .

It would be best to make some decisions about addressing the research questions adequately before starting the research process, which is achieved with the help of the research design.

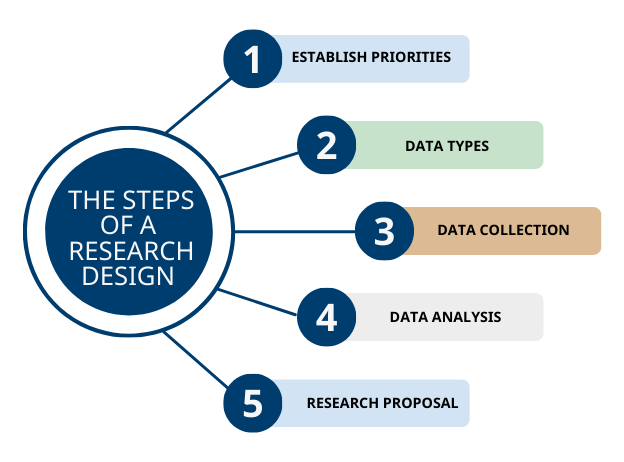

Below are the key aspects of the decision-making process:

- Data type required for research

- Research resources

- Participants required for research

- Hypothesis based upon research question(s)

- Data analysis methodologies

- Variables (Independent, dependent, and confounding)

- The location and timescale for conducting the data

- The time period required for research

The research design provides the strategy of investigation for your project. Furthermore, it defines the parameters and criteria to compile the data to evaluate results and conclude.

Your project’s validity depends on the data collection and interpretation techniques. A strong research design reflects a strong dissertation , scientific paper, or research proposal .

Step 1: Establish Priorities for Research Design

Before conducting any research study, you must address an important question: “how to create a research design.”

The research design depends on the researcher’s priorities and choices because every research has different priorities. For a complex research study involving multiple methods, you may choose to have more than one research design.

Multimethodology or multimethod research includes using more than one data collection method or research in a research study or set of related studies.

If one research design is weak in one area, then another research design can cover that weakness. For instance, a dissertation analyzing different situations or cases will have more than one research design.

For example:

- Experimental research involves experimental investigation and laboratory experience, but it does not accurately investigate the real world.

- Quantitative research is good for the statistical part of the project, but it may not provide an in-depth understanding of the topic .

- Also, correlational research will not provide experimental results because it is a technique that assesses the statistical relationship between two variables.

While scientific considerations are a fundamental aspect of the research design, It is equally important that the researcher think practically before deciding on its structure. Here are some questions that you should think of;

- Do you have enough time to gather data and complete the write-up?

- Will you be able to collect the necessary data by interviewing a specific person or visiting a specific location?

- Do you have in-depth knowledge about the different statistical analysis and data collection techniques to address the research questions or test the hypothesis ?

If you think that the chosen research design cannot answer the research questions properly, you can refine your research questions to gain better insight.

Step 2: Data Type you Need for Research

Decide on the type of data you need for your research. The type of data you need to collect depends on your research questions or research hypothesis. Two types of research data can be used to answer the research questions:

Primary Data Vs. Secondary Data

| The researcher collects the primary data from first-hand sources with the help of different data collection methods such as interviews, experiments, surveys, etc. Primary research data is considered far more authentic and relevant, but it involves additional cost and time. | |

| Research on academic references which themselves incorporate primary data will be regarded as secondary data. There is no need to do a survey or interview with a person directly, and it is time effective. The researcher should focus on the validity and reliability of the source. |

Qualitative Vs. Quantitative Data

| This type of data encircles the researcher’s descriptive experience and shows the relationship between the observation and collected data. It involves interpretation and conceptual understanding of the research. There are many theories involved which can approve or disapprove the mathematical and statistical calculation. For instance, you are searching how to write a research design proposal. It means you require qualitative data about the mentioned topic. | |

| If your research requires statistical and mathematical approaches for measuring the variable and testing your hypothesis, your objective is to compile quantitative data. Many businesses and researchers use this type of data with pre-determined data collection methods and variables for their research design. |

Also, see; Research methods, design, and analysis .

Need help with a thesis chapter?

- Hire an expert from ResearchProspect today!

- Statistical analysis, research methodology, discussion of the results or conclusion – our experts can help you no matter how complex the requirements are.

Step 3: Data Collection Techniques

Once you have selected the type of research to answer your research question, you need to decide where and how to collect the data.

It is time to determine your research method to address the research problem . Research methods involve procedures, techniques, materials, and tools used for the study.

For instance, a dissertation research design includes the different resources and data collection techniques and helps establish your dissertation’s structure .

The following table shows the characteristics of the most popularly employed research methods.

Research Methods

| Methods | What to consider |

|---|---|

| Surveys | The survey planning requires; Selection of responses and how many responses are required for the research? Survey distribution techniques (online, by post, in person, etc.) Techniques to design the question |

| Interviews | Criteria to select the interviewee. Time and location of the interview. Type of interviews; i.e., structured, semi-structured, or unstructured |

| Experiments | Place of the experiment; laboratory or in the field. Measuring of the variables Design of the experiment |

| Secondary Data | Criteria to select the references and source for the data. The reliability of the references. The technique used for compiling the data source. |

Step 4: Procedure of Data Analysis

Use of the correct data and statistical analysis technique is necessary for the validity of your research. Therefore, you need to be certain about the data type that would best address the research problem. Choosing an appropriate analysis method is the final step for the research design. It can be split into two main categories;

Quantitative Data Analysis

The quantitative data analysis technique involves analyzing the numerical data with the help of different applications such as; SPSS, STATA, Excel, origin lab, etc.

This data analysis strategy tests different variables such as spectrum, frequencies, averages, and more. The research question and the hypothesis must be established to identify the variables for testing.

Qualitative Data Analysis

Qualitative data analysis of figures, themes, and words allows for flexibility and the researcher’s subjective opinions. This means that the researcher’s primary focus will be interpreting patterns, tendencies, and accounts and understanding the implications and social framework.

You should be clear about your research objectives before starting to analyze the data. For example, you should ask yourself whether you need to explain respondents’ experiences and insights or do you also need to evaluate their responses with reference to a certain social framework.

Step 5: Write your Research Proposal

The research design is an important component of a research proposal because it plans the project’s execution. You can share it with the supervisor, who would evaluate the feasibility and capacity of the results and conclusion .

Read our guidelines to write a research proposal if you have already formulated your research design. The research proposal is written in the future tense because you are writing your proposal before conducting research.

The research methodology or research design, on the other hand, is generally written in the past tense.

How to Write a Research Design – Conclusion

A research design is the plan, structure, strategy of investigation conceived to answer the research question and test the hypothesis. The dissertation research design can be classified based on the type of data and the type of analysis.

Above mentioned five steps are the answer to how to write a research design. So, follow these steps to formulate the perfect research design for your dissertation .

ResearchProspect writers have years of experience creating research designs that align with the dissertation’s aim and objectives. If you are struggling with your dissertation methodology chapter, you might want to look at our dissertation part-writing service.

Our dissertation writers can also help you with the full dissertation paper . No matter how urgent or complex your need may be, ResearchProspect can help. We also offer PhD level research paper writing services.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is research design.

Research design is a systematic plan that guides the research process, outlining the methodology and procedures for collecting and analysing data. It determines the structure of the study, ensuring the research question is answered effectively, reliably, and validly. It serves as the blueprint for the entire research project.

How to write a research design?

To write a research design, define your research question, identify the research method (qualitative, quantitative, or mixed), choose data collection techniques (e.g., surveys, interviews), determine the sample size and sampling method, outline data analysis procedures, and highlight potential limitations and ethical considerations for the study.

How to write the design section of a research paper?

In the design section of a research paper, describe the research methodology chosen and justify its selection. Outline the data collection methods, participants or samples, instruments used, and procedures followed. Detail any experimental controls, if applicable. Ensure clarity and precision to enable replication of the study by other researchers.

How to write a research design in methodology?

To write a research design in methodology, clearly outline the research strategy (e.g., experimental, survey, case study). Describe the sampling technique, participants, and data collection methods. Detail the procedures for data collection and analysis. Justify choices by linking them to research objectives, addressing reliability and validity.

You May Also Like

Struggling to find relevant and up-to-date topics for your dissertation? Here is all you need to know if unsure about how to choose dissertation topic.

Repository of ten perfect research question examples will provide you a better perspective about how to create research questions.

How to write a hypothesis for dissertation,? A hypothesis is a statement that can be tested with the help of experimental or theoretical research.

USEFUL LINKS

LEARNING RESOURCES

COMPANY DETAILS

- How It Works

Chapter 2. Research Design

Getting started.

When I teach undergraduates qualitative research methods, the final product of the course is a “research proposal” that incorporates all they have learned and enlists the knowledge they have learned about qualitative research methods in an original design that addresses a particular research question. I highly recommend you think about designing your own research study as you progress through this textbook. Even if you don’t have a study in mind yet, it can be a helpful exercise as you progress through the course. But how to start? How can one design a research study before they even know what research looks like? This chapter will serve as a brief overview of the research design process to orient you to what will be coming in later chapters. Think of it as a “skeleton” of what you will read in more detail in later chapters. Ideally, you will read this chapter both now (in sequence) and later during your reading of the remainder of the text. Do not worry if you have questions the first time you read this chapter. Many things will become clearer as the text advances and as you gain a deeper understanding of all the components of good qualitative research. This is just a preliminary map to get you on the right road.

Research Design Steps

Before you even get started, you will need to have a broad topic of interest in mind. [1] . In my experience, students can confuse this broad topic with the actual research question, so it is important to clearly distinguish the two. And the place to start is the broad topic. It might be, as was the case with me, working-class college students. But what about working-class college students? What’s it like to be one? Why are there so few compared to others? How do colleges assist (or fail to assist) them? What interested me was something I could barely articulate at first and went something like this: “Why was it so difficult and lonely to be me?” And by extension, “Did others share this experience?”

Once you have a general topic, reflect on why this is important to you. Sometimes we connect with a topic and we don’t really know why. Even if you are not willing to share the real underlying reason you are interested in a topic, it is important that you know the deeper reasons that motivate you. Otherwise, it is quite possible that at some point during the research, you will find yourself turned around facing the wrong direction. I have seen it happen many times. The reason is that the research question is not the same thing as the general topic of interest, and if you don’t know the reasons for your interest, you are likely to design a study answering a research question that is beside the point—to you, at least. And this means you will be much less motivated to carry your research to completion.

Researcher Note

Why do you employ qualitative research methods in your area of study? What are the advantages of qualitative research methods for studying mentorship?

Qualitative research methods are a huge opportunity to increase access, equity, inclusion, and social justice. Qualitative research allows us to engage and examine the uniquenesses/nuances within minoritized and dominant identities and our experiences with these identities. Qualitative research allows us to explore a specific topic, and through that exploration, we can link history to experiences and look for patterns or offer up a unique phenomenon. There’s such beauty in being able to tell a particular story, and qualitative research is a great mode for that! For our work, we examined the relationships we typically use the term mentorship for but didn’t feel that was quite the right word. Qualitative research allowed us to pick apart what we did and how we engaged in our relationships, which then allowed us to more accurately describe what was unique about our mentorship relationships, which we ultimately named liberationships ( McAloney and Long 2021) . Qualitative research gave us the means to explore, process, and name our experiences; what a powerful tool!

How do you come up with ideas for what to study (and how to study it)? Where did you get the idea for studying mentorship?

Coming up with ideas for research, for me, is kind of like Googling a question I have, not finding enough information, and then deciding to dig a little deeper to get the answer. The idea to study mentorship actually came up in conversation with my mentorship triad. We were talking in one of our meetings about our relationship—kind of meta, huh? We discussed how we felt that mentorship was not quite the right term for the relationships we had built. One of us asked what was different about our relationships and mentorship. This all happened when I was taking an ethnography course. During the next session of class, we were discussing auto- and duoethnography, and it hit me—let’s explore our version of mentorship, which we later went on to name liberationships ( McAloney and Long 2021 ). The idea and questions came out of being curious and wanting to find an answer. As I continue to research, I see opportunities in questions I have about my work or during conversations that, in our search for answers, end up exposing gaps in the literature. If I can’t find the answer already out there, I can study it.

—Kim McAloney, PhD, College Student Services Administration Ecampus coordinator and instructor

When you have a better idea of why you are interested in what it is that interests you, you may be surprised to learn that the obvious approaches to the topic are not the only ones. For example, let’s say you think you are interested in preserving coastal wildlife. And as a social scientist, you are interested in policies and practices that affect the long-term viability of coastal wildlife, especially around fishing communities. It would be natural then to consider designing a research study around fishing communities and how they manage their ecosystems. But when you really think about it, you realize that what interests you the most is how people whose livelihoods depend on a particular resource act in ways that deplete that resource. Or, even deeper, you contemplate the puzzle, “How do people justify actions that damage their surroundings?” Now, there are many ways to design a study that gets at that broader question, and not all of them are about fishing communities, although that is certainly one way to go. Maybe you could design an interview-based study that includes and compares loggers, fishers, and desert golfers (those who golf in arid lands that require a great deal of wasteful irrigation). Or design a case study around one particular example where resources were completely used up by a community. Without knowing what it is you are really interested in, what motivates your interest in a surface phenomenon, you are unlikely to come up with the appropriate research design.

These first stages of research design are often the most difficult, but have patience . Taking the time to consider why you are going to go through a lot of trouble to get answers will prevent a lot of wasted energy in the future.

There are distinct reasons for pursuing particular research questions, and it is helpful to distinguish between them. First, you may be personally motivated. This is probably the most important and the most often overlooked. What is it about the social world that sparks your curiosity? What bothers you? What answers do you need in order to keep living? For me, I knew I needed to get a handle on what higher education was for before I kept going at it. I needed to understand why I felt so different from my peers and whether this whole “higher education” thing was “for the likes of me” before I could complete my degree. That is the personal motivation question. Your personal motivation might also be political in nature, in that you want to change the world in a particular way. It’s all right to acknowledge this. In fact, it is better to acknowledge it than to hide it.

There are also academic and professional motivations for a particular study. If you are an absolute beginner, these may be difficult to find. We’ll talk more about this when we discuss reviewing the literature. Simply put, you are probably not the only person in the world to have thought about this question or issue and those related to it. So how does your interest area fit into what others have studied? Perhaps there is a good study out there of fishing communities, but no one has quite asked the “justification” question. You are motivated to address this to “fill the gap” in our collective knowledge. And maybe you are really not at all sure of what interests you, but you do know that [insert your topic] interests a lot of people, so you would like to work in this area too. You want to be involved in the academic conversation. That is a professional motivation and a very important one to articulate.

Practical and strategic motivations are a third kind. Perhaps you want to encourage people to take better care of the natural resources around them. If this is also part of your motivation, you will want to design your research project in a way that might have an impact on how people behave in the future. There are many ways to do this, one of which is using qualitative research methods rather than quantitative research methods, as the findings of qualitative research are often easier to communicate to a broader audience than the results of quantitative research. You might even be able to engage the community you are studying in the collecting and analyzing of data, something taboo in quantitative research but actively embraced and encouraged by qualitative researchers. But there are other practical reasons, such as getting “done” with your research in a certain amount of time or having access (or no access) to certain information. There is nothing wrong with considering constraints and opportunities when designing your study. Or maybe one of the practical or strategic goals is about learning competence in this area so that you can demonstrate the ability to conduct interviews and focus groups with future employers. Keeping that in mind will help shape your study and prevent you from getting sidetracked using a technique that you are less invested in learning about.

STOP HERE for a moment

I recommend you write a paragraph (at least) explaining your aims and goals. Include a sentence about each of the following: personal/political goals, practical or professional/academic goals, and practical/strategic goals. Think through how all of the goals are related and can be achieved by this particular research study . If they can’t, have a rethink. Perhaps this is not the best way to go about it.

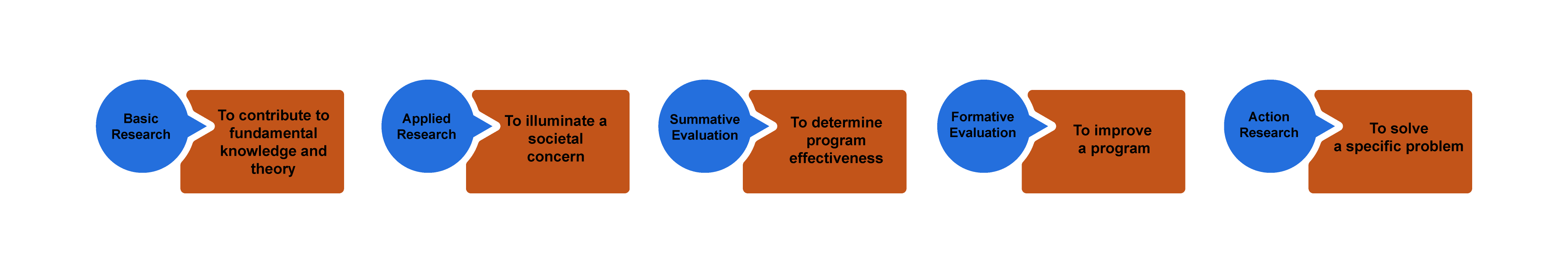

You will also want to be clear about the purpose of your study. “Wait, didn’t we just do this?” you might ask. No! Your goals are not the same as the purpose of the study, although they are related. You can think about purpose lying on a continuum from “ theory ” to “action” (figure 2.1). Sometimes you are doing research to discover new knowledge about the world, while other times you are doing a study because you want to measure an impact or make a difference in the world.

Basic research involves research that is done for the sake of “pure” knowledge—that is, knowledge that, at least at this moment in time, may not have any apparent use or application. Often, and this is very important, knowledge of this kind is later found to be extremely helpful in solving problems. So one way of thinking about basic research is that it is knowledge for which no use is yet known but will probably one day prove to be extremely useful. If you are doing basic research, you do not need to argue its usefulness, as the whole point is that we just don’t know yet what this might be.

Researchers engaged in basic research want to understand how the world operates. They are interested in investigating a phenomenon to get at the nature of reality with regard to that phenomenon. The basic researcher’s purpose is to understand and explain ( Patton 2002:215 ).

Basic research is interested in generating and testing hypotheses about how the world works. Grounded Theory is one approach to qualitative research methods that exemplifies basic research (see chapter 4). Most academic journal articles publish basic research findings. If you are working in academia (e.g., writing your dissertation), the default expectation is that you are conducting basic research.

Applied research in the social sciences is research that addresses human and social problems. Unlike basic research, the researcher has expectations that the research will help contribute to resolving a problem, if only by identifying its contours, history, or context. From my experience, most students have this as their baseline assumption about research. Why do a study if not to make things better? But this is a common mistake. Students and their committee members are often working with default assumptions here—the former thinking about applied research as their purpose, the latter thinking about basic research: “The purpose of applied research is to contribute knowledge that will help people to understand the nature of a problem in order to intervene, thereby allowing human beings to more effectively control their environment. While in basic research the source of questions is the tradition within a scholarly discipline, in applied research the source of questions is in the problems and concerns experienced by people and by policymakers” ( Patton 2002:217 ).

Applied research is less geared toward theory in two ways. First, its questions do not derive from previous literature. For this reason, applied research studies have much more limited literature reviews than those found in basic research (although they make up for this by having much more “background” about the problem). Second, it does not generate theory in the same way as basic research does. The findings of an applied research project may not be generalizable beyond the boundaries of this particular problem or context. The findings are more limited. They are useful now but may be less useful later. This is why basic research remains the default “gold standard” of academic research.

Evaluation research is research that is designed to evaluate or test the effectiveness of specific solutions and programs addressing specific social problems. We already know the problems, and someone has already come up with solutions. There might be a program, say, for first-generation college students on your campus. Does this program work? Are first-generation students who participate in the program more likely to graduate than those who do not? These are the types of questions addressed by evaluation research. There are two types of research within this broader frame; however, one more action-oriented than the next. In summative evaluation , an overall judgment about the effectiveness of a program or policy is made. Should we continue our first-gen program? Is it a good model for other campuses? Because the purpose of such summative evaluation is to measure success and to determine whether this success is scalable (capable of being generalized beyond the specific case), quantitative data is more often used than qualitative data. In our example, we might have “outcomes” data for thousands of students, and we might run various tests to determine if the better outcomes of those in the program are statistically significant so that we can generalize the findings and recommend similar programs elsewhere. Qualitative data in the form of focus groups or interviews can then be used for illustrative purposes, providing more depth to the quantitative analyses. In contrast, formative evaluation attempts to improve a program or policy (to help “form” or shape its effectiveness). Formative evaluations rely more heavily on qualitative data—case studies, interviews, focus groups. The findings are meant not to generalize beyond the particular but to improve this program. If you are a student seeking to improve your qualitative research skills and you do not care about generating basic research, formative evaluation studies might be an attractive option for you to pursue, as there are always local programs that need evaluation and suggestions for improvement. Again, be very clear about your purpose when talking through your research proposal with your committee.

Action research takes a further step beyond evaluation, even formative evaluation, to being part of the solution itself. This is about as far from basic research as one could get and definitely falls beyond the scope of “science,” as conventionally defined. The distinction between action and research is blurry, the research methods are often in constant flux, and the only “findings” are specific to the problem or case at hand and often are findings about the process of intervention itself. Rather than evaluate a program as a whole, action research often seeks to change and improve some particular aspect that may not be working—maybe there is not enough diversity in an organization or maybe women’s voices are muted during meetings and the organization wonders why and would like to change this. In a further step, participatory action research , those women would become part of the research team, attempting to amplify their voices in the organization through participation in the action research. As action research employs methods that involve people in the process, focus groups are quite common.

If you are working on a thesis or dissertation, chances are your committee will expect you to be contributing to fundamental knowledge and theory ( basic research ). If your interests lie more toward the action end of the continuum, however, it is helpful to talk to your committee about this before you get started. Knowing your purpose in advance will help avoid misunderstandings during the later stages of the research process!

The Research Question

Once you have written your paragraph and clarified your purpose and truly know that this study is the best study for you to be doing right now , you are ready to write and refine your actual research question. Know that research questions are often moving targets in qualitative research, that they can be refined up to the very end of data collection and analysis. But you do have to have a working research question at all stages. This is your “anchor” when you get lost in the data. What are you addressing? What are you looking at and why? Your research question guides you through the thicket. It is common to have a whole host of questions about a phenomenon or case, both at the outset and throughout the study, but you should be able to pare it down to no more than two or three sentences when asked. These sentences should both clarify the intent of the research and explain why this is an important question to answer. More on refining your research question can be found in chapter 4.

Chances are, you will have already done some prior reading before coming up with your interest and your questions, but you may not have conducted a systematic literature review. This is the next crucial stage to be completed before venturing further. You don’t want to start collecting data and then realize that someone has already beaten you to the punch. A review of the literature that is already out there will let you know (1) if others have already done the study you are envisioning; (2) if others have done similar studies, which can help you out; and (3) what ideas or concepts are out there that can help you frame your study and make sense of your findings. More on literature reviews can be found in chapter 9.

In addition to reviewing the literature for similar studies to what you are proposing, it can be extremely helpful to find a study that inspires you. This may have absolutely nothing to do with the topic you are interested in but is written so beautifully or organized so interestingly or otherwise speaks to you in such a way that you want to post it somewhere to remind you of what you want to be doing. You might not understand this in the early stages—why would you find a study that has nothing to do with the one you are doing helpful? But trust me, when you are deep into analysis and writing, having an inspirational model in view can help you push through. If you are motivated to do something that might change the world, you probably have read something somewhere that inspired you. Go back to that original inspiration and read it carefully and see how they managed to convey the passion that you so appreciate.

At this stage, you are still just getting started. There are a lot of things to do before setting forth to collect data! You’ll want to consider and choose a research tradition and a set of data-collection techniques that both help you answer your research question and match all your aims and goals. For example, if you really want to help migrant workers speak for themselves, you might draw on feminist theory and participatory action research models. Chapters 3 and 4 will provide you with more information on epistemologies and approaches.

Next, you have to clarify your “units of analysis.” What is the level at which you are focusing your study? Often, the unit in qualitative research methods is individual people, or “human subjects.” But your units of analysis could just as well be organizations (colleges, hospitals) or programs or even whole nations. Think about what it is you want to be saying at the end of your study—are the insights you are hoping to make about people or about organizations or about something else entirely? A unit of analysis can even be a historical period! Every unit of analysis will call for a different kind of data collection and analysis and will produce different kinds of “findings” at the conclusion of your study. [2]

Regardless of what unit of analysis you select, you will probably have to consider the “human subjects” involved in your research. [3] Who are they? What interactions will you have with them—that is, what kind of data will you be collecting? Before answering these questions, define your population of interest and your research setting. Use your research question to help guide you.

Let’s use an example from a real study. In Geographies of Campus Inequality , Benson and Lee ( 2020 ) list three related research questions: “(1) What are the different ways that first-generation students organize their social, extracurricular, and academic activities at selective and highly selective colleges? (2) how do first-generation students sort themselves and get sorted into these different types of campus lives; and (3) how do these different patterns of campus engagement prepare first-generation students for their post-college lives?” (3).

Note that we are jumping into this a bit late, after Benson and Lee have described previous studies (the literature review) and what is known about first-generation college students and what is not known. They want to know about differences within this group, and they are interested in ones attending certain kinds of colleges because those colleges will be sites where academic and extracurricular pressures compete. That is the context for their three related research questions. What is the population of interest here? First-generation college students . What is the research setting? Selective and highly selective colleges . But a host of questions remain. Which students in the real world, which colleges? What about gender, race, and other identity markers? Will the students be asked questions? Are the students still in college, or will they be asked about what college was like for them? Will they be observed? Will they be shadowed? Will they be surveyed? Will they be asked to keep diaries of their time in college? How many students? How many colleges? For how long will they be observed?

Recommendation

Take a moment and write down suggestions for Benson and Lee before continuing on to what they actually did.

Have you written down your own suggestions? Good. Now let’s compare those with what they actually did. Benson and Lee drew on two sources of data: in-depth interviews with sixty-four first-generation students and survey data from a preexisting national survey of students at twenty-eight selective colleges. Let’s ignore the survey for our purposes here and focus on those interviews. The interviews were conducted between 2014 and 2016 at a single selective college, “Hilltop” (a pseudonym ). They employed a “purposive” sampling strategy to ensure an equal number of male-identifying and female-identifying students as well as equal numbers of White, Black, and Latinx students. Each student was interviewed once. Hilltop is a selective liberal arts college in the northeast that enrolls about three thousand students.

How did your suggestions match up to those actually used by the researchers in this study? It is possible your suggestions were too ambitious? Beginning qualitative researchers can often make that mistake. You want a research design that is both effective (it matches your question and goals) and doable. You will never be able to collect data from your entire population of interest (unless your research question is really so narrow to be relevant to very few people!), so you will need to come up with a good sample. Define the criteria for this sample, as Benson and Lee did when deciding to interview an equal number of students by gender and race categories. Define the criteria for your sample setting too. Hilltop is typical for selective colleges. That was a research choice made by Benson and Lee. For more on sampling and sampling choices, see chapter 5.

Benson and Lee chose to employ interviews. If you also would like to include interviews, you have to think about what will be asked in them. Most interview-based research involves an interview guide, a set of questions or question areas that will be asked of each participant. The research question helps you create a relevant interview guide. You want to ask questions whose answers will provide insight into your research question. Again, your research question is the anchor you will continually come back to as you plan for and conduct your study. It may be that once you begin interviewing, you find that people are telling you something totally unexpected, and this makes you rethink your research question. That is fine. Then you have a new anchor. But you always have an anchor. More on interviewing can be found in chapter 11.

Let’s imagine Benson and Lee also observed college students as they went about doing the things college students do, both in the classroom and in the clubs and social activities in which they participate. They would have needed a plan for this. Would they sit in on classes? Which ones and how many? Would they attend club meetings and sports events? Which ones and how many? Would they participate themselves? How would they record their observations? More on observation techniques can be found in both chapters 13 and 14.

At this point, the design is almost complete. You know why you are doing this study, you have a clear research question to guide you, you have identified your population of interest and research setting, and you have a reasonable sample of each. You also have put together a plan for data collection, which might include drafting an interview guide or making plans for observations. And so you know exactly what you will be doing for the next several months (or years!). To put the project into action, there are a few more things necessary before actually going into the field.

First, you will need to make sure you have any necessary supplies, including recording technology. These days, many researchers use their phones to record interviews. Second, you will need to draft a few documents for your participants. These include informed consent forms and recruiting materials, such as posters or email texts, that explain what this study is in clear language. Third, you will draft a research protocol to submit to your institutional review board (IRB) ; this research protocol will include the interview guide (if you are using one), the consent form template, and all examples of recruiting material. Depending on your institution and the details of your study design, it may take weeks or even, in some unfortunate cases, months before you secure IRB approval. Make sure you plan on this time in your project timeline. While you wait, you can continue to review the literature and possibly begin drafting a section on the literature review for your eventual presentation/publication. More on IRB procedures can be found in chapter 8 and more general ethical considerations in chapter 7.

Once you have approval, you can begin!

Research Design Checklist

Before data collection begins, do the following:

- Write a paragraph explaining your aims and goals (personal/political, practical/strategic, professional/academic).

- Define your research question; write two to three sentences that clarify the intent of the research and why this is an important question to answer.

- Review the literature for similar studies that address your research question or similar research questions; think laterally about some literature that might be helpful or illuminating but is not exactly about the same topic.

- Find a written study that inspires you—it may or may not be on the research question you have chosen.

- Consider and choose a research tradition and set of data-collection techniques that (1) help answer your research question and (2) match your aims and goals.

- Define your population of interest and your research setting.

- Define the criteria for your sample (How many? Why these? How will you find them, gain access, and acquire consent?).

- If you are conducting interviews, draft an interview guide.

- If you are making observations, create a plan for observations (sites, times, recording, access).

- Acquire any necessary technology (recording devices/software).

- Draft consent forms that clearly identify the research focus and selection process.

- Create recruiting materials (posters, email, texts).

- Apply for IRB approval (proposal plus consent form plus recruiting materials).

- Block out time for collecting data.

- At the end of the chapter, you will find a " Research Design Checklist " that summarizes the main recommendations made here ↵

- For example, if your focus is society and culture , you might collect data through observation or a case study. If your focus is individual lived experience , you are probably going to be interviewing some people. And if your focus is language and communication , you will probably be analyzing text (written or visual). ( Marshall and Rossman 2016:16 ). ↵

- You may not have any "live" human subjects. There are qualitative research methods that do not require interactions with live human beings - see chapter 16 , "Archival and Historical Sources." But for the most part, you are probably reading this textbook because you are interested in doing research with people. The rest of the chapter will assume this is the case. ↵

One of the primary methodological traditions of inquiry in qualitative research, ethnography is the study of a group or group culture, largely through observational fieldwork supplemented by interviews. It is a form of fieldwork that may include participant-observation data collection. See chapter 14 for a discussion of deep ethnography.

A methodological tradition of inquiry and research design that focuses on an individual case (e.g., setting, institution, or sometimes an individual) in order to explore its complexity, history, and interactive parts. As an approach, it is particularly useful for obtaining a deep appreciation of an issue, event, or phenomenon of interest in its particular context.

The controlling force in research; can be understood as lying on a continuum from basic research (knowledge production) to action research (effecting change).

In its most basic sense, a theory is a story we tell about how the world works that can be tested with empirical evidence. In qualitative research, we use the term in a variety of ways, many of which are different from how they are used by quantitative researchers. Although some qualitative research can be described as “testing theory,” it is more common to “build theory” from the data using inductive reasoning , as done in Grounded Theory . There are so-called “grand theories” that seek to integrate a whole series of findings and stories into an overarching paradigm about how the world works, and much smaller theories or concepts about particular processes and relationships. Theory can even be used to explain particular methodological perspectives or approaches, as in Institutional Ethnography , which is both a way of doing research and a theory about how the world works.

Research that is interested in generating and testing hypotheses about how the world works.

A methodological tradition of inquiry and approach to analyzing qualitative data in which theories emerge from a rigorous and systematic process of induction. This approach was pioneered by the sociologists Glaser and Strauss (1967). The elements of theory generated from comparative analysis of data are, first, conceptual categories and their properties and, second, hypotheses or generalized relations among the categories and their properties – “The constant comparing of many groups draws the [researcher’s] attention to their many similarities and differences. Considering these leads [the researcher] to generate abstract categories and their properties, which, since they emerge from the data, will clearly be important to a theory explaining the kind of behavior under observation.” (36).

An approach to research that is “multimethod in focus, involving an interpretative, naturalistic approach to its subject matter. This means that qualitative researchers study things in their natural settings, attempting to make sense of, or interpret, phenomena in terms of the meanings people bring to them. Qualitative research involves the studied use and collection of a variety of empirical materials – case study, personal experience, introspective, life story, interview, observational, historical, interactional, and visual texts – that describe routine and problematic moments and meanings in individuals’ lives." ( Denzin and Lincoln 2005:2 ). Contrast with quantitative research .

Research that contributes knowledge that will help people to understand the nature of a problem in order to intervene, thereby allowing human beings to more effectively control their environment.

Research that is designed to evaluate or test the effectiveness of specific solutions and programs addressing specific social problems. There are two kinds: summative and formative .

Research in which an overall judgment about the effectiveness of a program or policy is made, often for the purpose of generalizing to other cases or programs. Generally uses qualitative research as a supplement to primary quantitative data analyses. Contrast formative evaluation research .

Research designed to improve a program or policy (to help “form” or shape its effectiveness); relies heavily on qualitative research methods. Contrast summative evaluation research

Research carried out at a particular organizational or community site with the intention of affecting change; often involves research subjects as participants of the study. See also participatory action research .

Research in which both researchers and participants work together to understand a problematic situation and change it for the better.

The level of the focus of analysis (e.g., individual people, organizations, programs, neighborhoods).

The large group of interest to the researcher. Although it will likely be impossible to design a study that incorporates or reaches all members of the population of interest, this should be clearly defined at the outset of a study so that a reasonable sample of the population can be taken. For example, if one is studying working-class college students, the sample may include twenty such students attending a particular college, while the population is “working-class college students.” In quantitative research, clearly defining the general population of interest is a necessary step in generalizing results from a sample. In qualitative research, defining the population is conceptually important for clarity.

A fictional name assigned to give anonymity to a person, group, or place. Pseudonyms are important ways of protecting the identity of research participants while still providing a “human element” in the presentation of qualitative data. There are ethical considerations to be made in selecting pseudonyms; some researchers allow research participants to choose their own.

A requirement for research involving human participants; the documentation of informed consent. In some cases, oral consent or assent may be sufficient, but the default standard is a single-page easy-to-understand form that both the researcher and the participant sign and date. Under federal guidelines, all researchers "shall seek such consent only under circumstances that provide the prospective subject or the representative sufficient opportunity to consider whether or not to participate and that minimize the possibility of coercion or undue influence. The information that is given to the subject or the representative shall be in language understandable to the subject or the representative. No informed consent, whether oral or written, may include any exculpatory language through which the subject or the representative is made to waive or appear to waive any of the subject's rights or releases or appears to release the investigator, the sponsor, the institution, or its agents from liability for negligence" (21 CFR 50.20). Your IRB office will be able to provide a template for use in your study .

An administrative body established to protect the rights and welfare of human research subjects recruited to participate in research activities conducted under the auspices of the institution with which it is affiliated. The IRB is charged with the responsibility of reviewing all research involving human participants. The IRB is concerned with protecting the welfare, rights, and privacy of human subjects. The IRB has the authority to approve, disapprove, monitor, and require modifications in all research activities that fall within its jurisdiction as specified by both the federal regulations and institutional policy.

Introduction to Qualitative Research Methods Copyright © 2023 by Allison Hurst is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

- USC Libraries

- Research Guides

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper

- Types of Research Designs

- Purpose of Guide

- Design Flaws to Avoid

- Independent and Dependent Variables

- Glossary of Research Terms

- Reading Research Effectively

- Narrowing a Topic Idea

- Broadening a Topic Idea

- Extending the Timeliness of a Topic Idea

- Academic Writing Style

- Applying Critical Thinking

- Choosing a Title

- Making an Outline

- Paragraph Development

- Research Process Video Series

- Executive Summary

- The C.A.R.S. Model

- Background Information

- The Research Problem/Question

- Theoretical Framework

- Citation Tracking

- Content Alert Services

- Evaluating Sources

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

- Tiertiary Sources

- Scholarly vs. Popular Publications

- Qualitative Methods

- Quantitative Methods

- Insiderness

- Using Non-Textual Elements

- Limitations of the Study

- Common Grammar Mistakes

- Writing Concisely

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Footnotes or Endnotes?

- Further Readings

- Generative AI and Writing

- USC Libraries Tutorials and Other Guides

- Bibliography

Introduction

Before beginning your paper, you need to decide how you plan to design the study .

The research design refers to the overall strategy and analytical approach that you have chosen in order to integrate, in a coherent and logical way, the different components of the study, thus ensuring that the research problem will be thoroughly investigated. It constitutes the blueprint for the collection, measurement, and interpretation of information and data. Note that the research problem determines the type of design you choose, not the other way around!

De Vaus, D. A. Research Design in Social Research . London: SAGE, 2001; Trochim, William M.K. Research Methods Knowledge Base. 2006.

General Structure and Writing Style

The function of a research design is to ensure that the evidence obtained enables you to effectively address the research problem logically and as unambiguously as possible . In social sciences research, obtaining information relevant to the research problem generally entails specifying the type of evidence needed to test the underlying assumptions of a theory, to evaluate a program, or to accurately describe and assess meaning related to an observable phenomenon.

With this in mind, a common mistake made by researchers is that they begin their investigations before they have thought critically about what information is required to address the research problem. Without attending to these design issues beforehand, the overall research problem will not be adequately addressed and any conclusions drawn will run the risk of being weak and unconvincing. As a consequence, the overall validity of the study will be undermined.

The length and complexity of describing the research design in your paper can vary considerably, but any well-developed description will achieve the following :

- Identify the research problem clearly and justify its selection, particularly in relation to any valid alternative designs that could have been used,

- Review and synthesize previously published literature associated with the research problem,

- Clearly and explicitly specify hypotheses [i.e., research questions] central to the problem,

- Effectively describe the information and/or data which will be necessary for an adequate testing of the hypotheses and explain how such information and/or data will be obtained, and

- Describe the methods of analysis to be applied to the data in determining whether or not the hypotheses are true or false.

The research design is usually incorporated into the introduction of your paper . You can obtain an overall sense of what to do by reviewing studies that have utilized the same research design [e.g., using a case study approach]. This can help you develop an outline to follow for your own paper.

NOTE: Use the SAGE Research Methods Online and Cases and the SAGE Research Methods Videos databases to search for scholarly resources on how to apply specific research designs and methods . The Research Methods Online database contains links to more than 175,000 pages of SAGE publisher's book, journal, and reference content on quantitative, qualitative, and mixed research methodologies. Also included is a collection of case studies of social research projects that can be used to help you better understand abstract or complex methodological concepts. The Research Methods Videos database contains hours of tutorials, interviews, video case studies, and mini-documentaries covering the entire research process.

Creswell, John W. and J. David Creswell. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches . 5th edition. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2018; De Vaus, D. A. Research Design in Social Research . London: SAGE, 2001; Gorard, Stephen. Research Design: Creating Robust Approaches for the Social Sciences . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2013; Leedy, Paul D. and Jeanne Ellis Ormrod. Practical Research: Planning and Design . Tenth edition. Boston, MA: Pearson, 2013; Vogt, W. Paul, Dianna C. Gardner, and Lynne M. Haeffele. When to Use What Research Design . New York: Guilford, 2012.

Action Research Design

Definition and Purpose

The essentials of action research design follow a characteristic cycle whereby initially an exploratory stance is adopted, where an understanding of a problem is developed and plans are made for some form of interventionary strategy. Then the intervention is carried out [the "action" in action research] during which time, pertinent observations are collected in various forms. The new interventional strategies are carried out, and this cyclic process repeats, continuing until a sufficient understanding of [or a valid implementation solution for] the problem is achieved. The protocol is iterative or cyclical in nature and is intended to foster deeper understanding of a given situation, starting with conceptualizing and particularizing the problem and moving through several interventions and evaluations.

What do these studies tell you ?

- This is a collaborative and adaptive research design that lends itself to use in work or community situations.

- Design focuses on pragmatic and solution-driven research outcomes rather than testing theories.

- When practitioners use action research, it has the potential to increase the amount they learn consciously from their experience; the action research cycle can be regarded as a learning cycle.

- Action research studies often have direct and obvious relevance to improving practice and advocating for change.

- There are no hidden controls or preemption of direction by the researcher.

What these studies don't tell you ?

- It is harder to do than conducting conventional research because the researcher takes on responsibilities of advocating for change as well as for researching the topic.

- Action research is much harder to write up because it is less likely that you can use a standard format to report your findings effectively [i.e., data is often in the form of stories or observation].

- Personal over-involvement of the researcher may bias research results.

- The cyclic nature of action research to achieve its twin outcomes of action [e.g. change] and research [e.g. understanding] is time-consuming and complex to conduct.

- Advocating for change usually requires buy-in from study participants.

Coghlan, David and Mary Brydon-Miller. The Sage Encyclopedia of Action Research . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2014; Efron, Sara Efrat and Ruth Ravid. Action Research in Education: A Practical Guide . New York: Guilford, 2013; Gall, Meredith. Educational Research: An Introduction . Chapter 18, Action Research. 8th ed. Boston, MA: Pearson/Allyn and Bacon, 2007; Gorard, Stephen. Research Design: Creating Robust Approaches for the Social Sciences . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2013; Kemmis, Stephen and Robin McTaggart. “Participatory Action Research.” In Handbook of Qualitative Research . Norman Denzin and Yvonna S. Lincoln, eds. 2nd ed. (Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE, 2000), pp. 567-605; McNiff, Jean. Writing and Doing Action Research . London: Sage, 2014; Reason, Peter and Hilary Bradbury. Handbook of Action Research: Participative Inquiry and Practice . Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE, 2001.

Case Study Design

A case study is an in-depth study of a particular research problem rather than a sweeping statistical survey or comprehensive comparative inquiry. It is often used to narrow down a very broad field of research into one or a few easily researchable examples. The case study research design is also useful for testing whether a specific theory and model actually applies to phenomena in the real world. It is a useful design when not much is known about an issue or phenomenon.

- Approach excels at bringing us to an understanding of a complex issue through detailed contextual analysis of a limited number of events or conditions and their relationships.

- A researcher using a case study design can apply a variety of methodologies and rely on a variety of sources to investigate a research problem.

- Design can extend experience or add strength to what is already known through previous research.

- Social scientists, in particular, make wide use of this research design to examine contemporary real-life situations and provide the basis for the application of concepts and theories and the extension of methodologies.

- The design can provide detailed descriptions of specific and rare cases.

- A single or small number of cases offers little basis for establishing reliability or to generalize the findings to a wider population of people, places, or things.

- Intense exposure to the study of a case may bias a researcher's interpretation of the findings.

- Design does not facilitate assessment of cause and effect relationships.

- Vital information may be missing, making the case hard to interpret.

- The case may not be representative or typical of the larger problem being investigated.

- If the criteria for selecting a case is because it represents a very unusual or unique phenomenon or problem for study, then your interpretation of the findings can only apply to that particular case.