Research Locale

Ai generator.

A research locale refers to the specific geographical area or location where a study or research is conducted. This locale is carefully chosen based on the study’s objectives, the population of interest, and the relevance of the location to the research questions. Selecting an appropriate research locale is crucial as it impacts the validity and generalizability of the study’s findings. The locale provides the context within which data is collected, analyzed, and interpreted, making it a fundamental aspect of the research action plan . In studies focusing on environmental or biological aspects, understanding the endemic species within the research locale is essential, as these species are native to the area and can significantly influence the research outcomes.

What is Research Locale?

Research locale refers to the specific geographical location or setting where a study is conducted. This area is chosen based on the objectives and requirements of the research, as it provides the necessary context and environment for gathering relevant data. The research locale can range from a small community or institution to a larger region or multiple sites, depending on the scope of the study.

Examples of Research Locale

- Schools: Conducting a study on the effectiveness of a new teaching method in elementary, middle, or high schools.

- Universities: Researching student behaviors, learning outcomes, or the impact of specific academic programs in higher education settings.

- Hospitals: Investigating patient recovery rates or the efficacy of new treatments in a hospital setting.

- Clinics: Studying the accessibility and quality of healthcare services in local clinics.

- Urban Areas: Examining the effects of urbanization on residents’ quality of life, health, or social interactions.

- Rural Areas: Researching agricultural practices, rural healthcare accessibility, or educational challenges in rural settings.

- Corporations: Studying employee satisfaction, productivity, or the impact of corporate policies in large companies.

- Small Businesses: Investigating the challenges and successes of small business operations in local communities.

- Parks: Researching the usage patterns and benefits of public parks for community health and well-being.

- Libraries: Examining the role of public libraries in community education and engagement.

- Countries: Conducting cross-national studies on economic development, public health, or educational systems.

- Regions: Researching environmental impacts, cultural practices, or regional policies in specific areas such as the Midwest, the Himalayas, or the Amazon Basin.

- Social Media Platforms: Studying user behavior, misinformation spread, or social interactions on platforms like Facebook, Twitter, or Instagram.

- Virtual Communities: Investigating the dynamics of online forums, gaming communities, or e-learning environments.

Research Locale Examples in School

- Classroom Dynamics: Investigating how seating arrangements affect student interaction and participation in a third-grade classroom.

- Reading Programs: Assessing the impact of a new phonics-based reading program on literacy rates among first graders.

- Bullying Prevention: Studying the effectiveness of anti-bullying programs and policies in reducing incidents of bullying among sixth to eighth graders.

- STEM Education: Evaluating the success of extracurricular STEM clubs in improving students’ interest and performance in science and math subjects.

- College Preparation: Analyzing how different college preparatory programs influence the readiness and success of students applying to universities.

- Sports Participation: Researching the correlation between participation in high school sports and academic performance, self-esteem, and social skills.

- Inclusive Practices: Investigating the effectiveness of inclusive education practices on the social integration and academic achievements of students with special needs.

- Assistive Technologies: Evaluating the impact of various assistive technologies on the learning outcomes of students with disabilities.

- Curriculum Impact: Assessing the impact of specialized curricula (e.g., arts, sciences, or technology-focused) on student engagement and academic performance.

- Student Diversity: Studying the effects of a diverse student body on cultural awareness and interpersonal skills among students.

- Innovative Teaching Methods: Examining the outcomes of innovative teaching methods and curricula implemented in charter schools compared to traditional public schools.

- Parental Involvement: Researching how parental involvement in charter schools affects student motivation and achievement.

- Residential Life: Investigating the effects of boarding school environments on student independence, social development, and academic performance.

- Extracurricular Activities: Studying the role of extracurricular activities in shaping the overall development and well-being of boarding school students.

- Multicultural Education: Examining the impact of multicultural education programs on students’ global awareness and acceptance of cultural diversity.

- Language Acquisition: Researching the effectiveness of bilingual education programs in international schools on students’ proficiency in multiple languages.

Examples of Research Locale Quantitative

- Measuring the effect of a new math curriculum on standardized test scores among fourth-grade students.

- Analyzing the relationship between breakfast programs and student attendance rates.

- Quantifying the impact of restorative justice practices on the frequency of disciplinary actions.

- Assessing the correlation between educational technology use in classrooms and student achievement in science.

- Investigating factors influencing graduation rates, including socio-economic status and teacher-student ratios.

- Evaluating the effectiveness of college preparatory programs by comparing college admission rates of participants versus non-participants.

- Measuring the progress of students with Individualized Education Plans (IEPs) in academic performance and behavioral improvements.

- Quantifying the impact of different assistive technologies on academic success.

- Comparing academic performance data between students in magnet schools and traditional public schools.

- Analyzing enrollment data to determine the diversity of student populations and its impact on academic outcomes.

- Assessing academic outcomes by comparing standardized test scores between charter school students and traditional public school students.

- Measuring teacher retention rates in charter schools versus public schools.

- Quantifying academic performance by analyzing GPA and standardized test scores of boarding school students.

- Conducting surveys to collect quantitative data on student well-being and correlating it with academic success.

- Measuring language proficiency levels in bilingual programs using standardized language tests.

- Using surveys to quantify students’ cultural competence and its relationship with academic performance.

Examples of Research Locale Qualitative

- Classroom Interaction: Observing and documenting student-teacher interactions to understand the dynamics of effective teaching strategies.

- Playground Behavior: Conducting interviews and focus groups with students to explore their social interactions and conflict resolution methods during recess.

- Peer Relationships: Exploring the nature of peer relationships and their impact on students’ emotional well-being through in-depth interviews.

- Curriculum Implementation: Gathering teacher narratives on the challenges and successes of implementing a new curriculum.

- Extracurricular Activities: Investigating students’ experiences and perceptions of participating in extracurricular activities through case studies and interviews.

- Career Aspirations: Conducting focus groups to understand how students’ backgrounds and school experiences shape their career aspirations.

- Parent Perspectives: Interviewing parents of students with special needs to gather insights into their experiences and satisfaction with the educational services provided.

- Teacher Experiences: Collecting narratives from special education teachers about their experiences, challenges, and strategies in teaching students with diverse needs.

- Student Motivation: Exploring the factors that motivate students to attend and succeed in magnet schools through in-depth interviews.

- Cultural Integration: Studying how students from diverse backgrounds integrate and interact within the specialized environment of magnet schools.

- Teacher Retention: Investigating the reasons behind teacher retention and turnover in charter schools through qualitative interviews with current and former teachers.

- Parent Involvement: Conducting case studies to understand the role and impact of parent involvement in charter school communities.

- Residential Life: Exploring students’ experiences of residential life, focusing on their personal growth and social development through narrative inquiry.

- Alumni Perspectives: Interviewing alumni to gather insights on how their boarding school experience has influenced their post-graduation life.

- Cultural Adaptation: Examining the experiences of expatriate students adapting to new cultural environments through ethnographic studies.

- Multilingual Education: Conducting interviews with teachers and students to explore the challenges and benefits of multilingual education in international schools.

Research locale Sample Paragraph

This study was conducted in three public high schools located in the urban district of Greenville, North Carolina. The selected schools—Greenville High School, Central High School, and Riverside High School—were chosen for their diverse student populations and varying levels of technological integration in the classroom. Each school enrolls approximately 1,200 students, offering a mix of Advanced Placement (AP) courses, vocational training, and special education programs. Greenville High School recently implemented a 1:1 laptop initiative, providing each student with a personal device for educational use. Central High School utilizes a blended learning model with shared computer labs and mobile tablet carts, while Riverside High School maintains a more traditional approach with limited use of digital tools. This study focuses on 11th-grade students enrolled in English and Mathematics courses, examining how different levels of technology integration impact student engagement and academic performance. Data was collected through a combination of student surveys, standardized test scores, classroom observations, and interviews with teachers and administrators, aiming to provide comprehensive insights into the effectiveness of technology-enhanced learning environments.

How to write Research Locale?

The research locale section of your study provides a detailed description of the location where the research will be conducted. This section is crucial for contextualizing your research and helping readers understand the setting and its potential influence on your study. Here are the steps to write an effective research locale:

1. Introduction to the Locale

- Name and Description : Start by naming the locale and providing a brief description. Include geographic, demographic, and cultural aspects.

- Relevance : Explain why this locale is suitable for your study.

2. Geographic Details

- Location : Provide precise details about the location, including the city, state, country, and any specific areas within these larger regions.

- Map and Boundaries : If possible, include a map to illustrate the locale and its boundaries.

3. Demographic Information

- Population : Describe the population size, density, and composition. Include information on age, gender, ethnicity, and socio-economic status.

- Community Characteristics : Mention any unique characteristics of the community that are relevant to your study.

4. Socio-Economic and Cultural Context

- Economic Activities : Outline the primary economic activities and employment sectors in the locale.

- Cultural Practices : Highlight cultural practices, traditions, and values that might influence the study.

5. Educational and Institutional Context

- Schools and Institutions : If relevant, describe the educational institutions, such as schools or universities, and their role in the community.

- Other Institutions : Mention any other institutions (e.g., healthcare, religious) that might be relevant.

6. Accessibility and Infrastructure

- Transportation : Explain the transportation infrastructure, including roads, public transit, and accessibility.

- Facilities : Mention key facilities like hospitals, libraries, and recreational centers.

7. Environmental Factors

- Climate and Geography : Describe the climate and any geographic features that could impact your research.

- Environmental Conditions : Note any environmental conditions, such as pollution or natural resources, relevant to your study.

FAQ’s

Why is the research locale important.

The research locale is crucial because it influences the study’s context, data collection, and findings’ applicability.

How do you select a research locale?

Selection involves considering relevance to the research question, accessibility, availability of data, and potential impact on results.

What factors influence the choice of a research locale?

Factors include geographical location, demographic characteristics, cultural context, and logistical feasibility.

Can a study have multiple research locales?

Yes, studies can include multiple locales to compare different environments or enhance the study’s generalizability.

How does the research locale affect data collection?

The locale can determine the methods used, participant availability, and types of data collected.

What is the difference between research locale and research setting?

The research locale is the broader geographical area, while the research setting refers to the specific place within that locale.

How do you describe a research locale in a study?

Include geographical details, demographic information, cultural characteristics, and any relevant historical or social context.

Why might a researcher choose an urban research locale?

Urban locales offer diverse populations, accessible resources, and varied social dynamics.

Why might a researcher choose a rural research locale?

Rural locales provide unique insights into less-studied populations, community dynamics, and environmental factors.

What role does the research locale play in qualitative research?

In qualitative research, the locale is integral to understanding participants’ lived experiences and contextual factors.

Text prompt

- Instructive

- Professional

10 Examples of Public speaking

20 Examples of Gas lighting

New York City Neighborhood Research: Locale

- How To Site See

- Local History

- Building Research

- Demographic

- NYPL Research Guides

- What Changed?

- Patterns, Connections, Associations

In approaching a locale for research, there are a number of questions to ask first, as triggers, to get yourself situated, and to inhabit the modes and thinking of a researcher. Each tab in this section covers the types of questions it will help to ask in getting started.

What is there? Make a list of notable locales in the area: monuments, parks, department stores, factories, museums, bars, schools, office buildings, diners. These things are what give a neighborhood its physical, behavioral, and historical character.

What does it look like? What did it look like? At the reference desk, images are one of the most sought after resources in neighborhood research. Photographs might communicate extra dimensions of an area that are not conveyed through nonvisual materials. They also provide a vivid sense of immediacy to the past, as if crossing through the wormhole. Images of the built environment and street life enable a more intimate and possibly more profound understanding of a place.

At the other end of the spectrum - take a look at what is still there, even after all those years. The Bridge Cafe at 279 Water Street is sadly no longer in operation, but the building itself supposedly dates to 1794 , and still appears as if behind the upstairs windows live oystermen and sailmakers. Or, sure, Times Square has been the entertainment district for over 100 years, but the changes in the neighborhood surpass the size of crowds on New Years Eve.

Also, the tour was simply the narrative form: this idea applies to whatever form your research ultimately takes (article, book, exhibit, etc.).

Another pattern might be statues - the statues themselves are the pattern, the art form and mode of representation - which then serves the opportunity to note connections or associations between whatever they may represent.

Patterns, connections, and associations are there. Find them.

- << Previous: How To Site See

- Next: Subject >>

- Last Updated: Jun 22, 2024 10:20 AM

- URL: https://libguides.nypl.org/neighborhoodresearch

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Chapter III METHODOLOGY Research Locale

Related Papers

Amanda Hunn

Petra Boynton

Journal of Chemical Education

Diane M Bunce

André Pereira

Satyajit Behera

Measurement and Data Collection. Primary data, Secondary data, Design of questionnaire ; Sampling fundamentals and sample designs. Measurement and Scaling Techniques, Data Processing

Roberto Jr. P Tacbobo

International Journal of Quantitative and Qualitative Research Methods

Reuben Bihu

Questionnaire surveys dominate the methodological designs in educational and social studies, particularly in developing countries. It is conceived practically easy to adopt study protocols under the design, and off course most researchers would prefer using questionnaire survey studies designed in most simple ways. Such studies provide the most economical way of gathering information from representations giving data that apply to general populations. As such, the desire for cost management and redeeming time have caused many researchers to adapt, adopt and apply the designs, even where it doesn’t qualify for the study contexts. Consequently, they are confronted by managing consistent errors and mismatching study protocols and methodologies. However, the benefits of using the design are real and popular even to the novice researchers and the problems arising from the design are always easily address by experienced researchers

Annali dell'Istituto superiore di sanità

Chiara de Waure

This article describes methodological issues of the "Sportello Salute Giovani" project ("Youth Health Information Desk"), a multicenter study aimed at assessing the health status and attitudes and behaviours of university students in Italy. The questionnaire used to carry out the study was adapted from the Italian health behaviours in school-aged children (HBSC) project and consisted of 93 items addressing: demographics; nutritional habits and status; physical activity; lifestyles; reproductive and preconception health; health and satisfaction of life; attitudes and behaviours toward academic study and new technologies. The questionnaire was administered to a pool of 12 000 students from 18 to 30 years of age who voluntary decided to participate during classes held at different Italian faculties or at the three "Sportello Salute Giovani" centers which were established in the three sites of the Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore (Catholic University of...

Trisha Greenhalgh

Loading Preview

Sorry, preview is currently unavailable. You can download the paper by clicking the button above.

RELATED PAPERS

Ebenezer Consultan

RENA MAHINAY LIHAYLIHAY

Rena LihayLihay

Daniela Garcia

De Wet Schutte

International Journal of Management, Technology, and Social Sciences (IJMTS)

Srinivas Publication , Sreeramana Aithal

Carrie Bretz

Assessing Governance Matrices in Co-Operative Financial Institutions (CFI's)

Ivan Steenkamp

Sallie Newell

Burcu Akhun

Medical Teacher

Anthony Artino

João Bandeira De Melo Papelo

Nipuni Rangika

DGeanene White

Abla BENBELLAL

Saleha Habibullah

Indian Journal of Anaesthesia

Narayana Yaddanapudi

Student BMJ

Mitra Amini

Maribel Peró Cebollero

Dolores Frias-Navarro

Journal of Family Planning and Reproductive Health Care

Gill Wakley

Godwill Medukenya

Edrine Wanyama

Cut Eka Para Samya

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

Chapter 3 Research Design and Methodology

- October 2019

- Thesis for: Master of Arts in Teaching

- University of Perpetual Help System Jonelta Pueblo de Panay

Discover the world's research

- 25+ million members

- 160+ million publication pages

- 2.3+ billion citations

- Recruit researchers

- Join for free

- Login Email Tip: Most researchers use their institutional email address as their ResearchGate login Password Forgot password? Keep me logged in Log in or Continue with Google Welcome back! Please log in. Email · Hint Tip: Most researchers use their institutional email address as their ResearchGate login Password Forgot password? Keep me logged in Log in or Continue with Google No account? Sign up

What is locale of the study means?

Insight from top 5 papers.

The locale of a study refers to the specific geographical or cultural context in which the research is conducted. It involves considering the unique characteristics, dynamics, and interests of the local community being studied [1] [3] . For instance, in the context of local journalism, the locale of the study would involve focusing on how digital media outlets in different countries address localized information and connect with their audiences [1] . Similarly, in the realm of local therapy, the locale of the study would pertain to how specific treatments are implemented and their effectiveness within a particular population or region [2] . Understanding the locale of a study is crucial for researchers to tailor their methods, interventions, and interpretations to suit the specific context being investigated.

Source Papers (5)

| Title | Insight |

|---|---|

| , 1 Talk with Paper | |

| , , - 33 PDF Talk with Paper | |

| - 3 Talk with Paper | |

| - 1 PDF Talk with Paper | |

| , , PDF Talk with Paper |

Related Questions

Conducting local studies offers unique advantages compared to national or international studies. Local studies, such as historical local studies in Ukraine, play a crucial role in fostering national self-awareness and preserving historical memory, contributing to the consolidation of regional traditions and nation-building . They provide insights into the intricacies of local politics and policies, shedding light on power distribution, implementation of policies, and the relationship between performance and legitimacy within decentralized systems like in Italy . Additionally, local studies emphasize the importance of approaching local counterparts with patience, empathy, and cultural humility, enabling a deeper understanding of the complexities of the local setting in research related to peace and conflict studies . Furthermore, local spatial analysis frameworks, like Geographically Weighted Regression, offer a nuanced understanding of spatial relationships and behavior, highlighting the significance of considering local variations in spatial processes .

Research locale explanation refers to the process of analyzing and understanding complex machine learning models in the context of a specific instance or sentence . It involves generating a set of neighbor instances based on the presence or absence of the sentence and training a linear model to fit the output of the original model on these instances . The goal is to provide a local explanation for the model's predictions, improving interpretation efficiency and achieving similar interpretation effects . This method can be applied to text classification models and has shown promising results in terms of training time reduction and interpretation improvement .

The significance of the studies can be seen in their contributions to various fields. Patnaik's study on institutional change in the rural context highlights the importance of reducing power inequities and identifying institutional champions . Liao's research on African American college students addresses the compounding effects of ethnicity and socioeconomic identity, providing insights into their experiences during the first year of university study . The study on managerial decisions in the internal affairs bodies of Russia emphasizes the need for interactive technologies in training sessions, enhancing the practical component of learning . Shen's study on westerly wind's impact on climate change emphasizes its role in controlling the North bound of the East Asian monsoon and its significance in Asian and global climate changes . Gabr's research on achene and pappus morphological characters contributes to the identification and differentiation of Asteraceae species, supporting their use in taxonomical studies .

The meaning of the study is multifaceted and varies depending on the perspective. In the context of education, studying is seen as a means to educate oneself and achieve educational purposes . It is an activity that has both pedagogical value and educational value in itself, as the very act of studying educates the individual . From a linguistic perspective, the concept of study is closely related to other concepts such as knowledge, action, and science . Language plays a crucial role in shaping the cultural characteristics associated with the study, and proverbs reflect the collective knowledge and consciousness related to this concept . In the realm of formal logic, studying involves the analysis, clarification, and precise formulation of ordinary statements using mathematical notation . Overall, the study encompasses the acquisition of knowledge, the process of education, and the exploration of meaning in various contexts.

Finding related studies in local can be challenging, especially when relying on structured scholar networks that are computationally complex and difficult to construct in practice . However, a novel approach has been proposed to detect scholarly communities directly from large textual corpora . By measuring the mutual relatedness of researchers through their textual distance, communities can be identified based on vector clusters . This method has shown comparable performance with state-of-the-art methods and has the advantage of detecting communities directly from unstructured texts . Additionally, handbooks and reference works in economic geography serve as important collective focusing devices to summarize and critically examine the state of the art in the field . These resources provide a high-quality collection of individual scholarship, offering a critical and thought-provoking engagement with economic geographies . Therefore, researchers can explore these resources to find related studies in the field of economic geography .

Trending Questions

European countries conceptualize risk management in tourism as a multifaceted approach that addresses various uncertainties impacting the industry. This involves identifying risks, implementing mitigation strategies, and fostering resilience among tourism enterprises. ## Risk Identification and Classification - European tourism faces diverse risks, including natural disasters, political instability, and health crises like COVID-19, which significantly affected international arrivals. - A systematic classification of these risks helps in understanding their impact on tourism activities and developing targeted management strategies. ## Mitigation Strategies - During the COVID-19 pandemic, EU member states employed integrated protective measures to support the tourism sector, highlighting the need for coordinated risk management efforts. - Effective risk management systems in tourism enterprises focus on identifying risks and implementing countermeasures, which can enhance financial stability and operational resilience. ## Behavioral Aspects - Tourists' risk decision-making is influenced by the behavior of others, indicating that destination management can play a crucial role in shaping risk perceptions and responses. While the focus on risk management is essential for sustaining tourism, it is also important to recognize that excessive risk aversion may deter potential visitors, suggesting a balance between safety and attraction is necessary for industry growth.

Identifying fumocoumarins qualitatively involves various analytical methods that ensure accurate detection and quantification. The following methods are commonly employed in research and industry settings. ## Solid-Phase Extraction (SPE) with LC-MS - SPE is utilized to extract furanocoumarins from complex matrices, such as cosmetics, followed by analysis using liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS). This method allows for the detection of multiple target compounds with satisfactory recovery rates. ## High-Performance Thin-Layer Chromatography (HPTLC) - HPTLC methods have been developed for the qualitative and quantitative analysis of furocoumarins in essential oils. This technique is efficient and provides a linear range for quantification, making it suitable for routine quality control. ## QuEChERS Extraction with UPLC-MS/MS - The QuEChERS method, combined with ultra-performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (UPLC-MS/MS), is effective for analyzing furocoumarins in food products. This approach allows for the simultaneous detection of multiple furocoumarins. ## Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS) - GC-MS, following SPE, is another method used for the simultaneous analysis of coumarins and furocoumarins, providing high sensitivity and accuracy. While these methods are robust, they can be resource-intensive, prompting ongoing research into more efficient techniques for routine analysis.

The use of preservatives in food supplementation poses several potential health risks, primarily due to the synthetic chemicals involved. Research indicates that these additives can lead to various adverse health effects, particularly in vulnerable populations such as children and pregnant women. ## Health Risks Associated with Preservatives - **Adverse Reactions**: Common preservatives like sodium benzoate have been linked to health issues such as asthma, ADHD, and gastrointestinal disturbances. - **Hormonal Disruption**: Some preservatives may interfere with hormonal functions, potentially affecting growth and development in children. - **Allergic Reactions**: Skin rashes, respiratory issues, and other allergic responses are documented side effects of certain food additives. - **Long-term Effects**: Continuous consumption of foods with synthetic preservatives can lead to chronic health conditions, including obesity and cancer. While synthetic preservatives are effective in extending shelf life, the growing preference for natural alternatives highlights the need for safer options in food preservation. However, the debate continues regarding the balance between food safety and health risks associated with these additives.

The European Union (EU) is transitioning towards a circular economy (CE) to address environmental sustainability, resource efficiency, and economic growth. This shift is driven by the need to reduce waste, preserve natural resources, and create sustainable growth and jobs. The EU's commitment to CE is evident in its legislative actions and strategic plans, which aim to transform the current linear economic model into a more sustainable one. Below are the key reasons for this transition: ## Environmental Sustainability and Resource Efficiency - The EU's Circular Economy Package, adopted in 2015, aims to transition to a low-carbon, resource-efficient economy. This includes legislative proposals and action plans for waste management, emphasizing eco-innovation and sustainable development . - A circular economy helps maintain products, materials, and components at their highest value, reducing pressure on natural resources and addressing environmental challenges such as climate change and biodiversity loss . - The recycling of electronic products is a significant component of the EU's strategy, aiming to improve environmental sustainability through better recycling rates and resource management . ## Economic Growth and Job Creation - Transitioning to a CE is seen as a pathway to sustainable economic growth and job creation. By closing the loop in economic systems, the EU aims to promote economic growth while aligning with the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) . - The EU's CE action plan, activated in 2020, focuses on reducing food waste and improving the sustainability of the food system, which is a major resource consumer and environmental pressure point . ## Challenges and Regulatory Barriers - Despite the benefits, the transition to a CE faces challenges such as regulatory barriers, insufficient awareness, and limited infrastructure for recycling and reusing materials. Overcoming these obstacles requires comprehensive policy frameworks and collaboration between governments, industries, and consumers . While the EU's transition to a circular economy is primarily driven by environmental and economic motivations, it also faces significant challenges. Addressing these challenges requires coordinated efforts across various sectors and levels of governance to ensure the successful implementation of CE principles.

Reducing fossil fuel dependency is a critical goal for many countries aiming to mitigate climate change and transition to sustainable energy systems. Various economic policies have been implemented globally to address this issue, focusing on both the demand and supply sides of the energy market. These policies include market liberalization, carbon pricing, renewable energy incentives, and the reallocation of subsidies, among others. Below, we explore these strategies in detail. ## Market Liberalization and Renewable Energy Promotion - The European Union's liberalization of the internal energy market in 2011 is a significant policy aimed at reducing fossil fuel dependency. This policy has been effective in decreasing CO2 emissions by promoting renewable energy sources and reducing trade barriers, which facilitates the efficient use of resources. - In the Asia-Pacific region, energy policies have been designed to improve access to electricity and clean cooking, enhance energy efficiency, and increase renewable electricity capacity. Strategies, rather than laws or regulations, have been more effective in advancing these goals. ## Carbon Pricing and Supply-Side Measures - Carbon pricing is a widely recognized tool for reducing fossil fuel use by making it more expensive to emit CO2. However, supply-side measures, such as limiting fossil fuel exploration and extraction, are gaining attention as complementary strategies. These measures address the political and economic interests that perpetuate fossil fuel use. - China's environmental accountability system, which includes setting energy conservation and emission reduction (ECER) targets, has proven effective in curbing energy consumption and carbon emissions. This approach aligns economic development with low-carbon goals. ## Structural Economic Policies - Broader structural policies, such as the US Green New Deal and the European Green Deal, aim for deep decarbonization by integrating energy transition goals with broader social objectives. These policies recognize the need for a comprehensive approach that considers existing economic patterns and infrastructure legacies. - In India, building energy codes and other sectoral policies are part of the Nationally Determined Contributions to reduce emissions. These policies have the potential to significantly lower energy use and CO2 emissions in the building sector. ## Reallocation of Subsidies - The reduction or elimination of fossil fuel subsidies is a critical policy for reducing dependency on fossil fuels. However, this can lead to public unrest, as seen in countries like Egypt and Indonesia. To mitigate this, some governments have redirected these subsidies towards health services, which can provide immediate and tangible benefits to the public. ## Challenges and Unintended Consequences - Policies such as curtailment caps, intended to promote renewable energy integration, can have unintended negative effects, such as increased fossil fuel utilization and higher emissions. These outcomes highlight the complexity of designing effective energy policies. - The COVID-19 pandemic has also shown that public policies can have mixed effects on energy transitions. While lockdowns temporarily reduced emissions, they also slowed the transition to renewable energy by increasing the reliance on fossil fuels. While these policies demonstrate a range of approaches to reducing fossil fuel dependency, they also underscore the challenges and complexities involved. Effective policy design requires careful consideration of economic, social, and political factors to ensure that the transition to sustainable energy systems is both equitable and efficient.

- IRB-SBS Home

- Contact IRB-SBS

- IRB SBS Staff Directory

- IRB SBS Board Members

- About the IRB-SBS

- CITI Training

- Education Events

- Virginia IRB Consortium

- IRB-SBS Learning Shots

- HRPP Education & Training

- Student Support

- Access iProtocol

- Getting Started

- iProtocol Question Guide

- iProtocol Management

- Protocol Review Process

- Certificate of Confidentiality

- Deception and/or Withholding Information from a Participant

- Ethnographic Research

- IRB-SBS 101

- IRB-SBS Glossary

- Participant Pools

- Paying Participants

- Research in an Educational Setting

Research in an International Setting and/or Location

- Risk-Sensitive Populations

- Student Researchers and Faculty Sponsors

- Study Funding and the IRB

- Understanding Risk in Research

- Vulnerable Participants

- IRB-SBS PAM & Ed

- Federal Regulations

- Ethical Principals

- Partner Offices

- Determining Human Subjects Research

- Determining HSR or SBS

In order to review a study that is being conducted in an international setting and/or with international participants, the Board requires additional information about the study and its participants. Although we work to maintain a Board with a broad range of expertise, it is impossible to cover the diverse groups that are studied by our researchers. It is important to provide the Board with more details about the participants, appropriately identify risks to the participants, and describe how you will minimize those risks. Doing so will help the Board to accurately review your study and will demonstrate your preparedness for conducting your study. This section details specific information the Board needs to know as well as provides guidance for navigating conducting research in an international setting and/or with international participants.

The International Research Data Source question is designed to help researchers provide the Board with the information needed to assess an international study. For more information about completing this section of the protocol, see International Research Data Source . In addition, if your study will take place in the European Union or United Kingdom or uses data from citizens of those regions, your study will be subject to the GDPR. Please review the GDPR section below and access the GDPR Informed Consent Addendum to include with your consent materials.

An international setting involves any location outside of the legal jurisdiction of the United States. An international population could be a tight-knit community living within the borders of the U.S., such as the Hmong, or a broader group such as non-native Latinos. These groups generally have (though are not limited to) a distinct cultural identity that is different from mainstream American culture, speak a different language, and in some cases may not be U.S. citizens or could be undocumented.

If you are conducting a study in another country, it is important that you understand the legal implications of your study and how they might affect your participants. If you are collecting information about illegal behaviors, you need to understand what power the government has to take this information from you and use it against your participant. If this is an issue, participants need sufficient warning. In some cases, it may be necessary to waive documenting consent in order to protect a participant’s identity. Some participants may have a delicate political position because of refugee status or opposition to current political powers. It is important to understand how your involvement with the participants will affect their political standing, which can often impact personal well-being, employment status, etc. It is also important to investigate any laws that might affect how you should conduct your study. For example, in the U.S., there are specific laws governing how medical records and student records can be used by researchers. Similar laws may apply in other countries as well. As another example, the definition of a minor (i.e. child unable to legally consent) varies in different countries and even in the different U.S. states. You will be obligated to follow the local laws for the location in which you conduct your study and it is important that you are familiar with any laws that are pertinent to your study.

International participants may have different perspectives on legal documents, consent forms, etc, and may be wary of signing a consent form, whether of whether an actual risk exists. Documents like consent forms that appear to be legal in nature may be inappropriate in some cultural contexts. Although the Board has some restrictions on what it can allow, they will consider alternative consent scenarios that are culturally appropriate. For more information, see Oral Consent .

When writing your protocol, describe your procedures and then explain why they are culturally appropriate. For example, if you are using an oral consent process, explain why it is culturally appropriate for you to do so (i.e. the participants are offended when approached with a form, it is more appropriate to talk to them casually first before talking about the research process). This information will help the Board to understand the cultural environment in which you are working and will demonstrate to them that you are prepared to go forward.

In addition to understanding the local legal ramifications of your study and the cultural context, you will need to investigate the local IRB requirements. The IRB-SBS expects international participants to be treated the same as participants from the US and we review a protocol as such. However, our review does not supercede the authority of an IRB that governs an international location; depending on the circumstances of your study, you may be subject to both the UVA IRB-SBS review and a local IRB review as well. For more resources on international human subjects regulations, see International from OHRP's website (check out the Listings of Social-Behavioral Research Standards specifically).

The Board expects you to provide the participants with a consent process that is in their native language (or the language in which they usually read and converse). This includes not only providing a consent document written in the participant’s language but also providing a translator that the participant can talk to if he or she has questions if you are not able to speak the language sufficiently. The translator will be considered part of the research team and is obligated to follow the protocol for protecting confidentiality. In some situations, the Board may require a separate consent process for the translator.

In order for a participant to be informed, it is necessary that the consent process be conducted in a language the participant can understand. If you anticipate recruiting non-English speaking participants, the Board asks that you provide a version of the consent form in the language that is appropriate for the participants, as well as arrange for an individual who can talk with the participants (if you do not speak the language). The interpreter must understand confidentiality issues and should be a trusted member of the research team.

As stated in the "Legal Preparedness" section, consent forms may not be appropriate for some international settings and it may be more appropriate to use an oral consent procedure. For more information, see Oral Consent .

In the consent templates, we ask that you provide the participant with your contact information as well as the IRB-SBS contact information . Depending on your location and population, it may not be feasible or realistic for your participants to contact our IRB if they have questions. Thus it is important for you to provide a local contact who can be available to answer questions and provide support if a problem should arise. For undergraduate and graduate students, this person can be your local advisor (please note that you are required to have a local advisor when you are conducting a study abroad. Please see Student Researchers for more information). Other options may include (but are not limited to) a qualified individual in a local research facility, IRB, or hospital.

GDPR applies to select data when collected from individuals located in the European Economic Area (EEA) and/or the United Kingdom (UK). GDPR regulates the collection, use, disclosure or other processing of personal data. If you are collecting personal data in the EEA or UK, or if your participants reside in those areas, you are subject to the GDPR. If your participants are EEA or UK subjects but are outside of the EEA or UK when the data collection occurs, the data collected is not subject to the GDPR.

While many of the US federal regulations mirror the requirements in the GDPR, the GDPR requires researchers to provide additional consent form content and conduct specific processes related to data collection.

While this section and the GDPR Informed Consent Addendum provides some guidance on what is required under the GDPR, please note that individual countries may have varied interpretations, etc. It is important that you familiarize yourself with the laws and regulations of the country(ies) in which you will conduct research and seek counsel if needed. Check out this OHRP site which provides a compilation of information on the GDPR and how it is interpreted in various countries.

Regarding the underlying philosophy about consent, the US OHRP regulations regarding consent and the GDPR’s consent requirements agree that participants need to be fully informed in a non-coercive fashion.

“When asking for consent, a controller has the duty to assess whether it will meet all the requirements to obtain valid consent. If obtained in full compliance with the GDPR, consent is a tool that gives data subjects control over whether or not personal data concerning them will be processed. If not, the data subject’s control becomes illusory and consent will be an invalid basis for processing, rendering the processing activity unlawful.”

The GDPR expands on the concepts of informed consent by increasing the expectation for the information provided to participants.

“Article 4(11) of the GDPR defines consent as: “any freely given , specific , informed and unambiguous indication of the data subject's wishes by which he or she, by a statement or by a clear affirmative action, signifies agreement to the processing of personal data relating to him or her.””

Freely given

This concept mirrors our evaluation that consent must be provided in a manner and environment free from coercion, either real or perceived.

Like the US regulations require, consent must provide participants with specific and clear information how their data will be used. The GDPR requires the following regarding consent specificity:

- Purpose specification as a safeguard against function creep: expanding how the data will be used beyond what was described in the consent form after consent is collected.

- Granularity in consent requests: if a researcher collects data for various purposes, the participant should be able to opt-in for each purpose. For example, if the researcher is using an interview for a study and will also provide the interview to a library, the participant should opt in to both uses of the data.

- Clear separation of information related to obtaining consent for data processing activities from information about other matters: related to the example above, the consent should provide specific information for using the interview in the study as well as using the interview in the library.

Similar to the US regulations, participants need to be provided with consent information prior to agreeing to the study, assuring that the participant understands what they are agreeing to as well as how they can withdraw from the study.

The following are the minimum requirements for the information provided to participants in an informed consent process:

- the controller’s identity

- the purpose of each of the processing operations for which consent is sought,

- what (type of) data will be collected and used,

- the existence of the right to withdraw consent

- information about the use of the data for automated decision-making in accordance with Article 22 (2)(c)34 where relevant

- on the possible risks of data transfers due to absence

All of the above items are part of our consent templates and are further outlined in the GDPR Informed Consent Addendum . As required by our consent process, the information provided must be clear and easy to understand by the participants and is appropriate for the participants (i.e. if the participants are minors, the text is written to the appropriate reading levels). In addition, it is important that the consent be separate and distinct from the data collection. For example, the consent form is provided as a separate paper from the rest of the paper materials provided to participants, or in the case of an online survey, the consent is a distinct page or site and doesn’t look like part of the data collection activity.

Unambiguous indication of subject’s wishes

It must be clear that consent is provided in an intentional act through an active motion or declaration. Consent can be collected through written or oral statement that can be documented electronically. Opt-out options or pre-ticked boxes are not legal: “Silence or inactivity on the part of the data subject, as well as merely proceeding with a service cannot be regarded as an active indication of choice.”

Documentation of Consent:

The GDPR allows for flexibility in how consent is documented, allowing for electronic consent, oral consent, written consent, etc.

“It is up to the controller to prove that valid consent was obtained from the data subject. The GDPR does not prescribe exactly how this must be done. However, the controller must be able to prove that a data subject in a given case has consented . As long as a data processing activity in question lasts, the obligation to demonstrate consent exists. After the processing activity ends, proof of consent should be kept no longer then strictly necessary for compliance with a legal obligation or for the establishment, exercise or defence of legal claims, in accordance with Article 17(3)(b) and (e).”

Consent Withdrawal:

The GDPR pays particular attention to consent withdrawal and expects the process to be equal to obtaining consent in regards to ease. For example, if obtaining consent is a simple “I accept” button but requesting a withdrawal involves a phone call to an international number, the withdrawal process is more complicated and does not equal the obtaining consent process. Rather, participants need to be provided with a simple “I withdraw” option as well.

Regarding scientific research, there is some flexibility as the GDPR recognizes that researchers don’t always know the precise way in which the data will be used, but the expectation for providing specific information is still there.

“Recital 33 seems to bring some flexibility to the degree of specification and granularity of consent in the context of scientific research. Recital 33 states: “It is often not possible to fully identify the purpose of personal data processing for scientific research purposes at the time of data collection. Therefore, data subjects should be allowed to give their consent to certain areas of scientific research when in keeping with recognised ethical standards for scientific research. Data subjects should have the opportunity to give their consent only to certain areas of research or parts of research projects to the extent allowed by the intended purpose.” First, it should be noted that Recital 33 does not disapply the obligations with regard to the requirement of specific consent. This means that, in principle, scientific research projects can only include personal data on the basis of consent if they have a well-described purpose . For the cases where purposes for data processing within a scientific research project cannot be specified at the outset, Recital 33 allows as an exception that the purpose may be described at a more general level.”

- International Research Data Source

- Understanding Risks in Research Studies

- Responsibilities of Researchers

- Oral Consent

- Student Researchers

- Consent Templates

- International (OHRP)

- Listings of Social-Behavioral Research Standards (OHRP)

- Compilation of European GDPR Guidances (OHRP)

GDPR Reference:

Article 29 Working Party Guidelines on consent under Regulation 2016/679 Adopted on 28 November 2017 As last Revised and Adopted on 10 April 2018

Internationalists and locals: international research collaboration in a resource-poor system

- Open access

- Published: 28 April 2020

- Volume 124 , pages 57–105, ( 2020 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Marek Kwiek ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-7953-1063 1

12k Accesses

60 Citations

33 Altmetric

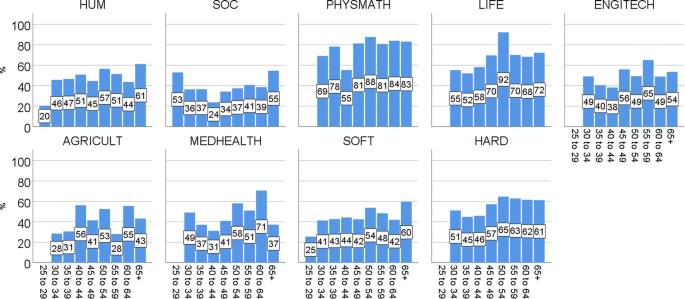

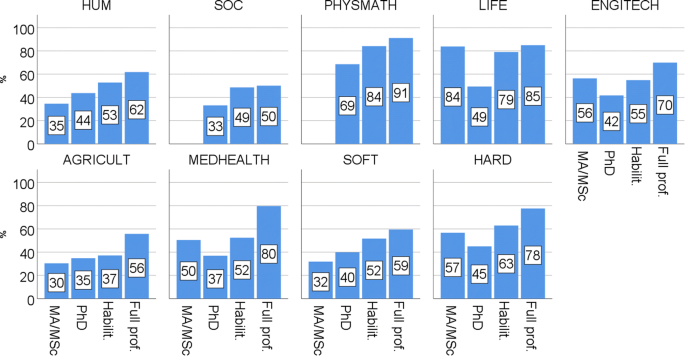

Explore all metrics

The principal distinction drawn in this study is between research “internationalists” and “locals.” The former are scientists involved in international research collaboration while the latter group are not. These two distinct types of scientist compete for academic prestige, research funding, and international recognition. International research collaboration proves to be a powerful stratifying force. As a clearly defined subgroup, internationalists are a different academic species, accounting for 51.4% of Polish scientists; predominantly male and older, they have longer academic experience and higher academic degrees and occupy higher academic positions. Across all academic clusters, internationalists consistently produce more than 90% of internationally co-authored publications, representing 2320% of locals’ productivity for peer-reviewed articles and 1600% for peer-reviewed article equivalents. Internationalists tend to spend less time than locals on teaching-related activities, more time on research, and more time on administrative duties. Based on a large-scale academic survey ( N = 3704), some new predictors of international research collaboration were identified by multivariate analyses. The findings have global policy implications for resource-poor science systems “playing catch-up” in terms of academic careers, productivity patterns, and research internationalization policies.

Similar content being viewed by others

The Internationalization of Research

International Research Collaboration Practices and Outcomes: A Comparative Analysis of Academics’ International Research Activities

An empirical analysis of individual and collective determinants of international research collaboration

Explore related subjects.

- Medical Ethics

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The principal distinction drawn here is between research “internationalists” and “locals.” The former are scientists involved in international research collaboration while the latter group are not. These two distinct types compete for academic prestige and professional recognition (Wagner and Leydesdorff 2005 ), research funding (Jeong et al. 2014 ), and international scientific recognition (Merton 1973 ). While locals produce knowledge for “national research markets” and audiences (Ziman 1991 ), internationalists produce knowledge for international (or local and international) markets and audiences. As reward systems operate differently across countries and academic disciplines, seeking international recognition rather than national recognition is reported to be more or less “necessary” (Kyvik and Larsen 1997 : 260), depending on country affiliation and discipline.

Academic discipline, employing institution and type, and national reward structure all influence international research collaboration. However, the decision to internationalize is ultimately personal, and concepts such as “self-organization” (Wagner and Leydesdorff 2005 : 1610; Melin 2000 : 39; Wagner 2018 : 84) and “informal collaboration” beyond formal agreements (Georghiou 1998 : 612) are especially relevant in this regard. Within the global knowledge network, the motivation to internationalize comes from scientists themselves, and “political ties or national prestige do not motivate the alliances of researchers” (Wagner 2018 : viii). Faculty internationalization is reported to be disproportionately shaped by deeply ingrained individual values and predilections (Finkelstein, Walker, and Chen 2013 ), and scientists vary in their tendency to collaborate internationally: “The more elite the scientist, the more likely it is that he or she will be an active member of the global invisible college” (Wagner 2008 : 15)—that is, the more likely they are to collaborate with colleagues in other countries (Kwiek 2016 ).

Previous studies have shown that the share of internationalists among Polish academics is substantially lower than the Western European average, and their role in Polish academic knowledge production is substantially higher (Kwiek 2015a ). In Europe, Poland is among those countries with the lowest share of internationalists. In a recent study of 11 countries, the mean share of internationalists among European scientists employed full-time in the university sector was 63.8% (Kwiek 2018b ); in Poland, internationalists account for just 51.4%. As measured by a proxy of internationally co-authored publications, Poland had the lowest level of research internationalization in the European Union in 2018 (35.8% based on Scopus data). There are many underlying reasons, but in general terms, this relates to the systematic “deinstitutionalization” of Polish universities’ research mission since about 2010, followed by a slow “reinstitutionalization” powered by two waves of higher education reforms in the last decade (for overviews of the Polish higher education and science systems, see Antonowicz 2016 ; Antonowicz et al. 2017 ; Dakowska 2015 ; Urbanek 2018 ; Bieliński and Tomczyńska 2018 ; Ostrowicka and Stankiewicz 2018 ; Wolszczak-Derlacz and Parteka 2010 ). To increase the international visibility of Polish science, current reforms (under “Law 2.0”) include new funding formulas, a revised research assessment exercise (expected in 2021), and the selection in 2019 of ten “research universities” for additional funding in 2020–2026 within a new “national excellence initiative.” In practice, as in all science systems “playing catch-up,” the direction of change is clear: to increase publication in international journals and the number of internationally co-authored publications.

Certain scientists are clearly more internationalized than others, and this distinction permeates Polish research. As more international collaboration tends to mean higher publishing rates (and higher citation rates), internationalization plays an increasingly stratifying role within the academic profession., Increasingly, those who do not collaborate internationally are likely to suffer internationalization accumulative disadvantage in terms of resources and prestige. (The term “accumulative disadvantage” was originally used by Cole and Cole 1973 : 146). Research internationalization divides the academic community, both across institutions (vertical differentiation) and across faculties within institutions (horizontal segmentation), and highly internationalized institutions, faculties, research groups and individual scientists and less internationalized counterparts emerge. For internationalists, the key reference group is the international academic community; in contrast, locals focus predominantly on the national academic community.

The present study addresses the following research questions. What distinguishes research internationalists from research locals? Are internationalists distinctive in terms of who they are, how they work, or what they think about their academic work? In short, are internationalists a different species within the resource-poor Polish higher education system?

Based on a large-scale academic survey ( N = 3704 returned questionnaires), this study has global implications for academic career and productivity patterns and contributes to a better understanding of “the collaborative era in science” (Wagner 2018 ) by contrasting the prototypical figure of the internationalist with the local research scientist.

The paper is structured as follows. The next section describes the theoretical framework, followed by data and methods. The results section includes an overview of internationalists, patterns of individual research productivity and international collaboration, patterns of individual research productivity by publication type, a bivariate analysis of working time distribution and teaching and research role, and a multivariate analysis. The logistic regression analysis is in two parts; model approach (I) examines predictors of collaboration with international colleagues in research, and model approach (II) looks at how various aspects of internationalization influence research productivity. The paper ends with a summary of the findings, followed by discussion and conclusions.

Theoretical framework

Studying international research collaboration.

Before moving to more specialized literature, let us briefly describe what is often assumed in international collaboration studies. First, impediments to international research collaboration may include macro-level factors (geopolitics, history, language, cultural traditions, country size, country wealth, geographical distance); organizational factors (reputation, resources); and individual factors (predilections, attractiveness as a researcher in terms of possible input and expertise etc.) (Hoekman et al. 2010 ; Luukkonen et al. 1992 ).

Second, international research collaboration is reported to have costs as well as benefits (Katz and Martin 1997 ; Jeong et al. 2014 ). According to Katz and Martin, “With more people and perhaps several institutions involved, greater effort is required to manage the research” ( 1997 : 16). Specifically, transaction costs (Georghiou 1998 ) and coordination costs (Cummings and Kiesler 2007 ) are higher for international research collaboration. In collaborative research, there is a trade-off between increased publication and research funds and the need to minimize transaction costs (Landry and Amara 1998 ). Collaboration involving multiple universities also complicates coordination and may undermine project outcomes (Cummings and Kiesler 2007 ). Furthermore, while research collaboration with highly productive scientists generally increases individual productivity, collaboration with low-productivity scientists is reported to have the opposite effect (Lee and Bozeman 2005 ).

Third, international research collaboration can be viewed as an emergent, self-organizing, networked system, in which the selection of partners and research settings often relies on the researchers themselves. In more spontaneous or bottom-up collaborations, what matters is “the individual interests of researchers seeking resources and reputation” (Wagner and Leydesdorff 2005 : 1616). Most research collaborations begin with face-to-face meetings, especially at conferences (Melin 2000 ). Scientists connect with each other “on a peer-to-peer level, and a process of preferential attachment selects specific individuals into an increasingly elite circle. The process reduces free riders and greatly increases the visibility of parts of the system” (Wagner 2018 : x).

Fourth, according to resource allocation theory, the attentional resources that scientists and their teams can invest in research (commitment and time) are always limited. This theory holds that “the resources allocated to a function will decrease as resources allocated to other functions increase” (Jeong, Choi, and Kim 2014 : 523). Consequently, the decision to engage in research teamwork “is ultimately a resource allocation decision by which members must decide how to best allocate their limited resources” (Porter et al. 2010 : 241), as time is often a more valuable resource than research funding (Katz and Martin 1997 ). Additional demands can reduce the available time and energy for actual research activities (Jeong et al. 2011 ). Collaboration also involves personal decisions based on “trust” and “confidence” (Knorr Cetina 1999 ), as well as “purpose”, involving multiple issues that range from “access to expertise” to “enhancing productivity” (Beaver 2001 : 373).

Fifth, collaboration is largely a matter of social convention among scientists and therefore difficult to define; what constitutes a collaboration varies across levels (individuals, institutions) and changes over time (Katz and Martin 1997 ). Beyond the “sole research” mode, it is important to distinguish clearly between “internal” collaboration (within the same organization), “domestic” collaboration (within the same country), and “international” collaboration (between countries) (Jeong et al. 2011 : 969). In general, research collaboration can be defined as a “system of research activities by several actors related in a functional way and coordinated to attain a research goal corresponding with these actors’ research goals or interests” (Laudel 2002 : 5). In other words, collaboration presupposes a shared research goal, is defined by activities rather than by the actors involved, and refers only to research that includes personal interactions. By this definition, collaboration need not have any publication objective at any point (Sooryamoorthy 2014 ). However, as broader notions of collaboration are not easy to measure, many studies of research collaboration “begin and end with the co-authored publication” (Bozeman and Boardman 2014 : 2–3).

Finally, international research collaboration can be said to have two prerequisites: the researcher’s motivation and their attractiveness (as a researcher) to international colleagues (Kyvik and Larsen 1994 ; Wagner 2008 ). The potential to join international research networks depends on one’s attractiveness as a research partner (Wagner and Leydesdorff 2005 ). In this regard, “Visibility is a basic condition for being potentially interesting to other scientists, but one also has to be attractive in order to be actively sought out by others” (Kyvik and Larsen 1994 : 163). Also availability of resources increases the level of international research collaboration (Kyvik and Larsen 1997 ; Jeong et al. 2014 ). Beyond that, scientists create and sustain the connections that form the global knowledge network largely because they “become resources to others … connections are retained as long as they are of mutual (or potential) interest to participating members” (Wagner 2018 : 62). In short, networks mean (international) collaboration.

International research collaboration and reward structures in science

Gouldner ( 1957 ) distinguished between scientists who are less research-oriented and more loyal to their employing organization ( locals ) and those who are less loyal to their organization and more research-oriented ( cosmopolitans ). These pure types have subsequently been reformulated in both organizational studies and higher education research (Rhoades et al. 2008 ; Smeby and Gornitzka 2008 ). According to Robert K. Merton’s sociology of science ( 1973 : 374), outstanding scientists are more likely to be “cosmopolitans” who are oriented to wider “national and trans-national environments” while “locals” tend to be oriented “primarily to their immediate band of associates” or local peers.

Centering on the concept of “mobility,” the distinction originally referred to organizational roles and to professional identities and norms rather than research internationalization. Gouldner argued that professionals identify with a reference group and refer to it in making judgments about their own performance. Distinguishing immobile and institution-oriented scientists (loyal to inside reference groups) from mobile, cosmopolitan, career-oriented scientists (loyal to outside reference groups), cosmopolitans and locals can be said to differ sharply in their attitude to research, sources of recognition, and academic career trajectories (Wagner and Leydesdorff 2005 ). In their study of Norwegian scientists, Kyvik and Larsen related the local/cosmopolitan opposition to publishing modes rather than to international collaboration: “while locals can be said to have the Norwegian scholarly community as a frame of reference, cosmopolitans take the values and standards of the international scientific community as a comparative frame of reference” ( 1997 : 261).

As incentive and reward systems in European science evolve to become more output-oriented (Kyvik and Aksnes 2015 ; Kwiek 2019 ), individual scientists are under increasing pressure to become internationalists by cooperating and co-publishing internationally. Performance-based funding and awareness of international research-based university rankings mean that scholarly publishing is closely linked to institutional and/or departmental funding, and collaboration is increasing at author, institution, and country levels (Gazni et al. 2012 ). The Mertonian principle of priority of discovery suggests that international research collaboration is driven primarily by reward structures in highly competitive science systems, especially in the hard sciences (Kyvik and Larsen 1997 ). As Wagner and Leydesdorff have argued, “the many individual choices of scientists to collaborate may be motivated by reward structures within science where co-authorships, citations and other forms of professional recognition lead to additional work and reputation in a virtuous circle” (Wagner and Leydesdorff 2005 : 1616).

Massive international research collaboration can be understood as an emergent, self-organizing, networked system, in which partners and research settings are often selected by the researchers themselves (Wagner 2018 ). With changing reward structures and the new opportunities afforded by information and communication technologies, individual scientists increasingly cooperate internationally in what can be described as a process of “preferential attachment,” as certain individuals are admitted to an increasingly elite circle (Wagner 2018 : x). The omnipresence of internationalists changes how science is perceived, and non-collaboration is increasingly rare, even in the traditionally sole-authored humanities. In that context, Poland is an interesting outlier, with the lowest share of internationally co-authored publications in Europe (Kwiek 2020 ; Scopus 2020 ) and one of the lowest shares of scientists reporting international collaboration in Europe.

Survey-based and bibliometric studies

While the two contrasted prototypical figures of internationalists and locals in research were not used in previous research, the vast literature on international collaboration in research was instrumental in developing the hypotheses, using bibliometric and survey-based studies of international collaboration in research. For example, Kwiek ( 2015a ) looked at internationalists and locals in 11 European systems. Rostan et al. ( 2014 ) and Finkelstein and Sethi ( 2014 ) analyzed internationally collaborating and non-collaborating scholars in 19 countries, and Cummings and Finkelstein ( 2012 ) contrasted a minority of “internationalists” with their “insular peers” in the USA. All four studies were based on survey data juxtaposing collaborating and non-collaborating scientists. Two large-scale international comparative studies of the changing academic profession (CAP and EUROAC; see subsection on the dataset below), published successively in the last 10 years provide useful data. In contrast to the present case, most bibliometric studies refer to international research collaboration defined as production of internationally co-authored publications rather than as research conducted with international collaborators. Nevertheless, both survey and bibliometric approaches contributed to the development of our hypotheses, as they are closely linked and examine related phenomena.

International research collaboration and gender

Beyond the numerous studies on general research collaboration and gender, several survey-based studies have focused specifically on the role of gender in international research collaboration. In most cases, the findings indicate that being female is a negative predictor of international research collaboration (Rostan et al. 2014 ; Vabø et al. 2014 ; Kwiek 2018a ). To cite one survey-based global study, “the prototypical academic figure in international research collaboration is a man, in his mid 50s or younger, working as a professor in a field of the natural sciences at a university” (Rostan et al. 2014 : 130).

In their study of gender and international collaboration, Vabø et al. ( 2014 : 191) found that female scientists report lower international research collaboration than males, regardless of the intensity of international collaboration within the regions studied. While male scientists are generally more involved in international research collaboration, female academics tend to be more involved in internationalization at home—for instance, teaching in a foreign language (Vabø et al. 2014 : 202).

Being male significantly increases the odds of involvement in international research collaboration (by 69%) in 11 European countries (see Kwiek 2018a ). In Fox et al. ( 2017 : 1304), women engineers identified funding and finding collaborators as external barriers to internationalization while personal or family concerns were perceived as significantly less important barriers for themselves than for others. Although in the 2000s, the success rate of research grant applications for female scientists in Poland has been lower than for male scientists, recent data indicate that the trend is reversing, especially for younger generations (Siemieńska 2019 ). For an account of how science globalization perpetuates gender inequalities and disadvantages women scientists, see Zippel ( 2017 ). For an account of internationalization (and especially international mobility) as “indirect discrimination” against women scientists, see Ackers ( 2008 ).

Bibliometric research on gender disparity in international collaboration has been conducted in Norway and Italy. The general conclusion was that the propensity to collaborate internationally in research was similar for both male and female scientists (Norway) or higher for male scientists across the whole population but similar for male and female top performers (Italy). Successive studies have addressed the gap in research on gender differences in research collaboration in general, and international research collaboration in particular, by taking the individual scientist as the base unit of analysis for both whole populations and top performers at national level. In the case of all Italian scientists, Abramo et al. ( 2013 ) showed that women scientists are more likely to collaborate domestically both intramurally and extramurally but are less likely to engage in extramural international collaboration. The study methodology avoids distortion by outliers—that is, by cases of highly productive and highly internationalized scientists whose extensive publications distort aggregate index values (Abramo et al. 2013 : 820; similar gender disparities in international research collaboration were shown in a study of 25,000 university professors in Poland in Kwiek and Roszka 2020 ).