- Skip to main content

- Skip to FDA Search

- Skip to in this section menu

- Skip to footer links

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you're on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

U.S. Food and Drug Administration

- Search

- Menu

- Resources for You (Food)

What You Need to Know about Foodborne Illnesses

PDF (313KB)

En Español (Spanish)

While the American food supply is among the safest in the world, the Federal government estimates that there are about 48 million cases of foodborne illness annually —the equivalent of sickening 1 in 6 Americans each year. And each year these illnesses result in an estimated 128,000 hospitalizations and 3,000 deaths.

The chart below includes foodborne disease-causing organisms that frequently cause illness in the United States. As the chart shows, the threats are numerous and varied, with symptoms ranging from relatively mild discomfort to very serious,life-threatening illness. While the very young, the elderly, and persons with weakened immune systems are at greatest risk of serious consequences from most foodborne illnesses, some of the organisms shown below pose grave threats to all persons.

For more information about food safety, call FDA's Food Information Line at: 1-888-SAFEFOOD or submit your inquiry electronically . The line is open Monday through Friday 10AM – 4PM EST except for Thursdays 12:30PM – 1:30PM EST and Federal Holidays.

Related Content

- Causes of Foodborne Illness: Bad Bug Book (Second Edition)

- People at Risk

An official website of the United States government

Here’s how you know

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

Food Safety and Inspection Service

- News & Events

- Food Safety

- Science & Data

Foodborne Illness and Disease

What is foodborne illness.

Foodborne illness is a preventable public health challenge that causes an estimated 48 million illnesses and 3,000 deaths each year in the United States. It is an illness that comes from eating contaminated food. The onset of symptoms may occur within minutes to weeks and often presents itself as flu-like symptoms, as the ill person may experience symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, or fever. Because the symptoms are often flu-like, many people may not recognize that the illness is caused by harmful bacteria or other pathogens in food.

Everyone is at risk for getting a foodborne illness. However, some people are at greater risk for experiencing a more serious illness or even death should they get a foodborne illness. Those at greater risk are infants, young children, pregnant women and their unborn babies, older adults, and people with weakened immune systems (such as those with HIV/AIDS, cancer, diabetes, kidney disease, and transplant patients.) Some people may become ill after ingesting only a few harmful bacteria; others may remain symptom free after ingesting thousands.

How Do Bacteria Get in Food?

Microorganisms may be present on food products when you purchase them. For example, plastic-wrapped boneless chicken breasts and ground meat were once part of live chickens or cattle. Raw meat, poultry, seafood, and eggs are not sterile. Neither is fresh produce such as lettuce, tomatoes, sprouts, and melons.

Thousands of types of bacteria are naturally present in our environment. Microorganisms that cause disease are called pathogens. When certain pathogens enter the food supply, they can cause foodborne illness. Not all bacteria cause disease in humans. For example, some bacteria are used beneficially in making cheese and yogurt.

Foods, including safely cooked and ready-to-eat foods, can become cross-contaminated with pathogens transferred from raw egg products and raw meat, poultry, and seafood products and their juices, other contaminated products, or from food handlers with poor personal hygiene. Most cases of foodborne illness can be prevented with proper cooking or processing of food to destroy pathogens.

Learn more about Pathogens

The Danger Zone

Bacteria multiply rapidly between 40 °F and 140 °F. To keep food out of this "Danger Zone," keep cold food cold and hot food hot .

- Store food in the refrigerator (40 °F or below) or freezer (0 °F or below).

- Cook all raw beef, pork, lamb and veal steaks, chops, and roasts to a minimum internal temperature of 145 °F as measured with a food thermometer before removing meat from the heat source. For safety and quality, allow meat to rest for at least three minutes before carving or consuming. For reasons of personal preference, consumers may choose to cook meat to higher temperatures.

- Cook all raw ground beef, pork, lamb, and veal to an internal temperature of 160 °F as measured with a food thermometer.

- Cook all poultry to a safe minimum internal temperature of 165 °F as measured with a food thermometer.

- Maintain hot cooked food at 140 °F or above.

- When reheating cooked food, reheat to 165 °F.

Learn more about food safety.

In Case of Foodborne Illness

Follow these general guidelines:

- Preserve the evidence. If a portion of the suspect food is available, wrap it securely, mark "DANGER" and freeze it. Save all the packaging materials, such as cans or cartons. Write down the food type, the date, other identifying marks on the package, the time consumed, and when the onset of symptoms occurred. Save any identical unopened products.

- Seek treatment as necessary. If the victim is in an "at risk" group, seek medical care immediately. Likewise, if symptoms persist or are severe (such as bloody diarrhea, excessive nausea and vomiting, or high temperature), call your doctor.

- Call the local health department if the suspect food was served at a large gathering, from a restaurant or other food service facility, or if it is a commercial product.

- Call the USDA Meat and Poultry Hotline at 1-888-MPHotline (1-888-674-6854) if the suspect food is a USDA-inspected product and you have all the packaging.

What Are Foodborne Pathogens?

There are different bacteria and pathogens that can cause foodborne illness.

Public Health Partners

Resources for sharing information or reporting foodborne illness.

Outbreaks: Response & Prevention

FSIS collaborates with CDC, FDA and APHIS for response and prevention efforts.

Foodborne Bacteria Table

Featured factsheets & resources.

Slow Cookers and Food Safety

Cleanliness Helps Prevent Foodborne Illness

Leftovers and Food Safety

Start your search, popular topics.

Foodborne Disease Outbreak Investigation Essay

Why investigate an outbreak, investigation proper, environmental investigation, dose response, case-control study, discussion and conclusion, reference list.

The outbreak is a series of similar events within a community or a particular region that is characterized by an illness the frequency of which exceeds the expectancy of a norm. The quantity of instances that show that the occurrence of an outbreak depends on the present agent of an infection, the size of the population that has been affected by the infection, previous instances of outbreaks, and lastly, the place and time when the outbreak occurred (Manitoba Health n.d., p. 1). In the majority of cases, an outbreak is related to an infectious disease, but an outbreak can also occur in a case of a non-infectious disease, for example, cancer or diabetes. However, the methods of investigation are similar for all types of outbreaks (Outbreaks investigations n.d., par. 1).

The main reason for an outbreak investigation is the identification of its source, When the source of an outbreak is identified, then control is being established in order to prevent future instances of an outbreak. Furthermore, an outbreak investigation is often implemented to train new employees and learn about the past disease and the methods of its transmission within a population. The decision to conduct an outbreak investigation is directly linked to its severity, the possibility of further spreading, or the political reasons influenced by a particular degree of deep concern expressed by the population (Outbreaks investigations n.d., par. 8).

The outbreak that will be investigated in this paper is the outbreak of the foodborne diseases because of an array of reasons such disease still remain a health challenge worldwide. Some foodborne diseases are taken under control while others pose a new danger to the population. Particular sections of a population under question are more likely to be affected by a foodborne disease because of their age, immunity suppression, or other conditions that affect the susceptibility to the disease.

Furthermore, individuals that travel to new environments can often be exposed to unfamiliar foods that may negatively affect their health. In the majority of countries, foodborne diseases occur as a result of people consuming food that is being prepared outside the house, and that is being frequently exposed to poor hygiene. Such challenges require continuous adaptations to the ever-changing environment that affect the spreading of the foodborne diseases as well as the development of innovative methods of dealing with the mentioned challenges (World Health Organization 2008, p. 5).

Public concern is one of the main features of an outbreak investigation. In investigating an outbreak, health authorities should find a perfect balance between the scientific aspect of an investigation and the ability to respond to public concern. Therefore, an outbreak investigation should complete a plan that outlines the ways in which relevant information is being presented to the concerned public. Furthermore, in some cases of an outbreak, close communication with the public will be instrumental in finding out about new instances of the disease under investigation.

Another important participant in the outbreak investigation is the media. It is an interface of the communication between the health organization and the public. By establishing a close connection with the media, a health organization that conducts the investigation will have an option to facilitate the reporting about the disease cases, give the public information about the ways the disease can be avoided, and maintain the support from the public (World Health Organization 2008, p. 7).

The relationship between a further investigation of the occurred outbreak and the measures of control relates to the amount of information about the known sources of an outbreak as well as they way these sources was transmitted (Investigating an outbreak n.d., p. 6).

A foodborne disease outbreak is an occurrence that is characterized by two or more individuals experience similar symptoms after being exposed to the same source of food, or there is otherwise evidence that particular food was a cause of the outbreak.

On the early morning of April 18th, the Department of Health in London received a concerned call from a mother whose son and daughter were suffering from a severe case of vomiting and nausea. They both got sick during the previous day and consumed some over-the-counter medication that gave no results. The children visited a Birthday party where they consumed some burgers and fries along with other children. The mother had also contacted other parents to ask whether their kids were okay. It had appeared that those children were having the same symptoms of nausea and vomiting. Furthermore, the Department of Health received similar calls in the course of the two following days. This was an obvious case of a foodborne disease outbreak.

The etiologic agents of the foodborne disease outbreak include bacterial toxins, bacterial infections, viruses, parasites, and noninfectious agents. A foodborne disease is usually accompanied by vomiting, diarrhea, nausea, and cramps in the abdominal area. By its own definition, foodborne diseases are being transmitted through the consumption of food; however, some of the bacteria agents can be transmitted through water, contact with animals as well as direct contact of person to person (Washington State Department of Health 2013, p. 3).

The contaminated food that may have been consumed by an individual may be contaminated from nature. They become acceptable for consuming after cooking. The examples of such foods are pork that can be affected by Yersinia enterocolitica, seafood affected by Vibrio parahaemolyticus, milk products affected by Salmonella or Cryptosporidium parvum and others. The second group of bacteria-contaminated food is the food that has been contaminated by poor handling. Poor handling includes contamination through dirt, unwashed hands, and infected lesions.

The virus of Staphylococcus aureus can easily contaminate food from the handler’s skin and quickly grow at room temperature thus producing a dangerous toxin that is stable to heat and cannot be eliminated by the process of cooking. The third way in which food products can be contaminated is the way of cross-contamination through other foods or the surrounding environment. The most common way is the cross-contamination of bacteria that come from raw meat and eggs on raw foods by the means of kitchen utensils and unwashed surfaces. The last and the least common way of food contamination is contamination by the means of intentional acts.

Microbiologic Investigation

On April 20th, the Department of Health made a visit to the emergency room at the local hospital to look at the records of thirty-five patients who all came in with the same problem of vomiting, nausea, and abdominal pains. The most prevalent symptom was vomiting that was detected in ninety-one percent of the affected individuals, then went diarrhea with eighty-five percent and abdominal pains with sixty-eight percent.

The average body temperature of the patients was 37.8C. All of the performed blood tests taken from fifteen patients showed a significant increase in white blood cells. By April 21st, there have been eighty-five instances of reported instances of a foodborne disease. All patients were recent visitors to their local fast food restaurant. The dates of the reported cases of illness were from April 18th to April 21st. The average age of affected patients was 15 years, ranging from seven to twenty-two years old.

Source: The common food item identified through the means of interviewing was a beef burger. When the food had been taken for analysis, there had been no evidence of a harmful bacteria. Thus, the food was probably contaminated by the means of cross-contamination from other products like salads, eggs, or badly prepared shellfish.

Incubation period: The period of incubation for a foodborne illness ranges from one day to one week. The most of the reported instances of illness were on April 18th-20th.

Leading Hypothesis: an infection that was spread through food or a drink served at the fast food restaurant.

On the basis of the clinical findings and the results of the interviews outlined above, the health investigators concluded that an outbreak was caused by a viral pathogen that most likely appeared in the food due to the process of cross-contamination in a fast-food restaurant between April 18th and April 21st. Thus, the environmental investigation consisted of interviewing restaurant staff on the types of products they handled, the meals served to customers as well as the places each employee worked in the restaurant.

Furthermore, restaurant employees had been questioned about whether they wore gloves as well as the hand washing policy in the kitchen, and whether anyone from the staff had been ill between April 18th and the 21st. In the restaurant, the burger preparing area had its own refrigerator. When order had been placed by the customer, burgers were made separately by an employee responsible for burgers. Each day new supplies of meat, lettuce, cheese, and vegetables were added to the refrigerator along with the products left from the previous day. However, when the restaurant had been open and orders had been coming in, there was no time for keeping all required products for a burger in a refrigerator. Furthermore, the containers for products were not cleaned on a regular basis.

Thus, the Health Department closed the restaurant on April 22nd. There was distinct evidence that the restaurant’s food had been the primary reason for the outbreak. The action of closing the restaurant was solely based on the circumstantial evidence (the restaurant had some issues with improper food handling). Because there was a number of unsanitary actions, closing a restaurant for a short period of time had been the smartest solution until the problems were resolved. Despite the fact that the most likely reason for the foodborne disease outbreak had been identified, it is crucial to conduct a further investigation because:

- the actual reason may not be the restaurant; however, it is most likely;

- more detailed information is required on the outbreak to find out whether the restaurant is safe to open again;

- more detailed information is required to prevent the outbreak from happening again (Gastroenteritis at a university in Texas n.d., p. 16).

The dose response is available in a case when the possibility of a foodborne illness is directly linked to the time of the exposure to the harmful ingredient. For instance, if an individual ate two burgers was more likely to become ill than a person that ate one burger, the dose response takes place. Thus, in order to support the hypothesis of a harmful exposure, the dose response must be supported. Evaluating a dose response is important in an outbreak when a population had been exposed to the same harmful agent, as the case with the fast food restaurant.

Paying attention to the design of the investigation is crucial in making sure that the dose response can be easily determined. The first step of the dose-response evaluation was asking questions about the levels of exposure to the harmful ingredient, for example, how many and how often the burgers were eaten. After evaluating the number and frequency of the eaten burgers in a fast food restaurant, then information on the relative risks, levels of exposure, and odds ratios is identified. Statistical significance of the dose-response metric can be calculated with the help of statistical test (World Health Organization 2008, p. 35).

In a circumstance like a case with the burgers, there is no clearly identified cohort of all individuals exposed to the illness because it was clear that not all cases were reported. Furthermore, not all non-exposed individuals can be asked questions about how they were feeling. In this case, when the most relevant information had been gathered. In this case-control study, the cases of ill individuals are compared to those of healthy (World Health Organization 2008, p. 30). The health institution used a questionnaire for getting information about the cases of an outbreak:

In this case-control study, 92% of the reported cases of illness had consumed the burger compared to 23% of the controls. Thus, the burger is suggested to be the primary reason for an outbreak. However, the relative risk cannot be identified with the use of the above table, because the quantity of all affected individuals is not known. Instead odd ratio is used and calculated as the cross-product:

Odds ratio= Ate the burger cases*Did not eat the burger controls/Ate the burger controls* Did not eat the burger cases

Odds ratio=35*50/15*3=38,8

The above-calculated odds ratio suggest a possible but not close relationship between the foodborne disease outbreak and the burger served at the fast-food restaurant as a primary source. Since the case-control study had been conducted two days after the last case of an outbreak, there was a possibility that the harmful bacteria was not present in the tested samples of the burger.

Appearing cases of foodborne disease outbreak still continue to arise and disturb the health care system. Furthermore, because of a variety of harmful bacteria, it is hard to successfully detect and treat the outbreak (Stephen & Ostroff 2000, par. 1). The foodborne disease outbreak investigated in the paper was indeed an outbreak because it was ‘defined as two or more illnesses caused by the same bacteria that are linked to eating the same food’ (Virginia Department of Health 2015, par. 1). All of the acquired results were issued to the public and the media in order to ensure that the cases of illness would not repeat again.

The fast food restaurant had been re-opened by the Public Health England when all testing were made, and there were no signs of poor food handling left. Furthermore, the Department of Health had encouraged the public to evaluate the risks associated with a foodborne disease and to carefully choose the places where to eat, paying close attention to the way employees handle the products (Department of Health n.d., par. 7).

The department of health had interviewed the individuals affected by the illness and made sure that the symptoms were treated and eliminated as soon as possible. To prevent the illness cases from occurring in the future, additional evaluation of the restaurant conditions and food handling habits had been conducted. Despite the fact that there had been no distinct type of bacteria found during the testing, the most likely source of the illness was the burger ingredients cross-contaminated by means of poor food handling.

A foodborne disease outbreak is not the one to be ignored or disregarded, so the Department of Health did everything in its power to quickly resolve the issue and make sure that no serious consequences occurred in those individuals who had suffered from the foodborne disease outbreak. Lastly, it is important to note that the media did a great job in providing the public with all necessary information on the outbreak, the ways to report it in a case of an illness, as well as the methods of prevention.

Department of Health n.d., About us .

Gastroenteritis at a university in Texas n.d.

Investigating an outbreak n.d.

Manitoba Health n.d., Epidemiological investigation of outbreaks .

Outbreaks investigations n.d.

Stephen, M & Ostroff, M 2000, Public health Systems and emerging infections: assessing the capabilities of the public and private sectors: workshop summary .

Virginia Department of Health 2015, Foodborne disease outbreaks .

Washington State Department of Health 2013, Foodborne disease outbreaks .

World Health Organization 2008, Foodborne disease outbreaks .

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2024, January 26). Foodborne Disease Outbreak Investigation. https://ivypanda.com/essays/foodborne-disease-outbreak-investigation/

"Foodborne Disease Outbreak Investigation." IvyPanda , 26 Jan. 2024, ivypanda.com/essays/foodborne-disease-outbreak-investigation/.

IvyPanda . (2024) 'Foodborne Disease Outbreak Investigation'. 26 January.

IvyPanda . 2024. "Foodborne Disease Outbreak Investigation." January 26, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/foodborne-disease-outbreak-investigation/.

1. IvyPanda . "Foodborne Disease Outbreak Investigation." January 26, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/foodborne-disease-outbreak-investigation/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Foodborne Disease Outbreak Investigation." January 26, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/foodborne-disease-outbreak-investigation/.

- Perceptions, Participation, and Change

- Salmonellosis and Food-Borne Poisoning

- The Causes of Food-Borne Illnesses

- Epidemiology. Salmonella Foodborne Outbreak

- Bacterial Factor in Foodborne Illness Cases

- Public-Service Bulletin for Food-Borne Illness

- Clostridium Perfringens Enterotoxin in Food-Borne Diseases

- Current Foodborne Outbreaks: Enoki Mushroom

- Foodborne Illness in “The Jungle” and Today

- Food Borne Diseases of Intoxicants on MSG

- HIV/AIDS as a Communicable Disease

- The Ebola Threat: Culture, Medicine, Authority and Risk

- Tuberculosis and Infectious Disease Slogan

- Medicine: Influenza, Its Causes and Impact on the People

- What Is Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome?

How to Prevent Food Poisoning

Foodborne illness (sometimes called food poisoning, foodborne disease, or foodborne infection) is common, costly—and preventable. You can get food poisoning after swallowing food that has been contaminated with a variety of germs or toxic substances.

Learn the most effective ways to help prevent food poisoning.

Following four simple steps at home—Clean, Separate, Cook, and Chill—can help protect you and your loved ones from food poisoning.

Learn the basic facts about food poisoning, who is most at risk, and how to prevent it.

You can protect your family by avoiding these common food safety mistakes.

Home-delivered groceries and subscription meal kits can be convenient, but they must be handled properly to prevent food poisoning.

Going out to eat? Here are tips to protect yourself from food poisoning while eating out.

If you have a recalled food item in your refrigerator, it’s important to throw out the food and clean your refrigerator.

- People at Higher Risk for Food Poisoning

- Recent Food Recalls

- Handwashing

- Multistate Foodborne Outbreak Investigations

- How Food Gets Contaminated

To receive regular CDC updates on food safety, enter your email address:

- FoodSafety.gov external

- Estimates of Foodborne Illness in the U.S.

- Foodborne Illness Surveillance Systems

- Environmental Health Services

Exit Notification / Disclaimer Policy

- The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) cannot attest to the accuracy of a non-federal website.

- Linking to a non-federal website does not constitute an endorsement by CDC or any of its employees of the sponsors or the information and products presented on the website.

- You will be subject to the destination website's privacy policy when you follow the link.

- CDC is not responsible for Section 508 compliance (accessibility) on other federal or private website.

We use cookies to enhance our website for you. Proceed if you agree to this policy or learn more about it.

- Essay Database >

- Essay Examples >

- Essays Topics >

- Essay on Food

Expertly Written Essay On Food-Borne Illness Outbreak In The United States To Follow

Type of paper: Essay

Topic: Food , Health , People , Medicine , Borne , Disease , Proper , States

Published: 03/30/2023

ORDER PAPER LIKE THIS

Food-borne Illness

Food is the basic necessity of every human being. It has evolved into many forms, making it easier for people and animals to consume them. However, there are still circumstances wherein food can cause not only harm to people, but also deaths. One way by which this can occur, is through food-borne illnesses and diseases. Food-borne illness, or more commonly known as food poisoning, is an illness that is caused by consuming food that are contaminated with bacteria and chemicals (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2015).

Food-borne Disease Outbreaks

Food-borne illnesses are conditions that people should not take lightly because though these diseases may seem to have less severe effects, this can be fetal if not given with immediate attention. One of the most recent food-borne illness outbreaks in the United States happened in 36 states. This Salmonella Poona outbreak has caused 4 fatalities and 767 infected across the 36 states in the country (Siegner, 2015). According to experts, the bacteria has been found to come from cucumbers. This very matter is what makes it very important for people to take food-borne illnesses seriously, because one moment, only one person is infected, but the next minutes, more people will also surely be infected when the situation is not handled properly and taken care of immediately. This outbreak could have been prevented if only people become more observant and aware of the shelf life of the food that they consume. Another way by which people could also avoid these circumstances is through proper food handling. This will ensure that the food that goes inside peoples bodies are clean and are safe to be eaten. Lastly, another way by which people could avoid further cases of food-borne illnesses is just by observing the expiration date of the food before they consume it. Because of the outbreak, the officers from the California health department recalled every batch of the garden cucumber that has caused the outbreak.

Food Safety

It is important for every manufacturing company, farmers, and all other people involved in food production to practice proper sanitation and proper food handling in order to avoid the case mentioned above. Workers in manufacturing companies should observe proper hygiene and attire when working, in order to avoid possible chances of food contamination. Through practice safety and sanitation standards, companies surely wouldn’t need to worry about losing profit or worse, closure, if they observe proper standards, and maintain the quality of their products.

Siegner, C. (2015, October 14). CDC Update: 4 Deaths, 767 Salmonella Cases in 36 States Linked to Cucumbers. Retrieved August 30, 2016, from http://www.foodsafetynews.com/2015/10/1-death-more-than-300-confirmed-salmonella-cases-in-27-states-linked-to-mexican-cucumbers/#.V8gZBDWI9mw Foodborne Germs and Illnesses. (2015). Retrieved August 30, 2016, from http://www.cdc.gov/foodsafety/foodborne-germs.html

Cite this page

Share with friends using:

Removal Request

Finished papers: 1062

This paper is created by writer with

ID 287306018

If you want your paper to be:

Well-researched, fact-checked, and accurate

Original, fresh, based on current data

Eloquently written and immaculately formatted

275 words = 1 page double-spaced

Get your papers done by pros!

Other Pages

The calling of jonah essays example, good essay about ethnic groups in the military and security institutions, free average costs fixed cost total variable cost number of units case study sample, the strengths perspective in social work practice report sample, the law of negligence essay you might want to emulate, free chinese media case study case study sample, expertly crafted essay on functional space in tanner and jamison landscapes, good essay about drug awareness, a level essay on steep analysis of the oasis of the seas for free use, free dissertation about critical evaluation, filmmaking research paper, frida kahlo example research paper by an expert writer to follow, free contemporary capitalism essay sample, example of history of rap essay, good example of essay on toxicology, relationships between performers article review template for faster writing, convention against torture the issue of abu ghraib prison research paper you might want to emulate, good essay on about the interview, free strategies of visual understanding essay sample, good critical thinking about trust commitment effort, maple leaf shoes ltd case studies examples, factual scenario of concepts of criminal law essays example, time off request system a sample capstone project for inspiration mimicking, expertly written essay on apple samsung strategic competitiveness analysis to follow, write by example of this mobile technology essay, free essay about coworking, expertly crafted essay on factors of test worthiness, marketing strategies report, free tort of negligence product liability creative writing sample, a level case study on the irrelevant questions for free use, good question answer about health care information system, why is there a difference between the yield percents question answer to use for practical writing help, hazards at an oil refinery fire case study to use for practical writing help, write by example of this fredrick douglas and harriet jacobs essay, birth of the land essay example, greeting cards essays, greeting card essays, procurements essays, lessons for children essays, collagenase essays, alliant essays, sask essays.

Password recovery email has been sent to [email protected]

Use your new password to log in

You are not register!

By clicking Register, you agree to our Terms of Service and that you have read our Privacy Policy .

Now you can download documents directly to your device!

Check your email! An email with your password has already been sent to you! Now you can download documents directly to your device.

or Use the QR code to Save this Paper to Your Phone

The sample is NOT original!

Short on a deadline?

Don't waste time. Get help with 11% off using code - GETWOWED

No, thanks! I'm fine with missing my deadline

- The Open University

- Explore OpenLearn

- Get started

- Create a course

- Free courses

- Collections

My OpenLearn Create Profile

- Personalise your OpenLearn profile

- Save Your favourite content

- Get recognition for your learning

Already Registered?

- Hygiene and Environmental Health Module: Ethiopian Federal Ministry of Health

- Hygiene and Environmental Health Module: Acknowledgements

- Hygiene and Environmental Health Module: Introduction

- Hygiene and Environmental Health Module: 1. Introduction to the Principles and Concepts of Hygiene and Environmental Health

- Hygiene and Environmental Health Module: 2. Environmental Health Hazards

- Hygiene and Environmental Health Module: 3. Personal Hygiene

- Hygiene and Environmental Health Module: 4. Healthful Housing

- Hygiene and Environmental Health Module: 5. Institutional Hygiene and Sanitation

- Hygiene and Environmental Health Module: 6. Important Vectors in Public Health

- Hygiene and Environmental Health Module: 7. Introduction to the Principles of Food Hygiene and Safety

- Hygiene and Environmental Health Module: 8. Food Contamination and Spoilage

- Introduction

- Learning Outcomes for Study Session 9

- 9.1 Overview of foodborne diseases

9.2 Transmission of foodborne diseases

9.3.1 Food poisoning

- 9.3.2 Food infection

- 9.3.3 A catalogue of foodborne diseases

- 9.4.1 Bacterial infections

- 9.4.2 Viral infections

- 9.4.3 Tapeworms

- 9.4.4 Bacterial food poisoning

- 9.4.5 Chemical food poisoning

- 9.5 General management of foodborne diseases

- 9.6 Investigation of foodborne disease outbreaks

- Summary of Study Session 9

- Self-Assessment Questions (SAQs) for Study Session 9

- Appendix 9.1

- Hygiene and Environmental Health Module: 10. Food Protection and Preservation Methods

- Hygiene and Environmental Health Module: 11. Hygienic Requirements of Food and Drink Establishments

- Hygiene and Environmental Health Module: 12. Hygiene and Safety Requirements for Foods of Animal Origin

- Hygiene and Environmental Health Module: 13. Provision of Safe Drinking Water

- Hygiene and Environmental Health Module: 14. Treatment of Drinking Water at Household and Community Level

- Hygiene and Environmental Health Module: 15. Community Drinking Water Source Protection

- Hygiene and Environmental Health Module: 16. Sanitary Survey of Drinking Water

- Hygiene and Environmental Health Module: 17. Water Pollution and its Control

- Hygiene and Environmental Health Module: 18. Introduction to the Principles and Concepts of Waste Management

- Hygiene and Environmental Health: 19. Liquid Waste Management

- Hygiene and Environmental Health Module: 20. Latrine Construction

- Hygiene and Environmental Health Module: 21. Latrine Utilisation – Changing Attitudes and Behaviour

- Hygiene and Environmental Health Module: 22. Solid Waste Management

- Hygiene and Environmental Health Module: 23. Healthcare Waste Management

- Download PDF versions

- Hygiene and Environmental Health Part 1 PDF (1.4MB)

- Hygiene and Environmental Health Part 2 PDF (1.29MB)

Download this course

Download this course for use offline or for other devices.

The materials below are provided for offline use for your convenience and are not tracked. If you wish to save your progress, please go through the online version.

About this course

- 46 hours study

- 1 Level 1: Introductory

- Course description

Hygiene and Environmental Health

If you create an account, you can set up a personal learning profile on the site.

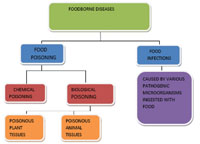

9.3 Classification of foodborne diseases

Foodborne diseases are usually classified on the basis of whatever causes them. Accordingly they are divided into two broad categories: food poisoning and food infections . Each of these categories is further subdivided on the basis of different types of causative agent (see Figure 9.1). We will discuss each of them in turn.

For further information, take a look at our frequently asked questions which may give you the support you need.

Have a question?

If you have any concerns about anything on this site please get in contact with us here.

Report a concern

Dissertation

Research Paper

- Testimonials

Research Papers

Dissertations

Term Papers

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- December 2012

- February 2012

- January 2012

- September 2011

- August 2011

- February 2011

- January 2011

- October 2010

- September 2010

- August 2010

- February 2010

- January 2010

- December 2009

- November 2009

- October 2009

- September 2009

Food-Borne Illnesses Essay

Food borne illness or food borne disease refers to the diseases that occur due to consumption of contaminated food. It is also called food poisoning in colloquial language. There are two types of food poisoning. One of them is toxic agent in which the food becomes toxic due to bacterial action or action of other microorganisms. The other is infectious agent food poisoning in which the infectious microorganisms enter the body through contaminated food. Toxic form of food poisoning may occur when the microorganisms are no longer present but they have produced such toxics like serotoxins which results in food borne illness.

Quick Navigation through the Food-Borne Illnesses Essay Page

- A Food Borne Illness Essay

How Can We Help?

- A Food Borne Illnesses Paper

- A Food Borne Illnesses Summary

- A Food Borne Illnesses Book Report

- A Food Borne Illnesses Review

Food Borne Illnesses Writing

- A Food Borne Illnesses Speech

Food Borne Illnesses. Causes

Symptoms of food borne diseases, how to prevent food borne diseases, download free sample of a food borne illness essay, food-borne illnesses essay sample (click the image to enlarge), food borne illness essay.

Food borne illness essay is the writing, which major purpose is to enclose the problem of food borne illness and help to prevent it. By this illness one often understands getting sick through contaminated food. That is why any paper written on this topic should include the information about this food and symptoms of food borne illness . The symptoms are following: 1) upset stomach, 2) fever, 3) dehydration, 4) diarrhea, 5) abdominal cramps, 6) nausea and vomiting. Moreover, one should mention the cause for such disease to make the paper complete and useful for the readers. The reasons of food borne illness are harmful bacteria. Every food may have such bacteria. It is necessary to mention that bacteria may appear in the kitchen in case you leave food out for more than two hours. Everybody should be very attentive not to get this illness. Writing food borne illness essay is one of the means of becoming more aware of this problem.

This article from ProfEssays.com will help you to understand what food borne illness is, what its symptoms are and how we can save ourselves from this disease. If you need an elaborated food borne illness essay or you want to have food borne illness research paper , our expert writers can help you in submitting a required paper with necessary details. You can also ask ProfEssays.com to help you to research this topic. Our prices will pleasantly impress your expectations!

Food Borne Illnesses Paper

Food borne illnesses paper gives you a splendid opportunity to learn more about the problem under consideration. Each writing requires looking for basic information. The more you read the more you remember; that is why you may be asked to write papers on such topics as food borne illnesses paper . Do not forget about the structure of your paper. It depends upon the type of paper you are going to submit.

Food Borne Illnesses Summary

Food borne illnesses summary is written to show that a student fully understands the text about food borne illness . There are several tips that are necessary for writing a successful summary. They are the following ones: 1) pay attention to headings and subheadings of the text, 2) read and reread the text, 3) choose the main idea for each section, 4) prepare a thesis statement , 5) write the paper, and 6) revise the things written.

Food Borne Illnesses Book Report

A food borne illnesses book report should include such elements as title, abstract, introduction, background, past and related work, technical sections, results, future work, and conclusions. Each of these items is important. But before getting down to work you must know that one of the guarantees of excellent book report is starting writing it in time, long until the deadline. It is also important to think about your audience while writing.

Food Borne Illnesses Review

Food borne illnesses review must be written according to several major steps: start with a category, work out clear criteria, make judgment, gather evidence, and sum up the information you have written. In a good pithy report any judgment is based on a certain criterion; that is why think over this point carefully. Do not forget to gather enough evidence to support every argument you are going to present in the review .

Food borne illnesses writing should give the most essential information about food borne illnesses . It is possible to enlarge upon the ways of treatment in this paper. The treatment frequently increases the fluid intake. Quite often patients are treated at the hospital. The paper should stress that this illness is very dangerous. For instance, 5000 people die because of this disease annually. This illness must be treated by everyone very seriously. A good writing should include the ideas and suggestions that may change the situation for the better.

Food Borne Illnesses Speech

Food borne illnesses speech should enclose the major points concerning the problem under analysis. There may be 3-7 points in your speech. They should be prioritized according to the level of importance. Read the information you have chosen for the speech several times and delete unnecessary information. This writing must start with a good introductory part that will catch the attention of the audience. Do not forget to place logical ties between the points of your speech.

Although food borne diseases are referred as food poisoning, not many cases occur due to toxins. The most diseases are caused due to pathogens like bacteria, viruses or parasites that contaminate the food. These diseases occur due to contaminated food. Thus, it is necessary to have clean and safe food to avoid these diseases. Also we should avoid eating stale food. If there is some smell in stale food we should not eat it, as there may be toxins and harmful microbes in it.

The symptoms of food borne diseases may be visible within hours of consuming contaminated food or sometimes they may occur after two or three days. Symptoms can be mild or severe. It depends upon the pathogen that entered the body. A person with food borne illness can recover after two or three weeks. It is an acute disease and there is no long illness. But in some cases it can be fatal. If it occurs to babies, pregnant women or persons with liver problems, then it could prove to be deadly. Food borne illness caused due to eating of infectious fish or other animal can result in long term ailment or allergy.

Food borne illness occurs due to contaminated food. This happens when the food is poorly handled or cooked. It can occur when there is shortage of food and people are forced to eat whatever they get. This can happen at time of natural calamities or war. It can also occur due to poor hygiene practice before and after eating food. One should wash hands properly before eating and after eating food to avoid food borne diseases. Other reason of food borne illness is consumption of out of date food. Therefore you should see the expiration dates of canned or packed food items before consuming them. If food is cooked, then there are chances of toxics in it which you can check by smelling it. Cooked food can be contaminated even in 2 hours of cooking at room temperature, so it is vital to store the food at proper temperature in order to preserve it. Refrigeration can slow down the process of contamination. Partially cooked meat and fish can also result in food borne illness. Food contamination can even occur during food growing, harvesting, storing or transporting. Food is easily contaminated in moist and warm weather.

Food borne diseases can be diagnosed by various pathological tests. The doctor will ask to go for some tests depending upon the symptoms that are visible in patient. Food borne illness is easy to be diagnosed if it is caused by known pathogen. But when an unknown organism enters the body, then it is more difficult and may take several days to be diagnosed.

Food borne illness can be prevented by following proper hygiene while cooking and eating. These simple steps can reduce a lot of diseases:

- Food should be properly cooked at right temperature.

- If the food stands out for two hours after cooking, then it should be kept in a refrigerator.

- The knives and other utensils should be properly cleaned, as bacteria can spread from one food to another.

- Meat and fish should be cooked at high temperature to kill the microorganisms that are present in it.

- Wash your hands with warm water and medicated soap after you have handed poultry food item.

- Dish towels and sponges should be sanitized once in a week. This can be done by using bleach powder.

- Always keep a clean hand towel in your kitchen.

- Wash all vegetables and fruits before consuming them.

Note: ProfEssays.com is an outstanding custom writing company. We have over 500 expert writers with PhD and Masters level educations who are all ready to fulfill your writing needs, regardless of the academic level or research topic. Just imagine, you place the order before you go to sleep and in the morning an excellent, 100% unique essay ! or term paper, written in strict accordance with your instructions by a professional writer is already in your email box! We understand the pressure students are under to achieve high academic goals and we are ready help you because we love writing. By choosing us as your partner, you can achieve more academically and gain valuable time for your other interests. Place your order now !”

Looking for an exceptional company to do some custom writing for you? Look no further than ProfEssays.com! You simply place an order with the writing instructions you have been given, and before you know it, your essay or term paper, completely finished and unique, will be completed and sent back to you. At ProfEssays.com, we have over 500 highly educated, professional writers standing by waiting to help you with any writing needs you may have! We understand students have plenty on their plates, which is why we love to help them out. Let us do the work for you, so you have time to do what you want to do!

- Customers' Testimonials

- Custom Book Report

- Help with Case Studies

- Personal Essays

- Custom Movie Review

- Narrative Essays

- Argumentative Essays

- Homework Help

- Essay Format

- Essay Outline

- Essay Topics

- Essay Questions

- How to Write a Research Paper

- Research Paper Format

- Research Paper Introduction

- Research Paper Outline

- Research Paper Abstract

- Research Paper Topics

Client Lounge

Deadline approaching.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Int J Environ Res Public Health

Food-Borne Disease Prevention and Risk Assessment

“Food-borne Disease Prevention and Risk Assessment” is a Special Issue of the International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health on understanding how food-borne disease is still a global threat to health today and to be able to target strategies to reduce its prevalence. Despite decades of government and industry interventions, food-borne disease remains unexpectedly high in both developed and developing nations. For instance, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimates that one in six persons in the United States suffers from gastroenteritis each year, with up to 3000 fatalities arising from consumption of contaminated food [ 1 ]. According to the WHO Initiative to Estimate the Global Burden of Food-borne Diseases, 31 global hazards caused 600 million food-borne illnesses and 420,000 deaths in 2010; diarrheal disease agents were the leading cause of these in most regions caused by Salmonella, but Taenia solium , hepatitis A virus, and aflatoxin were also significant causes of food-borne illness [ 2 , 3 ]. The global burden of food-borne disease by these 31 hazards was 33 (95% UI 25–46) million Disability Adjusted Life Years (DALYs) in 2010; 40% of the food-borne disease burden was among children under five years of age. Since we know that most food-borne diseases are preventable, these are astonishing figures for the 21st century. We are familiar with some of the underlying conditions: unsafe water used for the cleaning and processing of food, poor food-production processes, inadequate storage, and food-handling practices including infected food workers and cross-contamination of food. These can be coupled with inadequate or poorly enforced regulatory standards and industry compliance. However, knowledge of these is not enough. Making advances in prevention and control practices requires a suite of interlinked actions from improvements in the investigation of complaints and illnesses to finding the root cause of outbreaks; applying rapid and accurate identification of the hazards present; determining the conditions in which pathogens grow and multiply in order to eliminate or reduce these numbers; developing targeted intervention strategies; understanding human behavior with respect to food processing and its preparation; producing effective educational and training programs; evaluating the risks of existing and modified food production and preparation practices; predicting how effective potential interventions would be, and introducing effective and enforceable codes of practice for the different harvesting, processing, and preparing industry components. The human element is now known to be critical in applying safe practices to prevent food-borne illnesses, but it is much more difficult to influence for positive change, both from the culture of an organization and individual backgrounds and preferences. This issue is a modest attempt to explore some of these efforts through five publications.

Most agents causing food-borne illness have been identified over the last 145 years, starting from the pioneering work of Robert Koch who identified the cause of anthrax, tuberculosis and cholera. He also dismissed the then-current concept of spontaneous generation, used agar as a base for growing bacteria, and proposed his four postulates: (1) the organism must always be present, in every case of the disease; (2) the organism must be isolated from a host containing the disease and grown in pure culture; (3) samples of the organism taken from pure culture must cause the same disease when inoculated into a healthy, susceptible animal in the laboratory; (4) the organism must be isolated from the inoculated animal and must be identified as the same original organism first isolated from the originally diseased host. Over time, however, the rigid application of these postulates probably hindered research into the discovery of new agents, particularly viruses which initially could not be seen or isolated in culture. Today, nucleic acid-based microbial detection methods have made Koch’s original postulates less relevant, because these methods make it possible to identify microbes associated with a disease, even if they are non-culturable. Prions are another class of agents that do not fit into the classical infectious disease agent being misfolded proteins with the ability to transmit their misfolded shape onto normal variants of the same protein to cause transmissible neurodegenerative diseases in humans and some animals. Thus, a challenge today is to be prepared to identify and characterize new infectious agents which can arise from unexpected sources. This applies to coronaviruses which have recently been brought to the public’s attention where humans have been infected from animal sources. These include severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV), for which bats are a major reservoir of many strains, and other strains have been identified in palm civets; Middle East respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus (MERS-CoV), is a species of coronavirus which also has reservoirs in bats, and but has spread to camels and from there to humans, particularly camel handlers; and the current COVID-19 virus pandemic affecting millions of people worldwide, which likely originated from wet markets in Wuhan, China, where domestic and wild animals are slaughtered for customers; however, significantly, bats may also be the primary reservoir.

This background makes the paper of Wen, Sun, Li, He and Tsai [ 4 ], Avian Influenza—Factors Affecting Consumers’ Purchase Intentions toward Poultry Products , all the more relevant for those seeing increasing links between animals and human diseases. Influenza viruses, belong to the Orthomyxoviridae, a different family from the coronaviruses; yet, strains of both of these infect humans and animals, and some can be transmitted from animals to humans; these include the H1N1 avian influenza (swine flu) of 2009, which killed between 151,000 and 575,000 people worldwide) and H5N1, strain (popularly known as the bird flu) which had pandemic potential. In particular, poultry production and sales have led to the spread of H5N1 and other avian influenza viruses [ 5 ]. This strain was first isolated from a goose in China in 1996 and it spread throughout Asia and Europe over the next decade with associations of wild birds and poultry. Large sums of money were spent in order to eliminate this disease despite the relatively few associated human illnesses and deaths worldwide, and most Europeans who had limited exposure to H5N1 feared any new viruses such as the avian flu and avoided uncooked chicken products [ 6 ]. Poultry production dropped 25-30% in many Asian countries, including China. A subsequent avian influenza strain, A H7N9, also caused human infections although the number of human cases transmitted by this strain was more limited than for H5N1. Nevertheless, populations in Asia and particularly China have been sensitized to the potential risks of human infections and economic damage from news’ reports of avian influenza. The paper of Wen et al. [ 4 ] focuses on the purchase intentions consumers in Guangzhou, China, during recurring reports of this epidemic. Avian influenza A H7N9 virus had not previously been seen in either animals or people until it was found in March 2013 in China. However, since then, infections in both humans and birds have been observed, and the disease is of concern because most patients have become severely ill. Most of the cases of human infection with this avian H7N9 virus were associated with recent exposure to live poultry or potentially contaminated environments, especially markets where live birds have been sold. This virus does not appear to transmit easily from person to person, and sustained human-to-human transmission has not been reported. However, according to the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) [ 7 ], case-control studies suggest contact with poultry or a visit to a live poultry market in the two weeks prior to disease onset was a significant risk factor. Cases have been reported in humans who visited live bird markets, slaughtered poultry or pigeons, transported poultry, and brought live poultry into their homes. As of December 2019, the number of confirmed human cases and deaths was 1568 and 616, respectively, and 26 live markets in 15 Chinese provinces tested positive for the virus, mainly in chicken samples [ 8 ]. Thus, it is understandable that Chinese purchasers of recently slaughtered poultry should have concerns for their health, and they would consider avoiding purchasing any chicken products.

Wen et al. [ 4 ] found, unsurprisingly, that from a risk perception perspective, the more consumers believed purchasing chicken products was a risk during a period of this avian influenza outbreak, the more they reduced their purchase of chicken products, since they had low levels of trust in the quality of chicken meat. Since the public receives most of its information on avian influenza and its relationship to human illness, animal diseases and food contamination, through the mass media as it is narrated and shown to consumers, will influence and change their willingness to purchase chicken products. The authors recommended that government provides accurate information on the public health system to ensure the stable and healthy development of the poultry meat products or consumers, and to rebut any misleading media reports. However, this depends on how much trust the people are willing to place on government agencies. As Bánáti [ 6 ] indicates, there was distrust in the past in industry and government oversight of the food supply developed because of food scares such mad cow disease, dioxin in pork, melamine in pet and baby food, and now more recently in outbreaks of avian influenza, and the current COVID-19 pandemic. Although coronaviruses, particularly COVID-19, are not food-borne, the worldwide public may be overly cautious about any food they purchase and wet markets in Asia may see a drop in attendance at least until such pandemics are over. It would be interesting to explore how long anxiety over food purchases occur after this pandemic is over, but it seems the longer they last through media coverage, the more the concern will remain.

The second paper in this series, entitled Cognitive Biases of Consumers’ Risk Perception of Food-borne Diseases in China: Examining Anchoring Effect by Shan, Wang, Wu and Tsai [ 9 ], also focuses on the perception of risks of food-borne illness in China. The authors indicate that the home is the place where the largest number of food-borne illness cases occur in China, and one of the reasons for this is that many consumers are not aware of their vulnerability to such illnesses and they underestimate their risk. This seems to be opposite to the findings of Wen et al. [ 4 ] where consumers are very concerned about avian influenza transmission, but the contrast can be explained because there is virtually no media coverage of food-borne illnesses at home. Because consumers seem to have limited knowledge of the risks, the authors propose that they tend to use an anchoring strategy on which to base their food-borne disease prevention and control decisions. The authors argue that since consumers are not always rational in making decisions, they often adjust their judgments on their subjective understanding and their initial reference information (called the initial anchor). However, other factors such as an uncertain external environment and limited knowledge make consumers unsure of the extent to which they can adjust their estimates. These limitations in information processing result in biased anchoring results, which they call the “anchoring effect”. The authors postulate that because Chinese citizens have limited scientific literacy compared with those in developed countries, Chinese consumers should have significant cognitive biases including the anchoring effect. Although there are few reports on whether there is an anchoring effect in consumers’ risk perception of food-borne disease, previous studies of other diseases have confirmed that there is indeed an anchoring effect, such as overestimating the risks of breast cancer. To test whether or not consumers’ limited knowledge results in a significant anchoring effect, the authors collected survey data from 375 consumers in Wuxi, Jiangsu Province. A questionnaire obtained information on how much the respondents knew about food-borne diseases and how they could be prevented. Based on the approximate national food-borne disease prevalence rate of 15% of the population, in this study 30% and 5% food-borne disease prevalence were selected as high and low anchor values, respectively. This experimenter-provided anchor value, a history of food-borne disease, and familiarity with those diseases were found to be important factors influencing the respondents’ anchoring effect. They found that when more information was provided to the respondents in the study (considered as a short-term intervention), their risk perception was improved to some extent, but there were still anchoring biases. As a result, Shan et al. [ 9 ] argue that short-term interventions would not substantially change consumers’ anchoring effect, and there is a need for stronger and more long-term interventions. They recommend that government should play an active role in publicity and education aimed at the public about food-borne diseases. Specifically, the prevalence and scientific context about different food-borne diseases should be disseminated to consumers through various media, such as the internet, television, and radio, to warn consumers of the objective risks of these diseases. Therefore, they argue that improving consumers’ risk perception of food-borne disease is critical to the long-term prevention of illness from these risks. They concluded that government should strengthen active monitoring, publicity, and education about food-borne disease, so that individuals are more knowledgeable scientifically to improve their perception in making judgments about risks of food-borne disease. However, knowledge alone may not be enough. Da Cunha et al. [ 10 ] found that education is not as effective as training in school food handlers in Brazil. Rossi et al. [ 11 ] observed that although food handlers have knowledge of microbiological risks, their risk perception has a weak association with food safety knowledge. They stated that, unfortunately, food handlers demonstrate an awareness of food safety, but they generally fail to translate that knowledge into safe practices because of their optimistic bias. Optimistic bias is a psychological phenomenon in which people believe they are less likely to experience adverse events than others, such as in home-prepared meals. This concern also applies to consumers eating out; they can incorporate a sense of affection and identity to a place, associating it with making their own meals at home, and do not identify the risk of food-borne disease while eating at those restaurants [ 12 ]. Like food handlers, consumers have a feeling of overconfidence in the restaurant they eat with their optimistic bias. This result reinforces the need for governments and health agencies to protect the health of the population. Wildemann [ 13 ] also points out that although food-borne illnesses contribute substantially to the overall burden of disease, including hospitalizations, economic loss, and death, in contrast to food safety experts, the public usually perceives food-borne diseases as low risk. This distinguishes the differences in the perception of the risk between experts and the public. Wildemann [ 13 ] lists many qualitative factors affecting risk perception and evaluation. These include mild symptoms vs. potential fatal consequences or delayed adverse effects; dread or low concern for a certain disease; reversibility of the effects of the disease (e.g., long-term sequelae, reduced quality of life, or rapid recovery); previous history of the disease in the family or community; existing health of the individual, e.g., immunocompromised; familiarity of the agents or disease and understanding its means of transmission; increasing or decreasing public concern; exposure and impact controllable; risk determined by personal actions or mistakes made by others; trust in institutions; much or little media attention to the concern. Rosati and Saba [ 14 ] found that the concern about food risks was found to be statistically significantly dependent on the perception of risk to the individual. Usually, food-borne illness will not evoke outrage among lay people because they are perceived as voluntary, controllable, visible, and familiar. This means that most individuals perceive the threats of food-borne diseases as low, although food can pose significant risks. In particular, food-borne illness originating in the home is perceived as familiar and controllable.

For Wuxi consumers and, by extrapolation, for Chinese residents on the whole, there should be a low perceived risk even though the prevalence of food-borne disease in China is as high as 15%. This is similar to the percentage in the USA (17%) where, according to Scallan et al. [ 1 ], one in six persons is estimated to suffer from food-borne illness each year. Wildemann [ 13 ] emphasizes among the factors associated with increased concern are high media attention, and any risk message and its originator are crucial components for informing the public what actions to take of any food-borne disease concern; she emphasizes that if the public does not consider the source credible, it will be difficult to convey the message and effect long-term changes in attitude. This seems to be consistent with a long-term-held anchoring effect described by Shan et al. [ 9 ]. Credibility has two dimensions: expertise and trustworthiness. Expertise refers to the knowledge in a specific area and trustworthiness to the reliability of the message content. Trust depends on three factors: knowledge expertise, honesty concerning the completeness of the provided information, and whether the concerns of the consumers are taken seriously or not by the risk message originator [ 14 ]. Therefore, trust plays a major role in the credibility and acceptance of an institution to influence the processing of risk information and potential changes in consumer behavior. Involving the media during the whole process may enhance the trust of the public in food safety policy. All this information questions whether it is possible, without extensive government media campaigns and perhaps a scare factor like avian influenza in a population, to substantially change attitudes and behaviors towards food safety through reducing the anchoring effect. Unfortunately, although food scares draw public attention, they can also create false or misleading information that has to be countered by the experts [ 6 ], and the public may become polarized between being ultra-protective of personal and family health to a cavalier attitude to throw caution to the wind, as seems to be the case in the current COVID-19 pandemic.

The discussion on perception and communication of risk and how translate government polices into changed behavior takes us to the third paper in this issue, that of Farias, Akutsu, Botelho, and Zandonadi [ 15 ] discussing Good Practices in Home Kitchens: Construction and Validation of an Instrument for Household Food-Borne Disease Assessment and Prevention . The purpose of the study was to develop and validate an instrument to evaluate Brazilian home kitchens’ good practices. the rationale for this was for food preparers at home to avoid food-borne diseases illnesses by adopting preventive actions throughout the home food production chain. Although governments regulate food safety practices in commercial food production and food service establishments, there are no regulations on how to control food preparation and handling in the home. From the work of Rossi et al. [ 11 ] and Shan et al. [ 9 ], consumers may have an optimistic bias that creates an anchoring effect to fix consumers’ the risks associated with food-borne illness. Therefore, there needs to be more information on how to reduce food-borne domestic cases through improving food handling practices. After the instrument was developed, the content was validated using the Delphi technique with independent food hygiene and food safety specialists, and a focus group for validation of the criteria. The study showed that consumers in Brazil tend not to perceive themselves, or someone in their family, to be susceptible to food-borne illness; rank their risk of food-borne illness lower than that of others; and/or do not follow all recommended food safety practices, and, consequently, they do not take sufficient precautions to prevent illnesses from occurring. The authors found that food was prepared in the home where there were heavily contaminated areas in the kitchen (refrigerator handles, tap handles, sink drain areas, dishcloths, and sponges) because it is unusual for these surfaces to be frequently washed or cleaned. Additionally, raw or unwashed foods were constantly touched during meal preparation. The authors state that because there is limited guidance for home food preparers, the use of an such an instrument helps evaluate the level of food safety at home, and identifies unsafe practices in food handling for targeted prevention and control strategies though improving consumer knowledge about food and waterborne diseases and their consequence. Farias et al. [ 15 ] certainly developed a method to comprehensively understand the risk of home food preparation in a Brazilian community and presumably would have global value for helping to reduce risks that have led to the annual estimate of 600 million food-borne illnesses worldwide [ 3 ]. Similar studies have been done in the past such as that of Redmond and Griffith [ 16 ] who said that knowledge, attitudes, intentions, and self-reported practices do not correspond to observed behaviors, suggesting that observational studies provide a more realistic indication of the food hygiene actions actually used in domestic food preparation. Only an improvement in consumer food-handling behavior is likely to reduce the risk and incidence of food-borne disease. So, the question remains that unless food preparers are motivated, it may be very hard to change perceptions of risk of illness to themselves or who they serve. As Collins [ 17 ] pointed out 23 years ago, only 50% of consumers were concerned about food safety, partly because of lifestyle changes affecting food behavior, with an increasing number of women in the workforce, limited commitment to food preparation, and a greater number of single heads of households. Then, as now, it may be that consumers appear to be more interested in convenience and saving time than in proper food handling and preparation. Fischer et al. [ 18 ] showed that while most consumers are knowledgeable about the importance of cross-contamination and heating in preventing the occurrence of food-borne illness, this knowledge is not necessarily translated into behavior. Potentially risky behaviors were observed in the domestic food preparation environment with errors like participants allowing raw meat juices to come in contact with the final meal. The authors stated that procedural food safety knowledge (i.e., knowledge proffered after general open questions) was a better predictor of efficacious bacterial reduction than declarative food safety knowledge (i.e., knowledge proffered after formal questioning). This suggests that motivation to prepare safe food was a better indicator of actual behavior than knowledge about food safety per se . Byrd-Bredbenner et al. [ 19 ] point out that adding food safety cues to food packages may be particularly effective given that nearly half of consumers indicate they commonly read cooking instructions on food packages. Moreover, some especially “teachable moments” are after publicized food-borne illness outbreaks or recalls, before major holidays, during the perinatal period, and after being diagnosed with an immune-compromising condition. However, providing food safety information for those at increased risk of poor food-borne illness outcome often is not part of standard clinical practice among health professionals, and role models like athletes do not always demonstrate good food safety practices.

The fourth paper takes the reader from understanding risk perception and risk communication strategies for prevention of food-borne illnesses in homes and restaurants to reviewing mathematical models to help risk managers in making decisions for reducing food-borne disease, in this case the beef industry. Risk assessments have been promoted to address specific issues with the impact of chemical contaminants in the health and environmental fields for over 70 years, but a standardized risk-based food safety management approach was only recommended and adopted by the Codex Alimentarius Commission of the World Health Organization (WHO) in the last 21 years [ 20 ]. This Commission defined risk analysis as comprising risk assessment, risk management, and risk communication, and all types of contaminants were considered, including microbiological ones which have specific modeling challenges in that pathogens can increase and decrease over the production, transport, storage, and preparation of foods. Microbiological risk assessment is a scientific evaluation that aims to provide an estimation of a risk considering the probability and the severity of health effects caused by a bacterial, viral or parasitic hazard in order to support decision-making processes. The Joint FAO/WHO Expert Meetings on Microbiological Risk Assessment (JEMRA) began in 2000 in response to requests from the Codex Alimentarius Commission and FAO and WHO Member Countries and the increasing need for risk-based scientific advice on microbiological food safety issues. Quantitative microbiological risk assessments (QMRAs) aim at determining the existing public health risk associated with biological hazards in a food using mathematical equations to estimate the change of microbial load after each processing step and then to compare the efficiency of different risk reduction measures [ 21 ]. Model inputs are generated by collecting data or soliciting experts. QMRA models comprise four steps: hazard identification, exposure assessment, hazard characterization, and risk characterization. QRMAs enable experts to estimate the risk to which the population may be exposed, evaluate possible risk mitigation strategies, and generate knowledge for the better management of risks associated with contamination events. The assessment involves measuring known microbial pathogens or indicators and running a Monte Carlo simulation throughout different steps in the food chain to estimate the risk of transfer from the food to the consumer. If a dose–response model is available for the microbe, it would be used to estimate the probability of infection.