Article 21: Understanding The Right to Life and Personal Liberty from Case Laws-Academike Explainer

Article 21 (and its many interpretations) is the perfect example of the transformative character of the Constitution of India. The Indian judiciary has attributed wider connotation and meaning to Article 21, extending beyond the Constitution makers’ imagination. These meanings derived from the ‘right to life’ present unique complexities. It is impossible to understand the expansive jurisprudence on Article 21 within the length of this piece. Therefore, Riya Jain understands the various components of freedom that stem from the ‘right to life’. She presents a straightforward and comprehensive explainer on the case laws that have interpreted the right.

By Riya Jain, UILS Panjab University.

*The piece was first published by Riya in 2015, this is the updated form.

Introduction of Article 21

Article 21 of Indian constitution reads:

“No person shall be deprived of his life or personal liberty except according to a procedure established by law.”

In Francis Coralie Mullin vs The Administrator (1981), Justice P. Bhagwati had said that Article 21 ’embodies a constitutional value of supreme importance in a democratic society’. Further, Justice Iyer characterised Article 21 as ‘the procedural Magna Carta protective of life and liberty’.

Article 21 is at the heart of the Constitution . It is the most organic and progressive provision in our living Constitution. Article 21 can only be claimed when a person is deprived of his ‘life or ‘personal liberty’ by the ‘State’ as defined in Article 12. Thus, violation of the right by private individuals is not within the preview of Article 21.

Article 21 secures two rights:

1) Right to life, and

2) Right to personal liberty.

It prohibits the deprivation of the above rights except according to a procedure established by law. Article 21 corresponds to the Magna Carta of 1215, the Fifth Amendment to the American Constitution, Article 40(4) of Eire 1937, and Article XXXI of the Constitution of Japan, 1946.

It is also fundamental to democracy as it extends to natural persons and not just citizens. The right is available to every person, citizen or alien. Thus, even a foreigner can claim this right. It, however, does not entitle a foreigner to the right to reside and settle in India, as mentioned in Article 19 (1) (e).

This Article is an all tell for Article 21. The first part will understand the meaning and concept of ‘right to life’ as understood by the judiciary. Further, the piece will lay out how several violations of the body, reputation and equality have been understood and brought under the purview of the right to life and the right to live with dignity.

Meaning, Concept and Interpretation of ‘Right to Life’ under Article 21

‘Everyone has the right to life, liberty and the security of person.’

The right to life is undoubtedly the most fundamental of all rights. All other rights add quality to the life in question and depend on the pre-existence of life itself for their operation. As human rights can only attach to living beings, one might expect the right to life itself to be in some sense primary since none of the other rights would have any value or utility without it. There would have been no Fundamental Rights worth mentioning if Article 21 had been interpreted in its original sense. This Section will examine the right to life as interpreted and applied by the Supreme Court of India.

Article 21 of the Constitution of India , 1950 provides,

“No person shall be deprived of his life or personal liberty except according to procedure established by law.”

‘Life’ in Article 21 of the Constitution is not merely the physical act of breathing. It does not connote mere animal existence or continued drudgery through life. It has a much wider, including, including the right to live with human dignity, Right to livelihood, Right to health, Right to pollution-free air, etc.

The right to life is fundamental to our very existence, without which we cannot live as human beings and includes all those aspects of life, which make a man’s life meaningful, complete, and worth living. It is the only Article in the Constitution that has received the broadest possible interpretation. Thus, the bare necessities, minimum and basic requirements for a person from the core concept of the right to life.

In Kharak Singh v. State of Uttar Pradesh [i] , the Supreme Court quoted and held:

By the term ‘life’ as here used, something more is meant than mere animal existence. The inhibition against its deprivation extends to all those limbs and faculties by which life is enjoyed. The provision equally prohibits the mutilation of the body by amputation of an armored leg or the pulling out of an eye, or the destruction of any other organ of the body through which the soul communicates with the outer world.

In Sunil Batra v. Delhi Administration [ii] , the Supreme Court approved the above observations. It held that the ‘right to life’ included the right to lead a healthy life to enjoy all faculties of the human body in their prime conditions. It would even include the right to protect a person’s tradition, culture, heritage and all that gives meaning to a man’s life. In addition, it consists of the Right to live and sleep in peace and the Right to repose and health.

Right To Live with Human Dignity

In Maneka Gandhi v. Union of India [iii] , the Supreme Court gave a new dimension to Art. 21. The Court held that the right to live is not merely a physical right but includes within its ambit the right to live with human dignity. Elaborating the same view, the Court in Francis Coralie v. Union Territory of Delhi [iv] observed:

“The right to live includes the right to live with human dignity and all that goes along with it, viz., the bare necessities of life such as adequate nutrition, clothing and shelter over the head and facilities for reading writing and expressing oneself in diverse forms, freely moving about and mixing and mingling with fellow human beings and must include the right to basic necessities the basic necessities of life and also the right to carry on functions and activities as constitute the bare minimum expression of human self.”

Another broad formulation of life to dignity is found in Bandhua Mukti Morcha v. Union of India [v] . Characterising Art. 21 as the heart of fundamental rights, the Court gave it an expanded interpretation. Bhagwati J. observed:

“It is the fundamental right of everyone in this country… to live with human dignity free from exploitation. This right to live with human dignity enshrined in Article 21 derives its life breath from the Directive Principles of State Policy and particularly clauses (e) and (f) of Article 39 and Articles 41 and 42 and at the least, therefore, it must include protection of the health and strength of workers, men and women, and of the tender age of children against abuse, opportunities and facilities for children to develop in a healthy manner and in conditions of freedom and dignity, educational facilities, just and humane conditions of work and maternity relief. “These are the minimum requirements which must exist in order to enable a person to live with human dignity and no State neither the Central Government nor any State Government-has the right to take any action which will deprive a person of the enjoyment of these basic essentials.”

Following the above-stated cases, the Supreme Court in Peoples Union for Democratic Rights v. Union of India [vi] , held that non-payment of minimum wages to the workers employed in various Asiad Projects in Delhi was a denial to them of their right to live with basic human dignity and violative of Article 21 of the Constitution.

Bhagwati J. held that rights and benefits conferred on workmen employed by a contractor under various labour laws are intended to ensure basic human dignity to workers. He held that the non-implementation by the private contractors engaged for constructing a building for holding Asian Games in Delhi, and non-enforcement of these laws by the State Authorities of the provisions of these laws was held to be violative of the fundamental right of workers to live with human dignity contained in Art. 21 [vii] .

In Chandra Raja Kumar v. Police Commissioner Hyderabad [viii] , it has been held that the right to life includes the right to live with human dignity and decency. Therefore, keeping of beauty contest is repugnant to the dignity or decency of women and offends Article 21 of the Constitution only if the same is grossly indecent, scurrilous, obscene or intended for blackmailing. Therefore, the government is empowered to prohibit the contest as objectionable performance under Section 3 of the Andhra Pradesh Objectionable Performances Prohibition Act, 1956.

In State of Maharashtra v. Chandrabhan [ix] , the Court struck down a provision of Bombay Civil Service Rules, 1959. Thi provision provided for payment of only a nominal subsistence allowance of Re. 1 per month to a suspended government servant upon his conviction during the pendency of his appeal as unconstitutional on the ground that it was violative of Article 21 of the Constitution.

Right Against Sexual Harassment at Workplace

Sexual harassment of women has been held by the Supreme Court to be violative of the most cherished of the fundamental rights, namely, the Right to Life contained in Art. 21.

“The meaning and content of the fundamental rights guaranteed in the Constitution of India are of sufficient amplitude to compass all the facets of gender equality including prevention of sexual harassment or abuse. “

The above statement by Justice Verma in the famous Vishakha judgment liberalised the understanding of Article 21. Therefore, making it even more emancipatory.

In Vishakha v. State of Rajasthan [x] , the Supreme Court declared sexual harassment at the workplace to violate the right to equality, life and liberty. Therefore, a violation of Articles 14, 15 and 21 of the Constitution.

In this case, in the absence of a relevant law against sexual harassment, the Supreme Court laid down the following guidelines to ensure gender parity in the workplace:

This meant that all employers or persons in charge of the workplace, whether in the public or private sector, should take appropriate steps to prevent sexual harassment.

- Express prohibition of sexual harassment as defined above at the workplace should be notified, published and circulated inappropriate ways.

- The Rules/Regulations of Government and Public Sector bodies relating to conduct and discipline should include rules/regulations prohibiting sexual harassment and provide for appropriate penalties in such rules against the offender.

- As regards private employers steps should be taken to include the prohibitions above in the standing orders under the Industrial Employment (Standing Orders) Act, 1946.

- Appropriate work conditions should be provided for work, leisure, health, and hygiene to ensure that there is no hostile environment towards women at workplaces. No employee woman should have reasonable grounds to believe that she is disadvantaged in connection with her employment.

- Where such conduct amounts to specific offences under IPC or under any other law, the employer shall initiate appropriate action by making a complaint with the appropriate authority.

- The victims of Sexual harassment should have the option to seek the transfer of the perpetrator or their own transfer.

In Apparel Export Promotion Council v. A.K. Chopra [xi] , the Supreme Court reiterated the Vishakha ruling and observed that:

“There is no gainsaying that each incident of sexual harassment, at the place of work, results in the violation of the Fundamental Right to Gender Equality and the Right to Life and Liberty the two most precious Fundamental Rights guaranteed by the Constitution of India…. “In our opinion, the contents of the fundamental rights guaranteed in our Constitution are of sufficient amplitude to encompass all facets of gender equality, including prevention of sexual harassment and abuse and the courts are under a constitutional obligation to protect and preserve those fundamental rights. That sexual harassment of a female at the place of work is incompatible with the dignity and honour of a female and needs to be eliminated….”

Understanding Article 21 Through Against Sexual Assault and Rape

Rape has been held to be a violation of a person’s fundamental life guaranteed under Article 21. Therefore, the right to life would include all those aspects of life that go on to make life meaningful, complete and worth living.

In Bodhisattwa Gautam v. Subhra Chakraborty [xii] , the Supreme Court observed:

“Rape is thus not only a crime against the person of a woman (victim), it is a crime against the entire society. It destroys the entire psychology of a woman and pushed her into deep emotional crises. It is only by her sheer will power that she rehabilitates herself in the society, which, on coming to know of the rape, looks down upon her in derision and contempt. Rape is, therefore, the most hated crime. It is a crime against basic human rights and is also violative of the victim’s most cherished of the fundamental rights, namely, the right to life with human dignity contained in Art 21”.

Right to Reputation and Article 21

Reputation is an essential part of one’s life. It is one of the finer graces of human civilisation that makes life worth living. The Supreme Court referred to D.F. Marion v. Minnie Davis [xiii] in Smt. Kiran Bedi v. Committee of Inquiry [xiv] . It said:

“good reputation was an element of personal security and was protected by the Constitution, equally with the right to the enjoyment of life, liberty, and property. The Court affirmed that the right to enjoyment of life, liberty, and property. The Court affirmed that the right to enjoyment of private reputation was of ancient origin and was necessary to human society.”

The same American decision has also been referred to in State of Maharashtra v. Public Concern of Governance Trust [xv]. The Court held that good reputation was an element of personal security and was protected by the Constitution, equally with the right to enjoy life, liberty and property.

It has been held that the right equally covers a person’s reputation during and after his death. Thus, any wrong action of the state or agencies that sullies the reputation of a virtuous person would undoubtedly come under the scope of Article 21.

State of UP v. Mohammaad Naim [xvi] succinctly laid down the following tests while dealing the question of expunction of disgracing remarks against a person or authority whose conduct comes in consideration before a court of law. These are:

- whether the party whose conduct is in question is before the Court or has an opportunity of explaining or defending himself.

- whether there is evidence on record bearing on that conduct justifying the remarks.

- Whether it is necessary for the decision of the case, as an integral part thereof, to animadvert on that conduct, it has also been recognised that judicial pronouncements must be judicial. It should not normally depart from sobriety, moderation, and reserve.

In State of Bihar v. Lal Krishna Advani [xvii] , a two-member commission got appointed to inquire into the communal disturbances in the Bhagalpur district on October 24, 1989. The commission made certain remarks in the report, which impinged upon the respondent’s reputation as a public man without allowing him to be heard. The Apex Court ruled that it was amply clear that one was entitled to have and preserve one’s reputation, and one also had the right to protect it.

The Court further said that if any authority, in the discharge of its duties fastened upon it under the law, transverse into the realm of personal reputation adversely affecting him, it must provide a chance to have his say in the matter. Finally, the Court observed that the principle of natural justice made it incumbent upon the authority to allow the person before any comment was made or opinion was expressed, likely to affect that person prejudicially.

Right To Livelihood

To begin with, the Supreme Court took the view that the right to life in Art. 21 would not include the right to livelihood. In Re Sant Ram [xviii] , a case arose before the Maneka Gandhi case, where the Supreme Court ruled that the right to livelihood would not fall within the expression ‘life’ in Article 21. The Court said curtly:

“The Right to livelihood would be included in the freedoms enumerated in Art.19, or even in Art.16, in a limited sense. But the language of Art.21 cannot be pressed into aid of the argument that the word ‘life’ in Art. 21 includes ‘livelihood’ also.”

But then the view changed. The definition of the word ‘life’ in Article 21 was read broadly. The Court, in Board of Trustees of the Port of Bombay v. Dilipkumar Raghavendranath Nandkarni [xix] , came to hold that ‘the right to life’ guaranteed by Article 21 includes ‘the right to livelihood’.

The Olga Tellis v. Bombay Municipal Corporation [xx] , popularly known as the ‘Pavement Dwellers Case’, is important. Herein, a five-judge bench of the Court implied that the right to livelihood is borne out of the right to life. It said so as no person can live without the means of living, that is, the means of livelihood. The Court further observed:

“The sweep of the right to life conferred by Art.21 is wide and far-reaching. It does not mean, merely that life cannot be extinguished or taken away as, for example, by the imposition and execution of death sentence, except according to procedure established by law. That is but one aspect of the right to life. An equally important facet of the right to life is the right to livelihood because no person can live without the means of livelihood.”

If the right to livelihood is not treated as part and parcel of the constitutional right to life, the easiest way of depriving a person of his right to life would be to deprive him of his means of livelihood to the point of abrogation [xxi] .

In the instant case, the Court further opined:

“The state may not by affirmative action, be compelled to provide adequate means of livelihood or work to the citizens. But, any person who is deprived of his right to livelihood except according to just and fair procedure established by law can challenge the deprivation as offending the right to life conferred in Article 21.”

Emphasising upon the close relationship of life and livelihood, the Court stated:

“That, which alone makes it impossible to live, leave aside what makes life livable, must be deemed to be an integral part of the right to life. Deprive a person from his right to livelihood and you shall have deprived him of his life [xxii] .”

Article 21 does not place an absolute embargo on the deprivation of life or personal liberty and, for that matter, on the right to livelihood. What Article 21 insists is that such lack ought to be according to procedure established by law which must be fair, just and reasonable. Therefore, anyone deprived of the right to livelihood without a just and fair procedure set by law can challenge such deprivation as being against Article 21 and get it declared void [xxiii] .

In DTC v. DTC Mazdoor Congress [xxiv] , the Court was hearing a matter where an employee was laid off by issuing a notice without any reason. The Court held that the same was utterly arbitrary and violative of Article 21.

In M. Paul Anthony v. Bihar Gold Mines Ltd [xxv] , it was held that when a government servant or one in a public undertaking is suspended pending a departmental disciplinary inquiry against him, subsistence allowance must be paid to him. The Court has emphasised that a government servant does not have his right to life and other fundamental rights.

However, if a person is deprived of such a right according to procedure established by law which must be fair, just and reasonable and in the larger interest of people, the plea of deprivation of the right to livelihood under Article 21 is unsustainable.

In Chameli Singh v. State of Uttar Pradesh [xxvi] , the SC held that the state acquired a landowner’s land following the procedure laid down in the relevant law of acquisition. So even though the right to livelihood of the landowner is adversely affected, it is not violated.

The Court opined that the state acquires land in exercising its power of eminent domain for a public purpose. The landowner is paid compensation in place of land. Therefore, the plea of deprivation of the right to livelihood under Art. 21 is unsustainable.

In M. J. Sivani v. State of Karnataka & Ors [xxvii] , the Supreme Court held that the right to life under Article 21 does protect livelihood. However, the Court added a rider that its deprivation could not be extended too far or projected or stretched to the recreation, business or trade detrimental to the public interest or has an insidious effect on public moral or public order.

The Court further held that regulating video games of pure chance or mixed chance and skill are not violative of Article 21, nor is the procedure unreasonable, unfair or unjust.

An important case that needs to be mentioned when speaking about the right to livelihood is MX of Bombay Indian Inhabitants v. M/s. ZY [xxviii]. In this case, the Court had held that a person could not be denied employment if they tested positive for HIV. And they cannot be rendered ‘medically unfit’ owing to the same. In interpreting the right to livelihood, the Court emphasised that the same couldn’t hang on to the fancies of the individuals in authority.

Is Right to Work a Fundamental Right under Article 21?

In Sodan Singh v. New Delhi Municipal Committee [xxix] , the five-judge bench of the Supreme Court distinguished the concept of life and liberty within Art.21 from the right to carry on any trade or business, a fundamental right conferred by Art. 19(1)(g). Regarding the same, the Court held that the right to carry on trade or business is not included in the concept of life and personal liberty. Thus, Article 21 is not attracted in the case of trade and business.

The petitioners in the case were hawkers doing business off the paved roads in Delhi. They had claimed against the Municipal authorities who did not allow former to carry out their business. The hawkers claimed that the refusal to do so violated their Right under Article 21 of the Constitution.

The Court opined that the petitioners had a fundamental right under Article 19(1) (g) to carry on trade or business of their choice. However, they had no right to do so in a particular place. Hence, they couldn’t be permitted to carry on their trade on every road in the city. If the road is not wide enough to conveniently accommodate the traffic on it, no hawking may be permitted at all or permitted once a week.

The Court also held that footpaths, streets or roads are public property intended to several general public and are not meant for private use. However, the Court said that the affected persons could apply for relocation and the concerned authorities were to consider the representation and pass orders thereon. Therefore, the two rights were too remote to be connected.

The Court distinguished the ruling in Olga Tellis v. Bombay Municipal Corporation [xxx]. In the case the Court held:

“in that case, the petitioners were very poor persons who had made pavements their homes existing in the midst of filth and squalor and that they had to stay on the pavements so that they could get odd jobs in the city. It was not the case of a business of selling articles after investing some capital.”

In Secretary, the State of Karnataka v. Umadevi [xxxi] , the Court rejected that right to employment at the present point of time can be included as a fundamental right under Right to Life under Art. 21.

Right to Shelter

In UP Avas Vikas Parishad v. Friends Coop. Housing Society Limited [xxxii] , the right to shelter has been held to be a fundamental right which springs from the right to residence secured under Article 19(1)(e) and the right to life guaranteed under Article 21. The state has to provide facilities and opportunities to build houses to make the right meaningful for the poor. [xxxiii] .

Upholding the importance of the right to a decent environment and a reasonable accommodation in Shantistar Builders v. Narayan Khimalal Totame [xxxiv] , the Court held:

“The Right to life would take within its sweep the right to food, the right to clothing, the right to decent environment and reasonable accommodation to live in. The difference between the need for an animal and a human being for shelter has to be kept in view.

The Court advanced:

“For the animal it is the bare protection of the body, for a human being it has to be a suitable accommodation, which would allow him to grow in every aspect – physical, mental and intellectual. The Constitution aims at ensuring fuller development of every child. That would be possible only if the child is in a proper home. It is not necessary that every citizen must be ensured of living in a well-built comfortable house but a reasonable home, particularly for people in India, can even be a mud-built thatched house or a mud-built fireproof accommodation.”

In Chameli Singh v. State of U P [xxxv] , a three-judge bench of the Supreme Court had considered and held that the right to shelter is a fundamental right available to every citizen. And the same was read into Article 21 of the Constitution. Thus, ‘right to shelter’ was considered encompassing the right to life, making the latter more meaningful. The Court advanced:

“Shelter for a human being, therefore, is not mere protection of his life and limb. It is however where he has opportunities to grow physically, mentally, intellectually and spiritually. Right to shelter, therefore, includes adequate living space, safe and decent structure, clean and decent surroundings, sufficient light, pure air and water, electricity, sanitation and other civic amenities like roads etc. so as to have easy access to his daily avocation. The right to shelter, therefore, does not mean a mere right to a roof over one’s head but right to all the infrastructure necessary to enable them to live and develop as a human being [xxxvi] .”

Right to Social Security and Protection of Family

Right to life covers within its ambit the right to social security and protection of the family. K. Ramaswamy J., in Calcutta Electricity Supply Corporation (India) Ltd. v. Subhash Chandra Bose [xxxvii] , held that right to social and economic justice is a fundamental right under Art. 21. The learned judge explained:

“right to life and dignity of a person and status without means were cosmetic rights. Socio-economic rights were, therefore, basic aspirations for meaning the right to life and that Right to Social Security and Protection of Family were an integral part of the right to life.”

In NHRC v. State of Arunachal Pradesh [xxxviii] (Chakmas Case), the SC said that the state is bound to protect the life and liberty of every human being, be he a citizen or otherwise. Further, it cannot permit anybody or a group of persons to threaten another person or group of persons. No state government worth the name can tolerate such threats from one group of persons to another group of persons. Therefore, the state is duty-bound to protect the threatened group from such assaults. If it fails to do so, it will fail to perform its constitutional as well as statutory obligations.

In Murlidhar Dayandeo Kesekar v. Vishwanath Pande Barde [xxxix] , it was held that the right to economic empowerment of poor, disadvantaged and oppressed Dalits was a fundamental right to make their right of life and dignity of person meaningful.

In Regional Director, ESI Corporation v. Francis De Costa [xl] , the Supreme held that security against sickness and disablement was a fundamental right under Article 21 read with Section 39(e) of the Constitution of India.

In LIC of India v. Consumer Education and Research Centre [xli] , it was further held that right to life and livelihood included right to life insurance policies of LIC of India, but that it must be within the paying capacity and means of the insured.

Further, Surjit Kumar v. State of UP. [xlii] is a crucial case that reads Article 21 as extending protection against honour killing. In the case, a division bench of Allahabad high court took serious note on harassment, ill-treatment, and killing of a person for wanting to get married to a person of another caste or community. The accused justified the harassment and killing, claiming that the victim had brought dishonour to the family. The Court said that such a practice of ‘honor killing’ was a blot on society and inter-caste marriage was not against the law. Therefore, the Court directed the police to take strong measures against the accused.

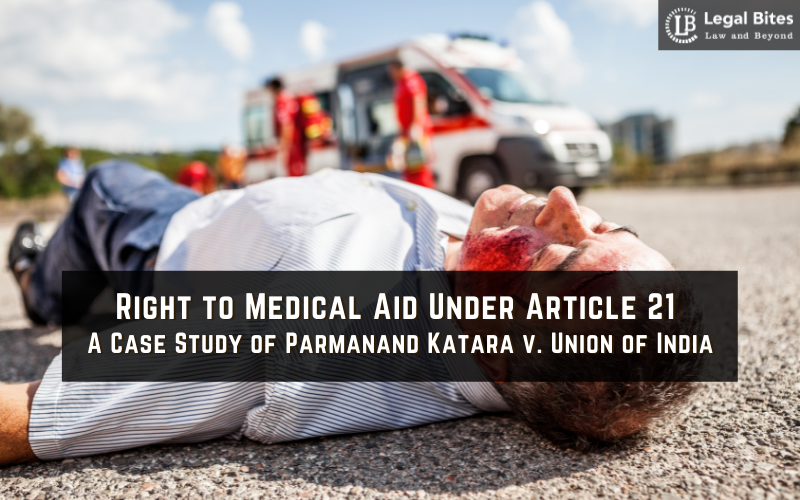

Right to Health and Medical Care

In State of Punjab v. M.S. Chawla [xliii] , it was held that the right to life guaranteed under Article 21 includes within its ‘ambit the right to health and medical care’.

In Vincent v. Union of India , [xliv] the Supreme Court emphasised that a healthy body is the very foundation of all human activities. Further, Article 47, a Directive Principle of State Policy, lays stress note on the improvement of public health and prohibition of drugs detrimental to health as one of the primary duties of the state [xlv] .

In Consumer Education and Research Centre v. Union of India [xlvi] , the Supreme Court laid down:

“Social justice which is a device to ensure life to be meaningful and livable with human dignity requires the state to provide to workmen facilities and opportunities to reach at least minimum standard of health, economic security and civilised living. The health and strength of worker, the Court said, was an important facet of right to life. Denial thereof denudes the workmen the finer facets of life violating Art. 21.”

In Parmananda Katara v. Union of India [xlvii] , the Supreme Court has very specifically clarified that preservation of life is of paramount importance. The Apex Court stated that ‘once life is lost, status quo ante cannot be restored’. [xlviii] It was held that it is the professional obligation of all doctors (government or private) to extent medical aid to the injured immediately to preserve life without legal formalities to be complied with by the police.

Article 21 casts the obligation on the state to preserve life. It is the obligation of those in charge of the community’s health to protect life so that the innocent may be protected and the guilty may be punished. No law can intervene to delay and discharge this paramount obligation of the members of the medical profession.

The Court also observed:

“Art. 21 of the Constitution cast the obligation on the state to preserve life. The patient whether he be an innocent person or a criminal liable to punishment under the laws of the society, it is the obligation of those who are in charge of the health of the community to preserve life so that the innocent may be protected and the guilty may be punished. Social laws do not contemplate death by negligence to tantamount to legal punishment…. Every doctor whether at a Government hospital or otherwise has the professional obligation to extend his services with due expertise for protecting life.”

This link between the right to medical care and health and Article 21 played out most vividly during the pandemic. Especially since the state couldn’t manage the crisis and many people were left to fend for themselves.

To read about the right to health and Article 21, click here

Coming back to understanding the right to medical care pre-covid era, another case that understands this interlink better is Paschim Banga Khet Mazdoor Samity v. State of West Bengal. [xlix] In this case, a person suffering from severe head injuries from a train accident was refused treatment at various hospitals on the excuse that they lacked the adequate facilities and infrastructure to provide treatment.

Through this case, the Supreme Court developed the right to emergency treatment. The Court went on to say that the failure on the part of the government hospital to provide timely medical treatment to a person in need of such treatment results in the violation of his right to life guaranteed under Article 21.

It acknowledged the limitation of financial resources to give effect to such a right. Still, it maintained that the state needed to provide for the resources to give effect to the people’s entitlement of receiving emergency medical treatment [l] .

It has been reiterated, time and again, that there should be no impediment to providing emergency medical care. Again, in Pravat Kumar Mukherjee v. Ruby General Hospital & Others [li] , it was held that a hospital is duty-bound to accept accident victims and patients who are in critical condition and that it cannot refuse treatment on the ground that the victim is not in a position to pay the fee or meet the expenses or on the ground that there is no close relation of the victim available who can give consent for medical treatment [lii] .

The Court has laid stress on a crucial point, viz., the state cannot plead lack of financial resources to carry out these directions meant to provide adequate medical services to the people. The state cannot avoid its constitutional obligation to provide adequate medical assistance to people on account of financial constraints.

But, in State of Punjab v. Ram Lubhaya Bagga [liii] , the Supreme Court recognised that provision of health facilities could not be unlimited. The Court held that it has to be to the extent finance permits. No country has unlimited resources to spend on any of its projects.

In Confederation of Ex-servicemen Association v. Union of India [liv] , the right to get free and timely legal aid or facilities was not held as a fundamental right of ex-servicemen. Therefore, a policy decision in formulating a contributory scheme for ex-servicemen and asking them to pay a one-time contribution does not violate Art. 21, nor is it inconsistent with Part IV of the Constitution.

No Right to Die

While Article 21 confers on a person the right to live a dignified life, does it also confers a right to a person to end their life? If so, then what is the fate of Section 309 Indian Penal Code (1860), which punishes a person convicted of attempting to commit suicide? There has been a difference of opinion on the justification of this provision to continue on the statute book.

This question came for consideration for the first time before the High Court of Bombay in State of Maharashtra v. Maruti Sripati Dubal. In this case, the Bombay High Court held that the right to life guaranteed under Article 21 includes the right to die. The Hon’ble High Court struck down Section 309 of the IPC that provides punishment for an attempt to commit suicide on a person as unconstitutional.

In P. Rathinam v. Union of India [lv] , a two-judge Division Bench of the Supreme Court took cognisance of the relationship/contradiction between Section 309 IPC and Article 21. The Court supported the decision of the High Court of Bombay in Maruti Sripati Dubal’s Case held that the right to life embodies in Article 21 also embodied in it a right not to live a forced life, to his detriment, disadvantage or disliking.

The Court argued that the word life in Article 21 means the right to live with human dignity, and the same does not merely connote continued drudgery. Thus the Court concluded that the right to live of which Article 21 speaks could bring in the right not to live a forced life. The Court further emphasised that an ‘attempt to commit suicide is, in reality, a cry for held and not for punishment’.

The Rathinam ruling came to be reviewed by a full bench of the Court in Gian Kaur v. State of Punjab [lvi] . The question before the Court was: if the principal offence of attempting to commit suicide is void as unconstitutional vis-à-vis Article 21, then how abetment can thereof be punishable under Section 306 IPC?

It was argued that ‘the right to die’ had been included in Article 21 (Rathinam ruling) and Sec. 309 declared unconstitutional. Thus, any person abetting the commission of suicide by another is merely assisting in enforcing his fundamental Right under Article 21.

The Court overruled the decision of the Division Bench in the above-stated case and has put an end to the controversy and ruled that Art.21 is a provision guaranteeing the protection of life and personal liberty and by no stretch of imagination can extinction of life’ be read to be included in the protection of life. The Court observed further:

“……’Right to life’ is a natural right embodied in Article 21 but suicide is an unnatural termination or extinction of life and, therefore, incompatible and inconsistent with the concept of right to life”

However, in this regard, in 2020, the Supreme Court had sought a response from the central government. The Court had asked the center to explain its stance on the conflict between Section 309 and the Mental Healthcare Act, promulgated in 2017 (MHCA). As opposed to Section 309, which criminalises attempts to suicide, the MHCA proscribes prosecution of the person attempting it. Given that the Section is colonial legislation, many have vocalised to do away with the same altogether. Additionally, in 2018, in a 134-page-long judgment, Justice DY Chandrachud said it was ‘inhuman’ to punish someone who was already distressed .

Euthanasia and Right to Life

Euthanasia is the termination of the life of a person who is terminally ill or in a permanent vegetative state. In Gian Kaur v. State of Punjab [lvii] , the Supreme Court has distinguished between Euthanasia and an attempt to commit suicide.

The Court held that death due to termination of natural life is certain and imminent, and the process of natural death has commenced. Therefore, these are not cases of extinguishing life but only of accelerating the conclusion of the process of natural death that has already started.

The Court further held that this might fall within the ambit of the right to live with human dignity up to the end of natural life. This may include the right of a dying man to also die with dignity when his life is ebbing out. However, this cannot be equated with the right to die an unnatural death curtailing the natural span of life.

Sentence of Death –Rarest of Rare Cases

The law commission of India has dealt with the issue of abolition or retention of capital punishment, collecting as much available material as possible and assessing the views expressed by western scholars. The commission recommended the retention of capital punishment in the present state of the country.

The commission held recognised the on-ground conditions of India. By that, it meant the difference in the social upbringing, morality and education, its diversity and population. Given all these factors, India could not risk the experiment of the abolition of capital punishment.

In Jagmohan v. State of U P [lviii] , the Supreme Court had held that the death penalty was not violative of Articles 14, 19 and 21. It was said that the judge was to make the choice between the death penalty and imprisonment for life based on circumstances, facts, and nature of crime brought on record during trial. Therefore, the choice of awarding death sentence was done in accordance with the procedure established by law as required under article 21

But, in Rajindera Parsad v. State of U.P. [lix] , Krishna Iyer J., speaking for the majority, held that capital punishment would not be justified unless it was shown that the criminal was dangerous to society. The learned judge plead for the abolition of the death penalty and said that it should be retained only for ‘white collar crimes’

However, in Bachan Singh v. State of Punjab [lx] , the leading case of on the question, a constitution bench of the Supreme Court explained that article 21 recognised the right of the state to deprive a person of his life in accordance with just, fair and reasonable procedure established by valid law. It was further held that the death penalty for the offence of murder awarded under section 302 of IPC did not violate the basic feature of the Constitution.

Right to get Pollution Free Water and Air

In Subhas Kumar v. State of Bihar [lxi] , it has held that a Public Interest Litigation is maintainable for ensuring enjoyment of pollution-free water and air which is included in ‘right to live’ under Art.21 of the Constitution. The Court observed:

“Right to live is a fundamental right under Art 21 of the Constitution and it includes the right of enjoyment of pollution free water and air for full enjoyment of life. If anything endangers or impairs that quality of life in derogation of laws, a citizen has right to have recourse to Art.32 of the Constitution for removing the pollution of water or air which may be detrimental to the quality of life.”

Right to Clean Environment

The “Right to Life” under Article 21 means a life of dignity to live in a proper environment free from the dangers of diseases and infection. Maintenance of health, preservation of the sanitation and environment have been held to fall within the purview of Article 21 as it adversely affects the life of the citizens and it amounts to slow poisoning and reducing the life of the citizens because of the hazards created if not checked.

The following are some of the well-known cases on the environment under Article 21:

In M.C. Mehta v. Union of India (1988) [lxii] , the Supreme Court ordered the closure of tanneries polluting the water.

In M.C. Mehta v. Union of India (1997) [lxiii] , the Supreme Court issued several guidelines and directions for the protection of the Taj Mahal, an ancient monument, from environmental degradation.

In Vellore Citizens Welfare Forum v. Union of India [lxiv] , the Court took cognisance of the environmental problems being caused by tanneries that were polluting the water resources, rivers, canals, underground water, and agricultural land. As a result, the Court issued several directions to deal with the problem.

In Milk Men Colony Vikas Samiti v. State Of Rajasthan [lxv] , the Supreme Court held that the “right to life” means clean surroundings, which leads to a healthy body and mind. It includes the right to freedom from stray cattle and animals in urban areas.

In M.C. Mehta v. Union of India (2006) [lxvi] , the Court held that the blatant and large-scale misuse of residential premises for commercial use in Delhi violated the right to a salubrious sand decent environment. Taking note of the problem, the Court issued directives to the government on the same.

In Murli S. Deora v. Union of India [lxvii] , the persons not indulging in smoking cannot be compelled to or subjected to passive smoking on account of the act of sTherefore, rights. Right to Life under Article 21 is affected as a non-smoker may become a victim of someone smoking in a public place.

Right Against Noise Pollution

In Re: Noise Pollution [lxviii] , the case was regarding noise pollution caused by obnoxious noise levels due to the bursting of crackers during Diwali. The Apex Court suggested to desist from bursting and making use of such noise-making crackers and observed that:

“Article 21 of the Constitution guarantees the life and personal liberty to all persons. It guarantees the right of persons to life with human dignity. Therein are included, all the aspects of life which go to make a person’s life meaningful, complete and worth living. The human life has its charm and there is no reason why life should not be enjoyed along with all permissible pleasures. Anyone who wishes to live in peace, comfort, and quiet within his house has a right to prevent the noise as pollutant reaching him.”

Continued…

“No one can claim a right to create noise even in his own premises that would travel beyond his precincts and cause the nuisance to neighbors or others. Any noise, which has the effect of materially interfering with the ordinary comforts of life judged by the standard of a reasonable man, is nuisance…. While one has a right to speech, others have a right to listen or decline to listen. Nobody can be compelled to listen and nobody can claim that he has a right to make his voice trespass into the ears or mind of others. Nobody can indulge in aural aggression. If anyone increases his volume of speech and that too with the assistance of artificial devices so as to compulsorily expose unwilling persons to hear a noise raised to unpleasant or obnoxious levels then the person speaking is violating the right of others to a peaceful, comfortable and pollution-free life guaranteed by Article 21. Article 19(1)(a) cannot be pressed into service for defeating the fundamental right guaranteed by Article 21 [lxix] “.

Right to Know

Holding that the right to life has reached new dimensions and urgency the Supreme Court in RP Ltd. v. Proprietors Indian Express Newspapers, Bombay Pvt. Ltd., observed that if democracy had to function effectively, people must have the right to know and to obtain the conduct of affairs of the state.

In Essar Oil Ltd. v. Halar Utkarsh Samiti, the Supreme Court said that there was a strong link between Art.21 and the right to know, particularly where secret government decisions may affect health, life, and livelihood.

Reiterating the above observations made in the instant case, the Apex Court in Reliance Petrochemicals Ltd. v. Proprietors of Indian Express Newspapers, ruled that the citizens who had been made responsible for protecting the environment had a right to know the government proposal.

Read more about right to know here .

Personal Liberty

The liberty of the person is one of the oldest concepts to be protected by national courts. As long as 1215, the English Magna Carta provided that,

No freeman shall be taken or imprisoned… but… by the law of the land.

The smallest Article of eighteen words has the greatest significance for those who cherish the ideals of liberty. What can be more important than liberty? In India, the concept of ‘liberty’ has received a far more expansive interpretation. The Supreme Court of India has rejected the view that liberty denotes merely freedom from bodily restraint, and has held that it encompasses those rights and privileges that have long been recognised as being essential to the orderly pursuit of happiness by free men.

The meaning of the term’ personal liberty’ was considered by the Supreme Court in Kharak Singh’s case, which arose out of the challenge to Constitutional validity of the U. P. Police Regulations that provided for surveillance by way of domiciliary visits secret picketing.

Oddly enough, both the majority and minority on the bench relied on the meaning given to the term ‘personal liberty’ by an American judgment (per Field, J.,) in Munn v Illinois , which held the term ‘life’ meant something more than mere animal existence. The prohibition against its deprivation extended to all those limits and faculties by which life was enjoyed.

This provision equally prohibited the mutilation of the body or the amputation of an arm or leg or the putting of an eye or the destruction of any other organ of the body through which the soul communicated with the outer world. The majority held that the U. P. Police Regulations authorising domiciliary visits [at night by police officers as a form of surveillance, constituted a deprivation of liberty and thus] unconstitutional.

The Court observed that the right to personal liberty in the Indian Constitution is the right of an individual to be free from restrictions or encroachments on his person, whether they are directly imposed or indirectly brought about by calculated measures.

The Supreme Court has held that even lawful imprisonment does not spell farewell to all fundamental rights. A prisoner retains all the rights enjoyed by a free citizen except only those ‘necessarily’ lost as an incident of imprisonment

Right to Privacy and Article 21

Although not explicitly mentioned in the Constitution, the right to privacy was considered a ‘penumbral right’ under the Constitution, i.e. a right declared by the Supreme Court as integral to the fundamental right to life and liberty. After the KS Puttuswamy judgment, the right to privacy has been read and understood by the Court in various landmark judgments.

The Supreme Court has culled the right to privacy from Article 21 and other provisions of the Constitution, read with the Directive Principles of State Policy.

Although no single statute confers a crosscutting ‘horizontal’ right to privacy, various statutes had provisions that either implicitly or explicitly preserved this right . [lxx]

For the first time in Kharak Singh v. State of UP , [lxxi] the Court questioned whether the right to privacy could be implied from the existing fundamental rights such as Art. 19(1)(d), 19(1)(e) and 21, came before the Court. “Surveillance” under Chapter XX of the UP Police Regulations constituted an infringement of any of the fundamental rights guaranteed by Part III of the Constitution. Regulation 236(b), which permitted surveillance by “domiciliary visits at night”, was held to violate Article 21. A seven-judge bench held that:

“the meanings of the expressions “life” and “personal liberty” in Article 21 were considered by this Court in Kharak Singh’s case. Although the majority found that the Constitution contained no explicit guarantee of a “right to privacy”, it read the right to personal liberty expansively to include a right to dignity. It held that “an unauthorised intrusion into a person’s home and the disturbance caused to him thereby, is as it were the violation of a common law right of a man -an ultimate essential of ordered liberty, if not of the very concept of civilisation”

In a minority judgment, in this case, Justice Subba Rao held that:

“the right to personal liberty takes in not only a right to be free from restrictions placed on his movements but also free from encroachments on his private life. It is true our Constitution does not expressly declare a right to privacy as a fundamental right but the said right is an essential ingredient of personal liberty. Every democratic country sanctifies domestic life; it is expected to give him rest, physical happiness, peace of mind and security. In the last resort, a person’s house, where he lives with his family, is his ‘castle’; it is his rampart against encroachment on his personal liberty”.

This case, especially Justice Subba Rao’s observations, paved the way for later elaborations on the right to privacy using Article 21.

In Govind v. State of Madhya Pradesh [lxxii] , The Supreme Court took a more elaborate appraisal of the right to privacy. In this case, the Court was evaluating the constitutional validity of Regulations 855 and 856 of the Madhya Pradesh Police Regulations, which provided for police surveillance of habitual offenders including domiciliary visits and picketing of the suspects. The Supreme Court desisted from striking down these invasive provisions holding that:

“It cannot be said that surveillance by domiciliary visit would always be an unreasonable restriction upon the right of privacy. It is only persons who are suspected to be habitual criminals and those who are determined to lead a criminal life that is subjected to surveillance.”

The Court accepted a limited fundamental right to privacy as an emanation from Arts.19(a), (d) and 21. Mathew J. observed in the instant case,

“The Right to privacy will, therefore, necessarily, have to go through a process of case by case development. Hence, assuming that the right to personal liberty. the right to move freely throughout India and the freedom of speech create an independent fundamental right of privacy as an emanation from them that one can characterise as a fundamental right, we do not think that the right is absolute….. …… Assuming that the fundamental rights explicitly guaranteed to a citizen have penumbral zones and that the right to privacy is itself a fundamental right that fundamental right must be subject to restrictions on the basis of compelling public interest.”

Scope and Content of Right to Privacy Pre-Puttaswamy Judgment

Read more about the right to privacy as part of Academike’s Constitutional Rights Series here

Tapping of Telephone

Emanating from the right to privacy is the question of tapping of the telephone.

In RM Malkani v. State of Maharashtra, the Supreme Court held that Courts would protect the telephonic conversation of an innocent citizen against wrongful or high handed’ interference by tapping the conversation. However, the protection is not for the guilty citizen against the efforts of the police to vindicate the law and prevent corruption of public servants.

Telephone tapping is permissible in India under Section 5(2) of the Telegraph Act, 1885 . The Section lays down the circumstances and grounds when an order for tapping a telephone may be passed, but no procedure for making the order is laid down therein.

The Supreme Court in PUCL v. Union of India held that in the absence of just and fair procedure for regulating the exercise of power under Section 5(2) of the Act, it is not possible to safeguard the fundamental rights of citizens under Section 19 and 21. Accordingly, the Court issued procedural safeguards to be observed before restoring to telephone tapping under Section 5(2) of the Act.

The Court further ruled:

“right to privacy is a part of the right to ‘life’ and ‘personal liberty’ enshrined under Article 21 of the Constitution. Once the facts in a given case constitute a right to privacy, Article 21 is attracted. The said right cannot be curtailed “except according to procedure established by law”. The Court has further ruled that Telephone conversation is an important facet of a man’s private life. Right to privacy would certainly include telephone conversation in the privacy of one’s home or office. Telephone tapping would, thus, infract Article 21 of the Constitution of India unless it is permitted under the procedure established by law. The procedure has to be just, fair and reasonable.”

Disclosure of Dreadful Diseases

In Mr X v. Hospital Z [lxxv] , the question before the Supreme Court was whether the disclosure by the doctor that his patient, who was to get married had tested HIV positive, would be violative of the patient’s right to privacy.

The Supreme Court ruled that the right to privacy was not absolute and might be lawfully restricted for the prevention of crime, disorder or protection of health or morals or protection of rights and freedom of others.

The Court explained that the right to life of a lady with whom the patient was to marry would positively include the right to be told that a person with whom she was proposed to be married was the victim of a deadly disease, which was sexually communicable.

Since the right to life included the right to a healthy life to enjoy all the facilities of the human body in prime condition, it was held that the doctors had not violated the right to privacy.

Right to Privacy and Subjecting a Person to Medical Tests

It is well settled that the right to privacy is not treated as absolute and is subject to such action as may be lawfully taken to prevent crimes or disorder or protect health or morals or protection of rights and freedom of others. If there is a conflict between the fundamental rights of two parties, which advances public morality would prevail.

In the case Sharda v. Dharmpal [lxxvi] , a three-judge bench ruled that a matrimonial court had the power to direct the parties in a divorce proceeding to undergo a medical examination. A direction issued for this could not be held to violate one’s right to privacy. The Court, however, said that there must be sufficient material for this.

Right to Privacy: Woman’s Right to Make Reproductive Choices

A woman’s right to make reproductive choices includes the woman’s right to refuse participation in the sexual activity or the insistence on using contraceptive methods such as undergoing sterilisation procedures. The woman’s entitlement to carry a pregnancy to its full term, to give birth subsequently raise children.

Right to Travel Abroad

In Satwant Singh Sawhney v. Assistant Passport Officer, New Delhi [lxxvii] , the Supreme Court has included the right to travel abroad contained in the expression “personal liberty” within the meaning of Article 21.

In Maneka Gandhi v. Union of India [lxxviii] , the validity of Sec. 10(3)(c) of the passport Act 1967, which empowered the government to impound the passport of a person, in the interest of the general public, was challenged before the seven-judge Bench of the Supreme Court.

It was contended that, right to travel abroad being a part of the right to “personal liberty” the impugned Section didn’t prescribe any procedure to deprive her of her liberty and hence it was violative of Art. 21.

The Court held that the procedure contemplated must stand the test of reasonableness in order to conform to Art.21 other fundamental rights. It was further held that the right to travel abroad falls under Art. 21, natural justice must be applied while exercising the power of impounding a passport under the Passport Act. Bhagwati, J., observed:

The principle of reasonableness, which legally as well as philosophically, is an essential element of equality or non-arbitrariness pervades Article 14 like a brooding omnipresence and that It must be “‘right and just and fair” and not arbitrary, fanciful or oppressive; otherwise, it would be no procedure at all and the requirement of Article 21 would not be satisfied.

Right against Illegal Detention

In Joginder Kumar v. State of Uttar Pradesh [lxxix] , the petitioner was detained by the police officers and his whereabouts were not told to his family members for a period of five days. Taking serious note of the police high headedness and illegal detention of a free citizen, the Supreme Court laid down the guidelines governing arrest of a person during the investigation:

An arrested person being held in custody is entitled if he so requests to have a friend, relative or other person told as far as is practicable that he has been arrested and where he is being detained.

The police officer shall inform the arrested person when he is brought to the police station of this right. An entry shall be required to be made in the diary as to who was informed of the arrest.

In the case of DK. Basu v. State of West Bengal [lxxx] , the Supreme Court laid down detailed guidelines to be followed by the central and state investigating agencies in all cases of arrest and detention. Furthermore, the Court ordered that the guidelines be followed till legal provisions are made on that behalf as preventive measures. It also held that any form of torture or cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment, whether it occurs during interrogation or otherwise, falls within the ambit of Article 21.

Article 21 and Prisoner’s Rights

The protection of Article 21 is available even to convicts in jail. The convicts are not deprived of all the fundamental rights they otherwise possess by mere reason of their conviction. Following the conviction of a convict is put into jail he may be deprived of fundamental freedoms like the right to move freely throughout the territory of India. But a convict is entitled to the precious right guaranteed under Article 21, and he shall not be deprived of his life and personal liberty except by a procedure established by law [lxxxi] .

In Maneka Gandhi v. Union of India , the Supreme Court gave a new dimension to Article 21. The Court has interpreted Article 21 to have the widest possible amplitude. On being convicted of a crime and deprived of their liberty following the procedure established by law. Article 21 has laid down a new constitutional and prison jurisprudence [lxxxii] .

The rights and protections recognised to be given in the topics to follow.

Right to Free Legal Aid & Right to Appeal

In M.H. Hoskot v. State of Maharashtra [lxxxiii] , while holding free legal aid as an integral part of fair procedure, the Court explained:

“the two important ingredients of the right of appeal are; firstly, service of a copy of a judgement to the prisoner in time to enable him to file an appeal and secondly, provision of free legal service to the prisoner who is indigent or otherwise disabled from securing legal assistance. This right to free legal aid is the duty of the government and is an implicit aspect of Article 21 in ensuring fairness and reasonableness; this cannot be termed as government charity.”

In other words, an accused person, where the charge is of an offence punishable with imprisonment, is entitled to be offered legal aid if he is too poor to afford counsel. In addition, counsel for the accused must be given sufficient time and facility for preparing his defence. Breach of these safeguards of a fair trial would invalidate the trial and conviction.

Right to Speedy Trial

In Hussainara Khatoon v. Home Secretary, State of Bihar [lxxxiv] , the Supreme Court observed that an alarming number of men, women and children were kept in prisons for years awaiting trial in courts of law.

The Court noted the situation and observed that it was carrying a shame on the judicial system that permitted incarceration of men and women for such long periods without trials.

The Court held that detention of undertrial prisoners in jail for a period more than what they would have been sentenced to if convicted was illegal. And the same violated Article 21. The Court ordered to release of undertrial prisoners who had been in jail for a longer period than the punishment meted out in case of conviction.

In A.R. Antulay v. R.S. Nayak [lxxxv] , a Constitution Bench of five judges of the Supreme Court dealt with the question and laid down specific guidelines for ensuring speedy trial of offences some of them have been listed below [lxxxvi] :

Fair, just and reasonable procedure implicit in Article 21 creates a right in the accused to be tried speedily.

Right to speedy trial flowing from Article 21 encompasses all the stages, namely the stage of investigation, inquiry, appeal, revision, and retrial.

The concerns underlying the right of the speedy trial from the point of view of the accused are:

The period of remand and pre-conviction detention should be as short as possible.

The worry, anxiety, expense and disturbance to his vocation and peace, resulting from an unduly prolonged investigation, inquiry or trial should be minimal; and

Undue delay may well result in impairment of the ability of the accused to defend him.

While determining whether the undue delay has occurred, one must regard all the attendant circumstances, including the nature of the offence, the number of accused and witnesses, and the Court’s workload concerned. Every delay does not necessarily prejudice the accused. An accuser’s plea of denial of the speedy trial cannot be defeated by saying that the accused did at no time demand a speedy trial

In the case of Anil Rai v. State of Bihar [lxxxvii] , the Supreme Court directed the Judges of the High Courts to give quick judgments, and in certain circumstances, the parties are to apply to the Chief Justice to move the case to another bench or to do the needful at his discretion.

Right to Fair Trial

The free and fair trial has been said to be the sine qua non of Article 21. The Supreme Court in Zahira Habibullah Sheikh v. State of Gujarat [lxxxviii] said that the right to free and fair trial to the accused and the victims, their family members, and relatives and society at large.

Right to Bail

The Supreme Court has diagnosed the root cause for long pre-trial incarceration to bathe present-day unsatisfactory and irrational rules for bail, which insists merely on financial security from the accused and their sureties. Many of the undertrials being poor and indigent are unable to provide any financial security. Consequently, they have to languish in prisons awaiting their trials.

But incarceration of persons charged with non-bailable offences during the pendency of trial cannot be questioned as violative of Article 21 since the same is authorised by law. In Babu Singh v. State of Uttar Pradesh [lxxxix] , the Court held that the right to bail was included in the personal liberty under Article 21. Its refusal would be the deprivation of that liberty, which could be authorised in accordance with the procedure established by law.

Anticipatory bail is a statutory right, and it does not arise out of Article 21. Therefore, anticipatory bail cannot be granted as a matter of right as it cannot be granted as a matter of right as it cannot be considered as an essential ingredient of Article 21.

Right Against Handcuffing

Handcuffing has been considered prima facie inhuman and therefore unreasonable, over-harsh and at first flush, arbitrary. It has been held to be unwarranted and violative of Article 21.

In Prem Shankar v. Delhi Administration [xc] , the Supreme Court struck down the Rules that provided that every undertrial accused of a non-bailable offence punishable with more than three years prison term would be routinely handcuffed. Instead, the Court ruled that handcuffing should be resorted to only when there was “clear and present danger of escape” of the accused under -trial, breaking out of police control.

Right Against Solitary Confinement

It has been held that a convict is not wholly denuded of his fundamental rights, and his conviction does not reduce him into a non – person whose rights are subjected to the whims of the prison administration. Therefore, the imposition of any major punishment within the prison system is conditional upon the observance of procedural safeguard.

In Sunil Batra v. Delhi Administration [xci] , the petitioner was sentenced to death by the Delhi session court and his appeal against the decision was pending before the high Court. He was detained in Tihar Jail during the pendency of the appeal. He complained that since the date of conviction by the session court, he was kept in solitary confinement.

It was contended that Section 30 of the Prisoners Act does not authorise jail authorities to send him to solitary confinement, which by itself was a substantive punishment under Sections 73 and 74 of the Indian Penal Code, 1860 and could be imposed by a court of law. Therefore, it could not be left to the whim and caprice of the prison authorities. The Supreme Court accepted the petitioner’s argument and held that the imposition of solitary confinement on the petitioner was violative of Article 21.

Right Against Custodial Violence

The incidents of brutal police behaviour towards persons detained on suspicion of having committed crimes are routine. There has been a lot of public outcry from time to time against custodial deaths.

The Supreme Court has taken a very positive stand against the atrocities, intimidation, harassment and use of third-degree methods to extort confessions. The Court has classified these as being against human dignity. The rights under Article 21 secure life with human dignity and the same are available against torture.

Death by hanging is Not Violative of Article 21

In Deena v. Union of India [xcii] , the constitutional validity of the death sentence by hanging was challenged as being “barbarous, inhuman, and degrading” and therefore violative of Article 21.

The Court, in this case, referred to the Report of the UK Royal Commission, 1949, the opinion of the Director-General of Health Services of India, the 35 th Report of the Law Commission and the opinion of the Prison Advisers and Forensic Medicine Experts. Finally, it held that death by hanging was the best and least painful method of carrying out the death penalty. Thus, not violative of Article 21.

Right against Public Hanging

The Rajasthan High Court, by an order, directed the execution of the death sentence of an accused by hanging at the Stadium Ground of Jaipur. It was also directed that the execution should be done after giving widespread publicity through the media.

On receipt of the above order, the Supreme Court in Attorney General of India v. Lachma Devi [xciii] held that the direction for the execution of the death sentence was unconstitutional and violative of Article 21.

It was further made clear that death by public hanging would be a barbaric practice. Although the crime for which the accused has been found guilty was barbaric, it would be a shame on the civilised society to reciprocate the same. The Court said,

“a barbaric crime should not have to be visited with a barbaric penalty.”

Right Against Delayed Execution

In T.V. Vatheeswaram v. State of Tamil Nadu [xcv] , the Supreme Court held that the delay in execution of a death sentence exceeding 2 years would be sufficient ground to invoke protection under Article 21 and the death sentence be commuted to life imprisonment. The cause of the delay is immaterial. The accused himself may be the cause of the delay.

In Sher Singh v. State of Punjab [xcvi] , the Supreme Court said that prolonged wait for the execution of a death sentence is an unjust, unfair and unreasonable procedure, and the only way to undo that is through Article 21.

But the Court held that this could not be taken as the rule of law and applied to each case, and each case should be decided upon its own facts.

Procedure Established by Law and Article 21

The expression ‘procedure established by law’ has been the subject of interpretation in a catena of cases. A survey of these cases reveals that courts in judicial interpretation have enlarged the scope of the expression.

The Supreme Court took the view that ‘procedure established by law’ in Article 21 means procedure prescribed by law as enacted by the state and rejected to equate it with the American ‘due process of law’.

But, in Maneka Gandhi v Union of India, the Supreme Court observed that the procedure prescribed by law for depriving a person of his life and personal liberty must be ‘right, just and fair’ and not ‘arbitrary, fanciful and oppressive’.

It also held that otherwise, it would be no procedure, and the requirement of Article 21 would not be satisfied. Thus, the ‘procedure established by law’ has acquired the same significance in India as the ‘due process of law’ clause in America.

Justice V. R. Krishna Iyer, speaking in Sunil Batra v Delhi Administration said:

“(though) our Constitution has no due process clause (but after Maneka Gandhi’s case) the consequence is the same, and as much as such Article 21 may be treated as counterpart of the due process clause in American Constitution.”

In December 1985, the Rajasthan High Court sentenced a man, Jagdish Kumar, and a woman, Lichma Devi, to death for killing two young women by setting them on fire. In an unprecedented move, the Court ordered both prisoners to be publicly executed.

In response to a review petition by the Attorney General against this judgment, the Supreme Court in December 1985 stayed the public hangings, observing that ‘a barbaric crime does not have to be met with a barbaric penalty’.

Furthermore, the Court observed that the execution of a death sentence by public hanging violates Article 21, which mandates the observance of a just, fair and reasonable procedure.

Thus, an order passed by the High Court of Rajasthan for public hanging was set aside by the Supreme Court on the ground, among other things, that it was violative of Article 21. Again, in Sher Singh v State of Punjab , the Supreme Court held that unjustifiable delay in execution of death sentence violates Article 21.

The Supreme Court has taken the view that this Article read is concerned with the fullest development of an individual, ensuring his dignity through the rule of law. Therefore, every procedure must seem to be ‘reasonable, fair and just’.

The right to life and personal liberty has been interpreted widely to include the right to livelihood, health, education, environment and all those matters that contributed to life with dignity.

The test of procedural fairness has been deemed to be proportional to protecting such rights. Thus, where workers have been deemed to have the right to public employment and the right to livelihood, a hire-fire clause in favour of the state is not reasonable, fair and just, even though the state cannot affirmatively provide a livelihood for all.

Under this doctrine, the Court will examine whether the procedure itself is reasonable, fair and just. And whether it has been operated in a fair, just and reasonable manner.

This has meant, for example, the right to a speedy trial and legal aid is part of any reasonable, fair and just procedure. The process clause is comprehensive and applicable in all areas of State action covering civil, criminal and administrative action.

In one of the landmark decisions in the case of Murli S. Deora v. Union of India , the Supreme Court of India observed that the fundamental right guaranteed under Article 21 of the Constitution of India provides that none shall be deprived of his life without due process of law.

The Court observed that smoking in public places is an indirect deprivation of life of non-smokers without any process of law. Considering the adverse effect of smoking on smokers and passive smokers, the Supreme Court directed the prohibition of smoking in public places.

It issued directions to the Union of India, State Governments and the Union Territories to take adequate steps to ensure the prohibition of smoking in public places such as auditoriums, hospital buildings, health institutions etc.

In this manner, the Supreme Court gave a liberal interpretation to Article 21 of the Constitution and expanded its horizon to include the rights of non-smokers.

Further, when there is an inordinate delay in the investigation – it affects the right of the accused, as he is kept in tenterhooks and suspense about the outcome of the case. If the investigating authority pursues the investigation as per the provisions of the Code, there can be no cause of action.

But, if the case is kept alive without any progress in any investigation, then the provisions of Article 21 are attracted. The right is against actual proceedings in Court and against police investigation.

The Supreme Court has widened the scope of ‘procedure established by law’ and held that merely a procedure had been established by law, a person cannot be deprived of his life and liberty unless the procedure is just, fair and reasonable.

Hence, it is well established that to deprive a person of his life and personal liberty must be done under a ‘procedure, established by law’. Such an exception must be made in a just, fair and reasonable manner and must not be arbitrary, fanciful or oppressive. Therefore, for the procedure to be valid, it must comply with the principles of natural justice.

Article 21 and The Emergency

In ADM Jabalpur v. S. Shukla [xcviii] , popularly known as the habeas corpus case, the Supreme Court held that Article 21 was the sole repository of the right to life and personal liberty.

Therefore, if the presidential order suspended the right to move any court to enforce that right under Article 359, the detune would have no locus standi to a writ petition for challenging the legality of his detention.

Hence, such a wide connotation of Article 359 denied the cherished right to personal liberty guaranteed to the citizens. Experience established that during the emergence of 1975, the people’s fundamental freedom had lost all meaning.

So that it must not occur again, the constitution act, 1978, amended article 359 to the effect that during the operation of the proclamation of emergency, the remedy for the enforcement of the fundamental right guaranteed by article 21 would not be suspended under a presidential order.

Given the 44 th amendment, 1978, the observations in the above-cited judgments are left merely of academic importance.

India, legal Service. Article 21 of the Constitution of India – the Expanding Horizons , www.legalserviceindia.com/articles/art222.htm.

“Article 21 of the Constitution of India.” Scribd , Scribd, www.scribd.com/doc/52481658/Article-21-of-the-Constitution-of-India.

Math, Suresh Bada. “10. Rights of Prisoners.” Nimhans.kar.nic.in , www.academia.edu/1192854/10._RIGHTS_OF_PRISONERS.

“SC Agrees to Examine Right to Shelter for PAVEMENT DWELLERS-INDIA News , Firstpost.” Firstpost , Sept. 2013, www.firstpost.com/india/sc-agrees-to-examine-right-to-shelter-for-pavement-dwellers-1108073.html.

admin on August 31, 2016 4:32 PM, et al. Human Rights and Jurisprudence: Right to Life / Livelihood Archives , www.hurights.or.jp/english/human_rights_and_jurisprudence/right-to-lifelivelihood/.

“Article 21 of the Constitution of India – DISCUSSED!” Your Article Library , 24 Feb. 2014, www.yourarticlelibrary.com/constitution/article-21-of-the-constitution-of-india-discussed/5497/.

“Honour Killing.” LAW REPORTS INDIA , 29 Apr. 2011, lawreports.wordpress.com/category/honour-killing/.

Grewal, Puneet Kaur. “Honour Killings and Law in India.” IOSR Journal of Humanities and Social Science , vol. 5, no. 6, 2012, pp. 28–31., doi:10.9790/0837-0562831.

Annavarapu, Sneha. “Honor Killings, Human Rights and Indian Law.” Economic and Political Weekly , www.academia.edu/5386926/Honor_Killings_Human_Rights_and_Indian_Law.

Nandimath, Omprakash V. “Consent and Medical Treatment: The Legal Paradigm in India.” Indian Journal of Urology : IJU : Journal of the Urological Society of India , Medknow Publications, July 2009, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2779959/.

http://www.hrln.org/hrln/peoples-health-rights/pils-a-cases/1484-sc-reaffirms-workers-right-to-health-and-medical-care.html

Cases as appearing in the Article:

[i] AIR 1963 SC 1295

[ii] AIR 1978 SC 1675

[iii] 1978 AIR 597, 1978 SCR (2) 621

[iv] 1981 AIR 746, 1981 SCR (2) 516

[v] 1984 AIR 802, 1984 SCR (2) 67