What makes a good life? Existentialists believed we should embrace freedom and authenticity

Indigenous Fellow - Assistant Professor in Philosophy and History, Bond University

Disclosure statement

Oscar Davis does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Bond University provides funding as a member of The Conversation AU.

View all partners

How do we live good, fulfilling lives?

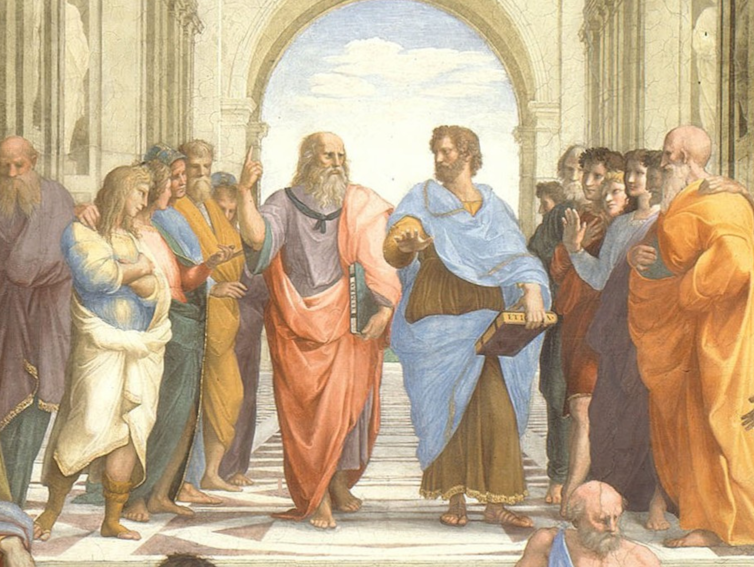

Aristotle first took on this question in his Nicomachean Ethics – arguably the first time anyone in Western intellectual history had focused on the subject as a standalone question.

He formulated a teleological response to the question of how we ought to live. Aristotle proposed, in other words, an answer grounded in an investigation of our purpose or ends ( telos ) as a species.

Our purpose, he argued, can be uncovered through a study of our essence – the fundamental features of what it means to be human.

Ends and essences

“Every skill and every inquiry, and similarly every action and rational choice, is thought to aim at some good;” Aristotle states, “and so the good has been aptly described as that at which everything aims.”

To understand what is good, and therefore what one must do to achieve the good, we must first understand what kinds of things we are. This will allow us to determine what a good or a bad function actually is.

For Aristotle, this is a generally applicable truth. Take a knife, for example. We must first understand what a knife is in order to determine what would constitute its proper function. The essence of a knife is that it cuts; that is its purpose. We can thus make the claim that a blunt knife is a bad knife – if it does not cut well, it is failing in an important sense to properly fulfil its function. This is how essence relates to function, and how fulfilling that function entails a kind of goodness for the thing in question.

Of course, determining the function of a knife or a hammer is much easier than determining the function of Homo sapiens , and therefore what good, fulfilling lives might involve for us as a species.

Aristotle argues that our function must be more than growth, nutrition and reproduction, as plants are also capable of this. Our function must also be more than perception, as non-human animals are capable of this. He thus proposes that our essence – what makes us unique – is that humans are capable of reasoning.

What a good, flourishing human life involves, therefore, is “some kind of practical life of that part that has reason”. This is the starting point of Aristotle’s ethics.

We must learn to reason well and develop practical wisdom and, in applying this reason to our decisions and judgements, we must learn to find the right balance between the excess and deficiency of virtue.

It is only by living a life of “virtuous activity in accordance with reason”, a life in which we flourish and fulfil the functions that flow from a deep understanding of and appreciation for what defines us, that we can achieve eudaimonia – the highest human good.

Read more: Friday essay: how philosophy can help us become better friends

Existence precedes essence

Aristotle’s answer was so influential that it shaped the development of Western values for millennia. Thanks to philosophers and theologians such as Thomas Aquinas , his enduring influence can be traced through the medieval period to the Renaissance and on to the Enlightenment.

During the Enlightenment, the dominant philosophical and religious traditions, which included Aristotle’s work, were reexamined in light of new Western principles of thought.

Beginning in the 18th century, the Enlightenment era saw the birth of modern science, and with it the adoption of the principle nullius in verba – literally, “take nobody’s word for it” – which became the motto of the Royal Society . There was a corresponding proliferation of secular approaches to understanding the nature of reality and, by extension, the way we ought to live our lives.

One of the most influential of these secular philosophies was existentialism. In the 20th century, Jean-Paul Sartre , a key figure in existentialism, took up the challenge of thinking about the meaning of life without recourse to theology. Sartre argued that Aristotle, and those who followed in Aristotle’s footsteps, had it all back-to-front.

Existentialists see us as going about our lives making seemingly endless choices. We choose what we wear, what we say, what careers we follow, what we believe. All of these choices make up who we are. Sartre summed up this principle in the formula “existence precedes essence”.

The existentialists teach us that we are completely free to invent ourselves, and therefore completely responsible for the identities we choose to adopt. “The first effect of existentialism,” Sartre wrote in his 1946 essay Existentialism is a Humanism , “is that it puts every man in possession of himself as he is, and places the entire responsibility for his existence squarely upon his own shoulders.”

Crucial to living an authentic life, the existentialists would say, is recognising that we desire freedom above everything else. They maintain we ought never to deny the fact we are fundamentally free. But they also acknowledge we have so much choice about what we can be and what we can do that it is a source of anguish. This anguish is a felt sense of our profound responsibility.

The existentialists shed light on an important phenomenon: we all convince ourselves, at some point and to some extent, that we are “bound by external circumstances” in order to escape the anguish of our inescapable freedom. Believing we possess a predefined essence is one such external circumstance.

But the existentialists provide a range of other psychologically revealing examples. Sartre tells a story of watching a waiter in a cafe in Paris. He observes that the waiter moves a little too precisely, a little too quickly, and seems a little too eager to impress. Sartre believes the waiter’s exaggeration of waiter-hood is an act – that the waiter is deceiving himself into being a waiter.

In doing so, argues Sartre, the waiter denies his authentic self. He has opted instead to assume the identity of something other than a free and autonomous being. His act reveals he is denying his own freedom, and ultimately his own humanity. Sartre calls this condition “bad faith”.

Read more: Finding your essential self: the ancient philosophy of Zhuangzi explained

An authentic life

Contrary to Aristotle’s conception of eudaimonia , the existentialists regard acting authentically as the highest good. This means never acting in such a way that denies we are free. When we make a choice, that choice must be fully ours. We have no essence; we are nothing but what we make for ourselves.

One day, Sartre was visited by a pupil, who sought his advice about whether he should join the French forces and avenge his brother’s death, or stay at home and provide vital support for his mother. Sartre believed the history of moral philosophy was of no help in this situation. “You are free, therefore choose,” he replied to the pupil – “that is to say, invent”. The only choice the pupil could make was one that was authentically his own.

We all have feelings and questions about the meaning and purpose of our lives, and it is not as simple as picking a side between the Aristotelians, the existentialists, or any of the other moral traditions. In his essay, That to Study Philosophy is to Learn to Die (1580), Michel de Montaigne finds what is perhaps an ideal middle ground. He proposes “the premeditation of death is the premeditation of liberty” and that “he who has learnt to die has forgot what it is to be a slave”.

In his typical style of jest, Montaigne concludes: “I want death to take me planting cabbages, but without any careful thought of him, and much less of my garden’s not being finished.”

Perhaps Aristotle and the existentialists could agree that it is just in thinking about these matters – purposes, freedom, authenticity, mortality – that we overcome the silence of never understanding ourselves. To study philosophy is, in this sense, to learn how to live.

- Jean-Paul Sartre

- Existentialism

- Essentialism

Sydney Horizon Educators (Identified)

Senior Disability Services Advisor

Deputy Social Media Producer

Associate Professor, Occupational Therapy

GRAINS RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT CORPORATION CHAIRPERSON

1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

Philosophy, One Thousand Words at a Time

Existentialism

Author: Addison Ellis Category: Phenomenology and Existentialism , Ethics Word Count: 1000

Video below

1. Mr. Green

Mr. Green is many things: a teacher, a husband, a father, a college graduate, and a medical patient, to name a few. Some of his features may be counted as accomplishments, others failures, and yet others unlucky accidents thrust upon him by the world. But is this all there is to Mr. Green?

According to the philosophical tradition of Existentialism , something is missing in this characterization. For the existentialist, we are not merely a collection of facts; we are also self-conscious, living, caring beings . While trees, seagulls, and fish are all similarly alive , they do not live the same sorts of lives that we do. Existentialism is the philosophical science of our peculiar sorts of lives. 1

Our lives are ongoing activities . Mr. Green’s existence, just like the existence of every similarly self-conscious, caring being, is more than a series of events or a set of facts. In providing such an understanding, Existentialism breathes new life into old ideas about the nature of value, freedom, and even more broadly into questions about the nature of reality and knowledge. In this essay, we will restrict our focus to what existentialists have to say about human nature and living a meaningful life. 2

2. Existence Precedes Essence

Many philosophers, both historical and contemporary, believe that the way something is is determined by its essence . That is, essences are fixed determinants of the way things are.

Those who follow this line of thought may take essences to be the non-physical and eternal standards to which things conform. 3 Thus, the essence of a table is what determines table-like behavior. Likewise, the essence of a human being is what determines what a human being is like. These fixed determinants can range from principles given by God to those we attribute to society.

Martin Heidegger helpfully points out that we often speak of the way “one” does things, referring to no one in particular. We say things like “this is the way one does x ,” because doing x correctly means doing it in accordance with some pre-established standard. 4 But Heidegger believes that this way of thinking should not extend to our ways of living. That is, we should not understand ourselves as living correctly only when we live “as one lives.” Existentialism reverses this picture by suggesting that it is our living which determines our essence, and not the other way around.

Let’s go back to Mr. Green. In order to understand what sort of being he is, we must understand that who he is is not a fact he was born with, nor is it a fact that was established merely after some important events in his life unfolded. He is who he is because of what he chooses , and one can never stop choosing. For even by trying to decide that I will no longer make choices, I am making the choice not to choose. Jean-Paul Sartre, the most famous of the historical existentialists, expresses the idea that we are who we make ourselves, and not who we are pre-determined to be, with a concise slogan: “existence precedes essence.” 5

3. Freedom & Authenticity

If Sartre is right and our lives are essentially up to us, then existentialists must also be committed to a robust kind of freedom , since we are not determined by what happens to us.

But if Mr. Green’s essence is up to him, and he’s free to craft his essence as he pleases, then on what standards does he draw to guide himself in his crafting? It would seem that existentialists cannot simply draw from a set of independently existing standards. If this were so, then who we are is again simply a matter of conforming to some pre-established standards.

If the standards are up to us, then why should we choose any one set of standards over any other? That is, how can we make sense of the idea that there is a right way to live and a wrong way to live if there is no external standard for judging whether we have made the right choice ? 6

This is a difficult issue in Existentialism, one that is grappled with by all the major figures in the tradition. The answer we will entertain here is that it is possible to find a standard within our own activities that determines whether they are being performed well or poorly. This is what existentialists refer to as authenticity . 7

Mr. Green, knowing that he has terminal lung cancer, can arrange the final years of his life in a variety of ways; it is up to him how he will structure his remaining time. But there are two ways in which he can choose:

(i) he can see his choices as simply thrust upon him by the world—i.e., he can believe that he really doesn’t have a choice at all,

(ii) he can see his choices as his own while taking full responsibility for them.

Only by acting in this way is Mr. Green acting authentically , since it is only under these conditions that he is true to himself. Acting inauthentically , then, involves excusing oneself from responsibility by ignoring one’s freedom. The existentialist hopes to have shown that despite the lack of external guidance, we are perfectly capable of telling from within our own activities whether we are acting authentically or inauthentically. 8

4. Conclusions

Existentialism gives us some tools for understanding (i) our essence, and (ii) how it is possible to live a meaningful life.

The ideas defended by existentialists have been thought to have both positive and negative implications for us. On the one hand, our lives are not determined by God, society, or contingent circumstances; on the other hand, absolute freedom can be a burden. As Sartre puts it, “man is condemned to be free.” 9 That is, it was never up to us to be free, and we cannot cease to be free. Since we must be free, and because freedom entails responsibility, we can never opt out of being responsible. Thus we are simultaneously unencumbered and encumbered by our freedom to choose who we will be.

1 This is not to denigrate the lives of things radically different from us, but merely to point out that paradigm human creatures live peculiar sorts of lives. The demarcating line here between lives like ours and lives unlike ours needn’t be drawn along purely biological lines. There are potentially things—certain non-human animals, futuristic artificially intelligent systems—that have lives like ours, and whose lives are properly studied by Existentialism. Similarly, there are some biological humans—the very young, the severely mentally handicapped—whose lives are not like ours , and hence, whose lives are not properly studied by Existentialism.

2 Existential themes can be traced as far back as St. Augustine in his Confessions . Most philosophers today agree, however, that 19 th- Century Danish philosopher Søren Kierkegaard and 19th-Century German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche did much to provide the framework for what Existentialism would become in its more definitive era. The major figures of Existentialism include not only Kierkegaard and Nietzsche, but also (perhaps more importantly) Jean-Paul Sartre and Martin Heidegger, in the 20 th century.

3 What Plato calls “forms.”

4 This is an expression of what Heidegger calls the They-self, Being and Time S ection 129

5 Sartre, Existentialism Is a Humanism (20)

6 There is some debate about whether Existentialism is actually a moral theory. One reason for the doubt is precisely this one – that there is nothing action-guiding about Existentialism.

7 Steven Crowell makes this point in his SEP article when discussing Nietzsche’s idea of a ‘ruling instinct.’

8 There is a serious worry here that must be addressed by the existentialist, and I will leave it as an exercise for the reader. While it seems better to act authentically than to act inauthentically, don’t we need to meet even more standards in order to count as living a truly good life? In other words, we might worry about whether authenticity is the only guiding principle that we really need. Perhaps it is possible to be an authentic genocidal dictator. If so, then perhaps Existentialism does not, on its own, suffice as a moral theory.

9 Sartre, op. cit . (29)

Crowell, Steven. “Existentialism.” Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy . Stanford University, 23 Aug. 2004. Web. 18 Apr. 2014.

Heidegger, Martin. Being and Time . Trans. John Macquarrie. Ed. Edward Robinson. New York: HarperPerennial/Modern Thought, 2008.

Sartre, Jean-Paul. Existentialism Is a Humanism . Ed. John Kulka and Arlette Elkaïm-Sartre. New Haven: Yale UP, 2007.

Related Essays

African American Existentialism: DuBois, Locke, Thurman, and King by Anthony Sean Neal

Happiness by Kiki Berk

Meaning in Life: What Makes Our Lives Meaningful? by Matthew Pianalto

Moral Luck by Jonathan Spelman

Free Will and Free Choice by Jonah Nagashima

Free Will and Moral Responsibility by Chelsea Haramia

About the Author

Addison Ellis is an Assistant Professor of Philosophy at The American University in Cairo. His interests include Kant and Post-Kantian European Philosophy, with special attention to the topics of self-consciousness, ontology, and cognitive capacities and attitudes. philpeople.org/profiles/addison-ellis

Follow 1000-Word Philosophy on Facebook and Twitter and subscribe to receive email notifications of new essays at 1000WordPhilosophy.com

Share this:, 7 thoughts on “ existentialism ”.

- Pingback: The Meaning of Life: What’s the Point? – 1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

- Pingback: Meaning in Life: What Makes Our Lives Meaningful? – 1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

- Pingback: African American Existentialism – 1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

- Pingback: Is Death Bad? Epicurus and Lucretius on the Fear of Death – 1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

- Pingback: Existentialism: A Collection of Online Resources and Key Quotes - The Daily Idea

- Pingback: Existentialism and Caterialism – The Babel of Languages and the Substrate of Nature

- Pingback: Introduction to Existentialism – Naung Mon Oo

Comments are closed.

- Table of Contents

- Random Entry

- Chronological

- Editorial Information

- About the SEP

- Editorial Board

- How to Cite the SEP

- Special Characters

- Advanced Tools

- Support the SEP

- PDFs for SEP Friends

- Make a Donation

- SEPIA for Libraries

- Entry Contents

Bibliography

Academic tools.

- Friends PDF Preview

- Author and Citation Info

- Back to Top

The Meaning of Life

Many major historical figures in philosophy have provided an answer to the question of what, if anything, makes life meaningful, although they typically have not put it in these terms (with such talk having arisen only in the past 250 years or so, on which see Landau 1997). Consider, for instance, Aristotle on the human function, Aquinas on the beatific vision, and Kant on the highest good. Relatedly, think about Koheleth, the presumed author of the Biblical book Ecclesiastes, describing life as “futility” and akin to “the pursuit of wind,” Nietzsche on nihilism, as well as Schopenhauer when he remarks that whenever we reach a goal we have longed for we discover “how vain and empty it is.” While these concepts have some bearing on happiness and virtue (and their opposites), they are straightforwardly construed (roughly) as accounts of which highly ranked purposes a person ought to realize that would make her life significant (if any would).

Despite the venerable pedigree, it is only since the 1980s or so that a distinct field of the meaning of life has been established in Anglo-American-Australasian philosophy, on which this survey focuses, and it is only in the past 20 years that debate with real depth and intricacy has appeared. Two decades ago analytic reflection on life’s meaning was described as a “backwater” compared to that on well-being or good character, and it was possible to cite nearly all the literature in a given critical discussion of the field (Metz 2002). Neither is true any longer. Anglo-American-Australasian philosophy of life’s meaning has become vibrant, such that there is now way too much literature to be able to cite comprehensively in this survey. To obtain focus, it tends to discuss books, influential essays, and more recent works, and it leaves aside contributions from other philosophical traditions (such as the Continental or African) and from non-philosophical fields (e.g., psychology or literature). This survey’s central aim is to acquaint the reader with current analytic approaches to life’s meaning, sketching major debates and pointing out neglected topics that merit further consideration.

When the topic of the meaning of life comes up, people tend to pose one of three questions: “What are you talking about?”, “What is the meaning of life?”, and “Is life in fact meaningful?”. The literature on life's meaning composed by those working in the analytic tradition (on which this entry focuses) can be usefully organized according to which question it seeks to answer. This survey starts off with recent work that addresses the first, abstract (or “meta”) question regarding the sense of talk of “life’s meaning,” i.e., that aims to clarify what we have in mind when inquiring into the meaning of life (section 1). Afterward, it considers texts that provide answers to the more substantive question about the nature of meaningfulness (sections 2–3). There is in the making a sub-field of applied meaning that parallels applied ethics, in which meaningfulness is considered in the context of particular cases or specific themes. Examples include downshifting (Levy 2005), implementing genetic enhancements (Agar 2013), making achievements (Bradford 2015), getting an education (Schinkel et al. 2015), interacting with research participants (Olson 2016), automating labor (Danaher 2017), and creating children (Ferracioli 2018). In contrast, this survey focuses nearly exclusively on contemporary normative-theoretical approaches to life’s meanining, that is, attempts to capture in a single, general principle all the variegated conditions that could confer meaning on life. Finally, this survey examines fresh arguments for the nihilist view that the conditions necessary for a meaningful life do not obtain for any of us, i.e., that all our lives are meaningless (section 4).

1. The Meaning of “Meaning”

2.1. god-centered views, 2.2. soul-centered views, 3.1. subjectivism, 3.2. objectivism, 3.3. rejecting god and a soul, 4. nihilism, works cited, classic works, collections, books for the general reader, other internet resources, related entries.

One of the field's aims consists of the systematic attempt to identify what people (essentially or characteristically) have in mind when they think about the topic of life’s meaning. For many in the field, terms such as “importance” and “significance” are synonyms of “meaningfulness” and so are insufficiently revealing, but there are those who draw a distinction between meaningfulness and significance (Singer 1996, 112–18; Belliotti 2019, 145–50, 186). There is also debate about how the concept of a meaningless life relates to the ideas of a life that is absurd (Nagel 1970, 1986, 214–23; Feinberg 1980; Belliotti 2019), futile (Trisel 2002), and not worth living (Landau 2017, 12–15; Matheson 2017).

A useful way to begin to get clear about what thinking about life’s meaning involves is to specify the bearer. Which life does the inquirer have in mind? A standard distinction to draw is between the meaning “in” life, where a human person is what can exhibit meaning, and the meaning “of” life in a narrow sense, where the human species as a whole is what can be meaningful or not. There has also been a bit of recent consideration of whether animals or human infants can have meaning in their lives, with most rejecting that possibility (e.g., Wong 2008, 131, 147; Fischer 2019, 1–24), but a handful of others beginning to make a case for it (Purves and Delon 2018; Thomas 2018). Also under-explored is the issue of whether groups, such as a people or an organization, can be bearers of meaning, and, if so, under what conditions.

Most analytic philosophers have been interested in meaning in life, that is, in the meaningfulness that a person’s life could exhibit, with comparatively few these days addressing the meaning of life in the narrow sense. Even those who believe that God is or would be central to life’s meaning have lately addressed how an individual’s life might be meaningful in virtue of God more often than how the human race might be. Although some have argued that the meaningfulness of human life as such merits inquiry to no less a degree (if not more) than the meaning in a life (Seachris 2013; Tartaglia 2015; cf. Trisel 2016), a large majority of the field has instead been interested in whether their lives as individual persons (and the lives of those they care about) are meaningful and how they could become more so.

Focusing on meaning in life, it is quite common to maintain that it is conceptually something good for its own sake or, relatedly, something that provides a basic reason for action (on which see Visak 2017). There are a few who have recently suggested otherwise, maintaining that there can be neutral or even undesirable kinds of meaning in a person’s life (e.g., Mawson 2016, 90, 193; Thomas 2018, 291, 294). However, these are outliers, with most analytic philosophers, and presumably laypeople, instead wanting to know when an individual’s life exhibits a certain kind of final value (or non-instrumental reason for action).

Another claim about which there is substantial consensus is that meaningfulness is not all or nothing and instead comes in degrees, such that some periods of life are more meaningful than others and that some lives as a whole are more meaningful than others. Note that one can coherently hold the view that some people’s lives are less meaningful (or even in a certain sense less “important”) than others, or are even meaningless (unimportant), and still maintain that people have an equal standing from a moral point of view. Consider a consequentialist moral principle according to which each individual counts for one in virtue of having a capacity for a meaningful life, or a Kantian approach according to which all people have a dignity in virtue of their capacity for autonomous decision-making, where meaning is a function of the exercise of this capacity. For both moral outlooks, we could be required to help people with relatively meaningless lives.

Yet another relatively uncontroversial element of the concept of meaningfulness in respect of individual persons is that it is logically distinct from happiness or rightness (emphasized in Wolf 2010, 2016). First, to ask whether someone’s life is meaningful is not one and the same as asking whether her life is pleasant or she is subjectively well off. A life in an experience machine or virtual reality device would surely be a happy one, but very few take it to be a prima facie candidate for meaningfulness (Nozick 1974: 42–45). Indeed, a number would say that one’s life logically could become meaningful precisely by sacrificing one’s well-being, e.g., by helping others at the expense of one’s self-interest. Second, asking whether a person’s existence over time is meaningful is not identical to considering whether she has been morally upright; there are intuitively ways to enhance meaning that have nothing to do with right action or moral virtue, such as making a scientific discovery or becoming an excellent dancer. Now, one might argue that a life would be meaningless if, or even because, it were unhappy or immoral, but that would be to posit a synthetic, substantive relationship between the concepts, far from indicating that speaking of “meaningfulness” is analytically a matter of connoting ideas regarding happiness or rightness. The question of what (if anything) makes a person’s life meaningful is conceptually distinct from the questions of what makes a life happy or moral, although it could turn out that the best answer to the former question appeals to an answer to one of the latter questions.

Supposing, then, that talk of “meaning in life” connotes something good for its own sake that can come in degrees and that is not analytically equivalent to happiness or rightness, what else does it involve? What more can we say about this final value, by definition? Most contemporary analytic philosophers would say that the relevant value is absent from spending time in an experience machine (but see Goetz 2012 for a different view) or living akin to Sisyphus, the mythic figure doomed by the Greek gods to roll a stone up a hill for eternity (famously discussed by Albert Camus and Taylor 1970). In addition, many would say that the relevant value is typified by the classic triad of “the good, the true, and the beautiful” (or would be under certain conditions). These terms are not to be taken literally, but instead are rough catchwords for beneficent relationships (love, collegiality, morality), intellectual reflection (wisdom, education, discoveries), and creativity (particularly the arts, but also potentially things like humor or gardening).

Pressing further, is there something that the values of the good, the true, the beautiful, and any other logically possible sources of meaning involve? There is as yet no consensus in the field. One salient view is that the concept of meaning in life is a cluster or amalgam of overlapping ideas, such as fulfilling higher-order purposes, meriting substantial esteem or admiration, having a noteworthy impact, transcending one’s animal nature, making sense, or exhibiting a compelling life-story (Markus 2003; Thomson 2003; Metz 2013, 24–35; Seachris 2013, 3–4; Mawson 2016). However, there are philosophers who maintain that something much more monistic is true of the concept, so that (nearly) all thought about meaningfulness in a person’s life is essentially about a single property. Suggestions include being devoted to or in awe of qualitatively superior goods (Taylor 1989, 3–24), transcending one’s limits (Levy 2005), or making a contribution (Martela 2016).

Recently there has been something of an “interpretive turn” in the field, one instance of which is the strong view that meaning-talk is logically about whether and how a life is intelligible within a wider frame of reference (Goldman 2018, 116–29; Seachris 2019; Thomas 2019; cf. Repp 2018). According to this approach, inquiring into life’s meaning is nothing other than seeking out sense-making information, perhaps a narrative about life or an explanation of its source and destiny. This analysis has the advantage of promising to unify a wide array of uses of the term “meaning.” However, it has the disadvantages of being unable to capture the intuitions that meaning in life is essentially good for its own sake (Landau 2017, 12–15), that it is not logically contradictory to maintain that an ineffable condition is what confers meaning on life (as per Cooper 2003, 126–42; Bennett-Hunter 2014; Waghorn 2014), and that often human actions themselves (as distinct from an interpretation of them), such as rescuing a child from a burning building, are what bear meaning.

Some thinkers have suggested that a complete analysis of the concept of life’s meaning should include what has been called “anti-matter” (Metz 2002, 805–07, 2013, 63–65, 71–73) or “anti-meaning” (Campbell and Nyholm 2015; Egerstrom 2015), conditions that reduce the meaningfulness of a life. The thought is that meaning is well represented by a bipolar scale, where there is a dimension of not merely positive conditions, but also negative ones. Gratuitous cruelty or destructiveness are prima facie candidates for actions that not merely fail to add meaning, but also subtract from any meaning one’s life might have had.

Despite the ongoing debates about how to analyze the concept of life’s meaning (or articulate the definition of the phrase “meaning in life”), the field remains in a good position to make progress on the other key questions posed above, viz., of what would make a life meaningful and whether any lives are in fact meaningful. A certain amount of common ground is provided by the point that meaningfulness at least involves a gradient final value in a person’s life that is conceptually distinct from happiness and rightness, with exemplars of it potentially being the good, the true, and the beautiful. The rest of this discussion addresses philosophical attempts to capture the nature of this value theoretically and to ascertain whether it exists in at least some of our lives.

2. Supernaturalism

Most analytic philosophers writing on meaning in life have been trying to develop and evaluate theories, i.e., fundamental and general principles, that are meant to capture all the particular ways that a life could obtain meaning. As in moral philosophy, there are recognizable “anti-theorists,” i.e., those who maintain that there is too much pluralism among meaning conditions to be able to unify them in the form of a principle (e.g., Kekes 2000; Hosseini 2015). Arguably, though, the systematic search for unity is too nascent to be able to draw a firm conclusion about whether it is available.

The theories are standardly divided on a metaphysical basis, that is, in terms of which kinds of properties are held to constitute the meaning. Supernaturalist theories are views according to which a spiritual realm is central to meaning in life. Most Western philosophers have conceived of the spiritual in terms of God or a soul as commonly understood in the Abrahamic faiths (but see Mulgan 2015 for discussion of meaning in the context of a God uninterested in us). In contrast, naturalist theories are views that the physical world as known particularly well by the scientific method is central to life’s meaning.

There is logical space for a non-naturalist theory, according to which central to meaning is an abstract property that is neither spiritual nor physical. However, only scant attention has been paid to this possibility in the recent Anglo-American-Australasian literature (Audi 2005).

It is important to note that supernaturalism, a claim that God (or a soul) would confer meaning on a life, is logically distinct from theism, the claim that God (or a soul) exists. Although most who hold supernaturalism also hold theism, one could accept the former without the latter (as Camus more or less did), committing one to the view that life is meaningless or at least lacks substantial meaning. Similarly, while most naturalists are atheists, it is not contradictory to maintain that God exists but has nothing to do with meaning in life or perhaps even detracts from it. Although these combinations of positions are logically possible, some of them might be substantively implausible. The field could benefit from discussion of the comparative attractiveness of various combinations of evaluative claims about what would make life meaningful and metaphysical claims about whether spiritual conditions exist.

Over the past 15 years or so, two different types of supernaturalism have become distinguished on a regular basis (Metz 2019). That is true not only in the literature on life’s meaning, but also in that on the related pro-theism/anti-theism debate, about whether it would be desirable for God or a soul to exist (e.g., Kahane 2011; Kraay 2018; Lougheed 2020). On the one hand, there is extreme supernaturalism, according to which spiritual conditions are necessary for any meaning in life. If neither God nor a soul exists, then, by this view, everyone’s life is meaningless. On the other hand, there is moderate supernaturalism, according to which spiritual conditions are necessary for a great or ultimate meaning in life, although not meaning in life as such. If neither God nor a soul exists, then, by this view, everyone’s life could have some meaning, or even be meaningful, but no one’s life could exhibit the most desirable meaning. For a moderate supernaturalist, God or a soul would substantially enhance meaningfulness or be a major contributory condition for it.

There are a variety of ways that great or ultimate meaning has been described, sometimes quantitatively as “infinite” (Mawson 2016), qualitatively as “deeper” (Swinburne 2016), relationally as “unlimited” (Nozick 1981, 618–19; cf. Waghorn 2014), temporally as “eternal” (Cottingham 2016), and perspectivally as “from the point of view of the universe” (Benatar 2017). There has been no reflection as yet on the crucial question of how these distinctions might bear on each another, for instance, on whether some are more basic than others or some are more valuable than others.

Cross-cutting the extreme/moderate distinction is one between God-centered theories and soul-centered ones. According to the former, some kind of connection with God (understood to be a spiritual person who is all-knowing, all-good, and all-powerful and who is the ground of the physical universe) constitutes meaning in life, even if one lacks a soul (construed as an immortal, spiritual substance that contains one’s identity). In contrast, by the latter, having a soul and putting it into a certain state is what makes life meaningful, even if God does not exist. Many supernaturalists of course believe that God and a soul are jointly necessary for a (greatly) meaningful existence. However, the simpler view, that only one of them is necessary, is common, and sometimes arguments proffered for the complex view fail to support it any more than the simpler one.

The most influential God-based account of meaning in life has been the extreme view that one’s existence is significant if and only if one fulfills a purpose God has assigned. The familiar idea is that God has a plan for the universe and that one’s life is meaningful just to the degree that one helps God realize this plan, perhaps in a particular way that God wants one to do so. If a person failed to do what God intends her to do with her life (or if God does not even exist), then, on the current view, her life would be meaningless.

Thinkers differ over what it is about God’s purpose that might make it uniquely able to confer meaning on human lives, but the most influential argument has been that only God’s purpose could be the source of invariant moral rules (Davis 1987, 296, 304–05; Moreland 1987, 124–29; Craig 1994/2013, 161–67) or of objective values more generally (Cottingham 2005, 37–57), where a lack of such would render our lives nonsensical. According to this argument, lower goods such as animal pleasure or desire satisfaction could exist without God, but higher ones pertaining to meaning in life, particularly moral virtue, could not. However, critics point to many non-moral sources of meaning in life (e.g., Kekes 2000; Wolf 2010), with one arguing that a universal moral code is not necessary for meaning in life, even if, say, beneficent actions are (Ellin 1995, 327). In addition, there are a variety of naturalist and non-naturalist accounts of objective morality––and of value more generally––on offer these days, so that it is not clear that it must have a supernatural source in God’s will.

One recurrent objection to the idea that God’s purpose could make life meaningful is that if God had created us with a purpose in mind, then God would have degraded us and thereby undercut the possibility of us obtaining meaning from fulfilling the purpose. The objection harks back to Jean-Paul Sartre, but in the analytic literature it appears that Kurt Baier was the first to articulate it (1957/2000, 118–20; see also Murphy 1982, 14–15; Singer 1996, 29; Kahane 2011; Lougheed 2020, 121–41). Sometimes the concern is the threat of punishment God would make so that we do God’s bidding, while other times it is that the source of meaning would be constrictive and not up to us, and still other times it is that our dignity would be maligned simply by having been created with a certain end in mind (for some replies to such concerns, see Hanfling 1987, 45–46; Cottingham 2005, 37–57; Lougheed 2020, 111–21).

There is a different argument for an extreme God-based view that focuses less on God as purposive and more on God as infinite, unlimited, or ineffable, which Robert Nozick first articulated with care (Nozick 1981, 594–618; see also Bennett-Hunter 2014; Waghorn 2014). The core idea is that for a finite condition to be meaningful, it must obtain its meaning from another condition that has meaning. So, if one’s life is meaningful, it might be so in virtue of being married to a person, who is important. Being finite, the spouse must obtain his or her importance from elsewhere, perhaps from the sort of work he or she does. This work also must obtain its meaning by being related to something else that is meaningful, and so on. A regress on meaningful conditions is present, and the suggestion is that the regress can terminate only in something so all-encompassing that it need not (indeed, cannot) go beyond itself to obtain meaning from anything else. And that is God. The standard objection to this relational rationale is that a finite condition could be meaningful without obtaining its meaning from another meaningful condition. Perhaps it could be meaningful in itself, without being connected to something beyond it, or maybe it could obtain its meaning by being related to something else that is beautiful or otherwise valuable for its own sake but not meaningful (Nozick 1989, 167–68; Thomson 2003, 25–26, 48).

A serious concern for any extreme God-based view is the existence of apparent counterexamples. If we think of the stereotypical lives of Albert Einstein, Mother Teresa, and Pablo Picasso, they seem meaningful even if we suppose there is no all-knowing, all-powerful, and all-good spiritual person who is the ground of the physical world (e.g., Wielenberg 2005, 31–37, 49–50; Landau 2017). Even religiously inclined philosophers have found this hard to deny these days (Quinn 2000, 58; Audi 2005; Mawson 2016, 5; Williams 2020, 132–34).

Largely for that reason, contemporary supernaturalists have tended to opt for moderation, that is, to maintain that God would greatly enhance the meaning in our lives, even if some meaning would be possible in a world without God. One approach is to invoke the relational argument to show that God is necessary, not for any meaning whatsoever, but rather for an ultimate meaning. “Limited transcendence, the transcending of our limits so as to connect with a wider context of value which itself is limited, does give our lives meaning––but a limited one. We may thirst for more” (Nozick 1981, 618). Another angle is to appeal to playing a role in God’s plan, again to claim, not that it is essential for meaning as such, but rather for “a cosmic significance....intead of a significance very limited in time and space” (Swinburne 2016, 154; see also Quinn 2000; Cottingham 2016, 131). Another rationale is that by fulfilling God’s purpose, we would meaningfully please God, a perfect person, as well as be remembered favorably by God forever (Cottingham 2016, 135; Williams 2020, 21–22, 29, 101, 108). Still another argument is that only with God could the deepest desires of human nature be satisfied (e.g., Goetz 2012; Seachris 2013, 20; Cottingham 2016, 127, 136), even if more surface desires could be satisfied without God.

In reply to such rationales for a moderate supernaturalism, there has been the suggestion that it is precisely by virtue of being alone in the universe that our lives would be particularly significant; otherwise, God’s greatness would overshadow us (Kahane 2014). There has also been the response that, with the opportunity for greater meaning from God would also come that for greater anti-meaning, so that it is not clear that a world with God would offer a net gain in respect of meaning (Metz 2019, 34–35). For example, if pleasing God would greatly enhance meaning in our lives, then presumably displeasing God would greatly reduce it and to a comparable degree. In addition, there are arguments for extreme naturalism (or its “anti-theist” cousin) mentioned below (sub-section 3.3).

Notice that none of the above arguments for supernaturalism appeals to the prospect of eternal life (at least not explicitly). Arguments that do make such an appeal are soul-centered, holding that meaning in life mainly comes from having an immortal, spiritual substance that is contiguous with one’s body when it is alive and that will forever outlive its death. Some think of the afterlife in terms of one’s soul entering a transcendent, spiritual realm (Heaven), while others conceive of one’s soul getting reincarnated into another body on Earth. According to the extreme version, if one has a soul but fails to put it in the right state (or if one lacks a soul altogether), then one’s life is meaningless.

There are three prominent arguments for an extreme soul-based perspective. One argument, made famous by Leo Tolstoy, is the suggestion that for life to be meaningful something must be worth doing, that something is worth doing only if it will make a permanent difference to the world, and that making a permanent difference requires being immortal (see also Hanfling 1987, 22–24; Morris 1992, 26; Craig 1994). Critics most often appeal to counterexamples, suggesting for instance that it is surely worth your time and effort to help prevent people from suffering, even if you and they are mortal. Indeed, some have gone on the offensive and argued that helping people is worth the sacrifice only if and because they are mortal, for otherwise they could invariably be compensated in an afterlife (e.g., Wielenberg 2005, 91–94). Another recent and interesting criticism is that the major motivations for the claim that nothing matters now if one day it will end are incoherent (Greene 2021).

A second argument for the view that life would be meaningless without a soul is that it is necessary for justice to be done, which, in turn, is necessary for a meaningful life. Life seems nonsensical when the wicked flourish and the righteous suffer, at least supposing there is no other world in which these injustices will be rectified, whether by God or a Karmic force. Something like this argument can be found in Ecclesiastes, and it continues to be defended (e.g., Davis 1987; Craig 1994). However, even granting that an afterlife is required for perfectly just outcomes, it is far from obvious that an eternal afterlife is necessary for them, and, then, there is the suggestion that some lives, such as Mandela’s, have been meaningful precisely in virtue of encountering injustice and fighting it.

A third argument for thinking that having a soul is essential for any meaning is that it is required to have the sort of free will without which our lives would be meaningless. Immanuel Kant is known for having maintained that if we were merely physical beings, subjected to the laws of nature like everything else in the material world, then we could not act for moral reasons and hence would be unimportant. More recently, one theologian has eloquently put the point in religious terms: “The moral spirit finds the meaning of life in choice. It finds it in that which proceeds from man and remains with him as his inner essence rather than in the accidents of circumstances turns of external fortune....(W)henever a human being rubs the lamp of his moral conscience, a Spirit does appear. This Spirit is God....It is in the ‘Thou must’ of God and man’s ‘I can’ that the divine image of God in human life is contained” (Swenson 1949/2000, 27–28). Notice that, even if moral norms did not spring from God’s commands, the logic of the argument entails that one’s life could be meaningful, so long as one had the inherent ability to make the morally correct choice in any situation. That, in turn, arguably requires something non-physical about one’s self, so as to be able to overcome whichever physical laws and forces one might confront. The standard objection to this reasoning is to advance a compatibilism about having a determined physical nature and being able to act for moral reasons (e.g., Arpaly 2006; Fischer 2009, 145–77). It is also worth wondering whether, if one had to have a spiritual essence in order to make free choices, it would have to be one that never perished.

Like God-centered theorists, many soul-centered theorists these days advance a moderate view, accepting that some meaning in life would be possible without immortality, but arguing that a much greater meaning would be possible with it. Granting that Einstein, Mandela, and Picasso had somewhat meaningful lives despite not having survived the deaths of their bodies (as per, e.g., Trisel 2004; Wolf 2015, 89–140; Landau 2017), there remains a powerful thought: more is better. If a finite life with the good, the true, and the beautiful has meaning in it to some degree, then surely it would have all the more meaning if it exhibited such higher values––including a relationship with God––for an eternity (Cottingham 2016, 132–35; Mawson 2016, 2019, 52–53; Williams 2020, 112–34; cf. Benatar 2017, 35–63). One objection to this reasoning is that the infinity of meaning that would be possible with a soul would be “too big,” rendering it difficult for the moderate supernaturalist to make sense of the intution that a finite life such as Einstein’s can indeed count as meaningful by comparison (Metz 2019, 30–31; cf. Mawson 2019, 53–54). More common, though, is the objection that an eternal life would include anti-meaning of various kinds, such as boredom and repetition, discussed below in the context of extreme naturalism (sub-section 3.3).

3. Naturalism

Recall that naturalism is the view that a physical life is central to life’s meaning, that even if there is no spiritual realm, a substantially meaningful life is possible. Like supernaturalism, contemporary naturalism admits of two distinguishable variants, moderate and extreme (Metz 2019). The moderate version is that, while a genuinely meaningful life could be had in a purely physical universe as known well by science, a somewhat more meaningful life would be possible if a spiritual realm also existed. God or a soul could enhance meaning in life, although they would not be major contributors. The extreme version of naturalism is the view that it would be better in respect of life’s meaning if there were no spiritual realm. From this perspective, God or a soul would be anti-matter, i.e., would detract from the meaning available to us, making a purely physical world (even if not this particular one) preferable.

Cross-cutting the moderate/extreme distinction is that between subjectivism and objectivism, which are theoretical accounts of the nature of meaningfulness insofar as it is physical. They differ in terms of the extent to which the human mind constitutes meaning and whether there are conditions of meaning that are invariant among human beings. Subjectivists believe that there are no invariant standards of meaning because meaning is relative to the subject, i.e., depends on an individual’s pro-attitudes such as her particular desires or ends, which are not shared by everyone. Roughly, something is meaningful for a person if she strongly wants it or intends to seek it out and she gets it. Objectivists maintain, in contrast, that there are some invariant standards for meaning because meaning is at least partly mind-independent, i.e., obtains not merely in virtue of being the object of anyone’s mental states. Here, something is meaningful (partially) because of its intrinsic nature, in the sense of being independent of whether it is wanted or intended; meaning is instead (to some extent) the sort of thing that merits these reactions.

There is logical space for an orthogonal view, according to which there are invariant standards of meaningfulness constituted by what all human beings would converge on from a certain standpoint. However, it has not been much of a player in the field (Darwall 1983, 164–66).

According to this version of naturalism, meaning in life varies from person to person, depending on each one’s variable pro-attitudes. Common instances are views that one’s life is more meaningful, the more one gets what one happens to want strongly, achieves one’s highly ranked goals, or does what one believes to be really important (Trisel 2002; Hooker 2008). One influential subjectivist has recently maintained that the relevant mental state is caring or loving, so that life is meaningful just to the extent that one cares about or loves something (Frankfurt 1988, 80–94, 2004). Another recent proposal is that meaningfulness consists of “an active engagement and affirmation that vivifies the person who has freely created or accepted and now promotes and nurtures the projects of her highest concern” (Belliotti 2019, 183).

Subjectivism was dominant in the middle of the twentieth century, when positivism, noncognitivism, existentialism, and Humeanism were influential (Ayer 1947; Hare 1957; Barnes 1967; Taylor 1970; Williams 1976). However, in the last quarter of the twentieth century, inference to the best explanation and reflective equilibrium became accepted forms of normative argumentation and were frequently used to defend claims about the existence and nature of objective value (or of “external reasons,” ones obtaining independently of one’s extant attitudes). As a result, subjectivism about meaning lost its dominance. Those who continue to hold subjectivism often remain suspicious of attempts to justify beliefs about objective value (e.g., Trisel 2002, 73, 79, 2004, 378–79; Frankfurt 2004, 47–48, 55–57; Wong 2008, 138–39; Evers 2017, 32, 36; Svensson 2017, 54). Theorists are moved to accept subjectivism typically because the alternatives are unpalatable; they are reasonably sure that meaning in life obtains for some people, but do not see how it could be grounded on something independent of the mind, whether it be the natural or the supernatural (or the non-natural). In contrast to these possibilities, it appears straightforward to account for what is meaningful in terms of what people find meaningful or what people want out of their lives. Wide-ranging meta-ethical debates in epistemology, metaphysics, and the philosophy of language are necessary to address this rationale for subjectivism.

There is a cluster of other, more circumscribed arguments for subjectivism, according to which this theory best explains certain intuitive features of meaning in life. For one, subjectivism seems plausible since it is reasonable to think that a meaningful life is an authentic one (Frankfurt 1988, 80–94). If a person’s life is significant insofar as she is true to herself or her deepest nature, then we have some reason to believe that meaning simply is a function of those matters for which the person cares. For another, it is uncontroversial that often meaning comes from losing oneself, i.e., in becoming absorbed in an activity or experience, as opposed to being bored by it or finding it frustrating (Frankfurt 1988, 80–94; Belliotti 2019, 162–70). Work that concentrates the mind and relationships that are engrossing seem central to meaning and to be so because of the subjective elements involved. For a third, meaning is often taken to be something that makes life worth continuing for a specific person, i.e., that gives her a reason to get out of bed in the morning, which subjectivism is thought to account for best (Williams 1976; Svensson 2017; Calhoun 2018).

Critics maintain that these arguments are vulnerable to a common objection: they neglect the role of objective value (or an external reason) in realizing oneself, losing oneself, and having a reason to live (Taylor 1989, 1992; Wolf 2010, 2015, 89–140). One is not really being true to oneself, losing oneself in a meaningful way, or having a genuine reason to live insofar as one, say, successfully maintains 3,732 hairs on one’s head (Taylor 1992, 36), cultivates one’s prowess at long-distance spitting (Wolf 2010, 104), collects a big ball of string (Wolf 2010, 104), or, well, eats one’s own excrement (Wielenberg 2005, 22). The counterexamples suggest that subjective conditions are insufficient to ground meaning in life; there seem to be certain actions, relationships, and states that are objectively valuable (but see Evers 2017, 30–32) and toward which one’s pro-attitudes ought to be oriented, if meaning is to accrue.

So say objectivists, but subjectivists feel the pull of the point and usually seek to avoid the counterexamples, lest they have to bite the bullet by accepting the meaningfulness of maintaining 3,732 hairs on one’s head and all the rest (for some who do, see Svensson 2017, 54–55; Belliotti 2019, 181–83). One important strategy is to suggest that subjectivists can avoid the counterexamples by appealing to the right sort of pro-attitude. Instead of whatever an individual happens to want, perhaps the relevant mental state is an emotional-perceptual one of seeing-as (Alexis 2011; cf. Hosseini 2015, 47–66), a “categorical” desire, that is, an intrinsic desire constitutive of one’s identity that one takes to make life worth continuing (Svensson 2017), or a judgment that one has a good reason to value something highly for its own sake (Calhoun 2018). Even here, though, objectivists will argue that it might “appear that whatever the will chooses to treat as a good reason to engage itself is, for the will, a good reason. But the will itself....craves objective reasons; and often it could not go forward unless it thought it had them” (Wiggins 1988, 136). And without any appeal to objectivity, it is perhaps likely that counterexamples would resurface.

Another subjectivist strategy by which to deal with the counterexamples is the attempt to ground meaningfulness, not on the pro-attitudes of an individual valuer, but on those of a group (Darwall 1983, 164–66; Brogaard and Smith 2005; Wong 2008). Does such an intersubjective move avoid (more of) the counterexamples? If so, does it do so more plausibly than an objective theory?

Objective naturalists believe that meaning in life is constituted at least in part by something physical beyond merely the fact that it is the object of a pro-attitude. Obtaining the object of some emotion, desire, or judgment is not sufficient for meaningfulness, on this view. Instead, there are certain conditions of the material world that could confer meaning on anyone’s life, not merely because they are viewed as meaningful, wanted for their own sake, or believed to be choiceworthy, but instead (at least partially) because they are inherently worthwhile or valuable in themselves.

Morality (the good), enquiry (the true), and creativity (the beautiful) are widely held instances of activities that confer meaning on life, while trimming toenails and eating snow––along with the counterexamples to subjectivism above––are not. Objectivism is widely thought to be a powerful general explanation of these particular judgments: the former are meaningful not merely because some agent (whether it is an individual, her society, or even God) cares about them or judges them to be worth doing, while the latter simply lack significance and cannot obtain it even if some agent does care about them or judge them to be worth doing. From an objective perspective, it is possible for an individual to care about the wrong thing or to be mistaken that something is worthwhile, and not merely because of something she cares about all the more or judges to be still more choiceworthy. Of course, meta-ethical debates about the existence and nature of value are again relevant to appraising this rationale.

Some objectivists think that being the object of a person’s mental states plays no constitutive role in making that person’s life meaningful, although they of course contend that it often plays an instrumental role––liking a certain activity, after all, is likely to motivate one to do it. Relatively few objectivists are “pure” in that way, although consequentialists do stand out as clear instances (e.g., Singer 1995; Smuts 2018, 75–99). Most objectivists instead try to account for the above intuitions driving subjectivism by holding that a life is more meaningful, not merely because of objective factors, but also in part because of propositional attitudes such as cognition, conation, and emotion. Particularly influential has been Susan Wolf’s hybrid view, captured by this pithy slogan: “Meaning arises when subjective attraction meets objective attractiveness” (Wolf 2015, 112; see also Kekes 1986, 2000; Wiggins 1988; Raz 2001, 10–40; Mintoff 2008; Wolf 2010, 2016; Fischer 2019, 9–23; Belshaw 2021, 160–81). This theory implies that no meaning accrues to one’s life if one believes in, is satisfied by, or cares about a project that is not truly worthwhile, or if one takes up a truly worthwhile project but fails to judge it important, be satisfied by it, or care about it. A related approach is that, while subjective attraction is not necessary for meaning, it could enhance it (e.g., Audi 2005, 344; Metz 2013, 183–84, 196–98, 220–25). For instance, a stereotypical Mother Teresa who is bored by and alienated from her substantial charity work might have a somewhat significant existence because of it, even if she would have an even more significant existence if she felt pride in it or identified with it.

There have been several attempts to capture theoretically what all objectively attractive, inherently worthwhile, or finally valuable conditions have in common insofar as they bear on meaning in a person’s life. Over the past few decades, one encounters the proposals that objectively meaningful conditions are just those that involve: positively connecting with organic unity beyond oneself (Nozick 1981, 594–619); being creative (Taylor 1987; Matheson 2018); living an emotional life (Solomon 1993; cf. Williams 2020, 56–78); promoting good consequences, such as improving the quality of life of oneself and others (Singer 1995; Audi 2005; Smuts 2018, 75–99); exercising or fostering rational nature in exceptional ways (Smith 1997, 179–221; Gewirth 1998, 177–82; Metz 2013, 222–36); progressing toward ends that can never be fully realized because one’s knowledge of them changes as one approaches them (Levy 2005); realizing goals that are transcendent for being long-lasting in duration and broad in scope (Mintoff 2008); living virtuously (May 2015, 61–138; McPherson 2020); and loving what is worth loving (Wolf 2016). There is as yet no convergence in the field on one, or even a small cluster, of these accounts.

One feature of a large majority of the above naturalist theories is that they are aggregative or additive, objectionably treating a life as a mere “container” of bits of life that are meaningful considered in isolation from other bits (Brännmark 2003, 330). It has become increasingly common for philosophers of life’s meaning, especially objectivists, to hold that life as a whole, or at least long stretches of it, can substantially affect its meaningfulness beyond the amount of meaning (if any) in its parts.

For instance, a life that has lots of beneficence and otherwise intuitively meaning-conferring conditions but that is also extremely repetitive (à la the movie Groundhog Day ) is less than maximally meaningful (Taylor 1987; Blumenfeld 2009). Furthermore, a life that not only avoids repetition but also ends with a substantial amount of meaningful (or otherwise desirable) parts seems to have more meaning overall than one that has the same amount of meaningful (desirable) parts but ends with few or none of them (Kamm 2013, 18–22; Dorsey 2015). Still more, a life in which its meaningless (or otherwise undesirable parts) cause its meaningful (desirable) parts to come about through a process of personal growth seems meaningful in virtue of this redemptive pattern, “good life-story,” or narrative self-expression (Taylor 1989, 48–51; Wong 2008; Fischer 2009, 145–77; Kauppinen 2012; May 2015, 61–138; Velleman 2015, 141–73). These three cases suggest that meaning can inhere in life as a whole, that is, in the relationships between its parts, and not merely in the parts considered in isolation. However, some would maintain that it is, strictly speaking, the story that is or could be told of a life that matters, not so much the life-story qua relations between events themselves (de Bres 2018).

There are pure or extreme versions of holism present in the literature, according to which the only possible bearer of meaning in life is a person’s life as a whole, and not any isolated activities, relationships, or states (Taylor 1989, 48–51; Tabensky 2003; Levinson 2004). A salient argument for this position is that judgments of the meaningfulness of a part of someone’s life are merely provisional, open to revision upon considering how they fit into a wider perspective. So, for example, it would initially appear that taking an ax away from a madman and thereby protecting innocent parties confers some meaning on one’s life, but one might well revise that judgment upon learning that the intention behind it was merely to steal an ax, not to save lives, or that the madman then took out a machine gun, causing much more harm than his ax would have. It is worth considering how far this sort of case is generalizable, and, if it can be to a substantial extent, whether that provides strong evidence that only life as a whole can exhibit meaningfulness.

Perhaps most objectivists would, at least upon reflection, accept that both the parts of a life and the whole-life relationships among the parts can exhibit meaning. Supposing there are two bearers of meaning in a life, important questions arise. One is whether a certain narrative can be meaningful even if its parts are not, while a second is whether the meaningfulness of a part increases if it is an aspect of a meaningful whole (on which see Brännmark 2003), and a third is whether there is anything revealing to say about how to make tradeoffs between the parts and whole in cases where one must choose between them (Blumenfeld 2009 appears to assign lexical priority to the whole).

Naturalists until recently had been largely concerned to show that meaning in life is possible without God or a soul; they have not spent much time considering how such spiritual conditions might enhance meaning, but have, in moderate fashion, tended to leave that possibility open (an exception is Hooker 2008). Lately, however, an extreme form of naturalism has arisen, according to which our lives would probably, if not unavoidably, have less meaning in a world with God or a soul than in one without. Although such an approach was voiced early on by Baier (1957), it is really in the past decade or so that this “anti-theist” position has become widely and intricately discussed.

One rationale, mentioned above as an objection to the view that God’s purpose constitutes meaning in life, has also been deployed to argue that the existence of God as such would necessarily reduce meaning, that is, would consist of anti-matter. It is the idea that master/servant and parent/child analogies so prominent in the monotheist religious traditions reveal something about our status in a world where there is a qualitatively higher being who has created us with certain ends in mind: our independence or dignity as adult persons would be violated (e.g., Baier 1957/2000, 118–20; Kahane 2011, 681–85; Lougheed 2020, 121–41). One interesting objection to this reasoning has been to accept that God’s existence is necessarily incompatible with the sort of meaning that would come (roughly stated) from being one’s own boss, but to argue that God would also make greater sorts of meaning available, offering a net gain to us (Mawson 2016, 110–58).

Another salient argument for thinking that God would detract from meaning in life appeals to the value of privacy (Kahane 2011, 681–85; Lougheed 2020, 55–110). God’s omniscience would unavoidably make it impossible for us to control another person’s access to the most intimate details about ourselves, which, for some, amounts to a less meaningful life than one with such control. Beyond questioning the value of our privacy in relation to God, one thought-provoking criticism has been to suggest that, if a lack of privacy really would substantially reduce meaning in our lives, then God, qua morally perfect person, would simply avoid knowing everything about us (Tooley 2018). Lacking complete knowledge of our mental states would be compatible with describing God as “omniscient,” so the criticism goes, insofar as that is plausibly understood as having as much knowledge as is morally permissible.

Turn, now, to major arguments for thinking that having a soul would reduce life’s meaning, so that if one wants a maximally meaningful life, one should prefer a purely physical world, or at least one in which people are mortal. First and foremost, there has been the argument that an immortal life could not avoid becoming boring (Williams 1973), rendering life pointless according to many subjective and objective theories. The literature on this topic has become enormous, with the central reply being that immortality need not get boring (for more recent discussions, see Fischer 2009, 79–101, 2019, 117–42; Mawson 2019, 51–52; Williams 2020, 30–41, 123–29; Belshaw 2021, 182–97). However, it might also be worth questioning whether boredom is sufficient for meaninglessness. Suppose, for instance, that one volunteers to be bored so that many others will not be bored; perhaps this would be a meaningful sacrifice to make. Being bored for an eternity would not be blissful or even satisfying, to be sure, but if it served the function of preventing others from being bored for an eternity, would it be meaningful (at least to some degree)? If, as is commonly held, sacrificing one’s life could be meaningful, why not also sacrificing one’s liveliness?

Another reason given to reject eternal life is that it would become repetitive, which would substantially drain it of meaning (Scarre 2007, 54–55; May 2009, 46–47, 64–65, 71; Smuts 2011, 142–44; cf. Blumenfeld 2009). If, as it appears, there are only a finite number of actions one could perform, relationships one could have, and states one could be in during an eternity, one would have to end up doing the same things again. Even though one’s activities might be more valuable than rolling a stone up a hill forever à la Sisyphus, the prospect of doing them over and over again forever is disheartening for many. To be sure, one might not remember having done them before and hence could avoid boredom, but for some philosophers that would make it all the worse, akin to having dementia and forgetting that one has told the same stories. Others, however, still find meaning in such a life (e.g., Belshaw 2021, 197, 205n41).

A third meaning-based argument against immortality invokes considerations of narrative. If the pattern of one’s life as a whole substantially matters, and if a proper pattern would include a beginning, a middle, and an end, it appears that a life that never ends would lack the relevant narrative structure. “Because it would drag on endlessly, it would, sooner or later, just be a string of events lacking all form....With immortality, the novel never ends....How meaningful can such a novel be?” (May 2009, 68, 72; see also Scarre 2007, 58–60). Notice that this objection is distinct from considerations of boredom and repetition (which concern novelty ); even if one were stimulated and active, and even if one found a way not to repeat one’s life in the course of eternity, an immortal life would appear to lack shape. In reply, some reject the idea that a meaningful life must be akin to a novel, and intead opt for narrativity in the form of something like a string of short stories that build on each other (Fischer 2009, 145–77, 2019, 101–16). Others, though, have sought to show that eternity could still be novel-like, deeming the sort of ending that matters to be a function of what the content is and how it relates to the content that came before (e.g., Seachris 2011; Williams 2020, 112–19).

There have been additional objections to immortality as undercutting meaningfulness, but they are prima facie less powerful than the previous three in that, if sound, they arguably show that an eternal life would have a cost, but probably not one that would utterly occlude the prospect of meaning in it. For example, there have been the suggestions that eternal lives would lack a sense of preciousness and urgency (Nussbaum 1989, 339; Kass 2002, 266–67), could not exemplify virtues such as courageously risking one’s life for others (Kass 2002, 267–68; Wielenberg 2005, 91–94), and could not obtain meaning from sustaining or saving others’ lives (Nussbaum 1989, 338; Wielenberg 2005, 91–94). Note that at least the first two rationales turn substantially on the belief in immortality, not quite immortality itself: if one were immortal but forgot that one is or did not know that at all, then one could appreciate life and obtain much of the virtue of courage (and, conversely, if one were not immortal, but thought that one is, then, by the logic of these arguments, one would fail to appreciate limits and be unable to exemplify courage).

The previous two sections addressed theoretical accounts of what would confer meaning on a human person’s life. Although these theories do not imply that some people’s lives are in fact meaningful, that has been the presumption of a very large majority of those who have advanced them. Much of the procedure has been to suppose that many lives have had meaning in them and then to consider in virtue of what they have or otherwise could. However, there are nihilist (or pessimist) perspectives that question this supposition. According to nihilism (pessimism), what would make a life meaningful in principle cannot obtain for any of us.

One straightforward rationale for nihilism is the combination of extreme supernaturalism about what makes life meaningful and atheism about whether a spiritual realm exists. If you believe that God or a soul is necessary for meaning in life, and if you believe that neither is real, then you are committed to nihilism, to the denial that life can have any meaning. Athough this rationale for nihilism was prominent in the modern era (and was more or less Camus’ position), it has been on the wane in analytic philosophical circles, as extreme supernaturalism has been eclipsed by the moderate variety.

The most common rationales for nihilism these days do not appeal to supernaturalism, or at least not explicitly. One cluster of ideas appeals to what meta-ethicists call “error theory,” the view that evaluative claims (in this case about meaning in life, or about morality qua necessary for meaning) characteristically posit objectively real or universally justified values, but that such values do not exist. According to one version, value judgments often analytically include a claim to objectivity but there is no reason to think that objective values exist, as they “would be entities or qualities or relations of a very strange sort, utterly different from anything else in the universe” (Mackie 1977/1990, 38). According to a second version, life would be meaningless if there were no set of moral standards that could be fully justified to all rational enquirers, but it so happens that such standards cannot exist for persons who can always reasonably question a given claim (Murphy 1982, 12–17). According to a third, we hold certain beliefs about the objectivity and universality of morality and related values such as meaning because they were evolutionarily advantageous to our ancestors, not because they are true. Humans have been “deceived by their genes into thinking that there is a distinterested, objective morality binding upon them, which all should obey” (Ruse and Wilson 1986, 179; cf. Street 2015). One must draw on the intricate work in meta-ethics that has been underway for the past several decades in order to appraise these arguments.

In contrast to error-theoretic arguments for nihilism, there are rationales for it accepting that objective values exist but denying that our lives can ever exhibit or promote them so as to obtain meaning. One version of this approach maintains that, for our lives to matter, we must be in a position to add objective value to the world, which we are not since the objective value of the world is already infinite (Smith 2003). The key premises for this view are that every bit of space-time (or at least the stars in the physical universe) have some positive value, that these values can be added up, and that space is infinite. If the physical world at present contains an infinite degree of value, nothing we do can make a difference in terms of meaning, for infinity plus any amount of value remains infinity. One way to question this argument, beyond doubting the value of space-time or stars, is to suggest that, even if one cannot add to the value of the universe, meaning plausibly comes from being the source of certain values.