- Newsletters

Site search

- Israel-Hamas war

- 2024 election

- Solar eclipse

- Supreme Court

- All explainers

- Future Perfect

Filed under:

We’ve worried about overpopulation for centuries. And we’ve always been wrong.

Earth’s population trends, explained.

Share this story

- Share this on Facebook

- Share this on Twitter

- Share this on Reddit

- Share All sharing options

Share All sharing options for: We’ve worried about overpopulation for centuries. And we’ve always been wrong.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/65049798/GettyImages_1068932710.0.jpg)

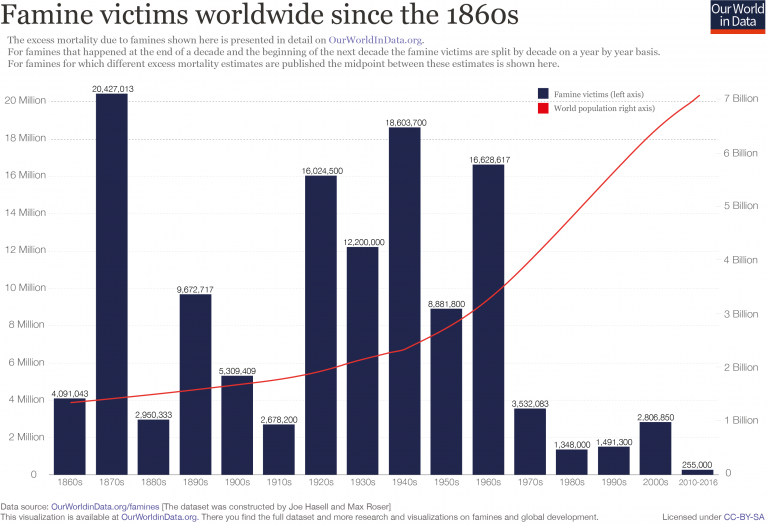

For nearly all of human history, there haven’t been that many of us. Around the year zero, Earth’s population is estimated to have been 190 million . A thousand years later, it was probably around 250 million.

Then the Industrial Revolution happened, and human population went into overdrive. It took hundreds of thousands of years for humans to hit the 1 billion mark, in 1800. We added the next billion by 1928. In 1960, we hit 3 billion. In 1975, 4 billion.

That sounds like the route to an overpopulation apocalypse, right? To many midcentury demographers, futurists, and science fiction writers, it certainly predicted one . Extending the timeline, they saw a nightmarish future ahead for humanity: human civilizations constantly on the brink of starvation, desperately crowded under horrendous conditions, draconian population control laws imposed worldwide.

Sign up for the Meat/Less newsletter course

Want to eat less meat but don’t know where to start? Sign up for Vox’s Meat/Less newsletter course. We’ll send you five emails — one per week — full of practical tips and food for thought to incorporate more plant-based food into your diet.

Stanford biologist Paul Ehrlich wrote in his best-selling 1968 book The Population Bomb , “In the 1970’s, hundreds of millions of people will starve to death” because of overpopulation. (Later editions modified the sentence to read “In the 1980’s.”)

None of that ever came to pass.

The world we live in now, despite approaching a population of nearly 8 billion, looks almost nothing like the one doomsayers were anticipating. Starting in the 19th century in Britain and reaching most of the world by the end of the 20th century, birthrates plummeted — mostly because of women’s education and access to contraception, not draconian population laws.

Subscribe to Today, Explained

Looking for a quick way to keep up with the never-ending news cycle? Host Sean Rameswaram will guide you through the most important stories at the end of each day.

Subscribe on Apple Podcasts , Spotify , Ove r cast , or wherever you listen to podcasts.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19104938/VOX_todayexplained_twitter_profilephoto_1.png)

In wealthy societies where women have opportunities outside the home, the average family size is small; in fact, it’s below replacement level (that is, on average, each set of two parents has fewer than two children, so the population shrinks over time). Called the demographic transition, it is one of the most important phenomena for understanding trends in global development.

There’s still significant debate among population researchers about the extent of the sea change in population trends. Researchers disagree on whether global populations are currently on track to start declining by midcentury. There’s also disagreement on what the ideal global population figure would be, or whether it’s morally acceptable to aim for such a figure.

While academic research seeks to nail down these questions, it’s important to be clear what is consensus among researchers. All around the world, birthrates are declining rapidly. Global population growth has been slowing since the 1960s, and global population will almost certainly start to decline. The world is absolutely not, as is sometimes claimed , on track to have 14 billion people by 2100.

Our projections around population are used to make global health and development policy. They’re critical for planning, especially about climate change. Fears of overpopulation sometimes turn into hostility to immigrants, those who choose to have large families, and countries in an earlier stage of their population transition. Having an informed conversation about population is crucial if we are to get humanity’s future right.

How we figure out population trends

There are about 7.7 billion people alive today. But that number’s not as certain as you might think.

To understand why, you just have to think about the US census. The federal government is mandated by the Constitution to conduct a count of its population every 10 years. It is a big, industrialized country with modern technology and lots of resources. In 2010, it is estimated that our count of our nation of 300 million - plus was off by only about 36,000 people — or only 0.01 percent . That’s pretty good (if researchers’ estimate of the errors is reliable)! But that decent overall count masks some bigger errors: The same analysis estimates the black population was undercounted by 2 percent .

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19038108/GettyImages_1144610283.jpg)

In many parts of the world, population data is much less reliable. Countries can have incentives both to overcount (in regions vying to demonstrate increased need for aid, say) and undercount their populations (perhaps to disfavor a disliked minority group). Even without any efforts to manipulate the numbers, it’s expensive and challenging to accurately estimate populations.

If estimating populations is hard, estimating population trends is much harder. The demographers who estimated a ruinous, extremely fast growth trajectory were wrong, but how could they have known that the trend they were observing was about to reverse?

Today, it’s still challenging to confidently estimate population sizes. But some organizations and institutions have done surprisingly well.

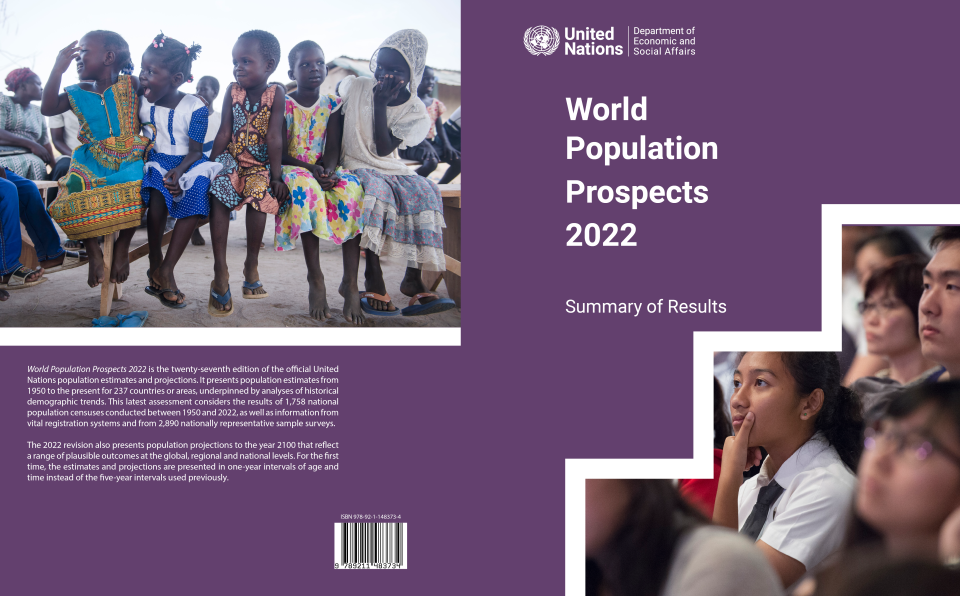

The United Nations publishes an estimate annually of the most likely population trend and then “high” and “low” fertility scenarios. These reports have turned out to be surprisingly accurate.

Since the UN has been making population projections since 1950, and since it publishes revisions and corrections to those projections over time, we can compare its initial estimates to the revisions and corrections. Researcher Nico Keilman did that, and found that the UN has an impressively accurate track record at population predictions. Their estimates of world population by 1990, published in 1950, were off by about 12 percent.

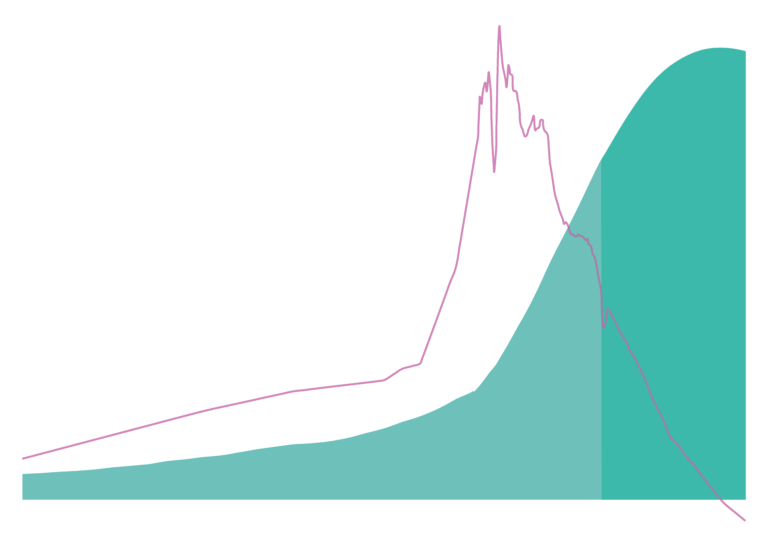

They quickly got better: By 1960, those estimates were off by only about 2 percent. Since then, the UN has pegged global population growth rates pretty precisely. Here’s a graph of real population growth over time, compared to population growth as the UN projected it:

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/18963644/Screen_Shot_2019_08_12_at_12.48.21_PM.png)

So up to the present day, the UN has been highly reliable in predicting global population trends. Its prediction now is that the world population will continue to increase until 2100, when it will peak at 11.2 billion and then start declining.

Some experts don’t buy the UN’s estimates

Nonetheless, they have their critics. Other analysts have argued that fertility will in fact fall more dramatically than the UN estimates even in its “low-fertility scenarios.” One such critic is Norwegian academic Jorgan Randers , who studies climate strategy. “The world population will never reach nine billion people,” he has claimed . “It will peak at 8 billion in 2040, and then decline.”

Demographers at Vienna’s International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis agree: They’ve estimated the population will stabilize by midcentury and then decline . These models expect fertility in low-income countries to fall faster than the UN projects it will.

Some of the differences are simply methodological. How the fastest-growing countries in the world are modeled has a huge impact on how global population models come out overall, so small differences in expectations in those countries can significantly shift overall results.

But much of the difference in projections may be rooted in disagreement over another question: how many people the world can handle. Adherents to lower-population models often call the UN projections “ apocalyptic ” — fearing that they’d make climate change impossible to manage. Demographer Wolfram Lutz has characterized the UN’s model as the “population explosion” model (even though it projects a leveling off and declining population). Many of them have turned away from what they perceive as excessively “pessimistic” models toward ones that project a much faster-declining human population.

The challenges the pessimists anticipate aren’t imaginary. With our current technology, of course, we don’t know how to provide 11 billion people a good standard of living sustainably. But technology — including green and sustainable technology — has been rapidly improving for a long time. The year 2100 is more than 80 years from now, and almost all the technology that we have today to make civilization sustainable sounded like wild science fiction 80 years ago.

A global population peaking at 11 billion need not be an apocalypse or cause for pessimism, but it does pose challenges that we’ll need to rise to.

While the UN deserves a lot of credit for how accurate they’ve been so far, past performance is obviously no guarantee of future accuracy. There’s room for their estimates to be importantly wrong in the future — in either direction.

It’s fairly straightforward to accurately predict the population in 20 years just by assuming that existing trends will continue. It’s much harder to predict sea changes in habits around the world. If, for example, climate change drives currently developed countries back into poverty and drives their birthrates back up, the estimates are poorly equipped to account for that. On the other hand, if more reliable contraceptives are developed and virtually end unintended pregnancies the world over, birthrates could fall much faster than predicted.

Nonetheless, this disagreement obscures a lot of agreement. Randers might call the UN estimates “apocalyptic,” but they’re incredibly optimistic compared to estimates at midcentury. Everyone now agrees that without any totalitarian or coercive measures, populations will start declining; the big disagreement is simply when.

It was not at all obvious that the world would turn out this way, and it’s tremendously significant that it has. It implies both good things — that coercive population controls will never be necessary — and concerning ones, like that societies will age and have a shrinking workforce. But on the whole, we are much better positioned for sustainable growth than it looked in 1950, and the fall in rich-country birthrates is why.

Demographic transition, explained

The big thing we know now about population that was unclear in the mid-20th century is something called the “demographic transition.” In its simplest form, it’s the principle that when societies get wealthy and child mortality falls, people tend to start having less children.

The connection between societies growing wealthier and people desiring smaller families is pretty straightforward. In richer societies, people do not need their kids to do labor and support the family, and they typically invest money and other resources in their kids, to give them the best shot possible at a decent life.

The connection between drops in child mortality and smaller desired family sizes is less obvious. Indeed, at first, when child mortality falls, the population shoots up, as people are still having lots of kids, but more of them survive to adulthood.

That produces a rapid increase in population. That was the state of the world in the 1960s, and some parts of the world are still in that state now. But then, overall growth rates started to fall.

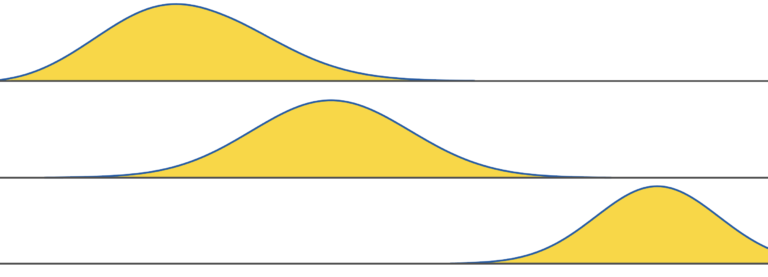

Let’s pull back here and get into the weeds a bit. Demographers think of this process as occurring in five stages. First, birthrates are high but so are death rates, and the population is low but stable (when child mortality is high, people have lots of children to reduce uncertainty). Then, in the second stage, technology helps more kids survive to adulthood. Birthrates remain high, and the population grows rapidly: for one or two generations.

In the third stage, birthrates start to decline, driven by increased certainty about children’s survival, women’s rights, the dynamics of rich economies (where children are no longer an economic asset), and other factors. In the fourth stage, birthrates fall and the population stabilizes. It’s a little unclear where we’ll go from there (in the fifth stage): Populations might shrink due to below-replacement reproduction, or stabilize, or slowly grow.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/18963549/Screen_Shot_2019_08_12_at_12.23.51_PM.png)

What does this demographic transition look like in action? In the US in 1900, the average woman had 3.85 children , and 0.89 children died before age 5 (the child mortality rate was 20 percent), leaving three surviving children on average. Today, the average woman has 1.9 children , with an 0.7 percent child mortality rate.

People used to think that ending child mortality would lead to a dramatic swell in global populations, and it does, in Stage 2 of the above chart, where death rates fall and birthrates remain high. But then in every country yet studied, birthrates eventually end up falling too.

Some of the best research into the demographic transition was published in 1989 by British researchers Anthony Wrigley and Roger Schofield. As the first country to have the Industrial Revolution, Britain was the first to have the demographic transition. Thanks to the state church, Britain also had unusually good birth and death records.

Here’s how the demographic transition looked in Britain:

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/18963575/Screen_Shot_2019_08_12_at_12.29.09_PM.png)

Today, most developed countries have joined Britain on the right end of that graph, with low birthrates and low death rates. Other countries, like Niger and Mali, are still in the middle stage, where death rates are falling but birthrates haven’t yet followed suit.

That adds up to an overall global trend of a population that is still increasing, but it is increasing more slowly than ever.

It’s a reality that hasn’t quite penetrated public consciousness yet. Public conversations are often still consumed by fear that the population is spiraling beyond what the world can support.

The popular 2013 environmentalist book Ten Billion reports still-growing population numbers without discussing the underlying trends towards leveling off and then falling, and concludes, “Every which way you look at it, a planet of 10 billion looks like a nightmare.” Widely published excerpts don’t mention that the population is expected to start falling again either before or shortly after that “nightmare” milestone is reached.

Articles about population growth sometimes mention when we’re expected to hit 9 billion or 10 billion, and then ask, “So is it time for all countries to turn to drastic population control in order to sustain life on Earth, or is it a violation of human rights, no matter what?” without mentioning that populations are expected to decline on their own, no coercion required.

It’s a fear that sometimes has racial and xenophobic components: European white nationalists spread panic over declining white birthrates, while others express fears that poor populations, still growing, will crowd out rich ones. But birthrates are declining in poor countries, too, and look likely to continue to do so as they rapidly get richer. The trend that reached Europe first has since swept the rest of the world and shows no signs of stopping.

Calls to have few or no children to fight climate change are common , with prominent figures such as Miley Cyrus and Prince Harry endorsing them. The underlying assumption is often that we’re on a runaway path to an exploding population. This misses a couple of key facts about population trends: First, the population will decline even if everyone who wants children has them.

Second, opposing children is not a good way to fight climate change. As Lyman Stone wrote for Vox, big changes in how the developed world produces power are what’s needed, and they matter dramatically more than population does. “Lowering US carbon intensity by about a third, to around the level of manufacturing-superpower Germany today, has a bigger effect than preventing 100 million Americans from existing,” Stone argued .

In other words, if we don’t transition to better energy sources, we’re doomed no matter how much we shrink our numbers, and if we do, we could actually sustain a significantly increased population.

What we think we know about population growth in the upcoming century

There’s a lot of agreement between the UN and its critics when it comes to population forecasts. Both sides agree that fertility rates fall as countries get richer, and that even the poorest countries in the world are rapidly getting richer. Both agree that population will peak, and then start to decline.

Both agree that we’re not yet at the peak, but that the Earth’s population will never again double, barring some dramatic technological or cultural shift that fundamentally changes how humans live. Under a wide range of estimates, birthrates will remain below replacement in rich countries, and poor countries will continue to get wealthier and to have fertility patterns that are more similar to those in wealthy countries.

As for their disagreements, they’ll be resolved by the real-world data soon enough. For the UN’s mainline estimate of how these trends will continue into the future, it assumes that these trends will continue at approximately the pace they’ve kept through the past several decades.

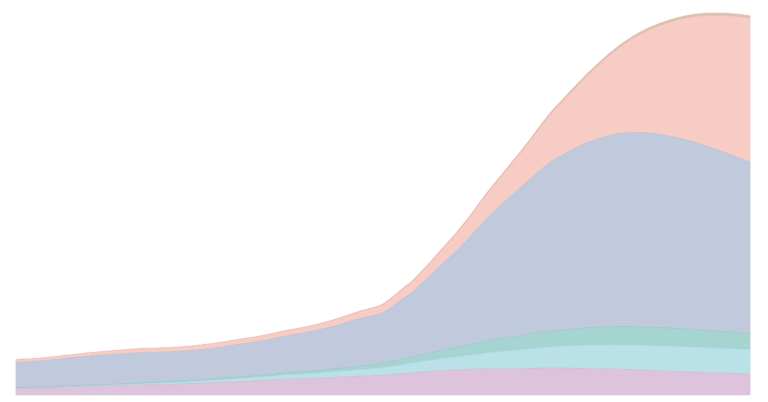

Here is the 2019 UN population forecast:

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/18963687/Screen_Shot_2019_08_12_at_12.59.49_PM.png)

The red lines reflect the UN’s predicted trajectories; the UN is 95 percent confident that population will fall between the two dotted red lines. The lower side of 95 percent confidence interval has global population peaking in 2070 and falling slowly from there; the upper side has population approaching 13 billion and still increasing in 2100.

The blue lines reflect the UN’s projection of how population numbers would shake out if birthrates were 0.5 children higher or lower. The total global birthrate is 2.4 births per woman today. The lower blue line is closest to the trajectory argued for by the European researchers who consider the UN pessimistic; it shows population peaking around 2050 and falling from there.

Under the mainline UN estimates, global population will grow for the rest of this century, but slowly, and this will be the last century with a growing population. The UN has an impressive track record in this area, but some European analysis groups think that the UN is estimating fertility that’s higher than realistic, and that population numbers will fall much sooner. It should be clear by 2030 who is correct.

Sign up for the Future Perfect newsletter. Twice a week, you’ll get a roundup of ideas and solutions for tackling our biggest challenges: improving public health, decreasing human and animal suffering, easing catastrophic risks, and — to put it simply — getting better at doing good.

Will you support Vox today?

We believe that everyone deserves to understand the world that they live in. That kind of knowledge helps create better citizens, neighbors, friends, parents, and stewards of this planet. Producing deeply researched, explanatory journalism takes resources. You can support this mission by making a financial gift to Vox today. Will you join us?

We accept credit card, Apple Pay, and Google Pay. You can also contribute via

Next Up In Future Perfect

Sign up for the newsletter today, explained.

Understand the world with a daily explainer plus the most compelling stories of the day.

Thanks for signing up!

Check your inbox for a welcome email.

Oops. Something went wrong. Please enter a valid email and try again.

It’s impossible to be neutral about Taylor Swift

Tell the truth about Biden’s economy

Jontay Porter’s lifetime NBA ban highlights the risks of sports gambling

Why USC canceled its pro-Palestinian valedictorian

Is the new push to ban TikTok for real?

The history of Arizona’s Civil War-era abortion ban

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- BOOK REVIEW

- 04 April 2022

- Correction 07 April 2022

Global population is crashing, soaring and moving

- Josie Glausiusz 0

Josie Glausiusz is a science journalist and author in Israel. Twitter: @josiegz

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

8 Billion and Counting: How Sex, Death, and Migration Shape Our World Jennifer D. Sciubba W. W. Norton & Company (2022)

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

24,99 € / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 51 print issues and online access

185,98 € per year

only 3,65 € per issue

Rent or buy this article

Prices vary by article type

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Nature 604 , 33-34 (2022)

doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-022-00926-6

Updates & Corrections

Correction 07 April 2022 : An earlier version of this book review erroneously stated that one-quarter of the Japanese population was expected to have dementia by 2045. In fact, the proportion refers only to people aged older than 65.

Competing Interests

The author declares no competing interests.

Related Articles

- Sustainability

Nearly half of China’s major cities are sinking — some ‘rapidly’

News 18 APR 24

The world needs a COP for water like the one for climate change

Correspondence 16 APR 24

Don’t dismiss carbon credits that aim to avoid future emissions

Correspondence 02 APR 24

It’s time to talk about the hidden human cost of the green transition

Shrouded in secrecy: how science is harmed by the bullying and harassment rumour mill

Career Feature 16 APR 24

Use fines from EU social-media act to fund research on adolescent mental health

Correspondence 09 APR 24

Qiushi Chair Professor

Distinguished scholars with notable achievements and extensive international influence.

Hangzhou, Zhejiang, China

Zhejiang University

ZJU 100 Young Professor

Promising young scholars who can independently establish and develop a research direction.

Head of the Thrust of Robotics and Autonomous Systems

Reporting to the Dean of Systems Hub, the Head of ROAS is an executive assuming overall responsibility for the academic, student, human resources...

Guangzhou, Guangdong, China

The Hong Kong University of Science and Technology (Guangzhou)

Head of Biology, Bio-island

Head of Biology to lead the discovery biology group.

BeiGene Ltd.

Research Postdoctoral Fellow - MD (Cardiac Surgery)

Houston, Texas (US)

Baylor College of Medicine (BCM)

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Population Growth

Population growth is one of the most important topics we cover at Our World in Data .

For most of human history, the global population was a tiny fraction of what it is today. Over the last few centuries, the human population has gone through an extraordinary change. In 1800, there were one billion people. Today there are more than 8 billion of us.

But after a period of very fast population growth, demographers expect the world population to peak by the end of this century.

On this page, you will find all of our data, charts, and writing on changes in population growth. This includes how populations are distributed worldwide, how this has changed, and what demographers expect for the future.

Related topics

- Child Mortality

- Fertility Rate

- Life Expectancy

- Age Structure

Key insights on Population Growth

Population cartograms show us where the world’s people are.

Geographical maps show us where the world’s landmasses are; not where people are. That means they don’t always give us an accurate picture of how global living standards are changing.

One way to understand the distribution of people worldwide is to redraw the world map – not based on the area but according to population.

This is shown here as a population cartogram : a geographical presentation of the world where the size of countries is not drawn according to the distribution of land but by the distribution of people. It’s shown for the year 2018.

As the population size rather than the territory is shown in this map, you can see some significant differences when you compare it to the standard geographical map we’re most familiar with.

Small countries with a high population density increase in size in this cartogram relative to the world maps we are used to – look at Bangladesh, Taiwan, or the Netherlands. Large countries with a small population shrink in size – look for Canada, Mongolia, Australia, or Russia.

You can find more details on this cartogram in our article about it:

What you should know about this data

- This map is based on the United Nation’s 2017 World Population Prospects report. Our interactive charts show population data from the most recent UN revision. This means there may be minor differences between the figures shown on the map and the latest estimates in our other charts.

The world population has increased rapidly over the last few centuries

The speed of global population growth over the last few centuries has been staggering. For most of human history, the world population was well under one million. 1

As recently as 12,000 years ago, there were only 4 million people worldwide.

The chart shows the rapid increase in the global population since 1700.

The one-billion mark wasn’t broken until the early 1800s. It was only a century ago that there were 2 billion people.

Since then, the global population has quadrupled to eight billion.

Around 108 billion people have ever lived on our planet. This means that today’s population size makes up 6.5% of the total number of people ever born. 2

This increase has been the result of advances in living conditions and health that reduced death rates – especially in children – and increases in life expectancy.

- This data comes from a combination of sources, all detailed in our sources article for our long-term population dataset.

Population growth is no longer exponential – it peaked decades ago

There’s a popular misconception that the global population is growing exponentially. But it’s not.

While the global population is still increasing in absolute numbers, population growth peaked decades ago.

In the chart, we see the global population growth rate per year. This is based on historical UN estimates and its medium projection to 2100.

Global population growth peaked in the 1960s at over 2% per year. Since then, rates have more than halved, falling to less than 1%.

The UN expects rates to continue to fall until the end of the century. In fact, towards the end of the century, it projects negative growth, meaning the global population will shrink instead of grow.

Global population growth, in absolute terms – which is the number of births minus the number of deaths – has also peaked. You can see this in our interactive chart:

The world has passed “peak child”

Hans Rosling famously coined the term “ peak child ” for the moment in global demographic history when the number of children stopped increasing.

According to the UN data, the world has passed “peak child”, which is defined as the number of children under the age of five.

The chart shows the UN’s historical estimates and projections of the number of children under five.

It estimates that the number of children in the world peaked in 2017. For the coming decades, demographers expect a decades-long plateau before the number will decline more rapidly in the second half of the century.

- These projections are sensitive to the assumptions made about future fertility rates worldwide. Find out more from the UN World Population Division .

- Other sources and scenarios in the UN’s projections suggest that the peak was reached slightly earlier or later. However, most indicate that the world is close to “peak child” and the number of children will not increase in the coming decades.

- The ‘ups and downs’ in this chart reflect generational effects and ‘baby booms’ when there are large cohorts of women of reproductive age, and high fertility rates. The timing of these transitions varies across the world.

The UN expects the global population to peak by the end of the century

When will population growth come to an end?

The UN’s historical estimates and latest projections for the global population are shown in the chart.

The UN projects that the global population will peak before the end of the century – in 2086, at just over 10.4 billion people.

- These projections are sensitive to the assumptions made about future fertility and mortality rates worldwide. Find out more from the UN World Population Division .

- Other sources and scenarios in the UN’s projections can produce a slightly earlier or later peak. Most demographers, however, expect that by the end of the century, the global population will have peaked or slowed so much that population growth will be small.

Explore data on Population Growth

Research & writing.

What would the work look like if each country’s area was in proportion to its population?

The world population has increased rapidly in recent centuries. But this is slowing.

Max Roser and Hannah Ritchie

More Key articles on Population Growth

How many people die and how many are born each year.

Hannah Ritchie and Edouard Mathieu

Five key findings from the 2022 UN Population Prospects

Hannah Ritchie, Edouard Mathieu and Lucas Rodés-Guirao

Which countries are most densely populated?

Demographic change.

Hannah Ritchie

Definitions and sources

Edouard Mathieu and Lucas Rodés-Guirao

Other articles related to population growth

Interactive charts on Population Growth

Our World in Data is free and accessible for everyone.

Help us do this work by making a donation.

World Population Prospects 2022

- Download Center

- Data Portal

- Data Sources

- Graphs / Profiles

- Definition of Regions

- Glossary of Demographic Terms

- Methodology

- Definition of Projection Scenarios

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Publications

- World Urbanization Prospects

- Population Division

The 2022 Revision of World Population Prospects is the twenty-seventh edition of official United Nations population estimates and projections that have been prepared by the Population Division of the Department of Economic and Social Affairs of the United Nations Secretariat. It presents population estimates from 1950 to the present for 237 countries or areas, underpinned by analyses of historical demographic trends. This latest assessment considers the results of 1,758 national population censuses conducted between 1950 and 2022, as well as information from vital registration systems and from 2,890 nationally representative sample surveys The 2022 revision also presents population projections to the year 2100 that reflect a range of plausible outcomes at the global, regional and national levels.

The main results are presented in a series of Excel files displaying key demographic indicators for each UN development group, World Bank income group, geographic region, Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) region, subregion and country or area for selected periods or dates within 1950-2100. An online database (Data Portal) provides access to a subset of key indicators and interactive data visualization, including an open API for programmatic access. For advanced users who need to use these data in a database form or statistical software, we recommend to use the CSV format for bulk download. Special Aggregates also provide additional groupings of countries. For the first time, the estimates and projections are presented in one-year intervals of age and time instead of the five-year intervals used previously. The various datasets disaggregated by age are available in two forms: by standard 5-year age groups and single ages.

Additional outputs, including results from the probabilistic projections, and more detailed metadata will be posted soon after the initial public release.

Disclaimer: This web site contains data tables, figures, maps, analyses and technical notes from the current revision of the World Population Prospects. These documents do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries.

Are we preparing for world population growth? The experts are divided

Increasing populations could cause problems according to some researchers. Image: Cory Schadt/Unsplash

.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo{-webkit-transition:all 0.15s ease-out;transition:all 0.15s ease-out;cursor:pointer;-webkit-text-decoration:none;text-decoration:none;outline:none;color:inherit;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:hover,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-hover]{-webkit-text-decoration:underline;text-decoration:underline;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:focus,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-focus]{box-shadow:0 0 0 3px rgba(168,203,251,0.5);} Kayleigh Bateman

.chakra .wef-9dduvl{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-size:1.25rem;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-9dduvl{font-size:1.125rem;}} Explore and monitor how .chakra .wef-15eoq1r{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-size:1.25rem;color:#F7DB5E;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-15eoq1r{font-size:1.125rem;}} Global Governance is affecting economies, industries and global issues

.chakra .wef-1nk5u5d{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;color:#2846F8;font-size:1.25rem;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-1nk5u5d{font-size:1.125rem;}} Get involved with our crowdsourced digital platform to deliver impact at scale

Stay up to date:, global governance.

Listen to the article

- Nearly 11 billion people will be on Earth by the end of the century, the United Nations says.

- But a new study suggests that’s no longer the most likely scenario and forecasts a peak just after mid-century and then a decline.

- The University of Washington says the world population will fall in the last third of this century to 8.8 billion in 2100.

- Understanding how populations could evolve matters because it affects the strategies put in place by global governments and industries.

Overpopulation is a concept that’s hovered over the Earth’s future for some time.

It has inspired many works, including Stephen Emmott’s 10 Billion , which outlines a future of food shortages, energy wars and civil conflict.

But what if studies invoking concerns about a fast-rising world population were wrong? That could be the case, according to The University of Washington’s Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, which challenges the assumptions behind predictions for continued growth and says a declining and ageing population will be key future challenges .

That sets it at odds with the United Nations which predicts that the global population will continue to grow, albeit at a slower pace, and will reach 10.9 billion in 2100, up from around 7.7 billion people in 2019.

Have you read?

Bye, bye, baby birthrates are declining globally – here's why it matters, africa’s population will triple by the end of the century even as the rest of the world shrinks, this is how to sustainably feed 10 billion people by 2050, why do these predictions matter.

Understanding how populations could evolve matters because future population sizes underpin future strategies for governments and industries around the world; they need to plan for key investments in infrastructure or goals for international development and carbon emission reductions. A decline, instead of an increase, would have many implications.

“Our forecasts for a shrinking world population have positive implications for the environment, climate change, and food production,” the researchers, led by Professor Stein Emil Vollset, wrote. “But possible negative implications for labour forces, economic growth, and social support systems.”

How do the world population predictions vary?

The world population may peak in 2064 at 9.7 billion and then decline to around 8.8 billion by 2100, the University of Washington researchers wrote in The Lancet.

There is a global myth that productivity declines as workers age. In fact, including older workers is an untapped source for growth.

The world has entered a new phase of demographic development where people are living longer and healthier lives. As government pension schemes are generally ill-equipped to manage this change, insurers and other private-sector stakeholders have an opportunity to step in.

The World Economic Forum, along with the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and AARP , have created a learning collaborative with over 50 global employers including AIG, Allianz, Aegon, Home Instead, Invesco and Mercer. These companies represent over two million employees and $1 trillion in annual revenue.

Learn more in our impact story .

The UN’s prediction of 10.9 billion by 2100 is based, at least in part, on “the unprecedented ageing of the world’s population”, as well as “rapid population growth driven by high fertility” in some countries and regions.

Whereas, the University of Washington’s researchers argue that a population decline will be linked to the attainment of developmental goals, for example the education of women and girls and their access to contraception.

“The different outcomes reflect the uncertainty in making projections over such a long time period,” says Leontine Alkema, a statistical modeller at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, discussing discrepancies in population data for a Nature article .

“It’s kind of an impossible exercise and so we do the best we can and it’s good that different groups use different approaches.”

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

The Agenda .chakra .wef-n7bacu{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-weight:400;} Weekly

A weekly update of the most important issues driving the global agenda

.chakra .wef-1dtnjt5{display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;-webkit-flex-wrap:wrap;-ms-flex-wrap:wrap;flex-wrap:wrap;} More on Global Governance .chakra .wef-nr1rr4{display:-webkit-inline-box;display:-webkit-inline-flex;display:-ms-inline-flexbox;display:inline-flex;white-space:normal;vertical-align:middle;text-transform:uppercase;font-size:0.75rem;border-radius:0.25rem;font-weight:700;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;line-height:1.2;-webkit-letter-spacing:1.25px;-moz-letter-spacing:1.25px;-ms-letter-spacing:1.25px;letter-spacing:1.25px;background:none;padding:0px;color:#B3B3B3;-webkit-box-decoration-break:clone;box-decoration-break:clone;-webkit-box-decoration-break:clone;}@media screen and (min-width:37.5rem){.chakra .wef-nr1rr4{font-size:0.875rem;}}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-nr1rr4{font-size:1rem;}} See all

The World Bank: How the development bank confronts today's crises

Efrem Garlando

April 16, 2024

This is why the number of refugees could double in the next decade, according to the head of UNHCR

Liam Coleman

March 7, 2024

AI: Will governance catch up with the tech in 2024?

David Elliott

March 1, 2024

The World Economic Forum: A Swiss success story

Selina Hänni and Micol Lucchi

January 17, 2024

Workers' rights are vital to revitalizing democracy. Here's why

Luc Triangle

January 15, 2024

How to thrive when uncertainty becomes the new norm for governance

January 11, 2024

- Ideas for Action

- Join the MAHB

- Why Join the MAHB?

- Current Associates

- Current Nodes

- What is the MAHB?

- Who is the MAHB?

- Acknowledgments

A Brief on Overpopulation – Why it Matters and What You Can Do About It

Erin Brown | April 4, 2023 | Leave a Comment

Photo by Candace McDaniel on StockSnap

As humanity has surpassed the 8 billion people milestone, it is more important now than ever to talk about population. What will we do if we continue to grow at exponential rates? What are ethical, viable strategies to decrease population?

“First off, let me get this straight, discussing addressing overpopulation does not mean discussing killing people. The goal is actually to prevent it.” – Dr. Jane O’Sullivan

Current world population in January 2023: 8 billion

The current rate of population growth is around 80 million people per year. There are over 8 billion people on the planet, the last billion added in less than the last 12 years.

The Earth’s first billion people milestone took from the beginning of human history until the 1800s to be achieved. Then, due to the industrial revolution, humanity reached the second billion mark by 1930 (taking only 130 years), reached the third billion in 1960 (only took 30 years), then reached the fourth billion by 1974 (only took 14 years), and the fifth billion by 1987 (only took 13 years). We hit 6 billion in 1999 (which took 12 years) and hit 7 billion in 2011 (which took about 12 years). At the current growth rate, the world population will reach 9 billion by 2037 and 10 billion by 2057.

The growth rate is declining, but not at a fast enough rate to combat the exponential compound growth. The growth rate was 2% in the 1970s. Now it is 1.05%. Any growth rate above 1% means we are still adding more people to the planet every year.

What is overpopulation?

Overpopulation is a human population in numbers high enough to cause environmental deterioration, impaired quality of life, or population crash.

Why is overpopulation an issue?

Overrun natural resources can only lead to death by starvation, conflict, and disease, and the only viable alternative is voluntary restraint on human births.

What is carrying capacity?

Carrying capacity is defined as the maximum population of a species that an area will support without undergoing deterioration.

Paul R. Ehrlich and other scientists estimate the world’s optimum population for carrying capacity (at a comfortable standard of living – editor’s note) to be less than two billion people – 6 billion fewer than on the planet today. “But the longer humanity pursues business as usual, the smaller the sustainable society is likely to prove to be. We’re continuously harvesting the low-hanging fruit, for example by driving fisheries stocks to extinction” – Paul Ehrlich says.

How do we revert population overshoot to a sustainable population level?

Geologist Art Berman explains population overshoot this way: “Overshoot means that humans are using natural resources and polluting at rates beyond the planet’s capacity to recover. The main cause of overshoot is the extraordinary growth of the human population made possible by fossil energy. Concerns about overshoot and population raised more than 40 years ago were dismissed. Climate change has captured public awareness more recently although many doubt that it is an emergency. Overshoot is more difficult to dispute; it destroys rainforests, leads to the extinction of other species, the pollution of land, rivers, and seas, the acidification of the oceans, and the loss of fisheries and coral reefs. People understandably want to know the solutions. Overshoot is the problem we must address. Any plan that includes continued growth is doomed to fail.”

What can we do? Jane O’Sullivan outlines the two options for addressing population overshoot – i ncrease the Earth’s carrying capacity or decrease population.

Increasing Earth’s carrying capacity

We are already doing this by (a) using fewer natural resources per person, or (b) increasing productivity by finding more ways to use resources. This only defers the problem and creates collateral damage.

Decreasing population numbers

If we talk about this now, the hope is to increase our options for solutions. One of the biggest challenges to facing overpopulation head-on and discussing a decreasing population are the stigmas and myths associated with reducing human population numbers. An elaborate set of myths has emerged in opposition to reducing population levels. These myths may prevent even environmentalists from viewing overpopulation as an issue. Jane O’Sullivan elucidates on the following six myths that make inaction a virtue.

Myth 1 – The human population is stabilizing, and birth rates are decreasing

Truth – Birth rates started declining in the 1970s-90s due to family planning, but not low enough. The number of mothers is still increasing faster than family planning is decreasing the birth rate . We are still having more births per year than ever before. The total fertility rate has decreased, but as fertility decline has slowed to a trickle, the number of total births has continued to increase.

Myth 2 – China is the only one with the problem and they used cruel methods (one-child policy)

Truth – Family planning programs have helped many countries successfully reduce births through voluntary means, including China, before the one-child policy.

Myth 3 – Poverty causes population growth, therefore development is the best contraceptive

I.e., family planning is unnecessary and inefficient as long as there is development.

Truth – If this was true, we would see the population decline as development increases. However, it is the decrease in fertility rates that drove economic development, not the other way around. This myth is therefore “correlation implying causation” in the wrong direction. The poorest countries could lower their population by family planning just as quickly as rich countries if they choose to prioritize it.

Countries of families with four or more children, on average, have the lowest level of development; in families with 3 children or fewer the level goes up by some degree, and with two or fewer children development soars. The current focus should be on expanding provisions for teachers, doctors, equality, etc. instead of just giving people what they need.

Myth 4 – Educating girls is the key to ending population growth

Truth – Another indirect approach that excludes a discussion on the benefit of small families and ending population growth. Educating girls helps but not much unless it is also flanked by family planning efforts. Family planning has a stronger effect on women regulating their fertility, decreasing the fertility gap between the educated and uneducated, and with family planning, girls are more likely to stay in school.

Myth 5 – Population growth is good for the economy

Truth – This makes people poorer as shown under Myth #3.

Myth 6 – Population growth in poor nations does not matter because of their “tiny carbon footprint”

Truth – Population growth is a greater threat than climate change. The best way for anyone to decrease their carbon footprint is to have one less kid.

Therefore, family planning is the most economical way to a sustainable future.

What action can each of us take?

1. Discuss smaller family sizes with your partner, family, and friends – how do we aim for birth rates lower than two children per couple?

2. Share information about the environmental impacts of population growth with friends and family. Advocate for action to reduce and reverse population growth.

3. Reassess concerns about aging – how can we shift away from worshipping eternal youth, to accepting and valuing the entire life cycle?

4. Celebrate population decline – what are possible depopulation dividends?

5. Support organizations and efforts that support family planning and women’s education.

Damien Carrington, an environmental editor at The Guardian, interviewed Prof. Paul Ehrlich about the solutions:

“The solutions are tough,” Ehrlich says. “To start, make modern contraception and backup abortion available to all and give women full equal rights, pay, and opportunities with men. Focus on overconsumption and equity issues. Specifically women’s rights and the explicit countering of racism.”

Ehrlich also says that an unprecedented redistribution of wealth is needed to end the over-consumption of resources, but “the rich who now run the global system – that hold the annual ‘world destroyer’ meetings in Davos – are unlikely to let it happen…Too many rich people in the world is a major threat to the human future, and cultural and genetic diversity are great human resources… It is a near certainty in the next few decades, and the risk is increasing continually as long as the perpetual growth of the human enterprise remains the goal of economic and political systems. As I’ve said many times, ‘perpetual growth is the creed of the cancer cell’.”

If cultural and genetic diversity are great human resources, how can the rich and the poor come together across the world to solve this issue?

Anne and Paul Ehrlich expand on their “vision for a cure” :

“Rich white people love to hold meetings to discuss the ‘population problem’ which always ends up focusing on the very real demographic difficulties of those with darker skin tones, especially people who live in Africa and Latin America. But isn’t it really time for the poor people of the world, especially those not in need of tanning beds, to extend a helping hand to the major villains of the destruction of humanity’s life-support systems? Could they not hold an educational conference in Washington, D.C. to explain why civilization is going down the drain, to the per-capita most environmentally destructive giant nation on the planet? Leaders from the “South” could both organize the event and supply experts to educate the wealthy and middle class on their ethical responsibilities and ways to meet them. We envision learning sessions on topics such as:

- Avoiding the second child.

- The population problem beyond numbers: inequality and waste of talent.

- Are borders ethical?

- Population shrinkage for politicians.

- GDP shrinkage for economists.

- Do Trump and his colleagues prove that the lighter your skin, the lighter your brain?

- Citizens United: It’s time for euthanasia for corporations.

- Redistribution and survival.

- Disbanding “Murder Incorporated”: gun manufacturers and big pharma.

- How to end plastic production.

- The historical contributions of the global South to the food enjoyed by the North.

- How biodiversity loss is accompanied by the loss of human cultural diversity.

- We know our populations are growing too fast; how to help us help ourselves?

- Why anti-abortion laws kill poor women.

You can doubtless think of others. The possibilities are endless”.

References:

Berman, Art. The Climate-Change Trip to Abilene. July 13, 2022. https://mahb.stanford.edu/library-item/the-climate-change-trip-to-abilene/

Carrington, Damien. Interview with Paul Ehrlich: Collapse of civilization is a near certainty within decades. July 9, 2020. https://www.theguardian.com/cities/2018/mar/22/collapse-civilisation-near-certain-decades-population-bomb-paul-ehrlich

Ehrlich, Anne H.; Ehrlich, Paul R. Overpopulation In America -And Its Cures. November 14, 2019. https://mahb.stanford.edu/blog/overpopulation-america-cures/

O’Sullivan, Jane. The tenth presentation at the Delivering the Human Future Conference. Titled: The Future of the Human Population. March 21, 2021. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=shUNJPLpXpQ

Population Statistics. https://www.worldometers.info/world-population/

The MAHB Blog is a venture of the Millennium Alliance for Humanity and the Biosphere. Questions should be directed to [email protected]

The World’s Population May Peak in Your Lifetime. What Happens Next?

The global human population has been climbing for the past two centuries. But what is normal for all of us alive today — growing up while the world is growing rapidly — may be a blip in human history. Children born today will very likely live to see the end of global population growth.

A baby born this year will be 60 in the 2080s, when demographers at the U.N. expect the size of humanity to peak. The Wittgenstein Center for Demography and Global Human Capital in Vienna places the peak in the 2070s. The Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation at the University of Washington puts it in the 2060s. All of the predictions agree on one thing: We peak soon.

And then we shrink. Humanity will not reach a plateau and then stabilize. It will begin an unprecedented decline.

Because most demographers look ahead only to 2100, there is no consensus on exactly how quickly populations will fall after that. Over the past 100 years, the global population quadrupled, from two billion to eight billion. As long as life continues as it has — with people choosing smaller family sizes, as is now common in most of the world — then in the 22nd or 23rd century, our decline could be just as steep as our rise.

By Dean Spears

Graphics by Sara Chodosh

Dr. Spears is an economist at the Population Research Center at the University of Texas, Austin.

Most people now live in countries where two or fewer children are born for every two adults. If all people in the United States today lived through their reproductive years and had babies at an average pace, then it would add up to about 1.66 births per woman. In Europe, that number is 1.5; in East Asia, 1.2; in Latin America, 1.9. Any worldwide average of fewer than two children per two adults means our population shrinks and in the long run each new generation is smaller than the one before. If the world’s fertility rate were the same as in the United States today, then the global population would fall from a peak of around 10 billion to less than two billion about 300 years later, over perhaps 10 generations. And if family sizes remained small, we would continue declining.

What would happen as a consequence? Over the past 200 years, humanity’s population growth has gone hand in hand with profound advances in living standards and health: longer lives, healthier children, better education, shorter workweeks and many more improvements. Our period of progress began recently, bringing the discovery of antibiotics, the invention of electric lightbulbs, video calls with Grandma and the possibility of eradicating Guinea worm disease . In this short period, humanity has been large and growing. Economists who study growth and progress don’t think this is a coincidence. Innovations and discoveries are made by people. In a world with fewer people in it, the loss of so much human potential may threaten humanity’s continued path toward better lives.

Whenever low birthrates get public attention, chances are somebody is concerned about what it means for international competition, immigration or a government’s fiscal challenges over the coming decades as the population ages. But that’s thinking too small. A depopulating world is a big change that we all face together. It’s bigger than geopolitical advantage or government budgets. It’s much bigger than nationalistic worries over which country or culture might manage to eke out a population decline that’s a little bit slower than its neighbors’.

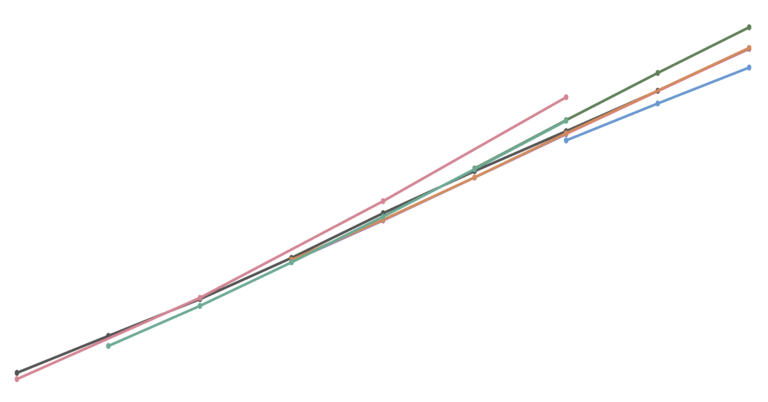

Fewer and fewer countries have high birthrates

Total fertility rates and populations for countries with at least one million people.

Source: U.N. World Population Prospects 2022

Sustained below-replacement fertility will mean tens of billions of lives not lived over the next few centuries — many lives that could have been wonderful for the people who would have lived them and by your standards, too.

Perhaps that loss doesn’t trouble you. It would be tempting to welcome depopulation as a boon to the environment. But the pace of depopulation will be too slow for our most pressing problems. It will not replace the need for urgent action on climate, land use, biodiversity, pollution and other environmental challenges. If the population hits around 10 billion people in the 2080s and then begins to decline, it might still exceed today’s eight billion after 2100. Population decline would come quickly, measured in generations, and yet arrive far too slowly to be more than a sideshow in the effort to save the planet. Work to decarbonize our economies and reform our land use and food systems must accelerate in this decade and the next, not start in the next century.

This isn’t a call to immediately remake our societies and economies in the service of birthrates. It’s a call to start conversations now, so that our response to low birthrates is a decision that is made with the best ideas from all of us. Kicking the can down the road will make choices more difficult for future generations. The economics and politics of a society in which the old outnumber the young will make it even harder to choose policies that support children.

If we wait, the less inclusive, less compassionate, less calm elements within our society and many societies worldwide may someday call depopulation a crisis and exploit it to suit their agendas — of inequality, nationalism, exclusion or control. Paying attention now would create an opportunity to lay out a path that would preserve freedom, share burdens, advance gender equity, value care work and avoid the disasters that happen when governments try to impose their will on reproduction .

Or perhaps we don’t need to concern ourselves at all if fertility rates self-correct to two. But the data shows that they don’t. Births won’t automatically rebound just because it would be convenient for advancing living standards or sharing the burden of care work or financing social insurance programs. We know that fertility rates can stay below replacement because they have. They’ve been below that level in Brazil and Chile for about 20 years; in Thailand for about 30 years; and in Canada, Germany and Japan for about 50.

In fact, in none of the countries where lifelong fertility rates have fallen well below two have they ever returned above it. Depopulation could continue, generation after generation, as long as people look around and decide that small families work best for them, some having no children, some having three or four and many having one or two.

Nor can humanity count on any one region or subgroup to buoy us all over the long run. Birthrates are falling in sub-Saharan Africa , the region with the current highest average rates, as education and economic opportunities continue to improve. Israel is an example of a rich country that, as of today, has above-replacement fertility rates. But there, too, fertility rates have been falling over the decades, from 4.5 in 1950 to 3.0 today. Israel may not be above 2.1 for many more generations.

As living standards increased, birthrates fell

Total fertility rates and G.D.P. per capita for countries with at least one million people.

Sources: U.N. World Population Prospects 2022, World Bank

The main reason that birthrates are low is simple: People today want smaller families than people did in the past. That’s true in different cultures and economies around the world. It’s what both women and men report in surveys .

Humanity is building a better, freer world with more opportunities for everyone, especially for women. That progress deserves everyone’s greatest celebration — and everyone’s continued efforts. That progress also means that, for many of us, the desire to build a family can clash with other important goals, including having a career , pursuing projects and maintaining relationships . No society has solved this yet. These tradeoffs bite deep for parents everywhere. For some parents, that means struggle. For others, that means smaller families than they hoped for. And for too many, it means both.

In a world of sustained low birthrates and declining populations, there may be threats of backsliding on reproductive freedom — by limiting abortion rights, for example. Some will inexcusably claim that restricting reproductive choice is a way to curb long-run population decline. Some already do.

No. Low birthrates are no reason to reverse progress toward a more free, diverse and equal world. Restricting reproductive rights — by denying access to critical health care and by denying the basic freedom to choose to parent or not to parent — would harm many people and for that reason would be wrong whether or not depopulation is coming. And it would not prevent the population from shrinking. We know that because fertility rates are below two both where abortion is freely available and where abortion is restricted . Any policymaker asking how to respond to global depopulation should start by asking what people want and how to help them achieve it rather than by asking what they might take away.

There are many ways to live a life or be a family, and having that freedom and diversity is good. If an inclusive, compassionate response to population decline emerges someday, it need not be in conflict with those values. If one in every four pairs of American adults would choose to have one more child, that would be enough to stabilize the U.S. population. In that future, there would still be many ways to live a life or be a family; two kids on average doesn’t mean two kids for everyone.

Nobody yet knows what to do about global depopulation. But it wasn’t long ago that nobody knew what to do about climate change. These shared challenges have much in common, which gives humanity some shared experience to build on.

As with climate change, our individual decisions on family size add up to an outcome that we all share. No people are making mistakes when they choose not to have children or to have small families. (Although we might all be making a mistake, together, when instead of taking care of one another, we make it hard for people to choose larger families.) It’s in no one’s hands to change global population trajectories alone. Not yours, whatever you choose for your life, not one country’s, not one generation’s. Nor is it in your hands personally to end all carbon emissions even by ending your own emissions. And yet our personal choices add up to big implications for humanity as a whole.

It’s not too early to take depopulation seriously. The New York Times reported on the threat of climate change in 1956. A scientist testified about it before Congress in 1957. In 1965 the White House released a report calling carbon dioxide a pollutant, warning of a warming world with melting ice caps and rising sea levels. That was nearly six decades ago.

Six decades from now is when the U.N. projects the size of the world population will peak. There won’t be any quick fixes: Even if it’s too early today to know exactly how to build an abundant future that offers good lives to a stable, large and flourishing future population, we should already be working toward that goal. Waiting until the population peaks to ask how to respond to depopulation would be as imprudent as waiting until the world starts to run out of fossil fuels to begin responding to climate change.

Humanity needs a compassionate, factual and fair conversation about how to respond to depopulation and how to share the burdens of creating each future generation. The way to have that conversation is to start paying attention now.

Methodology

Historical data for the top line chart came from Our World in Data. The projections are by Dean Spears, Sangita Vyas, Gage Weston and Michael Geruso.

An earlier version of this article described incorrectly Dr. Spears’s role at the Population Research Center at the University of Texas, Austin. He is a faculty member there, not a research affiliate.

An earlier version of a graphic accompanying this article misidentified the statistics for Guinea as those for Guinea-Bissau. The graphic has been corrected.

- Share full article

Advertisement

Search form

World population prospects 2022: summary of results.

World Population Prospects 2022 is the twenty-seventh edition of the official United Nations population estimates and projections. It presents population estimates from 1950 to the present for 237 countries or areas, underpinned by analyses of historical demographic trends. This latest assessment considers the results of 1,758 national population censuses conducted between 1950 and 2022, as well as information from vital registration systems and from 2,890 nationally representative sample surveys.

The 2022 revision also presents population projections to the year 2100 that reflect a range of plausible outcomes at the global, regional and national levels. For the first time, the estimates and projections are presented in one-year intervals of age and time instead of the five-year intervals used previously.

- SG's remarks on the occasion of World Population Day [ ar ] [ en ] [ es ] [ fr ] [ ru ] [ zh ]

- Summary of Results

- Key messages

- Online portal

- Methodology paper

- Data Sources

- SDG blog by Ms. Anastasia Gage

- Video message by John Wilmoth, Director of the Population Division

- Media advisory

- Press release [ ar ] [en] [ es ] [ fr ] [ru] [ zh ]

- Remarks by Ms. Maria-Francesca Spatolisano, Assistant-Secretary-General for Policy Coordination and Inter-Agency Affairs

- Remarks by Mr. John Wilmoth, Director of the Population Division

- Press conference (UN Web TV)

- Remarks by Mr. Liu Zhenmin, Under-Secretary-General for Economic and Social Affairs, Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UN DESA)

- Remarks by Mr. John Wilmoth, Director of the Population Division, UN DESA [ PDF ] [ Presentation ]

- Australian National University, School of Demography

- World Population Day webinar, Institute of Statistics and Demography, Warsaw, Poland, 12 July 2022 (in English/Polish) [ youTube ]

- International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS), Mumbai, India [ YouTube ]

- Institut national d'études démographiques (INED) [ en ] [ fr ]

- Population & Demography Data Explorer - Our World in Data

- Environmental Change and Security Programme, the Wilson Center

Related link

- Day of Eight Billion, 15 November 2022

Tackling Population Pressure

Every day we add 227,000 more people to the planet — and the UN predicts human population will surpass 11 billion by the end of the century. As the world's population grows, so do its demands for water, land, trees and fossil fuels — all of which come at a steep price for already endangered plants and animals.

Reproductive health, rights and justice are threatened by the same systems of oppression that overexploit the environment and drive the extinction crisis. But through solutions like gender equity and a just transition to sustainable consumption and production, we can promote human rights; decrease poverty and overcrowding; raise standards of living; and allow people and nature to thrive.

The Center has been working to address the connection between human population pressure and the extinction crisis since 2009. Our innovative campaigns focus on commonsense solutions such as gender empowerment, the education of all people, universal access to all forms of sexual and reproductive healthcare, sustainable and equitable lifestyle choices, an economy that doesn’t rely on endless growth, and a societal commitment to improve living conditions for all species.

Endangered Species Condoms

Endangered Species Condoms offer a fun, unique way to break through the taboo and get people talking about the link between human population growth and the wildlife extinction crisis.

The Extinction Crisis

Most biologists agree we're in the midst of the Earth's sixth mass extinction event; species are disappearing at the greatest rate since dinosaurs roamed the planet. This time, though, it isn't because of geologic or cosmic forces — it's because of our unsustainable growth and consumption.

Human Population Growth and Urban Sprawl

As our human footprint reaches farther and farther into remote areas in search of room to build cities, housing developments, golf courses and new farms, we're squeezing wildlife into ever smaller habitat refuges, often leaving endangered species with nowhere to go.

Climate Change

A 2009 study of the relationship between population growth and global warming determined that the “carbon legacy” of just one child in the United States can produce 20 times more greenhouse gas than a person is able to conserve by taking other energy-saving actions.

Bringing Population Back Into the Conversation

Human population growth and consumption are at the root of our most pressing environmental crises, but they’re often left out of the conversation. We can fight to curb climate change, stop habitat loss, and clean up pollution, but if we don't also fight for reproductive justice for those most severely harmed by these environmental crises — including young people, immigrants, Black, Indigenous and people of color, minoritized ethnic and religious groups, LGBTQIA+ communities and rural communities — it'll remain an uphill battle we can't win. The first step to solving a problem is getting people to talk about it.

The Center is working to put the spotlight back on human population growth and the need to fight for reproductive and environmental justice. We're using creative media like our award-winning Endangered Species Condoms to start conversations on a person-to-person basis nationwide; we’re circulating videos to explain the connections between population growth and other environmental problems and highlight the importance of healthcare for all. We're also bringing the message to museums, science centers and classrooms through fun and interactive Pillow Talk events, via virtual and in-person film series, and through social media campaigns.

Supporting Reproductive Justice

Everyone plays a role in human population growth, but when it comes to reproductive decisions, women and gender-diverse people are disproportionately affected by a lack of empowerment and access to healthcare, which not only affects their reproductive futures but also income and wealth equity, education, and leadership opportunities. Many people worldwide and in the United States are unable to get the sexual and reproductive healthcare they want or need. Unfortunately U.S. lawmakers and courts are currently doing everything they can to restrict reproductive freedom, including bans on comprehensive sex education and abortion.

Reproductive justice is environmental justice. In order to make sure we leave room for wildlife, it's critical that every pregnancy is planned and that people have the ability to decide when — or if — they want their family to grow. When people have access to voluntary contraception and equal education, they tend to choose to delay childbearing and have smaller families, leading to lower fertility rates. The Center supports unfettered access to education, reproductive healthcare and gender equity for all. Every person should have the tools, information and autonomy to make the best reproductive choice for themselves and the planet.

Help support our cutting-edge work in the Population and Sustainability Program.

JUSTICE & POLICY POSITIONS

How to bring anti-racism into the population conversation, statement on abortion, statement on diversity, statement on gender, statement on immigration, the 17 principles of environmental justice, media & publications, the campus health clinic scorecard — wildlife edition: rankings of sexual health resources at u.s. colleges and universities, the influence of environmental toxicity, inequity and capitalism on reproductive health report, gender and the climate crisis: equitable solutions for climate plans report, contraception and consumption survey results report, webinars & videos, film series, 2023 environmental and reproductive health webinar and film series, 2022-2023 campus film tour, 2021 population film series, crowded planet: population resource center, pop x newsletter, food x newsletter, volunteer to distribute endangered species condoms.

Contact: Kelley Dennings

The Center for Biological Diversity is a 501(c)(3) registered charitable organization. Tax ID: 27-3943866.

The problem with ‘too many’

According to population alarmists, our world is overrun and close to bursting at the seams. Politicians, media pundits and even some academics have asserted that global challenges like economic instability, climate change and resource wars can be pinned on overpopulation – on too much demand and not enough supply.

They paint a picture of out-of-control, unstoppable birth rates, usually pointing the finger at poor and marginalized communities who have long been portrayed as reproducing recklessly and prolifically despite making the smallest contributions to issues such as environmental destruction.

This narrative oversimplifies complex issues and causes real harm.

It paints human survival as a problem, rather than an achievement.

It diverts attention away from those responsible for the real, urgent issues facing us and makes it harder to hold them to account.

It implies that women’s reproductive choices should be co-opted to solve the problem of ‘overpopulation’.

What are the facts?

>>:fact/1 life expectancy.

Global life expectancy reached 72.8 years in 2019 – an increase of nearly 9 years since 1990.

It is expected to reach 77.2 years by 2050.

>>This is something to be celebrated.

>>:FACT/2 Population Growth

Most of the projected increase in global population through 2050 will be driven by the momentum of past growth.

This means that further actions by governments aimed at reducing fertility will do little to slow the pace of growth between now and 2050.

Based on current projections

With efforts to control fertility and decrease population

Population growth

>>:FACT/3 Emissions

Half of all emissions come from the richest 10 per cent of the world’s population: Conflating a rise in emissions with population growth is therefore mistaken.

Perhaps the most alarming outcome of the “too many” narrative is that when we blame global issues on a growing population, we imply that some of us are worthier of life than others. That some of us deserve to survive and reproduce, while others do not.

History has shown that this thinking leads us down a dark path.

It also deters us from political action, leaving us to lament the ‘inevitability’ of catastrophic overpopulation and to abandon the optimism necessary for change.

Voices of ‘too many’

In a YouGov survey of almost 8,000 people across eight countries (Brazil, Egypt, France, Hungary, India, Japan, Nigeria and the United States) the most commonly held view was that the current world population was too large.

Respondents in Brazil, Egypt, India and Nigeria felt their domestic fertility rates were too high, even though Brazil and India have fertility rates below 2.1 births per woman – or what experts call the ‘replacement-level’ fertility rate.

Of the eight countries included in the survey, five (Brazil, France, Hungary, Japan and the United States) had more respondents worried about the size of the global population than about the size of their own country’s population.

Changing the narrative

Growing population threatens planet: Are we doomed?

Least responsible, most affected: How climate change harms the world's most vulnerable

National identity under threat by influx of migrants

Inclusive societies are key to developing demographic resilience

To stop climate change, have less children

To stop the climate crisis, corporations must urgently reduce emissions

We don’t have to buy into the narrative that women’s bodies and reproductive choices are the problem and solution to ‘overpopulation’.