We will keep fighting for all libraries - stand with us!

Internet Archive Audio

- This Just In

- Grateful Dead

- Old Time Radio

- 78 RPMs and Cylinder Recordings

- Audio Books & Poetry

- Computers, Technology and Science

- Music, Arts & Culture

- News & Public Affairs

- Spirituality & Religion

- Radio News Archive

- Flickr Commons

- Occupy Wall Street Flickr

- NASA Images

- Solar System Collection

- Ames Research Center

- All Software

- Old School Emulation

- MS-DOS Games

- Historical Software

- Classic PC Games

- Software Library

- Kodi Archive and Support File

- Vintage Software

- CD-ROM Software

- CD-ROM Software Library

- Software Sites

- Tucows Software Library

- Shareware CD-ROMs

- Software Capsules Compilation

- CD-ROM Images

- ZX Spectrum

- DOOM Level CD

- Smithsonian Libraries

- FEDLINK (US)

- Lincoln Collection

- American Libraries

- Canadian Libraries

- Universal Library

- Project Gutenberg

- Children's Library

- Biodiversity Heritage Library

- Books by Language

- Additional Collections

- Prelinger Archives

- Democracy Now!

- Occupy Wall Street

- TV NSA Clip Library

- Animation & Cartoons

- Arts & Music

- Computers & Technology

- Cultural & Academic Films

- Ephemeral Films

- Sports Videos

- Videogame Videos

- Youth Media

Search the history of over 866 billion web pages on the Internet.

Mobile Apps

- Wayback Machine (iOS)

- Wayback Machine (Android)

Browser Extensions

Archive-it subscription.

- Explore the Collections

- Build Collections

Save Page Now

Capture a web page as it appears now for use as a trusted citation in the future.

Please enter a valid web address

- Donate Donate icon An illustration of a heart shape

Essays ancient & modern

Bookreader item preview, share or embed this item, flag this item for.

- Graphic Violence

- Explicit Sexual Content

- Hate Speech

- Misinformation/Disinformation

- Marketing/Phishing/Advertising

- Misleading/Inaccurate/Missing Metadata

inherent skewed text on some pages due to runs into gutter some pages are tight binding

![[WorldCat (this item)] [WorldCat (this item)]](https://archive.org/images/worldcat-small.png)

plus-circle Add Review comment Reviews

97 Previews

6 Favorites

DOWNLOAD OPTIONS

No suitable files to display here.

EPUB and PDF access not available for this item.

IN COLLECTIONS

Uploaded by station27.cebu on February 5, 2020

Essays, ancient & modern

By t. s. eliot.

- 4 Want to read

- 1 Currently reading

- 1 Have read

Preview Book

My Reading Lists:

Use this Work

Create a new list

My book notes.

My private notes about this edition:

Check nearby libraries

Buy this book

Lancelot Andrewes -- John Bramhall -- Francis Herbert Bradley -- Baudelaire in our time -- The humanism of Irving Babbitt -- Religion and literature -- Catholicism and international order -- The Pensées of Pascal -- Modern education and the classics -- In memoriam

Previews available in: English

Showing 8 featured editions. View all 8 editions?

Add another edition?

Book Details

Published in, table of contents, edition notes.

Gallup, D.C. Eliot (rev. ed.), A31a Published in part, in 1928, under title: For Lancelot Andrewes. "First published in March 1936"--Verso of t.p.

Classifications

The physical object, community reviews (0).

- Created April 1, 2008

- 12 revisions

Wikipedia citation

Copy and paste this code into your Wikipedia page. Need help ?

Download the free Kindle app and start reading Kindle books instantly on your smartphone, tablet, or computer - no Kindle device required .

Read instantly on your browser with Kindle for Web.

Using your mobile phone camera - scan the code below and download the Kindle app.

Image Unavailable

- To view this video download Flash Player

Follow the author

Essays Ancient And Modern Hardcover – January 1, 1936

- Language English

- Publisher Harcourt Brace and Company, NY

- Publication date January 1, 1936

- See all details

Customers who viewed this item also viewed

Product details

- ASIN : B0008564ES

- Publisher : Harcourt Brace and Company, NY (January 1, 1936)

- Language : English

- Item Weight : 1 pounds

- Best Sellers Rank: #5,548,693 in Books ( See Top 100 in Books )

About the author

T. s. eliot.

Thomas Stearns Eliot was born in 1888 in St. Louis, Missouri, and became a British subject in 1927. The acclaimed poet of The Waste Land, Four Quartets, and Old Possum's Book of Practical Cats, among numerous other poems, prose, and works of drama, won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1948. T.S. Eliot died in 1965 in London, England, and is buried in Westminster Abbey.

Photo by Lady Ottoline Morrell (1873–1938) derivative work: Octave.H [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons.

Customer reviews

Customer Reviews, including Product Star Ratings help customers to learn more about the product and decide whether it is the right product for them.

To calculate the overall star rating and percentage breakdown by star, we don’t use a simple average. Instead, our system considers things like how recent a review is and if the reviewer bought the item on Amazon. It also analyzed reviews to verify trustworthiness.

- Sort reviews by Top reviews Most recent Top reviews

By T. S. Eliot

Add Book To Favorites

Is this your library?

Sign up to save your library.

With an OverDrive account, you can save your favorite libraries for at-a-glance information about availability. Find out more about OverDrive accounts.

T. S. Eliot

Houghton Mifflin Harcourt

11 February 2014

Find this title in Libby, the library reading app by OverDrive.

Search for a digital library with this title

Title found at these libraries:.

T. S. Eliot

T. S. Eliot grew up in St. Louis, Missouri. He was educated first at Harvard University and then at Oxford University, with a break at the Sorbonne in Paris between his undergraduate and graduate degrees in Boston. He moved to England and began a strained marriage with Vivian Haigh-Wood in 1915. He supported himself by working at Lloyd's Bank in London from 1917-1925, then joined a publishing firm. In 1927, he became a British citizen and joined the Anglican Church. He was drawn to European fascism in the 1930s, but unlike Pound remained uninvolved in politics. His literary criticism, both on individual poets and on general principles of analysis, heavily influenced the American "New Critical" movement from the 1930s through the 1960s. His more general social criticism was more idiosyncratic; its Christian cultural commitments earned him an audience but its occasional anti-Semitism and severe conservatism isolated him from many readers. Eliot has a career that runs from "The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock” through The Waste Land to Four Quartets . He had notable success with his verse plays, among them Murder in the Cathedral (1935) and The Cocktail Party (1949).

When The Waste Land first appeared in journals on both sides of the ocean in 1922, it evoked for many readers the ruined landscape left to them after the historically unique devastation of trench warfare and mass slaughter of the first world war. Its fragments mirrored a shattered world, and its allusions, however erudite, recalled a civilized culture many felt they had lost. Even its tendency to taunt readers with failed possibilities of spiritual rebirth, along with its glimpses of a religious route to joining the pieces of a dismembered god and a broken socius, struck a chord. Eliot was one of many major modernist writers to yearn for a mythic synthesis remaining out of reach. In a surprisingly short period of time, The Waste Land became the preeminent poem of modernism, the unquestioned symbol of what was actually a much more diverse movement. Eventually, as its shadow came to hide other kinds of modernism—from more decisively vernacular language to poems strongly identified with race or revolution— The Waste Land gathered a set of compensatory ambitions and resentments.

Bibliography

- T. S. Eliot Bibliography

Biographical Criticism

- Ronald Bush: On "T. S. Eliot's Life and Career"

- T. S. Eliot: Biographical Timeline

General Criticism

- Stephen Spender: On "General Statements on Eliot"

- J. Hillis Miller: On "General Statements on Eliot"

Other Writing by the Poet

- T. S. Eliot: On "Tradition and the Individual Talent"

Poet Details

Poet timeline, t. s. eliot is born. 26 september, 1888.

Thomas Sterns Eliot is born September 26, 1888. He is born in St. Louis, Missouri, to Henry Ware Eliot and Charlotte Champe Stearns.

Eliot is a student at Smith Academy in St. Louis 1 January, 1898

Eliot attends milton academy in massachusetts 1 january, 1905, eliot's undergraduate years at harvard. reads symons’s the symbolist movement in literature and the poetry of laforgue. studies with george santayana and irving babbitt 1 january, 1906, eliot spends a year at the sorbonne in paris. in the summer of 1911, finishes a version of "the love song of j. alfred prufrock" 1 january, 1910, eliot returns to harvard to study philosophy as a graduate student. begins doctoral thesis on f.h. bradley. 1 january, 1911, t. s. eliot visits paris to attend paris university. 1 september, 1911.

· In May 1910, Eliot had a suspected case of scarlet fever which almost prevented his graduation from Harvard University. In fall Eliot undertook a postgraduate year in Paris at the University of Paris.

Eliot Goes To England on fellowship; meets Ezra Pound. 1 January, 1914

Eliot studies abroad in germany. 1 june, 1914.

· Eliot spends the beginning of 1914’s summer studying at a seminar in Marburg, Germany. Eliot departs from Germany early due to the impending World War and goes to London around August, where he meets Ezra Pound.

T. S. Eliot meets Ezra Pound. 1 August, 1914

Eliot travels with Conrad Aiken to London from Germany because of increasing war tensions. Here he meets Ezra Pound. Aiken shows Pound Eliot's poetry, which greatly impresses Pound.

Eliot marries Vivien Haigh-Wood on June 26th; begins publishing poems that later appear in the Prufrock volume. 1 January, 1915

Eliot works as teacher at highgate junior school and as university extension lecturer 1 january, 1916, eliot publishes prufrock and other observations 1 january, 1917, eliot takes a position at lloyds bank in the colonial and foreign department. 1 january, 1917, eliot publishes ezra pound: his metric and poetry 1 january, 1918, eliot's "tradition and the individual talent" appears in the egoist. 1 january, 1919, eliot publishes poems 1 january, 1919, eliot publishes the sacred wood: essays on poetry and criticism 1 january, 1920.

The Sacred Wood is a collection of essays that Eliot wrote on many authors including Shakespeare, Dante, and William Blake.

Eliot Publishes Ara Vos Prec 1 January, 1920

Eliot takes leave from lloyds bank. recuperating at margate and lausanne, finishes the drafts of the waste land, which he then shows to pound. 1 january, 1921, eliot takes several months off to rest after a nervous breakdown. 1 june, 1921.

Eliot suffers a breakdown in the summer of 1921 as a result of his father's passing in 1919 and his wife Vivien's deteriorating health. After his breakdown, his physician recommends taking time off to recover. His physician recommended taking time off at the coast of Margate in England. Eliot's friend Bertrand Russell recommends a sanitarium in Lausanne Switzerland. Over the course of 3 months Eliot spends time at both where he finishes his writings on "The Waste Land".

Eliot Publishes The Waste Land 1 January, 1922

The Waste Land is a 434 line poem presented in five-parts, written by T. S. Eliot; considered by many to be one of the greatest poets in history. It is one of the most important writings of modernist poetry. The Waste Land loosely follows the legend of the Holy Grail and the Fisher King while including cultural shades from Western canon, Buddhism and Hindu Upanishads. The Waste Land is highly recommended for those who enjoy important poetic works and for those newly discovering the talent of T. S. Eliot.

Eliot Publishes Homage to John Dryden: Three Essays On Poetry Of The Seventeenth Century 1 January, 1924

Three essays on 17th century literature, with particular emphasis on Dryden's poetry and criticism

Eliot Publishes Poems 1909-1925 1 January, 1925

Eliot joins the publishing house of faber & gwyer, leaves lloyds bank 1 january, 1925, eliot delivers the clark lectures at cambridge university. 1 january, 1926.

· Eliot delivers the Clark Lectures at Cambridge University in 1926. His speech was entitled “The metaphysical poetry of the 17th century”. His speech took place Friday, January 1st 1926 at 2 pm.

Eliot Publishes Sweeney Agonistes 1 January, 1926

Eliot enters the church of england and assumes british citizenship 1 january, 1927, eliot publishes shakespeare and the stoicism of seneca 1 january, 1927, eliot publishes journey of the magi 1 january, 1927, eliot publishes a song for simeon 1 january, 1928.

Contains a drawing by E. McKnight Kauffer

Eliot Publishes For Lancelot Andrewes: Essays On Style And Order 1 January, 1928

Eliot publishes dante 1 january, 1929, eliot publishes animula 1 january, 1929, eliot publishes ash-wednesday 1 january, 1930, eliot publishes marina 1 january, 1930, eliot publishes thoughts after lambeth 1 january, 1931, eliot publishes triumphal march 1 january, 1931, eliot publishes charles whibley: a memoir 1 january, 1931, eliot publishes selected essays 1917-1932 1 january, 1932, eliot publishes john dryden: the poet, the dramatist, the critic 1 january, 1932.

This study of the noted literary figure of the Restoration deals separately with his various roles as poet, dramatist and critic.

Eliot delivers the Norton Lectures at Harvard University. 1 January, 1932

· Eliot delivers the Norton Lectures at Harvard University in 1932 and 1933. Eliot’s 1932-33 speech was entitled “The Use of Poetry and the Use of Criticism: Studies in the Relation of Criticism to Poetry in England. This speech was later published by Harvard University Press.

Eliot’s 1932-33 Norton lectures at Harvard published under the title The Use of Poetry and the Use of Criticism (1933). At the University of Virginia, he delivers the lectures later published as After Strange Gods (1934). Obtains legal separation from Viv 1 January, 1933

Eliot publishes the use of poetry and the use of criticism: studies in the relation of criticism to poetry in england 1 january, 1933.

Eliot begins with the appearance of poetry criticism in the age of Dryden, when poetry became the province of an intellectual aristocracy rather than part of the mind and popular tradition of a whole people. Wordsworth and Coleridge, in their attempt to revolutionize the language of poetry at the end of the eighteenth century, made exaggerated claims for poetry and the poet, culminating in Shelley's assertion that "poets are the unacknowledged legislators of mankind." And, in the doubt and decaying moral definitions of the nineteenth century, Arnold transformed poetry into a surrogate for religion.

By studying poetry and criticism in the context of its time, Eliot suggests that we can learn what is permanent about the nature of poetry, and makes a powerful case for both its autonomy and its pluralism in this century.

Eliot Publishes Words For Music 1 January, 1934

Eliot publishes after strange gods: a primer of modern heresy 1 january, 1934, eliot publishes the rock: a pageant play 1 january, 1934.

The choruses in this pageant play represent a new verse experiment on Mr. Eliot's part; and taken together make a sequence of verses about twice the length of "The Waste Land." Mr. Eliot has written the words; the scenario and design of the play were provided by a collaborator, and the purpose was to provide a pageant of the Church of England for presentation on a particular occasion. The action turns upon the efforts and difficulties of a group of London masons in building a church. Incidentally a number of historical scenes, illustrative of church-building, are introduced. The play, enthusiastically greeted, was first presented in England, at Sadler's Wells; the production included much pageantry, mimetic action, and ballet, with music by Dr. Martin Shaw.

Eliot Publishes Elizabethan Essays 1 January, 1934

Seeks to define and illustrate a point of view toward theElizabeth drama which is different from that of the nineteenth-century tradition.

Revised as Essays On Elizabethan Drama (1956)

Republished as Elizabethan Dramatists (1963)

Eliot Publishes Murder In The Cathedral 1 January, 1935

T. S. Eliot's verse dramatization of the murder of Thomas Becket at Canterbury, winner of the Nobel Prize for Literature.

The Archbishop Thomas Becket speaks fatal words before he is martyred in T. S. Eliot's best-known drama, based on the murder of the Archbishop of Canterbury in 1170. Praised for its poetically masterful handling of issues of faith, politics, and the common good, T. S. Eliot's play bolstered his reputation as the most significant poet of his time.

Eliot Publishes Essays Ancient & Modern 1 January, 1936

A collection of essays grappling with some of the most significant topics of our time, Essays Ancient and Modern reveals Eliot’s thoughts on his literary contemporaries and predecessors, the role of religion in a secular society, and the continuing tradition of the classics in modern education. Astute and erudite, here we see the inner thoughts of one of our greatest minds, articulated in some of his most eloquent and direct prose.

Eliot Publishes Collected Poems 1909-1935 1 January, 1936

Eliot publishes old possum's book of practical cats 1 january, 1939.

The basis for the musical phenomenon Cats, this collection of 14 inviting rhymes — the mixture of the real and the impossible, the familiar and the fantastic — make for a set of poems that no child or adult can possibly resist.

Eliot Publishes The Idea Of A Christian Society 1 January, 1939

These three lectures by the renowned poet and playwright T. S. Eliot address the direction of religious thought toward criticism of political and economic systems. They were originally delivered in March 1939 at Corpus Christi College.

Republished in (1940)

Eliot Publishes The Family Reunion 1 January, 1939

A modern verse play dealing with the problem of man’s guilt and his need for expiation through his acceptance of responsibility for the sin of humanity. “What poets and playwrights have been fumbling at in their desire to put poetry into drama and drama into poetry has here been realized.... This is the finest verse play since the Elizabethans” (New York Times).

Eliot Publishes East Coker 1 January, 1940

Eliot publishes the dry salvages 1 january, 1941, eliot publishes burnt norton 1 january, 1941, eliot publishes points of view/ edited by john hayward 1 january, 1941, eliot publishes the classics and the man of letters 1 january, 1942, eliot publishes the music of poetry 1 january, 1942, eliot publishes little gidding 1 january, 1942, eliot publishes four quartets 1 january, 1943.

The last major verse written by Nobel laureate T. S. Eliot, considered by Eliot himself to be his finest work.

Four Quartets is a rich composition that expands the spiritual vision introduced in “The Waste Land.” Here, in four linked poems (“Burnt Norton,” “East Coker,” “The Dry Salvages,” and “Little Gidding”), spiritual, philosophical, and personal themes emerge through symbolic allusions and literary and religious references from both Eastern and Western thought. It is the culminating achievement by a man considered the greatest poet of the twentieth century and one of the seminal figures in the evolution of modernism.

Eliot Publishes Reunion By Destruction 1 January, 1943

Eliot publishes what is a classic 1 january, 1945, eliot publishes a practical possum 1 january, 1947, eliot's ex-wife, vivien eliot dies 1 january, 1947, eliot publishes on poetry 1 january, 1947, eliot publishes milton 1 january, 1947, eliot publishes selected poems 1 january, 1948.

Chosen by Eliot himself, the poems in this volume represent the poet’s most important work before Four Quartets. Included here is some of the most celebrated verse in modern literature-”The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock,” “Gerontion,” “The Waste Land,” “The Hollow Men,” and “Ash Wednesday”-as well as many other fine selections from Eliot’s early work.

Republished in (1967)

Eliot Publishes Notes Towards The Definition Of Culture 1 January, 1948

The word culture, in recent years, has been widely and erroneously employed in political, educational, and journalistic contexts. In helping to define a word so greatly misused, T. S. Eliot contradicts many of our popular assumptions about culture, reminding us that it is not the possession of a class but of a whole society and yet its preservation may depend on the continuance of a class system, and that a “classless” society may be a society in which culture has ceased to exist.

Surveying the contemporary scene, Mr. Eliot points out that our standards of culture are lower than they were fifty years ago, finds evidence of this decay in every department of human activity, and sees no reason why the decay of culture should not proceed much further. He suggests that culture and religion have a common root and that if one decays the other may die too. He reminds us that “the Russians have been the first modern people to practice the political direction of culture consciously, and to attack at every point the culture of any people whom they wish to dominate.” The appendix includes his broadcasts to Europe, ending with a plea to preserve the legacy of Greece, Rome, and Israel, and Europe’s legacy throughout the last 2,000 years.

Republished in (1949)

Eliot Publishes From Poe To Valéry 1 January, 1948

Eliot wins nobel prize in literature 1 january, 1948, eliot publishes a sermon 1 january, 1948, eliot publishes the undergraduate poems of t.s. eliot 1 january, 1949, eliot publishes the aims of poetic drama 1 january, 1949, eliot publishes the cocktail party 1 january, 1950.

A modern verse play about the search for meaning, in which a psychiatrist is the catalyst for the action. “An authentic modern masterpiece” (New York Post)

Eliot Publishes Poems Written In Early Youth 1 January, 1950

Republished in (1967)

Eliot Wins Tony Award For Best Play: The Broadway Production of "The Cocktail Party" 1 January, 1950

Eliot publishes poetry and drama 1 january, 1951, eliot publishes the value and use of cathedrals in england today 1 january, 1952, eliot publishes an address to members of the london library 1 january, 1952.

Republished in (1953)

Eliot Publishes The Complete Poems And Plays 1 January, 1952

This omnibus collection includes all of the author’s early poetry as well as the Four Quartets, Old Possum’s Book of Practical Cats, and the plays "Murder in the Cathedral", "The Family Reunion", and "The Cocktail Party".

Eliot Publishes American Literature And The American Language 1 January, 1953

Eliot publishes the three voices of poetry 1 january, 1953.

Republished in (1954)

Eliot Publishes The Confidential Clerk 1 January, 1954

The Confidential Clerk was first produced at the Edinburgh Festival in the summer of 1953.

'The dialogue of The Confidential Clerk has a precision and a lightly felt rhythm unmatched in the writing of any contemporary dramatist.' (Times Literary Supplement)

'A triumph of dramatic skill: the handling of the two levels of the play is masterly and Eliot's verse registers its greatest achievement on the stage - passages of great lyrical beauty are incorporated into the dialogue.' (Spectator)

Eliot Publishes Religious Drama: Mediaeval And Modern 1 January, 1954

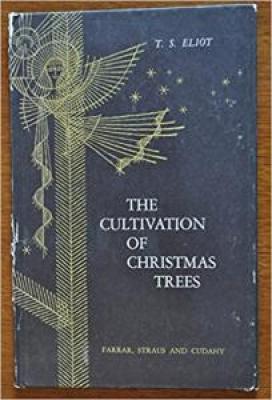

Eliot publishes the cultivation of christmas trees 1 january, 1954.

Republished in (1956)

Eliot Publishes The Literature Of Politics 1 January, 1955

Foreword by Sir Anthony Eden. Text of a lecture delivered at a literary luncheon, organized by the London Conservative Union, at the Overseas League, London, April 19, 1955.

Eliot Publishes The Frontiers Of Criticism 1 January, 1956

Eliot publishes on poetry and poets 1 january, 1957.

T. S. Eliot was not only one of the greatest poets of the twentieth century—he was also one of the most acute writers on his craft. In On Poetry and Poets, which was first published in 1957, Eliot explores the different forms and purposes of poetry in essays such as "The Three Voices of Poetry," "Poetry and Drama," and "What Is Minor Poetry?" as well as the works of individual poets, including Virgil, Milton, Byron, Goethe, and Yeats. As he writes in "The Music of Poetry," "We must expect a time to come when poetry will have again to be recalled to speech. The same problems arise, and always in new forms; and poetry has always before it . . . an ‘endless adventure.'"

Eliot Marries Valerie Fletcher on January 10th 1 January, 1957

Eliot publishes the elder statesman 1 january, 1959.

One of Eliot's plays

Eliot Publishes Geoffrey Faber 1889-1961 1 January, 1961

Eliot publishes collected plays 1 january, 1962, eliot publishes george herbert 1 january, 1962.

T.S. Eliot considered Herbert's religious verse above John Donne's and placed him firmly in the ranks of the great English poets. Peter Porter's new introduction gives a fresh perspective on the poetry of Herbert and on Eliot's study itself.

Eliot Publishes Collected Poems 1909-1962 1 January, 1963

In this volume, one of the most distinguished poets of our century selected all of his poetry through 1962 that he wished to preserve. An event of major literary significance, Collected Poems 1909-1962 was published on T. S. Eliot's seventy-fifth birthday. It offers the complete text of Collected Poems 1909-1935, the full text of "Four Quartets", and several other poems. Winner of the Nobel Prize in Literature, widely honored for his poetry, criticism, essays, and plays, T. S. Eliot exerted a profound influence on his contemporaries in the arts as well as on a great international audience of readers.

Eliot Publishes Knowledge And Experiences In The Philosophy Of F. H. Bradley 1 January, 1964

T. S. Elliot left Harvard during his third year of study in the department of philosophy and went to England. Forty-six years later he authorized the publication of his doctoral dissertation but the book is virtually impossible to find today.

Here we have a reprint of his sympathetic but not entirely uncritial study of the English idealist philosopher F. H. Bradley. Enthusiastic approval came to Eliot at the time from Harvard pragmatist Josiah Royce, who pronounced his writing of philosophy "the work of an expert."

Eliot's critical literary theory was deeply influenced by his early philosophical outlook. This rewarding book provides a potent refutation of the false but frequent claim that Eliot's poetic and critical intelligence had no philosophical writings, making this book indispensable to all literary critics and theorists.

Eliot Publishes To Criticize The Critic And Other Writings 1 January, 1965

These influential essay and lectures by T. S. Eliot span nearly a half century—from 1917, when he published The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock, to 1961, four years before his death. With the luminosity and clarity of a first-rate intellect, Eliot considers the uses of literary criticism, the writers who had the greatest influence on his own work, and the importance of being truly educated.

T. S. Eliot dies. 4 January, 1965

T. S. Eliot dies January 4th, 1965. As per Eliot’s wishes his remains were interred at St. Michael’s church in East Coker, Somerset, England.

T. S. Eliots ashes are interred. 14 January, 1965

T. S. Eliot's ashes are interred at St. Michael's Church in East Coker.

Eliot Publishes The Waste Land: A Facsimile And Transcript Of The Original Drafts Including The Annotations Of Ezra Pound / edited by Valerie Eliot 1 January, 1971

Each facsimile page of the original manuscript is accompanied here by a typeset transcript on the facing page. This book shows how the original, which was much longer than the first published version, was edited through handwritten notes by Ezra Pound, by Eliot’s first wife, and by Eliot himself. Edited and with an Introduction by Valerie Eliot; Preface by Ezra Pound.

Eliot Publishes Selected Prose Of T.S. Eliot/edited by Frank Kermode 1 January, 1975

Thirty-one essays-categorized as “essays in generalization,” “appreciations of individual authors,” and “social and religious criticism”- written over a half century. This volume reveals Eliot’s original ideas, cogent conclusions, and skill and grace in language. Edited and with an Introduction by Frank Kermode; Index. Published jointly with Farrar, Straus & Giroux.

Eliot Wins Two Tony Awards For His Poems Used In The Musical "Cats" 1 January, 1983

Eliot publishes the letters of t.s. eliot. vol. 1, 1898-1922/edited by valerie eliot 1 january, 1988.

Included her are all the significant extant letters Eliot wrote up to age 24 as well as many letters written to him by his family, friends, and contemporaries. There are insights into his struggle to earn a living, care for a wife who was frequently ill, edit a magazine, and become known as a critic and poet. And through the correspondence emerges a memorable view of the social and intellectual milieu before and after World War I.

Valerie Eliot has written a detailed introduction, provided annotations and commentary, and selected numerous photographs of Eliot and his world, many of which have never been shown publicly. All these elements combine to create an exceptional portrait of Eliot in the early years of his personal and professional development -- the closest approximation readers will ever have to an autobiography of the poet.

Eliot Publishes The Varieties of Metaphysical Poetry: The Clark Lectures At Trinity College, Cambridge, 1926, And The Turnbull Lectures At The Johns Hopkins University, 1933/edited by Ronald Schuchard 1 January, 1993

Republished in (1994)

Eliot Publishes Inventions Of The March Hare: Poems 1909-1917/ edited by Christopher Ricks 1 January, 1996

This extraordinary trove of previously unpublished early works includes drafts of poems such as “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock” as well as ribald verse and other youthful curios. “Perhaps the most significant event in Eliot scholarship in the past twenty-five years” (New York Times Book Review). Edited by Christopher Ricks.

Eliot Publishes The Waste Land: Authoritative Text, Contexts, Criticism 1 January, 2001

Eliot publishes the annotated waste land/edited by lawrence rainey 1 january, 2005.

Newly revised and in paperback for the first time, this definitive, annotated edition of T. S. Eliot’s The Waste Land includes as a bonus all the essays Eliot wrote as he was composing his masterpiece. Enriched with period photographs, a London map of cited locations, groundbreaking information on the origins of the work, and full annotations, the volume is itself a landmark in literary history.

Eliot Publishes The Letters Of T.S. Eliot. Vol.2, 1923-1925/edited by Valerie Eliot and Hugh Haughton 1 January, 2009

The volume offers 1,400 letters, charting Eliot's journey toward conversion to the Anglican faith, as well as his transformation from banker to publisher and his appointment as director of the new publishing house Faber & Gwyer. The prolific and various correspondence in this volume testifies to Eliot's growing influence as cultural commentator and editor.

1962 Oil Painting by Sir Gerald Kelly.

National Portrait Gallery. Smithsonian Institution,

Washington D.C.

Headstone for T. S. Eliot.

The quote reads: "In my beginning is my end, In my end is my beginning".

Of your charity

Pray for the repose

Of the soul of

THOMAS STEARNS ELIOT

26th. September 1888- 4th. January 1965

Wyndham Lewis -- "T. S. Eliot"

Durban Art Gallery, South Africa

- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Acquisition

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Media

- Music and Religion

- Music and Culture

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Lifestyle, Home, and Garden

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Medical Ethics

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Security

- Computer Games

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Ethics

- Business Strategy

- Business History

- Business and Technology

- Business and Government

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic History

- Economic Systems

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Political Theory

- Politics and Law

- Public Policy

- Public Administration

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Developmental and Physical Disabilities Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

T.S. Eliot and Early Modern Literature

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

This book, for the first time, considers the full imaginative and moral engagement of one of the most influential poets of the twentieth century, T.S. Eliot, with the Early Modern period of literature in English (1580–1630). This engagement haunted Eliot’s poetry and critical writing across his career, and would have a profound impact on subsequent poetry across the world, as well as upon academic literary criticism and wider cultural perceptions. To this end, the book elucidates and contextualizes several facets of Eliot’s thinking and its impact: through establishment of his original and eclectic understanding of the Early Modern period in relation to the literary and critical source materials available to him; through consideration of uncollected and archival materials, which suggest a need to reassess established readings of the poet’s career; and through attention to Eliot’s resonant formulations about the period in consequent literary, critical, and artistic arenas. To the end of his life, Eliot had to fend off the presumption that he had, in some way, ‘invented’ the Early Modern period for the modern age. Yet the presumption holds some force—it is famously and influentially an implication running through Eliot’s essays on that earlier period, and through his many references to its writings in his poetry, that the Early Modern period formed the most exact historical analogy for the apocalyptic events (and consequent social, cultural, and literary turmoil) of the first half of the twentieth century. ‘T.S. Eliot and Early Modern Literature’ gives a comprehensive sense of the vital engagement of this self-consciously modern poet with the earlier period he always declared to be his favourite.

Signed in as

Institutional accounts.

- GoogleCrawler [DO NOT DELETE]

- Google Scholar Indexing

Personal account

- Sign in with email/username & password

- Get email alerts

- Save searches

- Purchase content

- Activate your purchase/trial code

Institutional access

- Sign in with a library card Sign in with username/password Recommend to your librarian

- Institutional account management

- Get help with access

Access to content on Oxford Academic is often provided through institutional subscriptions and purchases. If you are a member of an institution with an active account, you may be able to access content in one of the following ways:

IP based access

Typically, access is provided across an institutional network to a range of IP addresses. This authentication occurs automatically, and it is not possible to sign out of an IP authenticated account.

Sign in through your institution

Choose this option to get remote access when outside your institution. Shibboleth/Open Athens technology is used to provide single sign-on between your institution’s website and Oxford Academic.

- Click Sign in through your institution.

- Select your institution from the list provided, which will take you to your institution's website to sign in.

- When on the institution site, please use the credentials provided by your institution. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

- Following successful sign in, you will be returned to Oxford Academic.

If your institution is not listed or you cannot sign in to your institution’s website, please contact your librarian or administrator.

Sign in with a library card

Enter your library card number to sign in. If you cannot sign in, please contact your librarian.

Society Members

Society member access to a journal is achieved in one of the following ways:

Sign in through society site

Many societies offer single sign-on between the society website and Oxford Academic. If you see ‘Sign in through society site’ in the sign in pane within a journal:

- Click Sign in through society site.

- When on the society site, please use the credentials provided by that society. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

If you do not have a society account or have forgotten your username or password, please contact your society.

Sign in using a personal account

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members. See below.

A personal account can be used to get email alerts, save searches, purchase content, and activate subscriptions.

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members.

Viewing your signed in accounts

Click the account icon in the top right to:

- View your signed in personal account and access account management features.

- View the institutional accounts that are providing access.

Signed in but can't access content

Oxford Academic is home to a wide variety of products. The institutional subscription may not cover the content that you are trying to access. If you believe you should have access to that content, please contact your librarian.

For librarians and administrators, your personal account also provides access to institutional account management. Here you will find options to view and activate subscriptions, manage institutional settings and access options, access usage statistics, and more.

Our books are available by subscription or purchase to libraries and institutions.

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Rights and permissions

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

T. S. Eliot on Tradition, Orthodoxy, and Ancient Cheese

Someone said: “The dead writers are remote from us because we know so much more than they did.” Precisely, and they are that which we know. ―“Tradition and the Individual Talent” [1]

“How can they whip cheese?” ― Death of a Salesman [2]

Speaking at a conference on “T. S. Eliot and the Literary Tradition” in Eliot’s centenary year (1988), the eminent critic Hugh Kenner discussed at some length A. L. Maycock’s Nicholas Ferrar of Little Gidding , regretting the fact that it was long out of print. [3] Little Gidding, the site of a small Anglican religious community founded by Ferrar in 1620 as an experiment in the devotional life, was visited by poets George Herbert and Richard Crashaw, and on three occasions by King Charles, the last alone at night after the Royalist defeat at Nasby. It became the site of spiritual pilgrimage and so continues today. Eliot visited in 1936 and made it the locale of his last major poem, the fourth of Four Quartets . After Kenner’s lecture, I was pleased to inform him that the book had recently been reprinted. [4] Tongue-in-cheek, he ventured that Eliot’s interest in Little Gidding was likely stimulated by its proximity to Stilton, the market town of one of his favorite English cheeses.

Seemingly irreverent—in view of the community’s renown for fostering devout religious observance and prayer, and Eliot’s interest in its role in English history and religious tradition—Kenner’s jest was actually more in keeping with the conference theme than it might first seem. There “where prayer has been valid,” and where “on a winter’s afternoon, in a secluded chapel / History is now and England,” [5] Little Gidding represented for Eliot in literary and religious terms what England’s “Ancient Cheeses” (as he referred to them in a letter to the Times ) represented in the cultural life of society. [6] In a letter to another paper, he said that Canadian Trappist monks, makers of a Port Salut, “like their cheese, are the product of ‘a settled civilisation of long standing,’” but he feared that “there is little demand for either.” [7]

A Living Tradition

In Eliot’s view, literary traditions can suffer the same fate as the culturing of cheeses, and effort may be needed to revive them. But whereas in the case of the latter, “nothing less is required than the formation of a Society for the Preservation of Ancient Cheeses,” as he drolly wrote to the Times , revival of traditional literature—especially of poetry—will take a critical reappraisal of the concept of tradition itself.

His opening manifesto, “Tradition and the Individual Talent” (1919), set forth his idea of what a viable literary tradition consists of. It would also prove to be an apologia for the kind of poetry he was writing: poetry that shocked readers in its apparent defiance of every rule of poetic tradition, yet that—once the dust began to settle (a process not yet completed in the century since “The Waste Land” appeared in 1922)—was found to be rooted in that tradition, and in its method a protracted exercise in reviving it.

First, however, he cleared the ground of all-too-common misuses of the word, according to which “traditional” is either a term of censure of a poet’s work or at best “vaguely approbative, with the implication . . . of some pleasing archaeological reconstruction.” (Little has changed: in a recent syndicated crossword, “Traditional” was the clue for “Old School.”) Indeed, Eliot insists,

If the only form of tradition, of handing down [Latin trādere , “to hand over”], consisted in following the ways of the immediate generation before us in a blind or timid adherence to its successes, “tradition” should positively be discouraged. (3–4)

Awareness of a living tradition, he argues, is not evident in the poets of the generation prior to the Great War, whose “pleasing anthology pieces” were often sentimental, escapist, and static because unconnected to the poet’s greatest resource, the main current of European poetry. [8] This tradition, he insists, “cannot be inherited, and if you want it you must obtain it by great labour.” It can be acquired only in a library by anyone aspiring to be a poet into adulthood. It involves what Eliot calls “the historical sense,” the perception of the existing monuments of literature as “an ideal order among themselves, which is modified by the introduction of the new (the really new) work of art among them. . . . [It is a] conformity between the old and the new.” This sense is not for the timid: it “compels” the poet, the individual talent,

to write not merely with his own generation in his bones, but with a feeling that the whole of the literature of Europe from Homer and within it the whole of the literature of his own country has a simultaneous existence and composes a simultaneous order. [9]

Consciousness of the presence of the past—“not of what is dead, but of what is already living” (11)—is what makes a writer traditional. Its corollary is the awareness that new works must be judged in relation to the standard exemplified in works of past writers, a measurement of the new by the old and vice-versa—not of better or worse, for “art never improves,” but of what “conforms,” what belongs , and what does not.

Willie Loman—the forlorn salesman of a past for whom and for which, he discovers, the present has little demand—senses that the whipped cheese his wife bought does not conform, that it portends the passing not only of the cheese he had naively assumed was a permanent product of a “settled civilisation” but (more ominously) of that civilization itself. The analogy of poet and peasant—for Willie is an urban hand-to-mouth peasant—wears thin at this point, for he is a consumer , not a maker of the cheese whose imminent demise he foresees, whereas a poet (Greek “maker”) is the creator of poems. Yet both function as discerning critics in their respective traditions; whether as creators or consumers, they employ the historical sense in the task of evaluation.

“Criticism,” Eliot says in “The Function of Criticism” (1923), “must always profess an end in view, . . . the elucidation of works of art and the correction of taste.” [10] The tools available to poet-critic and critical reader are the same: comparison and contrast, and “a very highly developed sense of fact,” a qualification that develops slowly and whose “complete development means perhaps the very pinnacle of civilisation” (19). Eliot’s early criticism put these tools to work revolutionizing the literary scene and giving rise to what developed, particularly in America, into the “New Criticism,” a school whose founding was credited to him, somewhat to his embarrassment.

His practice of the aesthetic criticism he first advocated is best illustrated in his first collection of essays, The Sacred Wood (1920), in which he addressed “the problem of the integrity of poetry, with the repeated assertion that when we are considering poetry we must consider it primarily as poetry and not another thing.” [11] Thus his insistence that when we read, we first of all bring to bear a discerning grasp of the poetry of the living past—the “existing monuments”—and the “sense of fact” that pays close attention to the text, elucidating rather than interpreting it as a document of the author’s personality and biography, as his contemporary readers and critics tended to do.

An illustration of Eliot’s critical method applied to the culinary rather than the literary arts is found in his evaluation of an actual cheese. Kenner relates in whimsical detail an occasion when the poet-critic ordered Stilton for a dinner guest at the Garrick Club, prefacing the account with his admonition on the use of critical tools, written about the same time as the “Tradition” essay:

(“Analysis and comparison, methodically, with sensitiveness, intelligence, curiosity, intensity of passion, and infinite knowledge: all these are necessary to the great critic.”) With the side of his knife blade he commenced tapping the circumference of the cheese, rotating it, his head cocked in a listening posture. . . . He then tapped the inner walls of the crater. He then dug about with the point of his knife amid the fragments contained by the crater. He then said, “Rather past its prime. I am afraid I cannot recommend it.” [12]

The Stilton conformed to tradition but proved the victim of time, as all farm products may.

Poems too may suffer from uncritical reading or neglect, but, unlike spoiled foods, they can be rescued by reading such as Eliot urged. Some will be seen in new relations to the existing monuments; some unknown works will be welcomed as belonging. As with poems, so with cheese: “There cannot be too many kinds of cheese”—his letters mention eighteen—“and variety is as important with cheese as with anything else. . . . [P]art of the reason for living is the discovery of new cheeses.” [13]

An Extra-Human Measure

Eliot’s argument thus far is largely an aesthetic one. In “The Function of Criticism,” he says that the literature of the world, of Europe, of a country, is not to be seen as “a collection of the writings of individuals, but as ‘organic wholes,’ as systems in relation to which . . . individual works of literary art, and the works of individual artists, have their significance. There is accordingly something outside of the artist to which he owes allegiance, a devotion to which he must surrender and sacrifice himself” if he aspires to new creation. Literary tradition, we have seen, stands as the “something outside.” [14] But in this essay, he introduces a new note.

In a disputation with his lifelong literary-religious antagonist and friend John Middleton Murry on the subject of Classicism and Romanticism, Eliot responds to Murry’s attack on the former and upon the religion Eliot was then in the course of embracing. “Catholicism,” Murry says in derogation, “stands for the principle of unquestioned authority outside the individual; that is also the principle of Classicism in literature,” a description in which Eliot concurs. But writers, Murry goes on, “inherit no rules from their forebears; they inherit only this: a sense that in the last resort they must depend upon the inner voice. . . . The man who truly interrogates himself will ultimately hear the voice of God” (15–16).

Eliot no doubt heard in Murry’s profession of faith in the “inner voice” an echo of the Unitarianism in which he had been raised—“outside the Christian Fold,” as he put it—and from which he had drifted away, first toward Buddhism, then toward Anglo-Catholicism. Declaring himself deaf to the inner voice, Eliot says that those who support Classicism “believe that men cannot get on without giving allegiance to something outside themselves,” something “which may provisionally be called truth” (15, 22). He later wrote,

The issue is really between those who . . . make man the measure of all things , and those who would find an extra-human measure. There are those who find this measure in a revealed religion, and those who . . . look for it without pretending to have found it. [15]

The Complication of Belief

Paramount among the literary monuments for which Eliot early developed deep admiration was the poetry of Dante, a devotion that raised the thorny question of the poet’s religious and philosophical beliefs. While Dante emerged for him as “the most universal of poets in the modern languages,” his reading of the Divine Comedy with a translation while he was a Harvard undergraduate was prominent among the influences leading him toward Christianity. Having begun by assigning “the whole of the literature of Europe from Homer” onward as required reading for poet, critic, and discerning reader, in “Dante” (1929) he wrestled with the fact that what Dante meant to him was not only a matter of aesthetics, important though that was. For the medieval philosophy Dante believed and made use of—particularly that of Aquinas—struck him as the truth, and Beatrice’s statement, “ la sua voluntade è nostra pace ” (“in his will is our peace,” Par. 3.85), seemed to him to be “ literally true.” Acknowledging that his appreciation of Dante was enhanced by his sharing the beliefs of the poet, he also attempted (by invoking Coleridge’s “suspension of disbelief”) to affirm the nonbeliever’s ability to understand and appreciate it too:

My point is that you cannot afford to ignore Dante’s philosophical and theological beliefs . . . but that on the other hand you are not called upon to believe them yourself. . . . For there is a difference . . . between philosophical belief and poetical assent . . . . If you can read poetry as poetry, you will “believe” in Dante’s theology exactly as you believe in the physical reality of his journey; that is, you suspend both belief and disbelief. [16]

The problem with this approach to the question of belief is that it resembles I. A. Richards’s psychological theory of value, which holds that—unlike science, whose statements are matters of truth or error—poetry consists of “pseudo-statements” and that questions of its truth or falsity are irrelevant, its sole purpose being the efficient organization of our conflicting interests by means of “provisional acceptances.” Eliot rejected Richards’s claim that in “The Waste Land” he effected “a complete severance between his poetry and all beliefs,” and pilloried his claim that the poetry of pseudo-statements is, as Matthew Arnold before him had hoped, “capable of saving us.” This, Eliot maintained, is tantamount to saying that “the wall-paper will save us when the walls have crumbled.”

Yet, wary as he was of Richards’s “poetry of unbelief,” according to which “the difference between Good and Evil becomes . . . only the ‘difference between free and wasteful organization,’” [17] he insisted that “if you deny the theory that full poetic appreciation is possible without belief in what the poet believed, you deny the existence of ‘poetry’ as well as ‘criticism.’” Pushed to their extremes, he admits, both this theory and the contradictory view that “full understanding must identify itself with belief” are heretical. “Orthodoxy can only be found in such contradictions, though it must be remembered that a pair of contradictions may both be false, and that not all pairs of contradictions make up a truth.” [18]

Orthodoxy and a Dual Theory of Value

The general concept of orthodoxy Eliot advanced in “Dante” to come to grips with what he called “the complication of belief” was not invented for the purpose; in fact, it had been evolving in his thinking since he studied under Irving Babbitt at Harvard. Babbitt proposed a unipolar model of adherence to a central truth, centripetal movement toward which constitutes orthodoxy, and centrifugal movement from which is heresy. In Eliot’s model, truth is elliptical, having two poles with plausible but contradictory ideas, propositions, or allegiances held in necessary tension. Either of them taken too far becomes heretical. Thus, for example, Classicism and Romanticism may coexist, each checking the other’s tendencies to excess in a productive balance. But far from being Eliot’s invention, the model is one of ancient theological standing.

In its church councils, Western Christianity dealt with heresies concerning the natures of Christ, affirming that he is both God and man, with a divine nature and a human nature, each distinct yet unified. This affirmation has constituted christological orthodoxy for centuries and surely underlies Eliot’s concept, which he employed in various contexts in addition to literary criticism—religion, history, politics, and social theory. Broadly speaking, we might say that for Eliot, “orthodoxy” was a neutral term for the formal structure of thought about any topic; “tradition”—secular, religious, or in some combination—his term for substantive content under scrutiny.