Effects of Economic Globalization

Globalization has led to increases in standards of living around the world, but not all of its effects are positive for everyone.

Social Studies, Economics, World History

Bangladesh Garment Workers

The garment industry in Bangladesh makes clothes that are then shipped out across the world. It employs as many as four million people, but the average worker earns less in a month than a U.S. worker earns in a day.

Photograph by Mushfiqul Alam

Put simply, globalization is the connection of different parts of the world. In economics, globalization can be defined as the process in which businesses, organizations, and countries begin operating on an international scale. Globalization is most often used in an economic context, but it also affects and is affected by politics and culture. In general, globalization has been shown to increase the standard of living in developing countries, but some analysts warn that globalization can have a negative effect on local or emerging economies and individual workers. A Historical View Globalization is not new. Since the start of civilization, people have traded goods with their neighbors. As cultures advanced, they were able to travel farther afield to trade their own goods for desirable products found elsewhere. The Silk Road, an ancient network of trade routes used between Europe, North Africa, East Africa, Central Asia, South Asia, and the Far East, is an example of early globalization. For more than 1,500 years, Europeans traded glass and manufactured goods for Chinese silk and spices, contributing to a global economy in which both Europe and Asia became accustomed to goods from far away. Following the European exploration of the New World, globalization occurred on a grand scale; the widespread transfer of plants, animals, foods, cultures, and ideas became known as the Columbian Exchange. The Triangular Trade network in which ships carried manufactured goods from Europe to Africa, enslaved Africans to the Americas, and raw materials back to Europe is another example of globalization. The resulting spread of slavery demonstrates that globalization can hurt people just as easily as it can connect people. The rate of globalization has increased in recent years, a result of rapid advancements in communication and transportation. Advances in communication enable businesses to identify opportunities for investment. At the same time, innovations in information technology enable immediate communication and the rapid transfer of financial assets across national borders. Improved fiscal policies within countries and international trade agreements between them also facilitate globalization. Political and economic stability facilitate globalization as well. The relative instability of many African nations is cited by experts as one of the reasons why Africa has not benefited from globalization as much as countries in Asia and Latin America. Benefits of Globalization Globalization provides businesses with a competitive advantage by allowing them to source raw materials where they are inexpensive. Globalization also gives organizations the opportunity to take advantage of lower labor costs in developing countries, while leveraging the technical expertise and experience of more developed economies. With globalization, different parts of a product may be made in different regions of the world. Globalization has long been used by the automotive industry , for instance, where different parts of a car may be manufactured in different countries. Businesses in several different countries may be involved in producing even seemingly simple products such as cotton T-shirts. Globalization affects services, too. Many businesses located in the United States have outsourced their call centers or information technology services to companies in India. As part of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), U.S. automobile companies relocated their operations to Mexico, where labor costs are lower. The result is more jobs in countries where jobs are needed, which can have a positive effect on the national economy and result in a higher standard of living. China is a prime example of a country that has benefited immensely from globalization. Another example is Vietnam, where globalization has contributed to an increase in the prices for rice, lifting many poor rice farmers out of poverty. As the standard of living increased, more children of poor families left work and attended school. Consumers benefit also. In general, globalization decreases the cost of manufacturing . This means that companies can offer goods at a lower price to consumers. The average cost of goods is a key aspect that contributes to increases in the standard of living. Consumers also have access to a wider variety of goods. In some cases, this may contribute to improved health by enabling a more varied and healthier diet; in others, it is blamed for increases in unhealthy food consumption and diabetes. Downsides Not everything about globalization is beneficial. Any change has winners and losers, and the people living in communities that had been dependent on jobs outsourced elsewhere often suffer. Effectively, this means that workers in the developed world must compete with lower-cost markets for jobs; unions and workers may be unable to defend against the threat of corporations that offer the alternative between lower pay or losing jobs to a supplier in a less expensive labor market. The situation is more complex in the developing world, where economies are undergoing rapid change. Indeed, the working conditions of people at some points in the supply chain are deplorable. The garment industry in Bangladesh, for instance, employs an estimated four million people, but the average worker earns less in a month than a U.S. worker earns in a day. In 2013, a textile factory building collapsed, killing more than 1,100 workers. Critics also suggest that employment opportunities for children in poor countries may increase negative impacts of child labor and lure children of poor families away from school. In general, critics blame the pressures of globalization for encouraging an environment that exploits workers in countries that do not offer sufficient protections. Studies also suggest that globalization may contribute to income disparity and inequality between the more educated and less educated members of a society. This means that unskilled workers may be affected by declining wages, which are under constant pressure from globalization. Into the Future Regardless of the downsides, globalization is here to stay. The result is a smaller, more connected world. Socially, globalization has facilitated the exchange of ideas and cultures, contributing to a world view in which people are more open and tolerant of one another.

Articles & Profiles

Media credits.

The audio, illustrations, photos, and videos are credited beneath the media asset, except for promotional images, which generally link to another page that contains the media credit. The Rights Holder for media is the person or group credited.

Production Managers

Program specialists, last updated.

February 20, 2024

User Permissions

For information on user permissions, please read our Terms of Service. If you have questions about how to cite anything on our website in your project or classroom presentation, please contact your teacher. They will best know the preferred format. When you reach out to them, you will need the page title, URL, and the date you accessed the resource.

If a media asset is downloadable, a download button appears in the corner of the media viewer. If no button appears, you cannot download or save the media.

Text on this page is printable and can be used according to our Terms of Service .

Interactives

Any interactives on this page can only be played while you are visiting our website. You cannot download interactives.

Related Resources

How Globalization Forces Affect Quality of Life Essay

Globalization can be described as how nations from different parts of the world are becoming more interconnected. Essentially, it also captures in its scope the economic and social changes that have come about as a result. It may be pictured as the threads of an immense spider web formed over millennia, with the number and reach of these threads increasing over time. Therefore, the interconnection has been influenced by forces like advanced technology, transportation, global finance, and the media; through globalization, the economy of states has been boosted, and new hostile cultures have also been formed.

For example, globalization can boost the economy and raise living standards while posing risks to the economy’s health and the welfare of workers. Gathering support from speeches and films of world-renowned figures that address the effects of globalization on our daily life. Globalization has helped emerging, and industrialized nations’ economies expand by creating a market for products and services (Bailey, 2015). The Gross Domestic Product, commonly known as GDP and typically expressed as a percentage, is the most common way to quantify economic growth. Macron, in his speech, talks of equalitative efforts from states and civil societies to help enhance globalization. He talks of building a France recognized by all and one capable of standing behind those forgotten by globalization (BQ Prime, 2018). By aiding and abetting emerging nations by providing loans to strengthen their economies, globalization has encouraged peace among nations.

Instead, the interaction of many groups in our culture has impacted the formation of new cultural practices that are hostile to specific communities. On the other side, given that most of our jobs have been replaced by robots, the media has impacted the third generation, rendering them indolent. Other issues, such as escalating violence, moral decay, and a lack of employment due to population growth, have a negative impact on people’s lives. The increase in commercial fraud brought on by globalization has impacted the world market. Warren Buffet talks about trade wars and how they have affected the global marketing system (Fox Business, 2018). He speaks of how producers do not want the trade wars to be passed to customers since it will be a great crisis. Essentially, it is also noted that human beings have the right to life, to vote, and anything that pertains to them and is legal, as portrayed by the constitution (Frank, 2001).

The US government’s dissatisfaction with the results of globalization is shown in the current implementation of and hikes in tariff levels on specific groups of imports. The US government implemented nationalist and protectionist policies to compel the relocation of industrial jobs, particularly labor-intensive jobs, to the US. Immigration has increased in this region purposefully to market products and improve the state’s economy (Kamarck et al., 2022). According to the research, the labor stagnation between and within nations has caused globalization-related dislocations in several developed economies. Artificial immigration barriers between countries impede the movement of workers, and labor market rigidities and the lack of perfect substitutes within nations hindering the movement of labor from lagging to flourishing economic sectors, resulting in significant income disparities (PRB, 2010).

In conclusion, it is evident that globalization is an aspect that is helpful in today’s world. However, the interaction can be a problem whenever wars are present. Forces, including cutting-edge technology, transportation, global finance, and the media, have impacted interconnection. Generally, it ultimately affects communities and societies negatively and positively. Essentially, no nation can thrive in solitude; instead, allowing all production factors to circulate without limits would enable all individuals of the advantages of globalization to be realized.

Bailey, R. (2015). Globalization is good for you! Reason. Web.

BQ prime. (2018). Emmanuel Macron At WEF 2018: Globalization A Major Crisis [Video]. YouTube. Web.

Fox Business. (2018). Warren Buffett: We do not want trade wars [Video]. YouTube. Web.

Frank, T. M. (2001). Are Human Rights Universal? Center for Learning Innovation – Bellevue University.

Kamarck, E., Hudak, J., & Stenglein, C. (2017). Immigration by the numbers . Brookings. Web.

Population Bulletin Update: Immigration in America 2010 . PRB. Web.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2024, January 25). How Globalization Forces Affect Quality of Life. https://ivypanda.com/essays/how-globalization-forces-affect-quality-of-life/

"How Globalization Forces Affect Quality of Life." IvyPanda , 25 Jan. 2024, ivypanda.com/essays/how-globalization-forces-affect-quality-of-life/.

IvyPanda . (2024) 'How Globalization Forces Affect Quality of Life'. 25 January.

IvyPanda . 2024. "How Globalization Forces Affect Quality of Life." January 25, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/how-globalization-forces-affect-quality-of-life/.

1. IvyPanda . "How Globalization Forces Affect Quality of Life." January 25, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/how-globalization-forces-affect-quality-of-life/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "How Globalization Forces Affect Quality of Life." January 25, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/how-globalization-forces-affect-quality-of-life/.

- Threads in Operating Systems and Central Processing Unit

- Photography Exhibition “Threads” in Melbourne

- The Open Systems Interconnection Referencing Model

- Multithreading Models: Definition and Types

- Interconnection Between the Lives of Human Beings and the Internet

- Religion and Morality Interconnection

- Open Systems Interconnection model

- Malware: Code Red Computer Worm

- "Watching TV Makes You Smarter" by Steven Johnson

- Coarse- and Fine-Grained Parallelism

- Effects of Global Stratification

- Globalization: London as a Global City

- Globalization or the Age of Transition

- Globalization Influence on Australia’s Policies

- Globalization and the Dominance of Market-Centered Economic Strategies

Type to search

- Privacy Policy

- Terms And Conditions

How Does Globalization Affect Your Life? The Positive And Negative Effects

Globalization has become part of the modern world, but many are yet to understand how it affects their lives.

People from the U.S. can buy products from China from the comfort of their homes. Communicating with other people thousands of miles away is a breeze. You can even find out about events happening around the world from the comfort of your home. All you need is an internet connection.

Globalization affects every facet of our lives. These include educational system, healthcare, economy, jobs, technology, and others. And shockingly, these impacts could be positive or negative.

So, how does globalization affect your life? Keep reading to find out.

What Globalization Means

When experts say, the world is a global village, what they mean is that people worldwide are connected via various technologies and programs. Before now, it was challenging to communicate with someone thousands of miles away in real-time.

Now, globalization has changed everything. You can interact with whoever you like from the comfort of your home. It’s now easy, quick, and much more convenient.

Over 67.04 percent of the world’s population, which is approximately 5.25 billion people, uses mobile devices.

So, what is globalization ? It’s a term that describes the rising interdependence of the world’s population, economies, and culture caused by cross-border trades, investment flow, information, people, and technology.

Globalization affects all countries, both developed and developing. It also affects everyone positively and negatively. That’s why it’s always a crucial subject for discussion. It has caused many changes and will do more in the future.

How Globalization Affects You Positively

Here are ways globalization has affected your life for the better.

Communication:

Globalization has transformed how the world interacts. Board meetings are via videoconferences, instead of the traditional way of meeting face-to-face. Each board member can live thousands of miles away and still participate in the discussion. Distance is not a barrier.

The only bottleneck would have been having a device that supports videoconference calls and stable internet service. But developed, including many developing countries, have taken care of these problems. Even the developing countries are stepping up.

Imagine if there weren’t devices or software to make such calls and you have to be physically present at the meeting. Embarking on such trips would be expensive, draining, and time-consuming.

Again, imagine what would happen if globalization hadn’t changed the way people communicate or shop online in this trying time. The fight against the spread of COVID-19 would have been more difficult than it already seems.

You can order for anything anywhere in the world and have them delivered to their doorsteps. This also made the sit-at-home order a bit more successful. The internet has also made banking and interacting with customer service agents a breeze.

Finding New Markets:

The focal point in starting a business is making sales. When you make sales, the business grows. Today, anybody can create a new business and find buyers for their products. You can even sell your products to people in different parts of the globe, provided they meet international standards.

So, finding new markets isn’t as difficult as it used to be, thanks to globalization. A manufacturer from China can buy goods from the United States of America and vice versa.

Engaging new talents:

Hiring overseas workers has also gotten a lot easier, thanks to globalization. Job seekers can learn about job opportunities abroad and even apply online. If qualified, employers can arrange call interviews and do the paperwork to bring the right candidate thousands of miles away.

For the records, an employee from a developing country may not earn as much as someone from a developed region. But then, the job opportunities overseas for people in these less developed regions are a welcome development. Employers in these developed regions are also benefiting from the cheap labor.

So, it’s a win-win for employers and job seekers.

Lower product prices:

Globalization has made it possible for manufacturers to find low-cost ways of producing goods. On the other hand, consumers now have a massive variety of choices to make. This helps to ensure satisfaction.

With lower prices, consumers in developing and developed regions can live better, purchasing goods with lesser money.

Makes people aware of global issues:

News about natural disasters and global warming are so easy to obtain. Almost everyone on the planet knows what these dangers are, including the natural disasters taking place in various parts of the world.

None of these would have been possible without globalization. Globalization made the world aware of the 2004 Tsunami that claimed 227,898 lives. Different countries, including the U.K., sent help to the troubled region after learning about the gravity of the damage caused by the natural disaster.

Deforestation, air pollution, and other human activities give rise to global warming. Experts have also warned about the dangers of global warming.

Today, a lot of people are aware of the benefits of tree planting. Governments are almost aiming for zero air pollution in the foreseeable future. Many top companies have started producing electric cars, which doesn’t cause air pollution.

Remote work:

Remote work has made many people consider quitting their 9 to 5 jobs. It has become so attractive, thanks to globalization. Remote jobs are flexible and offer diverse opportunities for people to earn a living.

As a remote worker, you can choose the job you like to do and take breaks without being scolded. This won’t be possible in a 9 to 5 job. Being a remote worker also allows you to manage other side hustles. It gives you a unique opportunity to generate more streams of income.

On the other hand, employers hiring remote workers gain access to a multi-culturally diverse workforce. By hiring remote workers, companies can lower the cost of running an office and improve profit.

Managing remote workers have also gotten a lot easier, thanks to tech advancement. There are programs employers can use to monitor the activities of remote employees. You can check the software at the end of each working day to see how your employees spent their time.

The COVID-19 pandemic halted business activities. Many shops were closed down, and some employees were asked to work from home. And all these were possible because of globalization.

Educational system:

Globalization has also had a massive impact on the educational system. It interconnects teaching systems across the globe. People from other parts of the world can go to school wherever they want.

Many educational tech gadgets are available and make student’s academic life easier. Through the help of these gadgets, students can understand complex subjects and get their assignments done.

You also don’t need to visit the library to have access to academic materials. The internet has virtually almost everything you need. This has also improved the spread of information and awareness about sensitive global issues.

How Globalization Affects You Negatively

Here are the diverse ways globalization is affecting people adversely .

A threat to cultural diverse:

Cultural diversity is what makes us unique as a people. But with globalization transforming every facet of our lives, the world’s cultural diversity is obviously under serious threat.

It is believed that globalization might one day drown out cultures, local economies, and languages. It might mold the world into the image of the capitalist West and North.

Many might be asking how this would happen. But let’s not forget that Hollywood films are replacing local ones in both developing and developed countries. Movies produced in Hollywood are also more likely to gain global success than films made in Bollywood or elsewhere.

Job insecurity:

Globalization has put many workers in fear of job insecurity. Manufacturing companies are now seeking ways to lower production costs. Many companies are also investing in robots, as they aim to use them in place of human labor.

Many companies have also relocated their production departments to countries where they can find cheaper labor.

Robots have taken over most jobs. What’s happening in the automobile industry is a good example.

Dangers of uncontrolled information:

Though globalization has made access to information much easier, the fact that it’s uncontrolled makes it a ticking time bomb. People trust anything they see on social media these days. Only a handful of people do care if such information is from credible sources or not.

We have seen the destructions that misinformation can create. In the U.S., we all witnessed how electoral malpractice talks in the November 2019 presidential election without evidence led to riots and invasion of the Capitol.

Thousands of people have died due to false information. A lot of people have had to evacuate their homes due to false alarms.

Globalization is affecting every facet of our lives, positively and negatively. It affects our economies, education, culture, businesses, and personal lives.

However, we must make proper use of every available tool globalization has given us to improve our lives and society. Students should take advantage of educational gadgets to enhance their academic performance. Those in business should also do the same.

Leave a Comment Cancel Comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Recent Posts

Popular Posts

Trending & Hot

- Business Essentials

- Leadership & Management

- Credential of Leadership, Impact, and Management in Business (CLIMB)

- Entrepreneurship & Innovation

- Digital Transformation

- Finance & Accounting

- Business in Society

- For Organizations

- Support Portal

- Media Coverage

- Founding Donors

- Leadership Team

- Harvard Business School →

- HBS Online →

- Business Insights →

Business Insights

Harvard Business School Online's Business Insights Blog provides the career insights you need to achieve your goals and gain confidence in your business skills.

- Career Development

- Communication

- Decision-Making

- Earning Your MBA

- Negotiation

- News & Events

- Productivity

- Staff Spotlight

- Student Profiles

- Work-Life Balance

- AI Essentials for Business

- Alternative Investments

- Business Analytics

- Business Strategy

- Business and Climate Change

- Design Thinking and Innovation

- Digital Marketing Strategy

- Disruptive Strategy

- Economics for Managers

- Entrepreneurship Essentials

- Financial Accounting

- Global Business

- Launching Tech Ventures

- Leadership Principles

- Leadership, Ethics, and Corporate Accountability

- Leading with Finance

- Management Essentials

- Negotiation Mastery

- Organizational Leadership

- Power and Influence for Positive Impact

- Strategy Execution

- Sustainable Business Strategy

- Sustainable Investing

- Winning with Digital Platforms

4 Effects of Globalization on the Environment

- 15 Apr 2021

Globalization —defined in the online course Global Business as the increased flow of goods, services, capital, people, and ideas across international boundaries—has brought many changes in its wake.

While globalization can positively and negatively impact society, its effect on the environment is primarily negative. Here’s a breakdown of how globalization impacts society and the environment and what business leaders can do to reduce these negative consequences.

How Does Globalization Affect Society?

The world has become more connected than ever before through the increase in technological advancements and economic integrations. Advanced economies are formed as domestic businesses transform into international ones and further contribute to the spread of technology around the world.

There are several benefits of globalization , such as increased international trade and cooperation and less international aggression. Social globalization —the sharing of ideas and information between countries—has led to innovation in the medical, technological, and environmental preservation industries.

Additionally, globalization has improved the quality of life in several developing nations. This includes implementing efficient transportation systems and ensuring accessibility to services such as education and healthcare.

However, globalization can also have negative effects on society, such as increased income inequality and substandard working conditions in developing countries that produce goods for wealthier nations. Income inequality is directly related to globalization as it further increases the gap between more advanced and developing areas of a nation. As a result, it can also increase the risk of societal violence.

Along with its societal effects, globalization has a lasting impact on the environment—and typically not a positive one.

Access your free e-book today.

What Are the Effects of Globalization on the Environment?

1. Increased Transport of Goods

One of the primary results of globalization is that it opens businesses up to new markets in which they can sell goods and source labor, raw materials, and components.

Both of these realities mean finished products travel farther now than ever before—potentially halfway around the globe. In the past, products were more likely to be produced, sold, and consumed locally. This increased transport of goods can impact the environment in several ways, including:

- Increased emissions: The farther a product travels, the more fuel is consumed, and a greater level of greenhouse gas emissions is produced. According to a report by the International Transport Forum , CO2 emissions from transport will increase 16 percent by 2050. These emissions contribute to pollution, climate change , and ocean acidification around the world and have been shown to significantly impact biodiversity.

- Habitat destruction: Transportation—especially when land-based—requires infrastructure like roads and bridges. The development of such infrastructure can lead to issues including habitat loss and pollution. The more ships that travel by sea, the greater the chances for major oil spills or leaks that damage the delicate marine environment.

- Invasive species: Every shipping container and vessel presents an opportunity for a living organism—from plants to animals to fungus—to hitch a ride to a new location where it can become invasive and grow without checks and balances that might be present in its natural environment.

2. Economic Specialization

One often-overlooked side effect of globalization is that it allows nations and geographical regions to focus on their economic strengths while relying on trading partners for goods they don’t produce themselves. This economic specialization often boosts productivity and efficiency.

Unfortunately, overspecialization can threaten forest health and lead to serious environmental issues, often in the form of habitat loss, deforestation, or natural resource overuse. A few examples include:

- Illegal deforestation in Brazil due to an increase in the country’s cattle ranching operations, which requires significant land for grazing

- Overfishing in coastal areas that include Southeast Asia, which has significantly contributed to reduced fish populations and oceanic pollution

- Overdependence on cash crops, such as coffee, cacao, and various fruits, which has contributed to habitat loss, especially in tropical climates

It’s worth considering that globalization has allowed some nations to specialize in producing various energy commodities, such as oil, natural gas, and timber. Nations that depend on energy sales to fund a large portion of their national budgets, along with those that note “energy security” as a priority, are more likely to take intervening actions in the market in the form of subsidies or laws that make transitioning to renewable energy more difficult.

The main byproduct of these energy sources comes in the form of greenhouse gas emissions, which significantly contribute to global warming and climate change.

3. Decreased Biodiversity

Increased greenhouse gas emissions, ocean acidification, deforestation (and other forms of habitat loss or destruction), climate change, and the introduction of invasive species all work to reduce biodiversity around the globe.

According to the World Wildlife Fund’s recent Living Planet Report , the population sizes of all organisms—including mammals, birds, fish, amphibians, and reptiles—have decreased 68 percent since 1970. Latin America and Africa—two rapidly developing regions important to global trade—have seen disproportionate levels of biodiversity loss, especially among environmentally sensitive fish, reptiles, and amphibians.

While this decrease in biodiversity has many causes, it’s widely believed that the issues listed above have contributed in part.

4. Increased Awareness

While many of globalization’s environmental effects have been negative, its increase has heightened environmental awareness worldwide.

Greater connectivity and higher rates of international travel have made it easier than ever for individuals to see the effects of deforestation, habitat loss, and climate change on the environment. This, in turn, has contributed to new laws, regulations, and processes that limit negative effects.

Globalization as a Threat and an Opportunity

Globalization has allowed society to enjoy many benefits, including increased global cooperation, reduced risk of global conflict, and lower prices for goods and commodities. Unfortunately, it’s also led to serious negative effects on the environment.

Since it isn’t feasible for globalization to end or reverse, it’s likely the situation will worsen until nations, governing bodies, and other organizations are compelled to implement laws and regulations that limit negative effects.

Businesses and industries that operate globally have an incentive to take whatever voluntary actions they can to reduce the potential for negative consequences. Doing so can not only provide an organization greater control over its initiatives, but also a powerful marketing and communication tool .

Some ways businesses address climate change include:

- Transitioning to renewable energy sources

- Choosing greener infrastructures or equipment

- Reducing energy consumption

- Creating credible climate transition plans

- Raising awareness among employees

In addition, investing in renewable energy and packaging, embracing responsible land-use management, and shifting goods production to move closer to the end customer are all viable options that businesses can and should consider. The challenge lies in balancing a desire to embrace corporate social responsibility with the need to turn a profit and run a successful business.

Are you interested in breaking into a global market? Sharpen your knowledge of the international business world with our four-week Global Business course. In addition, explore our Business and Climate Change course to help your organization adapt to and embrace business risks and opportunities created by climate change, as well as our other online courses related to business in society .

This post was updated on February 28, 2024. It was originally published on April 15, 2021.

About the Author

Globalization, Supranational Dynamics and Local Experiences pp 1–40 Cite as

Introduction: Globalization between Theories and Daily Life Experiences

- Marco Caselli 4 &

- Guia Gilardoni 5

- First Online: 04 November 2017

563 Accesses

Part of the book series: Europe in a Global Context ((EGC))

Though a wide range of scientific studies have been published on the topic of globalization, seemingly analyzed to the smallest detail, discussion of this issue is neither commonplace nor easy. Analysis of globalization is never done, as the process is undergoing continuous transformation along development trends that are neither linear nor predictable in advance. In addition, analysis of it is not easy, given that the term globalization has been used with different meanings in several frameworks, both scientific and otherwise (Fiss and Hirsch 2005). But, even considering a single discipline such as sociology, we find that it has not assigned a univocal meaning to the topic, and analyses of the underlying processes of globalization are conducted according to radically different perspectives and interpretations. Hence, there is no general consensus on the concept’s definition, its confines, and even, at least in part, its basic characteristics. Finally, as underscored by Scholte (2005: 46) with a good dose of irony, “the only consensus about globalization is that it is contested”.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution .

http://gmdac.iom.int/global-migration-trends-factsheet

https://missingmigrants.iom.int/mediterranean

http://heindehaas.blogspot.it/2016/08/the-case-for-border-controls.html

Art. 2(l) of Directive 2011/95/EU (Recast Qualification Directive).

Eurostat, Migration and Migrant Population Statistics, data extracted in May 2016, http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php/Migration_and_migrant_population_statistics

https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2015/12/10-migration-trends-to-look-out-for-in-2016/

http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2016/12/20/angela-merkel-shocked-saddened-berlin-christmas-market-attack/

Acosta Arcarazo, D. (2014, 1/July–October). EU integration policy: Between soft law and hard law. KING Desk Research Paper & In-Depth Study .

Google Scholar

Adam, B. (1998). Timescape of modernity . London: Routledge.

Albrow, M. (1996). The global age . Cambridge: Polity.

Anderson, B. (1983). Imagined communities. Reflections on the origin and spread of nationalism . London and New York: Verso.

Anderson, N. (1923). The hobo: The sociology of the homeless man . Chicago: University Press.

Appadurai, A. (1990). Disjuncture and difference in the global cultural economy. In M. Featherstone (Ed.), Global culture . London: Sage.

Arrighi, G. (1994). The long twentieth century . London: Verso.

Augé, M. (1992). Non-lieux . Paris: Seuil.

Axford, B. (2013). Theories of globalization . Cambridge: Polity.

Back, L. (1996). New ethnicities and urban culture. Racism and multiculture in young lives . London: UCL Press.

Bauman, Z. (1998). Globalization: The human consequences . Cambridge: Polity.

Baumann, G. (1996). Contesting culture. Discourses of identity in multi-ethnic London . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Beck, U. (1992). Risk society. Towards a new modernity . London: Sage.

Beck, U. (2000a). The cosmopolitan perspective: Sociology of the second age of modernity. British Journal of Sociology, 51 (1), 79–105.

Beck, U. (2000b). What is globalization? Cambridge: Polity.

Beck, U. (2004). Der kosmopolitische Blick order: Krieg ist Frieden . Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp Verlag.

Beck, U. (2005). Power in the global age . Cambridge: Polity.

Beck, U. (2006). Cosmopolitan vision . Cambridge: Routledge.

Billing, M. (1997). Banal nationalism . London: Sage.

Breindenbach, J., & Zukrigl, I. (2000). Cultural battle or McWorld? Deutschland, 3 , 40–43.

Caselli, M. (2012). Trying to measure globalization. Experiences, critical issues and perspectives . Dordrecht: Springer.

Castles, S., de Haas, H., & Miller, M. J. (Eds.). (2014). The age of migration. International population movements in the modern world (5th ed.). Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Castles, S., & Miller, M. J. (Eds.). (2009). The age of migration. International population movements in the modern world (4th ed.). Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Cohen, R. (2007). Creolization and cultural globalization: The soft sounds of fugitive power. Globalizations, 4 (2), 369–385.

Cowen, T. (2002). Creative destruction . Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Fiss, P. C., & Hirsch, P. M. (2005). The discourse of globalization: Framing and sensemaking of an emerging concept. American Sociological Review, 70 , 29–52.

Gallino, L. (2004). Dizionario di sociologia . Torino: Utet.

García Canclini, N. (1995). Hybrid cultures: Strategies for entering and leaving modernity . Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Giaccardi, C., & Magatti, M. (2001). La globalizzazione non è un destino . Roma-Bari: Laterza.

Giddens, A. (1990). The consequences of modernity . Cambridge: Polity.

Giddens, A. (1996). Beyond left and right . Cambridge: Polity.

Giddens, A. (2000). Runaway world. How globalization is reshaping our lives . New York: Routledge.

Gilardoni, G., D’Odorico, M., & Carrillo, D. (2015). King-knowledge for integration governance. Evidence on migrants’ integration in Europe . Milan: Fondazione Ismu. Retrieved from http://king.ismu.org/wp-content/uploads/KING_Report.pdf .

Gill, S. (1992). Economic globalization and the internationalization of authority. Geoforum, 23 , 269–283.

Gilroy, P. (1993). The Black Atlantic: Modernity and double consciousness . Harvard: University Press.

Glick Schiller, N., Basch, L., & Blanc-Szanton, C. (1992). Transnationalism: A new analytic framework for understanding migration . New York: Annals of the Academy of Science.

Gobo, G. (2011). Glocalizing methodology? The encounter between local methodologies. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 14 (6), 417–437.

Hall, S. (1991). The local and the global: Globalization and ethnicity. In A. King (Ed.), Culture, globalization and the world-system (pp. 19–39). London: Macmillan.

Hannerz, U. (1992). Global complexity . New York: Columbia University Press.

Harvey, D. (1990). The condition of postmodernity . Oxford: Blackwell.

Hay, C., & Marsh, D. (Eds.). (2000). Demystifying globalisation . London: Macmillan.

Held, D., & McGrew, A. (2007). Introduction: Globalization at risk? In D. Held & A. McGrew (Eds.), Globalization theory. Approaches and controversies . Cambridge: Polity.

Helliwell, J. F. (2000). Globalization: Myths, facts and consequences . Toronto: C.D. Howe Institute.

Hirst, P., & Thompson, G. (1996). Globalization in question: The international economy and the possibilities of governance . Cambridge: Polity.

Holton, R. J. (2005). Making globalization . Basingstoke: Palgrave.

Hoogvelt, A. (1997). Globalisation and the postcolonial world. The new political economy of development . London: Macmillan.

Hopkins, A. G. (2002). The history of globalization—And the globalization of history? In A. G. Hopkins (Ed.), Globalization in world history . New York: Norton.

Huges, E., & Huges, H. (1952). Where peoples meet: Racial and ethnic frontiers . Chicago: Free Press.

Huntington, S. P. (1993). The clash of civilisations? Foreign Affairs, 72 (3), 22–49.

Inglehart, R., & Norris, P. (2009). Cosmopolitan communications: Cultural diversity in a globalized world . New York: Cambridge University Press.

IOM—Global Migration Data Analysis Centre (GMDAC). (2015). How the world views migration. Retrieved from http://publications.iom.int/books/how-world-views-migration

Kaldor, M. (1999). New and old wars: Organized violence in a global era . Cambridge: Polity.

Kennedy, P. (2010). Local lives and global transformation. Towards world society . Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

King, A. (1991). Culture, globalization and the world-system. Contemporary conditions for the representation of identity . Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Lash, S., & Urry, J. (1994). Economics of sign and space . London: Sage.

Levitt, P. (2001). The transnational villagers . Berkeley: University of California Press.

Levitt, T. (1983, May–June). The globalization of markets. Harvard Business Review, 61 , 92–102.

Ley, D. (2004). Transnational spaces and everyday lives. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 29 (2), 151–164.

Martell, L. (2007). The third wave in globalization theory. International Studies Review, 9 , 173–196.

Martin, D., Metzger, J. L., & Pierre, P. (2006). The sociology of globalization. Theoretical and methodological reflections. International Sociology, 21 (4), 499–521.

Mc Grew, A. (2007). Organized violence in the making (and remaking) of globalization. In D. Held & A. McGrew (Eds.), Globalization theory. Approaches and controversies . Cambridge: Polity.

Meyer, J. W. (2007). Globalization: Theory and trends. International Journal of Comparative Sociology, 48 (4), 261–273.

Miller, D., & Walzer, M. (1995). Pluralism, justice and equality . Oxford: University Press.

Ngongi, N. A. (2001) Lotta alla povertà e all’esclusione nel contesto dell’economia globale. In R. Papini (a cura di) Globalizzazione: solidarietà o esclusione? Napoli: Edizioni scientifiche Italiane.

O’Brien, R. (1992). Global financial integration: The end of geography . New York: Council on Foreign Relations Press.

Ohmae, K. (1990). The borderless world: Power and strategy in the interlinked economy . London: Collins.

Ohmae, K. (1995). The end of the nation-state: The rise of regional economies . New York: Simon and Schuster.

O’Rourke, K., & Williamson, J. (1999). Globalization and history . Cambridge: MIT Press.

Park, R. E. (1921). Introduction to a science of sociology . Chicago: University Press.

Penninx, R., Kraal, A., Martiniello, M., & Vertovec, S. (Eds.). (2004). Citizenship in European cities . Aldershot: Ashgate.

Petrella, R. (1995) Presentation to the conference “Gestion locale et régionale des transformations économiques, technologiques et environnementales”. Organised by the French Commission for UNESCO, Fondation Maison des Sciences de l’Homme, and the French Ministry for Higher Education and Research.

Pieterse, J. N. (2003). Globalization and culture: Global mélange . Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield.

Pieterse, J. N. (2009). Globalization and culture: Global mélange (2nd ed.). Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield.

Racine, J. L. (2001). On globalisation: Beyond the paradigm. States and civil societies in the global and local context. In R. S. Melkote (Ed.), Meanings of globalisation: Indian and French perspectives . New Delhi: Sterling Publishers.

Ray, L. (2007). Globalization and everyday life . Abingdon: Routledge.

Reich, B. (1991). The work of nations: Preparing ourselves for 21st century capitalism . New York: Vintage Books.

Risse, T. (2007). Social constructivism meets globalization. In D. Held & A. McGrew (Eds.), Globalization theory. Approaches and controversies . Cambridge: Polity.

Ritzer, G. (2006). The globalization of nothing 2 . Thousand Oaks: Pine Forge Press.

Robertson, R. (1992). Globalization: Social theory and global culture . London: Sage.

Robertson, R. (1994). Globalization or glocalization? The Journal of International Communication, 1 (1), 33–52.

Robertson, R. (1995). Glocalization: Time-space and homogeneity-heterogeneity. In M. Featherstone, S. Lash, & R. Robertson (Eds.), Global modernities . London: Sage.

Robertson, R., & Inglis, D. (2004). Beyond the gates of the polis : Reworking the classical roots of classical sociology. Journal of Classical Sociology, 4 (2), 165–189.

Rosenberg, J. (2005). Globalization theory: A post mortem. International Politics, 42 , 2–74.

Roudometof, V. (2016). Glocalization. A critical introduction . Abingdon: Routledge.

Said, E. W. (1978). Orientalism . New York: Pantheon.

Sassen, S. (1991). The global city: New York, London, Tokio . Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Sassen, S. (2000). New frontiers facing urban sociology at the Millennium. British Journal of Sociology, 51 (1), 143–159.

Sassen, S. (2007). The places and spaces of the global: An expanded analytic terrain. In D. Held & A. McGrew (Eds.), Globalization theory. Approaches and controversies . Cambridge: Polity.

Scholte, J. A. (2000). Globalization. A critical introduction . Basingstoke: Palgrave.

Scholte, J. A. (2005). Globalization. A critical introduction (2nd ed.). Basingstoke: Palgrave.

Schunk, R. (2014). Transnational activities and immigrant integration in Germany. Concurrent or competitive process? Cham, Switzerland: Springer.

Sen, A. (2002). Globalizzazione e libertà . Milano: Mondadori.

Simmel, G. (1968). Sociologia . Torino: Edizioni Comunità.

Sklair, L. (1991). Sociology of the global system . Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press.

Sklair, L. (1999). Competing conceptions of globalization. Journal of World-Systems Research, 5 (2), 143–163.

Smith, A. D. (1995). Nations and nationalism in a global era . Cambridge: Polity.

Taylor, C. (1992). Multiculturalism and the politics of recognition . Princeton: Amy Gutmann.

Thomas, W. I., & Znaniecki, F. (1918). The Polish peasant in Europe and America . Boston: Gorham.

Tomlinson, J. (1999). Globalization and culture . Cambridge: Polity.

Tomlinson, J. (2007). Globalization and cultural analysis. In D. Held & A. McGrew (Eds.), Globalization theory. Approaches and controversies . Cambridge: Polity.

Turner, B., & Khonder, H. (2010). Globalization: East and West . London: Sage.

UNHCR. (2016, December). Bureau of Europe, refugees & migrants sea arrivals in Europe . Retrieved from http://data.unhcr.org/mediterranean/regional.php

Wade, R. (1996). Globalization and its limits: Reports of the death of the national economy are greatly exaggerated. In S. Berger & R. Dore (Eds.), National diversity and global capitalism . Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Wiewiorka, M. (1998). Is multiculturalism the solution? Ethnic and Racial Studies, 21 (5), 881–910.

Wiewiorka, M. (2001). La diffèrence . Paris: Balland.

Zorbaugh, H. (1929). The gold coast and the slum . Chicago: University Press.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Dipartimento di Sociologia, Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore, Milano, Italy

Marco Caselli

Fondazione ISMU, Milano, Italy

Guia Gilardoni

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

ISMU Foundation, Milano, Italy

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2018 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter.

Caselli, M., Gilardoni, G. (2018). Introduction: Globalization between Theories and Daily Life Experiences. In: Caselli, M., Gilardoni, G. (eds) Globalization, Supranational Dynamics and Local Experiences . Europe in a Global Context. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-64075-4_1

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-64075-4_1

Published : 04 November 2017

Publisher Name : Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-319-64074-7

Online ISBN : 978-3-319-64075-4

eBook Packages : Social Sciences Social Sciences (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Open access

- Published: 20 May 2021

How does globalization affect COVID-19 responses?

- Steve J. Bickley 1 , 2 ,

- Ho Fai Chan ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-7281-5212 1 , 2 ,

- Ahmed Skali 3 ,

- David Stadelmann 2 , 4 , 5 &

- Benno Torgler 1 , 2 , 5

Globalization and Health volume 17 , Article number: 57 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

264k Accesses

29 Citations

69 Altmetric

Metrics details

The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the vast differences in approaches to the control and containment of coronavirus across the world and has demonstrated the varied success of such approaches in minimizing the transmission of coronavirus. While previous studies have demonstrated high predictive power of incorporating air travel data and governmental policy responses in global disease transmission modelling, factors influencing the decision to implement travel and border restriction policies have attracted relatively less attention. This paper examines the role of globalization on the pace of adoption of international travel-related non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs) during the coronavirus pandemic. This study aims to offer advice on how to improve the global planning, preparation, and coordination of actions and policy responses during future infectious disease outbreaks with empirical evidence.

Methods and data

We analyzed data on international travel restrictions in response to COVID-19 of 185 countries from January to October 2020. We applied time-to-event analysis to examine the relationship between globalization and the timing of travel restrictions implementation.

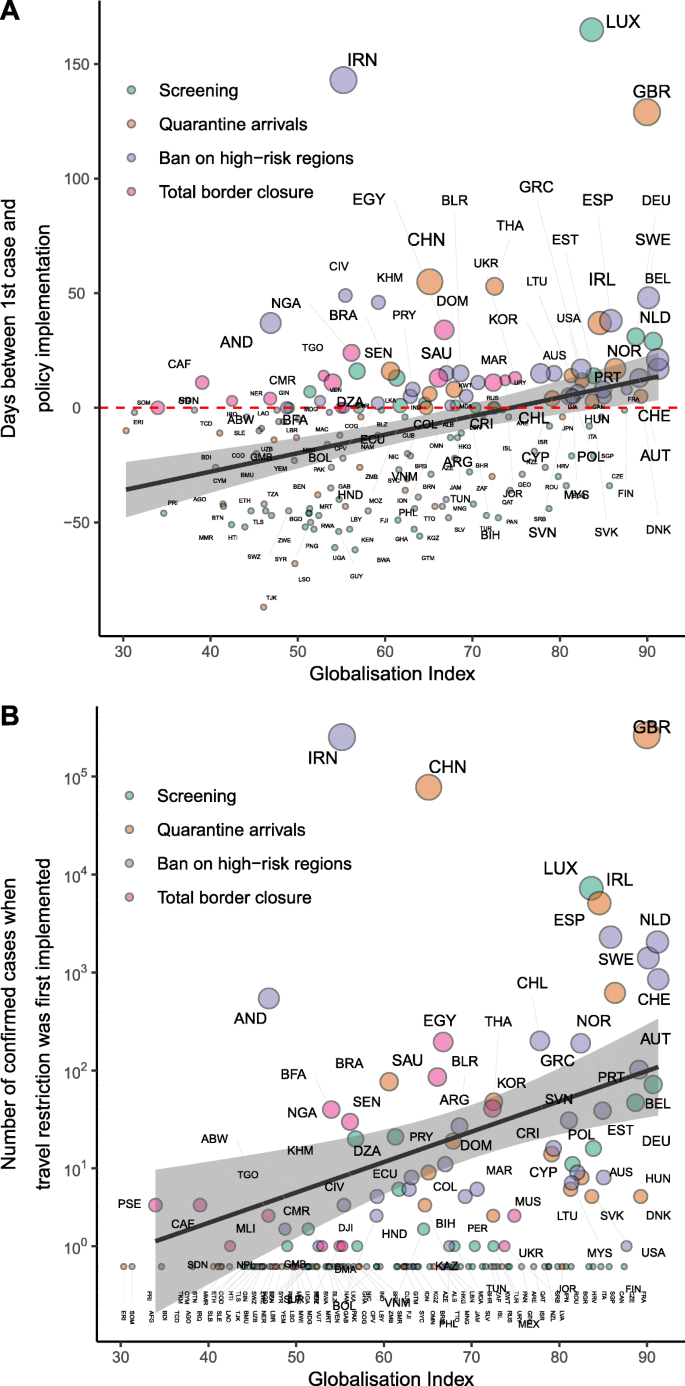

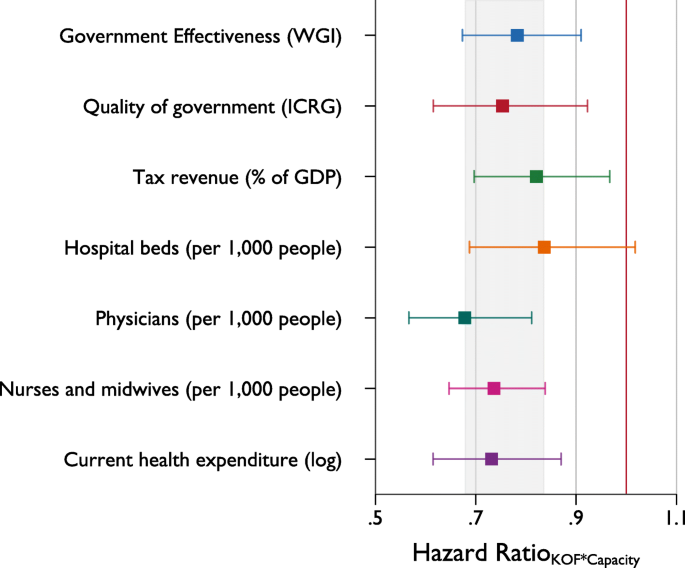

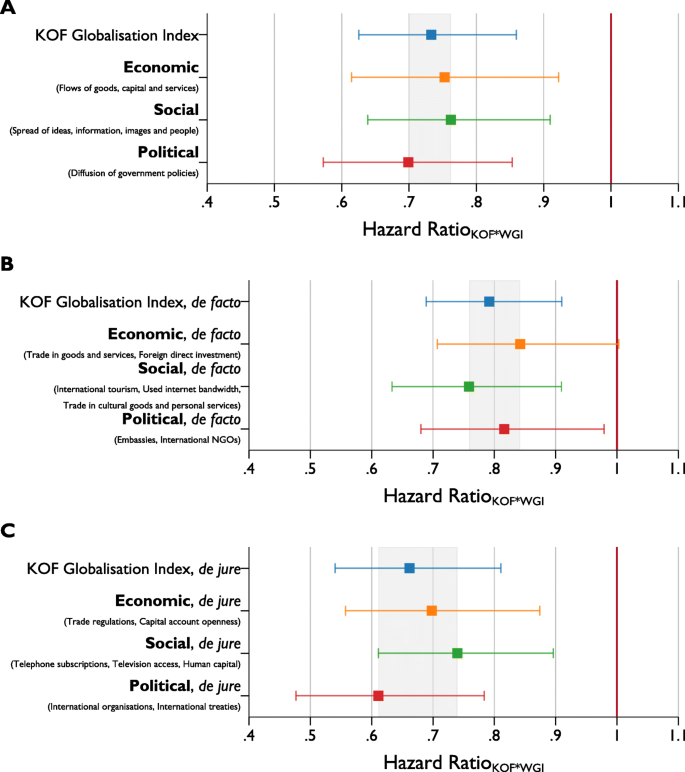

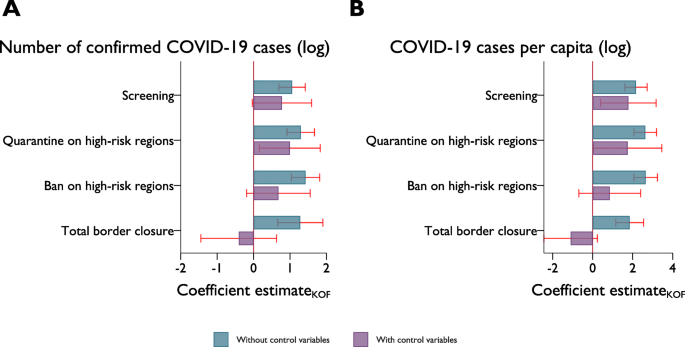

The results of our survival analysis suggest that, in general, more globalized countries, accounting for the country-specific timing of the virus outbreak and other factors, are more likely to adopt international travel restrictions policies. However, countries with high government effectiveness and globalization were more cautious in implementing travel restrictions, particularly if through formal political and trade policy integration. This finding is supported by a placebo analysis of domestic NPIs, where such a relationship is absent. Additionally, we find that globalized countries with high state capacity are more likely to have higher numbers of confirmed cases by the time a first restriction policy measure was taken.

Conclusions

The findings highlight the dynamic relationship between globalization and protectionism when governments respond to significant global events such as a public health crisis. We suggest that the observed caution of policy implementation by countries with high government efficiency and globalization is a by-product of commitment to existing trade agreements, a greater desire to ‘learn from others’ and also perhaps of ‘confidence’ in a government’s ability to deal with a pandemic through its health system and state capacity. Our results suggest further research is warranted to explore whether global infectious disease forecasting could be improved by including the globalization index and in particular, the de jure economic and political, and de facto social dimensions of globalization, while accounting for the mediating role of government effectiveness. By acting as proxies for a countries’ likelihood and speed of implementation for international travel restriction policies, such measures may predict the likely time delays in disease emergence and transmission across national borders.

The level of complexity around containing emerging and re-emerging infectious diseases has increased with the ease and increased incidence of global travel [ 1 ], along with greater global social, economic, and political integration [ 2 ]. In reference to influenza pandemics, but nonetheless applicable to many communicable and vector-borne diseases, the only certainty is in the growing unpredictability of pandemic-potential infectious disease emergence, origins, characteristics, and the biological pathways through which they propagate [ 3 ]. Globalization in trade, increased population mobility, and international travel are seen as some of the main human influences on the emergence, re-emergence, and transmission of infectious diseases in the twenty-first Century [ 4 , 5 ].

Emerging and re-emerging infectious diseases have presented major challenges for human health in ancient and modern societies alike [ 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 ]. The relative rise in infectious disease mortality and shifting patterns of disease emergence, re-emergence, and transmission in the current era has been attributed to increased global connectedness, among other factors [ 11 ]. More globalized countries – and, in particular, global cities – are at the heart of human influence on infectious diseases; these modern, densely populated urban centers are highly interconnected with the world economy in terms of social mobility, trade, and international travel [ 12 , 13 ]. One might assume that given their high susceptibility to infectious diseases, globalized countries would be more willing than less globalized countries to adopt screening, quarantine, travel restriction, and border control measures during times of mass disease outbreaks. However, given their globalized nature, globalized countries are also likely to favor less protectionist policies in general, thus, contradicting the assumption above, perhaps suggesting that counteracting forces are at play: greater social globalization may require faster policy adoption to limit potential virus import and spread through more socially connected populations [ 14 , 15 ]; greater economic globalization may indicate slower policy adoption due to legally binding travel and trade agreements/regulations, economic losses, and social issues due to family relations that cross borders [ 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 ]. Greater political globalization may indicate greater willingness to learn from others and/or maintain democratic processes of decision making in global coordination efforts, either way potentially delaying the implementation of travel restrictions. Travel restrictions may also have minimal impact in urban centers with dense populations and travel networks [ 22 ]. Moreover, the costs of closing are comparatively higher for open countries than for already protective nations. For example, more globalized countries are more likely to incur financial or economic penalties (e.g., see [ 23 , 24 ]) when implementing health policies which aim to improve the health of local populations such as import restrictions or bans on certain food groups/products and product labelling. Globalization, after all, is known to promote growth and does so via a combination of three main globalization dimensions: economic integration (i.e., flow of goods, capital and services, economic information, and market perceptions), social integration (i.e., proliferation of ideas, information, culture, and people), and political integration (i.e., diffusion of governance and participation in international coordination efforts) [ 25 , 26 ]. See Table 1 for examples of data used in the estimation of each (sub)dimension of the KOF globalization index we use in this study.

Globalization appears to improve population health outcomes such as infant mortality rate (IMR) and life expectancy (LE) regardless of a country’s level of development (i.e., developed, developing, or underdeveloped) [ 27 , 28 ]. Links between the dimensions of globalization (i.e., social, political, and economic) and general population health are less clear cut [ 29 ]. For less developed countries, the economic dimension of globalization appears to provide the strongest determinant in IMR and LE, whereas for more developed countries, the social aspect of globalization is the strongest factor [ 27 ]. This suggests that as a country becomes more economically stable, it then moves towards greater social and political integration into global society; and for less developed countries, increased wealth creation through economic integration potentially delivers the greatest increases in population health. In contrast, for low- to middle-income countries, the social and political dimensions of globalization appear most strongly related to the propensity of women to be overweight [ 30 , 31 ]. This suggests that for the least developed countries, the adoption of western culture, food habits and lifestyle may be detrimental to adult health if not backed up by social and political progress. Hence, it appears there is no definite relationship between the different aspects of globalization (i.e., social, political, and economic), a country’s level of development, and health outcomes that hold across all health contexts. Regardless, trade policies and more generally, globalization, influence both a nation’s determinants of health and the options and resources available to its health policymakers [ 32 ].

The influence of open trade agreements, policies favoring globalization and greater social connectedness on the (delayed) timing of travel restrictions during a pandemic would make logical sense. Globalized countries are more likely to incur financial, economic, and social penalties by implementing restrictive measures that aim to improve population health outcomes (e.g., see [ 23 , 24 ]) and hence, will be less inclined to do so. Further, countries that rely on international students and tourism and have a high number of expatriates living and working abroad might be even less likely to close their borders or implement travel restrictions to avoid (1) increases in support payments or decreases in tax income during times of unforeseen economic upset, (2) negative backlash from media and in political polls, and (3) tit-for-tat behaviors from major trading partners. However, countries which are more socially connected may also act more quickly because they are inherently at higher risk of local outbreak and hence, to delay local emergence they may implement international travel restrictions earlier. Membership and commitments to international organizations [ 33 ], treaties, and binding trade agreements might also prevent or inhibit them from legally doing so [ 23 , 34 , 35 ], suggesting there are social, trade, and political motivators to maintain ‘open’ borders.

Domestic policies implemented in response to the coronavirus pandemic have ranged from school closures and public event cancellations to full-scale national lockdowns. Previous research has hinted that democratic countries, particularly those with competitive elections, were quicker to close schools. Interestingly, those with high government effectiveness (i.e., those with high-quality public and civil services, policy formulation, and policy implementation) were slower to implement such policies [ 36 ] as were the more right-leaning governments [ 37 ]. Further, more democratic countries have tended to be more sensitive to the domestic policy decisions of other countries [ 38 ]. In particular, government effectiveness – as a proxy of state capacity – can act as a mediator with evidence available that countries with higher effectiveness took longer to implement COVID-19 related responses [ 36 , 39 ]. Countries with higher levels of health care confidence also exhibit slower mobility responses among its citizens [ 40 ]. Those results may indicate that there is a stronger perception that a well-functioning state is able to cope with such a crisis as a global pandemic like SARS-CoV-2. More globalized countries may therefore take advantage of a better functioning state; weighing advantages and disadvantages of policies and, consequently, slowing down the implementation of restrictive travel policies to benefit longer from international activities. Regardless, the need to understand the reasons (and potential confounding or mediating factors) behind the selection of some policy instruments and not others [ 36 ] and the associated timing of such decisions is warranted to enable the development and implementation of more appropriate policy interventions [ 41 ].

The literature seems to agree that greater globalization (and the trade agreements and openness which often come with it) make a country more susceptible to the emergence and spread of infectious and noncommunicable diseases [ 2 , 42 ]. Greater connectedness and integration within a global society naturally increases the interactions between diverse populations and the pathways through which potential pathogens can travel and hence, emerge in a local population. Non-pharmaceutical interventions (e.g., social distancing, city lockdowns, travel restrictions) may serve as control measures when pharmaceutical options (e.g., vaccines) are not yet available [ 43 ]. However, such non-pharmaceutical measures are often viewed as restrictive in a social, political, and economic context. Our review of the literature did not detect clear indications of the likelihood that globalized cities will implement such measures, nor were we able to identify how quickly such cities will act to minimize community transmission of infectious diseases and the possible mediating effects of government effectiveness in the decision-making process. Furthermore, our review could not locate research on the relative influence of the social, political, and economic dimensions of globalization on the speed of implementing travel restriction policies. The recent COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the vast differences in approaches to the control and containment of coronavirus across the world and has demonstrated the varied success of such approaches in minimizing the transmission of coronavirus. Restrictive government policies formerly deemed impossible have been implemented within a matter of months across democratic and autocratic governments alike. This presents a unique opportunity to observe and investigate a plethora of human behavior and decision-making processes. We explore the relative weighting of risks and benefits in globalized countries who balance the economic, social, and political benefits of globalization with a higher risk of coronavirus emergence, spread, and extended exposure. Understanding which factors of globalization (i.e., social, economic, or political) have influenced government public health responses (in the form of travel/border restriction policies) during COVID-19 can help identify useful global coordination mechanisms for future pandemics, and also improve the accuracy of disease modelling and forecasting by incorporation into existing models.

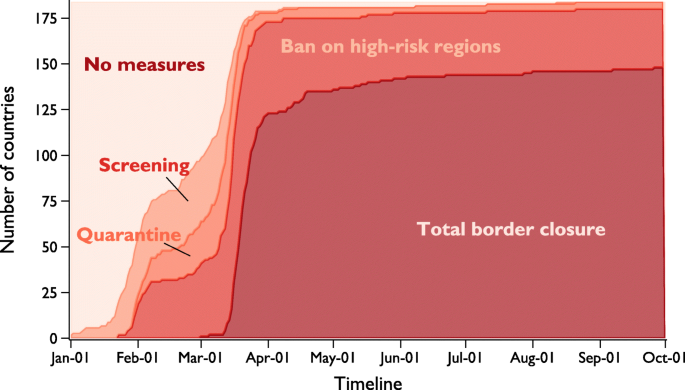

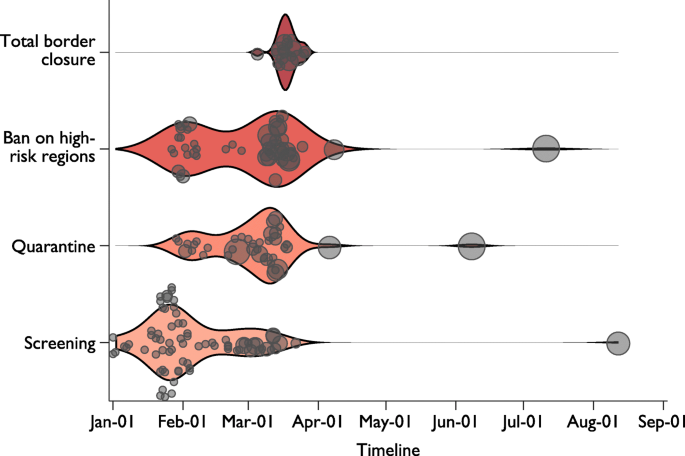

Key variables

The record for each country’s international travel policy response to COVID-19 is obtained from the Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker (OxCGRT) database [ 44 ] (185 countries in total). The database records the level of strictness on international travel from 01 January 2020 to the present (continually updated), categorized into five levels: 0 - no restrictions; 1 - screening arrivals; 2 - quarantine arrivals from some or all regions; 3 - ban arrivals from some regions; and 4 - ban on all regions or total border closure. At various points in time from the beginning of 2020 to the time of writing (06 October 2020), 102 countries have introduced a policy of screening on arrival, 112 have introduced arrival quarantine, 152 have introduced travel bans, and 148 have introduced total border closures. Footnote 1 A visual representation of these statistics in Fig. 1 shows the cumulative daily count of countries that have adopted a travel restriction, according to the level of stringency, between 01 January and 01 October 2020. Countries with a more restrictive policy (e.g., total border closure) and countries with less restrictive policies (e.g., ban on high-risk regions) are also counted. Figure 2 then shows the type of travel restriction and the date each country first implemented that policy. Together, we see that countries adopted the first three levels of travel restrictions in two clusters; first between late January to early February, and second during mid-March, around the time that COVID-19 was declared a pandemic by the WHO. Total border closures, on the other hand, were mainly imposed after the pandemic declaration, except for two countries that went into lockdown at the beginning of March (i.e., State of Palestine, and San Marino). Country-specific timelines are shown in Fig. S 1 in the Appendix.

Timeline of international travel restriction policy adoption for 184 countries. Daily count shows the cumulative number of countries that have introduced an international travel policy that is ‘at-least-as-strict’. Relaxation of international travel restriction is not shown in the figure

Restrictiveness of the first travel policy implemented over time. Each marker ( N = 183) represents the type and date of the first travel restriction adopted, with the size of the marker representing the number of confirmed COVID cases at the time of policy implementation. Violin plot shows the kernel (Gaussian) density of timing of implementation

We obtained COVID-19 statistics from the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) and the COVID-19 Data Repository by the Center for Systems Science and Engineering (CSSE) at Johns Hopkins University [ 45 ]. The dataset consists of records on the number of confirmed cases and deaths daily for 215 countries since January 2020.

Our measure of globalization is generated from the KOF Globalization Index (of more than 200 countries for the year 2017), published by the KOF Swiss Economic Institute Footnote 2 [ 26 ]. The KOF Globalization Index is made up of 44 individual variables (24 de facto and 20 de jure components) relating to globalization across economic, social, and political factors Footnote 3 , Footnote 4 (see also [ 25 ]). The complete index is calculated as the average of the de facto and the de jure globalization indices. We focus this analysis on the overall index, as well as the subdimensions of globalization (i.e., Economic (Trade and Financial), Social (Interpersonal, Informational, and Cultural), and Political globalization). Additionally, we also investigate the relative contributions of the de facto and de jure indices separately. Each index ranges from 1 to 100 (highest globalization). In the regression models, we standardize the variable to mean of zero with unit variance for effect size comparison.

Countries with no records of travel restriction adoption (not included in the Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker) and globalization data from the KOF Globalization Index are listed in Tables S 1 and S 2 , respectively. Footnote 5

Control variables

When analyzing the timing of international travel restrictions, we take into account how such decisions can be affected by the policies of neighbors [ 37 , 38 ]. Thus, to control for policy diffusion, we constructed a variable to reflect international travel policy adoption of neighboring countries by averaging the strictness of each country’s neighbors weighted by the share of international tourism. Inbound tourism data of 197 countries were obtained from the Yearbook of Tourism Statistics of the World Tourism Organization [ 46 ]. The data consist of total arrivals of non-resident tourists or visitors at national borders, in hotels, or other types of accommodations; and the overnight stays of tourists, broken down by nationality or country of residence, from 1995 to 2018. Due to differences in statistical availability for each country, we take records from 2018 (or 2017 if 2018 is not available) of arrivals of non-resident tourists/visitors at national borders as the country weights for the computation of foreign international travel policy. If arrival records at national borders are not available for these years, we check for the 2018 or 2017 records on arrivals or overnight stays in hotels or other types of accommodation before relying on records from earlier years. To determine the weighted foreign international restriction policy for each country, we calculated the weighted sum using the share of arrivals of other countries multiplied by the corresponding policy value ranging from 0 to 4. Footnote 6

Similarly, case severity amongst countries comprising the majority of inbound tourists should also increase the likelihood of a country adopting travel restrictions. We thus constructed a variable which takes the sum of the number of confirmed cases from neighboring countries weighted by their share of total arrivals in the focal country (log).

While [ 47 ] suggests that the diffusion of social policies is highly linked to economic interdependencies between countries, and is less based on cultural or geographical proximity, we test the sensitivity of our results using a variety of measures of country closeness (Fig. S 4 and S 5 ). Doing so also allows us to examine which factors are more likely to predict COVID-19 policy diffusion. In general, while our results are not sensitive to other dimensions of country proximity, decisions to adopt travel restrictions are best explained by models where neighbors are defined by tourism statistics (see SI Appendix ).

Previous studies have found that countries with higher government effectiveness took longer to implement domestic COVID-19 related policy responses such as school closure (e.g., [ 36 , 39 ], perhaps due to (mis)perception that a well-functioning state should be able to cope with such a crisis as the current coronavirus pandemic and therefore, has more time or propensity to learn from others and develop well-considered COVID-19 response plans. Therefore, we also control for governance capacity; the data for which is based on measures of state capacity in the Government Effectiveness dimension of the 2019 Worldwide Governance Indicators (the World Bank).

We check the robustness of our results using alternative measures such as the International Country Risk Guide (ICRG) Quality of Government and tax capacity (tax revenue as % of GDP obtained from the World Development Indicators) [ 38 , 47 ]. The ICRG measure on the quality of government is computed as the average value of the “Corruption”, “Law and Order”, and “Bureaucracy Quality” indicators. We include additional control variables to account for each country’s macroeconomic conditions, social, political, and geographical characteristics. For macroeconomic conditions, we obtained the latest record of GDP per capita, unemployment rate, and Gini coefficient from the WDI. We include population density, percentage urban population, and share of the population over 65, to control for the social structure of the country, which might affect the odds of implementing the policy due to a higher risk of rapid viral transmission and high mortality rates [ 38 ]. We also control for the number of hospital beds in the population [ 36 , 38 , 39 , 40 ], which we used to proxy for a country’s health system capacity, as countries with higher health capacity may be less likely to implement restrictive travel measures. Footnote 7 We use the electoral democracy index from V-Dem Institute to control for the type of political regime [ 36 , 38 , 40 ]. Following previous studies, we include a dummy variable for countries with prior experience of managing SARS or MERS [ 38 , 48 , 49 ]; defined as those with more than 50 cases. Lastly, we include continent dummies which would absorb any unobserved regional heterogeneity [ 36 ] Footnote 8 and country-specific weekend days, as policy changes might have occurred less often on days when politicians are not generally active or at their workplace.

Empirical strategy

We explore the following questions: how will more globalized countries respond to COVID-19? Do they have more confirmed cases before they first implement travel restrictions? Do they take longer to implement travel restriction policies in general? Which dimension of globalization (i.e., social, political, or economic) contributes most to these responses? To provide answers to these questions, we first report the correlations between the level of globalization and the time gap between the first confirmed domestic case and the implementation date of the first international travel restriction policy, calculated using records from the Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker (OxCGRT [ 44 ];) on the timing of restrictions on international travel for each country and COVID-19 case statistics from the ECDC and CSSE [ 45 ]. We then examine the relationship using survival analysis through a multiple failure-event framework. This approach allows us to examine the underlying factors which affect the implementation of international travel restriction policies across country borders in an attempt to isolate the effect of globalization. It also allows us to use ‘incomplete’ datasets as certain countries may not have implemented any type of policy or may have implemented a strict policy without first implementing a less strict one (i.e., not sequentially implement policies of ‘least strict’ to ‘most strict’). Furthermore, we conjecture that as a consequence from the above, countries with higher levels of globalization may have more confirmed cases by the time the first policy was introduced. Therefore, we also examine the relationship between globalization and the number of confirmed cases (in logs) at the time of policy implementation.

We employ the time-to-event analysis (survival analysis or event history analysis) to examine the role of globalization in the timing of international travel restriction policies. Similar to previous studies [ 37 , 38 , 50 ], we use the marginal risk set model [ 51 ] to estimate the expected duration of time (days) until each policy, with increasing strictness, was imposed by each country. Specifically, we model the hazard for implementing screening , quarantine, ban on high-risk regions , and total border closure separately; thus, allowing the possibility that a country may adopt a more restrictive policy early on, as countries are assumed to be simultaneously at risk for all failures (i.e., implementation of any level of policy strictness). Intuitively, as more stringent policies are less likely to be implemented or adopted early (especially if state capacity is high), we stratified the baseline hazards for the four restrictions to allow for differences in policy adoption rate. Yet, when a country adopts a more restrictive travel restriction policy (e.g., total border closure ) before (or never) implementing the less restrictive ones (e.g., ban on high-risk regions ), the latter is effectively imposed (at least from an outcome perspective). Thus, we code them as failure on the day the more restrictive policy was implemented. Footnote 9 We also stratify countries by the month of the first confirmed COVID-19 case, Footnote 10 as countries with early transmission of coronavirus have fewer other countries from which they can learn how best to respond to the pandemic [ 52 ]. This is important because disproportionally more countries with a higher globalization index contracted the virus early (Fig. S 2 in the SI Appendix ). Additionally, we stratify time observations into before and after pandemic declaration (11 March 2020) [ 53 ] as it is likely to significantly increase the likelihood of countries adopting a travel restriction policy (particularly for border closures as seen in Fig. 2 ) as consensus on the potential severity of the pandemic solidified. Out of all 184 countries in our sample, 3 and 39 did not implement ban on high-risk regions and total border closure , respectively, before the end of the sample period, and are thus (right) censored (Fig. 1 ); i.e., nothing is observed or known about that subject and event after this particular time of observation.

We define the time-at-risk for all countries as the start of the sample period (i.e., 01 January 2020) Footnote 11 and estimate the following stratified (semi-parametric) Cox proportional hazards model [ 37 , 38 , 50 ]: