- Clerc Center | PK-12 & Outreach

- KDES | PK-8th Grade School (D.C. Metro Area)

- MSSD | 9th-12th Grade School (Nationwide)

- Gallaudet University Regional Centers

- Parent Advocacy App

- K-12 ASL Content Standards

- National Resources

- Youth Programs

- Academic Bowl

- Battle Of The Books

- National Literary Competition

- Youth Debate Bowl

- Bison Sports Camp

- Discover College and Careers (DC²)

- Financial Wizards

- Immerse Into ASL

- Alumni Relations

- Alumni Association

- Homecoming Weekend

- Class Giving

- Get Tickets / BisonPass

- Sport Calendars

- Cross Country

- Swimming & Diving

- Track & Field

- Indoor Track & Field

- Cheerleading

- Winter Cheerleading

- Human Resources

- Plan a Visit

- Request Info

- Areas of Study

- Accessible Human-Centered Computing

- American Sign Language

- Art and Media Design

- Communication Studies

- Data Science

- Deaf Studies

- Early Intervention Studies Graduate Programs

- Educational Neuroscience

- Hearing, Speech, and Language Sciences

- Information Technology

- International Development

- Interpretation and Translation

- Linguistics

- Mathematics

- Philosophy and Religion

- Physical Education & Recreation

- Public Affairs

- Public Health

- Sexuality and Gender Studies

- Social Work

- Theatre and Dance

- World Languages and Cultures

- B.A. in American Sign Language

- B.A. in Art and Media Design

- B.A. in Biology

- B.A. in Communication Studies

- B.A. in Communication Studies for Online Degree Completion Program

- B.A. in Deaf Studies

- B.A. in Deaf Studies for Online Degree Completion Program

- B.A. in Education with a Specialization in Early Childhood Education

- B.A. in Education with a Specialization in Elementary Education

- B.A. in English

- B.A. in Government

- B.A. in Government with a Specialization in Law

- B.A. in History

- B.A. in Interdisciplinary Spanish

- B.A. in International Studies

- B.A. in Interpretation

- B.A. in Mathematics

- B.A. in Philosophy

- B.A. in Psychology

- B.A. in Psychology for Online Degree Completion Program

- B.A. in Social Work (BSW)

- B.A. in Sociology

- B.A. in Sociology with a concentration in Criminology

- B.A. in Theatre Arts: Production/Performance

- B.A. or B.S. in Education with a Specialization in Secondary Education: Science, English, Mathematics or Social Studies

- B.S in Risk Management and Insurance

- B.S. in Accounting

- B.S. in Accounting for Online Degree Completion Program

- B.S. in Biology

- B.S. in Business Administration

- B.S. in Business Administration for Online Degree Completion Program

- B.S. in Information Technology

- B.S. in Mathematics

- B.S. in Physical Education and Recreation

- B.S. In Public Health

- General Education

- Honors Program

- Peace Corps Prep program

- Self-Directed Major

- M.A. in Counseling: Clinical Mental Health Counseling

- M.A. in Counseling: School Counseling

- M.A. in Deaf Education

- M.A. in Deaf Education Studies

- M.A. in Deaf Studies: Cultural Studies

- M.A. in Deaf Studies: Language and Human Rights

- M.A. in Early Childhood Education and Deaf Education

- M.A. in Early Intervention Studies

- M.A. in Elementary Education and Deaf Education

- M.A. in International Development

- M.A. in Interpretation: Combined Interpreting Practice and Research

- M.A. in Interpretation: Interpreting Research

- M.A. in Linguistics

- M.A. in Secondary Education and Deaf Education

- M.A. in Sign Language Education

- M.S. in Accessible Human-Centered Computing

- M.S. in Speech-Language Pathology

- Master of Social Work (MSW)

- Au.D. in Audiology

- Ed.D. in Transformational Leadership and Administration in Deaf Education

- Ph.D. in Clinical Psychology

- Ph.D. in Critical Studies in the Education of Deaf Learners

- Ph.D. in Hearing, Speech, and Language Sciences

- Ph.D. in Linguistics

- Ph.D. in Translation and Interpreting Studies

- Ph.D. Program in Educational Neuroscience (PEN)

- Individual Courses and Training

- Certificates

- Certificate in Sexuality and Gender Studies

- Educating Deaf Students with Disabilities (online, post-bachelor’s)

- American Sign Language and English Bilingual Early Childhood Deaf Education: Birth to 5 (online, post-bachelor’s)

- Peer Mentor Training (low-residency/hybrid, post-bachelor’s)

- Early Intervention Studies Graduate Certificate

- Online Degree Programs

- ODCP Minor in Communication Studies

- ODCP Minor in Deaf Studies

- ODCP Minor in Psychology

- ODCP Minor in Writing

- Online Degree Program General Education Curriculum

- University Capstone Honors for Online Degree Completion Program

Quick Links

- PK-12 & Outreach

- NSO Schedule

Guide to Writing Introductions and Conclusions

202.448-7036

First and last impressions are important in any part of life, especially in writing. This is why the introduction and conclusion of any paper – whether it be a simple essay or a long research paper – are essential. Introductions and conclusions are just as important as the body of your paper. The introduction is what makes the reader want to continue reading your paper. The conclusion is what makes your paper stick in the reader’s mind.

Introductions

Your introductory paragraph should include:

1) Hook: Description, illustration, narration or dialogue that pulls the reader into your paper topic. This should be interesting and specific.

2) Transition: Sentence that connects the hook with the thesis.

3) Thesis: Sentence (or two) that summarizes the overall main point of the paper. The thesis should answer the prompt question.

The examples below show are several ways to write a good introduction or opening to your paper. One example shows you how to paraphrase in your introduction. This will help you understand the idea of writing sequences using a hook, transition, and thesis statement.

» Thesis Statement Opening

This is the traditional style of opening a paper. This is a “mini-summary” of your paper.

For example:

» Opening with a Story (Anecdote)

A good way of catching your reader’s attention is by sharing a story that sets up your paper. Sharing a story gives a paper a more personal feel and helps make your reader comfortable.

This example was borrowed from Jack Gannon’s The Week the World Heard Gallaudet (1989):

Astrid Goodstein, a Gallaudet faculty member, entered the beauty salon for her regular appointment, proudly wearing her DPN button. (“I was married to that button that week!” she later confided.) When Sandy, her regular hairdresser, saw the button, he spoke and gestured, “Never! Never! Never!” Offended, Astrid turned around and headed for the door but stopped short of leaving. She decided to keep her appointment, confessing later that at that moment, her sense of principles had lost out to her vanity. Later she realized that her hairdresser had thought she was pushing for a deaf U.S. President. Hook: a specific example or story that interests the reader and introduces the topic.

Transition: connects the hook to the thesis statement

Thesis: summarizes the overall claim of the paper

» Specific Detail Opening

Giving specific details about your subject appeals to your reader’s curiosity and helps establish a visual picture of what your paper is about.

» Open with a Quotation

Another method of writing an introduction is to open with a quotation. This method makes your introduction more interactive and more appealing to your reader.

» Open with an Interesting Statistic

Statistics that grab the reader help to make an effective introduction.

» Question Openings

Possibly the easiest opening is one that presents one or more questions to be answered in the paper. This is effective because questions are usually what the reader has in mind when he or she sees your topic.

Source : *Writing an Introduction for a More Formal Essay. (2012). Retrieved April 25, 2012, from http://flightline.highline.edu/wswyt/Writing91/handouts/hook_trans_thesis.htm

Conclusions

The conclusion to any paper is the final impression that can be made. It is the last opportunity to get your point across to the reader and leave the reader feeling as if they learned something. Leaving a paper “dangling” without a proper conclusion can seriously devalue what was said in the body itself. Here are a few effective ways to conclude or close your paper. » Summary Closing Many times conclusions are simple re-statements of the thesis. Many times these conclusions are much like their introductions (see Thesis Statement Opening).

» Close with a Logical Conclusion

This is a good closing for argumentative or opinion papers that present two or more sides of an issue. The conclusion drawn as a result of the research is presented here in the final paragraphs.

» Real or Rhetorical Question Closings

This method of concluding a paper is one step short of giving a logical conclusion. Rather than handing the conclusion over, you can leave the reader with a question that causes him or her to draw his own conclusions.

» Close with a Speculation or Opinion This is a good style for instances when the writer was unable to come up with an answer or a clear decision about whatever it was he or she was researching. For example:

» Close with a Recommendation

A good conclusion is when the writer suggests that the reader do something in the way of support for a cause or a plea for them to take action.

202-448-7036

At a Glance

- Quick Facts

- University Leadership

- History & Traditions

- Accreditation

- Consumer Information

- Our 10-Year Vision: The Gallaudet Promise

- Annual Report of Achievements (ARA)

- The Signing Ecosystem

- Not Your Average University

Our Community

- Library & Archives

- Technology Support

- Interpreting Requests

- Ombuds Support

- Health and Wellness Programs

- Profile & Web Edits

Visit Gallaudet

- Explore Our Campus

- Virtual Tour

- Maps & Directions

- Shuttle Bus Schedule

- Kellogg Conference Hotel

- Welcome Center

- National Deaf Life Museum

- Apple Guide Maps

Engage Today

- Work at Gallaudet / Clerc Center

- Social Media Channels

- University Wide Events

- Sponsorship Requests

- Data Requests

- Media Inquiries

- Gallaudet Today Magazine

- Giving at Gallaudet

- Financial Aid

- Registrar’s Office

- Residence Life & Housing

- Safety & Security

- Undergraduate Admissions

- Graduate Admissions

- University Communications

- Clerc Center

Gallaudet University, chartered in 1864, is a private university for deaf and hard of hearing students.

Copyright © 2024 Gallaudet University. All rights reserved.

- Accessibility

- Cookie Consent Notice

- Privacy Policy

- File a Report

800 Florida Avenue NE, Washington, D.C. 20002

Reference management. Clean and simple.

How to write an excellent thesis conclusion [with examples]

Restate the thesis

Review or reiterate key points of your work, explain why your work is relevant, a take-away for the reader, more resources on writing thesis conclusions, frequently asked questions about writing an excellent thesis conclusion, related articles.

At this point in your writing, you have most likely finished your introduction and the body of your thesis, dissertation, or research paper . While this is a reason to celebrate, you should not underestimate the importance of your conclusion. The conclusion is the last thing that your reader will see, so it should be memorable.

A good conclusion will review the key points of the thesis and explain to the reader why the information is relevant, applicable, or related to the world as a whole. Make sure to dedicate enough of your writing time to the conclusion and do not put it off until the very last minute.

This article provides an effective technique for writing a conclusion adapted from Erika Eby’s The College Student's Guide to Writing a Good Research Paper: 101 Easy Tips & Tricks to Make Your Work Stand Out .

While the thesis introduction starts out with broad statements about the topic, and then narrows it down to the thesis statement , a thesis conclusion does the same in the opposite order.

- Restate the thesis.

- Review or reiterate key points of your work.

- Explain why your work is relevant.

- Include a core take-away message for the reader.

Tip: Don’t just copy and paste your thesis into your conclusion. Restate it in different words.

The best way to start a conclusion is simply by restating the thesis statement. That does not mean just copying and pasting it from the introduction, but putting it into different words.

You will need to change the structure and wording of it to avoid sounding repetitive. Also, be firm in your conclusion just as you were in the introduction. Try to avoid sounding apologetic by using phrases like "This paper has tried to show..."

The conclusion should address all the same parts as the thesis while making it clear that the reader has reached the end. You are telling the reader that your research is finished and what your findings are.

I have argued throughout this work that the point of critical mass for biopolitical immunity occurred during the Romantic period because of that era's unique combination of post-revolutionary politics and innovations in smallpox prevention. In particular, I demonstrated that the French Revolution and the discovery of vaccination in the 1790s triggered a reconsideration of the relationship between bodies and the state.

Tip: Try to reiterate points from your introduction in your thesis conclusion.

The next step is to review the main points of the thesis as a whole. Look back at the body of of your project and make a note of the key ideas. You can reword these ideas the same way you reworded your thesis statement and then incorporate that into the conclusion.

You can also repeat striking quotations or statistics, but do not use more than two. As the conclusion represents your own closing thoughts on the topic , it should mainly consist of your own words.

In addition, conclusions can contain recommendations to the reader or relevant questions that further the thesis. You should ask yourself:

- What you would ideally like to see your readers do in reaction to your paper?

- Do you want them to take a certain action or investigate further?

- Is there a bigger issue that your paper wants to draw attention to?

Also, try to reference your introduction in your conclusion. You have already taken a first step by restating your thesis. Now, check whether there are other key words, phrases or ideas that are mentioned in your introduction that fit into your conclusion. Connecting the introduction to the conclusion in this way will help readers feel satisfied.

I explored how Mary Wollstonecraft, in both her fiction and political writings, envisions an ideal medico-political state, and how other writers like William Wordsworth and Mary Shelley increasingly imagined the body politic literally, as an incorporated political collective made up of bodies whose immunity to political and medical ills was essential to a healthy state.

Tip: Make sure to explain why your thesis is relevant to your field of research.

Although you can encourage readers to question their opinions and reflect on your topic, do not leave loose ends. You should provide a sense of resolution and make sure your conclusion wraps up your argument. Make sure you explain why your thesis is relevant to your field of research and how your research intervenes within, or substantially revises, existing scholarly debates.

This project challenged conventional ideas about the relationship among Romanticism, medicine, and politics by reading the unfolding of Romantic literature and biopolitical immunity as mutual, co-productive processes. In doing so, this thesis revises the ways in which biopolitics has been theorized by insisting on the inherent connections between Romantic literature and the forms of biopower that characterize early modernity.

Tip: If you began your thesis with an anecdote or historical example, you may want to return to that in your conclusion.

End your conclusion with something memorable, such as:

- a call to action

- a recommendation

- a gesture towards future research

- a brief explanation of how the problem or idea you covered remains relevant

Ultimately, you want readers to feel more informed, or ready to act, as they read your conclusion.

Yet, the Romantic period is only the beginning of modern thought on immunity and biopolitics. Victorian writers, doctors, and politicians upheld the Romantic idea that a "healthy state" was a literal condition that could be achieved by combining politics and medicine, but augmented that idea through legislation and widespread public health measures. While many nineteenth-century efforts to improve citizens' health were successful, the fight against disease ultimately changed course in the twentieth century as global immunological threats such as SARS occupied public consciousness. Indeed, as subsequent public health events make apparent, biopolitical immunity persists as a viable concept for thinking about the relationship between medicine and politics in modernity.

Need more advice? Read our 5 additional tips on how to write a good thesis conclusion.

The conclusion is the last thing that your reader will see, so it should be memorable. To write a great thesis conclusion you should:

The basic content of a conclusion is to review the main points from the paper. This part represents your own closing thoughts on the topic. It should mainly consist of the outcome of the research in your own words.

The length of the conclusion will depend on the length of the whole thesis. Usually, a conclusion should be around 5-7% of the overall word count.

End your conclusion with something memorable, such as a question, warning, or call to action. Depending on the topic, you can also end with a recommendation.

In Open Access: Theses and Dissertations you can find thousands of completed works. Take a look at any of the theses or dissertations for real-life examples of conclusions that were already approved.

Writing Resources

- Student Paper Template

- Grammar Guidelines

- Punctuation Guidelines

- Writing Guidelines

- Creating a Title

- Outlining and Annotating

- Using Generative AI (Chat GPT and others)

- Introduction, Thesis, and Conclusion

- Strategies for Citations

- Determining the Resource This link opens in a new window

- Citation Examples

- Paragraph Development

- Paraphrasing

- Inclusive Language

- International Center for Academic Integrity

- How to Synthesize and Analyze

- Synthesis and Analysis Practice

- Synthesis and Analysis Group Sessions

- Decoding the Assignment Prompt

- Annotated Bibliography

- Comparative Analysis

- Conducting an Interview

- Infographics

- Office Memo

- Policy Brief

- Poster Presentations

- PowerPoint Presentation

- White Paper

- Writing a Blog

- Research Writing: The 5 Step Approach

- Step 1: Seek Out Evidence

- Step 2: Explain

- Step 3: The Big Picture

- Step 4: Own It

- Step 5: Illustrate

- MLA Resources

- Time Management

ASC Chat Hours

ASC Chat is usually available at the following times ( Pacific Time):

If there is not a coach on duty, submit your question via one of the below methods:

928-440-1325

Ask a Coach

Search our FAQs on the Academic Success Center's Ask a Coach page.

Introduction, Thesis, and Conclusion: Writing Tips

- Introduction

Introductions should:

- Begin in an interesting way

- Start with a general idea about the topic and end with a specific statement about the focus of the paper (thesis statement). Use a funnel approach by starting broad and getting more narrow by the thesis.

- Have a thesis statement that begins with a claim or statement and exactly why you are writing about this claim or what you will be focusing about the claim (so what clause).

Introductions should not:

- Only be a sentence or two long. Introductions should be full paragraphs (5-6 sentences).

- Begin with the thesis statement. The thesis statement should be the last sentence (or two) of the introduction paragraph.

- Have wording like: “In this paper I will write about” or “I will focus on” be specific but do not spell out the obvious. (Remember to be interesting to the reader!)

Conclusions should:

- Begin in an interesting way that serves to begin to tie up the main points.

- Should have a summary of each main idea that the essay talks about.

- Show how these ideas relate to the thesis statement

- End in a way that comes full circle and ties up all loose ends

Conclusions should not:

- Begin with “In Conclusion”

- Introduce any new ideas

- End abruptly

- Leave the reader wondering how the main ideas relate to the thesis

- Only be a sentence or two long. Conclusions should be full paragraphs.

Writing Scholarly Introductions - Group Session

Monday 3:00 p.m.

The introduction to any type of writing is important as it sets the tone for the reader and builds their expectations for what is to come. Equally important is the conclusion since it is the last contact a writer has with the reader. Together, they form the bookends that encapsulate the argument made within the paper itself. In this interactive group session, you will learn how to create scholarly introductions and conclusions that will capture your reader’s interest and ensure that they leave knowing your intended points.

Key Resource: Thesis Writing Tips

Thesis Writing Tips

Some ways to help strengthen your thesis are as follows:

- Before you develop an argument on any topic, you have to collect and organize evidence, look for possible relationships between known facts (such as surprising contrasts or similarities), and think about the significance of these relationships. Once you do this thinking, you will probably have a "working thesis," a basic or main idea, an argument that you think you can support with evidence but that may need adjustment along the way.

- Do I answer the question? Re-reading the question prompt after constructing a working thesis can help you fix an argument that misses the focus of the question.

- Have I taken a position that others might challenge or oppose? If your thesis simply states facts that no one would, or even could, disagree with, it's possible that you are simply providing a summary, rather than making an argument

- Is my thesis statement specific enough? Thesis statements that are too vague often do not have a strong argument. If your thesis contains words like "good" or "successful," see if you could be more specific: why is something "good"; what specifically makes something "successful"? Does my thesis pass the "So what?" test? If a reader's first response is, "So what?" then you need to clarify, to forge a relationship, or to connect to a larger issue.

- Does my essay support my thesis specifically and without wandering? If your thesis and the body of your essay do not seem to go together, one of them has to change. It's o.k. to change your working thesis to reflect things you have figured out in the course of writing your paper. Remember, always reassess and revise your writing as necessary.

- Does my thesis pass the "how and why?" test? If a reader's first response is "how?" or "why?" your thesis may be too open-ended and lack guidance for the reader. See what you can add to give the reader a better take on your position right from the beginning.

- Remember: A strong thesis statement takes a stand, justifies discussion, expresses one main idea and is specific. Use the questions above to help make sure each of these components are present in your thesis.

Was this resource helpful?

- << Previous: Using Generative AI (Chat GPT and others)

- Next: Contextualizing Citations >>

- Last Updated: Apr 10, 2024 2:12 PM

- URL: https://resources.nu.edu/writingresources

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

9.4 Writing Introductory and Concluding Paragraphs

Learning objectives.

- Recognize the importance of strong introductory and concluding paragraphs.

- Learn to engage the reader immediately with the introductory paragraph.

- Practice concluding your essays in a more memorable way.

Picture your introduction as a storefront window: You have a certain amount of space to attract your customers (readers) to your goods (subject) and bring them inside your store (discussion). Once you have enticed them with something intriguing, you then point them in a specific direction and try to make the sale (convince them to accept your thesis).

Your introduction is an invitation to your readers to consider what you have to say and then to follow your train of thought as you expand upon your thesis statement.

An introduction serves the following purposes:

- Establishes your voice and tone, or your attitude, toward the subject

- Introduces the general topic of the essay

- States the thesis that will be supported in the body paragraphs

First impressions are crucial and can leave lasting effects in your reader’s mind, which is why the introduction is so important to your essay. If your introductory paragraph is dull or disjointed, your reader probably will not have much interest in continuing with the essay.

Attracting Interest in Your Introductory Paragraph

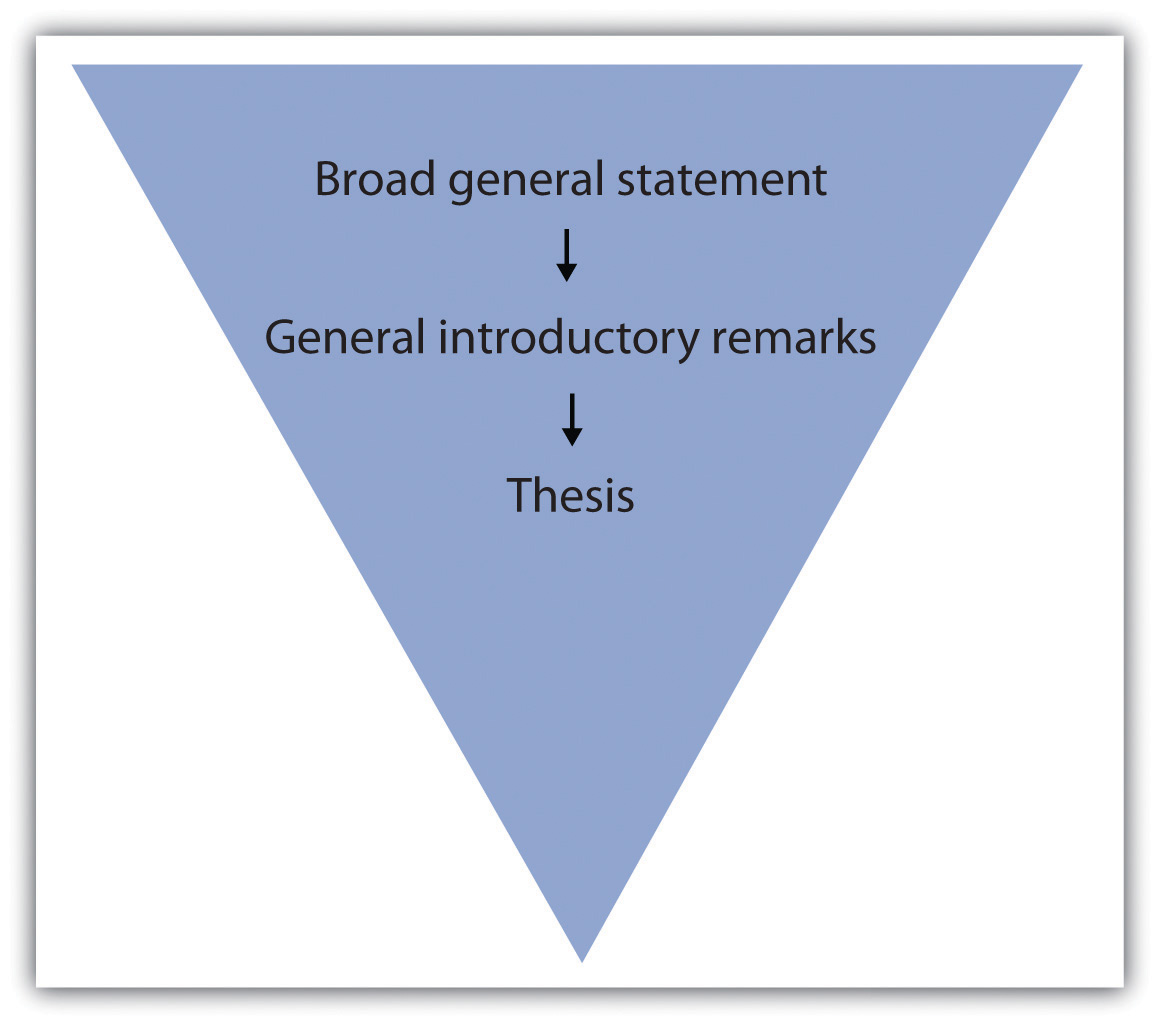

Your introduction should begin with an engaging statement devised to provoke your readers’ interest. In the next few sentences, introduce them to your topic by stating general facts or ideas about the subject. As you move deeper into your introduction, you gradually narrow the focus, moving closer to your thesis. Moving smoothly and logically from your introductory remarks to your thesis statement can be achieved using a funnel technique , as illustrated in the diagram in Figure 9.1 “Funnel Technique” .

Figure 9.1 Funnel Technique

On a separate sheet of paper, jot down a few general remarks that you can make about the topic for which you formed a thesis in Section 9.1 “Developing a Strong, Clear Thesis Statement” .

Immediately capturing your readers’ interest increases the chances of having them read what you are about to discuss. You can garner curiosity for your essay in a number of ways. Try to get your readers personally involved by doing any of the following:

- Appealing to their emotions

- Using logic

- Beginning with a provocative question or opinion

- Opening with a startling statistic or surprising fact

- Raising a question or series of questions

- Presenting an explanation or rationalization for your essay

- Opening with a relevant quotation or incident

- Opening with a striking image

- Including a personal anecdote

Remember that your diction, or word choice, while always important, is most crucial in your introductory paragraph. Boring diction could extinguish any desire a person might have to read through your discussion. Choose words that create images or express action. For more information on diction, see Chapter 4 “Working with Words: Which Word Is Right?” .

In Chapter 8 “The Writing Process: How Do I Begin?” , you followed Mariah as she moved through the writing process. In this chapter, Mariah writes her introduction and conclusion for the same essay. Mariah incorporates some of the introductory elements into her introductory paragraph, which she previously outlined in Chapter 8 “The Writing Process: How Do I Begin?” . Her thesis statement is underlined.

If you have trouble coming up with a provocative statement for your opening, it is a good idea to use a relevant, attention-grabbing quote about your topic. Use a search engine to find statements made by historical or significant figures about your subject.

Writing at Work

In your job field, you may be required to write a speech for an event, such as an awards banquet or a dedication ceremony. The introduction of a speech is similar to an essay because you have a limited amount of space to attract your audience’s attention. Using the same techniques, such as a provocative quote or an interesting statistic, is an effective way to engage your listeners. Using the funnel approach also introduces your audience to your topic and then presents your main idea in a logical manner.

Reread each sentence in Mariah’s introductory paragraph. Indicate which techniques she used and comment on how each sentence is designed to attract her readers’ interest.

Writing a Conclusion

It is not unusual to want to rush when you approach your conclusion, and even experienced writers may fade. But what good writers remember is that it is vital to put just as much attention into the conclusion as in the rest of the essay. After all, a hasty ending can undermine an otherwise strong essay.

A conclusion that does not correspond to the rest of your essay, has loose ends, or is unorganized can unsettle your readers and raise doubts about the entire essay. However, if you have worked hard to write the introduction and body, your conclusion can often be the most logical part to compose.

The Anatomy of a Strong Conclusion

Keep in mind that the ideas in your conclusion must conform to the rest of your essay. In order to tie these components together, restate your thesis at the beginning of your conclusion. This helps you assemble, in an orderly fashion, all the information you have explained in the body. Repeating your thesis reminds your readers of the major arguments you have been trying to prove and also indicates that your essay is drawing to a close. A strong conclusion also reviews your main points and emphasizes the importance of the topic.

The construction of the conclusion is similar to the introduction, in which you make general introductory statements and then present your thesis. The difference is that in the conclusion you first paraphrase , or state in different words, your thesis and then follow up with general concluding remarks. These sentences should progressively broaden the focus of your thesis and maneuver your readers out of the essay.

Many writers like to end their essays with a final emphatic statement. This strong closing statement will cause your readers to continue thinking about the implications of your essay; it will make your conclusion, and thus your essay, more memorable. Another powerful technique is to challenge your readers to make a change in either their thoughts or their actions. Challenging your readers to see the subject through new eyes is a powerful way to ease yourself and your readers out of the essay.

When closing your essay, do not expressly state that you are drawing to a close. Relying on statements such as in conclusion , it is clear that , as you can see , or in summation is unnecessary and can be considered trite.

It is wise to avoid doing any of the following in your conclusion:

- Introducing new material

- Contradicting your thesis

- Changing your thesis

- Using apologies or disclaimers

Introducing new material in your conclusion has an unsettling effect on your reader. When you raise new points, you make your reader want more information, which you could not possibly provide in the limited space of your final paragraph.

Contradicting or changing your thesis statement causes your readers to think that you do not actually have a conviction about your topic. After all, you have spent several paragraphs adhering to a singular point of view. When you change sides or open up your point of view in the conclusion, your reader becomes less inclined to believe your original argument.

By apologizing for your opinion or stating that you know it is tough to digest, you are in fact admitting that even you know what you have discussed is irrelevant or unconvincing. You do not want your readers to feel this way. Effective writers stand by their thesis statement and do not stray from it.

On a separate sheet of a paper, restate your thesis from Note 9.52 “Exercise 2” of this section and then make some general concluding remarks. Next, compose a final emphatic statement. Finally, incorporate what you have written into a strong conclusion paragraph for your essay.

Collaboration

Please share with a classmate and compare your answers

Mariah incorporates some of these pointers into her conclusion. She has paraphrased her thesis statement in the first sentence.

Make sure your essay is balanced by not having an excessively long or short introduction or conclusion. Check that they match each other in length as closely as possible, and try to mirror the formula you used in each. Parallelism strengthens the message of your essay.

On the job you will sometimes give oral presentations based on research you have conducted. A concluding statement to an oral report contains the same elements as a written conclusion. You should wrap up your presentation by restating the purpose of the presentation, reviewing its main points, and emphasizing the importance of the material you presented. A strong conclusion will leave a lasting impression on your audience.

Key Takeaways

- A strong opening captures your readers’ interest and introduces them to your topic before you present your thesis statement.

- An introduction should restate your thesis, review your main points, and emphasize the importance of the topic.

- The funnel technique to writing the introduction begins with generalities and gradually narrows your focus until you present your thesis.

- A good introduction engages people’s emotions or logic, questions or explains the subject, or provides a striking image or quotation.

- Carefully chosen diction in both the introduction and conclusion prevents any confusing or boring ideas.

- A conclusion that does not connect to the rest of the essay can diminish the effect of your paper.

- The conclusion should remain true to your thesis statement. It is best to avoid changing your tone or your main idea and avoid introducing any new material.

- Closing with a final emphatic statement provides closure for your readers and makes your essay more memorable.

Writing for Success Copyright © 2015 by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

- Twin Cities

- Campus Today

- Directories

University of Minnesota Crookston

- Presidential Search

- Mission, Vision & Values

- Campus Directory

- Campus Maps/Directions

- Transportation and Lodging

- Crookston Community

- Chancellor's Office

- Quick Facts

- Tuition & Costs

- Institutional Effectiveness

- Organizational Chart

- Accreditation

- Strategic Planning

- Awards and Recognition

- Policies & Procedures

- Campus Reporting

- Public Safety

- Admissions Home

- First Year Student

- Transfer Student

- Online Student

- International Student

- Military Veteran Student

- PSEO Student

- More Student Types...

- Financial Aid

- Net Price Calculator

- Cost of Attendance

- Request Info

- Visit Campus

- Admitted Students

- Majors, Minors & Programs

- Agriculture and Natural Resources

- Humanities, Social Sciences, and Education

- Math, Science and Technology

- Teacher Education Unit

- Class Schedules & Registration

- Academic Calendar

- Clubs & Organizations

- Events Calendar

- Student Activities

- Outdoor Equipment Rental

- Intramural & Club Sports

- Wellness Center

- Golden Eagle Athletics

- Health Services

- Career Services

- Counseling Services

- Success Center/Tutoring

- Computer Help Desk

- Scholarships & Aid

- Eagle's Essentials Pantry

- Transportation

- Dining Options

- Residential Life

- Safety & Security

- Crookston & NW Minnesota

- Important Dates & Deadlines

- Teambackers

- Campus News

- Student Dates & Deadlines

- Social Media

- Publications & Archives

- Summer Camps

- Alumni/Donor Awards

- Alumni and Donor Relations

Writing Center

Effective introductions and thesis statements, make them want to continue reading.

Writing an effective introduction is an art form. The introduction is the first thing that your reader sees. It is what invests the reader in your paper, and it should make them want to continue reading. You want to be creative and unique early on in your introduction; here are some strategies to help catch your reader’s attention:

- Tell a brief anecdote or story

- As a series of short rhetorical questions

- Use a powerful quotation

- Refute a common belief

- Cite a dramatic fact or statistic

Your introduction also needs to adequately explain the topic and organization of your paper.

Your thesis statement identifies the purpose of your paper. It also helps focus the reader on your central point. An effective thesis establishes a tone and a point of view for a given purpose and audience. Here are some important things to consider when constructing your thesis statement.

- Don’t just make a factual statement – your thesis is your educated opinion on a topic.

- Don’t write a highly opinionated statement that might offend your audience.

- Don’t simply make an announcement (ex. “Tuition should be lowered” is a much better thesis than “My essay will discuss if tuition should be lowered”).

- Don’t write a thesis that is too broad – be specific.

The thesis is often located in the middle or at the end of the introduction, but considerations about audience, purpose, and tone should always guide your decision about its placement.

Sometimes it’s helpful to wait to write the introduction until after you’ve written the essay’s body because, again, you want this to be one of the strongest parts of the paper.

Example of an introduction:

Innocent people murdered because of the hysteria of young girls! Many people believe that the young girls who accused citizens of Salem, Massachusetts of taking part in witchcraft were simply acting to punish their enemies. But recent evidence shows that the young girls may have been poisoned by a fungus called Ergot, which affects rye and wheat. The general public needs to learn about this possible cause for the hysteria that occurred in Salem so that society can better understand what happened in the past, how this event may change present opinion, and how the future might be changed by learning this new information.

By Rachel McCoppin, Ph.D. Last edited October 2016 by Allison Haas, M.A.

21 Writing an Introduction and Conclusion

The introduction and conclusion are the strong walls that hold up the ends of your essay. The introduction should pique the readers’ interest, articulate the aim or purpose of the essay, and provide an outline of how the essay is organised. The conclusion mirrors the introduction in structure and summarizes the main aim and key ideas within the essay, drawing to a logical conclusion. The introduction states what the essay will do and the conclusion tells the reader what the essay has achieved .

Introduction

The primary functions of the introduction are to introduce the topic and aim of the essay, plus provide the reader with a clear framework of how the essay will be structured. Therefore, the following sections provide a brief overview of how these goals can be achieved. The introduction has three basic sections (often in one paragraph if the essay is short) that establish the key elements: background, thesis statement, and essay outline.

The background should arrest the readers’ attention and create an interest in the chosen topic. Therefore, backgrounding on the topic should be factual, interesting, and may use supporting evidence from academic sources . Shorter essays (under 1000 words) may only require 1-3 sentences for backgrounding, so make the information specific and relevant, clear and succinct . Longer essays may call for a separate backgrounding paragraph. Always check with your lecturer/tutor for guidelines on your specific assignment.

Thesis Statement

The thesis statement is a theory, put forward as a position to be maintained or proven by the writing that follows in the essay. It focuses the writer’s ideas within the essay and all insights, arguments and viewpoints centre around this statement. The writer should refer back to it both mentally and literally throughout the writing process, plus the reader should see the key concepts within the thesis unfolding throughout the written work. A separate section about developing the thesis statement has been included below.

Essay Outline Sentence/s

The essay outline is 1-2 sentences that articulate the focus of the essay in stages. They clearly explain how the thesis statement will be addressed in a sequential manner throughout the essay paragraphs. The essay outline should also leave no doubt in the readers’ minds about what is NOT going to be addressed in your essay. You are establishing the parameters, boundaries, or limitations of the essay that follows. Do not, however, use diminishing language such as, “this brief essay will only discuss…”, “this essay hopes to prove/will attempt to show…”. This weakens your position from the outset. Use strong signposting language, such as “This essay will discuss… (paragraph 1) then… (paragraph 2) before moving on to… (paragraph 3) followed by the conclusion and recommendations”. This way the reader knows from the outset how the essay will be structured and it also helps you to better plan your body paragraphs (see Chapter 22).

Brief Example

(Background statement) Nuclear power plants are widely used throughout the world as a clean, efficient source of energy. (Thesis with a single idea) It has been proven that thermonuclear energy (topic) is a clean, safe alternative to burning fossil fuels. (Essay outline sentence) This essay will discuss the environmental, economic, social impacts of having a thermonuclear power plant providing clean energy to a major city.

- Background statement

- Thesis statement – claim

- Essay outline sentence (with three controlling ideas )

Regardless of the length of the essay, it should always have a thesis statement that clearly articulates the key aim or argument/s in the essay. It focuses both the readers’ attention and the essay’s purpose. In a purely informative or descriptive essay, the thesis may contain a single, clear claim. Whereas, in a more complex analytical, persuasive, or critical essay (see Chapter 15) there may be more than one claim, or a claim and counter-claim (rebuttal) within the thesis statement (see Chapter 25 – Academic Writing [glossary]). It is important to remember that the majority of academic writing is not only delivering information, it is arguing a position and supporting claims with facts and reliable examples. A strong thesis will be original, specific and arguable. This means it should never be a statement of the obvious or a vague reference to general understandings on a topic.

Weak Thesis Examples

The following examples are too vague and leave too many questions unanswered because they are not specific enough.

“Reading is beneficial” – What type of reading? Reading at what level/age? Reading for what time period? Reading what types of text? How is it beneficial, to who?

“Dogs are better than cats” – Better in what way? What types of dogs in what environment? Domesticated or wild animals? What are the benefits of being a dog owner? Is this about owning a dog or just dogs as a breed?

“Carbon emissions are ruining our planet” – Carbon emissions from where/what? In what specific way is our planet suffering? What is the timeframe of this problem?

A strong thesis should stand up to scrutiny. It should be able to answer the “So what?” question. Why should the reader want to continue reading your essay? What are you going to describe, argue, contest that will fix their attention? If no-one can or would argue with your thesis, then it is too weak, too obvious.

Your thesis statement is your answer to the essay question.

A strong thesis treats the topic of an essay in-depth. It will make an original claim that is both interesting and supportable, plus able to be refuted. In a critical essay this will allow you to argue more than one point of view (see Chapter 27 – Writing a Discursive Essay ). Again, this is why it is important that you complete sufficient background reading and research on your topic to write from an informed position.

Strong Thesis Examples

“Parents reading to their children, from age 1-5 years, enhance their children’s vocabulary, their interest in books, and their curiosity about the world around them.”

“Small, domesticated dogs make better companions than domesticated cats because of their loyal and intuitive nature.”

“Carbon emissions from food production and processing are ruining Earth’s atmosphere.”

As demonstrated, by adding a specific focus, and key claim, the above thesis statements are made stronger.

Beginner and intermediate writers may prefer to use a less complex and sequential thesis like those above. They are clear, supportable and arguable. This is all that is required for the Term one and two writing tasks.

Once you become a more proficient writer and advance into essays that are more analytical and critical in nature, you will begin to incorporate more than one perspective in the thesis statement. Again, each additional perspective should be arguable and able to be supported with clear evidence. A thesis for a discursive essay (Term Three) should contain both a claim AND counter-claim , demonstrating your capacity as a writer to develop more than one perspective on a topic.

A Note on Claims and Counter-claims

Demonstrating that there is more than one side to an argument does not weaken your overall position on a topic. It indicates that you have used your analytical thinking skills to identify more than one perspective, potentially including opposing arguments. In your essay you may progress in such a way that refutes or supports the claim and counter-claim.

Please do not confuse the words ‘claim’ and ‘counter-claim’ with moral or value judgements about right/wrong, good/bad, successful/unsuccessful, or the like. The term ‘claim’ simply refers to the first position or argument you put forward, and ‘counter-claim’ is the alternate position or argument.

Discursive Essay Thesis – Examples adapted from previous students

“ Although it is argued that renewable energy may not meet the energy needs of Australia, there is research to indicate the benefits of transitioning to more environmentally favourable energy sources now.”

“It is argued that multiculturalism is beneficial for Australian society, economy and culture, however some members of society have a negative view of multiculturalism‘s effects on the country.”

“The widespread adoption of new technologies is inevitable and may benefit society, however , these new technologies could raise ethical issues and therefore might be of detriment .”

Note the use of conjunctive terms (underlined) to indicate alternative perspectives.

In term three you will be given further instruction in developing a thesis statement for a discursive essay in class time.

The conclusion is the final paragraph of the essay and it summarizes and synthesizes the topic and key ideas, including the thesis statement. As such, no new information or citations should be present in the conclusion. It should be written with an authoritative , formal tone as you have taken the time to support all the claims (and counter-claims) in your essay. It should follow the same logical progression as the key points in your essay and reach a clear and well-written conclusion – the statement within the concluding paragraph that makes it very clear you have answered the essay question. Read the marking criteria of your assignment to determine whether you are also required to include a recommendation or prediction as part of the conclusion. If so, make recommendations relevant to the context and content of the essay. They should be creative, specific and realistic. If you are making a prediction, focus on how the information or key arguments used in the essay might impact the world around you, or the field of inquiry, in a realistic way.

A strong, well-written conclusion should draw all of the threads of the essay together and show how they relate to each other and also how they make sense in relation to the essay question and thesis.

make clear, distinct, and precise in relation to other parts

Synonyms: catch and hold; attract and fix; engage

researched, reliable, written by academics and published by reputable publishers; often, but not always peer reviewed

concise expressed in few words

assertion, maintain as fact

a claim made to rebut a previous claim

attract and hold

used to link words or phrases together See 'Language Basics'

able to be trusted as being accurate or true; reliable

decision reached by sound and valid reasoning

Academic Writing Skills Copyright © 2021 by Patricia Williamson is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

6.8: Writing introductions, conclusions, and titles- A key to organizing

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 75199

- Alexandra Glynn, Kelli Hallsten-Erickson & Amy Jo Swing

- North Hennepin Community College & Lake Superior College

Orienting the reader: Writing an introduction

A long time ago, in a galaxy far, far away…

Does this ring a bell? These are the opening words to every episode in the massive, culture-bending Star Wars franchise.

They shoot the white girl first, but the rest they can take their time.

Sit with that one for a minute. Shocking? Yes. Compelling? Yes. Does it make you want to know what’s going on? Absolutely. You might not recognize this as the first line from Toni Morrison’s novel Paradise , but it is a good first line. It not only sets a scene showing violence and a group of people (probably men) on a murder spree, killing another group of people (at least one white woman; the rest are not white, and we can guess that they’re probably women, too), but it also pulls out any number of emotional reactions. That is an incredible first line.

Now, these examples are pretty extreme. The first is from one of the most popular, if not THE most popular, series of films in American history, and the second is from the seventh novel by one of the greatest American authors alive today. Your introductions don’t need to be as earth-shattering, but they do need to do three things:

- Grab the reader's attention

- Give a sense of the direction of ideas in the essay

- Set up what the writing will be like in the essay (super formal, more informal, etc.)

No big deal, right? Actually, it can feel like a HUGE deal, and writing the introduction can be so scary for some writers that it stops any forward progress. So, here are the first two rules for writing introductions:

Two rules for writing introductions

Rule Number One: If you don’t have ideas for the introduction, skip it!

No, don’t skip it altogether—you need to have one!—but if it’s freaking you out and stopping you from getting going on your essay, start working with your body paragraphs first. Sometimes you need to play with the essay ideas for a while before an idea for the introduction alights on your shoulder and demands your attention.

Of course, sometimes ideas aren’t that cooperative and you need to work at pulling them out. Have you written the rest of the essay and now you are considering the virtues of skipping writing an introduction altogether rather than going through the torture of having to figure it out? First, relax. Don’t take it so seriously.

Rule Number Two: Consider audience!

This brings us to the second rule about introductions. Ask yourself: What will get my audience’s attention? Always consider the audience’s needs, interests and desires. If your audience is similar to you in any way, fabulous. Ask yourself: What would get my attention? Write an introduction that amuses or fascinates you. After all, if you’re genuinely delighted, that could rub off on the reader.

Types of introductions: Thesis statement, anecdote, asking questions, a contradiction, and starting in the middle

It might help if you had some ideas about the types of introductions out there:

- Thesis statement

- Asking questions

- A contraction

- Starting in the middle

Thesis statement introductions are for the traditionalists. They also often work well in professional writing. They are typical in formal essays where it’s important to start broad to help create context for a topic before narrowing it in to land at the specific point of the essay, in the thesis statement, at the end of the introductory paragraph. Sometimes formal academic argument papers even start with the thesis statement, as in this example:

Parents are heroes because they work hard to show their children the difference between right and wrong, they teach their children compassion, and they help them to grow into stable, loving adults. Parents act as guides for their kids while allowing them to make mistakes, listening to them when their kids need to talk, pushing them along when they’re too shy to move on their own, and cheering the loudest when their kids achieve their dreams. It’s no easy task to be the steady, moral compass that kids need, as parents are people too, and people make mistakes. As a species, though, we manage more often than not to raise well-adjusted kids who turn into hardworking adults, giving us hope for the future.

As you can see, it’s a pretty general and generic introduction, but it firmly orients the reader into the topic.

Let’s say you want to stretch your creativity a bit, though. You might try an anecdotal introduction , where you tell a brief but complete story (real or fictional). This is using narration to catch the reader’s attention. Here’s an example of that using the same topic and thesis statement as above:

When my brother was little, he used to get into all sorts of trouble. Because he was just so curious about everything, his desire to check things out often overrode his good sense. This finally got the best of him when he was nine and got stuck in a tree. He climbed up there to look into a bird’s nest, and we found him after he started yelling for us. He was twenty feet up there, and before my mom and I knew what was happening, my dad jumped up and started climbing, which was amazing because my father isn’t too fond of heights. He got up to Jason and then helped him down, showing him where to put his hands and feet. When they were both safely on the ground, my parents scolded Jason while simultaneously hugging him. He was still terrified, and suddenly, I could see how terrified my dad was, too. I never forgot that moment, and I also came to a realization. Parents aren’t just heroes because they will put their lives on the line for their kids. Parents are heroes because they work hard to show their children the difference between right and wrong, they teach their children compassion, and they help them to grow into stable, loving adults.

This is a great strategy to try because it gives a specific example of your topic, and it’s human nature to enjoy hearing stories. The reader won’t be able to help being pulled into your essay when you use narration.

Another strategy writers employ when writing introductions is asking a question or questions to catch the reader’s attention. You might have heard the adage, “There are no dumb questions, only dumb answers.” While that’s often true, when it comes to introductions, you need to be smart about the types of questions you ask, always keeping your audience in mind:

- DON'T ask yes or no questions

- DON’T ask questions that will cause the reader to tune out.

- DO ask questions that get the reader thinking in the direction you’re planning on going in within your essay.

Here’s an example of a question that will stop your reader in his or her tracks:

Have you ever wondered about how Einstein’s String Theory applies to old growth forests?

Why is this a bad question? Simple: what if the reader answers that and says “Uh…no.” You’ve just lost the reader.

Instead, consider your audience: what questions might they actually have about your topic? For example:

When you were a kid, who were your heroes? Was it Luke Skywalker? The President of the United States? An astronaut? A firefighter? Heroes come from all walks of life…

This series of questions begins with an open-ended question that frames the topic (childhood heroes) and gets readers thinking, but not too much—the follow-up questions keep readers from floating off into la-la land with their own ideas.

Another strategy that can work well is considering the contradictions in your topic, playing Devil's Advocate, and bringing them up right away in the introduction. When it comes to your topic, what clichés are out there about it? What misunderstandings do people have? Those ideas can make for a great introduction. For example:

When kids think about heroes, they often think about Superman or Spiderman in all of their comic book glory. These superheroes fight the bad guys, restoring order in the chaos that the villains create in the comics. They always win in the end because they are the good ones and because they have amazing abilities. What kid hasn’t thought about how cool it would be to have super powers? What kids often miss, however, and don’t understand until they’re older, is that their parents are the real superheroes in their lives. The super powers that parents have may not be bionic vision or super strength, but they have powers that are much more important. Parents are heroes because they work hard to show their children the difference between right and wrong, they teach their children compassion, and they help them to grow into stable, loving adults.

Note that in this sample, there’s a contradiction: the cliché idea of heroes as cartoon superheroes, but there’s also a rhetorical question. Often, strategies for writing introductions can be combined to great effect.

Finally, an introductory strategy worth noting is similar to an anecdote, but instead of starting at the beginning of a story, you start in the middle of the action. For example, instead of setting the scene by starting in the cafeteria on a normal school day, you would start like this:

A wad of spaghetti smacked the side of my face, and one of the noodles ricocheted off my cheek and swung into my mouth. I nearly inhaled it, but before I started choking, I managed to fling a handful of fries in Jose’s direction. I saw Amy running over to dump her milkshake on Anthony’s head before I ducked under the table. It was full-on pandemonium in the cafeteria, boys versus girls, a spark of rage finally igniting after weeks of classroom tension.

Starting an essay right in the middle of action immediately piques the reader’s interest and creates a tension that can, admittedly, be difficult to come down from, but it sure makes for an exciting start.

These strategies can serve to enliven your essay topic, not just for the reader, but for you. When you can build an introduction that you can be proud of, it can give you creative ideas for the rest of your piece. Consider trying several different strategies for your introduction and choose what works best. Perhaps even combine a few to customize. It’s also worth noting that, though introductions are traditionally one paragraph with the thesis statement as the last sentence, there’s nothing saying an introduction can’t be more than one paragraph. It’s all about what’s going to work for your topic and for your audience.

Making your mark: Writing a conclusion

Let’s be honest. When you’ve spent so much time working out the ideas of your essay, organizing them, and writing an awesome, eye-catching introduction, by the time you get to the conclusion, you might have run out of steam. It can feel impossible to maintain the creative momentum through the most boring of paragraphs: the conclusion. So what do writers do? Easy: they start by writing, “In conclusion…” and sum up what the reader just got done reading.

If that feels off to you, good. It should. Unless you’ve written a long essay, a summary-style conclusion isn’t appropriate and can even be insulting to the reader: why would you think readers need to be reminded of what they just read? Have more faith in them and in your own writing. If you’ve done your job in the essay, your ideas will be etched in readers’ brains.

You still need to have a conclusion, though. So what’s a conscientious writer to do?

The goal of a conclusion is to leave the reader with the final impression of your take on the topic. You don’t need to try to have the final, be-all, end-all word on the topic, case closed, no more discussion. Readers will reject this. And again, don’t worry about summarizing what you’ve just written.

Think about a boring conclusion being like the end of a class period. Your classmates are putting their books away, packing their bags, glancing at their phones—their minds are already floating away from the topics in the class. An effective teacher will keep student attention until she is ready to dismiss the class, and an effective conclusion will not just keep the reader's attention until the end but will make them want to go back to the beginning and re-read—to see what they might have missed.

Types of conclusions: Mirroring the introduction, predicting the future, humor

The easiest way to write a conclusion, especially after you’ve written a stellar introduction, is to mirror the introduction. So, if you’ve started by setting the scene in the cafeteria mid-food fight, go back to the cafeteria in the conclusion, perhaps just as the fight is over and it’s dawned on all the kids that this was a bad idea. If you spent your introduction bringing up a contradiction and dispelling it, allude to that contradiction again in your conclusion. If you asked a question in the introduction, you’d better be sure to answer it in the conclusion.

Mirroring is the easiest way of thinking about an appropriate concluding strategy. You might also consider looking into the crystal ball and predicting the future. Let’s say you’re arguing for increased sales taxes to help improve your city’s crumbling roads in your essay. In your conclusion, paint a picture of what the future roads would look like (or feel like when driving on them!) if you got your way. This idyllic, concrete scene would remain in readers’ minds, increasing the chances that they’ll remember your point of view.

Another option that helps to endear you one more time to the reader is ending with something funny or catchy. When readers feel good because you utilized the strategy of a humorous conclusion , they’ll remember that feeling and your take on the topic. You don’t need to be a comedian to be funny, either. You can utilize jokes made in popular culture to make your reader smile: from the classic “Where’s the beef?” catchphrase the fast-food chain Wendy’s utilized in the 80’s to the more current “double rainbow” YouTube video to the most cutting-edge memes, these jokes can be utilized for an impactful conclusion. The key, however (and warning!), is to consider your audience . Choose something that will amuse your audience, because although you don’t need to be a comedian to write a humorous conclusion, like a comedian, if the joke falls flat, you’ll leave readers with crickets chirping and awkward silence that all comedians face one time or another.

Another great option is one encouraged by the ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle in his books on Rhetoric: use a maxim, or proverb. These are like folk-wisdom, or quotes by famous people who really know how to turn a phrase.

For example, in writing a paper arguing about nursery rhymes and the gender roles in them, you could end by quoting a portion of the ending nursery rhyme:

Snip, snap, snout,

This tale’s told out.

Of course, this strategy could fail, too, by hitting the wrong note or not being quite on-topic. This is where an extra pair of eyes (or two or three) helps: test your conclusion out on others before you call it your final draft.

Name the game: Writing a gripping title

Some people have no problem coming up with titles for their essays. The struggle is NOT real for them, and they don’t understand why the rest of us have difficulties with this relatively small part of the essay, at least small words-wise. These same people should probably go out and play the lottery because they’re lucky. For the rest of us, however, we need to work at it.

Titles are scary because they’re short, yet they must do a lot of work: they state the topic, a direction for the topic, and grab attention. You might note that these are basically the same tasks of the introduction, but at least with that, you have a whole paragraph. Not so with a title (unless you’re going for something absurd, which your supervisor or writing teacher will likely not appreciate).

Yes, writing a title requires some creativity. In this case, though, there’s a strategy you can use to think about title creation.

Step One: Write down your topic

Hank Aaron, baseball legend

Step Two: Think about the points you’re going to make in the essay about your topic

This is a major research paper, so it’s long. I’m going to write about his baseball life, his early life, and his passions outside of baseball (civil rights)

Step Three: Brainstorm a list of ideas, clichés, and associations dealing with your topic

Baseball, take me out to the ball game, grand slam, double-header, triple play, seventh-inning stretch, peanuts and Cracker Jack, “Juuuust a bit outside,” major league, home run, homers, crack of the bat, Negro League, Milwaukee Brewers, The Hammer (his nickname), swing and miss…

Step Four: Put the ideas together in interesting ways to create title options

Hank Aaron Hammers It Home

Triple Play: The Life, Love, and Career of Hank Aaron

From Mobile to the Majors: Hank Aaron’s Success Story

…and so on.

Note that the second two title options above utilize a colon. These are titles with subtitles, sometimes called a two-part title. The first part, before the colon, is the eye-catcher. The second part gives a direction for the essay. This is an opportunity you can exercise to get more words for your title. Note that each section of this chapter utilizes a title and subtitle! It’s a great strategy to try.

Let's say you're going to write a persuasive essay about the importance of attending class. You can think of different titles based on different strategies:

- For Example: How to be a Successful College Student

- To Attend or Not to Attend?

- Go to Class!

- Attendance: The Key to Acing College

- Be There: Attending Class to Ace College

How to write a fantastic thesis introduction (+15 examples)

The thesis introduction, usually chapter 1, is one of the most important chapters of a thesis. It sets the scene. It previews key arguments and findings. And it helps the reader to understand the structure of the thesis. In short, a lot is riding on this first chapter. With the following tips, you can write a powerful thesis introduction.

Disclosure: This post may contain affiliate links, which means I may earn a small commission if you make a purchase using the links below at no additional cost to you . I only recommend products or services that I truly believe can benefit my audience. As always, my opinions are my own.

Elements of a fantastic thesis introduction

Open with a (personal) story, begin with a problem, define a clear research gap, describe the scientific relevance of the thesis, describe the societal relevance of the thesis, write down the thesis’ core claim in 1-2 sentences, support your argument with sufficient evidence, consider possible objections, address the empirical research context, give a taste of the thesis’ empirical analysis, hint at the practical implications of the research, provide a reading guide, briefly summarise all chapters to come, design a figure illustrating the thesis structure.

An introductory chapter plays an integral part in every thesis. The first chapter has to include quite a lot of information to contextualise the research. At the same time, a good thesis introduction is not too long, but clear and to the point.

A powerful thesis introduction does the following:

- It captures the reader’s attention.

- It presents a clear research gap and emphasises the thesis’ relevance.

- It provides a compelling argument.

- It previews the research findings.

- It explains the structure of the thesis.

In addition, a powerful thesis introduction is well-written, logically structured, and free of grammar and spelling errors. Reputable thesis editors can elevate the quality of your introduction to the next level. If you are in search of a trustworthy thesis or dissertation editor who upholds high-quality standards and offers efficient turnaround times, I recommend the professional thesis and dissertation editing service provided by Editage .

This list can feel quite overwhelming. However, with some easy tips and tricks, you can accomplish all these goals in your thesis introduction. (And if you struggle with finding the right wording, have a look at academic key phrases for introductions .)

Ways to capture the reader’s attention

A powerful thesis introduction should spark the reader’s interest on the first pages. A reader should be enticed to continue reading! There are three common ways to capture the reader’s attention.

An established way to capture the reader’s attention in a thesis introduction is by starting with a story. Regardless of how abstract and ‘scientific’ the actual thesis content is, it can be useful to ease the reader into the topic with a short story.

This story can be, for instance, based on one of your study participants. It can also be a very personal account of one of your own experiences, which drew you to study the thesis topic in the first place.

Start by providing data or statistics

Data and statistics are another established way to immediately draw in your reader. Especially surprising or shocking numbers can highlight the importance of a thesis topic in the first few sentences!

So if your thesis topic lends itself to being kick-started with data or statistics, you are in for a quick and easy way to write a memorable thesis introduction.

The third established way to capture the reader’s attention is by starting with the problem that underlies your thesis. It is advisable to keep the problem simple. A few sentences at the start of the chapter should suffice.

Usually, at a later stage in the introductory chapter, it is common to go more in-depth, describing the research problem (and its scientific and societal relevance) in more detail.

You may also like: Minimalist writing for a better thesis

Emphasising the thesis’ relevance

A good thesis is a relevant thesis. No one wants to read about a concept that has already been explored hundreds of times, or that no one cares about.

Of course, a thesis heavily relies on the work of other scholars. However, each thesis is – and should be – unique. If you want to write a fantastic thesis introduction, your job is to point out this uniqueness!

In academic research, a research gap signifies a research area or research question that has not been explored yet, that has been insufficiently explored, or whose insights and findings are outdated.

Every thesis needs a crystal-clear research gap. Spell it out instead of letting your reader figure out why your thesis is relevant.

* This example has been taken from an actual academic paper on toxic behaviour in online games: Liu, J. and Agur, C. (2022). “After All, They Don’t Know Me” Exploring the Psychological Mechanisms of Toxic Behavior in Online Games. Games and Culture 1–24, DOI: 10.1177/15554120221115397

The scientific relevance of a thesis highlights the importance of your work in terms of advancing theoretical insights on a topic. You can think of this part as your contribution to the (international) academic literature.

Scientific relevance comes in different forms. For instance, you can critically assess a prominent theory explaining a specific phenomenon. Maybe something is missing? Or you can develop a novel framework that combines different frameworks used by other scholars. Or you can draw attention to the context-specific nature of a phenomenon that is discussed in the international literature.

The societal relevance of a thesis highlights the importance of your research in more practical terms. You can think of this part as your contribution beyond theoretical insights and academic publications.

Why are your insights useful? Who can benefit from your insights? How can your insights improve existing practices?

Formulating a compelling argument

Arguments are sets of reasons supporting an idea, which – in academia – often integrate theoretical and empirical insights. Think of an argument as an umbrella statement, or core claim. It should be no longer than one or two sentences.

Including an argument in the introduction of your thesis may seem counterintuitive. After all, the reader will be introduced to your core claim before reading all the chapters of your thesis that led you to this claim in the first place.

But rest assured: A clear argument at the start of your thesis introduction is a sign of a good thesis. It works like a movie teaser to generate interest. And it helps the reader to follow your subsequent line of argumentation.

The core claim of your thesis should be accompanied by sufficient evidence. This does not mean that you have to write 10 pages about your results at this point.

However, you do need to show the reader that your claim is credible and legitimate because of the work you have done.

A good argument already anticipates possible objections. Not everyone will agree with your core claim. Therefore, it is smart to think ahead. What criticism can you expect?

Think about reasons or opposing positions that people can come up with to disagree with your claim. Then, try to address them head-on.

Providing a captivating preview of findings

Similar to presenting a compelling argument, a fantastic thesis introduction also previews some of the findings. When reading an introduction, the reader wants to learn a bit more about the research context. Furthermore, a reader should get a taste of the type of analysis that will be conducted. And lastly, a hint at the practical implications of the findings encourages the reader to read until the end.

If you focus on a specific empirical context, make sure to provide some information about it. The empirical context could be, for instance, a country, an island, a school or city. Make sure the reader understands why you chose this context for your research, and why it fits to your research objective.

If you did all your research in a lab, this section is obviously irrelevant. However, in that case you should explain the setup of your experiment, etcetera.

The empirical part of your thesis centers around the collection and analysis of information. What information, and what evidence, did you generate? And what are some of the key findings?

For instance, you can provide a short summary of the different research methods that you used to collect data. Followed by a short overview of how you analysed this data, and some of the key findings. The reader needs to understand why your empirical analysis is worth reading.

You already highlighted the practical relevance of your thesis in the introductory chapter. However, you should also provide a preview of some of the practical implications that you will develop in your thesis based on your findings.

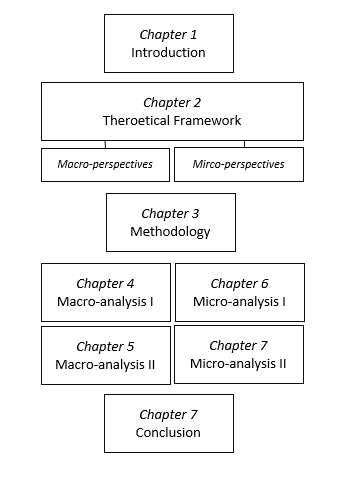

Presenting a crystal clear thesis structure