Locals at the Marienfluss Conservancy in Namibia meet to discuss conservation. Photo courtesy of NACSO/WWF Namibia

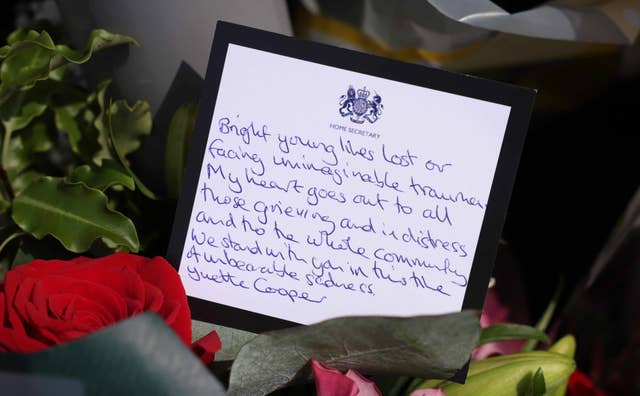

The miracle of the commons

Far from being profoundly destructive, we humans have deep capacities for sharing resources with generosity and foresight.

by Michelle Nijhuis + BIO

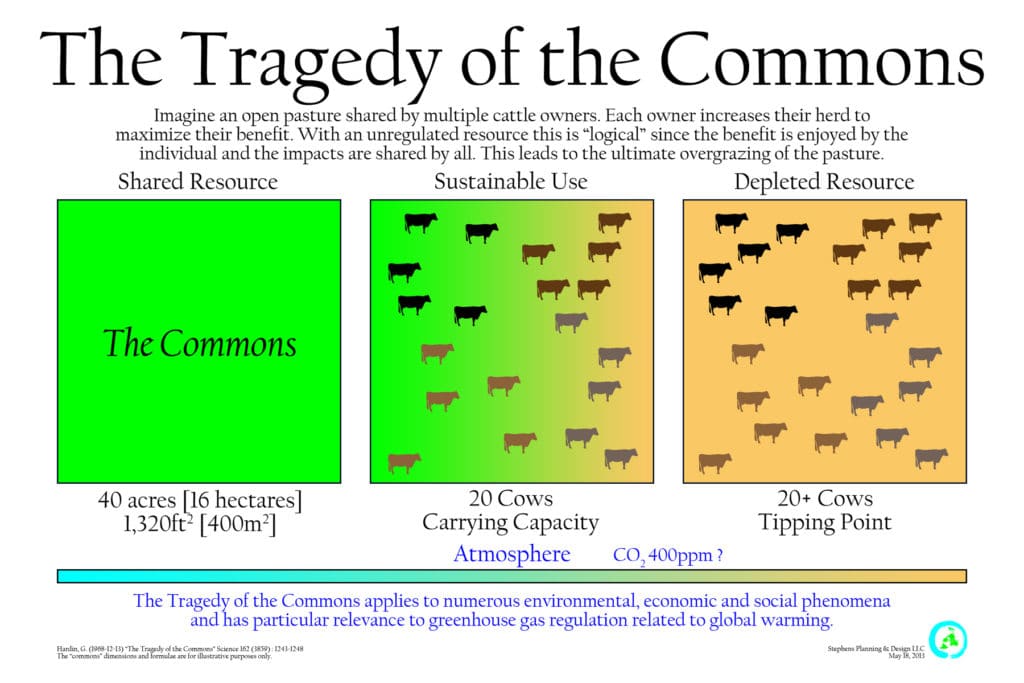

In December 1968, the ecologist and biologist Garrett Hardin had an essay published in the journal Science called ‘The Tragedy of the Commons’. His proposition was simple and unsparing: humans, when left to their own devices, compete with one another for resources until the resources run out. ‘Ruin is the destination toward which all men rush, each pursuing his own best interest,’ he wrote. ‘Freedom in a commons brings ruin to all.’ Hardin’s argument made intuitive sense, and provided a temptingly simple explanation for catastrophes of all kinds – traffic jams, dirty public toilets, species extinction. His essay, widely read and accepted, would become one of the most-cited scientific papers of all time.

Elinor Ostrom, Nobel Laureate in Economics photographed in 2011. Photo by Raveendran/AFP/Getty.

Even before Hardin’s ‘The Tragedy of the Commons’ was published, however, the young political scientist Elinor Ostrom had proven him wrong. While Hardin speculated that the tragedy of the commons could be avoided only through total privatisation or total government control, Ostrom had witnessed groundwater users near her native Los Angeles hammer out a system for sharing their coveted resource. Over the next several decades, as a professor at Indiana University Bloomington, she studied collaborative management systems developed by cattle herders in Switzerland, forest dwellers in Japan, and irrigators in the Philippines. These communities had found ways of both preserving a shared resource – pasture, trees, water – and providing their members with a living. Some had been deftly avoiding the tragedy of the commons for centuries; Ostrom was simply one of the first scientists to pay close attention to their traditions, and analyse how and why they worked.

The features of successful systems, Ostrom and her colleagues found, include clear boundaries (the ‘community’ doing the managing must be well-defined); reliable monitoring of the shared resource; a reasonable balance of costs and benefits for participants; a predictable process for the fast and fair resolution of conflicts; an escalating series of punishments for cheaters; and good relationships between the community and other layers of authority, from household heads to international institutions.

A parliamentary study tour of the conservancies in 2005. Photo courtesy NACSO/WWF Namibia

When it came to humans and their appetites, Hardin assumed that all was predestined. Ostrom showed that all was possible, but nothing was guaranteed. ‘We are neither trapped in inexorable tragedies nor free of moral responsibility,’ she told an audience of fellow political scientists in 1997.

What Hardin had portrayed as a tragedy was, in fact, more like a comedy. While its human participants might be foolish or mistaken, they are rarely evil, and while some choices lead to disaster, others lead to happier outcomes. The story is far less predictable than Hardin thought, and its twists and turns can lead to uncomfortable places. But in those surprises lie the possibilities that Hardin never saw.

Y ou might think that scientists, and the public, would eagerly trade Hardin’s dark speculations about human nature for Ostrom’s sunnier findings about our capabilities. But as I learned while researching and writing my book Beloved Beasts (2021), a history of the modern conservation movement, Ostrom’s conclusions have faced stubborn resistance. During the early years of her career, colleagues criticised her for spending too much time studying the differences among systems and too little time looking for a unifying theory. ‘When someone told you that your work was “too complex”, that was meant as an insult,’ she recalled.

Ostrom insisted that complexity was as important to social science as it was to ecology, and that institutional diversity needed to be protected along with biological diversity. ‘I still get asked, “What is the way of doing something?” There are many, many ways of doing things that work in different environments,’ she told an audience in Nepal in 2010. ‘We have got to get to the point that we can understand complexity, and harness it, and not reject it.’

Her research gained global prominence in 2009, when, aged 76, Ostrom became the first woman to be awarded the Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences. But for a variety of reasons – perhaps because she was a woman in a male-dominated field, or perhaps because her sophisticated work didn’t lend itself to a catchy name – her carefully collected data hasn’t dislodged Hardin’s metaphor from the public imagination.

When Ostrom died in 2012, she was celebrated by her colleagues for her pioneering work, her plainspoken humility, and her steady resistance to what she called ‘panaceas’. She knew from experience how corrosive simple stories could be. Hardin, for his part, seemed bent on making his own ideas as repugnant as possible. Among his proposed solutions to the tragedy of the commons was coercive population control: ‘Freedom to breed is intolerable,’ he wrote in his 1968 essay, and should be countered with ‘mutual coercion, mutually agreed upon’. He feared not only runaway human population growth but the runaway growth of certain populations. What if, he asked in his essay, a religion, race or class ‘adopts overbreeding as a policy to secure its own aggrandisement’? Several years after the publication of ‘The Tragedy of the Commons’, he discouraged the provision of food aid to poorer countries: ‘The less provident and less able will multiply at the expense of the abler and more provident, bringing eventual ruin upon all who share in the commons,’ he predicted. He compared wealthy nations to lifeboats that couldn’t accept more passengers without sinking.

Hardin compared wealthy nations to lifeboats that couldn’t accept more passengers without sinking.

In his later years, Hardin’s racism became more explicit. ‘My position is that this idea of a multiethnic society is a disaster,’ he told an interviewer in 1997. ‘A multiethnic society is insanity. I think we should restrict immigration for that reason.’ Hardin died in 2003, but the nonprofit Southern Poverty Law Center, alert to the longevity of his ideas, maintains his profile in its ‘extremist files’ and classifies him as a white nationalist.

Still, many of those who abhor Hardin’s racist ideas – or would if they were aware of them – are seduced by the simplicity of his tragedy. If academic citation indexes are any guide, the tragedy of the commons remains far better known to scholars than any of Ostrom’s findings. It continues to be taught, uncritically, to high-school students in environmental science courses. It’s used as a justification by those who support severe restrictions on human immigration and reproduction. Even more frequently, it’s casually invoked as an explanation for human failures: even the eminent biologist E O Wilson, in his book Half-Earth (2016), describes the weakness of international climate-change agreements and the ongoing depletion of ocean resources as tragedies of the commons, without making clear that such tragedies can be averted.

Despite the evidence gathered by Ostrom and her colleagues, it seems, many are still all too willing to believe the worst of their fellow humans – to the detriment of conservation efforts worldwide. Like Hardin, many conservationists assume that humans can only be destructive, not constructive, and that meaningful conservation can be achieved only through total privatisation or total government control. Those assumptions, whether conscious or unconscious, close off an entire universe of alternatives.

W hile Ostrom’s ideas are not yet familiar maxims, they haven’t been ignored. In southern Africa in the 1980s, some conservationists recognised that parks and reserves, many created by colonial governments, had divided subsistence hunters and farmers from much of the wildlife that had long sustained them – and which, in some cases, they’d managed as a commons for generations. The resulting lack of local support meant that even the best-patrolled park boundaries were vulnerable to incursions by human neighbours, people unlikely to tolerate – much less protect – the large, sometimes troublesome species that ranged beyond even the largest reserves.

A local warden at the Wuparo Conservancy in Namibia. Photo courtesy NACSO/WWF Namibia

In response, new initiatives attempted to redistribute the burdens and benefits of conservation: the Communal Areas Management Programme for Indigenous Resources (CAMPFIRE) project in Zimbabwe directed revenue from hunting and tourism on communal lands to district councils, incentivising those councils and their communities to control illegal hunting. In neighbouring Zambia, the Administrative Management Design (ADMADE) programme trained local people as wildlife rangers, then transferred some wildlife management responsibilities, and benefits, from the national government to community boards. These and similar efforts became known as community-based conservation.

In 1987, when the South African conservationist Garth Owen-Smith attended a conference on community-based conservation in Zimbabwe, a comment by Harry Chabwela, the director of Zambia’s national parks, left a lasting impression. ‘At this conference we have talked a lot about giving local people this and giving them that, but what has been forgotten is that they also want power,’ Chabwela said. ‘They want a say over the resources that affect their lives. That is more important than money.’

Owen-Smith had already spent years living in Namibia, which was controlled by South Africa and known as South West Africa. When severe drought and an epidemic of illegal hunting threatened livelihoods and wildlife in the territory’s northwestern desert in the early 1980s, Owen-Smith had supported the creation of a system of community game guards. The unarmed guards – many of whom were hunters themselves – were so effective at tracking illegal hunters that, after a few years, the killing of elephants and rhinos in the region stopped completely. Antelope numbers improved so much that Owen-Smith was able to persuade the national conservation department to reopen limited game hunting in the area – a development much appreciated by locals.

Local wardens conduct a game count in Caprivi, Northeastern Namibia. Photo courtesy NACSO/WWF Namibia

Chabwela’s comment about power motivated Owen-Smith to think bigger. When he returned home, he and his partner Margaret Jacobsohn began to talk with community leaders and members about ways of restoring some local authority over wildlife. After Namibia won independence from South Africa in 1990, the new government recruited Jacobsohn and Owen-Smith to survey rural attitudes toward conservation, and the survey confirmed what the two had by then been hearing for years: most people didn’t want the occasionally dangerous species they lived with to be killed or removed – but they did, as Chabwela had suggested, want a say in their management. In 1996, the Namibian National Assembly passed a law that allowed groups of people living on communal land to establish institutions called conservancies. Conservancies would be governed by elected committees, and all members would share the benefits of any tourism or commercial hunting within conservancy boundaries.

Trophy hunters are sometimes directed toward lions and elephants who have become aggressive toward people.

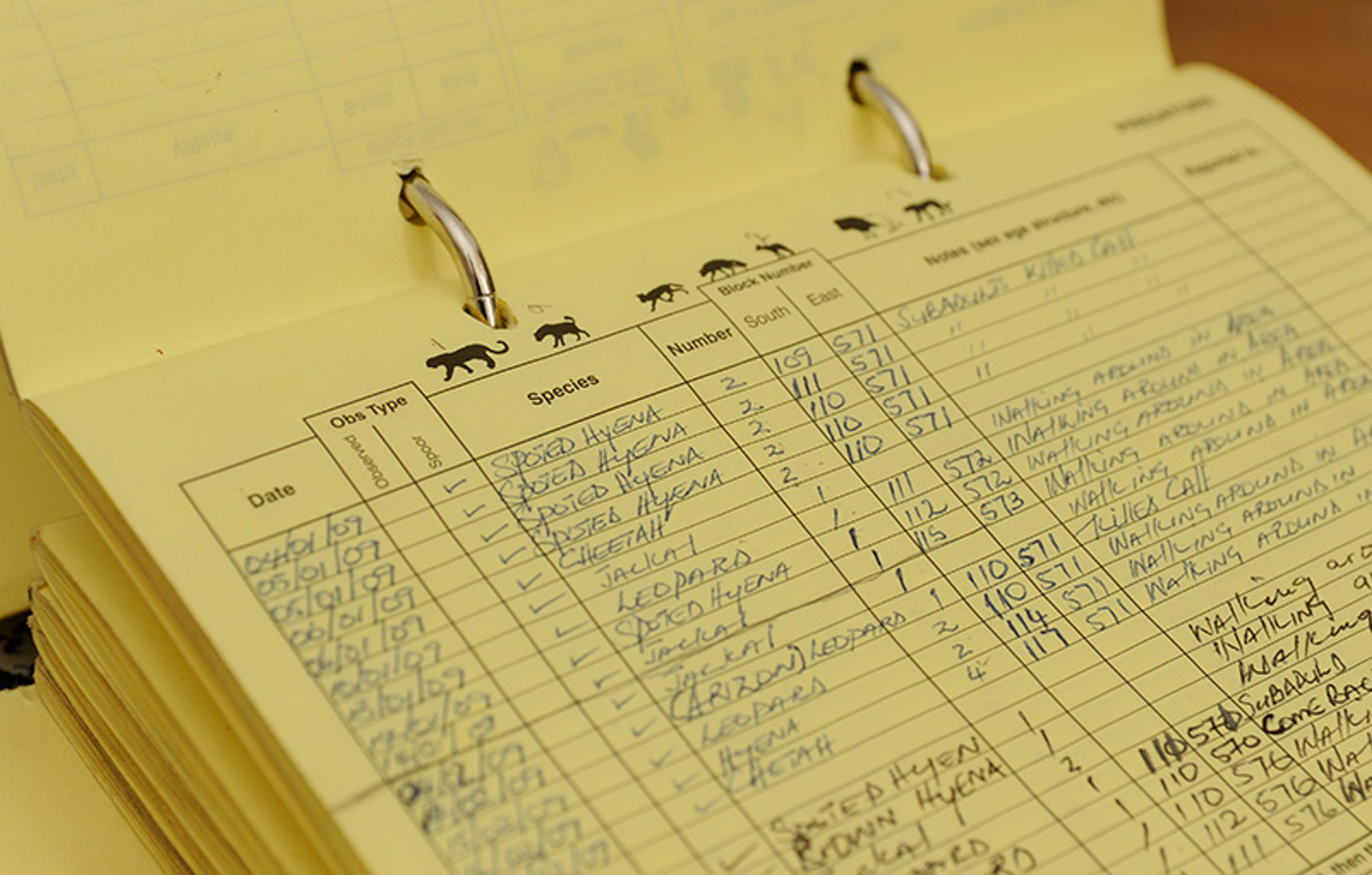

The first conservancies on communal land were formalised in 1998, and there are now more than 80 of them in Namibia. They cover more than 40 million acres of land, and stretch from the northwestern desert to the humid, densely populated Zambezi Region in the northeast. They earn revenue from lodges, campgrounds and guide services, both as partners in joint ventures and as solo operators. They participate in annual surveys of game and wildlife populations and, in cooperation with the national conservation ministry, set quotas for both subsistence and commercial hunting within their boundaries. They employ their own game guards, who are currently fending off a continent-wide wave of rhino poaching driven by Asian demand for powdered rhino horn (a discredited traditional medicine). And, every year, the members of each conservancy assemble to call their governing committees to account.

Detailed recods are made of local wildlife. Photo courtesy NACSO/WWF Namibia

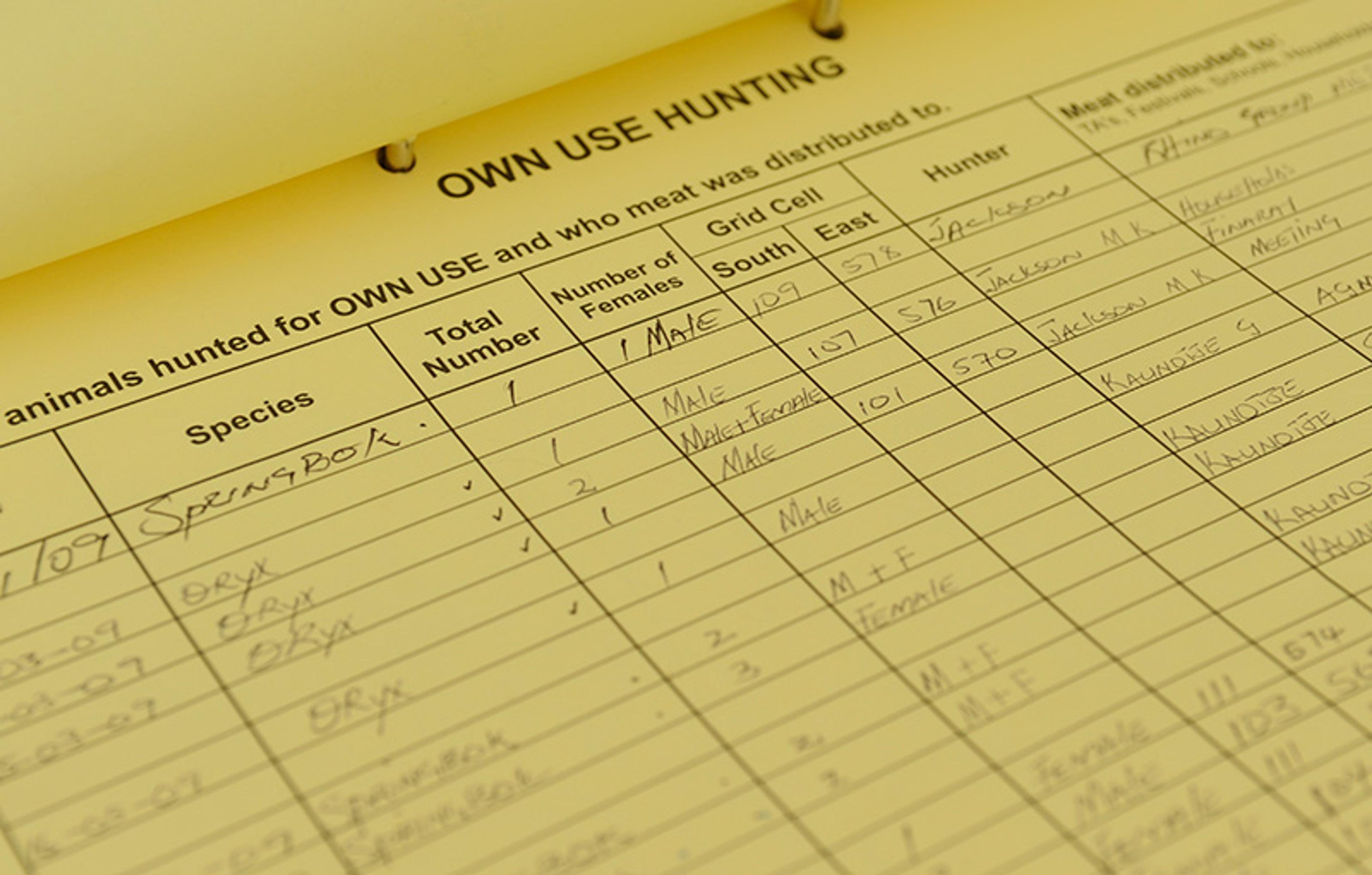

Local hunting quotas are agreed upon. Photo courtesy NACSO/WWF Namibia

In August 2019, I attended the general meeting of Orupembe Conservancy, held in an open-air pavilion on the outskirts of Onjuva, a tiny town hundreds of miles from the nearest gas station, and even further from a paved road. Most of the people at the meeting were semi-nomadic herders, many of whom had travelled long distances from even more isolated corners of the conservancy. (I was present thanks to the expert off-road driving skills of the guide Edison Kasupi, who grew up in nearby Purros Conservancy.) When the Onjuva committee called the meeting to order, there were 95 people seated inside the pavilion, about half of the conservancy members and just enough for a quorum. The chairman Henry Tjambiru commented that the current drought had forced many people to take their herds further afield, preventing them from attending.

Orupembe Conservancy has several sources of income, all relatively modest: a campsite, a small lodge that it co-owns with two other conservancies, and contracts with a handful of hunting guides. (Some conservancies have very little income, and fund their operations with donations from international conservation groups; others, such as the neighbouring Marienfluss Conservancy, have joint venture agreements with upscale lodges that can net more than $100,000 a year in salaries and fees.)

After a review of the year’s earnings, the committee distributed a list of local species and the current hunting quotas for each. Because the drought had worsened since the quotas were set, conservancy members had voluntarily left most of them unfilled. While wildlife surveys earlier in the year had suggested that 75 oryx could be killed without harming the population, for example, only three had been shot so far. The meat from two of those was currently boiling in a nearby row of pots, about to be served for lunch.

The meeting, which lasted several hours, was disrupted by procedural inefficiencies, lively sideline arguments and, at one point, an accusation of petty corruption. But as the sun sank and the meeting came to a ragged end, I realised with surprise that I was exhilarated. During an exceptionally difficult year, these conservancy members had taken the trouble to travel to the meeting, consider the long-term future of other species, and recommit themselves to ensuring it.

I n reviving the commons, the Namibian conservancies have revived the relationships between people and wildlife – and the results, as Ostrom would be unsurprised to learn, are complex. Where parks and reserves separate land into clearly defined categories, community-based conservation proposes that land can be simultaneously protected and utilised – through the cooperative efforts of the people who live on it. It’s a profound challenge to Hardin’s assumptions, and while some of its outcomes are easy to applaud – the recovery of elephants and rhinos, the arrival of new jobs – others make outsiders squirm.

A vulnerable rhino is relocated. Photo courtesy NACSO/WWF Namibia

John Kasaona, who grew up in northwestern Namibia and, as a boy, watched Owen-Smith and his father set out on game-guard patrols, is now the executive director of Integrated Rural Development and Nature Conservation, a nonprofit organisation that provides technical support to the conservancies. When he travels overseas to talk about the accomplishments of the Namibian conservancy system, he mentions only briefly, if at all, that its success depends in part on income from trophy hunters – tourists who pay for the privilege of shooting an animal for sport, and who in some cases keep hides or horns for display. For many conservancies, trophy hunting is not only a source of income but a tool for preserving the peace between humans and other species, since trophy hunters are sometimes directed toward individual lions or elephants who have become aggressive toward people.

Kasaona is well aware of the images that trophy hunting conjures in his listeners’ minds: Theodore Roosevelt standing next to a fallen elephant, dwarfed by the carcass and its upturned tusks; Eric Trump grinning as he hefts the limp body of a leopard, his brother Don Jr beside him; the Zimbabwean lion named Cecil, whose illegal killing by a dentist from Minnesota during a guided hunt in 2015 caused a global outcry. For some in North America and Europe, trophy hunting in Africa has come to symbolise human sins against other species.

In 2017, after Kasaona spoke at a Smithsonian Institution conference in Washington, DC, a young woman stood to speak at the audience microphone. ‘I think that some pieces were missing from the presentation,’ she began. Kasaona had not shown images of the animals slain by trophy hunters, she said. He had neglected to mention that the lion or elephant spotted by a visiting family on safari might be killed the next day. Kasaona, at the podium, acknowledged the international controversy over trophy hunting, but said that regulated commercial hunts remained an important source of revenue for the Namibian conservancies. There was more to say, but the session was over, and any further discussion was washed away by chatter.

Even in the darkest times, Ostrom’s work reminds us that the future is unpredictable and full of opportunity.

More than two years later, I met up with Kasaona in the town of Swakopmund, about halfway down the Namibian coast. We talked over generous plates of springbok curry at the colonial-era Hansa Hotel, where German is spoken more frequently than English, and both are far more common than any of Namibia’s 20-plus Indigenous languages and dialects.

I asked Kasaona to finish answering his questioner at the Smithsonian conference. ‘People say: “I don’t like what they’re doing to animals,” but most of them wouldn’t want to live next to a lion that could harm their family,’ he said. The majority of tourists who hunt for sport in Namibia pursue more common species such as springbok, whose hunting is permitted through the conservancy quota system. In the case of globally threatened species, the number of animals (if any) that can be shot each year is set by the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES). In 2004, the parties to the convention approved applications by Namibia and South Africa to allow limited hunting of black rhinos, determining that the population had recovered to the point that five male rhinos could be shot in each country each year. In Namibia, the national conservation ministry chooses which rhinos will be hunted – usually older animals that have become aggressive or territorial – and issues permits for the hunts. The permit fee is deposited in a national conservation trust fund, and in one recent case a hunter paid $400,000 to shoot a single male rhino, far more than most conservancies earn in a year.

The trophy-hunting system in Namibia isn’t perfect, Kasaona acknowledges – there are cases where hunters have killed the wrong animal – but over the long term, he said, it benefits both the conservancies and the species in question by reducing conflicts between people and wildlife. When international conservation groups promise to regulate and censure trophy hunting out of existence, Kasaona hears what he calls ‘another kind of colonisation’ – a violation of the local authority that he and others have spent decades building up, and a threat to the revenue it depends on. ‘What do they say to the people whose livelihood depends on what they are trying to ban?’ he says.

Global restrictions on trophy hunting, Kasaona argues, are a simplistic response to a complex situation – what Ostrom might call a panacea. Not all countries are alike; not all conservancies are alike; not all conservancy members are alike; not even all trophy hunters are alike. And a few individual lions and elephants are far more dangerous than others, as those who have lost loved ones and livelihoods to rogue animals can attest.

While those viral images of trophy hunters with carcasses might all seem to say the same thing, they don’t. Some, surely, are symbols of corruption or needless violence. But, in the best cases, they’re examples of sustainable utilisation: colonial nostalgia, harnessed by the formerly colonised to further multispecies survival.

O strom’s principles of commons management now underlie not only the Namibian conservancy system but hundreds of similar efforts throughout the world. Many have revived and adapted conservation practices developed centuries ago, developing new rules suited to current circumstances. Their creators cooperate in the management of coral reefs in Fiji, highland forests in Cameroon, fisheries in Bangladesh, oyster farms in Brazil, community gardens in Germany, elephants in Cambodia, and wetlands in Madagascar. They operate in thinly populated deserts, crowded river valleys, and abandoned urban spaces.

While conservation almost always carries at least some short-term costs, researchers have found that many community-based conservation projects reduce those costs and, over time, deliver significant benefits to their human participants, tangible and intangible alike. And while community-based conservation began as a reaction to top-down conservation strategies, it can operate in parallel with large parks and reserves – and even foster their creation. In northwestern Namibia, two neighbouring conservancies have proposed to establish a ‘people’s park’ where livestock would be excluded and tourist numbers would be limited by a permit system, allowing lions and other large predators to more easily avoid conflicts with humans. Should the national legislature approve the conservancies’ proposal, the region could serve as a core habitat from which large carnivores can range in relative safety – since the region’s biological diversity is now protected not only by law, but by supportive human neighbours.

Community-based conservation can’t solve everything, and it doesn’t always succeed in protecting the commons. In many cases, national governments don’t recognise the longstanding land claims of Indigenous and other rural communities, creating uncertainty that interferes with community efforts to manage for the long term. Even well-established systems are vulnerable to internal conflict, and to external pressures ranging from drought to war to global market forces. As Ostrom often reminded her audiences, any strategy can succeed or fail. Community-based conservation is distinctive because many societies have only begun to understand – or remember – its potential. ‘What we have ignored is what citizens can do,’ she said.

At Indiana, Ostrom and her husband Vincent, also a political scientist, founded the Workshop in Political Theory and Policy Analysis, affectionately known as ‘The Workshop’ to the researchers who continue to gather there. Current students of commons management struggle, as Ostrom did, with the difficulty of managing large-scale resource problems such as air pollution at the community level. They wrestle with the implications of her findings for the digital landscape, where the veneration of open access often collides with Ostrom’s definition of the commons as a boundaried, regulated space. And despite what one researcher in 2011 dubbed ‘Ostrom’s Law’ – that whatever works in practice can work in theory – even Ostrom’s admirers sometimes echo her earliest critics, lamenting that the field lacks an overarching theory.

The challenge of understanding the complexity of all species continues, as does the challenge of seeing possibility in what so often looks like a collective tragedy. But even in the darkest times, Ostrom’s work can remind us that the future is deliciously unpredictable, and full of opportunities for us to stumble away from the edge.

This original essay draws on the book ‘Beloved Beasts: Fighting for Life in an Age of Extinction’ (2021) by Michelle Nijhuis, published by W W Norton & Co.

Knowledge is often a matter of discovery. But when the nature of an enquiry itself is at question, it is an act of creation

Céline Henne

Nature and landscape

Land loneliness

To survive, we are asked to forget that our lands and bodies are being violated, policed, ripped up, silenced, sacrificed

History of ideas

All that we are

The philosophy of personalism inspired Martin Luther King’s dream of a better world. We still need its hopeful ideas today

Bennett Gilbert

A novel kind of music

So-called ‘classical’ music was as revolutionary as the modern novel in its storytelling, harmony and depth

Joel Sandelson

Psychiatry and psychotherapy

Decolonising psychology

At times complicit in racism and oppression, psychology has also been a fertile ground for radical and liberatory thought

Rami Gabriel

Meaning and the good life

Beyond authenticity

In her final unfinished work, Hannah Arendt mounted an incisive critique of the idea that we are in search of our true selves

Samantha Rose Hill

The Tragedy of the Commons

29 pages • 58 minutes read

A modern alternative to SparkNotes and CliffsNotes, SuperSummary offers high-quality Study Guides with detailed chapter summaries and analysis of major themes, characters, and more.

Essay Analysis

Key Figures

Index of Terms

Literary Devices

Important Quotes

Essay Topics

Discussion Questions

Summary and Study Guide

Summary: “the tragedy of the commons”.

Published in 1968, the essay “The Tragedy of the Commons,” by ecologist Garrett James Hardin , argues that human overpopulation will stress ecosystems beyond their limits and cause a resource catastrophe. The essay has greatly influenced environmentalists.

Hardin was a politically controversial, award-winning science writer who taught ecology at the University of California at Santa Barbara for over 30 years. Critics on both sides of the political spectrum have resented not only some of his proposed solutions to overpopulation but also parts of his rationale; Hardin was a utilitarian who believed the most moral course of action is that which maximizes the wellbeing of the greatest number of people—and this principle took precedence over the idea of natural or universal rights. Hardin therefore tended to favor anything that might reduce the possibility of overpopulation, from abortion to limits on immigration. Hardin has fallen into disfavor in many academic circles due to his eugenicist sympathies, beliefs in racial intelligence disparities, and stigmatizing remarks on poverty—but despite the pall this record casts, Hardin’s fusion of utilitarian pragmatism and scientific stringency left a formidable ecological legacy.

The opening paragraphs of “The Tragedy of the Commons” serve as an introduction that warns that technical solutions to big problems sometimes make those problems worse. He cites the Cold War development of nuclear weapons, each advance of which brought more danger than safety to the world. Solutions to such dilemmas require advances in human ethics rather than improvements in technology. This principle applies also to the problem of human overpopulation: As technology advances, societies increase in size and begin to overtax their environments.

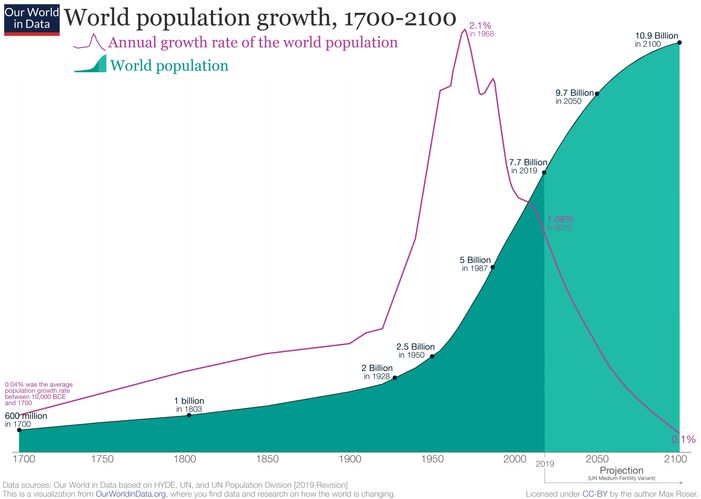

Section 2, “What Shall We Maximize?” asks whether human population can grow indefinitely. The author answers that Earth’s resources are finite, and that population growth must therefore hover around zero or a disaster becomes inevitable. Economist and clergyman Thomas Malthus warned that continuous growth becomes “geometric,” or exponential, rising faster and faster until it outstrips all resources. Continuously growing populations will eventually require continuously increasing sacrifices, until utilitarian philosopher Jeremy Bentham’s hope for “the greatest good for the greatest number” becomes impossible (Section 2, Paragraph 2). Even an endless source of energy would likely be insufficient for an indefinitely increasing population.

People will have to decide what they’ll sacrifice for protection against catastrophic overgrowth. So far, though, no civilization has solved the problem of population growth, and already the fastest-growing countries often are the most resource-stressed.

Economist Adam Smith in 1776 popularized the idea of the “invisible hand” that permits individual workers, laboring strictly for private gain, to unintentionally create value for all. This idea, however, when allowed to run free in the realm of reproduction, leads to ever-increasing populations and worsening strains on the natural world and its resources. The freedom to reproduce, argues Hardin, may have to be restricted.

Section 3, “Tragedy of Freedom in a Commons ,” describes how resources get overused as a population increases. Herders who use a common field, or “commons,” to graze their animals will, under stable conditions, add to their herds until the field is at capacity. At that point, adding an additional animal will still benefit the herder, and the resulting overgrazing will be shared by everyone and not solely by that herder. This leads to herders adding to their own herds until the common area, exhausted by overuse, can no longer feed the herds.

Tragedy is the inevitable unfolding of fate, and the logic of the herders leads inevitably to a catastrophe in the commonly used field. This logic also causes, for example, overgrazing on federal land in the western US, overfishing in the oceans, and overcrowding in America’s national parks.

Section 4, “Pollution,” describes another exploitation of the commons. It’s very cheap to dump pollutants into the environment instead of purifying them, and the polluting effects are small for the dumper. Over time, though, as everyone dumps pollutants, the effects accumulate and return to poison all within the environment. Even then, it’s still economically efficient to pollute: Each time, the cost of additional pollution is outweighed by the savings from dumping the effluents.

In Section 5, “How To Legislate Temperance?” the author asserts that the ethics of pollution depend on the situation: “[T]he morality of an act is a function of the state of the system at the time it is performed” (Section 5, Paragraph 1). Thus, a single American frontiersman in 1818 who kills a bison merely for its tongue had no discernible effect on the millions of buffalo around him, whereas such an act in 1968, when the number of bison had dwindled to a few thousand, would be considered appalling.

Attempts to judge the morality of a particular environmental action can backfire. Photos of a killed elephant or blazing grassland, without context , may mislead viewers; prohibitions can become unreasonable; bureaucrats who enforce the laws may become corrupted. Laws must be carefully thought out and bureaucrats given the correct incentives.

Section 6, “Freedom to Breed Is Intolerable,” argues that, in a state of nature, overbreeding by animals usually leads to fewer offspring in total, but the modern human welfare state rewards excessively large human families. The United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights of 1967 maintains that the total number of children in a family is the decision of that family. Given problems of overpopulation already present in the world, this covenant becomes a “tragic ideal.”

Section 7 is titled “Conscience Is Self-Eliminating.” The author presents evidence that conscience is an insufficient motivation for change. Citing Darwinian logic, Hardin maintains that appeals to parents to limit their family size for the good of humanity results in larger families: Those who limit their size get outbred by those who don’t, until most or all of the descendants tend to have larger, more selfish families. “To make such an appeal is to set up a selective system that works toward the elimination of conscience from the race” (Section 7, Paragraph 4).

In Section 8, “Pathogenic Effects of Conscience,” Hardin theorizes that people who are told to limit their own reproduction face a “double bind” that damns them if they agree and ostracizes them if they refuse. Such appeals to conscience, popular among political leaders, generally don’t lead to improvements but do cause a wasteful epidemic of anxiety.

Section 9, “Mutual Coercion Mutually Agreed Upon,” suggests a better approach whereby groups come to a consensus on which behaviors deserve punishment. Punishment is a form of coercion that no one likes, but it can be tolerated for its beneficial effects overall. As for the commons, the classic alternative is private property and inheritance. This system, Hardin admits, can be problematic—”An idiot can inherit millions” (Section 9, Paragraph 5)—but it’s better than the destructive misuse of a commons.

The author observes that reform sometimes gets stymied by those who believe any changes must be perfect, as if the current system already is perfect. In fact, all systems have flaws, including the old ways, and a rational comparison of old and new methods can help to determine the best choice.

The tenth and final Section, “Recognition of Necessity,” notes that the commons, once spaciously vast in a world of few people, becomes overwhelmed on a planet with billions of humans. Most resources and environments commonly held today are stressed by pollution and overuse; restrictions on such misuse will curtail individual freedoms but also resolve environmental and resource problems that, in themselves, constrain human action. The main liberty to curtail, then, is the freedom to reproduce at will. That is the only way to prevent an overpopulation disaster.

Featured Collections

Business & Economics

View Collection

Science & Nature

- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- Games & Quizzes

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

- What are the abiotic and biotic components of the biosphere?

tragedy of the commons

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

- UNESCO-EOLSS - "The Tragedy of the Commons" by Garrett Hardin, 1968

- The University of Chicago - Department of Mathematics - The Tragedy of the Commons

- Pennsylvania State University - College of Earth and Mineral Sciences - The Tragedy of the Commons

- PressBooks - Tragedy of the commons

- Academia - Tragedy of the Commons

- Engineering LibreTexts - Tragedy of the Commons

- Earth.Org - What is the ‘Tragedy of the Commons’?

- The Library of Economics and Liberty - Tragedy of the Commons

tragedy of the commons , concept highlighting the conflict between individual and collective rationality .

The idea of the tragedy of the commons was made popular by the American ecologist Garrett Hardin , who used the analogy of ranchers grazing their animals on a common field. When the field is not over capacity, ranchers may graze their animals with few limitations. However, the rational rancher will seek to add livestock, thereby increasing profits. Thinking logically but not collectively, the benefits of adding animals adhere to the rancher alone, while the costs are shared. The tragedy is that ultimately no rancher will be able to graze the field, due to overconsumption. This scenario is played out on a daily basis in numerous instances, having grave consequences for the world’s resources.

(Read Steven Pinker’s Britannica entry on rationality.)

It is commonly recognized that one of the primary roles of government at the local, state, national, and international levels is to define and manage shared resources. However, there are a number of practical problems associated with this. Management inside clear political boundaries is a relatively straightforward task, but more problematic are resources shared across jurisdictions. For example, neighbouring cities may seek to maximize their benefits by competing for industry, but they may minimize their costs by pushing residents outside their jurisdictions. Another dimension is added at the international level when states are not bound by a common authority and may view restrictions on resource extraction as a threat to their sovereignty . Additional difficulties arise when resources cannot be divided or are interrelated, such as in whale hunting treaties when the fishing of the whales’ food source is separately regulated.

The mechanisms to resolve these tragedies are part of a larger set of theories dealing with social dilemmas in fields such as mathematics , economics , sociology , urban planning , and environmental sciences . In these arenas, scholars have identified and structured a number of tentative solutions, such as enclosing the commons by establishing property rights , regulating through government intervention, or developing strategies to trigger collective behaviour . The American political scientist Elinor Ostrom , who was a cowinner of the 2009 Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences, argued that these strategies generally deal with problems of commitment and problems of mutual monitoring.

As the world’s population rises and demands more access to resources, the issues associated with the commons become more severe. Ultimately, this may test the role and practicality of nation-states, leading to a redefinition of international governance . Among other important questions to consider is the proper role of supranational governments, such as the United Nations and the World Trade Organization . As resources become more limited, some argue, managing the commons may have neither a technical nor a political solution. This, indeed, may be the ultimate tragedy.

- Liberty Fund

- Adam Smith Works

- Law & Liberty

- Browse by Author

- Browse by Topic

- Browse by Date

- Search EconLog

- Latest Episodes

- Browse by Guest

- Browse by Category

- Browse Extras

- Search EconTalk

- Latest Articles

- Liberty Classics

- Search Articles

- Books by Date

- Books by Author

- Search Books

- Browse by Title

- Biographies

- Search Encyclopedia

- #ECONLIBREADS

- College Topics

- High School Topics

- Subscribe to QuickPicks

- Search Guides

- Search Videos

- Library of Law & Liberty

- Home /

ECONLIB CEE

Tragedy of the Commons

By garrett hardin.

By Garrett Hardin,

I n 1974 the general public got a graphic illustration of the “tragedy of the commons” in satellite photos of the earth. Pictures of northern Africa showed an irregular dark patch 390 square miles in area. Ground-level investigation revealed a fenced area inside of which there was plenty of grass. Outside, the ground cover had been devastated.

The explanation was simple. The fenced area was private property, subdivided into five portions. Each year the owners moved their animals to a new section. Fallow periods of four years gave the pastures time to recover from the grazing. The owners did this because they had an incentive to take care of their land. But no one owned the land outside the ranch. It was open to nomads and their herds. Though knowing nothing of Karl Marx , the herdsmen followed his famous advice of 1875: “To each according to his needs.” Their needs were uncontrolled and grew with the increase in the number of animals. But supply was governed by nature and decreased drastically during the drought of the early 1970s. The herds exceeded the natural “carrying capacity” of their environment, soil was compacted and eroded, and “weedy” plants, unfit for cattle consumption, replaced good plants. Many cattle died, and so did humans.

The rational explanation for such ruin was given more than 170 years ago. In 1832 William Forster Lloyd, a political economist at Oxford University, looking at the recurring devastation of common (i.e., not privately owned) pastures in England, asked: “Why are the cattle on a common so puny and stunted? Why is the common itself so bare-worn, and cropped so differently from the adjoining inclosures?”

Lloyd’s answer assumed that each human exploiter of the common was guided by self-interest. At the point when the carrying capacity of the commons was fully reached, a herdsman might ask himself, “Should I add another animal to my herd?” Because the herdsman owned his animals, the gain of so doing would come solely to him. But the loss incurred by overloading the pasture would be “commonized” among all the herdsmen. Because the privatized gain would exceed his share of the commonized loss, a self-seeking herdsman would add another animal to his herd. And another. And reasoning in the same way, so would all the other herdsmen. Ultimately, the common property would be ruined.

Even when herdsmen understand the long-run consequences of their actions, they generally are powerless to prevent such damage without some coercive means of controlling the actions of each individual. Idealists may appeal to individuals caught in such a system, asking them to let the long-term effects govern their actions. But each individual must first survive in the short run. If all decision makers were unselfish and idealistic calculators, a distribution governed by the rule “to each according to his needs” might work. But such is not our world. As James Madison said in 1788, “If men were angels, no Government would be necessary” ( Federalist, no. 51). That is, if all men were angels. But in a world in which all resources are limited, a single nonangel in the commons spoils the environment for all.

The spoilage process comes in two stages. First, the non-angel gains from his “competitive advantage” (pursuing his own interest at the expense of others) over the angels. Then, as the once noble angels realize that they are losing out, some of them renounce their angelic behavior. They try to get their share out of the commons before competitors do. In other words, every workable distribution system must meet the challenge of human self-interest. An unmanaged commons in a world of limited material wealth and unlimited desires inevitably ends in ruin. Inevitability justifies the epithet “tragedy,” which I introduced in 1968.

Whenever a distribution system malfunctions, we should be on the lookout for some sort of commons. Fish populations in the oceans have been decimated because people have interpreted the “freedom of the seas” to include an unlimited right to fish them. The fish were, in effect, a commons. In the 1970s, nations began to assert their sole right to fish out to two hundred miles from shore (instead of the traditional three miles). But these exclusive rights did not eliminate the problem of the commons. They merely restricted the commons to individual nations. Each nation still has the problem of allocating fishing rights among its own people on a noncommonized basis. If each government allowed ownership of fish within a given area, so that an owner could sue those who encroach on his fish, owners would have an incentive to refrain from overfishing. But governments do not do that. Instead, they often estimate the maximum sustainable yield and then restrict fishing either to a fixed number of days or to a fixed aggregate catch. Both systems result in a vast overinvestment in fishing boats and equipment as individual fishermen compete to catch fish quickly.

Some of the common pastures of old England were protected from ruin by the tradition of stinting—limiting each herdsman to a fixed number of animals (not necessarily the same for all). Such cases are spoken of as “managed commons,” which is the logical equivalent of socialism . Viewed this way, socialism may be good or bad, depending on the quality of the management. As with all things human, there is no guarantee of permanent excellence. The old Roman warning must be kept constantly in mind: Quis custodiet ipsos custodes? (Who shall watch the watchers themselves?)

Under special circumstances even an unmanaged commons may work well. The principal requirement is that there be no scarcity of goods. Early frontiersmen in the American colonies killed as much game as they wanted without endangering the supply, the multiplication of which kept pace with their needs. But as the human population grew larger, hunting and trapping had to be managed. Thus, the ratio of supply to demand is critical.

The scale of the commons (the number of people using it) also is important, as an examination of Hutterite communities reveals. These devoutly religious people in the northwestern United States live by Marx’s formula: “From each according to his ability, to each according to his needs.” (They give no credit to Marx, however; similar language can be found several places in the Bible.) At first glance Hutterite colonies appear to be truly unmanaged commons. But appearances are deceiving. The number of people included in the decision unit is crucial. As the size of a colony approaches 150, individual Hutterites begin to undercontribute from their abilities and overdemand for their needs. The experience of Hutterite communities indicates that below 150 people, the distribution system can be managed by shame; above that approximate number, shame loses its effectiveness.

If any group could make a commonistic system work, an earnest religious community like the Hutterites should be able to. But numbers are the nemesis. In Madison’s terms, nonangelic members then corrupt the angelic. Whenever size alters the properties of a system, engineers speak of a “scale effect.” A scale effect, based on human psychology, limits the workability of commonistic systems.

Even when the shortcomings of the commons are understood, areas remain in which reform is difficult. No one owns the Earth’s atmosphere. Therefore, it is treated as a common dump into which everyone may discharge wastes. Among the unwanted consequences of this behavior are acid rain, the greenhouse effect, and the erosion of the Earth’s protective ozone layer. Industries and even nations are apt to regard the cleansing of industrial discharges as prohibitively expensive. The oceans are also treated as a common dump. Yet continuing to defend the freedom to pollute will ultimately lead to ruin for all. Nations are just beginning to evolve controls to limit this damage.

The tragedy of the commons also arose in the savings and loan (S&L) crisis. The federal government created this tragedy by forming the Federal Savings and Loan Insurance Corporation (FSLIC). The FSLIC relieved S&L depositors of worry about their money by guaranteeing that it would use taxpayers’ money to repay them if an S&L went broke. In effect, the government made the taxpayers’ money into a commons that S&Ls and their depositors could exploit. S&Ls had the incentive to make overly risky investments, and depositors did not have to care because they did not bear the cost. This, combined with faltering federal surveillance of the S&Ls, led to widespread failures. The losses were “commonized” among the nation’s taxpayers, with serious consequences to the federal budget (see savings and loan crisis ).

Congestion on public roads that do not charge tolls is another example of a government-created tragedy of the commons. If roads were privately owned, owners would charge tolls and people would take the toll into account in deciding whether to use them. Owners of private roads would probably also engage in what is called peak-load pricing, charging higher prices during times of peak demand and lower prices at other times. But because governments own roads that they finance with tax dollars, they normally do not charge tolls. The government makes roads into a commons. The result is congestion.

About the Author

The late Garrett Hardin was professor emeritus of human ecology at the University of California at Santa Barbara. He died in 2003.

Further Reading

Related content, terry anderson on the environment and property rights.

TED is supported by ads and partners 00:00

What is the tragedy of the commons?

- climate change

- sustainability

- anthropology

- natural resources

- Business Essentials

- Leadership & Management

- Credential of Leadership, Impact, and Management in Business (CLIMB)

- Entrepreneurship & Innovation

- Digital Transformation

- Finance & Accounting

- Business in Society

- For Organizations

- Support Portal

- Media Coverage

- Founding Donors

- Leadership Team

- Harvard Business School →

- HBS Online →

- Business Insights →

Business Insights

Harvard Business School Online's Business Insights Blog provides the career insights you need to achieve your goals and gain confidence in your business skills.

- Career Development

- Communication

- Decision-Making

- Earning Your MBA

- Negotiation

- News & Events

- Productivity

- Staff Spotlight

- Student Profiles

- Work-Life Balance

- AI Essentials for Business

- Alternative Investments

- Business Analytics

- Business Strategy

- Business and Climate Change

- Creating Brand Value

- Design Thinking and Innovation

- Digital Marketing Strategy

- Disruptive Strategy

- Economics for Managers

- Entrepreneurship Essentials

- Financial Accounting

- Global Business

- Launching Tech Ventures

- Leadership Principles

- Leadership, Ethics, and Corporate Accountability

- Leading Change and Organizational Renewal

- Leading with Finance

- Management Essentials

- Negotiation Mastery

- Organizational Leadership

- Power and Influence for Positive Impact

- Strategy Execution

- Sustainable Business Strategy

- Sustainable Investing

- Winning with Digital Platforms

Tragedy of the Commons: What It Is & 5 Examples

- 06 Feb 2019

Have you ever considered the environmental impact of the everyday items you use?

While some products might seem harmless, their production and consumption can often threaten ecosystems and deplete natural resources. This phenomenon is known as the tragedy of the commons , and understanding it is crucial if you want to make sustainable choices in your personal and professional practices.

Access your free e-book today.

What Is the Tragedy of the Commons?

The tragedy of the commons refers to a situation in which individuals with access to a public resource—also called a common—act in their own interest and, in doing so, ultimately deplete the resource.

This economic theory was conceptualized in 1833 by British writer William Forster Lloyd. In 1968, the term “tragedy of the commons” was used for the first time by Garret Hardin in Science Magazine .

This theory explains individuals’ tendency to make decisions based on their personal needs, regardless of the negative impact it may have on others. In some cases, an individual’s belief that others won’t act in the best interest of the group can lead them to justify selfish behavior. Potential overuse of a common-pool resource—a hybrid between a public and private good—can also influence individuals to act with their short-term interest in mind, resulting in the use of an unsustainable product and disregard of the harm it could cause to the environment or the general public.

It’s helpful for firms and individuals to understand the tragedy of the commons so they can make more sustainable and environmentally friendly choices. Here are five real-world examples of the tragedy of the commons and an exploration of the solution to this problem.

Check out our video on the tragedy of the commons below, and subscribe to our YouTube channel for more explainer content!

5 Tragedy of the Commons Examples

1. coffee consumption.

While a simple cup of coffee might seem harmless, coffee consumption is a prime example of the tragedy of the commons.

According to Statista , about 73 percent of consumers report drinking coffee daily, and four percent have coffee once a week. This overconsumption has led to significant environmental impacts.

Coffee plants are a naturally occurring shared resource, but overconsumption has led to habitat loss, endangering 60 percent of the plants' species —including the most commonly brewed Arabica coffee. Sustainable business practices in agriculture are essential to effectively mitigating negative environmental impacts.

2. Overfishing

As the global population continues to rise, the demand for food increases. However, overhunting and overfishing threaten to push many species into extinction.

For example, overfishing the Pacific bluefin tuna has reduced its population to approximately three percent of its original numbers —posing significant risks to marine ecosystems.

The current state of fish stocks illustrates another risk. According to the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization , approximately 34 percent of the world's fish stocks are overfished, while 60 percent are fully exploited.

Addressing this issue involves promoting sustainable business practices in fishing and enhancing resource management to prevent environmental degradation.

Related: What Does "Sustainability" Mean in Business?

3. Fast Fashion

Overproduction by fashion brands has created extreme product surplus, to the point that luxury brand Burberry burned $37.8 million worth of its 2018 season’s leftovers to avoid offering a discount on unsold wares.

Furthermore, as new trends emerge rapidly within social networks and social media, consumers are constantly purchasing new clothing items and disposing of old, out-of-trend items that end up in landfills and contribute to pollution.

4. Traffic Congestion

Traffic congestion is one of the best-known modern examples of the tragedy of the commons. According to a study by the Harvard School of Public Health , air pollution from traffic congestion in urban areas contributes to more than 2,200 premature deaths annually in the United States alone.

As more people decide that roads and highways are the fastest way to travel to work, more cars end up on the roads, ultimately slowing down traffic and polluting the air.

5. Groundwater Use

In the United States, groundwater is the source of drinking water for about half the population, and roughly 50 billion gallons are used daily for agriculture. Because of this, the groundwater supply is decreasing faster than it can be replenished. In drought-prone areas, the risk of water shortage is high, and restrictions are often put in place to mitigate it. Yet, some individuals ignore water restrictions, and the supply becomes smaller for everyone.

Related: Listen to Professor Reinhardt discuss climate change and the tragedy of the commons on The Parlor Room podcast , or watch the episode on YouTube .

Ways to Prevent the Tragedy of the Commons

How would you react to discovering that your consumption habits are depleting natural resources? You have two primary options: finding alternative, sustainable products and preventing overconsumption. Preventing the tragedy of the commons means making conscious choices and supporting sustainability in business.

Find Alternative and Sustainable Products

To drive change and avoid the tragedy of the commons, it’s important to boycott the products or brands causing the alleged harm and search for alternatives. Finding sustainable options, rather than carrying on with what Sustainable Business Strategy Professor Rebecca Henderson calls “business as usual,” directly addresses your consumption habits' impact. Unfortunately, this response hasn't grown in popularity since many consumers feel boycotting a product won’t have a large enough impact to make a difference.

The tragedy of the commons shows us how, without some sort of regulation or public transparency of choices and actions associated with public goods, individuals have no incentive to refrain from taking too much. In fact, individuals may even have a “use it or lose it” mentality; if they’re aware of the inevitability that the good itself will be depleted, they may think, “I better get my share while I still can.”

Prevent Overconsumption

You’ve likely encountered examples of the tragedy of the commons in your everyday life; these hypothetical scenarios can offer insight into how to prevent the overconsumption of resources. Consider how you’d respond in the following scenarios:

- If everyone in your community abides by the town’s lawn-watering regulations, you're more likely to follow them as well. Who wants a bright green lawn while the rest of the town's lawns are brown?

- No one wants to pay a premium for something they’ll likely throw away or use as a trash bag. Charging for grocery bags raises the stakes because it involves the customer’s bottom line. Chances are, this change will lead you to keep reusable bags in your car, just in case you need to stop at the grocery store on the way home.

These examples show how, when faced with a public good, individuals can be motivated to cooperate through monetary or moral incentives or penalties. What’s fascinating is that this also holds true on a larger scale.

Remember the previous example of luxury fashion brands burning surplus clothing? Well, Burberry—having heard its customers’ reactions to the burning of inventory, regardless of how sustainably its products were disposed of—has since pledged to stop burning clothes and using real fur.

Developing a Sustainable Mindset

It’s easy for individuals and organizations to fall victim to the tragedy of the commons. However, it doesn’t have to be this way. By developing a more sustainable mindset , you can become better aware of the long-term impact that your short-term choices have on the environment in your personal life and at work.

Are you interested in learning more? Explore our Sustainable Business Strategy course and other business in society courses to discover how you can make a difference and become a purpose-driven leader.

This post was updated on May 20, 2024. It was originally published on February 6, 2019.

About the Author

Want a daily email of lesson plans that span all subjects and age groups?

What is the tragedy of the commons - nicholas amendolare.

2,990,724 Views

54,740 Questions Answered

Let’s Begin…

Is it possible that overfishing, super germs, and global warming are all caused by the same thing? In 1968, a man named Garrett Hardin sat down to write an essay about overpopulation. Within it, he discovered a pattern of human behavior that explains some of history’s biggest problems. Nicholas Amendolare describes the tragedy of the commons.

About TED-Ed Animations

TED-Ed Animations feature the words and ideas of educators brought to life by professional animators. Are you an educator or animator interested in creating a TED-Ed Animation? Nominate yourself here »

Meet The Creators

- Educator Nicholas Amendolare

- Director Lisa LaBracio

- Script Editor Eleanor Nelsen

- Composer Nicolas Martigne

- Animator Lisa LaBracio

- Background Artist Tara Sunil Thomas

- Clean Up Animator Tara Sunil Thomas

- Associate Producer Jessica Ruby

- Content Producer Gerta Xhelo

- Editorial Producer Alex Rosenthal

- Narrator Addison Anderson

More from How Things Work

Why does hitting your funny bone feel so horrible?

Lesson duration 04:19

261,073 Views

Why are scientists shooting mushrooms into space?

Lesson duration 05:29

362,808 Views

Why fish are better at breathing than you are

Lesson duration 05:21

293,286 Views

What happens in your body during a miscarriage?

Lesson duration 05:43

333,610 Views

- What Is the Tragedy of the Commons?

Tragedy of the Commons

William Forster Lloyd developed the concept of the tragedy of the commons in his 1833 essay. The tragedy of the commons refers to the economic theory describing a shared-resource system where individuals act according to their personal interests instead of working towards a mutual interest. In such a situation, the shared resources (commons) become overused, leading to their collapse. In modern times, the concept became famous after an article was written by an ecologist Garret Hardin in 1968. Shared resources that are defined in the tragedy of commons include the atmosphere, water resources and machinery.

Practical Application

The tragedy of the commons is applied in many situations, particularly regarding sustainable development and judicious use of shared resources. Discussions involving global warming, climate change, and environmental protection use the concept to analyze the effects and contribution of selfish human behavior with the deterioration of natural resources. The principle is also applied in the analysis of behaviors and trends in the fields of psychology, sociology, politics, anthropology, and taxation. In sustainable development, proponents suggest that the theory can be used as a self-regulatory measure where every concerned party is aware of the consequences of overexploitation.

The Commons Dilemma

The commons dilemma is a social situation where long-term results from the use of common resources conflict with the short-term selfish interests of individuals. Many factors influence the commons dilemma such as psychological, strategic, and structural elements. Researchers on the commons dilemma consider these factors in examining the use or disuse of common resources. Afterwards, they draw conclusions and recommend solutions to the problems arising from the utilization of the commons.

Some scientists criticize the theory of the tragedy of the commons as means of propagating private ownership. Hardin argued that a rational individual faced with the dilemma of the commons will seek to increase his assets. According to critics, rational people will first analyze the pros and cons of their actions on the long-term effects rather than the short-term effects before making decisions.

Solutions to the Tragedy of Commons

In his description, Hardin explains that while utilizing common resources, each user tries to maximize their own positive gain. All of these small individual percentages add up which cause negative results. Since freedom exists in commons, privatization was recommended as the only way to make each person accountable for the consequences of their actions. Government regulation on the use of common resources such as fisheries is also recommended as a practical solution to the tragedy of the commons. Another solution suggested is cooperation among users of the commons on how to use the available resources through collective restraint.

Relevant Examples

A real event that involves the collapse of the commons due to over-exploitation includes the fall of the Grand Banks Fisheries of Newfoundland due to cod numbers declining. The extinction of the Bluefin tuna in the Black and Caspian seas despite regulation measures is an example of the tragedy of the commons. Global warming, the dead zone along the Mississippi in the Gulf of Mexico, traffic congestion, population growth and unregulated logging are also examples.

More in Economics

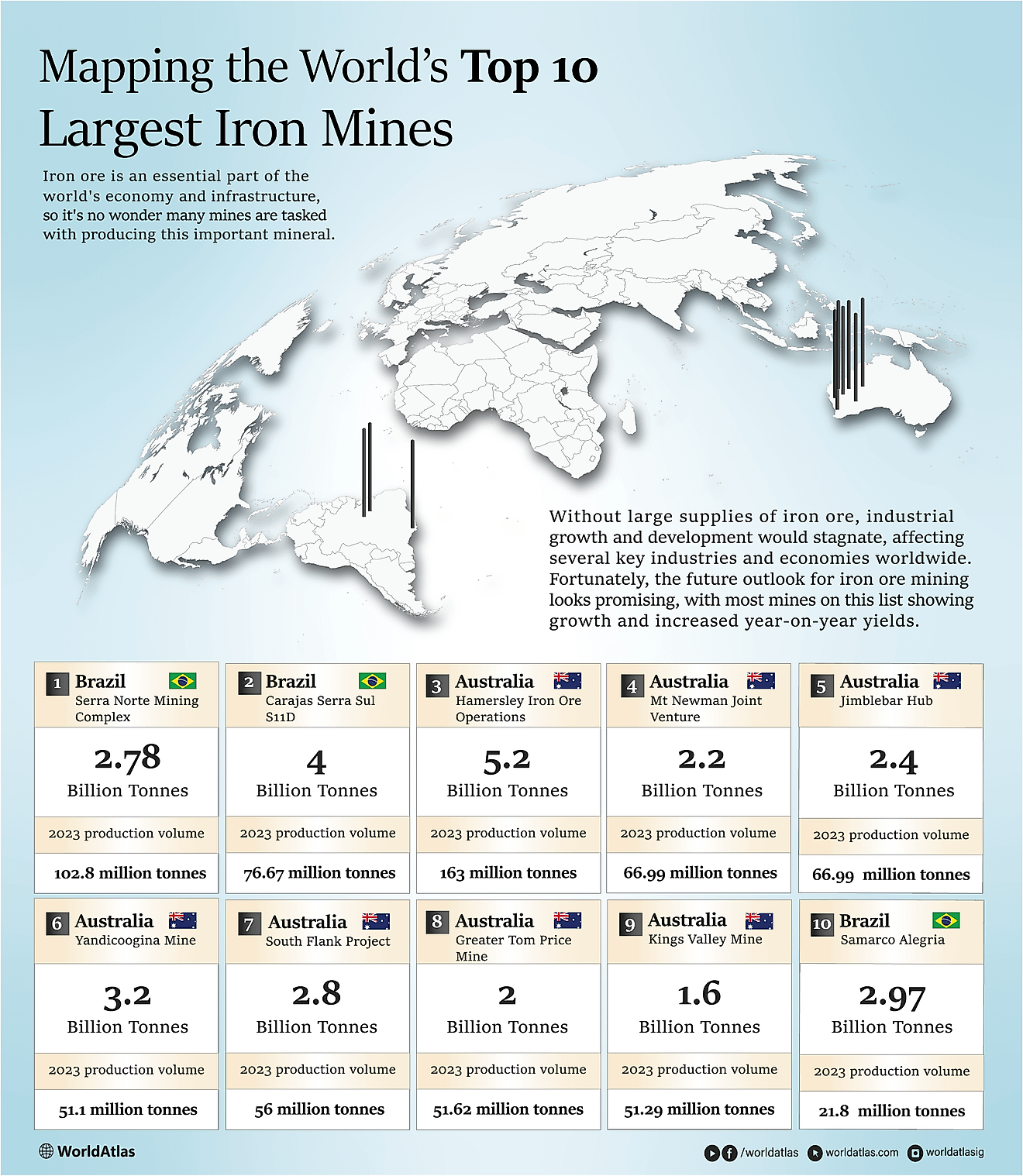

The 10 Largest Iron Ore Mines in the World

The 10 Largest Iron Mines In The World

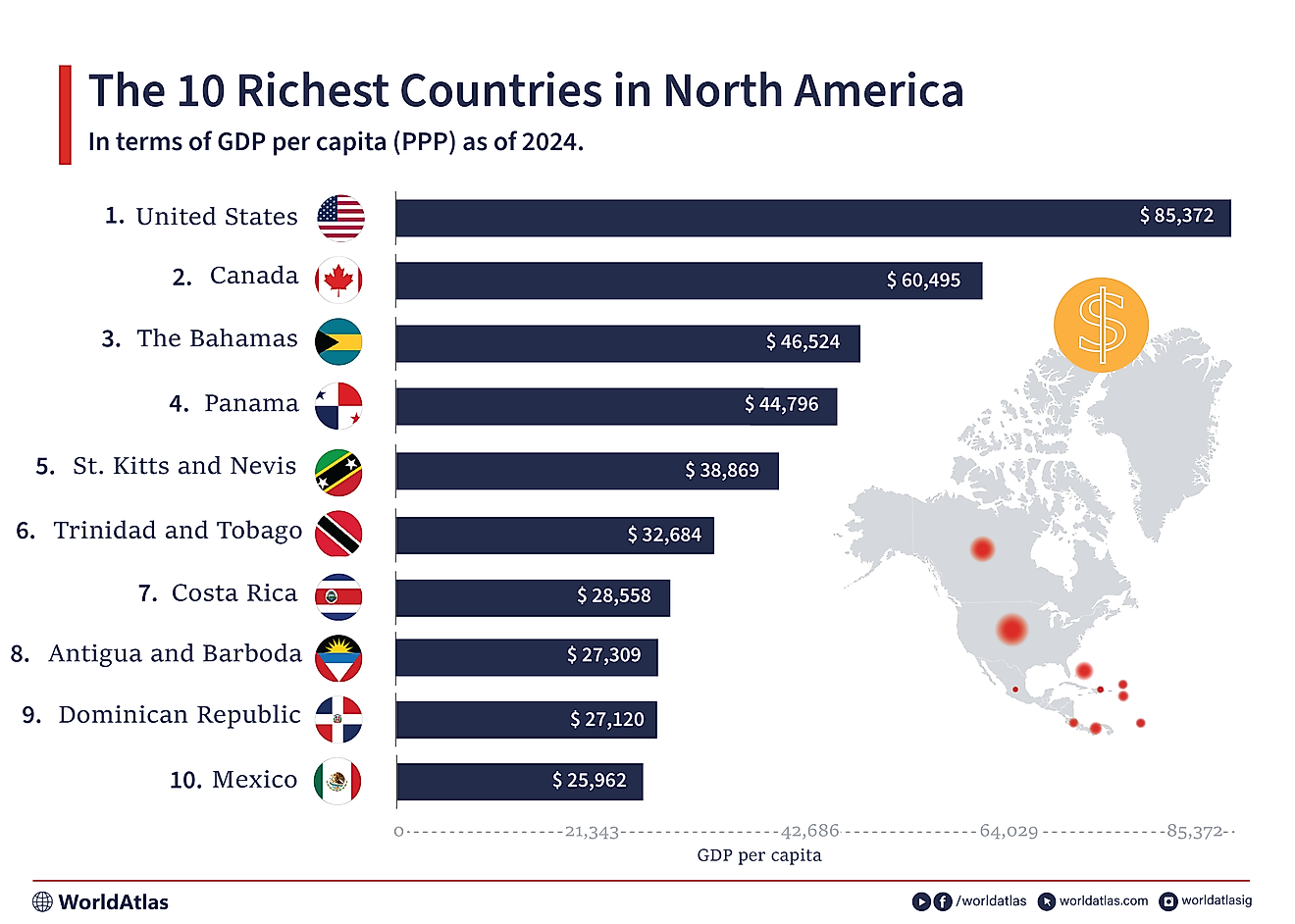

The Richest Landlocked Countries In The World

The 10 Largest Potash Producing Countries in the World

The 10 Largest Coal Mines in the World

10 Richest US States

The 10 Largest Copper Mines in the World

The Richest Countries in North America

- Search Search Please fill out this field.

What Is the Tragedy of the Commons?

Economic theory, supply and demand, preventing the tragedy of the commons, the bottom line.

- Guide to Microeconomics

What Is the Tragedy of the Commons in Economics?

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Group1805-3b9f749674f0434184ef75020339bd35.jpg)

A common resource or "commons" is any resource, such as water or land, that provides users with tangible benefits but which nobody has an exclusive claim. The tragedy of the commons is an economic problem where the individual consumes a resource at the expense of society.

If an individual acts in their best interest, it can result in harmful over-consumption to the detriment of all. This phenomenon may result in under-investment and total depletion of a shared resource.

Key Takeaways

- The tragedy of the commons is an economic problem where the individual consumes a resource at the expense of society.

- A common resource or "commons" is any resource, such as water or land, that provides users with tangible benefits but which nobody has an exclusive claim.

- The tragedy of the commons occurs when an economic good is rivalrous in consumption, non-excludable, scarce, and a common-pool resource.

Investopedia / Julie Bang

The tragedy of the commons is an economic theory claiming that individuals tend to exploit shared resources so that demand outweighs supply, and it becomes unavailable for the whole.

In 1968 evolutionary biologist Garrett Hardin published "The Tragedy of the Commons" in the peer-reviewed journal Science , which addressed the growing concern of overpopulation. Hardin used an example of sheep grazing land, taken from the early English economist William Forster Lloyd.

Grazing lands that are held as private property are prudently used by the landholder to preserve the land and the health of the herd. Common grazing lands become over-saturated with livestock because the food the animals consume is shared among all sheepherders. Hardin equated his point to humans who over-consume the commonly accessible scarce resource, making it harder to find.

The tragedy of the commons occurs when an economic good is rivalrous in consumption, non-excludable, scarce, and a common-pool resource . Each consumer consumes as much as they can as fast as they can before others deplete the good, and no one has the incentive to reinvest in maintaining or reproducing the good.

- Rival good: A rival good is one that only one person can consume and cannot be shared. All consumers are rivals competing for that unit, and each person’s consumption subtracts from the total supply of the good.

- Non-excludable: A good is non-excludable when individual consumers are unable to prevent others from also consuming it.

- Scarce: The good must be scarce since a non-scarce good cannot be rivalrous in consumption.

- Common-pool resource: A common-pool resource functions as a hybrid between a public and private good because it is shared and available to everyone but also scarce, with a finite supply .

Institutional and technological factors play a role in the rivalry and excludability of a good. Societies have developed methods of dividing and enforcing exclusive rights to economic goods and natural resources or punishing those who over-consume common resources.

Regulatory Solutions

Top-down government regulation or direct control of a common-pool resource can reduce over-consumption, and government investment in the conservation and renewal of the resource can help prevent its depletion. Government regulation can limit how many cattle may graze on government lands or issue fish catch quotas.

Assigning private property rights over resources to individuals can convert a common-pool resource into a private good . Technologically it may mean developing a way to identify, measure, and mark units or parcels of the common pool resource into private holdings, such as branding cattle.

William Forster Lloyd argued for this around the time of the English Parliament’s Enclosure Acts, which stripped traditional common property arrangements to grazing lands and fields and divided the land into private holdings.

Collective Solutions

Economists led by Nobelist Elinor Ostrom touted customary arrangements among rural villagers and aristocratic lords, including common access to most grazing and farmlands and managing their use and conservation. Practices such as crop rotation, seasonal grazing, and enforceable sanctions against overuse and abuse of the resource meant collective action arrangements readily overcame the tragedy of the commons.

Elinor Ostrom was the first woman, and one of just two women, to win the Nobel prize in economics.

Collective action is used where technical or natural physical challenges prevent the division of a common-pool resource into small private parcels by instead relying on measures to address the good’s rivalry in consumption by regulating consumption.

Has the Tragedy of the Commons Led to Extinction of a Resource?

The extinction of the dodo bird is a historical example of the tragedy of the commons. An easy-to-hunt, flightless bird native to only a few small islands, the dodo was a source of meat for sailors traveling the southern Indian Ocean. Due to overhunting, the dodo was driven to extinction less than a century after its discovery by Dutch sailors in 1598.

Where Is the Tragedy of the Commons Evident in Industry?

Before the 1960s, the Grand Banks fishery off the coast of Newfoundland was abundant with codfish because the fishery supported all the cod fishing they could do with existing fishing technology while reproducing itself each year through the natural spawning cycle. However, advancements in fishing technology made it so fisherfolk could catch massive amounts of codfish unsupportable with natural replenishment. With no framework of property rights or institutional common regulation, the entire industry collapsed by 1990.

How Is the Tragedy of the Commons Handled When Different Nations Share Resources?

Within individual countries, governments at the local level can manage shared resources with clear boundaries. At the international level, rules regarding shared resources are difficult to enforce across jurisdictions. When resources cannot be divided, international law regarding shared resources is essentially voluntary, according to the economist Scott Barrett at Columbia University.

The tragedy of the commons occurs when individuals overconsume a resource at the expense of society. When a common resource, such as water or land, is rivalrous in consumption, non-excludable, scarce, and a common-pool resource, the tragedy of the commons occurs. A common resource is any resource that provides users with tangible benefits but to which nobody has a claim.

Scientific American. " The Tragedy of the Tragedy of the Commons ."

American Association for the Advancement of Science. " The Tragedy of the Commons ."

The Nobel Prize. " Elinor Ostrom—Facts ."

Panorama. " How Humanity First Killed Dodo, Then Lost It as Well ."

National Park Service. " The Grand Banks: Where Have All the Cod Gone? "

Earth.org. " What Is the Tragedy of the Commons ?"

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/investing7-5bfc2b8d46e0fb0051bddff8.jpg)

- Terms of Service

- Editorial Policy

- Privacy Policy

Skip to Content

The tragedy of the ‘Tragedy of the Commons’

- Share via Twitter

- Share via Facebook

- Share via LinkedIn

- Share via E-mail

On the 50 th anniversary of Garrett Hardin’s influential essay about the 'freedom to breed,' the director of the CU Population Center contends he missed the mark

“Freedom to breed will bring ruin to all.”

The ominous statement reads more like a line from a dystopian novel than a peer-reviewed journal article. But it is, in fact, the punch-line of one of the most influential scientific essays to date.

Published in Science in December 1968 by the late University of California ecologist Garrett Hardin, the 6,000-word Tragedy of the Commons has been cited more than 38,000 times and informed policies on everything from climate change to intellectual property to digital content.

Lori Mae Hunter

Its bold assertion that, left unchecked, population growth will inevitably outpace the earth’s resources helped ignite a zero-population fervor in the 1970s, was often used to justify China’s now-defunct one-child policy, and is still conjured today in op-eds about immigration, Front Range overpopulation and fertility planning in the developing world.

But on the 50 th anniversary of its publication, a new CU Boulder-led paper published this month in the journal Nature Sustainability argues that Hardin’s theories about overpopulation were “simplistic” and “underdeveloped” and run the risk of leading to ill-informed policy.

“Pointing fingers at people who live in Tanzania and have large families or people who migrate here from elsewhere is not going to solve our environmental problems,” contends lead author Lori Mae Hunter, director of the CU Population Center at the Institute of Behavioral Science .

“It distracts us from looking at the way we live our own lives, our own consumption patterns and the way we build our own transportation and energy systems.”

Selfish herdsmen, a growing flock, and climate change

Hardin’s parable centers around a flock of hypothetical herdsman who, if given access to a communal pasture, will increase their herd size until they collectively degrade the pasture. “Ultimately, the commons collapses, hence the tragedy,” summarizes Hunter, who also chairs the sociology department.

The metaphor is most often conjured in the context of environmental protection: The global atmosphere is the “commons.” Owned by no one, used by everyone, and left unregulated it, like the pasture, is doomed to be overexploited and ruined.

Hardin’s parable centers around a flock of hypothetical herdsman who, if given access to a communal pasture, will increase their herd size until they collectively degrade the pasture. “Ultimately, the commons collapses, hence the tragedy,” summarizes Hunter.

That prediction has been debated for years, with one challenger, the late Elinor Ostrom, winning a Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences for her elucidation of a more optimistic real-life scenario—one in which small communities around the globe have managed to devise ways to successfully manage common resources like grazing land, forests and irrigation waters.

But Hardin’s second argument—the overpopulation argument—has not received the same critical attention.

That’s the task that Hunter and co-author Aseem Prakash, a political scientist at University of Washington, set out to do.

“It’s time to move past Hardinesque population alarmism … in order to develop better-informed policy,” they write.

Relinquishing the freedom to breed

In his essay, Hardin bluntly applies the “tragedy of the commons” idea to parenting, suggesting that the availability of food and other resources as part of the “welfare state” drives people to procreate and overpopulate:

“If each human family were dependent only on its own resources; if the children of improvident parents starved to death; if, thus, overbreeding brought its own punishment to the germ line—then there would be no public interest in controlling the breeding of families. But our society is deeply committed to the welfare state,” he wrote. His solution: Mandated population control:

“The only way we can preserve and nurture other and more precious freedoms is by relinquishing the freedom to breed.”

That argument had ripple effects, notes Prakash, indirectly fueling heated arguments within the Sierra Club over whether population control, including stronger checks against U.S. immigration, should be a central pillar of their environmental agenda. (It is not).

We would not argue that population doesn’t matter at all when it comes to the environment. Of course it matters. But simply pointing a finger at others and saying you shouldn’t be here obscures all the other things we should be thinking about.”

“Even today, with all the discussions of the border wall, in the back of the mind is Hardin’s overpopulation thesis again. That if you have too many resources, people will in-migrate and procreate,” said Prakash. “What we are pointing out is that is much more complex than that.”

They note that while the birth rate in the United States is at its lowest in 30 years, 51 percent of people here still believe the population is growing too fast.

Meanwhile, they add, in the places where the population is truly growing rapidly, carbon emissions per capita are minuscule compared to those in the West. For instance, U.S. residents emit 16.49 tons per capita in carbon emissions, while in Tanzania, per capita emissions run around 0.22 tons.

The complex reasons women get pregnant, or don’t

While Hardin drew a simple conclusion—that availability of resources drives procreation—Prakash and Hunter also point to a complex web of factors, including social values, cultural norms and local reproductive health policies, that contribute to family planning.

For instance, in Nepal, where resources are scarce, women tend to want to have more children to help them to gather those resources—such as firewood and food for their animals.