An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Front Sports Act Living

Building bridges: Connecting sport marketing and critical social science research

Associated data.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Recently, sport management scholars have called for researchers to critically evaluate the ways in which research questions and resulting contributions truly disrupt what is known, how it is known, why it is important to know, and for whom. Historically, sport marketing research has adapted traditional research approaches from the parent marketing discipline to sport. Yet, sport is a constantly evolving social and cultural phenomenon and a reliance on conventional theories, concepts, and methods can serve to crystalize the discourse in sport marketing in ways that may limit knowledge production. Responding to this call, we believe that sport marketing research has much to gain from engaging with critical social science assumptions, worldviews, and perspectives to examine complex issues in sport. We position this paper as a starting point for advancing the field of sport marketing in meaningful and impactful ways by offering two research propositions, each accompanied by four actional recommendations. We employ a particular focus on the marketing campaigns that activate and promote corporate partnerships in sport to frame our two propositions, which discuss (1) consumer culture theory and (2) the circuit of culture as two important frameworks that begin to build bridges between sport marketing and critical social science.

Introduction

Researchers of sport and sport-related groups are being nudged by institutions, funding bodies, and publication “gatekeepers” (e.g., editors and reviewers) to justify the value of their work in ways that move beyond addressing a gap in the literature. While “gap-spotting” is a common way to formulate research questions from existing literature, Sandberg and Alvesson ( 1 ) claim that “it does not actively challenge the assumptions underlying existing theory” (p. 33). Alternatively, they suggest that problematization leads to more innovative and novel research questions that “disrupt the reproduction and continuation of an institutionalized line of reasoning” [( 1 ), p. 32]. Recently, Stenling and Fahlén ( 2 ) call for sport management researchers (broadly interpreted) to consider what is “worthwhile knowledge” and to “clarify on whose behalf a study is conducted and, thus, for whom, in what ways, and why its contribution is important” (p. 16). Further, their recommendations for sport management researchers align with Sandberg and Alvesson ( 1 ) in that research should disrupt prevailing assumptions to build “new, significant, and meaningful knowledge that alters the way we understand and explain sport management practice” [( 2 ), p. 16]. In the field of sport marketing specifically, Kim et al. [( 3 ), p. 59] argue that sport marketing research has historically “been more normal research practice focusing on post-positivistic [consumer] behavior-based studies,” with the notion of “normal research” stemming from Kuhn's [( 4 ), p. 163] reference to a “highly convergent activity based firmly upon a settled consensus acquired from scientific education and reinforced by subsequent life in the profession.” Kim et al. [( 3 ), p. 59] highlight the need for “optimal balance between normal research with convergent thinking and innovative practices with divergent ideas” for scientific progress.

The purpose of this commentary is to serve as a point of departure for discussions on progressing the field of sport marketing in meaningful and impactful ways. We echo Stenling and Fahlén's ( 2 ) “call to arms” with an explicit focus on bridging sport marketing and critical social science. We agree with others who advocate for collapsing disciplinary silos [e.g., ( 5 , 6 )], and assert that sport marketing research has much to gain from engaging with critical social science assumptions, worldviews, and perspectives to examine complex issues in sport. We outline how sport marketing researchers may challenge the pre-existing assumptions in the field by encouraging others to “read ‘horizontally' to gain a ‘multi-silo' perspective of the phenomenon of interest, thereby facilitating the creation of knowledge that makes us think of phenomena in new ways” [( 2 ), pp. 16–17]. In what follows, we discuss two research propositions, (1) consumer culture theory and (2) the circuit of culture, as two important frameworks that integrate sport marketing and critical social science. From the outset, we acknowledge that these are only two of many potential areas for synthesis, and even within these frameworks, there are numerous possibilities to explore. However, to help others envision our proposals, for each proposition we offer actionable recommendations as innovative research directions that promise new knowledge discovery.

Frisby [( 7 ), p. 2] describes critical social science as “a way of empowering individuals by confronting injustices in order to promote social change.” Research that adopts critical approaches features prominently in sport sociology, with scholars suggesting that incorporating these perspectives into sport management research can advance the field ( 8 ). Researchers that utilize a critical view “are concerned about goals other than profit and with representing the interests of those affected by managerial actions, such as workers, athletes, volunteers, customers, marginalized populations, and the public at large” [( 7 ), p. 6]. These approaches appear infrequently in journals within the domain of sport marketing, despite their importance in sport management research for “unpacking the less-desirable aspects of sport as a social system,” resulting in a stable foundation “upon which positive change in sport can be made” [( 9 ), p. 9]. According to Sayer [( 10 ), p. 768], the job of critical social science is “to ‘unsettle' existing academic ideas.” Therefore, incorporating critical social science approaches into sport marketing research may help to “expand our understanding of sport's role in society, how it may be an exclusionary space and to provide a strong theoretical basis for practical improvements by challenging power relations” [( 9 ), p. 2].

Sport is a commodity and practice, and is a globally popular, highly visible, and influential part of society. Corporate brands use the appeal and excitement of sport to communicate their messages to consumers ( 11 ) and accomplish their business objectives ( 12 ). Currently there is momentum—and arguably a strong need—for professional sport (and related corporate partnerships) to have positive social impact, to help achieve social justice, and to minimize (the effects of) inequality. Arguably, sport marketing plays an equally important role in attracting large audiences to sport and associating corporate brands with the social and cultural values of sport. In this sense, marketing campaigns that activate and promote corporate partnerships with sport are “privileged form[s] of social communication” that can be utilized by marketers to influence culture, social interactions, and identities [( 13 ), pp. 103–104]. Through marketing, brands create powerful stories and compelling narratives that consumers use to process their own tensions, desires, and anxieties that originate from broader societal problems ( 14 ). For example, Nike's “For Once Don't Do It” advertisement following the Black Lives Matter Movement, Amazon's Climate Pledge Arena in Seattle, and Scotiabank's “Hockey for All” campaign, to name a few. Yet, the “corporatization, privatization, and branding” of social justice issues by commercial organizations has become “increasingly complex, messy, and blurred” [( 15 ), p. 523], with regards to corporate intentions and “rising consumer expectations of corporate social responsibility” [( 16 ), p. 132]. As consumers become more discerning of corporate partnerships with sport, brands may be perceived as exploitative, disingenuous, and superfluous ( 17 – 20 ). Additionally, athletes and coaches, given their celebrity status and large followings, can “shape fans' attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors” [( 21 ), p. 36], which can influence how sport marketers communicate with consumers. Crucially, framing sport marketing and consumer research from a position that upholds sport as a distinct social and cultural practice and queries why and how definitions and meanings of sport serve some interests over others [e.g., professional athlete, sport organization, corporate entity, fan/consumer; ( 22 )], begins a long, convoluted journey to problematize and disrupt our assumptions about the association of corporate brands with sport.

Consumer culture theory

Consumer Culture Theory (CCT) “refers to a family of theoretical perspectives that address the dynamic relationship between consumer actions, the culture marketplace, and cultural meanings” [( 23 ), p. 868]. It consists of four salient, interconnected theoretical dimensions consisting of: “(1) consumer identity projects, (2) marketplace cultures, (3) the sociohistoric patterning of consumption, and (4) mass-mediated marketplace ideologies and consumers' interpretive strategies” [( 23 ), p. 871]. According to CCT, supporters can create and attribute meaning to the images, texts, and objectives that are commercially produced and through which consumers make sense of their environment, which can lead to consumers redefining the meaning of a brand based on their collective interpretation thereof ( 14 , 24 ). Thus, supporter groups may dictate the symbolism of brands associated with sport, with positive values (e.g., distinctiveness) benefitting the brand ( 25 ), and resistance occurring if they do not perceive that the team derives value from the connection ( 18 ). Rokka [( 14 ), p. 114] recently commented that “CCT's future looks promising in its commitment and ability to foster critical, contextually sensitive, and reflexive cultural insights into marketing—an important foundation for marketing strategy and practices.” As such, CCT can play a role in exploring the contextual factors that influence how supporters and supporter groups interpret and attribute meaning to a brand.

At present, much sport marketing consumer research is largely informed by cognitive psychological (behavioral) or economic theories. While these studies are important for continued understanding of consumer attitudes toward products/services and purchasing behaviors, there is an opportunity to engage with CCT and social theories (e.g., social constructivism, feminism, critical race theory) to critique “the structural foundations and limitations of the consumers' experiential universe” [( 26 ), p. 386]. CCT is often set within the context of social historical production as well as the prevailing socio-economic conditions, which contextualizes consumer-based practices and perspectives within the structures and systems that transcend lived experience. This allows “CCT researchers [to look] toward understanding market systems and dynamics and [approach] consumer culture not just as a matter of what consumers do but also how the world in which they do it is constituted” [( 27 ), p. 135]. Ultimately, the goal is to give greater consideration to “the context of contexts” [( 26 ), p. 396]. That is, to “pay increased attention to the contexts that condition consumption” [( 26 ), p. 389]. Sport marketing research needs to, in the very least, consider how consumption experiences are embedded within broader social structures, cultural norms, and ideological injustices, including (among others): racism, gender relations, homophobia, and classism. These contexts cannot be ignored as consumers navigate, engage in, and challenge everyday consumer culture. “Looking at the ways that everyday consumption practices reproduce larger cultural and social frameworks is also a matter of asking not only how consumption is influenced by social forms and processes, but how it participates in the constitution of society” [( 26 ), p. 396]. Given this discussion, we offer our first research proposition and four corresponding actionable recommendations.

Proposition 1: Critical engagement with CCT can provide a lens to examine realities beyond the individual sport consumer/fan.

Actionable Recommendations:

- Develop a better understanding of the meanings and values linked with signs, symbols, rituals, and traditions that shape brand community identity creation and development in sport.

- Generate a better understanding of the micro- and macro-level contextual influences (systemic and structural) of market and social systems that guide sport consumption experiences, identities, and communities.

- Seek a better understanding of the important actors (e.g., marketers, sport organization executives, brand executives) that participate in the contexts of sport consumption—actors that have their own social and cultural values.

- Establish a better understanding of ‘sport consumer-brand consumption' relationships as functions of sport, wherein both sport and consumption are recognized as social and cultural practices that can confer identity, values, and beliefs.

The circuit of culture

Previous research on sport-related advertising and the communication of corporate brand partnerships in sport have adopted the circuit of culture as a framework to critically analyze sport-related promotion and advertising ( 28 , 29 ). Accordingly, the circuit of culture, which traces the “lifecycle” of a commodity in contemporary society ( 30 ), has become an important component of research related to the growth of advertising, consumption, and commercialization within society ( 31 ). It consists of five interrelated cultural processes: production, representation, consumption, and identity, the components necessary to adequately examine commodities ( 30 ). As a circuit, the starting point is irrelevant, since the journey of explaining the meaning of an artifact involves analysis at each moment; cognizant that the processes are not distinct, rather each element converses with and blends into the next ( 30 ), overlapping one another and, hence, mutually defining and jointly dependent ( 32 ). It is the combined articulation or linkages of these processes that begin to explain the meaning cultural artifacts possess and the identities that they construct and/or embody ( 30 ). According to du Gay et al. [( 30 ), p. 3], the five interlinked spheres facilitate the exploration of cultural artifacts in terms of “how it is represented, what social identities are associated with it, how it is produced and consumed, and what mechanisms regulate its distribution.”

In sport contexts, research often focuses more on the representation and identity components, and fails to examine consumption and regulation ( 31 ). Thus, this research captures more of the critical perspective that misappropriation and inaccurate representation can have on groups of people ( 28 ), while analyzing the individuals that are responsible for generating the advertisements ( 33 ). Conversely, sport marketing research often does not consider the content or sociocultural implications of advertisements (particularly on marginalized groups), nor that of the activations undertaken by brands involved with sport, instead focusing on the consumption of products (e.g., purchase intention), attitudinal outcomes (e.g., sponsor image), and other sponsorship constructs, including supporter identification, fit, and awareness ( 34 , 35 ).

In critical social science research, sport-related advertisements are critically analyzed using the circuit of culture framework to examine the content, how the advertisement was produced, how the cultural intermediaries responsible for creating the advertisement chose to represent the sexuality, gender, and race of the people that appeared in the advertisement, and how the advertisement was consumed and interpreted by viewers ( 28 ). However, the focus of this research adopts the critical perspective without considering the marketing-related outcomes for the advertised brand (e.g., awareness, attitudes) after the advertisement has been processed and interpreted. Therefore, marketing research evaluating corporate brand partnerships in sport should incorporate critical analysis of the production, identity, and consumption contained within the circuit of culture to move beyond the individual consumer into the broader societal and cultural context surrounding the positioning of the advertised brand. Given this discussion, we offer our second research proposition and four corresponding actionable recommendations.

Proposition 2: The circuit of culture offers a framework to explore how consumers react to and interpret the content of marketing campaigns that activate and promote corporate partnerships in sport.

- Examine how advertising content and messaging influences consumers' subsequent attitudinal and behavioral responses to the advertisements.

- Explore the power relations between cultural intermediaries and marginalized populations and any resulting social injustices.

- Investigate how marketers' idealized and/or stereotypical representations of particular groups (e.g., men/women, racial, Indigenous, LGBTIQ2S+, etc.) can impact a group's identity and consumption behaviors.

- Analyze the manner in which a product's intended meaning is altered through consumption experiences and identity regulation.

In this commentary, we propose two research propositions that connect sport marketing and critical social science research. These are unorthodox but imperative proposals that require radical reconsideration of two research fundamentals. First, these propositions challenge traditional ontological marketing worldviews that embrace a (post)positivist paradigm ( 3 ), and instead advocate for ontological claims that “reality is created through [macro and] microsocial interactions” (interpretivist paradigm) and/or “reality is rooted in the tensions surrounding historically entrenched power relations” (critical realist paradigm; [( 7 ), pp. 2–3]. Second, these propositions prompt the need for new research designs (e.g., ethnography) that necessitate the integration of qualitative or multi/mixed methods, which diverts from the “normal research” [( 4 ), p. 163] that is generally conducted in sport marketing. Taken together, we uphold that these propositions open up possibilities for sport marketing research to be innovative and impactful, to disrupt repeated and institutionalized lines of reasoning/inquiry, and to create new expectations for what is worthwhile knowledge in the field.

Data availability statement

Author contributions.

ZE was responsible for conceptualizing and writing the manuscript. SG and TE offered guidance on the conceptualization and writing of the manuscript, in addition to edits, revisions, and helping to re-write some parts of the final manuscript. All authors have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to this manuscript and approved the manuscript in the form in which it was submitted.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Tracing the state of sport management research: a bibliometric analysis

- Open access

- Published: 24 February 2023

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Jonas Hammerschmidt 1 ,

- Ferran Calabuig 2 ,

- Sascha Kraus ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-4886-7482 3 , 4 &

- Sebastian Uhrich 5

3167 Accesses

6 Citations

Explore all metrics

This article presents a state-of-the-art overview of the sport management research discipline through a bibliometric analysis of publication data from the top five sport management journals in the decade 2011–2020. The analysis includes citation and productivity analysis of journals, institutions, countries, and articles, author citation and output analysis, and title and abstract (co-)word analysis. The data identifies the Sport Management Review as the most prolific journal of the last decade. Institutions and authors from the US are dominating the sport management research, which has increased its attractiveness in other disciplines. Co-word analysis shows recent and frequently discussed topics related to management of sport organizations and events, team and game, sport marketing and sponsorship, and behaviour and identification of the spectator. The article serves the ongoing debate on sport management as an academic field with deep insights into the publication structure and thematic dynamics of the last decade.

Similar content being viewed by others

Literature reviews as independent studies: guidelines for academic practice

How to design bibliometric research: an overview and a framework proposal

The journal coverage of Web of Science, Scopus and Dimensions: A comparative analysis

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Sport has become a weighty player embedded in the context of economic development (Ratten 2010 ). The growing economic relevance of sport created an organizational need for operational and managerial structure. Research at the intersection of sport and management has established a discipline that tackles the complexity of managerial activity in the sport environment. In the slipstream of the increasing influence of sport, sport management research has developed into an attractive and exponentially growing discipline (Funk 2019 ). However, the rapid and proliferating growth of sport management research, especially in the last decade (Pellegrini et al. 2020 ), has led to seemingly uncoordinated progress. As a result, it is difficult to assess the current status quo of the research discipline, as well as uncertainty about the prevailing dynamics that have influenced the development of the field in recent years.

In the period from 1990 to 2000, sport management was dominated by topics related to athletic training and athlete programs with less focus on the commercial potential of sport (Ciomaga 2013 ). In the penultimate decade, from 2000 to 2010, the thematic landscape of sport management has evolved in the opposite direction, with the focus of the field on commercial issues and becoming more oriented towards management disciplines (Ciomaga 2013 ). Ciomaga ( 2013 ) and Shilbury ( 2011a , b ) noted that marketing had the greatest impact on sport management research during these years, and that influence appeared to increase over time. This development was viewed with suspicion because the extensive commercial view of the multifaceted world of sport could lead to a neglect of its special qualities (Ciomaga 2013 ; Zeigler 2007 ). Almost as a logical consequence, Gammelsæter ( 2021 ) criticizes the prevailing conceptualization of sport as an industry or a business, which ignores natural features of sport such as its sociality. In the current conceptualization of sport entrepreneurship, a sub-area of sport management, Hammerschmidt et al. ( 2022 ) has recognized that ‘sport is social by nature and thus is sport entrepreneurship’ (p. 9), which apparently is the case for sport management. However, the discussion about the lack of conceptual clarity in sport management research was initiated early on, accompanied by recommendations that subsequent research addresses this deficit of clarity through systematic analyses (Chalip 2006 ).

To take a first step towards a better understanding of the status quo of a scientific discipline, a bibliometric analysis is a well-established method (Deyanova et al. 2022 ; Kraus et al. 2022 ; Martínez-López et al. 2018 ; Tiberius et al. 2020 , 2021 ). In recent years, few reviews have been conducted in the sport management discipline. Ciomaga ( 2013 ) combined a content-related review with a quantitative analysis of three leading sport management journals for the period 1987–2010. The study examines how sport management research strives for legitimacy and asserts that sport management research is still strongly influenced by its reference disciplines (e.g., marketing and organizational studies). To assess the state of development of the research field and its influence on generic disciplines, Shilbury ( 2011a ) examined citations of sport management and marketing journals in management and marketing journals. Results show that sport management and especially sport marketing literature has gained traction in top tier generic journals. In addition, Shilbury ( 2011a ) observed that it takes just over six years after a sport management journal’s creation until it’s expected to generate citations in journals outside the field. However, six of the seven analyzed journals were then not yet listed in the Social Science Citation Index (SSCI), which makes it difficult to draw a real picture of journal usage and consequently impact. Moreover, Shilbury ( 2011b ) analyzed citations of reference lists of manuscripts published in the Journal of Sport Management (JSM), Sport Marketing Quarterly (SMQ), European Sport Management Quarterly (ESMQ) and Sport Management Review (SMR). JSM is the journal with the longest history and was the most frequently cited journal, highlighting its role as the leading journal in the discipline. It is followed by SMQ with the second most citations, which is correspondingly the journal with the second-longest history. Apparently, the time factor played an important role because influence, citations, number of citable items, and reputation have developed over time (Budler et al. 2021 ).

Previous studies were important for a better understanding of the publishing behavior of sport management journals and provided a comprehensive overview of the fields’ development. However, the discipline has had the greatest growth in the last decade (Pellegrini et al. 2020 ) and the diffusion of new theories can take several years (Funk 2019 ). For example, when the analysis of Shilbury ( 2011a ) was conducted, only one sport management journal was listed in the SSCI, indicating that it may have been too early to obtain conclusive results from bibliometric analysis. Since then, many sport management and marketing journals have been listed in the SSCI for numerous years. It is particularly interesting to see how the sport management journals have performed in comparison since the analyses of Ciomaga ( 2013 ) and Shilbury ( 2011a , b ).

The aim of this bibliometric analysis is therefore to quantitatively structure the field using bibliometric indicators, and to assess the thematic dynamics of the last ten years with bibliometric coupling to contribute to the debate on the path that sport management is taking. To achieve this, a holistic bibliometric analysis is required due to the high demands on an integrated view of the complex scientific field (Gammelsæter 2021 ). This is mainly due to the multi-faceted nature of sport management, which can be easily illustrated by the role of a sport manager who takes care of issues in the organizational environment such as the desire to win, business, sport for development, professional marketing or social welfare (Hammerschmidt et al. 2021 ). Consequently, the methodological approach to achieve the research aim goes beyond related previous work.

A bibliometric analysis is a capable tool to identify the most influential journals based on publication and citation trends (Baumgartner and Pieters 2003 ; Martínez-López et al. 2018 ). In doing so, the study identifies important aspects in terms of citations, authors, articles, institutions, and countries. Ciomaga ( 2013 ) calls for studies to be conducted with more and particularly specialized journals. In response to this call, we conduct a bibliometric analysis that goes further than what has been done so far and analyses five of the leading sport management and marketing journals: Journal of Sport Management, Sport Management Review, European Sport Management Quarterly, International Journal of Sport Marketing & Sponsorship, and Sport Marketing Quarterly. The rationale for our selection of these five journals is their appearance in the SSCI. Whatever delimitations are set, bibliometric analyses can never provide a complete picture of the field, as recent work may not have reached its full bibliometric impact (Budler et al. 2021 ), but boundaries need to be set to manage the data, and given the work that has pre-dated this study, delimiting the scope of this work to a ten-year period since 2011 is logical.

The study is structured as follows. The next section explains in detail the methodology used for bibliometric analysis and data collection. The results of the bibliometric analysis are then presented, including basic bibliometric indicators, as well as leading institutions, countries, authors, and articles of the five journals. The bibliometric coupling and the analysis of the themes is then presented. Subsequently, the main findings are discussed, followed by the limitations and the conclusion in the last section.

2.1 Procedure

The method of bibliometric analysis aims to statistically and objectively map the current state of a scientific field and to quantitatively structure its publications (Merigó et al. 2018 ; Mukherjee et al. 2022 ). To obtain a holistic picture of the sport management scholarship, we performed several bibliometric procedures. Specifically, basic bibliometric indicators were calculated to analyze the top five sport management journals: publication behavior of specific institutions, citation measures of different countries, scientific productivity of authors within the field, and most cited articles in the field.

Quantitative numbers of publications indicate the scientific productivity and citation frequency reveals the influence of research (Luther et al. 2020 ; Shilbury 2011b ). In this context, the quantitative analysis offers a high level of objectivity (Zupic and Čater 2015 ). To measure the influence of journals in this study, the Impact Factor is used because compared to other metrics, such as CiteScore, the Impact Factor is still the more widely used and recognized metric and is more likely to reflect current developments because it is based on a smaller time frame (Kurmis 2003 ). Institutional and country data is collected to provide a potential basis for alternative explanations of thematic dynamics and trends (Ciomaga 2013 ). The results on authorship provide a useful basis for the interpretation of possible social influences within the scientific community (Small 2011 ). The analysis of the most cited articles offers information about what type of research can generate the most interest in the discipline (Ciomaga 2013 ).

The quantitative analysis includes additional metrics to evaluate the authors' research output: the h-index and the g-index. The h-index metric presents a balance between individual articles that achieve high citations, older articles, and articles with average citation counts (Alonso et al. 2009 ; Hirsch 2005 ). “A researcher has index h if h of his/her N p papers have at least h citations each, and the other ( N p − h ) papers have no more than h citations each” (Alonso et al. 2010 , p. 3). Thus, a h-index of 10 means that at least 10 articles have achieved 10 citations each. In addition, we present the g-index, which is intended to extend the h-index. Here, the threshold of achieved citations are exponentiated and aggregated (Egghe 2006 ). “A set of papers has a g -index g if g is the highest rank such that the top g papers have, together, at least g 2 citations. This also means that the top + 1 papers have less than ( g + 1) 2 cites” (Alonso et al. 2010 , p. 4). Hence, a g-index of 10 means that the top 10 articles of an author have collected at least 100 citations. Taken together, these two metrics give a sharper picture of the correlations between productivity figures and the influence of authors. Since the data base for these metrics is limited to sport management publications, the h- and g-indexes correspond to their sport management publications.

The data retrieved from the Social Science Citation Index (SSCI) is decisive to build networks of co-occurrences. Although there is no standard approach of a bibliometric analysis, the most common methodologies include the investigation of citations, co-citations and co-occurrences (Ferreira et al. 2015 ). In this study, the VOSviewer software is used to perform bibliometric coupling by means of a co-word analysis of titles and abstracts. This method processes the bibliometric data and then visualizes the relationships in a distance-based map. The representation simplifies the illustration of the bibliometric data and helps with the subsequent interpretation of the results (Luther et al. 2020 ). The aim of this work is not to synthesize the entire literature of the discipline, but rather the most mentioned themes. This inheres the danger of neglecting current trends and topics with little influence. Considering the research question, however, this is by no means a disadvantage, but provides clarity on the themes that were frequently discussed in the period under study.

To increase the depth of the results, this study performs a co-word density map. The density of a term depends on the number of nearby items and the number of citations they have. The density map shows how dense the research on a topic is. The denser the color, the more research is being done on that topic (van Eck and Waltman 2010 ). By combining a co-word map and a co-word density map, we get a more complete picture, because this shows which terms are mentioned the most and which ones gather the most science around them. The unified approach sheds more light on the underlying structure of bibliometric networks and therefore adds value compared to the isolated use of either approach (Waltman et al. 2010 ).

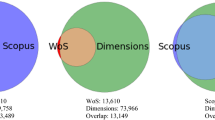

2.2 Data collection

The data were collected from the Social Science Citation Index (SSCI) using the Web of Science Core Collection™ (WoS). To be included, journals need to be directly related to either sport management or sport marketing, or both. Second, the journals need to be assigned with an Impact Factor in the journal citation report (JCR) at the time of the search. Table 1 provides an overview of the selected journals. The study is limited to published research between 2011 and 2020 that is labelled as either original or review articles, and excludes other types of articles. The search string was carried out on February 15, 2021.

This research contributes to the sport management discipline by providing a systematization of literature from the last decade. From 2011 to 2020, a total of 1516 articles (1417 articles and 79 reviews) were published in these five sport management journals by 1951 authors, belonging to 845 institutions from 49 countries.

3.1 Basic bibliometric indicators of the journals

The discipline of sport management and marketing is still a young area, as can be seen in Table 1 . The first sport management journal to be indexed in the WoS was the Journal of Sport Management, which first appeared in 1993. In 2007, a second journal was added, the International Journal of Sports Marketing & Sponsorship. The European Sport Management Quarterly was introduced one year later. There is an important quantitative leap until 2011 when the Sport Management Review was included in the index. Finally, the Sport Marketing Quarterly was indexed in 2014 and received the first Impact Factor in 2017.

The journal that contributes the most articles to the analysis is the Sport Management Review with 462 original articles or reviews, followed by the Journal of Sport Management with 410 articles or reviews.

The local citation score (LCS) indicates the number of citations the journal has received in the analyzed database of 1516 articles. The global citation score (GCS) indicates the number of citations that the journals’ articles have received throughout the WoS database. The LCS and GCS are aggregate data on the amount of citations and therefore, whether the variables are calculated for articles or journals, can be an indicator of influence (Mehri et al. 2014 ). On a general level, SMR is the most influential journal outside the discipline during the last decade, receiving 7557 citations (Table 1 ). It is followed at a large distance by JSM with 5985 citations and the European Sport Management Quarterly, which has 3719 citations in the general database of the WoS. The great influence of SMR is particularly notable considering that it is a very young journal in the WoS since it entered this index not until 2011. In addition, SMR received the highest Impact Factor (i.e., 6.577) in the field in 2020.

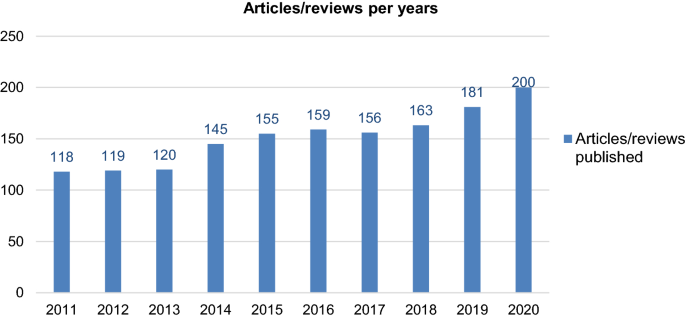

Figure 1 shows the development of published articles over the years. As more journals have been introduced into the WoS, the number of published articles has increased. However, the journals’ strategy of increasing the frequency of issues published per year to improve visibility and citation opportunities influenced the results. Growth has been steady, reaching the highest level in the historical series in 2020.

Total number of publications of the top five sport management journals

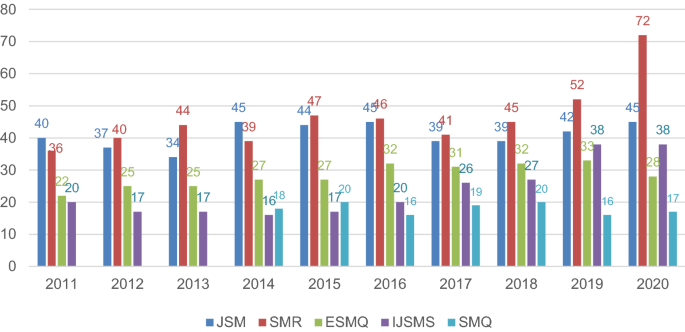

As far as the development of the number of published articles and reviews per journal is concerned, there is an upward trend for all of them (Fig. 2 ). In general, these journals have increased the number of their publications over the past decade. The journal that published the most articles in 2020 is SMR (72), followed by JSM (45) and IJSMS (38). In contrast, the journals that published the smallest number of articles in 2020 are ESMQ (28) and SMQ (17).

Number of publications of the top five sport management journals

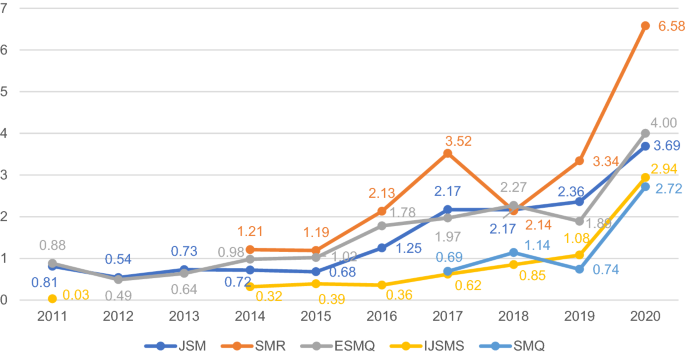

As can be observed, there is a general increase in the IF, especially in the last year (Fig. 3 ). The IF of JSM shows an upward trend (IF 2011–IF 2019 = 1.55) and presented the highest improvement in 2017. Regarding SMR, the IF also showed a positive trend from 2014 (first year with IF) to 2019 (IF 2011–IF 2019 = 2.13), reaching the highest value of the top five journals in 2019 (IF = 3.34). ESMQ has also shown a positive trend in IF in recent years (IF 2011–IF 2019 = 1.01). The highest growth of its IF was between 2015 and 2016 and the highest value was reached in 2018 with 2.27. However, in 2019, its Impact Factor decreased to 1.89.

Impact Factor of the top five sport management journals

For the IJSMS, there was a positive trend in IF from 2011 to 2020. Though, it had no IF in 2012 and 2013. Since then, its highest IF was reached in 2020 with 2.93. Finally, SMQ received its IF recently, in 2017, and it increased sharply in 2018 (IF = 1.14), but decreased in 2019 (IF = 0.74), showing similar values to 2017 (IF = 0.69).

3.2 Institutions and countries

Slightly more than half of the contributing authors (814) come from the US, followed by Australia (252) and the UK (173). The European country with the highest number of contributing authors is Germany (105).

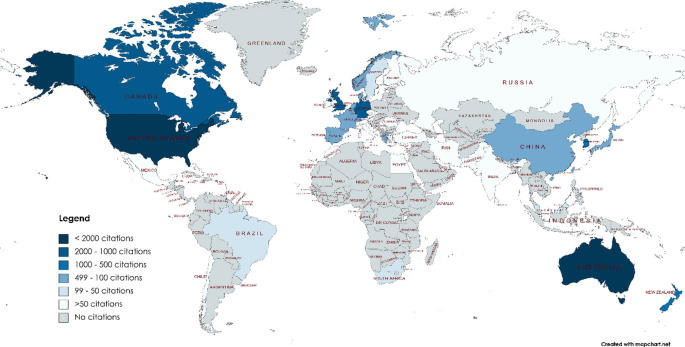

Figure 4 provides an overview of the most cited countries in the last decade. Darker colors indicate a higher number of citations. The US and Australia are the countries that have received the largest number of citations (> 2000 citations). However, it is important to highlight that the US is by far the country that has received the most citations (9834). The European country with the most citations is Germany (1589).

Number of articles published per country

Regarding the institutions, Griffith University ranks first by citation count in the WoS (1717), followed by Temple University, which is the second most cited university (1432). The University of Florida ranks third (1270). In addition, these three universities are also the most cited in searches within these five journals (LCS). The most productive institutions are Temple University with 96 articles, followed by Griffith University with 81, and the University of Florida with 79 published articles.

In terms of number of citations per article published in the WoS (GCS/Nb. Articles), the University of Technology Sydney ranks first (25.47), followed by Griffith University (21.20) in second, and Deakin University in third (20.72). University of Technology Sydney also ranked first in the number of citations per document published in these five journals (7.17) (see Table 2 ).

3.3 Authorship of published articles

We ranked the number of citations by author based on the date of data collection (February 15, 2021). The most outstanding authors are Funk with 850, Wicker with 618 and Breuer with a total of 581 citations in the WoS. Highly cited researchers are also highly productive. There is evidence that the number of publications is highly correlated with the number of citations (Parker et al. 2013 ). Looking at the number of publications of these authors, Funk stands out as the author of the field with the highest number of publications (39) in the mentioned sport management journals during the last ten years. In addition, Funk has the highest h-index with 19 and the highest g-index with 29. Both metrics indicate that his high number of publications is matched by a high number of citations. Therefore, he can be considered the most influential author in the discipline in absolute terms. Table 3 shows the most productive authors in sport management and marketing research. An additional way to determine the influence of authors is the number of citations received based on the number of articles published (Kostoff 2007 ). The GCS/Nb. index shows that Kaplanidou has the most global citations per published article with 35.55. The scholar is followed by Schulenkorf (31.20) and in third position is Lock with 30.35 citations per article.

Considering only the citations received in these five journals over the past ten years, the LCS/Nb. index shows that Lock has the most citations per article with 11.94. He is followed by Doherty with 10.57 and Yoshida with 10 citations per article.

The ten most cited articles in the WoS are displayed in Table 4 . It is noteworthy that the three most frequently cited articles are relatively recent literature reviews. SMR contributes seven articles and JSM contributes two articles, one is from ESMQ.

3.4 Co-word analysis

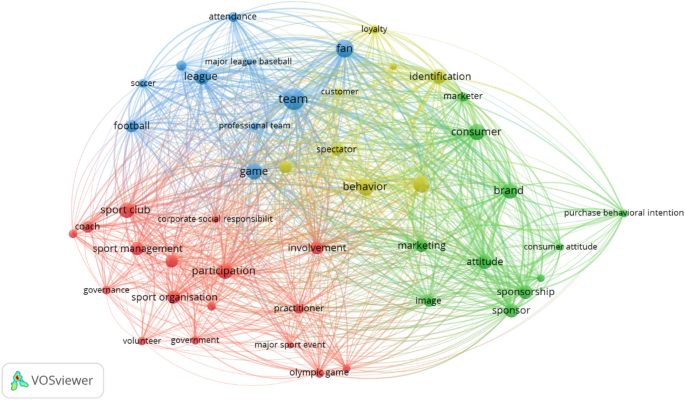

Figure 5 clusters the co-occurrence of words within titles and abstracts. The generated terms reflect frequently discussed topics in the literature. The relationships of the topics show four recurring thematic groups of the five sport management journals. Each color (blue, red, yellow, and green) corresponds to a theme and signals its group membership.

Co-word analysis of terms gathered in clusters

Figure 6 is a density map. A topic is denser if it has more terms nearby. Thus, the figure shows the interconnections and proximity of the themes to each other (van Eck and Waltman 2010 ). The range is displayed from yellow (most intense) to green, and blue (least intense).

Density map of co-word analysis

The co-word analysis revealed four thematic clusters. The red cluster (1) belongs to the management of sport organizations and events, the blue cluster (2) is about the team, fan and the game, the green cluster (3) is the sport marketing and sponsorship cluster, and the yellow cluster (4) is about the behavior and identification of the sport spectators.

3.4.1 Red: Examining the management of sport organizations

The red cluster is relatively diverse and appears to contain another subgroup. In principle, this thematic field is about the management of sport organizations, which are the origin of sport participation (Misener and Doherty 2009 ). This field is predestined to benefit from the knowledge of other disciplines. Thus, the principle of organizational capacity, a concept from the management discipline, can be a key determinant for the success of sport organizations (Hoeber and Hoeber 2012 ; Misener and Doherty 2009 ). However, sport organizations are exposed to unique circumstances and, therefore, a potential subject for research emanating from inside the field. An example of this is the research of volunteerism, which is currently in the conceptualization phase (Wicker 2017 ), but can be one of the most pressing issues of sport organizations in the future (Wicker et al. 2014 ).

3.4.2 Blue: the sport cluster about the team, the fan and the game

The blue cluster is much clearer and is dominated by only a few terms. It is somewhat surprising that team and identification appear in separate clusters, since team identification is one of the most developed concepts of sport management, especially within the last decade (Katz and Heere 2016 ; Lock and Heere 2017 ). This is probably due to the fact that the terms fan, team, game, and league create a kind of cluster of their own since they are typically mentioned together. They have apparently also connections to other topics (which can be observed at their central position) but should be seen more as a platform for gaining knowledge, rather than as a separate thematic field. The connection of the word pairs is also interesting because in the blue cluster, the fan, and fan attendance are connected, whereas the terms customer, spectator, and behavior appear in the yellow cluster. The blue cluster seems to have evolved out of sport because of the terminology, whereas the yellow cluster is obviously characterized by commercial concepts (consumer, spectator, behavior, identification). The blue cluster is also the only cluster that includes a specific sport, namely major league baseball and especially football (soccer).

3.4.3 Green: developing marketing and sponsorship in sports

Marketing is part of the green cluster, however, neither the co-word analysis nor the density map reveals an increased appearance or influence of the term marketing. However, this refers only to the term in the analysis, not to the influence of the marketing topic in general. The way in which sport is consumed is of great value for practitioners. They try to provide pleasurable sport experiences by focusing on service quality and customer satisfaction, which is based on knowledge about how sport is consumed (Funk et al. 2016 ). Sport consumer research is a popular and growing sub-discipline of sport marketing research (Funk 2017 ; Yoshida 2017 ). Sponsorships most prominent context is sport, and generated insights have the potential to impact generic disciplines. For example, sport management research is discussing whether a consumer can identify non-congruent messages in sport marketing more easily than congruent, consistent information (Alonso Dos Santos and Calabuig 2018 ).

3.4.4 Yellow: investigating the commercial aspect of the spectator

Research within the yellow cluster focuses on diverse aspects related to spectator identification, loyalty, and behavior with sport (Lock et al. 2012 ). The terms of the yellow cluster are strongly linked to the concept of team identification, which in turn is strongly linked to marketing research (Heere et al. 2011 ; Katz et al. 2018 ). Psychology also has a great influence on the yellow cluster. Chang et al. ( 2018 ) used the approach of cognitive psychology to create the concept of implicit team identification (iTeam ID). By integrating the unconscious nature of consumption, iTeam ID may provide sport marketers with new insights for understanding fans’ identification with teams.

The density map (Fig. 6 ) shows that the term ‘team’ has the highest density in the field, indicating that more researchers are conducting research related to topics that mention the term team. The terms sport club, sport management, and sport organization are also presented with a high degree of density and would likely overtake the term ‘team’ if more consistent terminology were used. Terms such as league, game, fan, behavior, consumer, identification, participation, sponsorship, and sponsor also have a high density and are all presented in a more concentrated color than the term marketing.

4 Discussion

4.1 productivity and citations.

Despite its relative newness to the WoS, SMR is the most influential journal in the sport management discipline in our analysis of the last decade. During this period, it published the most articles, collected the most local and global citations, and had the highest Impact Factor among the top 5 journals in sport management. In addition, 7 of the 10 most cited articles, including the one with the most citations, were published in SMR. Hence, our study reveals a potential shift from the Journal of Sport Management as the most influential journal in sport management to SMR.

Productivity in the analyzed journals has been dominated by the US. The majority of authors come from the US, indeed the number is eight times higher compared to the European country with the most contributing authors: Germany. However, among the 3 most cited authors in the field are two Germans (Wicker and Breuer), which, by the way, count for 76% of all German citations with 1199 out of 1589 citations. The most cited article comes from an Australian university. The dominance of the US therefore seems to be less due to the quality (what can be derived from the values of LCS and GCS per article), but much more due to the quantity of researchers from the US contributing to sport management. The high number of researchers from the US seems to have an influence on the topics discussed. Sport in the US is more commercial in its basic concept, and community-sport organizations have less influence than is the case in Canada or Europe (Misener and Doherty 2009 ), which in turn may be part of the explanation why commercial logic has taken over in the sport management literature. It is further surprising that the term football is so prominently represented, even though football is called soccer in the US and plays a minor role. Conversely, this indicates that the scholarship of other nations focuses all the more on football.

In terms of authorship, a two-sided picture emerges. On the one hand, there are authors like Kaplanidou and Schulenkorf who have achieved high GCS scores and thus many citations outside the sport management journals. The articles by Kaplanidou were focused on the field of sport events and sport tourism. The most influential articles by Schulenkorf belong to sport for development literature and the most influential article is a review on sport for development, which accounts for a good quarter of the total global citations. Without this article, the value would fall back to the midfield. Research in these areas thus seems well suited to be cited by disciplines outside the field, but less suited to generate traction within the field. In terms of local citations, however, research on consumer satisfaction/behavior and sport organizations, respectively done by Yoshida and Doherty, are leading the scoring board. Lock is the only one whose research on team identification is frequently cited, both within and outside the sport management discipline. This possibly stems from the fact that Lock is also a co-author in other areas, such as sport and social media, eSports or sport consumption, and therefore has a very diverse research portfolio. Whether these findings about the choice of a topic and its influence on citation generation can be systematically replicated remains unclear. It can, however, support academics in choosing future projects and contributes to Funk's ( 2019 ) findings that on the one hand the ‘How?’ influences the diffusion of knowledge and on the other hand the ‘What?’ influences where knowledge can generate impact.

In Ciomaga's ( 2013 ) analysis, the papers with the most citations were reviews. Likewise, the three most cited articles in this analysis are reviews, a phenomenon that can also be observed in other disciplines (Vallaster et al. 2019 ). Surprisingly, the three authors with the most citations do not have an article in the top cited article list. However, the authors also have high scores in the h- and g-indexes, which means that they are highly productive, but also able to gain traction in terms of citations.

4.2 Exploring the thematic complexity of sport management research

In the results section, the thematic clusters were presented and their content discussed. In this section, we link our results to the ongoing debate in some substantive areas within sport management research.

The most obvious finding when looking at the visualization of co-occurrences is also the most influential: the thematic map of sport management research has become more diverse. The thematic complexity of the discipline that we present in our study contrasts significantly with the previous one-dimensionality of issues. Previous reflections mentioned that the focus of sport management research was characterized by a lack of systematic management strategies (Slack 1998 ) and then oscillated to an over-representation of commercial logic (Chalip 2006 ; Ciomaga 2013 ; Gammelsæter 2021 ). Our findings have carved out four thematic clusters and two of them, namely the green cluster on sport marketing and sponsorship and the red cluster on the management of sport organizations and events, are noticeably influenced by management disciplines and commercial thinking. However, both also show research streams that intend only to apply theories from other disciplines in the sport context, but to develop their own theories concerning, for example, the voluntary work of sport clubs, the management of community-sport-organizations or the peculiarities of sport sponsorship. The yellow cluster remains vague in this respect. On the one hand, this thematic group is also dominated by a commercial perspective and deals with the fundamental question of what motivates a spectator to consume sport. In this context, spectators are also referred to as customers, a term normally used in business. On the other hand, sport management scholars managed to establish a firm basis of evidence around the team identification topic. This thematic area, while based on identity theory and the social identity approach, has subsequently built up a sport-specific and data-based knowledge base step by step, rather than accumulating theories through the constant introduction of new general management theories.

The blue cluster in this analysis is a novelty and represents a dominant thematic field of sport management that deals with sport specific characteristics: the team, the fan, the league, and the game. This cluster represents a thematic development of the last decade in sport management research, which is in line with the demand to put sport back into the center of sport management (Gammelsæter 2021 ). It is also important to note that the term ‘team’ is the term on which most research has been conducted. However, this conclusion may also be deceptive, as other thematic fields have greater diversity in the use of terms and, cumulatively, would likely yield more influential scores.

In general, commercial research areas continue to dominate the field. A common characteristic of these topics is that they are related to important sources of income and, hence, the findings are relevant from the perspective of practitioners as well. Sport has its grassroots in voluntary, community-based sport clubs. Despite the ongoing professionalization of sport, most sport organizations have a social background and are non-profit (Misener and Doherty 2009 ). As Morrow ( 2013 ) notes, sport ‘has always been and continues to be […] economic in basis, but social in nature’ (p. 297). In contrast, the term ‘social’ was not represented in our analysis and therefore future research could take a more holistic approach and engage in distinct social aspects of managing sport.

Football (soccer) is the only sport besides major league baseball that appears in the co-word analysis. Moreover, both terms, i.e., soccer and football, are still represented and together their influence would be mapped even more strongly. Nevertheless, football is the most represented sport in the sport management journals in our analysis, thus underlining its significant and leading role in research.

Looking at the development of sport management topics in the past, it is interesting to note that these have grown mainly within sport management journals. Shilbury ( 2011a ) noted that only 25 sport management related papers were published in generic management journals. In contrast, sport entrepreneurship, a young and emerging sub stream of management research in sport, has originated from the field of entrepreneurship and mainly grown up outside the major sport management and marketing journals. Sport entrepreneurship attaches great importance to the specifics of sport (Hammerschmidt et al. 2020 , 2022 ) and can therefore help to support the missing distinctiveness of sport management (Shilbury 2011b ). It remains open whether it is a trend or an exception that new sub streams arise outside the discipline.

4.3 Bridging sport management facets: an integrative view

The integrated view of sport management is a holistic approach that considers the various aspects of sport managements research. This approach recognizes that, for example, the success of a sport organization is not solely dependent on one aspect, such as management or marketing, but rather on the interrelationship of all elements.

In our analysis, we were able to depict the multi-faceted landscape of topics in sport management over the past decade. As described above, the dominant themes and ultimately the concepts and theories that emerged from them can be traced back to a strong influence of commercially oriented generic management research. This commercial focus runs throughout the discipline of sport management. Interestingly, however, the inherent tasks of managing sport lead to a much more diverse landscape of topics. Therefore, the integrative view of sport management does not refer to focused topics, but attempts to point out the multi-faceted nature of sport management through a holistic approach.

An integrated view of sport management considers the management of sport organizations, including the development of unique and sport-specific theories that address the unique challenges and opportunities presented by the sport industry. This approach also includes the marketing and sponsorship of sport events and the spectator sport experience. In addition, an integrated view of sport management considers the volunteerism and community engagement aspect of sport organizations, recognizing the important role that volunteers play in the sport management discipline. This approach also embraces the role of sport in promoting social development, for example, through the use of sport as a means of education and promoting healthy lifestyles. The integrated view of sport management thus allows for a better understanding of the sport industry as a whole and the interactions between the different elements of the industry. This can lead to better prediction of industry trends and a more accurate understanding of the competitive landscape. The integrated view of sport management is a holistic approach that considers all aspects of sport organizations and events. Therefore, the integrative view offers opportunities for unique and sport-specific theories, and allows for more effective strategies and decision-making by recognizing the interrelatedness of the sport management elements.

4.4 Sport management research on the rise: a sport-specific perspective

The results of the study underline that sport management research has been attractive outside the field over the last decade. Many of the papers published in sport management and marketing journals are cited in journals from other fields. The ten most cited articles presented in this study show high citation indicators in the general WoS database and are good proof that research in sport management attracts the interest of the larger scientific community. This underlines the findings of Ciomaga ( 2013 ) who analyzed sport management research following the direction of a reference discipline as a trend.

One possible explanation for the increased influence of sport management research is provided by the assumption of Ciomaga ( 2013 ) that sport management research has increasingly shown the ability to build unique theories and thus may become a reference discipline. In this study, we presented the main thematic clusters of sport management research and showed that there are research areas characterized by a gradual development of unique theories. One of these areas is volunteer management in sport, the theories of which are well-developed due to their great relevance for sport clubs and sport events and thus play a leading role in volunteerism research. Another topic is sport for development, of which two articles appear in the ten most cited articles. The term already indicates that these are developed findings from a sport management sub stream that focuses primarily on sport-specific contexts. In addition, the development within the topic area of team identification is noteworthy. The articles we analyzed showed a steady theoretical development because they built on each other stepwise with a high degree of consistency. Although the number of articles in the field of team identification is comparatively small, well-researched and advanced theories and concepts have been developed. Moreover, it has been shown that sport management research has grown and the topics of the discipline have become more diverse, which logically has increased the number and possibilities of theories to be used for other disciplines. In addition, the blue cluster presented in this study (terms: team, fan, league, game) shows a greater cohesion to sport-specific topics compared to the dominant topics presented so far, suggesting that more unique sport management theory is emerging. However, the methods presented in this study cannot answer the question of how sport management research has increased its attractiveness in other disciplines and whether this is related to the emergence of unique theories.

In essence, a reference discipline states its progress of knowledge by getting cited by other disciplines (Shilbury 2011b ). Being a reference discipline is strongly linked to the fundamental debate on conceptual clarity of sport management. The ability to create theories reinforces the view that sport has a special quality (Gammelsæter 2021 ), whereas the application of theory from broader disciplines to sport management suggests that it is rather a sub-discipline of management (Ciomaga 2013 ). Regardless of which way is chosen to generate knowledge in sport management, it should be considered that the diffusion of new theories in sport management proves to be a slow and uncomfortable process (Funk 2019 ). The ongoing debate shows that sport management is still in its discovery phase.

5 Conclusion

This study applied the bibliometric method to analyze the five leading journals in sport management and marketing literature (Journal of Sport Management, Sport Management Review, European Sport Management Quarterly, International Journal of Sport Marketing & Sponsorship, and Sport Marketing Quarterly). The analysis covers data of 1516 articles in the period from 2011 to 2020 and leads to theoretical and practical contributions in several ways.

The bibliometric analysis allowed us to identify key authors, institutions and journals in the field, as well as the mapping of research trends and patterns over time. Our analysis shows that authors from the US dominate, not qualitatively but quantitatively, and suggests that their focus may be part of the explanation why the theoretical structure of the sport management field is highly commercialized. Despite the US dominance, the term football is prominently represented suggesting that football (soccer) is a popular empirical setting for sport management research. In terms of thematic development, commercial thinking in sport management has become firmly entrenched within the discipline and an abrupt change in the prevailing paradigms seems naïve, even if it neglects sport-specific idiosyncrasies as a result. One of these idiosyncrasies is the inherent social nature of sport (Morrow 2013 ), which receives hardly any attention in sport management. The result of our co-word analysis showed that there are four dominant thematic clusters in the field (management of sport organizations and events; team, fan and the game; marketing and sponsorship; behavior and identification of the spectator). Despite the dominance of commercial topics, the cluster around the team, fan and game seems to have evolved out of sport with a focus on the sporting aspect. Moreover, Ciomaga ( 2013 ) predicted that research within sport management will ‘follow lines of research on sport that have been legitimized by reference disciplines’ (p. 572). The analyses of this study indicate that the influence of sport management literature on other disciplines is growing. In addition, developments in substantive areas and the introduction of sport-specific theories in several contexts, including volunteerism, sport for development, or team identification are emerging within the discipline. This enriches the field in diversity and has the potential to (a) drive a paradigm shift to put sport back in the spotlight and (b) increase the legitimacy of the field through growing influence on other disciplines.

On the practical side, our analysis showed that SMR is, in the period under study, the leading journal in almost every productivity category which can be a useful information for authors looking to publish their work, or for organizations and institutions to identify potential partners or competitors. In addition, the analysis of citation data support authors in future articles by showing what research achieved high popularity. Within the study period, reviews in particular achieved high citation scores. Articles in the field of sport for developments, sport events and sport tourism were cited remarkably often outside the discipline. Within sport management, articles in the thematic area of consumer behavior and sport organization in particular achieved high citation values.

The presented findings in this study are constrained by various limitations. Quantitative data were collected from the Social Sciences Citation Index (SSCI) of the Web of Science database. Hence, the limitations of the database also limit the results of this study. Therefore, future studies may select other sport management and marketing journals indexed in other databases (e.g. Scopus) and perform a bibliometric analysis to compare the themes and trends with the results obtained in this study. Further, recognizing scientific contributions and developing academic impact takes time (Xi et al. 2015 ). As a result, recently published articles were yet not able to unfold their full potential and have relatively lower impact than well-established papers in the field. In addition, the journals’ impact was measured based on their scientific productivity, which is influenced by the time period of being indexed in the WoS. As a consequence, we created indexes by putting absolute numbers in relation, like citations per article or global citation score per year. Further, our approach mainly rests on quantitative metrics and the results should therefore not be used to evaluate the research quality of countries, journals, or individual articles and authors. The results can contribute to making such assessments, but we suggest to refrain from using any of the rankings presented here as a direct measure of research quality.

Data availability

No data will be made available for this article.

Alonso S, Cabrerizo FJ, Herrera-Viedma E, Herrera F (2009) h-Index: a review focused in its variants, computation and standardization for different scientific fields. J Informetr 3(4):273–289. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joi.2009.04.001

Article Google Scholar

Alonso S, Cabrerizo F, Herrera-Viedma E, Herrera F (2010) hg-index: a new index to characterize the scientific output of researchers based on the h-and g-indices. Scientometrics 82(2):391–400

Alonso Dos Santos M, Calabuig F (2018) Assessing the effectiveness of sponsorship messaging: measuring the impact of congruence through electroencephalogram. Int J Sports Mark Spons 19(1):25–40. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJSMS-09-2016-0067

Baumgartner H, Pieters R (2003) The structural influence of marketing journals: a citation analysis of the discipline and its subareas over time. J Mark 67(2):123–139. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkg.67.2.123.18610

Budler M, Župič I, Trkman P (2021) The development of business model research: a bibliometric review. J Bus Res 135:480–495. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2021.06.045

Chalip L (2006) Toward a distinctive sport management discipline. J Sport Manag 20(1):1–21. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.20.1.1

Chang Y, Wann DL, Inoue Y (2018) The effects of implicit team identification (iTeam ID) on revisit and WOM intentions: a moderated mediation of emotions and flow. J Sport Manag 32(4):334–347. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.2017-0249

Ciomaga B (2013) Sport management: a bibliometric study on central themes and trends. Eur Sport Manag Q 13(5):557–578. https://doi.org/10.1080/16184742.2013.838283

Deyanova K, Brehmer N, Lapidus A, Tiberius V, Walsh S (2022) Hatching start-ups for sustainable growth: a bibliometric review on business incubators. Rev Manag Sci 16:2083–2109

Egghe L (2006) Theory and practise of the g-index. Scientometrics 69(1):131–152. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-006-0144-7

Ferreira MP, Reis NR, Miranda R (2015) Thirty years of entrepreneurship research published in top journals: analysis of citations, co-citations and themes. J Glob Entrep Res. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40497-015-0035-6

Funk DC (2017) Introducing a Sport Experience Design (SX) framework for sport consumer behaviour research. Sport Manag Rev 20(2):145–158. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smr.2016.11.006

Funk DC (2019) Spreading research uncomfortably slow: insight for emerging sport management scholars. J Sport Manag 33(1):1–11. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.2018-0315

Funk DC, Lock D, Karg A, Pritchard M (2016) Sport consumer behavior research: improving our game. J Sport Manag 30(2):113–116. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.2016-0028

Gammelsæter H (2021) Sport is not industry: bringing sport back to sport management. Eur Sport Manag Q 21(2):257–279. https://doi.org/10.1080/16184742.2020.1741013

Hammerschmidt J, Eggers F, Kraus S, Jones P, Filser M (2020) Entrepreneurial orientation in sports entrepreneurship—a mixed methods analysis of professional soccer clubs in the German-speaking countries. Int Entrep Manag J 16(3):839–857. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-019-00594-5

Hammerschmidt J, Durst S, Kraus S, Puumalainen K (2021) Professional football clubs and empirical evidence from the COVID-19 crisis: time for sport entrepreneurship? Technol Forecast Soc Change 165:120572. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2021.120572

Hammerschmidt J, Kraus S, Jones P (2022) Sport entrepreneurship: defnition and conceptualization. J Small Bus Strategy. https://doi.org/10.5370/001c.31718

Heere B, James J, Yoshida M, Scremin G (2011) The effect of associated group identities on team identity. J Sport Manag 25(6):606–621. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.25.6.606

Hirsch JE (2005) An index to quantify an individual’s scientific research output. Proc Natl Acad Sci 102(46):16569–16572. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0507655102

Hoeber L, Hoeber O (2012) Determinants of an innovation process: a case study of technological innovation in a community sport organization. J Sport Manag 26(3):213–223. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.26.3.213

Katz M, Heere B (2016) New team, new fans: a longitudinal examination of team identification as a driver of university identification. J Sport Manag 30(2):135–148. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.2014-0258

Katz M, Ward RM, Heere B (2018) Explaining attendance through the brand community triad: integrating network theory and team identification. Sport Manag Rev 21(2):176–188. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smr.2017.06.004

Kostoff RN (2007) The difference between highly and poorly cited medical articles in the journal Lancet. Scientometrics 72(3):513–520. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-007-1573-7

Kraus S, Breier M, Lim WM, Dabić M, Kumar S, Kanbach D, Mukherjee D, Corvello V, Piñeiro-Chousa J, Liguori E, Palacios-Marqués D, Schiavone F, Ferraris A, Fernandes C, Ferreira JJ (2022) Literature reviews as independent studies: guidelines for academic practice. Rev Manag Sci 16(8):2577–2595. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11846-022-00588-8

Kurmis AP (2003) Understanding the limitations of the journal impact factor. J Bone Joint Surg 85(12):2449–2454

Lock D, Heere B (2017) Identity crisis: a theoretical analysis of ‘team identification’research. Eur Sport Manag Q 17(4):413–435. https://doi.org/10.1080/16184742.2017.1306872

Lock D, Taylor T, Funk DC, Darcy S (2012) Exploring the development of team identification. J Sport Manag 26(4):283–294. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.26.4.283

Luther L, Tiberius V, Brem A (2020) User experience (UX) in business, management, and psychology: a bibliometric mapping of the current state of research. Multimodal Technol Interact 4(2):18. https://doi.org/10.3390/mti4020018

Martínez-López FJ, Merigó JM, Valenzuela-Fernández L, Nicolás C (2018) Fifty years of the European Journal of Marketing: a bibliometric analysis. Eur J Mark 52(1/2):439–468. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJM-11-2017-0853

Mehri S, Ammar J, Sedighi M, Jalalimanesh A (2014) Mapping research trends in the field of knowledge management. Malays J Libr Inf Sci 19(1):71–85

Google Scholar

Merigó JM, Pedrycz W, Weber R, de la Sotta C (2018) Fifty years of Information Sciences: a bibliometric overview. Inf Sci 432:245–268. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ins.2017.11.054

Misener K, Doherty AH (2009) A case study of organizational capacity in nonprofit community sport. J Sport Manag 23(4):457–482. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.23.4.457

Morrow S (2013) Football club financial reporting: time for a new model? Sport Bus Manag Int J 3(4):297–311. https://doi.org/10.1108/SBM-06-2013-0014

Mukherjee D, Lim WM, Kumar S, Donthu N (2022) Guidelines for advancing theory and practice through bibliometric research. J Bus Res 148:101–115

Parker JN, Allesina S, Lortie CJ (2013) Characterizing a scientific elite (B): publication and citation patterns of the most highly cited scientists in environmental science and ecology. Scientometrics 94(2):469–480. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-012-0859-6

Pellegrini MM, Rialti R, Marzi G, Caputo A (2020) Sport entrepreneurship: a synthesis of existing literature and future perspectives. Int Entrep Manag J. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-020-00650-5

Ratten V (2010) Developing a theory of sport-based entrepreneurship. J Manag Organ 16(4):557–565

Shilbury D (2011a) A bibliometric study of citations to sport management and marketing journals. J Sport Manag 25(5):423–444. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.25.5.423

Shilbury D (2011b) A bibliometric analysis of four sport management journals. Sport Manag Rev 14(4):434–452. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smr.2010.11.005

Slack T (1998) Is there anything unique about sport management? Eur J Sport Manag 5:21–29

Small H (2011) Interpreting maps of science using citation context sentiments: a preliminary investigation. Scientometrics 87(2):373–388. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-011-0349-2

Tiberius V, Siglow C, Sendra-García J (2020) Scenarios in business and management: the current stock and research opportunities. J Bus Res 121:235–242

Tiberius V, Schwarzer H, Roig-Dobón S (2021) Radical innovations: between established knowledge and future research opportunities. J Innov Knowl 6(3):145–153

Vallaster C, Kraus S, Lindahl JMM, Nielsen A (2019) Ethics and entrepreneurship: a bibliometric study and literature review. J Bus Res 99:226–237. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.02.050

van Eck NJ, Waltman L (2010) Software survey: VOSviewer, a computer program for bibliometric mapping. Scientometrics 84(2):523–538. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-009-0146-3

Waltman L, van Eck NJ, Noyons ECM (2010) A unified approach to mapping and clustering of bibliometric networks. J Informetr 4(4):629–635. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joi.2010.07.002

Wicker P (2017) Volunteerism and volunteer management in sport. Sport Manag Rev 20(4):325–337. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smr.2017.01.001

Wicker P, Breuer C, Lamprecht M, Fischer A (2014) Does club size matter: an examination of economies of scale, economies of scope, and organizational problems. J Sport Manag 28(3):266–280. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.2013-0051

Xi JM, Kraus S, Filser M, Kellermanns FW (2015) Mapping the field of family business research: past trends and future directions. Int Entrep Manag J 11(1):113–132. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-013-0286-z

Yoshida M (2017) Consumer experience quality: a review and extension of the sport management literature. Sport Manag Rev 20(5):427–442. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smr.2017.01.002

Zeigler EF (2007) Sport management must show social concern as it develops tenable theory. J Sport Manag 21(3):297–318. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.21.3.297

Zupic I, Čater T (2015) Bibliometric methods in management and organization. Organ Res Methods 18(3):429–472. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428114562629

Download references

Open access funding provided by Libera Università di Bolzano within the CRUI-CARE Agreement. There was no funding for this article. The authors did not receive support from any organization for the submitted work.

Author information