An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Literature review on income inequality and economic growth

This paper provides a comprehensive literature review of the relationship between income inequality and economic growth. In the theoretical literature, we identified various models in which income inequality is linked to economic growth. They include (i) The level of economic development, (ii) The level of technological development, (iii) Social-political unrest, (iv) The savings rate, (v) The imperfection of credit markets, (vi) The political economy, (vii) Institutions and (viii) The fertility rate. Based on the transmission mechanisms of these models, we found that the relationship between income inequality and growth can be negative, positive or inconclusive. The first three models demonstrate that the relationship is inconclusive, the fourth shows that it is positive, while the remainder indicate that the relationship should be negative. In the face of theoretical ambiguity, we also noted that the empirical findings on the relationship between income inequality and growth are highly debatable. These findings can be broadly classified into four categories, namely negative, positive, inconclusive and no relationship. Based on these findings, we provide a critical survey on methodology issues employed in the prior studies and propose a better methodology to researchers for future studies.

- • Theoretical and empirical literature is reviewed and synthesis is done to understand the income inequality-growth nexus

Graphical Abstract

Specification table

Across countries, the unequal distribution of income and resources among the population is the defining challenge of our time. In both developed and developing economies, the income inequality gap (as measured by the decile ratios and the Gini coefficient based on the Lorenz curve) between rich and poor is at high levels, and continues to rise [24] . When income inequality becomes extremely high, it fuels social dissatisfaction and raises the threat of social and political unrest [13] . In similar vein, Alesina and Perotti [8] :1 argue that high income inequality, “ by increasing the probability of coups, revolutions, mass violence or, more generally, by increasing policy uncertainty and threatening property rights, has a negative effect on investment and, as a consequence, reduces growth ”.

Given the already high level of income inequality and rising trends in many countries, along with the potentially negative consequences for economies, we found that a significant body of literature examines the causes of income inequality and its consequences for economic development. Among them were theoretical analyses of the inequality–growth nexus, which identified various transmission mechanisms linking income inequality to economic growth. These include (i) The level of economic development, (ii) The level of technological development, (iii) Social-political unrest, (iv) The savings rate, (v) The imperfection of credit markets, (vi) The political economy, (vii) Institutions and (viii) The fertility rate. Based on these models, we found that the relationship between income inequality and growth can be negative, positive or inconclusive. Theories on the level of economic development (see [7 , 31 , 38 , 54] ) and technological development (see [6 , 29 , 33] ) demonstrate that the relationship between inequality and growth changes from positive to negative as the level of development increases. Inconclusive results are also echoed by the social-political unrest model, which argues that the socio-political unrest stemming from high income inequality can either inhibit or benefit growth (see [13 , 14 , 56 , 62] ). In addition, theories on the political economy (see [9 , 11 , 13 , 46 , 48 , 50] ), the imperfection of credit markets (see [5 , 12 , 30 , 51] ; Panniza, [46] ), institutions (see [22 , 34 , 61] ) and the fertility rate (see [26] ) demonstrate that income inequality is negatively related to growth. The only theory which supports the positive relationship between income inequality and growth is the theory on the savings rate (see [3 , 17 , 42 , 53] ).

Given such theoretical ambiguity, it is little wonder that the empirical findings on the relationship between income inequality and growth are strongly debated. Early empirical studies by Alesina and Rodrik [9] , Persson and Tabellini [50] and Perotti [49] reported that inequality exerted a negative impact on growth. That negative relationship has been confirmed by numerous subsequent studies (see, for example, Panniza, [18 , 19 , 46 , 55 , 64] ). Evidence of a negative relationship has, however, been challenged by studies which reported positive results on the inequality–growth nexus (see, for example, [28 , 39 , 57 , 58] ). In addition, several studies have yielded inconclusive findings, with most reporting that the relationship is positive in high-income and negative in low-income countries (see, for example, [13 , 20 , 25 , 27] ). A few studies found no relationship between inequality and growth (see [15 , 44] ).

Given the above background, the aim here is to provide a comprehensive literature review of the relationship between income inequality and economic growth, both in theory and empirically. While Section 2 critically analyses the theoretical framework of the income inequality–growth nexus, Section 3 reviews empirical studies on this relationship. Section 4 provides a critical survey on methodology issues employed in the prior studies and proposes a better methodology that can help reconcile the literature. Section 5 concludes the study.

Income inequality and economic growth: Theoretical framework

A theoretical analysis of the inequality–growth nexus has identified various transmission mechanisms in which income inequality is linked to economic growth. These mechanisms are discussed in detail in this section.

The level of economic development

Early researchers explored the link between income inequality and growth through the lens of the developmental stage of the economy. Kuznets [38] documented that the relationship between the two variables relies on the level of economic development of a country, meaning there is a differential relationship between income inequality and growth, with a positive relationship during the early stage of economic development and a negative relationship during the mature stage. This may be attributed to shifts of labor, from one sector to other, developed sectors. For example, when labor moves from the agricultural sector to other sectors of the economy, the per capita income of those individuals increases, as their skills are in demand in those sectors. Individuals who remain in the agricultural sector keep earning a low income, thus income inequality increases during this stage. As the economy develops, with labour continuing to move from agriculture to other sectors, individuals who remain in the agricultural sector will earn higher incomes due to the low supply of labour in that sector. Income inequality thus declines during this stage. Kuznets [38] describes the relationship as an inverted U-hypothesis, which advocates that inequality tends to increase during early stages of economic development and decrease during later stages. This argument is supported by Ahluwalia [7] , Robinson [54] and Gupta and Singh [31] .

The level of technological development

In addition to sectoral change, Galor and Tsiddon [29] , Helpman [33] and Aghion et al. [6] explored the link by connecting income inequality to the developmental stage of technology. During the early stages of technological development, innovative ideas in the economic sector result in increases in income inequality. This is due to the fact that new technology requires highly skilled labor and training, which raises wages in these sectors compared to those sectors which use old technology. As a result, employees in the new sector earn high per-capita incomes, while those working in the sector with old machines continue earning lower incomes. Therefore, income inequality increases during the early stages of technological improvements. However, as the economy moves to the more mature stage of technological development, income inequality decreases, the reason being that as more labour shifts to the sector using new technology, the incomes of those who remained in the sector with old technology also increase due to the low supply in labor in that sector. Therefore, the wage differential gap between them declines, leading to a decrease in income inequality.

The role of technology was probed further by researchers who focused on the Fourth Industrial Revolution (4IR). By implementing modern technologies, 4IR will lead to the continuing automation of traditional manufacturing and industrial processes. As Krueger [37] documented, improvements in technology widen the income inequality gap in the labor market between skilled and lowly skilled labour, because the income of highly skilled labor increases (as those individuals are in demand), while lowly skilled laborers continue earning low incomes. In similar vein, 4IR is skills-biased, which leads to a widening of the income inequality gap [1] . Based on this argument, technological improvements can be harmful to growth, due to concerns about growing inequality and unemployment.

Social-political unrest

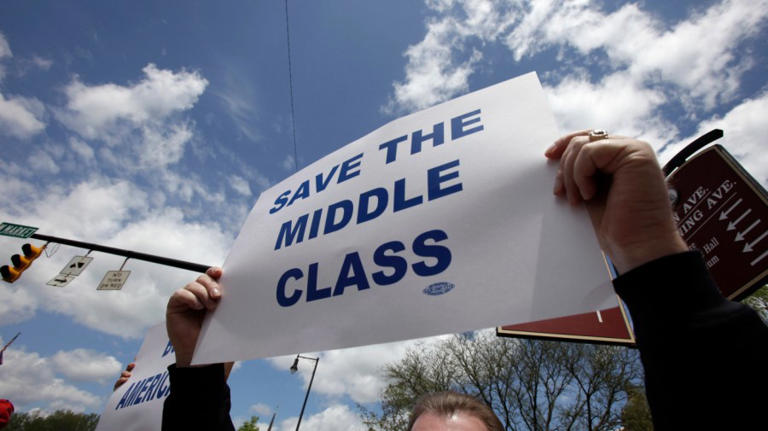

Some studies argue that the rise of socio-political unrest, stemming from high income inequality, may dampen growth (see [13 , 14 , 62] ). In countries with extreme wealth and income inequality, there are high levels of social unrest that cause people to engage in strikes, criminality and other unproductive activities. This often results in wastage of government resources and disruptions that threaten the political stability of the country. It causes uncertainty in government and slows down productivity in the economy, while discouraging investment.

By contrast, high income inequality due to the rise of socio-political unrest can promote growth. To reduce the number of strikes, criminal activity, uncertainty and political unrest, politicians and leaders favor redistribution – from the rich to the poor – in the form of a transfer of payments. In turn, this creates a safety net for the population and government to restore society's trust in government. As a result, levels of uncertainty decline and investment increases, prompting an increase in the growth rate in the long run [13 , 14 , 62] . Similarly, Saint-Paul and Verdier [56] demonstrate that, in the presence of high income inequality, the median voter favors a transfer of payments by means of public expenditure, such as financing education. This, in turn, increases human capital for the poor to access education, thereby promoting growth.

The political economy

Political economy models demonstrate that high income inequality may hinder growth (see [9 , 13 , 48] ). The law and government play crucial roles in the economy, with government in charge of the redistribution of income and resources among the population. These models reveal that when the mean income is greater than that of the median voter, people support the redistribution of income and resources (from the rich to the poor). Redistribution takes place through a transfer of payments and public expenditure, such as the establishment of health facilities and the building of schools, among others. This kind of redistribution reduces growth in the long run, however, by discouraging innovation and investment, and causing low productivity [9 , 13 , 48] . In addition, when there is high income inequality, the population demands equal distribution. That sometimes results in riots and other unproductive activities which retard economic growth. Furthermore, factors such as lobbying and rent-seeking, which often occur during the political process, also discourage growth. This happens when those in the upper decile of income distribution prevent the redistribution of income and resources to the poor, resulting in a wastage of government funds and corruption, both of which hamper economic growth in the long run [11 , 46 , 48 , 50] .

The imperfection of credit markets

The imperfect credit markets model demonstrates that income inequality is negatively associated with growth through credit markets (see [4 , 12 , 30 , 51] ; Panniza, [46] ). In an imperfect credit market, a high degree of income inequality limits the poor from accessing credit. Asymmetric information – where the lender and borrower have limited information about each other – inhibits the ability to make well-informed decisions. This limits the ability to borrow and returns on investment. In addition, imperfect laws make it difficult for creditors to collect defaulted loans, because the law might protect the assets of the borrower from being repossessed as collateral. Such laws constrain the collection of debt, leading to the hard terms and conditions faced by potential creditors. This prohibits access to credit for some individuals, in particular the poor. Given that investment depends on how much income and how many assets an individual has, the poor (who only have income for basic necessities) are unable to afford investment opportunities with high returns (for instance, to invest in human capital or property, among others). For this reason, extremely high income inequality reduces investment opportunities, leading to declining growth in the long run.

Existing studies report that income inequality exerts a positive impact on economic growth through savings rates (see [3 , 13 , 17] ). According to these studies, savings are a function of income. As income earned increases, so the savings rate rises, and vice versa. In the presence of high income inequality, rich people earn high incomes which help them to save more, because their marginal propensity to save is relatively high. This increases the aggregate savings, leading to a rise in capital accumulation, thereby enhancing economic growth in the long run (see [3] , [17] , [42] , [53] , [66] ). Following on this argument, Shin [59] demonstrates that the redistribution of income and resources from rich to poor is harmful to growth. Such action reduces the income, wealth and other resources of the rich, leading to a decline in the marginal propensity to save. As a result, aggregate savings and investments decline.

Institutions

Several studies illustrate that income inequality inhibits growth through institutions (see [22 , 34 , 61] ). Institutions play a vital role in the wellbeing of a country, because they are the key drivers of economic growth and development in the long run [2 , 60 , 65] . The quality of institutions is important for distribution and growth outcomes. High income inequality creates fertile ground for bad institutions, and exacerbates inequality and inefficiency, which leads to low growth rates in the long run. In the case of high income inequality, political decisions tend to be biased towards enriching the already rich minority, at the expense of the poor. This results in poor policies, leading to a high level of inefficiency, wastage of state resources, social dissatisfaction and political instability. It further perpetuates inequality and inhibits growth in the long run [34 , 61] . Based on this argument, bad institutions tend to associate with extreme records of inequality, inefficiency and sluggish growth. By contrast, good institutions tend to associate with low inequality, productivity and economic growth.

The fertility rate

Income inequality has been found to negatively affect growth through differences in fertility (see [26] ). This study documented that a widening income inequality gap raises differences in fertility between the rich and the poor in a population. The low-income group usually have many children, and tend to invest less in their children's education due to a lack of financial resources. By contrast, those in the high-income group usually have fewer children and invest more in their education. Therefore, in the case of extreme income inequality, the high fertility differential has a negative impact on human capital, leading to a decline in economic growth.

Income inequality and economic growth: Empirical evidence

Given such theoretical ambiguity, the empirical findings on the relationship between income inequality and growth are also highly debatable. These findings can broadly be classified into four categories, namely negative, positive, inconclusive and no relationship.

Studies with negative results on the relationship between income inequality and economic growth

The earliest empirical studies examining the inequality–growth nexus were conducted in the 1990s, and employed the ordinary least squares (OLS) and two-stage least squares (2SLS) estimation techniques (see [9 , 49 , 50] ). Alesina and Rodrik [9] examined the relationship between distributive politics and economic growth in 46 countries, for the period 1960–1985. They found that higher income inequality was accompanied by low growth. Similarly, Persson and Tabellini [50] examined the impact of inequality on growth in 56 countries, for the period 1960–1985, and found that inequality exerted a negative impact on growth. Using similar estimating techniques, Perotti [49] analysed the relationship between income distribution, democratic institutions and growth in 67 countries, and found that countries with a low level of inequality tended to have high investments in human capital, which then led to economic growth.

Studies in the 2000s developed different estimation techniques to solve the problem at hand. For example, Panizza [46] employed the standard fixed effect (FE) and generalised method of moments (GMM) to reassess the relationship between income inequality and economic growth in the United States for the period 1940–1980. The results of that study documented that income inequality negatively affected economic growth. Another single-country study was conducted on China, where Wan et al. [64] investigated the short- and long-run relationship between inequality and economic growth during the period 1987–2001. By using three-stage least squares, they found that the relationship was nonlinear and negative for China. Recently, Iyke and Ho [35] studied income inequality and growth in Italy, from 1967–2012, using the autoregressive distributed lag (ARDL) estimation technique. Their study found that income inequality affected growth both in the short and long run. That is, income inequality slowed down growth in the country.

In multiple-country studies, Knowles [36] re-examined the relationship between inequality and growth in 40 countries using comparable data and OLS from 1960–1990. That investigation found a negative relationship between inequality and economic growth for the full sample. When the countries were divided according to the income level, he found a significant negative relationship in the low-income countries but an insignificant relationship in high- and middle-income countries. Malinen [41] investigated a sample comprising 60 countries (developed and developing economies) using the Gini index as a measure of income inequality. Panel cointegration methods were used, employing panel dynamic OLS and panel dynamic seemingly unrelated regression (SUR) to analyze the steady state correlation between income inequality and economic development. During the period under study, the findings revealed a negative steady-state correlation between income distribution and economic development. In addition, in developed countries, income inequality was associated with low economic growth in the long run. Another study focused on developed countries: Cingano [23] , for instance, examined the impact of income inequality and economic growth in OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) countries between 1980 and 2012. Employed GMM, the researcher found that in those countries income inequality negatively affected economic growth. Furthermore, the study confirmed human capital as the transmission channel through which income inequality affects growth. Research by Braun et al. [18] , tested the main prediction of their model with respect to the impact of income inequality on growth at different levels of financial development. By using pooled OLS, dynamic panel and instrumental variables (IV) estimations on 150 countries during the period between 1978 and 2012, they found that greater income inequality is associated with lower economic growth. In addition, they also found that such an effect is significantly attenuated when the level of financial development increases in economies. Another study by Royuela et al. [55] tested the income inequality-growth nexus for over 200 comparable regions in 15 OECD countries during 2003–2013. By using the similar estimation techniques of Bruan et al. [18] , they showed a general negative association between inequality and growth in OECD regions. Recently, Breunig and Majeed [19] re-investigated the impact of inequality and economic growth in 152 countries. The study used GMM for the period 1956 to 2011 and found that inequality had a negative effect on growth. They further found that when both poverty and inequality were considered, the negative impact of inequality on growth was concentrated on countries with high rates of poverty.

Studies with positive results on the relationship between income inequality and economic growth

A study which found a positive relationship is that of Partridge [47] , who investigated whether inequality benefited or hindered growth in the United States between 1960 and 1990. That study, which employed OLS, yielded the following results: first, during the period of the study, a positive relationship was found between inequality and economic growth. That is, American states with high inequality grew faster. Second, the study reported that the wellbeing of the median voter had a positive impact on growth. This implies that the unequal distribution of income and resources among the population encouraged economic activity and, in turn, grew the economy. In another single-country study, Rangel et al. [52] focused on growth and income inequality by investigating the linear correlation and inverted-U shape hypothesis in Brazil, from 1991–2000. They found that, in the long run, income inequality and growth tended to move together. The results also confirmed the existence of the inverted-U hypothesis between income inequality and economic growth.

Bhorat and Van der Westhuizen [16] investigated the relationship between economic growth, poverty and inequality in South Africa, for the period 1995–2005. The study employed a distribution-neutral measure, poverty inequality elasticity estimates, and the marginal proportional rate of substitution. During the period under study, the researchers found a shift in the distribution of income and resources during periods of growth, and hence income inequality tended to increase with increases in economic growth. Later, Shahbaz [58] and Majeed [40] both employed the ARDL technique to study the income inequality–growth nexus in Pakistan, with the first investigation spanning the years 1971–2005, and the second, 1975–2013. Both studies identified a positive correlation between income inequality and economic growth in Pakistan during the period under investigation. Majeed [40] further argued that because the poor population did not participate in the growth process, growth became unsustainable.

Studies on multiple countries also reported positive results. For example, Li and Zou [39] re-examined the relation between inequality and growth from 1947–1994 for a group of developed and developing countries. Using FE and RE methods and expanded data, they found that high income inequality resulted in an increase in economic growth. Later, Forbes [28] also re-assessed the inequality–growth relationship in 45 countries, from 1966–1995. With the use of FE and RE, Chamberlain's ᴫ matrix procedure and Arrelano and Bond's GMM, the findings showed that as income increased in the short to medium term, economic growth tended to increase. A recent study by Scholl and Klasen [57] revisited the inequality-growth relationship, paying special attention to the role of transition (post-Soviet) countries. The study was based on the specification used by Forbes [28] on a sample of 122 countries over the period of 1961–2012. By using FE, GMM and IV estimation techniques, they found a positive association between inequality and growth in the overall sample which was driven by transition countries.

Studies with inconclusive results on the relationship between income inequality and economic growth

A number of studies yielded inconclusive findings on the inequality–growth nexus. In particular, most reported that the relationship was positive in high-income countries and negative in the low-income countries. For example, Deininger and Squire [25] employed cross-country samples from 1960–1992 to analyse the influence of inequality (income and distribution of assets) on economic growth, and also studied the effect it exerts on reducing poverty. Using OLS and panel data, that study found that income inequality had a negative effect on future growth. In addition, Deininger and Squire [25] reported that high income inequality reduced the income of the poor and boosted the income of the rich. Barro [13] used 2SLS to study the inequality–growth relationship in a panel of countries for the period 1965–1995. The results showed that, in rich countries, inequality positively affected economic growth, while in poor countries it negatively affected growth during the period under study. This means that, for rich countries, as inequality increased, the economy (as measured by Gross Domestic Product [GDP] per capita) tended to increase as well, while in poor countries, the economy tended to decline as inequality increased.

Studies using GMM methods reached similar results. For example, Voitchovsky [63] analysed the link between income distribution and economic growth in 21 developing countries, from 1975–2000. The findings showed that income inequality had a positive effect on growth at the upper decile of income distribution, while inequality negatively affected growth at the lower decile. Similarly, Castelló-Climent [21] confirmed that the relationship between income and growth was positive in high-income countries and negative in low- and middle-income countries. That study examined the correlation between income and human capital and economic growth across countries during the period 1992–2000. The results further indicated that both income and human capital inequality constrained economic growth for low- and middle-income countries. However, in high-income countries, income and human capital inequality encouraged economic growth during the period under study. In yet another investigation, Fawaz et al. [27] studied the income inequality–growth nexus, focusing on its link to credit constraints in high- and low-income developing countries from 1960–2010. The study found similar results, namely that in low-income developing countries, income inequality is negatively related to economic growth. For high-income developing countries, income inequality was positively related to economic growth.

Halter et al. [32] reported that this relationship changed over time, having studied the relationship across countries from 1965–2005, using GMM. The findings showed that, in the short run, high inequality encouraged economic growth, but over the long run, high inequality slowed down the economy and impeded growth. Likewise, Ostry et al. [45] investigated the link between redistribution, inequality and growth in various countries, and found that net inequality was positively correlated to economic performance during the early stage of economic development, but turned negative during the mature stage. Research by Brueckner and Lederman [20] studied the relationship between inequality and GDP per capita growth. Using panel data from 1970 to 2010, the findings documented that in low income countries transitional growth was positively affected by higher income inequality while such effect turned negative in high income countries.

Studies with evidence of no relationship between income inequality and economic growth

Some studies reported no relationship between income inequality and economic growth. For example, research by Niyimbanira [44] focused on how economic growth affected income inequality from 1996–2014. That study employed the FE method and the pooled regression model, using data from 18 municipalities across the provinces of South Africa. The findings confirmed that economic growth reduced poverty, but had no effect on income inequality, which implies that there was no relationship between income inequality and economic growth. Benos and Karagiannis [15] examined the relationship between top income inequality and growth under the influence of physical and human capital accumulation in the U.S. By using 2SLS and GMM on the annual panel of U.S. state-level data during 1929 to 2013, they concluded that changes in inequality do not have an impact on growth. Table 1 shows the summary of empirical studies discussed in this section.

Summary of empirical studies on the association between income inequality and economic growth

Note: - denotes negative; + denotes positive; 0 denotes no relationship

Methodology

As we have discussed in the previous section, the empirical findings on income inequality and growth are highly inconclusive. In this section, by providing a critical survey on methodology issues employed in the prior studies, we offer possible explanations on the disparity found in the empirical findings, particularly on multiple-countries studies. The early multiple-countries studies [9 , 49 , 50] in general reached a consensus on the negative impact of inequality on growth. Although they used different measures of inequality and samples, they all employed the Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) and Two-Stage Least Squares (2SLS) estimation techniques on cross-section data to estimate the coefficient on the inequality variable.

By the late 1990s, however, the general consensus on the negative relationship between income inequality and growth was challenged by concerns over data quality and the methodological procedures used (see Neves and |Silva, [43] ). With regard to the data quality, some studies argued that the dataset used in the previous studies, which lacked comparability due to the use of different income definitions (gross income versus expenditures) can lead to different results (see [10 , 36] ). According to Knowles [36] , European countries, the U.S. and most of the Latin American countries use gross income data whereas most of the African and Asian countries use expenditure data. Since expenditure is more equally distributed than gross income, such difference in income distribution may lead to a difference in the final results.

Concerning the methodological procedures, there has been a shift on the usage of panel data instead of cross-sectional data in the later studies. Forbes [28] argues that the use of panel data is desirable as it can specifically estimate how a change in a country's level of inequality within a given country will affect growth in that country. In addition, panel data can remove bias from the correlation between time-variant, observable country characteristics and the explanatory variables by controlling for differences in these characteristics. Due to these considerations, many studies started to use panel data (see [13 , 28 , 39] ; among others). However, the use of panel data in the studies may lead to more diverse results. One of the possible explanations is the diversity of estimators employed in the panel studies. While most of the cross-section studies use OLS, panel studies use a wide variety of estimators such as fixed effects, random effects, GMM, etc. Given that these estimators have different underlying assumptions, they are likely to produce different results among the panel studies [43] . Another possible explanation is that, unlike the cross-section data, panel data controls for time-variant, observable country characteristics. Given that the impact of inequality on growth tends to differ across countries and regions, the inter-continental variation contribute a substantial part of the effect. Therefore, the usage of panel data analysis may lead to different results when different samples are used in the studies. With the wider usage of various panel data estimation techniques in the later studies, it is not surprising that we found more diverse results in the inequality-growth literature.

Based on the above considerations, researchers should be more cautious when identifying a general global pattern regarding the inequality-growth relationship. Instead, we propose that more emphasis should be placed on identifying the inequality-growth relationship on a national or regional level. Such an approach will provide a better understanding of the inequality-growth process on the study area by overcoming data comparability constraints and possible methodological challenges.

This paper presented a comprehensive literature review of the relationship between income inequality and economic growth. In the theoretical literature, various transmission mechanisms were identified in which income inequality is linked to economic growth, namely the level of economic development, the level of technological development, social-political unrest, the political economy, the imperfection of credit markets, the savings rate, institutions, and the fertility rate. Based on these models, we found that the relationship between income inequality and growth can be negative, positive or inconclusive. For example, based on the level of economic and technological development, the relationship between inequality and growth is positive and becomes negative as the level of development progresses. Inconclusive results were reported by the social-political unrest model, showing that the rise in socio-political unrest stemming from high-income inequality could either dampen or promote growth. In addition, theories on the political economy, the imperfection of credit markets, institutions and the fertility rate, reported that income inequality was negatively related to growth. The only theory which supported the positive relationship between income inequality and growth was the theory of savings rates.

On the empirical front, we found that numerous studies joined the debate by testing the relationship between income inequality and economic growth. Some found a positive relationship, while others identified a negative impact. Some studies yielded inconclusive findings. In particular, most found that the relationship was positive in high-income countries and negative in low-income countries. Several studies documented no relationship between income inequality and economic growth. In the methodology section, we provided a critical survey on methodology issues employed in the prior studies. We argued that the varying results obtained by these studies can be attributed to empirical aspects such as the data comparability and methodological procedures used. We, therefore, suggest that future studies should place more emphasis on identifying the inequality-growth relationship on a national or regional level to better understand the inequality-growth process on the study area. In addition, we conjecture that as the study countries and time span differed in the empirical studies, the impacts of the various theoretical channels we identified previously could also play a uniquely important role in affecting the relationship of the inequality–growth nexus in those studies. It would be prudent for future studies to apply the theoretical models to provide an in-depth analysis of the existing empirical findings. Such findings, with reference to the social, political and economic structure, would provide more relevant policy recommendations to the countries under study.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors of this paper certify that there is no financial or personal interest that influenced the presentation of the paper.

- Search Search Please fill out this field.

- US & World Economies

What Does Income Inequality Look Like in the US?

Understanding America's Income Inequality and Its Causes

Erika Rasure is globally-recognized as a leading consumer economics subject matter expert, researcher, and educator. She is a financial therapist and transformational coach, with a special interest in helping women learn how to invest.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/CSP_ER9-ErikaR.-5942904ef41f4814a94dd1a5c1c03f32.jpg)

Defining Income Inequality

How income inequality is measured, income inequality in the u.s., income inequality has worsened, causes of income inequality, a global perspective, frequently asked questions (faqs).

The Balance / Lara Antal

Income inequality is a wide gap between the money earned by the richest people in an economy when compared to the poorest. Income includes wages, investment earnings, rent, and sales of real estate.

In economic terms, income inequality is the disparity in how income is distributed among individuals, groups, populations, social classes, or countries. It is a major part of how we understand socioeconomic statuses—including how we identify the upper class, middle class, and working class. It's impacted by many other forms of inequality, including wealth, political power, and social status.

Income is a major factor in managing quality of life, as it serves as a means to access health care, education, housing, and more. Income inequality varies by social factors such as sexual identity, gender identity, age, and race or ethnicity, leading to a wider gap between the upper and working classes.

Key Takeaways

- National and global income inequality are becoming growing issues that will need to be addressed.

- The top earners will benefit more from the economic recovery than the bottom earners will.

- In the United States, the top 20% earn more than half of the country's total income.

- Inequality has grown, thanks to outsourcing and companies replacing workers with technology.

- The United States could improve income inequality with employment training and investment in education.

The U.S. Census Bureau measures income inequality using household income. It compares by quintile, which is the population divided into fifths.

Another commonly used measurement is the Gini index, which summarizes the distribution of income into a single number. It ranges from zero, which is a perfectly equal distribution, to one, where only one person has all the money.

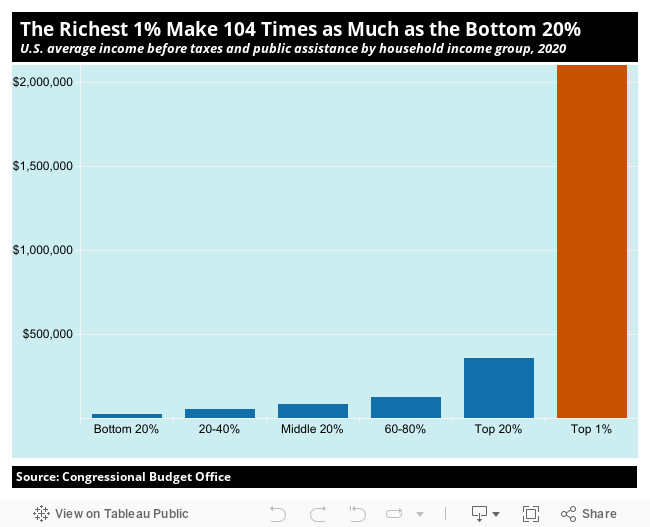

In 2020, the top 20% of the population earned 52.2% of all U.S. income. The median household income fell significantly for the first time since 2011 to $67,521. That's 2.9% down from 2019's number. The richest of the rich, the top 5%, earned 23% of all income. Their average household income was $446,030.

The bottom 20% only earned 3% of the nation’s income. The lowest earner's average household income was $14,589. Most low-wage workers receive no health insurance, sick days, or pension plans from their employers. They can't take off work if they get ill, and have little hope of retiring. Those disparities create health care inequality, which increases the cost of medical care for everyone .

People who can't afford preventive care will often wind up in the hospital emergency room. In 2014, 15.4% of uninsured patients who visited the ER said they went because they had no other place to go. They use the emergency room as their primary care physician. The hospitals passed this cost along to Medicaid.

The U.S. Gini index, which measures distribution and is often used to measure income difference, was 0.489 in 2020. That’s about the same as the prior year, but much worse than in 1968 when it was just 0.386.

For a household of only one individual in the most expensive states in the U.S., a living wage is more than $20 per hour. That would come out to about $41,700 in 2021.

The rich got richer through the recovery from the 2008 financial crisis . Between 1993 and 2015, the average family income grew by 25.7%. The top 1% of the population received 52% of that growth. The chart below tracks the average income growths and losses during the 22 years. It then calculates how much of that total growth was accrued by the top 1% of the population.

This worsening of income inequality had been ongoing even before the 2008 recession. Between 1979 and 2007, household income increased 275% for the wealthiest 1% of households. It rose 65% for the top fifth. The bottom fifth only increased by 18%. That's true even after "wealth redistribution," which entails subtracting all taxes and adding all income from Social Security, welfare, and other payments.

Since the rich got richer faster, their piece of the pie grew larger. The wealthiest 1% of people increased their share of total income by 10%. Everyone else saw their piece of the pie shrink by 1%-2%. Even though the income going to the poor improved, they fell further behind when compared to the richest. As a result, economic mobility decreased.

During this same period, average wages remained flat. That’s despite an increase in worker productivity of 15% and a boost in corporate profits of 13% per year .

Job outsourcing, technology, and deregulation can contribute to income inequality.

Corporations are often blamed for putting profits ahead of workers. U.S. companies try to compete with lower-priced Chinese and Indian companies who pay their workers much less.

As a result, many companies have outsourced their high-tech and manufacturing jobs overseas. The United States lost 36% of its factory jobs from 1980 to 2020. These were traditionally higher-paying union jobs. Service jobs have increased, but these are much lower paid.

Technology also feeds income inequality. It has also replaced many workers in factory jobs. Those who have training in technology can get higher-paying jobs.

Education is can be a powerful factor in improving economic mobility. Over a lifetime, Americans with college degrees earn 84% more than those with only high school degrees.

A McKinsey study found that the achievement gap costs the U.S. economy more than all recessions from the 1970s through 2008.

Deregulation means less stringent investigations into labor disputes. That also benefits businesses more than wage earners.

During the 1990s, companies went public to gain more funds to invest in growth. Managers must now produce ever-larger profits to please stockholders. For most companies, payroll is the largest budget line item. Re-engineering has led to doing more with fewer full-time employees. It also means hiring more contract and temporary employees. Immigrants, many in the country illegally, fill more low-paid service positions. They have less bargaining power to demand higher wages.

In recent years, the Federal Reserve deserves some of the blame. Record-low interest rates were supposed to spur the housing market, making homes more affordable. While that is the case, housing prices have started to rise rapidly in recent years while wages have remained fairly flat.

The average American still doesn't have enough income to buy a home. This lack is especially true for younger people who typically form new households.

By keeping Treasury rates low, the Fed also created an asset bubble in stocks. This helped the top 10%, who own 84% of the wealth in stocks and bonds. Other investors have been buying commodities, driving food prices up 40% since 2009. This increase hurts the bottom 90%, who spend a greater percentage of their income on food.

Emerging markets such as Brazil, and India are becoming more competitive in the global marketplace. Their workforces are becoming more skilled and their economies are becoming more diverse. As a result, the wealth distribution is shifting.

This shift is about lessening global income inequality. The richest 1% of the world's population has 44% of its wealth. While Americans hold 25% of that wealth, China has 22% of the world's population and 8.8% of its wealth. India has 15% of its population and 4% of its wealth. As other countries become more developed, their wealth rises.

How does income inequality affect the economy?

Wage inequality suppresses economic growth by shifting resources toward wealthy savers rather than lower- and middle-class spenders. Studies have shown that, when so much wealth is stowed away among high earners, it stifles aggregate demand by between 2% and 4% of gross domestic product.

Why has income inequality increased?

There are many reasons for the growing disparity in wages in the U.S. Economists have noted that, over the last 40-plus years, policies have largely failed to curb these trends. In particular, the federal minimum wage has lagged well behind economic growth, and support for unions and worker bargaining power has faltered.

Which nations have the highest levels of income inequality?

According to the most recent data from the United Nations University World Institute for Development Economics Research, Angola had the highest disparity of any country with a recorded Gini score in 2019. On the other end of the spectrum is Slovakia.

U.S. Census Bureau. " About ."

U.S. Census Bureau. " Gini Index ."

U.S. Census Bureau. " Income and Poverty in the United States: 2020 ."

The Center for Disease Control. " Reasons for Emergency Room Use Among U.S. Adults Aged 18–64: National Health Interview Survey, 2013 and 2014 ." Page 14.

U.S. Census Bureau. " Historical Income Tables: Income Inequality ." Download Table H-4.

Massachusetts Institute of Technology. " Living Wage Calculator ."

The University of California, Berkley. " The Evolution of Top Incomes in the United States (Updated with 2015 Estimates) ."

Congressional Budget Office. " Trends in the Distribution of Household Income Between 1979 and 2007 ."

Steven Greenhouse. " The Big Squeeze ," Page 5. Anchor, 2009.

Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. " All Employees, Service-Providing ."

Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. " All Employees, Manufacturing ."

Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce. " The College Payoff ."

McKinsey & Company. " The Economic Cost of the US Education Gap ."

Harvard Law School Forum on Corporate Governance. " Looking Behind the Declining Number of Public Companies ."

American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU). " Immigrants and the Economy ."

Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. " Effective Federal Funds Rate ."

Discover. " Why Renters Should Pay Attention to How the Federal Reserve Affects Mortgage Rates ."

Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. " Median Sales Price of Houses Sold for the United States ."

Joiner Center for Housing Studies at Harvard University. " The State of the Nation's Housing ." Page 25.

National Bureau of Economic Research. " Household Wealth Trends in the United States, 1962 to 2016: Has Middle Class Wealth Recovered? " Pages 18-19.

United States Department of Agriculture. " Summary Findings: Food Price Outlook, 2020 ."

Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. " Producer Price Index by Industry: Food Manufacturing ."

United Nations University. " Estimating the Level and Distribution of Global Household Wealth ."

Inequality.org. " Global Inequality ."

Economic Policy Institute. " Inequality Is Slowing U.S. Economic Growth ."

Economic Policy Institute. " Decades of Rising Economic Inequality in the U.S. "

United Nations University World Institute for Development Economics Research. " World Income Inequality Database ."

.cls-1{fill:#0966a9 !important;}.cls-2{fill:#8dc73f;}.cls-3{fill:#f79122;}

Your support helps VCU Libraries make the Social Welfare History Project freely available to all. A generous challenge grant will double your impact.

Economic Inequality: An Introduction

Economic inequality: an introduction .

by Steve Greenlaw , University of Mary Washington

November 24, 2020

Brought up on the Declaration of Independence and the idea that all people are created equal, Americans have traditionally described themselves as living in a classless society. This classless society meant that individual effort and talent contributed to one’s place in society. The vast majority of Americans, it has been believed, are middle class.

Looking at the data , however, it’s clear that economic inequality exists. But what is it? Economic inequality is the unequal distribution of income (earnings) or wealth (net worth or savings) in a society. For example, in the United States, the top 20% of citizens earn more than 20% of the nation’s income, while the bottom 20% earn less than 20% of that income.

There are two perspectives on economic inequality. The first states that income derives from skills and abilities, and from effort. Thus, people with valuable skills and those who work hard earn more income than people who don’t. From this perspective, one’s income is based on decisions one makes, including one’s own efforts. Since anyone can choose to work hard, what one earns is just.

The second perspective on economic inequality points out that skills and abilities may be due to chance, rather than choice. If one is born with extraordinary athletic ability, or a genius IQ, one is likely destined to earn a higher income than one who is not born with those talents. Where is the fairness in that? Even with the same effort, with an uneven playing field, the outcomes are likely to be different.

Few Americans argue for equality of outcomes —that is, everyone earning the same income, regardless of effort. Surveys indicate that Americans are satisfied with some economic inequality, but most prefer less inequality than we have today. The vast majority argue for equality of opportunity —a level playing field—but that is not what we have today. A child of a rich person is more likely to have access to better quality education than a child of a poor person, who may not even have enough to eat on a regular basis or access to basic healthcare. These are things that most Americans take for granted or at least consider a baseline.

As a result, many Americans believe that access to food, housing and perhaps healthcare should be supported by the government through taxes. This is the social safety net or “welfare system,” which includes Aid to Families with Dependent Children, Food Stamps (SNAP), the Earned Income Tax Credit, and Medicaid, for example. The higher one’s income, the more one pays for the social safety net through taxes, both due to the higher tax rates of our progressive tax system , and also in terms of the proportion of tax revenues paid. Thus, the top 20% pays more than 20% of the nation’s tax revenues, but how much more is appropriate? That is the bone of contention.

Since 1980, economic inequality has become greater in the U.S. The reasons for this are not entirely clear, but they include business replacing lesser-skilled workers with technology requiring higher skilled workers. People without a college degree have been particularly at risk of losing income and jobs. Globalization has also contributed to greater inequality as lower skilled jobs have been outsourced. Structural racism has limited Black citizens’ incomes and their ability to accumulate wealth.

The Covid-19 pandemic has both highlighted and exacerbated economic inequality. As millions of Americans lost their jobs, U. S. billionaires’ wealth increased by 31.6%. Relatively low-income people have had to continue to work in the workplace, exposing them more to infection, while higher income people are more likely to be able to work from home. The economic recession which began in early 2020 has most strongly affected people at the lower income levels, costing them jobs and income.

Growing economic inequality serves to fragment the sense of who we are as Americans. People increasingly think of society as consisting of “us” and “them.” In addition, to the extent that economic power buys political power through greater access to elected officials, inequality seems to compromise the legitimacy of government.

A certain degree of economic inequality is probably built into the capitalist economic system, but this inequality can be tempered by appropriate government policies.

Robert Reich . Inequality For All (trailer; 2013)

For further reading:

Gaudiano, P. (2020 July 29) A Board game that brings racial inequities to life . Forbes.

Hanks, A., Solomon, D., and Weller, C. E. (2018 February 21). Systemic inequality. How America’s structural racism helped create the Black-White wealth gap . Center for American Progress.

Inequality.org Topics. Inequality.

Lessig, Lawrence (2013). We the People, and the Republic we must reclaim. TED Talk.

Thorbecke, C. and Mitropoulos, A. (2020 June 28). ‘Extreme inequality was the preexisting condition’: How COVID-19 widened America’s wealth gap . ABCNews

Zakaria, Fareed (2020 May 14). Experts Have Jobs. They need to understand those who don’t . The Washington Post

Poor People’s Campaign The Martin Luther King, Jr. Research and Education Institute. Stanford University.

Thompson, D. E. (2019 June 21). Economic equality: Martin Luther King Jr.’s other dream . The Washington Post.

Boghosian, B.M. (2019 November). The Inescapable casino. Scientific American, 321 (5), 70-77.

How to Cite this Article (APA Format): Greenwood, S. (2020). Economic inequality: An introduction. Social Welfare History Project.

0 Replies to “Economic Inequality: An Introduction”

Comments for this site have been disabled. Please use our contact form for any research questions.

- 2020 Inequality

- Causal Factors

- Health Effects

- Philanthropy

- Student Debt

- Executive Pay

- Hidden Wealth

- Legislative Action

- Sustainability

- Faces on the Frontlines

- Historical Background

- Middle Class Squeeze

- Racial Wealth Divide

- Income Distribution

- Social Mobility

- Wall Street

- Global Struggles

- Inherited Wealth

- Wealth Concentration

- All Research & Commentary

- All Blogging Our Great Divide

- Research & Commentary

- Our Great Divide

- Inequality and Covid-19

Income Inequality

Wealth inequality.

- Racial Economic Inequality

- Global Inequality

- Gender Economic Inequality

- Inequality and Health

- Inequality and Taxes

- Inequality and the Care Economy

- Inequality and Philanthropy

- Inequality Weekly

- Organizations

- Inequality Quotes by Historic World Leaders

- Policy Development

Income Inequality in the United States

Gaps in earnings between America's most affluent and the rest of the country continue to grow year after year.

In the United States, the income gap between the rich and everyone else has been growing markedly, by every major statistical measure, for more than 30 years.

Wage Inequality

Racial income inequality, ceo-worker pay gaps.

Income includes the revenue streams from wages, salaries, interest on a savings account, dividends from shares of stock, rent, and profits from selling something for more than you paid for it. Unlike wealth statistics, income figures do not include the value of homes, stock, or other possessions. Income inequality refers to the extent to which income is distributed in an uneven manner among a population.

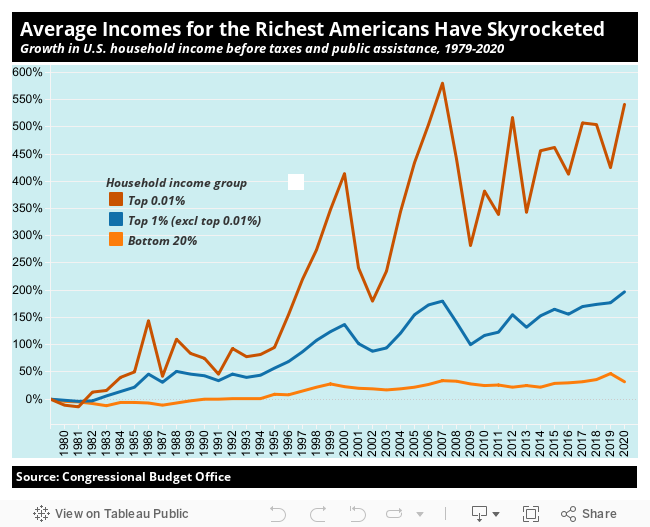

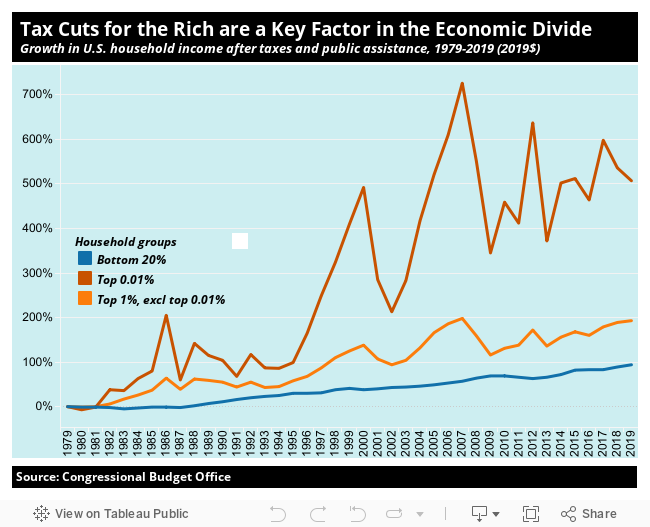

Over the past four decades, the richest 1 percent of Americans have enjoyed by far the fastest income growth. The most rapid increase has occurred at the tippy top of the economic ladder. Between 1979 and 2020, the average income of the richest 0.01 percent of households, a group that today represents about 12,000 households , grew 17 times as fast as the income of the bottom 20 percent of earners. These Congressional Budget Office figures include income from labor and investments. They do not account for taxes and means-tested public assistance, such as food stamps and Medicaid.

Income disparities are now so pronounced that America’s richest 1 percent of households averaged 104 times as much income as the bottom 20 percent in 2020, according to the Congressional Budget Office .

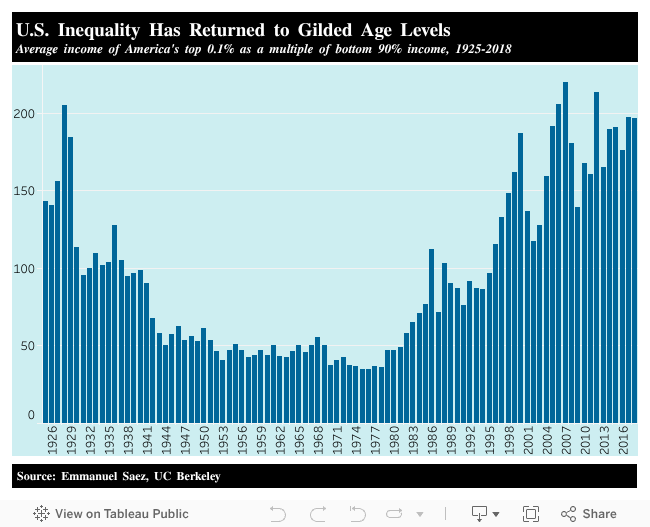

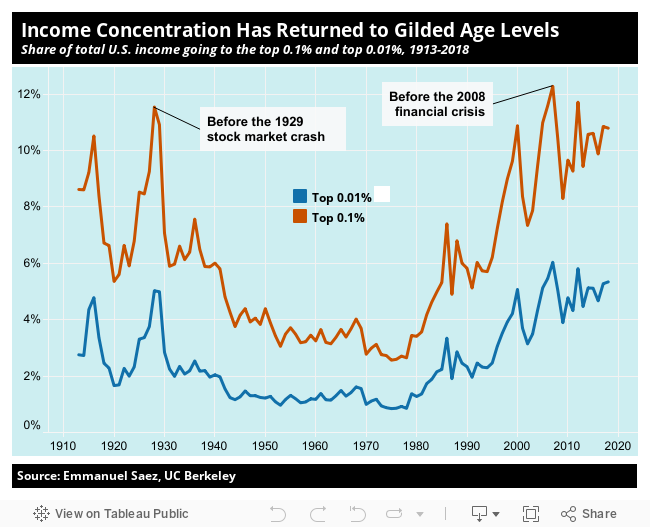

The U.S. income divide has not always been as vast as it is today. In response to the staggering inequality of the Gilded Age in the early 1900s, social movements and progressive policymakers fought successfully to level down the top through fair taxation and level up the bottom through increased unionization and other reforms. But beginning in the 1970s, these levelers started to erode and the country returned to extreme levels of inequality. According to data analyzed by UC Berkeley economist Emmanuel Saez, the ratio between the average income of the top 0.1 percent and the bottom 90 percent reached Gilded Age levels in the years preceding the 2008 financial crisis.

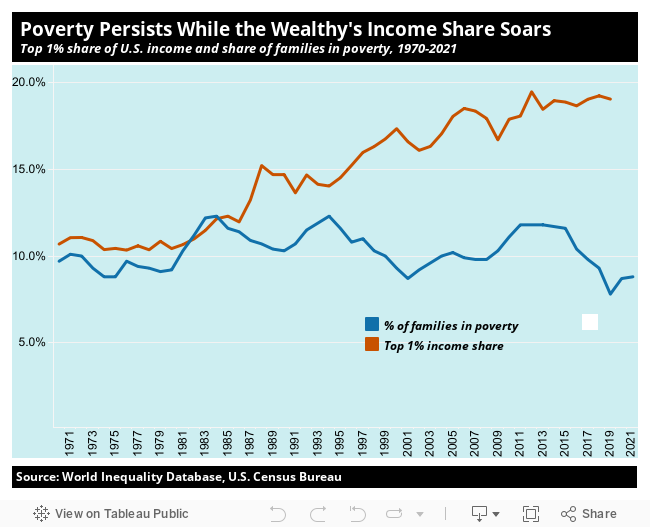

Over the past five decades, the top 1 percent of American earners have nearly doubled their share of national income, according to figures in the World Inequality Database . Meanwhile, the Census Bureau’s “official” poverty rate for all U.S. families has merely inched up and down. In 2011, the Census Bureau began publishing a “supplemental” poverty measure that is more accurate but still likely understates the number of people in the world’s richest country who have to struggle to make ends meet. Federal pandemic relief legislation significantly reduced child poverty rates , but those programs were temporary.

The nation’s highest 0.01 percent and 0.1 percent of income-earners have seen their incomes rise much faster than the rest of the top 1 percent in recent decades. Both of these ultra-rich groups saw their incomes drop immediately after the financial crashes of 1929 and 2008, but they had a much swifter recovery after the more recent crisis. Income concentration today is as extreme as it was during the “Roaring Twenties.”

Congressional Budget Office data show that taxes and means-tested public assistance narrow the income divide somewhat, but the gaps remain staggering. Between 1979 and 2019, the richest 0.01 percent of households had a cumulative income growth rate of 507 percent after accounting for taxes and aid transfers. That’s more than five times the 94 percent growth rate for the bottom 20 percent of households. Tax cuts for the rich are a key driver of this rising inequality. The top U.S. marginal tax rate in 1979 was 70 percent , compared to just 37 percent today.

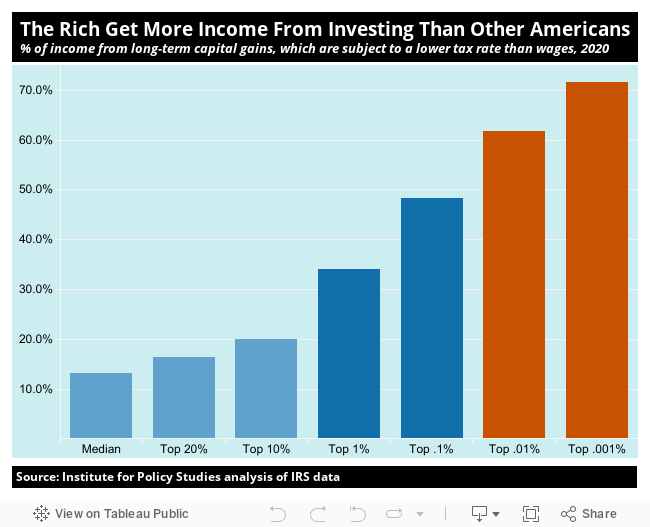

The rich also benefit immensely from the tax code’s preferential treatment of income from investments. Americans who are not among the ultra-rich get the vast majority of their income from wages and salaries. But the higher the U.S. income group, IRS data show, the larger the share of income derived from investment profits. The top tax rate for long-term capital gains is just 20 percent, compared to the top marginal tax rate on ordinary income of 37 percent.

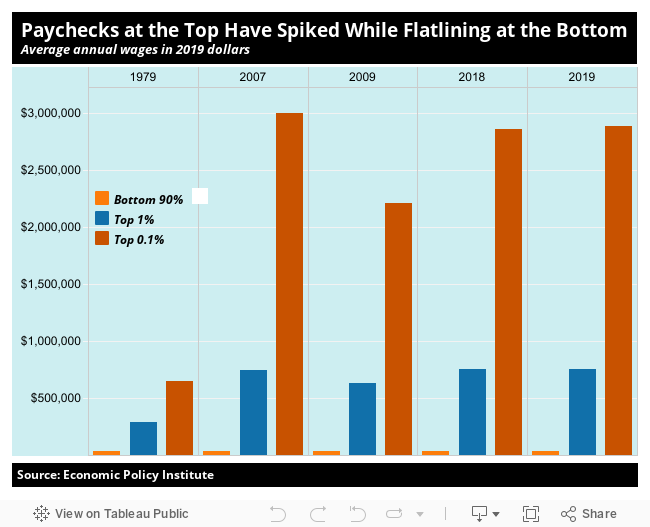

Between 1979 and 2007, according to Economic Policy Institute research , paycheck income for those in the richest 1 percent and 0.1 percent exploded. The wage and salary income for these elite groups dipped after the 2008 financial crisis but recovered relatively quickly. Between 2009 and 2019, the bottom 90 percent had wage growth of just 8.7 percent, compared to 20.4 percent for the top 1 percent and 30.2 percent for the top 0.1 percent.

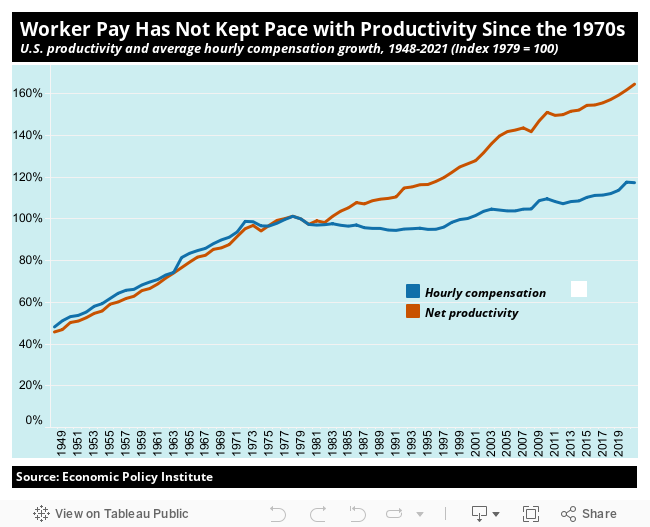

Productivity has increased at a relatively consistent rate since 1948. But the wages of American workers have not, since the 1970s, kept up with this rising productivity. Worker hourly compensation has essentially flat-lined, increasing just 17.3 percent from 1979 to 2021 (after adjusting for inflation). Over this same time period, worker productivity has increased 64.6 percent, according to the Economic Policy Institute . In other words, productivity grew at a rate 3.7 times as fast as worker pay.

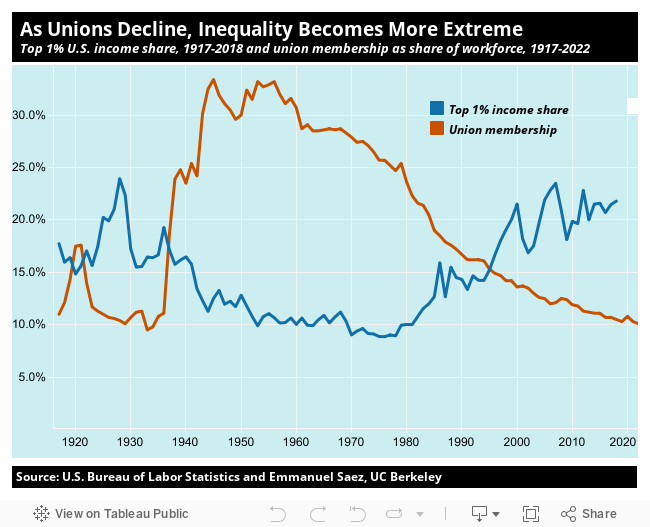

One factor in the widening income divide is the decline of U.S. labor unions. The share of the workforce represented by a union has declined to just 10.1 percent in 2022, down from over 30 percent in the 1940s and 1950s. Meanwhile, those at the top of the income scale have increased their power to rig economic rules in their favor, further increasing income inequality. In 2018, the richest 1% earned over 20 percent of all national income.

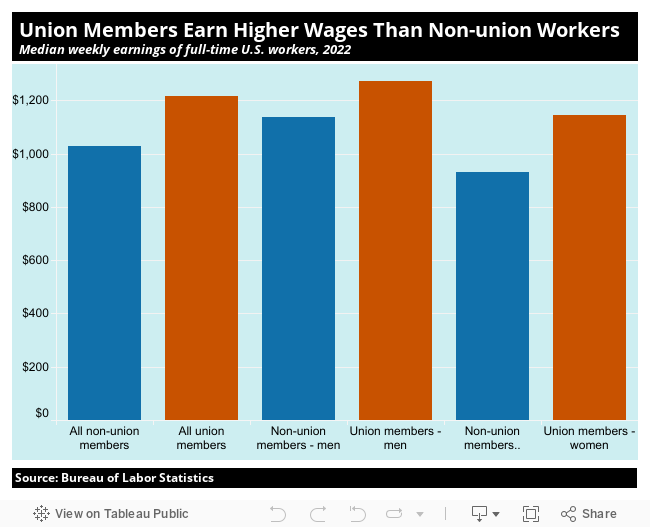

U.S. workers who are unionized continue to earn significantly higher wages than their non-unionized counterparts, according to Bureau of Labor Statistics data , The gap is particularly wide among women. In 2022, median weekly wages for full-time unionized women amounted to $1,146 – $214 more than non-unionized women’s earnings.

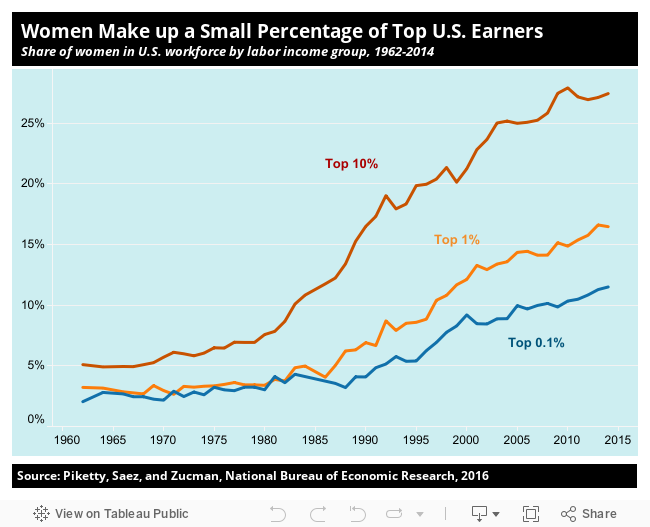

Men make up an overwhelming majority of top earners across the U.S. economy, even though women now represent almost half of the country’s workforce. According to analysis by Thomas Piketty, Emmanuel Saez, and Gabriel Zucman, women comprise just 27 percent of the top 10 percent, and their share of higher income groups runs even smaller. Among the top 1 percent, women make up slightly less than 17 percent of workers, while at the top 0.1 percent level, they make up only 11 percent.

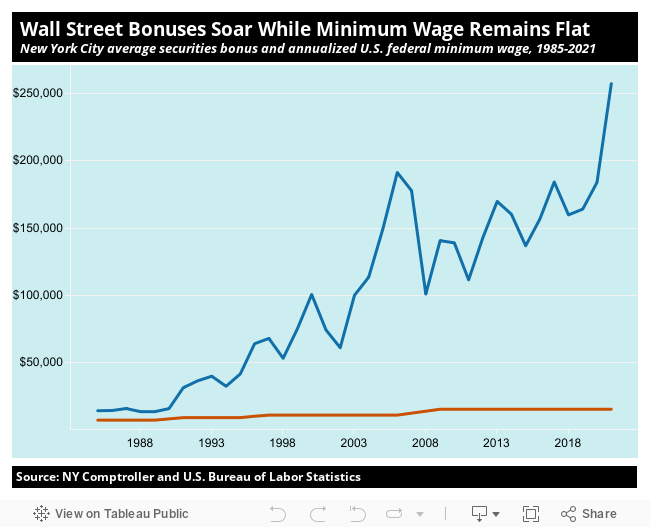

Since 1985, the average Wall Street bonus has increased 1,743 percent, from $13,970 to $257,500 in 2021 (not adjusted for inflation). According to Institute for Policy Studies analysis , if the minimum wage had increased at that rate, it would be worth $61.75 today, instead of $7.25. The total 2021 bonus pool for 180,000 New York City-based Wall Street employees was $45 billion — enough to pay for more than 1 million jobs paying $15 per hour for a year. Because the very rich can squirrel away much of their income, huge Wall Street bonuses don’t have nearly the stimulus effect as raising pay for low-wage workers who have to spend nearly every dollar they make. The sharp rise in Wall Street bonuses has also contributed to race and gender inequality, as detailed in our facts sections on those issues.

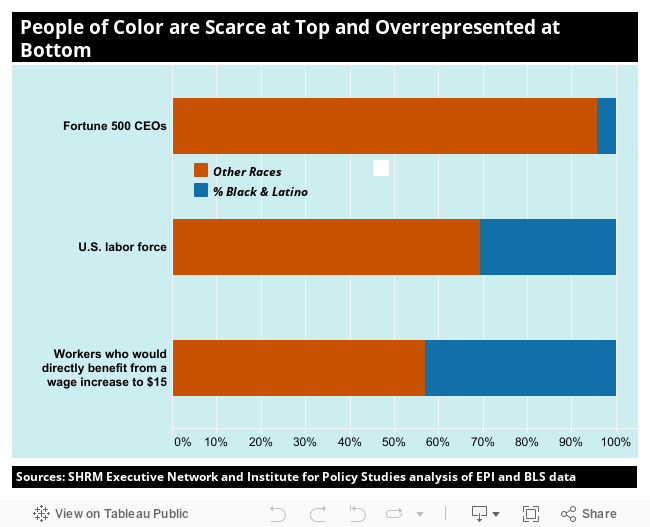

In 2021, Fortune 500 CEOs, who earned $18.3 million on average, included just four Black and 17 Latino people — just 4 percent of the total. By contrast, these groups made up 43 percent of the U.S. workers who would benefit from a raise in the federal minimum wage to $15 per hour by 2025, according to Institute for Policy Studies analysis of Economic Policy Institute data. Black and Latino people comprise 31 percent of the entire U.S. labor force.

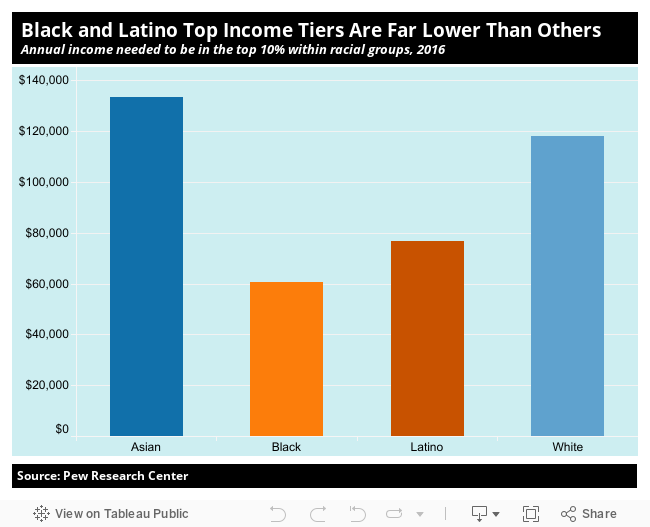

One indicator of racial disparities at the top of the U.S. earnings scale is the threshold for entry into the top 10 percent. According to the Pew Research Center , for white families to make it into this tier of earners in their racial group, they need to have annual income of at least $117,986 — nearly twice as much as the threshold for Black families.

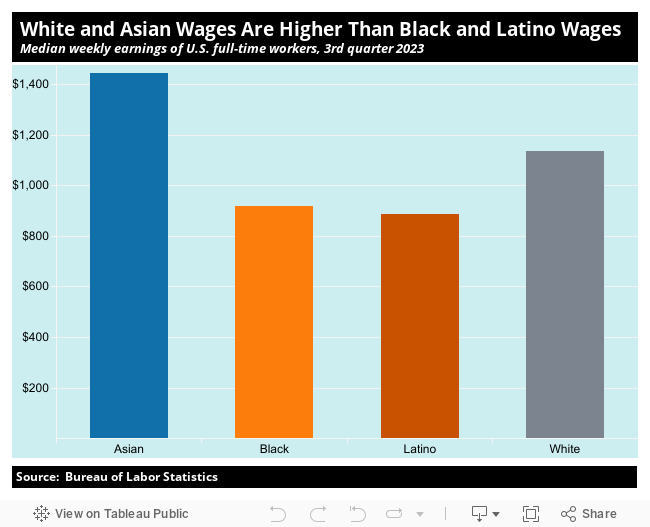

Racial discrimination in many forms, including in education, hiring, and pay practices, contributes to persistent earnings gaps. As of the third quarter of 2023, the median white worker made 24 percent more than the typical Black worker and around 28 percent more than the median Latino worker, according to BLS data .

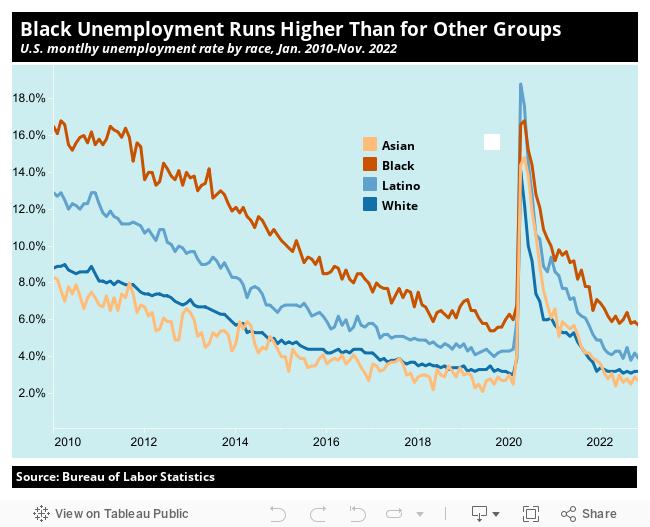

The Black unemployment rate has persistently run about twice as high as for white workers. These rates only count those who are actively seeking work, leaving out those who have given up finding a job. While racial gaps have narrowed somewhat in recent years, the divides remain wide. In November 2022, Black unemployment stood at 5.7 percent, compared to 3.2 percent for white workers, according to BLS data .

CEO pay has been a key driver of rising U.S. income inequality for decades, and the gap between CEO and worker pay only widened during the pandemic.

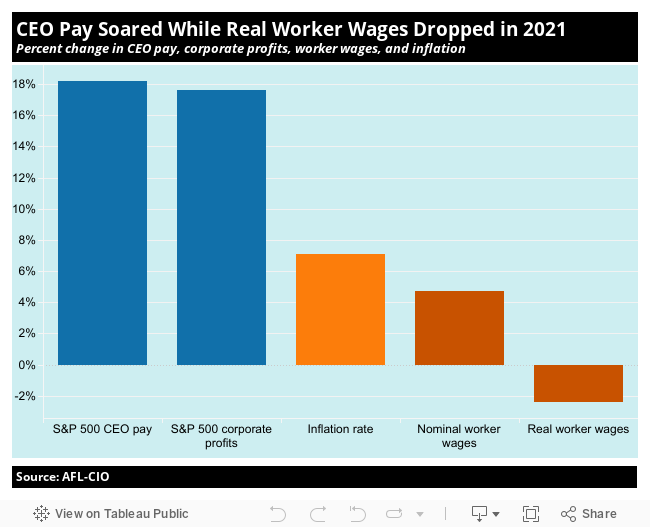

In 2021, corporate CEOs were quick to blame worker wages for causing inflation. But an AFL-CIO analysis reveals that workers’ real wages actually fell 2.4 percent in 2021 after adjusting for inflation. Meanwhile, S&P 500 companies increased their CEO pay by an average of 18.2 percent while enjoying record profits and spending a record $882 billion on stock buybacks.

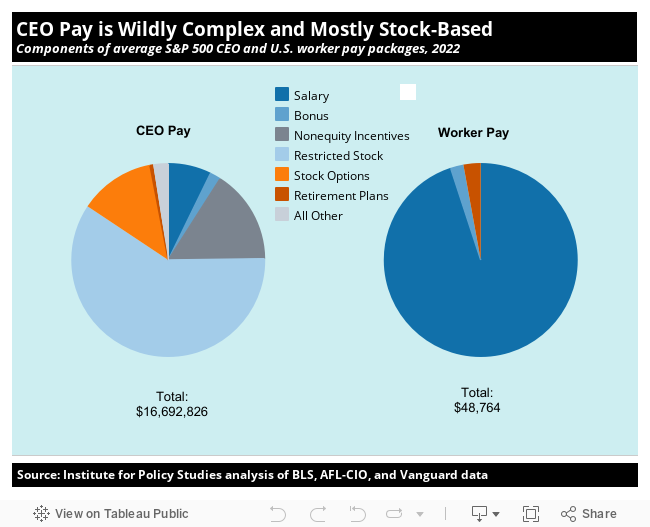

Corporate boards lavish wildly complex compensation packages on their top executives, mostly in various forms of stock-based pay. The objective? To give the impression of a “pay for performance” system that aligns the interests of CEOs and shareholders. By contrast, ordinary American workers receive nearly all of their compensation in the form of cash salary or wages. In the chart above, we’ve added to the BLS median annual wage a bonus worth 2.3 percent and an employer 401(k) contribution worth 3 percent of base pay.

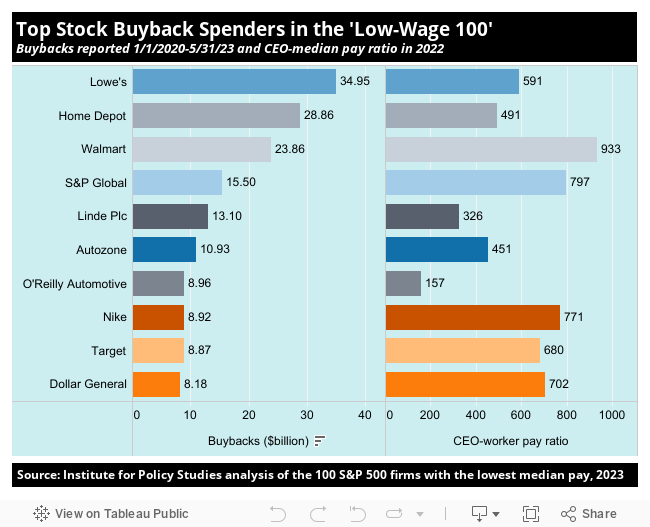

In reality, the notion that Corporate America has a CEO “pay for performance” system is a myth . One common ploy for inflating CEO pay? Stock buybacks. This financial maneuver siphons funds from worker wages while artificially pumping up the value of CEO stock-based pay. The Institute for Policy Studies Executive Excess 2023 report examines buyback activity among the 100 S&P 500 corporations with the lowest median wages. Between January 1, 2020, and May 31, 2023, fully 90 percent of these firms spent company resources on buybacks, for a total expenditure of $341 billion. During their stock buyback spree, the value of CEOs’ personal stock holdings at these “Low-Wage 100” firms increased more than three times as fast as their median worker pay.

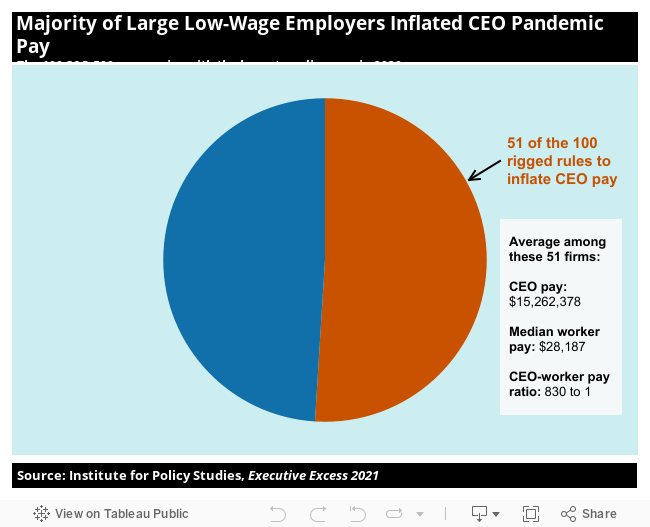

During the pandemic, corporate boards took explicit actions to shield their CEOs’ massive paychecks while workers were suffering. An Institute for Policy Studies analysis found that more than half of the 100 S&P 500 companies with the lowest median worker pay moved bonus goalposts or otherwise rigged rules to inflate CEO pay in 2020. Among these rule-rigging corporations, CEO compensation averaged $15.3 million, up 29 percent from 2019. Median worker pay ran $28,187 on average, 2 percent lower than the 2019 worker pay rate. The ratio between CEO and median worker pay at these 51 firms averaged 830 to 1.

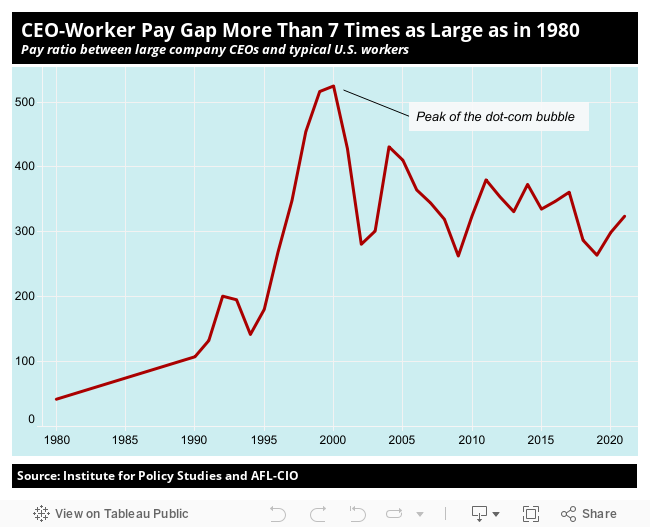

With U.S. unions playing a smaller economic role, the gap between worker and CEO pay has exploded since the early 1990s. In 1980, the average big company CEO earned just 42 times as much as the average U.S. worker. In 2021, the CEO-worker pay gap was nearly eight times larger than in 1980. According to the AFL-CIO , S&P 500 firm CEOs were paid 324 times as much as average U.S. workers in 2021. CEO pay averaged $18.3 million, compared to average worker pay of $58,260. During the 21st century, the annual gap between CEO pay and typical worker pay has averaged about 350 to 1.

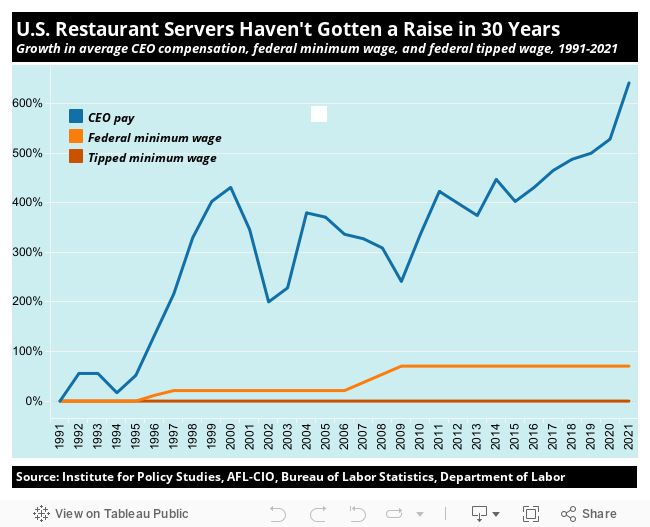

The CEO pay explosion, as shown in AFL-CIO analysis , contrasts sharply with trends at the bottom end of the U.S. wage scale. Average CEO pay at S&P 500 corporations is up 642 percent since 1991, while Congress has not passed a minimum wage increase for more than a decade. The federal minimum wage for restaurant servers and other tipped workers has been frozen at just $2.13 per hour since 1991. According to the Labor Department , 27 states have raised their tipped minimum, while retaining this two-tier system. Seven states and the District of Columbia have eliminated or are phasing out the subminimum tipped wage altogether, while in Michigan the issue was tied up in the courts as of December 2022. In six states, the tipped minimum is still $2.13. While employers are technically supposed to make up the difference if workers don’t earn enough in tips to reach the $7.25 federal minimum, this rule is largely unenforced.

Stay informed

Subscribe to our weekly newsletter.

Inequality.org → In Your Inbox

Get the indispensable guide to the latest on our unequal world, in your inbox every Wednesday.

You can unsubscribe any time. We do not sell or share your information with others. Click to close

- ⋮⋮⋮ ×

Exploring Economic Inequality with Data

This set of assignments exposes students to data pertaining to economic inequality in international and historical context. The first assignment asks students to use Lorenz Curves and Gini Coefficients to summarize inequality in income and taxes reported by the IRS.

The second sends them to the United Nations Human Development Indicators page to find cross-country data on Gini Coefficients and some other development indicator which they hypothesize to be correlated with inequality.

In the third assignment, students estimate wealth inequality from 1774 probate records and compare the result with estimates of 20th-century wealth inequality.

These early assignments serve as "scaffolding" for the ultimate assignment-a thesis-driven argument supported by data drawn from one or more of the sources used here.

Expand for more detail

Activity Classification and Connections to Related Resources Collapse

Grade level, learning goals, context for use, description and teaching materials.

- Part 1: Income and Tax Inequality in the US IRS web page

- Part 2: Income Inequality around the World United Nations Human Development Indicators statistics page

- Part 3: Wealth Inequality in the Colonies and Today American Colonial Wealth Estimates, 1774-study #7329 (Note: You must belong to an ICPSR member institution to have access to their data. You can find out if your institution is a member at the ICPSR membership page

Teaching Notes and Tips

- Quality of thesis

- Quality of argument

- Accuracy in use of data

- Quality of writing

- Quality of data presentation

References and Resources

See more Examples »

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

15.4: Assignment- Inequality and Childcare

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 48512

In this module we learned about several programs which are designed to offer help to the poor and near poor. These programs include Temporary Assistance to Needy Families (TANF), the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC), Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP, also known as Food Stamps) and Medicaid.

What if the government provided free childcare for the poor and near poor? What reasoning would the government have for providing this service? Do you think that would reduce the number of lower income Americans? Would free childcare suffer from the poverty trap? Considering all the issues, would you support offering free childcare as an additional element in the safety net? Explain your reasoning.

- Assignment: Income Distribution. Authored by : Steven Greenlaw and Lumen Learning. Provided by : Lumen Learning. License : CC BY: Attribution

Income Inequality

Income disparity refers to how income is distributed unequally across a population. The larger the income inequality, the less fair the distribution. Wealth disparity, or the unequal distribution of wealth, is frequently associated with income inequality.

The unequal distribution of income among individuals or households within a society is referred to as income inequality. It is frequently assessed by the Gini coefficient, which ranges from 0 (perfect equality) to 1 (perfect inequality). A tiny percentage of the population obtains a big share of total income in a society with high income disparity, whereas the bulk receives a smaller share.

There are several factors that can contribute to income inequality:

(a) Wage Disparities: Wage disparities between occupations, industries, and skill levels can all contribute to income inequality. High-demand occupations or specialized abilities frequently earn higher pay.

(b) Education and Skill Levels: Higher education and advanced abilities are frequently linked to better-paying professions. Those who have access to high-quality education and training earn more, while those with inadequate education may have fewer options for well-paying professions.

(c) Globalization: Income disparity can be influenced by global commerce and economic integration. While globalization might open up new economic opportunities, it can also cause job displacement in specific industries and locations, potentially increasing income inequality.

(d) Technological Advancements: Technological progress can lead to automation and job displacement in certain sectors. This can result in increased demand for skilled workers in technology-related fields and lower demand for low-skilled labor, contributing to income disparities.

(e) Labor Market Changes: Shifts in the labor market, such as the rise of temporary and gig economy jobs, can impact job security and income stability, leading to disparities in earnings.

(e) Taxation and Social Policies: Government policies, such as tax rates, social welfare programs, and minimum wage laws, can influence income distribution. Policies that favor wealthier individuals or corporations can exacerbate income inequality, while social programs can mitigate it.

(f) Inheritance and Wealth: The intergenerational transfer of wealth can perpetuate income inequality. Individuals born into wealthy families have access to resources, education, and opportunities that can give them a head start in their careers.

Discrimination based on race, gender, or ethnicity can restrict access to opportunities and higher-paying positions, adding to income inequality. Income distribution can be influenced by economic volatility, market demand and supply dynamics, and other market forces. Lower-income people are disproportionately affected by economic downturns.

Income disparity can have serious social, economic, and political consequences. Income inequality can cause social discontent, lower social mobility, and lower overall economic growth. Governments frequently enact strategies to reduce income disparity, such as progressive taxation, social safety nets, school reforms, and workforce development programs.

Material Flow Accounting

Point of total assumption, microeconomics definition, stagflation definition, annual report 2015-2016 of rieter group, traffic code, labour economics, nonrecourse debt, actuarial science, objectives of islamic banking branch of prime bank limited, latest post, mechanical resonance, sympathetic resonance, cycloalkyne – in organic chemistry, weedy rice gains competitive advantage from its wild companions, both cheap and pricey treatments prevented migraines, flame ionization detector (fid).

We serve the public by pursuing a growing economy and stable financial system that work for all of us.

- Center for Indian Country Development

- Opportunity & Inclusive Growth Institute

Monetary Policy

- Banking Supervision

- Financial Services

- Community Development & Outreach

- Board of Directors

- Advisory Councils

Work With Us

- Internships

- Job Profiles

- Speakers Bureau

- Doing Business with the Minneapolis Fed

Overview & Mission

The ninth district, our history, diversity & inclusion, region & community.

We examine economic issues that deeply affect our communities.

- Request a Speaker

- Publications Archive

- Agriculture & Farming

- Community & Economic Development

- Early Childhood Development

- Employment & Labor Markets

- Indian Country

- K-12 Education

- Manufacturing

- Small Business

- Regional Economic Indicators

Community Development & Engagement

The bakken oil patch.

We conduct world-class research to inform and inspire policymakers and the public.

Research Groups

Economic research.

- Immigration

- Macroeconomics

- Minimum Wage

- Technology & Innovation

- Too Big To Fail

- Trade & Globalization

- Wages, Income, Wealth

Data & Reporting

- Income Distributions and Dynamics in America

- Minnesota Public Education Dashboard

- Inflation Calculator

- Recessions in Perspective

- Market-based Probabilities

We provide the banking community with timely information and useful guidance.

- Become a Member Bank

- Discount Window & Payments System Risk

- Appeals Procedures

- Mergers & Acquisitions (Regulatory Applications)

- Business Continuity

- Paycheck Protection Program Liquidity Facility

- Financial Studies & Community Banking

- Market-Based Probabilities

- Statistical & Structure Reports

Banking Topics

- Credit & Financial Markets

- Borrowing & Lending

- Too Big to Fail

For Consumers

Large bank stress test tool, banking in the ninth archive.

We explore policy topics that are important for advancing prosperity across our region.

Policy Topics

- Labor Market Policies

- Public Policy

Racism & the Economy

An assignment model of knowledge diffusion and income inequality.

Staff Report 509 | Published March 27, 2015

Randomness in individual discovery disperses productivities, whereas learning from others keeps productivities together. Long-run growth and persistent earnings inequality emerge when these two mechanisms for knowledge accumulation are combined. This paper considers an economy in which those with more useful knowledge can teach others, with competitive markets assigning students to teachers. In equilibrium, students with an ability to learn quickly are assigned to teachers with the most productive knowledge. This sorting on ability implies large differences in earnings distributions conditional on ability, as shown using explicit formulas for the tail behavior of these distributions.

Related Content

Perspectives on the Labor Share