How COVID-19 pandemic changed my life

| 4 | |

| 840 | |

| , , , |

Table of Contents

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic is one of the biggest challenges that our world has ever faced. People around the globe were affected in some way by this terrible disease, whether personally or not. Amid the COVID-19 pandemic, many people felt isolated and in a state of panic. They often found themselves lacking a sense of community, confidence, and trust. The health systems in many countries were able to successfully prevent and treat people with COVID-19-related diseases while providing early intervention services to those who may not be fully aware that they are infected (Rume & Islam, 2020). Personally, this pandemic has brought numerous changes and challenges to my life. The COVID-19 pandemic affected my social, academic, and economic lifestyle positively and negatively.

Social and Academic Changes

One of the changes brought by the pandemic was economic changes that occurred very drastically (Haleem, Javaid, & Vaishya, 2020). During the pandemic, food prices started to rise, affecting the amount of money my parents could spend on goods and services. We had to reduce the food we bought as our budgets were stretched. My family also had to eliminate unhealthy food bought in bulk, such as crisps and chocolate bars. Furthermore, the pandemic made us more aware of the importance of keeping our homes clean, especially regarding cooking food. Lastly, it also made us more aware of how we talked to other people when they were ill and stayed home with them rather than being out and getting on with other things.

Furthermore, COVID-19 had a significant effect on my academic life. Immediately, measures to curb the pandemic were announced, such as closing all learning institutions in the country; my school life changed. The change began when our school implemented the online education system to ensure that we continued with our education during the lockdown period. At first, this affected me negatively because when learning was not happening in a formal environment, I struggled academically since I was not getting the face-to-face interaction with the teachers I needed. Furthermore, forcing us to attend online caused my classmates and me to feel disconnected from the knowledge being taught because we were unable to have peer participation in class. However, as the pandemic subsided, we grew accustomed to this learning mode. We realized the effects on our performance and learning satisfaction were positive, as it seemed to promote emotional and behavioral changes necessary to function in a virtual world. Students who participated in e-learning during the pandemic developed more ownership of the course requirement, increased their emotional intelligence and self-awareness, improved their communication skills, and learned to work together as a community.

If there is an area that the pandemic affected was the mental health of my family and myself. The COVID-19 pandemic caused increased anxiety, depression, and other mental health concerns that were difficult for my family and me to manage alone. Our ability to learn social resilience skills, such as self-management, was tested numerous times. One of the most visible challenges we faced was social isolation and loneliness. The multiple lockdowns made it difficult to interact with my friends and family, leading to loneliness. The changes in communication exacerbated the problem as interactions moved from face-to-face to online communication using social media and text messages. Furthermore, having family members and loved ones separated from us due to distance, unavailability of phones, and the internet created a situation of fear among us, as we did not know whether they were all right. Moreover, some people within my circle found it more challenging to communicate with friends, family, and co-workers due to poor communication skills. This was mainly attributed to anxiety or a higher risk of spreading the disease. It was also related to a poor understanding of creating and maintaining relationships during this period.

Positive Changes

In addition, this pandemic has brought some positive changes with it. First, it had been a significant catalyst for strengthening relationships and neighborhood ties. It has encouraged a sense of community because family members, neighbors, friends, and community members within my area were all working together to help each other out. Before the pandemic, everybody focused on their business, the children going to school while the older people went to work. There was not enough time to bond with each other. Well, the pandemic changed that, something that has continued until now that everything is returning to normal. In our home, it strengthened the relationship between myself and my siblings and parents. This is because we started spending more time together as a family, which enhanced our sense of understanding of ourselves.

The pandemic has been a challenging time for many people. I can confidently state that it was a significant and potentially unprecedented change in our daily life. By changing how we do things and relate with our family and friends, the pandemic has shaped our future life experiences and shown that during crises, we can come together and make a difference in each other’s lives. Therefore, I embrace wholesomely the changes brought by the COVID-19 pandemic in my life.

- Haleem, A., Javaid, M., & Vaishya, R. (2020). Effects of COVID-19 pandemic in daily life. Current medicine research and practice , 10 (2), 78.

- Rume, T., & Islam, S. D. U. (2020). Environmental effects of COVID-19 pandemic and potential strategies of sustainability. Heliyon , 6 (9), e04965.

- ☠️ Assisted Suicide

- Affordable Care Act

- Breast Cancer

- Genetic Engineering

Read these 12 moving essays about life during coronavirus

Artists, novelists, critics, and essayists are writing the first draft of history.

by Alissa Wilkinson

The world is grappling with an invisible, deadly enemy, trying to understand how to live with the threat posed by a virus . For some writers, the only way forward is to put pen to paper, trying to conceptualize and document what it feels like to continue living as countries are under lockdown and regular life seems to have ground to a halt.

So as the coronavirus pandemic has stretched around the world, it’s sparked a crop of diary entries and essays that describe how life has changed. Novelists, critics, artists, and journalists have put words to the feelings many are experiencing. The result is a first draft of how we’ll someday remember this time, filled with uncertainty and pain and fear as well as small moments of hope and humanity.

- The Vox guide to navigating the coronavirus crisis

At the New York Review of Books, Ali Bhutto writes that in Karachi, Pakistan, the government-imposed curfew due to the virus is “eerily reminiscent of past military clampdowns”:

Beneath the quiet calm lies a sense that society has been unhinged and that the usual rules no longer apply. Small groups of pedestrians look on from the shadows, like an audience watching a spectacle slowly unfolding. People pause on street corners and in the shade of trees, under the watchful gaze of the paramilitary forces and the police.

His essay concludes with the sobering note that “in the minds of many, Covid-19 is just another life-threatening hazard in a city that stumbles from one crisis to another.”

Writing from Chattanooga, novelist Jamie Quatro documents the mixed ways her neighbors have been responding to the threat, and the frustration of conflicting direction, or no direction at all, from local, state, and federal leaders:

Whiplash, trying to keep up with who’s ordering what. We’re already experiencing enough chaos without this back-and-forth. Why didn’t the federal government issue a nationwide shelter-in-place at the get-go, the way other countries did? What happens when one state’s shelter-in-place ends, while others continue? Do states still under quarantine close their borders? We are still one nation, not fifty individual countries. Right?

- A syllabus for the end of the world

Award-winning photojournalist Alessio Mamo, quarantined with his partner Marta in Sicily after she tested positive for the virus, accompanies his photographs in the Guardian of their confinement with a reflection on being confined :

The doctors asked me to take a second test, but again I tested negative. Perhaps I’m immune? The days dragged on in my apartment, in black and white, like my photos. Sometimes we tried to smile, imagining that I was asymptomatic, because I was the virus. Our smiles seemed to bring good news. My mother left hospital, but I won’t be able to see her for weeks. Marta started breathing well again, and so did I. I would have liked to photograph my country in the midst of this emergency, the battles that the doctors wage on the frontline, the hospitals pushed to their limits, Italy on its knees fighting an invisible enemy. That enemy, a day in March, knocked on my door instead.

In the New York Times Magazine, deputy editor Jessica Lustig writes with devastating clarity about her family’s life in Brooklyn while her husband battled the virus, weeks before most people began taking the threat seriously:

At the door of the clinic, we stand looking out at two older women chatting outside the doorway, oblivious. Do I wave them away? Call out that they should get far away, go home, wash their hands, stay inside? Instead we just stand there, awkwardly, until they move on. Only then do we step outside to begin the long three-block walk home. I point out the early magnolia, the forsythia. T says he is cold. The untrimmed hairs on his neck, under his beard, are white. The few people walking past us on the sidewalk don’t know that we are visitors from the future. A vision, a premonition, a walking visitation. This will be them: Either T, in the mask, or — if they’re lucky — me, tending to him.

Essayist Leslie Jamison writes in the New York Review of Books about being shut away alone in her New York City apartment with her 2-year-old daughter since she became sick:

The virus. Its sinewy, intimate name. What does it feel like in my body today? Shivering under blankets. A hot itch behind the eyes. Three sweatshirts in the middle of the day. My daughter trying to pull another blanket over my body with her tiny arms. An ache in the muscles that somehow makes it hard to lie still. This loss of taste has become a kind of sensory quarantine. It’s as if the quarantine keeps inching closer and closer to my insides. First I lost the touch of other bodies; then I lost the air; now I’ve lost the taste of bananas. Nothing about any of these losses is particularly unique. I’ve made a schedule so I won’t go insane with the toddler. Five days ago, I wrote Walk/Adventure! on it, next to a cut-out illustration of a tiger—as if we’d see tigers on our walks. It was good to keep possibility alive.

At Literary Hub, novelist Heidi Pitlor writes about the elastic nature of time during her family’s quarantine in Massachusetts:

During a shutdown, the things that mark our days—commuting to work, sending our kids to school, having a drink with friends—vanish and time takes on a flat, seamless quality. Without some self-imposed structure, it’s easy to feel a little untethered. A friend recently posted on Facebook: “For those who have lost track, today is Blursday the fortyteenth of Maprilay.” ... Giving shape to time is especially important now, when the future is so shapeless. We do not know whether the virus will continue to rage for weeks or months or, lord help us, on and off for years. We do not know when we will feel safe again. And so many of us, minus those who are gifted at compartmentalization or denial, remain largely captive to fear. We may stay this way if we do not create at least the illusion of movement in our lives, our long days spent with ourselves or partners or families.

- What day is it today?

Novelist Lauren Groff writes at the New York Review of Books about trying to escape the prison of her fears while sequestered at home in Gainesville, Florida:

Some people have imaginations sparked only by what they can see; I blame this blinkered empiricism for the parks overwhelmed with people, the bars, until a few nights ago, thickly thronged. My imagination is the opposite. I fear everything invisible to me. From the enclosure of my house, I am afraid of the suffering that isn’t present before me, the people running out of money and food or drowning in the fluid in their lungs, the deaths of health-care workers now growing ill while performing their duties. I fear the federal government, which the right wing has so—intentionally—weakened that not only is it insufficient to help its people, it is actively standing in help’s way. I fear we won’t sufficiently punish the right. I fear leaving the house and spreading the disease. I fear what this time of fear is doing to my children, their imaginations, and their souls.

At ArtForum , Berlin-based critic and writer Kristian Vistrup Madsen reflects on martinis, melancholia, and Finnish artist Jaakko Pallasvuo’s 2018 graphic novel Retreat , in which three young people exile themselves in the woods:

In melancholia, the shape of what is ending, and its temporality, is sprawling and incomprehensible. The ambivalence makes it hard to bear. The world of Retreat is rendered in lush pink and purple watercolors, which dissolve into wild and messy abstractions. In apocalypse, the divisions established in genesis bleed back out. My own Corona-retreat is similarly soft, color-field like, each day a blurred succession of quarantinis, YouTube–yoga, and televized press conferences. As restrictions mount, so does abstraction. For now, I’m still rooting for love to save the world.

At the Paris Review , Matt Levin writes about reading Virginia Woolf’s novel The Waves during quarantine:

A retreat, a quarantine, a sickness—they simultaneously distort and clarify, curtail and expand. It is an ideal state in which to read literature with a reputation for difficulty and inaccessibility, those hermetic books shorn of the handholds of conventional plot or characterization or description. A novel like Virginia Woolf’s The Waves is perfect for the state of interiority induced by quarantine—a story of three men and three women, meeting after the death of a mutual friend, told entirely in the overlapping internal monologues of the six, interspersed only with sections of pure, achingly beautiful descriptions of the natural world, a day’s procession and recession of light and waves. The novel is, in my mind’s eye, a perfectly spherical object. It is translucent and shimmering and infinitely fragile, prone to shatter at the slightest disturbance. It is not a book that can be read in snatches on the subway—it demands total absorption. Though it revels in a stark emotional nakedness, the book remains aloof, remote in its own deep self-absorption.

- Vox is starting a book club. Come read with us!

In an essay for the Financial Times, novelist Arundhati Roy writes with anger about Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s anemic response to the threat, but also offers a glimmer of hope for the future:

Historically, pandemics have forced humans to break with the past and imagine their world anew. This one is no different. It is a portal, a gateway between one world and the next. We can choose to walk through it, dragging the carcasses of our prejudice and hatred, our avarice, our data banks and dead ideas, our dead rivers and smoky skies behind us. Or we can walk through lightly, with little luggage, ready to imagine another world. And ready to fight for it.

From Boston, Nora Caplan-Bricker writes in The Point about the strange contraction of space under quarantine, in which a friend in Beirut is as close as the one around the corner in the same city:

It’s a nice illusion—nice to feel like we’re in it together, even if my real world has shrunk to one person, my husband, who sits with his laptop in the other room. It’s nice in the same way as reading those essays that reframe social distancing as solidarity. “We must begin to see the negative space as clearly as the positive, to know what we don’t do is also brilliant and full of love,” the poet Anne Boyer wrote on March 10th, the day that Massachusetts declared a state of emergency. If you squint, you could almost make sense of this quarantine as an effort to flatten, along with the curve, the distinctions we make between our bonds with others. Right now, I care for my neighbor in the same way I demonstrate love for my mother: in all instances, I stay away. And in moments this month, I have loved strangers with an intensity that is new to me. On March 14th, the Saturday night after the end of life as we knew it, I went out with my dog and found the street silent: no lines for restaurants, no children on bicycles, no couples strolling with little cups of ice cream. It had taken the combined will of thousands of people to deliver such a sudden and complete emptiness. I felt so grateful, and so bereft.

And on his own website, musician and artist David Byrne writes about rediscovering the value of working for collective good , saying that “what is happening now is an opportunity to learn how to change our behavior”:

In emergencies, citizens can suddenly cooperate and collaborate. Change can happen. We’re going to need to work together as the effects of climate change ramp up. In order for capitalism to survive in any form, we will have to be a little more socialist. Here is an opportunity for us to see things differently — to see that we really are all connected — and adjust our behavior accordingly. Are we willing to do this? Is this moment an opportunity to see how truly interdependent we all are? To live in a world that is different and better than the one we live in now? We might be too far down the road to test every asymptomatic person, but a change in our mindsets, in how we view our neighbors, could lay the groundwork for the collective action we’ll need to deal with other global crises. The time to see how connected we all are is now.

The portrait these writers paint of a world under quarantine is multifaceted. Our worlds have contracted to the confines of our homes, and yet in some ways we’re more connected than ever to one another. We feel fear and boredom, anger and gratitude, frustration and strange peace. Uncertainty drives us to find metaphors and images that will let us wrap our minds around what is happening.

Yet there’s no single “what” that is happening. Everyone is contending with the pandemic and its effects from different places and in different ways. Reading others’ experiences — even the most frightening ones — can help alleviate the loneliness and dread, a little, and remind us that what we’re going through is both unique and shared by all.

Most Popular

The damsel-ification of usha vance, traveling this summer maybe don’t let the airport scan your face., project 2025: the myths and the facts, the “largest it outage in history,” briefly explained, take a mental break with the newest vox crossword, today, explained.

Understand the world with a daily explainer plus the most compelling stories of the day.

More in Culture

The hidden cost of your Prime Day purchases

Can Glen Powell be a movie star in a post-movie-star era?

Revisiting Hillbilly Elegy, the book that made J.D. Vance

Energy drinks are everywhere. How dangerous are they?

Storm chasing has changed — a lot — since Twister

The pure media savvy of Trump’s fist pump photo, explained by an expert

For Amazon workers, the bevy of sales reinforces the human toll of “same-day delivery, lifetime of injury.”

The Twisters actor’s career explains a lot about the state of the industry.

The bestseller proves Trump’s VP pick has abiding disdain for absolutely everyone.

Originally marketed squarely at young men, they’re now coming for women’s wallets.

These days, anyone can follow a tornado, but you'll want to leave that to the professionals

“It’s his brand now.”

How Love Island USA became this summer’s most exquisite trash

The best books of the year (so far)

Your flight was canceled. Now what?

The RNC clarified Trump’s 2024 persona: Moderate authoritarian weirdo

Numbers, Facts and Trends Shaping Your World

Read our research on:

Full Topic List

Regions & Countries

- Publications

- Our Methods

- Short Reads

- Tools & Resources

Read Our Research On:

In Their Own Words, Americans Describe the Struggles and Silver Linings of the COVID-19 Pandemic

The outbreak has dramatically changed americans’ lives and relationships over the past year. we asked people to tell us about their experiences – good and bad – in living through this moment in history..

Pew Research Center has been asking survey questions over the past year about Americans’ views and reactions to the COVID-19 pandemic. In August, we gave the public a chance to tell us in their own words how the pandemic has affected them in their personal lives. We wanted to let them tell us how their lives have become more difficult or challenging, and we also asked about any unexpectedly positive events that might have happened during that time.

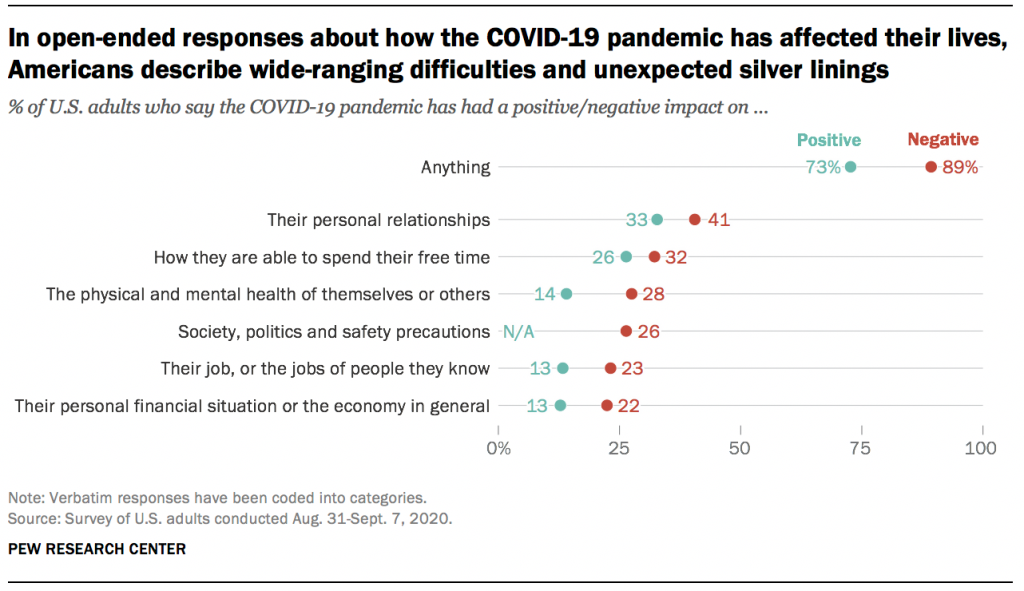

The vast majority of Americans (89%) mentioned at least one negative change in their own lives, while a smaller share (though still a 73% majority) mentioned at least one unexpected upside. Most have experienced these negative impacts and silver linings simultaneously: Two-thirds (67%) of Americans mentioned at least one negative and at least one positive change since the pandemic began.

For this analysis, we surveyed 9,220 U.S. adults between Aug. 31-Sept. 7, 2020. Everyone who completed the survey is a member of Pew Research Center’s American Trends Panel (ATP), an online survey panel that is recruited through national, random sampling of residential addresses. This way nearly all U.S. adults have a chance of selection. The survey is weighted to be representative of the U.S. adult population by gender, race, ethnicity, partisan affiliation, education and other categories. Read more about the ATP’s methodology .

Respondents to the survey were asked to describe in their own words how their lives have been difficult or challenging since the beginning of the coronavirus outbreak, and to describe any positive aspects of the situation they have personally experienced as well. Overall, 84% of respondents provided an answer to one or both of the questions. The Center then categorized a random sample of 4,071 of their answers using a combination of in-house human coders, Amazon’s Mechanical Turk service and keyword-based pattern matching. The full methodology and questions used in this analysis can be found here.

In many ways, the negatives clearly outweigh the positives – an unsurprising reaction to a pandemic that had killed more than 180,000 Americans at the time the survey was conducted. Across every major aspect of life mentioned in these responses, a larger share mentioned a negative impact than mentioned an unexpected upside. Americans also described the negative aspects of the pandemic in greater detail: On average, negative responses were longer than positive ones (27 vs. 19 words). But for all the difficulties and challenges of the pandemic, a majority of Americans were able to think of at least one silver lining.

Both the negative and positive impacts described in these responses cover many aspects of life, none of which were mentioned by a majority of Americans. Instead, the responses reveal a pandemic that has affected Americans’ lives in a variety of ways, of which there is no “typical” experience. Indeed, not all groups seem to have experienced the pandemic equally. For instance, younger and more educated Americans were more likely to mention silver linings, while women were more likely than men to mention challenges or difficulties.

Here are some direct quotes that reveal how Americans are processing the new reality that has upended life across the country.

1615 L St. NW, Suite 800 Washington, DC 20036 USA (+1) 202-419-4300 | Main (+1) 202-857-8562 | Fax (+1) 202-419-4372 | Media Inquiries

Research Topics

- Email Newsletters

ABOUT PEW RESEARCH CENTER Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping the world. It conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, media content analysis and other empirical social science research. Pew Research Center does not take policy positions. It is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts .

© 2024 Pew Research Center

Writing about COVID-19 in a college admission essay

by: Venkates Swaminathan | Updated: September 14, 2020

Print article

For students applying to college using the CommonApp, there are several different places where students and counselors can address the pandemic’s impact. The different sections have differing goals. You must understand how to use each section for its appropriate use.

The CommonApp COVID-19 question

First, the CommonApp this year has an additional question specifically about COVID-19 :

Community disruptions such as COVID-19 and natural disasters can have deep and long-lasting impacts. If you need it, this space is yours to describe those impacts. Colleges care about the effects on your health and well-being, safety, family circumstances, future plans, and education, including access to reliable technology and quiet study spaces. Please use this space to describe how these events have impacted you.

This question seeks to understand the adversity that students may have had to face due to the pandemic, the move to online education, or the shelter-in-place rules. You don’t have to answer this question if the impact on you wasn’t particularly severe. Some examples of things students should discuss include:

- The student or a family member had COVID-19 or suffered other illnesses due to confinement during the pandemic.

- The candidate had to deal with personal or family issues, such as abusive living situations or other safety concerns

- The student suffered from a lack of internet access and other online learning challenges.

- Students who dealt with problems registering for or taking standardized tests and AP exams.

Jeff Schiffman of the Tulane University admissions office has a blog about this section. He recommends students ask themselves several questions as they go about answering this section:

- Are my experiences different from others’?

- Are there noticeable changes on my transcript?

- Am I aware of my privilege?

- Am I specific? Am I explaining rather than complaining?

- Is this information being included elsewhere on my application?

If you do answer this section, be brief and to-the-point.

Counselor recommendations and school profiles

Second, counselors will, in their counselor forms and school profiles on the CommonApp, address how the school handled the pandemic and how it might have affected students, specifically as it relates to:

- Grading scales and policies

- Graduation requirements

- Instructional methods

- Schedules and course offerings

- Testing requirements

- Your academic calendar

- Other extenuating circumstances

Students don’t have to mention these matters in their application unless something unusual happened.

Writing about COVID-19 in your main essay

Write about your experiences during the pandemic in your main college essay if your experience is personal, relevant, and the most important thing to discuss in your college admission essay. That you had to stay home and study online isn’t sufficient, as millions of other students faced the same situation. But sometimes, it can be appropriate and helpful to write about something related to the pandemic in your essay. For example:

- One student developed a website for a local comic book store. The store might not have survived without the ability for people to order comic books online. The student had a long-standing relationship with the store, and it was an institution that created a community for students who otherwise felt left out.

- One student started a YouTube channel to help other students with academic subjects he was very familiar with and began tutoring others.

- Some students used their extra time that was the result of the stay-at-home orders to take online courses pursuing topics they are genuinely interested in or developing new interests, like a foreign language or music.

Experiences like this can be good topics for the CommonApp essay as long as they reflect something genuinely important about the student. For many students whose lives have been shaped by this pandemic, it can be a critical part of their college application.

Want more? Read 6 ways to improve a college essay , What the &%$! should I write about in my college essay , and Just how important is a college admissions essay? .

Homes Nearby

Homes for rent and sale near schools

How our schools are (and aren't) addressing race

The truth about homework in America

What should I write my college essay about?

What the #%@!& should I write about in my college essay?

Yes! Sign me up for updates relevant to my child's grade.

Please enter a valid email address

Thank you for signing up!

Server Issue: Please try again later. Sorry for the inconvenience

- < Previous

Home > History Community Special Collections > Remembering COVID-19 Community Archive > Community Reflections > 21

Community Reflections

My life experience during the covid-19 pandemic.

Melissa Blanco Follow

Document Type

Class Assignment

Publication Date

Affiliation with sacred heart university.

Undergraduate, Class of 2024

My content explains what my life was like during the last seven months of the Covid-19 pandemic and how it affected my life both positively and negatively. It also explains what it was like when I graduated from High School and how I want the future generations to remember the Class of 2020.

Class assignment, Western Civilization (Dr. Marino).

Recommended Citation

Blanco, Melissa, "My Life Experience During the Covid-19 Pandemic" (2020). Community Reflections . 21. https://digitalcommons.sacredheart.edu/covid19-reflections/21

Creative Commons License

Since September 23, 2020

Included in

Higher Education Commons , Virus Diseases Commons

To view the content in your browser, please download Adobe Reader or, alternately, you may Download the file to your hard drive.

NOTE: The latest versions of Adobe Reader do not support viewing PDF files within Firefox on Mac OS and if you are using a modern (Intel) Mac, there is no official plugin for viewing PDF files within the browser window.

Advanced Search

- Notify me via email or RSS

- Expert Gallery

- Collections

- Disciplines

Author Corner

- SelectedWorks Faculty Guidelines

- DigitalCommons@SHU: Nuts & Bolts, Policies & Procedures

- Sacred Heart University Library

Home | About | FAQ | My Account | Accessibility Statement

Privacy Copyright

- CBSE Class 10th

- CBSE Class 12th

- UP Board 10th

- UP Board 12th

- Bihar Board 10th

- Bihar Board 12th

Top Schools

- Top Schools in India

- Top Schools in Delhi

- Top Schools in Mumbai

- Top Schools in Chennai

- Top Schools in Hyderabad

- Top Schools in Kolkata

- Top Schools in Pune

- Top Schools in Bangalore

Products & Resources

- JEE Main Knockout April

- Free Sample Papers

- Free Ebooks

- NCERT Notes

- NCERT Syllabus

- NCERT Books

- RD Sharma Solutions

- Navodaya Vidyalaya Admission 2024-25

- NCERT Solutions

- NCERT Solutions for Class 12

- NCERT Solutions for Class 11

- NCERT solutions for Class 10

- NCERT solutions for Class 9

- NCERT solutions for Class 8

- NCERT Solutions for Class 7

- JEE Main Exam

- JEE Advanced Exam

- BITSAT Exam

- View All Engineering Exams

- Colleges Accepting B.Tech Applications

- Top Engineering Colleges in India

- Engineering Colleges in India

- Engineering Colleges in Tamil Nadu

- Engineering Colleges Accepting JEE Main

- Top IITs in India

- Top NITs in India

- Top IIITs in India

- JEE Main College Predictor

- JEE Main Rank Predictor

- MHT CET College Predictor

- AP EAMCET College Predictor

- GATE College Predictor

- KCET College Predictor

- JEE Advanced College Predictor

- View All College Predictors

- JEE Advanced Cutoff

- JEE Main Cutoff

- GATE Registration 2025

- JEE Main Syllabus 2025

- Download E-Books and Sample Papers

- Compare Colleges

- B.Tech College Applications

- JEE Main Question Papers

- MAH MBA CET Exam

- View All Management Exams

Colleges & Courses

- MBA College Admissions

- MBA Colleges in India

- Top IIMs Colleges in India

- Top Online MBA Colleges in India

- MBA Colleges Accepting XAT Score

- BBA Colleges in India

- XAT College Predictor 2025

- SNAP College Predictor

- NMAT College Predictor

- MAT College Predictor 2024

- CMAT College Predictor 2024

- CAT Percentile Predictor 2024

- CAT 2024 College Predictor

- Top MBA Entrance Exams 2024

- AP ICET Counselling 2024

- GD Topics for MBA

- CAT Exam Date 2024

- Download Helpful Ebooks

- List of Popular Branches

- QnA - Get answers to your doubts

- IIM Fees Structure

- AIIMS Nursing

- Top Medical Colleges in India

- Top Medical Colleges in India accepting NEET Score

- Medical Colleges accepting NEET

- List of Medical Colleges in India

- List of AIIMS Colleges In India

- Medical Colleges in Maharashtra

- Medical Colleges in India Accepting NEET PG

- NEET College Predictor

- NEET PG College Predictor

- NEET MDS College Predictor

- NEET Rank Predictor

- DNB PDCET College Predictor

- NEET Result 2024

- NEET Asnwer Key 2024

- NEET Cut off

- NEET Online Preparation

- Download Helpful E-books

- Colleges Accepting Admissions

- Top Law Colleges in India

- Law College Accepting CLAT Score

- List of Law Colleges in India

- Top Law Colleges in Delhi

- Top NLUs Colleges in India

- Top Law Colleges in Chandigarh

- Top Law Collages in Lucknow

Predictors & E-Books

- CLAT College Predictor

- MHCET Law ( 5 Year L.L.B) College Predictor

- AILET College Predictor

- Sample Papers

- Compare Law Collages

- Careers360 Youtube Channel

- CLAT Syllabus 2025

- CLAT Previous Year Question Paper

- NID DAT Exam

- Pearl Academy Exam

Predictors & Articles

- NIFT College Predictor

- UCEED College Predictor

- NID DAT College Predictor

- NID DAT Syllabus 2025

- NID DAT 2025

- Design Colleges in India

- Top NIFT Colleges in India

- Fashion Design Colleges in India

- Top Interior Design Colleges in India

- Top Graphic Designing Colleges in India

- Fashion Design Colleges in Delhi

- Fashion Design Colleges in Mumbai

- Top Interior Design Colleges in Bangalore

- NIFT Result 2024

- NIFT Fees Structure

- NIFT Syllabus 2025

- Free Design E-books

- List of Branches

- Careers360 Youtube channel

- IPU CET BJMC 2024

- JMI Mass Communication Entrance Exam 2024

- IIMC Entrance Exam 2024

- Media & Journalism colleges in Delhi

- Media & Journalism colleges in Bangalore

- Media & Journalism colleges in Mumbai

- List of Media & Journalism Colleges in India

- CA Intermediate

- CA Foundation

- CS Executive

- CS Professional

- Difference between CA and CS

- Difference between CA and CMA

- CA Full form

- CMA Full form

- CS Full form

- CA Salary In India

Top Courses & Careers

- Bachelor of Commerce (B.Com)

- Master of Commerce (M.Com)

- Company Secretary

- Cost Accountant

- Charted Accountant

- Credit Manager

- Financial Advisor

- Top Commerce Colleges in India

- Top Government Commerce Colleges in India

- Top Private Commerce Colleges in India

- Top M.Com Colleges in Mumbai

- Top B.Com Colleges in India

- IT Colleges in Tamil Nadu

- IT Colleges in Uttar Pradesh

- MCA Colleges in India

- BCA Colleges in India

Quick Links

- Information Technology Courses

- Programming Courses

- Web Development Courses

- Data Analytics Courses

- Big Data Analytics Courses

- RUHS Pharmacy Admission Test

- Top Pharmacy Colleges in India

- Pharmacy Colleges in Pune

- Pharmacy Colleges in Mumbai

- Colleges Accepting GPAT Score

- Pharmacy Colleges in Lucknow

- List of Pharmacy Colleges in Nagpur

- GPAT Result

- GPAT 2024 Admit Card

- GPAT Question Papers

- NCHMCT JEE 2024

- Mah BHMCT CET

- Top Hotel Management Colleges in Delhi

- Top Hotel Management Colleges in Hyderabad

- Top Hotel Management Colleges in Mumbai

- Top Hotel Management Colleges in Tamil Nadu

- Top Hotel Management Colleges in Maharashtra

- B.Sc Hotel Management

- Hotel Management

- Diploma in Hotel Management and Catering Technology

Diploma Colleges

- Top Diploma Colleges in Maharashtra

- UPSC IAS 2024

- SSC CGL 2024

- IBPS RRB 2024

- Previous Year Sample Papers

- Free Competition E-books

- Sarkari Result

- QnA- Get your doubts answered

- UPSC Previous Year Sample Papers

- CTET Previous Year Sample Papers

- SBI Clerk Previous Year Sample Papers

- NDA Previous Year Sample Papers

Upcoming Events

- NDA Application Form 2024

- UPSC IAS Application Form 2024

- CDS Application Form 2024

- CTET Admit card 2024

- HP TET Result 2023

- SSC GD Constable Admit Card 2024

- UPTET Notification 2024

- SBI Clerk Result 2024

Other Exams

- SSC CHSL 2024

- UP PCS 2024

- UGC NET 2024

- RRB NTPC 2024

- IBPS PO 2024

- IBPS Clerk 2024

- IBPS SO 2024

- Top University in USA

- Top University in Canada

- Top University in Ireland

- Top Universities in UK

- Top Universities in Australia

- Best MBA Colleges in Abroad

- Business Management Studies Colleges

Top Countries

- Study in USA

- Study in UK

- Study in Canada

- Study in Australia

- Study in Ireland

- Study in Germany

- Study in China

- Study in Europe

Student Visas

- Student Visa Canada

- Student Visa UK

- Student Visa USA

- Student Visa Australia

- Student Visa Germany

- Student Visa New Zealand

- Student Visa Ireland

- CUET PG 2024

- IGNOU B.Ed Admission 2024

- DU Admission 2024

- UP B.Ed JEE 2024

- LPU NEST 2024

- IIT JAM 2024

- IGNOU Online Admission 2024

- Universities in India

- Top Universities in India 2024

- Top Colleges in India

- Top Universities in Uttar Pradesh 2024

- Top Universities in Bihar

- Top Universities in Madhya Pradesh 2024

- Top Universities in Tamil Nadu 2024

- Central Universities in India

- CUET DU Cut off 2024

- IGNOU Date Sheet 2024

- CUET DU CSAS Portal 2024

- CUET Response Sheet 2024

- CUET Result 2024

- CUET Participating Universities 2024

- CUET Previous Year Question Paper

- CUET Syllabus 2024 for Science Students

- E-Books and Sample Papers

- CUET College Predictor 2024

- CUET Exam Date 2024

- CUET Cut Off 2024

- NIRF Ranking 2024

- IGNOU Exam Form 2024

- CUET PG Counselling 2024

- CUET Answer Key 2024

Engineering Preparation

- Knockout JEE Main 2024

- Test Series JEE Main 2024

- JEE Main 2024 Rank Booster

Medical Preparation

- Knockout NEET 2024

- Test Series NEET 2024

- Rank Booster NEET 2024

Online Courses

- JEE Main One Month Course

- NEET One Month Course

- IBSAT Free Mock Tests

- IIT JEE Foundation Course

- Knockout BITSAT 2024

- Career Guidance Tool

Top Streams

- IT & Software Certification Courses

- Engineering and Architecture Certification Courses

- Programming And Development Certification Courses

- Business and Management Certification Courses

- Marketing Certification Courses

- Health and Fitness Certification Courses

- Design Certification Courses

Specializations

- Digital Marketing Certification Courses

- Cyber Security Certification Courses

- Artificial Intelligence Certification Courses

- Business Analytics Certification Courses

- Data Science Certification Courses

- Cloud Computing Certification Courses

- Machine Learning Certification Courses

- View All Certification Courses

- UG Degree Courses

- PG Degree Courses

- Short Term Courses

- Free Courses

- Online Degrees and Diplomas

- Compare Courses

Top Providers

- Coursera Courses

- Udemy Courses

- Edx Courses

- Swayam Courses

- upGrad Courses

- Simplilearn Courses

- Great Learning Courses

Covid 19 Essay in English

Essay on Covid -19: In a very short amount of time, coronavirus has spread globally. It has had an enormous impact on people's lives, economy, and societies all around the world, affecting every country. Governments have had to take severe measures to try and contain the pandemic. The virus has altered our way of life in many ways, including its effects on our health and our economy. Here are a few sample essays on ‘CoronaVirus’.

100 Words Essay on Covid 19

200 words essay on covid 19, 500 words essay on covid 19.

COVID-19 or Corona Virus is a novel coronavirus that was first identified in 2019. It is similar to other coronaviruses, such as SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV, but it is more contagious and has caused more severe respiratory illness in people who have been infected. The novel coronavirus became a global pandemic in a very short period of time. It has affected lives, economies and societies across the world, leaving no country untouched. The virus has caused governments to take drastic measures to try and contain it. From health implications to economic and social ramifications, COVID-19 impacted every part of our lives. It has been more than 2 years since the pandemic hit and the world is still recovering from its effects.

Since the outbreak of COVID-19, the world has been impacted in a number of ways. For one, the global economy has taken a hit as businesses have been forced to close their doors. This has led to widespread job losses and an increase in poverty levels around the world. Additionally, countries have had to impose strict travel restrictions in an attempt to contain the virus, which has resulted in a decrease in tourism and international trade. Furthermore, the pandemic has put immense pressure on healthcare systems globally, as hospitals have been overwhelmed with patients suffering from the virus. Lastly, the outbreak has led to a general feeling of anxiety and uncertainty, as people are fearful of contracting the disease.

My Experience of COVID-19

I still remember how abruptly colleges and schools shut down in March 2020. I was a college student at that time and I was under the impression that everything would go back to normal in a few weeks. I could not have been more wrong. The situation only got worse every week and the government had to impose a lockdown. There were so many restrictions in place. For example, we had to wear face masks whenever we left the house, and we could only go out for essential errands. Restaurants and shops were only allowed to operate at take-out capacity, and many businesses were shut down.

In the current scenario, coronavirus is dominating all aspects of our lives. The coronavirus pandemic has wreaked havoc upon people’s lives, altering the way we live and work in a very short amount of time. It has revolutionised how we think about health care, education, and even social interaction. This virus has had long-term implications on our society, including its impact on mental health, economic stability, and global politics. But we as individuals can help to mitigate these effects by taking personal responsibility to protect themselves and those around them from infection.

Effects of CoronaVirus on Education

The outbreak of coronavirus has had a significant impact on education systems around the world. In China, where the virus originated, all schools and universities were closed for several weeks in an effort to contain the spread of the disease. Many other countries have followed suit, either closing schools altogether or suspending classes for a period of time.

This has resulted in a major disruption to the education of millions of students. Some have been able to continue their studies online, but many have not had access to the internet or have not been able to afford the costs associated with it. This has led to a widening of the digital divide between those who can afford to continue their education online and those who cannot.

The closure of schools has also had a negative impact on the mental health of many students. With no face-to-face contact with friends and teachers, some students have felt isolated and anxious. This has been compounded by the worry and uncertainty surrounding the virus itself.

The situation with coronavirus has improved and schools have been reopened but students are still catching up with the gap of 2 years that the pandemic created. In the meantime, governments and educational institutions are working together to find ways to support students and ensure that they are able to continue their education despite these difficult circumstances.

Effects of CoronaVirus on Economy

The outbreak of the coronavirus has had a significant impact on the global economy. The virus, which originated in China, has spread to over two hundred countries, resulting in widespread panic and a decrease in global trade. As a result of the outbreak, many businesses have been forced to close their doors, leading to a rise in unemployment. In addition, the stock market has taken a severe hit.

Effects of CoronaVirus on Health

The effects that coronavirus has on one's health are still being studied and researched as the virus continues to spread throughout the world. However, some of the potential effects on health that have been observed thus far include respiratory problems, fever, and coughing. In severe cases, pneumonia, kidney failure, and death can occur. It is important for people who think they may have been exposed to the virus to seek medical attention immediately so that they can be treated properly and avoid any serious complications. There is no specific cure or treatment for coronavirus at this time, but there are ways to help ease symptoms and prevent the virus from spreading.

Applications for Admissions are open.

Aakash iACST Scholarship Test 2024

Get up to 90% scholarship on NEET, JEE & Foundation courses

JEE Main Important Chemistry formulas

As per latest 2024 syllabus. Chemistry formulas, equations, & laws of class 11 & 12th chapters

JEE Main Important Physics formulas

As per latest 2024 syllabus. Physics formulas, equations, & laws of class 11 & 12th chapters

TOEFL ® Registrations 2024

Accepted by more than 11,000 universities in over 150 countries worldwide

PTE Exam 2024 Registrations

Register now for PTE & Save 5% on English Proficiency Tests with ApplyShop Gift Cards

JEE Main high scoring chapters and topics

As per latest 2024 syllabus. Study 40% syllabus and score upto 100% marks in JEE

Download Careers360 App's

Regular exam updates, QnA, Predictors, College Applications & E-books now on your Mobile

Certifications

We Appeared in

- Fact sheets

- Facts in pictures

- Publications

- Questions and answers

- Tools and toolkits

- Endometriosis

- Excessive heat

- Mental disorders

- Polycystic ovary syndrome

- All countries

- Eastern Mediterranean

- South-East Asia

- Western Pacific

- Data by country

- Country presence

- Country strengthening

- Country cooperation strategies

- News releases

- Feature stories

- Press conferences

- Commentaries

- Photo library

- Afghanistan

- Cholera

- Coronavirus disease (COVID-19)

- Greater Horn of Africa

- Israel and occupied Palestinian territory

- Disease Outbreak News

- Situation reports

- Weekly Epidemiological Record

- Surveillance

- Health emergency appeal

- International Health Regulations

- Independent Oversight and Advisory Committee

- Classifications

- Data collections

- Global Health Estimates

- Mortality Database

- Sustainable Development Goals

- Health Inequality Monitor

- Global Progress

- Data collection tools

- Global Health Observatory

- Insights and visualizations

- COVID excess deaths

- World Health Statistics

- Partnerships

- Committees and advisory groups

- Collaborating centres

- Technical teams

- Organizational structure

- Initiatives

- General Programme of Work

- WHO Academy

- Investment in WHO

- WHO Foundation

- External audit

- Financial statements

- Internal audit and investigations

- Programme Budget

- Results reports

- Governing bodies

- World Health Assembly

- Executive Board

- Member States Portal

Impact of COVID-19 on people's livelihoods, their health and our food systems

Joint statement by ilo, fao, ifad and who.

The COVID-19 pandemic has led to a dramatic loss of human life worldwide and presents an unprecedented challenge to public health, food systems and the world of work. The economic and social disruption caused by the pandemic is devastating: tens of millions of people are at risk of falling into extreme poverty, while the number of undernourished people, currently estimated at nearly 690 million, could increase by up to 132 million by the end of the year.

Millions of enterprises face an existential threat. Nearly half of the world’s 3.3 billion global workforce are at risk of losing their livelihoods. Informal economy workers are particularly vulnerable because the majority lack social protection and access to quality health care and have lost access to productive assets. Without the means to earn an income during lockdowns, many are unable to feed themselves and their families. For most, no income means no food, or, at best, less food and less nutritious food.

The pandemic has been affecting the entire food system and has laid bare its fragility. Border closures, trade restrictions and confinement measures have been preventing farmers from accessing markets, including for buying inputs and selling their produce, and agricultural workers from harvesting crops, thus disrupting domestic and international food supply chains and reducing access to healthy, safe and diverse diets. The pandemic has decimated jobs and placed millions of livelihoods at risk. As breadwinners lose jobs, fall ill and die, the food security and nutrition of millions of women and men are under threat, with those in low-income countries, particularly the most marginalized populations, which include small-scale farmers and indigenous peoples, being hardest hit.

Millions of agricultural workers – waged and self-employed – while feeding the world, regularly face high levels of working poverty, malnutrition and poor health, and suffer from a lack of safety and labour protection as well as other types of abuse. With low and irregular incomes and a lack of social support, many of them are spurred to continue working, often in unsafe conditions, thus exposing themselves and their families to additional risks. Further, when experiencing income losses, they may resort to negative coping strategies, such as distress sale of assets, predatory loans or child labour. Migrant agricultural workers are particularly vulnerable, because they face risks in their transport, working and living conditions and struggle to access support measures put in place by governments. Guaranteeing the safety and health of all agri-food workers – from primary producers to those involved in food processing, transport and retail, including street food vendors – as well as better incomes and protection, will be critical to saving lives and protecting public health, people’s livelihoods and food security.

In the COVID-19 crisis food security, public health, and employment and labour issues, in particular workers’ health and safety, converge. Adhering to workplace safety and health practices and ensuring access to decent work and the protection of labour rights in all industries will be crucial in addressing the human dimension of the crisis. Immediate and purposeful action to save lives and livelihoods should include extending social protection towards universal health coverage and income support for those most affected. These include workers in the informal economy and in poorly protected and low-paid jobs, including youth, older workers, and migrants. Particular attention must be paid to the situation of women, who are over-represented in low-paid jobs and care roles. Different forms of support are key, including cash transfers, child allowances and healthy school meals, shelter and food relief initiatives, support for employment retention and recovery, and financial relief for businesses, including micro, small and medium-sized enterprises. In designing and implementing such measures it is essential that governments work closely with employers and workers.

Countries dealing with existing humanitarian crises or emergencies are particularly exposed to the effects of COVID-19. Responding swiftly to the pandemic, while ensuring that humanitarian and recovery assistance reaches those most in need, is critical.

Now is the time for global solidarity and support, especially with the most vulnerable in our societies, particularly in the emerging and developing world. Only together can we overcome the intertwined health and social and economic impacts of the pandemic and prevent its escalation into a protracted humanitarian and food security catastrophe, with the potential loss of already achieved development gains.

We must recognize this opportunity to build back better, as noted in the Policy Brief issued by the United Nations Secretary-General. We are committed to pooling our expertise and experience to support countries in their crisis response measures and efforts to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals. We need to develop long-term sustainable strategies to address the challenges facing the health and agri-food sectors. Priority should be given to addressing underlying food security and malnutrition challenges, tackling rural poverty, in particular through more and better jobs in the rural economy, extending social protection to all, facilitating safe migration pathways and promoting the formalization of the informal economy.

We must rethink the future of our environment and tackle climate change and environmental degradation with ambition and urgency. Only then can we protect the health, livelihoods, food security and nutrition of all people, and ensure that our ‘new normal’ is a better one.

Media Contacts

Kimberly Chriscaden

Communications Officer World Health Organization

Nutrition and Food Safety (NFS) and COVID-19

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- SAGE - PMC COVID-19 Collection

The Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Family Well-Being: A Literature Review

Maria gayatri.

1 Directorate for Development of Service Quality of Family Planning, National Population and Family Planning Board (BKKBN), Jakarta, Indonesia

Mardiana Dwi Puspitasari

2 Research Center for Population, National Research and Innovation Agency (BRIN), Jakarta, Indonesia

Background: COVID-19 has changed family life, including employment status, financial security, the mental health of individual family members, children's education, family well-being, and family resilience. The aim of this study is to analyze the previous studies in relation to family well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic. Methods: A literature review was conducted on PubMed, Medline, Web of Science, and Scopus for studies using a cross-sectional or quasi-experimental design published from their inception to October 15, 2020, using the keywords “COVID-19,” “pandemic,” “coronavirus,” “family,” “welfare,” “well-being,” and “resilience.” A manual search on Google Scholar was used to find relevant articles based on the eligibility criteria in this study. The presented conceptual framework is based on the family stress model to link the inherent pandemic hardships and the family well-being. Results: The results show that family income loss/economic difficulties, job loss, worsening mental health, and illness were reported in some families during the COVID-19 pandemic. Family life has been influenced since the early stage of the pandemic by the implementation of physical distancing, quarantine, and staying at home to curb the spread of coronavirus. During the pandemic, it is important to maintain family well-being by staying connected with communication, managing conflict, and making quality time within family. Conclusion: The government should take action to mitigate the social, economic, and health impacts of the pandemic on families, especially those who are vulnerable to losing household income. Promoting family resilience through shared beliefs and close relationships within families is needed during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Introduction

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is a form of pneumonia caused by the severe acute respiratory coronavirus syndrome 2 (SARS-CoV-2) ( Lai et al., 2020 ). The appearance of COVID-19 becomes an outbreak in December 2019 in China. The coronavirus disease can be transmitted through the respiratory tract, digestive system, and also mucosal surface ( Ye et al., 2020 ). Fever, cough, shortness of breath, and diarrhea are the symptoms of COVID-19 infection at the onset. The pandemic of COVID-19 has brought many changes to all the communities, workers, and families to reduce the spread of the coronavirus and limit its impact on health, societal, and economic consequences. This pandemic had a powerful impact on family life. Mental resilience is required for coping strategies during the pandemic ( Barzilay et al., 2020 ).

COVID-19 has changed family life, including employment, financial instability, the mental health of family members, children's education, family well-being, and family resilience. People start to protect themselves from the spread of the coronavirus by physical and social distancing, sheltering-in-place, restricting travel, and implementing health protocols. Some public places are abrupt closures, such as schools, childcare centers, community programs, religious places, and workplaces. This change impacts social life, such as isolation, psychological distress, substantial economic distress, depression, and also domestic violence, including child abuse ( Campbell, 2020 ; Patrick et al., 2020 ). The Internet has become the most important thing to support all activities while staying at home and staying connected with others.

Families are forced to maintain a work–life balance in the same place with all family members during the pandemic ( Fisher et al., 2020 ). Parents are working from home while children are in school. Therefore, parents and children should share the space for their activities at home. On the one hand, parents should focus on their job to maintain their working target in order to avoid losing their job, heighten their financial concerns, sustain their food security, maintain healthy habits, and keep their family members safe from COVID-19. Balancing life during the pandemic is challenging ( Fisher et al., 2020 ). Fathers and mothers should work together not only on the paid job but also on domestic chores, childcare, and teaching their children.

The aim of this literature review is to identify the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on family well-being based on the previously published articles.

Literature Review

The coronavirus pandemic has become a public health crisis or disaster that has had an impact on family well-being both directly and indirectly. An infectious disease outbreak has spread rapidly, severely disrupted the world, and resulted in morbidity and mortality. This pandemic produced not only a health crisis, but also a social crisis among the population ( Murthy, 2020 ).

The conceptual framework was adapted from McCubbin and Patterson's family stress model. Using McCubbin and Patterson's family stress model, stressful life events (external stressors) had an impact on family life. During the COVID-19 pandemic, there was a profound impact on Indonesian economic growth and labor market, indicating that more people were living in poverty ( Gandasari & Dwidienawati, 2020 ; Olivia et al., 2020 ; Suryahadi et al., 2020 ). Stress-frustration theory indicates that diminished economic resources in the family could add to stress, frustration, and conflict in interpersonal interactions, which might increase the risk of men committing violence against women ( Kaukinen, 2020 ). It means that unemployment and economic instability contributed to the family stress. Furthermore, the underlying pandemic difficulties posed a threat to Indonesian people's mental health ( Abdullah, 2020 ; Megatsari et al., 2020 ). A higher risk of stress could lead to domestic violence. Domestic violence was defined as a coping mechanism for stress induced by social-systemic variables, such as poverty, unemployment, homelessness, loneliness, and ecological characteristics ( Zhang, 2020 ). Individual stress and other factors (such as job loss, lower income, limited resources and support, and hazardous and harmful alcohol use) were associated with domestic violence during the COVID-19 pandemic ( Campbell, 2020 ). Indonesian children were also affected. A recent study found that the financial burden within the family constituted a risk to Indonesian child competency and adjustment ( Riany & Morawska, 2021 ). The well-being of children might be dependent on the well-being of their parents ( Dahl et al., 2014 ). As a result, the inherent pandemic hardships posed a risk to family well-being.

According to the family stress model, the family must engage in an active process to balance external stressors with personal and family resources and a positive outlook on COVID-19 in order to develop and sustain an adaptive coping strategy to face the inherent pandemic hardships and eventually reach a level of family well-being. Mental health and prevention from the risk of mental disorders were required by incorporating individuals, families, communities, and government during and after pandemic events, so that family well-being and resilience could be achieved and improved ( Murthy, 2020 ). Resilience was characterized as a process that encompassed not just successfully adapting and functioning after experiencing adversity or crisis, but also the possibility of personal and relationship transformation and positive growth as a result of adversity ( Walsh, 1996 ). There were three fundamental processes to becoming resilient: shared belief systems, organizational patterns, and communication processes within the family ( Walsh, 1996 ).

A literature review was conducted based on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines ( Moher et al., 2009 ). This study was conducted from the beginning of March 2020, when the first positive case occurred in Indonesia, to October 1, 2020.

In order to meet the research objective, the authors carried out the literature review by searching various databases. The present study uses an integrative review to summarize the existing evidence to obtain a comprehensive understanding of the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on family welfare. PubMed, Medline, Web of Science, and Scopus are selected as the main sources of the article's database. A manual search on Google Scholar is also conducted to find relevant articles based on the study’s eligibility criteria. The following keywords are used to perform the search, such as “COVID-19,” “pandemic,” “coronavirus,” “family,” “welfare,” “resilience,” and “mental health.” A total of 67 articles with the matching keywords were primarily retrieved.

Studies were eligible for inclusion if the studies are cross-sectional, experimental designs, or cohort studies describing the impact of the pandemics on family well-being both physical and mental well-being. Studies had to be published from the inception of the pandemic to October 15, 2020, in a journal with impact factors, English-language studies, and related to the COVID-19 pandemic. However, some articles are excluded because they are duplicate articles or studies in non-English language. We also excluded opinions, letters to the editor, and systematic reviews or meta-analyses. Moreover, unpublished articles and reports are also excluded from this study. Finally, based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria, eight articles met the inclusion criteria, and the data were extracted for the next analysis.

Based on eight articles, the data were extracted to include some important information, such as (1) Country/Region, (2) The purpose of the study, (3) Methods of the study, (4) The respondents (sample size and sample characteristics), (5) the main result of the study. The data extraction is done using a form on Microsoft Excel. All articles in this study were evaluated using narrative synthesis and presented data in the table forms.

A total of eight articles were selected for this study, with various subjects consisting of children, adolescents, adults, and parents. The literature review in this study is based on previous studies in the United States, Canada, Brazil, the United Kingdom, Germany, Ireland, Israel, China, Taiwan, Japan, and Bangladesh. Common impacts are physiological stress, anxiety, depression, income loss, fear, economic hardship, food insecurity, and family violence. Higher resilience is associated with fewer COVID-19-related worries, lower anxiety, and lower depression. Greater parental control is associated with lower stress and a lower risk of child abuse. Positive children were infected by the household contact. The results of the review are shown in Table 1 .

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Studies.

| Reference | Country | Purpose | Method | Respondents | Main result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ) | The United States | To determine how the pandemic and mitigation efforts affected the physical and emotional well-being of parents and children in the United States through early June 2020 | Online research panel created by using probability-based address sampling of U.S. households. National survey of parents using the Ipsos Knowledge Panel. Households without Internet at the time of recruitment are provided with an Internet-enabled tablet | 1,011 parents with at least one child under the age of 18 years old in the household | 27% of parents reported worsening mental health themselves, and 14% reported worsening behavioral health of their children. The proportion of families with moderate or severe food insecurity increased. Employer-sponsored insurance coverage for children decreased, and parents reported a loss of regular childcare |

| ) | Bangladesh | To investigate the relationships between human COVID-19 stress with basic demographic, fear of infection, and insecurity-related variables, which can be helpful in facilitating mental health policies and strategies during the COVID-19 crisis period | Online-based survey | 340 Bangladeshi adult populations (65.9% male) | About 85.60% of the participants are in COVID-19-related stress, which results in sleep shortness, short temper, and chaos in family. Fear of COVID-19 infection (i.e., self and/or family member(s), and/or relatives), hampering scheduled study plans and future career, and financial difficulties are identified as the main causes of human stress Economic hardship and food shortages are linked together and cause stress for millions of people, while hamper of formal education and future plan create stress for job seekers |

| ) | Israel | To investigate the extent to which individual resilience, well-being, and demographic characteristics may predict two indicators of the coronavirus pandemic: distress symptoms and perceived danger | Online survey: an Internet panel company and an Internet survey through social media by using snowball sampling | 605 Jewish Israelis from the Internet survey company and 741 respondents from the Internet sample | Individual resilience and well-being were the strongest predictors of distress symptoms and a sense of danger |

| ) | The United States, Israel, and other countries (the United Kingdom, Canada, Brazil, Germany, Ireland, etc.) | To measure resilience using self-reported surveys and explore differences in COVID-19-related stress and resilience | Online survey on a crowdsourcing research website | 3,042 participants of healthcare providers and non-healthcare providers (engineering, computers, finance, research, legal, government, administration, student, teaching). | Respondents were more distressed about family members contracting COVID-19 and unknowingly infecting others than they were about contracting COVID-19 themselves Higher resilience scores were associated with fewer COVID-19-related worries. Increasing resilience score was associated with a reduced rate of anxiety and depression |

| ) | United States | To examine the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic in relation to parental perceived stress and child abuse potential | Online survey via Qualtrics | 183 parents with a child under the age of 18 years old in the western United States | Greater COVID-19-related stressors and high anxiety and depressive symptoms are associated with higher parental perceived stress. Receipt of financial assistance and high anxiety and depressive symptoms are associated with higher child abuse potential. Conversely, greater parental support and perceived control during the pandemic are associated with lower perceived stress and child abuse potential. The results also indicate racial and ethnic differences in COVID-19-related stressors |

| ) | China | To analyze the different clinical characteristics between children and their families infected with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 | Retrospective review of the clinical, laboratory, and radiologic tests | 9 children and their 14 families | All the children were diagnosed with positive results after their family's onset, which indicated that they were infected by the household contact. A positive PCR among children may relate to mental health after discharge. The duration of positive PCR among children is longer compared with their adult families |

| ) | Taiwan | To explore family members’ concerns for their relatives during the lockdown period, assess their level of acceptance of the visiting restriction policy, and determine the associated factors | Telephone interviews of family members of residents in long-term care facilities comprising 186 beds | 156 family members | The most common concerns of the family members for their relatives were psychological stress (such as feelings of loneliness among residents), followed by nursing care, and daily activity. More than 80% of respondents accepted the visiting restriction policy, and a higher satisfaction rating was independently associated with acceptance of the visiting restriction policy |

| ) | Japan | To examine the relationship between the presence or absence of a COVID-19 patient in a close setting and psychological distress levels | Administrative survey using social networking service (SNS): chatbot on LINE | 16,402 people aged 15 years and older | In the groups under the age of 60 years old, respondents with COVID-19 patients in a close setting had higher psychological stress |

Coronavirus diseases put families in uncertain conditions without clarity on how long the pandemic situation will last. The pandemic has caused many challenges that impact on family unit and the functions of the family unit, including distraction in family relationships ( Luttik et al., 2020 ). These challenges will have an influence on family well-being in many aspects, such as loss of community, loss of income, resources, planned activities, and travel due to quarantine. The concern about nuclear family members increased because they did not want their family to become ill from the coronavirus. It is suggested to not visit the older members or those with serious illnesses who are more vulnerable to the virus.

Family life has been influenced since the early stage of the pandemic by the implementation of physical distancing, quarantine, and staying at home to curb the spread of coronavirus. Physical and social distancing are effective mitigations to reduce the spread of the coronavirus during the outbreak. However, distancing requires adaptation among family members to improve family well-being. Sheltering-in-place makes more frequent interactions among family members because they have limited opportunities to have a leisure time into the outside world. This condition, on the one hand, can create a quality time and intimate interactions among family members, but on the other hand, it may lead to long-standing high conflicts, occasionally domestic violence, and divorce ( Lebow, 2020b ). In this condition, a home can be described as a place of warmth, love, and safety or as a place of intimidation, abuse, and fear ( Hitchings & Maclean, 2020 ). Other studies found a positive outlook on the COVID-19 pandemic regarding the necessity of focusing on and enjoying family relationships, especially taking advantage of the pandemic's gift of extended time together ( Evans et al., 2020 ; Holmberg et al., 2021 ). This optimistic attitude could function as a shared belief system within the family, resulting in family resilience. Working life balance at home during the time of COVID-19 provides a new chance for internal conflicts, disagreements, and arguments in which parents try to play their multi-roles with all family members to mitigate some problems such as unemployment and financial instability ( Lebow, 2020b ). Family income loss/economic difficulties, job loss, experienced hardships during the pandemic, worsening mental and behavioral health, stress, high anxiety, distress about family contracting COVID-19, and illness are reported in some families during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Domestic violence related to mental and physical health may happen during the COVID-19 quarantine. Family members lived in complex situations during the pandemic, which increased the risk of overexposure by increasing the levels of stress, anxiety, and instability. The increase in domestic violence during the pandemic is reported in many countries, such as China, Brazil, the United States, and Italy, which may represent as “tip of the iceberg” since many victims do not have the freedom to report the abuse ( Campbell, 2020 ). Domestic violence is reported as physical harm, emotional harm, and abuse. Intimate partner violence is a common form of family violence during the COVID-19 pandemic ( Kaukinen, 2020 ; Zhang, 2020 ). There are three factors of family violence, such as the opportunities of family violence during lockdown and isolation at home, the economic crisis in the households, and insufficient social support for the victims of domestic violence ( Zhang, 2020 ). Individual resilience is a strong predictor of the willingness of people to cope with emergencies and challenges of different kinds, including the COVID-19 pandemic ( Kimhi et al., 2020 ). Individual resilience and well-being are significant factors influencing distress symptoms and a sense of danger ( Kimhi et al., 2020 ). Physical abuse, emotional abuse, and stalking are kinds of intimate partner violence that are experienced by some women during the COVID-19 quarantine ( Mazza et al., 2020 ).