- USC Libraries

- Research Guides

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper

- Types of Research Designs

- Purpose of Guide

- Design Flaws to Avoid

- Independent and Dependent Variables

- Glossary of Research Terms

- Reading Research Effectively

- Narrowing a Topic Idea

- Broadening a Topic Idea

- Extending the Timeliness of a Topic Idea

- Academic Writing Style

- Applying Critical Thinking

- Choosing a Title

- Making an Outline

- Paragraph Development

- Research Process Video Series

- Executive Summary

- The C.A.R.S. Model

- Background Information

- The Research Problem/Question

- Theoretical Framework

- Citation Tracking

- Content Alert Services

- Evaluating Sources

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

- Tiertiary Sources

- Scholarly vs. Popular Publications

- Qualitative Methods

- Quantitative Methods

- Insiderness

- Using Non-Textual Elements

- Limitations of the Study

- Common Grammar Mistakes

- Writing Concisely

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Footnotes or Endnotes?

- Further Readings

- Generative AI and Writing

- USC Libraries Tutorials and Other Guides

- Bibliography

Introduction

Before beginning your paper, you need to decide how you plan to design the study .

The research design refers to the overall strategy and analytical approach that you have chosen in order to integrate, in a coherent and logical way, the different components of the study, thus ensuring that the research problem will be thoroughly investigated. It constitutes the blueprint for the collection, measurement, and interpretation of information and data. Note that the research problem determines the type of design you choose, not the other way around!

De Vaus, D. A. Research Design in Social Research . London: SAGE, 2001; Trochim, William M.K. Research Methods Knowledge Base. 2006.

General Structure and Writing Style

The function of a research design is to ensure that the evidence obtained enables you to effectively address the research problem logically and as unambiguously as possible . In social sciences research, obtaining information relevant to the research problem generally entails specifying the type of evidence needed to test the underlying assumptions of a theory, to evaluate a program, or to accurately describe and assess meaning related to an observable phenomenon.

With this in mind, a common mistake made by researchers is that they begin their investigations before they have thought critically about what information is required to address the research problem. Without attending to these design issues beforehand, the overall research problem will not be adequately addressed and any conclusions drawn will run the risk of being weak and unconvincing. As a consequence, the overall validity of the study will be undermined.

The length and complexity of describing the research design in your paper can vary considerably, but any well-developed description will achieve the following :

- Identify the research problem clearly and justify its selection, particularly in relation to any valid alternative designs that could have been used,

- Review and synthesize previously published literature associated with the research problem,

- Clearly and explicitly specify hypotheses [i.e., research questions] central to the problem,

- Effectively describe the information and/or data which will be necessary for an adequate testing of the hypotheses and explain how such information and/or data will be obtained, and

- Describe the methods of analysis to be applied to the data in determining whether or not the hypotheses are true or false.

The research design is usually incorporated into the introduction of your paper . You can obtain an overall sense of what to do by reviewing studies that have utilized the same research design [e.g., using a case study approach]. This can help you develop an outline to follow for your own paper.

NOTE : Use the SAGE Research Methods Online and Cases and the SAGE Research Methods Videos databases to search for scholarly resources on how to apply specific research designs and methods . The Research Methods Online database contains links to more than 175,000 pages of SAGE publisher's book, journal, and reference content on quantitative, qualitative, and mixed research methodologies. Also included is a collection of case studies of social research projects that can be used to help you better understand abstract or complex methodological concepts. The Research Methods Videos database contains hours of tutorials, interviews, video case studies, and mini-documentaries covering the entire research process.

Creswell, John W. and J. David Creswell. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches . 5th edition. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2018; De Vaus, D. A. Research Design in Social Research . London: SAGE, 2001; Gorard, Stephen. Research Design: Creating Robust Approaches for the Social Sciences . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2013; Leedy, Paul D. and Jeanne Ellis Ormrod. Practical Research: Planning and Design . Tenth edition. Boston, MA: Pearson, 2013; Vogt, W. Paul, Dianna C. Gardner, and Lynne M. Haeffele. When to Use What Research Design . New York: Guilford, 2012.

Action Research Design

Definition and Purpose

The essentials of action research design follow a characteristic cycle whereby initially an exploratory stance is adopted, where an understanding of a problem is developed and plans are made for some form of interventionary strategy. Then the intervention is carried out [the "action" in action research] during which time, pertinent observations are collected in various forms. The new interventional strategies are carried out, and this cyclic process repeats, continuing until a sufficient understanding of [or a valid implementation solution for] the problem is achieved. The protocol is iterative or cyclical in nature and is intended to foster deeper understanding of a given situation, starting with conceptualizing and particularizing the problem and moving through several interventions and evaluations.

What do these studies tell you ?

- This is a collaborative and adaptive research design that lends itself to use in work or community situations.

- Design focuses on pragmatic and solution-driven research outcomes rather than testing theories.

- When practitioners use action research, it has the potential to increase the amount they learn consciously from their experience; the action research cycle can be regarded as a learning cycle.

- Action research studies often have direct and obvious relevance to improving practice and advocating for change.

- There are no hidden controls or preemption of direction by the researcher.

What these studies don't tell you ?

- It is harder to do than conducting conventional research because the researcher takes on responsibilities of advocating for change as well as for researching the topic.

- Action research is much harder to write up because it is less likely that you can use a standard format to report your findings effectively [i.e., data is often in the form of stories or observation].

- Personal over-involvement of the researcher may bias research results.

- The cyclic nature of action research to achieve its twin outcomes of action [e.g. change] and research [e.g. understanding] is time-consuming and complex to conduct.

- Advocating for change usually requires buy-in from study participants.

Coghlan, David and Mary Brydon-Miller. The Sage Encyclopedia of Action Research . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2014; Efron, Sara Efrat and Ruth Ravid. Action Research in Education: A Practical Guide . New York: Guilford, 2013; Gall, Meredith. Educational Research: An Introduction . Chapter 18, Action Research. 8th ed. Boston, MA: Pearson/Allyn and Bacon, 2007; Gorard, Stephen. Research Design: Creating Robust Approaches for the Social Sciences . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2013; Kemmis, Stephen and Robin McTaggart. “Participatory Action Research.” In Handbook of Qualitative Research . Norman Denzin and Yvonna S. Lincoln, eds. 2nd ed. (Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE, 2000), pp. 567-605; McNiff, Jean. Writing and Doing Action Research . London: Sage, 2014; Reason, Peter and Hilary Bradbury. Handbook of Action Research: Participative Inquiry and Practice . Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE, 2001.

Case Study Design

A case study is an in-depth study of a particular research problem rather than a sweeping statistical survey or comprehensive comparative inquiry. It is often used to narrow down a very broad field of research into one or a few easily researchable examples. The case study research design is also useful for testing whether a specific theory and model actually applies to phenomena in the real world. It is a useful design when not much is known about an issue or phenomenon.

- Approach excels at bringing us to an understanding of a complex issue through detailed contextual analysis of a limited number of events or conditions and their relationships.

- A researcher using a case study design can apply a variety of methodologies and rely on a variety of sources to investigate a research problem.

- Design can extend experience or add strength to what is already known through previous research.

- Social scientists, in particular, make wide use of this research design to examine contemporary real-life situations and provide the basis for the application of concepts and theories and the extension of methodologies.

- The design can provide detailed descriptions of specific and rare cases.

- A single or small number of cases offers little basis for establishing reliability or to generalize the findings to a wider population of people, places, or things.

- Intense exposure to the study of a case may bias a researcher's interpretation of the findings.

- Design does not facilitate assessment of cause and effect relationships.

- Vital information may be missing, making the case hard to interpret.

- The case may not be representative or typical of the larger problem being investigated.

- If the criteria for selecting a case is because it represents a very unusual or unique phenomenon or problem for study, then your interpretation of the findings can only apply to that particular case.

Case Studies. Writing@CSU. Colorado State University; Anastas, Jeane W. Research Design for Social Work and the Human Services . Chapter 4, Flexible Methods: Case Study Design. 2nd ed. New York: Columbia University Press, 1999; Gerring, John. “What Is a Case Study and What Is It Good for?” American Political Science Review 98 (May 2004): 341-354; Greenhalgh, Trisha, editor. Case Study Evaluation: Past, Present and Future Challenges . Bingley, UK: Emerald Group Publishing, 2015; Mills, Albert J. , Gabrielle Durepos, and Eiden Wiebe, editors. Encyclopedia of Case Study Research . Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, 2010; Stake, Robert E. The Art of Case Study Research . Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE, 1995; Yin, Robert K. Case Study Research: Design and Theory . Applied Social Research Methods Series, no. 5. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE, 2003.

Causal Design

Causality studies may be thought of as understanding a phenomenon in terms of conditional statements in the form, “If X, then Y.” This type of research is used to measure what impact a specific change will have on existing norms and assumptions. Most social scientists seek causal explanations that reflect tests of hypotheses. Causal effect (nomothetic perspective) occurs when variation in one phenomenon, an independent variable, leads to or results, on average, in variation in another phenomenon, the dependent variable.

Conditions necessary for determining causality:

- Empirical association -- a valid conclusion is based on finding an association between the independent variable and the dependent variable.

- Appropriate time order -- to conclude that causation was involved, one must see that cases were exposed to variation in the independent variable before variation in the dependent variable.

- Nonspuriousness -- a relationship between two variables that is not due to variation in a third variable.

- Causality research designs assist researchers in understanding why the world works the way it does through the process of proving a causal link between variables and by the process of eliminating other possibilities.

- Replication is possible.

- There is greater confidence the study has internal validity due to the systematic subject selection and equity of groups being compared.

- Not all relationships are causal! The possibility always exists that, by sheer coincidence, two unrelated events appear to be related [e.g., Punxatawney Phil could accurately predict the duration of Winter for five consecutive years but, the fact remains, he's just a big, furry rodent].

- Conclusions about causal relationships are difficult to determine due to a variety of extraneous and confounding variables that exist in a social environment. This means causality can only be inferred, never proven.

- If two variables are correlated, the cause must come before the effect. However, even though two variables might be causally related, it can sometimes be difficult to determine which variable comes first and, therefore, to establish which variable is the actual cause and which is the actual effect.

Beach, Derek and Rasmus Brun Pedersen. Causal Case Study Methods: Foundations and Guidelines for Comparing, Matching, and Tracing . Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 2016; Bachman, Ronet. The Practice of Research in Criminology and Criminal Justice . Chapter 5, Causation and Research Designs. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Pine Forge Press, 2007; Brewer, Ernest W. and Jennifer Kubn. “Causal-Comparative Design.” In Encyclopedia of Research Design . Neil J. Salkind, editor. (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2010), pp. 125-132; Causal Research Design: Experimentation. Anonymous SlideShare Presentation; Gall, Meredith. Educational Research: An Introduction . Chapter 11, Nonexperimental Research: Correlational Designs. 8th ed. Boston, MA: Pearson/Allyn and Bacon, 2007; Trochim, William M.K. Research Methods Knowledge Base. 2006.

Cohort Design

Often used in the medical sciences, but also found in the applied social sciences, a cohort study generally refers to a study conducted over a period of time involving members of a population which the subject or representative member comes from, and who are united by some commonality or similarity. Using a quantitative framework, a cohort study makes note of statistical occurrence within a specialized subgroup, united by same or similar characteristics that are relevant to the research problem being investigated, rather than studying statistical occurrence within the general population. Using a qualitative framework, cohort studies generally gather data using methods of observation. Cohorts can be either "open" or "closed."

- Open Cohort Studies [dynamic populations, such as the population of Los Angeles] involve a population that is defined just by the state of being a part of the study in question (and being monitored for the outcome). Date of entry and exit from the study is individually defined, therefore, the size of the study population is not constant. In open cohort studies, researchers can only calculate rate based data, such as, incidence rates and variants thereof.

- Closed Cohort Studies [static populations, such as patients entered into a clinical trial] involve participants who enter into the study at one defining point in time and where it is presumed that no new participants can enter the cohort. Given this, the number of study participants remains constant (or can only decrease).

- The use of cohorts is often mandatory because a randomized control study may be unethical. For example, you cannot deliberately expose people to asbestos, you can only study its effects on those who have already been exposed. Research that measures risk factors often relies upon cohort designs.

- Because cohort studies measure potential causes before the outcome has occurred, they can demonstrate that these “causes” preceded the outcome, thereby avoiding the debate as to which is the cause and which is the effect.

- Cohort analysis is highly flexible and can provide insight into effects over time and related to a variety of different types of changes [e.g., social, cultural, political, economic, etc.].

- Either original data or secondary data can be used in this design.

- In cases where a comparative analysis of two cohorts is made [e.g., studying the effects of one group exposed to asbestos and one that has not], a researcher cannot control for all other factors that might differ between the two groups. These factors are known as confounding variables.

- Cohort studies can end up taking a long time to complete if the researcher must wait for the conditions of interest to develop within the group. This also increases the chance that key variables change during the course of the study, potentially impacting the validity of the findings.

- Due to the lack of randominization in the cohort design, its external validity is lower than that of study designs where the researcher randomly assigns participants.

Healy P, Devane D. “Methodological Considerations in Cohort Study Designs.” Nurse Researcher 18 (2011): 32-36; Glenn, Norval D, editor. Cohort Analysis . 2nd edition. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2005; Levin, Kate Ann. Study Design IV: Cohort Studies. Evidence-Based Dentistry 7 (2003): 51–52; Payne, Geoff. “Cohort Study.” In The SAGE Dictionary of Social Research Methods . Victor Jupp, editor. (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2006), pp. 31-33; Study Design 101. Himmelfarb Health Sciences Library. George Washington University, November 2011; Cohort Study. Wikipedia.

Cross-Sectional Design

Cross-sectional research designs have three distinctive features: no time dimension; a reliance on existing differences rather than change following intervention; and, groups are selected based on existing differences rather than random allocation. The cross-sectional design can only measure differences between or from among a variety of people, subjects, or phenomena rather than a process of change. As such, researchers using this design can only employ a relatively passive approach to making causal inferences based on findings.

- Cross-sectional studies provide a clear 'snapshot' of the outcome and the characteristics associated with it, at a specific point in time.

- Unlike an experimental design, where there is an active intervention by the researcher to produce and measure change or to create differences, cross-sectional designs focus on studying and drawing inferences from existing differences between people, subjects, or phenomena.

- Entails collecting data at and concerning one point in time. While longitudinal studies involve taking multiple measures over an extended period of time, cross-sectional research is focused on finding relationships between variables at one moment in time.

- Groups identified for study are purposely selected based upon existing differences in the sample rather than seeking random sampling.

- Cross-section studies are capable of using data from a large number of subjects and, unlike observational studies, is not geographically bound.

- Can estimate prevalence of an outcome of interest because the sample is usually taken from the whole population.

- Because cross-sectional designs generally use survey techniques to gather data, they are relatively inexpensive and take up little time to conduct.

- Finding people, subjects, or phenomena to study that are very similar except in one specific variable can be difficult.

- Results are static and time bound and, therefore, give no indication of a sequence of events or reveal historical or temporal contexts.

- Studies cannot be utilized to establish cause and effect relationships.

- This design only provides a snapshot of analysis so there is always the possibility that a study could have differing results if another time-frame had been chosen.

- There is no follow up to the findings.

Bethlehem, Jelke. "7: Cross-sectional Research." In Research Methodology in the Social, Behavioural and Life Sciences . Herman J Adèr and Gideon J Mellenbergh, editors. (London, England: Sage, 1999), pp. 110-43; Bourque, Linda B. “Cross-Sectional Design.” In The SAGE Encyclopedia of Social Science Research Methods . Michael S. Lewis-Beck, Alan Bryman, and Tim Futing Liao. (Thousand Oaks, CA: 2004), pp. 230-231; Hall, John. “Cross-Sectional Survey Design.” In Encyclopedia of Survey Research Methods . Paul J. Lavrakas, ed. (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2008), pp. 173-174; Helen Barratt, Maria Kirwan. Cross-Sectional Studies: Design Application, Strengths and Weaknesses of Cross-Sectional Studies. Healthknowledge, 2009. Cross-Sectional Study. Wikipedia.

Descriptive Design

Descriptive research designs help provide answers to the questions of who, what, when, where, and how associated with a particular research problem; a descriptive study cannot conclusively ascertain answers to why. Descriptive research is used to obtain information concerning the current status of the phenomena and to describe "what exists" with respect to variables or conditions in a situation.

- The subject is being observed in a completely natural and unchanged natural environment. True experiments, whilst giving analyzable data, often adversely influence the normal behavior of the subject [a.k.a., the Heisenberg effect whereby measurements of certain systems cannot be made without affecting the systems].

- Descriptive research is often used as a pre-cursor to more quantitative research designs with the general overview giving some valuable pointers as to what variables are worth testing quantitatively.

- If the limitations are understood, they can be a useful tool in developing a more focused study.

- Descriptive studies can yield rich data that lead to important recommendations in practice.

- Appoach collects a large amount of data for detailed analysis.

- The results from a descriptive research cannot be used to discover a definitive answer or to disprove a hypothesis.

- Because descriptive designs often utilize observational methods [as opposed to quantitative methods], the results cannot be replicated.

- The descriptive function of research is heavily dependent on instrumentation for measurement and observation.

Anastas, Jeane W. Research Design for Social Work and the Human Services . Chapter 5, Flexible Methods: Descriptive Research. 2nd ed. New York: Columbia University Press, 1999; Given, Lisa M. "Descriptive Research." In Encyclopedia of Measurement and Statistics . Neil J. Salkind and Kristin Rasmussen, editors. (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2007), pp. 251-254; McNabb, Connie. Descriptive Research Methodologies. Powerpoint Presentation; Shuttleworth, Martyn. Descriptive Research Design, September 26, 2008; Erickson, G. Scott. "Descriptive Research Design." In New Methods of Market Research and Analysis . (Northampton, MA: Edward Elgar Publishing, 2017), pp. 51-77; Sahin, Sagufta, and Jayanta Mete. "A Brief Study on Descriptive Research: Its Nature and Application in Social Science." International Journal of Research and Analysis in Humanities 1 (2021): 11; K. Swatzell and P. Jennings. “Descriptive Research: The Nuts and Bolts.” Journal of the American Academy of Physician Assistants 20 (2007), pp. 55-56; Kane, E. Doing Your Own Research: Basic Descriptive Research in the Social Sciences and Humanities . London: Marion Boyars, 1985.

Experimental Design

A blueprint of the procedure that enables the researcher to maintain control over all factors that may affect the result of an experiment. In doing this, the researcher attempts to determine or predict what may occur. Experimental research is often used where there is time priority in a causal relationship (cause precedes effect), there is consistency in a causal relationship (a cause will always lead to the same effect), and the magnitude of the correlation is great. The classic experimental design specifies an experimental group and a control group. The independent variable is administered to the experimental group and not to the control group, and both groups are measured on the same dependent variable. Subsequent experimental designs have used more groups and more measurements over longer periods. True experiments must have control, randomization, and manipulation.

- Experimental research allows the researcher to control the situation. In so doing, it allows researchers to answer the question, “What causes something to occur?”

- Permits the researcher to identify cause and effect relationships between variables and to distinguish placebo effects from treatment effects.

- Experimental research designs support the ability to limit alternative explanations and to infer direct causal relationships in the study.

- Approach provides the highest level of evidence for single studies.

- The design is artificial, and results may not generalize well to the real world.

- The artificial settings of experiments may alter the behaviors or responses of participants.

- Experimental designs can be costly if special equipment or facilities are needed.

- Some research problems cannot be studied using an experiment because of ethical or technical reasons.

- Difficult to apply ethnographic and other qualitative methods to experimentally designed studies.

Anastas, Jeane W. Research Design for Social Work and the Human Services . Chapter 7, Flexible Methods: Experimental Research. 2nd ed. New York: Columbia University Press, 1999; Chapter 2: Research Design, Experimental Designs. School of Psychology, University of New England, 2000; Chow, Siu L. "Experimental Design." In Encyclopedia of Research Design . Neil J. Salkind, editor. (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2010), pp. 448-453; "Experimental Design." In Social Research Methods . Nicholas Walliman, editor. (London, England: Sage, 2006), pp, 101-110; Experimental Research. Research Methods by Dummies. Department of Psychology. California State University, Fresno, 2006; Kirk, Roger E. Experimental Design: Procedures for the Behavioral Sciences . 4th edition. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2013; Trochim, William M.K. Experimental Design. Research Methods Knowledge Base. 2006; Rasool, Shafqat. Experimental Research. Slideshare presentation.

Exploratory Design

An exploratory design is conducted about a research problem when there are few or no earlier studies to refer to or rely upon to predict an outcome . The focus is on gaining insights and familiarity for later investigation or undertaken when research problems are in a preliminary stage of investigation. Exploratory designs are often used to establish an understanding of how best to proceed in studying an issue or what methodology would effectively apply to gathering information about the issue.

The goals of exploratory research are intended to produce the following possible insights:

- Familiarity with basic details, settings, and concerns.

- Well grounded picture of the situation being developed.

- Generation of new ideas and assumptions.

- Development of tentative theories or hypotheses.

- Determination about whether a study is feasible in the future.

- Issues get refined for more systematic investigation and formulation of new research questions.

- Direction for future research and techniques get developed.

- Design is a useful approach for gaining background information on a particular topic.

- Exploratory research is flexible and can address research questions of all types (what, why, how).

- Provides an opportunity to define new terms and clarify existing concepts.

- Exploratory research is often used to generate formal hypotheses and develop more precise research problems.

- In the policy arena or applied to practice, exploratory studies help establish research priorities and where resources should be allocated.

- Exploratory research generally utilizes small sample sizes and, thus, findings are typically not generalizable to the population at large.

- The exploratory nature of the research inhibits an ability to make definitive conclusions about the findings. They provide insight but not definitive conclusions.

- The research process underpinning exploratory studies is flexible but often unstructured, leading to only tentative results that have limited value to decision-makers.

- Design lacks rigorous standards applied to methods of data gathering and analysis because one of the areas for exploration could be to determine what method or methodologies could best fit the research problem.

Cuthill, Michael. “Exploratory Research: Citizen Participation, Local Government, and Sustainable Development in Australia.” Sustainable Development 10 (2002): 79-89; Streb, Christoph K. "Exploratory Case Study." In Encyclopedia of Case Study Research . Albert J. Mills, Gabrielle Durepos and Eiden Wiebe, editors. (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2010), pp. 372-374; Taylor, P. J., G. Catalano, and D.R.F. Walker. “Exploratory Analysis of the World City Network.” Urban Studies 39 (December 2002): 2377-2394; Exploratory Research. Wikipedia.

Field Research Design

Sometimes referred to as ethnography or participant observation, designs around field research encompass a variety of interpretative procedures [e.g., observation and interviews] rooted in qualitative approaches to studying people individually or in groups while inhabiting their natural environment as opposed to using survey instruments or other forms of impersonal methods of data gathering. Information acquired from observational research takes the form of “ field notes ” that involves documenting what the researcher actually sees and hears while in the field. Findings do not consist of conclusive statements derived from numbers and statistics because field research involves analysis of words and observations of behavior. Conclusions, therefore, are developed from an interpretation of findings that reveal overriding themes, concepts, and ideas. More information can be found HERE .

- Field research is often necessary to fill gaps in understanding the research problem applied to local conditions or to specific groups of people that cannot be ascertained from existing data.

- The research helps contextualize already known information about a research problem, thereby facilitating ways to assess the origins, scope, and scale of a problem and to gage the causes, consequences, and means to resolve an issue based on deliberate interaction with people in their natural inhabited spaces.

- Enables the researcher to corroborate or confirm data by gathering additional information that supports or refutes findings reported in prior studies of the topic.

- Because the researcher in embedded in the field, they are better able to make observations or ask questions that reflect the specific cultural context of the setting being investigated.

- Observing the local reality offers the opportunity to gain new perspectives or obtain unique data that challenges existing theoretical propositions or long-standing assumptions found in the literature.

What these studies don't tell you

- A field research study requires extensive time and resources to carry out the multiple steps involved with preparing for the gathering of information, including for example, examining background information about the study site, obtaining permission to access the study site, and building trust and rapport with subjects.

- Requires a commitment to staying engaged in the field to ensure that you can adequately document events and behaviors as they unfold.

- The unpredictable nature of fieldwork means that researchers can never fully control the process of data gathering. They must maintain a flexible approach to studying the setting because events and circumstances can change quickly or unexpectedly.

- Findings can be difficult to interpret and verify without access to documents and other source materials that help to enhance the credibility of information obtained from the field [i.e., the act of triangulating the data].

- Linking the research problem to the selection of study participants inhabiting their natural environment is critical. However, this specificity limits the ability to generalize findings to different situations or in other contexts or to infer courses of action applied to other settings or groups of people.

- The reporting of findings must take into account how the researcher themselves may have inadvertently affected respondents and their behaviors.

Historical Design

The purpose of a historical research design is to collect, verify, and synthesize evidence from the past to establish facts that defend or refute a hypothesis. It uses secondary sources and a variety of primary documentary evidence, such as, diaries, official records, reports, archives, and non-textual information [maps, pictures, audio and visual recordings]. The limitation is that the sources must be both authentic and valid.

- The historical research design is unobtrusive; the act of research does not affect the results of the study.

- The historical approach is well suited for trend analysis.

- Historical records can add important contextual background required to more fully understand and interpret a research problem.

- There is often no possibility of researcher-subject interaction that could affect the findings.

- Historical sources can be used over and over to study different research problems or to replicate a previous study.

- The ability to fulfill the aims of your research are directly related to the amount and quality of documentation available to understand the research problem.

- Since historical research relies on data from the past, there is no way to manipulate it to control for contemporary contexts.

- Interpreting historical sources can be very time consuming.

- The sources of historical materials must be archived consistently to ensure access. This may especially challenging for digital or online-only sources.

- Original authors bring their own perspectives and biases to the interpretation of past events and these biases are more difficult to ascertain in historical resources.

- Due to the lack of control over external variables, historical research is very weak with regard to the demands of internal validity.

- It is rare that the entirety of historical documentation needed to fully address a research problem is available for interpretation, therefore, gaps need to be acknowledged.

Howell, Martha C. and Walter Prevenier. From Reliable Sources: An Introduction to Historical Methods . Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2001; Lundy, Karen Saucier. "Historical Research." In The Sage Encyclopedia of Qualitative Research Methods . Lisa M. Given, editor. (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2008), pp. 396-400; Marius, Richard. and Melvin E. Page. A Short Guide to Writing about History . 9th edition. Boston, MA: Pearson, 2015; Savitt, Ronald. “Historical Research in Marketing.” Journal of Marketing 44 (Autumn, 1980): 52-58; Gall, Meredith. Educational Research: An Introduction . Chapter 16, Historical Research. 8th ed. Boston, MA: Pearson/Allyn and Bacon, 2007.

Longitudinal Design

A longitudinal study follows the same sample over time and makes repeated observations. For example, with longitudinal surveys, the same group of people is interviewed at regular intervals, enabling researchers to track changes over time and to relate them to variables that might explain why the changes occur. Longitudinal research designs describe patterns of change and help establish the direction and magnitude of causal relationships. Measurements are taken on each variable over two or more distinct time periods. This allows the researcher to measure change in variables over time. It is a type of observational study sometimes referred to as a panel study.

- Longitudinal data facilitate the analysis of the duration of a particular phenomenon.

- Enables survey researchers to get close to the kinds of causal explanations usually attainable only with experiments.

- The design permits the measurement of differences or change in a variable from one period to another [i.e., the description of patterns of change over time].

- Longitudinal studies facilitate the prediction of future outcomes based upon earlier factors.

- The data collection method may change over time.

- Maintaining the integrity of the original sample can be difficult over an extended period of time.

- It can be difficult to show more than one variable at a time.

- This design often needs qualitative research data to explain fluctuations in the results.

- A longitudinal research design assumes present trends will continue unchanged.

- It can take a long period of time to gather results.

- There is a need to have a large sample size and accurate sampling to reach representativness.

Anastas, Jeane W. Research Design for Social Work and the Human Services . Chapter 6, Flexible Methods: Relational and Longitudinal Research. 2nd ed. New York: Columbia University Press, 1999; Forgues, Bernard, and Isabelle Vandangeon-Derumez. "Longitudinal Analyses." In Doing Management Research . Raymond-Alain Thiétart and Samantha Wauchope, editors. (London, England: Sage, 2001), pp. 332-351; Kalaian, Sema A. and Rafa M. Kasim. "Longitudinal Studies." In Encyclopedia of Survey Research Methods . Paul J. Lavrakas, ed. (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2008), pp. 440-441; Menard, Scott, editor. Longitudinal Research . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2002; Ployhart, Robert E. and Robert J. Vandenberg. "Longitudinal Research: The Theory, Design, and Analysis of Change.” Journal of Management 36 (January 2010): 94-120; Longitudinal Study. Wikipedia.

Meta-Analysis Design

Meta-analysis is an analytical methodology designed to systematically evaluate and summarize the results from a number of individual studies, thereby, increasing the overall sample size and the ability of the researcher to study effects of interest. The purpose is to not simply summarize existing knowledge, but to develop a new understanding of a research problem using synoptic reasoning. The main objectives of meta-analysis include analyzing differences in the results among studies and increasing the precision by which effects are estimated. A well-designed meta-analysis depends upon strict adherence to the criteria used for selecting studies and the availability of information in each study to properly analyze their findings. Lack of information can severely limit the type of analyzes and conclusions that can be reached. In addition, the more dissimilarity there is in the results among individual studies [heterogeneity], the more difficult it is to justify interpretations that govern a valid synopsis of results. A meta-analysis needs to fulfill the following requirements to ensure the validity of your findings:

- Clearly defined description of objectives, including precise definitions of the variables and outcomes that are being evaluated;

- A well-reasoned and well-documented justification for identification and selection of the studies;

- Assessment and explicit acknowledgment of any researcher bias in the identification and selection of those studies;

- Description and evaluation of the degree of heterogeneity among the sample size of studies reviewed; and,

- Justification of the techniques used to evaluate the studies.

- Can be an effective strategy for determining gaps in the literature.

- Provides a means of reviewing research published about a particular topic over an extended period of time and from a variety of sources.

- Is useful in clarifying what policy or programmatic actions can be justified on the basis of analyzing research results from multiple studies.

- Provides a method for overcoming small sample sizes in individual studies that previously may have had little relationship to each other.

- Can be used to generate new hypotheses or highlight research problems for future studies.

- Small violations in defining the criteria used for content analysis can lead to difficult to interpret and/or meaningless findings.

- A large sample size can yield reliable, but not necessarily valid, results.

- A lack of uniformity regarding, for example, the type of literature reviewed, how methods are applied, and how findings are measured within the sample of studies you are analyzing, can make the process of synthesis difficult to perform.

- Depending on the sample size, the process of reviewing and synthesizing multiple studies can be very time consuming.

Beck, Lewis W. "The Synoptic Method." The Journal of Philosophy 36 (1939): 337-345; Cooper, Harris, Larry V. Hedges, and Jeffrey C. Valentine, eds. The Handbook of Research Synthesis and Meta-Analysis . 2nd edition. New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 2009; Guzzo, Richard A., Susan E. Jackson and Raymond A. Katzell. “Meta-Analysis Analysis.” In Research in Organizational Behavior , Volume 9. (Greenwich, CT: JAI Press, 1987), pp 407-442; Lipsey, Mark W. and David B. Wilson. Practical Meta-Analysis . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 2001; Study Design 101. Meta-Analysis. The Himmelfarb Health Sciences Library, George Washington University; Timulak, Ladislav. “Qualitative Meta-Analysis.” In The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Data Analysis . Uwe Flick, editor. (Los Angeles, CA: Sage, 2013), pp. 481-495; Walker, Esteban, Adrian V. Hernandez, and Micheal W. Kattan. "Meta-Analysis: It's Strengths and Limitations." Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine 75 (June 2008): 431-439.

Mixed-Method Design

- Narrative and non-textual information can add meaning to numeric data, while numeric data can add precision to narrative and non-textual information.

- Can utilize existing data while at the same time generating and testing a grounded theory approach to describe and explain the phenomenon under study.

- A broader, more complex research problem can be investigated because the researcher is not constrained by using only one method.

- The strengths of one method can be used to overcome the inherent weaknesses of another method.

- Can provide stronger, more robust evidence to support a conclusion or set of recommendations.

- May generate new knowledge new insights or uncover hidden insights, patterns, or relationships that a single methodological approach might not reveal.

- Produces more complete knowledge and understanding of the research problem that can be used to increase the generalizability of findings applied to theory or practice.

- A researcher must be proficient in understanding how to apply multiple methods to investigating a research problem as well as be proficient in optimizing how to design a study that coherently melds them together.

- Can increase the likelihood of conflicting results or ambiguous findings that inhibit drawing a valid conclusion or setting forth a recommended course of action [e.g., sample interview responses do not support existing statistical data].

- Because the research design can be very complex, reporting the findings requires a well-organized narrative, clear writing style, and precise word choice.

- Design invites collaboration among experts. However, merging different investigative approaches and writing styles requires more attention to the overall research process than studies conducted using only one methodological paradigm.

- Concurrent merging of quantitative and qualitative research requires greater attention to having adequate sample sizes, using comparable samples, and applying a consistent unit of analysis. For sequential designs where one phase of qualitative research builds on the quantitative phase or vice versa, decisions about what results from the first phase to use in the next phase, the choice of samples and estimating reasonable sample sizes for both phases, and the interpretation of results from both phases can be difficult.

- Due to multiple forms of data being collected and analyzed, this design requires extensive time and resources to carry out the multiple steps involved in data gathering and interpretation.

Burch, Patricia and Carolyn J. Heinrich. Mixed Methods for Policy Research and Program Evaluation . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2016; Creswell, John w. et al. Best Practices for Mixed Methods Research in the Health Sciences . Bethesda, MD: Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences Research, National Institutes of Health, 2010Creswell, John W. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches . 4th edition. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 2014; Domínguez, Silvia, editor. Mixed Methods Social Networks Research . Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2014; Hesse-Biber, Sharlene Nagy. Mixed Methods Research: Merging Theory with Practice . New York: Guilford Press, 2010; Niglas, Katrin. “How the Novice Researcher Can Make Sense of Mixed Methods Designs.” International Journal of Multiple Research Approaches 3 (2009): 34-46; Onwuegbuzie, Anthony J. and Nancy L. Leech. “Linking Research Questions to Mixed Methods Data Analysis Procedures.” The Qualitative Report 11 (September 2006): 474-498; Tashakorri, Abbas and John W. Creswell. “The New Era of Mixed Methods.” Journal of Mixed Methods Research 1 (January 2007): 3-7; Zhanga, Wanqing. “Mixed Methods Application in Health Intervention Research: A Multiple Case Study.” International Journal of Multiple Research Approaches 8 (2014): 24-35 .

Observational Design

This type of research design draws a conclusion by comparing subjects against a control group, in cases where the researcher has no control over the experiment. There are two general types of observational designs. In direct observations, people know that you are watching them. Unobtrusive measures involve any method for studying behavior where individuals do not know they are being observed. An observational study allows a useful insight into a phenomenon and avoids the ethical and practical difficulties of setting up a large and cumbersome research project.

- Observational studies are usually flexible and do not necessarily need to be structured around a hypothesis about what you expect to observe [data is emergent rather than pre-existing].

- The researcher is able to collect in-depth information about a particular behavior.

- Can reveal interrelationships among multifaceted dimensions of group interactions.

- You can generalize your results to real life situations.

- Observational research is useful for discovering what variables may be important before applying other methods like experiments.

- Observation research designs account for the complexity of group behaviors.

- Reliability of data is low because seeing behaviors occur over and over again may be a time consuming task and are difficult to replicate.

- In observational research, findings may only reflect a unique sample population and, thus, cannot be generalized to other groups.

- There can be problems with bias as the researcher may only "see what they want to see."

- There is no possibility to determine "cause and effect" relationships since nothing is manipulated.

- Sources or subjects may not all be equally credible.

- Any group that is knowingly studied is altered to some degree by the presence of the researcher, therefore, potentially skewing any data collected.

Atkinson, Paul and Martyn Hammersley. “Ethnography and Participant Observation.” In Handbook of Qualitative Research . Norman K. Denzin and Yvonna S. Lincoln, eds. (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 1994), pp. 248-261; Observational Research. Research Methods by Dummies. Department of Psychology. California State University, Fresno, 2006; Patton Michael Quinn. Qualitiative Research and Evaluation Methods . Chapter 6, Fieldwork Strategies and Observational Methods. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2002; Payne, Geoff and Judy Payne. "Observation." In Key Concepts in Social Research . The SAGE Key Concepts series. (London, England: Sage, 2004), pp. 158-162; Rosenbaum, Paul R. Design of Observational Studies . New York: Springer, 2010;Williams, J. Patrick. "Nonparticipant Observation." In The Sage Encyclopedia of Qualitative Research Methods . Lisa M. Given, editor.(Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2008), pp. 562-563.

Philosophical Design

Understood more as an broad approach to examining a research problem than a methodological design, philosophical analysis and argumentation is intended to challenge deeply embedded, often intractable, assumptions underpinning an area of study. This approach uses the tools of argumentation derived from philosophical traditions, concepts, models, and theories to critically explore and challenge, for example, the relevance of logic and evidence in academic debates, to analyze arguments about fundamental issues, or to discuss the root of existing discourse about a research problem. These overarching tools of analysis can be framed in three ways:

- Ontology -- the study that describes the nature of reality; for example, what is real and what is not, what is fundamental and what is derivative?

- Epistemology -- the study that explores the nature of knowledge; for example, by what means does knowledge and understanding depend upon and how can we be certain of what we know?

- Axiology -- the study of values; for example, what values does an individual or group hold and why? How are values related to interest, desire, will, experience, and means-to-end? And, what is the difference between a matter of fact and a matter of value?

- Can provide a basis for applying ethical decision-making to practice.

- Functions as a means of gaining greater self-understanding and self-knowledge about the purposes of research.

- Brings clarity to general guiding practices and principles of an individual or group.

- Philosophy informs methodology.

- Refine concepts and theories that are invoked in relatively unreflective modes of thought and discourse.

- Beyond methodology, philosophy also informs critical thinking about epistemology and the structure of reality (metaphysics).

- Offers clarity and definition to the practical and theoretical uses of terms, concepts, and ideas.

- Limited application to specific research problems [answering the "So What?" question in social science research].

- Analysis can be abstract, argumentative, and limited in its practical application to real-life issues.

- While a philosophical analysis may render problematic that which was once simple or taken-for-granted, the writing can be dense and subject to unnecessary jargon, overstatement, and/or excessive quotation and documentation.

- There are limitations in the use of metaphor as a vehicle of philosophical analysis.

- There can be analytical difficulties in moving from philosophy to advocacy and between abstract thought and application to the phenomenal world.

Burton, Dawn. "Part I, Philosophy of the Social Sciences." In Research Training for Social Scientists . (London, England: Sage, 2000), pp. 1-5; Chapter 4, Research Methodology and Design. Unisa Institutional Repository (UnisaIR), University of South Africa; Jarvie, Ian C., and Jesús Zamora-Bonilla, editors. The SAGE Handbook of the Philosophy of Social Sciences . London: Sage, 2011; Labaree, Robert V. and Ross Scimeca. “The Philosophical Problem of Truth in Librarianship.” The Library Quarterly 78 (January 2008): 43-70; Maykut, Pamela S. Beginning Qualitative Research: A Philosophic and Practical Guide . Washington, DC: Falmer Press, 1994; McLaughlin, Hugh. "The Philosophy of Social Research." In Understanding Social Work Research . 2nd edition. (London: SAGE Publications Ltd., 2012), pp. 24-47; Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy . Metaphysics Research Lab, CSLI, Stanford University, 2013.

Sequential Design

- The researcher has a limitless option when it comes to sample size and the sampling schedule.

- Due to the repetitive nature of this research design, minor changes and adjustments can be done during the initial parts of the study to correct and hone the research method.

- This is a useful design for exploratory studies.

- There is very little effort on the part of the researcher when performing this technique. It is generally not expensive, time consuming, or workforce intensive.

- Because the study is conducted serially, the results of one sample are known before the next sample is taken and analyzed. This provides opportunities for continuous improvement of sampling and methods of analysis.

- The sampling method is not representative of the entire population. The only possibility of approaching representativeness is when the researcher chooses to use a very large sample size significant enough to represent a significant portion of the entire population. In this case, moving on to study a second or more specific sample can be difficult.

- The design cannot be used to create conclusions and interpretations that pertain to an entire population because the sampling technique is not randomized. Generalizability from findings is, therefore, limited.

- Difficult to account for and interpret variation from one sample to another over time, particularly when using qualitative methods of data collection.

Betensky, Rebecca. Harvard University, Course Lecture Note slides; Bovaird, James A. and Kevin A. Kupzyk. "Sequential Design." In Encyclopedia of Research Design . Neil J. Salkind, editor. (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2010), pp. 1347-1352; Cresswell, John W. Et al. “Advanced Mixed-Methods Research Designs.” In Handbook of Mixed Methods in Social and Behavioral Research . Abbas Tashakkori and Charles Teddle, eds. (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2003), pp. 209-240; Henry, Gary T. "Sequential Sampling." In The SAGE Encyclopedia of Social Science Research Methods . Michael S. Lewis-Beck, Alan Bryman and Tim Futing Liao, editors. (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2004), pp. 1027-1028; Nataliya V. Ivankova. “Using Mixed-Methods Sequential Explanatory Design: From Theory to Practice.” Field Methods 18 (February 2006): 3-20; Bovaird, James A. and Kevin A. Kupzyk. “Sequential Design.” In Encyclopedia of Research Design . Neil J. Salkind, ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2010; Sequential Analysis. Wikipedia.

Systematic Review

- A systematic review synthesizes the findings of multiple studies related to each other by incorporating strategies of analysis and interpretation intended to reduce biases and random errors.

- The application of critical exploration, evaluation, and synthesis methods separates insignificant, unsound, or redundant research from the most salient and relevant studies worthy of reflection.

- They can be use to identify, justify, and refine hypotheses, recognize and avoid hidden problems in prior studies, and explain data inconsistencies and conflicts in data.

- Systematic reviews can be used to help policy makers formulate evidence-based guidelines and regulations.

- The use of strict, explicit, and pre-determined methods of synthesis, when applied appropriately, provide reliable estimates about the effects of interventions, evaluations, and effects related to the overarching research problem investigated by each study under review.

- Systematic reviews illuminate where knowledge or thorough understanding of a research problem is lacking and, therefore, can then be used to guide future research.

- The accepted inclusion of unpublished studies [i.e., grey literature] ensures the broadest possible way to analyze and interpret research on a topic.

- Results of the synthesis can be generalized and the findings extrapolated into the general population with more validity than most other types of studies .

- Systematic reviews do not create new knowledge per se; they are a method for synthesizing existing studies about a research problem in order to gain new insights and determine gaps in the literature.

- The way researchers have carried out their investigations [e.g., the period of time covered, number of participants, sources of data analyzed, etc.] can make it difficult to effectively synthesize studies.

- The inclusion of unpublished studies can introduce bias into the review because they may not have undergone a rigorous peer-review process prior to publication. Examples may include conference presentations or proceedings, publications from government agencies, white papers, working papers, and internal documents from organizations, and doctoral dissertations and Master's theses.

Denyer, David and David Tranfield. "Producing a Systematic Review." In The Sage Handbook of Organizational Research Methods . David A. Buchanan and Alan Bryman, editors. ( Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 2009), pp. 671-689; Foster, Margaret J. and Sarah T. Jewell, editors. Assembling the Pieces of a Systematic Review: A Guide for Librarians . Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield, 2017; Gough, David, Sandy Oliver, James Thomas, editors. Introduction to Systematic Reviews . 2nd edition. Los Angeles, CA: Sage Publications, 2017; Gopalakrishnan, S. and P. Ganeshkumar. “Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis: Understanding the Best Evidence in Primary Healthcare.” Journal of Family Medicine and Primary Care 2 (2013): 9-14; Gough, David, James Thomas, and Sandy Oliver. "Clarifying Differences between Review Designs and Methods." Systematic Reviews 1 (2012): 1-9; Khan, Khalid S., Regina Kunz, Jos Kleijnen, and Gerd Antes. “Five Steps to Conducting a Systematic Review.” Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine 96 (2003): 118-121; Mulrow, C. D. “Systematic Reviews: Rationale for Systematic Reviews.” BMJ 309:597 (September 1994); O'Dwyer, Linda C., and Q. Eileen Wafford. "Addressing Challenges with Systematic Review Teams through Effective Communication: A Case Report." Journal of the Medical Library Association 109 (October 2021): 643-647; Okoli, Chitu, and Kira Schabram. "A Guide to Conducting a Systematic Literature Review of Information Systems Research." Sprouts: Working Papers on Information Systems 10 (2010); Siddaway, Andy P., Alex M. Wood, and Larry V. Hedges. "How to Do a Systematic Review: A Best Practice Guide for Conducting and Reporting Narrative Reviews, Meta-analyses, and Meta-syntheses." Annual Review of Psychology 70 (2019): 747-770; Torgerson, Carole J. “Publication Bias: The Achilles’ Heel of Systematic Reviews?” British Journal of Educational Studies 54 (March 2006): 89-102; Torgerson, Carole. Systematic Reviews . New York: Continuum, 2003.

- << Previous: Purpose of Guide

- Next: Design Flaws to Avoid >>

- Last Updated: May 7, 2024 9:40 AM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

5 Research design

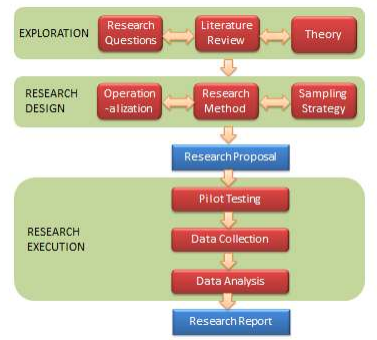

Research design is a comprehensive plan for data collection in an empirical research project. It is a ‘blueprint’ for empirical research aimed at answering specific research questions or testing specific hypotheses, and must specify at least three processes: the data collection process, the instrument development process, and the sampling process. The instrument development and sampling processes are described in the next two chapters, and the data collection process—which is often loosely called ‘research design’—is introduced in this chapter and is described in further detail in Chapters 9–12.

Broadly speaking, data collection methods can be grouped into two categories: positivist and interpretive. Positivist methods , such as laboratory experiments and survey research, are aimed at theory (or hypotheses) testing, while interpretive methods, such as action research and ethnography, are aimed at theory building. Positivist methods employ a deductive approach to research, starting with a theory and testing theoretical postulates using empirical data. In contrast, interpretive methods employ an inductive approach that starts with data and tries to derive a theory about the phenomenon of interest from the observed data. Often times, these methods are incorrectly equated with quantitative and qualitative research. Quantitative and qualitative methods refers to the type of data being collected—quantitative data involve numeric scores, metrics, and so on, while qualitative data includes interviews, observations, and so forth—and analysed (i.e., using quantitative techniques such as regression or qualitative techniques such as coding). Positivist research uses predominantly quantitative data, but can also use qualitative data. Interpretive research relies heavily on qualitative data, but can sometimes benefit from including quantitative data as well. Sometimes, joint use of qualitative and quantitative data may help generate unique insight into a complex social phenomenon that is not available from either type of data alone, and hence, mixed-mode designs that combine qualitative and quantitative data are often highly desirable.

Key attributes of a research design

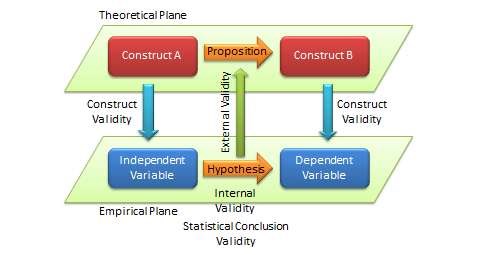

The quality of research designs can be defined in terms of four key design attributes: internal validity, external validity, construct validity, and statistical conclusion validity.

Internal validity , also called causality, examines whether the observed change in a dependent variable is indeed caused by a corresponding change in a hypothesised independent variable, and not by variables extraneous to the research context. Causality requires three conditions: covariation of cause and effect (i.e., if cause happens, then effect also happens; if cause does not happen, effect does not happen), temporal precedence (cause must precede effect in time), and spurious correlation, or there is no plausible alternative explanation for the change. Certain research designs, such as laboratory experiments, are strong in internal validity by virtue of their ability to manipulate the independent variable (cause) via a treatment and observe the effect (dependent variable) of that treatment after a certain point in time, while controlling for the effects of extraneous variables. Other designs, such as field surveys, are poor in internal validity because of their inability to manipulate the independent variable (cause), and because cause and effect are measured at the same point in time which defeats temporal precedence making it equally likely that the expected effect might have influenced the expected cause rather than the reverse. Although higher in internal validity compared to other methods, laboratory experiments are by no means immune to threats of internal validity, and are susceptible to history, testing, instrumentation, regression, and other threats that are discussed later in the chapter on experimental designs. Nonetheless, different research designs vary considerably in their respective level of internal validity.

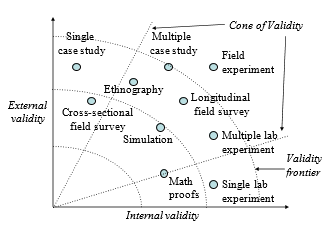

External validity or generalisability refers to whether the observed associations can be generalised from the sample to the population (population validity), or to other people, organisations, contexts, or time (ecological validity). For instance, can results drawn from a sample of financial firms in the United States be generalised to the population of financial firms (population validity) or to other firms within the United States (ecological validity)? Survey research, where data is sourced from a wide variety of individuals, firms, or other units of analysis, tends to have broader generalisability than laboratory experiments where treatments and extraneous variables are more controlled. The variation in internal and external validity for a wide range of research designs is shown in Figure 5.1.

Some researchers claim that there is a trade-off between internal and external validity—higher external validity can come only at the cost of internal validity and vice versa. But this is not always the case. Research designs such as field experiments, longitudinal field surveys, and multiple case studies have higher degrees of both internal and external validities. Personally, I prefer research designs that have reasonable degrees of both internal and external validities, i.e., those that fall within the cone of validity shown in Figure 5.1. But this should not suggest that designs outside this cone are any less useful or valuable. Researchers’ choice of designs are ultimately a matter of their personal preference and competence, and the level of internal and external validity they desire.

Construct validity examines how well a given measurement scale is measuring the theoretical construct that it is expected to measure. Many constructs used in social science research such as empathy, resistance to change, and organisational learning are difficult to define, much less measure. For instance, construct validity must ensure that a measure of empathy is indeed measuring empathy and not compassion, which may be difficult since these constructs are somewhat similar in meaning. Construct validity is assessed in positivist research based on correlational or factor analysis of pilot test data, as described in the next chapter.

Statistical conclusion validity examines the extent to which conclusions derived using a statistical procedure are valid. For example, it examines whether the right statistical method was used for hypotheses testing, whether the variables used meet the assumptions of that statistical test (such as sample size or distributional requirements), and so forth. Because interpretive research designs do not employ statistical tests, statistical conclusion validity is not applicable for such analysis. The different kinds of validity and where they exist at the theoretical/empirical levels are illustrated in Figure 5.2.

Improving internal and external validity

The best research designs are those that can ensure high levels of internal and external validity. Such designs would guard against spurious correlations, inspire greater faith in the hypotheses testing, and ensure that the results drawn from a small sample are generalisable to the population at large. Controls are required to ensure internal validity (causality) of research designs, and can be accomplished in five ways: manipulation, elimination, inclusion, and statistical control, and randomisation.

In manipulation , the researcher manipulates the independent variables in one or more levels (called ‘treatments’), and compares the effects of the treatments against a control group where subjects do not receive the treatment. Treatments may include a new drug or different dosage of drug (for treating a medical condition), a teaching style (for students), and so forth. This type of control is achieved in experimental or quasi-experimental designs, but not in non-experimental designs such as surveys. Note that if subjects cannot distinguish adequately between different levels of treatment manipulations, their responses across treatments may not be different, and manipulation would fail.

The elimination technique relies on eliminating extraneous variables by holding them constant across treatments, such as by restricting the study to a single gender or a single socioeconomic status. In the inclusion technique, the role of extraneous variables is considered by including them in the research design and separately estimating their effects on the dependent variable, such as via factorial designs where one factor is gender (male versus female). Such technique allows for greater generalisability, but also requires substantially larger samples. In statistical control , extraneous variables are measured and used as covariates during the statistical testing process.

Finally, the randomisation technique is aimed at cancelling out the effects of extraneous variables through a process of random sampling, if it can be assured that these effects are of a random (non-systematic) nature. Two types of randomisation are: random selection , where a sample is selected randomly from a population, and random assignment , where subjects selected in a non-random manner are randomly assigned to treatment groups.

Randomisation also ensures external validity, allowing inferences drawn from the sample to be generalised to the population from which the sample is drawn. Note that random assignment is mandatory when random selection is not possible because of resource or access constraints. However, generalisability across populations is harder to ascertain since populations may differ on multiple dimensions and you can only control for a few of those dimensions.

Popular research designs

As noted earlier, research designs can be classified into two categories—positivist and interpretive—depending on the goal of the research. Positivist designs are meant for theory testing, while interpretive designs are meant for theory building. Positivist designs seek generalised patterns based on an objective view of reality, while interpretive designs seek subjective interpretations of social phenomena from the perspectives of the subjects involved. Some popular examples of positivist designs include laboratory experiments, field experiments, field surveys, secondary data analysis, and case research, while examples of interpretive designs include case research, phenomenology, and ethnography. Note that case research can be used for theory building or theory testing, though not at the same time. Not all techniques are suited for all kinds of scientific research. Some techniques such as focus groups are best suited for exploratory research, others such as ethnography are best for descriptive research, and still others such as laboratory experiments are ideal for explanatory research. Following are brief descriptions of some of these designs. Additional details are provided in Chapters 9–12.

Experimental studies are those that are intended to test cause-effect relationships (hypotheses) in a tightly controlled setting by separating the cause from the effect in time, administering the cause to one group of subjects (the ‘treatment group’) but not to another group (‘control group’), and observing how the mean effects vary between subjects in these two groups. For instance, if we design a laboratory experiment to test the efficacy of a new drug in treating a certain ailment, we can get a random sample of people afflicted with that ailment, randomly assign them to one of two groups (treatment and control groups), administer the drug to subjects in the treatment group, but only give a placebo (e.g., a sugar pill with no medicinal value) to subjects in the control group. More complex designs may include multiple treatment groups, such as low versus high dosage of the drug or combining drug administration with dietary interventions. In a true experimental design , subjects must be randomly assigned to each group. If random assignment is not followed, then the design becomes quasi-experimental . Experiments can be conducted in an artificial or laboratory setting such as at a university (laboratory experiments) or in field settings such as in an organisation where the phenomenon of interest is actually occurring (field experiments). Laboratory experiments allow the researcher to isolate the variables of interest and control for extraneous variables, which may not be possible in field experiments. Hence, inferences drawn from laboratory experiments tend to be stronger in internal validity, but those from field experiments tend to be stronger in external validity. Experimental data is analysed using quantitative statistical techniques. The primary strength of the experimental design is its strong internal validity due to its ability to isolate, control, and intensively examine a small number of variables, while its primary weakness is limited external generalisability since real life is often more complex (i.e., involving more extraneous variables) than contrived lab settings. Furthermore, if the research does not identify ex ante relevant extraneous variables and control for such variables, such lack of controls may hurt internal validity and may lead to spurious correlations.

Field surveys are non-experimental designs that do not control for or manipulate independent variables or treatments, but measure these variables and test their effects using statistical methods. Field surveys capture snapshots of practices, beliefs, or situations from a random sample of subjects in field settings through a survey questionnaire or less frequently, through a structured interview. In cross-sectional field surveys , independent and dependent variables are measured at the same point in time (e.g., using a single questionnaire), while in longitudinal field surveys , dependent variables are measured at a later point in time than the independent variables. The strengths of field surveys are their external validity (since data is collected in field settings), their ability to capture and control for a large number of variables, and their ability to study a problem from multiple perspectives or using multiple theories. However, because of their non-temporal nature, internal validity (cause-effect relationships) are difficult to infer, and surveys may be subject to respondent biases (e.g., subjects may provide a ‘socially desirable’ response rather than their true response) which further hurts internal validity.

Secondary data analysis is an analysis of data that has previously been collected and tabulated by other sources. Such data may include data from government agencies such as employment statistics from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Services or development statistics by countries from the United Nations Development Program, data collected by other researchers (often used in meta-analytic studies), or publicly available third-party data, such as financial data from stock markets or real-time auction data from eBay. This is in contrast to most other research designs where collecting primary data for research is part of the researcher’s job. Secondary data analysis may be an effective means of research where primary data collection is too costly or infeasible, and secondary data is available at a level of analysis suitable for answering the researcher’s questions. The limitations of this design are that the data might not have been collected in a systematic or scientific manner and hence unsuitable for scientific research, since the data was collected for a presumably different purpose, they may not adequately address the research questions of interest to the researcher, and interval validity is problematic if the temporal precedence between cause and effect is unclear.

Case research is an in-depth investigation of a problem in one or more real-life settings (case sites) over an extended period of time. Data may be collected using a combination of interviews, personal observations, and internal or external documents. Case studies can be positivist in nature (for hypotheses testing) or interpretive (for theory building). The strength of this research method is its ability to discover a wide variety of social, cultural, and political factors potentially related to the phenomenon of interest that may not be known in advance. Analysis tends to be qualitative in nature, but heavily contextualised and nuanced. However, interpretation of findings may depend on the observational and integrative ability of the researcher, lack of control may make it difficult to establish causality, and findings from a single case site may not be readily generalised to other case sites. Generalisability can be improved by replicating and comparing the analysis in other case sites in a multiple case design .

Focus group research is a type of research that involves bringing in a small group of subjects (typically six to ten people) at one location, and having them discuss a phenomenon of interest for a period of one and a half to two hours. The discussion is moderated and led by a trained facilitator, who sets the agenda and poses an initial set of questions for participants, makes sure that the ideas and experiences of all participants are represented, and attempts to build a holistic understanding of the problem situation based on participants’ comments and experiences. Internal validity cannot be established due to lack of controls and the findings may not be generalised to other settings because of the small sample size. Hence, focus groups are not generally used for explanatory or descriptive research, but are more suited for exploratory research.

Action research assumes that complex social phenomena are best understood by introducing interventions or ‘actions’ into those phenomena and observing the effects of those actions. In this method, the researcher is embedded within a social context such as an organisation and initiates an action—such as new organisational procedures or new technologies—in response to a real problem such as declining profitability or operational bottlenecks. The researcher’s choice of actions must be based on theory, which should explain why and how such actions may cause the desired change. The researcher then observes the results of that action, modifying it as necessary, while simultaneously learning from the action and generating theoretical insights about the target problem and interventions. The initial theory is validated by the extent to which the chosen action successfully solves the target problem. Simultaneous problem solving and insight generation is the central feature that distinguishes action research from all other research methods, and hence, action research is an excellent method for bridging research and practice. This method is also suited for studying unique social problems that cannot be replicated outside that context, but it is also subject to researcher bias and subjectivity, and the generalisability of findings is often restricted to the context where the study was conducted.