tag manager container

- Employee Hub

- Directories

University Writing Program

- Mission Statement

- Course Description

- Assignments

- Research Tools

- Recommended Texts

- English 2000 Teachers

- Policies and Procedures

- Grade Appeals

- Policies and Procedures: Plagiarism

- Teaching Strategies

- In-Class Strategies

- Research Strategies

- Peer Response Strategies

- Important Links

- Resources | University Writing Program

For Teachers: 1001 Assignments

Below is a list of recommended assignments for English 1001. In some cases, descriptions are followed by links with sample assignments and other related resources.

Annotated Bibliography : An annotated bibliography helps students think through a research topic. In addition to bibliographical entry, each source is followed by a concise analysis of its main points. Annotations may also include a short response or a statement of potential uses for the source. These annotations are intended to be tools for students as they work on later essays; annotations should be designed to help them quickly remember how each source might be useful in their writing. How to Prepare an Annotated Bibliography (with sample) | Assignment Sheet

Causal Analysis : In a causal analysis, students are asked to investigate the known or possible causes of a situation, trend, or phenomenon through extensive research. At its most basic, a causal analysis seeks to answer the question "Why?" Since complex trends and phenomena are not easy to trace step-by-step, causal analysis typically relies on informed speculation of causes using reliable evidence and firsthand experience. Causal Analysis Assignment Sheet

Evaluation of a Source : During research, students should be able to read their sources for credibility and rhetorical appeals as well as for information. This type of reading can be expanded into an evaluation of a source, in which students must conduct a rhetorical analysis of their own materials. As part of this evaluation, students can examine the presentation of information, underlying assumptions, audience awareness, and possible uses of the source in future projects.

Event Analysis : In an event analysis, students are asked to explain the contexts and controversies surrounding a particular event. The event can be something in the past or something that students experience firsthand. An event analysis may examine the causes of the event, the activities during the event, the circumstances surrounding the event, or the consequences of the event. But the focal point is always the particular event and the parties involved. Sample Assignment Sheet

Habit Analysis : In a habit analysis, students are asked to examine the naturalized behaviors (or habits) that help to construct our personal identities and social norms. In one sense, a habit analysis is a rhetorical analysis focusing on ethos , the art of identifying oneself and earning trust. However, a habit analysis can also examine other kinds of behavior, such as personal writing habits or established social customs.

Issue Analysis : (*REQUIRED*) In an issue analysis, students are asked to explain the debate surrounding a contested issue. Because issues involve multiple perspectives, students must locate a wide range of sources in order to present each perspective fairly and thoughtfully. The ultimate goal of an issue analysis is to introduce the debate to an uninformed audience without favoring one argument. All sections of English 1001 must include an issue analysis in order to complete the end-of-semester assessment . Find assignment sheets, scoring matrices, and sample issue analysis essays in the English 1001 Teachers topic on the community moodle page.

Literacy Analysis : In a literacy analysis, students are asked to reflect on the experiences and events that have shaped them as both readers and writers. This assignment is useful because it introduces writing itself as a topic of inquiry and identity-formation. Furthermore, it allows students and teachers to share both frustrations and insights about writing as a "literate" activity through self-reflexive analyses of students' writing practices. Click on the following links for sample documents: Assignment Sheet || Sample Rubric 1 | 2 || Sample Literacy Analysis || Digital Archive of Literacy Narratives

Presentation: For the presentation, students are asked to present their analysis of an issue, text, or image to the entire class. Some teachers ask students to work collaboratively, use technology such as Power Points, or use other visual media. Group Visual Presentation Assignment | Individual Oral Presentation Assignment

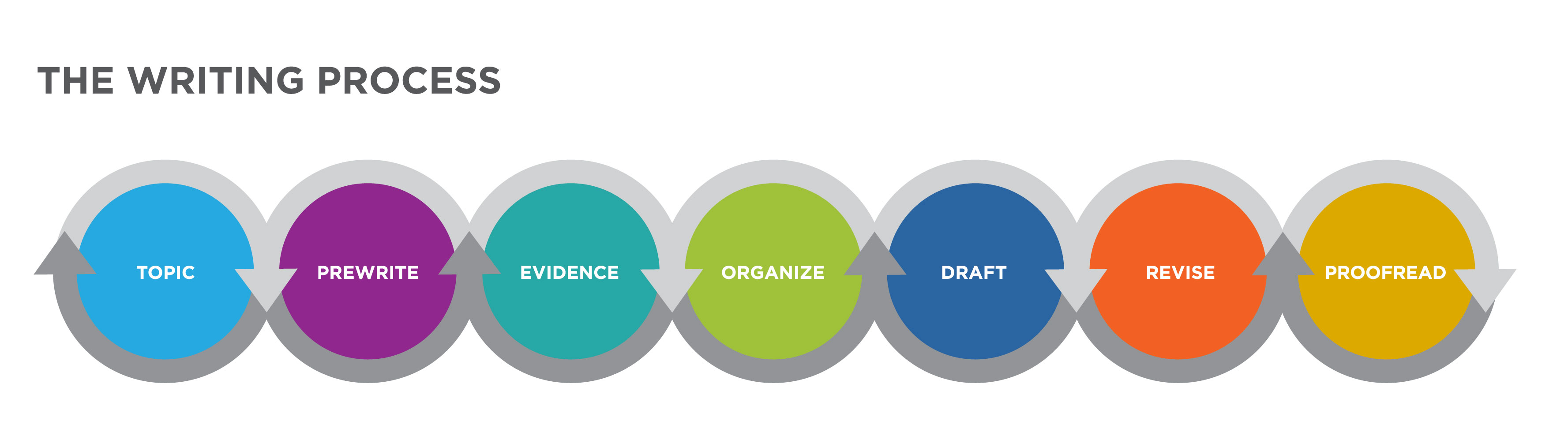

Process Analysis : In a process analysis, students are asked to take readers through a chronological sequence of steps. Informational process analyses describe how something occurs, while instructional process analyses describe how something is done (such that it can be duplicated). Processes analyzed should be neither too technical nor too simplistic, and students should be able to explain the importance of the process to readers.

Rhetorical Analysis : In a rhetorical analysis, students are asked to examine a spoken or written text for argumentative appeals, including logos (appeals to make logical connections), ethos (appeals to build credibility), and pathos (appeals to win sympathy or incite emotion). Other topics of analysis include kairos (or context), stated or implied purpose, intended audience, thesis and background information. Prewriting worksheet | Sample prewriting | Rhetorical Strategies | Ethos, Pathos and Logos: 1 | 2 || Assignment sheet || Sample essays: basic | 1 | 2 || Rubric

Synthesis: Most analytical writing requires some form of synthesis; it is an essential skill for the required issue analysis, as well as for any researched essay. Some teachers create assignments to isolate and target this skill, which ask students to pull together multiple sets of ideas in order to compare, contrast, evaluate and discover new insights. Synthesis essay and in-class practice | Literature review and synthesis

Textual Analysis : In a textual analysis, students are asked to examine a non-literary text (such as a scholarly article) and describe the way that it functions or serves a specific purpose. Analyzable texts may include scholarly sources, resumes, bibliographies, and so on. The criteria for analysis may vary depending on the text's purpose. For example, students can conduct textual analyses of each other's work based on grading criteria.

Visual Analysis : In a visual analysis, students are asked to examine an ad, website, or other form of visual media. Visual analyses can be conducted in a number of ways. For example, students might examine formal elements, such as color and perception. Visual analysis can also be combined with rhetorical analysis (explaining appeals to logic, credibility, emotion and context) and literary analysis (interpreting metaphors, representation, and authorship). In-class activity | Advertising Analysis Assignment

Search form

How to write the best college assignments.

By Lois Weldon

When it comes to writing assignments, it is difficult to find a conceptualized guide with clear and simple tips that are easy to follow. That’s exactly what this guide will provide: few simple tips on how to write great assignments, right when you need them. Some of these points will probably be familiar to you, but there is no harm in being reminded of the most important things before you start writing the assignments, which are usually determining on your credits.

The most important aspects: Outline and Introduction

Preparation is the key to success, especially when it comes to academic assignments. It is recommended to always write an outline before you start writing the actual assignment. The outline should include the main points of discussion, which will keep you focused throughout the work and will make your key points clearly defined. Outlining the assignment will save you a lot of time because it will organize your thoughts and make your literature searches much easier. The outline will also help you to create different sections and divide up the word count between them, which will make the assignment more organized.

The introduction is the next important part you should focus on. This is the part that defines the quality of your assignment in the eyes of the reader. The introduction must include a brief background on the main points of discussion, the purpose of developing such work and clear indications on how the assignment is being organized. Keep this part brief, within one or two paragraphs.

This is an example of including the above mentioned points into the introduction of an assignment that elaborates the topic of obesity reaching proportions:

Background : The twenty first century is characterized by many public health challenges, among which obesity takes a major part. The increasing prevalence of obesity is creating an alarming situation in both developed and developing regions of the world.

Structure and aim : This assignment will elaborate and discuss the specific pattern of obesity epidemic development, as well as its epidemiology. Debt, trade and globalization will also be analyzed as factors that led to escalation of the problem. Moreover, the assignment will discuss the governmental interventions that make efforts to address this issue.

Practical tips on assignment writing

Here are some practical tips that will keep your work focused and effective:

– Critical thinking – Academic writing has to be characterized by critical thinking, not only to provide the work with the needed level, but also because it takes part in the final mark.

– Continuity of ideas – When you get to the middle of assignment, things can get confusing. You have to make sure that the ideas are flowing continuously within and between paragraphs, so the reader will be enabled to follow the argument easily. Dividing the work in different paragraphs is very important for this purpose.

– Usage of ‘you’ and ‘I’ – According to the academic writing standards, the assignments should be written in an impersonal language, which means that the usage of ‘you’ and ‘I’ should be avoided. The only acceptable way of building your arguments is by using opinions and evidence from authoritative sources.

– Referencing – this part of the assignment is extremely important and it takes a big part in the final mark. Make sure to use either Vancouver or Harvard referencing systems, and use the same system in the bibliography and while citing work of other sources within the text.

– Usage of examples – A clear understanding on your assignment’s topic should be provided by comparing different sources and identifying their strengths and weaknesses in an objective manner. This is the part where you should show how the knowledge can be applied into practice.

– Numbering and bullets – Instead of using numbering and bullets, the academic writing style prefers the usage of paragraphs.

– Including figures and tables – The figures and tables are an effective way of conveying information to the reader in a clear manner, without disturbing the word count. Each figure and table should have clear headings and you should make sure to mention their sources in the bibliography.

– Word count – the word count of your assignment mustn’t be far above or far below the required word count. The outline will provide you with help in this aspect, so make sure to plan the work in order to keep it within the boundaries.

The importance of an effective conclusion

The conclusion of your assignment is your ultimate chance to provide powerful arguments that will impress the reader. The conclusion in academic writing is usually expressed through three main parts:

– Stating the context and aim of the assignment

– Summarizing the main points briefly

– Providing final comments with consideration of the future (discussing clear examples of things that can be done in order to improve the situation concerning your topic of discussion).

Normal 0 false false false EN-US X-NONE X-NONE /* Style Definitions */ table.MsoNormalTable {mso-style-name:"Table Normal"; mso-tstyle-rowband-size:0; mso-tstyle-colband-size:0; mso-style-noshow:yes; mso-style-priority:99; mso-style-parent:""; mso-padding-alt:0in 5.4pt 0in 5.4pt; mso-para-margin:0in; mso-para-margin-bottom:.0001pt; mso-pagination:widow-orphan; font-size:11.0pt; font-family:"Calibri","sans-serif"; mso-ascii-font-family:Calibri; mso-ascii-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-hansi-font-family:Calibri; mso-hansi-theme-font:minor-latin;}

Lois Weldon is writer at Uk.bestdissertation.com . Lives happily at London with her husband and lovely daughter. Adores writing tips for students. Passionate about Star Wars and yoga.

7 comments on “How To Write The Best College Assignments”

Extremely useful tip for students wanting to score well on their assignments. I concur with the writer that writing an outline before ACTUALLY starting to write assignments is extremely important. I have observed students who start off quite well but they tend to lose focus in between which causes them to lose marks. So an outline helps them to maintain the theme focused.

Hello Great information…. write assignments

Well elabrated

Thanks for the information. This site has amazing articles. Looking forward to continuing on this site.

This article is certainly going to help student . Well written.

Really good, thanks

Practical tips on assignment writing, the’re fantastic. Thank you!

Leave a comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Stanford Home

- Maps & Directions

- Search Stanford

- Emergency Info

- Terms of Use

- Non-Discrimination

- Accessibility

© Stanford University , Stanford , California 94305 .

Creative Writing Prompts To Boost Your Inspiration

Creative writing prompts are writing assignments used to test students’ writing knowledge and skills.

Inwardly, the key to being a good creative writer, is practice – having daily writing exercises. On possible external influences, you should not wait for inspiration to come to you. You have to chase it with a club. Let’s see how you can get inspiration for writing flowing.

Where To Get Ideas To Write About?

No matter how much you like to write, there will always be days when you will need to be inspired by one muse or another. In fact, it could open a debate about whether inspiration is not just something we want, but an integral part of the creative process.

Every creative writing author needs inspiration if they want to write well. Most of the time, our inspiration comes to us in the most strange ways and the most unforeseen places.

We have compiled for you some creative writing tips which include 20 sources to get inspired to write; some are obvious, others not so much.

- Books : Read the writers you admire, like to read, analyze what they write, and try to emulate what they do.

- Things you hear : All writers, deep down, are a bit of voyeurs. When you’re in a public place, always have your antennas on. Listen to other people’s conversations discreetly.

- Magazines : Magazines do not attract their readers for their literary quality, they supplement that lack with different focuses, voices, and rhythms, and that is where we can learn.

- Forums : When writing in forums, the important thing is to share information or make your ideas known. And it’s those ideas that can inspire us to have creative writing topics.

- Art : For a writer, there is no greater inspiration than the art itself. Although it is not the same as seeing it in person, you can find inspiration in the great works, you just have to search for them online. It does not have to be classic art. Anything works, anime, comics… it’s up to you.

- Music : At the same time, you can find a lot of inspiration in music. Music is life, you can write with background music, and the truth is, it is magical.

- Friends : Chatting with friends, in person, by phone, or by email can inspire you. Your friends will criticize your creative writing ideas, give another perspective, and give you their own ideas.

- Nature : Do you lack ideas? Lift your ass off the chair and go for a walk or run. Get away from the sidewalks and streets and look for places full of trees, grass, and vegetation. A park, a river, the beach, a pond, etc.

- History : Great personalities in history can inspire you to do great things. Examples are Julio César, Napoleón, Beethoven, etc.

- Travels : Maybe you go around the world, or just a weekend getaway, leave your area, visit other landscapes, people, food, or customs. Use those places to change the way you see things.

- Children : Children have a different way of seeing things, without taboos. They say what they think and do not care what you think of what they say.

- Exercise : Exercising is not only good for the body, by increasing the blood flow to the brain and being outdoors, your thoughts flow more freely.

- Newspapers : If you know what to look for, you will be surprised. Sometimes, reality trumps fiction.

- Dreams : Dreams are a source of inspiration. If you dream a lot (or even a few times), you can have a notebook where you write them down – if you are able to remember them.

- Journal writing : We recommend having a journal. It does not have to be pretty, as long as it has a leather cover and all that. You do not even have to write in it every day. Later, you can use many of those pieces.

- Blogs : There are millions of blogs, on any subject you can imagine (and on so many others that you cannot imagine). Be inspired, but do not copy. Talking about plagiarism, you may try to find out how to avoid plagiarism and produce unique content, even while getting inspiration from online sources.

- Poetry : How is it possible that poetry inspires prose? Nothing better than the rhythm and beauty of a good poem to inspire great emotions and ideas.

- Shakespeare : The eternal bard is always a source of inspiration for anyone. His stories are impossible to pigeonhole – love, drama, comedy, ghosts, witches, murders, and racism. Everything fits into complex work that is bequeathed to us.

- Google : Possibly the greatest source of information that exists. If you are dry of ideas, write anything and see what comes out.

- Free writing : Here’s a great exercise, either to find inspiration or to relieve yourself in times of stress. Take a sheet of paper, a pen and let yourself go. Do not think. Just write what goes through your head.

Using Creative Writing Prompts

Creative writing prompts can be likened to a matchbox. They create the triggers of the imaginative fire, making you go beyond your comfort zone towards a creative writing exercise.

Using a creative writing prompt, there is no limit you can achieve, from creating a short creative story to a long essay, all depends on your ability to brainstorm, research, and invent literary ideas.

Best Creative Writing Topics And Prompts In 2020 (By Type)

Creative writing is diverse, from journal writing to essay writing and many others. Let’s see some various creative prompts and topics to write about.

Fiction Writing Topics Ideas

- A rebellious character revolts against a higher authority.

- Avenging a loved one: an act of revenge within the same family.

- A disaster occurs or will occur as a result of a character’s actions.

- A situation where a hunted character must escape to save his life.

- A character avenges the murder of another character.

- A character kidnaps a person against his will.

- A character kills the husband of his lover.

- A character commits crimes under the influence of madness or drugs.

- A character has or perhaps has an incestuous relationship.

- A character kills a loved one without knowing it.

- A character gives his life for an ideal.

- A character sacrifices himself to save a loved one.

- The passion of a character turns out to be fatal.

- A loving character gets lost and commits a crime.

- The beloved is engaged in reprehensible activities.

- A situation when love between a pair is hindered by the family or society.

- A character loves someone who is his enemy.

- A character from an affluent background falls in love with a person of lower social status or vice versa.

- Breakdown in international relations between world superpowers results in a third world war, which sees half of the world population eliminated.

- A character seeks to seize power by all means.

20 Creative Nonfiction Writing Topics

- The real relationship between food, fitness, and weight

- Steroid users should be excluded from team sports activities.

- What are the negative effects of dieting?

- Hockey and other dangerous sports.

- The abuse of energy drinks

- The problem of work addiction

- The problem of sexually transmitted diseases in young people.

- Marketing of healthy foods and their impact on youth health

- Marketing and its role in shaping superficial paradigms in young people

- Debate on the legality or not of drugs

- Debate on euthanasia

- Being a vegetarian in a world of fast foods

- Abortion: Arguments for and against its legalization

- The legality of drugs does not solve the problem of addiction in young people.

- Why is junk food so addictive?

- Is it a good idea to drink bottled water?

- Do fad diets really work?

- Does eating gluten really make people healthier?

- What fast food restaurant serves the best food?

- Which is better, Starbucks or your local coffee shop?

Journal Writing Topics Ideas

- Write about the girl you turned down your proposal after a couple of dates

- Write about your first day in college

- Write about your scary nightmares

- Write about your nostalgic childhood memories

- Write about what your first wet dream felt like

- If you’ve ever lost a parent, write about how it feels

- Write how it feels like returning back to college after your summer vacay

- Write about your disturbing health conditions

- Pen a thank you journal to a friend who listened to your worries and proffered solutions

- Write about dissuading a close friend from alcoholism

- What and where will I be in 10 years time?

- A past time in your life which you would love to forget

- Write about your favorite authors or entertainers.

- Write about how your first heartbreak felt like

- Write about losing your childhood friend

- Set yourself a future goal

- Evaluate what your biggest accomplishments in life are

- Pen a real-life story of betrayal

- If you win a million dollar lottery, how would you spend it?

- Write about who your anger problems

20 Essay Writing Topics And Prompts

- The problem of drug use with students

- Children with autism and the challenge of education

- Most high-level jobs are done by men. Should the government encourage a certain percentage of these jobs to be reserved for women?

- Zoos are sometimes considered necessary but are poor alternatives compared to a natural environment. Discuss some of the arguments for and against keeping animals in zoos.

- The difficulty of achieving economic independence

- The government should impose limits on domestic garbage.

- Do men earn more money than women who have the same job position and education?

- Is it easier for a man to access a better-paid job?

- Euthanasia: where does the term come from? What does it mean to grant a person a dignified death? Cases of euthanasia in the world. In what countries is it legal and in what cases?

- What is the best way to prevent the use and abuse of drugs?

- Hemp legalization: advantages and disadvantages. What countries have legalized it, and what has been the result of drug addiction rates?

- The problem of poverty: economic systems that promote the creation of new jobs and social welfare.

- Legalization of gay marriage: where is it legal?

- Advantages of an inclusive society where the rights of all citizens are respected regardless of their creed, race, and/or sexual orientation.

- The right to privacy in the globalized era: how the internet and social networks have robbed us of privacy?

- Where does intimate life begin, and where does it end?

- What types of content is good to publish, and which ones should remain in the private universe?

- Control in the sale of weapons: why would it help to have more control over who, how, and when someone can have access to firearms?

- Immigration: how migrants make an active and productive part of society? Advantages of opening the doors to trained workers and families in need.

- Ways to fight bullying: how to explain to children and young people the serious consequences of bullying? How to make children and young people an active part of the solution.

Creative Writing Topics By Grade

There are different creative prompts for different education levels: elementary school, middle school, high school, and college. Below is a list of daily writing prompts, interesting topics for each grade as well as some questions related to the topic that can help generate a point of view.

20 Writing Topics For Elementary School Students

There is no age limit about the age one can start writing. Let’s see some writing prompt idea and topics which can shape the writing skills of elementary school kids.

- My best friend

- My favorite food

- My long-distant uncle

- The best gift Daddy gave me

- My favorite teacher

- My classmates

- My favorite TV show

- My favorite cartoon series

- How I’ll spend my next holiday

- My dream place I’ll love to visit

- My scary night dream

- My favorite book

- My favorite subject

- What I’ll like to become

- My visit to the zoo

- My favorite time of the week

20 Prompts And Topics For Middle School Students

Middle school is the preparatory level for high school. The basic literary skills and knowledge acquired here will shape the student’s future regarding literary writing. Here are 20 prompts and topics for students in middle school.

- The first day in my new school

- My favorite Disney TV show

- My favorite Disney character

- Why school uniforms shouldn’t be made compulsory for students

- My trip to the cross-country

- The problem of racism

- Should children do house chores

- When’s the best time to have my assignment done

- What is feminism

- Why sporting activities is compulsory for students

- The role of technology in studying

- The best day of my life

- The things I regret doing

- Which is the best department in high school?

- The problem of bullying among students

- Social inequality

- Are kids influenced by violence on TV?

- The best book I have read?

- My favorite Shakespeare book

- My role model

20 Creative Prompts And Topics For High School Students

Daily writing exercises are highly recommended for high school students – especially in the arts and related departments in high school.

As essays in high school will prepare you for more tasking literary pieces such as argumentative essays, here are some topics and prompts to help you in answering the famed question: what should I write about?

- How do fertilizers and chemicals affect the products we consume? Consequences in our health of the use of these substances. Why is it better to eat organic crops?

- The revolution of electronic books: Advantages and disadvantages of reading in tablets. Where are the paper books?

- The effect of globalization on the expansion of art: The new concepts of temporal arts.

- Influence of social networks on adolescents: How new generations are losing social skills due to their addiction to interactions through the screen.

- Internet abuse and its effects on the health of young people.

- Violence in video games: How are children in affected by the violence that video games present to them?

- Fast food and its effects on health: Everything in moderation is worth it?

- Do women have more responsibilities in the home?

- How do animal fats and saturated fats affect health?

- The problem of obesity in the new generations. How to educate children and young people in healthier eating habits?

- How is education one of the keys to generating more social equality?

- The death penalty: does it bring solutions to society to end the life of a convict?

- The benefits of vegetarian food: How a diet based on fruits, vegetables, legumes, grains, and seeds can help health.

- How to empower girls to become successful women The importance of education to create equal environments for boys and girls.

- The obsession with beauty and perfection: Too much care can generate more problems than benefits?

- How reading helps generate curious children and young people.

- Importance of homeschooling: why what we learn at home is equally important to what we learn at school? How to teach by example.

- The role of the State in higher education: How politicians and governments can be a factor in changing the quality of education.

- Reasons to prohibit the use of cell phones in the classroom: why should classrooms be a cell-free place?

- How to provide an educational environment free of publications, social networks, likes, and tweets?

20 Writing Prompts For College Students

Going to college is definitely a step-up in the life of every student, and these essay prompts will even get more talking and need extra effort and brainstorming. Check out 20 of some of the many writing ideas you can choose from.

- The consequences of climate change: Origins, studies, and causes. How are human beings affected by these phenomena? How to help with small changes in our habits?

- The use and abuse of creams and plastic surgeries.

- How is the workload balanced with domestic life?

- Importance of promoting green energy: The new wave of renewable energy. How do certain countries invest in green energy? The advantages of renewable energies.

- Why the world should switch to electric cars

- Excessive noise in cities: Is there a way to “clean up” the noise generated by cars, buses, and trucks in cities?

- Why AI is a ticking time bomb. The disadvantages of implementing AI in human society

- Tax havens: Places where tax benefits attract citizens from other parts of the world.

- The minimum wage: How is the new minimum wage in the United States helping the less favored? Why does an equitable minimum wage generate more committed employees?

- Artificial insemination: How couples who could not have children before now have a family. How artificial insemination helps couples of the same sex to form a family.

- Abortion: what countries allow it, and what are its restrictions? Why support it? Why be against? What are the advantages of decriminalizing it?

- The role of communications in social networks for modern education.

- Write about sportsmen. Do you think they are paid too much?

- Why teachers should be graded

- Homosexuality in the military service

- Why firearms should not be registered

- How the family structure has changed in recent years

- UFOs: Fantasies or realities

- Who is the best American president ever

- Why payment of admission fees should be scrapped in the university

Top 10 Creative Topics For Writing

Having talked about prompts and topics for different grades, here’s a culmination of some top creative topics. Check them out!

- Why Trump is wrong about climate change

- Why cannabis should not be legalized

- Why euthanasia should be considered

- Life in the countryside is better than life in the city

- What’s the right age for youth to leave their parents

- Is global cooling still possible on earth?

- Why there are less natural disasters in Africa

- The brain drain and brain gain phenomena

- Why superpowers US and China should strengthen their ties

- Is Mars habitable?

How To Organize Daily Writing Exercises?

- Keep a journal

- Dedicate a specific time

- Start a blog

- Eliminate distraction

- Set up a goal

- Dedicate a specific space for writing

Much has been said about how to come up with creative writing topics, prompts, and ideas for every educational level. Consistency and practice are the main keys toward perfection in your writing niche. There are audiences for everyone, and the literary world is vast enough for you to explore.

Don't waste time

Get a professional assistance from certified experts right now

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Common Writing Assignments

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

These OWL resources will help you understand and complete specific types of writing assignments, such as annotated bibliographies, book reports, and research papers. This section also includes resources on writing academic proposals for conference presentations, journal articles, and books.

Understanding Writing Assignments

This resource describes some steps you can take to better understand the requirements of your writing assignments. This resource works for either in-class, teacher-led discussion or for personal use.

Argument Papers

This resource outlines the generally accepted structure for introductions, body paragraphs, and conclusions in an academic argument paper. Keep in mind that this resource contains guidelines and not strict rules about organization. Your structure needs to be flexible enough to meet the requirements of your purpose and audience.

Research Papers

This handout provides detailed information about how to write research papers including discussing research papers as a genre, choosing topics, and finding sources.

Exploratory Papers

This resource will help you with exploratory/inquiry essay assignments.

Annotated Bibliographies

This handout provides information about annotated bibliographies in MLA, APA, and CMS.

Book Report

This resource discusses book reports and how to write them.

Definitions

This handout provides suggestions and examples for writing definitions.

Essays for Exams

While most OWL resources recommend a longer writing process (start early, revise often, conduct thorough research, etc.), sometimes you just have to write quickly in test situations. However, these exam essays can be no less important pieces of writing than research papers because they can influence final grades for courses, and/or they can mean the difference between getting into an academic program (GED, SAT, GRE). To that end, this resource will help you prepare and write essays for exams.

Book Review

This resource discusses book reviews and how to write them.

Academic Proposals

This resource will help undergraduate, graduate, and professional scholars write proposals for academic conferences, articles, and books.

In this section

Subsections.

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

4.3: Writing Assignments

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 58278

- Lumen Learning

Learning Objectives

- Describe common types and expectations of writing tasks given in a college class

What to Do With Writing Assignments

Writing assignments can be as varied as the instructors who assign them. Some assignments are explicit about what exactly you’ll need to do, in what order, and how it will be graded. Others are more open-ended, leaving you to determine the best path toward completing the project. Most fall somewhere in the middle, containing details about some aspects but leaving other assumptions unstated. It’s important to remember that your first resource for getting clarification about an assignment is your instructor—she or he will be very willing to talk out ideas with you, to be sure you’re prepared at each step to do well with the writing.

Writing in college is usually a response to class materials—an assigned reading, a discussion in class, an experiment in a lab. Generally speaking, these writing tasks can be divided into three broad categories: summary assignments, defined-topic assignments, and undefined-topic assignments.

Link to Learning

This Assignment Calculator can help you plan ahead for your writing assignment. Just plug in the date you plan to get started and the date it is due, and it will help break it down into manageable chunks.

Summary Assignments

Being asked to summarize a source is a common task in many types of writing. It can also seem like a straightforward task: simply restate, in shorter form, what the source says. A lot of advanced skills are hidden in this seemingly simple assignment, however.

An effective summary does the following:

- reflects your accurate understanding of a source’s thesis or purpose

- differentiates between major and minor ideas in a source

- demonstrates your ability to identify key phrases to quote

- demonstrates your ability to effectively paraphrase most of the source’s ideas

- captures the tone, style, and distinguishing features of a source

- does not reflect your personal opinion about the source

That last point is often the most challenging: we are opinionated creatures, by nature, and it can be very difficult to keep our opinions from creeping into a summary, which is meant to be completely neutral.

In college-level writing, assignments that are only summary are rare. That said, many types of writing tasks contain at least some element of summary, from a biology report that explains what happened during a chemical process, to an analysis essay that requires you to explain what several prominent positions about gun control are, as a component of comparing them against one another.

Writing Effective Summaries

Start with a clear identification of the work.

This automatically lets your readers know your intentions and that you’re covering the work of another author.

- In the featured article “Five Kinds of Learning,” the author, Holland Oates, justifies his opinion on the hot topic of learning styles — and adds a few himself.

Summarize the Piece as a Whole

Omit nothing important and strive for overall coherence through appropriate transitions. Write using “summarizing language.” Your reader needs to be reminded that this is not your own work. Use phrases like the article claims, the author suggests, etc.

- Present the material in a neutral fashion. Your opinions, ideas, and interpretations should be left in your brain — don’t put them into your summary. Be conscious of choosing your words. Only include what was in the original work.

- Be concise. This is a summary — it should be much shorter than the original piece. If you’re working on an article, give yourself a target length of 1/4 the original article.

Conclude with a Final Statement

This is not a statement of your own point of view, however; it should reflect the significance of the book or article from the author’s standpoint.

- Without rewriting the article, summarize what the author wanted to get across. Be careful not to evaluate in the conclusion or insert any of your own assumptions or opinions.

Understanding the Assignment and Getting Started

Often, the handout or other written text explaining the assignment—what professors call the assignment prompt —will explain the purpose of the assignment and the required parameters (length, number and type of sources, referencing style, etc.).

Also, don’t forget to check the rubric, if there is one, to understand how your writing will be assessed. After analyzing the prompt and the rubric, you should have a better sense of what kind of writing you are expected to produce.

Sometimes, though—especially when you are new to a field—you will encounter the baffling situation in which you comprehend every single sentence in the prompt but still have absolutely no idea how to approach the assignment! In a situation like that, consider the following tips:

- Focus on the verbs . Look for verbs like compare, explain, justify, reflect , or the all-purpose analyze . You’re not just producing a paper as an artifact; you’re conveying, in written communication, some intellectual work you have done. So the question is, what kind of thinking are you supposed to do to deepen your learning?

- Put the assignment in context . Many professors think in terms of assignment sequences. For example, a social science professor may ask you to write about a controversial issue three times: first, arguing for one side of the debate; second, arguing for another; and finally, from a more comprehensive and nuanced perspective, incorporating text produced in the first two assignments. A sequence like that is designed to help you think through a complex issue. If the assignment isn’t part of a sequence, think about where it falls in the span of the course (early, midterm, or toward the end), and how it relates to readings and other assignments. For example, if you see that a paper comes at the end of a three-week unit on the role of the Internet in organizational behavior, then your professor likely wants you to synthesize that material.

- Try a free-write . A free-write is when you just write, without stopping, for a set period of time. That doesn’t sound very “free”; it actually sounds kind of coerced, right? The “free” part is what you write—it can be whatever comes to mind. Professional writers use free-writing to get started on a challenging (or distasteful) writing task or to overcome writer’s block or a powerful urge to procrastinate. The idea is that if you just make yourself write, you can’t help but produce some kind of useful nugget. Thus, even if the first eight sentences of your free write are all variations on “I don’t understand this” or “I’d really rather be doing something else,” eventually you’ll write something like “I guess the main point of this is…,” and—booyah!—you’re off and running.

- Ask for clarification . Even the most carefully crafted assignments may need some verbal clarification, especially if you’re new to a course or field. Professors generally love questions, so don’t be afraid to ask. Try to convey to your instructor that you want to learn and you’re ready to work, and not just looking for advice on how to get an A.

Defined-Topic Assignments

Many writing tasks will ask you to address a particular topic or a narrow set of topic options. Defined-topic writing assignments are used primarily to identify your familiarity with the subject matter. (Discuss the use of dialect in Their Eyes Were Watching God , for example.)

Remember, even when you’re asked to “show how” or “illustrate,” you’re still being asked to make an argument. You must shape and focus your discussion or analysis so that it supports a claim that you discovered and formulated and that all of your discussion and explanation develops and supports.

Undefined-Topic Assignments

Another writing assignment you’ll potentially encounter is one in which the topic may be only broadly identified (“water conservation” in an ecology course, for instance, or “the Dust Bowl” in a U.S. History course), or even completely open (“compose an argumentative research essay on a subject of your choice”).

Where defined-topic essays demonstrate your knowledge of the content , undefined-topic assignments are used to demonstrate your skills— your ability to perform academic research, to synthesize ideas, and to apply the various stages of the writing process.

The first hurdle with this type of task is to find a focus that interests you. Don’t just pick something you feel will be “easy to write about” or that you think you already know a lot about —those almost always turn out to be false assumptions. Instead, you’ll get the most value out of, and find it easier to work on, a topic that intrigues you personally or a topic about which you have a genuine curiosity.

The same getting-started ideas described for defined-topic assignments will help with these kinds of projects, too. You can also try talking with your instructor or a writing tutor (at your college’s writing center) to help brainstorm ideas and make sure you’re on track.

Getting Started in the Writing Process

Writing is not a linear process, so writing your essay, researching, rewriting, and adjusting are all part of the process. Below are some tips to keep in mind as you approach and manage your assignment.

Write down topic ideas. If you have been assigned a particular topic or focus, it still might be possible to narrow it down or personalize it to your own interests.

If you have been given an open-ended essay assignment, the topic should be something that allows you to enjoy working with the writing process. Select a topic that you’ll want to think about, read about, and write about for several weeks, without getting bored.

If you’re writing about a subject you’re not an expert on and want to make sure you are presenting the topic or information realistically, look up the information or seek out an expert to ask questions.

- Note: Be cautious about information you retrieve online, especially if you are writing a research paper or an article that relies on factual information. A quick Google search may turn up unreliable, misleading sources. Be sure you consider the credibility of the sources you consult (we’ll talk more about that later in the course). And keep in mind that published books and works found in scholarly journals have to undergo a thorough vetting process before they reach publication and are therefore safer to use as sources.

- Check out a library. Yes, believe it or not, there is still information to be found in a library that hasn’t made its way to the Web. For an even greater breadth of resources, try a college or university library. Even better, research librarians can often be consulted in person, by phone, or even by email. And they love helping students. Don’t be afraid to reach out with questions!

Write a Rough Draft

It doesn’t matter how many spelling errors or weak adjectives you have in it. Your draft can be very rough! Jot down those random uncategorized thoughts. Write down anything you think of that you want included in your writing and worry about organizing and polishing everything later.

If You’re Having Trouble, Try F reewriting

Set a timer and write continuously until that time is up. Don’t worry about what you write, just keeping moving your pencil on the page or typing something (anything!) into the computer.

Contributors and Attributions

- Outcome: Writing in College. Provided by : Lumen Learning. License : CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

- Writing in College: From Competence to Excellence. Authored by : Amy Guptill. Provided by : SUNY Open Textbooks. Located at : textbooks.opensuny.org/writing-in-college-from-competence-to-excellence/. License : CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

- Image of man writing. Authored by : Matt Zhang. Located at : https://flic.kr/p/pAg6t9 . License : CC BY-NC-ND: Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives

- Writing Strategies. Provided by : Lumen Learning. Located at : courses.lumenlearning.com/lumencollegesuccess/chapter/writing-strategies/. License : CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

- Image of woman reading. Authored by : Aaron Osborne. Located at : https://flic.kr/p/dPLmVV . License : CC BY: Attribution

- Image of sketches of magnifying glass. Authored by : Matt Cornock. Located at : https://flic.kr/p/eBSLmg . License : CC BY-NC: Attribution-NonCommercial

- How to Write a Summary. Authored by : WikiHow. Located at : http://www.wikihow.com/Write-a-Summary . License : CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

- How to Write. Provided by : WikiHow. License : CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

- Image of typing. Authored by : Kiran Foster. Located at : https://flic.kr/p/9M2WW4 . License : CC BY: Attribution

Understanding Assignments

What this handout is about.

The first step in any successful college writing venture is reading the assignment. While this sounds like a simple task, it can be a tough one. This handout will help you unravel your assignment and begin to craft an effective response. Much of the following advice will involve translating typical assignment terms and practices into meaningful clues to the type of writing your instructor expects. See our short video for more tips.

Basic beginnings

Regardless of the assignment, department, or instructor, adopting these two habits will serve you well :

- Read the assignment carefully as soon as you receive it. Do not put this task off—reading the assignment at the beginning will save you time, stress, and problems later. An assignment can look pretty straightforward at first, particularly if the instructor has provided lots of information. That does not mean it will not take time and effort to complete; you may even have to learn a new skill to complete the assignment.

- Ask the instructor about anything you do not understand. Do not hesitate to approach your instructor. Instructors would prefer to set you straight before you hand the paper in. That’s also when you will find their feedback most useful.

Assignment formats

Many assignments follow a basic format. Assignments often begin with an overview of the topic, include a central verb or verbs that describe the task, and offer some additional suggestions, questions, or prompts to get you started.

An Overview of Some Kind

The instructor might set the stage with some general discussion of the subject of the assignment, introduce the topic, or remind you of something pertinent that you have discussed in class. For example:

“Throughout history, gerbils have played a key role in politics,” or “In the last few weeks of class, we have focused on the evening wear of the housefly …”

The Task of the Assignment

Pay attention; this part tells you what to do when you write the paper. Look for the key verb or verbs in the sentence. Words like analyze, summarize, or compare direct you to think about your topic in a certain way. Also pay attention to words such as how, what, when, where, and why; these words guide your attention toward specific information. (See the section in this handout titled “Key Terms” for more information.)

“Analyze the effect that gerbils had on the Russian Revolution”, or “Suggest an interpretation of housefly undergarments that differs from Darwin’s.”

Additional Material to Think about

Here you will find some questions to use as springboards as you begin to think about the topic. Instructors usually include these questions as suggestions rather than requirements. Do not feel compelled to answer every question unless the instructor asks you to do so. Pay attention to the order of the questions. Sometimes they suggest the thinking process your instructor imagines you will need to follow to begin thinking about the topic.

“You may wish to consider the differing views held by Communist gerbils vs. Monarchist gerbils, or Can there be such a thing as ‘the housefly garment industry’ or is it just a home-based craft?”

These are the instructor’s comments about writing expectations:

“Be concise”, “Write effectively”, or “Argue furiously.”

Technical Details

These instructions usually indicate format rules or guidelines.

“Your paper must be typed in Palatino font on gray paper and must not exceed 600 pages. It is due on the anniversary of Mao Tse-tung’s death.”

The assignment’s parts may not appear in exactly this order, and each part may be very long or really short. Nonetheless, being aware of this standard pattern can help you understand what your instructor wants you to do.

Interpreting the assignment

Ask yourself a few basic questions as you read and jot down the answers on the assignment sheet:

Why did your instructor ask you to do this particular task?

Who is your audience.

- What kind of evidence do you need to support your ideas?

What kind of writing style is acceptable?

- What are the absolute rules of the paper?

Try to look at the question from the point of view of the instructor. Recognize that your instructor has a reason for giving you this assignment and for giving it to you at a particular point in the semester. In every assignment, the instructor has a challenge for you. This challenge could be anything from demonstrating an ability to think clearly to demonstrating an ability to use the library. See the assignment not as a vague suggestion of what to do but as an opportunity to show that you can handle the course material as directed. Paper assignments give you more than a topic to discuss—they ask you to do something with the topic. Keep reminding yourself of that. Be careful to avoid the other extreme as well: do not read more into the assignment than what is there.

Of course, your instructor has given you an assignment so that he or she will be able to assess your understanding of the course material and give you an appropriate grade. But there is more to it than that. Your instructor has tried to design a learning experience of some kind. Your instructor wants you to think about something in a particular way for a particular reason. If you read the course description at the beginning of your syllabus, review the assigned readings, and consider the assignment itself, you may begin to see the plan, purpose, or approach to the subject matter that your instructor has created for you. If you still aren’t sure of the assignment’s goals, try asking the instructor. For help with this, see our handout on getting feedback .

Given your instructor’s efforts, it helps to answer the question: What is my purpose in completing this assignment? Is it to gather research from a variety of outside sources and present a coherent picture? Is it to take material I have been learning in class and apply it to a new situation? Is it to prove a point one way or another? Key words from the assignment can help you figure this out. Look for key terms in the form of active verbs that tell you what to do.

Key Terms: Finding Those Active Verbs

Here are some common key words and definitions to help you think about assignment terms:

Information words Ask you to demonstrate what you know about the subject, such as who, what, when, where, how, and why.

- define —give the subject’s meaning (according to someone or something). Sometimes you have to give more than one view on the subject’s meaning

- describe —provide details about the subject by answering question words (such as who, what, when, where, how, and why); you might also give details related to the five senses (what you see, hear, feel, taste, and smell)

- explain —give reasons why or examples of how something happened

- illustrate —give descriptive examples of the subject and show how each is connected with the subject

- summarize —briefly list the important ideas you learned about the subject

- trace —outline how something has changed or developed from an earlier time to its current form

- research —gather material from outside sources about the subject, often with the implication or requirement that you will analyze what you have found

Relation words Ask you to demonstrate how things are connected.

- compare —show how two or more things are similar (and, sometimes, different)

- contrast —show how two or more things are dissimilar

- apply—use details that you’ve been given to demonstrate how an idea, theory, or concept works in a particular situation

- cause —show how one event or series of events made something else happen

- relate —show or describe the connections between things

Interpretation words Ask you to defend ideas of your own about the subject. Do not see these words as requesting opinion alone (unless the assignment specifically says so), but as requiring opinion that is supported by concrete evidence. Remember examples, principles, definitions, or concepts from class or research and use them in your interpretation.

- assess —summarize your opinion of the subject and measure it against something

- prove, justify —give reasons or examples to demonstrate how or why something is the truth

- evaluate, respond —state your opinion of the subject as good, bad, or some combination of the two, with examples and reasons

- support —give reasons or evidence for something you believe (be sure to state clearly what it is that you believe)

- synthesize —put two or more things together that have not been put together in class or in your readings before; do not just summarize one and then the other and say that they are similar or different—you must provide a reason for putting them together that runs all the way through the paper

- analyze —determine how individual parts create or relate to the whole, figure out how something works, what it might mean, or why it is important

- argue —take a side and defend it with evidence against the other side

More Clues to Your Purpose As you read the assignment, think about what the teacher does in class:

- What kinds of textbooks or coursepack did your instructor choose for the course—ones that provide background information, explain theories or perspectives, or argue a point of view?

- In lecture, does your instructor ask your opinion, try to prove her point of view, or use keywords that show up again in the assignment?

- What kinds of assignments are typical in this discipline? Social science classes often expect more research. Humanities classes thrive on interpretation and analysis.

- How do the assignments, readings, and lectures work together in the course? Instructors spend time designing courses, sometimes even arguing with their peers about the most effective course materials. Figuring out the overall design to the course will help you understand what each assignment is meant to achieve.

Now, what about your reader? Most undergraduates think of their audience as the instructor. True, your instructor is a good person to keep in mind as you write. But for the purposes of a good paper, think of your audience as someone like your roommate: smart enough to understand a clear, logical argument, but not someone who already knows exactly what is going on in your particular paper. Remember, even if the instructor knows everything there is to know about your paper topic, he or she still has to read your paper and assess your understanding. In other words, teach the material to your reader.

Aiming a paper at your audience happens in two ways: you make decisions about the tone and the level of information you want to convey.

- Tone means the “voice” of your paper. Should you be chatty, formal, or objective? Usually you will find some happy medium—you do not want to alienate your reader by sounding condescending or superior, but you do not want to, um, like, totally wig on the man, you know? Eschew ostentatious erudition: some students think the way to sound academic is to use big words. Be careful—you can sound ridiculous, especially if you use the wrong big words.

- The level of information you use depends on who you think your audience is. If you imagine your audience as your instructor and she already knows everything you have to say, you may find yourself leaving out key information that can cause your argument to be unconvincing and illogical. But you do not have to explain every single word or issue. If you are telling your roommate what happened on your favorite science fiction TV show last night, you do not say, “First a dark-haired white man of average height, wearing a suit and carrying a flashlight, walked into the room. Then a purple alien with fifteen arms and at least three eyes turned around. Then the man smiled slightly. In the background, you could hear a clock ticking. The room was fairly dark and had at least two windows that I saw.” You also do not say, “This guy found some aliens. The end.” Find some balance of useful details that support your main point.

You’ll find a much more detailed discussion of these concepts in our handout on audience .

The Grim Truth

With a few exceptions (including some lab and ethnography reports), you are probably being asked to make an argument. You must convince your audience. It is easy to forget this aim when you are researching and writing; as you become involved in your subject matter, you may become enmeshed in the details and focus on learning or simply telling the information you have found. You need to do more than just repeat what you have read. Your writing should have a point, and you should be able to say it in a sentence. Sometimes instructors call this sentence a “thesis” or a “claim.”

So, if your instructor tells you to write about some aspect of oral hygiene, you do not want to just list: “First, you brush your teeth with a soft brush and some peanut butter. Then, you floss with unwaxed, bologna-flavored string. Finally, gargle with bourbon.” Instead, you could say, “Of all the oral cleaning methods, sandblasting removes the most plaque. Therefore it should be recommended by the American Dental Association.” Or, “From an aesthetic perspective, moldy teeth can be quite charming. However, their joys are short-lived.”

Convincing the reader of your argument is the goal of academic writing. It doesn’t have to say “argument” anywhere in the assignment for you to need one. Look at the assignment and think about what kind of argument you could make about it instead of just seeing it as a checklist of information you have to present. For help with understanding the role of argument in academic writing, see our handout on argument .

What kind of evidence do you need?

There are many kinds of evidence, and what type of evidence will work for your assignment can depend on several factors–the discipline, the parameters of the assignment, and your instructor’s preference. Should you use statistics? Historical examples? Do you need to conduct your own experiment? Can you rely on personal experience? See our handout on evidence for suggestions on how to use evidence appropriately.

Make sure you are clear about this part of the assignment, because your use of evidence will be crucial in writing a successful paper. You are not just learning how to argue; you are learning how to argue with specific types of materials and ideas. Ask your instructor what counts as acceptable evidence. You can also ask a librarian for help. No matter what kind of evidence you use, be sure to cite it correctly—see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial .

You cannot always tell from the assignment just what sort of writing style your instructor expects. The instructor may be really laid back in class but still expect you to sound formal in writing. Or the instructor may be fairly formal in class and ask you to write a reflection paper where you need to use “I” and speak from your own experience.

Try to avoid false associations of a particular field with a style (“art historians like wacky creativity,” or “political scientists are boring and just give facts”) and look instead to the types of readings you have been given in class. No one expects you to write like Plato—just use the readings as a guide for what is standard or preferable to your instructor. When in doubt, ask your instructor about the level of formality she or he expects.

No matter what field you are writing for or what facts you are including, if you do not write so that your reader can understand your main idea, you have wasted your time. So make clarity your main goal. For specific help with style, see our handout on style .

Technical details about the assignment

The technical information you are given in an assignment always seems like the easy part. This section can actually give you lots of little hints about approaching the task. Find out if elements such as page length and citation format (see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial ) are negotiable. Some professors do not have strong preferences as long as you are consistent and fully answer the assignment. Some professors are very specific and will deduct big points for deviations.

Usually, the page length tells you something important: The instructor thinks the size of the paper is appropriate to the assignment’s parameters. In plain English, your instructor is telling you how many pages it should take for you to answer the question as fully as you are expected to. So if an assignment is two pages long, you cannot pad your paper with examples or reword your main idea several times. Hit your one point early, defend it with the clearest example, and finish quickly. If an assignment is ten pages long, you can be more complex in your main points and examples—and if you can only produce five pages for that assignment, you need to see someone for help—as soon as possible.

Tricks that don’t work

Your instructors are not fooled when you:

- spend more time on the cover page than the essay —graphics, cool binders, and cute titles are no replacement for a well-written paper.

- use huge fonts, wide margins, or extra spacing to pad the page length —these tricks are immediately obvious to the eye. Most instructors use the same word processor you do. They know what’s possible. Such tactics are especially damning when the instructor has a stack of 60 papers to grade and yours is the only one that low-flying airplane pilots could read.

- use a paper from another class that covered “sort of similar” material . Again, the instructor has a particular task for you to fulfill in the assignment that usually relates to course material and lectures. Your other paper may not cover this material, and turning in the same paper for more than one course may constitute an Honor Code violation . Ask the instructor—it can’t hurt.

- get all wacky and “creative” before you answer the question . Showing that you are able to think beyond the boundaries of a simple assignment can be good, but you must do what the assignment calls for first. Again, check with your instructor. A humorous tone can be refreshing for someone grading a stack of papers, but it will not get you a good grade if you have not fulfilled the task.

Critical reading of assignments leads to skills in other types of reading and writing. If you get good at figuring out what the real goals of assignments are, you are going to be better at understanding the goals of all of your classes and fields of study.

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout and attribute the source: The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Make a Gift

Eberly Center

Teaching excellence & educational innovation, creating assignments.

Here are some general suggestions and questions to consider when creating assignments. There are also many other resources in print and on the web that provide examples of interesting, discipline-specific assignment ideas.

Consider your learning objectives.

What do you want students to learn in your course? What could they do that would show you that they have learned it? To determine assignments that truly serve your course objectives, it is useful to write out your objectives in this form: I want my students to be able to ____. Use active, measurable verbs as you complete that sentence (e.g., compare theories, discuss ramifications, recommend strategies), and your learning objectives will point you towards suitable assignments.

Design assignments that are interesting and challenging.

This is the fun side of assignment design. Consider how to focus students’ thinking in ways that are creative, challenging, and motivating. Think beyond the conventional assignment type! For example, one American historian requires students to write diary entries for a hypothetical Nebraska farmwoman in the 1890s. By specifying that students’ diary entries must demonstrate the breadth of their historical knowledge (e.g., gender, economics, technology, diet, family structure), the instructor gets students to exercise their imaginations while also accomplishing the learning objectives of the course (Walvoord & Anderson, 1989, p. 25).

Double-check alignment.

After creating your assignments, go back to your learning objectives and make sure there is still a good match between what you want students to learn and what you are asking them to do. If you find a mismatch, you will need to adjust either the assignments or the learning objectives. For instance, if your goal is for students to be able to analyze and evaluate texts, but your assignments only ask them to summarize texts, you would need to add an analytical and evaluative dimension to some assignments or rethink your learning objectives.

Name assignments accurately.

Students can be misled by assignments that are named inappropriately. For example, if you want students to analyze a product’s strengths and weaknesses but you call the assignment a “product description,” students may focus all their energies on the descriptive, not the critical, elements of the task. Thus, it is important to ensure that the titles of your assignments communicate their intention accurately to students.

Consider sequencing.

Think about how to order your assignments so that they build skills in a logical sequence. Ideally, assignments that require the most synthesis of skills and knowledge should come later in the semester, preceded by smaller assignments that build these skills incrementally. For example, if an instructor’s final assignment is a research project that requires students to evaluate a technological solution to an environmental problem, earlier assignments should reinforce component skills, including the ability to identify and discuss key environmental issues, apply evaluative criteria, and find appropriate research sources.

Think about scheduling.

Consider your intended assignments in relation to the academic calendar and decide how they can be reasonably spaced throughout the semester, taking into account holidays and key campus events. Consider how long it will take students to complete all parts of the assignment (e.g., planning, library research, reading, coordinating groups, writing, integrating the contributions of team members, developing a presentation), and be sure to allow sufficient time between assignments.

Check feasibility.

Is the workload you have in mind reasonable for your students? Is the grading burden manageable for you? Sometimes there are ways to reduce workload (whether for you or for students) without compromising learning objectives. For example, if a primary objective in assigning a project is for students to identify an interesting engineering problem and do some preliminary research on it, it might be reasonable to require students to submit a project proposal and annotated bibliography rather than a fully developed report. If your learning objectives are clear, you will see where corners can be cut without sacrificing educational quality.

Articulate the task description clearly.

If an assignment is vague, students may interpret it any number of ways – and not necessarily how you intended. Thus, it is critical to clearly and unambiguously identify the task students are to do (e.g., design a website to help high school students locate environmental resources, create an annotated bibliography of readings on apartheid). It can be helpful to differentiate the central task (what students are supposed to produce) from other advice and information you provide in your assignment description.

Establish clear performance criteria.

Different instructors apply different criteria when grading student work, so it’s important that you clearly articulate to students what your criteria are. To do so, think about the best student work you have seen on similar tasks and try to identify the specific characteristics that made it excellent, such as clarity of thought, originality, logical organization, or use of a wide range of sources. Then identify the characteristics of the worst student work you have seen, such as shaky evidence, weak organizational structure, or lack of focus. Identifying these characteristics can help you consciously articulate the criteria you already apply. It is important to communicate these criteria to students, whether in your assignment description or as a separate rubric or scoring guide . Clearly articulated performance criteria can prevent unnecessary confusion about your expectations while also setting a high standard for students to meet.

Specify the intended audience.

Students make assumptions about the audience they are addressing in papers and presentations, which influences how they pitch their message. For example, students may assume that, since the instructor is their primary audience, they do not need to define discipline-specific terms or concepts. These assumptions may not match the instructor’s expectations. Thus, it is important on assignments to specify the intended audience http://wac.colostate.edu/intro/pop10e.cfm (e.g., undergraduates with no biology background, a potential funder who does not know engineering).

Specify the purpose of the assignment.

If students are unclear about the goals or purpose of the assignment, they may make unnecessary mistakes. For example, if students believe an assignment is focused on summarizing research as opposed to evaluating it, they may seriously miscalculate the task and put their energies in the wrong place. The same is true they think the goal of an economics problem set is to find the correct answer, rather than demonstrate a clear chain of economic reasoning. Consequently, it is important to make your objectives for the assignment clear to students.

Specify the parameters.

If you have specific parameters in mind for the assignment (e.g., length, size, formatting, citation conventions) you should be sure to specify them in your assignment description. Otherwise, students may misapply conventions and formats they learned in other courses that are not appropriate for yours.

A Checklist for Designing Assignments

Here is a set of questions you can ask yourself when creating an assignment.

- Provided a written description of the assignment (in the syllabus or in a separate document)?

- Specified the purpose of the assignment?

- Indicated the intended audience?

- Articulated the instructions in precise and unambiguous language?

- Provided information about the appropriate format and presentation (e.g., page length, typed, cover sheet, bibliography)?

- Indicated special instructions, such as a particular citation style or headings?

- Specified the due date and the consequences for missing it?

- Articulated performance criteria clearly?

- Indicated the assignment’s point value or percentage of the course grade?

- Provided students (where appropriate) with models or samples?

Adapted from the WAC Clearinghouse at http://wac.colostate.edu/intro/pop10e.cfm .

CONTACT US to talk with an Eberly colleague in person!

- Faculty Support

- Graduate Student Support

- Canvas @ Carnegie Mellon

- Quick Links

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

1.1 Reading and Writing in College

Learning objectives.

- Understand the expectations for reading and writing assignments in college courses.

- Understand and apply general strategies to complete college-level reading assignments efficiently and effectively.

- Recognize specific types of writing assignments frequently included in college courses.

- Understand and apply general strategies for managing college-level writing assignments.

- Determine specific reading and writing strategies that work best for you individually.

As you begin this chapter, you may be wondering why you need an introduction. After all, you have been writing and reading since elementary school. You completed numerous assessments of your reading and writing skills in high school and as part of your application process for college. You may write on the job, too. Why is a college writing course even necessary?

When you are eager to get started on the coursework in your major that will prepare you for your career, getting excited about an introductory college writing course can be difficult. However, regardless of your field of study, honing your writing skills—and your reading and critical-thinking skills—gives you a more solid academic foundation.