- Entertainment

- Environment

- Information Science and Technology

- Social Issues

Home Essay Samples Art

Essay Samples on Graffiti

Expressive art: is graffiti art or vandalism.

Throughout time graffiti has received both overwhelming support and intense backlash. Some view it as a form of expressive art while others consider it a complete destruction of property. However, despite the amount of differentiation, charisma and personality graffiti can bring into cities, it is...

- Visual Arts

Why Is Graffiti Are Not Vandalism

Why is graffiti art not vandalism? According to the Mural Arts Philadelphia website, the village’s first legitimate effort to eradicate graffiti started with the form of the Anti-Graffiti Network in the 1980s. Some people assay that its vandalism, and some assay that its artifice. Park...

Societal Views On Graffiti: Street Art Or Vandalism

When you think of graffiti what’s the first thing that comes to mind? Vandalism or street art? Most would say vandalism, but what makes the distinction between the two? The intention of the piece. There’s a difference between defiling the back of a building and...

Graffiti And Street Art As An Act Of Vandalism

It is difficult to apply a single definition to what is considered Art. Whether it can or should be defined has been constantly debated. “The definition of art is controversial in contemporary philosophy. Whether art can be defined has also been a matter of controversy....

Exit Through the Gift Shop: Popularising the Art of Graffiti

I believe that posting a form repeatedly is a form of artistic expression in the beginning. Once people relate it to something or make a meaning out of it, it might become a brand or a logo. Making the art is as equally as important...

- Exit Through The Gift Shop

Stressed out with your paper?

Consider using writing assistance:

- 100% unique papers

- 3 hrs deadline option

Analysis of the Concept of Street Art in Martin Irvine's Article: The Work On The Street: Street Art and Visual Culture

In the article, The Work On The Street: Street Art and Visual Culture, by Martin Irvine, he gives a better interpretation of the concept of street art, while distinguishing major aspects of visual culture. To start off, Irvine provides a definition of street art noting,...

Street Art in Modern Culture: Presenting Own Message to the Wide Audience

Street art is visual art created in public locations, usually unsanctioned artwork executed outside of the context of traditional art venues. Other terms for this type of art include 'independent public art', 'post-graffiti', and 'neo-graffiti', and is closely related with guerrilla art. Common forms and...

Reasons Why Graffiti Can't Be Considered a Form of Art

Graffiti has always been a issue of controversy in our society as there are endless debates happening all over the world whether or not it should be categorized as a form of art. Drawing, painting, printing, design, sculpture, printmaking and photography all encompass the category...

- Controversial Issue

Graffiti: A Form of Art or Crime

Graffiti is a highly controversial form of art which is considered illegal in several places, punishable by law whereas on the other hand some people term it as an innovative way of expressing creativity, freedom of speech and political awakening. This art indeed is a...

Graffiti Art in the Philippines: Reflection of Social Issues in the Philippines

In the Philippines, people are known to be artistic and creative in different aspects of life. Even at the earliest time, these characteristics were reflected in the different remnants of the existence of humankind. Angono Petroglyphs was known as one of the earliest artworks in...

- Philippines

- Social Problems

Jean-Michel Basquiat's Neo-Expressionism Art

Jean-Michel Basquiat is famously known as the gritty on the New York street became known from the 'Punk'. The street-smart graffiti artist has successively covered the international art gallery route starting his journey from the dark lane of downtown. In a small number of fast-paced...

- Jean-Michel Basquiat

Life and Artist Way of Jean-Michel Basquiat

A high school dropout, a panhandler, not a real person, but a legend. From sleeping on park benches, to becoming a featured artist of renowned art galleries, Jean Michel Basquiat managed to achieve more in his short, 8-year long career, than most artists do in...

Unique Art Style of Jean-Michel Basquiat

Jean Michel Basquiat was an American artist he also happened to be one of the top-selling American artists. Some of his paintings sold for prices of to $57.5 million and they were all unique and they had some way of portraying current issues. Jean is...

Graffiti: The Discussion on Whether It Is an Art or an Act of Vandalism

Graffiti, is it art? Or Vandalism? In most countries painting property without the property owner's permission is considered vandalism, which is a punishable crime, yet at the same time, many cities are put on the map because of their street art. These cities, like Buenos...

Vandalism and Vandalistic Photography in the Work of Martha Cooper and Jürgen Große

Google defines the act of vandalism as an “action involving deliberate destruction of or damage to public or private property.” Photography and its influencers have changed the idea of vandalistic photography over many years. This idea is vividly seen through, such artists as Martha Cooper,...

- Photography

Best topics on Graffiti

1. Expressive Art: Is Graffiti Art Or Vandalism

2. Why Is Graffiti Are Not Vandalism

3. Societal Views On Graffiti: Street Art Or Vandalism

4. Graffiti And Street Art As An Act Of Vandalism

5. Exit Through the Gift Shop: Popularising the Art of Graffiti

6. Analysis of the Concept of Street Art in Martin Irvine’s Article: The Work On The Street: Street Art and Visual Culture

7. Street Art in Modern Culture: Presenting Own Message to the Wide Audience

8. Reasons Why Graffiti Can’t Be Considered a Form of Art

9. Graffiti: A Form of Art or Crime

10. Graffiti Art in the Philippines: Reflection of Social Issues in the Philippines

11. Jean-Michel Basquiat’s Neo-Expressionism Art

12. Life and Artist Way of Jean-Michel Basquiat

13. Unique Art Style of Jean-Michel Basquiat

14. Graffiti: The Discussion on Whether It Is an Art or an Act of Vandalism

15. Vandalism and Vandalistic Photography in the Work of Martha Cooper and Jürgen Große

- Frida Kahlo

- Ansel Adams

- Impressionism

- Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Pablo Picasso

- Andy Warhol

- Michelangelo

Need writing help?

You can always rely on us no matter what type of paper you need

*No hidden charges

100% Unique Essays

Absolutely Confidential

Money Back Guarantee

By clicking “Send Essay”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement. We will occasionally send you account related emails

You can also get a UNIQUE essay on this or any other topic

Thank you! We’ll contact you as soon as possible.

- Skip to main content

- Skip to main navigation

- Awards & Honors

- News by topic

- News archives

- E-Newsletter

- Tuesday Newsday

- UCSC Magazine

- Administrative Messages

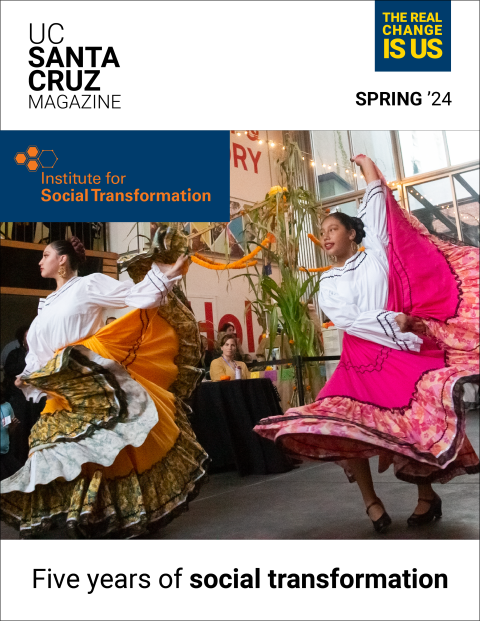

Home / 2021 / September / The writing on the wall: exploring the cultural value of graffiti and street art

The writing on the wall: exploring the cultural value of graffiti and street art

Doctoral candidate’s research interprets graffiti’s deeper meaning among Latinx and Black urban subcultures in Los Angeles

September 14, 2021

By Allison Arteaga Soergel

Ismael Illescas grew up admiring the graffiti around his neighborhood in Los Angeles. He had migrated to the city with his mother and brother from Ecuador in the 1990s as part of a large Latin American diaspora. In his urban environment, he found himself surrounded by beautiful, cryptic messages. They were written on walls and scrawled daringly across billboards. Little by little, he began to understand the meanings behind some of these messages. And, eventually, he started writing back.

Illescas became a graffiti writer himself, for a time. He has since given it up, but he never lost his initial sense of curiosity and admiration. In fact, now, as a doctoral candidate in Latin American and Latino Studies, his dissertation research has taken him back to Los Angeles, where he gathered insights from current and former graffiti writers about how their work connects with concepts of art, identity, culture, and space.

For those who create it, graffiti is an expression of identity and an outlet for creativity, social connection, and achievement, according to Illescas’s research. Some of the most popular graffiti yards in Los Angeles are abandoned spaces in communities of color that neither the economy nor the city has been willing to invest in, he says. But graffiti allows Black and Latino young men to transform these areas into spaces of congregation and empowerment.

“In a city where these youth are marginalised, ostracized, and invisibilized, graffiti is a way for them to become visible,” Illescas said. “They feel that the system is against them, and upward social mobility is limited for them, so putting their names up around the city is a way for them to achieve respect from their peers and assert their dignity, and that doesn’t come easily from other places and institutions in society.”

Graffiti also offers what Illescas calls an “illicit cartography,” meaning that it can be read like a cultural map of the city. Graffiti styles in East Los Angeles, for example, reflect Mexican-American artistic influence that began with Pachuco counterculture in the 1940s. Rich graffiti writing traditions emerged, including “placas,” or tags that list a writer’s stylized signature, and “barrio calligraphy,” which blends rolling scripts with Old English lettering. In the 1980s, those traditions then incorporated colorful, whimsical East Coast influences.

“The result is that Los Angeles has a really unique graffiti style,” Illescas said. “Although outsiders might not necessarily notice it, you can easily see the Mexican-American artistic influence in the aesthetics, and that has become associated with Latinx urban identities.”

Graffiti is a multiracial and multi-ethnic subculture, and Illescas says his research aims to recognize the specific contributions of Black and Latinx communities. He’s also critically examining the subculture’s hypermasculinity and how that may limit its transformative potential. And he’s particularly interested in shedding light on how race may affect public perceptions of graffiti.

Depending on the context, graffiti can either be publicly admired as “street art”—and valued up to millions of dollars—or it can be criminalized at levels ranging up to felony charges and years of jail time. In Los Angeles, a city which many researchers consider to be highly racially segregated, Black and Latinx communities, like South Central Los Angeles and East Los Angeles, are the places where graffiti is most likely to be severely criminalized and lumped together with gang activity, Illescas says.

Meanwhile, Illescas says street art is more likely to be recognized as such within arts districts, where officially sanctioned “beautification” projects use public art to attract more business and new residents, which can contribute to gentrification issues. And some of the most famous street artists are actually white men, like Banksy or Shepard Fairey, who have each attained international recognition for the artistic value of their illegal works.

“This is where systemic racism occurs,” Illescas said. “You have some people who are more prone to being criminalized and severely punished for a very similar act, and that punishment falls mainly on young Black and Latino men.”

For these reasons, Illescas has found that many graffiti writers of color have mixed feelings about the growing public appreciation for street art.

“On the one hand, it’s a capitalistic appropriation of transgressive graffiti into commercialized street art,” Illescas said. “But it also ties into the efforts of graffiti writers who have been pushing for years to decriminalize their art and demonstrate its artistic and social value and the types of knowledge that it brings with it.”

Street art has, in fact, already brought opportunities for some veteran Black and Latino graffiti writers, who told Illescas they had recently been commissioned for their art or had found jobs as tour guides in arts districts. But each of these artists got their start creating illegal graffiti tags. Illescas believes that decriminalization will ultimately require transforming public appreciation of street art into a deeper understanding of the expressive value of other forms of graffiti. And he hopes his research might aid in that process.

“The graffiti that we see up in the streets may seem like an insignificant tag or scribble to some people, but there’s a lot of meaning behind it,” he said. “There needs to be a recognition that graffiti is actually a visual representation of someone’s identity, and it’s also potentially their starting point to a very meaningful artistic career.”

University News

- University News Home

- Monthly Newsletter

Other News & Events

- Campus Calendars

- UCSC Chancellor

- Press Releases

- Contacts for Reporters

- Send us an email

- Report an accessibility barrier

- Land Acknowledgment

- Accreditation

Last modified: September 16, 2021 195.158.225.230

Analysis of Cultural Phenomenon of Graffiti Essay

- To find inspiration for your paper and overcome writer’s block

- As a source of information (ensure proper referencing)

- As a template for you assignment

Introduction

Causing troubles, gives voices to the youth, aesthetic appeal of graffiti.

Bibliography

Many of the great works of art were underestimated by the contemporaries of the artists. Though the artistic value of the graffiti remains questionable for most cultural experts, certain samples of spray-painting may be regarded the works of art in the context of the hip-hop culture.

Causing a lot of troubles and material damage to the authorities, graffiti is considered to be a property crime punishable by up to one year in jail in Seattle and up to three years in Singapore, for instance. For replacing the spray-paintings a lot of funds as well as human resources are used. Notwithstanding the ethical code of the artists, the windows and walls in the public spaces are often used as canvases for graffiti. Considering only the material damage issue of the graffiti phenomenon, it may be treated as an act of vandalism.

By the way, spray-painting in the public areas, in my opinion, is mostly meant to contradict the generally accepted norms and expresses the protest of the young generation, looking for ways of self-realization and socialization. Assessing the artistic value of these masterpieces is problematic. But some artists consciously choose the unused dessert areas for their self-expression and it causes less damage than painting in public places, changing the city landscapes and amusing the occasional observers. Taking into consideration the individual style of every artist and interesting motifs used in the graffiti, this phenomenon is to be treated as one of the trends of contemporary hip-hop culture.

Becoming a worldwide trend, paint-spraying increased its significance in the cultural context. Numerous websites unite artists all over the world, sharing their experiences, demonstrating samples of the wall masterpieces. Being prohibited by law and painted mostly during the hours of darkness, this kind of self-expression creates the atmosphere of romanticism and gives inspiration to the artists. I consider graffiti to be a cultural phenomenon due to its artistic value and on the condition that that opposition to the generally accepted norms is not an end in itself while creating separate paintings, they may be regarded the works of art.

Graffiti gives voices to the youth and often represents the young people’s attitude to the moral norms and the picture of the life of this community. Taking into consideration the widespread trend and wide range of artists, it is important to differentiate between the gang artists and the tagging, between acts of vandalism while painting in public places and painting in the desert or unused areas and especially on the canvas. Occurred as the way of self-expression for the loafing about teenagers, the frames of the trend were changed and now it is problematic to give the well-defined estimation of the phenomenon.

Mohammad Qarni, a young artist, explains his liking for graffiti: “It was a way of showing off and of proving ourselves” (Ambah 2). Ed Hardy, another young man illuminates the sociological issue of the creation: “Graffiti gave cachet and made it easier to meet girls” (Ambah 2). I think, that the main reason for graffiti to be so widespread is the excitement arousing from the circumstances of its creation. Realizing that it is prohibited by law but will be inevitably observed by numerous occasional passersby inspire the artists. In other words, graffiti became the forbidden fruit that is sweetest.

Not every inscription on the wall may be regarded a graffiti, a good graffiti can be estimated according to its aesthetic appeal to the viewers. There are hardly any strict norms of aesthetics that can be observed in graffiti; most of the samples have an individual style of the creator, though certain features, such as bubble letters, for example, are met in numerous paintings. Different tests may be used as the basis for the painting, such as political statements, different slogans, the name, or the nickname of the artist.

The latter case is named tagging, writing one’s name on the walls of the city has psychological roots, tagging is aimed at creating as many similar paintings as it is possible to become recognized by the viewers. Successful paint-spraying requires thorough preparation. Not to mention the necessity of hiding while painting, it needs to be well-organized and take not too much time, though some of the elements of the inscription are not easy at all. That is why the young artists start withdrawing their names on a sheet of paper, choosing the style for a would-be graffiti. A work of art differs from the act of vandalism in its aesthetic value and requires the skills and perspiration of the artists.

The way to recognition graffiti as a cultural phenomenon was not an easy one. One of the first significant events may be regarded the documentary film Style Wars by Tony Silver and Henry Chalfant, which was made in New York in 1983. The producers were the entrepreneurs, raising the question of the aesthetic value of the paintings, which were regarded acts of vandalism, for the first time.

It was the first time that the names of the graffiti artists, were mentioned. Not so long ago one of the mentioned film artists, Daze became a pioneer in exhibiting his canvases in Singapore and other cities. The paintings replaced from the city walls to the canvases remain the same style and spirit but lack the romanticism of the wall creativity. It is said that being legalized graffiti may be deprived of its original charm. But I consider the paintings on the canvases to be the next stage in the development of graffiti, a more civilized one, while the question of vandalism is not to be raised anymore.

Graffiti is a significant phenomenon of hip-hop culture. Originated as the way for the self-expression of the teenagers, it became widespread and more civilized, while its aesthetic value, changing the landscapes of the cities, was appreciated by the public opinion.

Ambah, Faiza. Graffiti Give Voice to Saudi Youth. The Seattle Times . 2007: 1 – 3.

- The Hip-Hop Genre Origin and Influence

- Aspects of Graffiti as Art Therapy

- Analyzing Graffiti as a Subculture

- Art and Literature in African-americans Diaspora

- Ornament and Crime: Economic Aspects

- Semiology Usefulness in Analyzing Works of Art or Design

- Colonialism in the Work of Some Artists

- Judgment and Social Interaction in “The Lady Justice”

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2021, December 19). Analysis of Cultural Phenomenon of Graffiti. https://ivypanda.com/essays/cultural-phenomenon-of-graffiti/

"Analysis of Cultural Phenomenon of Graffiti." IvyPanda , 19 Dec. 2021, ivypanda.com/essays/cultural-phenomenon-of-graffiti/.

IvyPanda . (2021) 'Analysis of Cultural Phenomenon of Graffiti'. 19 December.

IvyPanda . 2021. "Analysis of Cultural Phenomenon of Graffiti." December 19, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/cultural-phenomenon-of-graffiti/.

1. IvyPanda . "Analysis of Cultural Phenomenon of Graffiti." December 19, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/cultural-phenomenon-of-graffiti/.

IvyPanda . "Analysis of Cultural Phenomenon of Graffiti." December 19, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/cultural-phenomenon-of-graffiti/.

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- How to conclude an essay | Interactive example

How to Conclude an Essay | Interactive Example

Published on January 24, 2019 by Shona McCombes . Revised on July 23, 2023.

The conclusion is the final paragraph of your essay . A strong conclusion aims to:

- Tie together the essay’s main points

- Show why your argument matters

- Leave the reader with a strong impression

Your conclusion should give a sense of closure and completion to your argument, but also show what new questions or possibilities it has opened up.

This conclusion is taken from our annotated essay example , which discusses the history of the Braille system. Hover over each part to see why it’s effective.

Braille paved the way for dramatic cultural changes in the way blind people were treated and the opportunities available to them. Louis Braille’s innovation was to reimagine existing reading systems from a blind perspective, and the success of this invention required sighted teachers to adapt to their students’ reality instead of the other way around. In this sense, Braille helped drive broader social changes in the status of blindness. New accessibility tools provide practical advantages to those who need them, but they can also change the perspectives and attitudes of those who do not.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

Step 1: return to your thesis, step 2: review your main points, step 3: show why it matters, what shouldn’t go in the conclusion, more examples of essay conclusions, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about writing an essay conclusion.

To begin your conclusion, signal that the essay is coming to an end by returning to your overall argument.

Don’t just repeat your thesis statement —instead, try to rephrase your argument in a way that shows how it has been developed since the introduction.

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

Next, remind the reader of the main points that you used to support your argument.

Avoid simply summarizing each paragraph or repeating each point in order; try to bring your points together in a way that makes the connections between them clear. The conclusion is your final chance to show how all the paragraphs of your essay add up to a coherent whole.

To wrap up your conclusion, zoom out to a broader view of the topic and consider the implications of your argument. For example:

- Does it contribute a new understanding of your topic?

- Does it raise new questions for future study?

- Does it lead to practical suggestions or predictions?

- Can it be applied to different contexts?

- Can it be connected to a broader debate or theme?

Whatever your essay is about, the conclusion should aim to emphasize the significance of your argument, whether that’s within your academic subject or in the wider world.

Try to end with a strong, decisive sentence, leaving the reader with a lingering sense of interest in your topic.

The easiest way to improve your conclusion is to eliminate these common mistakes.

Don’t include new evidence

Any evidence or analysis that is essential to supporting your thesis statement should appear in the main body of the essay.

The conclusion might include minor pieces of new information—for example, a sentence or two discussing broader implications, or a quotation that nicely summarizes your central point. But it shouldn’t introduce any major new sources or ideas that need further explanation to understand.

Don’t use “concluding phrases”

Avoid using obvious stock phrases to tell the reader what you’re doing:

- “In conclusion…”

- “To sum up…”

These phrases aren’t forbidden, but they can make your writing sound weak. By returning to your main argument, it will quickly become clear that you are concluding the essay—you shouldn’t have to spell it out.

Don’t undermine your argument

Avoid using apologetic phrases that sound uncertain or confused:

- “This is just one approach among many.”

- “There are good arguments on both sides of this issue.”

- “There is no clear answer to this problem.”

Even if your essay has explored different points of view, your own position should be clear. There may be many possible approaches to the topic, but you want to leave the reader convinced that yours is the best one!

- Argumentative

- Literary analysis

This conclusion is taken from an argumentative essay about the internet’s impact on education. It acknowledges the opposing arguments while taking a clear, decisive position.

The internet has had a major positive impact on the world of education; occasional pitfalls aside, its value is evident in numerous applications. The future of teaching lies in the possibilities the internet opens up for communication, research, and interactivity. As the popularity of distance learning shows, students value the flexibility and accessibility offered by digital education, and educators should fully embrace these advantages. The internet’s dangers, real and imaginary, have been documented exhaustively by skeptics, but the internet is here to stay; it is time to focus seriously on its potential for good.

This conclusion is taken from a short expository essay that explains the invention of the printing press and its effects on European society. It focuses on giving a clear, concise overview of what was covered in the essay.

The invention of the printing press was important not only in terms of its immediate cultural and economic effects, but also in terms of its major impact on politics and religion across Europe. In the century following the invention of the printing press, the relatively stationary intellectual atmosphere of the Middle Ages gave way to the social upheavals of the Reformation and the Renaissance. A single technological innovation had contributed to the total reshaping of the continent.

This conclusion is taken from a literary analysis essay about Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein . It summarizes what the essay’s analysis achieved and emphasizes its originality.

By tracing the depiction of Frankenstein through the novel’s three volumes, I have demonstrated how the narrative structure shifts our perception of the character. While the Frankenstein of the first volume is depicted as having innocent intentions, the second and third volumes—first in the creature’s accusatory voice, and then in his own voice—increasingly undermine him, causing him to appear alternately ridiculous and vindictive. Far from the one-dimensional villain he is often taken to be, the character of Frankenstein is compelling because of the dynamic narrative frame in which he is placed. In this frame, Frankenstein’s narrative self-presentation responds to the images of him we see from others’ perspectives. This conclusion sheds new light on the novel, foregrounding Shelley’s unique layering of narrative perspectives and its importance for the depiction of character.

If you want to know more about AI tools , college essays , or fallacies make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples or go directly to our tools!

- Ad hominem fallacy

- Post hoc fallacy

- Appeal to authority fallacy

- False cause fallacy

- Sunk cost fallacy

College essays

- Choosing Essay Topic

- Write a College Essay

- Write a Diversity Essay

- College Essay Format & Structure

- Comparing and Contrasting in an Essay

(AI) Tools

- Grammar Checker

- Paraphrasing Tool

- Text Summarizer

- AI Detector

- Plagiarism Checker

- Citation Generator

Your essay’s conclusion should contain:

- A rephrased version of your overall thesis

- A brief review of the key points you made in the main body

- An indication of why your argument matters

The conclusion may also reflect on the broader implications of your argument, showing how your ideas could applied to other contexts or debates.

For a stronger conclusion paragraph, avoid including:

- Important evidence or analysis that wasn’t mentioned in the main body

- Generic concluding phrases (e.g. “In conclusion…”)

- Weak statements that undermine your argument (e.g. “There are good points on both sides of this issue.”)

Your conclusion should leave the reader with a strong, decisive impression of your work.

The conclusion paragraph of an essay is usually shorter than the introduction . As a rule, it shouldn’t take up more than 10–15% of the text.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, July 23). How to Conclude an Essay | Interactive Example. Scribbr. Retrieved July 10, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/academic-essay/conclusion/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, how to write an essay introduction | 4 steps & examples, how to write a thesis statement | 4 steps & examples, example of a great essay | explanations, tips & tricks, "i thought ai proofreading was useless but..".

I've been using Scribbr for years now and I know it's a service that won't disappoint. It does a good job spotting mistakes”

- Link to facebook

- Link to linkedin

- Link to twitter

- Link to youtube

- Writing Tips

How to Write an Argumentative Essay

4-minute read

- 30th April 2022

An argumentative essay is a structured, compelling piece of writing where an author clearly defines their stance on a specific topic. This is a very popular style of writing assigned to students at schools, colleges, and universities. Learn the steps to researching, structuring, and writing an effective argumentative essay below.

Requirements of an Argumentative Essay

To effectively achieve its purpose, an argumentative essay must contain:

● A concise thesis statement that introduces readers to the central argument of the essay

● A clear, logical, argument that engages readers

● Ample research and evidence that supports your argument

Approaches to Use in Your Argumentative Essay

1. classical.

● Clearly present the central argument.

● Outline your opinion.

● Provide enough evidence to support your theory.

2. Toulmin

● State your claim.

● Supply the evidence for your stance.

● Explain how these findings support the argument.

● Include and discuss any limitations of your belief.

3. Rogerian

● Explain the opposing stance of your argument.

● Discuss the problems with adopting this viewpoint.

● Offer your position on the matter.

● Provide reasons for why yours is the more beneficial stance.

● Include a potential compromise for the topic at hand.

Tips for Writing a Well-Written Argumentative Essay

● Introduce your topic in a bold, direct, and engaging manner to captivate your readers and encourage them to keep reading.

● Provide sufficient evidence to justify your argument and convince readers to adopt this point of view.

● Consider, include, and fairly present all sides of the topic.

● Structure your argument in a clear, logical manner that helps your readers to understand your thought process.

Find this useful?

Subscribe to our newsletter and get writing tips from our editors straight to your inbox.

● Discuss any counterarguments that might be posed.

● Use persuasive writing that’s appropriate for your target audience and motivates them to agree with you.

Steps to Write an Argumentative Essay

Follow these basic steps to write a powerful and meaningful argumentative essay :

Step 1: Choose a topic that you’re passionate about

If you’ve already been given a topic to write about, pick a stance that resonates deeply with you. This will shine through in your writing, make the research process easier, and positively influence the outcome of your argument.

Step 2: Conduct ample research to prove the validity of your argument

To write an emotive argumentative essay , finding enough research to support your theory is a must. You’ll need solid evidence to convince readers to agree with your take on the matter. You’ll also need to logically organize the research so that it naturally convinces readers of your viewpoint and leaves no room for questioning.

Step 3: Follow a simple, easy-to-follow structure and compile your essay

A good structure to ensure a well-written and effective argumentative essay includes:

Introduction

● Introduce your topic.

● Offer background information on the claim.

● Discuss the evidence you’ll present to support your argument.

● State your thesis statement, a one-to-two sentence summary of your claim.

● This is the section where you’ll develop and expand on your argument.

● It should be split into three or four coherent paragraphs, with each one presenting its own idea.

● Start each paragraph with a topic sentence that indicates why readers should adopt your belief or stance.

● Include your research, statistics, citations, and other supporting evidence.

● Discuss opposing viewpoints and why they’re invalid.

● This part typically consists of one paragraph.

● Summarize your research and the findings that were presented.

● Emphasize your initial thesis statement.

● Persuade readers to agree with your stance.

We certainly hope that you feel inspired to use these tips when writing your next argumentative essay . And, if you’re currently elbow-deep in writing one, consider submitting a free sample to us once it’s completed. Our expert team of editors can help ensure that it’s concise, error-free, and effective!

Share this article:

Post A New Comment

Got content that needs a quick turnaround? Let us polish your work. Explore our editorial business services.

9-minute read

How to Use Infographics to Boost Your Presentation

Is your content getting noticed? Capturing and maintaining an audience’s attention is a challenge when...

8-minute read

Why Interactive PDFs Are Better for Engagement

Are you looking to enhance engagement and captivate your audience through your professional documents? Interactive...

7-minute read

Seven Key Strategies for Voice Search Optimization

Voice search optimization is rapidly shaping the digital landscape, requiring content professionals to adapt their...

Five Creative Ways to Showcase Your Digital Portfolio

Are you a creative freelancer looking to make a lasting impression on potential clients or...

How to Ace Slack Messaging for Contractors and Freelancers

Effective professional communication is an important skill for contractors and freelancers navigating remote work environments....

3-minute read

How to Insert a Text Box in a Google Doc

Google Docs is a powerful collaborative tool, and mastering its features can significantly enhance your...

Make sure your writing is the best it can be with our expert English proofreading and editing.

Essay on Graffiti

Students are often asked to write an essay on Graffiti in their schools and colleges. And if you’re also looking for the same, we have created 100-word, 250-word, and 500-word essays on the topic.

Let’s take a look…

100 Words Essay on Graffiti

What is graffiti.

Graffiti is writing or drawings made on walls or other surfaces, usually without permission. It can be simple written words or elaborate paintings. Some people see it as art, while others view it as vandalism. This form of expression has been around for centuries, with examples dating back to ancient civilizations.

Types of Graffiti

There are many types of graffiti. Tagging is the simplest, involving the writer’s name or symbol. More complex styles include pieces, which are large, colorful works. Some artists use graffiti to spread social or political messages.

Graffiti and the Law

In many places, creating graffiti is illegal because it can damage property. When done without consent, it is considered vandalism. But some cities offer legal walls where artists can showcase their work without breaking the law.

Graffiti as Art

Graffiti has gained recognition as a form of art. Museums and galleries sometimes display graffiti as part of exhibitions. Many graffiti artists have become famous, blurring the lines between street art and traditional art.

Graffiti’s Impact

Graffiti can brighten dull spaces and give voice to those who feel unheard. It influences fashion, music, and culture. Despite its controversy, graffiti remains a powerful tool for self-expression and creativity in urban environments.

250 Words Essay on Graffiti

Graffiti is a type of art that is often seen on walls, bridges, and trains. It is made by writing or drawing directly on surfaces in public places. While some people think of it as a way to express themselves, others see it as damage or unwanted marks on property.

History of Graffiti

The practice of graffiti has been around for a very long time. Even ancient people in Egypt and Rome wrote on walls. In modern times, graffiti became more popular in the 1970s in New York City. It started with names or “tags” and grew into large and colorful pictures.

Many artists use graffiti to create beautiful and meaningful pieces. These can be very big and bright, and they often share a message or a story. Some famous artists, like Banksy, have made graffiti that is worth a lot of money and is shown in galleries.

In many places, making graffiti on someone else’s property without permission is against the law. This is because it can be hard to remove and may not be what the owner wants. But, some cities have special areas where artists can legally make graffiti.

In conclusion, graffiti is a form of art that can be both creative and controversial. While it lets artists share their thoughts and talents, it can also lead to legal issues. Understanding both sides of graffiti is important in appreciating its place in our world.

500 Words Essay on Graffiti

There are different kinds of graffiti. ‘Tags’ are like an artist’s signature; they are simple and quick to make. ‘Throw-ups’ are larger and might have two or three colors. They are usually bubble letters or simple shapes. The most complex type is a ‘piece’, short for masterpiece. These are big, detailed, and colorful. They take a lot of time and skill to make.

In many places, it’s against the law to make graffiti on someone else’s property without their permission. This is because it can damage the property and it might cost a lot of money to clean up. Some people see graffiti as vandalism, which is when someone breaks or ruins something on purpose. Yet, in some cities, there are walls or areas where artists can make graffiti legally.

A lot of people argue about whether graffiti is truly art. Some say it’s just messing up places and not real art. But others think it’s a way for artists who might not have another way to share their talent. In fact, some graffiti artists have become famous and now show their work in galleries or get paid to make murals. Murals are big pictures painted on walls, and they can make a dull place look really exciting.

Graffiti’s Impact on Society

Graffiti can change how a place looks and feels. If there’s a lot of it in one area, it might make the place look uncared for. But sometimes, it adds beauty to a boring wall or tells a story about the people who live there. Graffiti can also give a voice to people who feel they’re not being heard. It can be a way to protest or to bring attention to important issues.

Graffiti Around the World

All over the world, cities have different kinds of graffiti. In some places, it’s a big part of the culture and attracts tourists. For example, in cities like Berlin, Melbourne, and New York, people go on tours just to see the graffiti. Some cities even have festivals where artists come to make new pieces, and everyone can watch and enjoy the process.

If you’re looking for more, here are essays on other interesting topics:

Apart from these, you can look at all the essays by clicking here .

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Advertisement

Criminal but Beautiful: A Study on Graffiti and the Role of Value Judgments and Context in Perceiving Disorder

- Open access

- Published: 10 September 2015

- Volume 22 , pages 107–125, ( 2016 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Gabry Vanderveen 1 &

- Gwen van Eijk 2

54k Accesses

50 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Annoying paintings everywhere, [it] should be forbidden, and the perpetrators [should] clean everything with a toothbrush. It is pollution. There is an exception, what happens in cities, a boring wall is embellished with a nice painting made by experienced professional artists.

Introduction

The citation above, of a participant in our study who describes his first image of graffiti that comes to mind, summarizes our argument: public opinions on disorder (graffiti, in this case) may vary considerably, not only between people but people themselves make different judgments, depending on what they see in which context. Indeed, studies prove that ‘graffiti has been called everything from urban blight to artistic expression’ (Gomez 1993 : 634). Lombard ( 2012 ) calls graffiti ‘art crimes’ because it is criminal and artistic at the same time, which makes it also difficult to distinguish ‘artists’ from ‘criminals’. Even graffiti writers recognize that graffiti, while for them in the first place art, in some contexts is damaging or inappropriate (Rowe and Hutton 2012 ). According to Brighenti, graffiti is an ‘interstitial practice’: a practice about which different actors hold different conceptions, depending on how it is related to other practices such as ‘art and design (as aesthetic work), criminal law (as vandalism crime), politics (as a message of resistance and liberation), and market (as merchandisable product)’ ( 2010 : 316). A response to an interstitial practice always comes in a ‘yes, but’ form: graffiti is crime, or art — but it is always also something else (ibid.). Therefore, White ( 2000 : 253) argues, we should not condemn, nor celebrate graffiti, without considering ‘the ambiguities inherent in its various manifestations’.

Graffiti comes in many forms, varying from tag graffiti to artistic pieces and stencil art, and from illegal sprayings on public or private property to murals on legally designated walls. Our perspective is that there is no clear-cut distinction between graffiti and street art and that definitions based on form (e.g. tag, mural) cross legal definitions — the works of the (in)famous writer Banksy illustrate this point (Banksy’s work is often illegal but his work has also been sold and has featured in exhibitions, for example alongside Andy Warhol). Graffiti can be problematic, but not all graffiti is. The question as to when and why which forms of graffiti are perceived as criminal and by whom, remains an open question.

Yet, authorities, and many criminologists as well, tend to see graffiti as an unambiguous signal of disorder or even crime. Informed by the broken windows theory, many local governments seek to prevent and remove graffiti (e.g. Snyder 2006 ; Young 2010 ; Kramer 2010a ; Tempfli 2012 ; Uittenbogaard and Ceccato 2014 ). Studies in the tradition of the broken windows theory and social disorganization theory seem to assume that the public more or less agrees on what phenomena are ‘disorder’, and graffiti would be one of such phenomena. In this line of argument, ‘disorder’ would trigger fear (Ross and Jang 2000 ; Xu et al. 2005 ), undermine collective efficacy (Sampson et al. 1997 ; Kleinhans and Bolt 2013 ) and invite crime (Wilson and Kelling 1982 ; Wagers et al. 2008 ).

Our study engages with and critiques this line of argument in two ways. First, we observe that there has been much less attention for diverging (and conflicting) interpretations among the public. Many studies point at the mismatch of interpretations of graffiti as either art or crime between writers on the one hand and authorities, (supposedly) reflecting the concerns of the public, on the other hand (Whitford 1991 ; Gomez 1993 ; Halsey and Young 2006 ; Millie 2008 ; Snyder 2006 ; Dickinson 2008 ; Edwards 2009 ; Lombards 2012 ; McAuliffe 2012 ; Young 2012 ; Haworth et al. 2013 ). Indeed, we would expect that the perspective of graffiti writers differs from the perspective of the public (Brighenti 2010 ), as the underlying meaning and subcultural codes of graffiti are unknown to the average street user (Ferrell 2009 ; Young 2012 ). It is assumed that the uninformed public, as well as authorities and media, cannot distinguish one form of graffiti from another, thus interpreting all graffiti as evidence of increased gang activity, young people’s disrespect for authority or a threat to property values and neighbourhood safety (Ferrell 2009 ). However, in our study we show that opinions on disorder also vary significantly among the public. Based on qualitative and quantitative data we empirically unravel the different viewpoints on graffiti of the public in the Netherlands. Here we build on Millie’s ( 2011 ) work on value judgments in relation to criminalization.

Second, we elaborate insights on the role of context by examining judgments of graffiti in various micro places . Quantitative studies have generally examined context by focusing on the role of neighbourhood characteristics such as crime levels, population composition and stigma (e.g. Sampson and Raudenbush 1999 ; Franzini et al. 2008 ). We take a different approach and build on knowledge from mostly qualitative studies on context-related expectation and norms (e.g. Dixon et al. 2006 ; Cresswell 1996 ; Millie 2008 ). These studies draw our attention to the ways in which norms and expectations are tied to specific places, which together construct the meaning of places and of elements, such as graffiti, in those places. Using quantitative data, we investigate whether these ideas hold among a larger population (i.e. the Dutch public).

Studying responses to graffiti has broader relevance for research and policies on disorder, as graffiti is part of a larger ‘grey area’ of deviant behaviour that is not obviously criminal or harmful but nonetheless often labelled as ‘disorder’ (e.g. loitering, skateboarding, public drinking, noise). For example, following Jane Jacobs’ ( 1961 ) argument about the role of ‘eyes on the street’ in multifunctional neighbourhoods, people’s presence in the streets could contribute to safe street life and attract more people, but currently there is a tendency to see people hanging around in urban spaces as ‘social disorder’ (e.g. Ruggiero 2010 ; Binken and Blokland 2012 ). The same goes for public drinking: often banned in public space, but also tolerated when it contributes to the ‘aesthetic of the night-time economy’ (Dixon et al. 2006 ; Millie 2008 ). Particularly in the context of zero tolerance policies towards disorder, anti-social behaviour and incivilities, it is important to understand why and when behaviour is something that needs to be prevented, removed or punished. Critics of zero tolerance policies warn that in public space only certain behaviours from certain people are tolerated, while everything that deviates from the ‘mainstream’ is removed or excluded (e.g. Mitchell 2003 ; Beckett and Herbert 2008 ; MacLeod and Johnstone 2012 ). Diverging perspectives on disorder, graffiti included, lead to confusion about appropriate policy responses: if offensiveness is subjective, how can authorities discern what is acceptable and what is not? And to whom should authorities listen: to the majority, to those with most political or economic clout, or to more marginal groups who seem to struggle to enact their right to the city (Millie 2011 ; Kramer 2010a )? We return to these questions in the discussion. Before presenting our data, methods and results, we briefly discuss current trends in graffiti policy and criminological research on graffiti.

Graffiti as Art and/or Crime: Policy and Criminology

Even though ‘tough on graffiti’ approaches still dominate policies in countries such as Australia, the Netherlands, the UK and the US, the idea that the public responds in different ways to graffiti seems to be trickling down into policies, at least in some countries and cities. Repressive policies are concerned with preventing and removing graffiti, for example through applying special coatings and quickly removing all graffiti (e.g. Tempfli 2012 ; Uittenbogaard and Ceccato 2014 ). However, authorities have limited resources and thus need to prioritize which graffiti to remove first, which requires them to distinguish different types of graffiti (and for instance target offensive graffiti first, see Taylor et al. 2010 ; Vanderveen and Jelsma 2012 ). Moreover, local and national authorities do seem to distinguish between graffiti as a form of art and graffiti as crime, through mixing preventative and punitive measures with offering designated spaces for authorized graffiti (Kramer 2010b ; Lombard 2012 ; McAuliffe 2012 , 2013 ; Young 2010 ; Tempfli 2012 ). In some cities, graffiti (i.e. murals or pieces) is even used to prevent graffiti (Craw et al. 2006 ). Unwanted graffiti is in this way prevented and graffiti writers are offered alternatives. A bifurcated approach like this builds upon the idea that not all graffiti is received in the same way.

More generally, the way in which policy makers and citizens think about cities and a liveable urban environment is changing. Recent urban development seems to influence viewpoints on graffiti. Particularly the ‘creative city’ discourse offers opportunities to rethink the value of the creative practices of graffiti writers (McAuliffe 2012 ). Since Florida’s ( 2004 ) ‘recipe’ for successful cities (the 3 T’s in short: Technology, Tolerance and Talent — the latter T is measured by the share of people working in the creative sector), urban governments have promoted creativity in all forms and places to make their cities attractive. Indeed, in some places, graffiti in the form of murals is desired by policy makers to beautify locations and attract tourists (e.g. Millie 2011 ; Koster and Randall 2005 ; Zukin and Braslow 2011 ; McAuliffe 2012 ). However, city marketing may also result in a ‘get tough on graffiti approach’, as was the case in Melbourne in response to the run-up to the Commonwealth Games to be hosted in Melbourne in March 2006 (Young 2010 ). In London, authorities first painted over graffiti that mocked the Olympic Games and corporate sponsors, but recently commissioned graffiti as part of the Canals Project for East London’s waterways (Wainwright 2013 ). Such developments do not necessarily demonstrate a greater leniency towards graffiti. In the words of street artist Mau Mau: ‘when it suits them, they [the Council] choose who paints where’ (ibid.). So even when we may find that authorities are rethinking the meaning of graffiti, this is not necessarily applied to all graffiti in all places, which underscores our point that we need to consider responses to graffiti in relation to its form and context.

Given the ambiguity in how authorities deal with graffiti, we think it is striking that the dominant approach in criminological research on disorder views graffiti unambiguously as a social problem: something threatening that must be prevented and dealt with because it would cause fear and (more) crime. This idea is most common in studies following the ecological tradition (social disorganization theory) or the broken windows theory. Within ecological research, graffiti is often taken as an example of physical disorder (although it may also be seen as social disorder, see Skogan 1990 ), similar to other signs of physical disorder such as boarded-up houses, rubbish on the street and defaced bus stops. For example, in Wyant’s ( 2008 ) study on perceived incivilities and fear of crime, respondents were asked to indicate on a 4-point scale whether they thought various ‘neighbourhood problems’ capturing ‘perceived incivilities’ were a ‘serious problem’ in their neighbourhood, one of which is ‘graffiti on sidewalks and walls’ (see also, with varying questions or items: Ross and Jang 2000 ; Markowitz et al. 2001 ; Foster et al. 2010 ; Paquet et al. 2010 ; Gainey et al. 2011 ; Kleinhans and Bolt 2013 ).

Moreover, the broken windows theory suggests that graffiti and other signs of disorder in neighbourhoods cause not only fear but also crime, because fear would weaken social control and thus signal opportunities for crime to motivated offenders (Wilson and Kelling 1982 ; Wagers et al. 2008 ). A rare test of the assumed causal link between perceiving disorder and crime is the study of Keizer and colleagues ( 2008a ) which suggests that when people see norm transgression they are more likely to overstep a rule themselves. In one of the six field experiments, they demonstrate that in an environment with tag graffiti on a wall, people are more likely to litter, compared to a clean environment. However, Keizer and colleagues tested only for tag graffiti. They did consider different types of graffiti for their research design and decided on ‘simple tags as the more elaborated “pieces” might be perceived as art instead of norm violations’ (Keizer et al. 2008b ). However, while Keizer and colleagues acknowledge that different types of graffiti are valued differently, they still seem to assume that tag graffiti (as opposed to pieces) is always a norm violation, thus disregarding the variety of meanings, also to the public, of graffiti. While the broken windows thesis is popular among policy makers around the globe, the idea that there is a causal link between neighbourhood disorder and neighbourhood crime has been criticized (e.g. Sampson and Raudenbush 1999 ; Harcourt and Ludwig 2006 ). It is indeed questionable when we consider that disorder is an ambiguous phenomenon. However, even studies that do distinguish different graffiti types (e.g. Sampson and Raudenbush 1999 : tags, political and gang graffiti; Foster et al. 2010 : on public property and on private property; Perkins and Taylor 1996 : graffiti on residential and non-residential property) usually combine the different types with items such as vandalism and litter to construct a scale measuring ‘physical disorder’. Thus, all graffiti, regardless of type and location, is taken as disorder.

However, there are indications that the public perceives and judges graffiti in different ways, too, which contrast the assumption that ‘the public’ never accepts graffiti. First, studies based on small, selective groups of respondents have suggested that the type of graffiti matters for whether people find it offensive and want it removed, or whether it invokes fear (Taylor et al. 2010 ; Austin and Sanders 2007 ; Campbell 2008 ). Furthermore, types of disorder may evoke different value judgments, as Millie ( 2011 ) has suggested. On what grounds do people reject or accept graffiti? And, in what types of environments do people judge graffiti negatively or positively? We now turn to these questions.

Data and Measurements

The research for this article is based on a study commissioned and financed by the Dutch Ministry of Security and Justice and the Dutch Centre for Crime Prevention and Safety (CCV). They wanted insight into the public’s opinion on graffiti: what do people find offensive and what should authorities do about it? This study gave us the opportunity to examine the various ways in which people define graffiti and the role of context in relation to offensiveness (Vanderveen and Jelsma 2011 ). In this article we elaborate several themes that we think are relevant for further research and policy decisions.

Participants

Our study measures the evaluation of different types of graffiti in different contexts among the Dutch public. The participants in this study (N = 881) are a random sample of the TNS NIPO access panel, which is a major Dutch sample source that includes approximately 200,000 people who can be invited via the internet to participate in research studies. Participants receive a small compensation for their time. The collection of data took place in September 2010. Around 50 per cent of the panel members that were invited by TNS NIPO took part via Computer Assisted Self Interviewing. Participants could fill in the survey from their computers at home, which took on average ten minutes. Age varies from 12 to 88 years ( m = 44.6; SD = 18.3), and 428 participants (49 per cent) are male and 453 (51 per cent) are female. All participants completed the entire survey. The data are weighed in terms of gender, age, education, family size and region, and are representative of the Dutch population.

Measurements

The survey was based on several qualitative and quantitative pilot studies (conducted by the first author) which indicated that two aspects are important for whether people find graffiti offensive or not: location and graffiti type (Vanderveen and Jelsma 2011 ). For the current study we operationalized these aspects more systematically to test these first findings with a representative sample of the public.

The survey consisted of three parts which resulted in qualitative and quantitative data. The first part resulted in qualitative data. Participants were asked to describe in words the first ‘image’ of graffiti that occurred to them. They could type whatever they wanted: words, sentences and stories. The following parts resulted in quantitative data. The second part of the survey consisted of five general statements on graffiti for which participants indicated on a 7-point Likert scale to what extent they agreed (1) or disagreed (7). Statements included: ‘In general I am not disturbed by graffiti’ (recoded), ‘The presence of graffiti is a sign of crime’, ‘I feel safer in an environment where there is no graffiti’, ‘Graffiti is an art form’ (recoded) and ‘Graffiti is a common problem’. The statements together measure the general attitude regarding graffiti (α = .75); a higher score on the ‘general attitude scale’ indicates a more negative opinion about graffiti.

The third part of the survey used photos and/or short written descriptions of concrete examples of graffiti. Footnote 1 These examples were selected by the researchers based on findings from several pilot studies that included sorting tasks, interviews and a survey. Footnote 2 The 18 examples of graffiti varied for type (tags: little scribbles; throw ups: words in fat letters; pieces: colourful images; see Fig. 1 ) and location/context (a shop front; a house front; a skate park; a tunnel; a green space; an image without location). A (translated) list of the 18 examples is provided in the Appendix (photos can be viewed online in Vanderveen and Jelsma 2011 ). No information was provided about whether the graffiti examples were legal or illegal, as participants would usually not know this in reality either. Participants were asked to evaluate the 18 examples of graffiti in two ways. First, they were asked to indicate their evaluation on a 7-point scale on three items: ‘This piece of graffiti is a form of disorder’, ‘This piece of graffiti is a form of crime’ and ‘This piece of graffiti should be removed as quickly as possible’. The sum score of the three items measures the extent to which that specific example of graffiti is perceived as disorder; a higher score on the ‘perceived disorder scale’ indicates more offensiveness (reliabilities vary from α = .89 to α = .97). Second, participants were asked to indicate which graffiti should be removed first. Participants were shown three sets of six photos and/or descriptions presenting the same type of graffiti in six different locations. This procedure was repeated for each of the graffiti types (tags, throw ups and pieces).

Example of piece, tag and throw up

We conducted a content analysis of the qualitative data that resulted from the open-ended question in the first part of the survey (which asked respondent to write down their first image of graffiti). Content analysis is a method that is used to systematically interpret large numbers of words and texts and can be used to code open-ended survey questions (Weber 1990 ). The central idea is that ‘the many words of texts can be classified into much fewer content categories’ (ibid.: 12). For this study we coded all responses to the open question in order to categorize their responses. We coded the data based on two content categories: valence (neutral, negative, positive and/or mixed) and value judgment (economic, aesthetic, prudential and/or moral; based on Millie 2011 , see below). The examples of responses for each of the content categories that we offer in the results section are meant to illustrate the categories but also to give the reader insight into our interpretation of the data. The coding process makes it possible to quantify qualitative data and enabled us to analyse how valence and value judgment are related by using descriptive statistics. The quantitative data generated in parts two and three of the survey were analysed by using descriptive statistics and variance analyses.

First Images and Value Judgments

The survey started with an open question asking participants what their first image was when thinking about graffiti. A small number of participants (9 per cent) was unable or unwilling to give a description of an initial image or idea of graffiti. Those who did provide their first ideas, varied greatly in their descriptions, especially in terms of specificity and approval or rejection of graffiti. A first reading of the data shows that many descriptions (whether neutral, positive or negative) refer to places: stations, tunnels, along highways, bridges, rail roads, fences, walls, trains, subways, doors — all places that are known to be popular spots for graffiti writers (e.g. Ferrell and Weide 2010 ). A first step of the content analysis was to categorize the descriptions in terms of valence, by sorting them based on whether they made a positive or negative statement, or gave a mixed or neutral description. More than half of the initial ideas on graffiti (52 per cent, n = 459) are neutral in tone. A total of 39 per cent (n = 341) of the participants give a description that involves an evaluative component: negative (17 per cent), positive (12 per cent) or both negative and positive (10 per cent).

A second step of our content analysis was to categorize the descriptions based on value judgments. Here we draw on Millie’s ( 2011 ) distinction of four different value judgments: moral, prudential, economic and aesthetic judgments. Millie argues that whether something is perceived as disorder or crime may be related to reasons other than legal or moral reasons and that it is essential to unravel the various value judgments for understanding why something is either condemned or condoned. Moral judgments refer to the good and the bad, right and wrong, which includes reference to legal norms. Prudential judgments concern one’s personal quality of life, whether something is enjoyable or makes life good for one. Economic judgments involve decisions on economic contributions. They are judgments about whether the behaviour, person or object, ‘makes an acceptable economic contribution to society’ or, in contrast, is costly (ibid.: 7). Aesthetic judgment is related to what is considered (or accepted as) beautiful or ugly, or as artistic, in that specific context. Millie here also refers to ‘everyday aesthetics’ related to ‘everyday objects, events and encounters’ (ibid.: 8). For example, ‘a degree of drunkenness may be tolerated (…) as it fits in with an aesthetic of the night-time economy’ (ibid.). Similarly, one type of graffiti may be accepted and even welcomed (e.g. pieces or murals) while others are seen as vandalism. For example, Millie shows that authorities in Toronto rejected graffiti based on economic judgments (as ‘vandalism’ would deter tourists), while they celebrated it based on aesthetic judgments (murals can beautify certain locations).

Together, the 341 participants made 440 value judgments. In line with what Millie ( 2011 ) found, value judgments are not mutually exclusive: some of the responses included more than one value judgment. We coded all value judgments separately (five per cent (n = 21) of the judgments could not be categorized). We then examined the relationship between valence and value judgment. Table 1 shows that an overwhelming majority of the positive evaluations involve aesthetic judgments, while this holds for a much smaller majority of the negative evaluations. Negative evaluations more often involve moral judgments.

Below we demonstrate our findings in more detail by offering examples of each of the value judgments. The positive descriptions based on an aesthetical value judgment mostly connect graffiti to beauty, art, form and colour, for example:

A beautifully painted wall in Asten. Robot-like figures, letters. Pretty drawings. Complete works of art on overpasses and the tracks. Beautiful art.

Positive prudential judgments involve the idea that something contributes to the quality of life of a person, for example, ‘I enjoyed [graffiti] because it was beautifully designed’ or ‘I see few graffiti in the neighbourhood, I miss art in the neighbourhood’. A couple of responses involved a positive moral judgment, for example: ‘[…] nothing wrong with it if it happens in places where it is allowed and then I generally find it nicely done’. None of the positive responses involve an economic judgment.

In the negative judgments, graffiti is associated for example with back streets, offensiveness, deterioration, defacement, impoverishment and anti-social behaviour and called untidy, messy, awful, a load of rubbish. Negative value judgments are also mostly related to aesthetics, but a substantial share refers to moral considerations and, to a lesser extent, prudential and economic judgments (see Table 1 ). Negative aesthetic judgments point at graffiti’s ugliness, amateurish nature or untidiness:

Mess on all public walls. Often no talent. Ugly and untidy. Dirty, scribbles on walls in the centre. Visual pollution.

Negative moral judgments involve referrals to the law and norms of behaviour, such as descriptions of graffiti as vandalism, referrals to private property, anti-social behaviour, foul language and racism:

Vandalism! I see graffiti everywhere and it annoys me because it is put on everything where it doesn’t belong. Keep off of other people’s stuff. Graffiti is mess created by stupid people who destroy other people’s properties by leaving their “tags”. Painting by youngsters without having permission to do so.

Negative prudential judgments involve statements such as ‘It annoys me’ and ‘Deterioration of the city’. We counted four economic judgments, all negative, which include descriptions of graffiti as ‘destroying’ private property.

A third category of descriptions offers both positive and negative judgments about graffiti. We can divide this category into two subcategories: those who make only aesthetic judgments and those who make an aesthetic and a moral judgment. Responses in the first subcategory for example say that graffiti can be beautiful or ugly, sometimes referring to type of graffiti or its location:

Cool!! Tag (not so nice), cool drawings, many colours, sometimes makes buildings or spaces nicer. Some graffiti is really artfully made, but most is just messing with a spray can. I find it (sometimes) beautiful. […] Not when it is mess on a wall with letters. That I call pollution.

In the second subcategory aesthetic and moral judgments are combined, which demonstrates respondents’ ambiguous position towards graffiti, also sometimes referring to type of graffiti or its location:

Graffiti can be really ugly but also really beautiful. Under a bridge it can brighten things up, but on houses or buildings I think it’s a shame (vandalism). […] On wanted and unwanted places, sometimes nice, sometimes ugly. Some graffiti is just artwork except racist slogans. Vandalism, but there are also nice works of art, depends on where it is sprayed.

Here we already see that context matters: it is not just the aesthetic quality of the graffiti itself but also its location. We return to this theme below. The quantitative data supports the wide variety in evaluations. The average score on the general attitude scale was neutral ( M = 4.05, SD = 1.21). However, answers to the individual items of the scale show participants’ ambiguity on the topic (see Table 2 ). For none of the statements there is an overwhelming majority towards disagreeing or agreeing. In addition, there is no clear tendency towards agreeing with either negative statements or positive statements. For example, the proportion of participants who agrees to being disturbed by graffiti is almost as large as the proportion of participants that disagrees. The share of respondents that is not disturbed by graffiti is about equal to the share that says they feel safer in an environment without graffiti. Finally, more than half of the participants agree that graffiti is an art form, while an equal share agrees with the next statement that graffiti is a common problem. The average neutral evaluation thus masks an enormous variety and contradictions in attitudes on graffiti. Footnote 3

Evaluations of Types of Graffiti

The open question suggests that participants distinguish between types of graffiti, for example by referring to tags or letters and pieces or paintings. Several studies confirm that the graffiti type matters for whether people find it offensive and want it removed, or whether graffiti invokes fear. Taylor et al. ( 2010 ) identified eight different types of graffiti based on the (textual) content of the graffiti. They made a distinction between, for example, the ‘memorial’ (words or statements that memorialize a deceased person) and the ‘obscene’ (words or statements that have an explicit, offensive sexual connotation). Their respondents, all directly involved with the removal and/or reporting of graffiti, indicated that all obscene, hate and threatening graffiti should be removed first. Austin and Sanders ( 2007 ) conducted a pilot study among undergraduate students using photography to examine the relation between graffiti and perceived safety. They found that four graffiti types (gang, hip hop style, message and murals) correspond to different levels of perceived safety: gang related graffiti evoked the lowest level of safety and murals the highest level. Based on in-depth interviews in focus groups, Campbell ( 2008 ) reports a similar finding, with tags being judged most negatively, followed by throw-ups and most positive judgment associated with pieces.

In our study we examined whether the findings of these small studies hold up in a large-scale systematic and quantitative study among a representative sample of the Dutch public. Responses to the 18 photos, which varied for type and location, shows that evaluations of specific examples of graffiti are more negative than the general attitudes suggest. Furthermore, the score on the perceived disorder scale differs significantly for different graffiti types: tags were evaluated most negatively, followed by throw ups, while pieces were evaluated least negative (Table 3 ). The ordering of graffiti types is generally the same for all six locations: regardless of the location, tags are perceived most negatively and pieces most positively (results not shown).

To further investigate the variety in evaluations, we analysed the standard deviation (SD) and kurtosis. We can take these measures as indications of consensus, or lack thereof, as they measure the distribution of values around the mean. The measures show that tags are not only evaluated most negatively: there is also most consensus among participants about their negative character. For pieces, on the other hand, opinions are on average neutral, but there is less consensus, which means that a larger group of participants tends to the negative and another group to the positive end of the scale. These patterns support the idea (also suggested by our qualitative data) that tags are more readily associated with illegality, which is more likely to be interpreted as negative, while pieces may also be related to art, in which case its quality depends on aesthetic judgments which can be either positive or negative depending on personal taste or artistic value. In other words, types of graffiti may evoke different value judgments (Millie 2011 ): pieces may be rejected mostly when they are of low aesthetic quality, while tags will be rejected mostly based on legal or behavioural norms.

The Role of Context: Graffiti in Micro Places

Norm transgression seems to be inherent to the practice of graffiti writing. That authorities frame graffiti as ‘out of place’ (Cresswell 1996 ) has ‘ensured that successive generations of predominantly young men have taken up graffiti as a risk-laden behaviour’ through which they can accrue fame and respect among peers (McAuliffe 2012 : 189). Nonetheless, as we have demonstrated, not all graffiti is considered to be offensive or a violation of norms to the same extent. We now turn to the question how context matters in how graffiti is received. The notion of context can be conceptualized in several ways. Many criminological studies focus on the role of neighbourhood characteristics in interpreting (signals of) behaviour (e.g. Sampson and Raudenbush 1999 ; Sampson 2012 ; Franzini et al. 2008 ). Some incidents and forms of disorder may act as ‘signal disorder’ and work as a warning signal for a greater danger, while others are just ‘background “noise” to everyday life’ (Innes 2005 : 192). Innes ( 2004 ) suggests that graffiti in an otherwise nice neighbourhood is more conspicuous than graffiti in an area where there is a variety of visible problems. On the other hand, in a (gentrifying) neighbourhood that is characterized as ‘edgy’, graffiti may be valued by those who appreciate such edginess (see e.g. Ferrell and Weide 2010 ; Dovey et al. 2012 ). Thus, graffiti in one neighbourhood is not the same as the same type of graffiti in another neighbourhood.

We take a different approach. Instead of focusing on the neighbourhood, we study the smaller setting. Several criminologists have underlined the need to study smaller geographical units such as street segments, (face) blocks and (micro) places (e.g. Eck and Weisburd 1995 ; Hipp 2007 ; Smith et al. 2000 ; Weisburd et al. 2012 ). Hipp ( 2007 ) suggests that it is likely that social and physical disorder are geographically localized: disorder in one block may not affect perceptions in the next. Cultural geographers have taken this further and investigate how meanings and practices are tied up with spaces (e.g. Sibley 1995 ; Cresswell 1996 ). Particularly, meanings attributed to places involve behavioural norms, thus leading to the ‘construction of normative places where it is possible to be either “in place” or “out of place”’ (Cresswell 2009 : 5). Such insights build on the work of Mary Douglas ( 1966 ) on the interpretation of dirt as signal of danger. Millie ( 2011 ) suggests that place and time matter particularly for ‘everyday aesthetics’. For example, certain behaviours or groups that are ‘untidy’ may be removed from tourist centres, business districts, shopping malls and exclusive neighbourhoods (Millie 2008 , 2011 ). In public space, certain behaviour, such as street drinking, may be seen as ‘“out of place” and consequently as morally offensive behaviour’ (Dixon et al. 2006 : 201). What is regarded to be ‘in place’ and what is ‘out of place’ depends on the behavioural expectations which vary among different contexts; outside we expect different behaviour than inside, for example (cf. Douglas 1966 ; see also Sibley 1995 ; Cresswell 1996 ). These studies point our attention to specific norms and expectations that are tied to specific places, but also suggests that we see graffiti as an element that, in connection with other elements, constructs the meaning of places.

An example of a context in which graffiti is ‘out of place’ is graffiti on a house front. Indeed, the photo showing graffiti on a house front is judged most negatively. Also, most participants seem to agree on this (greatest consensus indicated by the SD, second most consensus indicated by Kurtosis, see Table 3 ). This corresponds with what other scholars have observed: authorities seem to condemn graffiti mostly because it would ‘destroy’ or ‘devalue’ private property (Campbell 2008 ; Millie 2011 ).