Brewminate: A Bold Blend of News and Ideas

- Uncategorized

Jonathan Swift: Master of Satire in the 18th Century

Share this:.

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

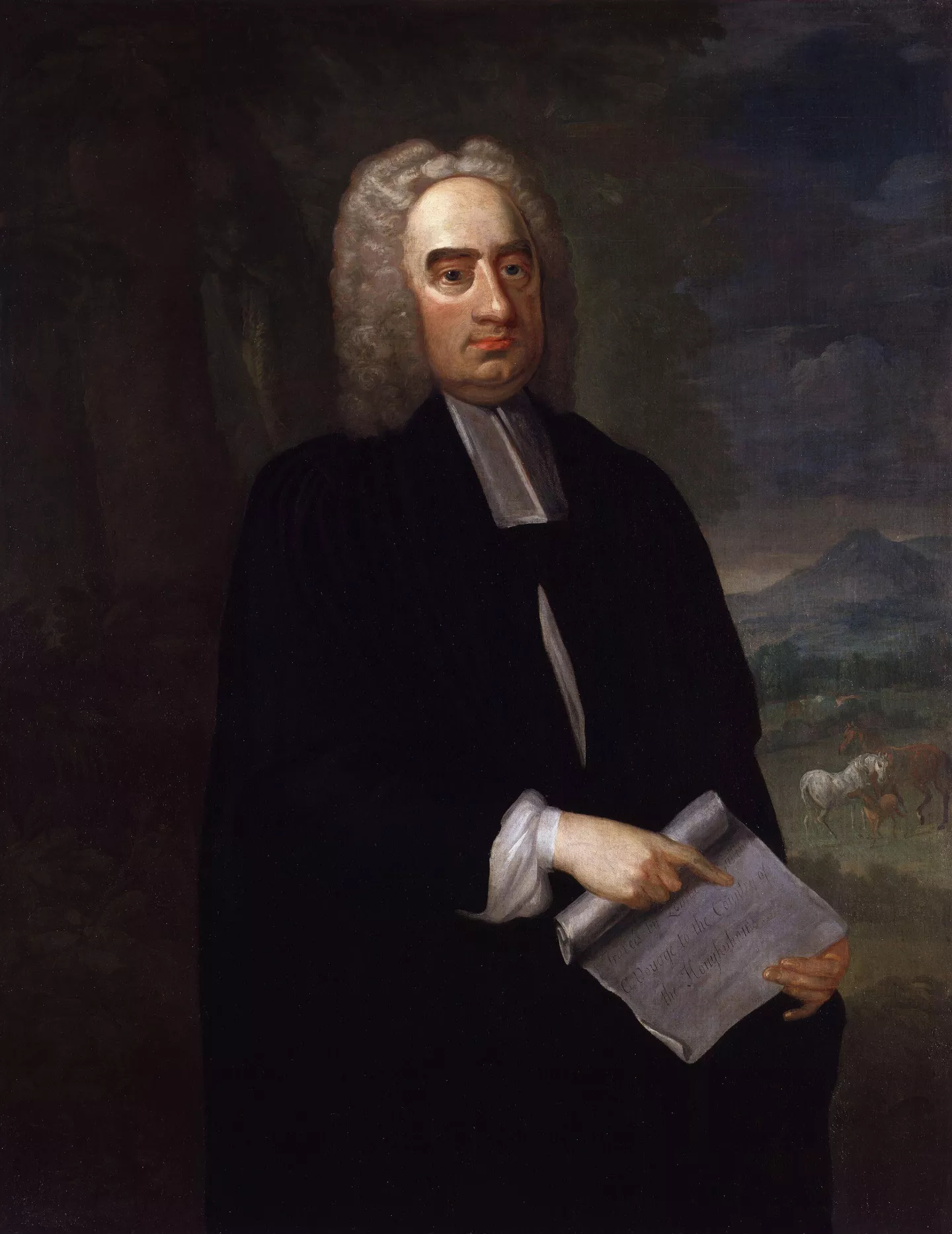

Swift was a heavily politically involved and prolific writer.

Curated/Reviewed by Matthew A. McIntosh Public Historian Brewminate

Introduction

Jonathan Swift (November 30, 1667 – October 19, 1745) was an Anglo-Irish priest, essayist, political writer, and poet, considered the foremost satirist in the English language. Swift’s fiercely ironic novels and essays, including world classics such as Gulliver’s Travels and The Tale of the Tub , were immensely popular in his own time for their ribald humor and imaginative insight into human nature. Swift’s object was to expose corruption and express political and social criticism through indirection.

In his own times, Swift aligned himself with the Tories and became the most prominent literary figure to lend his hand to Tory politics. As a result, Swift found himself in a bitter feud with the other great pamphleteer and essayist of his time, Joseph Addison. Moreover, Swift’s royalist political leanings have made him a semi-controversial figure in his native Ireland, and whether Swift should be categorized as an English or Irish writer remains a point of academic contention. Nevertheless, Swift was, and remains, one of the most popular and readable authors of the eighteenth century, an author of humor and humanity, who is as often enlightening as he is ironical.

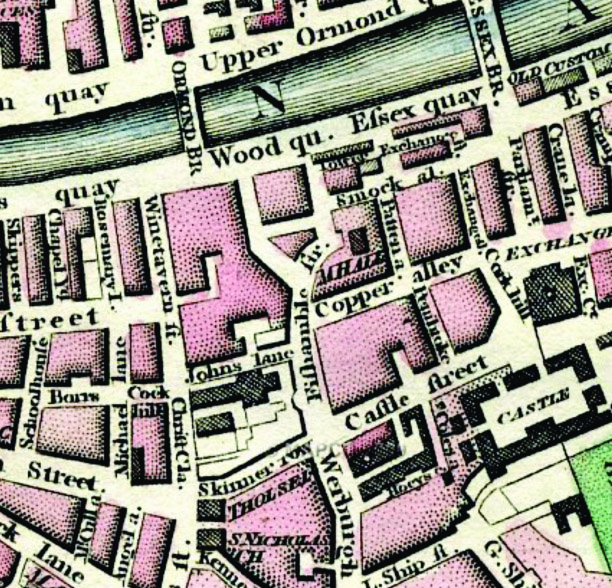

Swift was born at No. 7, Hoey’s Court, Dublin, the second child and only son of Jonathan and Abigail Swift, English immigrants. Jonathan arrived seven months after his father’s untimely death. Most of the facts of Swift’s early life are obscure and sometimes contradictory. It is widely believed that his mother returned to England when Swift was still very young, leaving him to be raised by his father’s family. His uncle Godwin took primary responsibility for the young Swift, sending him to Kilkenny Grammar School with one of his cousins.

In 1682 he attended Trinity College, Dublin, receiving his B.A. in 1686. Swift was studying for his master’s degree when political troubles in Ireland surrounding the Glorious Revolution forced him to leave for England in 1688, where his mother helped him get a position as secretary and personal assistant to Sir William Temple, an English diplomat. Temple arranged the Triple Alliance of 1668, retiring from public service to his country estate to tend his gardens and write his memoirs. Growing into the confidence of his employer, Swift was often trusted with matters of great importance. Within three years of their acquaintance, Temple had introduced his secretary to King William III, and sent him to London to urge the king to consent to a bill for triennial Parliaments.

Swift left Temple in 1690 for Ireland because of his health, but returned the following year. The illness—fits of vertigo or giddiness now widely believed to be Ménière’s disease—would continue to plague Swift throughout his life. During this second stay with Temple, Swift received his M.A. from Oxford University in 1692. Then, apparently despairing of gaining a better position through Temple’s patronage, Swift left Moor Park to be ordained a priest in the Church of Ireland, and was appointed to a small parish near Kilroot, Ireland, in 1694.

Swift was miserable in his new position, feeling isolated in a small, remote community. Swift left his post and returned to England and Temple’s service at Moor Park in 1696 where he remained until Temple’s death. There he was employed in helping prepare Temple’s memoirs and correspondence for publication. During this time Swift wrote The Battle of the Books , a satire responding to critics of Temple’s Essay upon Ancient and Modern Learning (1690) that argued in favor of the classicism of the ancients over the modern “new learning” of scientific inquiry. Swift would not publish The Battle of the Books , however, for another fourteen years.

In the summer of 1699 Temple died. Swift stayed on briefly to finish editing Temple’s memoirs, perhaps in the hope that recognition of his work might earn him a suitable position in England, but this proved ineffectual. His next move was to approach William III directly, based on his imagined connection through Temple and a belief that he had been promised a position. This failed so miserably that he accepted the lesser post of secretary and chaplain to the Earl of Berkeley, one of the Lords Justices of Ireland. However, when he reached Ireland he found that the secretaryship had been given to another. He soon obtained a post as chaplain of Laracor, Agher, and Rathbeggan in St. Patrick’s Cathedral, Dublin. In Laracor, Swift ministered to a congregation of about 15 persons, and he had ample time to pursue his hobbies: gardening, architecture, and above all, writing.

In 1701 Swift had invited his friend Esther Johnson to Dublin. According to rumor Swift married her in 1716, although no marriage was ever acknowledged. Swift’s friendship with Johnson, in any case, lasted through her lifetime, and his letters to Johnson from London between 1710 and 1713 make up his Journal to Stella , first published in 1768.

In February 1702, Swift received his doctor of divinity degree from Trinity College. During his visits to England in these years Swift published A Tale of a Tub and The Battle of the Books (1704) and began to gain a reputation as a writer. This led to close, lifelong friendships with Alexander Pope, John Gay, and John Arbuthnot, forming the core of the Martinus Scriberlus Club, founded in 1713.

Political Involvement

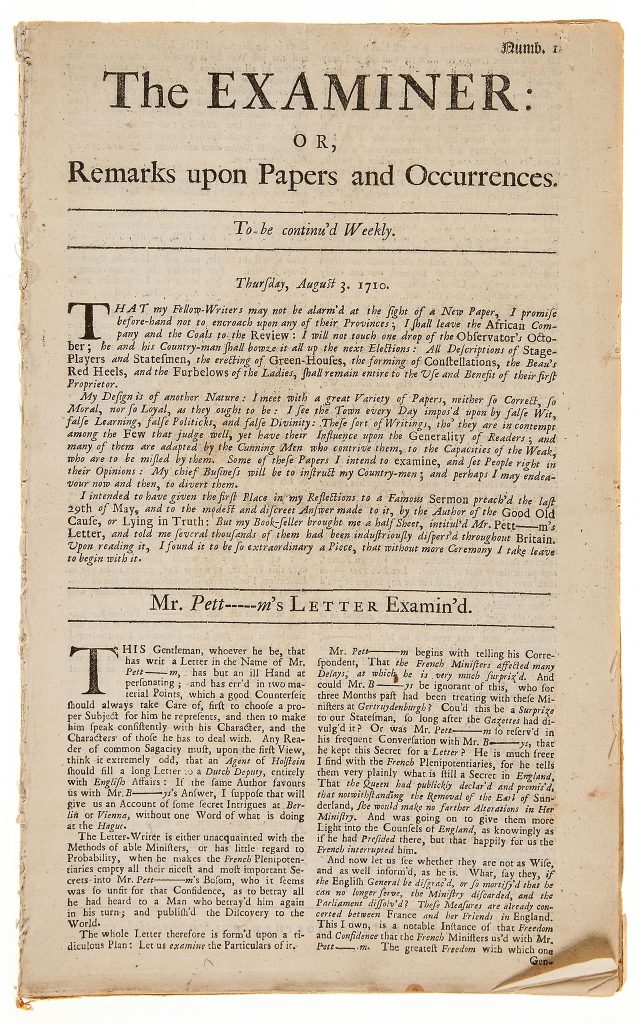

Swift became increasingly active politically in these years. From 1707 to 1709 and again in 1710, Swift was in London, petitioning the Whig Party which he had supported all his life. He found the opposition Tory leadership more sympathetic to his cause and Swift was recruited to support their cause as editor of the Examiner , the principal Tory periodical, when they came to power in 1710. In 1711 Swift published the political pamphlet “The Conduct of the Allies,” attacking the Whig government for its inability to end the prolonged war with France.

Swift was part of the inner circle of the Tory government, often acting as mediator between the prime minister and various other members of Parliament. Swift recorded his experiences and thoughts during this difficult time in a long series of letters, later collected and published as The Journal to Stella . With the death of Queen Anne and ascension of King George that year, the Whigs returned to power and the Tory leaders were tried for treason for conducting secret negotiations with France.

Before the fall of the Tory government, Swift hoped that his services would be rewarded with a church appointment in England. However, Queen Anne appears to have taken a dislike to Swift and thwarted these efforts. The best position his friends could secure for him was the deanery of St. Patrick’s, Dublin. With the return of the Whigs, Swift’s best move was to leave England, so he returned to Ireland in disappointment, a virtual exile, to live, he said, “like a rat in a hole.”

Once in Ireland, however, Swift began to turn his pamphleteering skills in support of Irish causes, producing some of his most memorable works: “Proposal for Universal Use of Irish Manufacture” (1720), “The Drapier’s Letters” (1724), and most famously, “A Modest Proposal” (1729), a biting parody of economic utilitarianism he associated with the Whigs. Swift’s pamphlets on Irish issues made him into something of a national hero in Ireland, despite his close association with the Tories and his ethnic English background.

Also during these years, Swift began writing his masterpiece, Travels into Several Remote Nations of the World, in Four Parts, by Lemuel Gulliver, first a surgeon, and then a captain of several ships , better known as Gulliver’s Travels . In 1726 he paid a long-deferred visit to London, taking with him the manuscript of Gulliver’s Travels . During his visit he stayed with his old friends, Alexander Pope, John Arbuthnot, and John Gay, who helped him arrange for the anonymous publication of his book. First published in November 1726, it was an immediate hit, with a total of three printings that year and another in early 1727. French, German, and Dutch translations appeared in 1727 and pirated copies were printed in Ireland.

Swift returned to England one more time in 1727, staying with Alexander Pope once again. In 1738 Swift began to show signs of illness and in 1742 he appears to have suffered a stroke, losing the ability to speak and realizing his worst fears of becoming mentally disabled (“I shall be like that tree,” he once said, “I shall die at the top”). On October 19, 1745, Swift died. The bulk of his fortune was left to found a hospital for the mentally ill.

Major Prose

Swift was a prolific writer. The most recent collection of his prose works (Herbert Davis, ed., Basil Blackwell, 1965) comprises fourteen volumes. A recent edition of his complete poetry (Pat Rodges, ed., Penguin, 1983) is 953 pages long. One edition of his correspondence (David Woolley, ed., P. Lang, 1999) fills three volumes.

In 1708, when a cobbler named John Partridge published a popular almanac of astrological predictions, Swift attacked Partridge in Prediction For The Ensuing Year , a parody predicting that Partridge would die on March 29. Swift followed up with a pamphlet issued on March 30 claiming that Partridge had in fact died, which was widely believed despite Partridge’s statements to the contrary.

Swift’s first major prose work, A Tale of a Tub , demonstrates many of the themes and stylistic techniques he would employ in his later work. It is at once wildly playful and humorous while at the same time pointed and harshly critical of its targets. The Tale recounts the exploits of three sons, representing the main threads of Christianity in England: the Anglican, Catholic, and Nonconformist (“Dissenting”) Churches. Each of the sons receives a coat from their fathers as a bequest, with the added instructions to make no alternations to the coats whatsoever. However, the sons soon find that their coats have fallen out of current fashion and begin to look for loopholes in their father’s will which will allow them to make the needed alterations. As each finds his own means of getting around their father’s admonition, Swift satirizes the various changes (and corruptions) that had consumed all three branches of Christianity in Swift’s time. Inserted into this story, in alternating chapters, Swift includes a series of whimsical “discourses” on various subjects.

In 1729, Swift wrote “A Modest Proposal,” supposedly written by an intelligent and objective “political arithmetician” who had carefully studied Ireland before making his proposal. The author calmly suggests one solution for both the problem of overpopulation and the growing numbers of undernourished people: breed those children who would otherwise go hungry or be mistreated and sell them as food for the rich.

Gulliver’s Travels

Gulliver’s Travels (published 1726, amended 1735), officially titled Travels into Several Remote Nations of the World is Swift’s masterpiece, both a satire on human nature and a parody of the “travellers’ tales” literary sub-genre. It is easily Swift’s most celebrated work and one of the indisputable classics of the English language.

The book became tremendously popular as soon as it was published (Alexander Pope quipped that “it is universally read, from the cabinet council to the nursery”) and it is likely that it has never been out of print since its original publication. George Orwell went so far as to declare it to be among the six most indispensable books in world literature.

On his first voyage, Gulliver is washed ashore after a shipwreck, awaking to find himself a prisoner of a race of tiny people who stand 15 centimeters high, inhabitants of the neighboring and rival countries of Lilliput and Blefuscu. After giving assurances of his good behavior he is given a residence in Lilliput, becoming a favorite of the court. He assists the Lilliputians in subduing their neighbors, the Blefuscudans, but refuses to reduce Blefuscu to a province of Lilliput, so he is charged with treason and sentenced to be blinded. Fortunately, Gulliver easily overpowers the Lilliputian army and escapes back home.

On his second voyage, while exploring a new country, Gulliver is abandoned by his companions, finding himself in Brobdingnag, a land of giants. He is then bought (as a curiosity) by the queen of Brobdingnag and kept as a favorite at court. On a trip to the seaside, his ship is seized by a giant eagle and dropped into the sea where he is picked up by sailors and returned to England.

On his third voyage, Gulliver’s ship is attacked by pirates and he is abandoned on a desolate rocky island. Fortunately he is rescued by the flying island of Laputa, a kingdom devoted to the intellectual arts that is utterly incapable of doing anything practical. While there, he tours the country as the guest of a low-ranking courtier and sees the ruin brought about by blind pursuit of science without practical results. He also encounters the Struldbrugs, an unfortunate race who are cursed to have immortal life without immortal youth. The trip is otherwise reasonably free of incident and Gulliver returns home, determined to stay a homebody for the rest of his days.

Disregarding these intentions at the end of the third part, Gulliver returns to sea where his crew promptly mutinies. He is abandoned ashore, coming first upon a race of hideously deformed creatures to which he conceives a violent antipathy. Shortly thereafter he meets an eloquent, talking horse and comes to understand that the horses (in their language “Houyhnhnm”) are the rulers and the deformed creatures (“Yahoos”) are in fact human beings. Gulliver becomes a member of the horse’s household, treated almost as a favored pet, and comes to both admire and emulate the Houyhnhnms and their lifestyle, rejecting human beings as merely Yahoos endowed with some semblance of reason which they only use to exacerbate and add to the vices Nature gave them. However, an assembly of the Houyhnhnms rules that Gulliver, a Yahoo with some semblance of reason, is a danger to their civilization, so he is expelled. He is then rescued, against his will, by a Portuguese ship that returns him to his home in England. He is, however, unable to reconcile himself to living among Yahoos; he becomes a recluse, remaining in his house, largely avoiding his family, and spending several hours a day speaking with the horses in his stables.

Swift once stated that “satire is a sort of glass, wherein beholders do generally discover everybody’s face but their own.” Utilizing grotesque logic—for example, that Irish poverty can be solved by the breeding of infants as food for the rich—Swift commented on attitudes and policies of his day with an originality and forcefulness that influenced later novelists such as Mark Twain, H. G. Wells, and George Orwell. “Swiftian” satire is a term coined for especially outlandish and sardonic parody.

Although his many pamphlets and attacks on religious corruption and intellectual laziness are dated for most modern readers, Gulliver’s Travels has remained a popular favorite both for its humorous rendering of human foibles and its adventurous fantasy.

Originally published by New World Encyclopedia , 06.05.2018, under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported license.

Jonathan Swift

A short biography of jonathan swift, later years, jonathan swift’s writing style, great satirist, ironic and satirical tone for social construction.

Certainly, the works and writings of Jonathan Swift do not focus on the technicalities of language. It rather focuses on the satirical tone and harsh irony in his satire. In A Modest Proposal, Jonathan Swift skillfully imitates and awfully pessimistic policymaker or an economist. In the essay, he satirically advocates the case of eating children of Ireland as a solution to the problems of poverty and overpopulation. Throughout the essay, Jonathan Swift abstains from his altering the role of the character, which is so straight-faced. It creates an absurd sarcasm.

“….if a resolution could now be taken to buy only our native goods, would immediately unite to cheat and exact upon us in the price, the measure, and the goodness, nor could ever yet be brought to make one fair proposal of just dealing, though often and earnestly invited to it.”

Format of Writing

Works of jonathan swift.

24/7 writing help on your phone

To install StudyMoose App tap and then “Add to Home Screen”

The Art of Jonathan Swift's Prose: an Overview

Save to my list

Remove from my list

The Simplicity of Swift's Style

The Common Touch

Invention and imagination, authenticity through archaic language, detail and realism, the power of swift's satire.

The Art of Jonathan Swift's Prose: an Overview. (2016, Jun 20). Retrieved from https://studymoose.com/jonathan-swifts-style-of-writing-essay

"The Art of Jonathan Swift's Prose: an Overview." StudyMoose , 20 Jun 2016, https://studymoose.com/jonathan-swifts-style-of-writing-essay

StudyMoose. (2016). The Art of Jonathan Swift's Prose: an Overview . [Online]. Available at: https://studymoose.com/jonathan-swifts-style-of-writing-essay [Accessed: 30 Jul. 2024]

"The Art of Jonathan Swift's Prose: an Overview." StudyMoose, Jun 20, 2016. Accessed July 30, 2024. https://studymoose.com/jonathan-swifts-style-of-writing-essay

"The Art of Jonathan Swift's Prose: an Overview," StudyMoose , 20-Jun-2016. [Online]. Available: https://studymoose.com/jonathan-swifts-style-of-writing-essay. [Accessed: 30-Jul-2024]

StudyMoose. (2016). The Art of Jonathan Swift's Prose: an Overview . [Online]. Available at: https://studymoose.com/jonathan-swifts-style-of-writing-essay [Accessed: 30-Jul-2024]

- Jonathan Swift's satire "A Modest Proposal..." Pages: 3 (664 words)

- Masters of Satire: John Dryden and Jonathan Swift Pages: 2 (376 words)

- Commentary on Jonathan Swift's Essay "A Modest Proposal" Pages: 3 (700 words)

- The satire A modest proposal by Jonathan Swift Pages: 5 (1453 words)

- Jonathan Swift and Gulliver’s Travels Pages: 14 (3973 words)

- Irish Oppression and Modern Parallels in A Modest Proposal by Jonathan Swift Pages: 5 (1438 words)

- Jonathan Swift's Satirical Proposal: Eating Children to Combat Poverty Pages: 5 (1498 words)

- The Hunger Games by Suzanne Collins Vs. A Modest Proposal by Jonathan Swift Pages: 6 (1588 words)

- An Analysis of Jonathan Swift’s “A Modest Proposal” Pages: 2 (557 words)

- Gulliver's Travels by Jonathan Swift Analysis Pages: 2 (380 words)

👋 Hi! I’m your smart assistant Amy!

Don’t know where to start? Type your requirements and I’ll connect you to an academic expert within 3 minutes.

- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- Games & Quizzes

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

Jonathan Swift

- Share on Twitter

- Share on Facebook

- Print this page

- Email this page

Anglo-Irish poet, satirist, essayist, and political pamphleteer Jonathan Swift was born in Dublin, Ireland. He spent much of his early adult life in England before returning to Dublin to serve as Dean of St. Patrick’s Cathedral, Dublin for the last 30 years of his life. It was this later stage when he would write most of his greatest works. Best known as the author of A Modest Proposal (1729), Gulliver’s Travels (1726), and A Tale Of A Tub (1704), Swift is widely acknowledged as the greatest prose satirist in the history of English literature.

Swift’s father died months before Jonathan was born, and his mother returned to England shortly after giving birth, leaving Jonathan in the care of his uncle in Dublin. Swift’s extended family had several interesting literary connections: his grandmother, Elizabeth (Dryden) Swift, was the niece of Sir Erasmus Dryden, grandfather of the poet John Dryden. The same grandmother’s aunt, Katherine (Throckmorton) Dryden, was a first cousin of Elizabeth, wife of Sir Walter Raleigh. His great-great grandmother, Margaret (Godwin) Swift, was the sister of Francis Godwin, author of The Man in the Moone , which influenced parts of Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels . His uncle, Thomas Swift, married a daughter of the poet and playwright Sir William Davenant, a godson of William Shakespeare . Swift’s uncle served as Jonathan’s benefactor, sending him to Trinity College Dublin, where he earned his BA and befriended writer William Congreve. Swift also studied toward his MA before the Glorious Revolution of 1688 forced Jonathan to move to England, where he would work as a secretary to a diplomat. He would earn an MA from Hart Hall, Oxford University, in 1692, and eventually a Doctor in Divinity degree from Trinity College Dublin in 1702.

Swift’s poetry has a relationship either by interconnections with, or by reactions against, the poetry of his contemporaries and predecessors. He was probably influenced, in particular, by the Restoration writers John Wilmot , Earl of Rochester and Samuel Butler (who shared Swift’s penchant for octosyllabic verse). He may have picked up pointers from the Renaissance poets John Donne and Sir Philip Sidney . Beside these minor borrowings of his contemporaries, his debts are almost negligible. In the Augustan Age, an era which did not necessarily value originality above other virtues, his poetic contribution was strikingly original.

In reading Swift’s poems, one is first impressed with their apparent spareness of allusion and poetic device. Anyone can tell that a particular poem is powerful or tender or vital or fierce, but literary criticism seems inadequate to explain why. A few recent critics have carefully studied his use of allusion and image, but with only partial success. It still seems justified to conclude that Swift’s straightforward poetic style seldom calls for close analysis, his allusions seldom bring a whole literary past back to life, and his images are not very interesting in themselves. In general, Swift’s verses read faster than John Dryden ’s or Alexander Pope ’s, with much less ornamentation and masked wit. He apparently intends to sweep the reader along by the logic of the argument to the several conclusions he puts forth. He seems to expect that the reader will appreciate the implications of the argument as a whole, after one full and rapid reading. For Swift’s readers, the couplet will not revolve slowly upon itself, exhibiting intricate patterns and fixing complex relationships between fictive worlds and contemporary life.

The poems are not always as spare in reality as Swift would have his readers believe, but he seems deliberately to induce in them an unwillingness to look closely at the poems for evidence of technical expertise. He does this in part by working rather obviously against some poetic conventions, in part by saying openly that he rejects poetic cant, and in part by presenting himself—in many of his poems—as a perfectly straightforward man, incapable of a poet’s deviousness. By these strategies, he directs attention away from his handling of imagery and meter, even in those instances where he has been technically ingenious. For the most part, however, the impression of spareness is quite correct; and if judged by the sole criterion of technical density, then he would have to be judged an insignificant poet. But technical density is a poetic virtue only as it simulates and accompanies subtlety of thought. One could argue that Swift’s poems create a density of another kind: that “The Day of Judgement,” for example, initiates a subtle process of thought that takes place after, rather than during, the reading of the poem, at a time when the mind is more or less detached from the printed page. One could argue as well that Swift makes up in power what he lacks in density: that the strength of the impression created by his directness gives an impetus to prolonged meditation of a very high quality. On these grounds, valuing Swift for what he really is and does, one must judge him a major figure in poetry as well as prose.

Swift suffered a stroke in 1742, leaving him unable to speak. He died three years later, and was buried at St. Patrick’s Cathedral, Dublin.

Advice to the Grub Street Verse-writers

The beasts' confession, a beautiful young nymph going to bed.

- See All Poems by Jonathan Swift

- See All Related Content

- Ireland & Northern Ireland

- Poems by This Poet

Bibliography

A description of a city shower, a description of the morning, the lady’s dressing room, market women’s cries, on stella's birth-day, a satirical elegy on the death of a late famous general, stella's birthday march 13, 1727, to quilca, a country house not in good repair, verses on the death of dr. swift, d.s.p.d..

Why the 18th-century Laetitia Pilkington is a heroine for today.

Selected Books

- A Discourse Of The Contests and Dissensions Between The Nobles and the Commons In Athens and Rome, With The Consequences they had upon both those States (London: Printed for John Nutt, 1701; Boston, 1728).

- A Tale Of A Tub, Written for the Universal Improvement of Mankind. Diu multumque desideratum. To which is added, An Account of a Battel Between the Antient and Modern Books in St. James's Library (London: Printed for John Nutt, 1704); enlarged as A Tale of a Tub ... The Fifth Edition: With the Author's Apology and Explanatory Notes (London: Printed for John Nutt, 1710).

- A Project For The Advancement of Religion, And the Reformation of Manners (London: Printed for Benj. Tooke, 1709).

- Baucis and Philemon, Imitated from Ovid (N.p., 1709).

- A Meditation Upon A Broom-Stick, and Somewhat Beside; Of The Same Author's (London: Printed for E. Curll & sold by J. Harding, 1710).

- The Examiner, by Swift and others, 6 volumes (London: Printed for John Morphew, 1710-1714).

- Miscellanies in Prose and Verse (London: Printed for John Morphew, 1711; enlarged edition, 5 volumes, London: Printed for Benjamin Motte, Lawton Gilliver & Charles Davis, 1727-1735).

- The Conduct Of The Allies, And Of The Late Ministry, In Beginning and Carrying on The Present War (London: Printed for John Morphew, 1712 [i.e., 1711]).

- The Fable of Midas (London: Printed for John Morphew, 1712).

- A Proposal For Correcting, Improving and Ascertaining The English Tongue; In A Letter To the Most Honourable Robert Earl of Oxford and Mortimer, Lord High Treasurer of Great Britain (London: Printed for Benj. Tooke, 1712).

- Part of the Seventh Epistle Of The First Book Of Horace Imitated: And Address'd to a Noble Peer (London: Printed for A. Dodd, 1713).

- The First Ode Of The Second Book Of Horace Paraphras'd: And Address'd to Richard St--le, Esq (London: Printed for A. Dodd, 1713).

- The Lucubrations Of Isaac Bickerstaff Esq., 5 volumes (London: Printed for E. Nutt, A. Bell, J. Darby, A. Bettesworth, J. Pemberton, J. Hooke, C. Rivington, R. Cruttenden, T. Cox, J. Battley, F. Clay & E. Simon, 1720).

- The Bubble: A Poem (London: Printed for Benj. Tooke & sold by J. Roberts, 1721).

- Apollo's Edict (N.p., 1721).

- Fraud Detected; Or, The Hibernian Patriot. Containing, All the Drapier's Letters to the People of Ireland, on Wood's Coinage, &c. (Dublin: Reprinted & sold by George Faulkner, 1725).

- The Birth Of Manly Virtue From Callimachus (Dublin: Printed by & for George Grierson, 1725).

- Cadenus and Vanessa. A Poem (Dublin, 1726).

- Travels Into Several Remote Nations Of The World. In Four Parts. By Lemuel Gulliver, First a Surgeon, and then a Captain of several Ships, 2 volumes (London: Printed for Benj. Motte, 1726); enlarged as Travels Into Several Remote Nations Of The World ... To which are prefix'd, Several Copies of Verses Explanatory and Commendatory; never before printed, 2 volumes (London: Printed for Benj. Motte, 1728).

- The Intelligencer, by Swift and others (Dublin: Printed by S. Harding, II May 1728-7 May 1729; collected edition, London: Printed for Francis Cogan, 1730).

- A Modest Proposal For preventing the Children Of Poor People From being a Burthen to their Parents, Or The Country, And For making them Beneficial to the Publick (Dublin: Printed by S. Harding, 1729).

- An Epistle Upon An Epistle From a certain Doctor To a certain great Lord: Being A Christmas-Box for D.D---y (Dublin, 1730).

- An Epistle To His Excellency John Lord Carteret, Lord Lieutenant of Ireland (Dublin, 1730).

- A Libel On D--------D-------And A Certain Great Lord (N.p., 1730).

- Lady A--S--N Weary of the Dean [single sheet] (N.p., 1730).

- A Panegyric On the Reverend Dean Swift (London: Printed for J. Roberts & N. Blandford, 1730).

- An Apology To The Lady C--R--T (N.p., 1730).

- Horace Book I. Ode XIV. O navis, referent, &c. Paraphrased and inscribed to Ir--d (N.p., 1730).

- Traulus ... In A Dialogue Between Tom and Robin, 2 volumes (N.p., 1730).

- A Soldier And A Scholar: Or The Lady's Judgment Upon those two Characters In the Persons of Captain---and D--n S--T (London: Printed for J. Roberts, 1732); republished as The Grand Question debated (London: Printed by A. Moore, 1732).

- An Elegy On Dicky and Dolly, With the Virgin: A Poem. To which is Added The Narrative of D. S. when he was in the North of Ireland (Dublin: Printed by James Hoey, 1732).

- The Lady's Dressing Room (London: Printed for J. Roberts, 1732).

- The Life And Genuine Character Of Doctor Swift, Written by Himself (London: Printed for J. Roberts, 1733).

- An Epistle To A Lady, Who desired the Author to make Verses on Her, In The Heroick Stile. Also A Poem, Occasion'd by Reading Dr. Young's Satires, Called the Universal Passion (Dublin & London: Printed for J. Wilford, 1734 [i.e., 1733]).

- On Poetry: A Rapsody (Dublin & London: Printed & sold by J. Huggonson, 1733).

- A Beautiful Young Nymph Going to Bed. Written for the Honour of the Fair Sex. Pars minima est ipsa Puella sui. Ovid Remed. Amoris. To Which Are Added, Strephon and Chloe. And Cassinus and Peter (Dublin & London: Printed for J. Roberts, 1734).

- The Works of J. S, D.D, D.S.P.D., 4 volumes (Dublin: Printed by & for George Faulkner, 1735; enlarged to 20 volumes, 1738-1772).

- An Imitation Of The Sixth Satire Of The Second Book Of Horace, by Swift and Alexander Pope (London: Printed for B. Motte, C. Bathurst & J. & P. Knapton, 1738).

- The Beasts Confession To The Priest, On Observing how most Men mistake their own Talents. Written in the Year 1732 (Dublin: Printed by George Faulkner, 1738).

- A Complete Collection Of Genteel and Ingenious Conversation, According to the Most Polite Mode and Method Now Used at Court, and in the Best Companies of England. In Three Dialogues, as Simon Wagstaff (London: Printed for B. Motte & C. Bathurst, 1738); also published as A Treatise On Polite Conversation (Dublin: Printed by & for George Faulkner, 1738); dramatized as Tittle Tattle; Or, Taste A-la-Mode. A New Farce. Perform'd with Universal Applause by a Select Company Of Belles and Beaux, At The Lady Brilliant's Withdrawing-Room, as Timothy Fribble (London: Printed for R. Griffiths, 1749).

- Verses On The Death Of Dr. Swift. Written by Himself: Nov. 1731 (London: Printed for C. Bathurst, 1739).

- Directions To Servants (Dublin: Printed by George Faulkner, 1745); enlarged as Directions To Servants In General (London: Printed for R. Dodsley & M. Cooper, 1745).

- The Last Will And Testament Of Jonathan Swift, D.D. (Dublin & London: Printed & sold by M. Cooper, 1746).

- D--n Sw--t's Medley (Dublin & London: Printed & sold by the booksellers, 1749).

- The History of the Four Last Years of the Queen (London: Printed for A. Millar, 1758).

Editions and Collections

- The Works Of Dr. Jonathan Swift, 14 volumes (London: Printed for C. Bathurst, 1751).

- The Works Of D. Jonathan Swift ... To which is prefixed, The Doctor's Life, with Remarks on his Writings, from the Earl of Orrery and others, not to be found in any former Edition of his Works, 9 volumes (Dublin & Edinburgh: Printed for G. Hamilton, J. Balfour & L. Hunter, 1752).

- The Works of Dr. Jonathan Swift ... With Some Account of the Author's Life, And Notes Historical and Explanatory, edited by John Hawkesworth, Deane Swift, and John Nichols, 27 volumes (London: Printed for C. Bathurst, 1754-1779).

- The Sermons of the Reverend Dr. Jonathan Swift (Glasgow: Printed for Robert Urie, 1763).

- The Works Of The Rev. Dr. Jonathan Swift ... Arranged, Revised, And Corrected, With Notes, edited by Thomas Sheridan, 17 volumes (London: Printed for C. Bathurst, 1784); corrected and revised by Nichols, 24 volumes (London: Printed for J. Johnson, John Nichols &Son, 1803; New York: Durell, 1812).

- The Poetical Works, of Jonathan Swift, edited by Thomas Park, 4 volumes (London: Printed by Charles Whittingham for J. Sharpe & sold by W. Suttaby, 1806).

- The Works Of Jonathan Swift ... Containing Additional Letters, Tracts, And Poems, Not Hitherto Published; With Notes, And A Life Of The Author, edited by Sir Walter Scott, 19 volumes (Edinburgh: Printed for Archibald Constable & Co., 1814).

- The Works of Jonathan Swift ... Containing Interesting and Valuable Papers, Not Hitherto Published, edited by Thomas Roscoe, 2 volumes (London: Washbourne, 1841).

- The Poems of Jonathan Swift, edited by Harold Williams, 3 volumes (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1937; revised, 1958).

- Collected Poems of Jonathan Swift, edited by Joseph Horrell, 2 volumes (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul / Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1958).

- Swift: Poetical Works, edited by Herbert Davis (Oxford: Standard Authors; London: Oxford University Press, 1967).

- Gulliver's Travels, edited by Robert A. Greenberg (New York: Norton, 1970).

- Jonathan Swift: The Complete Poems, edited by Pat Rogers (London: Penguin Books / New Haven: Yale University Press, 1983).

- "Ode to the Athenian Society," in The Supplement To The Fifth Volume Of The Athenian Gazette (London: Printed for John Dunton, 1692).

- Memoirs Of Capt. John Creichton. Written by Himself, edited by Swift (N.p., 1731).

- "The Legion Club," in S---t contra omnes. An Irish Miscellany (Dublin & London: Sold by R. Amy & Mrs. Dodd, 1736).

- Letters Between Dr. Swift, Mr. Pope, &c. From the Year 1714 to 1736. Publish'd from a Copy Transmitted from Dublin (London: T. Cooper, 1741).

- The Works of Mr. Alexander Pope, In Prose, volume 2, includes letters by Swift (London: J. & P. Knapton, C. Bathurst & R. Dodsley, 1741).

- Letters To and From Dr. J. Swift, D.S.P.D. From The Year 1714, to 1738 (Dublin: George Faulkner, 1741).

- The Correspondence of Jonathan Swift, D.D., edited by F. Elrington Ball, 6 volumes (London: Bell, 1910-1914).

- The Correspondence of Jonathan Swift, edited by Harold Williams, 5 volumes (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1963-1965).

" Cambridge University Library houses the great Rothschild collection of Swift materials. The Forster collection, at the Victoria and Albert Museum, was put together toward the end of the nineteenth century by John Forster, who intended to write a biography of Swift but died after publishing only one volume. The materials gathered by Swift 's most famous bibliographer, Herman Teerink, are deposited at the University of Pennsylvania. Some of the items in Teerink's personal collection were destroyed during World War II and so were not available to his bibliographical successor, Arthur H. Scouten.

Further Readings

- Herman Teerink, A Bibliography of the Writings in Prose and Verse of Jonathan Swift, D.D. (The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff, 1937); revised and corrected by Teerink and edited by Arthur H. Scouten as A Bibliography of the Writings of Jonathan Swift (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1963).

- Louis A. Landa and James Edward Tobin, Jonathan Swift: A List of Critical Studies Published from 1895 to 1945. To Which Is Added Remarks on Some Swift Manuscripts in the United States by Herbert Davis (New York: Cosmopolitan Science and Art Service, 1945).

- Ricardo Quintana, "A Modest Appraisal: Swift Scholarship and Criticism, 1945-65," in Fair Liberty Was All His Cry: A Tercentenary Tribute to Jonathan Swift 1667-1745, edited by A. Norman Jeffares (London: Macmillan / New York: St. Martin's, 1967), pp. 342-355.

- James J. Stathis, A Bibliography of Swift Studies 1945-1965 (Nashville: Vanderbilt University Press, 1967).

- David M. Vieth, Swift's Poetry 1900-1980: An Annotated Bibliography of Studies (New York & London: Garland, 1982).

- Richard H. Rodino, Swift Studies, 1965-1980: An Annotated Bibliography (New York & London: Garland, 1984).

- Laetitia Pilkington, Memoirs Of Mrs. Laetitia Pilkington, Written by Herself. With Anecdotes of Dean Swift (Dublin & London: R. Griffiths & G. Woodfall, 1748).

- John Boyle, Earl of Cork and Orrery, Remarks On The Life and Writings Of Dr. Jonathan Swift, Dean of St. Patrick's, Dublin, In a Series of Letters from John Earl of Orrery To his Son, the Honourable Hamilton Boyle (London: A. Millar, 1752).

- Patrick Delany, Observations Upon Lord Orrery's Remarks On The Life and Writings Of Dr. Jonathan Swift, &c. To which are added, Two Original Pieces never before publish'd (London: W. Reeve, 1754).

- John Hawkesworth, The Life Of the Revd. Jonathan Swift, D.D. Dean of St. Patrick's, Dublin (London & Dublin: S. Cotter, 1755).

- Samuel Johnson, "Life of Swift," in his Prefaces, Biographical and Critical, To The Works Of The English Poets, 10 volumes (London: J. Nichols, 1779-1781), VIII: 1-112.

- Thomas Sheridan, The Life Of The Rev. Dr. Jonathan Swift, Dean Of St. Patrick's, Dublin (London: C. Bathurst, 1784).

- Sir Walter Scott, Memoirs Of Jonathan Swift, D.D. Dean Of St. Patrick's, Dublin, 2 volumes (Paris: Galignani, 1826).

- John Middleton Murry, Jonathan Swift: A Critical Biography (London: Cape, 1954).

- Irvin Ehrenpreis, Swift: The Man, His Works, and the Age, 3 volumes (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1962-1983).

- John M. Aden, "Corinna and the Sterner Muse of Swift," English Language Notes, 4 (1966): 23-31.

- F. Elrington Ball, Swift's Verse: An Essay (London: John Murray, 1929; New York: Octagon Books, 1970).

- Louise K. Barnett, Swift's Poetic Worlds (Newark: University of Delaware Press / London & Toronto: Associated University Presses, 1981).

- J. A. Downie, Jonathan Swift: Political Writer (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1985).

- A. B. England, Energy and Order in the Poetry of Swift (Lewisburg, Pa.: Bucknell University Press / London & Toronto: Associated University Presses, 1980).

- John Irwin Fischer, On Swift's Poetry (Gainesville: University Presses of Florida, 1978).

- Fischer and Donald C. Mell, Jr., eds., Contemporary Studies of Swift's Poetry (Newark: University of Delaware Press / London & Toronto: Associated University Presses, 1980).

- Aldous Huxley, "Swift," in his Do What You Will (Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday, Doran, 1929), pp. 99-112.

- Nora Crow Jaffe, The Poet Swift (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England, 1977).

- Maurice Johnson, The Sin of Wit: Jonathan Swift as a Poet (Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 1950).

- Johnson, "Swift's Poetry Reconsidered," in English Writers of the Eighteenth Century, edited by John M. Middendorf (New York, 1971), pp. 233-248.

- Timothy Leonard Keegan, "The Theory and Practice of Swift's Poetry," Ph.D. dissertation, University of Virginia, 1979.

- Felicity A. Nussbaum, The Brink of All We Hate: English Satires on Women 1660-1750 (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1984).

- Brendan O Hehir, "Meaning in Swift's Description of a City Shower," ELH, 27 (1960): 194-207.

- Peter J. Schakel, The Poetry of Jonathan Swift: Allusion and the Development of a Poetic Style (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1978).

- Michael Shinagel, A Concordance to the Poems of Jonathan Swift (Ithaca, N.Y. & London: Cornell University Press, 1972).

- W. B. C. Watkins, Perilous Balance: The Tragic Genius of Swift, Johnson, & Sterne (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1939).

- Audio Poems

- Audio Poem of the Day

- Twitter Find us on Twitter

- Facebook Find us on Facebook

- Instagram Find us on Instagram

- Facebook Find us on Facebook Poetry Foundation Children

- Twitter Find us on Twitter Poetry Magazine

- Privacy Policy

- Terms of Use

- Poetry Mobile App

- 61 West Superior Street, Chicago, IL 60654

- © 2024 Poetry Foundation

Jonathan Swift

Francis bindon, national portrait gallery.

Jonathan Swift (30 November 1667– 19 October 1745) was an Anglo-Irish satirist, essayist, political pamphleteer (first for the Whigs, then for the Tories), poet and cleric who became Dean of St Patrick’s Cathedral, Dublin. Swift is remembered for works such as Gulliver’s Travels, A Modest Proposal, A Journal to Stella, Drapier’s Letters, The Battle of the Books, An Argument Against Abolishing Christianity and A Tale of a Tub. He is regarded by the Encyclopædia Britannica as the foremost prose satirist in the English language, and is less well known for his poetry.

#IrishWriters

Jonathan Swift

Some important facts of his life, some important works of jonathan swift, jonathan swift’s impacts on future literature, famous quotes, related posts:, post navigation.

Satire in “A Modest Proposal” by Jonathan Swift Essay

- To find inspiration for your paper and overcome writer’s block

- As a source of information (ensure proper referencing)

- As a template for you assignment

Introduction

It is imperative to note that “A Modest Proposal” is one of the most well-known satirical works by Jonathan Swift. The author provides a suggestion that would help to improve the economy of the country. The idea that poor children can be sold for food is quite shocking and could not be taken seriously. However, Swift wanted it to sound comprehensive and used numerous approaches to keep the attention of readers. It would be beneficial to analyze utilized writing techniques to get a better understanding of how he tries to convince the audience.

The essay starts with a serious tone, and the author discusses critical issues that families had to deal with at that time, and one could think that it is an actual proposal. The first surprise is the solution to the problem that is listed. One could believe that the author would switch the style immediately once it has been revealed. However, he tries to sound humorless and does not change the style. The fact that he provides numbers and calculations is also intriguing and increases the comedic value of the work. He may mock some of the proposals that were made and absurdity of given solutions. Moreover, it is known that he published it anonymously to ensure that the reader is not aware of what to expect from this proposal.

Another surprise is that the author has switched from one tone to another before the end of this piece. He addresses politicians directly by pointing out that it is their fault that such issues are present. He lists problems such as unfair treatment by landlords, incredibly high prices for rent. Also, he states that they are not protected from the outside environment and have nowhere to go. Furthermore, I have realized that Swift provides real solutions to the problem in this paragraph. He believes that the government should develop a broad range of policies that would improve the living conditions of these people. Also, he suggests that particular shelters should be available, so they do not have to sleep on the streets (Swift, 1729).

The consumption of children can be viewed as a metaphor for oppression, and Swift pointed out that it was happening (Sayre, 2011). He changes the tone yet again in the final paragraph where he tries to appear completely innocent and states that he has no personal interests. It is necessary to note that such a surprise ending was not expected, and one could think that Swift is leading to a particular twist. However, he does not change the initial statement and achieves comedy through being serious about something that may not be regarded as reasonable. He criticizes approaches utilized by politicians and suggests that they are not interested in resolving this problem.

In conclusion, it is possible to state that the author has managed to ensure that the readers accept the surprise ending. It was not what I expected because I thought that Swift would continue to pressure politicians and would reveal that the idea to eat children was a joke in the end. However, he changes the tone masterfully and ends the piece with memorable lines. Overall, it is possible to interpret this essay in several ways, and it may be necessary to read it several times to identify clues hidden by the author.

Sayre, H. M. (2011). The humanities: Culture, continuity, and change (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Pearson Education.

Swift, J. (1729). A Modest Proposal for preventing the children of poor people in Ireland, from being a burden on their parents or country, and for making them beneficial to the publick . Web.

- Word Choice in "The Curse" by Arthur C. Clarke

- Loyalty in "Hard Times" by Charles Dickens

- Poverty in “A Modest Proposal” by Swift

- Jonathan Swift Satire Analysis

- Mockery of the Life in Ireland in “A Modest Proposal“ by Jonathan Swift

- Jane Austen’s Novel ‘Pride and Prejudice’

- Morality and Free Will in "Daisy Miller" by James

- "Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus" by Shelley

- "High Fidelity": Hornby's Novel and Frears's Film

- Surprising Effect in Swift's "A Modest Proposal"

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2020, August 24). Satire in "A Modest Proposal" by Jonathan Swift. https://ivypanda.com/essays/satire-in-a-modest-proposal-by-jonathan-swift/

"Satire in "A Modest Proposal" by Jonathan Swift." IvyPanda , 24 Aug. 2020, ivypanda.com/essays/satire-in-a-modest-proposal-by-jonathan-swift/.

IvyPanda . (2020) 'Satire in "A Modest Proposal" by Jonathan Swift'. 24 August.

IvyPanda . 2020. "Satire in "A Modest Proposal" by Jonathan Swift." August 24, 2020. https://ivypanda.com/essays/satire-in-a-modest-proposal-by-jonathan-swift/.

1. IvyPanda . "Satire in "A Modest Proposal" by Jonathan Swift." August 24, 2020. https://ivypanda.com/essays/satire-in-a-modest-proposal-by-jonathan-swift/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Satire in "A Modest Proposal" by Jonathan Swift." August 24, 2020. https://ivypanda.com/essays/satire-in-a-modest-proposal-by-jonathan-swift/.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Jonathan Swift (born November 30, 1667, Dublin, Ireland—died October 19, 1745, Dublin) was an Anglo-Irish author, who was the foremost prose satirist in the English language.Besides the celebrated novel Gulliver's Travels (1726), he wrote such shorter works as A Tale of a Tub (1704) and "A Modest Proposal" (1729).. Early life and education. Swift's father, Jonathan Swift the elder ...

Introduction. Jonathan Swift (November 30, 1667 - October 19, 1745) was an Anglo-Irish priest, essayist, political writer, and poet, considered the foremost satirist in the English language. Swift's fiercely ironic novels and essays, including world classics such as Gulliver's Travels and The Tale of the Tub, were immensely popular in his ...

Jonathan Swift was an Anglo-Irish essayist, satirist, poet, political pamphleteer, and cleric. He became a Dean of St. Patrick's Cathedral, Dublin. His common handle was "Dean Swift.". He first supported Whigs and then Tories in his political career. The most celebrated works of Jonathan swift include A Tale of Tub, Gulliver's Travels ...

Categories: Satire. Download. Essay, Pages 5 (1026 words) Views. 4024. Jonathan Swift, a prominent figure in English literature, has been hailed by many critics, including William Deans Howells and T.S. Eliot, as one of the greatest writers of English prose. T.S. Eliot, in particular, extolled Swift as "the greatest writer of English prose" and ...

Jonathan Swift (30 November 1667 - 19 October 1745) was an Anglo-Irish satirist, author, essayist, political pamphleteer (first for the Whigs, then for the Tories), poet, and Anglican cleric who became Dean of St Patrick's Cathedral, Dublin, hence his common sobriquet, "Dean Swift".. Swift is remembered for works such as A Tale of a Tub (1704), An Argument Against Abolishing Christianity ...

By common consent, Jonathan Swift is perhaps the greatest satirist who ever lived. His prose creation A Tale of a Tub is clearly one of the densest and richest satires ever composed. His terse ...

Jonathan Swift, (born Nov. 30, 1667, Dublin, Ire.—died Oct. 19, 1745, Dublin), Irish author, the foremost prose satirist in English.He was a student at Dublin's Trinity College during the anti-Catholic Revolution of 1688 in England. Irish Catholic reaction in Dublin led Swift, a Protestant, to seek security in England, where he spent various intervals before 1714.

Satire and formal philosophy have divergent intentions. The satirist soon learns to. give up on systems, and proceeds by negations and indirections to find his realities. Swift was never as serious about philosophy as he was about church and state. He was, in one sense, a rationalist, though an embattled one.

Jonathan Swift is the world's most misunderstood children's writer. Though his classic book Gulliver's Travels is often referred to as youth reading, it is in fact an audacious satire on the ...

Jonathan Swift Satire. While writing notable poems throughout his career, Swift is primarily known today for being a master of satire. Satire is a form of literature that ridicules immorality ...

The originality, concentrated power and "fierce indignation" of his satirical writing have earned Jonathan Swift (1667-1745) a reputation as the greatest prose satirist in English language. Gulliver's Travels is, of course, his world-renowned masterpiece in the genre; however, Swift wrote other, shorter works that also offer excellent evidence of his inspired lampoonery.

A Tritical Essay upon the Faculties of the Mind 17 ... The Cambridge Edition of the Works of Jonathan Swift is the Þrst fully ... literary and bibliographical contexts of his immense achievement as a prose satirist, poet and political writer. The editors of individual volumes include

Anglo-Irish poet, satirist, essayist, and political pamphleteer Jonathan Swift was born in Dublin, Ireland. He spent much of his early adult life in England before returning to Dublin to serve as Dean of St. Patrick's Cathedral, Dublin for the last 30 years of his life. It was this later stage when he would write most of his greatest works.

A Modest Proposal for Preventing the Children of Poor People from Being a Burthen to Their Parents or Country, and for Making Them Beneficial to the Publick, commonly referred to as A Modest Proposal, is a Juvenalian satirical essay written and published anonymously by Anglo-Irish writer and clergyman Jonathan Swift in 1729. The essay suggests that poor people in Ireland could ease their ...

A waji 3. Introduction. Jonathan Swift is identified as an excellent satirist in literature. Satire is a field in the. literature that exposes vices, abuses, and other negative behaviors in ...

Jonathan Swift (30 November 1667- 19 October 1745) was an Anglo-Irish satirist, essayist, political pamphleteer (first for the Whigs, then for the Tories), poet and cleric who became Dean of St Patrick's Cathedral, Dublin. Swift is remembered for works such as Gulliver's Travels, A Modest Proposal, A Journal to Stella, Drapier's Letters, The Battle of the Books, An Argument Against ...

Some Important Works of Jonathan Swift. Best Prose: Some of his best books include A Tale of a Tub, An Essay upon Ancient and Modern Learning, Battle of the Books, Gulliver's Travels, and A Modest Proposal. Other Works: Besides writing novels, he tried his hands in other areas too. Some of them include " Ode to the Athenian Society", "A ...

Introduction. It is imperative to note that "A Modest Proposal" is one of the most well-known satirical works by Jonathan Swift. The author provides a suggestion that would help to improve the economy of the country. The idea that poor children can be sold for food is quite shocking and could not be taken seriously.

SzefJt and Satire IRV1N EHRENPREIS' ONLY a few critics-Ricardo Quintana, Herbert Davis, F. R. Leavis, and some others-have tried to be specific about the satiric methods of Jonathan Swift. Most discussions go no further than an epithet like "complex" or "subtle" and the quoting of several samples. It is, however, not impossible to define a num-

He is the author of Edmund Burke and the Art of Rhetoric (2011). With James McLaverty he co-edited Jonathan Swift and the Eighteenth-Century Book (2013) and, with Alexis Tadié, Ancients and Moderns in Europe (2016). With Timothy Michael he is co-editor of volume 15 (Later Prose) of The Oxford Edition of the Works of Alexander Pope.

Swift was both a brilliant projector and a brilliant satirist. The. Drapier's Letters stirred the Irish to resistance, it was a success and until the 20th century. the satirist of the Modest Proposal was labelled mad (as we have tried to prove, the mock-project is not primarily a project but satire, a satiric device.).

He then used this talent to write and then publish "A Modest Proposal" in Dublin in 1729. During this time, Ireland was suffering under the strict economic limitations that England had placed upon them. In this essay, Swift illuminates the prejudices that the British held against the Irish through his use of satire.